Abstract

Cartel decisions are made by managers. These decisions result in an increase in company earnings at the expense of the earnings of a third party, typically consumers or business partners. Using laboratory experiments, this article studies the behavioral foundations of individuals’ willingness to engage in a cartel, in a context in which engaging in such agreements increases the cartelists’ earnings, but reduces the earnings of a third participant. This reduction in earnings is a loss for the third participant but it can also be seen as a moral cost for the cartelists. In addition, the impact of different sanctions schemes–monetary, leniency, compliance, and exclusion–is investigated. The results show that forced compliance and exclusion sanction schemes are more effective deterrents than monetary and leniency sanction schemes. These results are robust to varying levels of moral costs and of probabilities of detection and fines. Although the impact of moral costs is statistically significant, it is limited in magnitude, showing that participants are more sensitive to the monetary gains associated with cartel agreements than to the reduction in earnings imposed on the third participant. Finally, being a woman and being risk-averse is associated with a lower propensity to engage in such agreements.

1 Introduction

Cartels are formed when individuals, typically managers, jointly decide to engage in anti-competitive price-fixing. In most cases, as for the truck cartels condemned by the European commission in 2016,[1] these practices entail an agreement to charge higher prices than those that would have been set by a competitive marketplace, and these higher prices lead to a reduction in earnings of a third party, for instance consumers in Business-to-Consumers settings, or business partners in Business-to-Business settings. These decisions have been initially studied within the utilitarian framework (see Becker 1968), which argues that a firm is more likely to engage in illicit practices when the gains derived from these practices exceed their costs. The expected cost associated to cartels is the sanction multiplied by the probability of detection.

Nonetheless, cartels’ determinants are complex and they have been the object of further studies. First, developments on the role of sanctions have highlighted that the difficulty to disincentivize cartel practices is influenced by the fact that the interests of managers may not be aligned with those of shareholders (see Buccirossi and Spagnolo 2008; Jensen and Meckling 1976). Recent works on remuneration schemes show that they can generate perverse economic incentives, as well as psychological and social responses that motivate counterproductive behaviors such as fraud (see Larkin and Pierce 2016) and anticompetitive practices (see Fonseca et al. 2022; Fleckinger et al. 2013). While some works show that rewards can lead to more cheating (see Parasuram et al. 2017), the relationship between reward and dishonest behavior is complex as individuals display internal costs of illicit behavior or dishonesty.[2] In addition to the role of incentives and rewards, other works have investigated the role of psychological and behavioral characteristics in explaining cartel decisions (see Bodnar et al. 2023).[3] Cartels’ decisions can be analyzed as a cooperation dilemma in an oligopoly setting, here a duopoly, in which insiders (typically managers, or business owners) decide to form a cartel, which may harm outsiders, typically consumers. If insiders overcome their dilemma and collude, this inflicts harm on the opposite market side (consumers or business partners).[4]

Cartel decisions are determined by many factors, which complicates the analysis of the effectiveness of sanctions. In that perspective, laboratory experiments can highlight the most effective measures to deter these practices. Recent experimental works show that fines are effective in deterring collusive behavior (see Bigoni et al. 2015; Chowdhury et al. 2018), but they mainly test basic sanctions. Our article aims at completing this literature by first testing more sophisticated sanction schemes, and second including the effect of a moral cost (in the form of a loss inflicted on others) on the propensity of individuals to engage in cartel practices.

Using laboratory experiments, our paper combines two strands of literature by studying financial and behavioral determinants of cartels, in a context in which individuals decide to engage in cartels that, if jointly agreed, will increase their earnings at the expense of the earnings of a third party. This reduction in earnings for the third party can be seen as a moral cost for the cartelists and as a loss for the third party. In Business-to-Consumers settings, third parties are typically consumers. In Business-to-Business settings, they are typically partners, such as direct buyers. In addition, the sanctions mechanisms are diversified and enriched, including recent tools developed by competition policy. The objective of this investigation is therefore to experimentally test the propensity of two individuals to form a cartel with the intent of increasing their earnings (if not detected) at the expense of another individual, while simultaneously facing sanctions aimed at deterring such behavior, particularly recent ones such as exclusion and forced compliance.

This paper fills a double gap in the literature as the question of the impact of the moral cost of cartelists remains understudied in a sanctions framework, and as innovative sanctions schemes (such as forced compliance and exclusion) have not yet been tested. More precisely, the paper addresses two research questions.

First, the paper studies the impact of different sanctions schemes on the propensity to collude. Previous research has explored the role of fines and leniency on cartels formation. While these previously studied anti-cartel sanctions are prominent in antitrust policies, other types of sanctions, such as compliance programs and exclusion schemes, which rely mainly on disqualification or dismissal from one’s employment, have emerged. To cover this extended range of sanctions, this paper examines in a controlled environment the impact of four types of sanctions on cartels’ decisions. In the experiment, monetary sanctions are implemented via a fine in case of a detection; leniency is implemented via the option to report an agreement after agreeing on its formation; compliance is implemented via the removal of the cartel possibility in the period following a detection; and exclusion is implemented via the removal of both decisions options in the period following a detection. Although monetary sanctions and leniency have been studied in previous experimental works – reviewed in subsection 3.1. -- the temporary removal of one decision (forced compliance) and the removal of both options (exclusion or disqualification), are two new experimental manipulations.

Second, in addition to sanctions, the paper investigates the impact of the size of the reduction in earnings imposed on a third party (which is varied in order to check the robustness of the results) on the propensity to choose a cartel agreement. Therefore, it allows us to study cooperation in the presence of a negative externality, but in a framework in which cartels can be sanctioned if detected (which is closer to a real situation).

Thus, the paper examines the combined influence of sanction schemes on cartel decisions, as well as the impact of the size of the loss imposed on a third party. The experiment relies on a between-subject design to measure the impact of the size of the loss and a within-subject design to measure the impact of sanction schemes, the probability of detection and the fine. Additionally, we control for two individual level characteristics, which are gender and risk aversion.

The paper starts with the experimental design. Section 3 reports the related literature and hypotheses. The results are examined in Section 4. Section 5 concludes.

2 Experimental Methodology

2.1 The Experiment

2.1.1 Summary

The experiment involves two roles: Type 1 and Type 2 participants, grouped into trios consisting of two Type 1 participants and one Type 2 participant. Type 1 participants make simultaneous decisions across various environments. In these environments, they can either agree to reduce competition, which increases their profits but reduces Type 2 earnings, or opt for a competitive strategy, which does not increase their earnings nor reduce Type 2 earnings. Both Type 1 participants need to choose the anti-competitive strategy for the cartel to be implemented. Type 2 participants completed a questionnaire. Type 1 participants made a total of 96 decisions across different environments. Each environment is defined by a probability of detecting potential agreements and a sanctions framework, which includes fines and other sanctions upon detection. Information about the decision periods and environments was displayed in a banner at the top of the decision-making interface. After each decision was completed, participants were informed of their earnings, along with any detections and sanctions incurred.

2.1.2 Decision

Participants are matched randomly in groups of three individuals composed of two Type 1 participants and one Type 2 participant. Individuals remained in the same group for the whole experiment and the roles are fixed for the whole experiment. Type 1 participants have to choose between two possible choices: Choice A and Choice B. Type 1 participants make their choices simultaneously and without communication. Choice A (competitive strategy) grants each Type 1 participant 10 experimental currency units (hereafter ECUs). Choice B (cartel strategy) grants each Type 1 participant 20 ECUs if both Type 1 participants choose to collude. If only one Type 1 participant chooses the collusive strategy (Choice B) and the other chooses the competitive strategy (Choice A), then competition (Choice A) is implemented for both participants. As Choice A corresponds to a competitive strategy, that leads to lower earnings compared to the cartel agreement. Choice B corresponds to the collusive strategy (cartel) that leads to higher earnings compared to a competitive strategy, but the participant is exposed to sanction schemes. A cartel is formed if both Type 1 participants choose B. If Choice A is implemented (compete), Type 2 participants each earn 10 ECUs. If Choice B is implemented (collusion), Type 2 participants earn 10 – the “loss” (i.e. the “moral cost”, a loss that is imposed on the Type 2 participant). For simplicity, when referring to the reduction in earnings for the Type 2 participant, we will use the term “loss” and when referring to the psychological cost for Type 1 participants, we will use the term “moral cost”.

2.1.3 Level of Loss – Varied in a Between-Subject Design

Using a between-subject design, four levels of losses, which are reductions in earnings imposed on the Type 2 participants due to the cartel-type agreements, are tested in separate experimental sessions. The four levels of losses are as follows: A loss of 0 leading to earnings of 10–0 = 10 ECUs for Type 2 participants (i.e. a baseline with “no loss” and thus “no moral cost” for Type 1 participants), a loss of 3 leading to earnings of 10–3 = 7 ECUs for Type 2 participants (a “low loss” environment with “low moral cost” for Type 1 participants), a loss of 7 leading to earnings of 10–7 = 3 ECUs for Type 2 participants (a “high loss” environment with “high moral cost” for Type 1 participants) and a loss of 10 leading to earnings of 10–10 = 0 ECU for Type 2 participants (a “full loss” environment with “full moral cost” for Type 1 participants). Type 2 participants are informed of the decisions that Type 1 participants have made. In the experiment, Type 2 participants do not make any decisions, but they answer a survey on their attitudes toward competition policies and firms’ practices, and they are informed of their earnings (Table 1).

Payoff matrix and the impact of the experimental design on the participants’ earnings.

| Earnings if at least one | Earnings if both Type 1s | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 chooses A | choose B (collude): agreement | |||

| (compete): No agreement | ||||

| Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 1 | Type 2 | |

| 10 | 10 | Detection | 20 each | Between-subject design: earnings of 10, 7, 3 or 0, depending on the size of the loss (0, 3, 7 or 10 respectively). |

| No detection | Within subject-design: penalty which depends on the sanction scheme, and the level of the fine. | |||

2.1.4 Types of Sanction Schemes, Probability of Detection and Level of Fines – Implemented in a Within-Subject Design

An agreement may only be detected during the period in which it is formed. If a cartel-type agreement is formed but not detected, no sanction is implemented. An agreement is sanctioned if detected. In the experiment, decisions are made in four sanction scheme environments, which are implemented in a within-subject design. Thus, all participants face all sanction schemes. These sanction schemes correspond to the four main sanction schemes that are used in antitrust policies.

The Monetary sanction scheme (labeled “Basic” in the instructions) corresponds to simple monetary fines. In the experiment, if a cartel is formed and detected, a monetary fine is implemented.

The Compliance sanction scheme (labeled “Basic + Compliance” in the instructions) tests the impact of being under threat of greater surveillance on the propensity to engage in cartel decisions. In the experiment, if a cartel is formed and detected, a fine is implemented and, in addition, Choice B (collusion) is no longer available in the period following the detection (in that following period, the earnings of Type 1 participants are 10 ECUs and the earnings of Type 2 participants are 10 ECUs).

