Abstract

As an intercultural modern art form, web-based ink and wash cartoons are significant tools to communicate cultural identities in the Chinese context because of their entertaining form, thought-provoking content, and profound cultural connotation. Against this background, the present study investigates the multimodal appraisal systems of 96 web-based ink and wash cartoons, focusing on attitudinal meanings and explicating how the attitudinal resources contribute to the communication of Chinese cultural identities. The analysis of 96 web-based ink and wash cartoons shows that the cultural identities of the Chinese dream, Confucianism, collectivism, and optimism are communicated through the interplay between visual and verbal semiotic resources. The analytical results reveal a series of generic features of the web-based ink and wash cartoons that contribute to the promotion of cultural identities, including the popular theme, minimalist style, positive attitude prosody, and the use of culture-specific metaphor and ideation. These features underpin the strategies for promoting Chinese cultural identities and the shift in national branding policy. The study hopes to provide clues for government, social institutions, and individuals to promote cultural identities effectively through social media.

1 Introduction

As multimodal social artefacts, cartoons are employed to communicate a range of themes and social issues because of their condensed form and the rich meaning-making resources of the visual and verbal modalities. The joint effort of visual and verbal semiotic resources in cartoons makes them powerful tools to communicate values and beliefs in social contexts through the use of humor, exaggeration, iconization and symbolization (Dalacosta et al. 2009; Dominguez and Mateu 2014; El-Refaie 2009; Tsakona 2009). Hence, cartoons are widely used in traditional media such as television, newspapers, and magazines, and recently in new media including Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and WeChat (Al-Momani et al. 2017). With the development of new communicative technology, the intercultural sub-genre of cartoons – web-based ink and wash cartoons – is increasingly popular on social media in China because of its entertaining form, thought-provoking content, and profound cultural connotation. It combines traditional Chinese ink and wash painting techniques with the modern cartoon form of manifestation to pursue cultural-specific aesthetic and artistic conception.

In this study, web-based ink and wash cartoons refer to the digitalized ink and wash cartoons that are published on social media. By ink and wash cartoons, we generally refer to the visual art form that combines traditional Chinese ink and wash painting techniques with the modern cartoon form of manifestation, to express humanity and cultural concerns of society, promote Chinese culture, and communicate its cultural identities. The web-based ink and wash cartoons collected for this study were created by Xiaolin. The collected cartoons include both the author’s independent creations and promotional artworks produced in collaboration with the government, which have received an average of over 100,000 views on WeChat and have been widely shared by users. These web-based ink and wash cartoons address a range of social issues and express commonly held cultural identities, attitudes, and values toward these current issues under the guidance of socially determined intentions and ideologies (Stockl 2004). The communicative purpose of web-based ink and wash cartoons contributes to shaping Chinese cultural identities, communicating attitudes and beliefs, and reinforcing cultural-specific ideologies. Therefore, this study approaches web-based ink and wash cartoons as powerful multimodal discourse to promote Chinese cultural identities to the public and the world.

Previous cartoon studies have been conducted from a range of disciplines including education (e.g., Dalacosta et al. 2009; El-Refaie and Horschelmann 2010; Warburton and Saunders 1996), sociology (e.g., Long et al. 2009; Perea 2015, 2018) and linguistics (e.g., Abdel-Raheem 2021; Bounegru and Forceville 2011; Prendergast 2019) and thus vary in focuses and approaches. Research under education studies mainly examines how cartoons are utilized as educational material in the school context to scaffold students’ comprehension of abstract scientific knowledge (e.g., Dalacosta et al. 2009) or access young people’s geopolitical views (e.g., El-Refaie and Horschelmann 2010). Additionally, research in sociology studies investigates cartoons as media for recording social issues and arguments, which focuses on the social agenda depicted in cartoons such as gender issues (e.g., Perea 2015, 2018), and political ideology (e.g., Long et al. 2009).

The studies mentioned above focus on the social function of cartoons, which investigate cartoons at the macro level and explicate how they serve as educational material or media for carrying arguments on social issues. Hence, the semiotic features of the cartoon as multimodal artefacts and how meanings are constructed to realize their social functions and communicative purposes are less discussed.

Alternative to previous cartoon research under educational and sociological approaches, the present study draws on the linguistic approach that views cartoons as multimodal discourse. The linguistic approach complements the studies reviewed above by providing a micro and detailed perspective into the cartoon discourse. By viewing elements in cartoons as semiotic resources, this approach can gain a thorough understanding of the rhetorical features (such as metaphor or satire) that play crucial roles in cartoons and how texts and images interact to form a larger syntax in the meaning-making process under broader social context. Therefore, a linguistic approach to cartoon study is necessary.

Previous linguistic studies of cartoons are mainly conducted from two perspectives, namely, the socio-functional approach and the cognitive approach. Cartoon studies under the socio-functional approach draw on Systemic Functional Linguistics (hereafter SFL) and social semiotics, investigating the meaning-making process of cartoons and how visual and verbal semiotic resources are employed to evaluate political events (e.g., Swain 2012), construct politicians’ identities (e.g., Mazid 2008), resist (un)equal gender relations (e.g., Felicia 2021), represent ideologies of candidates in a political election (e.g., Akpati 2019), and enforce terror and racism (e.g., Jorgensen 2012). Additionally, some research particularly focuses on the rhetorical techniques of cartoons such as humor (e.g., Prendergast 2019) and irony (e.g., Conradie et al. 2012). Other research also examines the generic and cultural variation of cartoons such as Arab political cartoons (e.g., Al-Momani et al. 2017) and Jordanian editorial cartoons (e.g., Al-Masri 2016). Aside from the socio-functional approach, some studies take a cognitive theoretical perspective towards multimodal discourse, exploring how humans construe visual metaphors in cartoons under the guidance of Conceptual Metaphor Theory. Cartoon research in this realm addresses issues of the global financial crisis (e.g., Bounegru and Forceville 2011), Brexit (e.g., Silaski and Durovic 2019), post-election violence (e.g., Wekesa 2012), refugee crisis (e.g., Wawra 2018), international commercial (e.g., Lin et al. 2015), national image promotion (e.g., Zhao and Feng 2017), and racism (e.g., Abdel-Raheem 2021). The above linguistic studies of cartoons as multimodal discourse demystify how cartoons construct meaning in the social context as well as how visual metaphors in cartons are perceived by the human mind. However, these studies mostly focus on the multimodal features of political and editorial cartoons, while the genre of web-based ink and wash cartoons that show considerable generic and cultural variations is an relatively under-examined area.

Therefore, complementing previous linguistic research on political and editorial cartoons, the present study particularly focuses on 96 web-based ink and wash cartoons on social media published in 2020–2021. Drawing upon the socio-functional approach (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014; Kress and van Leeuwen 2021; Martin and White 2005) with a special focus on the attitude system, this study aims to explicate how visual and verbal semiotic resources in cartoons express attitudes (including values and beliefs) and how these attitudes contribute to shaping and promoting Chinese cultural identities. Our research questions include: (1) What attitudes are communicated, and how are they realized through the interplay of visual and verbal semiotic resources? (2) What cultural identities are constructed by attitudinal meanings through the affiliation process under the broader social and political context?

In what follows, this study will first introduce the theoretical foundations of appraisal and affiliation. Then, this study will propose analytical frameworks that model the attitude system and how they contribute to shaping Chinese cultural identities. The collected data will be coded and analyzed according to the proposed framework and the analytical results will be presented and discussed under border social and cultural context.

2 Theoretical foundations

To systemically model attitudinal resources and how they construct cultural identities in web-based ink and wash cartoons, we draw on previous studies using an appraisal and affiliation framework. Hence, in this section, previous research on linguistic appraisal, visual appraisal, and affiliation will be reviewed.

2.1 Attitude in linguistic discourse

The theoretical basis of this study is the appraisal framework developed by Martin and White (2005), which systemically models the language of evaluation within the broader framework of SFL. In SFL, language is viewed as “a complex semiotic system having various levels or strata” involving phonology, lexicogrammar and semantics with each realizing its upper stratum (Halliday and Matthiessen 2004: 24–25). Among these three strata, the semantics plane is where lexicogrammar is transformed into meanings, which also operates as the interface of linguistic structure and broader social context at the discourse level. At the semantic stratum, the linguistic structure simultaneously realizes three meanings, which enables language users to establish social relationships (i.e., interpersonal meaning), to coherently organize their message (i.e., textual meaning), and to construct experience in the real world and logical relationship of clause (i.e., ideational meaning). The appraisal framework is located at the stratum of semantics within interpersonal meanings. It concerns how speakers or writers reveal their feelings and values, express status and authority, and construct “relations of alignment and rapport between them and actual or potential respondents” (Martin and White 2005: 2).

The appraisal framework encompasses evaluative resources of three types: attitude, engagement, and graduation. Attitude concerns resources used to evaluate one’s feelings, including values of emotional reactions (i.e., Affect), social assessment of behaviors (i.e., Judgment), and aesthetic responses to things (i.e., Appreciation; Feng 2012; Martin and White 2005). Among these three axes of attitudinal meanings, affect concerns positive and negative emotional responses, which involve four sub-categories, namely, un/happiness, in/security, dis/satisfaction, and dis/inclination. Judgement deals with “resources for assessing behavior” based on social principles from two dimensions: social sanction and social esteem (Martin and White 2005: 35). Judgement of social esteem encompasses normality (how special one is), capacity (how capable one is), and tenacity (how dependable, determined, and resolute one is) while sub-categories within social sanction are veracity (how honest one is) and propriety (how ethical one is). Additionally, appreciation concerns the evaluation of the aesthetic features of objects and entities in terms of reaction (the impact and quality of things), composition (the balance and complexity of things), and valuation (the worth and value of things).

The three axes of attitudinal meaning are realized across a range of lexicogrammatical resources (Hood 2004; Martin and White 2005). In terms of the realization strategies of attitudinal meaning, appraisal theory distinguishes between attitudes that are directly inscribed and indirectly invoked. Inscribe refers to the attitude that is explicitly expressed by attitudinal lexis (Martin and White 2005). Invoke means that attitude is implicitly constructed by lexical grammar, graduation, or ideational resources. Under the category of invoked attitude, provoke refers to the attitude expressed by idiom (e.g., one of a kind) or lexical metaphor (e.g., giant of history) while invite encompasses the attitude that is flagged or afforded. A flagged attitude could be constructed by interjections (e.g., wow), swearing (e.g., hell of a guy) or graduation resources (e.g., 1000s attended the service). Towards the most implicit end of the framework, afford refers to the case where only ideational resources are used to afford evaluation. Martin (2020) further refines the framework by identifying two sub-categories of afforded attitude, distinguishing between relatively neutral (e.g., attend the match) and iconized (e.g., don a Springboks jersey) expressions of attitude. In this framework, the degree of implicitness increases down the scale from inscribing toward affording. That is, “the further down the scale we go, the more interpretation depends on reading position” (Martin 2020: 21) and the less in “aligning with the values naturalized by the text” (Martin and White 2005: 67).

Except for attitude, the appraisal framework of Martin and White (2005) also identifies the categories of engagement and graduation. Engagement accommodates meaning-making recourses that “position the speaker/writer with respect to the value position being advanced and the potential response to that value position” while graduation concerns the adjustment of the degree of an evaluation (Martin and White 2005: 35–36). In this study, we mainly focus on the attitude dimension of appraisal. Since web-based ink and wash cartoons originate from traditional Chinese literati paintings, they inherit the core communicative purposes of literati paintings – that the art creation serves the propagation of philosophy, value stances, and attitudes (Fang 2003). Hence, web-based ink and wash cartoons could be expected to encompass rich attitudinal resources, which are constantly combined with ideational meanings in the cartoons to form the [interpersonal + ideational] social bonds and operate as the primary unit of the affiliation process that constructs cultural identities (further discussed in Section 2.3). Therefore, the analysis of attitudinal meanings and their coupling with ideational meanings can unveil the social bonds communicated in the cartoons and how they contribute to the affiliation of cultural identities from the pole of persona to culture. For this reason, the analysis in the present study mainly focuses on the attitude system among the three axes of appraisal.

This linguistic appraisal framework introduced in this section extends the realm of interpersonal meaning by systemically modelling the language of evaluation under the perspective of attitude, engagement, and graduation, which is applicable in analyzing the values and beliefs explicitly or implicitly constructed in discourse. Hence, this framework is exploited as an analytical tool in a range of empirical research. Their research targets range from literacy pedagogy (e.g., Humphrey et al. 2011, 2012), academic writing (e.g., Hood and Zhang 2020), advertisement, and news, to legal discourse. These studies provide rich instantiations of how the meaning-making resources of appraisal are used in linguistic discourse under social context. However, in modern communication tools such as social media, web news, online advertisements and digital magazines, appraisal meanings are communicated not only by language but also by the integration of different semiotic resources, including verbal language, image, sound, hyperlink, video, and so forth. Therefore, “the study of linguistic discourse alone has theoretical limitations” which might overlook some significant nature of multimodal-constituted evaluative messages (O’Halloran 2007: 79). Premising on this assumption, we need to consider both linguistic and other semiotic resources in the construction and interpretation of evaluative meanings. Therefore, there is a shift of research interest in the realm of appraisal studies from linguistic discourse toward multimodal discourse.

2.2 Attitude in multimodal discourse

Similar to linguistic discourse, attitudinal meanings can also be expressed by the joint effort of different semiotic resources such as visual images, visual narratives, video, gestures, and soundtrack in multimodal discourse. These semiotic resources in the social context which “evolve to serve similar purposes become streamlined for those purposes” (Bateman 2014: 186). Hence, although verbal and visual semiotic resources are different in materiality at the lower levels of descriptive abstraction, they might exhibit parallels at more abstract levels of discourse when they interact to serve the same communicative purpose in the same social context (Bateman 2014: 186). That is, at the higher level of abstraction, the linguistic appraisal framework seems reasonable and insightful enough to be analogized to describing the evaluative system in other semiotic resources. Hence, previous studies of appraisal in multimodal discourse employ the linguistic appraisal framework of Martin and White (2005) to describe the attitude system realized by semiotic resources other than linguistics (e.g., Economou 2009; Feng and O’Halloran 2013).

Among these studies, particularly relevant to the present research are Economou’s (2009, 2012 studies, which analogize linguistic appraisal framework to visual attitude systems in images with a focus on the evaluative strategies in news photos. According to Economou (2009), visual images provide rich meaning-making resources for realizing all three dimensions of attitudinal meaning in linguistic texts, namely, affect, judgment, and appreciation. These attitudinal meanings could be directly inscribed by the “depiction of embodied attitude” such as facial expression and body gesture, or they could be indirectly evoked by visual ideational metaphor (provoke), visual graduation (flag), and visual ideational token (afford; Economou 2009: 109).

Based on Economou’s (2009) research, Unsworth (2015) refines this visual appraisal framework by proposing two sub-categories of visual evoke. Unsworth (2015) distinguishes between the directed and invited attitude. Specifically, the directed attitude refers to the expressions that are designed to direct the audience to some evaluative stance rather than invite them, by using the semiotic resources of visual and verbal metaphors and comparison. The directed attitude can be further distinguished into the attitude that is entailed and provoked. Entailed attitude refers to the kind of metaphor (especially visual metaphor) that is designed to direct the audience to some evaluation and thus it is much closer to the inscription on the cline. Provoke attitude refers to visual comparison and verbal metaphors, which are less compulsory for evaluation. The studies of Economou (2009, 2012 and Unsworth (2015) analogize the entire linguistic attitude framework of Martin and White (2005) to visual appraisal, which provides an applicable framework to investigate how attitudinal meaning is constructed in visual images and is examined in empirical research in several publications (Economou 2006, 2008, 2012; Swain 2012).

Moreover, the studies introduced above all agree that facial expressions are among the most significant and simultaneous semiotic resources that represent emotion and express attitudinal meaning visually. To model facial expression, Feng and O’Halloran (2012) investigate how emotions are systemically realized by the combination of facial areas based on the early research of Ekman and Friesen (1978), Martinec (2001), and McCloud (2006). Feng and O’Halloran (2012) distinguish four main facial areas including the forehead, eyebrow, eyes, and lower face. They are “simultaneous entries” of the facial expression system and “obligatory members of the face” (Feng and O’Halloran 2012: 2071). According to this framework, the forehead encompasses horizontal wrinkles, vertical wrinkles, and no wrinkles. Eyebrows encompass the whole brow (raised or lowered) and inner corners of the eyebrow (raised, down, or drawn together). The eyes could be wide opened, narrowed, or closed. The lower face consists of the nose, cheeks, and mouth. The nose could be wrinkled or not while the cheek could be raised or not. The mouth could be tensed or relaxed, corners up or corners down.

The study of Feng and O’Halloran (2012) looks deeply into the semiotics resources of facial expressions that encode emotion and visual attitudinal meanings. They provide applicable and effective frameworks for systemically modelling the choices being made in communicating attitudinal meaning multimodally, which are the significant theoretical foundations of the present study. Hence, these frameworks are adapted and refined in the present study to illustrate how visual and verbal semiotic resources in cartoons interact to express attitudes (including values and beliefs) and how these attitudes contribute to shaping and promoting Chinese cultural identities.

2.3 Attitude and cultural identity

The linguistic and visual analytical frameworks of attitude, which reveal the writer/speakers’ position and value stance in discourse, are linked to identity studies in previous research. For example, Oteiza and Merino (2012) used linguistic appraisal frameworks to explicate how attitudinal meanings contribute to the construction of ethnic identities in Mapuche adolescents. Moreover, previous research in this realm employs appraisal theory to analyze identity construction in a range of genres such as TV programs (e.g., Xu and White 2021), tourist discourse (e.g., Etaywe and Zappavigna 2021), and American plays (e.g., Alsanafi and Noor 2019). These empirical studies focus on the discursive construction of individual identities, which provides a linguistic perspective of identity studies through appraisal analysis.

Except for individual identities, it is argued that appraisal analysis could also shed light on the construction of communal and cultural identities through the affiliation process (Knight 2010; Martin 2008a, 2008b; Stenglin 2004). The concept of affiliation is paired with individuation, which is a relatively new aspect of SFL (Martin 2009). Individuation focuses on how an individual may demonstrate varying degrees of the assessment of “the linguistic resources of culture” (Knight 2010: 36). This relates to the concept of the cultural reservoir (“the set of strategies and their analogic potential possessed by any one individual”) and individual repertoire (“the total of sets and its potential of the community as a whole”) proposed by Bernstein (2000 [1996]: 158).

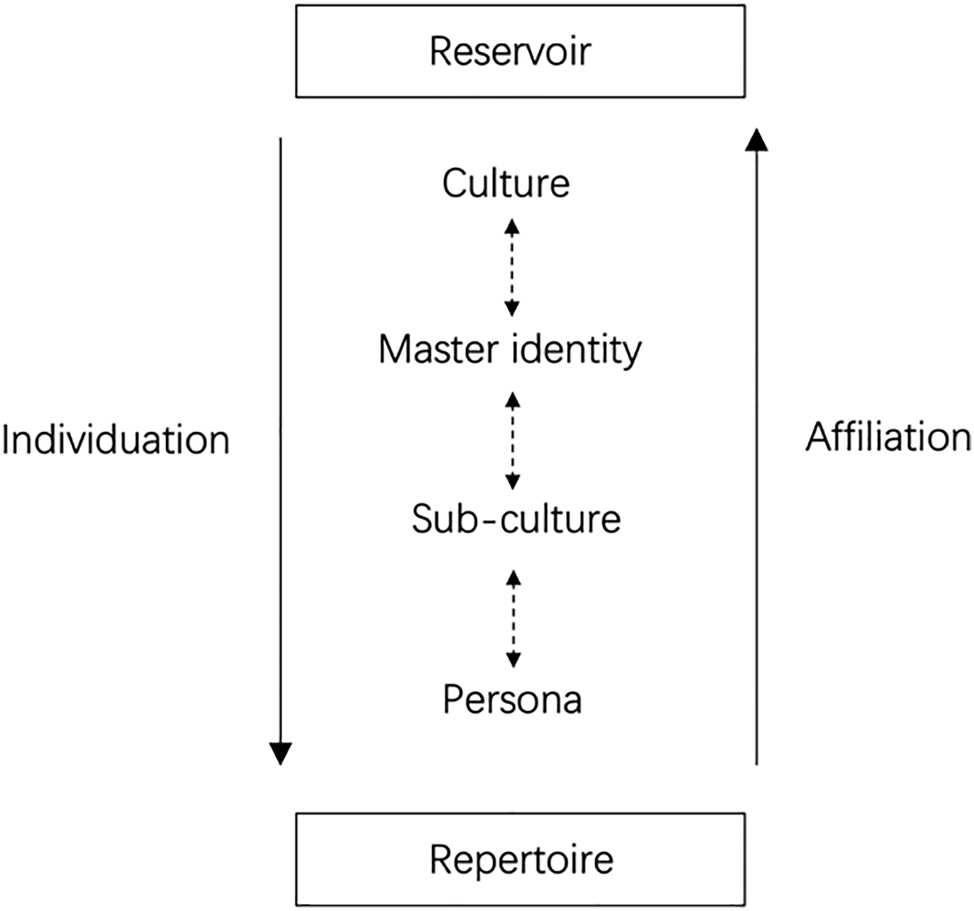

Based on Bernstein’s (2000 [1996]) research, Matthiessen (2007) relates the notion of the reservoir to the system pole and the repertoire to the instance pole. However, Martin (2008a) takes a different view of the relationship between reservoir–repertoire and system–instance, by defining individuation as a parallel cline that is detached from instantiation and realization. According to Martin (2008a: 36), the individuation (reservoir–repertoire) cline “complements and must be read in relation” to the hierarchies of instantiation cline (see Figure 1).

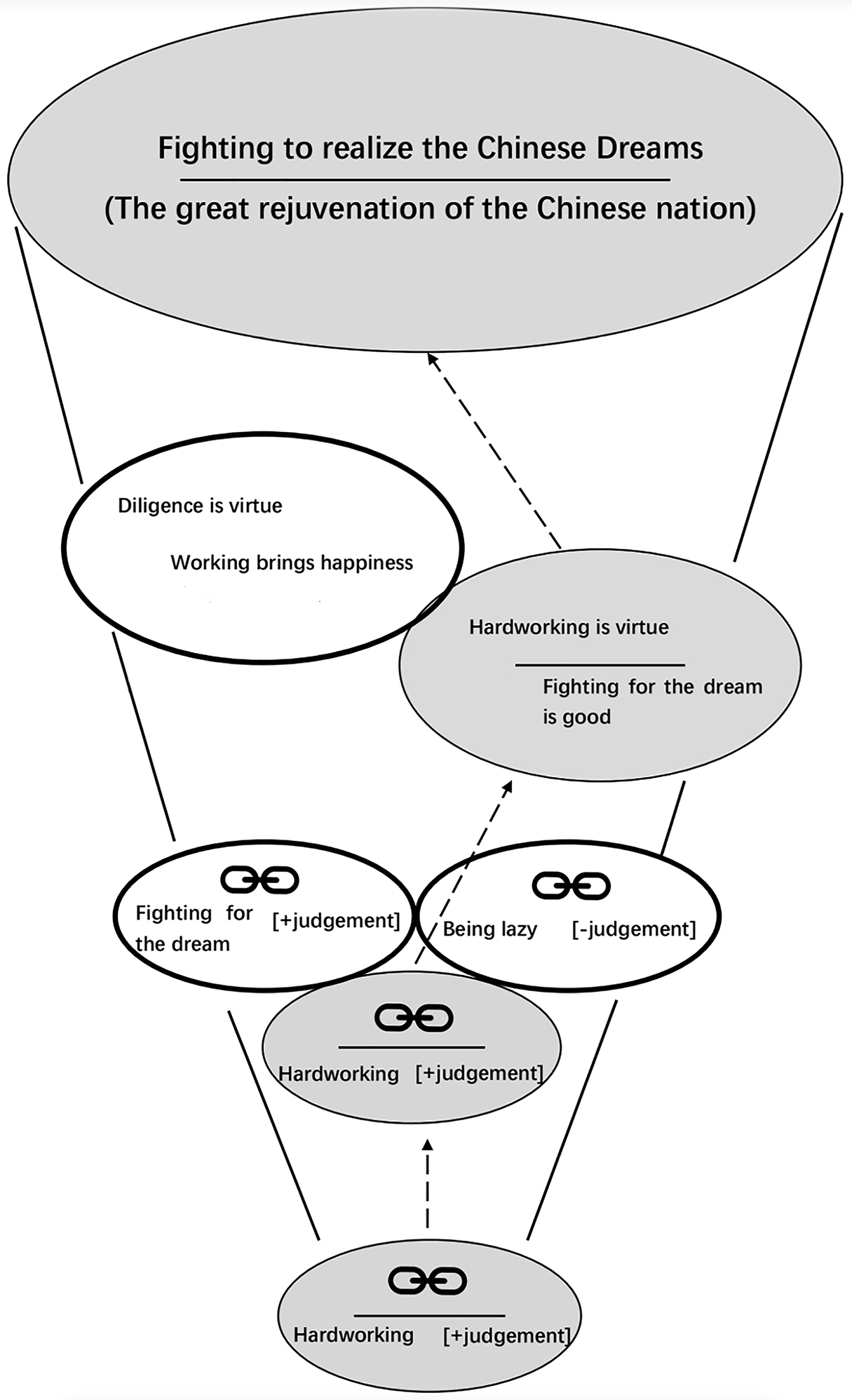

The cline of individuation and affiliation (Martin 2010: 24).

As demonstrated in Figure 1, there are two directions of the individuation and affiliation cline: top-down and bottom-up. First, along the top-down cline of individuation, one can observe “a culture dividing into smaller and smaller communities as we move from the community as whole, through master identities (generation, gender, class, ethnicity, dis/ability) and sub-cultures to the personas that compose individual members” (Martin 2010: 24). On the other hand, through the bottom-up affiliation cline, one can “conceive of persona aligning themselves into sub-cultures, configuring master identities and constituting a culture” (Martin 2010: 24). That is, the process of affiliation could construe how individuals affiliate into the culture of communities and how the social persona co-identifies through the negotiation of shared meaning and values. Therefore, the affiliation in this perspective provides insight into the ongoing semiotic construction of communal identities. That is, through the investigation of the affiliation process in texts, it is possible to uncover the cultural identities discursively negotiated in discourse.

To interpret the affiliation process in the text (in terms of how it builds up cultural identities and what cultural identities are negotiated), one needs to investigate the instantiation and logogenesis in discourse (Knight 2010; Martin 2008a, 2008b, 2010). This involves the study of the emerging constrained meaning potential in the form of culture and how these meanings are combined (Martin 2008b: 44). The combined meanings in discourse are described by Martin (2008b) as the logogenetic pattern of the manifestation of coupling. The coupling is “the way in which meanings combine, as pairs, triplets, quadruplets, or any number of coordinated choices from system networks” (Martin 2008b: 39). By investigating the logogenetic forming of coupling, one can identify how discourse participants construct affiliative identities and establish themselves within communities.

Specifically, the attitudinal meanings that are combined with ideational tokens in web-based ink and wash cartoons could inform us about the values and evaluative stances that are shared and negotiated multimodally and how these values are aligned around participants. Stenglin (2004) defines these interpersonal and ideational couplings as “bonding,” which “brings participants together into communities in which they can align around shared values, and thus impacting upon the communal identities” (Knight 2010: 40). That is, the cultural communal identity is discursively negotiated and shared through the social bonds in discourse and these bonds “make up the value sets of our communities and culture” (Knight 2010: 42). Notably, these value sets are not stable and fixed. In contrast, it is dynamic and negotiable through different coupling in the unfolding of discourse. In this perspective, affiliation could be defined as the theory of discursively negotiated communal identity (Knight 2010). Therefore, through investigating these dynamic social bonds in discourse, it is possible to uncover the shared value sets and cultural patterns negotiated, which discursively construct communal cultural identities.

Based on this assumption, Knight (2010: 44) proposes a cline of relations in affiliation to “visualize how interactants may negotiate bonds in affiliation by representing the elements constructed by speakers as relation on a cline.” This framework demonstrates how bonds formulate bond networks and more abstract networks to ideology and finally form a cultural system of bonds. This framework is adapted in this article to develop a framework that is capable of revealing the Chinese cultural identities and how they are communicated in the web-based ink and wash cartoons. The above arguments provide the rationale for investigating cultural identities through appraisal analysis. Accordingly, the couplings of attitudinal and ideational meanings will be analyzed to explicate what and how the cultural identities of China are constructed and communicated in web-based ink and wash cartoons.

Additionally, by cultural identities, we refer to the sense of belonging to the shared value and communal identities of a specific group of people to a specific culture (Li 2022). Based on Giddens’ (2001) research, we approach cultural identities from two broad perspectives: cultural beliefs and cultural values. Cultural beliefs refer to the most essential elements of a culture that are consensual, shared, and communicated by social members. The influence of such beliefs is so significant that they might form the fundamental living contexts of social members (Giddens 2001). The other category – cultural values – defines the standard of human behavior, involving the consensual criteria of what should be the priority, and what is ethical, valuable, and important (Giddens 2001).

3 Towards the social semiotic system of cultural identity

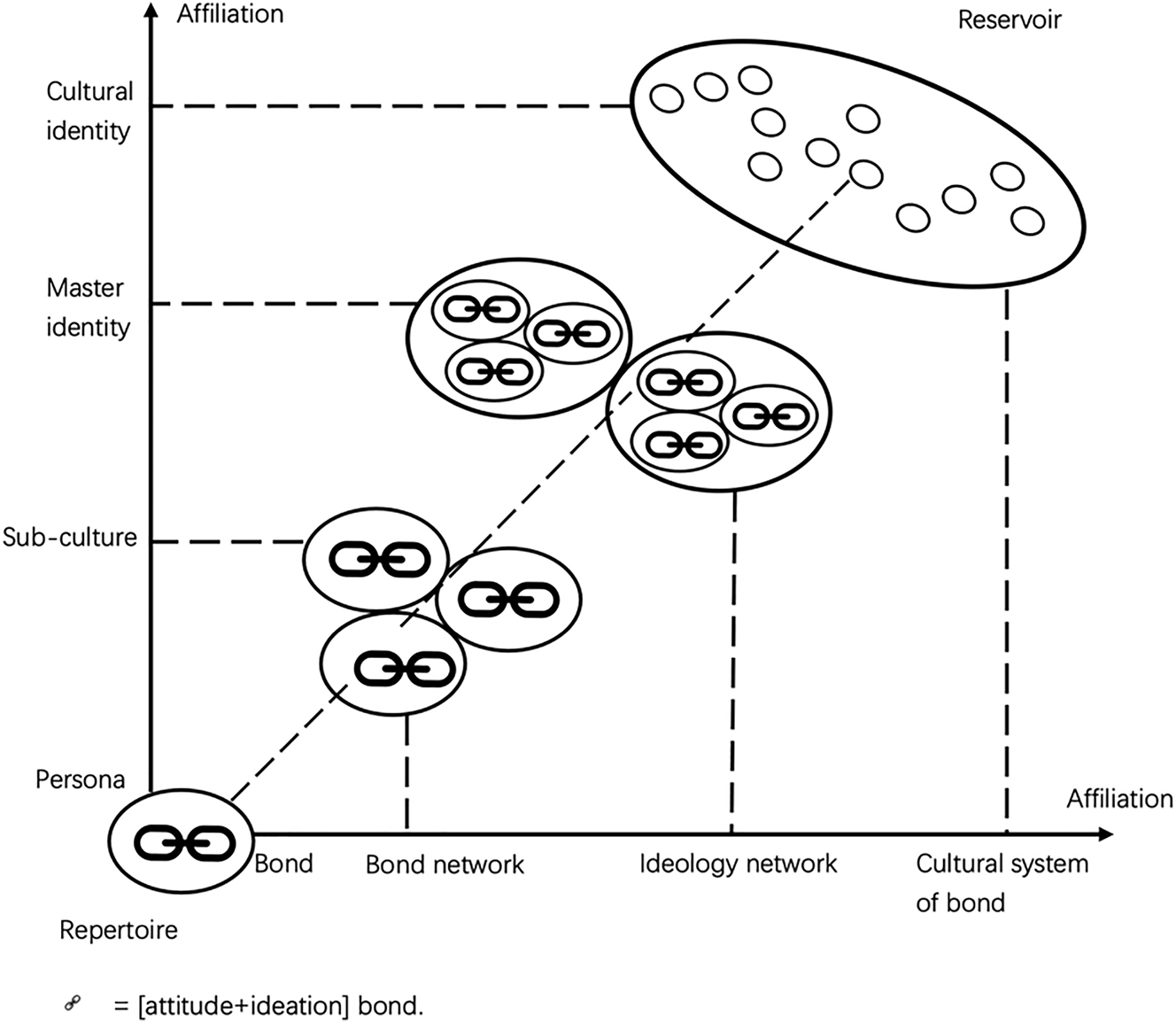

The analysis of cultural identities draws upon the theory of affiliation and individuation (Knight 2010; Martin 2008a, 2008b, 2010). The cultural identities are the aggregation and abstraction of the social bonds that are realized by a range of semiotic resources under the social contexts. The schema of the construction of cultural identities through the affiliation process is demonstrated in Figure 2.

The construction of cultural identities through the affiliation process (adapted from Knight 2010).

As shown in Figure 2, cultural identities could be negotiated at various levels of generality and abstraction. First, the construction of cultural identities begins with the communication of bonds. The bond is the entry and the minimal unit in the framework, which is realized by the couplings in the cartoons (especially the coupling of interpersonal values and ideational experience in nature). Second, the bond in Figure 2 is then clustered into bond networks, which is realized by a cluster of bond communities that share similar value sets from persona to sub-culture. Then, the value sets further generalize into the master ideological network that represents the master identities of the community. Finally, the master identities are gathered to form the cultural system of the bonds (i.e., cultural identities), which is the shared value set acknowledged by all members of the community.

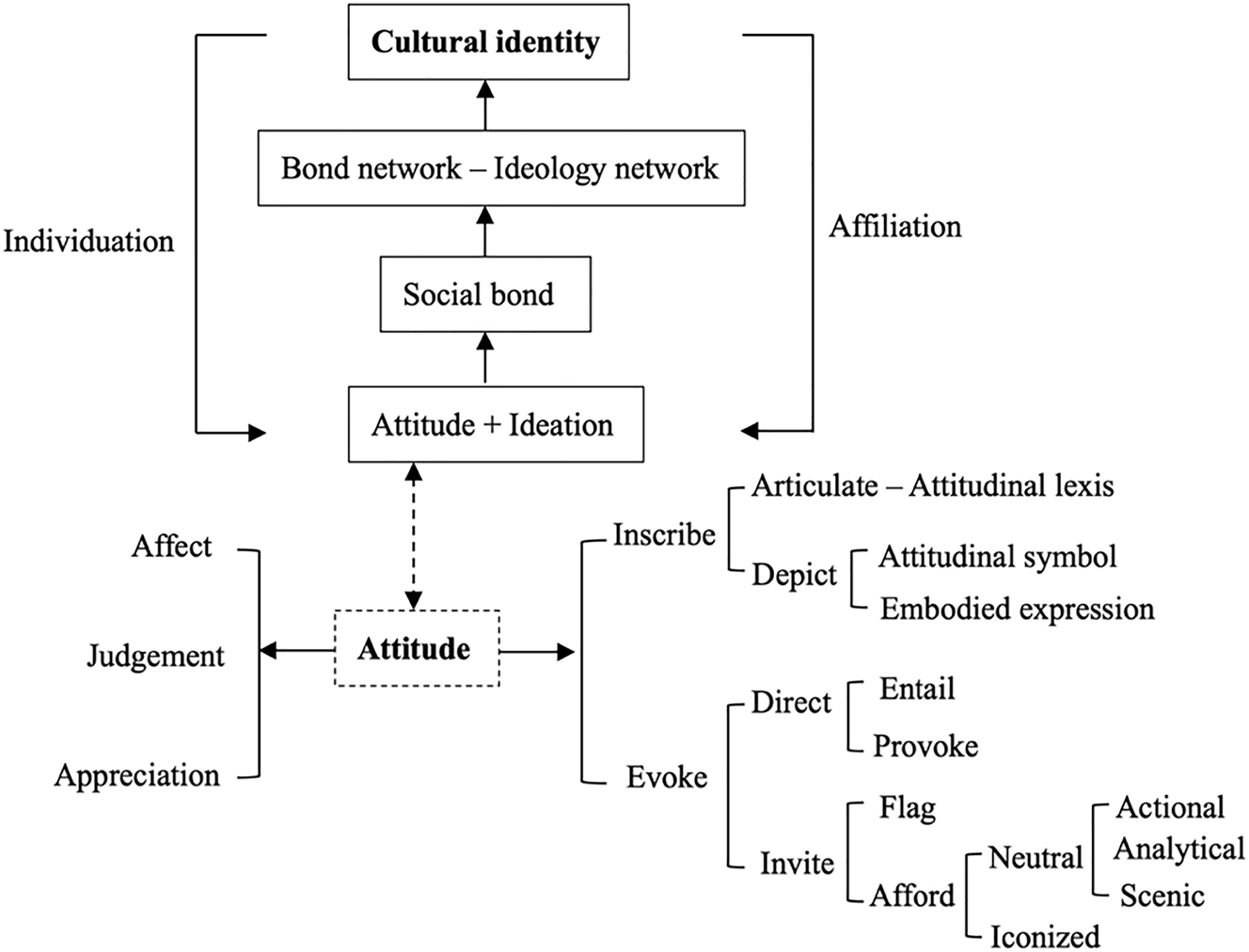

Based on this schema of the affiliation process, we propose an overall analytical framework to model how cultural identities are discursively and multimodally constructed in web-based ink and wash cartoons (see Figure 3).

The overall analytical framework.

As demonstrated in Figure 3, the framework is centered on the identification of social bonds, which are clustered into bond networks and create bond communities of shared value and ideology. These ideology networks then affiliate into cultural identity from persona to culture. Hence, the analysis of the social bond negotiated in web-based ink and wash cartoons is essential to the demystification of cultural identities.

To interpret the social bonds, one needs to investigate the instantiation and the logogenetic pattern of coupling in discourse (Knight 2010; Martin 2008a, 2008b, 2010). The coupling is “the way in which meanings combine, as pairs, triplets, quadruplets, or any number of coordinated choices from system networks” (Martin 2008b: 39). Specifically, in web-based ink and wash cartoons, attitudinal meanings, which convey values and evaluative stances, are combined with ideational meanings. These [attitude + ideation] couplings could inform us about the shared value and how they are aligned around participants. Stenglin (2004) defines these attitudes and ideational couplings as bonding, which “brings participants together into communities in which they can align around shared values, and thus impacting upon the communal identities” (Knight 2010: 40). That is, [attitude + ideation] coupling could be seen as a social bond that could be shared and negotiated in discourse. Hence, in the overall analytical framework (see Figure 3), social bonds are realized through the couplings of [attitude + ideation], which forms the basis of the construction of cultural identities. Since these social bonds are centered on attitudinal meanings, a detailed analysis of the attitude system is necessary to explicate how cultural identities are constructed through the complex signifying process in web-based ink and wash cartoons.

As shown in Figure 3, a multimodal attitude framework is proposed as the basis of the affiliation process, based on the studies of Economou (2009), Martin and White (2005), and Unsworth (2015). The attitude network on the left shows the attitude system and the one on the right demonstrates its realization strategies.

According to the analytical framework, the multimodal attitude operates under three dimensions as proposed by Martin and White (2005): affect, judgement, and appreciation. In terms of the realization strategies of multimodal attitude, this study distinguishes between attitudes that are multimodally inscribed and evoked. Inscribe refers to the most explicit and direct realization of attitude while evoke refers to the implicit and indirect realization of attitude. In the framework, the implicitness and the freedom of interpretation increase from up to down. The further down the pole, the interpretation of attitudinal meaning increasingly depends on the reader and the social and cultural context.

Under inscribe, the attitude could be verbally articulated or visually depicted. The articulated attitude is realized by the attitudinal lexis in the cartoons such as 开心 ‘happy’ and 欢喜 ‘joyful’. This extremely explicit expression of attitude “leaves the reader no freedom of interpretation” by aligning the reader directly with the values communicated by the multimodal discourse (Economou 2009: 108). The depicted attitude is realized visually by attitudinal symbols and embodied expressions. The attitudinal symbol refers to images that are inherently attitudinal such as the symbol of thumps up. The embodied expression refers to the facial expressions that inscribe attitude (for example, a smile might inscribe positive attitudes while a frown might inscribe negative attitudes) and bodily behavior and gestures which are associated with basic emotions (e.g., laughing and crying). For facial expressions, the attitudinal meanings might be expressed by the combination of the eyebrows, eyes, and mouth or by a single facial area.

The depiction of facial expressions shows the characteristic of the minimalist drawing style, which uses lines, curves, circles, and dots to form the facial parts. This minimalist style of web-based ink and wash cartoons originates from traditional Chinese literati paintings, which use basic lines to depict the form of characters and objects (Chen 2011; Zhang 2022). This convention and aesthetics require artists to emphasize the abstraction of essential features and the inner spirit of an object rather than imitate its form (Zhang 2022). Notably, it is not a simplification of drawing but an intended choice by the artist to remove irrelevant content in order to highlight the meaningful component (Chen 2011). Therefore, the representation of facial expressions in web-based ink and wash cartoons is extremely simplified compared to political and editorial cartoons. It is more generalized and rarely points to specific individuals in life. Such depiction is more schematic and minimalist, and it has conventional patterns to represent certain affect. For example, the emotion of [+happiness] is represented by four facial combinations (see Table 1). The minimalist realization of facial expressions is more similar to the pole of emoji than photos. Hence, they can only distinguish basic categories of emotions but cannot convey more nuanced emotional changes.

The facial combinations.

| Facial combinations | Schemas |

|---|---|

| [eyes: closed], [eyes: corners down] |

|

| [eyes: closed], [eyes: corners down], [mouth: opened], [mouth: corners up] |

|

| [eyebrows: lowered], [eyes: closed], [eyes: corners down], [mouth: opened], [mouth: corners up] |

|

| [eyebrows: lowered], [eyes: closed], [eyes: corners down], [mouth: closed], [mouth: corners up] |

|

An example of the depiction of [+happiness] is demonstrated in Table 2(a). The participant is depicted with a pair of narrowed eyebrows, a pair of narrowed eyes, and a wide-opened, corners-up mouth, which together form the facial expression of “laughing.” This facial combination is a typical realization of the inscribed [+happiness].

Examples of inscribed attitude (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/A8-tZ2_TyIBOIQHrEc-M8Q).

| Attitudes | [+happiness] | [−happiness] |

|---|---|---|

| Examples |  (a) |

(b) |

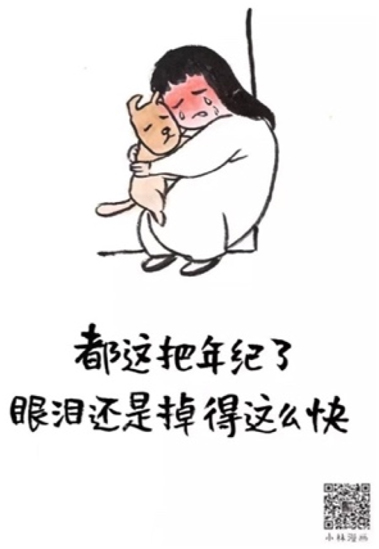

| Translations | My three rules for happiness: Not necessary; Never mind; Nothing is a big deal. |

Even at this age, tears still fall so quickly |

Moreover, the embodied facial expression can inscribe attitudinal meaning on its own but in some cases, it could also be accompanied by embodied behaviors or gestures. For example, in Table 2(b), the facial expression is depicted as “crying” and this is accompanied by forwarded and crouched body gestures to enhance the inscribed attitude of [−happiness]. Different from actions that afford attitude, embodied behavior only inscribes attitude accompanying facial expressions.

Under evoke, the framework distinguishes between directed attitude and invited attitude. First, the directed attitude is originally proposed by Unsworth (2015) to model the visual judgment in picture books. In this study, it is adapted as an aspect of multimodal attitude since similar instances are also observed in web-based ink and wash cartoons. In these cartoons, some expressions are designed to direct the audience to some evaluative stance rather than invite them, by using the semiotic resources of visual and verbal metaphors and comparisons. The directed attitude can be further distinguished into the attitude that is entailed and provoked. Following Unsworth (2015), entailed attitude refers to the kind of metaphor (especially visual metaphor) that is designed to direct the audience to some evaluation and thus it is much closer to the inscription on the cline. In this case, it is somehow impossible for the audience to avoid making certain evaluations that are directed by visual metaphors (Unsworth 2015). Hence, the image entails the attitude rather than provoking it. In the entailed image, visual metaphors of specific characters or objects are linked to some incongruous participants and objects and these incongruous elements force the audience to construe the visually depicted metaphor. The entailed visual metaphors might be represented by exaggeration and caricature. This is not exclusive to web-based ink and wash cartoons, but it is a common characteristic of all cartoons. In Unsworth’s (2015) analysis of picture books, similar features are also identified. Notably, in web-based ink and wash cartoons, the entailed image might contain some culture-specific metaphors that are realized by metaphorical symbols and imagery. This visual and verbal symbolic imagery essentially encompasses metaphorical meanings which are widely recognized in the Chinese cultural context.

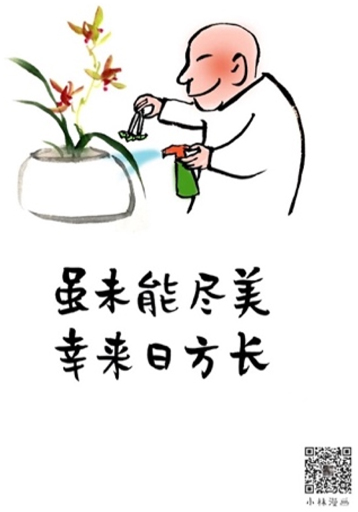

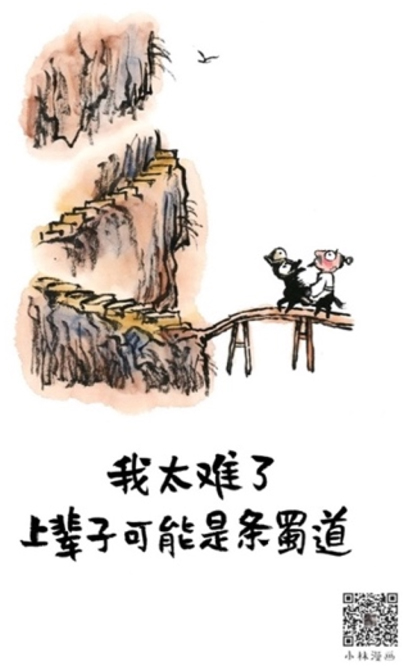

For example, Table 3(a) depicts the visual imagery of an orchid, which is the metaphor for virtue, noble, and elegance in the Chinese context. The depiction of a man who loves orchids is a common metaphor for a man who is well-educated and in high reputation. Moreover, the visual imagery of high mountains and precipitous cliffs is another metaphorical symbol that refers to the difficulties in one’s life. For instance, in Table 3(b), one of the most precipitous mountains in China – Mount Shu – is presented. Mount Shu is located in the Sichuan Province of China, which is famous for its precipitous and treacherous road. Therefore, Mount Shu in this cartoon is the multimodal metaphor for the difficulties that the character encountered in life.

Examples of directed attitude (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/A8-tZ2_TyIBOIQHrEc-M8Q).

| Attitudes | [Direct: entail] | [Direct: entail], [Direct: provoke] |

|---|---|---|

| Examples |  (a) |

(b) |

| Translations | Although it is not perfect, fortunately, there is still a long time ahead | I am having a tough time Maybe in my past life, I was a road in Sichuan |

These culture-specific metaphors mainly originate from famous traditional poems, classics, literature, and idioms of China and are widely used in literature and art throughout history. Hence, the metaphorical meanings and the attitudinal stances are entailed in the imagery, which directs the audience to make certain evaluations. These cultural-specific metaphors are frequently observed in the data and thus contribute to the generic features of the web-based ink and wash cartoons. However, for the audience without a Chinese cultural background, the interpretation of the metaphorical imagery could be difficult since they can hardly link the metaphorical imagery to the congruent one. Moreover, the provoked attitude refers to the verbal metaphor and visual comparison that does not force the viewer to make evaluations in construct with entailed attitude.

Second, under the category of invitation, the attitude could be flagged by visual and verbal graduation resources or afforded by visual and verbal ideational resources that are relatively neutral or iconised (Martin 2020). The neutral affordance includes the verbal and visual expression of actional processes (e.g., running, eating, etc.) and the analytical processes that portray statical participants (e.g., the procession, dressing style or appearance). Moreover, the attitude could also be neutrally afforded by the depiction of scenic elements such as background circumstances.

Notably, the attitude afforded by visual ideational tokens is suggested to be a more powerful evaluative tool than verbal afford. It depends less on the context and background knowledge and is more compulsory to attitude estimation than verbal affordance (Economou 2009). This can be explained by the features of visual semiotic resources that are able to simultaneously provide multiple ideational tokens in one cartoon panel, which probably involve great attitudinal evaluation depending less on the social and cultural context. For example, the participants in cartoons might be depicted in particular hairstyles, cloth, accessories, and age groups, which could afford certain attributes of the participants while at the same time, they might also engage in some actions that are able to afford attitudinal evaluation.

It is suggested that these visual ideational tokens add or contribute to other options such as inscribed or directed attitudes in news photos (Economou 2009) and similar instances are also observed in web-based ink and wash cartoons. On the one hand, the visual ideational tokens might additionally provide more detailed information about the participants, which could shape the attribute and social group of the character in cartoons. For instance, the participant might be depicted as a well-known person or a normal citizen, politician, or scholar. These ideational affordances might strengthen or weaken some attitudes inscribed, directed, or flagged by other semiotic resources in the same cartoons. On the other hand, the depiction of background elements could also contribute to other attitudes in the cartoons by adding environmental ideation, atmosphere light or colors, etc. These background ideations in our data show unique cultural and general variations compared with other cartoon genres in both the selection of ideational objects and the manner of presentation, which shapes the features of the web-based ink and wash cartoons.

The extremely implicit realization of attitude is iconization, which deals with the iconized ideation meaning in the form of a symbol. It is “a comparable condensation process as far as interpersonal meaning is concerned – a process whereby ideation accrues value” (Martin 2021). In the process of iconization, the everyday meaning of an event or entity is backgrounded and its axiological significance to the members of a group is foregrounded (Martin 2021). The interpretation of such iconized attitude relies highly on the cultural background and context.

Notably, the semiotic resources that realize the attitudinal meanings are afforded by a peculiar graphic representation of traditional Chinese brushstrokes. Similar to traditional Chinese paintings, the brushstrokes of web-based ink and wash cartoons share their origins with Chinese calligraphy, exhibiting profound similarities in terms of brushwork techniques and the portrayal of lines and compositions (Fang 2003; Wang 2023). These brushstrokes are designated as markers of Chinese culture and they serve as the materiality of the semiotic practice, which provides affordance for the signifying process (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021). Hence, the social semiotics (and the attitude) afforded by such cultural-specific materiality might be naturally linked to the value stances, ideologies, and communal identities of the specific culture. The brushstrokes of web-based ink and wash cartoons rely on the signifier materials of the surface of production (Chinese art paper), the substances of production (ink and water), and the tools of production (calligraphy brush pen; Kress and van Leeuwen 2021). The variation of these signifier materials can represent the visual effects of density, lightness, dryness, wetness, angularity, roundness, finesse, clumsiness, heaviness, and swiftness brushstrokes (Zhang 2023). These variations in brushstrokes reflect the artist’s drawing style and enable the attitude expressions. For instance, the brushstrokes of density, dryness, angularity, heaviness, and swiftness are used to portray relatively tough environments such as rugged mountains, which add an underlying meaning within the proposed framework by contributing to the expression of positive judgment toward the person who is robust enough to survive the hazardous environments.

To summarize, the proposed analytical framework (see Figure 3) models how cultural identities are constructed discursively in web-based ink and wash cartoons through an affiliation process by utilizing the visual and verbal semiotic resources and their interplay. In the framework, the affiliation process begins with the identification of attitudinal meanings and how it is coupled with ideations to form social bonds. The identification of the cluster of social bonds that make up the value sets of culture in higher generality is expected to provide significant insight into the construction of Chinese cultural identities under the social context. Hence, the proposed framework is employed to analyze the cultural identity communicated in 96 web-based ink and wash cartoons and the analytical results will be presented in the next section.

4 Data analysis: the construction of Chinese cultural identities in web-based ink and wash cartoons

In this study, we collected a dataset of 96 web-based ink and wash cartoons published online during 2020–2021, and concerning a wide range of issues. The data were coded and analyzed according to the frameworks proposed in Section 3. The analysis identifies a clear set of cultural identities under the two broad categories following Giddens’ (2001) classification of culture, which is constricted through the affiliation process from bonds to bond networks and the value sets that mark the identities of Chinese culture. The overall distribution of these cultural identities and their requency in the data is shown in Table 4.

The analytical results of cultural identity.

| Culture identities | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture beliefs | Confucianism | 17 | |

| Chinese Dream | Fighting for the dream | 28 | |

| The pursuit of a better life | 25 | ||

| Culture values | Collectivism | 18 | |

| Optimism | 45 | ||

-

The cultural identities of the Chinese Dream (53), Confucianism (17), Collectivism (18), and optimism (45) are identified with a total number of 133. Since one cartoon might communicate more than one cultural identity, the total number of cultural identities exceeds that of the cartoons.

4.1 Chinese Dream

First, the most dominant cultural identity constructed by the social bonds in web-based ink and wash cartoons is the Chinese Dream, which takes up more than 50 % of the total results. The concept of the Chinese Dream was proposed in 2012 by the chairman of China, as one of the most important guiding ideologies for the Chinese government. It refers to the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, which involves building China into a well-off society in an all-around way (Liu 2022). It concerns the public’s pursuit of a better life, more income, and a well-developed social security system.

In the current social context, it is believed that the main contradiction of contemporary Chinese society lies between the public’s pursuit of a better life (both physical and mental) and the unbalanced and insufficient development of society. Hence, from this perspective, the Chinese Dream could be construed as including two aspects. The first one is the public’s pursuit of a better life (both physical and mental) and the second is the hard work to realize a better life (and the balanced and sufficient development of the whole society). Both these two aspects are observed in our data, constructed by homologous but slightly different social bonds and bond networks (see Table 5).

The bonds and bond networks of the Chinese Dream.

| Cultural identities | Bond networks | Bonds | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Dream | The pursuit of a better life | Working brings happiness | Happiness is good; Wealth is good; |

[(+appreciation: valuation) + (wealth/procession/environment …)] [(+appreciation: reaction) + (wealth/procession/environment …)] |

| Fighting for the Dream | Diligence is virtue; Hardworking is virtue; Fighting for the dream is right; |

[(+judgement) + (hardworking)] [(+judgement) + (fighting for the dream)] [(−judgement) + (being lazy)] |

||

As demonstrated in Table 5, the two aspects of the Chinese Dream are realized by different social bonds and bond networks and joined together at the level of the ideology network to form master identities. These master identities then affiliate into the cultural identity of the Chinese Dream.

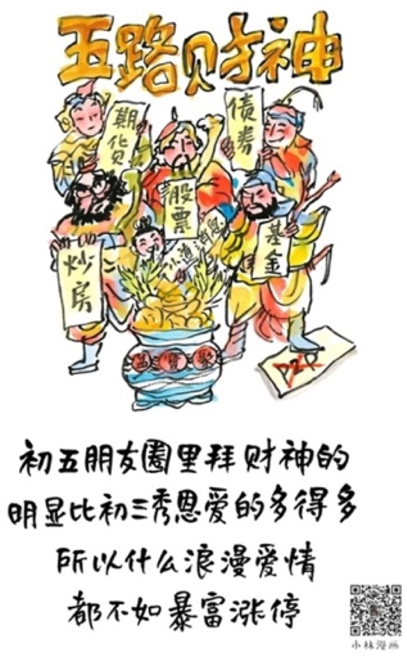

Specifically, as shown in Table 5, the pursuit of a better life is realized by the social bonds of [(+appreciation: valuation) + (wealth/procession/environment…)] and [(+appreciation: reaction) + (wealth/procession/environment…)]. The pursuit of a better life contains both the material level (such as wealth, procession, living environment, working environment, etc.) and the mental level (such as mental health, entertainment, education, art, etc.). For example, in Table 6(a), the pursuit of wealth growth is observed. This cartoon depicts the five gods of wealth in the ancient myth of China. In traditional Chinese culture, people worship the god of wealth once a year on January 5th of the lunar calendar. The five gods in the cartoon each hold a paper that writes different financial assets (i.e., futures, stock, bonds, funds, and houses). The appreciation of [+valuation] is visually afforded through the analytical process of presenting the five gods and the actional process of holding up the financial assets. Additionally, the [+reaction] towards the written financial asset is also inscribed by the facial expression of smiling and laughing. The verbal texts on the bottom also add to this prosody of [+appreciation] by describing the experience of people worshipping the god of wealth on January 5th. That is, the financial assets are evaluated as valuable and wanted through visual and verbal affordance and inscription.

Examples of Chinese Dream – the pursuit of a better life (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/A8-tZ2_TyIBOIQHrEc-M8Q).

| Cultural identities | Chinese Dream: the pursuit of wealth | Chinese Dream: the pursuit of a better natural environment |

|---|---|---|

| Examples |  (a) |

(b) |

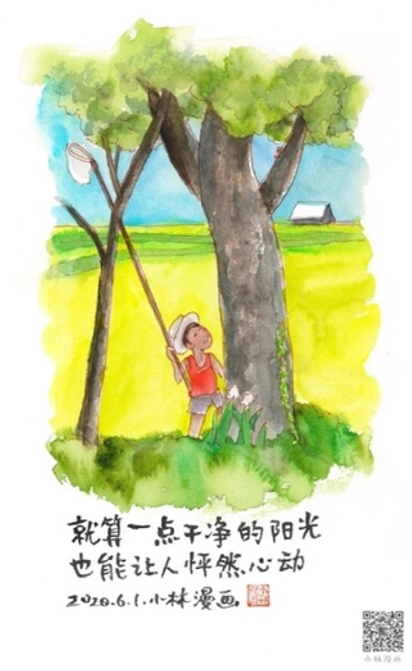

| Translations | On the fifth day of the Lunar New Year, there were clearly more posts in my social media circle about worshipping the God of Wealth than there were on the third day about showing affection with loved ones. So, getting rich quick and making a fortune seem to be more desirable than romantic love. (Annotation: the third day of Lunar New Year is Feb. 14th, which is the Valentine’s Day) | Even a little bit of clean sunlight, can make one’s heart beat with delight |

Moreover, in Table 6(b), the pursuit of a better natural environment is observed. In this example, the [+appreciation: reaction] towards the sunlight, blue sky, and green plants is visually inscribed through the facial expression (smiling) of the character. The verbal inscription of [+complexity] and [+reaction] (which is realized by the attitudinal lexis of 干净的 ‘pure’ and 怦然心动 ‘flipped’ added to this value stance), which together develop the prosody of positive appreciation towards the pleasant natural environment. In these two cartoons, the attitude of [+appreciation] is constantly coupled with the ideation of materiality for a better life such as wealth and a good living environment. These [attitude + ideation] bonds (together with a set of similar social bonds in other cartoons) found the value set of bond networks in the affiliation process. These bond networks further affiliate into the master identity of the pursuit of a better life, which then constructs the cultural identity of the first aspect of the Chinese Dream.

Second, another aspect of the Chinese Dream constructed in the data is the hard work to realize a better life and the development of society. A general schema of how this aspect of the Chinese Dream is constructed through social bonds is demonstrated in Figure 4.

The realization of the cultural identities of the Chinese Dream.

As shown in Table 5 and Figure 4, the second aspect of the Chinese Dream is mainly realized by the social bonds of [(+judgement) + (hardworking)], [(+judgement) + (fighting for the dream)], and [(−judgement) + (being lazy)]. That is, in the web-based ink and wash cartoons, the ideational experience of hardworking is frequently coupled with positive judgement and affect while the experience of being lazy is criticised.

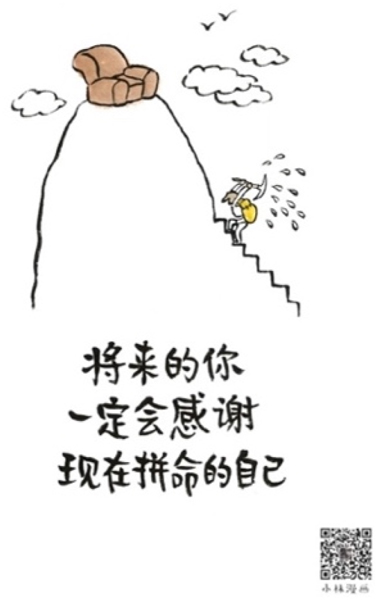

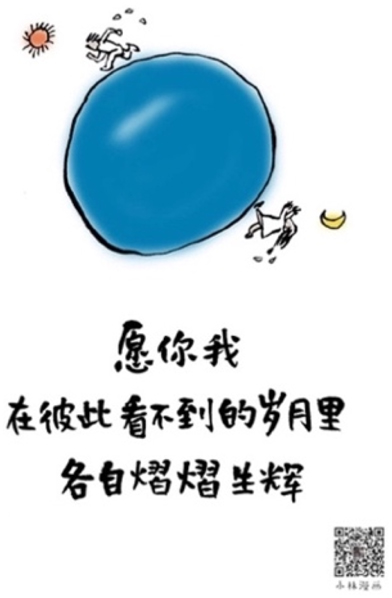

For example, in Table 7(a), a character stands on a precipitous mountain and creates the stairs on the mountain with a hammer. The exaggerated depiction of the “sweat drops” emphasizes the hard work of the character. As mentioned above, the symbol of mountains in the Chinese context is a commonly used metaphor for difficulties in life. Therefore, the depiction of a man climbing the mountain could be construed as a visual metaphor for someone working hard to overcome difficulties and the armchair on the top of the mountain is a metaphor for the realization of one’s dream. These metaphors entail the attitude of positive judgement towards the character and this attitude is enhanced by the verbal semiotic resources of 拼命 ‘working hard’, which afford positive judgment.

Examples of the Chinese Dream: hardworking (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/A8-tZ2_TyIBOIQHrEc-M8Q).

| Cultural identities | Chinese Dream: Hardworking | Chinese Dream: Fight for the Dream |

|---|---|---|

| Examples |  (a) |

(b) |

| Translations | In the future, you will definitely be grateful for the hardworking self of today | May you and I shine brilliantly in the years that we cannot see each other |

Moreover, in Table 7(b), the metaphor of light (or glowing) also entails positive judgements. The light metaphor in the Chinese cultural context is used to conceptualize people who are successful or someone with high capability, virtue, or reputation. In Table 7(b), the metaphor 熠熠生辉 ‘something is glowing’ entails the positive capacity (to be successful) of the two characters depicted in the cartoon. In these examples, the participants in the cartoons are all depicted as working hard and these ideational experiences are constantly coupled with positive judgement as social bonds that construct cultural identities.

4.2 Confucianism

Confucianism refers to the philosophical system of Confucius and Mencius, which is the core of traditional Chinese culture since it has dominated the idealistic realm of China for more than 2000 years and its basic notions still influence modern Chinese society (Shen 2004). The analytical results show that two essential concepts of Confucianism – harmony and benevolence – are constructed in the data. The social bonds and bond networks that construct Confucianism are demonstrated in Table 8.

The bonds and bond networks of Confucianism.

| Cultural identities | Bond networks | Bonds | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confucianism | Harmony | Harmony is beautiful; Harmony is virtue; Harmony brings happiness; |

[(+affect: happiness) + (being harmonious)] [(+judgement) + (being harmonious)] [(+appreciation) + (being harmonious)] |

| Benevolence | Benevolence is virtue; Benevolence is gracious; Benevolence brings happiness; |

[(+affect) + (be kind to/helping/loving others)] [(+judgement) + (be kind to/helping/loving others)] |

|

First, the concept of harmony emphasizes the balance between nature, society, and the individual, pursuing unity between opposites. As demonstrated in Table 8, this is construed by the couplings of [(+affect: happiness) + (being harmonious)] and [(+judgement) + (being harmonious)].

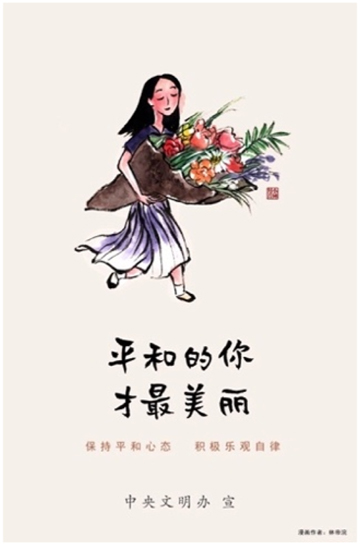

For example, Table 9(a) depicts an elegant female character with a peaceful smile and balanced body shape. This gentle and peaceful image affords [+appreciation] through the visual analytical process of the female character. The facial expression of the female character inscribes a positive attitude of [+affect] while the attitudinal lexis 最美 ‘the most beautiful’ inscribes [+appreciation] toward the female character who is depicted as gentle, peaceful, and harmonious. That is, the shared value of pursuing a peaceful and harmonious emotion, appearance, and lifestyle is appreciated in this cartoon. Moreover, in the data, this social bond of [(+appreciation) + (harmonious objects)] is constantly observed, which constructs the cultural identity of harmony.

Examples of Confucianism (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/A8-tZ2_TyIBOIQHrEc-M8Q).

| Cultural identities | Harmony | Benevolence | Benevolence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examples |  (a) |

(b) |

(c) |

| Translations | You are the most beautiful when you are at peace | With a kind heart, you will surely encounter angels on your journey | When you help others remove stumbling blocks, you are also paving the way for yourself |

Moreover, the other concept – benevolence – deals with the moral criteria of interpersonal relationships, which refers to the love between social members, especially between strangers. This Confucianism concept is mainly constructed by the coupling of [(+affect) + (be kind to/helping/loving others)] and [(+judgement) + (be kind to/helping/loving others)].

For instance, Table 9(b) depicts two young passengers helping the elder. Their behaviors are evaluated as [+judgement: properties] by inscribed lexis 善意 ‘kindness’ and the provoked metaphor 天使 ‘Angel’. At the same time, the positive emotions of all three characters are constructed by facial expressions. The above attitudinal and ideational couplings align the audience with the shared value of benevolence that helping the elder is the proper and ethical thing to do and this behavior will bring happiness to the people involved. In another example (see Table 9[c]), one person is paving the way for a stranger. The attitude of [+judgement] is afforded through the actional process of the participant who holding a huge stone. In the above examples, the social bond of [(+judgement) + (helping others)] is communicated and clustered into the bond network and together constructs the cultural identity of benevolence through the affiliation process.

4.3 Collectivism

The cultural value of Collectivism refers to the socialist value that collective benefits should be prior to individual benefits when the two are in conflict (Huang 2021). The social bonds and bond networks that construct Collectivism are demonstrated in Table 10.

The bonds and bond networks of collectivism.

| Cultural identities | Bond networks | Bonds |

|---|---|---|

| Collectivism | Collective benefit is prior | [(+judgement) + (personal sacrificing for the common good)] |

For example, in Table 11, the medical staff give up their safety and happiness to fight against the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2021. The [+judgement] is constructed by a series of actions they make such as 通宵 ‘staying up all night’, 冷饭 ‘eating cold rice’, and 委屈 ‘grievances’. This personal satisfaction for the benefit of the common good is parsed and it is evaluated as appropriate, valuable, and ethical. In this example, the social bond of [(+judgement) + (personal scarifying for the common good of the society)] is observed, which affiliates into the cultural identity of Collectivism.

Examples of Collectivism (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/A8-tZ2_TyIBOIQHrEc-M8Q).

| Cultural identity | Collectivism |

|---|---|

| Example |

|

| Translations | The overnight shifts doctors endure, the cold meals they eat, and the grievances they suffer will eventually be transformed into the best thing people desire: health |

4.4 Optimism

The cultural value of optimism grows deep in Chinese culture, which refers to the attitude when people face difficulties, frustration, and sorrow. Hence, it is not surprising that it is communicated in our data with a percentage of 34 %. The social bonds and bond networks that construct optimism is demonstrated in Table 12.

The bonds and bond networks of optimism.

| Cultural identities | Bond networks | Bonds |

|---|---|---|

| Optimism | Difficulties is normal; frustration makes one stronger; failure is the mother of success; |

[(+affect) + (negative events)] |

For example, in Table 13(a), the participant is injured but still laughing. The [+affect] is inscribed visually through facial expression and verbally through the attitudinal lexis 快活 ‘joy’. In Table 13(b), the boy gets wet in the rain but still being happy. In these examples, the [+affect] is constantly coupled with [unlucky events/difficulties in life]. This counter-expectancy of the bad scenarios and the positive attitude highlights the optimistic spirit of the character.

Examples of optimism (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/A8-tZ2_TyIBOIQHrEc-M8Q).

| Cultural identities | Optimism | Optimism |

|---|---|---|

| Examples |  (a) |

(b) |

| Translations | We have all been bruised and battered, but at this moment, we should be joyful | There are no truly happy people in this world. Only those who have a mindset unfurled |

5 Discussion: cultural identities and contemporary China

The analysis in Section 4 suggests that web-based ink and wash cartoons construct a series of cultural identities of China including the Chinese Dream, Confucianism, collectivism, and optimism. These cultural identities are realized through the visual and verbal semiotic resources that are constantly coupled with similar ideational meanings to form the network of social bonds. In this section, the analytical results will be discussed in relation to the context.

In SFL, context is defined as “the total environment in which a text unfolds” (Halliday 1978: 5), which includes the stratum of “context of situation” and “context of culture.” The context of situation is explored under field (authorial activity and the domain of the activity), tenor (the participants of the activity and their relations), and mode (channel of communication). The context of culture concerns the overall social and cultural background, which explains the reasons why certain field, tenor, and mode are chosen as situational variations (Feng 2019). This includes the identification of “socio-cultural events and phenomena” and “abstract values and ideology” behind the culture (Feng 2019: 68). Hence, the analytical results of this study will be discussed first at the level of context of situation. Then, the situational choices and generic features of the web-based ink and wash cartoons will be accounted for at the level of context of culture concerning broader socio-cultural background.

First, the field examines authorial activity, the purposes of creating the discourse, and the domain of the activity (i.e., the subject matter and topics; Feng 2019; Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). The author of the web-based ink and wash cartoons is a folk artist who uploads digital cartoons and other artworks on social media. This authorship reveals a change in the object of promoting cultural identities from political leaders and official media to individual and self-media. Moreover, the purposes of the web-based ink and wash cartoons are mainly to entertain and persuade, which differs from the previous official promoting discourse that aims at providing information and instructions. The subject matter of the cartoons closely relates to the everyday life of the public (such as education and carrier development) rather than focusing on political and economic issues. This marks the changes in the strategies and practices for promoting cultural identities from top-down to bottom-up.

Second, the tenor is discussed in terms of the relationship between participants (author and viewer) and the values they imbued. The author and target viewers of the web-based ink and wash cartoons are all civilians and ordinary users of social media. Different from promoting cultural identities through official media, the power relations between the author and the viewers in web-based ink and wash cartoons are relatively equal. Additionally, the values communicated in the cartoons are mainly positive. That is, there are more positive attitudes than negative ones and the promoted cultural identities are mainly positive.

Third, the mode concerns the channel of communication, which is further distinguished between the medium and the genre of communication (Feng 2019). The web-based ink and wash cartoon is a relatively new genre used to promote cultural identities, which distinguishes it from previous promotion discourse such as news, governmental reports, and official documentaries. Moreover, the medium that affords the web-based ink and wash cartoons is one of the largest social media in China and its technology affordance shapes the generic features of the cartoons. It is argued that social media provide unique affordance including visibility, editability, persistence, and association (Treem and Lenardi 2013). In social media such as WeChat, massage is instant and portable, which changes rapidly in the information flow. Hence, different from other cartoon genres, the image of web-based ink and wash cartoons are relatively simple with the emphasis on one or two main subjects that are designed to catch the viewer’s attention. Meanwhile, the texts of the cartoons are short and easy to comprehend, which lowers the time cost of the viewer to interpret them. Moreover, the theme of web-based ink and wash cartoons closely relates to the hotspot of society in order to gain more attention from the viewer.

These situational variations of the web-based ink and wash cartoons are shaped by the broader socio-cultural context of contemporary China. First, although China has changed rapidly in the past decade, the national images of China in the coverage of the international media are relatively negative and unfavorable (Peng 2004; Xiang 2013; Yu and Wu 2018). This situation forces the Chinese government to promote positive national images and identities for the further economic development of the country. Hence, the Chinese government has put forward a series of policy and national branding projects aiming to develop and promote a positive national image worldwide (Alvaro 2015; Hu and Ji 2012). In the process of national branding, the development and promotion of cultural identities play an essential role. Therefore, in web-based ink and wash cartoons, the cultural identities being constructed are generally positive, which shows the profound cultural connotation, excellent national spirit, and moral, ethical, and reliable national images. According to the analytical results in Section 4, the cultural beliefs and values that guide Chinese people are constructed, which shape Chinese cultural identities as harmonious and peace-loving rather than threatening and offensive; humanitarian and selfless rather than evil and selfish; hardworking and enterprising (creating wealth and realize their dream with hard work) rather than lazy. Moreover, the characteristic of Chinese people and the spirit of the nation are communicated as optimistic, who never give up and stop trying even in the worst scenario.

Second, apart from promoting cultural identities internationally, the Chinese government also highlights the significance of strengthening the cultural identity among Chinese people to unite the people, increase a sense of belonging, inherit national culture, develop the national spirit, and maintain national sovereignty. The government proposes that in recent years, the focus of the society shifts from the political perspective (forging a sense of community in the Chinese nation) and the economic perspective (building a moderately prosperous society) to the cultural perspective (strengthening the cultural identities of the Chinese nation; Ma and Fang 2021). Under such a context, the cultural identities constructed in web-based ink and wash cartoons comprise both traditional and contemporary cultural symbols. The integration of traditional and contemporary culture links the current ideology of China to the widely recognized and accepted cultural symbols (such as Confucianism) to enhance the sense of belonging of Chinese people. Moreover, another strategy is to evoke shared attitudes (mostly affect) of the viewers in the process of constructing cultural identities. In some cartoons, some visual and verbal semiotic resources are designed to engage viewers’ emotion by manipulating viewers’ expectancy, sympathy or empathy and thus evokes the shared attitudes of the audience. Different from official promoting discourse, in web-based ink and wash cartoons, the viewers are put on equal status with the author and the participants in cartoons. These participants are not power holders such as political leaders, government speakers, or news commentators. They are depicted as ordinary people and someone that experience similar things as the viewers. Therefore, in these instances, the viewers are more easily to share similar attitudes with the participant in cartoons, which might increase the willingness of the viewer to like the cartoon posts on social media or repost the cartoon on personal homepages. This contributes to the rapid dimension of these cartoons on social media.

Third, although various media forms have been developed to promote Chinese cultural identities, the branding policy has been criticized for exploiting only official media, which could be government-centered and thus lack persuasiveness. Hence, in recent years, there is a shift from the governmental media to other social institutions and self-media in national branding practice. The web-based ink and wash cartoons are created by a folk artist and posted on the self-media homepage of WeChat. Hence, cultural identities are not constructed directly and explicitly as in official promoting posters but in a relatively implicit and popularized way to meet the public’s preferences, reading habits, and entertainment needs. As a result, the theme of web-based ink and wash cartoons does not directly relate to current news, political issues, government policy, national images, and identities. Inversely, it focuses on the everyday life of the audience and highlights its entertainment purposes by creating houmous. For example, to construct the cultural identity of the Chinese Dream, the cartoons do not mention the connotation of the Chinese Dream or identify it as a governmental policy and ideology. It focuses on the realization of personal dreams with the social bonds of [(+judgement) + (hardworking)] and [(+judgement) + (fighting for the dream)]. These bonds cluster into bond networks, for example, “hardworking brings miracles”; “hardworking increases social esteem”; “realizing the dream is excellent,” etc. Therefore, the analytical results reveal a shift in promoting cultural identities from exploiting official media to social institutions and independent media and a shift from explicit promotion to relatively implicit branding.

6 Conclusions

To conclude, the present study provides new insights into the attitude system of web-based ink and wash cartoons and how these attitudes affiliate into a series of Chinese cultural identities. Drawing on the SFL and appraisal framework, an analytical framework is proposed and applicated in the analysis of 96 web-based ink and wash cartoons on social media. The analysis identifies the cultural identities of the Chinese dream, Confucianism, collectivism, and optimism.

The analytical results reveal a series of generic features of the web-based ink and wash cartoons compared with other cartoon genres. First, the drawing style of web-based ink and wash cartoons is minimalist with simple images, short texts, and plain backgrounds. Additionally, the theme of the cartoons is based on the experience of daily life and focuses more on cultural and philosophical perspectives rather than political issues. Second, the attitudinal meanings communicated in the web-based ink and wash cartoons that construct cultural identities also show unique features. Overall, the attitudes communicated in the web-based ink and wash cartoons are mainly positive and most of the attitudes are realized indirectly. In terms of the embodied inscription, the facial expression of the participant is rather schematic and iconic and thus is less ambiguous and easy to comprehend, compared with the drawing style of political cartoons. In terms of the evoked attitude, the metaphors that entail or provoke attitude are mainly culture-specific, which depend more on cultural background and social context. Moreover, the web-based ink and wash cartoons exploit ideational resources frequently to afford other attitude expressions, represent cultural imagery, and provide circumstance information. According to these analytical results, web-based ink and wash cartoons differ from other cartoon genres in that they entail rich cultural connotations such as cultural-specific metaphors, and symbolic ideation tokens. Therefore, they are effective in the dissemination of cultural identities within the domestic context. However, since they are increasingly used for promoting cultural identities internationally, it might be difficult for audience without Chinese cultural backgrounds to understand such cultural-specific representations. Therefore, it is suggested that some annotations could be added to the artwork (or on the web pages) to facilitate audience with diverse cultural backgrounds.

Moreover, the results also provide new understandings about China in terms of how the cultural identities (which form curial parts of national images) are promoted in the national branding process. The results show that cultural identities are promoted as the combination of traditional Chinese culture and contemporary Chinese culture and these identities are relatively positive. They are communicated not only to its citizen but also to people in other countries who are interested in Chinese culture. Based on the analysis, the study identified some shifts in promotion strategies: (1) the change in the object of promoting cultural identities (from official media to individual media); (2) the change in relations between the author and audience (from unequal to equal); (3) the shift in purposes of the promoting discourse (from instruction to entertainment); (4) the shift in the way of promoting cultural identities (from explicit to implicit, from top-down to bottom-up).

Despite its small sample size, the present study extends the research domains of socio-functional multimodal studies into the genre of web-based ink and wash cartoons and provides social semiotic frameworks for systemically describing the multimodal attitude system and its realization. The analytical frameworks proposed in this study can be applied to analysing the multimodal discourse of different genres and the discursive construction of identities of countries and communities. Moreover, it is hoped that the analytical results of this study provide clues for media companies, institutions, and governments to promote their cultural identities effectively through social media. Further studies in this regard can enlarge the data size and utilize quantitative corpus tools to gain more objective results.

References

Abdel-Raheem, Ahmed. 2021. Multimodal metaphor and (im)politeness in political cartoons: Sociocognitive approach. Journal of Pragmatics 185. 54–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.08.006.Search in Google Scholar

Akpati, Chibuzor Franklin. 2019. A multimodal discourse study of some online campaign cartoons of Nigeria’s 2015 presidential election. IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities 6(2). 69–80. https://doi.org/10.22492/ijah.6.2.07.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Masri, Hanada. 2016. Jordanian editorial cartoons: A multimodal approach to the cartoons of Emad Hajjaj. Language & Communication 50. 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2016.09.005.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Momani, Kawakib, Muhammad A. Badarneh & Fathi Migdadi. 2017. A semiotic analysis of political cartoons in Jordan in light of the Arab Spring. Humor 30(1). 63–95. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2016-0033.Search in Google Scholar

Alsanafi, Ismael Hasan & Siti Noor Fazelah Binti Mohd Noor. 2019. Development of black feminine identity in two postmodern American plays through appraisal framework: Comparative study. Revista Amazonia Investiga 8(21). 104–116.Search in Google Scholar

Alvaro, Joseph James. 2015. Analyzing China’s English-language media. World English 34(2). 260–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12137.Search in Google Scholar

Bateman, John A. 2014. Text and image: A critical introduction to the visual/verbal divide. Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9781315773971Search in Google Scholar