Wittgenstein on Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams

-

Foivos Syrigos

Abstract

Wittgenstein’s comments on Freud’s work have been widely discussed. Scholars such as Bouveresse (1995) and Cioffi (2009) have explored Wittgenstein’s conception of the unconscious, while McGuinness (2002) examined their intellectual relationship, and Harcourt (2017) addressed Wittgenstein’s ties to psychoanalysis. Despite recent efforts to connect Wittgenstein’s work with psychology, little attention has been given to the subject that intrigued Wittgenstein most: dreams. His interest in hypnotic phenomena and dream interpretation significantly predates his engagement with Freud (cf. Monk 1990; McGuinness 1988).

This paper explores Wittgenstein’s engagement with dreams, primarily as reflected in his “Conversations on Freud”. This analysis will address issues related to the philosophy of science—such as evidence, explanation, and justification—as well as key concerns in Wittgenstein’s work, including his concept of meaning as use and his notion of change of aspect. While Wittgenstein ultimately rejected Freud’s theory due to its scientific and philosophical shortcomings, his admiration for it mirrored his regard for Darwin and Copernicus: not flawless, but profoundly generative.

1 The Power of Mythology

Concluding a conversation with Rush Rhees in 1946, Ludwig Wittgenstein commented on Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams: “There is an inducement to say, ‘Yes, of course, it must be like that’. A powerful mythology.” (LA 1967: 52; my emphasis.) The “mythology” Wittgenstein refers to is none other than Freud’s interpretation of dreams. Freud’s method of interpreting dream sym147bols, often assigning sexual content to them, did not appeal to Wittgenstein. He specifically characterized Freud’s interpretation as “bawdy of the worst kind—if you wish to call it that—bawdy from A to Z.” (LA 1967: 23) Given this strong criticism, why did Wittgenstein occupy himself with dreams and, specifically, with Freud’s theories?

The enigmatic nature of dreams, which many people find immensely appealing, was also of significant interest to Wittgenstein. This interest likely began much earlier than his acquaintance with Freud’s work and psychoanalysis. Although Wittgenstein might have been aware of Freud from an early age—having read Otto Weininger’s Sex and Character where Freud is mentioned—there are reasons to believe that the mysterious[1] nature of mental phenomena associated with dreams led him to try to self-analyze his dreams long before he read Freud’s work on the subject.

For instance, in Ray Monk’s book on Wittgenstein (1991: 276, 279), we find that Wittgenstein recorded and interpreted two of his dreams at the end of 1929. In contrast, it was not until late 1935 that Wittgenstein sent Maurice O’Connor Drury a copy of The Interpretation of Dreams as a birthday present, “telling Drury that when he first read it he said to himself: ‘Here at last is a psychologist who has something to say.’” (Monk 1991: 356)

Further evidence supporting Wittgenstein’s early interest in mysterious mental phenomena is provided by both Monk (cf. 1991: 77) and Brian McGuinness (cf. 1988: 189), the two major biographers of Wittgenstein, who describe his attraction to hypnosis. Following the “wave of interest in hypnosis in Cambridge” (McGuinness 1988: 189), Wittgenstein requested to be hypnotized to examine whether he would be capable, in that state, of solving difficult problems in logic that he was obsessed with at the time. Given that people can exhibit extraordinary physical abilities in altered states of consciousness through hypnosis, Wittgenstein wondered if this process might similarly enhance mental capacities.

As one might expect, the experiment failed completely. Wittgenstein was neither easily hypnotized nor capable of exercising his mental faculties while in hypnotic state. Nonetheless, trance states are among the states of consciousness (or close to consciousness) most akin to dream states that someone can be willfully led to. Consequently, I believe that his interest in hypnotism shows an indirect connection to his interest in dreams.148

A more direct link is provided by his correspondence with his sister Gretl in which they exchanged dream reports (cf. McGuinness 1988: 189). This occurred around the time of Wittgenstein’s hypnotic experiments. We know that Gretl attempted to get hypnotized as well, albeit unsuccessfully. Although the duration of their correspondence on these topics is unknown, it indicates their mutual interest in dreams.

Additionally, Alois Pichler (2018) recently presented two hitherto unknown dream reports by Wittgenstein—found in his Nachlass—revealing Wittgenstein’s interest in keeping a dream journal. Wittgenstein never sought to discuss his dreams with a specialist, preferring to make his own notes and analysis. His primary interest lay in the epistemological and methodological implications of Freud’s theory and his unexpressed theory of meaning.

For instance, Wittgenstein was interested in whether we can determine the meaning of symbols in a dream regardless of their use in the dream context. As we will see in this essay, Freud claims that the meaning of certain symbols—such as top hats—tends to remain consistent across various dreaming phenomena. By characterizing dreams as a kind of language, Wittgenstein seeks to demonstrate that Freud’s attempt to explain these symbols through historical and cultural analysis is ultimately misguided; what he should study instead is their expression in the different dream contexts.

Freud’s process of interpretation raises further issues. For instance, does the meaning of the initial dream—as experienced by the subject—align with the meaning derived through analysis? Or does the process of interpretation, with the change of aspect that takes place in it, significantly alter the dream’s original meaning? Beyond Wittgenstein’s interest in this mental phenomenon, his primary motivation was to explore the implications of Freud’s ideas in relation to his own philosophical concerns. It is in this context that we will consider Wittgenstein’s remark on dreams in this paper.

2 Key Concepts in Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams

2.1 The Unconscious

To understand Wittgenstein’s objections to Freudian theory, we first need to outline some of the key elements of Freud’s conception as expressed in The Interpretation of Dreams. Those topics have, of course, been thoroughly discussed in the literature. Here, I will present my own understanding of these issues, focusing mainly on Freud’s earlier texts, which are also the ones Wittgenstein likely read (cf. Bouveresse 1995: 4).149

The most central idea introduced in the book, and probably the one Freud is most famous for, is his conception of the unconscious. Although most people today talk about the unconscious in Freudian terms, this was probably not the case during Wittgenstein’s life. As Rosemarie Sand (2014) has convincingly shown, the existence of unconscious ideas was known (at least) since Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in the German speaking world. Using thoughtful metaphors to illustrate their views,[2] thinkers such as Christian Wolff, Johann Georg Sulzer, Johann G.E. Maass and Ernst Platner aimed to portray the function of an unobservable entity whose function influenced consciousness in a way not encompassed by the then prevailing Cartesian philosophy. Since for René Descartes all thinking is reduced to conscious thinking (cf. Whyte 1960: 55), these philosophers proposed conceptions of the mind which would accommodate the function of non-conscious entities within it.

It is hard to tell whether Freud was aware of any literature on the unconscious that preceded him, though there are instances in the Studies on Hysteria where he refers to Hippolyte Bernheim’s (cf. Freud and Breuer 1955: 67) post-hypnotic experiments, in which subjects followed instructions given during trance (hypnotic) states. When later asked about the motives for their actions, the subjects could not recall the orders they had been given and were left puzzled by their own behavior. Certainly, this was an explicit case of action guided by unconscious processes.

Setting aside the context of Freud’s discovery of the unconscious, Freud justified its existence by focusing on its different manifestations in both clinical and non-clinical cases. One of them is portrayed by his study of the so-called slips of the tongue (“Fehlleistung”). During psychoanalytic sessions as well as in everyday occurrences, Freud observed that slips of the tongue rarely result in mere nonsense, like ‘abracadabra’. On the contrary, careful examination of these slips reveals that they harbor hidden psychological meaning, conveying information that the subject suppressed due to its unpleasantness. Similarly, jokes in folklore—those that are part of traditional oral storytelling—often contain hidden meanings upon closer inspection.

During psychoanalytic sessions, patients lie on the couch and engage in free association (a process called “Freier Einfall” [Freud 1953a]), often making connec150tions that initially seem unrelated or even contradictory. In all these cases, individuals find themselves responsible for actions they did not consciously intend, and often struggle to comprehend why these slips or associations occurred in the first place. Exploring these phenomena is central to psychoanalytic practice and will be discussed in detail later. The crucial question for the analyst, particularly for Freud, is how to structure clinical practice to be optimally effective for the patient. In other words, is there an optimal method for delving into the patient’s mind, an ideal approach to investigating the unconscious?

Freud observed that this method is none other than the interpretation of dreams. While dreaming, we are not active agents in the usual sense, but we are active in that our mind selects what we experience—making us, in a way, responsible for[3] what we see in our dreams. Unlike many of his predecessors and contemporaries, Freud did not view dreams as somatic processes devoid of psychological content, not requiring interpretation. Instead, he considered dreams to be psychic phenomena that hold significance and contribute to the individual’s psychological well-being.[4] But why did Freud prioritize dream interpretation over other available therapeutic methods such as hypnosis?[5]151

A first answer is that the difference between psychoanalysis and other therapeutic methods (such as hypnosis) is revealed to the psychoanalyst through clinical practice. In this sense, it is the insights gained through dream analysis which make this method more favorable than the others available. However, one does not need to be a specialist to notice that this answer is far from convincing to the independent reader. After all, why abandon physiological treatments and explanations that were systematically used during that period (and still are) and ascribe psychological content to dreams? The defense of this claim is one of the main goals of the Traumdeutung. It is Freud’s analysis and explanation of the clinical cases that are expounded in the book that will (hopefully) convince the readers to alter their views on the nature of treatment and, by extension, their views on the realm of the mental itself. Despite the complexities and the inchoateness that characterize a new field of study, Freud seems certain about the success of his interpreting method. In his unique, grandiose way, he noted: “The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.” (Freud 1953b: 608)

2.2 Every Dream is a Wish-fulfillment

As every serious researcher of a topic ought to do, Freud extensively surveyed the literature on dreams written before him. This includes ancient writers such as Aristotle, Homer, Artemidorus of Daldis, Cicero, and Lucretius, up to his contemporaries. Notably, almost one-fifth of the book is composed of what Freud calls “The Scientific Literature on the Problem of Dreams”.[6] After finishing this section, Freud starts to present his own views on the subject under the section called “The Method of Interpreting Dreams”. What is most striking in this chapter is the way it ends and, specifically, its very last sentence. Freud famously concludes his early exposition of his method by writing that: “When the work of interpretation has been completed, we perceive that a dream is the fulfilment of a wish.” (Freud 1953a: 121)

The importance of this assumption is so great that one can see the book as consisting of one long argument: the goal of the book is to support its main claim, namely that every dream is a wish-fulfillment. Of course, every person has experienced nightmares and other kinds of unpleasant dreams which make this claim 152seem rather foolish. Freud, however, is convinced that the elaboration of his theory will prove that, after the removal of repressions and other inhibitory mechanisms that exist in the mind (more on these later), each dream’s goal is to fulfill a wish. Before Freud, no one had ever tried to show the universality and necessity of the widely known phrase about unrealistic goals: the colloquial expression “Not even in your wildest dreams” will be confirmed (at least in Freud’s mind) in every dream analysis that is contained in the book.

It is hardly surprising that this proposition attracted strong criticism, as it implies Freud had uncovered the fundamental nature of dreams. Although many scholars have presented their own interpretations of dreams, Freud’s claim appears to assert a definitive answer—at least with respect to their essence. It is tempting to draw a parallel here with Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, where Wittgenstein initially believed he had resolved all philosophical problems, only to later revise his views. Similarly, Freud regarded his insight as revolutionary. He famously remarked: “Insight such as this falls to one’s lot but once in a lifetime.” (Freud 1953a: xxxii)

2.3 Dream Distortion

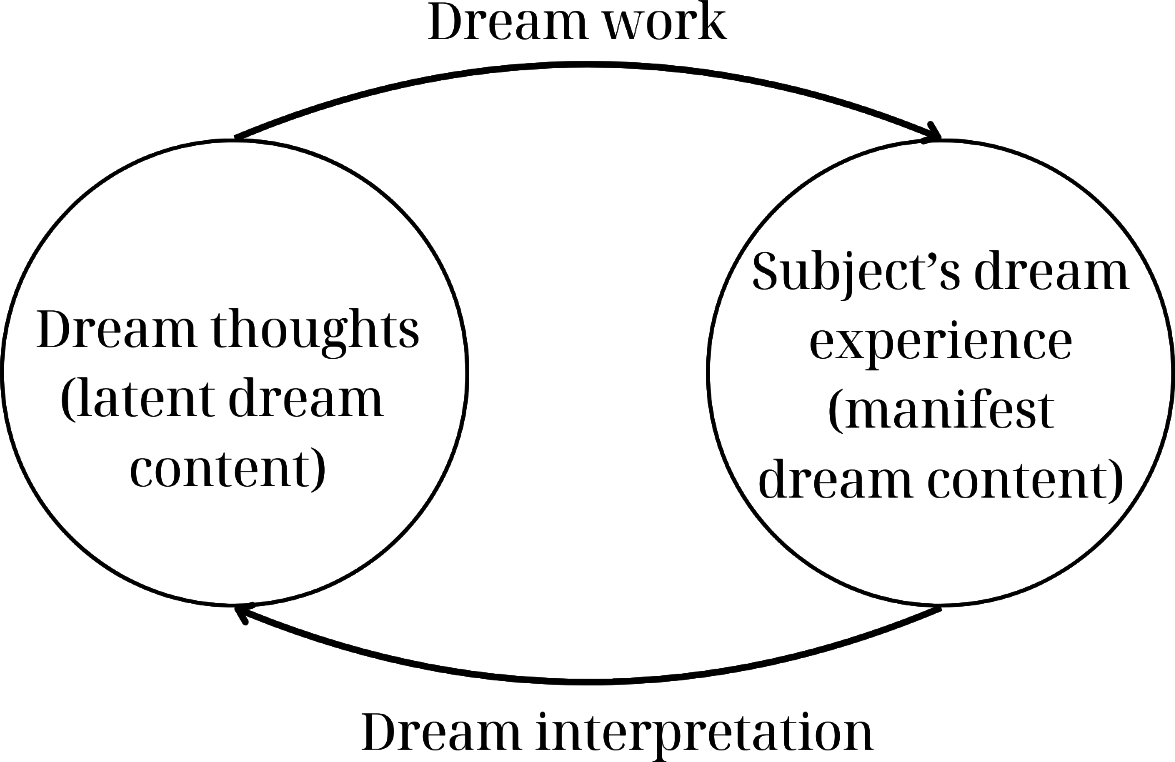

After Freud laid down his major claim, i. e., that every dream is a wish-fulfillment, he had to prove that this is also the case in every kind of absurd dream that one experiences. The most common dreams of this kind are nightmares and anxiety dreams. Freud proceeds in his Traumdeutung with a chapter called “Distortion in Dreams”. It is there that Freud introduces his distinction between the manifest and latent dream content, a distinction that is supposed to show that the wish-fulfilling character of dreams does not contradict our everyday experience. The manifest content refers to the dream as it is experienced by the subject during sleep, while the latent content encompasses the hidden, unconscious meaning of the dream, which is constituted by the dream-thoughts hypothesized to be on the dreamer’s mind at the time, albeit unconsciously.

Except in some rare cases, Freud believes that wishes are fulfilled in the latent part of the dream, though it is through the dream work that the dream-wishes unfold (more on this later). Freud’s sole methodological aim here is to shore up the possibility that his proposal is correct.[7] Without the necessary distinctions, his the153oretical framework would lack a solid foundation, and the manifest-latent distinction is specifically designed to serve this purpose.

Still, we lack an account of how—and why—this distortion occurs. Freud connects this issue with a related one: Why is it that “dreams with an indifferent content, which turn out to be wish-fulfillments, do not express their meaning undisguised?” (Freud 1953a: 136) If a dream is not distressing, as is the case with most dreams of a healthy individual, then why is there not an explicit wish-fulfillment in these instances? As Freud aims to demonstrate with his own specimen dream (the so-called “Irma’s dream” [Freud 1953a: 107 – 108]), dreams that seem indifferent at first may hold psychological significance for the individual. Freud’s analysis of Irma’s dream showed that it satisfied a number of his wishes (such as confirming that he is a good doctor and not responsible for the persistence of Irma’s pains [Freud 1953a: 118]), leading Freud to observe that these are the same wishes that constituted the motive of the dream. This leads us to the identification of the first agency responsible for distortion in dreams: the mind’s natural inclination to satisfy unfulfilled wishes during sleep.

Freud labels the second agency “censorship” (Freud 1953a: 142 – 143); its goal is to stop forbidden thoughts to bypass the barriers of consciousness. Because these barriers weaken during sleep, dream thoughts can then enter consciousness, albeit disguised due to the suppression of the censor. To illustrate this process, Freud draws a parallel with the political climate of his time, when writers used their ingenuity to express ideas in ways that evaded censorship (Freud 1953a: 141 – 42).

Freud’s line of thought is as follows: First, there is a motive for action—a desire or wish that seeks expression. If a wish seeks expression, it requires a means to be expressed. In the dreamer’s case, this is a dream; in the political writer’s case, it is presenting her ideas verbally or in writing. To avoid censorship, the political writer must use creativity and ingenuity. How can we explain the transformation of the wish in dreams? This involves dream-work.154

2.4 The Dream-work

Regarding the reason why wishes are transformed in dreams, Freud’s account is straight-forward: the distortion of the wish results from a conflict between two opposing forces—one that seeks to satisfy a wish and the other, the motive of censorship. Freud’s explanation would not be convincing without addressing how the dream is distorted, which involves the concept of dream-work (cf. Freud 1953a: 277 – 338 & Freud 1953b 339 – 488). Dream work is a complex and extensive part of Freud’s theory, consisting of five distinct processes. Some of these processes operate simultaneously, and some may be applied multiple times to the dream content. Gaining an understanding of these processes is essential for grasping Freud’s ideas, and we will briefly outline each of these steps. However, our discussion will not be exhaustive.

The first of these processes is condensation (cf. Freud 1953a: 279 – 305). Condensation refers to the process by which the length of the dream thoughts is significantly reduced, resulting in the dream content. The dream content is the dream that the subject experiences, while the dream thoughts correspond to the latent part of the dream, which is revealed through analysis. If we carefully observe a case of dream analysis (one of the many included in the Traumdeutung), it becomes apparent that the analysis covers many more pages than the dream itself. Although there are various reasons for this reduction, Freud infers that there must be a mental function responsible for this outcome: that is condensation.

We can make a few remarks about this process. First, condensation can occur in two ways: by fusion and by omission (cf. Michael 2015: 11). Omission refers to the process by which several dream thoughts are excluded from the dream content. This exclusion may be due to physiological reasons (such as amnesia) or psychological ones (such as censorship). From a psychoanalytic perspective, fusion is more significant. This process involves several dream thoughts being combined into a single element of the dream content. This not only reduces the size of the dream content but also allows the psychic importance of the combined dream thoughts to be transferred to a single element. This results in a paradoxical situation where an idea or object in the dream content seems much more significant than it actually is (as it exists in the underlying dream thoughts). Dream interpretation is needed to uncover the reasons for this shift in meaning, which is linked to another process of dream work known as displacement (cf. Freud 1953a: 305 – 310).

Displacement can be understood in two ways: as the displacement of words or as the displacement of psychic intensity. When the latter is combined with condensation, displacement of psychic energy occurs. Let us first consider displacement in the context of words. Freud suggests that words sharing some superficial similarity can be substituted during dreams. This process is akin to what happens in slips of 155the tongue, where the resulting word bears a linguistic resemblance to the word initially intended. The most intriguing cases of displacement are those in which both forms of displacement—words and psychic intensity— are combined. A full analysis of cases of displacement would require a lengthy discussion, which we will not undertake here. Instead, let us turn to two other functions of dream work: dramatization and symbolization.

Dramatization, formally termed “Considerations of Representability” (Freud 1953b: 339−349), refers to the process by which dream thoughts are translated into visual imagery. Freud emphasizes that “[a] dream-thought is unusable so long as it is expressed in an abstract form” (Freud 1953b: 340). This transformation from abstract ideas to pictorial representations enables dream thoughts to connect more fluidly with other unconscious ideas. The metaphorical language that characterizes dreams allows these dream thoughts to transcend their immediate meanings, creating connections that would be impossible through mere verbal articulation. Freud contrasts this process with symbolization, where the meaning of a symbol is determined arbitrarily by the interpreter (cf. Freud 1953b: 342).

Symbolism is one of the most—if not the most—contested aspects of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. Although Freud initially addressed the topic briefly in the first edition, he later expanded on his ideas as interest in the subject grew among other psychoanalysts. Freud asserts—an argument that would become a focal point of Wittgenstein’s critique—that certain symbols have universal meanings across all dream contexts. Common examples include extended objects (such as swords, pipes, or sticks) symbolizing the phallus and containers (like boxes or tables) representing the uterus. However, other symbols are highly individualistic or specific to a single language or culture (cf. Freud 1953b: 684).

This raises an intriguing question: if we expand our understanding of dream symbolism, could we eventually develop a kind of lexicon to decode any enigmatic symbol in a person’s dream? This was a prevalent belief in ancient times, where interpreting dreams was often seen as a process akin to cryptography. According to this line of thought, if one possessed the right key, they could unlock the meaning of any symbol.

Although Freud is often accused of subscribing to this view, he emphasized that context is far more important than mere knowledge of symbols. He argued that dream symbolism should be used as a tool for the interpreter, not as a replacement for the entire process of dream analysis. Beyond the individual symbols and fluctuations in the use of universal ones, one can never be certain whether a particular element in a dream should be interpreted symbolically or literally. Furthermore, Freud asserted that the entirety of a dream’s content should never be interpreted solely through symbolic means.156

A knowledge of dream symbolism, Freud admitted, can help translate certain components of the dream, but it does not replace the need for applying the technical rules of interpretation. It serves as a valuable aid, especially when the dreamer’s associations are insufficient or break down altogether (cf. Freud 1953b: 684−685).

The processes of condensation, displacement, dramatization, and symbolism constitute the core functions of the dream-work. These mechanisms aim to explain how underlying dream-thoughts are transformed into the dreams one experiences. Freud provides extensive detail in describing how these transformations occur. However, he introduces an additional layer to the dream work, one that operates on a meta-level: this is the process known as secondary revision (cf. Freud 1953b: 488 – 508).

Secondary revision is responsible for reshaping the dream into a coherent and comprehensible narrative, ensuring that the dream, despite its often fragmented and illogical nature, can still be grasped by the dreamer upon waking. While dreams may still exhibit logical gaps and inconsistencies, secondary revision organizes the material into something more understandable and seemingly coherent. In this way, it serves as a final stage of processing, refining the fragmented elements and striving to produce a more cohesive experience.

If we were to illustrate the processes involved in dream transformation, as outlined in this introductory part, it would appear as follows:

Of course, this illustration leaves certain important aspects of psychoanalytic theory, such as transference, unaddressed. Nevertheless, I believe it captures the key elements of Freud’s dream interpretation necessary for understanding and critically evaluating Wittgenstein’s remarks on Freud. Let us now turn to the text where most of Wittgenstein’s comments on Freud are found: “Conversations on Freud”.157

3 “Conversations on Freud”

3.1 The Absence of Clear Guidelines in Interpretation

In general, Wittgenstein’s remarks on Freud are scattered throughout his corpus. Among the various remarks on Freud and psychoanalysis inWittgenstein’s works, some of the most insightful reflections on this subject are published under the title “Conversations on Freud”. These consist of dialogues with his student and friend Rush Rhees, spanning from the summer of 1942 to 1946. Rhees has provided transcripts from four conversations in total[8] that were exclusively dedicated to Freud, psychoanalytic theory, and psychology in general. The most frequently recurrent theme in these conversations is Freud’s interpretation of dreams and Freud’s methodology of analyzing them, which will be the focus of our discussion in this section.

Let us start with the first conversation of these transcripts, where Freud’s theory of dreams is mentioned for the first time. Wittgenstein notes:

Freud’s theory of dreams. He wants to say that whatever happens in a dream will be found to be connected with some wish which analysis can bring to light. But this procedure of free association and so on is queer, because Freud never shows how we know where to stop—where is the right solution. Sometimes he says that the right solution, or the right analysis, is the one which satisfies the patient. Sometimes he says that the doctor knows what the right solution or analysis of the dream is whereas the patient doesn’t: the doctor can say that the patient is wrong. (LA 1967: 42)

For Wittgenstein, Freud is not clear as to how the right interpretation of the dream will be decided. As he explicated in the previous passage, the problem is twofold: On the one hand, Freud seems to lack a ‘decisive’ point, a point in therapy which will indicate that the interpretation of the dream is completed, and, on the other, there is an uncertainty regarding the authority on the right analysis of the dream. Is it the patient, the analyst, or both? In this section we will examine, first, if Wittgenstein’s criticism is justified and, second, if this criticism can be fruitful in illuminating complex issues regarding psychoanalysis’s scientific status.158

At first glance, Wittgenstein makes a good point. If one goes through the Interpretation of Dreams, Freud never states explicitly when one should stop when interpreting (parts of) a dream. A methodology, a “guideline”—as the title of this section implies—is missing. Is this a major shortcoming of Freud’s theory? I think not.

If we take psychoanalysis as a purely theoretical endeavor, then one might really complain about its ‘looseness’ regarding specific rules and methodology. This view is endorsed by Freud’s commitment of promoting the scientific status of psychoanalysis. As we saw in the previous section, Freud contends that he will provide a proof[9] that every dream is interpretable.

Even if Freud falls short on these standards, it is doubtful that we can write off his theory due to its lack of a ‘clear’ methodology. Most of our current science does not have this kind of methodology, i. e., specific instructions that even a novice could follow. Rather, science takes place in the context of scientific practice, where new scientists find their feet in the field by internalizing exemplars instead of memorizing and following strict guidelines. It is through the novice’s blending into the scientific community that she learns how to practice her profession effectively.

Could this reasoning also apply to Freud’s case? Again, it depends on how we regard psychoanalysis. If we regard it as a therapeutic practice, as Freud does in the majority of times, his view seems justified. The structure of the book also vindicates this idea. His work contains more than 60 of his specimen dreams, and the only reason for this choice is to show—by means of real cases—how his theory is applied in solving concrete problems. If he shows that his theory can indeed be successful in interpreting dreams, then the ‘lack’ (if one can call it that) of an explicit methodology can be overcome. He does not demand blind faith in this project; he also invites the reader to try his theory in her own dreams, and one could reasonably argue that the main reason that this technique/procedure remains relevant today is that it is—at least sometimes—successful.

That said, Wittgenstein would seem naive if he regarded psychoanalysis as a purely theoretical endeavor, demanding the rigor, e. g., of the natural sciences. Wittgenstein remarks on this point:

When we are studying psychology we may feel that there is something unsatisfactory, some difficulty about the whole subject of study—because we are taking physics as our ideal science. We think of formulating laws as in physics. And then we find we cannot use the same sort of ‘metric’, the same ideas of measurement as in physics. […] And yet psychologists want to say: “There must be some law”—although no law has been found. (Freud: “Do you 159want to say, gentlemen, that changes in mental phenomena are guided by chance?”) Whereas to me the fact that there aren’t actually any such laws seems important. (LA 1967: 42)

It is this ‘open’ character of interpretation, one that is not bound by any laws like in natural sciences, that makes psychology of special interest to Wittgenstein. Surprisingly, he seems to agree with Freud on this issue, as the lack of methodology enhances this non-strict attitude on interpretation. The philosophical significance of this point and its influence in the psychology of the analysand constitutes a focal point for Wittgenstein and will be addressed in detail later.

Before moving on to the next section, it is worth making a final remark on this discussion. The fact that Wittgenstein touched on a significant issue regarding Freud’s methodology in the Traumdeutung is indicated by Freud’s return to the issue in a later date. In an essay called “Remarks on the Theory and Practice of Dream-Interpretation” (Freud 1961a), Freud draws an analogy between the process of interpreting dreams and that of completing a jig-saw puzzle (cf. Freud 1961a: 116). Just like there is no alternative solution when the latter is completed, the same is true with the interpretation of dreams. Again, it might be objected that Freud has ultimately failed in providing a convincing account of knowing “where to stop—where is the right solution” as Wittgenstein[10] remarked. But we cannot delve into this issue here.

3.2 Evidence and Explanation

Setting aside the lack of ‘decisive’ points in interpretation, what is particularly important to Wittgenstein is how Freud justifies his choice of the correct analysis. Since Freud claims that he provides a proof that this theory is true (i. e., that it unravels the patient’s unconscious wishes and desires), one must then seek evidence that will validate this theory. Freud asserts that such evidence can be found, particularly in his work The Interpretation of Dreams. However, as we will explore in this section, Wittgenstein raises doubts about the existence of such evidence and questions the validity of Freud’s methodology.

Resuming their previous conversation on Freud, Wittgenstein remarks to Rhees:

The reason why he calls one sort of analysis the right one, does not seem to be a matter of evidence. Neither is the proposition that hallucinations, and so dreams, are wish fulfillments. 160Suppose a starving man has a hallucination of food. Freud wants to say the hallucination of anything requires tremendous energy: it is not something that could normally happen, but the energy is provided in the exceptional circumstances where a man’s wish for food is overpowering. This is a speculation. It is the sort of explanation we are inclined to accept. It is not put forward as a result of detailed examination of varieties of hallucinations.

[…] Take Freud’s view that anxiety is always a repetition in some way of the anxiety we felt at birth. He does not establish it by reference to evidence—for he could not do so. […] Freud does claim to find evidence in memories brought to light in analysis. But at a certain stage it is not clear how far such memories are due to the analyst. (LA 1967: 42−43)

Wittgenstein addresses many aspects of Freud’s work within the realm of philosophy of science and concerning internal issues of psychoanalytic theory, such as the issue of the accurate recollection of memories in clinical practice. The latter, being primarily linked to the unconscious, falls outside the scope of this discussion. Our focus in this section is to examine Wittgenstein’s remarks on Freudian methodology and explanation.

Let us start with Freud’s theory of hallucinations. As discussed earlier in this paper, Freud views dreams as inherently fulfilling wishes, and he extends this idea to hallucinations as well. Implicit in Wittgenstein’s earlier remark is the economic aspect of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, where psychic elements (such as needs) are quantified by the amount of energy they generate. As described in Wittgenstein’s passage above, for a hallucination to occur a significant amount of energy must somehow be produced within the organism. Since neurons are reflexive in nature and require strong stimuli to be activated,[11] Freud concludes that some161thing internal to the organism must trigger this response. In the case of a starving person, this internal cause could be the subject’s “overpowering” wish for food.

This reasoning falls within Freud’s metapsychology, and understanding it will enable us to critically evaluate Wittgenstein’s remarks on hallucinations. As is well known, Freud attempts to justify his explanations using results from a variety of domains, such as sexology, evolutionary biology, anthropology, folklore psychology, etc. However peculiar this may sound to a modern-day reader, this was something rather usual in Freud’s era, and, in a sense, in accordance with its scientific principles (cf. Kitcher 1992: 109 – 111). The question that arises now is the following: Should we regard Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams as a fundamental text on which the rest of Freud’s theory has to be grounded, or, alternatively, should we consider Freud’s theory as an interdisciplinary achievement from which his theory of dreams follows naturally?

Most of Freud’s followers would argue for the former position, while a few scholars, such as Kitcher (1992), advocate for the latter. The significance of this dilemma lies in the fact that if we accept the view that Freud’s interdisciplinary approach is primarily theoretical—where dream theory is implied—then Freud does not need to examine a wide range of hallucinations to support his claim about their function, as Wittgenstein suggested earlier. Instead, Freud would first establish that hallucinations and dreams are essentially identical and then proceed to analyze various types of dreams, as he indeed does throughout the rest of his work.

That said, is Wittgenstein’s criticism of Freud’s account of hallucinations justified? I believe it is. While “hypnagogic hallucinations” may share some characteristics with dreams,[12] hallucinations and dreams are generally distinct mental phe162nomena. One key difference is that dreams are experienced by all healthy individuals (even if they are sometimes forgotten), whereas hallucinations are typically linked to medical or psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia. Additionally, hallucinations often occur without external stimuli, whereas dreams can be influenced by the individual’s environment during sleep, such as external sounds or changes in temperature. Thus, a proper understanding of the function of hallucinations requires direct observation and clinical study, as Wittgenstein rightly pointed out in the previous passage.

Building on this, Wittgenstein further argued that Freud needed to examine a variety of hallucinations in order to substantiate his claims; without such empirical backing, Freud’s account would remain mere speculation. According to Wittgenstein, speculation is “something prior even to the formation of a hypothesis” (LA 1967: 44). Does this constitute a fair critique?

Wittgenstein also implicitly distinguished between different types of evidence and their possible identifiability in supporting Freud’s statements; whereas hallucinations constitute mental phenomena that can be observed, Freud’s remarks on birth anxiety form untestable propositions since, according to Wittgenstein, it is impossible to find evidence to support this hypothesis. Following Wittgenstein, we will examine these issues separately, focusing mainly on his notion of speculation.

Although one can rarely reflect on her own hallucinatory experiences, it is possible for a scientist to observe and study different manifestations of this mental phenomenon on another individual. As we previously noted, Freud never actually recorded cases of hallucinations, as he thought it would suffice to study dream cases. One might, however, question whether Freud’s theory of wish fulfillment in dreams is more than mere speculation. A close reading of Wittgenstein’s earlier conversation with Rhees reveals that he discusses “hallucinations, and so dreams, as wish fulfillments” (LA 1967: 42). Wittgenstein’s wording suggests that the term “speculation” might apply not only to hallucinations but to dreams as well.[13] Therefore, if we assume Wittgenstein’s critique extends to dream interpretation, we should consider whether both cases—hallucinations and dreams—can essentially be regarded as speculative.163

Given the limited evidence Freud presents to support his claims about hallucinations, one might reasonably argue that his account is largely speculative. But does the same apply to his method of interpreting dreams under similar standards, such as the lack of evidence? Considering Freud wrote over 600 pages to substantiate his claims and analyzed more than 60 dream cases,[14] can we still categorize his work as merely speculative? What is Wittgenstein’s notion of a (scientific) hypothesis, and how does it differ from Freud’s approach?

We get an idea of an answer from another discussion with Rhees, this time dated in 1943:

On the other hand, one might form a hypothesis. On reading the report of the dream, one might predict that the dreamer can be brought to recall such and such memories. And this hypothesis might or might not be verified. This might be called a scientific treatment of a dream. (LA 1967: 46, my emphasis.)

Let us explicate the methodology that Wittgenstein describes here. First, one must formulate a research hypothesis that is subject to critical inquiry based on the available evidence. The hypothesis in our case is Freud’s conjecture that “every dream is a wish-fulfillment”. Next, evidence must be gathered to test this hypothesis. In our case, this evidence consists of the dream report provided by the dreamer and the memories the dreamer recalls. Wittgenstein distinguishes between the dream report—free of any comments and value judgments—and the memories and associations that the dreamer is brought to during the analysis. If the dream is shown to be a (disguised) wish-fulfillment, Freud’s hypothesis is confirmed; otherwise, it is refuted.

Although Wittgenstein himself is not particularly interested in science—marking a significant difference between his and Freud’s approach to the study of dreams—he suggests this method as a proper scientific approach. In Wittgenstein’s view, if Freud seeks to treat dreams scientifically, as he claims, he should adopt a 164version of the hypothetico-deductive method (broadly conceived) in his investigation.

Now that we have unraveled Wittgenstein’s proposal, one of the things that we should examine is if it is, in fact, tenable. Can the hypothetico-deductive method (broadly conceived) be used to test Freud’s conjecture and, if so, does it differ significantly from Freud’s method?

To address these issues, let us examine Wittgenstein’s suggested methodology step by step. First, Freud’s hypothesis is clearly formulated, explicitly stating the content and purpose of a dream.[15] Problems arise, however, when we consider the evidence provided by the dreamer.

An initial issue is the accuracy of the subject’s recollections: does the dreamer provide an accurate and precise account of the dream they had the previous night? Closely related to this is the credibility of the evidence: can we trust that the dreamer has accurately reported their dream?

We will begin with the issue of accuracy, as it seems to present fewer conceptual problems than credibility. When discussing dream reports, there is an implicit assumption that dreams are in principle recallable. Therefore, when evaluating evidence in dream interpretation—which consists of the dream reports themselves—we assume that the subject can recall and effectively communicate the entire dream, either verbally or in writing.

However, upon reflection, many people might claim they had a dreamless sleep the previous night. Yet, scientific evidence shows that everyone dreams,[16] the reason some people forget their recent dreams is due to the natural suppression of memory that occurs as part of normal brain function during sleep. The forgetting 165of dreams also provides valuable material for psychoanalysis, inviting interpretation, which we will explore later.[17]

For now, it is important to note that Wittgenstein considers dreams, as mental phenomena, to be memorable. This contrasts with Freud’s remarks on birth anxiety, which Wittgenstein suggests Freud “does not establish by reference to evidence—for he could not do so” (LA 1967: 43; my emphasis). Thus, dream interpretation, as an interpretive activity, differs from other aspects of Freud’s work, such as birth anxiety, which Wittgenstein implies is in principle untestable. With the possibility of reminiscence established, we can now turn to the issue of credibility.

Whenever someone successfully recalls (part of) a dream, they usually succumb to the temptation of interpreting it. For instance, one automatically makes associations with the things just dreamt, or they might recall some memories that they think are somehow relevant to the things they just saw. As most people have experienced at some point in their lives, we tend to include in our dreams people whom we know very well (such as family members, spouses, etc.), people with whom we have a limited relationship (such as coworkers, landlords, etc.) and also maybe complete strangers. In these instances, the subject is highly involved in the dream and, in a sense, forms part of their (dream) life.

In this complex situation, it seems natural to ask: Can we truly distinguish dream reports from the memories and associations they evoke, as Wittgenstein seems to imply? If we assume that dream reports reflect our value judgments—since the implicit decisions about which associations to make and which memories to recall already involve selection criteria—then we must also ask whether we can separate our background knowledge (facts about ourselves, our social circles, etc.) from our understanding of the dream itself. In other words, do we unconsciously (or unintentionally) alter our dream material—specifically, our dream reports—to make them more meaningful?

The underlying assumption of objective, unbiased dream recall suggests that we can provide a neutral, value-free account of our inner experiences. However, 166philosophy of science has shown that the value-free ideal is impossible; theory-ladenness is an inherent feature of all observation, whether of the external world or our inner experiences (which are also part of the natural world). Therefore, rather than treating dream reports as raw, unmediated observations akin to direct encounters with nature, we should aim to understand how our dream data are shaped by our dispositions and unique personal histories.

Without achieving a proper understanding of how we gather and interpret our dream evidence we cannot reliably test whether our hypothesis—that every dream represents wish-fulfillment—can be confirmed or refuted. Ultimately, a thorough exploration of these issues will reveal whether Wittgenstein’s earlier suggestion for a scientific treatment of dreams is truly feasible.

3.3 The Problem of Meaning in Dream Interpretation

Whenever we discuss evidence, it is necessary to contextualize data within the framework of our evolving theories. Since any discussion of evidence inherently involves a process of interpretation—one that makes the data understandable and situates it within these theoretical frameworks—this section will examine the problems of meaning that arise during this interpretative process.

Before addressing these issues, it is important to consider Wittgenstein’s position on the theory-ladenness of observation, even though he did not use this specific term. As we will explore later in this section, Freud’s interpretive method hinges on challenging the (psychical) reality of dream reports, prompting Freud to seek alternative methods of interpretation. Understanding Wittgenstein’s perspective on this matter is essential, as it may help us discern if his eventual rejection of Freud’s theory stems from deeper methodological and epistemological differences.

Although Wittgenstein never explicitly described observation as “theory-laden”, historical evidence suggests that his ideas influenced Norwood Hanson, who likely coined the term. Hanson himself openly acknowledged his intellectual debt to Wittgenstein.

It was his [Wittgenstein’s] analysis of complex concepts such as seeing, seeing as, and seeing that which exposed the crude, bipartite philosophy of sense datum versus interpretation as being the technical legislation it really is. By means of philosophy he destroyed the dogma of immaculate perception. (Hanson 1969: 74; cited in Kindi 2017: 595.)

With that in mind, can we suggest that Wittgenstein’s criticism of Freud’s methodology in The Interpretation of Dreams (as indicated by the passages we have exam167ined) stems from Freud’s distinction between manifest and latent dream content? I do not think so, and I will explain why. While Freud’s distinction implies a rejection of the “immaculate” perception of the manifest dream content—the dream as the subject experiences it—this does not seem to be Wittgenstein’s central concern. Freud does not question the perceptual reliability of the manifest content itself, just as Wittgenstein would not dispute the credibility of a subject who, when shown the duck-rabbit figure (cf. PPF 2009: 121), sees only the duck or the rabbit. The real issue here lies in interpretation. Psychoanalysis teaches us that the true meaning of a dream often resides outside its manifest content. Given that Wittgenstein acknowledges how our theoretical frameworks shape our understanding of things, I believe his ultimate rejection of Freud’s theories is not rooted in the latent-manifest distinction but likely elsewhere in Freud’s interpretative approach.

Another implication of Freud’s manifest-latent distinction is the plurality of meanings that dream content can express. In this context, the manifest dream content, as reported by the dreamer, is often associated with a false meaning, since it frequently fails to accurately represent the subject’s fulfilled wish. In contrast, the latent dream content, revealed through psychoanalysis, is linked to the correct or true meaning of the dream. What does Wittgenstein think of this conception? His answer is straightforward:

The majority of dreams Freud considers have to be regarded as camouflaged wish fulfillments; and in this case they simply don’t fulfill the wish. Ex-hypothesi the wish is not allowed to be fulfilled, and something else is hallucinated instead. If the wish is cheated in this way, then the dream can hardly be called a fulfillment of it. Also it becomes impossible to say whether it is the wish or the censor that is cheated. Apparently both are, and the result is that neither is satisfied. So that, the dream is not an hallucinated satisfaction of anything. (LA 1967: 47)

As is apparent in the above passage, Wittgenstein challenges the idea that a wish can be indirectly fulfilled. For Wittgenstein, a wish is either explicitly fulfilled in a dream, or it is not fulfilled at all. Consequently, Freud’s explanations amount to conceptual confusion, since the very concept of “fulfillment” entails that something must actually be fulfilled. If it is not, then there was no fulfillment in the first place.

However, both thinkers share the notion of a multiplicity of meaning within their theoretical frameworks. It is well known that Wittgenstein argues meaning is not static or an absolute property assigned to a thing or an activity; rather, meaning is something conveyed through the use of words within a language game. For instance, in his famous example from Philosophical Investigations, a builder utters the word “slab” to his assistant (PI 2009: 6). Depending on the context of the language game, the word “slab” could signify an object (PI 2009: 6), serve as a question 168(“Could you bring me a slab?”), or function as a command (“Bring me a slab!”) (PI 2009: 19). Despite the word “slab” remaining the same, its meaning changes with its use in different contexts, and Wittgenstein examines various language games to reveal these possibilities.

If we interpret Freud’s latent and manifest dream content as different language games, we could view the meaning of various elements of the dream as changing depending on the context—whether in the manifest or latent dream. This would align with Wittgenstein’s idea that the meaning of words or elements might shift with their use in different contexts. In this sense, the two thinkers are not so far apart regarding this particular point. As in other instances, Wittgenstein’s critique is not directed at Freud’s methodological distinctions, but rather at the explanations Freud offers.

One area where Wittgenstein has been notably critical of Freud’s explanations is in the realm of dream symbolism. Dream symbolism is a major topic Wittgenstein addresses during his conversations with Rhees, and his comments on the meaning of symbols are present throughout all four of Rhees’ recorded conversations. One of the most enlightening passages appears in the first conversation, and it is as follows:

Symbolizing in dreams. The idea of a dream language. Think of recognizing a painting as a dream. I (L.W.) was once looking at an exhibition of paintings by a young woman artist in Vienna. There was one painting of a bare room, like a cellar. Two men in top hats were sitting on chairs. Nothing else. And the title: “Besuch” (“Visit”). When I saw this I said at once “This is a dream”, (My sister described the picture to Freud, and he said ‘Oh yes, that is quite a common dream’—connected with virginity.) Note that the title is what clinches it as a dream—by which I do not mean that anything like this was dreamt by the painter while asleep. You would not say of every painting “This is a dream”. And this does show that there is something like a dream language. Freud mentions various symbols: top hats are regularly phallic symbols, wooden things like tables are women, etc. His historical explanation of these symbols is absurd. We might say it is not needed anyway: it is the most natural thing in the world that a table should be that sort of symbol. But dreaming—using this sort of language—though it may be used to refer to a woman or to a phallus, may also be used not to refer to that at all. (LA 1967: 43 – 44)

Assuming we are at an art exhibition, beholders aim to understand and ‘correctly’ interpret the pieces they observe. In this seemingly simple scenario, we see two men in top hats sitting in a bare room. Is this data alone sufficient to identify the picture as a dream? Wittgenstein’s categorical answer is no. What makes this artistic piece resemble a dream—and we use the term ‘resemble’ because we can never know the creator’s true intentions—is its context. The context is incomplete without considering its title, “Besuch” (Visit).169

Wittgenstein acknowledges the possibility of a latent—and potentially correct—meaning in dreams. The artwork in the exhibition demands a metaphorical interpretation, much like most dreams according to Freud. This idea connects to Wittgenstein’s distinction between “seeing” and “seeing as”. For Wittgenstein, “seeing as” involves not just perception but also interpretation (PI 2009: 137). Thus, not everyone perceives the picture as a dream; some may simply see two people in hats sitting in an empty room.

Regarding the idea of a dream language, Wittgenstein argues that such a language explains why not every painting is interpreted as a dream. Wittgenstein implicitly critiques Freud’s notion of wish-fulfillment, which Freud often links to the essence of dreams. As previously noted, neither wish-fulfillment nor paintings are necessarily associated with all dreams, highlighting the diversity of dream language. For example, a picture of two men sitting in a cellar might be interpreted differently if labeled “Father and Son”. The difference lies in how the artwork’s meaning is conveyed by its creator.

The same applies to symbols. Although top hats might frequently be linked to the “phallus” and Freud offers historical and other explanations for this, claiming these symbols represent universal characteristics of dreams is problematic. Wittgenstein criticizes Freud for persistently seeking a fundamental role for mental phenomena such as dreams, dream symbolism, and hallucinations. Using the methodology developed in his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein aims to show that Freud’s approach is misguided. Instead of trying to explain otherwise inexplicable phenomena (such as camouflaged wish-fulfillments), Freud should study the various ways dreams and their symbolisms unfold. The fact that objects like tables are not always used to refer to women illustrates the complexity of dream language, which cannot be reduced to a single meaning. Wittgenstein’s critique is encapsulated in the question: “Can we say we have laid bare the essential nature of mind? ‘Concept formation.’ Couldn’t the whole thing have been differently treated?” (LA 1967:45)[18]170

3.4 How Many Times Does a Dreamer Dream? Dream Interpretation as a Change of Aspect

We will finish this part by considering Wittgenstein’s thoughts on the process of dream interpretation. Wittgenstein here focuses on what happens to the subject when a dream is interpreted. From the subject’s perspective, how does a dream shift from being puzzling to making sense in their own understanding?

So far, we have explored several ways in which different elements of the dream can be interpreted. These include not only symbols—which make up only part of the dream report—but also other elements of the manifest content that require interpretation due to their distortion by the censor. The psychoanalyst, however, must interpret the dream as a whole, in a way that illuminates various aspects of the subject’s mental life.

To put it differently, how does the psychoanalyst combine the theoretical elements and techniques discussed above to form a comprehensive interpretation of the dream, the final step that will enable the analysand to uncover their suppressed wishes and desires? Wittgenstein comments:

When a dream is interpreted we might say that it is fitted into a context in which it ceases to be puzzling. In a sense the dreamer re-dreams, his dream [is placed] in surroundings such that its aspect changes. It is as though we were presented with a bit of canvas on which were painted a hand and a part of a face and certain other shapes, arranged in a puzzling and incongruous manner. Suppose this bit is surrounded by considerable stretches of blank canvas, and that we now paint in forms—say an arm, a trunk, etc.—leading up to and fitting on to the shapes on the original bit; and that the result is that we say: “Ah, now I see why it is like that, how it all comes to be arranged in that way, and what these various bits are . . .” and so on. (LA 1967: 45 – 46; my emphasis.)

If there is a change in the dream’s aspect, and it is placed in a different context from its original one, how can we still say that the dream remains the same? 171One might argue that the dream’s identity shifts, and what the dreamer is actually doing is a kind of re-dreaming—a repetition of the dream process, reshaped by the analyst’s guidance to make it meaningful. Moreover, even if we assume that the reconstruction of the dream report is itself a form of dreaming, whose dream is it that emerges? The analyst’s or the analysand’s? To address these questions, we must turn to Freud’s principles of dream interpretation.

As Jonathan Lear notes in his monograph on Freud (2015: 97−98), two key principles of dream interpretation are, first, that the context of the dreamer’s life must be taken into account, and, second, that the ultimate authority on the meaning of a dream is the dreamer. If we accept that Freud sincerely adhered to these principles (and there is no cogent historical evidence to suggest otherwise), then the final authority on the dream is the analysand—the one to whom the reconstructed dream truly belongs.

Since the context of the dream is altered, we cannot claim that the meaning of the reconstructed dream is identical to the dream the subject originally experienced. The dream and its meaning change as the context in which it is presented changes. With the two dreams placed in different contexts—where the function of various dream elements shifts—we can assume that the analysand ultimately interprets a grammatically different dream. The process of interpreting symbols and other dream aspects unfolds gradually: first, the analysand proposes an interpretation, then the analyst responds, and this exchange continues until the analysand reaches a final decision about the dream’s meaning.

This gradual process makes the interpretations inherently different, as the meaning (and, by extension, the use) of the dream’s elements changes with each interpretation. Wittgenstein states that “meaning mustn’t be capable of interpretation. It is the last interpretation” (BBB 1958: 34). Since interpretation has its limits, the dream itself must change to allow further interpretation. In this sense, when the dream is placed in a context that resolves its initial puzzling nature, the dream itself changes—the dreamer re-dreams.

Still, even if the subject experiences different aspects of a dream—resulting in a kind of re-dreaming—this process still belongs to the same dream. Wittgenstein notes:

What is done in interpreting dreams is not all of one sort. There is a work of interpretation which, so to speak, still belongs to the dream itself. In considering what a dream is, it is important to consider what happens to it, the way its aspect changes when it is brought into relation with other things, remembered, for instance. On first awaking a dream may impress one in various ways. One may be terrified and anxious; or when one has written the dream down one may have a certain sort of thrill, feel a very lively interest in it, feel intrigued by it. If one now remembers certain events in the previous day and connects what was dreamed with these, this already makes a difference, changes the aspect of the dream. If reflecting 172on the dream then leads one to remember certain things in early childhood, this will give it a different aspect still. And so on. (All this is connected with what was said about dreaming the dream over again. It still belongs to the dream, in a way.) (LA 1967: 46; my emphasis.)

I believe Wittgenstein accurately identifies many aspects of Freud’s approach to dream interpretation. Freud employs a multifaceted approach, both in explanation and interpretation, aiming to illuminate the issue from multiple angles. For instance, during analysis, the patient’s recollections may lead them to view the situation in a particular way. Similarly, focusing on the emotions that arise while recounting the dream highlights a different aspect of it. The same applies when the patient and analyst attempt to relate the dream to the analysand’s early childhood. Through this process, a panorama of perspectives emerges, and the patient gains a multifaceted understanding of the dream—with the analyst’s guidance.

Although the dream is re-enacted during this process, I question whether the outcome of this interpretative journey can still be considered part of the same dream, strictly speaking. In this regard, there seems to be an ambiguity between the two Wittgenstein passages cited earlier. The first suggests that the dream changes (“when the interpretation of the dream is fitted into a context that ceases to be puzzling, the dream changes. The dreamer re-dreams.”). However, in the second passage, Wittgenstein asserts that even though the subject is “dreaming the dream over again”, this experience “still belongs to the dream, in a way”.

I view these two alternatives as mutually exclusive—by definition, if the dream changes, it can no longer belong to the same dream. Given that I find Wittgenstein’s perspective on Freud’s dream interpretation consistent throughout his discussions with Rhees, we must determine which side of the argument better represents Wittgenstein’s thought.

Let us examine the canvas analogy Wittgenstein presented in the first of the two extracts. Initially, the canvas contains only “a hand, a part of a face, and certain other shapes, arranged in a puzzling and incongruous manner” (LA 1967: 45). With just this fragmentary information, the subject cannot derive any meaningful understanding from the canvas.

By analogy, when the dreamer first provides the dream report, they struggle to make sense of it, as the recalled information is incomplete and disjointed. The key factor that aids interpretation is the analytical work that follows, where techniques such as free association and the interpretation of symbols are applied. Similarly, Wittgenstein suggests that it is the painting of forms around the initial sketch on the blank canvas that leads the subject to grasp its meaning. The initially perplexing design requires new drawings that complete the context (the blank areas around the original sketch) and integrate the shapes into a coherent whole. Only 173then can the subject reflect “‘Ah, now I see why it is like that, how it all comes to be arranged in that way, and what these various bits are …’” (LA 1967: 46)[19]

In Wittgenstein’s analogy, it is the addition of new material that makes the picture comprehensible. Without these new forms, the image remains puzzling and obscure. However, once the new drawings are added the picture changes. Although the canvases before and after the new sketches may share certain elements, they still form different pictures. In a sense, the old canvas is related to the new one (much like the relationship between the dream before and after analysis), but the dream does not remain the same. It is transformed, and one could argue that the change is substantial.

Wittgenstein’s canvas analogy is used to illustrate the connection between the initial dream provided in the report and the reconstructed dream that emerges through interpretation. In this process, a form of re-dreaming occurs—the dream changes, but traces of the original dream persist in the new one.

4 Conclusion

In this paper, we have examined several aspects of Wittgenstein’s critique of Freud’s interpretation of dreams. A recurrent topic in his conversations with Rhees is Freud’s aim to reduce the array of differences experienced in the so-called “dream language” to some basic principles. For Freud, all dreams should serve the same purpose,[20] and all symbols of the same kind typically indicate the same (sexual) object. However, restricting the richness and diversity that characterize dreams, rather than serving the psychoanalyst in treating the subject, ultimately severely limits his therapeutic model. Rather than recognizing that the significa174tion of symbols is always context-bound and that the eventual fulfillment of a wish is a contingent fact dependent on the particularities of each dream, Freud insists on a reductionist model that ultimately inhibits—instead of enhancing—psychoanalytic work. As Wittgenstein noted, this is due to Freud’s essentialist metaphysical demands.

He wanted to find some one explanation which would show what dreaming is. He wanted to find the essence of dreaming. And he would have rejected any suggestion that he might be partly right but not altogether so. If he was partly wrong, that would have meant for him that he was wrong altogether—that he had not really found the essence of dreaming. (LA 1967: 48)

Wittgenstein’s admiration for Copernicus and Darwin was nuanced. He found these thinkers remarkable, not because they discovered flawless theories, but because they introduced “a fertile new point of view” (CV 1998: 26e). In my opinion, the same can be said of Wittgenstein’s assessment of Freud’s work on dreams.

Freud’s method of interpreting dreams offered a fruitful framework for understanding such phenomena, and Wittgenstein was particularly intrigued by Freud’s use of free association in the multifaceted examination of dream elements, connecting it to his own notion of change of aspect. However, Wittgenstein ultimately rejected Freud’s theory of dreams, citing shortcomings in both its methodological and explanatory approaches. From a scientific standpoint, Wittgenstein found Freud’s theory inadequate, advocating instead for a broadly construed hypothetico-deductive method.[21] Philosophically, he critiqued Freud’s work for remaining trapped within an essentialist metaphysical framework. Despite these criticisms, Freud’s work on dreams stimulated Wittgenstein’s interest more than most books did during his life, and this alone warrants further exploration of Wittgenstein’s relationship to Freud and psychoanalysis.175

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Vasso Kindi for our many discussions on Wittgenstein during the period I was writing this paper, as well as for her valuable suggestions in editing various drafts of it. I am also grateful to Ioannis Spiliopoulos for his careful reading and thoughtful reflections on earlier drafts, which helped me clarify and sharpen my views on both Wittgenstein and Freud. Lastly, I wish to thank Michael T. Michael for our correspondence on Freud and for his insightful comments on the first part of the paper.

Bibliography

Bouveresse, Jacques: Wittgenstein Reads Freud: The Myth of the Unconscious, Princeton, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

Cioffi, Frank: Making the Unconscious Conscious: Wittgenstein versus Freud, in: Philosophia 37 (2009), 565 – 588.10.1007/s11406-009-9201-9Search in Google Scholar

Freud, Sigmund: The Interpretation of Dreams (Part I), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. IV, edited by James Strachey, London 1953a.Search in Google Scholar

Freud, Sigmund: The Interpretation of Dreams (Part II), in: The Interpretation of Dreams (Part II) and On Dreams, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. V, edited by James Strachey, London 1953b, 339 – 630.Search in Google Scholar

Freud, Sigmund & Breuer Josef: Studies on Hysteria, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. II, edited by James Strachey, London 1955.Search in Google Scholar

Freud, Sigmund: Remarks on the Theory and Practice of Dream Interpretation, in: The Ego and the Id and Other Works, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. XIX, edited by James Strachey, London 1961a, 109 – 124.Search in Google Scholar

Freud, Sigmund: Moral Responsibility for the Content of Dreams, in: The Ego and the Id and Other Works, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. XIX, edited by James Strachey, London 1961b, 131 – 134.Search in Google Scholar

Freud, Sigmund: Project for a Scientific Psychology, in: Pre-Psycho-Analytic Publications and Unpublished Drafts, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. I, edited by James Strachey, London 1966, 283 – 346.Search in Google Scholar

Harcourt, Edward: Wittgenstein and Psychoanalysis, in: Hans-Johann Glock & John Hyman (eds.): A Companion to Wittgenstein, Chichester, West Sussex, UK 2017, 651 – 666.10.1002/9781118884607.ch43Search in Google Scholar

Hobson, Allan: Dreaming: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford 2005.10.1093/actrade/9780192802156.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Kindi, Vasso: Wittgenstein and Philosophy of Science, in: Hans-Johann Glock & John Hyman (eds.): A Companion to Wittgenstein, Chichester, West Sussex, UK 2017, 587 – 602.10.1002/9781118884607.ch38Search in Google Scholar

Kitcher, Patricia: Freud’s Dream, Cambridge, MA 1992.10.7551/mitpress/3112.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Lear, Jonathan: Freud, London 2015.10.4324/9781315771915Search in Google Scholar

McCarley, Robert W. & Hobson, J. Allan: The Neurobiological Origins of Psychoanalytic Dream Theory, in: The American Journal of Psychiatry 134/11 (1977), 1211 – 1221.10.1176/ajp.134.11.1211Search in Google Scholar

McGuinness, Brian: Wittgenstein: A Life: Young Ludwig 1889 – 1921, Berkeley/Los Angeles/London 1988.Search in Google Scholar

McGuinness, Brian: Freud and Wittgenstein, in: Approaches to Wittgenstein: Collected Papers, London 2002, 224 – 236.10.4324/9780203404928Search in Google Scholar

Michael, T. Michael: Freud’s Theory of Dreams: A Philosophico-Scientific Perspective, Lanham et al. 2015.10.5771/9781442230453Search in Google Scholar

Michael, T. Michael: Psychoanalytic proof: Revisiting Freud’s Tally Argument, in: The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 104/2 (2023), 331 – 355.10.1080/00207578.2022.2137675Search in Google Scholar

Monk, Ray: Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, London 1991.Search in Google Scholar

Müller, Johannes: Über die phantastischen Gesichtserscheinungen, Koblenz 1826.Search in Google Scholar

Pichler, Alois: Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Report of Two Dreams from October 1942, in: Nordic Wittgenstein Review 7/1 (2018), 101 – 107.10.15845/nwr.v7i1.3499Search in Google Scholar

Sand, Rosemarie: The Unconscious without Freud, Lanham et al. 2014.10.5771/9781442231740Search in Google Scholar

Sosa, Ernest: A Virtue Epistemology, New York 2007.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199297023.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Weininger, Otto: Sex and Character: An Investigation of Fundamental Principles, Bloomington, IN 2005.10.2979/2936.0Search in Google Scholar

Whyte, L. Lancelot: The Unconscious before Freud, New York 1960.Search in Google Scholar

Wittgenstein, Ludwig & Rhees, Rush: Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Conversations with Rush Rhees (1939 – 50): From the Notes of Rush Rhees, ed. by Gabriel Citron, in: Mind 124/493 (2015), 1 – 71.10.1093/mind/fzu200Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 The author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelei

- Inhalt

- Titlepages

- Titlepages

- Articles

- Hinweis für Leser / Note for Readers

- Tractarian Nonsense and Literary Language

- The Middle Wittgenstein on Aesthetics

- The Question of Linguistic Idealism in the Tractatus

- Waismann and Waismann’s Wittgenstein

- Die Grenzen welcher Sprache?

- Wittgenstein on Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams

- Wittgenstein über die Erkenntnis Anderer

- Shouldered In and Out of the Reality of Mortality

- On Deep Moral Disagreement Between Theists and Atheists

- Redrawing and publishing the graphics in Wittgenstein’s Nachlass

- Special Topic:Das erlösende Wort in dürftigen Zeiten – Wittgensteins Fortschritts-, Zivilisations- und Kulturkritik

- Einleitung

- Text und Kontext

- Wozu Philosophie und Kunst in Zeiten der Unkultur?

- „[I]ch sehe jedes Problem von einem religiösen Standpunkt.”

- Wittgensteins „erlösende Worte”

- Wittgenstein über die Bildung von Begriffen

- Buchbesprechungen / Book Reviews

- David R. Cerbone: Wittgenstein on Realism and Idealism

- Peter Eigner: Die Wittgensteins. Geschichte einer unglaublich reichen Familie

- Raimundo Henriques: Self-Understanding in the Tractatus and Wittgenstein’s Architecture: From Adolf Loos to the Resolute Reading

- Shunichi Takagi, Pascal F. Zambito (eds.): Wittgenstein and Nietzsche

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelei

- Inhalt

- Titlepages

- Titlepages

- Articles

- Hinweis für Leser / Note for Readers

- Tractarian Nonsense and Literary Language

- The Middle Wittgenstein on Aesthetics

- The Question of Linguistic Idealism in the Tractatus

- Waismann and Waismann’s Wittgenstein

- Die Grenzen welcher Sprache?

- Wittgenstein on Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams

- Wittgenstein über die Erkenntnis Anderer

- Shouldered In and Out of the Reality of Mortality

- On Deep Moral Disagreement Between Theists and Atheists

- Redrawing and publishing the graphics in Wittgenstein’s Nachlass

- Special Topic:Das erlösende Wort in dürftigen Zeiten – Wittgensteins Fortschritts-, Zivilisations- und Kulturkritik

- Einleitung

- Text und Kontext

- Wozu Philosophie und Kunst in Zeiten der Unkultur?

- „[I]ch sehe jedes Problem von einem religiösen Standpunkt.”

- Wittgensteins „erlösende Worte”

- Wittgenstein über die Bildung von Begriffen

- Buchbesprechungen / Book Reviews

- David R. Cerbone: Wittgenstein on Realism and Idealism

- Peter Eigner: Die Wittgensteins. Geschichte einer unglaublich reichen Familie

- Raimundo Henriques: Self-Understanding in the Tractatus and Wittgenstein’s Architecture: From Adolf Loos to the Resolute Reading

- Shunichi Takagi, Pascal F. Zambito (eds.): Wittgenstein and Nietzsche