The Exclusion sanction scheme (labeled “Basic + Exclusion” in the instructions) measures the impact of being under threat of temporary incapacitation on the propensity to engage in cartel practices. In the experiment, if a cartel is formed and detected, a fine is implemented and, in addition, the ability to take a choice is no longer available in the period following the detection (in that following period, the earnings of Type 1 participants are 0 ECU and the earnings of Type 2 participants are 10 ECUs).

The Leniency sanction scheme (labeled “Basic + Leniency” in the instructions) aims at capturing the effect of leniency programs on cartel formation. In the experiment, if a cartel is formed (and before any detection), Type 1 participants are given the possibility to denounce the cartel-type agreement.

If no Type 1 participant denounces the cartel-type agreement and if the cartel is detected, a fine is implemented.

If only one Type 1 participant denounces the agreement, this Type 1 participant does not pay his/her fine, but the other Type 1 participant does.

If both Type 1 participants denounce the agreement, the fastest participant to denounce the agreement gets his/her fine canceled. The other Type 1 participant must pay his/her fine.

All decisions are made in two probability regimes: in a low/high probability environment (1/10 or 9/10) and in a medium low/medium high probability environment (1/3 or 2/3). The probability regimes are presented in reverse order to control order effects. In each probability regime, if detected, there are three possible types of fines. There is a low fine of 5 (leading to earnings for Type 1 participants of 20–5 = 15), a medium fine of 10 (leading to earnings for Type 1 participants of 20–10 = 10) and a high fine of 15 (leading to earnings for Type 1 participants of 20–15 = 5). In each probability regime, there are a total of 2 probability regimes * 3 fines * 4 sanction schemes = 48 decision environments (Appendix B).

2.1.5 Repetition of Decisions

In addition, in order to test the robustness of the results by controlling for the impact of repetition and the impact of knowing versus not knowing the environment that will be dismissed in the Compliance and Exclusion schemes, each environment is repeated once. In these two schemes, when making the decision the first time in each environment (labeled ‘Repetition 1/2’ in the experimental interface), they know the environment that may be dismissed. When making the decision the second time (labeled ‘Repetition 2/2’), they do not know the environment in which the possible sanctions of the Compliance and Exclusion scheme will take place. This doubling of the decision allows us to check the robustness of the result to the varying levels of information available to Type 1 participants. Therefore, in total, Type 1 participants make 48 × 2 = 96 decisions. The repetition was meant to take account of the dissuasion power of Exclusion and Compliance in an uncertain environment (the second time, Type 1 is not sure of the following sanction environment). This limited uncertainty (as they know the overall sanction scheme) on round 2 was also made to be more realistic in a market setting. As under Compliance or Exclusion, managers do not exactly know what they may lose if detected (as an opportunity cost). Disqualification and its actual effects are ambiguous as it depends on the career that the managers would have had without these sanctions. Some CEOs actually may suffer high costs or sometimes face very low opportunity costs after exclusion, which can be illustrated by the ease with which those convicted of antitrust offences in the US find re-employment following prison (Stephan 2010).

The design allows us to pull into one experiment, using a within-subject design, each of the four sanction schemes. By doing so, it combines the monetary scheme and the leniency sanction scheme that had been studied in previous works, as well as exclusion and compliance. In addition, the impact of the level of loss is studied using a between-subject design, resulting in four cohorts of participants who face the same sanction schemes but at different levels of losses.

The experiments were carried out at LEEP (http://leep.univ-paris1.fr/accueil.htm), the experimental economics laboratory of the University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and the Paris School of Economics. Participants were drawn from a database of volunteer participants. Their participation fee was 6 euros and their additional earnings varied according to their decisions and/or the decisions of the participants in their group. In total, they earned on average 16.78 euros (st. dev. = 1.34). Sessions lasted about 1 h and 15 min. In total 288 individuals participated in the experiments, 192 participants held Type 1 participant positions, and 96 participants held Type 2 positions. This results in 192 participants, 96 decisions each, leading to 18,432 observations in total, and as there are four levels of loss, each level of loss is documented by 4,608 observations. The instructions are displayed in Appendix B.

2.2 Game Structure and Matching Procedure

Experimental studies have been carried out to better understand collusive mechanisms and the effect of competition policies.[5] Previous researchers have mainly studied the effect of communication, price announcements and leniency on the formation and stability of cartels and price levels.[6]

Most experiments on cartels have been conducted with Bertrand games with the possibility to communicate before the price choice, and have therefore been focused on collusion via the level of price generated after non-bidding agreements.[7] Recently, Engel and Zhurakhovska (2014) and Haucap et al. (2024) have used a standard symmetric two choices, one-shot, prisoner’s dilemma. Some studies, however, limit the ability to communicate.[8] Moreover, Hamaguchi et al. (2009) [9] do not rely on a Bertrand game. In their study, participants are not given a choice on whether or not they want to participate in a cartel, but they are offered possibilities to denounce it or not. This framework allows them to focus on the determinant of individual decisions to blow the whistle.

Our experiment also relies on a limited market environment. In our setting, participants must decide whether or not to form a cartel. Our work does not aim at documenting the level of collusion (measured via the price increase) but to focus on the effect of sanctions schemes and moral costs on the individual decision to form a cartel. We study variations of sanctions schemes and moral costs that cannot be cleanly introduced in a market game, as the returns from a cartel agreement have to be held constant in the experiment, which is the case in our design. Moreover, to focus on the individual determinants of a cartel decision, in our setting, participants cannot directly communicate before choosing to collude or not.[10]

Matching procedures in the above-cited articles rely on fixed matching. This design best captures the features of actual markets, in which firms interact with each other repeatedly in the same market.[11] But in some articles, the fixed matching is altered in the course of the experiment. Chowdhury and Crede (2020) allocate participants who interacted with the same two other participants throughout the experiment, apart from a treatment in which participants at some pre-announced point in time are rematched into new groups. In Bigoni et al. (2015) there is a rematching procedure[12] (at the end of each period, participants were rematched with the same competitor with a probability of 85 %).

To match and contribute to the preexisting literature, our experiment relies on fixed matching.

3 Related Literature and Hypotheses

This article analyzes the efficacy of sanction schemes in experimental settings while accounting for the effect of moral cost on cartel decisions and formation, and while controlling for individual traits. This section reviews the literature related to the experimental design and lays out the hypotheses that are tested.

3.1 The Influence of Sanctions Schemes on Collusion and Cartels

The literature on economics of crime has highlighted the role of sanctions and detection to deter crime. Following the pioneering work of Gary Becker (1968), the economics of crime framework allows us to analyze a firm’s decision to engage in a cartel: a firm has an incentive to form a cartel when the illegal gain resulting from this practice exceeds its expected cost, which depends on both the sanction (fine) and the probability of detection. Therefore, crime deterrence relies on fines and detection (see e.g. Connor and Lande 2012, for a summary of this literature). Also, the corporate governance approach highlights the existence of a possible divergence of interests between shareholders and managers, which argues for penal sanctions (prison or disqualification). A large body of literature has therefore addressed managerial and policy issues, from the optimal level of fines to the appropriate form of the sanction between fine and imprisonment, which raises the individual versus corporate liability issue (see Buccirossi and Spagnolo 2008; Polinsky and Shavell 2000). Concerning leniency, the theoretical literature suggests that such an approach enhances cartel instability and could deter cartel formation (see Cooter and Garoupa 2014 for an overview, and Spagnolo 2008 for specific applications[13]). Finally, other individual factors (risk appetite or aversion, psychological aspects or ethical behavior) may influence the individual’s choice of whether or not to engage in cartel practices (see Combe and Monnier 2020; Stucke 2011).

As regards experimental studies on cartel deterrence, Apesteguia et al. (2007) test a fine equal to 10 % of the revenue, with positive probability, and study the effect of leniency and bonus (in which firms are rewarded with a share of the fines paid by other firms). In the presence of leniency, they find that prices are lower but that the rate of cartel formation remains high. On the other hand, Hinloopen and Soetevent (2008) find that leniency reduces the rate of cartel formation.[14] In Hamaguchi et al. (2009), players who reported the information can receive a partial exemption, full exemption or reward. The reward of whistleblowers has been found to help deter collusive practices. Bigoni et al. (2012, 2015) demonstrate that fines have a significant deterrent effect. Their results also suggest a strong cartel deterrence potential for well-run leniency and reward schemes.[15] Chowdhury et al. (2018) conduct an experiment involving two combinations of fines and detection probabilities. They find that in the absence of leniency, the probability of detection and fines are substitutable. Last, concerning the influence of private claims and penal sanctions, Bodnar et al. (2023) run an experiment to study if private damage claims against cartels may have negative effects on leniency (as whistleblowers have no or only restricted protection against private third-party damage claims). This may stabilize cartels. In their experimental setting, firms choose whether to join a cartel, may apply for leniency afterwards, and then potentially face private damages. They find that the implementation of private damage claims reduces cartel formation but makes cartels more stable. Fonseca et al. (2022) compare legal regimes in which firms are fined with legal regimes in which managers are prosecuted. Their results suggest that there is less collusion in legal regimes in which managers are prosecuted.

Our experiment therefore contributes to the literature in the following way. First, it focuses on individual sanctions as participants’ earnings are directly impacted by their collusive behavior in all our sanctions schemes. Moreover, it includes a greater variability of fines and detection probabilities, which allows us to cleanly assess the role of these determinants. Besides leniency, the experiment adds two sanctions schemes which have not been evaluated in the laboratory for cartels: forced compliance[16] and exclusion (in the form of temporary disqualification). Evidence on the effect of exclusion with reintegration –which resembles our implementation – has been collected in other type of cooperative games.[17]

Hence, our experimental setting aims at testing if alternative and/or stronger sanctions lower the propensity to choose the cartel. In line with the pre-existing experimental literature, we hypothesize that the effects of the two additional sanction schemes – forced compliance and exclusion – are associated with a lower propensity to choose the cartel choice.

H1

The stronger the sanction schemes, the lower participants’ propensity to choose the cartel. The propensity to choose the cartel is highest in the monetary sanction scheme, followed by leniency, compliance and finally, exclusion.

3.2 The Role of Moral Costs in Cartel Decisions and Formation

Social responsibility in a markets framework has been studied in the literature. Bartling et al. (2015) find a persistent preference among many consumers and firms for avoiding negative social impact in the market, reflected both in the composition of product types and in a price premium for socially responsible products. Previous research has also shown that market framing may increase the likelihood of unethical behavior.[18] In an experimental framework, Kirchler et al. (2016) [19] study how different interventions influence the degree of moral behavior when subjects make decisions that can generate negative externalities on third parties. Sutter et al. (2020) [20] further explain that market framing increases the acceptability of unethical behavior and that it is associated with a dilution of responsibility.

Moreover, behavioral economists have studied the conditions under which participants engage in reducing other participants’ earnings if it comes at the expense of their own earnings. The “money burning” experiment of Zizzo and Oswald (2001) shows that participants are willing to pay to reduce other participants’ earnings (see also the joy-of-destruction game introduced by Abbink and Sadrieh 2009, and its related literature[21]).

In the case of cartel decisions, Stucke (2011) stresses that the fact that damages inflicted on third parties are not always visible to the managers involved in the cartel may undermine their sense of responsibility and their moral cost. Concerning moral costs, cartel settings have the particularity to place cartelists in a situation in which they have to arbitrage between their own profit and fairness towards third parties who suffer from the cartel.[22] Last, Engel and Zhurakhovska (2014) study collusion in oligopoly inflicting harm on the opposite market side. In their experiment, they have a Baseline with just two active players, and three treatments with an additional passive outsider who is negatively affected by insiders choosing a cooperative move. In their experiment, harm on outsiders significantly reduces the conditional cooperation of insiders. They explain this result by guilt aversion (which is greater if the active insiders increase their own payoff at the expense of the outsider). Haucap et al. (2024) also experimentally analyze cooperation in a prisoner’s dilemma game, with a passive third party that may be harmed when active players mutually cooperate. Applying a within-subjects setting, they compare cooperation under anonymity and social information. Results show that the presence of a negative externality particularly affects guilt-averse women, who cooperate less often independently of the degree of information they receive.

Previous studies show that the reduction in earnings imposed on a participant may contribute to reducing the propensity to choose the cartel option, but the loyalty-fairness dilemma could mitigate this effect. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2

The presence of a moral cost in the form of a reduction of earnings imposed on another participant lowers slightly the propensity to choose the cartel.

3.3 The Role of Individual Traits in Cartel Decisions and Formation

The literature on business ethics examines the role of individuals’ traits as a factor of corporate fraud.[23] Zahra et al. (2005) developed a framework in which individual variables influence the likelihood of corporate fraud. Moreover, risk aversion is also likely to play a role in the choice of individuals. Tan and Yim (2014) show that being more risk-averse decreases the propensity for tax evasion. Bernhardt and Rastad (2016) find that cartelists with high risk aversion collude less. Other studies focus on gender and find that women have a greater aversion to unethical behavior than men (Robinson et al. 2000), that their reasoning is more contextual than men, which includes ethical matters (Van Staveren 2014), and that bribery is more likely to occur when the principal owner is male (Ramdani and Van Witteloostuijn 2012). Experimental studies find that women can be less corrupt than men (Rivas 2013).

As regards cartels, Abate and Brunelle (2022) find that there is a correlation between the maintenance of informal networks based on masculine values and the permanence of cartel practices, thereby demonstrating that gender imbalance constitutes a risk factor for cartel practices. Haucap and Heldman (2023), who investigate the sociology of cartels, obtain that only two of the 156 individuals involved in these 15 cartels were female, suggesting that gender also plays a role for cartel formation. The experimental study by Hamaguchi et al. (2009) also concludes that women are more likely than men to end a cartel by denouncing them through a leniency program. Haucap et al. (2024) experimentally analyze gender differences in cooperation in a prisoner’s dilemma game, with a passive third party that may be harmed when active players mutually cooperate. Applying a within-subjects setting, we compare cooperation under anonymity and social information, as personal characteristics are commonly known in real-life relations. Results show that the presence of a negative externality particularly affects guilt-averse women. No gender difference is found absent negative externalities.

Our experiments contribute to these literatures by documenting the role of two individual traits, i.e. risk attitude and gender. In line with the above-mentioned literature, we hypothesize that:

H3a

Risk-aversion lowers the propensity to choose the cartel.

H3b

Women are less likely to choose the cartel than men.

The following section reports the results.

4 Results

First, we report the effect of sanctions schemes, fines and the probability of detection. Second, we document the impact of the size of the loss imposed on Type 2 participants. Third, the effects of gender and risk aversion are described. The results focus mainly on two output measures, the cartel option and the cartel formation, (labelled cartel agreement) and which is implemented if both Type 1 participants simultaneously choose the cartel choice.

4.1 The Effect of Sanctions Schemes, Fines and Detection Probability

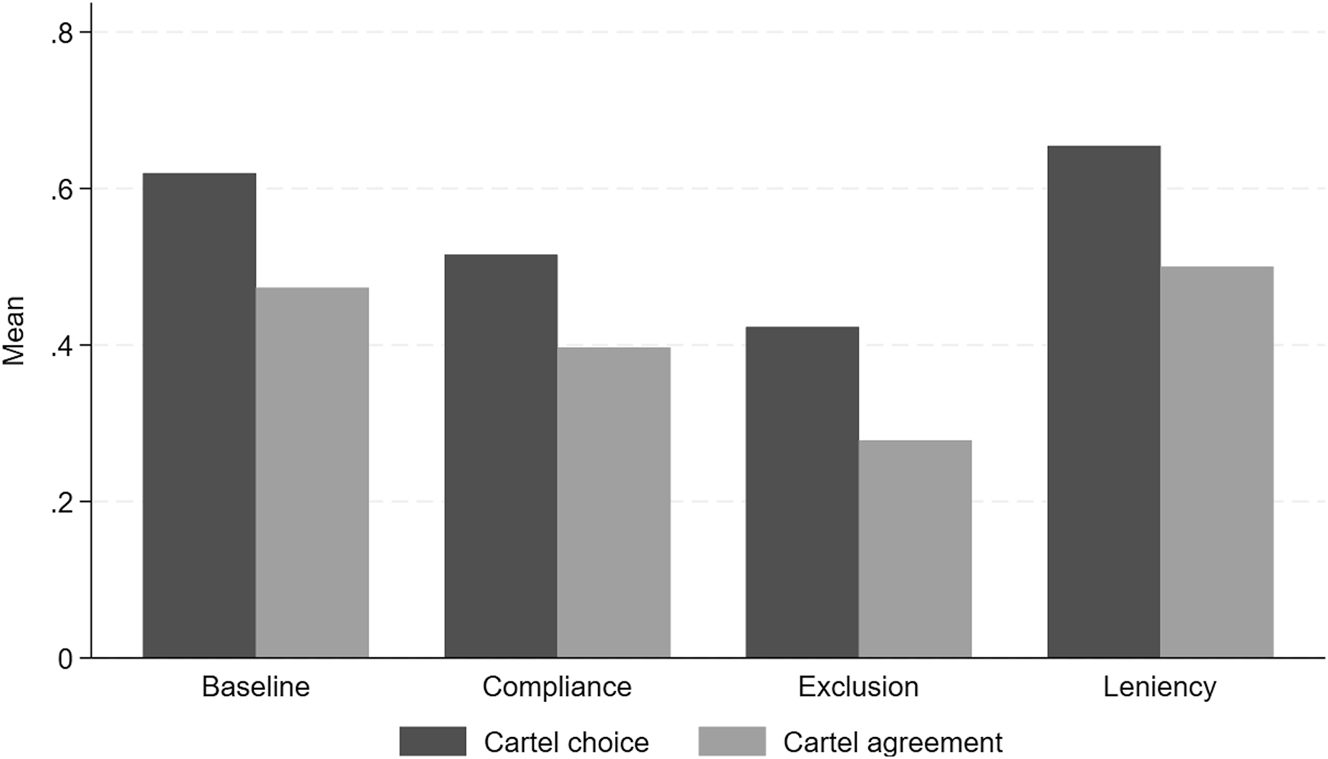

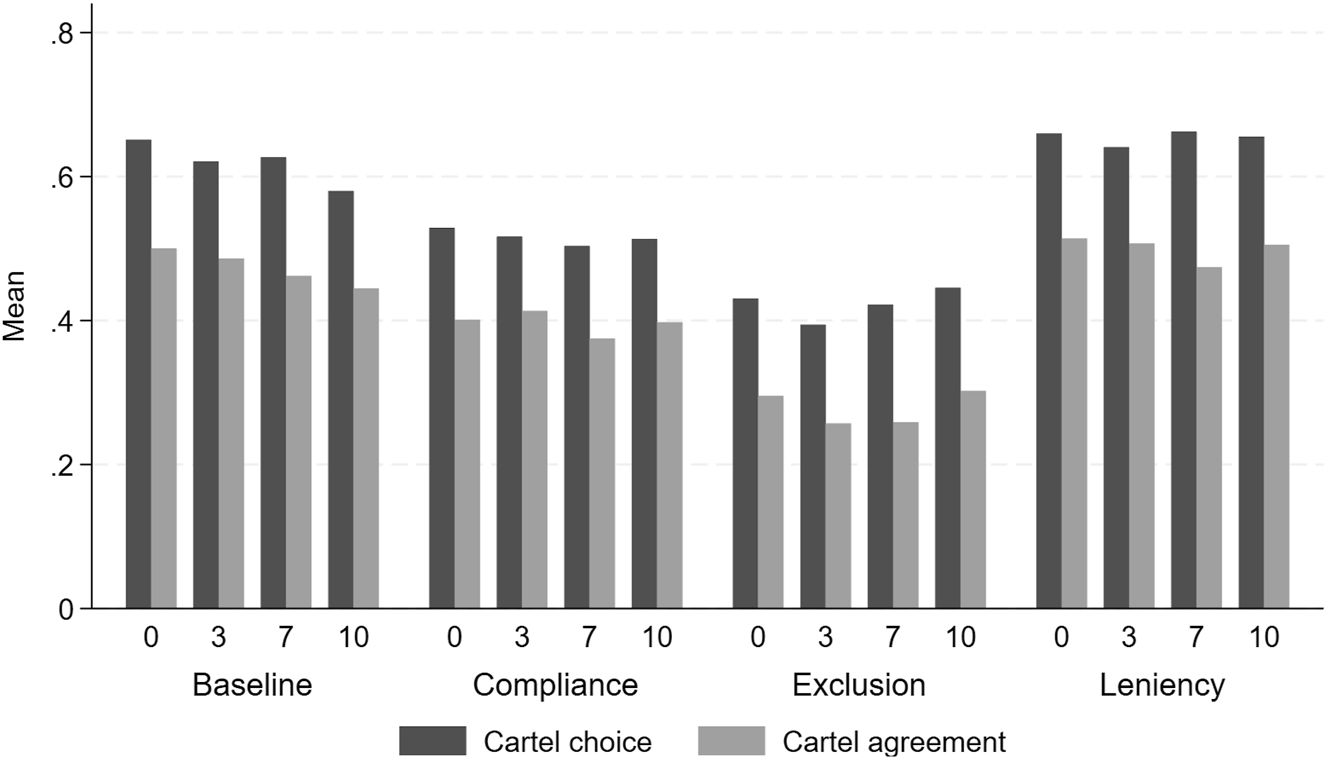

Sanction schemes have strong and persistent effects on cartel choice (option B). Table 2 and Figure 1 report the effectiveness of the four sanction schemes implemented in the experiment. The monetary sanction scheme and the leniency sanction scheme are not very effective in deterring cartel choice, as 61.96 % and 65.45 % of choices are Choices B, in the monetary and the leniency scheme respectively. Compliance is more effective as this proportion drops to 51.54 %. Exclusion is the most effective sanction scheme as this proportion drops to 42.30 %. The proportion of cartel formation in each sanction scheme is coherent with these behavioral results: it is lowest in the exclusion sanction scheme (27.82 %), followed by the compliance sanction scheme (39.67 %) and by the monetary sanction scheme and the leniency sanction scheme (47.31 % and 50 %, respectively). These differences are statistically significant (see Appendix Table A1, Panel a.).

Cartel choice and cartel agreements by sanctions scheme.

| Treatment | Baseline | Compliance | Exclusion | Leniency | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choices | |||||

| Number of competitive choice | 1,753 | 2,233 | 2,659 | 1,592 | 8,237 |

| Number of cartel choice | 2,855 | 2,375 | 1,949 | 3,016 | 10,195 |

| Number of observations | 4,608 | 4,608 | 4,608 | 4,608 | 18,432 |

| Proportion of competitive choice | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.45 |

| Proportion of cartel choice | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.65 | 0.55 |

| Resulting choices implemented | |||||

| Competitive choices implemented | 2,428 | 2,780 | 3,326 | 2,304 | 10,838 |

| Cartel agreements implemented | 2,180 | 1,828 | 1,282 | 2,304 | 7,594 |

| Observations | 4,608 | 4,608 | 4,608 | 4,608 | 18,432 |

| Proportion of competitive outcomes | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.59 |

| Proportion of cartel agreements | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.41 |

Means of cartel choices and cartel agreements by sanctions scheme.

Note that in the compliance and the exclusion sanction schemes, the decrease in cartel choices and in cartel agreements can in part be explained by a mechanical effect. As for compliance, since cartel choice is removed in the period following a detection, participants have fewer instances in which they can choose to collude. As for exclusion, any choice is removed. In the exclusion sanction scheme, cartel choice was selected 45.12 % of the time when it was available. The resulting cartel agreement rate is 29.68 %. The decrease in cartel choices and in cartel agreements remains statistically different from the monetary sanction scheme (with a p-value = 0.0000 in both cases). In the compliance sanction scheme, the cartel choice was selected 59.12 % of the time when this choice was available. The cartel agreement rate is then 45.57 %. The decrease in cartel choices remains statistically different from the monetary scheme (with p-value = 0.0075). However, in this case the decrease in cartel agreements is not statistically different from the monetary sanction scheme. The effectiveness of the compliance sanction scheme is thus more a matter of ex post monitoring than ex ante deterrence, unlike exclusion which is efficient ex ante. The leniency sanction scheme is ineffective in deterring cartels. However, it is found to be effective in terms of detection; under leniency, the rate of detection is 89.58 %.

Result 1 (sanction schemes). Compliance and exclusion are very effective at deterring cartel choices and agreements. Monetary and leniency sanction schemes are less effective at deterring cartel choices and agreements. The leniency sanction scheme leads to an increase in the rate of detection.

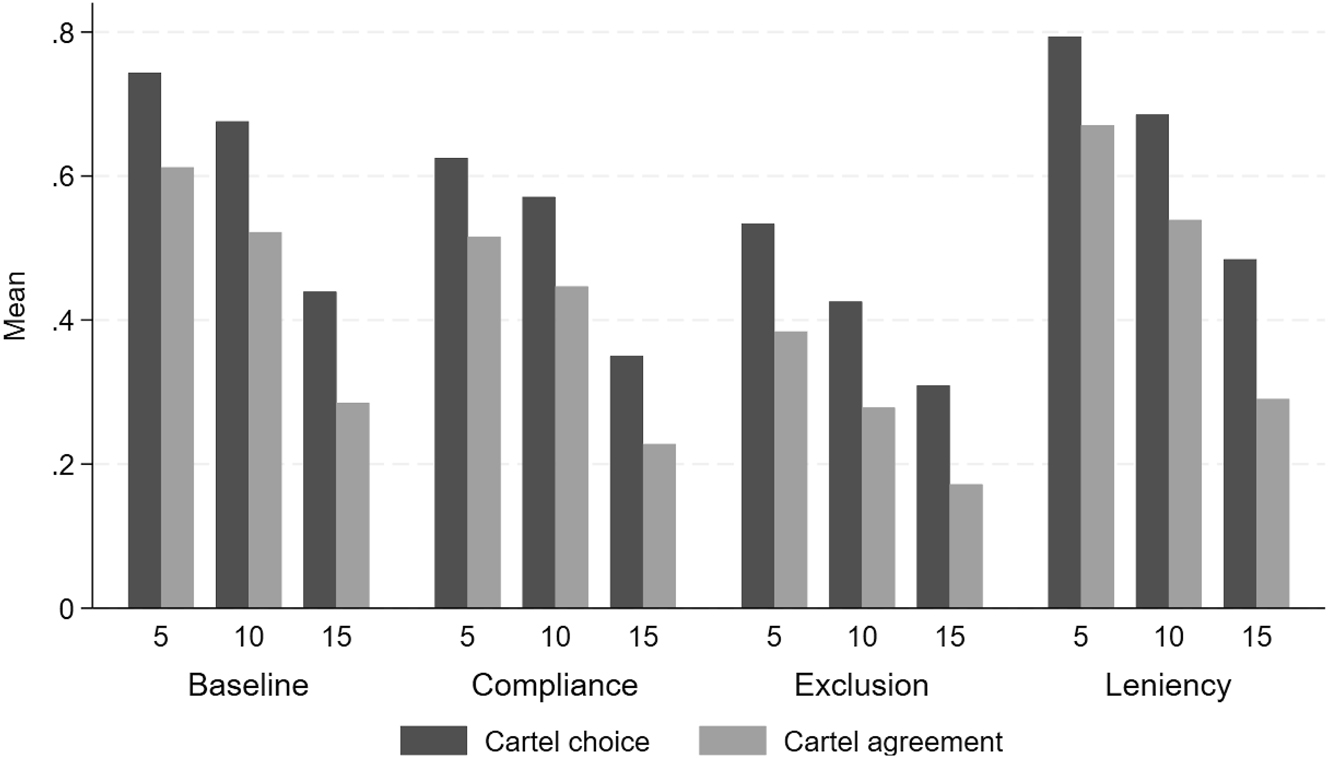

Fines impact behaviors in a consistent fashion as higher fines are associated with lower propensities in both output measures. Table 3 reports the results. The deterrent effect of fines is greater when they are increased from 10 to 15 (15 being the maximum fine level) than when they increase from 5 to 10. These differences in choosing the cartel option and in cartel agreements (which arise when the two Type 1 participants choose to collude) across fines are statistically significant (see Table A1, panel a.). In the monetary sanction scheme, with a low fine (of 5), 74 % of the participants choose the cartel option and the proportion of cartel agreements amounts to 61 %. With a high fine (of 15), these proportions are 44 % and 29 % respectively. These rates are lowest with exclusion and with a high fine (respectively 31 % and 17 %). Overall, by multiplying the amount of the fine by three from 5 to 15, the proportion of cartel agreements is reduced by half. The deterrence effect is highest when the fine exceeds the overprofit of the cartel (which is equal to 10). Cartel overprofit is defined as the cartel profit (20) minus the competitive profit (10). This represents the difference in profits between the cartel and the competitive strategy. These results argue in favor of severe fines. The effect of a fine of 15 is noticeable in the case of the leniency sanction scheme as the reduction in cartel formation (cartel agreements) is comparable to the one in the monetary sanction scheme (Figure 2).

Result 2 (fines). Higher fines are associated with lower propensities to choose the cartel choice and with lower cartel agreements in all sanction schemes, especially when it exceeds cartel overprofit.

Proportions of cartel choice and cartel agreements by sanction type and fine.

| Fine | Cartel choice | Cartel agreement | Cartel choice | Cartel agreement | Cartel choice | Cartel agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 10 | 15 | ||||

| All data | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.24 |

| Baseline | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.29 |

| Compliance | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.23 |

| Exclusion | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.17 |

| Leniency | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.29 |

Means of cartel choices and cartel agreements by sanction type and fine.

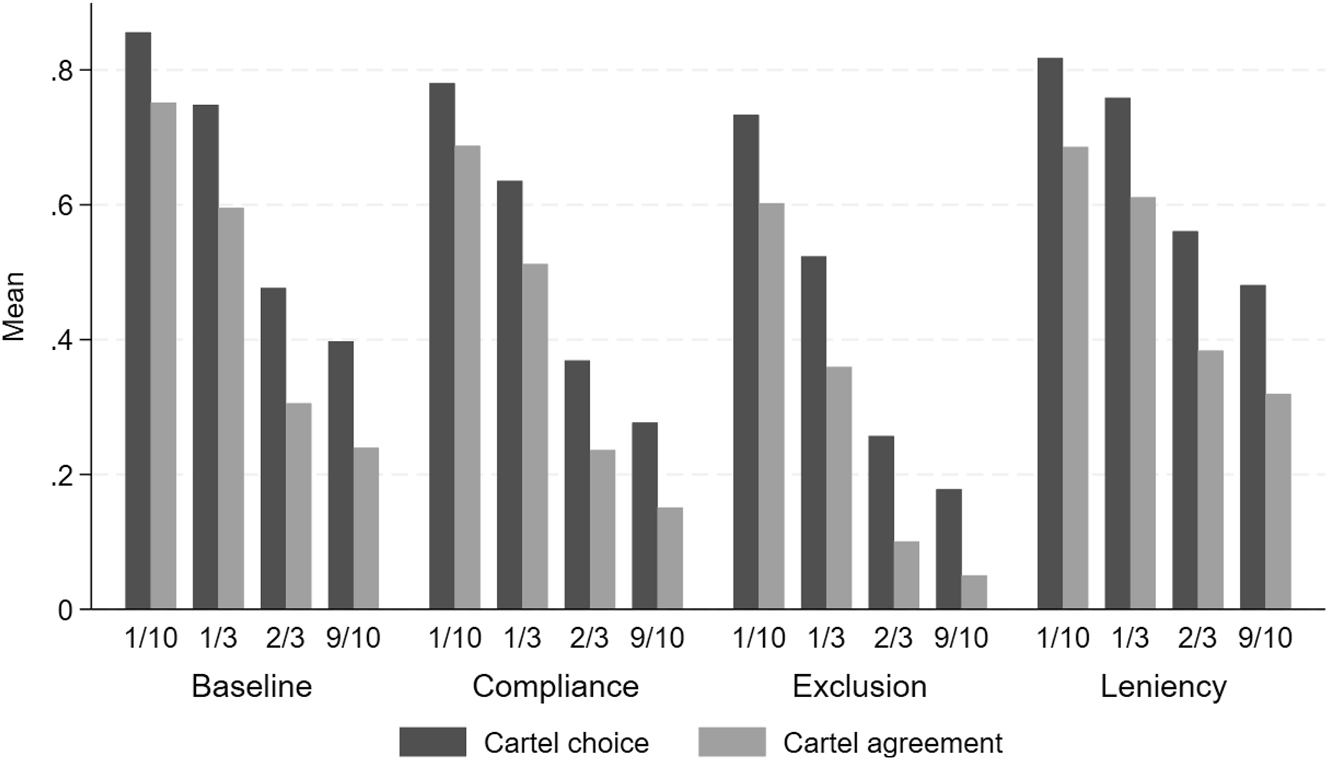

Probabilities of detection have the expected effect in that higher probabilities of detection are associated with a lower propensity to choose the cartel option and a lower proportion of cartel agreements. Table 4, Figure 3 and Panel b. in Table A1 report the results.

Result 3 (probability of detection). High probabilities of detection are associated with lower cartel choices and lower cartel agreements.

Proportions of cartel choices and cartel agreements by sanction and probability of detection.

| Cartel | Cartel choice | Cartel agreement | Cartel choice | Cartel agreement | Cartel choice | Cartel agreement | Cartel choice | Cartel agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability | 1/10 | 1/3 | 2/3 | 9/10 | ||||

| Combined | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.19 |

| Baseline | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.24 |

| Compliance | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.15 |

| Exclusion | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.5 |

| Leniency | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.32 |

Proportions of cartel choice and cartel agreements by sanction and probability of detection.

Table 5 reports a logistic regression of the likelihood of choosing the cartel choice by moral costs, which shows the robustness of the effects of sanction schemes, fines and the probabilities of detection across moral cost conditions, controlling for gender and risk-aversion. These results attest that participants are impacted by these sanctions in a systematic fashion.

Logistic regression of the likelihood of cartel choice by moral costs (marginal effects).

| No loss | Low loss | High loss | Full loss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark – Fine of 5 | ||||

| Fine of 10 | −0.110*** | −0.102*** | −0.108*** | −0.118*** |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.025) | (0.024) | |

| Fine of 15 | −0.359*** | −0.341*** | −0.305*** | −0.353*** |

| (0.036) | (0.045) | (0.044) | 0.044 | |

| Benchmark – Probability of detection (1/9 or 2/3) | – | – | – | – |

| Probability of detection (0.66) | −0.409*** | −0.349*** | −0.328*** | −0.361*** |

| (0.044) | (0.041) | (0.039) | (0.049) | |

| Probability of detection (0.9) | −0.457*** | −0.464*** | −0.399*** | −0.448*** |

| (0.040) | (0.044) | (0.049) | (0.054) | |

| Benchmark – Monetary | – | – | – | – |

| Compliance | −0.160*** | −0.134*** | −0.150*** | −0.084*** |

| (0.027) | (0.024) | (0.023) | (0.034) | |

| Exclusion | −0.282*** | −0.284*** | −0.245*** | −169*** |

| (0.030) | (0.040) | (0.031) | (0.032) | |

| Leniency | 0.011 | 0.026 | 0.045 | 0.097*** |

| (0.036) | (0.031) | (0.041) | (0.032) | |

| Risk aversion (5 or + safe choices = 1) | −0.075 | −0.045 | −0.047 | −0.016 |

| (0.049) | (0.056) | (0.086) | (0.073) | |

| Gender (men = 1) | 0.011 | 0.075 | 0.048 | 0.010 |

| (0.057) | (0.070) | (0.061) | (0.046) | |

| Repetition of the decision in the decision | −0.003 | 0.023 | 0.009 | −0.023 |

| environment | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.014) |

| Probability of cartel choice | 0.587 | 0.553 | 0.565 | 0.560 |

| N | 4,608 | 4,608 | 4,608 | 4,608 |

| Log likelihood | −2,527.544 | −2,574.996 | −2,677 0.853 | −2,609.497 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

-

* p<0.1; ** p<0.05; *** p<0.01.

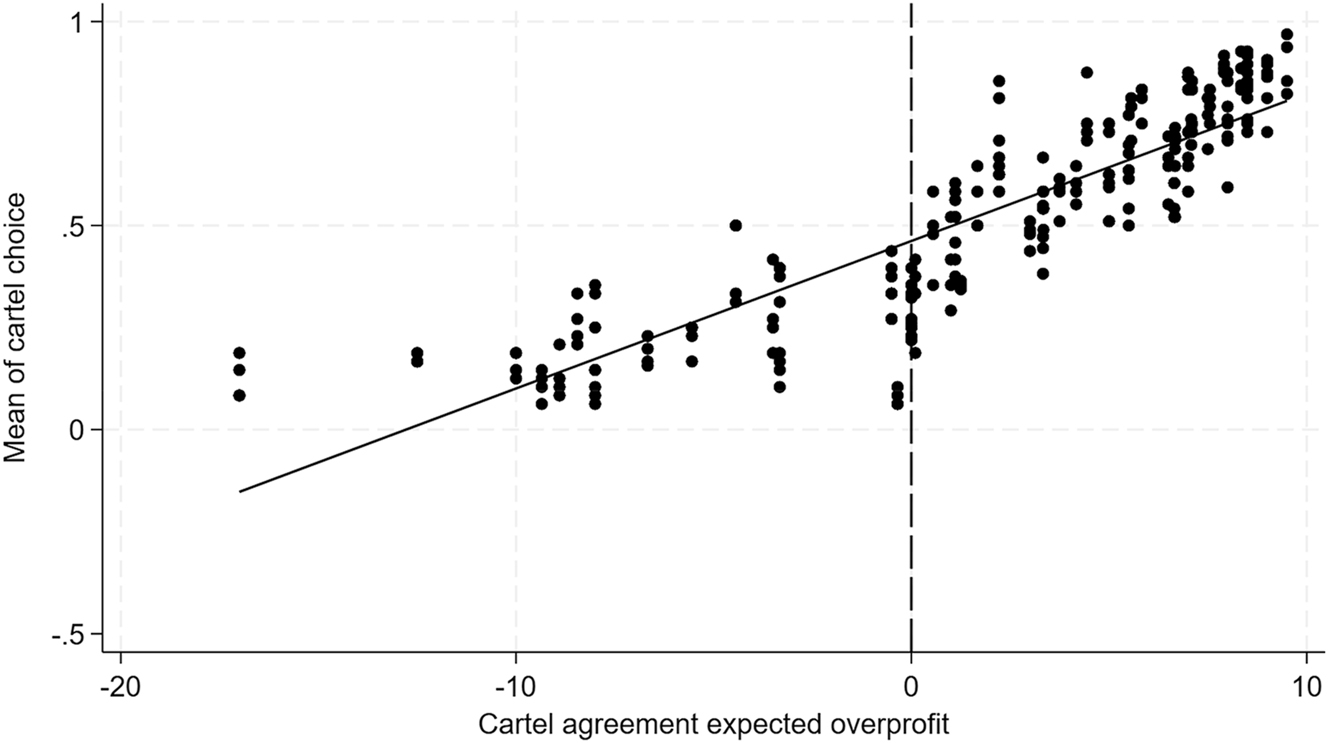

Another way to investigate the impact of sanctions is to study the combination of fines and probabilities of detection, as this combination allows us to measure the sensitivity of participants to the cartel expected overprofit. We define the cartel expected overprofit as the expectation of getting a higher profit than the competitive one. This cartel “overprofit” is therefore defined as the cartel expected profit, minus the competitive profit (this latter being equal to 10).

Table 6 reports the cartel expected overprofit, computed using the following method:

In the Monetary sanction scheme, the cartel expected overprofit is equal to (20 – fine * probability of detection) – 10.

In the Compliance sanction scheme, the cartel overprofit is equal to the expected overprofit in the monetary sanction scheme minus an opportunity cost corresponding to the fact that in case of detection, Player 1 will not be given the option to choose the cartel option in the following round. This opportunity cost is equal to the probability of detection times the cartel expected overprofit in the following round.

In the Exclusion sanction scheme, the cartel overprofit is equal to the expected overprofit in the monetary sanction scheme minus an opportunity cost corresponding to the fact that in case of detection, player 1 will not be given the option to play. This opportunity cost is equal to the probability of detection*(normal competitive profit (i.e. 10) plus cartel expected overprofit in the following round).

In the Leniency sanction scheme, in the absence of denunciation, the cartel expected overprofit is equal to the cartel expected overprofit in the baseline. In the case of denunciation, both players have ex ante the same chance to obtain immunity as it is based on the speed of denunciation. To avoid biasing the computation, the probability that a Type 1 participant will denounce the cartel agreement is set at 50 %.

Cartel expected overprofit amount.

| Fine | Probability of fine | Baseline | Compliance (repetition 1) | Compliance (repetition 2) | Exclusion (repetition 1) | Exclusion (repetition 2) | Leniency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.9 | 5.5 | 0.55 | 1 | −8.45 | −8 | 6.5 |

| 10 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 | −3.5 | −8.9 | −12.5 | 3 |

| 15 | 0.9 | −3.5 | −0.35 | −8 | −9.35 | −17 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 0.66 | 6.67 | 2.22 | 3.33 | −4.44 | −3.33 | 7.08 |

| 10 | 0.66 | 3.34 | 1.11 | 0 | −5.55 | −6.67 | 4.17 |

| 15 | 0.66 | 0 | 0 | −3.33 | −6.67 | −10 | 1.25 |

| 5 | 0.33 | 8.34 | 5.56 | 6.67 | 2.22 | 3.33 | 7.91 |

| 10 | 0.33 | 6.67 | 4.44 | 5 | 1.11 | 1.67 | 5.83 |

| 15 | 0.33 | 5 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 0 | −0.5 | 3.75 |

| 5 | 0.1 | 9.5 | 9 | 9 | 7.55 | 8 | 8.5 |

| 10 | 0.1 | 9 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 7 |

| 15 | 0.1 | 8.5 | 8 | 8 | 6.65 | 7 | 5.5 |

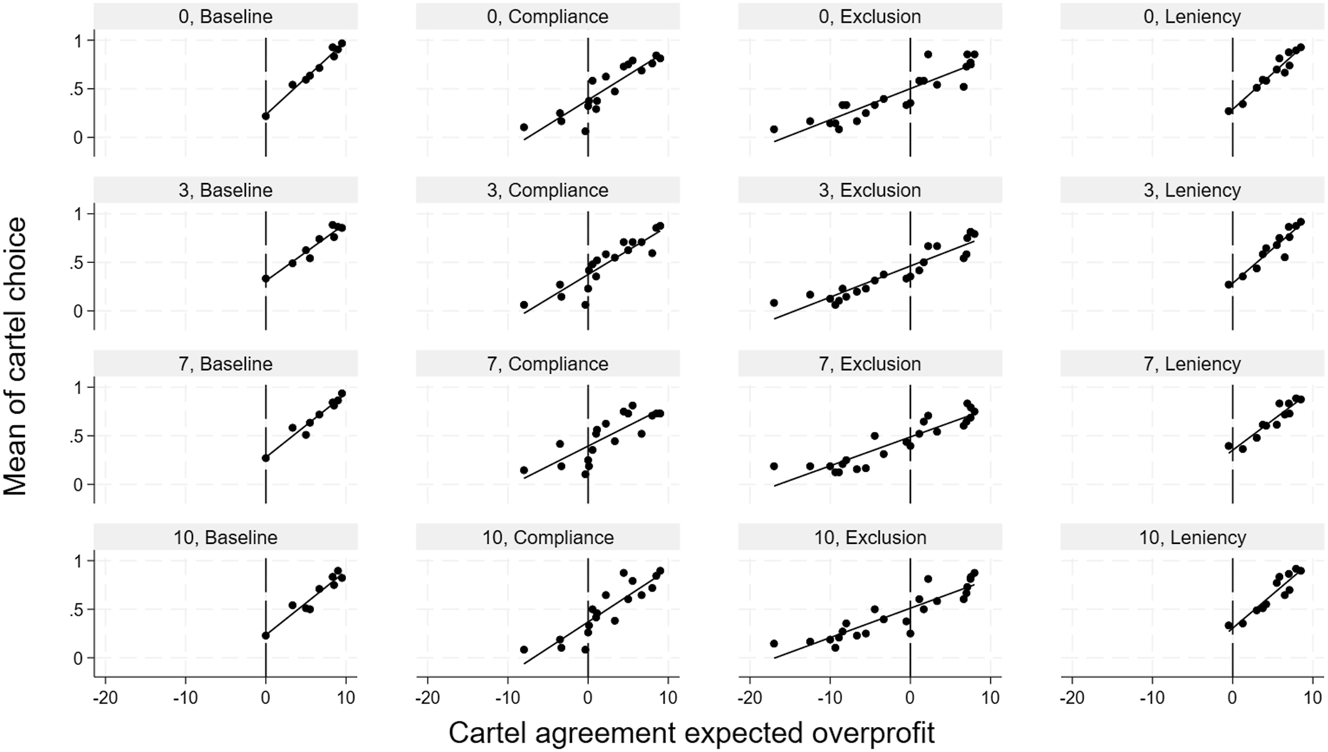

The rationale behind the use of this overprofit is that if Type 1 participants are sensitive to the cartel agreement expected overprofit, they should take Decision B (collusion) when the cartel agreement expected overprofit is greater than zero. Figure 4 reports the propensity to take the cartel choice by sanction type and by Type 2 participant loss. It shows that this propensity to take the cartel choice increases as a cartel agreement’s overprofit increases. The results show that Player 1 participants are more likely to take the cartel choice when the expected overprofit is high.

Result 4 (expected overprofit). Type 1 participants’ propensity to choose the cartel strategy increases as the cartel expected overprofit increases.

Cartel choice by cartel expected overprofit.

4.2 Moral costs

In addition to studying sanction schemes, we can analyze the impact of moral cost. Table 7 and Figure 5 document the proportion of cartel choice by sanction scheme and moral cost. Overall, the results on the effectiveness of sanction schemes are robust to the introduction of varying levels of moral cost: exclusion is the most effective sanction scheme, followed by the compliance sanction scheme, regardless of the level of loss imposed on Type 2 participants.

Proportion of cartel choice by sanction scheme and moral cost.

| Treatment | Baseline | Leniency | Compliance | Exclusion | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cartel choice | No loss (0) | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.57 |

| Low loss (3) | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.54 | |

| High loss (7) | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.55 | |

| Full loss (10) | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.55 | |

| Cartel agreements | No loss (0) | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.43 |

| Low loss (3) | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.42 | |

| High loss (7) | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 0.39 | |

| Full loss (10) | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.41 |

Cartel choice by sanction scheme and moral costs.

The effect of moral costs is statistically significant but small in magnitude, as any loss, i.e. a loss of 3, 7 or 10, imposed on Type 2 participants as opposed to No loss, causes a reduction in the propensity to choose the cartel option of about 2 %. Indeed, the propensity to choose the collusive strategy in any loss condition (loss of 3, 7 or 10) is statistically lower than in the No loss (loss of 0) condition (p-value = 0.0234), indicating that participants take, at least to some extent, moral cost into account. When considering pairwise comparisons, the propensity to choose the cartel option in the Low loss (loss of 3) is statistically lower than in the No loss (loss of 0) condition (p-value = 0.0179). This propensity is also lower in the Full loss (loss of 10) condition compared to the No loss (loss of 0) condition but only at the 10 % level (p-value = 0.065). This leads to Result 5:

Result 5 (moral cost). Moral cost reduces significantly Type 1 participants’ propensity to choose the cartel option but in a magnitude that is small (it causes a reduction in the propensity to choose B of about 2 %).

Table 8 reports the effect of moral cost controlling for fines, probabilities, individual characteristics, and the repetition of the decision by sanction scheme. It documents that, ceteris paribus, the impact of loss remains significant only in the Baseline condition and when there is a full loss imposed on Type 2 participants. This confirms that the effect of moral cost is, relative to the effect of sanctions, small. Note that our setting analyzes moral cost in a between-subject design so we cannot document whether there is a specific relationship between risk-aversion and moral cost.

Logistic regression of the likelihood of cartel choices by sanction schemes (marginal effects).

| Baseline | Compliance | Exclusion | Leniency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark – No loss (0) | – | – | – | – |

| Low loss (3) | −0.044 | −0.018 | −0.047* | −0.029 |

| (0.022) | (0.023) | (0.022) | (0.021) | |

| High loss (7) | −0.033 | −0.036 | −0.005 | −0.004 |

| (0.022) | (0.023) | (0.022) | (0.021) | |

| Full loss (10) | −0.095*** | −0.026 | 0.026 | −0.017 |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.021) | |

| Benchmark – Fine of 5 | – | – | – | – |

| Fine of 10 | −0.089*** | −0.067*** | −0.128*** | −0.139*** |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.018) | (0.018) | |

| Fine of 15 | −0.367*** | −0.326*** | −0.260*** | −0.354*** |

| (0.019) | (0.018) | (0.017) | (0.018) | |

| Benchmark – Probability of detection (1/9 or 2/3) | – | – | – | – |

| Probability of detection (0.66) | −0.390*** | −0.361*** | −0.345*** | −0.272*** |

| (0.018) | (0.016) | (0.013) | (0.019) | |

| Probability of detection (0.9) | −0.465*** | −0.445*** | −0.418*** | −0.354*** |

| (0.017) | (0.015) | (0.013) | (0.018) | |

| Risk aversion (5 or + safe choices = 1) | −0.039* | 0.006 | −0.084*** | −0.019 |

| (0.018) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.017) | |

| Gender (men = 1) | 0.041** | 0.037* | −0.014 | 0.079*** |

| (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.014) | |

| Repetition of the decision in | 0.024 | −0.050** | 0.001 | 0.025 |

| the decision environment | (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.014) |

| Probability of cartel choice | 0.651 | 0.517 | 0.400 | 0.682 |

| N | 4,608 | 4,608 | 4,608 | 4,608 |

| Log likelihood | −2,505.65 | −2,664.78 | −2,604.13 | −2,575.01 |

| p-value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.000 |

-

* p<0.1; ** p<0.05; *** p<0.01.

Result 6 (moral cost and sanction schemes). Ceteris paribus and by sanction scheme, moral cost impacts in a statistically significant fashion the propensity to choose the cartel option in the baseline and when the loss imposed on Type B participants is high.

In addition to the non-parametric tests, it allows us to document that the effect of moral cost is significant only when in the baseline and when the loss is total for Type 2 participants. This suggests that moral cost impacts decisions when the sanction scheme is simple, and when the loss imposed on Type 2 participants is high. Outside these conditions, sanction schemes are the only tools that reduce the propensity to choose the cartel option and that prevent the formation of cartel agreements.

The relationship between the propensity to choose the cartel option and cartel expected overprofit – as reported in Figure 4 – is robust to the varying levels of moral cost, as shown in Figure 6. Figure 6 further shows that dispersion around the cartel agreement expected overprofit is mainly driven by compliance and exclusion, which means that there is higher heterogeneity in behavior when sanctions are strict.

Cartel choice by cartel expected overprofit, sanction scheme, and moral cost.

This leads to Result 7:

Result 7 (influence of sanctions scheme on the cartel overprofit/loss trade-off). Strict sanction schemes, i.e. compliance and exclusion, lead to more heterogeneous behavior than looser sanctions, i.e. baseline and leniency. The impact of the cartel expected overprofit is robust to the introduction of different moral costs.

4.3 Individual Characteristics

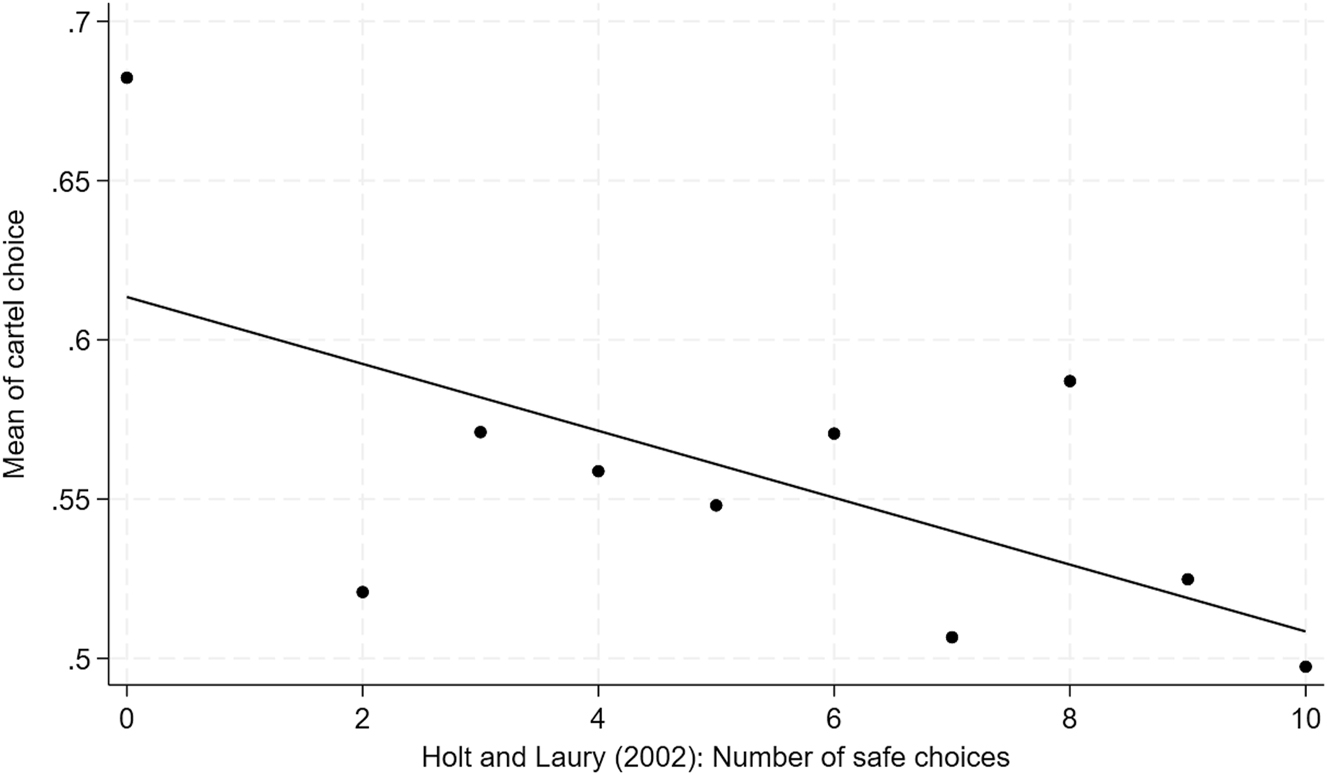

Risk attitudes can affect the decision to form a cartel as it is associated with a lower probability of breaking the law. In terms of risk preference, Figure 7 reports that higher risk aversion is associated with a lower propensity to choose the cartel decision. A logistic regression of the impact of the number of safe choices in the Holt and Laury (2002) task leads to a small (−0.009, with a constant of 0.55 and standard error of 0.001) but statistically significant (p-value = 0.000) decrease in the likelihood to choose collusion. This suggests that risk aversion plays a role in the choice of engaging in such cartel agreement, but that the magnitude of this effect is limited.

Mean of cartel decisions over the number of safe choices in a Holt and Laury (2002).

Result 8 (risk aversion). Risk aversion reduces the propensity to choose the cartel agreement.

The studying of the impact of gender shows that, when using all data, the propensity to choose B is higher among men than women (p-value = 0.000). Men choose the cartel decision 56.72 % of the time, while women choose it 53.76 % of the time. When comparing the individual propensities of men and women participants, the statistical significance disappears in all conditions except the baseline. The results are reported in Table 9.

Cartel choices by sanction scheme and moral cost.

| Women (N = 91) | Men (N = 101) | Comparison (p-value) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | All data | Individual participant average | |

| Combined | 8,736 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 9,696 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.000 | 0.640 |

| Baseline | 2,184 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 2,424 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.044 | 0.033 |

| Leniency | 2,184 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 2,424 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.000 | 0.692 |

| Compliance | 2,184 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 2,424 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.062 | 0.942 |

| Exclusion | 2,184 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 2,424 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.665 | 0.953 |

Result 9 (gender). Men are found to have a higher propensity to choose the cartel option.

5 Discussion and Findings

In this article, we investigate the determinants of individual cartels deterrence and, in particular, the effect of punishment and moral costs on cartel choices and agreements. This paper proposes an experimental analysis of the impact of sanctions schemes and moral costs on the propensity to engage in cartel agreements. This article’s contributions span three specific domains: law and economics via the economics of cartels, managerial and business economics via a study of compliance, and behavioral and experimental economics notably via an analysis of gender, risk aversion, and limited opportunism.

First, regarding the economics of cartels, our behavioral approach contributes to better evaluating cartel punishments, and to documenting the conditions under which efficient competition policy may be envisioned.[24] Some of the law and economics literature on cartels questions the extent to which antitrust law enforcement plays an appropriate role in reducing cartelization. For instance, Allain et al. (2015) show that in dynamic games, the amount of the optimal fine is much lower than the Becker-Lande rule suggests. Dargaud et al. (2016) focus on the effects of distortive fines imposed on cartels. Marvao and Spagnolo (2023) revisit the pros and cons of introducing cartel criminalization in the EU, showing that it may have led to a decrease in leniency applications and cartel convictions. Leniency, in particular, has been found to have potentially ambiguous effect as regards dissuasion. An increase in convicted cartels resulting from a leniency regime could as a matter of fact be due to an increase in cartel activity. In this perspective, our experimental results add to this literature, as it identifies key sanctions schemes which best deter cartel formation. In particular, our results argue for severe fines,[25] as well as regular detections of cartels. Severe fines and a high probability of detection also help to increase the deterrent effect of leniency programs, which is similar to the results reported by Chowdhury et al. (2018). Concerning detection, our results nuance the Beckerian substitutability between fines and detection, as the level of the probability of detection is found to matter in itself, which could be explained by risk aversion. Another important result of our experimental analysis is that exclusion is the most effective sanction scheme in deterring cartels. This result argues for the development of sanctions to be imposed on the individuals who engage in cartels, which is in line with the public policy discourse on the value of incapacitation sanctions, whose benefits have been highlighted (see Hammond 2010). In most countries, these sanctions are found to be better accepted by the general public than prison sentences (Stephan 2017). Last, in line with Bodnar et al. (2023), our experimental findings do not show that leniency is a strong tool to deter cartel formation as it seems to dilute deterrence and undermine the effect of punishment, whereas the theoretical literature on leniency suggests otherwise, as discussed in Subsection 2.2. Our findings contribute to the understanding of how participants may perceive the leniency situation, as they are not playing a prisoners’ dilemma. Collusion here is based on explicit adherence to an agreement, which could generate a greater sense of loyalty between participants (rather than in a prisoner’s dilemma), thereby reducing the incentive to denounce each other, and thus the effectiveness of leniency. Also, the participants may have seen leniency as an opportunity to avoid paying fines, rather than a risk to be reported.

Second, our work also contributes to business practice and compliance, as our results can contribute to drawing up guidelines on how to design a more effective compliance program. To begin with, results show that ex post, i.e. forced compliance (which could be enforced through a strong ex post monitoring on firms and managers who infringed antitrust law), could be more effective than a mere code of conduct. Stober et al. (2019) has already shown that specific compliance training is more effective than general training. He provides a better understanding of how a code’s design matters for both managers’ ethical intent as well as their willingness to report misconduct. More research could be done on ex post compliance and monitoring. Incentive-based approaches to compliance, as studied by Stucke (2014), could be part of this forced compliance. Last, our results on the small but significant effect of moral costs, argue for strengthening programs, which emphasize the harm inflicted by cartels on customers or business partners. These findings argue in favor of sophisticated compliance programs, which should include detailed information on the loss inflicted to consumers as, in line with Engel and Zhurakhovska (2014), we find that moral costs reduce cartel formation. More generally, public policy should strengthen and improve publicity and communication on cartel damages inflicted on victims, as it may be poorly known (particularly in intermediate goods markets where the victims are indirect). In this way, media coverage of cartels should also be strengthened.

Last, as regards behavioral and experimental economics, our article suggests limited opportunism. Our results imply that further research is needed to assess how information regarding the moral costs of cartel activities influences extrinsic motivations. Our findings offer limited evidence of a potential crowding effect between extrinsic motivations (sanctions) and intrinsic motivations (moral costs) (Frey 2000) and provide some insight into the importance of designing enforcement policies that effectively balance these motivations. In particular, the issue with cartels may be that the level of punitiveness (i.e. the attitude towards the punishment of cartels) may be relatively low, as individuals are not always aware of the harm caused as the negative externalities imposed onto the third party may be underestimated (see Boulu-Reshef and Monnier 2024). To strengthen deterrence, there should therefore be greater efforts to stigmatize these practices. Moral cost could also be potentially interacting with risk-aversion, as risk-averse individuals may choose the decision that minimizes moral cost, even if it’s not the most financially advantageous option. This complicates the analysis of cartels’ decision-making since risk aversion and moral costs could interact with each other. But the literature is contradictory regarding this effect. For instance, Mukerjhee (2022) studies a counter-intuitive relationship between consumer altruism and risk taking, and finds that trait altruism and risk taking are significantly and positively correlated. Further research could be undertaken on this question. In addition, as regards individual characteristics, our results show that gender and risk aversion play a role in cartel formation which is in line with Abate and Brunelle (2022). In this perspective, encouraging gender balance in senior management positions could help reduce anti-competitive practices.

6 Conclusions

In a nutshell, our results show that forced compliance and exclusion are more effective at deterring cartels than monetary and leniency sanction schemes. However, leniency leads to an increase in the rate of cartel detection. Moreover, higher fines are found to be associated with lower propensities to engage in cartel agreements, especially when such fines exceed cartel overprofit. High probabilities of detection are also associated with lower cartel choice and formation. Moral cost is found to reduce in a statistically significant but small fashion the propensity to engage in cartel agreements, notably when the sanction is simple, as in the monetary sanction scheme. Concerning individual characteristics, both risk aversion and being a woman are found to reduce the propensity to engage in cartel offenses. Our results have implications across several key areas. In antitrust research, they support the argument that escalating disqualification orders may be necessary. In business compliance, they highlight the importance of ex post monitoring and underscore the significant harm caused by cartels. Finally, in behavioral and experimental economics, our findings reveal limited opportunism, some degree of risk aversion, and a gender bias.

Future research using our experimental framework could investigate complementary issues, such as the importance of anonymity that may impact behavior (see Kirchler et al. 2016) as it changes the perception of responsibility. In addition, given that compliance and exclusion sanction schemes turn out to be more effective at deterring cartels, future research could study the impact of training on legal risks and the damages inflicted on third parties, i.e. consumers or businesses. For instance, it would be relevant to replicate our experiment with subjects who have previously received training on antitrust regulations.

Last, it could be useful to broaden our experiments to other anticompetitive practices, such as unilateral conduct, and to assess the deterrent effect of allowing the use of information revealed during non-cartel investigations to prosecute cartels, as proposed by Ghosal (2011).

Funding source: Institut de la Concurrence

Funding source: Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

-

Research funding: This work was supported by Institut de la Concurrence and Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Table A1.:

Comparison of cartel choices by fine (Panel a.) and by probability of detection (Panel b.) by moral cost (p-value – χ2)

| Baseline | Leniency | Compliance | Exclusion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Cartel formation | Choice | Cartel formation | Choice | Cartel formation | Choice | Cartel formation | ||

| a. Fine | |||||||||

| All data | 5 vs 10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 10 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| No cost (0) | 5 vs 10 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.269 | 0.061 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| 10 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Low cost (3) | 5 vs 10 | 0.082 | 0.108 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 0.043 | 0.007 | 0.012 |

| 10 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| High cost (7) | 5 vs 10 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.214 | 0.246 | 0.014 | 0.018 |

| 10 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.005 | |

| 5 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Full cost (10) | 5 vs 10 | 0.125 | 0.148 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 10 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 vs 15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| b. Probability of detection | |||||||||

| All data | 1/3 vs 2/3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1/10 vs 9/10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| No cost (0) | 1/3 vs 2/3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1/10 vs 9/10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Low cost (3) | 1/3 vs 2/3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1/10 vs 9/10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| High cost (7) | 1/3 vs 2/3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1/10 vs 9/10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Full cost (10) | 1/3 vs 2/3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1/10 vs 9/10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

Appendix B: Instructions

Translation of the instructions – The original instructions were in French.

Thank you for taking part in this experiment. Each participant receives exactly the same instructions. All decisions are anonymous.

It is important that you remain silent. If you have any questions, raise your hand and we will come and answer your questions personally. You will be paid in cash at the end of the experiment.

In the first stage of the experiment, you will make individual decisions. In the second stage, the amount of money you earn will depend on your decisions and the decisions of the other participants. The instructions below are for the second stage.

Roles

There are two roles: Type 1 players and Type 2 players. Type 1 players make decisions as business managers and Type 2 players have the role of the consumer.

Type 1 players make decisions in an environment in which they can agree to reduce competition by increasing their profits and reducing consumer surplus. This practice can be detected and sanctioned.

Type 2 players will complete a questionnaire. They will be informed of their earnings, which will be affected by the decisions of the Type 1 players.

Roles and groups of three people are fixed for the whole experiment.

Rewards

All players earn a fixed 6 Euros for their participation.

After that, decisions made by Type 1 players affect the variable earnings of all players in the group.

Type 2 players do not make any decisions other than answering the questionnaire and their variable earnings are affected by the decisions of Type 1 players.

The total earning will be the sum of your fixed earning, your decisions in Step 1 and your experimental units earned in the second stage. In this stage the conversion rate will be 150 experimental units for 1 euro.

Decisions

Type 1 players must choose between Decision A and Decision B. Decisions will be made in several environments, as explained below.

Decision A corresponds to a competitive strategy that results in a profit of 10 for each Type 1 player and a surplus of 10 for the Type 2 player.

Decision B corresponds to a strategy of agreement between the two Type 1 players.

If only one of the players chooses Decision B, the other player’s Decision A will be implemented for both players. This strategy results in a profit of 10 for the Type 1 players and a surplus of 10 for the Type 2 player.

Both Type 1 players must choose Decision B for the agreement to occur. If the agreement occurs, this strategy results in a profit of 20 for the Type 1 players and a surplus of 0/3/7/10 [Note: Depending on the treatment] for the Type 2 player. This strategy is associated with a loss of 10/7/3/0 [Note: Depending on the treatment] for the Type 2 player compared to the surplus of 10 resulting from a Decision A. [Note: In the full loss treatment only, this sentence is added] The Type 2 player has no surplus in this situation. [Note: In the no loss treatment only, this sentence is added] The Type 2 player therefore has an unchanged surplus in this situation compared to the surplus resulting from a Decision A.

You will make a total of 96 decisions.

Environments

The information on the periods and environments are in the banner at the top of the interface.

An environment is characterized by

(1) a probability of detection of a possible agreement, and

(2) a sanction framework in case of detection of an agreement.

Probability of detection

The probability of detection will vary and this probability will be indicated in the interface.

In the first set of decisions, it will be 1/3 (=33.33 %) or 2/3 (=66.66 %).

In the second set of decisions, it will be 1/10 (=10 %) or 9/10 (=90 %).

[Note: This order is varied to control for order effects.]

Sanction Frames

You will make your decisions in four sanction frames, these frames will be randomly assigned, except for the Basic frame which will always be proposed first. The three frames Compliance, Exclusion and Leniency, are based on the Basic frame and add to it.

The Basic sanction framework, in case of detection:

A monetary sanction (a fine of 5, 10 or 15 as indicated in the interface) is applied for this decision.

The Basic + Compliance framework, in case of detection:

A monetary sanction (a fine of 5, 10 or 15 as indicated in the interface) is applied for this decision.

In the following decision, the possibility of an agreement between the two Type 1 players is no longer available and they are then obliged to choose Decision A: their profit is then 10 and the surplus of the Type 2 player is 10.

The Basic + Exclusion frame, in case of detection:

A monetary sanction (a fine of 5, 10 or 15 as indicated in the interface) is applied for this decision.

In the following decision, the possibility of a decision is no longer available. The two Type 1 players are excluded from the experiment for one decision: their profit is then 0 and the surplus of the Type 2 player is 10.

In the Basic + Leniency setting, if an agreement is formed, one or two Type 1 players can decide to denounce it before a possible detection occurs.

If only one of the two Type 1 players denounces the agreement, his/her fine will be cancelled.

If both Type 1 players report the agreement, the faster player will have his/her fine waived.

If no player denounces the agreement and the agreement is detected, the monetary sanction (a fine of 5, 10 or 15 as indicated in the interface) is applied for this decision.

Decision Repetition and Uncertainty About the Decision Environment

For each environment, Type 1 players will make two successive decisions.

During the first decision, they will know the environment in which the possible Compliance or Exclusion sanction frame may be applied.

During the second decision, they will not know the environment in which the possible Compliance or Exclusion sanction frame may be applied.

Instruction Summary

The Type 1 players make either decision A or decision B. Decision B, if made by both Type 1 players, increases the profit of the Type 1 players and reduces the surplus of the Type 2 players.

| Type 1 players’ decisions | Type 1 players’ earnings | Type 2 players’ earnings |

|---|---|---|

| Both choose Decision A | 10 | 10 |

| One chooses Decision A and one chooses Decision B | 10 | 10 |

| Both choose Decision B | 20 | 0/3/7/10 [Note: Depending on the treatment] |

An agreement may only be detected during the period in which the agreement has been formed.

Type 2 players will fill in a questionnaire and they will be informed of their surplus.

Roles are fixed for the whole experiment and you will be in a group of three.

An environment is characterized by a probability of detection and a fine.

You will be making decisions in four sanction frames.

Each environment will be repeated.

The Basic frame: the sanction is only monetary.

The Basic + Compliance frame: In case of detection, the monetary sanction is applied and Decision B is no longer available in the following period.

The Basic + Exclusion frame: In case of detection, the monetary sanction is applied and the possibility of a decision is no longer available in the following period because the two Type 1 players are excluded from the experiment for one period.

The Basic + Leniency frame: If an agreement is formed and if only one of the two Type 1 players denounces the agreement, his/her fine will be canceled and if the two Type 1 players terminate the agreement, the fastest player will have his/her fine canceled.

Technical note: All participants (Type 1 players and Type 2 players) have to finish their decisions in a given decision environment so that the server may start the following environment. Thus, only one player may slow down the whole session.

References

Abate, C., and A. Brunelle. 2022. “Cartel Behaviour and Boys’ Club Dynamics French Cartel Practice through a Gender Lens.” Journal of European Competition Law & Practice 13: 473–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeclap/lpac032.Search in Google Scholar

Abbink, K., B. Irlenbusch, and E. Renner. 2002. “An Experimental Bribery Game.” Journal of Law, Economics 18: 428–54.10.1093/jleo/18.2.428Search in Google Scholar

Abbink, K., and A. Sadrieh. 2009. “The Pleasure of Being Nasty.” Economics Letters 105: 306–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2009.08.024.Search in Google Scholar

Allain, M. L., M. Boyer, R. Kotchoni, and J. P. Ponssard. 2015. “Are Cartel Fines Optimal? Theory and Evidence from the European Union.” International Review of Law and Economics 42: 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2014.12.004.Search in Google Scholar

Andres, M., L. Bruttel, and J. Friedrichsen. 2021. “The Leniency Rule Revisited: Experiments on Cartel Formation with Open Communication.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 76: 102728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2021.102728.Search in Google Scholar

Andres, M., L. Bruttel, and J. Friedrichsen. 2023. “How Communication Makes the Difference between a Cartel and Tacit Collusion: A Machine Learning Approach.” European Economic Review 152: 104331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104331.Search in Google Scholar

Apesteguia, J., M. Dufwenberg, and R. Selten. 2007. “Blowing the Whistle.” Economic Theory 31: 143–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-006-0092-8.Search in Google Scholar

Bailey, E. M. 2015. “Behavioral Economics and U.S. Antitrust Policy.” Review of Industrial Organization 4: 355–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-015-9469-9.Search in Google Scholar

Bartling, B., R. A. Weber, and L. Yao. 2015. “Do Markets Erode Social Responsibility.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130: 219–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju031.Search in Google Scholar

Becker, G. 1968. “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 76: 169–217. https://doi.org/10.1086/259394.Search in Google Scholar

Bennett, V. M., L. Pierce, J. A. Snyder, and M. W. Toffel. 2013. “Customer-Driven Misconduct: How Competition Corrupts Business Practices.” Management Science 59: 1725–42. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1680.Search in Google Scholar

Bernhardt, D., and M. Rastad. 2016. “Collusion under Risk Aversion and Fixed Costs.” The Journal of Industrial Economics 64: 808–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12111.Search in Google Scholar

Bigoni, M., S.-O. Fridolfsson, C. Le Coq, and G. Spagnolo. 2015. “Trust, Leniency, and Deterrence.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 31: 663–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewv006.Search in Google Scholar

Bigoni, M., S.-O. Fridolfsson, C. Le Coq, and G. Spagnolo. 2012. “Fines, Leniency and Rewards in Antitrust.” The RAND Journal of Economics 43: 368–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2171.2012.00170.x.Search in Google Scholar

Bodnar, O., M. Fremerey, H. T. Normann, and J. Schad. 2023. “The Effects of Private Damage Claims on Cartel Activity: Experimental Evidence.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 39: 27–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewab010.Search in Google Scholar

Boulu-Reshef, B., and C. Monnier. 2024. “Punitive Attitudes toward Cartels: Evidence from an Experimental Study.” European Journal of Law and Economics 58: 481–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-024-09824-w.Search in Google Scholar

Buccirossi, P., and G. Spagnolo. 2008. “Corporate Governance and Collusive Behavior.” In Issues in Competition Law and Policy, edited by D. W. Collins, 1219–40. Washington: American Bar Association.Search in Google Scholar

Carson, T. L. 2003. “Self-interest and Business Ethics: Some Lessons of the Recent Corporate Scandals.” Journal of Business Ethics 34: 389–94.10.1023/A:1023013128621Search in Google Scholar