Abstract

The stigma attached to any criminal record, including for those found not guilty, can lead to reduced job prospects and economic hardship long after judicial proceedings conclude. This paper examines discriminatory behavior of experimental participants who are given the opportunity to base an investment or employment decision on their trustee’s/worker’s criminal record. Similar to the real world, our experiment shows that employers and investors discriminate against those with criminal convictions. Surprisingly, we find they also discriminate against those with acquittals. We find that a subject’s reciprocity corresponds significantly to the true guilt or innocence of an accused, but not to conviction or acquittal of a crime. Because reciprocator behavior does not depend on a person’s criminal record, no rational basis exists for the observed statistical discrimination against those who have been accused. Our results raise serious concerns about the practice of using criminal records in hiring, as convictions are often poor indicators of actual culpability.

Funding source: Charles Koch Foundation

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and appreciate funding from the Charles Koch Foundation. We also thank, for helpful comments and suggestions, seminar and workshop participants from Vienna University, Wichita State University, Whitman College, the 3rd Behavioral and Experimental Public Choice Workshop, the 2019 Regional Mont Pelerin Society Meetings, and the 2024 Public Choice Meetings.

A1: Glossary of Terms

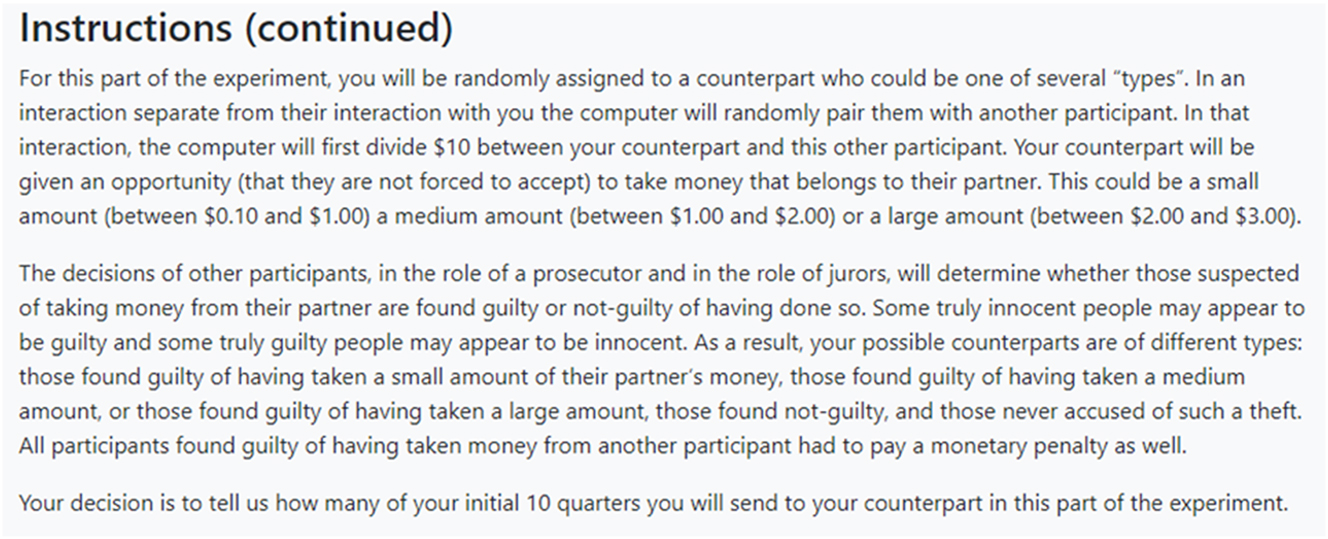

Criminal Justice (CJ) System – A series of games consisting of the Theft game, Prosecutor and Defendant plea bargaining games, and the juror trial task. True innocence/guilt and CJ status of a defendant are both determined at different points in the CJ system.

Crime – If a potential defendant took money from their partners in the theft game.

Truly Innocent – If a potential defendant did not take money from their partner in the theft game.

Truly Guilty – If a potential defendant did take money from their partner if the theft game.

Never Accused – If a defendant proceeded through the CJ system and were not accused of committing a crime or the prosecutor dropped the defendant’s case.

Acquitted – If a defendant proceeded through the CJ system and were accused of a crime, but not found guilty.

Found Guilty – If a defendant proceeded through the CJ system and were accused of a crime and were either found guilty at trial or plead guilty to the crime.

Bias – If employers/investors allocated more money to one group of employees/trustees than another group.

Trust – If an investor invests money in their trustee. Greater trust is indicated by larger investments.

Trustworthiness – If trustees return money to their investors. More trustworthiness is associated with higher rates of return.

Equity – If the total amount of money in a game is split evenly between investor and trustee (employer and employee). Allocations close to an even split are said to be more equitable.

A2: Description of Criminal Justice Status for Strategy Method from the Trust Game (Gift Exchange is Similar)

A3: Counterfactual Payoffs

We include full counterfactual payoff tables for investors in the trust game and employers in the gift exchange game. Table A1 reports potential payoffs that could have been earned from partners with different criminal justice statuses in the trust game. Table A2 reports potential payoffs that could have been earned from partners with different criminal justice statuses in the gift exchange game. Cells for each maximal payoff for each type of partner are highlighted.

Potential investor payoffs in the trust game.

| Investment | Payoff from never accused | Payoff from acquitted | Payoff from convicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.14 | 9.89 | 10 |

| 2 | 10.1 | 10.33 | 10.3 |

| 3 | 10.24 | 10.67 | 10.3 |

| 4 | 10.48 | 11.11 | 9.6 |

| 5 | 10.52 | 10.89 | 9.9 |

| 6 | 10.62 | 11.22 | 10.2 |

| 7 | 11.24 | 11.33 | 10.7 |

| 8 | 11 | 11.78 | 11.4 |

| 9 | 11.33 | 11.67 | 10.5 |

| 10 | 11.76 | 11.89 | 9.9 |

Potential employer payoffs in the gift exchange game.

| Wage | Payoff from never accused | Payoff from acquitted | Payoff from convicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 12 | 0.75 | 0 |

| 10 | 14.3 | 4.125 | 5.5 |

| 20 | 16 | 6.25 | 10.83 |

| 30 | 18.9 | 16.3125 | 14.247 |

| 40 | 25.6 | 20.5 | 20.664 |

| 50 | 25.9 | 25.375 | 24.5 |

| 60 | 26.4 | 27.375 | 25.002 |

| 70 | 20.5 | 27.1875 | 23.75 |

| 80 | 19.6 | 24.25 | 21.336 |

| 90 | 15.9 | 20.0625 | 17.25 |

| 100 | 11.2 | 13.5 | 12.834 |

| 110 | 5.667 | 6.9375 | 6.833 |

| 120 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

A4: Alternate Analyses

A4.1 Reciprocity and Betrayal in the Trust Game

In the trust game, for each decision a trustee makes, we calculate whether they reciprocated the trust placed in them by their investor counterpart. In the context of our experiment, reciprocity is divided into three categories: if the trustee returned less than their investor invested in them, we label them a “betrayer”. If they returned exactly what was invested, we label them a “minimal reciprocator”. If they return more than what was invested in them, we label them a “reciprocator”. We investigate two primary questions of significance. First, does interacting with the criminal justice system affect reciprocal behavior? And second, does a subject’s true guilt or innocence predict reciprocal behavior?[13]

Finding A1: The criminal justice outcomes are correlated with increases in extreme reciprocity rates, both high and low. The truly guilty are associated with increased rates of betrayal and the truly innocent with decreased the rates of betrayal, while criminal justice status itself is insignificantly associated with reciprocity.

We use logit models in Table A3, to measure the effects of the criminal justice system on trustee reciprocity. Table A4 displays differences between groups based on Table A3’s regressions. We test for associations between reciprocity and interactions between true innocence/guilt and CJ system outcome using joint hypothesis testing. Table A4 shows that truly innocent trustees are significantly less likely to be betrayer types (p = 0.084) and more likely to be reciprocator types (p = 0.084) than the truly guilty trustees. Truly guilty trustees are also seen to increase betrayal behavior relative to behavior of trustees before interaction with the criminal justice system (p = 0.019). As with our initial analysis of raw returns, we find little evidence that CJ outcomes are associated with differences in reciprocity.

Logit regressions of reciprocity type in the Trust Game. “Never Accused” is an indicator variable for a defendant never having been accused of a crime and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Acquitted” is an indicator variable for a defendant being accused of a crime, but ultimately being found not guilty by a jury and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Convicted” is an indicator variable for whether a defendant was accused of a crime and ultimately found guilty and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Truly Innocent” is an indicator variable for when the defendant truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Truly Guilty” is an indicator variable for when the defendant truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Baylor” is an indicator for the observation being collected on Baylor’s campus, as opposed to the University of California Irvine’s campus. “Offer” is the amount of money (wage) the investor (employer) offered a receiver for any given decision. The excluded group associated with the constant term for both regressions are the Receivers making decisions prior to interaction with the CJ system, before true guilt or innocence could be designated. Robust standard errors clustered at the subject level are given in parentheses.

| Trust game | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betrayer | Minimal reciprocator | Reciprocator | |

| Never Accused × Innocent | 0.451 | −0.653 | 0.208 |

| (0.711) | (0.635) | (0.623) | |

| Never Accused × Guilty | 2.271** | −1.796*** | −1.029 |

| (0.882) | (0.609) | (0.930) | |

| Acquitted × Innocent | 0.630 | −0.0628 | −0.326 |

| (0.856) | (1.285) | (0.864) | |

| Acquitted × Guilty | 1.008 | 0.0561 | −0.736 |

| (1.083) | (0.693) | (0.747) | |

| Convicted × Innocent | 0.369 | −0.949** | 0.433 |

| (0.772) | (0.408) | (0.609) | |

| Convicted × Guilty | 1.478 | −0.299 | −0.882 |

| (1.031) | (1.041) | (0.934) | |

| Baylor | 0.291 | −0.0906 | −0.150 |

| (0.564) | (0.607) | (0.536) | |

| Offer | 0.0605* | −0.170*** | 0.0806*** |

| (0.0312) | (0.0416) | (0.0187) | |

| Constant | −2.219*** | 0.0202 | −0.144 |

| (0.458) | (0.317) | (0.303) | |

| Observations | 720 | 720 | 720 |

-

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Differences in reciprocity types between different CJ outcome groups and true innocence/guilty groups in the Trust Game. “Never Accused” refers to a defendant that was not accused of a crime and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Acquitted” refers to a defendant that was accused of a crime, but ultimately being found not guilty by a jury and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Found Guilty” refers to a defendant that was accused of a crime and ultimately found guilty and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Truly Guilty” refers to a defendant that truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Truly Innocent” refers to a defendant that truly did not take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Before” refers to a subject making decisions prior to interaction with the CJ system. Differences are derived from Offer and Offer interaction terms of Table A3.

| Trust game | Betrayer | p-Value | Minimal reciprocator | p-Value | Reciprocator | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innocent – Before | 1.45 | 0.391 | −1.665 | 0.355 | 0.315 | 0.835 |

| Guilty – Before | 4.757 | 0.019 | −1.831 | 0.206 | −2.647 | 0.124 |

| Never Accused – Before | 2.722 | 0.526 | −2.449 | 0.304 | −0.821 | 0.738 |

| Acquitted – Before | 1.638 | 0.462 | −0.007 | 0.961 | −1.062 | 0.706 |

| Convicted – Before | 1.847 | 0.63 | −1.04 | 0.020 | −0.449 | 0.477 |

| Innocent – Guilty | −3.307 | 0.084 | 0.166 | 0.843 | 2.962 | 0.084 |

| Never Accused – Acquitted | 1.084 | 0.484 | −2.442 | 0.109 | 0.241 | 0.865 |

| Never Accused – Convicted | 0.875 | 0.559 | −1.409 | 0.333 | −0.372 | 0.796 |

| Acquitted – Convicted | −0.209 | 0.902 | 1.033 | 0.465 | −0.613 | 0.679 |

A4.2 Inequity Aversion in the Gift Exchange Game

Next, we turn to inequity aversion. Due to its connection to the gift exchange game literature (Charness and Haruvy 2002), we begin by examining inequity behavior in the gift-exchange game. Inequity aversion measures one’s sensitivity to payoff inequality between the two economic actors (Camerer 2003). Our metric of inequality in the gift exchange game is the difference between payoffs to employers and payoffs to employees. Since inequality is ultimately decided by the second mover, we focus on how their decisions lead to equitable or inequitable outcomes.

Ideally a worker who is concerned only with equity would set their effort to a level that ensured both parties received an equal payoff. However, since this outcome is impossible, we classify subjects’ decisions as equality-concerned when they choose an effort that would result in both partners receiving within 10 dimes[14] of an equal payoff (“Favors Neither”). If the employer receives 11 or more dimes than what would have been equal, then we say the subject has made a “Favors Employer” choice. Similarly, if the worker receives 11 or more dimes than what would have been equal, then we say the subject made a “Favors Employee” choice. We restrict our attention to choices made in a setting where all three outcomes are possible.

Finding A2: While criminal justice status is not predictive of inequity averse behavior, the truly innocent’s behavior is consistent with increased rates of prosocial behavior and inequity aversion.

We use logit models in Table A5, to measure the effects of the criminal justice system on our experimental workers’ inequity preferences. Table A6 displays differences between groups based on Table A5’s regressions. We test for associations between equity preferences and CJ-outcomes and true innocence/guilty using joint hypothesis tests on regression coefficients, the results of which are displayed in Table A6. The associations in the Gift Exchange game are less clear than those found in the Trust Game. What can be shown is that the Truly Innocent are less likely to favor themselves after interaction with the CJ system (p = 0.074) and more likely to return effort that equalizes the payoff between themselves and their employer (p = 0.056). Again, we find little evidence that CJ outcomes are associated with equitable behavior of employees.

Logit regressions of equity type in the Gift Exchange Game. “Never Accused” is an indicator variable for a defendant never having been accused of a crime and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Acquitted” is an indicator variable for a defendant being accused of a crime, but ultimately being found not guilty by a jury and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Convicted” is an indicator variable for whether a defendant was accused of a crime and ultimately found guilty and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Truly Innocent” is an indicator variable for when the defendant truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Truly Guilty” is an indicator variable for when the defendant truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Baylor” is an indicator for the observation being collected on Baylor’s campus, as opposed to the University of California Irvine’s campus. “Offer” is the amount of money (wage) the investor (employer) offered a receiver for any given decision. The excluded group associated with the constant term for both regressions are the Receivers making decisions prior to interaction with the CJ system, before true guilt or innocence could be designated. Robust standard errors clustered at the subject level are given in parentheses.

| Gift exchange | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Favors employer | Favors neither | Favors employee | |

| Never Accused × Innocent | 0.286 | 0.437 | −1.160* |

| (0.576) | (0.317) | (0.686) | |

| Never Accused × Guilty | −1.460 | 0.849 | 0.279 |

| (1.157) | (0.973) | (1.139) | |

| Acquitted × Innocent | −0.729 | 1.055 | −0.796 |

| (0.993) | (0.857) | (1.050) | |

| Acquitted × Guilty | 0.286 | −0.339 | 0.0627 |

| (0.736) | (0.454) | (0.744) | |

| Convicted × Innocent | 0.148 | 0.652 | −1.309 |

| (0.440) | (0.418) | (1.127) | |

| Convicted × Guilty | 0.177 | 0.163 | −0.451 |

| (0.493) | (0.314) | (0.773) | |

| Baylor | 1.627*** | −0.806* | −1.285* |

| (0.594) | (0.449) | (0.739) | |

| Offer | 0.740*** | −0.108 | −0.854*** |

| (0.121) | (0.127) | (0.130) | |

| Constant | −5.555*** | 0.0533 | 4.594*** |

| (0.926) | (0.855) | (0.827) | |

| Observations | 304 | 304 | 304 |

-

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Differences in equity types between different CJ outcome groups and true innocence/guilty groups in the Gift Exchange Game. “Never Accused” refers to a defendant that was not accused of a crime and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Acquitted” refers to a defendant that was accused of a crime, but ultimately being found not guilty by a jury and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Found Guilty” refers to a defendant that was accused of a crime and ultimately found guilty and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Truly Guilty” refers to a defendant that truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Truly Innocent” refers to a defendant that truly did not take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Before” refers to a subject making decisions prior to interaction with the CJ system. Differences are derived from Offer and Offer interaction terms of Table A5.

| Gift exchange (equity) | Favors employer | p-Value | Favors neither | p-Value | Favors employee | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innocent – Before | −0.295 | 0.835 | 2.144 | 0.056 | −3.266 | 0.074 |

| Guilty – Before | −0.997 | 0.535 | 0.673 | 0.584 | −0.109 | 0.950 |

| Never Accused – Before | −1.174 | 0.620 | 1.286 | 0.167 | −0.881 | 0.091 |

| Acquitted – Before | −0.443 | 0.463 | 0.716 | 0.218 | −0.733 | 0.449 |

| Convicted – Before | 0.325 | 0.736 | 0.815 | 0.119 | −1.761 | 0.245 |

| Innocent – Guilty | 0.702 | 0.691 | 1.471 | 0.307 | −3.157 | 0.141 |

| Never Accused – Acquitted | −0.731 | 0.667 | 0.57 | 0.679 | −0.148 | 0.932 |

| Never Accused – Convicted | −1.499 | 0.255 | 0.471 | 0.656 | 0.88 | 0.624 |

| Acquitted – Convicted | −0.768 | 0.550 | −0.099 | 0.923 | 1.028 | 0.567 |

A4.3 Inequity Aversion in the Trust Game

We begin our discussion of inequity aversion in the trust game by defining classes of subjects by the payoff differential (Trustee payoff minus Investor payoff). If the difference is less than −2, we say that the trustee has “Favors Investor” behavior. If the difference is greater than 2, we label the trustee as “Favors Trustee”. If the difference is between −2 and 2, then we say the trustee has a preference for equity and “Favors Neither”.[15]

As was the case in preceding sections, we take advantage of subject’s multiple trustee decisions by using logit models to measure the effect of the criminal justice system on inequity behavior. Tables A7 and A8 show that truly innocent trustees are much less likely to distribute payoffs in a way that favors themselves compared to truly guilty trustees (p = 0.035). While most comparisons reveal that CJ outcomes again have little association for equitable behavior, there is evidence that those who are convicted and guilty are significantly less likely to split payoffs in favor of their investor (p = 0.003).

Logit regressions of equity type in the Trust Game. “Never Accused” is an indicator variable for a defendant never having been accused of a crime and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Acquitted” is an indicator variable for a defendant being accused of a crime, but ultimately being found not guilty by a jury and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Convicted” is an indicator variable for whether a defendant was accused of a crime and ultimately found guilty and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Truly Innocent” is an indicator variable for when the defendant truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Truly Guilty” is an indicator variable for when the defendant truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Baylor” is an indicator for the observation being collected on Baylor’s campus, as opposed to the University of California Irvine’s campus. “Offer” is the amount of money (wage) the investor (employer) offered a receiver for any given decision. The excluded group associated with the constant term for both regressions are the Receivers making decisions prior to interaction with the CJ system, before true guilt or innocence could be designated. Robust standard errors clustered at the subject level are given in parentheses.

| Trust game | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Favors investor | Favors neither | Favors trustee | |

| Never Accused × Innocent | −0.0147 | 0.0909 | −0.121 |

| (0.605) | (0.249) | (0.645) | |

| Never Accused × Guilty | −0.818 | −0.503 | 1.372 |

| (0.967) | (0.439) | (0.866) | |

| Acquitted × Innocent | 0.0578 | −0.191 | 0.197 |

| (1.132) | (0.508) | (0.692) | |

| Acquitted × Guilty | 0.0643 | −0.499 | 0.542 |

| (0.670) | (0.448) | (0.788) | |

| Convicted × Innocent | −0.0672 | 0.446 | −0.710 |

| (0.604) | (0.314) | (0.813) | |

| Convicted × Guilty | −1.559*** | 0.327 | 1.059 |

| (0.525) | (0.362) | f(0.877) | |

| Baylor | 0.0650 | −0.0712 | 0.0261 |

| (0.570) | (0.260) | (0.549) | |

| Offer | −0.594*** | 0.181*** | 0.503*** |

| (0.0623) | (0.0498) | (0.0425) | |

| Constant | 3.174*** | −1.937*** | −4.545*** |

| (0.353) | (0.283) | (0.395) | |

| Observations | 720 | 720 | 720 |

-

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Differences in equity types between different CJ outcome groups and true innocence/guilty groups in the Trust Game. “Never Accused” refers to a defendant that was not accused of a crime and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Acquitted” refers to a defendant that was accused of a crime, but ultimately being found not guilty by a jury and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Found Guilty” refers to a defendant that was accused of a crime and ultimately found guilty and is only defined for post-CJ decisions. “Truly Guilty” refers to a defendant that truly did take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Truly Innocent” refers to a defendant that truly did not take more money than was randomly specified by the experimental software and is only defined in post-CJ decisions. “Before” refers to a subject making decisions prior to interaction with the CJ system. Differences are derived from Offer and Offer interaction terms of Table A7.

| Trust game (equity) | Favors investor | p-Value | Favors neither | p-Value | Favors trustee | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innocent – Before | −0.024 | 0.988 | 0.346 | 0.643 | −0.634 | 0.668 |

| Guilty – Before | −2.313 | 0.122 | −0.675 | 0.396 | 2.943 | 0.078 |

| Never Accused – Before | −0.833 | 0.981 | −0.412 | 0.715 | 1.251 | 0.851 |

| Acquitted – Before | 0.122 | 0.959 | −0.690 | 0.708 | 0.709 | 0.776 |

| Convicted – Before | −1.626 | 0.911 | 0.773 | 0.155 | 0.349 | 0.383 |

| Innocent – Guilty | 2.289 | 0.190 | 1.021 | 0.243 | −3.577 | 0.035 |

| Never Accused – Acquitted | −0.955 | 0.543 | 0.278 | 0.725 | 0.542 | 0.700 |

| Never Accused – Convicted | 0.793 | 0.521 | −1.185 | 0.060 | 0.902 | 0.540 |

| Acquitted – Convicted | 1.748 | 0.214 | −1.463 | 0.061 | 0.36 | 0.794 |

References

Agan, A., and S. Starr. 2017. “Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Racial Discrimination: A Field Experiment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics: 191–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx028.Suche in Google Scholar

Aimone, J., C. North, and L. Rentschler. 2019. “Priming the Jury by Asking for Donations: An Empirical and Experimental Study.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 160: 158–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2019.01.022.Suche in Google Scholar

Alper, M., M. Durose, and J. Markman. 2018. 2018 Update on Prison Recidivism: A 9-Year Follow-Up Period (2005 – 2014). U.S. Department of Justice.Suche in Google Scholar

Bar-Gill, O., and O. G. Ayal. 2006. “Plea Bargains Only for the Guilty.” The Journal of Law and Economics 49 (1): 353–64. https://doi.org/10.1086/501084.Suche in Google Scholar

Bardsley, N. 2008. “Dictator Game Giving: Altruism or Artefact?” Experimental Economics: 122–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-007-9172-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Berg, J., J. Dickhaut, and K. McCabe. 1995. “Trust, Reciprocity, and Social History.” Games and Economic Behavior 10 (1): 122–42. https://doi.org/10.1006/game.1995.1027.Suche in Google Scholar

Bornstein, B., and E. Greene. 2011. “Jury Decision Making: Implications for and from Psychology.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 20 (1): 63–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410397282.Suche in Google Scholar

Bushway, S., A. Redlich, and R. Norris. 2014. “An Explicit Test of Plea Bargaining in the “Shadow of the Trial”.” Criminology 52 (4): 723–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12054.Suche in Google Scholar

Camerer, C. 2003. Behavioral Game Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Charness, G. 2004. “Attribution and Reciprocity in an Experimental Labor Market.” Journal of Labor Economics 22 (3): 665–88. https://doi.org/10.1086/383111.Suche in Google Scholar

Charness, G., and G. DeAngelo. 2018. “Law and Economics in the Laboratory.” In Research Handbook on Behavioral Law and Economics, edited by J. C. Teitelbaum, and K. Zeller, 321–46. Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781849805681.00023Suche in Google Scholar

Charness, G., and E. Haruvy. 2002. “Altruism, Equity, and Reciprocity in a Gift-Exchange Experiment: An Encompassing Approach.” Games and Economic Behavior 40 (2): 203–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-8256(02)00006-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Couloute, L., and D. Kopf. 2018. “Out of Prison & Out of Work: Unemployment Among Formerly Incarcerated People.” Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html.Suche in Google Scholar

D’Alessio, S. J., and L. Stolzenberg. 2019. “Should Repeat Offenders Be Punished More Severely for Their Crimes?” Criminal Justice Policy Review 30 (5): 731–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403417701974.Suche in Google Scholar

Doleac, J. L., and B. Hansen. 2020. “The Unintended Consequences of “Ban the Box”: Statistical Discrimination and Employment Outcomes When Criminal Histories Are Hidden.” Journal of Labor Economics 2: 321–74. https://doi.org/10.1086/705880.Suche in Google Scholar

Finn, R. H., and P. A. Fontaine. 1985. “The Association between Selected Characteristics and Perceived Employability of Offenders.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 12 (3): 353–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854885012003005.Suche in Google Scholar

Grossman, Gene M., and Michael L. Katz. 1983. “Plea Bargaining and Social Welfare.” The American Economic Review 73 (4): 749–57.Suche in Google Scholar

Guthrie, C., J. Rachlinski, and A. Wistrich. 2007. “Blinking on the Bench: How Judges Decide Cases.” Cornell Law Review 93 (1): 1–43.Suche in Google Scholar

Holzer, H. J., S. Raphael, and M. A. Stoll. 2003. Employment Dimensions of Reentry: Understanding the Nexus Between Prisoner Reentry and Work. Urban Institute Reentry Rountable. New York: New York University Law School/Urban Institute.Suche in Google Scholar

Kinner, S., and E. A. Wang. 2014. “The Case for Improving the Health of Ex-Prisoners.” American Journal of Public Health 104 (8): 1352–5. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2014.301883.Suche in Google Scholar

List, J. 2007. “On the Interpretation of Giving in Dictator Games.” Journal of Political Economy: 482–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/519249.Suche in Google Scholar

Marselli, R., B. C. McCannon, and M. Vannini. 2015. “Bargaining in the Shadow of Arbitration.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 117: 356–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.06.016.Suche in Google Scholar

Minson, J., and J. Mueller. 2012. “The Cost of Collaboration: Why Joint Decision Making Exacerbates Rejection of Outside Information.” Psychological Science 23 (3): 219–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611429132.Suche in Google Scholar

Pogorzelski, W., N. Wolff, K.-Y. Pan, and C. Blitz. 2005. “Behavioral Health Problems, Ex-Offender Reentry Policies, and the “Second Chance Act”.” American Journal of Public Health 95 (10): 1718–24. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2005.065805.Suche in Google Scholar

Rachlinski, J., S. Johnson, A. Wistrich, and C. Guthrie. 2009. “Does Unconscious Racial Bias Affect Trial Judges?” The Notre Dame Law Review 84 (3): 1195–246.Suche in Google Scholar

Rachlinski, J. J., C. Guthrie, and A. J. Wistrich. 2011. “Probable Cause, Probability, and Hindsight.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Vanderbilt Law and Economics Paper 11–38: 72–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2011.01230.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Ralston, J., J. A. Aimone, C. M. North, and L. Rentschler. 2019. False Confessions: An Experimental Study of the Innocence Problem. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3483736.10.2139/ssrn.3483736Suche in Google Scholar

Raphael, S. 2018. “The Employment Prospects of Ex-Offenders.” In Social Policy Approaches that Promote Self-Sufficiency and Financial Independence Among the Poor, edited by C. Heinrich, and J. Scholz. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.Suche in Google Scholar

Rose, E. K. 2021. “Does Banning the Box Help Ex-Offenders Get Jobs? Evaluating the Effects of a Prominent Example.” Journal of Labor Economics 39 (1): 79–113. https://doi.org/10.1086/708063.Suche in Google Scholar

Sawyer, W., and P. Wagner. 2020. “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020.” https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html.Suche in Google Scholar

Schwartz, R. D., and J. H. Skolnick. 1963. “Two Studies of Legal Stigma.” Social Problems 10 (2): 133–42. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1962.10.2.03a00030.Suche in Google Scholar

Uggen, C., J. Manza, and M. Thompson. 2006. “Citizenship, Democracy, and Civic Reintegration of Criminal Offenders.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 605: 281–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206286898.Suche in Google Scholar

Western, B., A. A. Braga, J. Davis, and C. Sirois. 2015. “Stress and Hardship after Prison.” American Journal of Sociology 120 (5): 1512–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/681301.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/rle-2024-0053).

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The Impact of Online Dispute Resolution on the Judicial Outcomes in India

- Legal Compliance and Detection Avoidance: Results on the Impact of Different Law-Enforcement Designs

- Women in Piracy. Experimental Perspectives on Copyright Infringement

- Is Investment in Prevention Correlated with Insurance Fraud? Theory and Experiment

- Bias, Trust, and Trustworthiness: An Experimental Study of Post Justice System Outcomes

- Do Sanctions or Moral Costs Prevent the Formation of Cartel Agreements?

- Efficiency and Distributional Fairness in a Bankruptcy Procedure: A Laboratory Experiment

- Soft Regulation for Financial Advisors

- Conciliation, Social Preferences, and Pre-Trial Settlement: A Laboratory Experiment

- The Impact of Tax Culture on Tax Rate Structure Preferences: Results from a Vignette Study with Migrants and Non-Migrants in Germany

- Perceptions of Justice: Assessing the Perceived Effectiveness of Punishments by Artificial Intelligence versus Human Judges

- Judged by Robots: Preferences and Perceived Fairness of Algorithmic versus Human Punishments

- The Hidden Costs of Whistleblower Protection

- The Missing Window of Opportunity and Quasi-Experimental Effects of Institutional Integration: Evidence from Ukraine

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The Impact of Online Dispute Resolution on the Judicial Outcomes in India

- Legal Compliance and Detection Avoidance: Results on the Impact of Different Law-Enforcement Designs

- Women in Piracy. Experimental Perspectives on Copyright Infringement

- Is Investment in Prevention Correlated with Insurance Fraud? Theory and Experiment

- Bias, Trust, and Trustworthiness: An Experimental Study of Post Justice System Outcomes

- Do Sanctions or Moral Costs Prevent the Formation of Cartel Agreements?

- Efficiency and Distributional Fairness in a Bankruptcy Procedure: A Laboratory Experiment

- Soft Regulation for Financial Advisors

- Conciliation, Social Preferences, and Pre-Trial Settlement: A Laboratory Experiment

- The Impact of Tax Culture on Tax Rate Structure Preferences: Results from a Vignette Study with Migrants and Non-Migrants in Germany

- Perceptions of Justice: Assessing the Perceived Effectiveness of Punishments by Artificial Intelligence versus Human Judges

- Judged by Robots: Preferences and Perceived Fairness of Algorithmic versus Human Punishments

- The Hidden Costs of Whistleblower Protection

- The Missing Window of Opportunity and Quasi-Experimental Effects of Institutional Integration: Evidence from Ukraine