Abstract

Quantum chemistry plays a fundamental role in unraveling the mechanisms by which biological systems sense and use light, driving functions such as light harvesting and energy conversion, and photoreception and signaling. In this Perspective, we first present the fundamental physical principles underlying the light-induced biological functions. We then focus on the key theoretical frameworks and multiscale modeling strategies based on quantum chemistry that enable a detailed, atomistic description of the processes initiating the biological response to light. Special emphasis is placed on three fundamental photophysical and photochemical processes (excitation energy transfer, photochemical reactions, and electron transfer) which form the core of photoactivation mechanisms in biological systems. By highlighting the advances and challenges associated with the quantum chemical modeling, we demonstrate its essential contribution to deepening our understanding of photoinduced biological function and point to future directions for methodological innovation.

1 Introduction

The 2025 International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ) marks the centennial of the foundational development of quantum mechanics. IYQ’s mission is to use this milestone to increase public awareness of the fundamental role quantum science plays across diverse domains of knowledge. By following this mission, in this contribution we highlight the fundamental role of quantum science, and in particular quantum chemistry, in advancing our understanding of how light interacts with proteins to initiate a wide range of biological functions.

A large part of our current understanding of protein–light interactions and their mechanisms of action has been achieved thanks to the combined application of structural and spectroscopic approaches. Advances in high-resolution X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have provided detailed structural insights into a wide range of photoresponsive systems. Complementarily, time-resolved spectroscopic techniques have allowed us to monitor the dynamics of light-induced processes in real time. However, a complete and coherent understanding of the functional mechanisms remains elusive. Structural data are available for only a limited subset of systems and/or states involved in light-activated processes, and time-resolved spectroscopic techniques typically provide only portions of these dynamic events. As a result, significant gaps persist in our knowledge of how light-induced processes are generated, propagated, and regulated at the molecular level.

To overcome these limitations, the integration of experimental data with atomistic simulations has become an indispensable strategy. Among these, quantum chemical modeling plays a fundamental role by offering direct access to the electronic structure changes, excited-state dynamics, and photochemical/photophysical pathways that are at the core of light-induced biological processes. Moreover, the coupling of quantum mechanical (QM) methods with classical potentials from Molecular Mechanics (MM), through hybrid QM/MM approaches, and their integration with dynamical frameworks enables the exploration of phenomena across multiple spatial and temporal scales, from femtosecond electronic transitions to large-scale protein conformational dynamics. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 The synergy between quantum chemistry-based multiscale modeling and experimental observations is becoming increasingly essential for building a comprehensive and predictive framework of light-activated function across biological systems. 10 , 11 , 12

In this context, here we focus on two distinct classes of photoactivated biological functions, which can be broadly categorized as light harvesting and energy conversion, 13 , 14 , 15 and photoreception and signaling, respectively. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 A third light-induced function, developed by various organisms, will not be explicitly considered here. This function involves photoenzymes, which harness light to drive chemical reactions within a photocatalytic framework. 20 , 21 Surprisingly, evidence for such use of light in nature remains scarce. The rarity of photoenzymes, compared to other enzymatic systems, largely reflects specific ecological and evolutionary constraints.

We begin by outlining the fundamental principles that govern the mechanisms underlying the two selected biological functions. Subsequently, we review the principal theoretical frameworks and methodological strategies employed in quantum chemistry–based multiscale modeling of the light-induced processes. In particular, we focus on the three fundamental photophysical and photochemical processes that form the basis of the various photoactivation mechanisms: excitation energy transfer (EET), photochemical reactions, and electron transfer (ET). For each process, we highlight how multiscale approaches integrate electronic structure methods with environmental effects to achieve an accurate and predictive description of the complex dynamics involved.

2 The light induced processes in proteins

2.1 Light harvesting & energy conversion

The terms light harvesting (LH) and energy conversion in photosynthetic systems refer to two distinct but sequential processes used in the so-called light-phase of photosynthesis. Both are essential for transforming sunlight into chemical energy, but they involve different molecular components, timescales, and physical principles. Light harvesting is the initial step of photosynthesis in which photons are captured and funneled to the reaction center (RC). Energy conversion refers instead to the transformation of the harvested excitation energy into a stable chemical form via charge separation and electron transport in the reaction center. Both these sequential processes are realized in photosystems, multisubunit membrane protein supercomplexes containing at the core, the RC and at peripheries, the LH antennas 22 , 23 (see Fig. 1).

Representation of photosystem II (PSII): (a) the composition in terms of antennas and reaction center (RC). (b) The monomer of the major antenna, the trimeric LHCII and the arrangement of its pigments, Chlorophyll a (light green), Chlorophyll b (green) and carotenoids (Lutein in orange and neoxanthin in violet); (c) The reaction center and the arrangement of the set of pigments involved in the primary electron transfer reaction (Chlorophyll a in light green, Pheophytin in cyano and β-Carotene in yellow).

The core structures of RCs are highly conserved in photosynthetic organisms. Instead, a wide diversity of antenna systems is found, and in many cases, the classification of these organisms is closely linked to the specific types of antenna complexes they possess. 13 , 14 , 24 In all cases, the antenna system does not carry out chemical reactions; instead, it absorbs light and uses energy transfer processes to move the excitation energy in space toward the core of the photosystem and ultimately to the reaction center. This physical process relies on excitonic coupling between pigments, which are typically bound to proteins in highly specific arrangements. In addition to chlorophylls, which are the primary pigments in plants and other oxygenic photosynthetic organisms, a variety of other antenna pigments are employed across different photosynthetic systems. Bacteriochlorophylls serve a similar light-harvesting role in most anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria, while bilins, linear, open-chain tetrapyrrole pigments, are characteristic of antenna complexes known as phycobilisomes present in read algae and cyanobacteria. Furthermore, all known native photosynthetic organisms possess ancillary pigments known as carotenoids (see Fig. 1). In oxygenic species, carotenoids typically feature ring structures at both ends of the conjugated backbone, and many contain oxygenated functional groups. These pigments play critical roles not only in light harvesting but also structural stabilization of antenna complexes and photoprotection. 25 , 26 Because sunlight is a relatively dilute energy source, the number of antennas associated with each reaction center is large. Under stress conditions, such as high light intensity, these antennas can absorb more energy than the system can effectively utilize, potentially causing photodamage. To mitigate this, both antenna complexes and reaction centers are equipped with regulatory, protective, and repair mechanisms. 27 , 28 , 29

