Abstract

We examine the contribution of institutional integration to a country’s institutional capacity. To this end, we examine the effects of remaining outside of the European integration process for 28 Ukrainian provinces in the period 1996–2020. We construct novel, machine-learning supported subnational estimates of institutional capacity and quality for Ukraine and for central and eastern European countries that have completed institutional integration. Based on the latent residual component extraction of institutional quality from the existing governance indicators, we use Bayesian posterior analysis under non-informative objective prior function to construct institutional quality indicators from more than 1.8 million randomly sequenced samples across Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations. By comparing the residualized institutional quality trajectories of Ukrainian provinces with their central and eastern European peers that were admitted to the European Union in 2004 and after, we assess the institutional quality cost of failing to institutionally integrate with the EU. Based on the large-scale synthetic control and difference-in-differences analysis, we find evidence of large-scale negative institutional quality and capacity effects of missing the European integration path such as heightened political instability and rampant deterioration of the rule of law and control of corruption. The statistical significance of the estimated effects is evaluated across a comprehensive placebo simulation with more than 34 billion placebo averages for each institutional quality outcome.

1 Introduction

The notion that institutional integration matters for inclusive economic growth and sustainable development has become well-established both in scholarly literature and policy debate (Rivera-Batiz and Romer 1991; Eichengreen 2007; Campos et al. 2019; Felbermayr et al. 2022).[1] For instance, Campos et al. (2019) examine the economic growth effect of European Union membership for a sample of non-founding member states in the year 1950, finding positive but heterogeneous effects, and show that trade openness, financial development, adoption of a single currency, and lighter regulation of product and labor markets amplify the benefits of the deep institutional integration.[2] The raison d’être behind the study of the long-term effects of institutional integration invokes a quasi-experimental approach, seeking to estimate trajectories of economic and institutional outcomes in the hypothetical absence of the integration (Abadie et al. 2015). The general thrust of such an approach is that by making use of quasi-experimental methods for macro-institutional analyses such as difference-in-differences or synthetic control estimators, an appropriate counterfactual scenario can be estimated either with or without the parallel trends prior to the integration. If the economic effects of large-scale institutional integration are well understood (Maseland and Spruk 2023), the question that remains less clear is simple and straightforward. Namely, what is the effect of by-passing a deep and comprehensive institutional integration? If a certain type of institutional integration such as the European Union (EU) or Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) boosts trade, innovation and growth, and improves the institutional fabric, estimating the costs of the missing institutional integration for the entities left out of such multinational agreements, may be relatively more informative than estimating the benefits of the accession and admission. And second, perhaps the most obvious question to ask beforehand is whether the path towards a deep and inclusive institutional integration improves the institutional fabric such as the strength of the rule of law, the efficacy of public administration and the control of corruption. Against this backdrop, Williamson (2000) proposed a hierarchy of institutions where different layers of institutions coalesce into the social analysis and differ with respect to the degree of embeddedness and frequency of change over time where the missing windows of opportunity for institutional reform can be identified.[3]

In this paper, we examine the contribution that missing this window of opportunity for broad-based institutional reform makes to the quality and strength of institutions. In particular, we examine the effects of remaining outside of the European integration process on the institutional quality of Ukraine and its provinces in the period 1996–2020. First, we estimate the institutional quality of Ukrainian provinces by extracting the residual component of quality from a series of existing aggregate governance indicators through the variation in pre-determined exogenous geographic characteristics (Emery et al. 2023).[4] By comparing the full set of Ukrainian provinces to a full sample of donor regions from Central and Eastern Europe that have completed the European integration process until 2020, we assess a counterfactual scenario of the missing window of opportunity posited by such rare momentum toward broad-based institutional reforms. Our contribution offers a quasi-experimental analysis of missing windows of opportunity and is of reasonable relevance to the policymakers in better understanding what actions ought to be taken in expanding broad-based and relatively inclusive multinational governance agreements such as membership in the European Union to the potentially admissible entities such as Ukraine. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the conceptual framework, data, variables and samples used in our analysis. Section 3 discusses the identification strategy. Section 4 presents and discusses the results along with the robustness checks. Section 5 concludes.

2 Disaggregating the Quality of Institutions

2.1 Approach

Our approach to measure institutional quality in Ukrainian regions is constrained by the lack of observable and measurable characteristics to provide insights into the variation in institutional quality. To address these concerns, our empirical strategy to measure subnational institutional quality relies on the extraction of the residual component of institutional quality from the observable aggregate institutional quality series using the variation in pre-determined geographic characteristics (Focacci et al. 2023). By using a well-established series of governance indicators (Kaufmann et al. 2011), our aim is to extract a latent variable component from higher-level aggregation and project it to the subnational-level using the set of pre-determined characteristics that cannot be empirically manipulated. The extraction of the residual component of institutional quality conveys an important intuitive advantage compared to the existing quality measures. A zero residual level indicates the level of institutional quality A positive residual component indicates the level of institutional quality that is better than the one plausibly expected in geographically similar areas in the control sample. A zero residual component invariably suggests that the level of institutional quality is on par with the level expected in geographically similar areas. By contrast, a negative residual component suggests that the implied level of quality is worse than what would be expected in the areas with geographically similar endowment. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that our proposed measure of institutional quality is a residual rather than directly observed measure. We also collect region-level data on observable outcomes for the entire sample of Ukrainian regions on the election outcomes in 2004 and 2010, voter turnout in 2015, as well as protest activity during the Maidan Revolution and civilian causalities during the Russian-Ukrainian war since 2014, and correlate our residual measures with the observed counterparts. Against this backdrop, the correlation between our residual measures and real-time observed institutional and political variables is between +0.61 and +0.82, and is statistically highly significant (i.e. p-value = 0.000). Supplementary Appendix 1 provides a more elaborate and extensive discussion of the residual component and its validity.

2.2 Sample

Our treatment sample consists of 24 Ukrainian provinces (i.e. oblasts)[5] and two cities with special status.[6] Our control sample comprises 195 regions from the Central and Eastern European countries that were admitted to the European Union in 2004 and later, which includes Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. Our respective period of investigation comprises the years between 1996 and 2020. Our overall sample covers 5525 region-year observations pooled into a strongly balanced panel. The size of the treatment sample comprises 650 region-year paired observations whilst the size of the control sample comprises 4875 paired observations.

3 Identification Strategy

3.1 Setup

Our goal is to examine the effect of remaining outside of the European integration process to the quality of institutions consistently. In this respect, our aim is to estimate the missing counterfactual scenario and construct the trajectories of institutional quality of Ukrainian regions in the hypothetical absence of the missing integration process. To this end, we apply the synthetic control estimator (Abadie and Gardeazabal 2003; Abadie et al. 2015; Gobillon and Magnac 2016; Gilchrist et al. 2023) to estimate the effect of missing European integration on the quality of institutions. By adopting the framework of potential outcomes, we simulate the region-level trajectories of institutional quality by making use of the implicit attributes of region-level residualized institutional quality from Central and Eastern European countries that have joined and completed the European integration process in the respective period of investigation. This particular approach allows us to build the respective counterfactual realization of institutional quality using weighted averages of outcome-specific, region-level attributes and characteristics obtained by making use of several machine-learning features before the stay-out period, that best track and reproduce the path of residualized institutional quality of Ukrainian regions. Using the benchmark path of pre-treatment outcomes and auxiliary geographic covariates as the battery of predictive variables and dynamic nested optimization with a Newton-Raphson algorithm to find the convex root of the differentiable objective function, we show that our modification of the synthetic control estimator provides an excellent quality of the pre-treatment fit in the residualized trajectories of institutional quality further reinforced by low imbalance between Ukrainian regions and their synthetic counterparts. Our modification of the synthetic control estimator is described in greater detail in Supplementary Appendix 2.

A potential caveat against the validity of the treatment effect arises from the choice of treatment year. Since admission to the European Union is contingent on a series of institutional and policy reforms,[7] most of the countries included in the donor pool implemented these reforms through a variety of financial mechanisms. Some countries in the donor pool also joined Eurozone and Schengen area that ended internal border controls and established a common visa policy. To partially mitigate these concerns, it is therefore crucial that these reforms are more or less completed by the time of the treatment year. In this respect, beginning the stay-out treatment in 2004 may be problematic since a strong anticipatory component is present in the donor pool. To address this particular caveat, we base our treatment year in 2007 when the European Commission’s reform screening process was largely completed in all countries included in our donor pool.

3.2 Inference

To evaluate the significance of the effect of remaining outside of the European integration, we rely on the standard treatment permutation test, and ask whether the estimated gap in institutional quality is obtained by chance. Although large-sample asymptotic inference is not permittable when making use of a synthetic control estimator, the use of the treatment permutation method for inferential purposes may detect whether or not the estimated institutional quality gaps are relatively unique to Ukraine or are also perceptible in other regions in the donor pool. To fill the void in the analysis, we perform a simple in-space placebo analysis, by iteratively shifting the stay-out to the other regions in the donor pool. Our interpretation is simple and straightforward. If the estimated post-2008 gaps are also perceivable in other regions across the Central and Eastern European donor pool, then the notion of a significant effect associated with staying-out of the integration process may not be credible. By contrast, if the estimated gaps are unique to the Ukrainian regions and cannot be detected elsewhere, then the supposition of a significant effect becomes more credible and noteworthy. Through the iterative assignment of the stay-out to the unaffected regions, the p-values on the null hypothesis are computed for each outcome-year pair in the post-treatment period (Cavallo et al. 2013) which yields a very large number of placebo gaps to be estimated. Further details behind the placebo analysis are elicited in Supplementary Appendix 3.

4 Results

4.1 Baseline

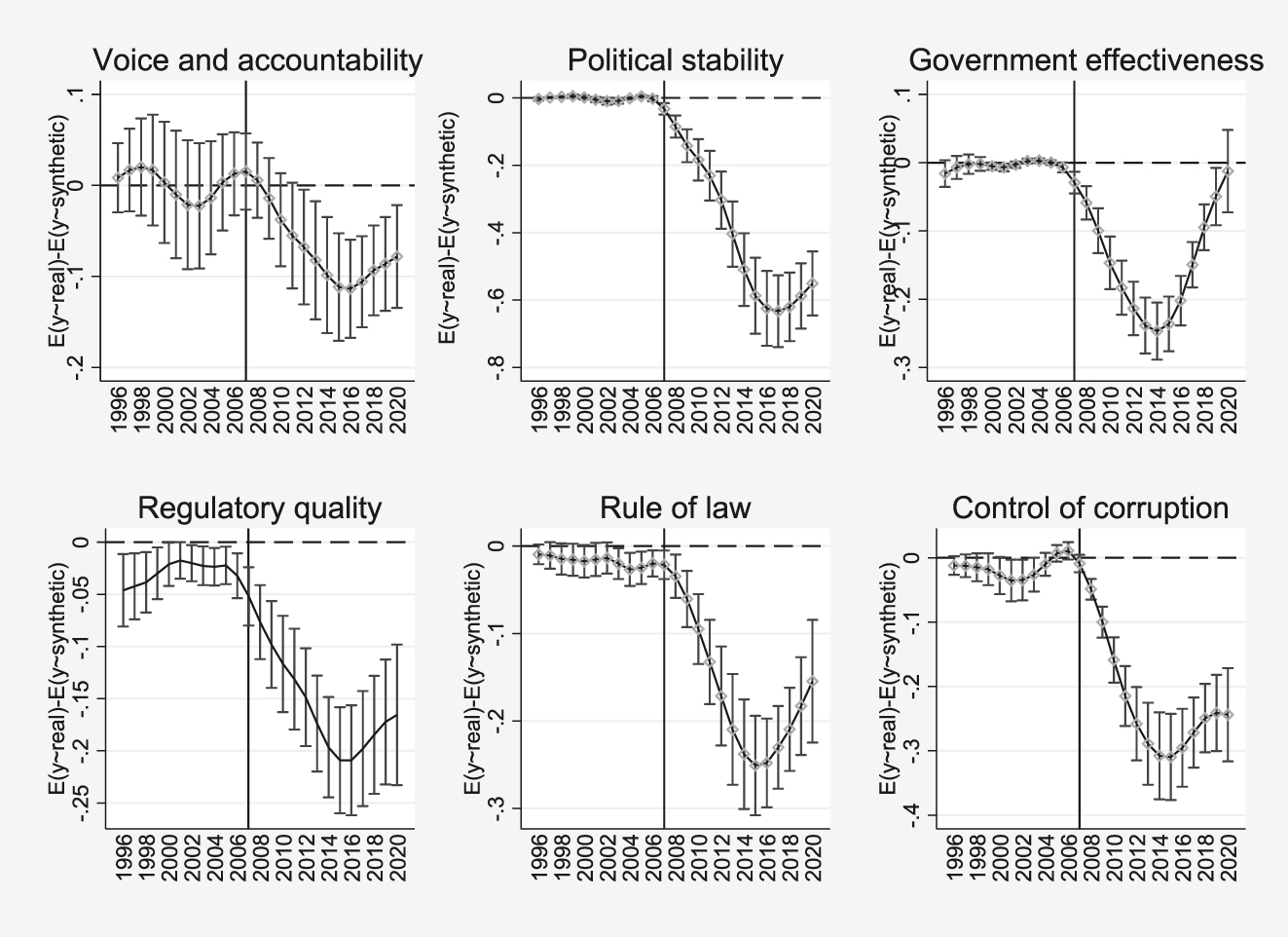

Figure 1 presents the average treatment effect of remaining out of the European Union for the full province-level treatment sample. Our synthetic control estimates suggest that Ukrainian provinces have developed substantially worse institutional quality by their exclusion from the European Union compared to the regions and counties of countries that have entered the European Union in 2004 and later. The estimated set of average treatment effects also indicates an invariably worse trajectory of institutional quality after 2008, a notable outcome-specific heterogeneity. More specifically, the largest drop in institutional quality outcome is perceptible for the level of political stability and absence of violence which appears to deteriorate, on average, by 40 percent (i.e. p-value = 0.000) vis-á-vis the synthetic Central and Eastern European control groups. In a similar vein, our synthetic control estimates indicate a pervasive deterioration in the control of corruption, which seems to worsen by 20 percent (i.e. p-value = 0.000) and in regulatory quality by 11 percent (i.e. p-value = 0.000) whereas rule of law tends to retrograde by 15 percent (i.e. p-value = 0.000) relative to the condensed synthetic control groups. The estimated retrogression of the rule of law, political stability and the control of corruption appears to be permanent in that it does not seem to disappear up to early 2020. By contrast, we find evidence of a temporary deviation in the trajectories of regulatory quality and government effectiveness which seem to worsen sharply by 23 percent by 2015 whilst the negative effect tends to disappear up to the end-of-sample period and is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Average region-level treatment effect of remaining out of the European integration process on institutional quality trajectories across Ukraine, 1996–2020.

Hence, our results imply that a hypothetical admission of Ukraine to the EU would substantially improve the institutional quality, whereas the admission to the EU does not appear to be a necessary condition for improving the institutional quality of government administration where plausible policy alternatives can equally improve the efficacy of the administration. Given the previously recognized importance of the rule of law, political stability and the control of corruption for sustained economic growth and social development, our conjecture is that the admission into a more inclusive institutional integration would generate marked, substantial and permanent gains in institutional quality. A more exhaustive and detailed discussion of results is elaborated in Supplementary Appendix 3.

4.2 Large-Sample In-Space Placebo Analysis

Our approach to tackle the statistical significance of the effect of staying out of the European Union on the institutional quality of Ukrainian provinces consists of the in-space placebo analysis. In particular, the stay-out of the European Union is assigned to the regions in the donor pool that have not stayed out of the European Union which effectively shifts Ukrainian provinces to the donor pool. Through an iterative application of the synthetic control estimator to the unaffected regions, we estimate a large vector of placebo gaps and evaluate the estimated effects for Ukrainian provinces compared to the effect sequence from placebo runs. If the institutional quality effects estimated for Ukrainian provinces are particularly large and unique, the notion of significant effects associated with remaining outside of the European Union becomes more credible. By contrast, if the gaps estimated for Ukrainian provinces do not seem to be substantially different from the placebo gaps, then our conclusion is that the analysis fails to provide evidence of a significant effect of staying out of the European Union. For each institutional quality outcome under consideration, we compute two-tailed p-values and proceed with the benchmark rejection rule implying no effect whatsoever through inversely weighted placebo gaps. Given the size of the treatment sample and the donor pool and the length of the pre-treatment period, we compute more than 34 billion placebo gap averages. A relatively large number of placebo averages allows us to use an almost full random sampling approach towards treatment permutation and improves the consistency of the estimated p-values denoting the probability of no effect whatsoever. Apart from the standard p-values, we also undertake a simple difference-in-differences analysis of placebo gap coefficients to determine parametrically whether the gaps estimated for Ukrainian provinces are statistically significantly different from the placebo gaps. Each specification also contains the full set of region-fixed effects and time-fixed effects to absorb the confounding influence of the heterogeneity bias from the estimated post-treatment coefficient.

Table 1 reports difference-in-differences analysis of in-space placebo gaps of remaining out of the European Union. Our key parameter of interest is the average post-2007 institutional quality gap across Ukrainian provinces for each institutional outcome under consideration. The evidence from the placebo analysis uncovers a high degree of uniqueness of the institutional quality gap. Controlling for the unobserved region-specific and time-varying heterogeneity, the estimated coefficients for the Ukrainian province-level post-treatment gaps are large and statistically significant at the 1 percent level. Consistent with the estimated magnitudes, the largest post-treatment coefficients are found with respect to the political stability and absence of violence, control of corruption and the strength of the rule of law. The difference-in-differences analysis thus largely confirms the significance of the estimated gaps for Ukrainian provinces and highlights relatively high losses associated with remaining outside of the European Union. A more granular and detailed inference on the treatment effect of the stay-out is reported in Supplementary Appendix 4. Furthermore, Supplementary Appendix 5 provides a more extensive empirical discussion of the correlates behind the institutional quality gaps.

In-space placebo analysis of staying out of European integration process.

| Voice and accountability | Political stability and absence of violence | Government effectiveness | Regulatory quality | Rule of law | Control of corruption | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Implied outcome gap | −0.061*** (0.012) | −0.401*** (0.037) | −0.135*** (0.013) | −0.085*** (0.011) | −0.145*** (0.017) | −0.200*** (0.021) |

| 95 % confidence bounds | {−0.087, −0.036} | {−0.475, −0.327} | {−0.162, −0.108} | {−0.092, −0.046} | {−0.180, −0.110} | {−0.242, −0.159} |

| # observations | 5525 | 5525 | 5525 | 5525 | 5525 | 5525 |

| # treated regions | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| # control regions | 195 | 195 | 195 | 195 | 195 | 195 |

| R 2 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.13 | |

| # placebo averages | >34 billion | >34 billion | >34 billion | >34 billion | >34 billion | >34 billion |

| Permutation method | Random sampling | Random sampling | Random sampling | Random sampling | Random sampling | Random sampling |

| Region-fixed effects (p-value) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) |

| Time-fixed effects (p-value) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) | YES (0.000) |

-

Notes: The table reports post-stay out coefficients on institutional quality gaps estimated by synthetic control method. Each specification includes the full set of region-fixed effects and time-fixed effects. The standard of the estimated placebo gap coefficients is adjusted for arbitrary heteroscedasticity and serially correlated stochastic disturbances using finite-sample adjustment of the empirical distribution function with an error component model. Cluster-robust standard errors are denoted in the parentheses. Asterisks denote statistically significant coefficients at 10 % (*), 5 % (**), and 1 % (***), respectively.

4.3 Synthetic Difference-in-Differences Estimates

One potential caveat arises from the feasibility and potential existence of a parallel trend assumption. To fill the void in the literature, Arkhangelsky et al. (2021) propose a hybrid synthetic control and difference-in-differences estimation combining the attractive features of both methods.[8] Since the details behind the synthetic difference-in-differences estimator extend beyond the goals of this paper, we discuss its properties and counterfactual weights in greater detail in Supplementary Appendix 6.

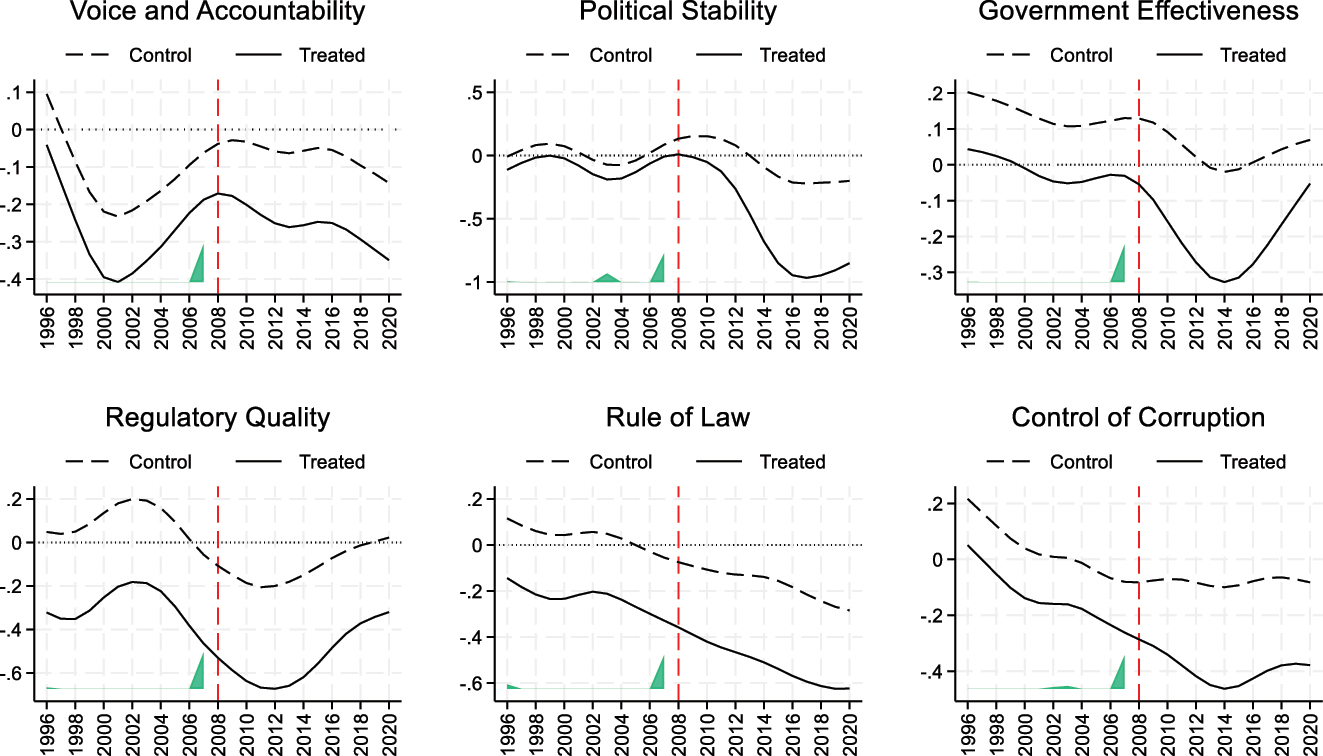

Table 2 reports the synthetic difference-in-differences estimated institutional quality impact of staying out of the European integration on the full sample of Ukrainian provinces. The table reports the differences in each institutional quality outcome denoted by δ adjusted for region- and time-specific weights. The point estimates confirm the evidence of widespread deterioration in the trajectories of institutional quality compared to the Central and Eastern European donor pool. In particular, synthetic difference-in-differences estimates indicate pervasive deterioration in democratic accountability and freedom of the press as well as substantially more deleterious efficacy of the government administration alongside significantly diminished rule of law and weaker enforcement of anti-corruption framework. For each respective outcome, the null hypothesis of zero treatment effect of exclusion from the European Union is rejected at 1 %, respectively (i.e. p-value = 0.000). The trajectory of regulatory framework for private-sector development appears to be the only component unaffected by the missing window of European integration (i.e. p-value = 0.488). Overall, the deterioration in institutional quality trajectories appears to be permanent. Figure 2 exhibits outcome-specific institutional quality gaps associated with the missing window of European integration, and reiterates the evidence of relatively large losses associated with missing the European integration process. The estimated losses are particularly large and confirm pervasive deterioration of political stability, corrosive weakening of the rule of law, and substantial annihilation of the control of corruption. Region-specific weights in the composition of synthetic control groups are reported and detailed in Supplementary Appendix 7.

Synthetic difference-in-differences estimated effect of remaining outside of the European Union on institutional quality of Ukrainian provinces, 1996–2020.

| Voice and accountability | Political stability and absence of violence | Government effectiveness | Regulatory quality | Rule of law | Control of corruption | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Synthetic difference-in-differences estimated treatment effect of the missing European integration | ||||||

|

|

−0.061*** (0.009) | −0.392*** (0.034) | −0.082*** (0.020) | −0.014 (0.020) | −0.073*** (0.021) | −0.129*** (0.021) |

| Two-tailed 95 % confidence interval | (−0.079, −0.041) | (−0.459, −0.324) | (−0.122, −0.042) | (−0.054, 0.025) | (−0.114, −0.032) | (−0.170, −0.089) |

| Empirical p-value (large-sample approximation) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.488 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| #non-zero weight donors | 93 | 186 | 221 | 175 | 175 | 180 |

| Panel B: Time-specific weight shares | ||||||

| 1996 | 0 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.037 | 0.116 | 0 |

| 1997 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1998 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1999 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.044 |

| 2003 | 0 | 0.228 | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0.074 |

| 2004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2006 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2007 | 1 | 0.752 | 0.988 | 0.962 | 0.883 | 0.881 |

| 2008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2020 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

-

Notes: The table presents synthetic difference-in-differences estimated institutional quality gaps for six different residualized components for a full sample of Ukrainian provinces in the period 1996–2020 using a donor pool of 221 Central and Eastern European regions. The treatment effect is computed as the pre-versus post-difference-in-difference of each institutional quality outcome between Ukrainian provinces and their synthetic control groups where the latter is chosen as an optimally weighted function of regions unexposed to the missing European integration and pre-treatment time period. Time-specific weights (i.e. lambda) are reported in Panel B. The standard errors are adjusted for serially correlated stochastic disturbances and arbitrary heteroskedasticity of the error variance using bootstrapped random sampling with replacement across 1000 iterations for each specification. Standard errors are reported in the parentheses. The p-value on the null hypothesis of zero effect of the exclusion from the European integration process is computed using a large-sample approximation method. Asterisks denote statistically significant coefficients at 1 % (***), 5 % (**), and 10 % (*), respectively.

Synthetic difference-in-differences estimated institutional quality gaps of exclusion from the European Union across Ukrainian provinces, 1996–2020.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, we examine the institutional quality effects of institutional integration. To this end, we estimate the effects of remaining outside of the European Union on the institutional quality of the Ukrainian provinces for the period 1996–2020. By comparing the institutional quality trajectory of 24 Ukrainian provinces with the donor pool of 195 central and eastern European regions that were admitted to the European Union in 2004 and subsequent enlargement rounds, we assess the institutional quality cost of the missing European integration and highlight the potential benefits of admission to broad-based and relatively inclusive multinational governance agreements. By making use of the novel dataset measuring subnational institutional quality generated through the application of Bayesian posterior analysis supported by a machine learning-based algorithm, we are able to better unravel the heterogeneity in the benefits of the hypothetical membership in multinational governance agreements underpinned by a deep form of institutional integration.

Based on disaggregated synthetic control analysis, we find evidence of significant and substantial institutional quality improvements in response to the hypothetical admission of Ukraine to the European integration path. The evidence invariably pinpoints substantial institutional quality gains in terms of improved political stability, reduced violence, strengthened liberal democratic governance, stronger rule of law and better control of corruption. Without the loss of generality, the evidence thus suggests that the hypothetical integration into a European multinational governance agreement (i.e. EU) can generate a positive deep institutional shock promulgating an improvement of multiple layers of institutional quality such as the rule of law which Ukraine would find difficult to develop from its domestic political economy equilibrium without the EU membership.

Our analysis provides several noteworthy policy-relevant normative implications. First, by remaining outside of the European integration process, Ukrainian provinces’ institutional quality has deteriorated considerably compared to the trajectories in the donor pool of central and eastern European regions that have been integrated into the European Union circuit. Second, Ukrainian provinces have undergone a worsening control of corruption, a steady drop in the efficacy of the rule of law, widespread limitations on the freedom of expression, and rampant deterioration of political stability. Furthermore, we tackle the statistical significance of institutional quality gaps through a large-scale placebo analysis that involves a simulation with more than 34 billion placebo averages for each institutional quality outcome under consideration.

As a final note, it should be stressed that additional checks of external validity are necessary before a definitive conclusion may be drawn on the generalization of the European Union’s institutional integration and its effect on institutional quality and economic performance. Whilst our investigation suggests significant benefits accruing from the hypothetical membership for Ukraine, extending the scope of analysis to the regions with similar historical experience and contemporaneous domestic instability such as the Western Balkans that can be considered at least remote candidates for EU membership would uncover interesting insights on the potential benefits of the admission that could be compared to the benefits estimated for Ukraine.

References

Abadie, A., and J. Gardeazabal. 2003. “The Economic Costs of Conflict: A Case Study of the Basque Country.” The American Economic Review 93 (1): 113–32. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803321455188.Search in Google Scholar

Abadie, A., A. Diamond, and J. Hainmueller. 2015. “Comparative Politics and the Synthetic Control Method.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12116.Search in Google Scholar

Arkhangelsky, D., S. Athey, D. A. Hirshberg, G. W. Imbens, and S. Wager. 2021. “Synthetic Difference-In-Differences.” The American Economic Review 111 (12): 4088–118. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190159.Search in Google Scholar

Badinger, H. 2005. “Growth Effects of Economic Integration: Evidence from the EU Member States.” Review of World Economics 141: 50–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-005-0015-y.Search in Google Scholar

Campos, N. F., F. Coricelli, and L. Moretti. 2019. “Institutional Integration and Economic Growth in Europe.” Journal of Monetary Economics 103: 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2018.08.001.Search in Google Scholar

Cavallo, E., S. Galiani, I. Noy, and J. Pantano. 2013. “Catastrophic Natural Disasters and Economic Growth.” Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (5): 1549–61.10.1162/REST_a_00413Search in Google Scholar

Crespo Cuaresma, J., D. Ritzberger-Grünwald, and M. A. Silgoner. 2008. “Growth, Convergence and EU Membership.” Applied Economics 40 (5): 643–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840600749524.Search in Google Scholar

Eichengreen, B. 2007. The European Economy Since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and Beyond. Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400829545Search in Google Scholar

Emery, T. J., M. Kovac, and R. Spruk. 2023. “Estimating the Effects of Political Instability in Nascent Democracies.” Jahrbucher für Nationalokonomie und Statistik 243 (6): 599–642. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2022-0074.Search in Google Scholar

Felbermayr, G., J. Groeschl, and I. Heiland. 2022. “Complex Europe: Quantifying the Cost of Disintegration.” Journal of International Economics 138: 1–28.10.1016/j.jinteco.2022.103647Search in Google Scholar

Focacci, C. N., M. Kovac, and R. Spruk. 2023. “Ethnolinguistic Diversity, Quality of Local Public Institutions, and Firm-Level Innovation.” International Review of Law and Economics 75: 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2023.106155.Search in Google Scholar

Garoupa, N., and R. Spruk. 2024. “A Region-Level Analysis of the Long-Term Economic Effects of Joining the European Union.” In The EU Reexamined: A Governance Model in Transition, edited by J. A. Kämmerer, H. B. Schäfer, and K. Basu, 177–222. London: Edward Elgar.10.4337/9781035314867.00015Search in Google Scholar

Gilchrist, D., T. Emery, N. Garoupa, and R. Spruk. 2023. “Synthetic Control Method: A Tool for Comparative Case Studies in Economic History.” Journal of Economic Surveys 37 (2): 409–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12493.Search in Google Scholar

Gobillon, L., and T. Magnac. 2016. “Regional Policy Evaluation: Interactive Fixed Effects and Synthetic Controls.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 98 (3): 535–51.10.1162/REST_a_00537Search in Google Scholar

Kaufmann, D., A. Kraay, and M. Mastruzzi. 2011. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues.” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3 (2): 220–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1876404511200046.Search in Google Scholar

Lawrence, R. Z. 2000. Regionalism, Multilateralism, and Deeper Integration. Brookings Institution Press.Search in Google Scholar

Maseland, R., and R. Spruk. 2023. “The Benefits of US Statehood: An Analysis of the Growth Effects of Joining the USA.” Cliometrica 17 (1): 49–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-022-00247-8.Search in Google Scholar

Maudos, J., J. M. Pastor, and L. Serrano. 1999. “Total Factor Productivity Measurement and Human Capital in OECD Countries.” Economics Letters 63 (1): 39–44.10.1016/S0165-1765(98)00252-3Search in Google Scholar

Rivera-Batiz, L. A., and P. M. Romer. 1991. “Economic Integration and Endogenous Growth.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 106 (2): 531–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937946.Search in Google Scholar

Williamson, O. E. 2000. “The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead.” Journal of Economic Literature 38 (3): 595–613. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.3.595.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/rle-2024-0056).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The Impact of Online Dispute Resolution on the Judicial Outcomes in India

- Legal Compliance and Detection Avoidance: Results on the Impact of Different Law-Enforcement Designs

- Women in Piracy. Experimental Perspectives on Copyright Infringement

- Is Investment in Prevention Correlated with Insurance Fraud? Theory and Experiment

- Bias, Trust, and Trustworthiness: An Experimental Study of Post Justice System Outcomes

- Do Sanctions or Moral Costs Prevent the Formation of Cartel Agreements?

- Efficiency and Distributional Fairness in a Bankruptcy Procedure: A Laboratory Experiment

- Soft Regulation for Financial Advisors

- Conciliation, Social Preferences, and Pre-Trial Settlement: A Laboratory Experiment

- The Impact of Tax Culture on Tax Rate Structure Preferences: Results from a Vignette Study with Migrants and Non-Migrants in Germany

- Perceptions of Justice: Assessing the Perceived Effectiveness of Punishments by Artificial Intelligence versus Human Judges

- Judged by Robots: Preferences and Perceived Fairness of Algorithmic versus Human Punishments

- The Hidden Costs of Whistleblower Protection

- The Missing Window of Opportunity and Quasi-Experimental Effects of Institutional Integration: Evidence from Ukraine

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The Impact of Online Dispute Resolution on the Judicial Outcomes in India

- Legal Compliance and Detection Avoidance: Results on the Impact of Different Law-Enforcement Designs

- Women in Piracy. Experimental Perspectives on Copyright Infringement

- Is Investment in Prevention Correlated with Insurance Fraud? Theory and Experiment

- Bias, Trust, and Trustworthiness: An Experimental Study of Post Justice System Outcomes

- Do Sanctions or Moral Costs Prevent the Formation of Cartel Agreements?

- Efficiency and Distributional Fairness in a Bankruptcy Procedure: A Laboratory Experiment

- Soft Regulation for Financial Advisors

- Conciliation, Social Preferences, and Pre-Trial Settlement: A Laboratory Experiment

- The Impact of Tax Culture on Tax Rate Structure Preferences: Results from a Vignette Study with Migrants and Non-Migrants in Germany

- Perceptions of Justice: Assessing the Perceived Effectiveness of Punishments by Artificial Intelligence versus Human Judges

- Judged by Robots: Preferences and Perceived Fairness of Algorithmic versus Human Punishments

- The Hidden Costs of Whistleblower Protection

- The Missing Window of Opportunity and Quasi-Experimental Effects of Institutional Integration: Evidence from Ukraine