Abstract

In a growing digital scenario where phraseology has become aware of technological realities, literary translation is timidly testing sophisticated AI-based tools. This study aims at assessing the quality of the output rendered by neural machine translation (NMT) systems, i.e., DeepL and Google Translate, and large language models (LLMs), i.e., ChatGPT and Gemini, in the English>Spanish translation of five comparative idioms extracted from literary texts. To this end, professional literary translators and translation undergraduates evaluate their output against human translation (HT), following the parameters proposed by Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez (2024) to measure creativity in the translation of multiword-expressions: adequacy (morphosyntactic, semantic, and pragmatic) and novelty. The findings show that HT stands out, although NMT systems outperformed morphosyntactically. LLMs, especially ChatGTP, show promising creative results. Therefore, this study serves to reflect on the use of technologies for the translation of creative phraseology in the context of literature.

1 Introduction

Recent decades have witnessed the outburst of artificial intelligence (AI) and the inexorable development of language technologies, resulting in sophisticated methods for processing large amounts of data that enhance effective communication. These AI-based tools have emerged thanks to the combination of several disciplines, such as Machine Learning, Natural Language Processing, Deep Learning, and Speech Recognition, among others (Ministerio para la Transformación Digital y de la Función Pública 2023). As a result of this convenient intertwining, machine translation (MT) systems, computer-assisted machine translation (CAT) tools, and, more recently, large language models (LLMs) have become sufficiently refined to become part of the workflow of many translators (Carl and Braun 2018; Li 2024).

In this globalised scenario, both the translation industry and language services have inevitably been reshaped to prioritise immediacy, necessity, savings, and production with the help of these tools (Toral and Way 2018; Declercq and Van Egdom 2023). Thus, the era of automation has only recently reached multiple areas that involve human essence and are now adopted globally by enterprises in their creative process (Wu et al. 2021). As the genius trapped inside books is very difficult to replicate without human intervention, literary translators have predominantly observed this digital evolution from afar (Toral and Way 2018). For this reason, until relatively recently literary translation was considered “the last bastion of human translation” (Toral and Way 2014: 174).

Meanwhile, studies on phraseology have undergone an unprecedented evolution because of the advancement of disciplines such as Computational Linguistics or Computational Phraseology. This research has paved the way to new approaches and methodologies that highly benefits linguists, lexicographers, language learners, translators, and interpreters alike (see Corpas Pastor et al. 2021; Mitkov 2022; Monti et al. 2024). However, within these language foundations, idiomatic, pragmatic or contextual aspects in phraseology (Sinclair 2007), among others, continue to be of interest to scholars (Mellado Blanco 2022; Corpas Pastor et al. 2024) and of concern to both professional translators (Cabezas-García 2021; Sidoti and Lapedota 2023) and trainees (Hidalgo-Ternero and Corpas Pastor 2020; Noriega-Santiáñez and Corpas Pastor 2023b).

Literary translators also draw on this research due to the multiple and very different phraseological challenges that can be found in literature (Noriega-Santiáñez and Corpas Pastor 2023a). Although the degree of technological adoption varies depending on the translation domain, some practitioners started to study how effectively MT and post-editing (PE) can handle multiple challenges derived from literary texts, including creative phraseology (Toral et al. 2018; Guerberof-Arenas and Toral 2020, 2022; Noriega-Santiáñez and Corpas Pastor 2023b, to name but a few). Based on this innovative approach, this study aims at assessing to what extent technologies can be applied to translate creative instances of phraseological units, and more specifically, comparative idioms.

The translation of multiword expressions (MWEs), notably idioms, poses huge challenges due to the intricate nature of these units, as translators not only have to identify them but also to interpret the aspects involved and search for their correspondence in the target language (Corpas Pastor 2003). According to Dobrovol’skij, (2013: 214), “there are practically always certain semantic, pragmatic, and collocational differences that must be discovered and described”. Thus, the complexity in translation varies depending on both the degree of phraseological competence of the translator and the degree of equivalence of the MWE (full, partial or no equivalence) (Corpas Pastor 2001; Molina Plaza 2004). In fact, the very nature of MWEs favours linguistic creativity due to their characteristic features, such as polylexicality, fixation, idiomaticity, etc. (Mena Martínez and Sánchez Manzaneres 2015).

Following the results obtained in our previous pilot study (Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez 2024), which measured the creativity of four neuronal machine translation (NMT) systems, the present study seeks to expand our findings by incorporating machine translation (MT) produced by large language models (LLMs). We focus on a specific type of creative phraseology, namely, five comparative idioms found in fiction novels, written in English, and published in the 21st century. We then compare the quality of the output rendered by two NMT systems (DeepL and Google Translate) and two LLMs (ChatGPT and Gemini) against human translation (HT). To this end, we evaluate the translation of five comparative idioms in the English>Spanish language pair semiautomatically extracted from two purely book-based corpora[1], i.e., American Google Books and British Google Books. To measure creativity, four literary translators and four translation students assess the raw technology output as well as the HT. Creativity is then calculated using the formula proposed by Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez (2024).

This paper revolves around three research questions:

What are the scores achieved by MT and HT across the parameters of creativity in the translation of comparative idioms?

To what extent can technological tools (i.e. NMT systems and LLMs) be compared to HT?

Which NMT systems and/or LLMs perform better in terms of creativity when translating comparative idioms according to professional literary translators and translation students?

Considering these aims, this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses AI-based technologies for literary translation in the current digital scenario, with special emphasis on cutting-edge studies on translating creative phraseology with NMT systems and LLMs. Section 3 pinpoints the methodology employed, detailing the selection and evaluation of the idioms. Section 4 presents the results obtained on MWE creativity, depending on the different parameters and study groups. Section 5 discusses these findings against benchmarks studies, and Section 6 summarises the conclusions reached and introduces future lines of research.

2 Translation creativity in the era of artificial intelligence

Innovation must necessarily go hand in hand with creativity, as it is key to boosting global competitiveness and economic growth (Rojo and Meseguer 2018), including in the language industry. Reality contradicts the assumptions that the translator’s task is much less creative than the writer. In fact, the translator is typically confronted with multiple constraints imposed both by culture and by the linguistic, semantic, and pragmatic aspects embedded in both the source and target language (Boase-Beier and Holan 2016). According to the PETRA-E Framework of Reference for the Education and Training of Literary Translators (PETRA-E Framework 2016), one of the core skills is “literary creativity”, which entails the ability to deal with challenges and seek translations alternatives creatively.

However, defining creativity remains a formidable challenge. Many scholars have tried to reach a conclusion over the last decades, stating that at the individual and socio-cultural level, creativity has a component of something new, original, or innovative, as well as an element of appropriateness, usefulness, or adequacy (Sawyer and Kenriksen 2023). This definition has been highly supported in the field of translation by Guerberof-Arenas and Toral (2020), who claim that creativity can be divided into acceptability (fitting translations) and novelty (innovative solutions).

Precisely due to its creative nature, literary translation has remained untouched by this technological tsunami until recent years (Ruffo 2022; Declercq and Van Egdom 2023; Way et al. 2023). In fact, literary translators do not generally use any tool that might constrain their creative process (Ruffo 2018) or dampen their voice (Taivalkoski-Shilov 2018; Kenny and Winters 2020) when translating, as is the case of automatic translation. This attitude derives from “the idea [that] linguistic stratification was the basis for translation models, mostly established on the belief that the syntax of natural languages could be formalized” (Ferreira and Schwiter 2017: 4).

At the beginning, MT tools were more rudimentary, operating by simply decoding a language and then redecoding an equivalent message into another (Hadley et al 2023). However, recent AI-based tools that incorporate deep learning defy the former literary research, challenging the pioneering findings in the 2010s with rule-based or statistical MT models that barely handled literacy intricacies (Voigt 2012; Toral and Way 2014, 2015). Thus, the arrival of the so-called NMT systems was a precedent for the development of studies that explored aspects such as productivity, efficiency, and quality in the translation of literature (Toral and Way 2018; Webster et al. 2020). In these studies, machine-translated, post-edited output began to be compared to raw MT and HT output (Moorkens et al. 2018; Matusov 2019; Way et al. 2023). While the results were tentatively promising, there was always a need for human intervention to reach an acceptable level of quality in literary translation.

This interrelation between machine and humans has been discussed at length. Some scholars even considered a novel technological framework that encourages the production of tools that enhance human skills and empower users, called “Human-centered AI (HCAI)” (Shneiderman 2020; Briva-Iglesias 2024). HCAI revolves around the “augmented” notion applied to human abilities through technology, i.e., overcoming the human cognitive barrier through the support of these tools (O’Brien 2024). In fact, AI is currently being employed in a multitude of creative fields (Elfar and Dawood 2023). Speaking of its potential, some scholars even propose a so-called ‘Human-AI Co-Creation Model’ to explain the creative process and the possibilities of AI in the sector (Wu et al. 2021).

Against this background, LLMs, such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot, etc., potentially support this trend, as they can “leverage the collective intelligence of multiple agents, enabling superior problem-solving capabilities compared to individual model approaches” (Wu et al. 2024: 2). In terms of education and translation, LLMs have multiple applications in the teaching sphere, specifically in the assessment and design of didactic materials and the stimulation of students’ key competences (Schön et al. 2023; Pérez and Robador Papich 2023; Alcaide-Martínez 2023; Grassini 2023). These applications can be applied to future generations of translators. Among their features, LLMs mimic human language by translating texts with a certain fluency, correctness, and speed (Qi 2024), enhancing in some way accessibility to literature (DeClercq and Van Egdom 2023). For this reason, these tools have recently been employed to translate literary texts and to tackle complex literary challenges (Li 2024; Du et al. 2025), as we explore in the section below.

Given the efficiency and sophistication of these contemporary AI systems, there is a growing discourse around creating a path toward collaboration between machines and humans, rather than seeing them as adversarial. However, there is a plethora of ethical aspects that need to be considered before adopting these tools. These aspects relate to (i) the literary translator, i.e., translators’ working conditions (low rates, tight deadlines, loss of human translators, among others), copyright issues, overreliance on technology, etc.; (ii) the product, i.e., the loss of quality, language automation, cultural or social bias, etc.; (iii) the planet, i.e., the impact on the environment due to the large number of resources consumed by these technologies (Bowker 2020; Kenny and Winters 2020; Moorkens 2022; Declercq and Van Egdom 2023).