The reaction center is a multisubunit protein complex where charge separation (CS) takes place. In the RC of photosystem II (PSII), the set of pigments responsible for the conversion of excitation energy into CS is composed by four chlorophylls and two pheophytins (see 1(c)). Moroever, various additional cofactors are present including carotenoids, quinones and the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC). To avoid energy loss through recombination (where the electron is transferred back and the energy is converted into heat and rapidly dissipated), the system employs a rapid series of secondary electron transfer steps. These steps outcompete recombination by spatially separating charge across the membrane within less than a nanosecond. Subsequent slower processes stabilize and convert this charge separation into usable chemical energy. 23 , 30

Despite the detailed structural and spectroscopic studies we have achieved so far for photosystems, several fundamental questions remain open. A central issue is how EET occurs with such high efficiency across complex pigment–protein architectures under physiological conditions. 31 , 32 , 33 Furthermore, how protein dynamics and structural fluctuations modulate energy landscapes and guide energy flow through these networks is still not fully resolved. This includes the role of the environment in dynamically tuning pigment site energies and couplings. Regarding electron transfer in reaction centers, one major puzzle is why ET proceeds asymmetrically through only one branch, despite the structural symmetry of cofactors. The role of the protein environment in tuning redox potentials and controlling ET dynamics through local electrostatics, hydrogen bonding, and conformational fluctuations is also not fully understood.

2.2 Photoreception & signalling

The terms photoreception and signaling are closely related in the context of light-activated biological processes, but they refer to distinct stages in the sequence of events. Photoreception is the initial detection and absorption of light by a protein embedding a chromophore which acts as a switch. Signaling instead refers to the cascade of biochemical and physiological events following the initial photoreception, and ultimately leading to a biological response.

The mechanisms used for photoreceptor and for signalling vary across organisms and functions. 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 Typical examples are light-induced photoisomerization of the embedded chromophore or light-induced electron transfer. Typical examples of signaling mechanisms are instead conformational changes that modulate the binding affinity or enzymatic activity of the system.

To explain in more details, here we focus on two largely diffused photoreceptors, Phytochromes and Cryptochromes.

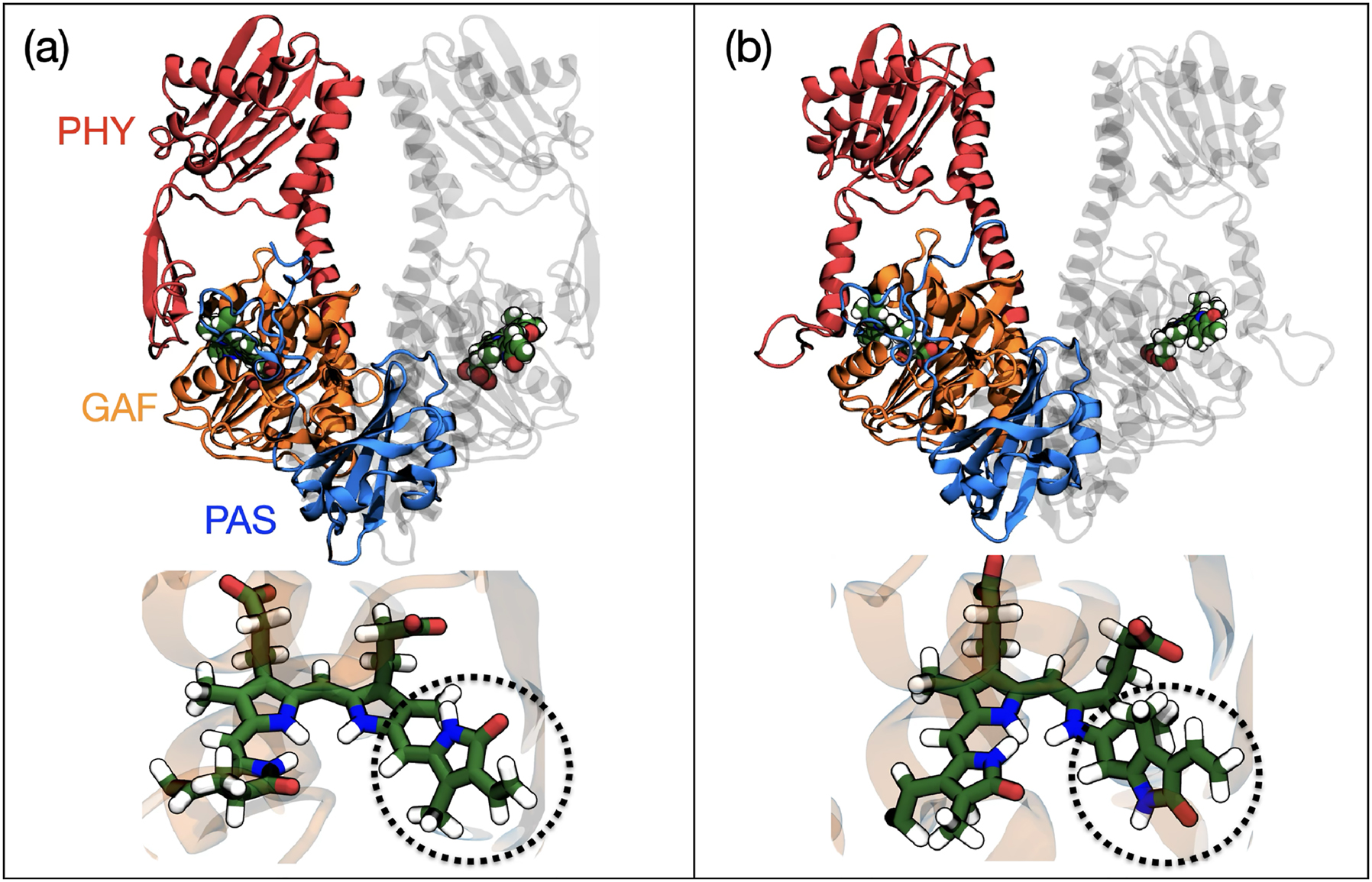

Phytochromes are light-sensitive proteins in plants (and some bacteria and fungi) that act as photoreceptors for red and far-red light. They play a central role in regulating light-dependent development and behavior. 34 , 38 Phytochromes function as reversible molecular switches. For example, in plants they are used to sense the red/far-red light ratio, which varies with canopy cover, time of day, and seasons. This allows plants to distinguish between light conditions and activate/promote different behaviors. Phytochromes are typically homodimers where each monomer is composed of a generally conserved photosensory module made of three domains (PAS–GAF–PHY). The photosensory module embeds a chromophore, a linear tetrapyrrole (bilin) covalently attached to the GAF domain via a cystein residue (see Fig. 2). By absorbing light, the chromophore undergoes a Z → E isomerization of a double bond. This causes a conformational change in the protein, particularly in the PHY tongue, activating downstream signaling.

Schematic representation of the (a) dark and (b) light activated states of Phytochrome in the Deinococcus bacterium and the embedded bilin. The dotted circle indicates the region of the molecule where photoisomerization occurs.

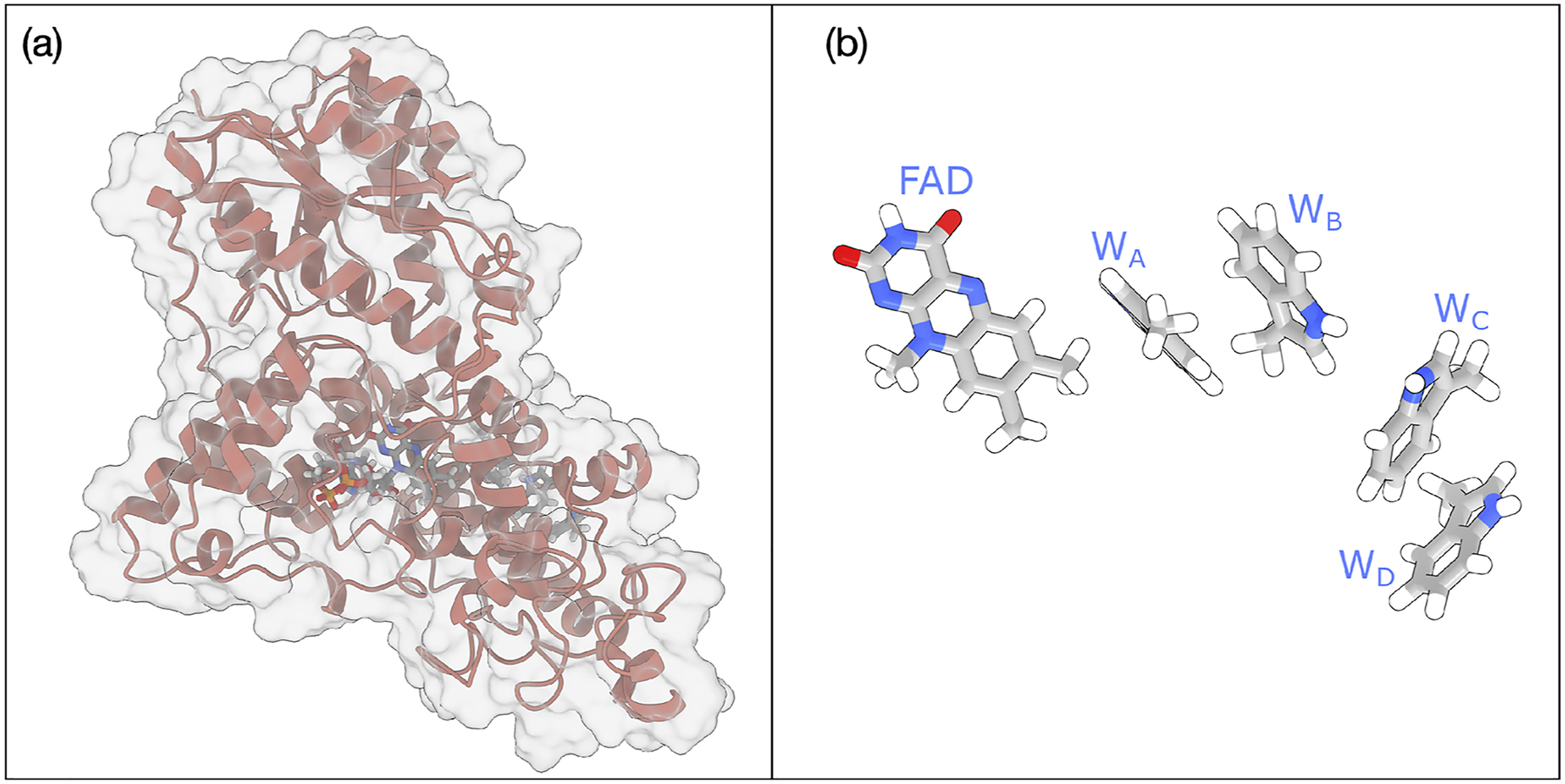

A different mechanism of action is represented by the blue-light photoreceptors known as cryptochromes (CRY). Cryptochromes are photo sensory receptors that regulate several vital biological functions such as growth, development and flowering as well as the regulation of the circadian clock in plants and animals. 18 Structurally, CRY contains a conserved N-terminal photolyase-related domain that binds to flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and a C-terminal domain of variable length. Upon blue light irradiation, electron transfer from a close-by tryptophan to flavin occurs allowing a fast (hundreds of fs) initial charge separation and subsequent stabilization of the radical species through a chain of tryptophans (see Fig. 3). These stabilized radical pairs are thought to serve in triggering a conformational change. This change results in the formation of homodimers or heterodimers with CRY-interacting proteins.

Schematic representation of (a) Cryptochrome 4 widely thought to be responsible for the magneto-reception of migratory birds and (b) the FAD and the four tryptophan residues involved in the ET chain.

Cryptochromes have also been proposed as actors in magnetoreception, a mechanism to underlie spatial orientation in migratory birds relative to Earth’s magnetic field. 39 In the proposed cryptochrome-based model, blue light absorption by the FAD cofactor initiates photoreduction, generating a light-induced radical pair. The magnetic sensitivity arises from the spin-dependent dynamics of this radical pair, which influence downstream biochemical or neuronal responses involved in orientation and navigation.

Despite the significant progress achieved so far, the mechanistic understanding of photoreceptors at molecular level remains incomplete. One major open question concerns the ultrafast photochemical events, such as isomerization and charge rearrangement, that follow photon absorption and occur on femtosecond to picosecond timescales. 40 How these events are influenced by the protein environment, including hydrogen bonding and electrostatics, remains poorly defined. Another key challenge is elucidating how localized changes at the chromophore site are converted into global conformational changes that activate downstream signaling domains. The structural pathways that mediate this allosteric communication, and whether conserved dynamic motifs exist across photoreceptor families, are still not fully resolved.

3 Quantum chemistry-based strategies

The photoactivated biological functions described in the previous section are based on three primary light-induced processes: excitation energy transfer (EET), photochemical reactions, and electron transfer (ET). In this section, we present the main theoretical and methodological aspects of their simulations when quantum chemistry based strategies are used. Energy transfer, central to light harvesting in photosystems, involves excitation migration among pigments and is modeled using excitonic theories combined with classical or quantum dynamics. Photochemical reactions, typical of many photoreceptors, involve structural changes in the chromophore upon excitation and require quantum chemical methods capable of treating excited-state nonadiabatic dynamics. Electron transfer occurs both in reaction centers and in some photoreceptors, where it may replace photochemistry. Its simulation involves computing redox potentials, electronic couplings, and reorganization energies.

3.1 Energy transfer

Computational studies of energy transfer in photosystems rely on a hierarchy of methods, from quantum chemistry for accurate pigment-level descriptions, to exciton models and open quantum system theory for energy migration, and molecular simulations to incorporate environmental dynamics.

At the pigment level, quantum chemical methods such as time-dependent Density Functional Theory (TDDFT), multiconfigurational approaches, or semiempirical models are employed to compute excitation energies of the single pigments (also called site energies) and electronic couplings between these excitations. 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 It is crucial that the chosen QM method accurately captures not only the excitation energy associated with the electronic transition of interest but also its underlying electronic character. For instance, in the case of chlorophylls, single-reference methods such as TDDFT are generally adequate due to the relatively straightforward nature of their lowest-energy excitation, e.g. the one involved in the light-harvesting. In contrast, for other classes of pigments such as carotenoids, multireference methods are often required to account for the more complex electronic structure involved in their excited states.

To account for the influence of the protein matrix and surrounding environment, these calculations are typically done within a hybrid QM/MM framework. While electrostatic embedding is often sufficient for capturing the primary environmental effects, a more accurate and physically complete description is achieved with polarizable embedding. 5 , 46 , 47 Mutual polarization between the chromophores and their environment can significantly influence site energies and, more critically, the excitonic couplings. This is particularly important because a polarizable environment can mediate the Coulomb interaction between transition densities, thereby altering the electronic couplings that govern energy transfer dynamics.

Once the site energies and electronic couplings are determined, they can be used to construct a Frenkel exciton Hamiltonian. 48 In this framework, a system composed of N pigment molecules is considered, where each pigment (or site) is modeled as a two-level system – either in its ground or excited electronic state and inter-site charge transfer is neglected. Under these assumptions, the excitonic Hamiltonian takes the form:

where ɛ n is the excitation (site) energy of pigment n and V nm the electronic coupling between sites n and m, usually arising from Coulombic interaction.

The coupling can be primarily attributed to Coulomb interactions between transition densities localized in the two chromophores. When the separation between the two chromophores is large compared to their spatial extent, the Coulombic coupling can be approximated by the dipole–dipole interaction (from now on atomic units will be used):

where μ m and μ m are the transition dipole moments of chromophores n and m, R nm = R n − R m is the vector connecting the two chromophores and R nm = |R nm | the distance between them. In this equation, ϵ ∞ denotes the optical dielectric constant, which accounts for the response of the environment surrounding the two chromophores, modeled as a continuum dielectric medium. In more accurate treatments, environmental effects are incorporated through polarizable embedding QM/MM approaches, which account for the modulation of transition densities and the screening of their Coulomb interactions. 42 , 49 In addition to Coulomb interactions, the coupling should also contain contributions from exchange interactions. 50 However, these contributions are typically much weaker and decay more rapidly with distance compared to the Coulombic terms, and are therefore often neglected.

By diagonalizing the excitonic Hamiltonian H exc we obtain the excitons, i.e. the delocalized electronic excitation states that arise from coupling between local excitations on pigment sites. These excitonic states are expressed as linear combinations of site-localized states:

where |K⟩ is the K-th exciton state (with energy E K ) and c nK is the coefficient giving the contribution of site n to exciton K. If the coupling V nm is small compared to energetic difference |ɛ n − ɛ m |, excitons are localized, and |K⟩ ≈ |n⟩. On the contrary, if coupling dominates, excitons are delocalized over many sites and carry wave-like character.

Starting from the excitonic Hamiltonian, different dynamical theories can be applied to simulate the energy transfer processes, 51 , 52 ranging from Förster and Redfield theory to more advanced treatments like modified Redfield or numerically exact methods such as the Hierarchical Equations of Motion. To apply these models it is necessary to add the effects of nuclear motions of both the pigments and the external protein and solvent. Generally these motions are approximated in terms of a ”bath” of quantum harmonic oscillators which are coupled to the electronic degrees of freedom of the pigments through the electron-bath coupling. The electron-bath coupling quantifies how the energy levels of electronic states are modulated by nuclear motions. It introduces both dephasing (loss of quantum coherence) and relaxation (redistribution of population among excitonic states) and it governs the transition between coherent and incoherent regimes of energy transfer. A stronger electron-bath coupling with respect to the electronic couplings lead to incoherent energy transfer, while weaker electron-bath coupling support coherent (wave-like) excitation transport.

Mathematically, a Hamiltonian of the form:

is used, where H bath is the bath of quantum oscillators, and H exc-bath is the coupling between the excitonic system and the bath.

The effects of electron-bath coupling are accounted for in terms of the spectral density function J(ω), which describes how strongly the electronic system couples to different vibrations in the system. The spectral density can be defined in terms of the autocorrelation function of the excitation energy fluctuations. Let δɛ(t) = ɛ(t) − ⟨ɛ⟩ be the fluctuation of the excitation energy of a pigment around its mean value, caused by nuclear motions. The autocorrelation function of these fluctuations is:

Then, the spectral density J(ω) is related to the imaginary part of the Fourier transform of the quantum correlation function, but in many simulations and semi-classical approximations, it is directly constructed from the classical autocorrelation function as: 53

where

Alternatively, spectral densities can be computed using normal-mode analysis, as proposed in semiclassical approaches. 55 This method assumes that both the ground and excited-state potential energy surfaces share the same harmonic shape but differ in their equilibrium geometries. Under this approximation, the spectral density is given by:

where ω

k

and λ

k

are the frequency and the reorganization energy along the kth normal mode, respectively. The reorganization energy along each normal mode is determined using the expression

Electron-bath coupling is central to understanding and modeling EET because it governs how the vibrations modulates electronic excitations, thereby influencing the balance between coherent and incoherent transport, relaxation rates, and spectroscopic signatures.

Another fundamental quantity in shaping excitonic behavior and energy transfers is the static disorder due to the fluctuations in the interactions with the environment. To illustrate its fundamental impact, we can compare how static disorder influences the Förster and Redfield regimes. 51 , 56

In the Förster regime, where electronic coupling is weak, the rate of energy transfer from site i to site j is given by:

where the integral represents the spectral overlap between the donor fluorescence spectrum Φ i (ω) and the acceptor absorption spectrum A j (ω). Static disorder modifies the rate primarily by broadening and reshaping these spectra, thereby altering the extent of spectral overlap and, consequently, the efficiency of energy transfer.

In the opposite limit, e.g. when the coupling is strong, a Redfield regime applies and the transfer is between exciton states: 57

where K, L denote the exciton states involved in the transfer, c iK and c iL are the corresponding excitonic coefficients and ω KL = (ω L − ω K ) their energy difference. In this case, the effects of the static disorder is through the composition of the excitons represented by the excitonic coefficients.

In many cases, neither the Förster nor the Redfield regime alone adequately describes excitation energy transfer, necessitating a hybrid Redfield–Förster approach. In this framework, the excitonic Hamiltonian is partitioned into blocks, each representing a group of strongly coupled pigments. Within each block, strong couplings lead to exciton delocalization, while weaker inter-block couplings are treated perturbatively and drive energy transfer between blocks. 49 , 58 As a result of this partitioning, exciton states are localized within individual blocks. Energy relaxation among excitons within the same block is described using Redfield theory, capturing coherent population dynamics among delocalized states. In contrast, inter-block transfers are treated with the Generalized Förster (GF) approach, where transitions occur incoherently between excitons. The EET rate from exciton K to L, belonging to different blocks, is given by:

In this context, disorder can influence energy transfer by combining the effects typically associated with both the Redfield and Förster regimes. Moreover, it can perturb the partitioning of the system into blocks of strongly coupled pigments, potentially altering the definition and stability of excitonic compartments.

Neglecting static disorder in EET simulations can therefore result not only in quantitative inaccuracies but also in qualitative artifacts. To properly account for these effects, it is necessary to recalculate the excitonic Hamiltonian over an ensemble of system configurations, typically sampled from a sufficiently long molecular dynamics (MD) trajectory – potentially extending to the microsecond timescale. However, achieving such timescales with fully QM or even hybrid QM/MM methods is computationally prohibitive. As a result, most studies rely on classical MD simulations using molecular mechanics (MM) force fields to generate the structural ensembles required for statistically meaningful modeling of disorder. 43

3.2 Photochemistry

The computational approaches commonly used to study photoreceptors differ from those described in the previous section for antenna complexes. In this context, the key event is usually an ultrafast, localized photochemical reaction, such as a photoisomerization, occurring on a single chromophore. 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 To accurately describe such light-induced dynamics, the most suitable and widely adopted method is mixed quantum–classical nonadiabatic dynamics. 64 , 65 , 66 , 67

Within this framework, the nuclei are treated classically, evolving according to Newtonian mechanics on a given potential energy surface (PES), while the electronic subsystem is described quantum mechanically through the time-dependent Schrödinger equation:

where M I is the mass of nucleus I, R I (t) is the time-dependent position of nucleus I, E j (R) is the potential energy of the j-th adiabatic electronic state at nuclear geometry R.

Expanding |Ψ(t)⟩ in the adiabatic basis {|ψ j (R(t))⟩}, the wavefunction becomes:

Substituting into the Schrödinger equation leads to the coupled equations for the electronic amplitudes A j (t):

where d

jk

= ⟨ψ

j

|∇

R

|ψ

k

⟩ is the nonadiabatic coupling vector between adiabatic states j and k, and

Among the most commonly used formulations of the mixed quantum–classical methods is the trajectory-based approach known as fewest switches surface hopping (FSSH) which was originally developed by Tully. 68 The method allows probabilistic hops between PESs to account for nonadiabatic transitions, ensuring a statistically correct description of population transfer among electronic states. Upon a hop, the nuclear kinetic energy is adjusted (typically by rescaling the velocities along the direction of nonadiabatic coupling) to conserve total energy. If there is insufficient kinetic energy to perform the hop (i.e., the hop is “frustrated”), the trajectory continues on the current surface. FSSH has been successfully applied to investigate ultrafast photoactivation mechanisms in photoreceptors such as rhodopsins 69 , 70 and phytochromes. 71 , 72 In these studies the effects of protein or solvent environments are generally included using within a QM/MM framework.

The success of independent-trajectory methods like surface hopping can be explained recalling that in many photochemical processes, quantum nuclear effects such as interference, tunneling, and zero-point energy can often be neglected. However, quantum decoherence, e.g. the loss of coherence between wave packets evolving on different potential energy surfaces, cannot always be ignored. 73

Because surface hopping treats nuclear motion classically and electronic transitions probabilistically, individual trajectories do not represent the real physical behavior. To recover statistically meaningful quantum observables, such as state populations or branching ratios, averaging over many trajectories is essential (see Fig. 4). The ensemble is needed to reproduce quantum populations through the aggregate of stochastic surface switches (hops), to capture the diversity of initial conditions (e.g., nuclear geometries, velocities) due to quantum zero-point energy and thermal distributions, and to compensate for approximations, such as the absence of nuclear quantum effects or decoherence corrections, by statistical sampling.

![Fig. 4:

Comparison between the dynamics of (a) a quantum mechanical wave packet and (b) its semiclassical approximation as described by trajectory surface hopping. Adapted and revised from Ref. 73]](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2025-0517/asset/graphic/j_pac-2025-0517_fig_004.jpg)

Comparison between the dynamics of (a) a quantum mechanical wave packet and (b) its semiclassical approximation as described by trajectory surface hopping. Adapted and revised from Ref. 73]

The need to generate a large number of trajectories in surface hopping simulations poses a significant limitation due to the high computational cost. To address this challenge, semiempirical quantum chemical methods have proven to be a valuable solution. Semiempirical methods approximate the electronic structure using parametrized Hamiltonians, allowing substantial reductions in computational demand while maintaining an explicit quantum mechanical description of the key excited states. 74 When combined with surface hopping nonadiabatic dynamics, these methods offer a powerful and practical strategy for investigating excited-state processes in proteins, especially in cases where ab initio approaches are computationally unfeasible. 64 , 75 In this context, semiempirical techniques enable the on-the-fly calculation of potential energy surfaces, gradients, and nonadiabatic couplings for systems of considerable size. Furthermore, their integration within a QM/MM framework provides an efficient and effective approach for accurately modeling chromophores embedded in complex protein environments. Although semiempirical methods enable extensive excited-state dynamics simulations, they are limited by their parametrization, restricted transferability, and reduced accuracy in describing electronically excited states. However, when carefully benchmarked against high-level calculations or experimental data, the combination of surface hopping and semiempirical quantum chemistry remains one of the most versatile and effective strategies for elucidating detailed mechanistic insights into photoactivation processes in biological systems. A possible alternative is represented by TDDFT which maintains a computational feasibility (even if more expensive than semiempirical methods) but is not limited by the need of parameterization. However, TDDFT is inherently a single-reference method, and as such, it struggles with systems/processes exhibiting a strong multi-reference character, such as conical intersections or diradicals. Moreover, standard hybrid exchange-correlation functionals fail to accurately describe long-range charge-transfer excitations. Range-separated hybrid functionals improve the description but do not fully eliminate the problem in all cases. Finally, TDDFT cannot describe double excitations and this can severely limit the applicability for states with significant double-excitation character, often found in conjugated systems.

3.3 Electron transfer

ET processes play a central role in the photoactivation mechanisms of light-responsive proteins. On the one hand, in photosystems, the sequence begins with excitation energy transfer to the reaction center, where photoactivation occurs via the excitation of the special pair of chlorophyll molecules. This excited state rapidly initiates a cascade of electron transfer steps through a series of cofactors, leading to long-range charge separation which is the key event in the conversion of light energy into chemical energy. On the other hand, photoinduced electron transfer is an alternative mechanism used by photoreceptors to photochemical reactions. In these cases, light absorption triggers an electronic excitation that leads to charge separation within the chromophore or between the chromophore and nearby residues, initiating structural or redox changes that propagate to the signaling domain.

To model the ET processes, quantum chemical calculations are typically carried out on truncated subsystems comprising the donor–acceptor (D–A) pair. In such approaches, environmental (protein and solvent) effects are generally incorporated at classical level by employing a QM/MM framework. Electrostatic or polarizable embedding schemes are employed to capture the influence of the local environment on the electronic structure and interactions of the D–A pair. 7 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83

Surface hopping described in the previous section can be effectively applied to study electron transfer by simulating the coupled dynamics of nuclear and electronic degrees of freedom. In this context, electron transfer is modeled as a transition between donor and acceptor states, with hopping events representing the actual charge transfer. The method enables the analysis of population dynamics, transfer rates, and the influence of nuclear motion and environmental factors, when combined with QM/MM.

In many cases, however, we do not need to simulate the real ET dynamics but we can apply a simplified kinetic model. In this case, the ET rate is typically computed using Marcus model 84 according to:

where V is electronic coupling between Donor and Acceptor, λ is the reorganization energy and the driving force ΔG is the difference in free energy between the fully relaxed initial and final states.

Under the assumption of a harmonic approximation, this process can be represented by two parabolas with the same curvature (see Fig. 5(a)). Each parabola characterizes the dependence of the free energy on nuclear displacements along an appropriate reaction coordinate R, while constraining the electronic state to that corresponding to the minimum of the respective parabola. Consequently, each parabola represents a diabatic state of the system: one corresponding to the initial state, with the electron localized at the Donor, and the other corresponding to the final state, with the electron localized at the Acceptor. Within the diabatic representation, the electronic coupling V is the off-diagonal element of the electronic Hamiltonian.

![Fig. 5:

Harmonic representation of a two-state electron transfer model, R is the collective variable representing the reaction coordinate. (a) Diabatic representation: initial and final diabatic states are described by free energy curves G

i

(R) and G

i

(R), respectively, which intersects at the transition state (TS). (b) Schematic representation of adiabatic free energy surfaces (solid lines) for the two-state model compared to the respective diabatic picture (dashed lines). Adapted and revised from Ref. 85].](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2025-0517/asset/graphic/j_pac-2025-0517_fig_005.jpg)

Harmonic representation of a two-state electron transfer model, R is the collective variable representing the reaction coordinate. (a) Diabatic representation: initial and final diabatic states are described by free energy curves G i (R) and G i (R), respectively, which intersects at the transition state (TS). (b) Schematic representation of adiabatic free energy surfaces (solid lines) for the two-state model compared to the respective diabatic picture (dashed lines). Adapted and revised from Ref. 85].

Since diabatic states are not directly available from standard quantum chemical methods (which give adiabatic states), practical calculations rely on approximate schemes to extract or reconstruct diabatic couplings. A very popular approach for calculating the coupling is the Generalized Mulliken–Hush (GMH) which is based on donor/acceptor system described in terms of two adiabatic states |1⟩ and |2⟩ (see Fig. 5(b)). Within this framework, V is defined as

where ΔE = E

2 − E

1 is the energy difference between the two adiabatic states, μ

11 and μ

22 are the dipole moment in states 1 and 2 (along the direction of the donor–acceptor dipole),

The other fundamental parameter of the Marcus rate, is the reorganization energy λ which quantifies the energy required to reorganize the nuclear configuration of both the donor–acceptor complex and its surrounding environment (protein, solvent). To account for both these two components, the total reorganization energy can be rewritten as:

where λ in is the inner-sphere reorganization energy (nuclear relaxation of the donor–acceptor system) and λ out the Outer-sphere reorganization energy (reorganization of the environment, e.g., solvent and protein matrix).

Within the harmonic approximation depicted in Fig. 5(a), the inner-Sphere reorganization Energy λ in is defined as the difference between G f (R i ) e G i (R i ). In a more general context, the inner-sphere reorganization free energy is calculated through the so-called four-point scheme. 76 Within this framework, the ET donor and acceptor are treated as independent entities; that is, structural reorganization of the donor does not affect the configuration of the acceptor, and vice versa. Consequently, the inner-sphere reorganization energy can be obtained as the sum of the individual distortion energies associated with the donor and the acceptor. In practice, this requires calculating the vertical energy gaps at both the donor and acceptor equilibrium geometries.

The outer-Sphere Reorganization Energy λ out accounts for protein and/or solvent response. Using a simplified model where donor and acceptor are assumed to be embedded in spherical cavities within a continuum dielectric, λ out becomes:

where Δq is the charge transferred, r D , r A are the radii of donor’s and acceptor’s cavities, R DA the distance between them, and ɛ s /ɛ ∞ the static/optical dielectric constant of the environment. To get a more accurate estimate, quantum chemical methods need to be used either in combination of continuum solvation models or MD simulations. If an ensemble of configurations (from classical or QM/MM MD) is available, one can compute the reorganization energy from the variance of the energy gap:

where ΔE(R) is the vertical energy gap at each configuration R and ⟨⋅⟩ denotes an average over the MD trajectory. This captures how fluctuations in the environment modulate the driving force for ET and thus contribute to the reorganization energy.

The Marcus model, although fundamental to understanding electron transfer, has key limitations: it assumes harmonic potentials and classical nuclear motion, making it less accurate for systems with anharmonicity or strong vibronic coupling. It is primarily valid in the nonadiabatic regime and it does not fully capture quantum effects like nuclear tunneling. Models that extend beyond Marcus theory aim to address its limitations by incorporating quantum effects and strong electronic coupling . 78

4 Conclusions

The methodological strategies outlined in the previous section illustrate that quantum chemistry–based multiscale approaches have matured into reliable tools for accurately describing photoactivated processes in proteins. Nonetheless, several important limitations persist, which currently hinder their broader applicability. The primary limitation is due to the fact that modeling excited-state properties and dynamics, unlike their ground-state counterparts, entails significantly greater complexity in the quantum chemical treatment, leading to substantially increased computational demands.

A very effective strategy to overcome this limitation is to exploit Machine Learning (ML). ML models, particularly neural networks and kernel methods, can be trained to reproduce high-level electronic structure data. Once trained, these models can predict energies, gradients, and nonadiabatic couplings orders of magnitude faster than ab initio calculations, enabling the on-the-fly propagation of dynamics on excited-state surfaces. 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 ML models can also be trained to predict site energies and electronic couplings. This approach replaces expensive electronic structure calculations with rapid predictions, enabling efficient generation of exciton Hamiltonians. 90 , 91 , 92

The detailed and comprehensive insights emerging from the application of these methods are beginning to unveil molecular-level mechanisms of photoactivation that had not been previously considered. This progress not only enables a more complete understanding of biological functions at an atomistic scale, but also opens new avenues for application, particularly when integrated with artificial intelligence techniques. Indeed, the full potential of photoactivatable proteins in non-natural contexts remains largely unexplored, constrained by the evolutionary optimization of natural systems for specific mechanisms and operating conditions. By leveraging the enhanced mechanistic understanding provided by quantum-chemistry based approaches, it will become possible to engineer novel systems by guiding the evolution of known proteins through the integration of atomistic simulations with AI approaches.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Senn, H. M.; we QM/MM Methods for Biomolecular Systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1198–1229; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200802019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Brunk, E.; Rothlisberger, U. Mixed Quantum Mechanical/Molecular Mechanical Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Biological Systems in Ground and Electronically Excited States. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6217–6263; https://doi.org/10.1021/cr500628b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Boulanger, E.; Harvey, J. N. QM/MM Methods for Free Energies and Photochemistry. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018, 49, 72–76; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2018.01.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Mennucci, B.; Corni, S. Multiscale Modelling of Photoinduced Processes in Composite Systems. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3, 315–330; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-019-0092-4.Search in Google Scholar

5. Bondanza, M.; Nottoli, M.; Cupellini, L.; Lipparini, F.; Mennucci, B. Polarizable Embedding QM/MM: the Future Gold Standard for Complex (Bio)Systems? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 14433–14448; https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cp02119a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Nottoli, M.; Cupellini, L.; Lipparini, F.; Granucci, G.; Mennucci, B. Multiscale Models for Light-Driven Processes. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2021, 72, 1–25; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physchem-090419-104031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Kubař, T.; Elstner, M.; Cui, Q. Hybrid Quantum Mechanical/Molecular Mechanical Methods for Studying Energy Transduction in Biomolecular Machines. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2023, 52, 525–551; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biophys-111622-091140.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Carrasco-Busturia, D.; Ippoliti, E.; Meloni, S.; Rothlisberger, U.; Olsen, J. M. H. Multiscale Biomolecular Simulations in the Exascale Era. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2024, 86, 102821; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2024.102821.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Avagliano, D.; Conti, I.; El-Tahawy, M. M.; Jaiswal, V. K.; Nenov, A.; Garavelli, M. In Comprehensive Computational Chemistry; Yáñez, M.; Boyd, R. J., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2024, 1st ed.; pp. 158–187.10.1016/B978-0-12-821978-2.00059-3Search in Google Scholar

10. Acharya, A.; Bogdanov, A. M.; Grigorenko, B. L.; Bravaya, K. B.; Nemukhin, A. V.; Lukyanov, K. A.; Krylov, A. I. Photoinduced Chemistry in Fluorescent Proteins: Curse or Blessing? Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 758–795; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00238.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Mroginski, M. A.; Adam, S.; Amoyal, G. S.; Barnoy, A.; Bondar, A.; Borin, V. A.; Church, J. R.; Domratcheva, T.; Ensing, B.; Fanelli, F.; Ferré, N.; Filiba, O.; Pedraza-González, L.; González, R.; González-Espinoza, C. E.; Kar, R. K.; Kemmler, L.; Kim, S. S.; Kongsted, J.; Krylov, A. I.; Lahav, Y.; Lazaratos, M.; NasserEddin, Q.; Navizet, I.; Nemukhin, A.; Olivucci, M.; Olsen, J. M. H.; Pérez de Alba Ortíz, A.; Pieri, E.; Rao, A. G.; Rhee, Y. M.; Ricardi, N.; Sen, S.; Solov’yov, I. A.; De Vico, L.; Wesolowski, T. A.; Wiebeler, C.; Yang, X.; Schapiro, I. Frontiers in Multiscale Modeling of Photoreceptor Proteins. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 243–269; https://doi.org/10.1111/php.13372.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Salvadori, G.; Mazzeo, P.; Accomasso, D.; Cupellini, L.; Mennucci, B. Deciphering Photoreceptors Through Atomistic Modeling from Light Absorption to Conformational Response. J. Mol. Biol. 2024, 436, 168358; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2023.168358.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Croce, R.; van Amerongen, H. Natural Strategies for Photosynthetic Light Harvesting. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 492–501; https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1555.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Mirkovic, T.; Ostroumov, E. E.; Anna, J. M.; van Grondelle, R.; Govindjee; Scholes, G. D. Light Absorption and Energy Transfer in the Antenna Complexes of Photosynthetic Organisms. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 249–293; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Blankenship, R. E. Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

16. Kottke, T.; Xie, A.; Larsen, D. S.; Hoff, W. D. Photoreceptors Take Charge: Emerging Principles for Light Sensing. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2018, 47, 1–23; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biophys-070317-033047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Christie, J. M.; Blackwood, L.; Petersen, J.; Sullivan, S. Plant Flavoprotein Photoreceptors. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 401–413; https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcu196.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Wang, J.; Du, X.; Pan, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, W. Photoactivation of the Cryptochrome/Photolyase Superfamily. Reviews J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2015, 22, 84–102; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2014.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

19. Kennis, J. T. M.; Mathes, T. Molecular Eyes: Proteins that Transform Light into Biological Information. Interface Focus 2013, 3, 20130005–13; https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2013.0005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Runda, M. E.; Schmidt, S. Light-Driven Bioprocesses. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023, 9, 2287–2320; https://doi.org/10.1515/psr-2022-0109.Search in Google Scholar

21. Taylor, A.; Heyes, D. J.; Scrutton, N. S. Catalysis by Nature’s Photoenzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2022, 77, 102491; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2022.102491.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Caffarri, S.; Kouřil, R.; Kereïche, S.; Boekema, E. J.; Croce, R. Functional Architecture of Higher Plant Photosystem II Supercomplexes. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 3052–3063; https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2009.232.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Shevela, D.; Kern, J. F.; Govindjee, G.; Messinger, J. Solar Energy Conversion by Photosystem II: Principles and Structures. Photosynth. Res. 2023, 156, 279–307; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-022-00991-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Iwai, M.; Patel-Tupper, D.; Niyogi, K. K. Structural Diversity in Eukaryotic Photosynthetic Light Harvesting. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2024, 75, 120–152; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-070623-015519.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Son, M.; Hart, S. M.; Schlau-Cohen, G. S. Investigating Carotenoid Photophysics in Photosynthesis with 2D Electronic Spectroscopy. Trends Chem. 2021, 3, 733–746; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trechm.2021.05.008.Search in Google Scholar

26. Collini, E. Carotenoids in Photosynthesis: The Revenge of the “Accessory” Pigments. Chem 2019, 5, 494–495; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2019.02.013.Search in Google Scholar

27. Niyogi, K. K.; Truong, T. B. Evolution of Flexible Non-photochemical Quenching Mechanisms that Regulate Light Harvesting in Oxygenic Photosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013, 16, 307–314; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2013.03.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Pinnola, A.; Bassi, R. Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Plant Photoprotection. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 467–482; https://doi.org/10.1042/bst20170307.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Murchie, E. H.; Ruban, A. V. Dynamic Non-photochemical Quenching in Plants: from Molecular Mechanism to Productivity. Plant J. 2020, 101, 885–896; https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.14601.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Sirohiwal, A.; Pantazis, D. A. Reaction Center Excitation in Photosystem II: From Multiscale Modeling to Functional Principles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 2921–2932; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.3c00392.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Tamura, H.; Saito, K.; Ishikita, H. The Origin of Unidirectional Charge Separation in Photosynthetic Reaction Centers: Nonadiabatic Quantum Dynamics of Exciton and Charge in Pigment–Protein Complexes. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 8131–8140; https://doi.org/10.1039/d1sc01497h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Capone, M.; Sirohiwal, A.; Aschi, M.; Pantazis, D. A.; Daidone, I. Alternative Fast and Slow Primary Charge-Separation Pathways in Photosystem II. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216276; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202216276.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Forde, A.; Maity, S.; Freixas, V. M.; Fernandez-Alberti, S.; Neukirch, A. J.; Kleinekathöfer, U.; Tretiak, S. Stabilization of Charge-Transfer Excited States in Biological Systems: A Computational Focus on the Special Pair in Photosystem II Reaction Centers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 4142–4150; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.4c00362.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Rockwell, N. C.; Su, Y.-S.; Lagarias, J. C. Phytochrome Structure and Signaling Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 837–858; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144208.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Losi, A. Flavin-based Blue-Light Photosensors: A Photobiophysics Update. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007, 83, 1283–1300; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00196.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Möglich, A.; Yang, X.; Ayers, R. A.; Moffat, K. Structure and Function of Plant Photoreceptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 21–47; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112259.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Conrad, K. S.; Manahan, C. C.; Crane, B. R. Photochemistry of Flavoprotein Light Sensors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 801–809; https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1633.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Anders, K.; Essen, L.-O. The Family of Phytochrome-like Photoreceptors: Diverse, Complex and Multi-Colored, but Very Useful. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015, 35, 7–16; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2015.07.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Mouritsen, H. Long-distance Navigation and Magnetoreception in Migratory Animals. Nature 2018, 558, 50–59; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0176-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Polli, D.; Rivalta, I.; Nenov, A.; Weingart, O.; Garavelli, M.; Cerullo, G. Tracking the Primary Photoconversion Events in Rhodopsins by Ultrafast Optical Spectroscopy. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 14, 213–228; https://doi.org/10.1039/c4pp00370e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Renger, T.; Müh, F. Understanding Photosynthetic Light-Harvesting: a Bottom up Theoretical Approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 3348–24; https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cp43439g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Curutchet, C.; Mennucci, B. Quantum Chemical Studies of Light Harvesting. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 294–343; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00700.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Cignoni, E.; Slama, V.; Cupellini, L.; Mennucci, B. The Atomistic Modeling of Light-Harvesting Complexes from the Physical Models to the Computational Protocol. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 156, 120901; https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0086275.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Segatta, F.; Cupellini, L.; Garavelli, M.; Mennucci, B. Quantum Chemical Modeling of the Photoinduced Activity of Multichromophoric Biosystems. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9361–9380; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00135.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Maity, S.; Kleinekathöfer, U. Recent Progress in Atomistic Modeling of Light-Harvesting Complexes: a Mini Review. Photosynth. Res. 2023, 156, 147–162; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-022-00969-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Loco, D.; Lagardère, L.; Cisneros, G. A.; Scalmani, G.; Frisch, M.; Lipparini, F.; Mennucci, B.; Piquemal, J.-P. Towards Large Scale Hybrid QM/MM Dynamics of Complex Systems with Advanced Point Dipole Polarizable Embeddings. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 7200–7211; https://doi.org/10.1039/c9sc01745c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Nottoli, M.; Bondanza, M.; Mazzeo, P.; Cupellini, L.; Curutchet, C.; Loco, D.; Lagardère, L.; Piquemal, J.-P.; Mennucci, B.; Lipparini, F. QM/AMOEBA Description of Properties and Dynamics of Embedded Molecules. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2023, 13; https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1674.Search in Google Scholar

48. Davydov, A. S. Theory of Molecular Excitons; Plenum Press: New York, 1971.10.1007/978-1-4899-5169-4Search in Google Scholar

49. Cupellini, L.; Corbella, M.; Mennucci, B.; Curutchet, C. Electronic Energy Transfer in Biomacromolecules. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2019, 9, e1392; https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1392.Search in Google Scholar

50. You, Z.-Q.; Hsu, C.-P. Theory and Calculation for the Electronic Coupling in Excitation Energy Transfer. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2013, 114, 102–115; https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.24528.Search in Google Scholar

51. Cheng, Y.-C.; Fleming, G. R. Dynamics of Light Harvesting in Photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2009, 60, 241–262; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physchem.040808.090259.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Jang, S. J.; Mennucci, B. Delocalized Excitons in Natural Light-Harvesting Complexes. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 035003; https://doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.90.035003.Search in Google Scholar

53. