Abstract

Alash-Orda is the name of the government (People’s Council) of the national-territorial autonomy formed in December 1917 on the territory of modern Kazakhstan. This study investigates the ideas of the Alash-Orda movement through the analysis and interpretation of literary translations of fables from Russian into Kazakh. The main national ideas embedded in these translations were examined using contextual analysis and comparative methods. Key ideas of the Alash intellectuals included the separation of religious and state institutions, autonomy within Kazakh unity, equality for all regardless of origin, religion, or gender, and the right to free education in the native Kazakh language. The analysis of literary translations revealed the following ideas: self-determination of the nation, ridiculing the totalitarian regime, condemning force, and enlightening society through science and art. This work can contribute to improving technical capabilities in translated texts and developing new translation strategies.

1 Introduction

The Alash Autonomy, or Alash-Orda, was an unrecognised Kazakh proto-state situated in Central Asia, initially part of the Russian Republic and subsequently Soviet Russia. The Alash Autonomy was established in 1917 by Kazakh elites and subsequently dissolved with the Bolshevik prohibition of the ruling Alash party. The objective of the party was to achieve autonomy inside Russia and establish a national democratic state. The political unit was adjacent to Russian territories to the north and west, the Turkestan Autonomy to the south, and China to the east. The study of the ideas of the Alash party on the example of literary translations is relevant in terms of the following parameters: firstly, in terms of forming the national consciousness of the Kazakhs following the ideas contained in the texts written by Alash intellectuals and, secondly, in terms of understanding the peculiarities of translated texts and their adaptation into the Kazakh language. Thus, it is essential to identify the distinctive features in the artistic expression of the Alash party’s ideas to develop an overall understanding of the artistic translation from Russian into Kazakh.

The example of literary translation of fables shows that not only semantic aspects are important, but also the following: metaphorical and ironic characteristics, structural transformations, the use of equivalent vocabulary, phraseological phrases, and sayings. Since literary translation often aims to engage the target language audience, it may involve free interpretation (Stadnik, 2024; Vaišnorienė, 2024). However, this is not the only approach to literary translation; the method can vary based on the translator’s objectives, the target audience, and cultural factors. Thus, the domestication of a literary translation involves not only the interpretation of semantic components (morality, for example) but also artistic parameters. The literary translation of texts into the Kazakh language involved not only bringing the text to the culture of the language but also the loss of certain data from the source text.

The study of the national specificity of literary translation through the prism of national ideas is necessary for the formation of national consciousness among the younger generation, and for understanding the importance of the contribution of the Alash intellectuals to the struggle for Kazakhstan’s independence. Moreover, the study of national specifics is relevant in terms of using linguistic and cultural tools related to the presentation of national character. In the realm of fiction translation, the substitution of the source language’s linguistic elements with those of the target language is a significant challenge (Hoff & Barboza, 2025).

The advancement of machine translation has significantly impacted the field of literary translation (Bronin et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2022). Hansen and Esperança-Rodier (2023) conducted a comprehensive study on adapted machine translation for literary texts, focusing on how automated tools can enhance the translation process. Their annotation process revealed key opportunities for leveraging machine translation in future literary projects. Building on this, Macken et al. (2022) proposed a three-stage framework for literary translation: initial machine translation, followed by post-editing, and finally, revision. These studies underscore the need for developing new mechanisms for semantic text processing and tools that can effectively implement the principles of literary translation, ensuring that the nuances and artistic qualities of the original text are preserved.

Addressing lexical gaps in translation is critical, particularly when dealing with languages that possess inherently limited lexical inventories (Mizin et al., 2023; Ovcharuk, 2024). Sankaravelayuthan (2020) analysed these lexical disparities by examining the mismatch between lexical breadth and conceptual development, thereby highlighting the challenges translators face when the target language lacks equivalent lexical items. Kuusi et al. (2022) focused on filling these lexical gaps in texts written in low-resource languages, emphasising the importance of finding equivalent vocabulary that conveys national character and cultural nuances. Their work also explored the rhetorical effects on the audience when using such vocabulary, demonstrating how careful selection of words can significantly impact the reception of the translated text.

Literary translation serves not only as a means of conveying content but also as a pedagogical resource (Kononchuk, 2024). Leonardi (2024) examined the educational potential of literary translation, arguing that it can be a valuable tool in teaching language, culture, and literary analysis. Manolachi and Musiyiwa (2022) expanded on this idea, presenting literary translation as a form of social and pedagogical activity that can foster cultural understanding and linguistic competence. However, these studies did not delve into the specific national ideas realised in fiction and their pedagogical and educational goals, leaving room for further exploration in this area.

Cultural differences pose a significant challenge in literary translation (Kongyratbay, 2022, 2023). Guo and Yu (2023) conducted a study on the problems associated with eliminating cultural differences when using translation strategies. They highlighted the importance of preserving cultural nuances and ensuring that the translated text resonates with the target audience’s cultural context. However, their study did not establish a clear link between the linguistic and cultural features of literary translation and the implementation of national ideas in literary texts. This gap indicates a need for a more detailed investigation into how cultural differences can be effectively managed in translation.

Effective translation strategies are essential for preserving the integrity and artistic quality of literary texts (Fernández, 2024; Zhanysbayeva et al., 2021). Muallim et al. (2023) studied various translation strategies, including the roles of assistant, observer, educator, and supporter, and their frequency of application in literary translation. Their findings provided insights into how these strategies can be employed to enhance the translation process. Zhumabekova and Umirtasova (2021) focused on strategies for direct translation of texts from English to Kazakh, highlighting the unique challenges and opportunities presented by this language pair. However, the specific challenges associated with implementing these strategies in the works of Alash intellectuals remain unresolved, indicating a need for further research in this area.

Addressing literary translation in the context of translation strategies, it is possible to note the following: the most used strategy was domestication, in which the original text was brought into line with the target culture. Zhang (2021) highlighted the phenomenon of cultural sensitivity in Chinese–English translation. The author determined that translation can be addressed in the context of four main strategies, including phoneticisation, annotation, reader orientation, and radical change. There are two main strategies used when translating texts: domestication (adapting the source text to the norms and expectations of the target language and culture) and foreignisation (retaining features of the source text to preserve its original cultural and linguistic identity). Suo (2015) outlined the basic principles by which the adequacy of a translation can be assessed. The results of the study of literary translation by Mardiana and Ali (2021) showed that the following strategies were most often used in Indonesian–English translation: an observer, a helper, a supporter, and an educator. In the study of translation methods, Locatelli (2021) examined the theoretical prerequisites and practical approaches to the implementation of successful translation activities. Thus, the translation implemented the concept of the so-called tertiary translation, in which the recreation of the author’s communicative intention is not assumed.

The study aims to analyse the national ideas of the Alash intellectuals as reflected in the literary translations of fables from Russian into Kazakh. The focus is on how these translations embed and convey the principles of the Alash movement, including self-determination, autonomy, and cultural preservation. By examining the works of Baitursynuly and contemporary Kazakh literature, this study seeks to understand the role of literary translation in shaping national consciousness and identity.

2 Materials and Methods

Fables by Krylov and their artistic translations by Baitursynuly (2021), which were used for analysing the artistic, semantic, and structural processing of the fabled work when translated from Russian into Kazakh, were used in this study. Based on the contexts of the fables, the main tools of artistic processing in the implementation of ideas related to the Alash intellectuals were analysed. Thus, in this study, Russian, French, and Kazakh texts were compared with each other in terms of the linguistic and cultural specificity of literary translation from the source language into the target language.

At first, this study examined theoretical issues related to literary translations, including the following: intercultural interaction between the addressor and the addressee of the message, the relationship between the typology of the text and the translation strategies used, such as foreignisation and domestication, the use of linguistic, semantic and structural transformations in literary translation, and the restructuring of linguistic and cultural information. The study also addressed the main translation errors, technical capabilities, and flexibility in processing textual information.

After studying theoretical information and researching new developments in the field of literary translation, practical material taken from the fables of Krylov, and their translations by Baitursynuly (2021) were analysed. The analysis of the contexts highlighted the main components associated with transformations, including semantic, compositional, and artistic ones. Certain linguistic and cultural tools, such as the use of equivalent vocabulary, phraseological phrases and sayings, metaphorical constructions, and ironic overtones, were also analysed. The linguistic and cultural tools were used to build links between source and target texts to study how the main meanings of the source text are conveyed by the linguistic tools of the target language.

Alash ideas were identified through recurring themes that advocate for Kazakh autonomy and independence, emphasising self-determination and the right to self-governance, as well as the pursuit of a prosperous future for the nation through economic, social, and cultural development. Texts that ridicule or criticise authoritarian regimes by highlighting their oppressive nature, along with those that underscore the contributions and sacrifices of Kazakh intellectuals in the national struggle and promote art and science as vehicles for societal advancement, were marked as embodying these ideas. In contrast, Russian ideas were recognised by themes that reinforce the legitimacy and power of the Russian Empire or Soviet state, promote collective identity and socialist values, and emphasise state control over societal development through industrialisation and technological progress.

To ensure that these ideas were marked up consistently across the texts, a systematic methodological approach was employed. This involved identifying key phrases and terms associated with both Alash and Russian ideas in the source and target texts, followed by a thorough contextual analysis to capture subtle semantic nuances. The process included a comparative analysis of the semantic components, metaphorical and ironic elements, as well as structural transformations such as plot development, characterisation, and narrative techniques. Additionally, cultural elements – such as the use of equivalent vocabulary, phraseological expressions, and proverbs – were examined. By employing a predefined set of keywords and key phrases, the methodology ensured a reproducible and consistent markup of the ideological themes throughout the analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Features of the Formation of the Alash Party and Its Main Ideas

The Kazakh socio-political and national liberation movement called the Alash party was created by Baitursynuly and Dulatov in 1917 at the First All-Kyrgyz Congress held in Orenburg. It united Kazakh and Kyrgyz intellectuals, including groups of representatives of the Cadet Party, an ethnic Kazakh party formed in 1905. The newspaper Kazakh became the official body of the party, and Bukeykhanov became its chairman. The party was liquidated by the Bolshevik regime in 1920. The draft programme of the Alash party included the following ten points. Firstly, the main goal was to form the autonomy of the regions on a territorial and national basis within a single Kazakh unity. Among the Kazakh territories that were to form this community were the Bukei Horde, Ural, Turgai, Semipalatinsk, Zhetysu, Akmola, and Syry-Darya regions. Among the Kyrgyz territories, the national-territorial entity was to be formed by the counties of Ferghana and Samarkand provinces, and the volosts of the Altai province. Common ancestry, common culture, history, and language were considered the main principles.

This national-territorial association (autonomy) was given the name “Alash,” and its constitution was to be approved by the All-Russian Constituent Assembly. Semipalatinsk was proclaimed the seat of the Alash-Orda. The People’s Council of the Alash party was also elected to protect the borders of the autonomy from disintegration and anarchic manifestations. It consisted of 25 members, 10 of whom were minorities. All nations were guaranteed the rights of minorities, which was manifested in the proportional representation of all nations in state institutions. Cultural autonomy was also granted. All subsoil, water, and resources were owned by the autonomy. At the same time, the Alash-Orda undertook to create a people’s militia, convene a constituent assembly of the autonomy, and submit a draft constitution for the Alash. The Alash-Orda was also empowered to enter loans and negotiate with neighbouring blocks, and the right to conclude contracts was transferred to the assembly.

