Abstract

This article explores how the polyvalent nature of violence in Julia Ducournau’s film Titane (2021) orients viewers towards posthumanist ontologies and epistemologies. Titane follows the film’s polymorphously perverse female protagonist, Alexia, as she undergoes a physical and phenomenological transformation following a sexual encounter with a car. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s assessment of violence as the assertion of power, I examine the disarticulation – and rearticulation – of Alexia’s body as she transforms from human to cyborg. I argue that Ducournau uses violence on the mutable body to produce sites for potential liberation of the subject.

Man is sick because he is badly constructed.

We must make up our minds to strip him bare in order to scrape off that animalcule that itches him mortally,

god,

and with god

his organs.

For you can tie me up if you wish,

but there is nothing more useless than an organ.

When you will have made him a body without organs,

then you will have delivered him from all his automatic reactions

and restored him to his true freedom.

Then you will teach him again to dance wrong side out

as in the frenzy of dance halls

and this wrong side out will be his real place.

Antonin Artaud, To Have Done with the Judgement of God, 1947.

1 Introduction

Despite the violent and experimental nature of her work, French filmmaker Julia Ducournau states that she does not make body horror. Nevertheless, she employs genre conventions to assist in narrative construction: “I do think this is a real term, but I don’t think I make body horror. I use body horror tools in my films, which I believe are dramas, or love stories. I use these tools because I express myself like this in the way I relate to the body” (Ducournau, 2021a). In Raw (2016), Ducournau uses cannibalism to explore coming-of-age traumas and familial relations. In Titane (2021), Ducournau follows the film’s perverse female protagonist, Alexia who, following a car accident as a child, retains a sexual attraction to cars in adulthood. A serial killer on the run, Alexia masquerades as the missing son of middle-aged fireman Vincent. After discovering that she is pregnant from an earlier sexual encounter with a car, Alexia finds it increasingly difficult to disguise her identity from Vincent while the baby gestates. Undergoing a physical and phenomenological transformation throughout the film, Alexia reaches apotheosis when she must deliver the child, a human–machine hybrid. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s assessment of violence as the assertion of power, I examine the disarticulation – and rearticulation – of Alexia’s body as she transforms from human to cyborg. I argue that Ducournau uses violence on the mutable body to produce sites for potential liberation of the subject.

Nearly half a century before Titane, in the Dialectic of Sex, Shulamith Firestone argued for the “artificial womb” as the key to women’s liberation (Firestone, 1970). The artificial womb, legitimized by access to contraception and reproductive technology, was the means by which to free women from patriarchal oppression. This reproductive technology was considered progressive as it severed the connection between sexuality and reproduction. As Judy Wajcman articulates in her book Technofeminism, there is an omnipresent relationship between the female body and technology:

Biomedical technologies are also the site of hopes and fears. These technologies appear to offer fantastic opportunities for self-realization - we can literally redesign our bodies and commission designer babies. Women can defy biology altogether by choosing not to have a child, choosing to have a child after menopause, or choosing the sex of their child. The ubiquitous cyborg has become an icon for the idea that the boundaries between the biological and the cultural, and between the human and the machine, have been dissolved. These dichotomies situated women as natural and different, and served to sustain the previously ordained gender order. Severing the link between femininity and maternity, as these new body technologies do, disrupts the categories of the body, sex, gender and sexuality. This is liberating for women, who have been captive to biology. (Wajcman, 2004, p. 4)

In Titane, Alexia severs the link between femininity and maternity while simultaneously severing the boundaries between the human and posthuman. As articulated by Bruce Clarke in The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Posthuman, “a posthuman event names some transformative outcome that once followed, is now following, or will at some point follow from the human” (Clark, 2016, p. 141). I employ the term posthuman rather than nonhuman as “the nonhuman turn does not make a claim about teleology or progress in which we begin with the human and see a transformation from human to the posthuman, after or beyond the human” (Grusin, 2015, p. xix). In this way, while the posthuman is not distinct from the nonhuman, the posthuman pays special attention to a transformation of a subject that is the fulcrum of Titane’s narrative structure. Alexia becomes human and machine, paradoxically impregnated by the artificial technology that retains the possibility to offer her freedom from gestation. Using the tools of body horror, Ducournau disrupts the relationship between sex and object, male and female, biotic and abiotic. Through this process, Alexia becomes the “liberating and transformative figure” of the monstrous female protagonist as her flesh is recast in union with the posthuman (Creed, 2022).

2 (S)cars, Perversion, and Excess

The title alone, Titane, the French word for titanium, positions technology at the nucleus of the film. From the exposition, it is clear that Alexia uniquely engages with objects and the world around her. The film opens with a close-up shot of a humming engine and transmission that converges with the humming of a young Alexia inside the car. As Alexia takes off her seatbelt in an attempt to climb to the back of the car, her father turns around to tell her to sit down. While doing so, he loses control of the car and slams into a slab of concrete, brutally wounding Alexia in the accident.

The viewer is then witness to the reassembling of Alexia; blood and metal marry as her skull is hammered into a stabilization apparatus, and the pieces of her bones rejoin one another. She is left with a visible titanium plate implanted in the side of her head.

This kind of wound-focused violence is present in David Cronenberg’s 1996 film Crash, where characters are sexually attracted to car accidents. Ducournau, like Cronenberg, facilitates the evolution of flesh through metal using the fetishization of vehicles and violence. Notably, characters in both Crash and Titane wear their marks of autophilia upon their body; in Crash, characters Vaughan and Ballard receive a tattoo of an automobile, and in Titane, Alexia has a metal plate implanted in her head such that it is clearly visible. As articulated by Parveen Adams, “This kind of bodily violence is an experience of inhabited tissue, of an experience which life suffers in its attempt to maintain itself” (Adams, 2000, p. 120). The accident marks Alexia phenomenologically and physically as she carries this experience both in her skin and in her psyche. Alexia’s malleable flesh becomes one with the abiotic material, signalling the beginning of a transformation that will not be realized until later in the film. This is the first union of body and metal that both Alexia and the viewer experience. Furthermore, it is Alexia’s first encounter with technology-based violence. Not only is the car responsible for her injury, but she now must carry a piece of the accident in her flesh in perpetuity. The accident acts as the genesis of Alexia’s queer corporeal relationship with the world and with herself. Immediately upon exiting the hospital, she returns to kiss the car that wounded her (Figure 1, 4:26)[1]. As we watch Alexia caress its metal frame, the title card displays, and we are immediately thrust decades into the future and are introduced to an older Alexia.

Most crucially, the accident activates Alexia’s death drive: she consciously and unconsciously recreates, reimagines, and re-experiences the traumatic event via compulsions toward violence and destruction. Marked by the accident, Alexia carries her mechanophilia into adulthood. Now a dancer at a car show, she is eroticized by the metallic, becoming violently fascinated by a fellow dancer’s nipple piercings and attempting to tear the ring out with her teeth. As Ducournau acknowledges, “I made it seem as though the cars and the girls are essentially the same at the start. They’re equally objectified” (Ducournau, 2021a). In this way, the nature of Alexia’s work also inherently has a degree of gendered violence; both she and the cars are sexual objects for the viewers of the show (Figure 2, 7:50).

Young Alexia embracing the car after the accident. Titane (2021).

In this scene, we also see Alexia’s unique fascination with and fetishization of objects, as she becomes aroused by the cars on which she dances while being watched by a sea of captivated onlookers. Her own relationship with the car subverts their gazes: she is getting off on it. Yes, she is performing. But she, in addition to the audience, is receiving pleasure. As defined by Linda Williams in her foundational paper “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess,” “Perversions are usually defined as sexual excesses, specifically as excesses which are deflected away from “proper” end goals onto substitute goals or objects” (Williams, 1991, p. 6). As evident in the scene of her dancing on the car, Alexia’s haecceity careens toward the posthuman, engaging in a relationship with the cars that extends beyond utility toward pleasure. While describing the pathologizing of the sexually deviant in The History of Sexuality, Foucault states

Imbedded in bodies, becoming deeply characteristic of individuals, the oddities of sex relied on a technology of health and pathology. And conversely, since sexuality was a medical and a medicalizable object, one had to try and detect it—as a lesion, a dysfunction, or a symptom—in the depths of the organism, or on the surface of the skin, or among all the signs of behavior. The power which thus took charge of sexuality set about contacting bodies, caressing them with its eyes, intensifying areas, electrifying surfaces, dramatizing trouble moments. It wrapped the sexual body in its embrace. There was undoubtedly an increase in effectiveness and an extension of the domain controlled; but also a sensualization of power and a gain of pleasure. (Foucault, 1978, p. 44)

Here, Foucault describes a ubiquitous relationship between aberrant sexualities and technology. These perverted tendencies are considered a dysfunction in the “depths of the organism, or on the surface of the skin,” lesions that ought to be cut out and cured. These valences of perversion are present in Alexia as she not only wears her conspicuous scar but also retains the experience of the accident.

Perversion is a vehicle of power; as desire is desublimated, power can be imposed upon the deviant. Paradoxically, those who engage with their desires in spite of this oppression might experience a sensualization of power and a gain of pleasure. In this way, Alexia’s deviant relationship with the car as a substitute technological object is a means by which to resist this power. For the subject, “perversion can be a form of resistance which works in terms of desire and knowledge” (Dollimore, 2000, p. 23). Technology allows for the modification and suppression of these desires but simultaneously provides the opportunity for objects to act as sexual objects. In Titane, these deviant affinities, which were historically hidden and suppressed, now have a liberating potential for Alexia. But while she is empowered to explore her deviant tendencies as a dancer, this freedom is still qualified: she is subject to the power and gaze of those who watch her. Her body is hers and not hers – her pleasure belongs to both her and the audience. Therefore, as Foucault describes, her perversions are still “an extension of the domain controlled.”

The evening following the scene of the car dance, Alexia attempts to drive home from work and is approached by an incessant fan. Trying to appease him, Alexia rolls down her window to sign her autograph, but the man forcefully kisses her. Alexia kills him by penetrating his ear with her hairpin. After disposing of his body in a laissez-faire manner, she returns home and is met with an unrelenting bang on her door. When she walks outside to determine the source of the noise, she is welcomed by the Cadillac that she was dancing on earlier, doors open and lights illuminated. This scene is the literal and narrative climax of Alexia’s relationship with the car. The Cadillac is given the same agency as a human, seducing Alexia to come outside and inviting her to enter.

As Alexia gets in, the car begins gyrating and they, human and posthuman, flesh and metal, have sex. As the red seatbelts wrap around her arms, Alexia orgasms, and a spotlight on the Cadillac makes a spectacle of their copulation. Williams states that there are specific features of bodily excess that contribute to “gross” genres by displaying the spectacle of the body in states of emotional excess, whether in regard to terror or ecstasy (Williams, 1991). In these scenes of ecstasy, Ducournau uses a warm colour palette showcasing the warm glow of the headlights, the orange contours of the Cadillac, and the red of the seatbelts. As the film continues, Ducournau oscillates between colours, a technique which the film’s cinematographer Ruben Impens calls “emotional lighting” (Impens, 2021). As Impens states,

I discover films through light. In Titane it’s not complex, but it is emotional, it hits you in the face. It shifts from warm and orange to blueish cool white and these contrast with all other colours in the film. This is a strong, harsh light, it’s not gentle. It penetrates the characters and places and reveals them for what they are. Or want to be. […] In prep, we went through the script and planned every scene in terms of light, angles and colour contrasts, plus details like the shininess of titanium reflections and metal surfaces, and the sexiness of wet floors. (Impens, 2021).

Ducournau uses the oscillation of colour, these synaesthetic reorderings, to aid in Alexia’s transformation toward the posthuman. This is a short scene. But it is the genesis of the physical and phenomenological transformation that Alexia will undergo throughout the remainder of the film.

3 The Transformative Body

The morning following the encounter with the car, Alexia examines bruises on the inside of her thighs and clutches her sore abdomen. Though it does not seem that she notices, the viewer is provided with a shot of a dark substance seeping through her underwear. As Alexia and her father watch the morning news, the reporter announces that a 47-year-old man is the fourth victim of a string of murders of the year. While we are not explicitly told, it is presumed that these murders are at the hands of Alexia. “You ok?” her mother asks. “My belly hurts,” Alexia replies.

In the following scenes, Alexia notices that her abdomen is distended. When her pregnancy test indicates “positive,” she takes her remaining hairpin and attempts an abortion. After telling her co-worker this news, Alexia proceeds to kill her and two other housemates. However, a fourth housemate is able to escape after witnessing the murders. Having been seen, Alexia lights her clothes and belongings on fire and abandons her old life, now a fugitive.

While this is one obvious dimension of violence, notably, Alexia’s identity as a serial killer is one of the less salient aspects of the film. It is first used to demonstrate her violent tendencies as a feature of her death drive and subsequently as a device to motivate the need to hide her identity. This attempt to disguise herself is paralleled by her physical transformation through the impregnation by the car. There is, then, a paradox of a narrative wherein Alexia, who shows a blatant disregard for human life, must gestate and deliver a teratological child. As Ducournau explains, “Metal is cold, heavy, dead, it doesn’t react to our eyes. I wanted to try to make it something alive” (Ducournau, 2021b). At this point in the film, Alexia faces the consequences of both her violent actions and her perverse affinities: she must alter her identity if she wishes to evade the police, but this effort is opposed by her changing body due to her pregnancy from the car.

As she attempts to take a train out of the city, Alexia finds a portrait of her face plastered upon the wall alongside pictures of missing children. She decides to assume the identity of the son of Vincent Legrand, Adrien, who has been missing for over a decade. In order to disguise herself and assume this identity, Alexia attempts to de-gender herself in the train station bathroom. She cuts her hair, painfully binds her distended abdomen, and violently breaks her own nose. Ducournau subverts the audience’s expectations of Alexia: “Actually, she can be pretty violent; actually, her sexuality is pretty fucked up. Oh, actually, she can be a man. You thought she was a woman!” (Ducournau, 2021a).

This transformation is aided by Ducournau’s selection of Agathe Rousselle as the androgynous face of Alexia. Ducournau considered both men and women during the casting process, stating, “In order for us to relate to her transformation and believe she is actually becoming that person and not somebody just wearing costumes, I needed someone who was a white canvas” (Ducournau, 2021a). This act of disguise begins the queering of gender and familial relations, as Alexia must transform not only her gender performance but her flesh in order to act as Vincent’s son.

The veritable acts of self-inflicted violence not only serve in aiding her disguise, but begin Alexia’s transformation toward the posthuman. The uncontrollable, violating transformation of pregnancy is mirrored by the self-inflicted transformation of her own body. When he arrives at the police station, it is obvious that Alexia is not Vincent’s son and more obvious that he knows so; Alexia looks nothing like the “Adrien” in the missing child poster. Nevertheless, Vincent refuses a paternity test and takes Alexia home as his son. The colour-saturation that was present earlier in the film is stripped away, and we are left with the essential: two characters and their relationship with one another.

When they first return to Vincent’s home, Alexia will not speak to Vincent. He becomes increasingly frustrated with her as he tries to integrate her into his life, bringing her to his job at the fire station and attempting to build friendships among Alexia and the other firemen. In response to her petulant silence, he yells “Just say ‘yes’ like a normal person! Even parrots can say yes! No need to be human” (52:10). In these subliminal ways, Vincent recognizes that Alexia is more than human. And despite his initial frustrations, he defends her against others who comment on her disposition. When his co-workers criticize Alexia, Vincent fervently replies, “Don’t talk about my son.” And to Alexia, he assures, “I don’t care who you are. You’re my son. You’ll always be my son. Whoever you are.” As Alexia proceeds with this transformation to agender-ness, she also begins a transformation toward the posthuman. As her body is recast, she begins to foster her symbiotic relationship with Vincent but finds it increasingly difficult to hide her identity.

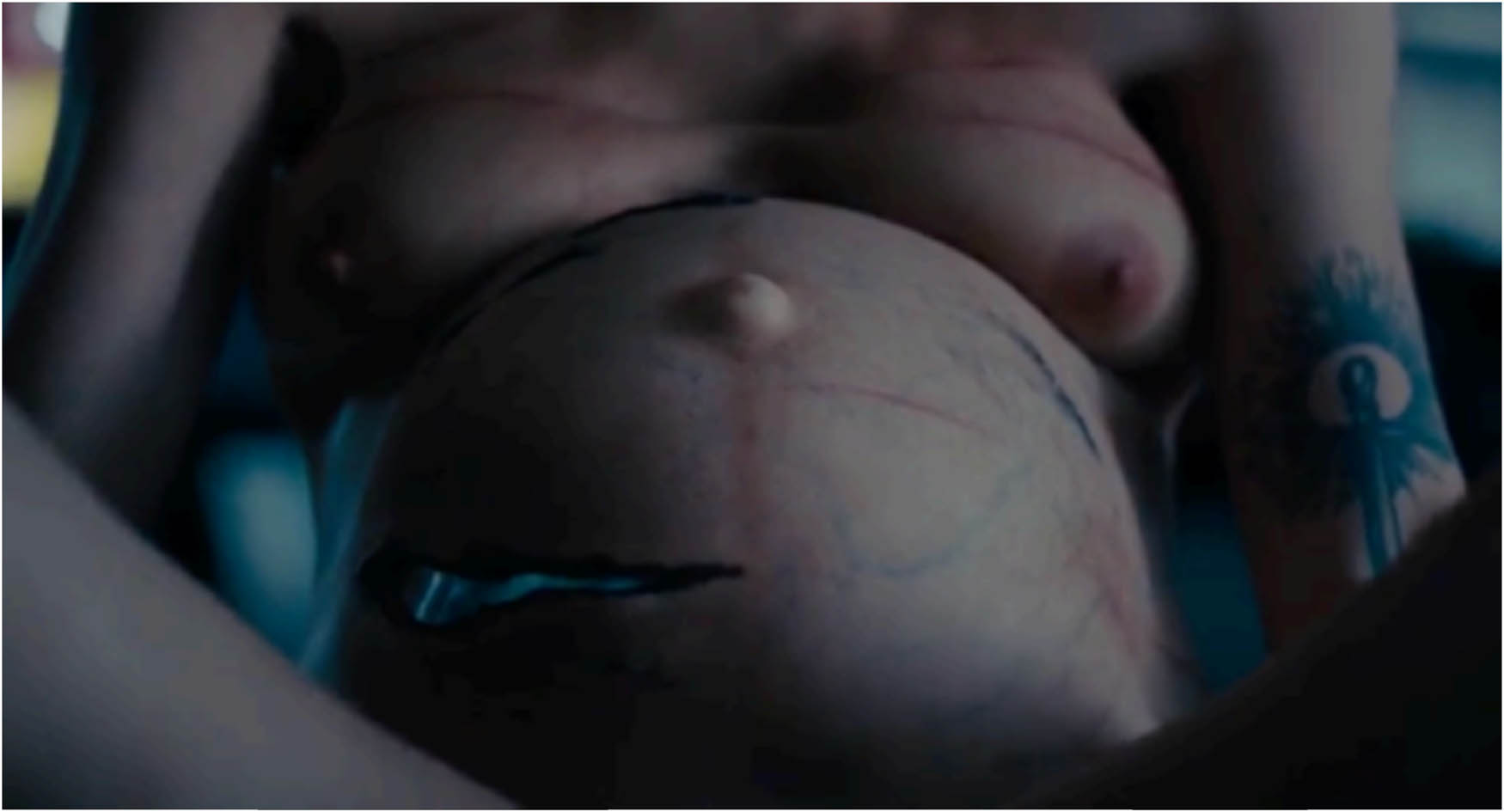

As the child gestates inside her, Alexia’s body is steadily disfigured. When she itches her abdomen until it bleeds, she punctures it and her entire finger penetrates her skin, revealing a steady stream of motor oil and metallic organs (Figure 3, 1:16:03). Running her fingers over her mutated flesh, Alexia processes her alien-like image and then once again camouflages herself to maintain her disguise. Barbara Creed describes the body horror genre as subdivisions of the grotesque body: the metamorphosing body, the generative body, the invaded body, and the disintegrating or exploding body (Creed, 1993, pp. 16–21, 49–56). Titane explores all of the subdivisions described by Creed. Alexia’s body becomes metamorphosed via violent self-mutilation, transmogrified through the copulation of flesh and metal, and invaded by the gestation of the child. Ducournau takes apart Alexia’s body, disarticulating the relationship between body and technology such that the viewer might witness them torn apart and put back together.

Alexia dancing atop the Cadillac (Titane, 2021).

Alexia’s metallic organs (Titane 2021).

At this point in the film, Alexia can no longer conceal her identity or transformation. Her body begins to disintegrate; motor oil leaks from her orifices, and she has no choice but to have the child. The ebullient fusion of metal and flesh culminates in her giving birth, wherein she literally rips apart at the seams (1:37:50-1:42:30).

At the beginning of the scene, Vincent watches Alexia convulse in pain and begin vomiting motor oil. As Vincent positions her to give birth and says, “Push, Adrien,” she reveals that her name is actually Alexia. Vincent replies, “Push, Alexia.” Though it is clear that Vincent always knew that Alexia was not Adrien and chose not to acknowledge otherwise, this act of calling her by her name as she gives birth is the ultimate disillusionment of identity for both characters. Alexia reveals herself, and Vincent finally admits that she is not actually his lost son. In this scene, Alexia is completely naked, and Vincent stands only in his boxers as they both literally reveal themselves to one another. This encounter is the first time Vincent has seen Alexia as herself.

Though there is little dialogue in this scene, there is the ominous crescendo of bells tolling, simultaneously indicating a climax, a completion, and an end to Alexia’s metamorphosis. The bells sound almost religious, suggesting not only that Alexia’s time is up, but that her transformation is complete. Alexia’s birth is a welcome of the homogenization of the human and posthuman body. Given her previous climax after intercourse with the car, Alexia’s giving birth also indicates a climax of sorts. As Williams writes, “Aurally, excess is marked by recourse not to the coded articulations of language but to inarticulate cries of pleasure in porn, screams of fear in horror, sobs of anguish in melodrama” (Williams 4). Ducournau blurs the lines between body and object, interweaving sex with fear and horror with dramatic narrative.

As Alexia screams, the camera shoots her from behind, framing her in what could, without context, be indistinguishable from the orgasm she experiences earlier in the film (Figure 4, 1:39:35). Alexia’s end acts as her ultimate ecstasy; she is no longer physically bound by that which is gestating inside her. This scene creates a paradox as the death of Alexia’s human body gives birth to inorganic flesh.

Alexia gives birth (Titane, 2021).

The seams of her distended stomach rip open to reveal shiny metal as motor oil pools on the bed. Vincent is positioned between Alexia’s legs as the one to catch the baby, and in doing so, he acts as the recipient of the child, cutting the umbilical cord and swaddling the baby. In a clear extratextual reference to David Lynch’s Eraserhead, Alexia gives birth to something, though not a child in any normative form (Lynch, 1977). It, too, has undergone a transformation from zygote to posthuman child, only to be revealed in the final scene of the film.

In giving birth, Alexia is finally released from the violence of gestation, the evidence of which she has been tirelessly attempting to disguise for months. Her body will no longer be subject to mutation and mutilation at the mercy of the child. This completion of transformation leads to Alexia’s death as the metal plate in her head finally splits open. As soon as the child exits her body, she is delivered of its effects. The child survives, and it, unlike Alexia, is embraced in spite of its posthuman nature. As Vincent delivers the child, Alexia’s scar splits open, and while Vincent attempts to revive her, he is unsuccessful.

The baby cries in a humanlike way, but when Vincent removes the swaddled blanket, he reveals that it, too, is posthuman. Cyborgian, its skin is inked in motor oil, and its body is held together by a titanium spine (Figure 5, 1:42:20). Vincent embraces the baby and whispers “I’m here,” thereby mirroring the final words he told Alexia.

Vincent embraces Alexia’s child after her death. Titane (2021).

This scene functions as the apex of the queer familial narrative that Titane creates, as in Alexia’s unveiling of identity and subsequent death, she provides Vincent the opportunity for paternal restoration. Though Alexia cannot replace Vincent’s real son, she is able to give him this child, one which he cares for regardless of mutation or form. This is the final scene, and the viewer is not a witness to the relationship between Vincent and the baby. But in his words, “I’m here,” it is evident that he intends to accept the child as his own. After the disappearance of his own son and the death of Alexia, Vincent is given the opportunity to usher love into the life of another, providing him with a rebirth of his own. But he must first accept the monstrous.

4 Body Horror and Creation as Resistance

It is paramount that Alexia does not undergo her transformation willingly: while Titane’s narrative redeems Vincent, it is at the cost of Alexia’s life and the invasion of her body. In describing the process of gestation of the invaded body, Creed states, “The possessed or invaded being is a figure of abjection in that the boundary between self and other has been transgressed. When the subject is invaded by a personality of another sex the transgression is even more abject because gender boundaries are violated” (Creed, 1993, p. 32). Alexia first must change her gender performance through violent measures in order to escape the consequences of her violent actions. But another locus of violence is that she is inhabited by the posthuman. Creed describes a subject invaded by another sex, but Alexia is invaded by a child that is both human and machine. A consequence of her deviant relationship with the car, her flesh must now act as the incubator of her abject affair.

While Laura Mulvey describes the phallus as an object of fear for male characters in film, Barbara Creed describes the womb as a site for potentiality: “The womb is not the site of castration anxiety. Rather, the womb signifies ‘fullness’ or ‘emptiness’ but always it is its own point of reference” (Creed, 1993, p. 27; Mulvey, 1999, pp. 833–834). Though she disguises herself as a man in order to escape, Alexia retains her reproductive capabilities. In this way, Alexia is the semiotic mother, the monstrous feminine who also acts as the generative body. Just as she destroys the body in her acts of violence, she creates from within herself.

By mutating and metamorphosizing the body, Ducournau creates sites for the potential emancipation of Alexia, allowing for her psychological and phenomenological transformation.

This transformation begins as a child when she first encounters the accident with the car. As an adult, she continues this process by engaging in a sexual relationship with the car and subsequently amending her gender performance as a means by which to disguise her identity. She disarticulates other bodies by her violence as a serial killer, and disarticulates her own when she transmogrifies herself in disguise. Crossing the boundaries of gender and humanism, Alexia resists the violence that both she has asserted and that has been asserted upon her. Foucault understands violence as the assertion of power, the imposition of action upon and over others, bodies and things, that cannot resist it:

One must seek the character proper to power relations in the violence which must have been in its primitive form […] In effect, what defines a relationship of power is that it is a mode of action which does not act directly and immediately upon others. Instead, it acts upon their actions: an action upon an action, on existing actions or on those which may arise in the present or the future. A relationship of violence acts upon a body or upon things; it forces, it bends, it breaks on the wheel, it destroys, or it closes the door on all possibilities. (Foucault, 1982, p. 789)

This synthesis of body and thing is precisely what Alexia undergoes. Impregnated by an object, a body of metal and oil, she cannot stop her physical and phenomenological transformation. It is only through the disarticulation of her body that Alexia might resist this power. She is the ouroboros. While her body is overtaken in a violent manner, she achieves liberation from the violence that has oppressed her: her identity as a serial killer, the gendered violence from her career. It is this deviant relationship with her car that facilitates the transformation that allows for her liberation. As Foucault states,

Sex is worth dying for. It is in this (strictly historical) sense that sex is indeed imbued with the death instinct. When a long while ago the West discovered love, it bestowed on it a value high enough to make death acceptable; nowadays it is sex that claims this equivalence, the highest of all. (Foucault, 1978, p. 156)

It is in the deviant act that Alexia engages with the death instinct. Her encounter with the car is worth dying for: she is disarticulated as a body such that she resists the relationship of violence. Stemming from the trauma of the car accident as a child, Alexia’s pathologies result in her pregnancy. She then must carry the child to term, and in doing so, her body ceases to sustain her own life and rather sustains that of the child. In this way, she suffers the consequence of her deviant attractions but is freed from the death drive, no longer able to commit the violent actions that required her to abandon her previous identity.

Congruently, she is released from the trauma that was the origin of these destructive tendencies as well as the perverse affinities that led to her pregnancy, a pregnancy that she did not welcome. While Alexia attempts to rid her body of the child throughout the film, it is only in its deliverance that she is freed from its influence.

Because this pregnancy necessitated violent means of binding and controlling her body, in her death, she no longer has to hide her identity from Vincent. And in delivering the child, she rids herself of her dependence on the technologyl by expelling the last parts of the car. But this operation is only consummated when her body is invaded by the car’s child. Over and undertaken by the abiotic, her corporeal form no longer possesses the capability to exert violence upon itself or others.

