Abstract

Interpretive captions play a crucial role in museum contexts by providing verbal information that complements and enhances visual artworks, thereby facilitating communication between visitors and the museum. However, despite their significance, there remains uncertainty about how these captions, generally perceived as secondary to the artworks, vary in their enhancing roles. In response to this gap, this study employs the multimodal corpus SemArt, taking a corpus-driven approach to explore the correlations between interpretive captions and classical European paintings. By applying the Latent Dirichlet Allocation method, themes and keywords were extracted from the interpretive captions and analyzed within a visual communication framework to uncover sub-genre variations and different text-image relations. The findings reveal seven sub-genres within interpretive captions and two types of text-image enhancement relations: content-enhanced and form-enhanced. This research highlights the benefits and challenges of using exploratory quantitative analysis to facilitate multimodal research, paving the way for broader applications of unsupervised machine-learning techniques in digital humanities.

1 Introduction

Museum texts are the language produced by the institution in written or spoken form for visitor consumption, contributing to the interpretive practices within the institution (Ravelli 2006: 1). In contemporary museums, various modes of textual presentations are employed, encompassing museum labels, wall texts, catalog entries, leaflets, explanatory panels, audio guides, websites, and interactive touchpads (Liao 2018: 47). Among these textual forms, museum labels can be further categorized into the noninterpretive identification labels, which provide essential information such as the name of the author, date, material, accession number, and donor details, as well as interpretive captions that serve to “invite participation by the reader” and to facilitate visitor-museum communication (Serrell 2015: 10, 39). This article focuses specifically on the exploration of the latter within the museum context.

Following Swales (1990: 46), interpretive captions constitute a distinct verbal genre characterized by a “shared set of communicative purposes.” This viewpoint reinforces the commonality of these texts, as reflected in the presence of homogenous moves and steps within the macro-structure that contributes to the stability of a genre. Bakhtin (1986) provides an alternative perspective that emphasizes the dynamic and creative nature of genres. Bakhin’s (1986) framework distinguishes between the primary genres such as everyday speech, and secondary genres, which include more complex forms like scientific research articles and artistic commentaries. The secondary genre, usually composed of the primary genres, absorbs and adapts various primary genres to address the communicative needs of different cultural communities (Bakhtin 1986: 62). Within this framework, interpretive captions belong to the secondary verbal genre and demonstrate heterogeneity as they describe different paintings in various museum contexts. In other words, it is essential to discuss the sub-genres as well as their variations within interpretive captions to obtain a comprehensive understanding of this specific verbal genre.

Expanding beyond the linguistic properties of interpretive captions, it is imperative to acknowledge the inherent multimodality of these texts as they always come together with the artworks being interpreted in the multimodal practices of museums. In the analytical framework proposed by Martinec and Salway (2005: 358) for examining text-image relations, the status of interpretive captions in relation to paintings is defined as unequal, drawing on Barthes’ trichotomy (1997). According to Barthes (1997), texts are positioned as subordinate to paintings, serving to provide contextual information regarding the historical background or narratives associated with the depicted paintings.

Martinec and Salway (2005) also employ the logico-semantic relations derived from Systemic Functional Linguistics theory (Halliday 1985, 1994) to elucidate multimodal relations, thereby labeling the relation between texts and images as enhancement (e.g., captions highlighting certain circumstantial qualities depicted in the painting), juxtaposed with strategies of elaboration (e.g., captions providing descriptive information about visible elements in the painting), and extension (e.g., captions offering interpretations of the painting’s potential meaning). It is worth noting that Martinec and Salway (2005) analyze the text-image relations in museum contexts as predominantly enhancement and extension. However, the relationship between interpretive captions and paintings is more complex, covering not only all three logico-semantic relations, but also their combinations. As exemplified in Table 1, for the paintings of the same artist (Jan Frans van Bloemen), with the same technique (oil on canvas) and in the same time frame (seventeenth to eighteenth century), relations beyond enhancement and extension are demonstrated.

Relations between interpretive captions and paintings.

| Mode | Relation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Elaboration | Elaboration + extension | Extension + enhancement | |

| Visual |  (Jan Frans van Bloemen, Classical Landscape https://www.wga.hu) |

(Jan Frans van Bloemen, Classical Landscape https://www.wga.hu) |

(Jan Frans van Bloemen, Capriccio View of Rome https://www.wga.hu) |

| Textual | This painting depicts a classical landscape with resting figures and a lakeside town beyond. | This painting shows a wooded classical landscape with two figures on a path by a Sphinx, a river and a fortified hill town beyond. Jan Frans van Bloemen spent most of his active career spanning nearly sixty years in Rome. The prime inspiration for his art is to be found in the work of Gaspar Dughet from whose classicizing style he derived many of his notions of color, composition and technique… |

Jan Frans van Bloemen, called l’Orizzonte was drawn to the beauty of Rome and the surrounding campagna and inspired by the classicizing landscape paintings of the Italian master Gaspard Dughet … The present canvas shows a capriccio view of Rome with figures resting in the foreground. Three women are engaged washing clothing at a picturesque fountain set in a secluded grove on the outskirts of the city. Two lean over the fountain … ready to make her way back towards Rome, whose monuments and terracotta tile roofed buildings are faintly outlined in the background. |

Despite the intricacy between interpretive captions and paintings, the decipherment of these texts has not aroused sufficient research interest. According to Cunningham (2019), existing studies on interpretive captions primarily focused on visitors’ reaction to texts (Kotler and Kotler 2000), readability assessment indices (Borun and Miller 1980), and the evaluation of linguistic choices from the lens of Systemic Functional Linguistics to identify linguistic problems that enhance or impede text comprehensibility (Ravelli 1996, 2006). These studies summarized significant linguistic features that facilitate meaning construction and enhance visitor-museum communication. Particularly for adult audiences, the added meaningfulness from the successful interpretation of these texts is found indispensable as it increases viewers’ enjoyment and enriches their aesthetic experiences in the process of artwork appreciation (Lin and Yao 2018; Russell 2003; Walker et al. 2017). However, the linguistic features contributing to sub-genre variations within interpretive captions as a verbal genre are still under-explored, even though they play a significant role in enhancing text accessibility.

In terms of intersemiotic text-image relations, pioneering studies have provided detailed investigations of the integration between diagrams and texts (Lemke 1998), mathematic formulas and texts in scientific articles (O’Halloran 1999), as well as the complementarity of texts and images in ads and newspapers (Royce 1998). Recent articles have conducted qualitative and quantitative examinations on multimodality in landscape designs (Shang 2020; Wu and Zhan 2022), built environment (Ravelli and McMurtrie 2016), photographic and film artifacts (Arnold and Tilton 2019), children’s picture books (Moya-Guijarro 2019; Painter et al. 2013), classroom feedback (Tyrer 2021), science education (Martin and Unsworth 2024; Unsworth et al. 2022), choreography (Maiorani 2020), video games (Toh 2018), and a variety of intersemiotic spaces. Nevertheless, limited attention has been given to museum settings and even less to the interplay between interpretive captions and their associated paintings.

In response to the digital turn that is occurring across disciplines such as sociology, cognitive science, and linguistics (Wildfeuer et al. 2018), museum industries, as well as museology and art curatorship, can benefit from embracing big data and digital humanities. For instance, the increasing accessibility of digital archives and online museum collections provides a prerequisite for digitalized research in museum contexts, which may bring out the latent potential of museum industries in multimodal services. Furthermore, supported by quantitative tools, specifically computational software designed for analyzing massive multimodal corpora, fine-grained descriptions of the interpretive captions as well as the caption-and-painting relations can be offered to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the verbal mode and its coordination with the visual mode in museum settings.

To better explain the research gap on text-image relations, and to explore the benefits and challenges of using unsupervised machine-learning techniques in facilitating multimodal research, the present article is grounded in the multimodal museum corpus SemArt with a research focus on sub-genre variations within the macro-genre of interpretive captions. By investigating the sub-genre variations in the verbal mode, the study intends to analyze and represent these variations in a visual communication framework, reconsidering the intricate relationships between texts and paintings in museum contexts. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Linguistic and multimodal research on interpretive captions is reviewed in Section 2, followed by a comprehensive introduction to the corpus and statistical tools in Section 3. Section 4 offers a detailed description of the thematic content of the interpretive captions and the text-image relations between interpretive captions and classical European paintings. The final section concludes the findings and limitations, providing implications for future research in multimodality.

2 Research on interpretive captions

2.1 Linguistic research

Ravelli’s (2006) seminal book provides the most extensive linguistic analysis of museum texts, presenting an analytical framework of three dimensions and elucidating the organizational, interactional, and representational roles of museum texts in visitor-museum communication. The organizational framework focuses on the study of genre variation at the macro level, section variation at the mid-level, and sentence structure variation at the micro level, combining meaning construction with the organization, layout, and directionality of museum texts. The interactional framework, on the other hand, is designed to explain the visitor-museum relationship. Through a detailed evaluation of the tone and voice of museum texts, this dimension shows the differences in social power and social distance in different grammatical and word choices, which reflects the stance of the museum and the expected relationship to be established in exhibitions. The last dimension delves into the interpretive captions, specifically the lexical and grammatical choices of the subject (participant) and predicate (process) in texts, demonstrating how our experiences of the material world are construed in the interpretive discourse.

Ravelli’s examination of museum texts has served as a cornerstone for several qualitative empirical research investigating interpretive captions. One such study is Miklošević (2015), which analyzed two interpretive captions extracted from the Art in Slovenia exhibition. Drawing on Ravelli’s trichotomous framework, Miklošević identified various organizational, interactional and representational features of these captions. Organizationally, it was observed that the complexity of these interpretive captions hindered the flow of information, as shifts between Themes (given information) and News (new information) disrupted the coherent structure of paragraphs. Interactionally, the formality of gallery texts rendered them highly informative, thereby signaling a stance of statement-making and establishing a unidirectional communication channel with museum visitors. Representationally, although these captions provided bibliographic information about the painters, they presuppose visitors have relevant knowledge of Slovenian art and geography. Paradoxically, while interpretive captions are meant to provide affordances for painting comprehension, the inadequacy of readability in these texts impedes visitors’ interpretation and leads to comprehension difficulty.

Compared to the aforementioned qualitative research, quantitative analysis of the interpretive captions has seldom utilized Ravelli’s model but has aimed to provide fine-grained descriptions of these texts at large. For instance, Cunningham (2019) used the UAM Corpus Tool to examine twenty-one pre-selected linguistic features (such as word count, mean word length, number of nouns, and number of passives) of the interpretive captions collected from nine online museums. Based on the co-occurrence of these features, the author developed five functional profiles of the explanatory texts, including 1) descriptive information, 2) expanded form-adding interpretation and process, 3) contextualizing, 4) process and interpretation with agency, and 5) narrative focus. Through a comprehensive analysis of the linguistic features, Cunningham (2019) unveiled the systematic variation within the interpretive discourse. The feature-function combinations provide implications for instructional material compilations in educational contexts and for public-face design in museum settings.

From the qualitative to the quantitative research on the linguistic features of interpretive captions, the aforementioned findings have yielded valuable insights for scholars and practitioners in museology and art curatorship, guiding them on what and how to write effective and impactful interpretive captions. It is also important to recognize that frameworks designed for qualitative analysis may not be as applicable in quantitative analysis of interpretive captions.

2.2 Multimodal research

Multimodality, understood as the multiplicity of distinct modalities, is defined as “the use of several semiotic methods in the design of a semiotic product or event” (Kress and van Leeuwen 2001: 20). As noted by Liao (2023: 48), multimodal research investigates the combination and interaction between different semiotic modes in meaning co-construction. In a multimodal museum space, prevalent semiotic modes include verbal, visual, audio, gestural, movement, and spatial forms (e.g., McMurtrie 2016; Ravelli and McMurtrie 2016), which collaborate in concert and contribute to museum purposes by facilitating a holistic and immersive understanding of the exhibited content. In particular, when the verbal mode is represented by interpretive captions, previous multimodal studies in museum contexts predominantly explore the coordination between the verbal and audio modes, as well as the correlation between the verbal and visual modes.

Audio descriptions, often seen as an intersemiotic translation of interpretive captions to provide audible assistance for visually impaired visitors, have received growing attention in recent years (Soler Gallego 2019: 709). This focus aims to explore the synergy between verbal and audio modes. A survey conducted by The Open Art Project (Szarkowska et al. 2016) revealed that museum visitors, both with and without visual impairment, prefer shorter and more interpretative descriptions. However, the affective needs of the audience are actually in conflict with the neutral guidelines recommended for audio descriptions, resulting in the debate over subjective or objective approaches to museum accessibility.

Therefore, in the investigation of museum audio descriptions’ subjectivity degree, Soler Gallego (2019: 712) compiled a multimodal corpus consisting of the transcribed audio guides and the corresponding paintings from 14 museums. The focus of the analysis was the verbal representation of concepts, sensations, and emotions uttered by the audio describers. These subjective elements in the transcribed texts were discussed in the framework of visual communication (Dondis 2006; Fichner-Rathus 2014), with the visual paintings further categorized into three types based on the level of abstraction, including abstract, semi-abstract, and representational art. This categorization made it possible to examine how different levels of subjectivity are projected onto the visual components. The findings suggest that subjectivity is found in all three types of paintings, but the specific visual components to which subjective audio descriptions connect vary across different levels of abstraction.

Museum studies that concentrated on the verbal-visual mode liaison mainly explore the automatic multi-modal retrieval for semantic art understanding, intending to enable computers to understand human art at a higher level. In this regard, Garcia and Vogiatzis (2018) presented a novel multimodal corpus SemArt, which comprises a triplet of paintings, artistic attributes, and interpretive captions downloaded from the website Web Gallery of Art. The inclusion of interpretive captions in SemArt sets their research apart from previous analyses, as it facilitates a shift in the understanding of fine art from mere classification and object identification to the semantic interpretation of paintings. By encoding the verbal and visual modes, the representational information in these two modes was projected onto a shared multimodal space for image-text retrieval and vice versa. The results showed that machines still underperform relative to humans, with a retrieval accuracy below 50 % (45.5 %), despite some meaningful representations and multimodal connections being successfully acquired. Similarly, Wang (2017) extracted the thematic content from interpretive captions that accompany 1,200 Chinese landscape paintings and established a full image-text retrieval database, featuring cross-referenced information to enhance semantic art comprehension.

The above monomodal and multimodal research provides valuable operational frameworks and statistical methods for thorough examinations of interpretive captions in museum contexts. Nevertheless, a significant aspect that remains unexplored pertains to the relationship between the interpretive captions and their accompanying paintings, which in essence reflects the intricate connection between the verbal and visual modes in the multimodal museum space. To address the complexity of text-image relations in museum settings, this article adopts a bottom-up approach by initially extracting the prototypical sub-genres subsumed in the interpretive captions. In addition to the linguistic analysis, the sub-genre variations in the verbal mode will be projected onto the visual mode to demonstrate various text-image relations at play.

3 Methodology

3.1 The multimodal corpus SemArt

The SemArt corpus is a multimodal dataset originally designed for text-image retrieval tasks (Garcia 2018). The corpus comprises a collection of 21,384 European fine-art reproductions sourced from the online website Web Gallery of Art, spanning the period from the ninth to the twentieth century. Each painting in the corpus is accompanied by the corresponding artistic attributes and interpretive captions, thereby forming a data sample. In each sample, the noninterpretive attributes introduce the Author, Title, Genre, School, and Timeframe of the associated painting. According to Garcia and Vogiatzis (2018: 4), the corpus encompasses 3,281 authors (e.g., Vincent van Gogh), 14,902 titles (e.g., Still-Life and Self-Portrait), 10 artistic genres (e.g., landscape, religious), 26 artistic schools (e.g., Italian, Finnish) and 22 timeframes (periods of 50 years between 801 and 1900).

In terms of interpretive captions in SemArt, 70 % of these texts are short, containing less than 100 words. Furthermore, the distribution of vocabulary in these captions follows Zipf’s law. As an exploratory study, a total of 1,000 random data samples were collected from the original SemArt dataset with the overall size of the interpretive captions of 100,071 words.

3.2 The corpus-driven method of Latent Dirichlet Allocation

To extract the emergent features of the SemArt multimodal corpus, the quantitative method of Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) was employed in the present study. LDA is an unsupervised machine-learning technique commonly used for document or text categorization (Blei et al. 2003). As a bag-of-words model, LDA treats the input texts as collections of individual words and captures the conditional distribution of these words to form text clusters, including high-frequent collocates and co-occurring words in a broader context.

In this study, specific modifications were made to the stopword list, which typically contains words commonly occurring in multiple input texts to optimize the separation of the interpretive captions. Therefore, words such as painting(s), painter(s), art(s) and artist(s) were added to the stop-word list. In addition, the LDA modeling was implemented using R language and executed in the R environment with the aid of the “ldatuning” package (Nikita and Chaney 2020). Compared to other packages, “ldatuning” offers four embedded scalars, namely, CaoJuan2009, Deveaud2014, Griffiths2004, and Arun2010, which facilitates the evaluation of model performance and helps to determine the appropriate number of clusters in the final LDA model. These clusters represent different topics of the interpretive captions, with each topic containing keywords that indicate the thematic content of an array of similar texts.

The output of the LDA model is separated into left and right panels. A visual representation of the topics in the form of circles is produced on a two-dimensional coordinate system in the left panel. The distance between these circles indicates inter-topic similarity, while the size of the circles represents the number of tokens covered by each topic. The right panel demonstrates the top 30 most relevant terms associated with each topic, which were crucial clues in the identification and extraction of thematic content.

As the interpretive texts serve to describe the corresponding paintings, the variation of thematic content across different topics reflects the diversity of the paintings themselves. In other words, the emerging topics derived from the verbal captions can be associated with visual paintings of specific types, schools, and time frames. Within the multimodal corpus SemArt, the artistic attributes Genre, School, and Time Frame are utilized to store relevant information about the associated paintings. The Genre variable includes various types of paintings, encompassing historical, interior, landscape, religious, mythological, portrait, still-life, study, and others. The School variable consists of twenty-two different artistic schools, namely, American, Austrian, Belgian, Bohemian, Catalan, Danish, Dutch, English, Flemish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Netherlandish, Norwegian, Other, Polish, Russian, Scottish, Spanish, Swedish, and Swiss. The Time Frame variable provides the historical context in which the painting was produced, containing sixteen fifty-year periods from the ninth to the twentieth century. The above artistic details function as guiding factors in summarizing the thematic content linked to each topic.

3.3 The visual communication framework

Upon the extraction of thematic content, the subsequent investigation of text-image relations will be analyzed in a visual communication framework (Soler Gallego 2019). As reported by Soler Gallego (2019: 714), the visual communication framework is adapted from the work of Dondis (2006) and Fichner-Rathus (2014), which involves two levels of communication: content and form (see Table 2).

Taxonomy of components of visual communication.

| Visual Communication | Content | Icon | |

| Symbol | |||

| Opinion | |||

| Form | Technique | ||

| Materials | |||

| Composition | |||

| Visual Elements | Dot, Line, Shape, Space, Dimension, Movement, Direction, Texture, Colour, Tone | ||

The content components are comprised of iconology and symbol used in the visual images, which serve to depict the subject matter in art and express the artist’s opinion for meaningful communication. Conversely, the formal components refer to the physical aspects of the artwork, including technique, material, and composition that contribute to the art design as well as fundamental visual elements such as dot, line, shape, space, dimension, movement, direction, texture, tone, and color.

The detailed taxonomy of components in visual communication functions as a valuable tool for categorizing the keywords associated with each sub-genre into the corresponding level of communication, allowing for the placement of sub-genres on a content-form continuum and also projecting the monomodal sub-genre variations of interpretive captions to the multimodal text-image relations. The reason for choosing this taxonomy,[1] which seems to scratch the surface of visual elements in paintings, rather than Ravelli’s trichotomy (2006) and Kress and van Leeuwen’s visual grammar (1996, 2021), is due to operational concerns, as it would be exponentially difficult to conduct a fine-grained analysis of each element in a quantitative study which involves 1,000 paintings.

4 Mono-modal analysis of the interpretive captions

4.1 Salient topics in the LDA model

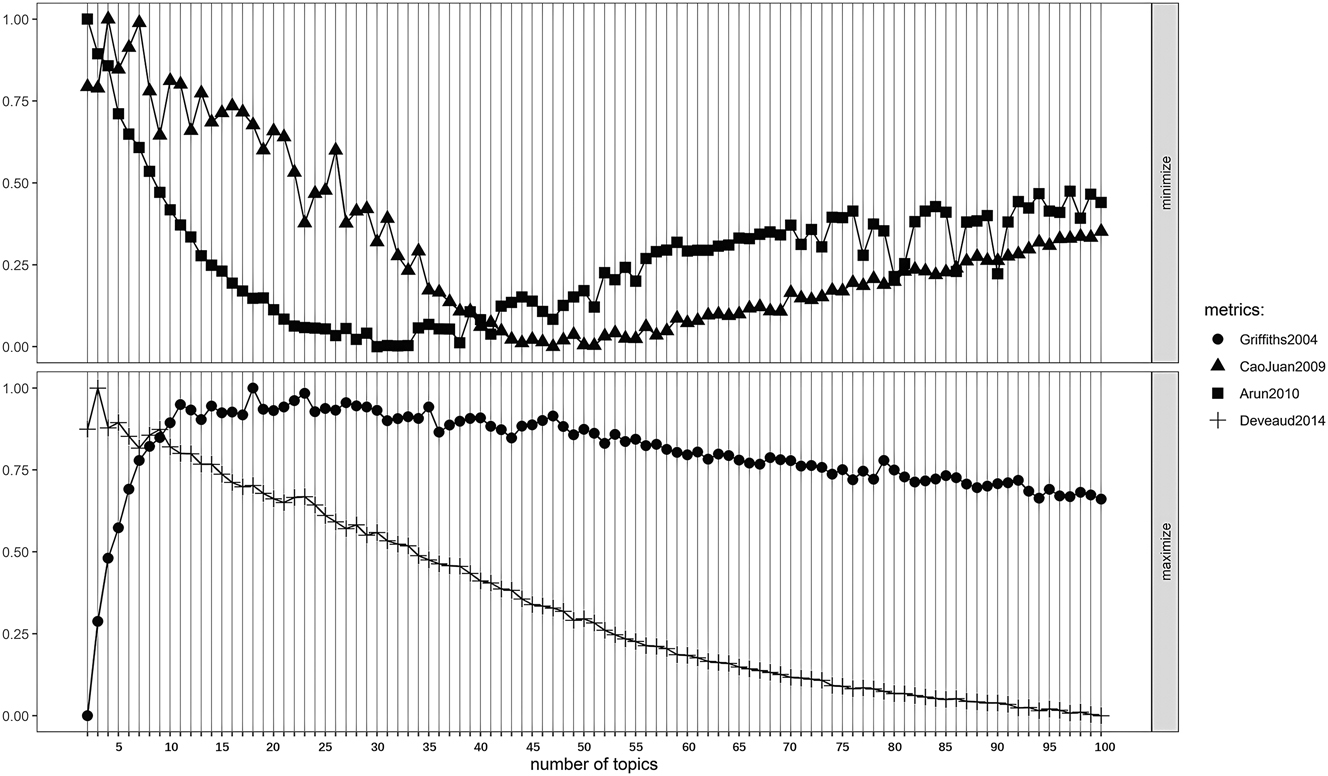

The first step concerning the textual mode is to explore the salient topics emerging from the interpretive captions. With no prescribed number of topics, the situations of dividing interpretive captions into two to one hundred topics are tested. The optimal number of topics, referring to the situation where each topic is well-separated from the others with the greatest inter-topic distance on the visualized plot, is preliminarily determined by the indices of four metrics. As demonstrated in Figure 1, Arun2010 and CaoJuan2009 display a downward trajectory followed by an upward trend, with the lowest points referring to the minimal number of topics recommended by the tuning algorithm. In contrast, Griffiths2004 and Deveaud2014 show an upward trend followed by a downward tendency, with the highest points indicating the maximal number of topics. In the present study, Arun2010 and Griffiths2004 were selected as the scalars that represent the minimal and maximal number of topics because these two metrics perform better with their smoother parabola-like curves.

The performance of four metrics in two to one hundred topics.

Based on the above two metrics, the range of optimal numbers was decided between eighteen to thirty, and the corresponding plots were generated accordingly to help decide the number of topics. However, it was observed that, within this range, circles in the plots were not completely separate and the keywords in each topic had limited descriptive powers. These findings suggest that the range suggested by the scalars in the model did not effectively cluster the interpretive captions, thereby necessitating manual adjudication for topic selection.

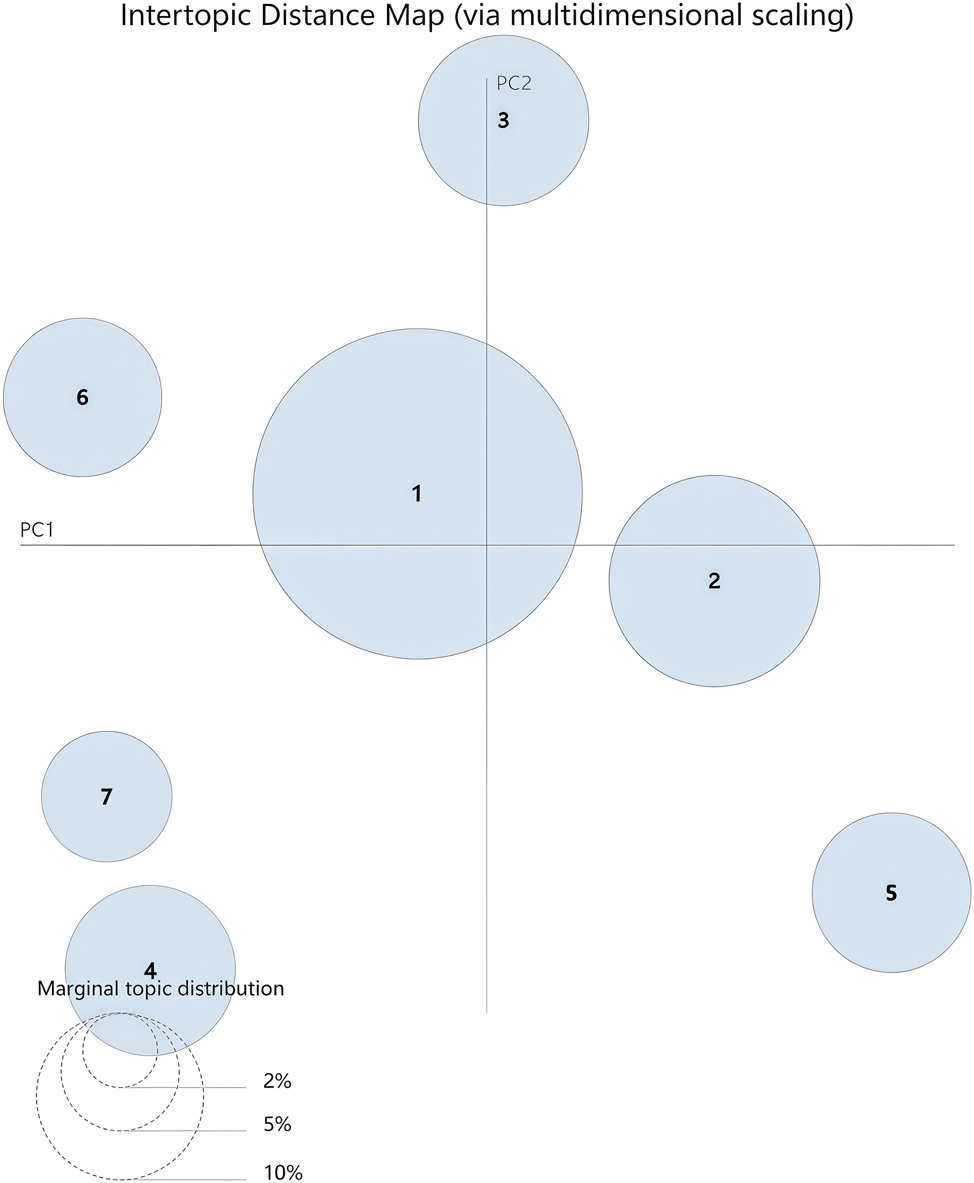

Models with two to seventeen topics were manually tested and the optimal number of topics was determined to be seven. As shown in Figure 2, with each circle separated from the others, the intertopic distance map indicates good discrimination for the highly frequent words in the sample data.

Intertopic distance map of the sample data.

For each topic, the top 30 most relevant keywords and the percentage of tokens covered by the corresponding topic are demonstrated in Table 3. The subsequent analysis focuses on the thematic content of each topic based on these identified keywords.

The keywords and percentage of tokens in each topic.

| Topic | Keywords | Tokens |

|---|---|---|

| Topic 1 | landscape, light, composition, life, subject, background, style, scene, depicted, color, dutch, genre, view, head, scenes, highly, nature, foreground, elements, still-life, canvas, earlier, influence, caravaggio, features, theme, attention, blue, drawings, rubens | 39 % |

| Topic 2 | christ, virgin, john, child, saint, altarpiece, church, mary, cross, baptist, madonna, master, angels, central, wing, chapel, scenes, triptych, adoration, peter, apostles, alter, mother, center, represents, ursula, birth, legend, composition, holy | 16 % |

| Topic 3 | wall, scenes, scene, fresco, ceiling, decoration, cycle, walls, set, chapel, nave, frescoes, church, view, sala, palace, life, choir, cecilia, vault, francesco, roman, interior, villa, decorated, boccaccio, architecture, palazzo, central, hall | 10.4 % |

| Topic 4 | portrait, portraits, king, court, wife, rembrandt, london, charles, daughter, queen, son, amsterdam, prince, married, phillip, collection, england, henry, royal, family, iii, iv, allegorical, commissioned, anne, marriage, english, sir, sitter, grand | 10.4 % |

| Topic 5 | subject, scene, god, story, tree, love, king, mythological, venus, music, garden, female, diana, symbol, classical, ovid, symbols, allegory, women, boy, apollo, putti, beauty, arms, image, death, cupid, male, poet, brought | 9.1 % |

| Topic 6 | venice, florence, san, executed, raphael, giovanni, rome, church, roman, family, style, font, medici, maria, venetian, italian, workshop, lorenzo, size, bellini, santa, composition, classical, influence, sant, commissioned, antonio, giuseppe, times, grand | 9 % |

| Topic 7 | french, david, paris, louis, style, gogh, life, salon, le, france, impressionist, rome, jh, monet, friend, views, royal, paint, xiv, delacroix, gauguin, goya, neo, exhibited, jean, version, death, saint, el, greco | 6.1 % |

4.2 Sub-genres in interpretive captions

Overall, seven sub-genres were summarized based on the keywords listed in Table 3, including 1) Dutch landscape and genre paintings, 2) Religious art and iconography, 3) Decorative fresco paintings in interiors, 4) Portraiture of royalty and aristocracy, 5) Mythological and symbolic representations, 6) Italian Renaissance and its influences, and 7) French art and its artists. The following paragraphs introduce the correlation between related keywords and the thematic content of the corresponding sub-genre. For each sub-genre, a set formed by an interpretive caption containing the most frequent keywords and its associated painting is sourced from the SemArt corpus to demonstrate the text-image relation in terms of thematic density from linguistic perspectives.

4.2.1 Sub-genre 1: Dutch landscape and genre paintings

Sub-genre one represents various elements that characterize Dutch landscape and genre paintings. The keywords landscape, life, and still-life explain the different subjects depicted in associated paintings, such as natural landscapes and scenes from daily life. The understanding of the subjects in related paintings contributes to the definition of specific artistic styles employed in these artworks. The keywords style, dutch, and genre underscore the association between the landscape and genre scenes with the Dutch school, as Dutch paintings tend to emphasize the naturalistic representations and genre scenes of everyday life. The extended list of keywords of light, composition, foreground, background, color, and canvas demonstrates the artistic attributes of corresponding paintings, introducing how and where the natural elements are arranged. Moreover, as nature serves as a typical theme in the associated landscape paintings, the mention of the Italian artist Caravaggio and the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens reflects their impact on Dutch naturalistic art, which influences the attention of artistic elements within paintings and the overall thematic composition. By connecting the keywords, we are enabled to gain a comprehensive understanding of the subject matters, visual representations, technique choices, and the underlying messages expressed through Dutch landscape and genre paintings.

Example (1) exemplifies a representational interpretive caption belonging to Topic 1, and Figure 3 displays the corresponding painting of this example. The caption begins by describing the Brabant village, which indicates the painting subject as a landscape painting. The mention of light, colors, composition, and right hand foreground suggest how the artistic choices of techniques create a harmonious and monochrome atmosphere of the painting. The skating scenes in winter reflect the common daily life scene commonly found in Dutch genre paintings, symbolizing the theme of the uncertain nature of existence with the theme echoed by the classic semiotics of the bird traps. Overall, this example aligns with the topic of elements in Dutch Landscape and Genre Paintings and sheds light on the connection between the visual mode of these paintings with the verbal mode of various linguistic choices in this sub-genre.

Demonstrative painting for sub-genre one: Dutch landscape and genre paintings.

| Bathed in a gentle, suffused light, softened by the snow, a Brabant village sets the scene for the pleasures on the ice. The unity of the ivory-toned colors makes this an almost monochrome painting, heralding the Dutch winter scenes of the coming century. The bird traps, like the one in the right hand foreground, symbolized in the literature of the time the baits of the devil for careless souls. Similarly, artists frequently used skating scenes to express the uncertain (slippery) nature of existence. With his at once precise and synthetic vision of the world, the artist has managed to renew this theme with masterly skill. (Pieter the Elder Bruegel, Winter, 1567) |

4.2.2 Sub-genre 2: religious art and iconography

The thematic content of this sub-genre is summarized as religious art and iconography, particularly centered around Christian themes and figures. Keywords that ranked high in the wordlist such as christ, virgin, child and saint imply the artistic subjects of significant Christian symbols depicted in associated paintings. The portrayal of divine stories and miraculous events that involve these Christian subjects is reflected in keywords like apostles, birth, adoration, and legend. Furthermore, architectural keywords of alter, church, and chapel depict the context and background of these religious artworks. The composition of associated art is reflected by the presence of the keyword triptych, which refers to the format of multiple panels commonly employed in religious imagery. Generally, this sub-genre of interpretive captions encompasses divine figures, sacred settings, holy iconography, and symbolic representations of religious artworks.

Example (2) illustrates this specific sub-genre of interpretive captions with the associated painting exhibited in Figure 4. The inclusion of St. Ursula and the Virgin Mary indicates the presence of religious figures and Christian iconography as both women played significant roles in religious art, with the former often depicted as a protective saint and associated with martyrdom while the latter the mother of Jesus Christ. The description of the Christ Child and the two kneeling nuns further symbolizes the religious theme of Jesus’s incarnation and the act of devotion. The religious context and the sacred atmosphere of this painting are signified by the mention of the Gothic chapel, which is commonly associated with religious buildings. Through the portrayal of the above religious figures, setting and symbolism, this excerpt reinforces its connection to the sub-genre of religious art and iconography, showcasing how the artistic elements and meanings in the paintings can be represented linguistically.

Demonstrative painting for sub-genre two: Religious art and iconography.

| The narrow sides of the chest portray St. Ursula at one end, holding an arrow and protecting the holy virgins under her cloak, and the Virgin Mary at the other, with the Christ Child and two kneeling nuns. Both scenes are located in the interior of a Gothic chapel, painted in such a way as to suggest the interior of the reliquary. (Hans Memling, St. Ursula shrine: St. Ursula and the Holy Virgins – Virgin and Child, 1489) |

4.2.3 Sub-genre 3: decorative fresco paintings in interiors

The thematic content of this sub-genre centers on decorative fresco paintings in interiors. Among the seven sub-genres within the interpretive captions, this sub-genre stands out due to its special attention to artistic technique (fresco and frescoes). In addition to the technique, the composition of related fresco paintings was reinforced by the use of the keyword cycle, which creates a series of interconnected scenes or narratives that form a cohesive thematic unity within an architectural space. With the primary function of fresco paintings being decorative for religious architectures, these pictures were normally discovered on the walls, vaults, and ceilings in places such as church, chapel, nave, and choir. Moreover, these paintings were observed in grand residences such as palace, sala, villa, palazzo, and hall as well, which implies the significance of ornamental design in aristocratic settings. While the content of these paintings was not signified in the interpretive captions, the specific mention of Saint Cecilia, the symbol of music in religious artworks, further suggests a connection between frescos and the musical worship performed by choirs in church settings. By incorporating these keywords, it becomes evident that within this sub-genre of interpretive captions, the technique, subject matter, and location of related fresco paintings outweigh the content within the decorative imagery.

As is shown in example (3) and Figure 5, the following excerpt provides specific details about the cycle of frescoes depicting the life of St. Francis in Montefalco. The description of the placement and arrangement of the picture sequence reflects the intentional fresco design within the chapel, emphasizing the contribution of fresco cycles to the overall decorative ensemble of the architectural space and the cohesive aesthetic experience visually and audibly.

Demonstrative painting for sub-genre three: decorative fresco paintings in interiors.

| The cycle of St. Francis in Montefalco contains a total of 19 episodes from the life and work of the saint, arranged in a total of 12 pictures and a lost stained glass window. The cycle of pictures extends above the choir stalls along the five walls of the apsidal chapel, in three rows arranged one above the other. The sequence of pictures ends in the six vaulted fields with St Francis in glory with five saints from the Franciscan order. The scene following the Vision of the Church Militant and Triumphant was depicted on a lost stained glass window that originally decorated the narrower central wall of the choir, and which has now been replaced by an unpainted arched window. (Benozzo Gozzoli, Scheme of the fresco cycle, 1450–52) |

4.2.4 Sub-genre 4: portraiture of royalty and aristocracy

The thematic content in this sub-genre focuses on the portraiture of individuals from royalty and aristocracy, as indicated by keywords such as portrait, portraits, court, king, queen, prince, royal, and family. The historical context of associated paintings is implied through references to specific figures and their relationships, including notable names like charles, phillip, anne, and henry, which correspond to specific periods. Additional keywords such as married, son, daughter, and wife provide extra information about the lineage connections between the portrayed subjects and those royal figures. Furthermore, the concept of courtly patronage emerges from the keywords collection, commissioned, and allegorical, indicating the specific purposes of the corresponding portraits and the importance of portraiture as a means of power expression. The significance of these portraits is also reflected in their authors, as it was the most renowned artists such as Rembrandt that might be commissioned to create the artworks. Overall, this sub-genre introduces the practice of portrait painting and its association with courtly patronage, wherein members of the royal and aristocratic families were portrayed by famous artists to highlight their connections within the courtly circles and to convey their royal status.

As exemplified in excerpt (4) and depicted in Figure 6, the purpose of portrait miniatures was to immortalize the monarch’s triumph. With the identity of the lady portrayed in the picture discussed in detail, these two aspects reinforce the thematic content of portraiture in royalty in sub-genre four.

Demonstrative painting for sub-genre four: portraiture of royalty and aristocracy.

| The first portrait miniatures were produced in France, their precursors being the small circular works commissioned by Francis I to celebrate the victory of Marignano in 1515. Jean Clouet was among the early practitioners of this format, which seems to have arrived in England by 1526 in the form of French royal portraits. The identity of the lady is uncertain – the Romantic view of the 1840s judged it to be a portrait of Henry VIII’s tragic fifth wife, Catherine Howard, executed for alleged adultery, although no ascertainable portrait of her exists elsewhere. (Hans the Younger Holbein, Portrait of an unknown lady, 1541) |

4.2.5 Sub-genre 5: mythological and symbolic representations

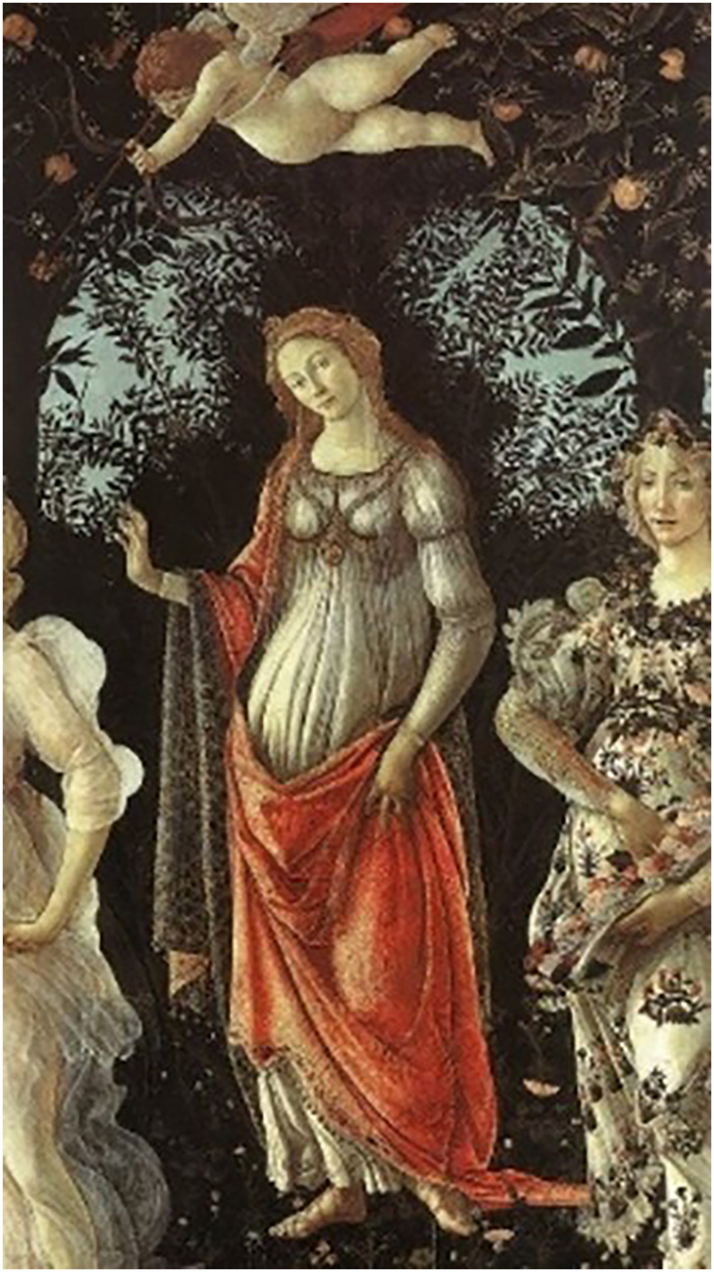

The thematic content of topic five focuses on mythological and symbolic representations, which emphasize the mythological narratives, symbols and allegories in associated paintings. As the subjects of mythological paintings are often prominent figures from classical literature, keywords such as god, apollo, venus, diana, and ovid (e.g., the work of Ovid), as well as the keywords indicating the virtues represented by these mythological characters (love and beauty) appeared in the wordlist. In addition to the mythological scenes, symbolism plays an essential role in this sub-genre. The involved symbols range from concrete objects like trees to abstract representations like cupid and putti, with the latter carrying metaphorical implications beyond their literal meanings. The content of this sub-genre depicts how artists have drawn inspiration from mythological legends to create visually appealing and intellectually engaging artworks that explore timeless themes of human nature.

The mythological theme of sub-genre five can be verified from excerpt (5), which provides an interpretation of a painting belonging to the mythological genre (Figure 7). In the excerpt, two mythological figures are mentioned, namely, Venus and Amor, both of whom are symbols of love. The detailed description of the growth and blooming in the divine spring garden indicates the vitality of nature. With Venus presenting a welcoming gesture in front of the divine garden, this painting invites the audience to appreciate and love nature. Additionally, the blindfolded portrayal of Amor introduces another layer of symbolism, as the aimless shooting of love arrows represents the unpredicted and irrational nature of love.

Demonstrative painting for sub-genre five: mythological and symbolic representations.

| The divine spring garden, in which hundreds of species of plants and flowers are growing, nearly all of which flower in April and May, is being looked after by Venus, the goddess of love. Behind her is a myrtle tree, one of her symbols. She is raising her hand in greeting and welcoming the observer to her kingdom. Overhead, her son, Amor, his eyes blindfolded, is shooting his arrows of love. (Sandro Botticelli, Primavera, 1482) |

4.2.6 Sub-genre 6: Italian Renaissance and its influences

The thematic content in sub-genre six introduces Italian Renaissance art and its influences. Originating in Florence (florence) and later extending its reach to Venice (venice), the Renaissance movement developed and bloomed in Italy. The Renaissance activists looked to ancient Greek and Roman (roman) art for inspiration, thereby leading to a revival of classical ideals (classical) and motivating a shift of artistic techniques (composion, style, and size) in art creation. At that time, Italian artists usually collaborated in art production, painting in workshops (workshop) and receiving commissions (commissioned) for specific artworks following the preferences and requirements of their patrons. Notably, the Medici family (mecidi and family), in particular Lorenzo the Magnificent (lorenzo), played a significant role in supporting artists and fostering cultural advancement, contributing to the flourishing of Renaissance art in Florence. The other significant center Venice was famous for the Venetian (venetian) school of paintings, giving birth to influential artists like Giovanni Bellini (giovanni and bellini). Through the examination of the artistic content and techniques, as well as the prominent regions and artists, the theme of this sub-genre represents and emphasizes the influences of the Italian Renaissance on art.

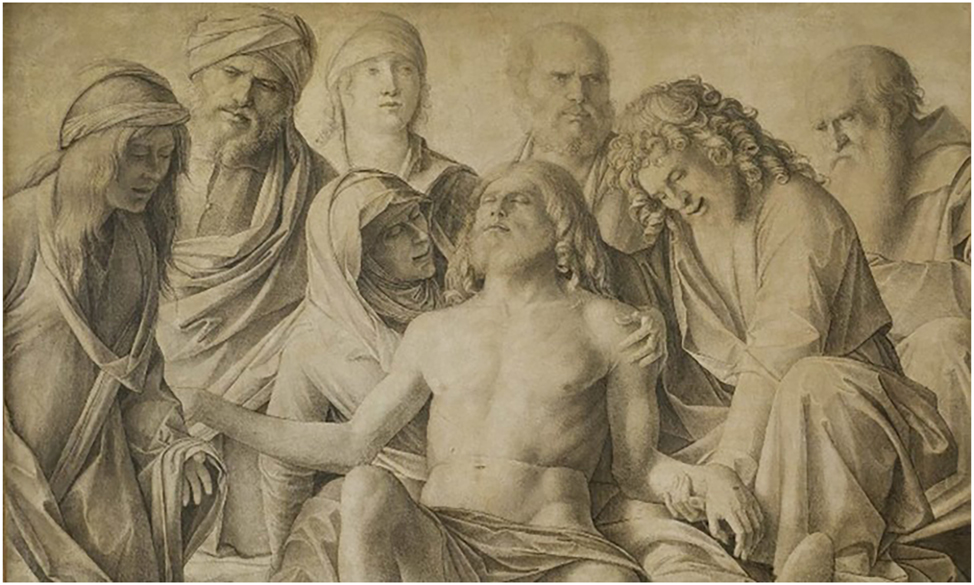

From example (6) and its associated painting (Figure 8), it is observed that the thematic content in sub-genre six captures the main idea conveyed in the interpretive captions. For instance, as a prominent Venetian artist, Bellini did not work by himself but he cooperated with a group of other artists in his workshop, underscoring the inter-connectedness among artists during Renaissance time. In addition, the artistic technique of chiaroscuro, characterized by the contrasting display of light and dark, was widely employed by Renaissance artists to depict death and enhance volume in their compositions. Moreover, the subject of Christ and the realistic way of portraying this spiritual figure reinforces the characteristics of Italian Renaissance art. The underlying concept of humanism is highlighted and conveyed through the artistic design of communication between the sacred group and those worshipping. Such a “wall-breaking” composition serves to bridge the gap not only between the divinity and the worshippers but also between the artist and the audience, thereby inviting emotional engagement from the viewers.

Demonstrative painting for sub-genre six: Italian Renaissance and its influences.

| Bellini and his workshop executed several variants of the subject Lamentation over the Dead Christ. The rare chiaroscuro of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, a gift made by Alvise Mocenigo to the Grand-duke of Tuscany is one of them. This is a more crowded composition than the previous “imago pietatis,” in which the very isolation of the figures becomes a diaphragm that separates the spectator from the drama. Here the prominent knees of Christ, and his abrupt foreshortening sharply break this ideal wall and bring the sacred group closer to, and therefore in more immediate communication with, those worshipping. (Giovanni Bellini, The lamentation over the body of Christ, 1500) |

4.2.7 Sub-genre 7: French art and its artists

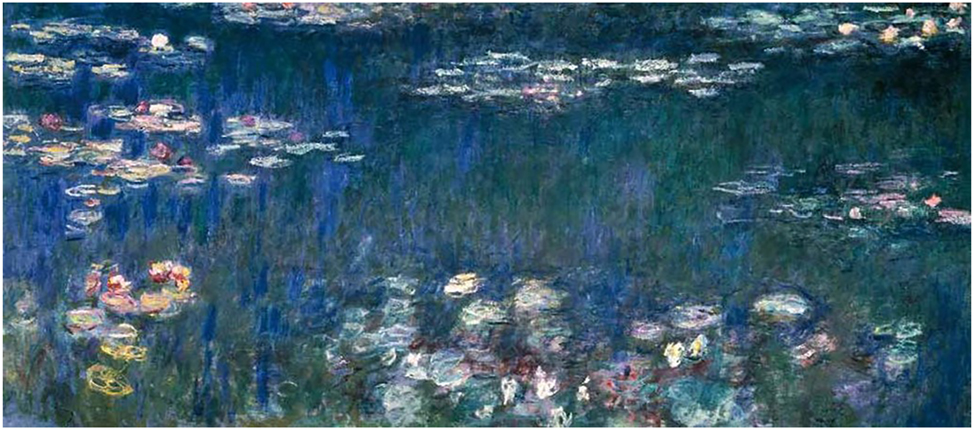

The keywords in topic 7 reflect the thematic content of French art and its various artists. As observed in the wordlist, names of prominent artists were prevalent in texts of this sub-genre, encompassing Vincent van Gogh (gogh), Jacques-Louis David (david), Eugène Delacroix (delacroix), Paul Gauguin (gauguin), and Francisco Goya (goya). These artists were either French or associated with French art, representing different schools of art movements in France. For instance, Claude Monet (monet) and Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (jean) were key figures representative of the Impressionist movement, emphasizing the fleeting impressions of light and color in outdoor settings. Furthermore, French art was majorly exhibited in the form of salons (salon) in the eighteenth and ninteteenth centuries, thus explaining the attraction of Paris (paris) to various artists during that period. In summary, the content in this sub-genre highlights the influence of French art and the contributions of those pioneering artists.

As noted in example (7), the interpretive captions are quite brief, even though the painting (see Figure 9) was created by the renowned artist Monet, featuring one of his well-known themes. In addition, it is interesting that the interpretive captions provide detailed information about the museum’s location and the context of the painting’s acquisition (as shown by the italicized texts) rather than the realization of impressionism in this painting. This inclusion of extraneous information, though not directly related to the painting itself, indicates a specific focus of this sub-genre in the interpreting process.

Demonstrative painting for sub-genre seven: French art and its artists.

| Monet painted a cycle of water lily paintings, known as the Nymphéas. The eight paintings of the cycle are displayed in two oval rooms in the Musée de l’Orangerie, located on the bank of the Seine in the old orangery of the Tuileries Palace on the Place de la Concorde in Paris. The paintings were donated by Monet to the French government in 1922. |

To conclude, seven sub-genres are derived from the selected corpus data. The mono-modal analysis reflects the prominent and prototypical thematic meanings conveyed by the interpretive captions. Based on thematic density, the representative painting of each sub-genre is displayed to demonstrate the intersemiotic co-selection. The thematic-based relation between text and image could assist in the archiving of artworks, which facilitates easier retrieval and intuitive navigation for scholars and experts. The catalogue of paintings in terms of thematic similarities could also provide a clue to understand artistic trends, enhancing research in art history.

4.3 Sub-genre variations within interpretive captions: implications for multimodal text-image relations

Drawing on keywords extracted from the LDA model, the previous section introduced seven sub-genres encompassed in the macro-genre of interpretive captions. Figure 2 visually represents the distance between these sub-genres, suggesting the degree of (dis)similarity between them. For instance, sub-genres one and two are positioned next to each other, thereby indicating similarity between these two sub-genres, whereas the placement of sub-genre five and six highlights their significant dissimilarity.

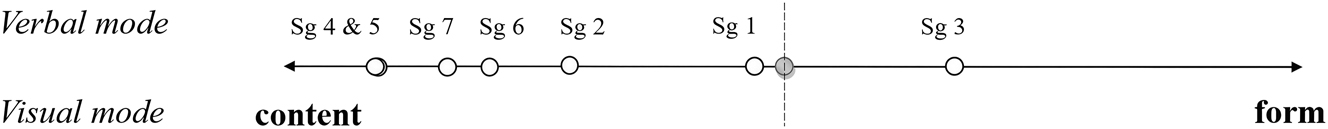

To systematically capture the variation across the seven sub-genres, a comprehensive analysis is conducted within the framework of visual communication. This analysis classifies the keywords from each sub-genre into content and form categories. By examining the proportions of content-related and form-related keywords, these sub-genres can be mapped along a content-form continuum. Table 4 presents the number of keywords for both categories in each sub-genre as well as their corresponding proportions. The sub-genre variations within interpretive captions are shown in Figure 10.

Keywords classification in the framework of visual communication.

| Sub-genre | Visual communication | |

|---|---|---|

| Keywords reflecting content | Keywords reflecting form | |

| 1 | 16 (53 %) | 14 (47 %) |

| 2 | 23 (77 %) | 7 (23 %) |

| 3 | 8 (27 %) | 22 (73 %) |

| 4 | 30 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| 5 | 30 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| 6 | 26 (87 %) | 4 (13 %) |

| 7 | 28 (93 %) | 2 (7 %) |

Sub-genre variation in the visual communication framework.

When sub-genre variations of the verbal mode are projected onto the visual mode, novel patterns of text-image relations become apparent. Among the seven sub-genres, sub-genre three distinguishes itself by establishing a close connection to the formal components of visual communication, indicating a form-enhanced relation between the interpretive captions and the visual paintings. In other words, texts representing the theme of Decorative fresco paintings in interiors reinforce the formation and structure of paintings, emphasizing the physical aspects of images instead of the subject matters.

On the other hand, the remaining six sub-genres demonstrate a content-enhanced text-image relation. Within these sub-genres, sub-genres four and five are positioned at the left end of the content-form continuum, displaying a strong emphasis on the content elements of paintings and giving minimal attention to formal aspects when interpreting portraiture and mythological narratives. In contrast to the previous two sub-genres, sub-genre one demonstrates a balanced focus on both content and form in visual communication, addressing both the intended message and the artistic techniques used to construct these messages in the description of Dutch landscape and genre scenes. The last three sub-genres, sub-genre seven, six, and two, maintain a focus on the content of visuals, though the degree of emphasis decreases across them. Interpretive captions of French art and its artist (sub-genre seven) show the highest content focus, while those of religious art show the lowest.

In summary, the overall variation of verbal sub-genres within the content-form continuum of visual communication suggests two types of multimodal text-image relations: form-enhanced and content-enhanced. These relations establish connections between the thematic content derived from the verbal semiotics and the artistic elements present in visual semiotics. Furthermore, the variety of sub-genres and the two text-image relations have implications for the “digitization” and “digitalization” of art museums (Yap et al. 2024). Digitization refers to the conversion of physical artefacts into digital formats for storage, accessibility, and general use (Stauffer 2012). Conversely, digitalization involves using technology such as virtual reality and augmented reality to promote visitor engagement (Choi and Kim 2021).

During digitization, art museums create digital archives for their collections. A common presence of this process is the display of digital content on museum website (Yap et al. 2024). For example, the National Art Museum of China archives its digitized paintings based on object title, artist, style, and time period. Although interpretive captions are documented online alongside the related artistic information, they are not cross-referenced with the paintings, which possibly result from the diversity and complexity of the texts. However, by using the machine-learning technique Latent Dirichlet Allocation, we have found a way to categorize interpretive captions through genre analysis. The sub-genres identified within the macro-genre of interpretive captions enable us to summarize the thematic content derived from linguistic associations, offering an inventory of themes. These themes can be used as labels to improve the searchability of paintings in the digitization process of art museums.

In terms of digitalization, the typical onsite tools used in museums are virtual reality headset and augmented reality glasses (Fissi et al. 2022). Carvajal et al. (2020) suggest that these digital tools provide an interactive virtual environment which stimulates users and “generates a sense of immersion.” In art museums, visitors wear headsets or glasses to enter the virtual world where they can access detailed information and supporting messages about individual paintings. Beyond elaborating on single artworks, these digital tools also enable the simultaneous display of multiple paintings. In this context, thematic variations and text-image relations could be incorporated into these devices as educational content. This approach would draw visitors’ attention to the form or content of paintings within the same thematic category, effectively demonstrating their similarities.

5 Concluding remarks

The prevalence of multimodality in contemporary culture has promoted both qualitative and quantitative research to re-evaluate the relationships between various modes in modern times (Serafini and Reid 2019). In the present study, the examination of sampled interpretive captions and the associated European paintings from the multimodal corpus SemArt is intended to offer an example of bottom-up analysis to systematize text-image relations. This study aims to open up a dialogue on the benefits and challenges of using an unsupervised machine-learning technique to facilitate multimodal research.

Initiated in the linguistic mode, this article begins by presenting seven sub-genres englobed in the macro-genre of interpretive captions, along with their corresponding thematic foci. Utilizing concepts from visual communication, the study extends its findings to the visual mode to capture the multimodal nature inherent in museum contexts. Two types of text-image relations are concluded, including “content-enhanced” and “form-enhanced” relations. We hope the two enhancement relations provided in the present study will inspire future quantitative research to address the intricacies of text-image relations, and open up broader applications in the field of digital humanities.

Nevertheless, the limitations of the study must be recognized. Firstly, the selected corpus SemArt represents a collection of texts and images sourced from the website Web Gallery of Art. Although the online display of paintings and interpretive captions resembles museum exhibitions, the collected data falls short of capturing the intricate nature of an actual museum exhibition. In other words, SemArt is not a standard museum corpus. It lacks essential metadata such as the topic, purpose, and target audience of exhibitions, which serves as key information that guides curators in designing exhibitions and shaping the text-image relations within them. Future research on text-image relations in museum contexts needs to concern these factors and investigate how virtual platforms might evolve to present the dynamics of physical exhibition spaces.

Secondly, the visual communication framework adopted in our study could only represent the surface forms of the images, which is indeed limiting to practicing curatorship. While it may not encompass the full depth that an expert curator provides, our study serves as a preliminary exploration into the potential of using machine learning techniques in museum contexts. For tailored curatorial practices, more targeted, applicable, and operationally effective frameworks could be used to assist in exhibition design.

In conclusion, our study’s focus on formal elements may appear to restrict our analysis to mere variations within these elements across interpretive captions. However, this methodological approach is firmly rooted in a well-established academic tradition, which draws on foundational theories from Thurstone (1935), Carroll (1960), and Biber (1988) in linguistics and psychology. These theories underscore the value of examining formal elements to uncover genre and stylistic differences in texts. Therefore, by focusing on these variations within interpretive captions, we aim to deepen our understanding of text-image relations and their implications in the museum context. While our findings show insightful uses of machine learning techniques in multimodal studies, they also emphasize the need for interdisciplinary cooperation (e.g., between linguistics and art curatorship) to fully capture the intricacy of multimodality.

Funding source: The China MOE Major Project Fund of Key Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences

Award Identifier / Grant number: 22JJD740012

Acknowledgments

This study is the result of a joint postgraduate seminar on Language and Design, co-organized by the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) and Beijing Foreign Studies University (BFSU). We extend our sincere gratitude to Professor Ninghui Hao of CAFA for hosting the seminar and his valuable feedback and encouragement for the project. We are also deeply thankful to Editor-in-Chief Dr. Jamin Pelkey and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the manuscript.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by The China MOE Major Project Fund of Key Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences, under Grant [22JJD740012].

References

Arnold, Taylor & Lauren Tilton. 2019. Distant viewing: Analyzing large visual corpora. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 34(Suppl. 1). i3–i16. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqz013.Suche in Google Scholar

Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich. 1986. The problem of speech genres. In Caryl Emerson & Michael Holquist (eds.), Speech genres and other late essays, 60–102. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.10.7560/720466-005Suche in Google Scholar

Barthes, Roland. 1997. Rhetoric of the image. In Image – music – text, 32–51. London: Fontana.Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas. 1988. Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511621024Suche in Google Scholar

Blei, David M., Andrew Y. Ng & Michael I. Jordan. 2003. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 3. 993–1022.Suche in Google Scholar

Borun, Minda & Maryanne Miller. 1980. What’s in a name? A study of the effectiveness of explanatory labels in a science museum. Philadelphia: The Franklin Institute Science Museum and Planetarium.Suche in Google Scholar

Carroll, John B. 1960. Vectors of prose style. In Thomas A. Sebeok (ed.), Style in language, 283–292. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Carvajal, Loaiza, Daniel Alejandro, Maria Mercedes Morita & Gabriel Mario Bilmes. 2020. Virtual museums: Captured reality and 3D modeling. Journal of Cultural Heritage 45. 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2020.04.013.Suche in Google Scholar

Choi, Byungjin & Junic Kim. 2021. Changes and challenges in museum management after the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7(2). 1–18.10.3390/joitmc7020148Suche in Google Scholar

Cunningham, Kelly J. 2019. Functional profiles of online explanatory art texts. Corpora 14(1). 31–62. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2019.0160.Suche in Google Scholar

Dondis, Donis. 2006. La síntesis de la imagen. Introducción al alfabeto visual. Barcelona: Gustavo.Suche in Google Scholar

Fichner-Rathus, Lois. 2014. Foundations of art and design. Boston, MA: Wadsworth.Suche in Google Scholar

Fissi, Silvia, Elena Gori, Alberto Romolini & Marco Contri. 2022. Facing Covid-19: The digitalization path of Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. European Planning Studies 30(4). 573–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1974352.Suche in Google Scholar

Garcia, Noa. 2018. SemArt dataset. Birmingham: Aston University.Suche in Google Scholar

Garcia, Noa & George Vogiatzis. 2018. How to read paintings: Semantic art understanding with multi-modal retrieval. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, German, 8–14 September.10.1007/978-3-030-11012-3_52Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1985. An introduction to functional grammar. London: Arnold.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1994. An introduction to functional grammar. London: Arnold.Suche in Google Scholar

Kotler, Neil & Philip Kotler. 2000. Can museums be all things to all people? Missions, goals, and marketing’s role. Museum Management and Curatorship 18(3). 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0260-4779(00)00040-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther R. & Theo Van Leeuwen. 1996. Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther R. & Theo Van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Hodder Arnold.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther R. & Theo Van Leeuwen. 2021. Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003099857Suche in Google Scholar

Lemke, Jay. 1998. Multiplying meaning: Visual and verbal semiotics in scientific text. In Jim R. Martin & Robert Veel (eds.), Reading science: Critical and functional perspectives on discourse of science, 87–113. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Liao, Min-Hsiu. 2018. Museums and creative industries: The contribution of Translation Studies. Journal of Specialized Translation 29. 45–62.10.26034/cm.jostrans.2018.211Suche in Google Scholar

Liao, Min-Hsiu. 2023. Translation as a practice of resemiotization: A case study of the Opium War Museum. Translation Studies 16(1). 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2022.2103024.Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, Fen & Mike Yao. 2018. The impact of accompanying text on visual processing and hedonic evaluation of art. Empirical Studies of the Arts 36(2). 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276237417719637.Suche in Google Scholar

Maiorani, Arianna. 2020. Kinesemiotics: Modelling how choreographed movement means in space. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429297946Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. & Len Unsworth. 2024. Reading images for knowledge building: Analyzing infographics in school science. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003164586Suche in Google Scholar

Martinec, Radan & Andrew Salway. 2005. A system for image–text relations in new (and old) media. Visual Communication 4(3). 337–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357205055928.Suche in Google Scholar

McMurtrie, Robert J. 2016. The semiotics of movement in space. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315640273Suche in Google Scholar

Miklošević, Željka. 2015. Delivering messages to foreign visitors-interpretative labels in the National Gallery of Slovenia. Solsko Polje 26(5–6). 119–139.Suche in Google Scholar

Moya-Guijarro, Arsenio Jesús. 2019. Textual functions of metonymies in Anthony Browne’s picture books: A multimodal approach. Text & Talk 39(3). 389–413. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2019-2034.Suche in Google Scholar

Nikita, Murzintcev & Nathan Chaney. 2020. R Package “ldatuning.” https://github.com/nikita-moor/ldatuning (accessed 25 May 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

O’Halloran, Kay L. 1999. Towards a systemic functional analysis of multisemiotic mathematics texts. Semiotica 124(1/2). 1–29.10.1515/semi.1999.124.1-2.1Suche in Google Scholar

Painter, Clare, James R. Martin & Len Unsworth. 2013. Reading visual narratives: Image analysis of children’s picture books. Sheffield: Equinox.Suche in Google Scholar

Ravelli, Louise J. 1996. Making language accessible: Successful text writing for museum visitors. Linguistics and Education 8(4). 367–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0898-5898(96)90017-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Ravelli, Louise J. 2006. Museum texts: Communication frameworks. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203964187Suche in Google Scholar

Ravelli, Louise J. & Robert J. McMurtrie. 2016. Multimodality in the built environment: Spatial discourse analysis. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315880037Suche in Google Scholar

Royce, Terry. 1998. Synergy on the page: Exploring intersemiotic complementarity in page-based multimodal text. JASFL Occasional Papers 1(1). 25–50.Suche in Google Scholar

Russell, Phil A. 2003. Effort after meaning and the hedonic value of paintings. British Journal of Psychology 94(1). 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712603762842138.Suche in Google Scholar

Serafini, Frank & Stephaie F. Reid. 2019. Multimodal content analysis: Expanding analytical approaches to content analysis. Visual Communication 22(4). 623–649. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357219864133.Suche in Google Scholar

Serrell, Beverly. 2015. Exhibit labels: An interpretive approach. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.10.5040/9798216405337Suche in Google Scholar

Shang, Guowen. 2020. Expanding the linguistic landscape: Linguistic diversity, multimodality, and the use of space as a semiotic resource. International Journal of Multilingualism 17(4). 552–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1644339.Suche in Google Scholar

Soler Gallego, Silvia. 2019. Defining subjectivity in visual art audio description. Meta 64. 708–733. https://doi.org/10.7202/1070536ar.Suche in Google Scholar

Stauffer, Andrew. 2012. The nineteenth-century archive in the digital age. European Romantic Review 23(3). 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509585.2012.674264.Suche in Google Scholar

Swales, John M. 1990. Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Szarkowska, Agnieszka, Anna Jankowska, Krzysztof Krejtz & Jaroslaw Kowalski. 2016. Open Art: Designing accessible content in a multimedia guide app for visitors with and without sensory impairments. In Anna Matamala & Pilar Orero (eds.), Researching audio description: New approaches, 301–320. London: Palgrave.10.1057/978-1-137-56917-2_16Suche in Google Scholar

Thurstone, Louis L. 1935. Vectors of mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Toh, Weimin. 2018. A multimodal approach to video games and the player experience. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781351184779Suche in Google Scholar

Tyrer, Clare. 2021. The voice, text, and the visual as semiotic companions: An analysis of the materiality and meaning potential of multimodal screen feedback. Education and Information Technologies 26(4). 4241–4260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10455-w.Suche in Google Scholar

Unsworth, Len, Tytler Russell, Lisl Fenwick, Sally Humphrey, Paul Chandler, Michele Herrington & Lam Pham. 2022. Multimodal literacy in school science: Transdisciplinary perspectives on theory, research, and pedagogy. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003150718Suche in Google Scholar

Walker, Francesco, Berno Bucker, Nicola C. Anderson, Daniel Schreij & Jan Theeuwes. 2017. Looking at paintings in the Vincent Van Gogh Museum: Eye movement patterns of children and adults. PloS ONE 12(6). e0178912. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178912.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Ping. 2017. The thematic research of the landscape painting for the five dynasties and song. Hangzhou: China Academy of Art dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Wildfeuer, Janina, Elisabetta Adami, Morten Boeriis, Louise J. Ravelli & Francisco Veloso. 2018. Special issue: Analysing digitized visual culture. Visual Communication 17(3). 271–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357218770584.Suche in Google Scholar

Wu, Xili & Ju Zhan. 2022. Exploring the linguistic landscape of historical and cultural streets: Focusing on the study of shop name signs. Foreign Languages in China 4. 53–61.Suche in Google Scholar

Yap, Joel Qi Hong, Zilmiyah Kamble, Adiran T. H. Kuah & Denis Tolkach. 2024. The impact of digitalization and digitization in museums on memory-making. Current Issues in Tourism 27(16). 2538–2560. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2024.2317912.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- « Référence » et « référent », un essai de mise au point

- Constructed dialogue in signed-to-spoken interpreting: renditions as a reconfiguration of utterance semiotics

- La forme d’existence, un régime sémiotique: acte délictueux et modes de sémiotisation

- Sexualized social and dress codes of girl performers in the West

- Stylistic and semiotic analysis of modern Chinese piano performance

- Earthships as a de-sign process to harmonize with the environment

- Analysis and research on symbolic emptiness in traditional architecture in the Shangri-La Tibetan area

- Exploring text-image relations in museum contexts: a multimodal analysis of sub-genre variations across interpretive captions

- Review Article

- Les avenirs technologiques en sémiotique: retour sur l’année 2024

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- « Référence » et « référent », un essai de mise au point

- Constructed dialogue in signed-to-spoken interpreting: renditions as a reconfiguration of utterance semiotics

- La forme d’existence, un régime sémiotique: acte délictueux et modes de sémiotisation

- Sexualized social and dress codes of girl performers in the West

- Stylistic and semiotic analysis of modern Chinese piano performance

- Earthships as a de-sign process to harmonize with the environment

- Analysis and research on symbolic emptiness in traditional architecture in the Shangri-La Tibetan area

- Exploring text-image relations in museum contexts: a multimodal analysis of sub-genre variations across interpretive captions

- Review Article

- Les avenirs technologiques en sémiotique: retour sur l’année 2024