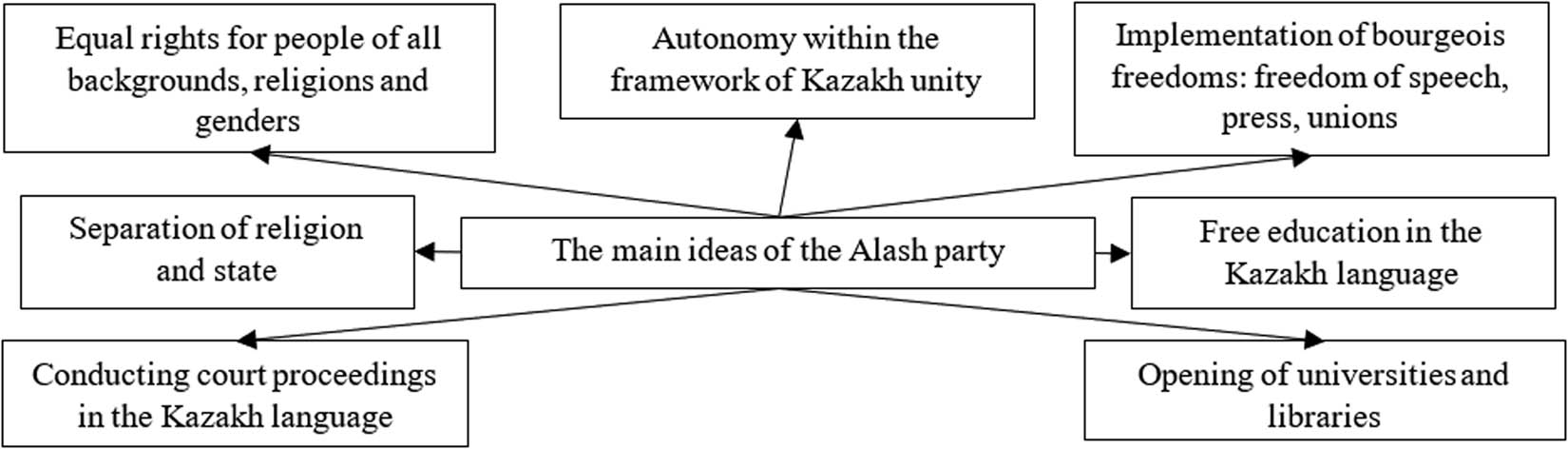

It should be noted that in the 1917 elections, the party received 262,404 votes and 43 parliamentary seats, thus ranking 8th among about 50 parties. Among the Alash intellectuals of the early twentieth century, one can single out such cultural figures as Baitursynuly, Dulatov, Bukeykhanov, Shokai, Tynyshpaev, and Yermekov. All of these people were highly educated and had deep knowledge of the world order. These are human rights activists, public figures, politicians, publicists, press publishers, poets, teachers, and academics. Their main goal was to raise the national spirit to the level of statehood, create a system of effective self-government, and modernise society along the path of national self-determination. Alash leaders could not accept class dictatorship in society and actively opposed the Bolsheviks, but due to the ignorance of the majority and the lack of a clear plan of action, this programme was defeated. Although the Alash party was defeated, the Alash leaders showed how Kazakhstan should develop, defending the principles of a democratic, legal, social state and European liberal values. The struggle of the Alash intellectuals was manifested through the defence of the rights to national culture and language, which were levelled by the Soviet authorities (Kalenova et al., 2024). Figure 1 shows the main ideas of the Alash party.

The main ideas of the Alash party. Source: compiled by the authors based on Kalenova et al. (2024).

Thus, the Alash project was developed covering such issues as the implementation of universal suffrage, equality of republics, democratic values, separation of church and state, and equal use of languages.

3.2 Reflection of the Principles of the Alash Intellectuals in the Fables of Baitursynuly

In literary translation, the artistic image is closely reconstructed based on the original text. Unlike technical translation, literary translation involves not literal translation, but artistic processing of the original phonetic, grammatical, and syntactic patterns (Kryeziu & Mrasori, 2021). In translation studies, a lacuna refers to a gap that arises when the target language lacks a lexeme to convey a specific concept present in the source language. For example, consider the Russian term “тocкa” (toska), which denotes a deep, existential melancholy that does not have a direct equivalent in English. In translating texts that include “тocкa,” translators might opt to retain the original term or provide an explanatory annotation. This example clearly illustrates how lacunae emerge due to the lag between available linguistic tools and the conceptual tools needed to express certain ideas (Rędzioch-Korkuz, 2023; Sigismondi, 2018). When translating literary texts, parameters such as preserving the author’s voice, style, and communicative intentions, overcoming cultural nuances, and conveying wordplay, metaphors, and symbols should be prioritised.

A fable is a literary work written in prose or verse and has a moral or satirical character (Abdykadyrova et al., 2023). From the point of view of structure, the fable contains a moral (moral teaching) and the main part in which people’s vices are ridiculed. The heroes of fables are often animals, whose images allegorically represent people. Among the key genre features of fables are allegorical meaning, typicality of the situation described, and ridicule of the vices and shortcomings of humanity. In the translation of the fable Krylov’s “Swan, Pike and Crayfish” in the artistic interpretation of Baitursynuly’s “Aqqw, şortan häm şayan,” the expansion of the content is noticeable: in the original, there are 26 poetic lines, and in the translation, there are only 48. Thus, the text has undergone significant changes. The author often uses a free interpretation of the fable’s moral.

For instance, the moral of the fable “When comrades do not agree, their business will not go well, and it will not be a business, but a torment” is translated into Kazakh in this way: “Jigitter, munan ğïbrat almay bolmas, Äweli birlik kerek, bolsañ joldas. Biriniñ aytqanına biriñ könbey, Istegen ıntımaqsız isiñ oñbas.” The literal translation in Baitursynuly is as follows: “Jigits, a lesson should be learnt: Comrades need unity, there will be no use if we do not become united in word and deed.” Thus, the author addresses the Kazakh people, who must unite to bring their long-held dreams of a free state to reality. This phrase reflects the Alash idea of self-determination of the nation and the way of its development.

When comparing Krylov’s original “The Crow and the Fox” and Baitursynuly’s artistic interpretation named “Qarğa men tülki,” the following compositional shifts can be noted: Krylov has the moral first and then the main part, while Baitursynuly swapped the order. The moral in the original text is laconic, mocking such a negative character trait as flattery: “The world has been told so many times that flattery is vile and harmful, but it’s all in vain, and the flatterer will always find a corner in the heart.” However, in the translation of Baitursynuly this concept is addressed in a narrower way in the context of the revival of the Kazakh nation: “Qarasaq, köp adamdar Tülki bolıp jür, Zalımdıq ötirik pen mülki bolıp jür” (“If we look at the case, a lot of people are Foxes, they embody oppressive lies and ownership”).

In Baitursynuly’s fable “Qasqır men qozı” (originally “The Wolf and the Lamb” by Krylov), the moral is significantly expanded by the author’s explanations, in particular, it is stated that the wolf is an allegorical image of a bad person, so he should not be admired: “Osınday jazıqsızdı jazğıratın Är jerde küştilerde bar ğoy qalıp. Qasqırdıñ zorlıq boldı etken isi, Oylaymın, onı maqtar şıqpas kisi. Naşardı talay adam talap jep jür, Böriden artıq deymiz onıñ nesi?!” (“There are powerful people everywhere who can destroy such an innocent man. The wolf’s actions were cruel, and I believe that it is the embodiment of a person who cannot be praised. Many bad people ask what we have that is better than a wolf!”). In the original text, the moral of the fable is more philosophical and generalised: “With the strong, the powerless are always to blame: We hear a lot of examples of this in history, but we don’t write history; we talk about it in fables.”

In the fable “The Lion and the Man” by Krylov, the reference to art is laconic, unlike the whole passage in Baitursynuly: “Art overcame power, and the poor Lion died.” The fable “Emenniñ tübindegi şoşqa” describes the importance of science for the full development of society: “Ğılımdı paydalanıp otırsa da, Sezbeytin sol paydasın nadandar bar” (“Even though they use science, there are ignorant people who do not feel its benefits”). Krylov presents the moral of the fable more ironically: “The ignorant man likewise in blindness scolds science and learning and all scholarly labours, not feeling that he tastes their fruits.”

Baitursynuly, a prominent Kazakh educator, translator, publicist, teacher, linguist, and politician, was one of the ideological enlighteners of the Alash movement. As a member of the Provisional People’s Council of the Alash Orda and the editor-in-chief of the socio-political newspaper Kazakh, Baitursynuly played a pivotal role in shaping Kazakh national consciousness. His collection of fables entitled “Qırıq mısal” (Forty Fables), published in 1909, is a significant work that draws from traditional stories and fables by de La Fontaine and Krylov. Baitursynuly’s fables serve as a critical commentary on Russia’s colonialist policy and the arbitrariness of its authorities. For instance, in the fable “Aqqw, şortan häm şayan” (The Swan, the Pike, and the Crawfish), Baitursynuly expands on Krylov’s original, highlighting the lack of unity and cooperation among different segments of society, which he attributes to the divisive policies of the colonial administration. The moral of the fable is transformed to emphasise the need for national unity and self-determination, directly critiquing the colonialist approach that fosters division and dependence.

In the fable “Qarğa men tülki” (The Crow and the Fox), Baitursynuly shifts the focus from a general critique of flattery to a specific condemnation of the corrupt and oppressive practices of the colonial authorities. The fable’s moral is reinterpreted to underscore the harmful effects of flattery and deceit in maintaining colonial power structures, thereby ridiculing the arbitrariness of the authorities. In the fable “Qasqır men qozı” (The Wolf and the Lamb), Baitursynuly expands the moral to include a critique of the legal and administrative systems imposed by the colonial regime. The wolf, symbolising the oppressive colonial authority, is portrayed as unjust and tyrannical, while the lamb represents the helpless and exploited colonised people. This fable serves as a powerful allegory for the injustices perpetrated by the colonial administration. Many of Baitursynuly’s fables emphasise the need to build Alash-Orda (Alash autonomy) as a means of achieving self-determination and escaping the oppressive colonial regime. The author’s main goal was to awaken the nation from ignorance and darkness, inspiring the Kazakh people to strive for independence and become a key player on the global stage. Through these literary devices and thematic expansions, Baitursynuly’s collection of fables effectively critiques Russia’s colonialist policy and ridicules the arbitrariness of the authorities, serving as a call to action for the Kazakh people to seek autonomy and self-determination.

3.3 Implementation of the Idea of Alash in Contemporary Kazakh Literature

Magauin (2007), a prominent Kazakh writer, publicist, novelist, and translator, is known for his deep exploration of Kazakh folklore heritage. In his novel “Zharmak,” Magauin introduces a postmodern approach that engages readers through a “game” of literary techniques. Published in Prague, the novel quickly garnered attention from critics, readers, and literary scholars alike. The title “Zharmak,” which means “yoke,” focuses on the life of Murat, a scientist studying the ancient history of the Kipchaks. The novel is rich in symbols, allegorical images, allusions, reminiscences, philosophical depth, and journalistic elements. It also features wordplay, doppelganger characters, parallel worlds, ironic passages, and grotesque elements, all of which present the spiritual life of Kazakh people through their cultural and literary heritage.

The plot revolves around manuscripts left behind by I. Kazakbai, which detail the ancient history of the Kazakh people. Murat, the protagonist, values these manuscripts for their truthful portrayal of the tragic realities faced by the Kazakh people. Murat, who has been restricted in his research on Kazakhstan’s independence for over 30 years, expresses disillusionment with the current system, criticising the press and the state of the National Academy of Sciences. The novel suggests that modern Kazakh society is in a state of degradation, marked by a slave-like mentality and a lack of true patriotism.

The ideas of Alash were also mentioned in the novel “Zharmak” by Magauin, in particular, at the beginning of the work it was stated that I. Kazakbai, the author of the manuscripts, was also a representative of the idea of Alash spirituality: “Bul oyqı-şoyqı, şïmay-şıtırıq jazbalar köpşilik jurt üşin elewsiz, bälkim mülde belgisiz qalamger, şın mäninde burınğı-soñğı alaş rwxanïyatındağı eñ alıp tulğalardıñ biri Ïman Qazaqbaydıñ arxïvinen tabıldı” (translation – “These amusing, humorous notes were found in the archive of Kazakbai, a writer unknown to the general public, but in fact one of the biggest personalities of Alash spirituality”). The description of life principles and values also emphasises the need to study the idea of Alash: “Bastapqı alaş oqığandarınıñ tağılımın tanığan, tar zamanda ösip jetken, äwelde 38-jılı, odan soñ 51-jılı, alğaşqısı on jıl, keyingisi tört jıl, – eñ önimdi, qayrattı kezeñin türme men lagerde ötkizgen, biraq jasımağan, qatayğan, äwelgi betinen taymağan, özgeşe tağdırlı, kemeñger kisi edi” (translation – “He learnt the lessons of Alash’s original teachings, grew up in difficult times, first at 38, then at 51, the first 10 years, the next 4 years, his most productive and courageous period was spent in prison and a camp, but he did not hide, did not harden, did not turn away from himself, he was a talented person with a different destiny”).

Thus, it is emphasised that the study of the ideas of the Alash intellectuals is necessary in the context of education. At the same time, it is pointed out that Murat is not sufficiently familiar with Alash, as he specialises in the study of ancient history and historical figures associated with it: “Şıñğıs xan, Batw xan twralı qanday oy-pikirdemin, Abılay xannıñ tarïxï qızmeti nede, Kenesarı degen kim – men jawaptan jañılmadım. Tek Alaş-Orda twralı suraqtan ğana jaltarğam. Estimedim, bilmeymin. Tarïxşı bolğanda… men basqa, arğı zaman tarïxınıñ mamanımın” (translation – “What I think about Genghis Khan and Batu Khan, what is the historical activity of Abylai Khan, aka Kenesara – I was not mistaken in my answer. I’ll just bypass the question of the Alash Horde. I have not heard; I do not know. As a historian. I am an expert in another, ancient history”). Alash was also mentioned in the context of the literature necessary to understand the basics of Kazakh history: “Baba tili” men “Jaña alaş” qostap, neşe märte qayıra soğıp, jerine jetkizgen. “Erkin qazaq,” “Alaş ädebïeti,” “Qazaq aydını,” “Gülstan,” …eñ ayağı “Awdan aqşamına” deyin jappay ün qosıp, dabır-dubırdı Alatawdan asırıp, Qaratawğa, odan äri Arqa men Atırawğa jetkizgen” (translation – “He added “Baba tili” and “Jaña alaş” and delivered it to him, playing it several times. “Erkin qazaq,” “Alaş ädebïeti,” “Qazaq aydını,” “Gülstan,” …and finally “Awdan aqşamına” made a huge noise, spread the noise beyond Alatau, up to Karatau, and further to Arka and Atyrau”).

The self-sacrifice of the Alash intellectuals for the sake of the Kazakh nation’s further development is also emphasised in the novel Zharmak by Magauin: “Ayasañ, meni aya, bar eñbegi qurdımğa batqan, bar ömiri zaya ketken. Alaştıñ azamatına obal. Mağan obal. Biraq sol ayaw men esirkewden mağan kelip keter eşteñe joq. Onsız da bitken adammın. Meniñ obalım – fänïde emes, baqïda. Arıdağı, aybarlı jurtına asqar tawday tirek bolğan arwaqtı babalarıma qalay körinem. Alaş ardagerleri qatarında atılıp ketken ülken äkemniñ betine qalay qaraymın” (translation – “If you have pity, have pity on me, all my work is ruined, all my life is wasted. Sin to the inhabitant of Alash. Concentrate on me. But nothing can come to me from this pity and intoxication. I have already finished. My problem is not science, but fate. How will I appear in front of my ghostly ancestors, who were a huge mountain of support for their noble people. How can I look at the face of my grandfather, who was shot among the veterans of Alash”).

The idea of Alash in contemporary Kazakh literature was also addressed in the context of intergenerational relations, i.e., the influence of Alash intellectuals on the history of Kazakhstan was studied: “Bayağı alaş qayratkerleri sïyaqtı, sol jolğa basıñdı tiktiñ demeyik, qadarıñşa küşiñdi jumsadıñ. Tw kötermeseñ de, tw bekiter tuğır dayındamaq ediñ. Yağnï, eldiñ eski tarïxın tiriltip, eñsesi basılğan jurtqa ötkenin tanıtıp, sanasına säwle tüsirip, bïik armanğa jetelemek ediñ” (translation – “Let’s not say that you put your whole life for this path, like other Alash figures, you spent all your energy. Even if you didn’t raise the flag, you were going to prepare a flag stand. That is, you wanted to revive the old history of the country, to show depressed people the past, to enlighten their minds and lead them to high dreams”). The need to preserve historical memory and educate society in a national context can be seen in the following context: “Alaş azamattarı köleñkede qalıp, alayaqtardıñ bağı köterilip tur” (translation – “The residents of Alash remain in the shadows, and there are more and more fraudsters”).

The novel also touches on the ideas of the Alash movement, highlighting that I. Kazakbai was a representative of Alash spirituality. The narrative emphasises the importance of studying Alash ideas in education and notes that Murat, despite his expertise in ancient history, is not well-versed in Alash. The self-sacrifice of Alash intellectuals for the development of the Kazakh nation is a recurring theme, underscoring their dedication and the need to preserve historical memory. The novel explores intergenerational relations and the influence of Alash intellectuals on Kazakh history. It stresses the importance of reviving the old history of the country to enlighten the minds of the people and lead them to higher aspirations. The need to preserve historical memory and educate society in a national context is evident, as the novel points out that the residents of Alash remain in the shadows while fraudsters gain prominence (Mussaly et al., 2022). Table 1 presents the key ideas of the Alash party in the works of Baitursynuly and contemporary postmodern literature.

Ideas of the Alash party are reflected in the works of Baitursynuly and the literary tradition

| Fables of Baitursynuly | Contemporary literature |

|---|---|

| Mocking the totalitarian regime and rights infringement | Connecting generations, past, present and future |

| Necessity of self-sacrifice by Alash intellectuals | Need to preserve historical memory and educate society |

| Need for independent Kazakh development | Idea of self-sacrifice for future generations |

| Importance of science for societal development | Study of Alash intellectuals in education |

| Self-determination and nation-building | Study of Alash ideas in spirituality and life principles |

Thus, it is possible to state that the texts under consideration contain many Alash ideas, including the need for self-determination of the nation, the unification of intellectuals to achieve common goals, and the development of the Kazakh nation in creative, spiritual, cultural, and intellectual terms. In addition, the author condemns and ridicules such phenomena as totalitarian regimes, lack of education, infringement of Kazakhs’ rights, and methods of forceful policy to achieve results. Notably, the linguistic and cultural approach to the thematic, structural, and artistic processing of the original stories reveals the Kazakh flavour and national identity in the texts under consideration. The analysis of the translation of literary texts determined that they use cultural, structural, semantic, linguistic, and other transformations.

The differences observed between the original Russian texts and their Kazakh translations can be attributed to several factors rooted in cultural, historical, and linguistic contexts. The significant expansion of the Kazakh texts in terms of structure reflects the translator’s intent to make the content more accessible and relatable to the Kazakh audience (Bashirov et al., 2024). This expansion often involves adding explanations and cultural references that resonate with the target readers, ensuring that the translated works are not just literal renditions but culturally enriched adaptations. The more specific meanings in the Kazakh texts, as opposed to the philosophical and generalised nature of the source texts, can be seen as a strategy to directly address the socio-political realities and aspirations of the Kazakh people. This approach aligns with the domestication strategy in translation, where the text is adapted to fit the cultural norms and expectations of the target audience. The use of metaphorical images specific to Kazakh linguistic culture further emphasises the importance of preserving national identity and ensuring that the translation resonates with the local audience. The source text’s implicit meanings and ironic overtones are replaced with more explicit and direct language in the Kazakh translations, reflecting the translator’s goal of clarity and impact. This shift can be interpreted as a response to the historical and political context of Kazakhstan, where direct communication and critique of totalitarian regimes are seen as necessary for national consciousness and development. The inclusion of proverbs, phraseological turns, and appeals in the Kazakh texts after artistic processing highlights the translator’s effort to integrate cultural elements that are familiar and meaningful to the Kazakh readers, thereby enhancing the text’s relevance and impact.

4 Discussion

In the context of literary translation, it is possible to state that the approach used was aimed at maximising the processing of the original texts for the Kazakh reader, ensuring that the translated works resonate deeply with the cultural and linguistic sensibilities of the target audience. This approach involves not just a literal transfer of words but also a nuanced adaptation that considers the unique historical, social, and political contexts of the Kazakh people. Sun (2022) discussed the role of the translator in the system of intercultural interaction between the author of the text and the addressees of the message. The peculiarity of literary translation is the transmission of multilevel and interrelated information, while the difficulties of translation lie in the plane of the literary untranslatability of certain structures, which leads to the reduction and transformation of texts. Thus, it should be noted that literary translation is aimed at Kazakhs, i.e., the interpretation of original meanings and plots is primarily aimed at specific recipients of the message.

The analysis of literary translation revealed that compared to the original texts, the texts in the target language were significantly expanded. Generalised and philosophical phrases in the original were replaced by clearer wording in the translated text. The connection between text typology and translation was revealed in the work of Gazaz (2016). In the example of literary translation, the ways of transferring the artistic and aesthetic components from the original text to the target text were considered.

Piper et al. (2022) demonstrated that translated literary texts differ not only in visual presentation but also in thematic content. The primary goal of literary translation is to convey what is termed the “geographical identity to the locals.”[1] Notable features of such translations include the expansion of moral dimensions and the precise specification of the original text’s meanings and messages. These processes result in various cultural, structural, linguistic, and other changes.

A special feature of translated texts is the use of so-called non-equivalent vocabulary (Madmarova et al., 2021). The analysis of the artistic translation revealed that the author did not intend to preserve the original colouring of Krylov’s fables but on the contrary aimed at using symbolic images, phraseological turns, and non-equivalent vocabulary of the Kazakh language. Mahmood and Ahmed (2021) addressed the problem of translating non-equivalent words from English into Kurdish in literary translation.

The study of intercultural inconsistencies in literary translation by Gavrilović and Kurteš (2022) was carried out in the context of the restructuring of linguocultures characteristics of the source text. For restructuring, the foreignisation method (to retain meaning from the original text, foreignisation means purposely breaching target language rules) was most often used. Thus, it is possible to state that the translation restructured the cultural information presented in the original to suit Kazakh realities.

Addressing literary translation within the framework of normativity, it is possible to state that it does not correspond to the translation postulates, as it deviates greatly from the original author’s concept. On this basis, the artistic texts under consideration can be considered original in terms of their underlying maxims and artistic techniques. Literary translation in the context of normativity was discussed by Toshtemirova (2023). In particular, this study focused on the norms that are approved or accepted by society in English–Uzbek translation. Thus, literary translations are subjected to considerable processing, which manifests itself not only in linguistic but also in structural and semantic transformations.

In literary translation, linguistic, structural, artistic, and semantic processing of texts was used, i.e., the original patterns were changed at all levels. Yousef (2012) named the following among the main problems faced by translators: linguistic, cultural, and human. The linguistic issues included phonological, lexical, semantic, and pragmatic errors. Cultural errors include translations of cultural expressions. The third group of errors is related to such parameters as cultural isolation and cultural hegemony. Rababah and Al-Abbas (2022) addressed various kinds of translation constraints, such as social, political, religious, and cultural. It was pointed out that general terms may have been used to refer to specific concepts, and certain words were added for explanatory purposes. Since the goal of literary translation is to implement a domestication strategy, errors or limitations should not be the point of emphasis but rather transformations of linguistic, cultural, and structural nature.

In the modern world, due to the era of globalisation and technologisation, there is a constant renewal of resources related to the artistic and semantic processing of texts (Sergeyeva & Bronin, 2024). The boundaries of literary translation in the work of Antonie (2022) were outlined in terms of intertextual and intercultural interaction in the era of digitalisation and globalisation of the world. Ruffo (2024) addressed the issues related to expanding the technical capabilities of the translator and reducing the number of contradictions associated with the implementation of translation strategies. However, automated translation systems for processing fiction texts would not be effective, as the transformations were carried out at deeper levels.

The flexibility in the process of processing fables was proved by the analysis of the literary translations under consideration. The results of the study by Ilyas (2022) showed that poetry translators used a variety of flexible principles to manage the artistic word. Huang and Valdeón (2022) addressed the peculiarities of literary translation in China, Latin America, Europe, and India. The analysis covered topics related to the role of translators, initiators of translation, gender translation, and the relationship between culture and text. It should be noted that in literary translations, culture has a significant impact on the text.

The study showed that the original texts have many more hidden meanings than the literary translation, as the author does not hide his main message, namely the need for the revival of the Kazakh people. Li and Li (2021) examine the concept of explicitness in literary translation, particularly through semantic explication in translations from Chinese into English by employing what they term “linking chains.” These linking chains are sequences of lexical units that function to create cohesive connections between ideas. For example, a translator might use transitional markers such as “firstly,” “secondly,” and “finally” to clearly sequence events, thereby forming a linking chain that guides the reader through the narrative. Furthermore, the study suggests that the reference fragments in the literary translation are not merely isolated lexemes but are better understood as manifestations of “linguocultures.” These linguocultures encapsulate culturally and historically embedded meanings that extend beyond the literal semantic content. An illustrative example from Kazakh culture is the proverb “Bir küni ashtyq, bir küni toy.” The proverb encapsulates a profound insight into the unpredictable interplay of fortune and misfortune. This meaning, deeply embedded in Kazakh historical and social experience, is not fully conveyed by a simple lexical translation.

5 Conclusions

The investigation of literary translations of Russian fables into Kazakh reveals several findings that underscore both cultural adaptation and national identity reinforcement. Firstly, the translations consistently expand upon the original texts by replacing abstract, generalised, and philosophical expressions with language that is more explicit and culturally resonant for the Kazakh audience. Secondly, the translated works foreground key national ideas central to the Alash intellectual movement. Furthermore, the translations emphasise the separation of religion and state, the right to education in the Kazakh language, the use of the Kazakh language in judicial proceedings, and the establishment of universities and libraries. Such themes not only critique totalitarian regimes but also celebrate self-determination and societal development through science and education. Thirdly, a dominant strategy observed in these translations is domestication. By adapting the source texts to align with the cultural and linguistic norms of the Kazakh audience, translators employ non-equivalent vocabulary, symbolic imagery, and culturally specific metaphors. This approach results in texts that are structurally expanded and thematically more explicit compared to their Russian originals, which tend to be more implicit and imbued with ironic overtones. Finally, the study highlights the broader role of literary translation as a tool for cultural preservation and the reinforcement of national consciousness. Contemporary Kazakh literature, reflecting on themes such as intergenerational connectivity, the preservation of historical memory, and the educational legacy of Alash intellectuals, demonstrates how translation can serve as a vehicle for both cultural enlightenment and national identity formation.

Despite these insights, the study is limited by the relatively narrow range of literature available for analysing the artistic realisation of the national ideas of the Alash intellectuals. Future research should consider comparative and contrastive studies involving translations between high-resource and low-resource languages, explore mechanisms for reducing semantic ambiguity, and further investigate effective translation strategies across different linguistic and cultural groups.

-

Funding information: This study was conducted within the framework of the scientific project of the grant funding of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan [AP19680272] “The worldview of the independence of poets-writers of the Abai region in the space of world thought (analysis of poets-writers)”.

-

Author contributions: Baurzhan Yerdembekov: conceptualisation, methodology, and original draft preparation. Assem Kassymova: data curation, formal analysis, and writing – review and editing. Karlygash Aubakirova: conceptualisation, formal analysis, and original draft preparation. Kuralai Tulebayeva: investigation, visualisation, and writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Abdykadyrova, S. R., Madmarova, G. A., Sabiralieva, Z. M., Bolotakunova, G. J., & Gaparova, C. A. (2023). Titulature in the text of the epic “Manas” and “Babur’s Notes” as a source of information about the social institutions of the Central Asian region. Advances in Science, Technology and Innovation, F1589, 505–510.Search in Google Scholar

Antonie, I. C. (2022). Framing literary translation in the 21st century. Synergies in Communication, 1, 42–49.Search in Google Scholar

Baitursynuly, A. (2021). Forty examples. https://adebiportal.kz/kz/multimedia/audio/axmet-baitursynuly-qyryq-mysal__365.Search in Google Scholar

Bashirov, N., Kamzabekuly, D., Daribayev, S., Sutzhanov, S., & Omarova, S. (2024). Intelligence of Kazakh: Idea of national liberation in literary works of Alash figures (XIX-XX). Scientific Herald of Uzhhorod University. Series Physics, 55, 1290–1297.Search in Google Scholar

Bronin, S., Kravchenko, O., Fedchenko, Y., & Kyselov, V. (2024). A method of generating ‘smart’ blocks of test questions in the learning process, adaptable to the learner’s personality, using neural network technology. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 911, 236–248.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, T. C., Alazzawi, F. J. I., Mavaluru, D., Mahmudiono, T., Enina, Y., Chupradit, S., Ahmed, A. A., Syed, M. H., Ismael, A. M., & Miethlich, B. (2022). Application of data mining methods in grouping agricultural product customers. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2022, 3942374.Search in Google Scholar

Fernández, D. M. M. (2024). Prospective research in the field of teaching creative skills to artificial intelligence. Interdisciplinary Cultural and Humanities Review, 3(1), 34–45.Search in Google Scholar

Gavrilović, Ž., & Kurteš, O. (2022). Opting within translation strategies in literary text translation among undergraduates. European Journal of Multilingualism and Translation Studies, 2(1), 22–30.Search in Google Scholar

Gazaz, H. A. (2016). The aesthetic function of literary translated text based on As-Safi and Reiss theories of translation. International Interdisciplinary Journal of Education, 5(8), 309–314.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Y., & Yu, H. (2023). Strategies and insights on managing cultural differences in literary translation. Lecture Notes on Language and Literature, 6(9), 45–52.Search in Google Scholar

Hansen, D., & Esperança-Rodier, E. (2023). Human-adapted MT for literary texts: Reality or fantasy? In NeTTT (pp. 178–190). HAL.Search in Google Scholar

Hoff, S. L., & Barboza, G. (2025). Languages, language, and linguists: The study of the diversity of languages according to Saussure and Benveniste. Bakhtiniana, 20(1), e65692e.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Q., & Valdeón, R. A. (2022). Perspectives on translation and world literature. Studies in Translation Theory and Practice, 30(6), 899–910.Search in Google Scholar

Ilyas, S. (2022). The parameters of poetry translation: A stylistic analysis of the linguistic and literary techniques used in the translations of the Odyssey and the Iliad. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 30(1), 13–33.Search in Google Scholar

Kalenova, T., Abdrakhmanova, G., & Kolumbaeva, Z. (2024). National projects of the Alash intelligence in the field of education. Bulletin of L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, 146(1), 67–86.Search in Google Scholar

Kongyratbay, T. A. (2022). Once again about the epic heritage of Korkut. Eposovedenie, 2022(2), 28–39.Search in Google Scholar

Kongyratbay, T. A. (2023). The ethnic character of the Kazakh epic Koblandy Batyr. Eposovedenie, 2023(1), 61–71.Search in Google Scholar

Kononchuk, I. (2024). Translation and adaptation: Intersecting relationships. International Journal of Philology, 28(2), 32–42.Search in Google Scholar

Kryeziu, N., & Mrasori, N. (2021). Literary translation and its stylistic analysis. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 17(3), 1651–1660.Search in Google Scholar

Kuusi, P., Riionheimo, H., & Kolehmainen, L. (2022). Translating into an endangered language: Filling in lexical gaps as language making. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 274, 133–160.Search in Google Scholar

Leonardi, L. (2024). Literature in and through translation: Literary translation as a pedagogical resource. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation, 7(3), 93–102.Search in Google Scholar

Li, X., & Li, L. (2021). Reframed narrativity in literary translation: An investigation of the explicitation of cohesive chains. Journal of Literary Semantics, 50(2), 151–171.Search in Google Scholar

Locatelli, A. (2021). Literary translation as performance. Theoretical questions and a literary analogy. Armenian Folia Anglistika, 17(1(23)), 96–107.Search in Google Scholar

Macken, L., Vanroy, B., Desmet, L., & Tezcan, A. (2022). Literary translation as a three-stage process: Machine translation, post-editing and revision. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation (pp. 101–110). European Association for Machine Translation.Search in Google Scholar

Madmarova, G. A., Abdykadyrova, S. R., Ormokeeva, R. K., Temirkulova, I. A., & Sagyndykova, R. Z. (2021). Lexical units objectifying the intercultural concept in “Babur-Nameh”. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, 314, 1065–1070.Search in Google Scholar

Magauin, M. (2007). Zharmak. https://abai.kz/post/50226.Search in Google Scholar

Mahmood, K. A., & Ahmed, E. A. (2021). Word equivalence: An investigation of fiction translation from English to Kurdish between 2003 and 2021. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Proceedings of KUST, Iraq Conference 2022, 1, 89–99.Search in Google Scholar

Manolachi, M., & Musiyiwa, A. (2022). Literary translation as a form of social and pedagogical activism. Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, 35(1), 173–201.Search in Google Scholar

Mardiana, L., & Ali, A. J. K. N. (2021). Literary translation analysis of Indonesian short story Apel dan Pisau. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation, 4(12), 172–180.Search in Google Scholar

Mizin, K., Slavova, L., Letiucha, L., & Petrov, O. (2023). Emotion concept disgust and its German counterparts: Equivalence determination based on language corpora data. Forum for Linguistic Studies, 5(1), 72–90.Search in Google Scholar

Muallim, M., Mujahidah, & Daulay, R. (2023). Unfolding translation strategy and ideology in literary work. Inspiring: English Education Journal, 6(1), 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

Mussaly, L. Z., Daurenbekova, L. N., Seidenova, S. D., Kartayeva, A. M., & Kelgembaeva, B. B. (2022). Influence of symbolism in world literature on Kazakh poets’ creativity. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 18(1), 447–457.Search in Google Scholar

Ovcharuk, O. (2024). Humanitarian strategies in culture in forming the newest tendencies in the Ukrainian cultural space. Culture and Contemporaneity, 26(1), 66–75.Search in Google Scholar

Piper, A., Erlin, M., Blank, A., Knox, D., & Pentecost, S. (2022). The predictability of literary translation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Digital Humanities (pp. 155–160). Association for Computational Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Rababah, S., & Al-Abbas, L. (2022). Overcoming constraints in literary translation: A case study of rendering Saud Al-Sanousi’s Saq Al-Bambu into English. Open Cultural Studies, 6(1), 260–271.Search in Google Scholar

Rędzioch-Korkuz, A. (2023). Revisiting the concepts of translation studies: Equivalence in linguistic translation from the point of view of Peircean universal categories. Language and Semiotic Studies, 9(1), 33–53.Search in Google Scholar

Ruffo, P. (2024). An exploration of their self-imaging discourse and relationship to technology. Translation in Society, 3(1), 87–103.Search in Google Scholar

Sankaravelayuthan, R. (2020). Lexical gaps and untranslatability in translation. Language in India, 20(5), 56–82.Search in Google Scholar

Sergeyeva, T., & Bronin, S. (2024). Co-creation of interactive E-courses by multidisciplinary teams of educators-researchers-practitioners-stakeholders. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 911, 225–235.Search in Google Scholar

Sigismondi, P. (2018). Exploring translation gaps: The untranslatability and global diffusion of “cool” get access arrow. Communication Theory, 28(3), 292–310.Search in Google Scholar

Stadnik, O. (2024). Cultural and sociological studies: Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary fields. Culture and Contemporaneity, 26(2), 30–38.Search in Google Scholar

Sun, Y. (2022). Literary translation and communication. Frontiers in Communication, 7, 1073773.Search in Google Scholar

Suo, X. (2015). A new perspective on literary translation strategies based on Skopos theory. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(1), 176–183.Search in Google Scholar

Toshtemirova, A. (2023). Features of literary translation. Central Asian Journal of Literature, Philosophy and Culture, 4(5), 50–54.Search in Google Scholar

Vaišnorienė, D. (2024). Visual storytelling: The case of the painting of St. Barbara in the church in Alėjai. Logos (Lithuania), 119, 171–182.Search in Google Scholar

Yousef, T. (2012). Literary translation: Old and new challenges. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies, 13(1), 49–64.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Y. (2021). Translation strategies and its implications for cultural transference. Open Access Library Journal, 8(5), e7469.Search in Google Scholar

Zhanysbayeva, A. P., Omarov, B. Z., Shindaliyeva, M. B., Nurtazina, R. A., & Toktagazin, M. B. (2021). Regional printed periodicals as an important link in the Country’s media space. Library Philosophy and Practice, 2021, 1–16.Search in Google Scholar

Zhumabekova, A. K., & Umirtasova, N. I. (2021). Translation methods within the strategy of direct translation of linguistic texts from English to Kazakh. Bulletin of Toraighyrov University, 2, 87–97.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction