Abstract

Objective

Since the soluble enzymes can not be used in repeated reactions and are not stable in operational conditions and not suitable for continuous processes, this study aimed the covalent immobilization of Bacillus licheniformis protease (BLP) onto Eupergit CM.

Methods

Optimum conditions for immobilization were determined by changing the conditions individually. The proteins and L-tyrosine were determined by UV/VIS spectrophotometer.

Results

The immobilization resulted in 100% immobilization and 107.7% activity yields. The optimum pH (7–8) and the optimum temperature (70°C) have not changed after immobilization. The Km values for free and immobilized enzyme were 26.53 and 37.59 g/L, while the Vmax values were 2.84 and 3.31 g L-Tyrosine/L·min, respectively. The immobilized enzyme has not lost its initial activity during the repeated 20 uses and 20 days of storage. The milk proteins were hydrolyzed in 2 h by using immobilized enzyme. The pH of the milk dropped from 6.89 to 6.53, the color was clearer but there was no change in the smell or the taste.

Conclusion

Consequently, it can be said that the immobilized BLP obtained can be used for industrial purposes.

Özet

Amaç

İmmobilize enzimler, tekrarlanan reaksiyonlarda kullanılamadığı ve kullanım şartlarında kararlı olmadığı ve endüstriyel sürekli süreçler için uygun olmadığından, bu çalışma, BLP’nin Eupergit CM’ye kovalent immobilizasyonunu amaçlamıştır.

Yöntemler

İmmobilizasyon için optimum koşullar, şartlar ayrı ayrı değiştirilerek belirlendi. Proteinler ve L-tirozin, UV/VIS spektrofotometre ile tayin edildi.

Bulgular

İmmobilizasyon % 100 immobilizasyon verimi ve % 107.7 aktivite verimi ile sonuçlandı. Optimum pH (7–8) ve optimum sıcaklık (70°C) immobilizasyon sonrasında değişmemiştir. Serbest ve immobilize enzim için Km değerleri sırasıyla 26.53 ve 37.59 g/L iken, Vmax değerleri sırasıyla 2.84 ve 3.31 g L-Tirozin/L·dk idi. İmmobilize enzim, tekrarlanan yirmi kullanım sırasında ve yirmi gün saklama süresinde başlangıç aktivitesini kaybetmedi. İmmobilize enzim kullanılarak süt proteinleri iki saat içinde tamamen hidrolize edildi. Sütün pH’sı 6.89’dan 6.53’e düşerken, renginde biraz açılma oldu fakat kokusunda ve tadında herhangi bir değişiklik olmadı.

Sonuç

Sonuç olarak, elde edilen immobilize BLP’nin endüstriyel amaçlar için kullanılabileceği söylenebilir.

Introduction

Cow’s milk protein (CMP) allergy is the immunological reactions that occur in the body against cow’s milk proteins [1]. CMP allergy is one of the most common allergies among infants and seen in 2–5% of all babies [2]. CMP in infant milk formula is used to ensure the protein content. However, non-breastfed babies are commonly fed with cow’s milk, especially in rural areas. Considering that more than 138 million babies came into the world each year [3], the CMP allergy which is seen as a world widespread disease can be greatly reduced by consumption of protein-free cow’s milk. Proteases are enzymes that convert the proteins to peptides and amino acids by hydrolysis. Therefore, they can be used in the production of cow’s milk that does not cause to protein allergy. There are a few studies in the literature related to the hydrolysis of whey proteins using soluble proteases [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Yet, there is no study in the literature related to the hydrolysis of proteins in the milk using immobilized proteases.

Bacillus licheniformis protease (BLP) (E.C.3.4.21.14) is a serine peptidase which forms peptides by hydrolyzing the proteins. It is used widely in a variety of applications including dietary supplements, food and beverage processes, ingredient development, and protein processing.

BLP has been immobilized by using different supports and methods in a few studies [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Nonetheless, there has been no study related to the immobilization of BLP on Eupergit CM.

Four different methods of immobilization have been developed according to the nature of the matrix used and the ones intended to be used: cross-linking, adsorption, entrapment, and covalent binding [19]. Hundreds of natural and synthetic supports or matrices have been used for immobilization of industrial enzymes [20]. Choosing the enzyme immobilization matrix and method is related to the nature of the matrix, the simplicity of the method, and the aimed use of the enzyme [21]. The covalent attachment is a more suitable method for all enzymes and for all applications since immobilized enzyme does not easily lose its activity [22].

Eupergit CM, which contains epoxy groups on its surface and consists of porous acrylic microbeads, is a commercial matrix developed for covalent immobilization of enzymes. Eupergit C is an excellent matrix for immobilization of enzymes. It is very stable in wide ranges of pH and at high temperatures, as well as suitable for all kinds of reactors. Epoxy groups on the matrix react with amino, sulfhydryl, and hydroxyl groups of biomolecules depending on pH of the buffer used [23]. Immobilization procedure is quite simple and involves the reaction of Eupergit C beads with aqueous enzyme solution at room temperature or 4°C for 24–20 h. Immobilization of enzymes onto epoxy activated matrix is affected by the amount of Eupergit C, pH and concentration of buffer used, and the duration of immobilization [24], [25]. These conditions must be optimized for using the immobilized enzymes in industrial applications. Since Eupergit CM has a similar chemical structure to that of Eupergit C, the same procedure is applied for immobilization. Many of the enzymes have been immobilized by using Eupergit C with up to 80% activity yields. Furthermore, in some studies immobilization have been resulted in an increased activity than soluble enzymes [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31].

In this study, BLP will tried to be immobilized by using the covalent binding method on Eupergit CM with the highest possible immobilization and activity yields.

Materials and methods

Materials

BLP (Alkaline protease L) which had 392.6 IU/mL protease activity, is a commerical enzyme preparation, was provided as a gift by Bio-Cat (Troy, MI, USA). Eupergit CM was a gift by Röhm and Haas (Darmstadt, Germany). UV-VIS Spectrometer (UV-6300PC) was purchased from VWR (Radnor, PA, USA). pH meter (Hanna HI 2020 edge), was purchased from Hanna Instruments Ltd. (Bedfordshire, UK). Magnetic stirrer (Heidolph MR Hei-Standard) was purchased from Heidolph UK-Radleys (Shire Hill, UK). Pure water appliance (Mini Pure 1, MDM-0170) was purchased from MDM Co. Ltd. (Suwon-si, South Korea). Sensitive scale (Shimadzu-ATX224) was purchased from Shimadzu Corporation (Kyoto, Japan). Orbital shaking heated incubator (Mipro-MCI) was purchased from Protek Lab Group professional laboratory solutions company (Ankara, Turkey). Vacuum pump (Biobase, GM-0.50A) was purchased from Biobase Biodustry Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China). Electrophoresis system (Mini-Protean Tetra Cell) was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). Bovine serum albumin, sodium hydroxide, sodium dihydrogen phosphate, hydrochloric acid, L-tyrosine and Folin & Ciocalteu’s Reagent were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). Sodium azide was purchased from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany). Semi-skimmed UHT cow milk was purchased from a local market.

Methods

All experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean values are calculated by using Windows Excell.

Immobilization procedure

Immobilization was performed by reacting 100 mg Eupergit CM with 200 μL free BLP having 78.51 IU activity in 5 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.5 M, pH 7.5) at 25°C for 24 h in an incubator with gentle shaked at 0.25155 g. After the immobilization, the beads were filtered and washed with 15 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.5) and 15 mL distilled water on a sintered glass filter by suction under vacuum. Then, immobilized enzymes have been stored in 5 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.5) in a refrigerator at +4°C until use.

Optimization of immobilization procedure

Optimum conditions for immobilization were determined by changing individually the conditions, (amount of Eupergit CM from 100 to 600 mg, pH from 5 to 10, buffer concentration from 0.5 to 2.0 M, and duration of immobilization from 12 to 120 h).

Protein assay

The amounts of proteins present in the immobilization buffer before and after the immobilization as well as amounts of proteins present in the semi-skimmed UHT cow’s milk before and after the hydrolysis of proteins were determined by using Bradford Protein Assay Method [32]. Accordingly, the 0.1 mL samples were added to 3000 mL Bradford reagents in 10 mL vials and incubated 45 min at room temperature for the completing the formations of color and after then the absorbances were measured at 595 nm by using UV spectrophotometer. The amount of immobilized enzyme protein was assayed from the difference between the amount of protein used for immobilization minus that recovered into the supernatant plus washings [33].

Determination of BLP activity

Casein solutions (1% w/v) prepared 5 mL 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) was reacted with 200 μL free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity at 70°C for 60 min in an incubator with gently shaking. Then, 400 μL of aliquots from the reaction mixture was added to 3600 μL of distilled water and boiled for 10 min to inactivate the enzyme. The amount of formed L-tyrosine was determined by measuring its absorbance using a UV spectrophotometer at 274 nm, according to the method of Esfandiary et al. [34]. One IU is defined as the amount of enzyme forming 1 μmol L-tyrosine from casein per minute, under optimum activity assay conditions.

Calculation of immobilization and activity yields

The immobilization and activity yields were calculated by using following equations.

Characterization of free and immobilized enzyme

Effect of pH on enzyme activity

The effect of pH on enzyme activity was investigated by performing the activity assay for the soluble and immobilized enzymes with 1% (w/v) casein solutions at 70°C and different pHs.

Effect of temperature on enzyme activity

The effect of temperature on enzyme activity was found by conducting the activity assay for the soluble and immobilized enzymes with 1% (w/v) casein solutions (pH 7.5) at different temperatures.

pH stability

Two hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity were incubated in sodium phosphate buffer solutions at various pH ranges (5.0–12.0) at room temperature for 1 h, then the remaining activity was determined under standard assay conditions.

Thermal stability

Two hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity were incubated in sodium phosphate buffer (25 mM, pH 7.5) at temperatures from 20 to 90°C for 1 h, then the remaining activity was determined using the standart assay method.

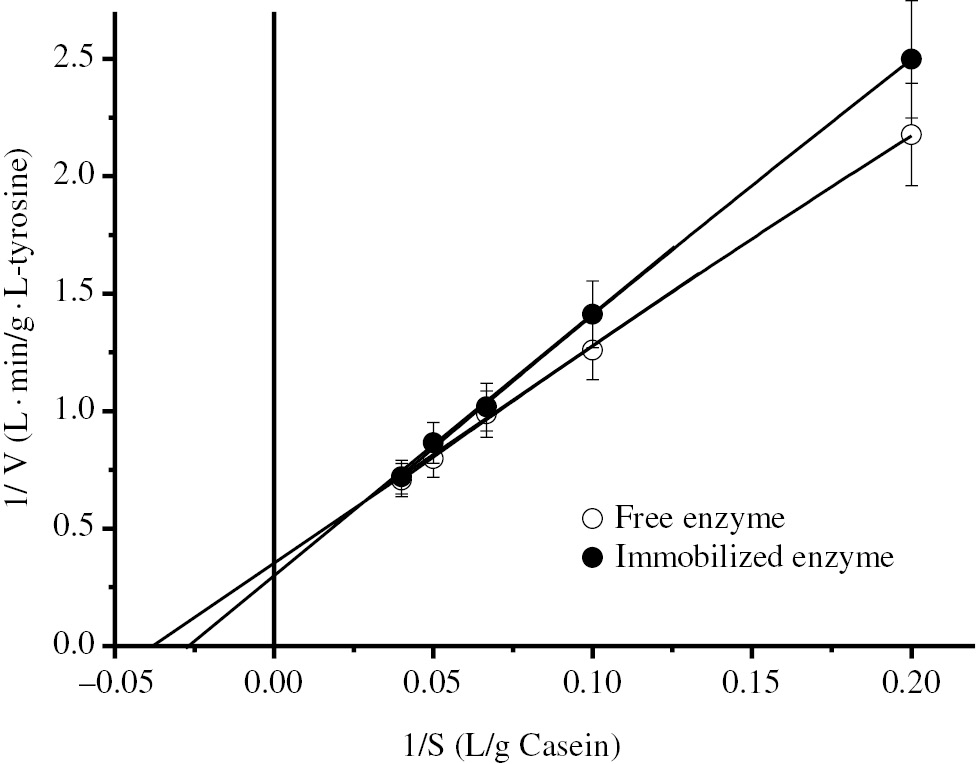

Kinetic constants

Initial velocities for kinetic parameters were determined by performing the reactions at different casein concentrations (5 to 25 g/L) for 15 min. Km and Vm were calculated from Lineweaver–Burk plots by non-linear curve fitting.

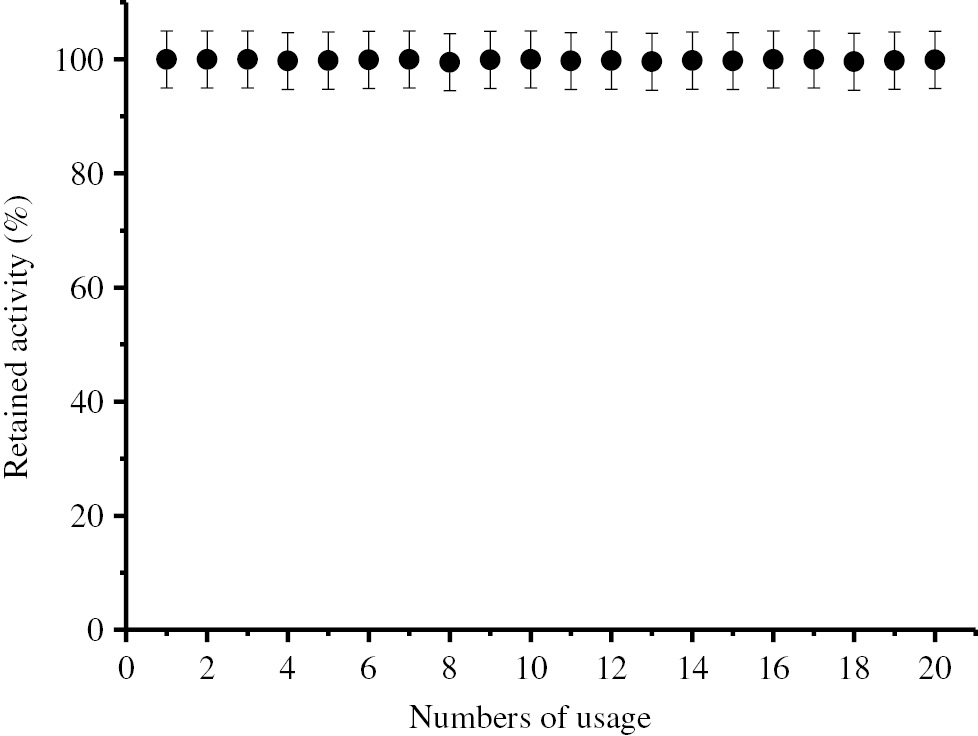

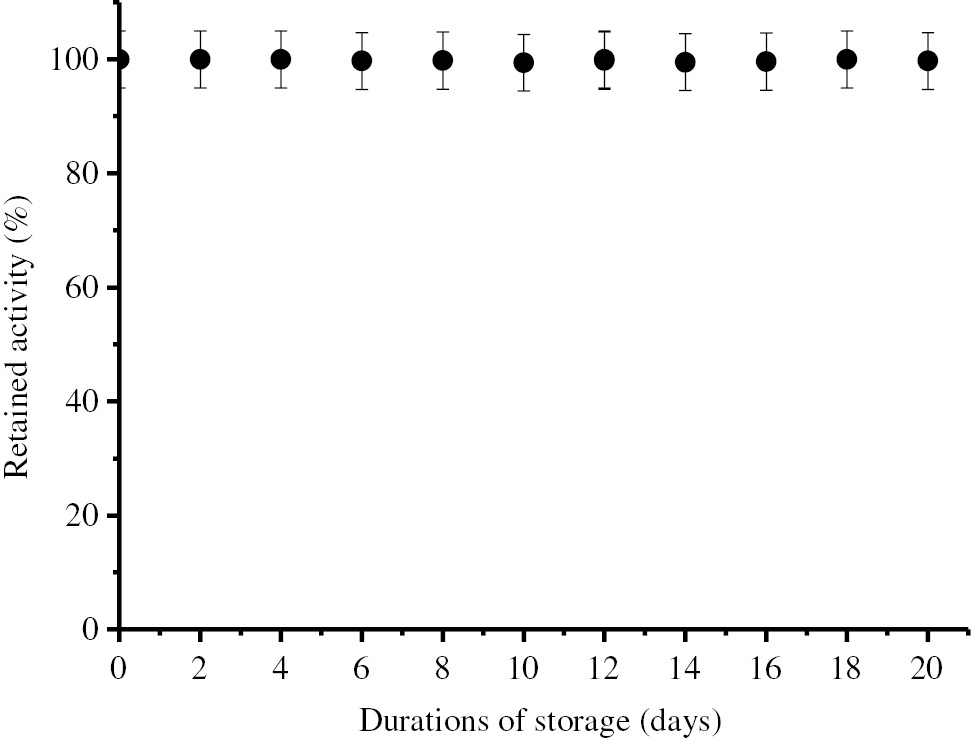

Operational and storage stabilities of the immobilized BLP

Operational and storage stabilities of the immobilized enzyme were determined by using the standard activity assay method in repeated batch experiments every 2 days, respectively. The immobilized enzymes used for the determination of storage stability were stored in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffers (pH 7.5) containing 0.02% sodium azide, in a refrigeratör at +4°C until next use. Before each use, the immobilized enzymes were filtered and washed with 15 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.5) and 15 mL distilled water on a sintered glass filter by suction under vacuum.

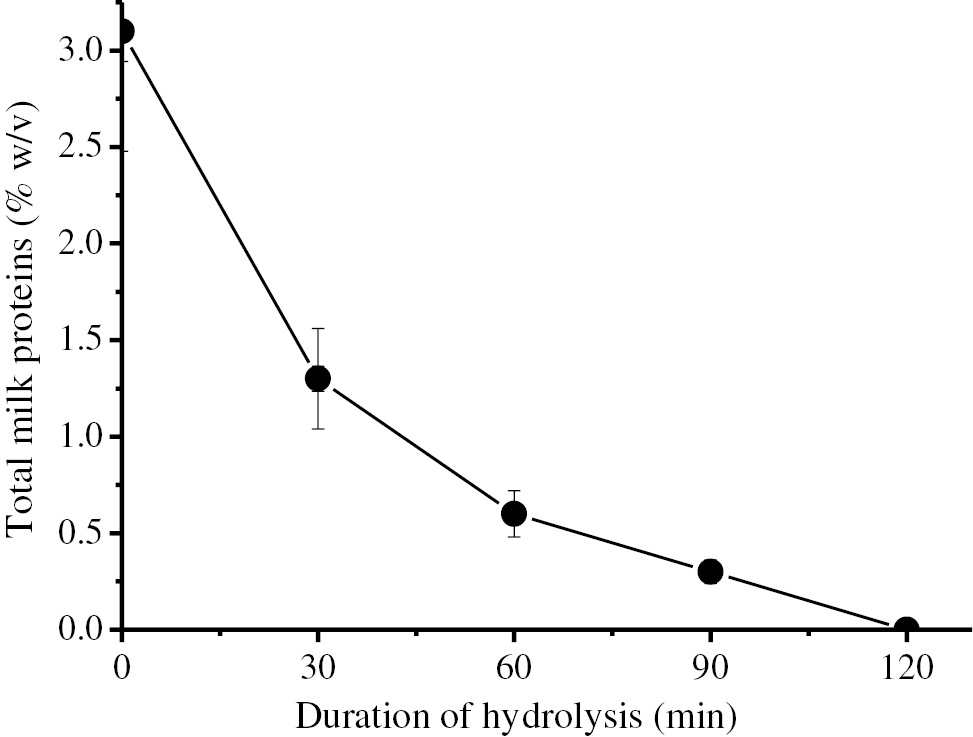

Hydrolysis of milk proteins by using immobilized BLP

0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity was reacted with 5 mL of semi-skimmed UHT cow’s milk at 70°C for 2 h and protein content was determined with 30 min intervals by using UV spectrophotometer.

Results

Protein assay

The enzyme concentration in the liquid BLP preparation was calculated as 27.04 mg/mL by using BSA standard curve equation. In addition, the amount of protein in the semi-skimmed UHT cow was calculated as 3.1%.

Determination of protease activity

Free BLP activity was calculated as 392.6 IU/mL by using Equation 3. Since 27.04 mg of the free protease was present in 1 mL of liquid BLP preparation, the specific activity of free BLP was also calculated to be 14.52 IU/mg. Lastly, the amount of free BLP having 1 IU activity was calculated as 0.069 mg.

Optimization of immobilization procedure

Effect of Eupergit CM amount on immobilization efficiency

Different amounts of support (100–600 mg) for BLP (200 μL) were tested. Table 1 shows that the lowest immobilization yield (71.0%) and highest activity yield (98.2%) were obtained for 100 mg Eupergit CM for 16 h immobilization.

Effect of Eupergit CM amount on immobilization efficiency.a

| Eupergit CM (mg) | Immobilization yieldb (%) | Activity yieldc (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 71.00±0.03 | 98.20±0.04 |

| 200 | 78.40±0.04 | 96.90±0.03 |

| 300 | 84.60±0.02 | 96.10±0.04 |

| 400 | 95.10±0.05 | 95.60±0.02 |

aEach value represents the mean for three independent experiments conducted in triplicates. Data was analyzed by using Microsoft Windows Excell.

bTwo hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity was reacted with different amounts of support in 5 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.5 M, pH 755) and room temperature with shaking at 0.25155 g in an incubator for 16 h.

cTwo hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity were reacted with 5 mL of 1% (w/v) casein solutions (pH 7.5) at 0.25155 g and at 70°C in an incubator for 60 min.

Effect of immobilization buffer pH on immobilization efficiency

Table 2 shows the influence of pH on immobilization. The highest immobilization efficiency was obtained at optimum pH (7.5) for both soluble and immobilized enzymes.

Effect of immobilization buffer pH on immobilization efficiency.a

| Immobilization buffer pH | Immobilization yieldb (%) | Activity yieldc (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 5.0 | 68.60±0.02 | 95.30±0.03 |

| 6.0 | 69.40±0.04 | 96.60±0.05 |

| 7.0 | 70.60±0.02 | 97.30±0.04 |

| 7.5 | 71.00±0.05 | 98.20±0.02 |

| 8.0 | 72.50±0.04 | 97.10±0.03 |

| 9.0 | 73.90±0.03 | 94.50±0.02 |

| 10.0 | 76.90±0.02 | 91.80±0.04 |

aEach value represents the mean for three independent experiments conducted in triplicates. Data was analyzed by using Microsoft Windows Excell.

bTwo hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity was reacted with 100 mg of supports in 5 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.5 M) at different pHs and room temperature with shaking at 0.25155 g in an incubator for 16 h.

cTwo hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity were reacted with 5 mL of 1% (w/v) casein solutions (pH 7.5) at 0.25155 g and at 70°C in an incubator for 60 min.

Effect of immobilization buffer molarity on immobilization efficiency

Table 3 shows the maximum immobilization efficiency obtained with phosphate buffers of 0.5 M.

Effect of immobilization buffer molarity on immobilization efficiency.a

| Buffer molarity (M) | Immobilization yieldb (%) | Activity yieldc (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 71.00±0.02 | 98.20±0.03 |

| 1.0 | 68.50±0.04 | 96.00±0.05 |

| 1.5 | 66.60±0.03 | 95.40±0.04 |

| 2.0 | 64.40±0.05 | 94.60±0.02 |

aEach value represents the mean for three independent experiments conducted in triplicates. Data was analyzed by using Microsoft Windows Excell.

bTwo hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity was reacted with 100 mg of supports in 5 mL of different concentrated sodium phosphate buffers (pH 7.5) at room temperature by shaking in an incubator at 0.25155 g for 16 h.

cTwo hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity were reacted with 5 mL of 1% (w/v) casein solutions (pH 7.5) at 0.25155 g and at 70°C in an incubator for 60 min.

Effect of immobilization time on immobilization efficiency

The duration of immobilization is of importance: maximum activity yield (107.7%) were achieved for 24 h (Table 4).

Effect of immobilization duration on immobilization efficiency.a

| Immobilization duration (h) | Immobilization yieldb (%) | Activity yieldc (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 00.00±0.02 | 00.00±0.04 |

| 16 | 71.00±0.04 | 98.20±0.03 |

| 24 | 100.00±0.03 | 107.70±0.05 |

| 48 | 100.00±0.05 | 102.10±0.02 |

| 72 | 100.00±0.03 | 97.30±0.04 |

| 96 | 100.00±0.04 | 94.40±0.03 |

| 120 | 100.00±0.02 | 92.70±0.05 |

aEach value represents the mean for three independent experiments conducted in triplicates. Data was analyzed by using Microsoft Windows Excell.

bTwo hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity was reacted with 100 mg of supports in 5 mL of sodium phosphate buffers (0.5 M, pH 7.5) at room temperature with shaking in an incubator at 0.25155 g for different durations.

cTwo hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity were reacted with 5 mL of 1% (w/v) casein solutions (pH 7.5) at 0.25155 g and at 70°C in an incubator for 60 min.

Characterization of immobilized enzyme

Optimum pH

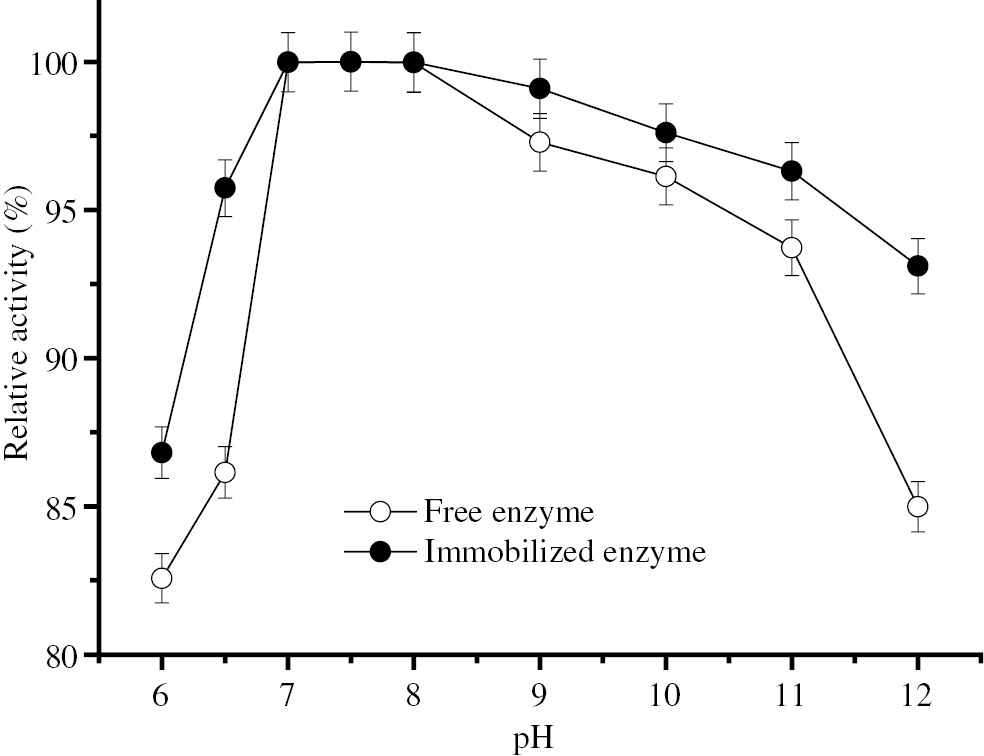

According to Figure 1, the optimum pH range of BLP (7.0–8.0) was not affected by immobilization. On the other hand, the immobilized enzyme is more active than the free enzyme in the pH ranges that is tested.

Optimum pH of free and immobilized BLP.

The effect of pH on enzyme activity was investigated by performing the activity assay for the soluble and immobilized enzymes with 1% (w/v) casein solutions, at different pHs, at 70°C. Hunderd percent relative activities represent 78.51 IU and 84.06 IU BLP activities for free and immobilized enzymes, respectively.

Optimum temperature

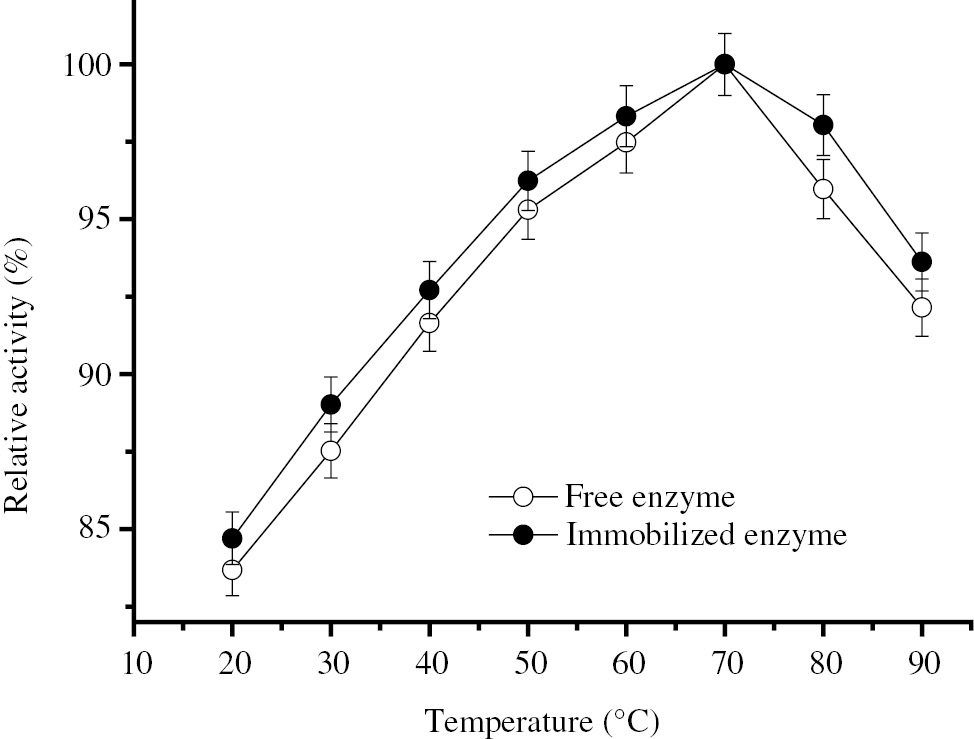

Figure 2 shows that the optimum temperature (70°C) was not affected by the immobilization. It is also clear that the immobilized enzyme exhibits higher activity than the free enzyme at the entire tested temperature range.

Optimum temperature of free and immobilized BLP.

The effect of temperature on enzyme activity was found by conducting the activity assay for the soluble and immobilized enzymes with 1% (w/v) casein solutions (pH 7.5) at different temperatures. 100% relative activities represent 78.51 IU and 84.06 IU BLP activities for free and immobilized enzymes, respectively.

pH stability

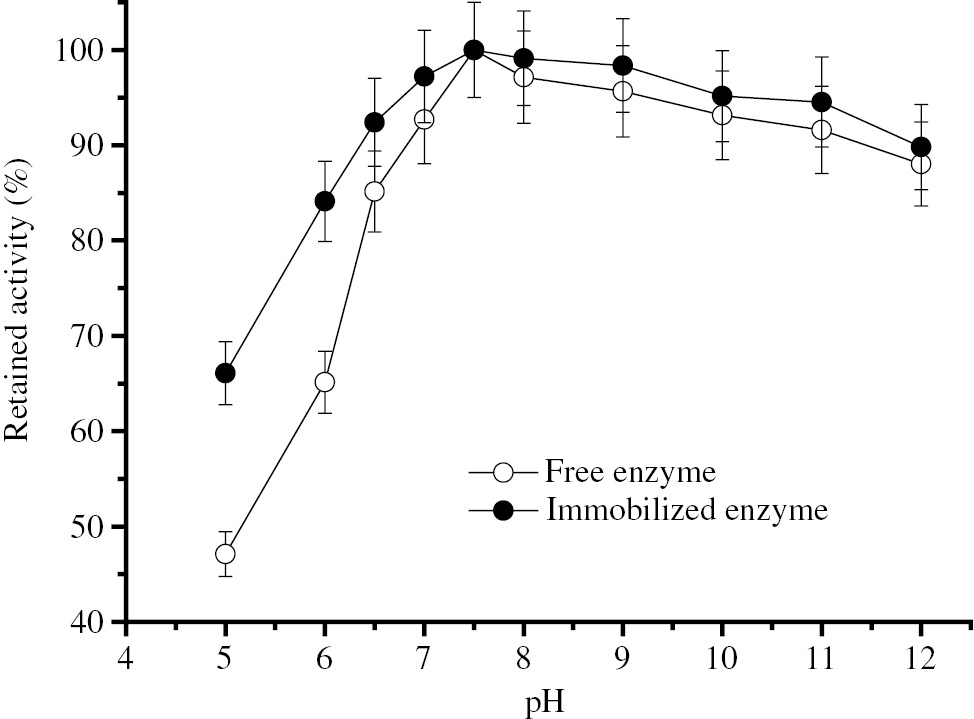

In Figure 3, the immobilized enzyme appears to be more stable than the free enzyme at entire tested pH range.

pH stability of free and immobilized BLP.

Two hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity were incubated in buffer solutions at various pHs (5.0–12.0) of at room temperature for 1 h and the remaining activity was determined under standart assay conditions.

Thermal stability

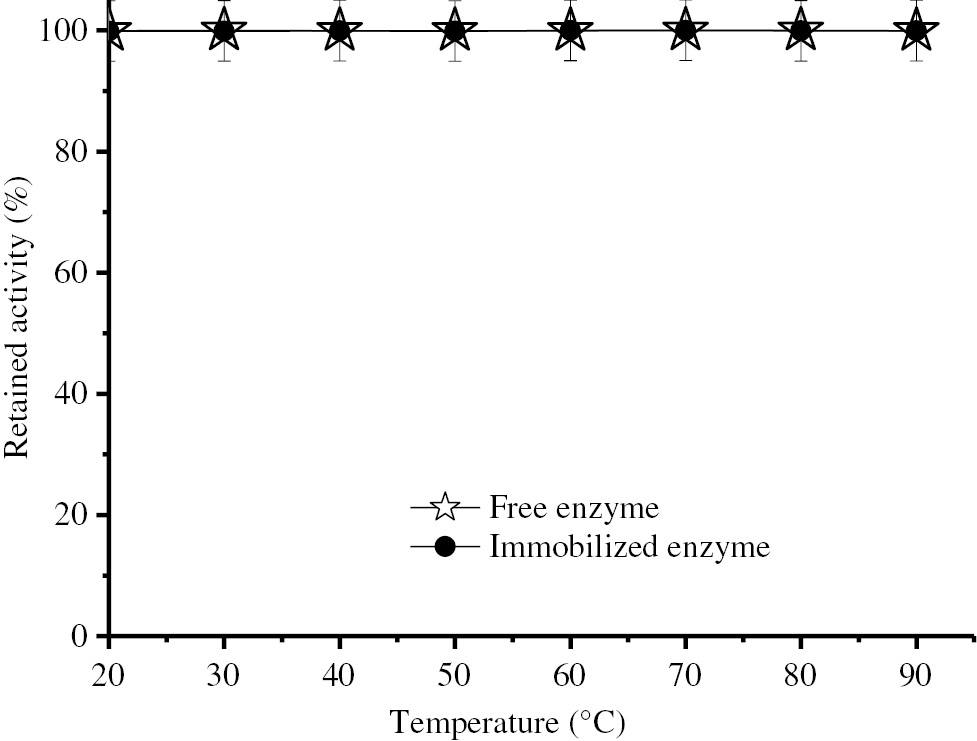

Figure 4 shows the effect of temperature on the stability of the free and immobilized enzymes. It is evident that at the entire tested temperatures of free and immobilized enzymes, their stability is greatly preserved.

Thermal stability of free and immobilized BLP.

Two hundred micro liter free BLP having 78.51 IU activity or 0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 84.06 IU BLP activity were incubated in buffer solutions (25 mM, pH 7.5) at temperatures from 20 to 90°C for 1 h and then the remaining activity was determined using the standard assay method.

Kinetic constants

The Michaelis-Menten (Km) and maximum velocity (Vmax) constants of the free and immobilized enzymes were calculated from the Lineweaver-Burk Graph by non-linear curve fitting (Figure 5). Immobilization increased the value of the Km constant from 26.53 g/L to 37.59 g/L while increased the Vmax from 2.84 g L-Tyosine/L·min to 3.31 g L-Tyosine/L·min.

Lineweaver–Burk plots of free and immobilized BLP.

Initial velocities for kinetic parameters were determined by performing the reactions at different casein concentrations (5–25 g/L) for 15 min.

Operational and storage stabilities of the immobilized BLP

As seen in Figure 6, the immobilized enzyme has not lost its activity during the repeated 20 uses under optimum conditions. According to Figure 7, the immobilized enzyme has not lost its activity for 20 days under optimum storage conditions eihter.

Operational stability of immobilized BLP.

Operational stability of the immobilized enzyme was determined by using the standard activity assay method, in repeated batch experiments.

Operational stability of immobilized BLP.

Storage stability of the immobilized enzyme was determined by using the standard activity assay method every 2 days.

Hydrolysis of milk proteins by using immobilized BLP

Changes in the protein concentration of the semi-skimmed UHT cow’s milk during hydrolysis was evaluated by using a graph showing protein concenrtration against the time course (Figure 8). As seen in that figure, all proteins available in the semi-skimmed milk have been completely hydrolzed in 2 h. This result is the highest degree of hydrolysis obtained compared to the previous findings in the relevant literature. Additionally, the pH of milk has decreased from 6.89 to 6.53 after hydrolysis. It was also observed that the milk was slightly transparent after hydrolysis. On the other hand, no change in the taste and smell of the milk has been detected at the end of the hydrolysis.

Hydrolysis of semi-skimmed UHT cow’s milk proteins by using immobilized BLP.

0.286 g Eupergit CM carrying 83.3 IU BLP activity was reacted with 5 mL of semi-skimmed UHT cow milk at 70°C for 2 h and protein content was determined with 30 min intervals by using UV spectrophotometer.

Discussions

The highest immobilization efficiency achieved for 100 mg of Eupergit CM can be seen from Table 1. Usage of higher amounts of Eupergit CM has resulted in the low activity yield. This is possibly due to the result of the deterioration of the three-dimensional structure of enzyme molecules upon multipoint attachment of enzyme molecules to the support. Moreover, the reaction of epoxy groups on support with amino acid residues associated with the active site of enzyme molecules can lead to decrease of the activity. As seen in Table 2, the highest activity yield in the immobilization with Eupergit CM has been obtained at the optimum pH (7.5) of the enzyme. The epoxy groups on Eupergit C can react with various reactive groups of enzymes in a wide pH range (0–12). Nevertheless, the highest activity yield is usually achieved at the optimum pH range in the immobilization of enzymes with Eupergit C [35]. Eupergit CM has a similar chemical structure to that of Eupergit C, but only beads and pore diameters, and the number of epoxy groups they contain differs. According to Table 3, when the molarity of immobilization buffer increased, activity yield has decreased while the immobilization yield has increased. Binding and activity yields in covalent enzyme immobilization on synthetic carriers, such as epoxy carriers, were often affected by the properties of the salts and their concentrations [36]. High salt concentration often increases the efficiency of binding due to the exposure of buried amino acid residues [37]. As it can be seen in Table 4, activity yield has decreased by increasing the duration of immobilization. This probably is due to changing the three dimensional structure of the enzyme, upon multipoint attachment of the enzyme to the support. By optimizing the immobilization conditions, 100% of immobilization yield and 107.7% of activity yield were achieved. Similar results are frequently encountered in the literature as well [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31].

Optimum pH range of BLP has not changed after the immobilization (Figure 1). This result partially overlaps with the findings of some studies in the related literature on the immobilization of BLP [13] that reported the optimal pH of the BLP (Subtilisin Carlsberg) immobilized on glutaraldehyde-activated silica was 8.0, which was silanized with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane. The optimal pH for the immobilization of Bacillus licheniformis CMIT 1.33 protease using silica gels, ceramic matrix, and entrapment method decreased to 8.0 from 9.0 [16]. In the adsorption of protease from Bacillus licheniformis B 40 on granular ceramics, the optimum pH of the enzyme (7.0) did not change [17]. On the other hand, both free and immobilized enzymes are more active at the alkaline pHs than at the acidic pHs. The activity of an enzyme is highly related to the chemical structure of amino acid available in the active site. The Ɛ-amino group of histidine and the carboxyl group of aspartic acid present in the active site of the Bacillus licheniformis alkaline protease is more protonated in the acidic pH range than in the alkaline pH ranges; therefore activity may be lower at the acidic pHs. We see in Figure 2 that the optimum temperature of BLP also has not changed after the immobilization, and the immobilized enzyme exhibit more activity than the free enzyme at the entire tested temperatures. Generally, at high temperatures, immobilized enzymes exhibit higher activity than the free enzymes thanks to immobilization increasing the thermal stability of the enzyme. According to Figure 3, it is also seen that the immobilized enzyme is more stable than the free enzyme at all tested pH values. Probably this is a result of strengthening the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme, after binding of the enzyme molecules to the matrix via covalent bonds that is the strongest bond. In Figure 4 is seen that both of free and immobilized BLP are stable also at high temperatures. It is generally known that immobilization improves the thermal stability of enzymes. In addition, the thermophilic character of BLP may also have been contributed to this as well.

According to Figure 5, immobilized BLP has a higher Km (37.59 g/L·min) and a higher Vmax (3.31 g L-Tyrosine/L·min) values, respectively than the free enzyme. Comparison of kinetic constants for free and immobilized enzymes supplies the information about effectiveness and performance of immobilized enzymes. Similar results are also seen in the literature. For example, the immobilization of alcalase alkaline protease from Bacillus licheniformis on the magnetic chitosan nanoparticles resulted in similar pattern of Lineweaver-Burk Plot to our results. Km values for free and immobiliized enzyme were 10.6 and 12.8 mg/mL while Vmax were 3.86 and 4.02 U/mg, respectively [31]. In another study, the immobilization of alkaline protease Esperase on Eudragit S-100 by covalent binding method incread the Km value of the enzyme from 4.2 mg/mL to 5.2 mg/mL [14]. In the stabilization of Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 21415 alkaline protease by immobilization and modification, the Km value had increased from 4.8 mg/mL to 5.0 mg/mL and 5.3 mg/mL, respectively, after immobilizaton and modification [15]. The increased Km value implies the immobilized enzyme has lower affinity to the substrate than soluble enzyme. This result probably caused from steric hindrance of the active site by the support, or the loss of enzyme flexibility necessary for substrate binding [14], [15]. On the other hand, the increased Vmax value may be due to hydrophobic character of matrix which supplies the optimum microenvironment for active sites of the enzymes [28]. There are also some similar studies that reported the increased Vmax values after immobilization in the literature [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31].

It is seen in Figures 6 and 7 that the immobilized BLP has not lost its activity during 20 repeated usage and 20 days of storage. According to these results, it can be said that the immobilized BLP has a high usage and storage stability.

As seen in Figure 8, immobilized BLP has been successfully used in the hydrolyzing of all proteins available in the semi-skimmed UHT cow’s milk without causing any important changes in its properties.

Consequently, it can be said that immobilized BLP obtained in the present study can be used in the industrial production of cow’s milk without milk protein allergy causing effects.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge to Röhm and Haas and Bio-Cat Companies for their kindly gifts Eupergit CM and Alkaline Protease L, respectively. The authors also acknowledge to the Siirt University Scientific Research Projects Coordinatorship for their financial support (Grant no. 2016-SÏÜFEB-03).

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest in this work.

References

1. Koca T, Akçam M. İnek sütü protein alerjisi. Dicle Med J 2015;42:268–73.10.5798/diclemedj.0921.2015.02.0572Suche in Google Scholar

2. Anonim, http://www.bebekvealerji.com/inek-sutu-alerjisi-olabilir-mi/inek-sutu-alerjisi-nedir/, “Çocuk Alerji ve Astım Akad. Dern.” 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Anonim, The state of the world’s children 2014 in numbers. http://www.unicef.org/sowc2014/numbers, “United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)” 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Kaminogawa S, Yamauchi K. Decomposition of β-Casein by milk protease similarity of the decomposed products to temperature-sensitive and R-Caseins. Agric Biol Chem 1972;36:255–60.10.1080/00021369.1972.10860238Suche in Google Scholar

5. Kaminogawa S, Yamauchi K, Mıyazawa S, Koga Y. Degradation of casein components by acid protease of bovine milk. J Dairy Sci 1980;63:701–4.10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(80)82996-1Suche in Google Scholar

6. Tavaria FK, Sousa MJ, Domingos A, Malcata FX, Brodelius P, Clemente A, et al. Degradation of caseins from milk of different species by extracts of Centaurea calcitrapa. J Agric Food Chem 1997;45:3760–5.10.1021/jf970095xSuche in Google Scholar

7. Trujillo AJ, Guamis B, Carretero C. Hydrolysis of bovine and caprine caseins by rennet and plasmin in model systems. J Am Chem Soc 1998;46:3066–72.10.1021/jf9802272Suche in Google Scholar

8. Eigel WN, Hofmann CJ, Chibbert BA, Tomicht JM, Keenan TW, ve Mertzt ET. Plasmin-mediated proteolysis of casein in bovine milk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1979;76:2244–8.10.1073/pnas.76.5.2244Suche in Google Scholar

9. Coşkun H, Sienkiewicz T. Degradation of milk proteins by extracellular proteinase from Brevibacterium linens flk-61. Food Biotechnol 2009;13:67–275.10.1080/08905439909549977Suche in Google Scholar

10. Elfahri K. “Release of bioactive peptides from milk proteins by Lactobacillus species”, A thesis submitted in completion of requirements of the degree of Master of Science, School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Faculty of Health, Engineering and Science Victoria University Melbourne, Victoria, 2012;29–69.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Behbahani P, Jayashankara M, Bhat GS. Influence of caseinophosphopeptides on performance of lactic cultures in fermented milk. Sci J Microb 2013;2013:1–7.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Szélpál S, Fejes K, Csanádi J, Šoronja-Simovıć D, László S, Keszthelyıszabó G, et al. Enrichment of bioactive material by enzymatic degradation and membrane separation. Ann Fac Eng Hun-Int J Eng 2013;4:1–6.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Ferreira L, Ramos MA, Dordick JS, Gil MH. Influence of different silica derivatives in the immobilization and stabilization of a Bacillus licheniformis protease (Subtilisin Carlsberg). J Mol Cat B 2003;21:189–99.10.1016/S1381-1177(02)00223-0Suche in Google Scholar

14. Silva CJ, Zhang Q, Shen J, Cavaco-Paulo A. Immobilization of proteases with a water soluble–insoluble reversible polymer for treatment of wool. Enzyme Microb Technol 2006;39:634–40.10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.11.016Suche in Google Scholar

15. Ahmed SA, Saleh SA, Abdel-Fattah AF. Stabilization of Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 21415 alkaline protease by immobilization and modification. Aust J Basic Appl Sci 2007;1:313–22.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Dragomirescu M, Vintilǎ T, Vlad-Oros B, Preda G. Stabilization of microbial enzymatic preparations used in feed industry. Sci Pap Anim Sci Biotechnol 2008;41:69–72.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Dragomirescu M, Preda G, Vintilǎ T, Vlad-Oros B, Bordean D, Savii C. The effect of immobilization on activity and stability of a protease preparation obtained by an indigenous strain Bacillus licheniformis B 40. Rev Roum Chim 2012;57:77–84.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Nazari T, Alijanianzadeh M, Molaeirad A, Khayati M. Immobilization of Subtilisin Carlsberg on modified silica gel by cross-linking and covalent binding methods. Biomacromol J 2016; 2:53–8.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Nisha S, Arun Karthick S, Gobi N. A review on methods, application and properties of immobilized enzyme. Chem Sci Rev Lett 2012;1:148–55.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Datta S, Christena LR, Rajaram YR. Enzyme immobilization: an overview on techniques and support materials. 3 Biotech 2013;3:1–9.10.1007/s13205-012-0071-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Hanefeld U, Gardossi L, Magner E. Understanding enzyme immobilisation. Chem Soc Rev 2009;38:453–68.10.1039/B711564BSuche in Google Scholar

22. Zucca P, Sanjust E. Inorganic materials as supports for covalent enzyme immobilization: methods and mechanisms. Molecules 2014;19:14139–94.10.3390/molecules190914139Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Boller T, Meier C, Menzler S. Eupergit oxirane acrylic beads: how to make enzymes fit for biocatalysis. Org Process Res Develop 2002;6:509–19.10.1021/op015506wSuche in Google Scholar

24. Hernaiz MJ, Crout DH. Immobilization/stabilization on Eupergit C of the β-galactosidase from B. circulans and an β-galactosidase from Aspergillus oryzae. Enzyme Microb Technol 2000;27: 26–32.10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00150-2Suche in Google Scholar

25. Martin MT, Plou FJ, Alcalde M, Ballesteros A. Immobilization on Eupergit C of cyclodextrin glucosyltransferase (CGTase) and properties of the immobilized biocatalyst. J Mol Cat B 2003;21:299–308.10.1016/S1381-1177(02)00264-3Suche in Google Scholar

26. Torres-Bacete J, Arroyo M, Torres-Guzman R, De la Mata I, Castillon PM, Acebal C. Covalent immobilization of penicillin V acylase from Streptomyces lavendulea. Biotechnol Let 2000;22:1011–4.10.1023/A:1005601607277Suche in Google Scholar

27. Aslan Y, Tanrıseven A. Immobilization of Pectinex Ultra SP-L to produce galactooligosaccharides. J Mol Cat B 2007;45:73–7.10.1016/j.molcatb.2006.12.005Suche in Google Scholar

28. Zarcula C, Croitoru R, Corîci L, Csunderlik C, Peter F. Improvement of lipase catalytic properties by immobilization in hybrid matrices. Int J Chem Biol Eng 2009;2:139–43.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Aslan Y, Handayani N, Stavila E, Loos K. Improved performance of Pseudomonas fluorescens lipase by covalent immobilization onto Amberzyme. Turk J Biochem 2013;38:313–8.10.5505/tjb.2013.30085Suche in Google Scholar

30. Aslan Y, Handayani N, Stavila E, Loos K. Covalent immobilization of Pseudomonas fluorescens lipase onto Eupergit CM. Int J Curr Res 2014;6:5225–8.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Wang S, Chaoran Zhang C, Qi B, Sui X, Jiang L, Li Y, et al. Immobilized alcalase alkaline protease on the magnetic chitosan nanoparticles used for soy protein isolate hydrolysis. Eur Food Res Technol 2014;239:1051–9.10.1007/s00217-014-2301-1Suche in Google Scholar

32. Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976;72:248–54.10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3Suche in Google Scholar

33. Manjon A, Iborra JL, Ozano PL, Canovas M. A practical experiment on enzyme immobilization and characterization of the immobilized derivatives. Biochem Educ 1995;23;213–6.10.1016/0307-4412(95)00066-CSuche in Google Scholar

34. Esfandiary R, Hunjan JS, Lushington GH, Joshi SB, Middaugh CR. Temperature dependent 2nd derivative absorbance spectroscopy of aromatic amino acids as a probe of protein dynamics. Protein Sci 2009;18:2603–14.10.1002/pro.264Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Katchalski-Katzir E, Kraemer DM. Eupergit C, a carrier for immobilization of enzymes of industrial potential. J Mol Cat B 2000;10:157–76.10.1016/S1381-1177(00)00124-7Suche in Google Scholar

36. Smalla K, Turkova J, Coupek J, Hermann P. Influence of salts on the covalent immobilisation of proteins to modified copolymers of 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate with ethylene dimethacrylate. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 1988;10:21–31.10.1111/j.1470-8744.1988.tb00003.xSuche in Google Scholar

37. Cao L. Carrier-bound immobilized enzymes. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2005:160.Suche in Google Scholar

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Effects of calcium hydroxide and N-acetylcysteine on MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 in LPS-stimulated macrophage cell lines

- Synthesis of fused 1,4-dihydropyridines as potential calcium channel blockers

- Optimization of fermentation conditions for efficient ethanol production by Mucor hiemalis

- Covalent immobilization of an alkaline protease from Bacillus licheniformis

- Major biological activities and protein profiles of skin secretions of Lissotriton vulgaris and Triturus ivanbureschi

- Optimized production, purification and molecular characterization of fungal laccase through Alternaria alternata

- Adsorption of methyl violet from aqueous solution using brown algae Padina sanctae-crucis

- Protective effect of dexpanthenol (vitamin B5) in a rat model of LPS-induced endotoxic shock

- Purification and biochemical characterization of a β-cyanoalanine synthase expressed in germinating seeds of Sorghum bicolor (L.) moench

- Molecular cloning and in silico characterization of two alpha-like neurotoxins and one metalloproteinase from the maxilllipeds of the centipede Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans

- Improvement of delta-endotoxin production from local Bacillus thuringiensis Se13 using Taguchi’s orthogonal array methodology

- Enhancing vitamin B12 content in co-fermented soy-milk via a Lotka Volterra model

- Species and number of bacterium may alternate IL-1β levels in the odontogenic cyst fluid

- Rheo-chemical characterization of exopolysaccharides produced by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria

- Benzo(a)pyrene degradation pathway in Bacillus subtilis BMT4i (MTCC 9447)

- Indices

- Reviewers 2018

- Yazar Dizini/Author Index

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Effects of calcium hydroxide and N-acetylcysteine on MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 in LPS-stimulated macrophage cell lines

- Synthesis of fused 1,4-dihydropyridines as potential calcium channel blockers

- Optimization of fermentation conditions for efficient ethanol production by Mucor hiemalis

- Covalent immobilization of an alkaline protease from Bacillus licheniformis

- Major biological activities and protein profiles of skin secretions of Lissotriton vulgaris and Triturus ivanbureschi

- Optimized production, purification and molecular characterization of fungal laccase through Alternaria alternata

- Adsorption of methyl violet from aqueous solution using brown algae Padina sanctae-crucis

- Protective effect of dexpanthenol (vitamin B5) in a rat model of LPS-induced endotoxic shock

- Purification and biochemical characterization of a β-cyanoalanine synthase expressed in germinating seeds of Sorghum bicolor (L.) moench

- Molecular cloning and in silico characterization of two alpha-like neurotoxins and one metalloproteinase from the maxilllipeds of the centipede Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans

- Improvement of delta-endotoxin production from local Bacillus thuringiensis Se13 using Taguchi’s orthogonal array methodology

- Enhancing vitamin B12 content in co-fermented soy-milk via a Lotka Volterra model

- Species and number of bacterium may alternate IL-1β levels in the odontogenic cyst fluid

- Rheo-chemical characterization of exopolysaccharides produced by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria

- Benzo(a)pyrene degradation pathway in Bacillus subtilis BMT4i (MTCC 9447)

- Indices

- Reviewers 2018

- Yazar Dizini/Author Index