Ducournau herself calls Alexia’s transformation an emancipation: “monstrosity, for me, is always positive. It’s about debunking all the normative ways of society and social life. […] Her monstrosity had her emancipated.” (Ducournau, 2021a). But Alexia’s liberation is a qualified and unrealized one as she, unlike Vincent, is not afforded the opportunity to live unburdened from her pathologies. Alexia, by acting as Adrien, serves to redeem Vincent as a paternal figure. Alexia dies knowing that Vincent has accepted her, yet Vincent is liberated without facing the same fate. In this way, despite a progressive narrative, Titane perpetuates the trope of using a queer character to support the redemption of the cisheteronormative one. And while Alexia and Vincent each undergo distinct liberations, they are not symmetrical nor wholly reciprocal. Alexia rips apart at the seams, and Vincent lives to witness the product of her liberation.

5 Posthumanist Ontologies

By undergoing a physical and phenomenological transformation toward the posthuman, Alexia acts as a postgender figure: a hybrid of human and car, she is the cinematic cyborg, defying binaries of biotic/abiotic, body/thing, and male/female. Her body is mutable, subject to imposition, and affected by the omnipresent relationship between humans and their machines. Introduced in relation to her posthumanist hypothesis, Donna Haraway defined the cyborg as “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” (Haraway, 1985, p. 65). Haraway rejects essentialist binaries, arguing that the cyborg is a postgender figure representative of the ubiquitous relationship between human and machine:

Liberation rests on the construction of the consciousness, the imaginative apprehension, of oppression, and so of possibility. The cyborg is a matter of fiction and lived experience that changes what counts as women’s experience in the late twentieth century. This is a struggle over life and death, but the boundary between science fiction and social reality is an optical illusion (Haraway, 1985, p. 66).

Though motivated by her need to obscure her identity, Alexia undergoes a transformation that is not only postgender but undoubtedly posthuman. As articulated by Anne Smelik, the “cinematic” cyborg acts as a counter-hegemonic figure to deconstruct bounds of gender and anthropocentrism: “In cultural studies, the cyborg has been hailed as a posthumanist configuration in its hybridity between flesh and metal or digital material, its wavering between mind and matter, and its shifting boundaries between masculinity and femininity” (Smelik, 2016, p. 110). The cyborg exists rhizomatically in and among these binaries of gender and in/organic material, and so too does Alexia: she is human, she is machine, son, daughter, and mother. She severs the boundaries of human and machine, both in her deviant tendencies and in the transformation of her body. Oblique to “The traditional notion of the human body as a sacrosanct entity,” the disarticulation of Alexia’s identity and body orients viewers toward worlds of the post-anthropocene where human and posthuman unite (Lekshmi, 2023, p. 7). Engaging in an intercorporeal relationship not only with the car but with herself, Alexia forces the viewer to imagine the transgression of bodies and machines. It is only by recognizing the mutability of the body that we might find acceptance:

The posthuman entity thus proves more human than a human being in its capacity for love, or at least, for transmitting lessons on how to love. Something new has then emerged from the human–posthuman interaction: it is within the virtual realm of posthumanity that humans find solace in the enfleshed embrace of one another (Smelik, 2016, p. 118).

As Smelik states, the human and posthuman interaction provides the possibility for something new. In Titane, the “something new” is literally the baby that Alexia births after her human–posthuman encounter with the car. More saliently, the something new is a variety of liberatory experiences that both characters undergo as they accept one another and themselves.

This intersubjective narrative of love and belonging is only possible through recognition of the Other and the transformation of Alexia toward the posthuman. Vincent knows Alexia is not his son; he receives her anyway. But it is only through the acceptance of the monstrous that either might experience unconditional love.

Ducournau stitches together bodies and machines, suggesting a poetics of posthumanist ontology from which we may focus epistemological positions. Titane calls us to reconsider the way in which we engage with machines and with ourselves. The body is fragile and precarious and dynamic. It is only in this recognition that we might bear witness to our own humanity.

Acknowledgments

To Philip Alexander Mills, for our shared love of this film and other stories about cars.

-

Funding information: Author states no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

Adams, P. (2000). Death drive. In M. Grant (Ed.), The modern fantastic: The films of david cronenberg. Praeger Publishers, 2000.Suche in Google Scholar

Artaud, A. (1947). To have done with the judgement of god. In S. Sontag (Ed.), Selected writings (p. 571). Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976.Suche in Google Scholar

Clarke, B. (2016). The nonhuman. In B. Clarke & M. Rossini (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to literature and the Posthuman. Cambridge companions to literature. (pp. 141–152). Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316091227.014Suche in Google Scholar

Creed, B. (1993). The monstrous-feminine: Film, feminism, psychoanalysis (1st ed.). Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203820513.Suche in Google Scholar

Creed, B. (2022). Return of the monstrous-feminine: Feminist new wave cinema (1st ed.). Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003036654.Suche in Google Scholar

Dollimore, J. (1990). The cultural politics of perversion: Augustine, Shakespeare, Freud, Foucault. Textual Practice, 4(2), 179–196. doi: 10.1080/09502369008582085.Suche in Google Scholar

Dollimore, J. (2000). Wishful theory and sexual politics. Radical Philosophy, 103, 18–24. Print.Suche in Google Scholar

Ducournau, J. (2021a). dir. Palme d’Or Winner Julia Ducournau on groundbreaking “Titane”: “I don’t want my gender to define me” Interview by Eric Kohn. IndieWire. https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/palme-d-winner-julia-ducournau-203739842.html?guccounter=1.Suche in Google Scholar

Ducournau, J. (2021b). Variety (2021, September 29), Julia Ducournau on her boundary-blurring film ‘Titane’: ‘My film is its own wild animal’. Variety. https://www.variety.com/.Suche in Google Scholar

Firestone, S. (1970). The dialectic of sex. William Morrow and Co. Print.Suche in Google Scholar

Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality Vol. 1: An introduction. R. Hurley, Trans.) Pantheon Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343197.10.1086/448181Suche in Google Scholar

Grusin, R. (2015). The nonhuman turn. University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt13x1mj0.Suche in Google Scholar

Haraway, D. (1985). A manifesto for cyborgs: Science, technology, and socialist feminism for the 1980s. Socialist Review, 80(15), 65–107.Suche in Google Scholar

Impens, R. (2021). “Sex, lies and metal.” Interview by Darek Kuzma. Cinematography World, (5), 32–33. https://www.cinematography.world/issue-05/.Suche in Google Scholar

Lekshmi, N. (2023). Human precarity and posthuman ontology in the anthropocene. The concept of order: Philosophical insights. Agathos International Review, 14(Issue 2 (27)), 7–15.Suche in Google Scholar

Lynch, D. (1977). Eraserhead. Libra Films International.Suche in Google Scholar

Mulvey, L. (1999). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. In L. Braudy & M. Cohen (Eds.), Film theory and criticism: Introductory readings (pp. 833–844) Oxford UP, 1999.Suche in Google Scholar

Raw. (2016). Dir. Julia Ducournau. Petit Film. Wild Bunch Distribution.Suche in Google Scholar

Smelik, A. (2016). Film. In B. Clarke & M. Rossini (Eds.), In The Cambridge companion to literature and the posthuman (pp. 109–120). Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781316091227.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Titane. (2021). Dir. Julia Ducournau. Kazak Productions. Diaphana Distribution.Suche in Google Scholar

Wajcman, J. (2004). Technofeminism. Polity Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, L. (1991). Film bodies: Gender, genre, and excess. Film Quarterly, 44(4), 2–13. University of California Press.10.2307/1212758Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Situated Knowledge in Motion: Reconsidering Urban Feminist Methodologies

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Feminist Worldmaking Through Collective Curating: Kaleidoskop’s Relational Urban Aesthetics

- Tactical Spatial Interventions: Design for Gendered Spatial Justice in Peri-Urban Victoria, Australia

- Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- “A Good Bandit is a Dead Bandit”: Memetic Violence and AI on the Latin American Right-Wing Populism

- Violence(s): An Introduction

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Critical Hope in South African Higher Education: Using a Theory of Change Approach for Mid-Project Reflection on a Student-Staff Partnership Programme

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

- Metamodern Oscillation and the Artisan Ethic: The Poetics and Practice of the Band Adamlar

- Idiomaticity in the English Subtitling of Jordanian Movies on Netflix: A Cultural Analysis

- Cameras Off: Cultural and Social Influences on Students’ Webcam Use in Online Learning

- A Tale of Two Houses: Returning Ghosts and Hammad’s Appropriation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet

- Rewriting Women in the Qur’an: Gender, Ideology and Translation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Situated Knowledge in Motion: Reconsidering Urban Feminist Methodologies

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Feminist Worldmaking Through Collective Curating: Kaleidoskop’s Relational Urban Aesthetics

- Tactical Spatial Interventions: Design for Gendered Spatial Justice in Peri-Urban Victoria, Australia

- Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- “A Good Bandit is a Dead Bandit”: Memetic Violence and AI on the Latin American Right-Wing Populism

- Violence(s): An Introduction

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Critical Hope in South African Higher Education: Using a Theory of Change Approach for Mid-Project Reflection on a Student-Staff Partnership Programme

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

- Metamodern Oscillation and the Artisan Ethic: The Poetics and Practice of the Band Adamlar

- Idiomaticity in the English Subtitling of Jordanian Movies on Netflix: A Cultural Analysis

- Cameras Off: Cultural and Social Influences on Students’ Webcam Use in Online Learning

- A Tale of Two Houses: Returning Ghosts and Hammad’s Appropriation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet

- Rewriting Women in the Qur’an: Gender, Ideology and Translation