2.1 A technological view of translating phraseology in literature

In this environment of creativity, the human component is undoubtedly also shaped by the phraseological layers found in languages. Accordingly, this section delves into the work that supports this study, with special emphasis on the translation of phraseology by means of technologies, notably NMT systems and LLMs.

Several scholars are interested in the intersection of creativity in translation and language technologies. Regarding creativity, Guerberof-Arenas and Toral (2020, 2022) were pioneers in exploring the extent to which language technologies can handle creative shifts, focusing on reading experience and NMT post-editing. Their studies compared the MT output of literary texts from English into Catalan and Dutch against HT and translations post-edited by professionals. By applying the proposed creative formula, they concluded that MTs fall short of achieving human creativity and that post-editing also limits the translator’s creative potential.

Noriega-Santiáñez and Corpas Pastor (2023a) studied the extent to which corpora and NMT systems can accomplish phraseological challenges: specifically, culturemes, neologisms, canonical, or manipulated idioms. Their findings showed that NMT systems at the time did not satisfactorily translate the more creative MWEs (notably neologisms or manipulated idioms); however, they reached a satisfactorily output when translating canonical idioms. Subsequently, they carried out a second study that focused solely on formal neologisms (Noriega-Santiáñez and Corpas Pastor 2023b) and the output rendered by NMT systems against HT (produced by translation students). They concluded that HT cannot be compared in terms of creativity with the NMT output, but they noted that some students found inspiration using these technologies. Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez subsequently (2024) conducted research on manipulated idioms, proposing for the first time a formula to measure the creativity of translated MWEs. During their research, they observed the performance of four NMT systems (DeepL, Google Translate, Bing Translator, and Reverso), from which they concluded that Google Translate and DeepL highly outperformed the others. However, none of them came close to replicating the degree of creativity required to address phraseological challenges.

Another recent study by Li (2024) has explored the potential and limitations of AI in the translation into English of a Chinese poem, exploring semantic judgement, narrative techniques, and emotional expression. Even though AI reached remarkable output in these fields, the author highlighted a profound gap between AI and human creativity. In this regard, Du et al. (2025) investigated the ChatGPT output of a literary text generated under six different configurations in four languages to measure their creativity in comparison to NMT and HT. They concluded that specific adjustments in the ChatGPT configuration can produce better results, although its output could not match that of HT. Furthermore, Zhang et al. (2025) conducted an exhaustive study on the quality of translations produced by LLMs and human translators using the parallel corpus LITEVALCORPUS. Both professional translators and students were involved in the evaluation, and multiple automatic evaluation metrics were also used. Their conclusions were that most current LLMs tend to produce worse translations than human translators produce in the high resource languages studied.

3 Methodology

This section pinpoints the procedures followed throughout this study, detailing the selection of the examples under evaluation, as well as the assessment of creativity and the evaluators’ profiles. We will follow the methodology developed by Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez (2024), including their quantitative approach (i.e., their formula to measure creativity on translated MWEs).

3.1 Comparative idioms selection

Five comparative idioms are used as instances in this study given their creative nature. Idioms are a type of MWE[2] characterised by their polysemy and fixed or semi-fixed structure (having phonic, morphological, syntactic, and lexico-semantic constraints), which conveys an idiomatic meaning (García-Page 1991; Corpas Pastor 1996, 2003). Among their defining qualities, idioms are culturally specific, making it challenging to find their lexicographical and textual equivalents when translating (Leal Riol 2008; Mellado Blanco 2015).

In the case of comparative idioms, these MWEs draw a comparison between two real-world entities or referents, which may involve different degrees (superiority, equality, or inferiority) and communicative purposes (from intensifying or hyperbolising to simply communicating or informing) (García-Page 2008; Mellado Blanco 2012). According to Mellado Blanco (2023: 314), these units mainly have “a pragmatic meaning in order to intensify a quality, action or state expressed by an adjective or verb”. Thus, comparative idioms are based on stereotypical, cultural, or pragmatic values under the presence of semantic features (Pamies Bertrán 2005; García-Page 2008).

Fixed comparative idioms comprise a referential element (an adjective, verb or noun), a comparative particle (e.g., as, like/tan, como), and a comparative (the second term in the comparison) (Mellado Blanco 2012). While in English, comparative idioms follow structures such as “(be) as + adjective/adverb + as + clause/noun” or “(be) like + (a/an/the) noun” (e.g., “as fast as lightning” or “like a bull in a china shop”), in Spanish these MWEs are typically constructed as “(be) + tan + adjective/adverb + como + noun”, “como + noun”, “más/menos + noun/adjetive + que + noun/clause” or “verb + como + noun” (e.g., “tan loco como una cabra”, “como pez en el agua”, “más viejo que Matusalén”, or “dormir como un lirón”) (see Pamies Bertrán 2005; Corpas Pastor 2021; Mellado Blanco 2023).

To make a real and updated compilation of phraseological needs in literature, the selection of comparative idioms follows a rigorous procedure. First, we consulted two purely book-based corpora: American Google Books and British Google Books. These large corpora were created by Mark Davies, and they are based on the digital books found in Google Books. As our primary intention was to retrieve comparative idioms found in novels, we searched both literary corpora using the following pattern: as [j*] as a|an|the [n*]. This search pattern returned idioms that met the “as + adjective + as + (the/a/an) noun” structure. From the results obtained, we filtered the most frequent idioms found in novels published in the 2000s.

After generating a list of the 20 most frequent comparative idioms, we carried out a double filtering. First, we verified in reference dictionaries, such as Cambridge Dictionary[3] and/or Merriam Webster Dictionary[4], that these items were effectively idioms. We then proceeded to systematically enter each idiom into the Google Books digital repository. By means of a narrow search in Google Advanced Book Search[5], we filtered those books that included these idioms and were (i) written in English and (ii) published between 2010 and 2025.

Table 1 below encompasses the five chosen idioms that met our criteria together with the novels in which they are found

Comparative idioms in English

| COMPARATIVE IDIOM 1: as cool as a cucumber | |

| Context | “I helped set you on the road, but you were a perfect client,” he says, “Lots of people are on the phone to me every few minutes wanting to know what’s going on. Asking for information I don’t have. You were as cool as a cucumber. I knew you’d be OK.” |

| Book details | Three weddings and a proposal by Sheila O’Flanagan (2021) |

| Meaning | https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/as-cool-as-a-cucumber |

| COMPARATIVE IDIOM 2: as old as the hills | |

| Context | “He looks as old as the hills,” Ham said breathlessly. “But he’s sure a bodcat when you get hold of him.” |

| Book details | The Men Vanished: A Doc Savage Adventure by Lester Bernard Dent (2022) |

| Meaning | https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/as-old-as-the-hills |

| COMPARATIVE IDIOM 3: as white as a sheet | |

| Context | I got Bob to drive the truck back to the yard, and when we got there, he was as white as a sheet. |

| Book details | You Call, We Haul: The Life and Times of Bob Carter by Mat Ireland (2019) |

| Meaning | https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/as-white-as-a-sheet |

| COMPARATIVE IDIOM 4: as flat as a pancake | |

| Context | You won’t believe this, but just as I turned into the driveway I heard a loud bang, and I limped down the driveway with the left tire on my trailer as flat as a pancake. |

| Book details | Crazy As a Run Over Dog. .. But Don’t Blame It All on the Animals by Mike Rowland (2014) |

| Meaning | https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/as-flat-as-a-pancake |

| COMPARATIVE IDIOM 5: as dead as a doornail | |

| Context | Some say she was pushed, but most thought she had jumped. Whichever was the sad reality, the wiry-framed girl with the soft voice and the ever-teary eyes was gone. She was, in the words of Karen Walpole from B Wing, ‘As dead as a doornail.’ |

| Book details | House of Sticks by Marc Scott (2023) |

| Meaning | https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/as-dead-as-a-doornail |

The context corresponds to (i) the paragraph within the main texts or (ii) the complete speech of the character where the comparative idiom was found. Furthermore, a link to the meaning of the idiom was included to help evaluators.

3.2 Evaluation

The evaluation was carried out in two phases, following the methodology of the pilot study from our previous investigation on manipulated MWEs (Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez 2024). Our formula extends Guerberof-Arenas and Toral’s (2022) proposal to calculate the creativity score (see below).

3.2.1 First Phase

This first phase consists of the evaluation of the five comparative idioms by eight participants (four professional literary translators and four translation students). In the first phase, both groups received a Word sheet containing the informed consent and the voluntary participation agreements, the purpose of the study, the dissemination information, and the evaluation rubrics. These sections are divided into (i) the demographic data and preliminary questions related to the use of MT systems and LLMs, and (ii) the evaluation of the comparative idioms with the instructions on how to proceed.

Table 2 below comprises the profile of both professional literary translators (PLT) and translation students (TS) based on their demographics:

Professional literary translators and translation students’ profiles

| PLT | TS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Questions | Data | Questions | Data |

| Years old | 27–57 | Years old | 22–23 |

| Years of experience as a literary translator | 3–26 | Academic year | 4th |

| Number of translated novels | 3–150 | Language pair(s) in which you translate | English/French/Arabic>Spanish |

| Language pair(s) in which you translate novels | English/French>Spanish | Experience as translator (yes/no) | No (n = 3) / Yes (n = 1) |

| Literary genres you have translated | Essay, science fiction, psychology, romance, horror, graphic novel, short story | Experience as literary translator (yes/no) | No (n = 3) / Yes (n = 1) |

While the professional profile covers a more varied age range, the students are a year apart and in the last academic year of the Degree in Translation and Interpreting. All the professional translators have at least 3 years of work experience as literary translators, having translated up to 3 novels, whereas all but one of the students have no professional experience. The language combinations are similar between groups, but all evaluators have translated a literary text at least in the English>Spanish language combination.

Regarding the evaluation of the idioms, the evaluators carefully read and applied the following instructions found in the second section of their evaluation sheets (Table 3). These are the parameters that are proposed to measure creativity in MWEs, based on the parameters of equivalence presented by Corpas Pastor (2003) and the creative formula proposed by Guerberof-Arenas and Toral (2022), as explained below.

Parameters to evaluate the translation of MWEs

| Creativity in MWEs | Parameters | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Adequacy | Morphosyntactic | It refers to complementation, sentence function, and transformations. Provide a mark on a 5-point scale based on it. |

| Semantic | It refers to phraseological meaning, base image, lexical composition. Provide a mark on a 5-point scale based on it. | |

| Pragmatic | It refers to cultural competence, diasystematic constraints, frequency of use, discursive aspects, and implicatures. Provide a mark on a 5-point scale based on it. | |

| Novelty | Provide a mark on a 5-point scale based on the degree of originality and innovation of the comparative idiom. | |

The participants were told to evaluate these parameters on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 the lowest score (0%) and 5 the highest (100%). This evaluation (in grey) is presented in each of the five different evaluation rubrics (one per idiom), as provided in the example below (Table 3).

Evaluation rubric

| COMPARATIVE IDIOM | |||||||

| Context | |||||||

| Book details | |||||||

| Meaning | |||||||

| Translation | Target language (Spanish) | Evaluation | |||||

| Parameters | Likert | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1 | Morphosyntactic | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | |

| Semantic | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| Pragmatic | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| Novelty | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ||

Both professionals and students were asked to evaluate each comparative idiom by filling in this rubric. It displays the canonical form of the comparative idiom, the literary extract in which it was found, the book details (i.e., the name and author of the book), and the meaning of the idiom based on the dictionary definition. After providing the primary information, the translation into Spanish with different translation methods and systems is displayed. To ensure impartially when evaluating, the translations were anonymised and numbered, and no additional information was provided.

The translations into Spanish were rendered by (i) two NMT systems (Google Translate and DeepL), (ii) two LLMs, (ChatGPT and Gemini), and (iii) an HT made by a Spanish-native professional translator with a degree in Translation and Interpreting and a master’s degree in Literary Translation. Since DeepL and Google Translate stood out among the most advanced NMT systems in our previous study (Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez 2024), both systems were chosen for our new pilot study. Among the available LLMs, we selected two of the leading software to date: ChatGPT and Gemini.

In both NMT systems, the context was introduced; in other words, the comparative idioms were not presented in isolation. In the case of LLMs, the following prompt was also specified: “You were a literary translator skilled in the English>Spanish combination”.

3.2.2 Second Phase

In the second phase, all the evaluation sheets were collected and their data transferred to Excel spreadsheets to calculate creativity in each translation method.

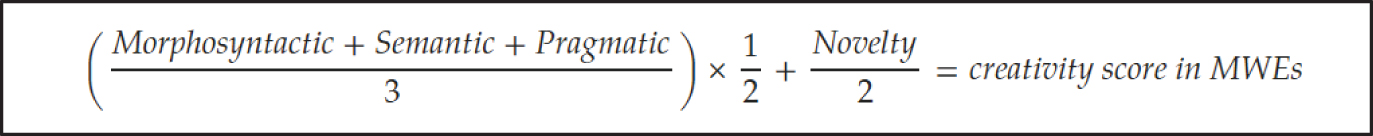

The creativity score was calculated considering the formula previously proposed by Guerberof-Arenas and Toral (2022), who distinguished between two main concepts: acceptability and novelty when evaluating the creativity in translations. According to their formula, acceptability is measured by the number of errors made in translation and creativity by the original and innovative solutions rendered. Regarding the proposal, Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez (2024) suggested a new formula, considering the complexity of translating MWEs. They divided the concept of acceptability into three aspects, according to the parameters of equivalence in MWEs proposed by Corpas Pastor (2003)—morphosyntactic, semantic, and pragmatic—which help to define whether an adequate translation of the concept has been achieved. In fact, the intrinsic innovative or creative factor of the MWE must function effectively within its context. For this reason, the following formula seeks to explore to what extent the translated solutions are creative:

Fig. 1: Creativity score in MWEs by Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez (2024).

In this paper, we first calculate acceptability and novelty parameters separately within each of the five examples. For this purpose, we measure the data retrieved from both groups. Consequently, after measuring creativity in comparative idioms using the proposed formula, the output rendered by NMTs and LLMs is compared to HT, which is used as the gold standard. Finally, we explore the technologies that professionals and trainees find more creative when it comes to translating comparative idioms, reflecting on their previous responses regarding the adoption of NMTs and LLMs.

4 Results

This section explores the results obtained based on the translation of five comparative idioms (CI) rendered by the different translation methods (Table 5).

idioms translations

| CI | Google Translate | DeepL | Human Translation | ChatGPT | Gemini |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| as cool as a cucumber | más tranquilo que una lechuga | Fuiste muy sereno | tan pancho | más tranquilo que un ocho | tan tranquilo como un pepino |

| as old as the hills | tan viejo como las colinas | viejo como el cielo | más años que el Sol | más viejo que Matusalén | más viejo que Matusalén |

| as white as a sheet | blanco como el papel | blanco como una sábana | pálido como un fantasma. | pálido como un muerto | blanco como un papel |

| as flat as a pancake | tan pinchada como una tortita | tan desinflada como un panqueque | más pinchada que una brocheta | más plana que una tabla | completamente pinchada |

| as dead as a doornail | muerta como un clavo | tan muerta como un clavo | estaba muerta y enterrada | más muerta que una piedra | muerta como un clavo |

Below, we explore the parameters of creativity in MWEs depending on the different evaluation groups: professional literary translators and translation students.

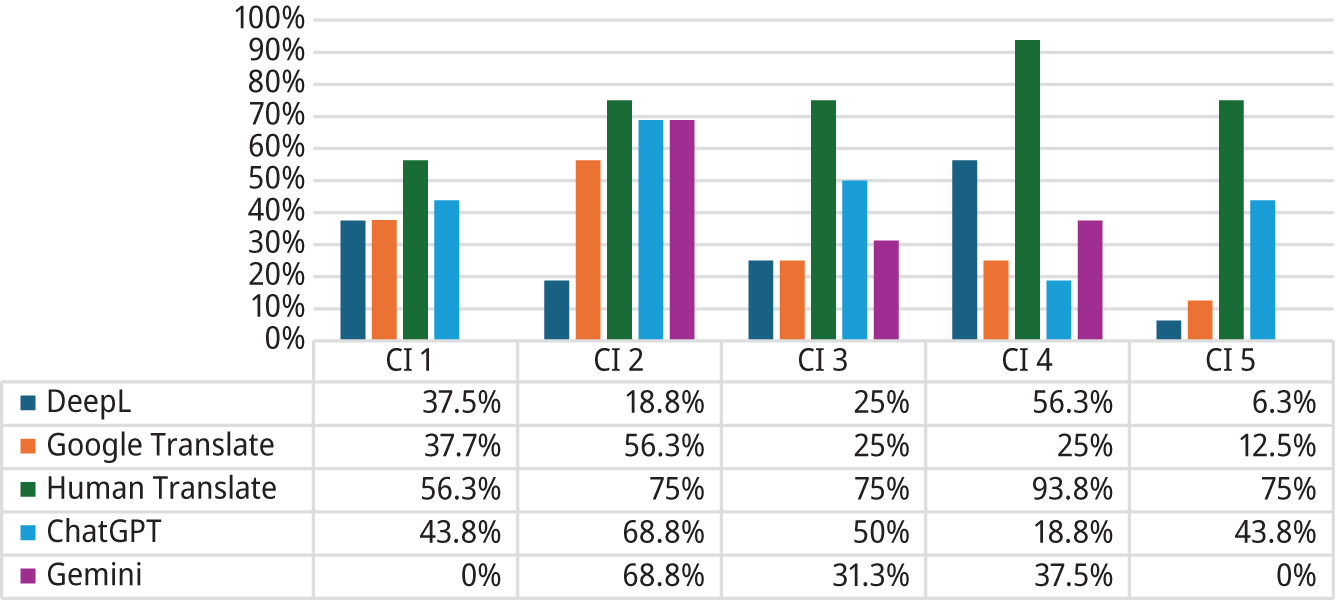

4.1 Adequacy and novelty in comparative idioms

Both adequacy (morphosyntactic, semantic, and pragmatic) and novelty parameters are calculated according to the Likert scale scores marked by the study groups. The tables below (Tables 6, 7, 8, and 9) summarise their answers by idiom, considering both MT and HT.

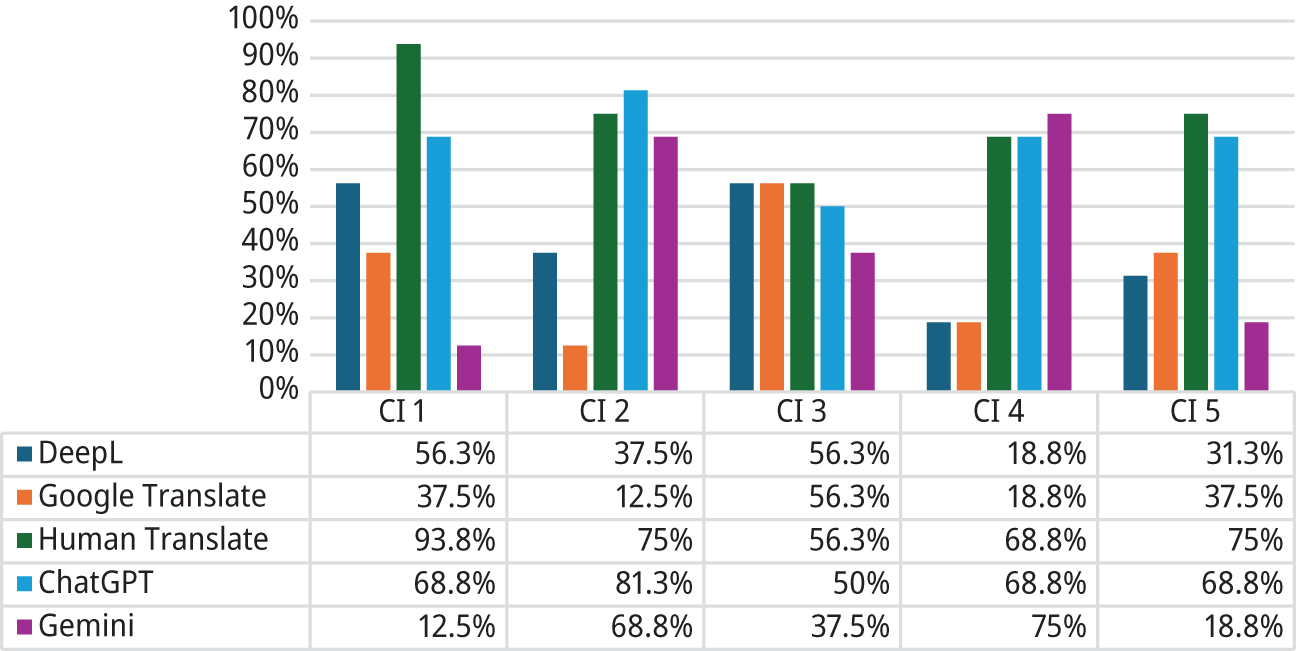

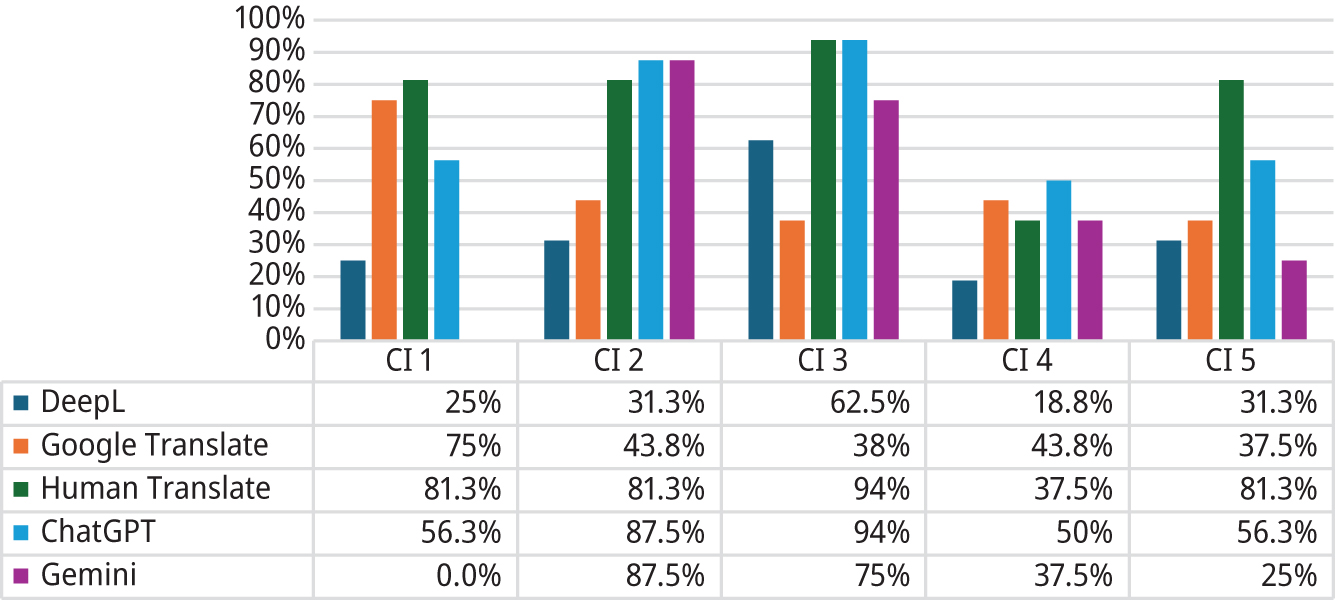

Results of the morphosyntactic parameter in comparative idioms

| Morphosyntactic parameter |

Professionals |

Students |

The morphosyntactic parameter received the highest scores, especially among students, since many of these technologies follow the structure of the source language. In fact, MT scores better than HT in some idioms, as HT no longer follows the morphology of the target language. An example of this case is CI 2, “as old as the hills”, translated by DeepL as “tan viejo como las colinas”, and by HT as “más años que el Sol”.

In addition, there are notable differences between the evaluations of students and professionals, especially in CI 3 and 4. Students evaluate the performance of NMT systems very well as opposed to professionals. Conversely, LLMs such as Gemini do not yield fully satisfactory results among professionals, except in the case of two comparative idioms (examples 2 and 4), while ChatGPT scores better in both groups, equalling, in fact, and even surpassing the HT score in many phraseological instances.

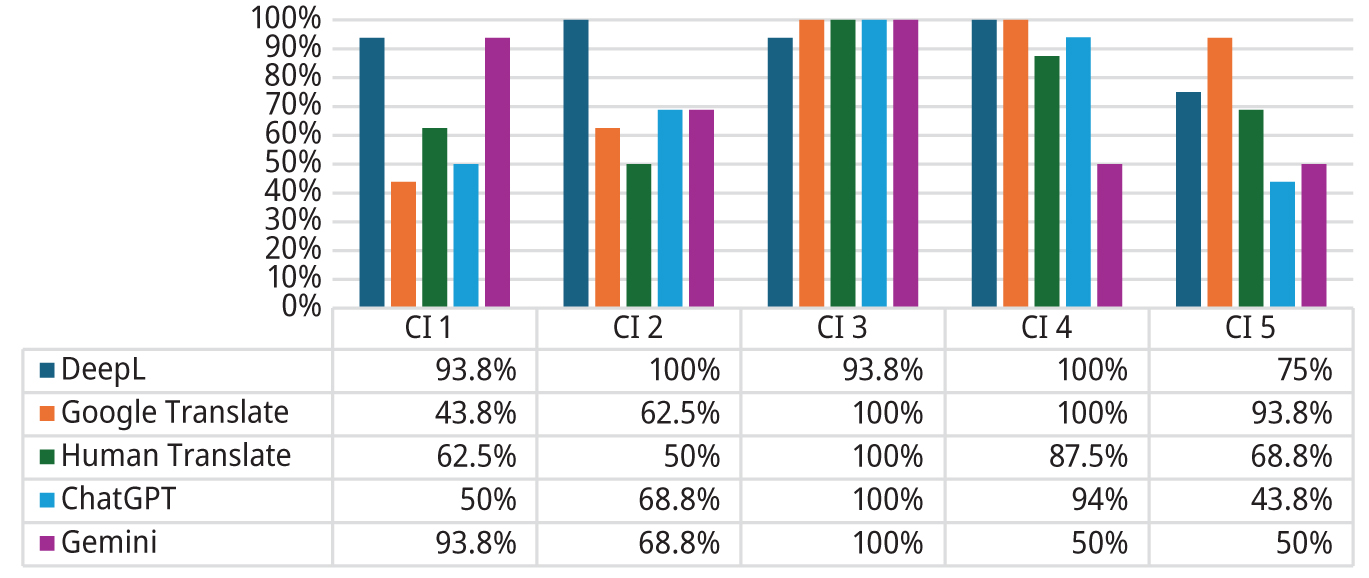

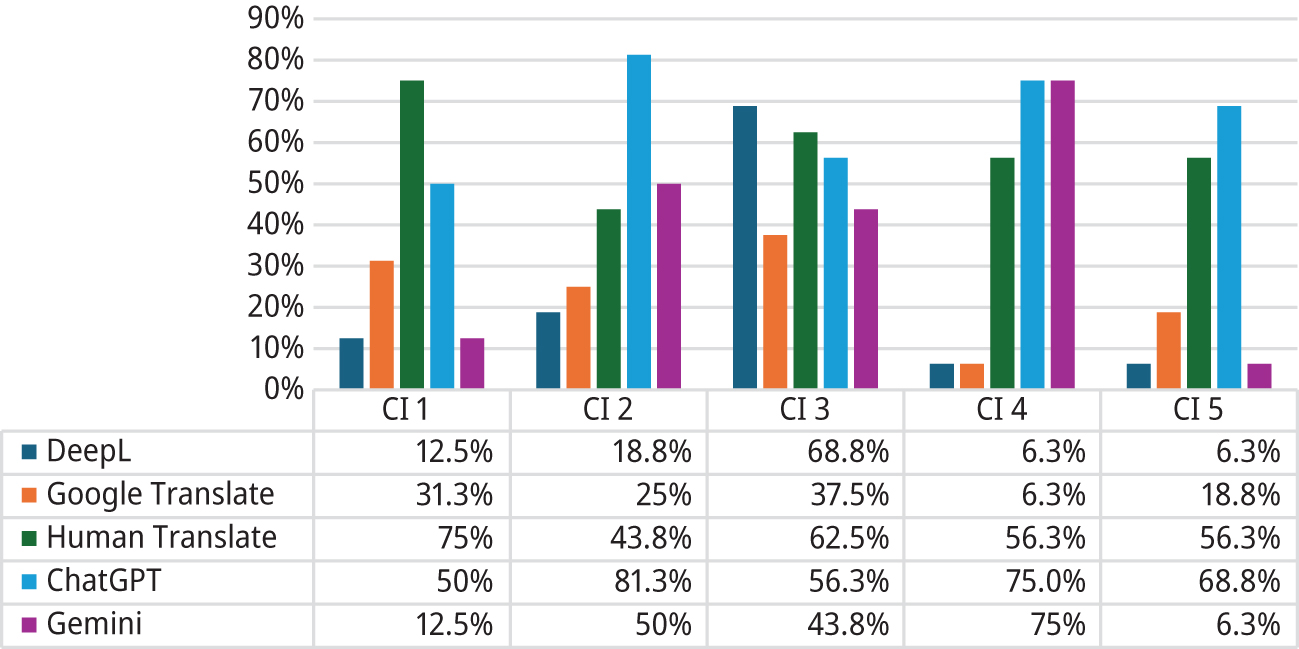

Results of the semantic parameter in comparative idioms

| Semantic parameter |

Professionals |

Students |

Regarding the semantic parameter, HT renders consistent results in all the comparative idioms, both in the evaluation of professionals and students, except in the case of CI 4 (“as flat as a pancake”). Students gave a significantly low evaluation of the translation “más pinchado que una brocheta”. Thus, there may also be a generational gap in the way the idiom is interpreted in some of the translations.

In this parameter, the performance of NMT systems, especially DeepL, drops significantly. Regarding LLMs, ChatGPT is once again the best-rated tool compared to Gemini. In fact, Gemini produced poor results in both CI 1 (6.3% or 0%) and CI 5 (12.5% or 25%) for both groups. In contrast, ChatGPT is as highly rated as HT in some idioms, as in the case of CI 4 (for professionals) or CI 3 (for students).

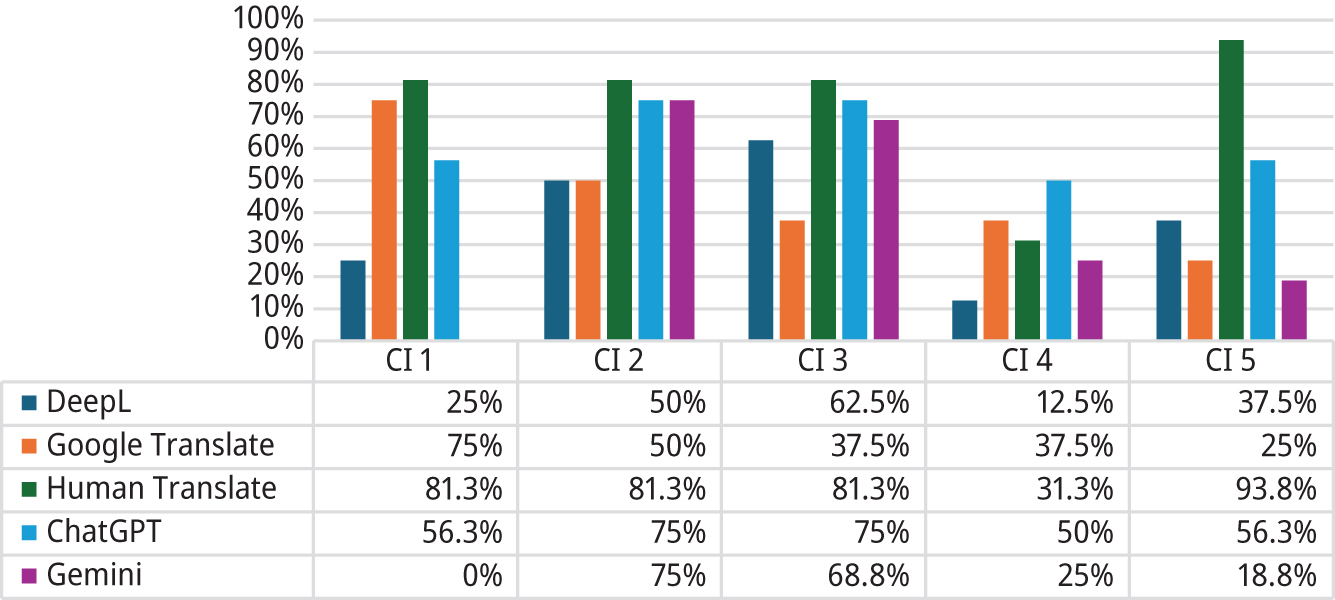

Results of the pragmatic parameter in comparative idioms

| Pragmatic parameter |

Professionals |

Students |

In terms of the pragmatic parameter, professional translators rated all translations lower than the other parameters. Nevertheless, HT continues to stand out in both groups, with particularly notable results in CI 5 among students (“as dead as a doornail” > “está muerta y enterrada”).

Regarding technological tools, NMT systems find a better audience among students, as professionals do not rate them high enough on the pragmatic parameter. Furthermore, LLMs diminish in quality for students, notably ChatGPT. However, Gemini again has an underwhelming average score, with some translations evaluated satisfactorily, such as CI 2 (50 or 75%), and others, such as CI 1 (12.5% or 0%), scoring very poorly.

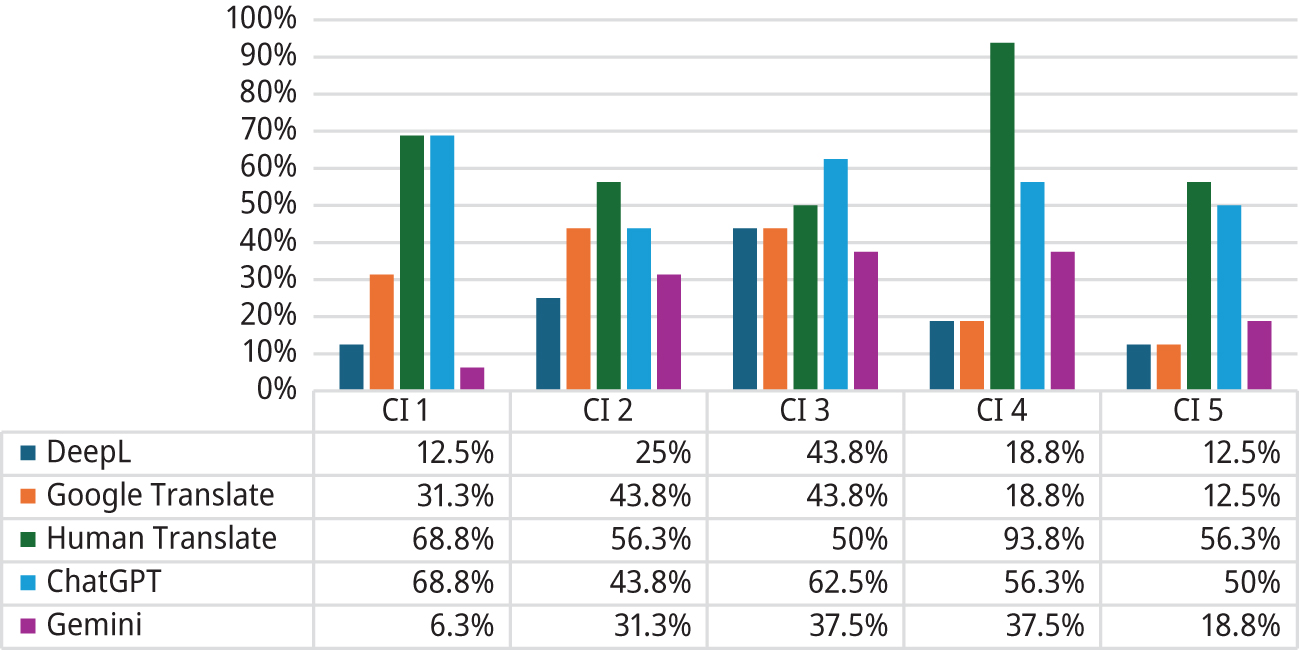

Results of the novelty parameter in comparative idioms

| Novelty parameter |

Professionals |

Students |

Finally, the data in the table above represents the parameter, novelty, that constitutes half of the creativity score. In this parameter, the human essence is truly evident, as both evaluation groups gave the maximum score to HT. CI 4 had the highest score among both professionals and students (93.8%), significantly above the other CIs.

In this parameter, neither DeepL nor Google Translate matched the performance of HT or that of AI-based tools such as ChatGPT, which consistently surpassed the other technological translation methods. In some examples, ChatGPT even achieved a similar performance compared to HT, and in one instance (CI 3 for professionals) even surpassed it. In contrast, Gemini rendered very poor results, even worse than NMT systems, as can be seen in CI 1 (6.3% or 0%) or CI 5 (18.8% or 0%).

4.1.1 NMT systems and LLMs compared to HT

Finally, the table below combines the average of the results obtained in each analysed idiom according to each parameter. The results are presented based on the data collected from professional literary translators (PLT) and translation students (TS).

Average of the parameters between professionals and students

| TRANSLATION | ADEQUACY |

NOVELTY | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | S | P | ||||||

| Machine translation | PLT | TS | PLT | TS | PLT | TS | PLT | TS |

| DeepL | 40% | 92.5% | 30.0% | 33.8% | 21.3% | 37.5% | 22.5% | 28.8% |

| Google Translate | 32.5% | 80.0% | 26.3% | 47.5% | 21.3% | 45.0% | 30.0% | 31.3% |

| ChatGPT | 67.5% | 71.3% | 61.3% | 68.8% | 62.5% | 62.5% | 56.3% | 45% |

| Gemini | 42.5% | 72.5% | 41.3% | 45% | 37.5% | 37.5% | 26.3% | 27.5% |

| Human translation | PLT | TS | PLT | TS | PLT | TS | PLT | TS |

| Professional Literary Translator | 73.8% | 73.8% | 73.8% | 75% | 55% | 73.8% | 65% | 75% |

The table shows that the evaluations are, in many cases, uneven, especially regarding the morphosyntactic parameter. These results might occur because of how the translations of the comparative idioms are interpreted given the experience and background of each evaluation group.

However, the trend in both groups is that HT outperforms the other translation systems, consistently maintaining high and balanced scores. In fact, except for the pragmatic parameter among professionals, HT outperforms all the others. Furthermore, DeepL stands out among students in the morphosyntactic parameter in some instances, as does Google Translate, but both are rated lower in novelty.

It is worth noting that LLMs such as ChatGPT are emerging in this table as tools that almost attain the level of human quality in adequacy, notably in morphosyntactic and semantic parameters. Concerning the novelty parameter, HT is rated first by both groups, and in the case of students it far surpasses all other technologies.

4.2 Professionals vs students: NMT systems or LLMs for creativity

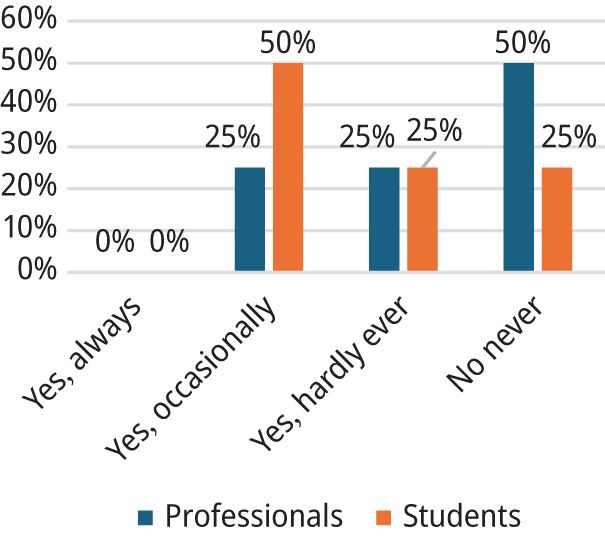

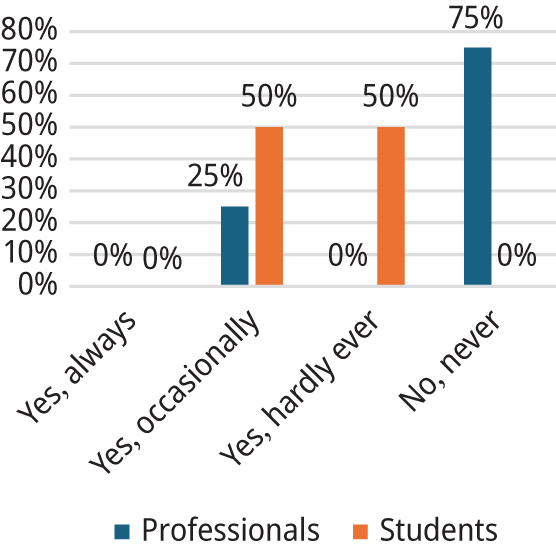

Regarding the answers of both groups at the beginning of the evaluation sheet, Table 11 comprises their technological adoption.

Technological adoption of professional literary translators and students

| Do you employ machine translation systems? | Do you employ large language models? |

|---|---|

|

|

A significant difference in technology adoption can be seen in Table 11. Although no group claims to always employ NMT systems or LLMs in literary translations, the degree of technology adoption in students is higher, notably in the use of LLMs. In comparison, professionals rarely use these technologies, although there is a slightly greater acceptance of NMT systems. However, their stance against these AI-based technologies is more noticeable.

Professionals who have integrated these technologies into their workflow claim they have found them useful for terminology research. In contrast, students who rely more on these tools state that they mainly use NMT systems to clarify or structure the text into the target language. Furthermore, students employ LLMs to review both the source and target text, conduct quick searches, or find synonyms, among other tasks.

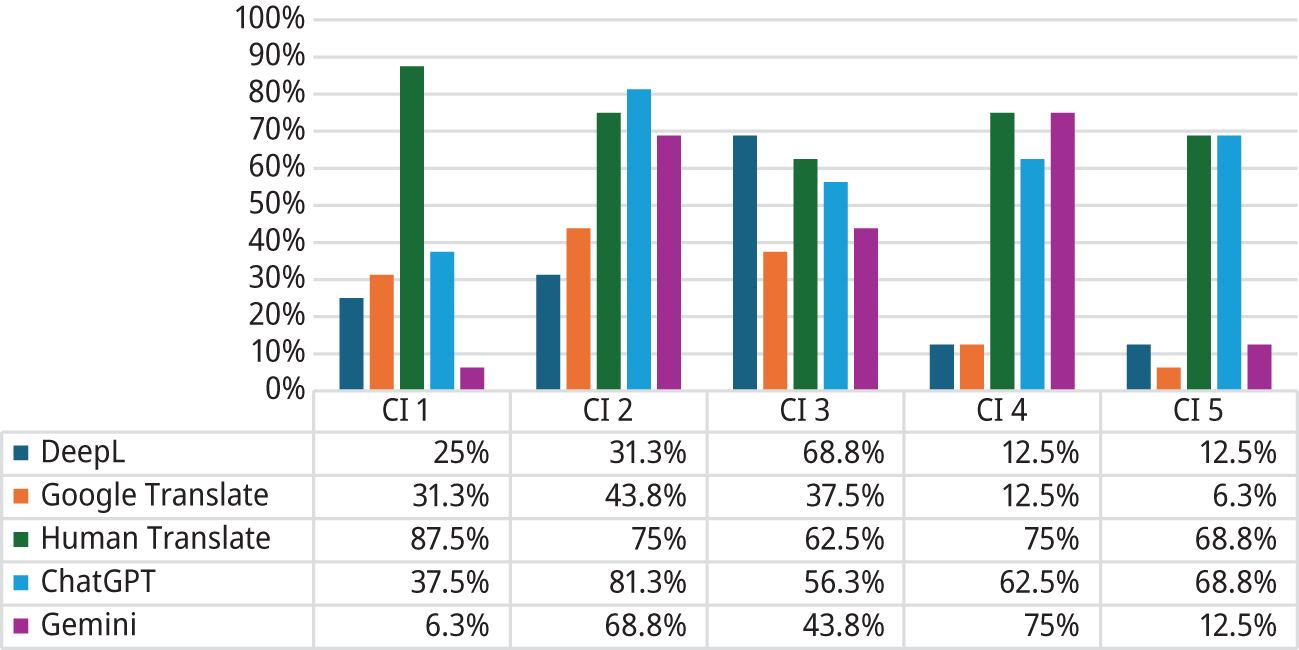

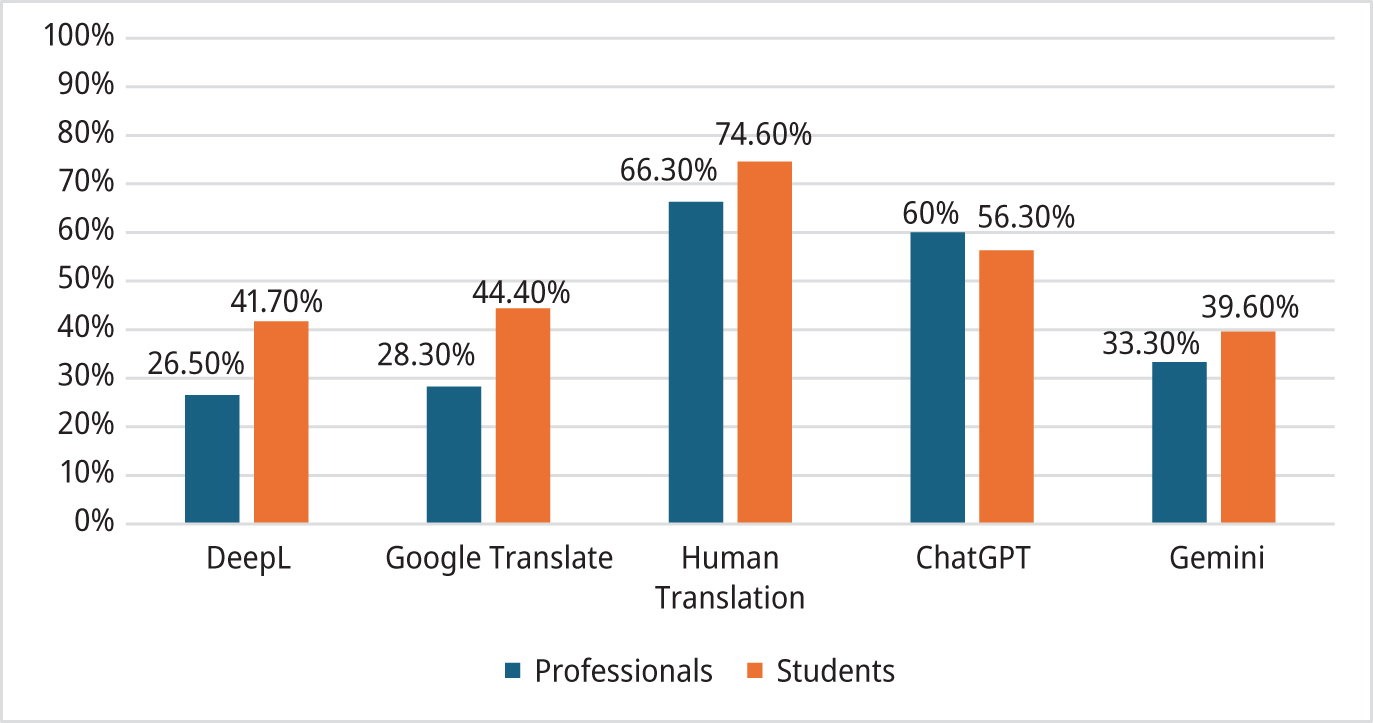

Finally, Figure 2 presents their answers regarding the translation method they find most creative in handling phraseology, based on the results of the five comparative idioms.

Fig. 2: Creativity in MWEs

HT stands out in both groups as the most creative translation method, especially for students. Both students and professionals rate LLMs favourably, with ChatGPT receiving particularly high scores. In fact, professionals feel that NMT systems are not very capable of translating creativity compared to LLMs. Students, by contrast, are less critical of NMT systems and even rate DeepL and Google Translate as narrowly ahead of Gemini. On average, LLMs outperform NMT systems in the translation of creative phraseology for both professionals (46.65% > 27.4%) and students (47.95% > 43.05%).

5 Discussion

This section discusses the findings against benchmark studies to answer the three research questions presented earlier. These results contribute to expanding the data from our previous pilot study (Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez 2024) through the addition of other evaluators and different types of MWEs.

Regarding the morphosyntactic parameters, our findings show a significant trend: some comparative idioms might be replicated morphosyntactically by NMT systems and LLMs. Most likely this is because these systems tend to render more literal structures that closely resemble the source language, as previously observed in several studies (Toral et al. 2018, Zhang et al. 2025). In particular, DeepL and ChatGPT stand out in both study groups.

Despite these data, both the semantic and pragmatic aspects of the comparative idioms are still not fully conveyed by technologies, aligning with the findings by Wu et al. (2025), except for ChatGPT, which achieves satisfactory scores. This is due to the complexity of MWEs, as other studies that have observed the translation of equivalents have pointed out (Corpas Pastor 2003, Dobrovol’skij 2013, Mena Martínez and Sánchez Manzaneres 2015, Mellado Blanco 2023). Our results also highlight the importance of context in the translation of MWEs—which has previously been observed by some scholars (Molina Plaza 2004, Cabezas-García 2021)—since both tools and evaluators have a better understanding of the base meaning of the comparative idioms when handling creativity.

Finally, the novelty parameter emerges as the most human-like among all our data, reinforcing previous findings that underline the impossibility of technologies to fully reach the creative quality of HT (Guerberof-Arenas and Toral 2020, 2022; Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez 2024). These results partially support studies by Li (2024) and Du et al. (2025), since LLMs outperform in novelty in certain comparative idioms, although they still do not measure up to HT output, as in the case of Gemini.

Concerning the performance of these technologies against HT in terms of creativity, a better sophistication of these NMT systems in translating complex MWEs can be seen compared to the study carried out by Noriega-Santiáñez and Corpas Pastor (2023a). In fact, there is a clear evolution in the results rendered by these tools compared to the MT output from previous years (Toral and Way 2015, Carl and Braun 2018, Matusov 2019). However, there is still a shared view in our data that these technologies do not generally overcome HT in terms of consistency and readability. In fact, in contrast to the study by Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez (2024), NMT systems are significantly less creative in translating comparative idioms, especially DeepL. This is in line with studies carried out by Guerberof-Arenas and Toral (2020, 2022), who argue that raw NMT output has not yet reached the level of sophistication achieved by human translation when dealing with creative shifts. Despite studies claiming that LLMs fall short of the quality of HT, since they produce more literal translation solutions (Zhang et al. 2025), our findings suggest that ChatGPT has certain creative potential and even provides creative translations of MWEs in some cases.

Furthermore, professionals are more critical than students in assessing aspects of creativity in comparative idioms. Although several technological systems are preferred by some evaluators, there is still a general reluctance among professionals to fully adopt these technologies in their workflow. These findings fully support studies by Ruffo (2018, 2022) regarding the negative attitude towards MT systems. There is also a tendency for students to use technologies during the translation process, especially creative MWEs, which is in line with the conclusions reached by Noriega-Santiáñez and Corpas Pastor (2023b) about how students deal with challenging phraseology. The digital competencies shown in our study are crucial among undergraduates, as they are identified in the PETRA-E Reference Framework (PETRA-E Framework 2016) together with creative skills.

In conclusion, our findings support the idea that creative phraseology is hard to replicate by machines without professionals who supervise the translation process, as some studies have pointed out (Hadley et al 2022, Li 2024, Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez 2024). However, the collaboration between technologies and humans is more evident in the translation field due to the increasing sophistication of these machines. This current scenario reinforces some of the views advocated in the HCAI framework on enhancing human skills through technologies (Shneiderman 2020, O’Brien 2024, Briva-Iglesias 2024).

6 Conclusion

The results of this study contribute to a reflection on the impact of technologies for the translation of phraseology in literary texts, their potential for literary translators, and the challenges in adopting technologies, especially AI-based tools, into the workflow of translators.

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies that measures creativity output in the translation of creative MWEs rendered by technologies, especially LLMs. Thanks to the formula proposed by Corpas Pastor and Noriega-Santiáñez (2024), this study tentatively unravels the degree of equivalence (adequacy) and novelty that these tools might achieve when translating comparative idioms found in the literature that follow the “as + adjective + as + (the/a/an) noun” structure.

The degree of equivalence determines to some extent the creativity when it comes to the appropriateness regarding the source MWE. For this reason, our data show that a certain degree of creativity is found in technological tools thanks to their adequacy morphosyntactically and semantically, as in the case of DeepL and Google Translate. However, these tools fall short of LLMs when it comes to translating creative phraseology, more specifically, comparative idioms. Among the LLMs, ChatGPT stands out, reaching parameters close to HT or even surpassing it in some instances. However, in terms of novelty embedded in the MWE, no technology is comparable to HT in achieving completely original or innovative results.

Regarding technology adoption, there is still much reluctance among professional translators to integrate these technologies into their workflow. Although LLMs show promising results in our data, there are many ethical and professional reasons for literary translators to not yet make use of them. Furthermore, literary translators seem to be tentatively starting to employ NMT systems for certain tasks. In contrast, students find it natural to use these tools, and there is even a subtle upturn in the adoption of LLMs among the new generation of translators.

Finally, a word of caution. Our study presents several limitations that need to be mentioned. For instance, the number of evaluators is limited (eight subjects), and their profile is unbalanced, which can lead to some bias. In addition, the number of instances— i.e., comparative idioms—was reduced to five. For this reason, we plan to expand this study in different ways. First, we intend to increase the number of evaluators and add a third study group—master’s students in Literary Translation. In addition, we intend to include more language combinations to truly assess the performance of these tools in other languages (i.e., French/Italian>Spanish). Finally, we plan to explore other types of creatively challenging MWEs, such as neologic, discontinuous, or manipulated idioms.

This phraseological study on creativity might help to improve the design of many technological tools when translating MWEs, thereby fostering ethical human-machine collaboration in the field of literary translation. Ultimately, our study aims at both raising awareness of the fundamental role of the literary translator in overcoming the phraseological challenges presented in the literature and the need to foster creativity in future generations of literary translators to effectively handle the complexity of AI-based tools.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by a predoctoral contract granted by the University of Malaga (PPRO-A3.1-2023-01) and it was carried out in the framework of several research projects on multilingual language technologies: VIP II (ref. no. PID2020-112818GB-100/AEI/10.13039/501100011033), RECOVER (ref. no. ProyExcel_00540), DIFARMA (ref. no. HUM106-G-FEDER, 2024–2025), PROMOTUR (ref. no. PID2024-160929OB-I00) and GAMETRAPP (ref. no. TED2021-129789B-I00/ AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ Unión Europea NextGenerationEU/PRTR). We would also like to thank the evaluators for their collaboration.

References

Alcaide-Martínez, Marta. 2023. ChatGPT: The future silver bullet for interpreters? In Gloria Corpas Pastor & Carlos Hidalgo-Ternero (eds.), Proceedings of the International Workshop on Interpreting Technologies SAY IT AGAIN 2023, 23–33. Málaga: INCOMA Ltd. Shoumen.Search in Google Scholar

Boase-Beier, Jean & Michael Holman (eds.). 2016. The Practices of Literary Translation: Constraints and Creativity. London/New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Bowker, Lynne. 2020. Translation technology and ethics. In Kaisa Koskinen & Nike K. Pokorn (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Ethics, 262–278. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003127970-20Search in Google Scholar

Briva-Iglesias, Vicent. 2024. Fostering human-centered, augmented machine translation: Analysing interactive post-editing. Dublin, Ireland: Dublin City University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Cabezas-García, Melania. 2021. The Use of Context in Multiword-Term Translation. Perspectives: Studies in Translation Theory and Practice 31(2). 365–382.10.1080/0907676X.2021.2007272Search in Google Scholar

Carl, Michael & Sabine Braun. 2018. Translation, interpreting and new technologies. In Kirsten Malmkjær (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies and Linguistics, 374–390. London/New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315692845-25Search in Google Scholar

Corpas Pastor, Gloria & Laura Noriega-Santiáñez. 2024. Human versus neural machine translation creativity: A study on manipulated MWEs in literature. Information 15(9). 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15090530Search in Google Scholar

Corpas Pastor, Gloria, Johanna Monti, Ruslan Mitkov & Carlos Manuel Hidalgo-Ternero (eds.). 2024. Recent Advances in Multiword Units in Machine Translation and Translation Technology. Leiden/Boston: Brill/Rodopi.Search in Google Scholar

Corpas Pastor, Gloria, María del Rosario Bautista Zambrana & Carlos Manuel Hidalgo-Ternero. 2021. Sistemas fraseológicos en contraste: enfoques computacionales y de corpus. Granada: Comares.Search in Google Scholar

Corpas Pastor, Gloria. 2001. La creatividad fraseológica: efectos semántico-pragmáticos y estrategias de traducción. Paremia 10. 67–78.Search in Google Scholar

Corpas Pastor, Gloria. 2003. Diez años de investigación en fraseología: Análisis sintáctico-semánticos, contrastivos y traductológicos. Madrid: Vervuert.10.31819/9783865278517Search in Google Scholar

Corpas Pastor, Gloria. 2021. Constructional idioms of ‘insanity’ in English and Spanish: A corpus-based study. Lingua 254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2020.103013Search in Google Scholar

Corpas Pastor, Gloria. 1996. Manual de Fraseología, 1st ed. Madrid: Gredos.Search in Google Scholar

Declercq, Christophe & Gys-Walt Van Egdom. 2023. No more buying cats in a bag? Literary translation in the age of language automation. Tradumàtica. Tecnologies de la Traducció 21. 49–62. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/tradumatica.290Search in Google Scholar

Dobrovol’skij, Dmitrij. 2013. German–Russian idioms online: On a new corpus-based dictionary. Paper presented at the Computational Linguistics and Intellectual Technologies: Proceedings of the Annual International “Dialogue” Conference (Bekasovo, May 29–June 2, 2013).Search in Google Scholar

Du, Shuxiang, Ana Guerberof-Arenas, Antonio Toral, Kyo Gerrits & Josep Marco Borillo. 2025. Optimising ChatGPT for Creativity in Literary Translation: A Case Study from English into Dutch, Chinese, Catalan and Spanish. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.18221.Search in Google Scholar

Elfa, Ali, Mayssa Ahmad & Mina Eshaq Tawfilis Dawood. 2023. Using Artificial Intelligence for enhancing Human Creativity. Journal of Art, Design and Music 2(2). https://doi.org/10.55554/2785-9649.1017Search in Google Scholar

Ferreira, Aline & John W. Schwieter. 2017. Translation and Cognition. In John W. Schwieter & Aline Ferreira (eds.), The Handbook of Translation and Cognition, 3–22. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119241485.ch1Search in Google Scholar

García-Page Sánchez, Mario. 1991. Locuciones adverbiales con palabras idiomáticas. Revista Española de Lingüística 21(2). 233–264.Search in Google Scholar

García-Page Sánchez, Mario. 2008. La comparativa de intensidad: la función del estereotipo. Verba: Anuario galego de filoloxia 35. 143–178.Search in Google Scholar

Grassini, Simone. 2023. Shaping the future of education: Exploring the potential and consequences of AI and ChatGPT in educational settings. Education Sciences 13(7). 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070692Search in Google Scholar

Guerberof-Arenas, Ana & Antonio Toral. 2020. The impact of post-editing and machine translation on creativity and reading experience. Translation Spaces 9. 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00025.gueSearch in Google Scholar

Guerberof-Arenas, Ana & Antonio Toral. 2022. Creativity in translation: Machine translation as a constraint for literary texts. Translation Spaces 11(2). 184–212. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.21004.gueSearch in Google Scholar

Hadley, James Luke, Kristiina Taivalkoski-Shilov, Carlos S. C. Teixeira & Antonio Toral (eds.). 2022. Using technologies for creative-text translation, 1–17. London/New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003094159Search in Google Scholar

Hidalgo-Ternero, Carlos Manuel & Gloria Corpas Pastor. 2020. Estrategias heurísticas con corpus para la enseñanza de la fraseología orientada a la traducción. In Miriam Seghiri Domínguez (coord.), La lingüística de corpus aplicada al desarrollo de la competencia tecnológica en los estudios de traducción e interpretación y la enseñanza de segundas lenguas, 183–206. Frankfurt am Main:Peter LangSearch in Google Scholar

Holman, Michael & Jean Boase-Beier. 2016. Introduction: Writing, rewriting and translation – Through constraint to creativity. In Jean Boase-Beier & Michael Holman (eds.), The practices of literary translation, 1–17. London/New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315539737Search in Google Scholar

Kenny, Dorothy & Marion Winters. 2020. Machine translation, ethics and the literary translator’s voice. Translation Spaces 9(1). 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00024.kenSearch in Google Scholar

Leal Riol, María Jesús. 2008. Contraste fraseológico: Similitudes y diferencias existentes entre las unidades fraseológicas del inglés y del español. ES. Revista de Filología Inglesa 29. 103–116.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Qi. 2024. Bridging languages: The potential and limitations of AI in literary translation—A case study of the English translation of A Pair of Peacocks Southeast Fly. Advances in Humanities Research 8. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.54254/2753-7080/8/2024091Search in Google Scholar

Matusov, Evgeny. 2019. The challenges of using neural machine translation for literature. In James Luke Hadley et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the Qualities of Literary Machine Translation, 10–19. Dublin: European Association for Machine Translation.Search in Google Scholar

Mellado Blanco, Carmen. 2012. Las comparaciones fijas en alemán y español: Algunos apuntes contrastivos en torno a la imagen. Linred: Lingüística en la Red 10. 1–32. Universidad de Alcalá.Search in Google Scholar

Mellado Blanco, Carmen. 2022. Productive Patterns in Phraseology and Construction Grammar: A Multilingual Approach. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110520569Search in Google Scholar

Mellado Blanco, Carmen. 2023. ¡Lo que yo de cura! El «antiprototipo» en las construcciones comparativas intensificadoras desde un punto de vista construccionista. Revista de Filología 46. 313–333. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.refiull.2023.46.16Search in Google Scholar

Mena Martínez, Florentina & Carmen Sánchez Manzanares. 2015. Los usos creativos de las UF: Implicaciones para su traducción (inglés–español). In Germán Conde Tarrío, Pedro Mogorrón Huerta & David Prieto García-Seco (eds.), Enfoques actuales para la traducción fraseológica y paremiológica: Ámbitos, recursos y modalidades, 59–76. Madrid: Instituto Cervantes.Search in Google Scholar

Ministerio para la Transformación Digital y de la Función Pública. 2023. Tecnologías del Lenguaje.https://plantl.digital.gob.es/tecnologias-lenguaje/Paginas/tecnologías lenguaje.aspx (accessed 25 March 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Mitkov, Ruslan. 2022. The Oxford Handbook of Computational Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199573691.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Molina Plaza, Silvia. 2004. La traducción de las unidades fraseológicas inglés- español: el caso de las colocaciones y las frases idiomáticas. In Luis González & Pollux Hernúñez (eds.), Las palabras del traductor. Actas del II Congreso: El español, lengua de traducción. 427–444. Toledo: Instituto Cervantes.Search in Google Scholar

Monti, Johanna; Gloria Corpas Pastor, Ruslan Mitkov, & Carlos Manuel Hidalgo-Ternero (eds.). 2024. Recent advances in multiword units in machine translation and translation technology. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.366Search in Google Scholar

Moorkens, Joss. 2022. Ethics and machine translation. In Dorothy Kenny (ed.), Machine Translation for Everyone: Empowering Users in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, 121–140. Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Noriega-Santiáñez, Laura & Gloria Corpas Pastor. 2023a. La traducción del género fantástico mediante corpus y otros recursos tecnológicos: a propósito de “The City of Brass”. Moenia. Revista Lucense de Lingüística y Literatura 29. 1–30. https://doi.org/10.15304/moenia.id8491Search in Google Scholar

Noriega-Santiáñez, Laura & Gloria Corpas Pastor. 2023b. Machine vs human translation of formal neologisms in literature: Exploring e-tools and creativity in students. Tradumàtica. Tecnologies de la Traducció 21. 233–264. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/tradumatica.338Search in Google Scholar

O’Brien, Sharon. 2023. Human-centered augmented translation: Against antagonistic dualisms. Perspectives 32(3). 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2023.2247423Search in Google Scholar

Pamies Bertrán, Antonio. 2005. Comparación estereotipada y colocación en español y en francés. In Juan de Dios Luque Durán & Antonio Pamies Bertrán (eds.), La creatividad en el lenguaje: colocaciones idiomáticas y fraseología, 469–484. Granada: Universidad de Granada.Search in Google Scholar

Pérez, Matías Agustín & Samira Elizabeth Robador Papich. 2023. El futuro de la Educación Universitaria con ChatGPT. Paper presented in XVIII Congreso Nacional de Tecnología en Educación y Educación en Tecnología, Universidad Nacional de Hurlingham, 13 July 2023.Search in Google Scholar

PETRA-E Framework. 2016. Framework of reference for the education and training of literary translators. Utrecht: PETRA-E. Available at: https://literairvertalen.org/framework (accessed 30 March 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Rashidi, Raziyeh & Neda Fatehi Rad. 2021. Creativity and literary translation: Analyzing the relationship between translators’ creativity and their translation quality. Journal of Language, Culture, and Translation 4(1). 1–24.Search in Google Scholar

Rojo, Ana & Meseguer, Purificación. 2018. Creativity and Translation Quality: Opposing Enemies or Friendly Allies? Hermes – Journal of Language and Communication in Business 57. 79–90. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v0i57.106202Search in Google Scholar

Ruffo, Paola. 2018. Human-Computer Interaction in Translation: Literary Translators on Technology and Their Roles. Paper presented at the 40th Conference Translating and the Computer, London, UK, 15–16 November.Search in Google Scholar

Ruffo, Paola. 2022. Collecting literary translators and narratives: Towards a new paradigm for technological innovation in literary translation. In James Luke Hadley, Kristiina Taivalkoski-Shilov, Carlos S.C. Teixeira & Antonio Toral (eds.), Using Technologies for Creative-Text Translation, 18–39. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Sawyer, Robert Keith & Danah Henriksen. 2023. Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation, 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197747537.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Schön, Eva-Maria, Michael Neumann, Christina Hofmann-Stölting, Baeza-Yates, Ricardo & Maria Rauschenberger. 2023. How are AI assistants changing higher education? Frontiers in Computer Science 5. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2023.1112184Search in Google Scholar

Shneiderman, Ben. 2020. Human-centered artificial intelligence: Three fresh ideas. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction 12(3). 109–124. https://doi.org/10.17705/1thci.00131Search in Google Scholar

Sidoti, Rossana & Domenico Daniele Lapedota (eds.). 2023. Nuevas aportaciones a las investigaciones en fraseología, paremiología y traducción. Berlin/Bern/Bruxelles/New York/Oxford/Warszawa/Wien: Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/b21059Search in Google Scholar

Sinclair, John. 2007. Language and computing, past and present. In Khurshid Ahmad & Margaret Rogers (eds.), Evidence-Based LSP: Translation, Text and Terminology, 21–52. Bern: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Taivalkoski-Shilov, Kristiina. 2018. Ethical issues regarding machine(-assisted) translation of literary texts. Perspectives 27. 689–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2018.1529420Search in Google Scholar

Toral, Antonio & Andy Way. 2014. Is Machine Translation Ready for Literature? Paper presented at the Translating and the Computer 36. London, UK, 27–28 November.Search in Google Scholar

Toral, Antonio & Andy Way. 2015. Machine-Assisted Translation of Literary Text: A Case Study. Translation Spaces, 4(2). 240–267. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.4.2.04tor.Search in Google Scholar

Toral, Antonio & Andy Way. 2018. What level of quality can neural machine translation attain on literary text? In Joos Moorkens, Sheila Castilho, Federico Gaspari & Stephen Doherty (eds.), Translation Quality Assessment: From Principles to Practice, 1st edn., 263–287. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-91241-7_12Search in Google Scholar

Voigt, Rob & Dan Jurafsky. 2012. Towards a literary machine translation: The role of referential cohesion. Paper presented at the NAACL-HLT 2012 Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Literature. Montreal, Canada: Association for Computational Linguistics, 8 June.Search in Google Scholar

Way, Andy, Andrew Rothwell & Roy Youdale. 2023. Why more Literary Translators should embrace Translation Technology. Revista Tradumàtica: traducció i tecnologies de la informació i la comunicació 21. 87–102. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/tradumatica.344Search in Google Scholar

Webster, Rebecca, Margot Fonteyne, Arda Tezcan, Lieve Macken & Joke Daems. 2020. Gutenberg goes neural: Comparing features of Dutch human translations with raw neural machine translation outputs in a corpus of English literary classics. Informatics 7(3). 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics7040032Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Minghao, Jiahao Xu, Yulin Yuan, Gholamreza Haffari, Longyue Wang, Weihua Luo & Kaifu Zhang. 2025. (Perhaps) Beyond human translation: Harnessing multi-agent collaboration for translating ultra-long literary texts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.11804. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.11804Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Zhuohao, Danwen Ji, Kaiwen Yu, Xianxu Zeng, Dingming Wu & Mohammad Shidujaman. 2021. AI creativity and the human–AI co-creation model. In Masaaki Kurosu (ed.), Human-Computer Interaction. HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 12762, 171–190. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78462-1_13Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Ran, Wei Zhao & Steffen Eger. 2025. How good are LLMs for literary translation, really? Literary translation evaluation with humans and LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.18697.10.18653/v1/2025.naacl-long.548Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial (English)

- Editorial (Deutsch)

- Articles

- Phraseology and Figurative Language: Some Basic Concepts and Future Prospects

- Idiomatische Mehrwortverbindungen im Fremdsprachenunterricht – Vorschlag einer Selektion für Deutsch lernende Polen aus der Perspektive der plurilingualen Fremdsprachendidaktik

- Bridging the Gap: Using Embodiment and CMT Strategies to Improve Idiom Understanding Among Moroccan EFL Students

- Measuring Creative Phraseology in Literature: Machine Translation Systems Versus Large Language Models

- Addition in Anglo-American anti-Proverbs about Money

- Where there is (there’s) a will, there is (there’s) a way

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial (English)

- Editorial (Deutsch)

- Articles

- Phraseology and Figurative Language: Some Basic Concepts and Future Prospects

- Idiomatische Mehrwortverbindungen im Fremdsprachenunterricht – Vorschlag einer Selektion für Deutsch lernende Polen aus der Perspektive der plurilingualen Fremdsprachendidaktik

- Bridging the Gap: Using Embodiment and CMT Strategies to Improve Idiom Understanding Among Moroccan EFL Students

- Measuring Creative Phraseology in Literature: Machine Translation Systems Versus Large Language Models

- Addition in Anglo-American anti-Proverbs about Money

- Where there is (there’s) a will, there is (there’s) a way

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews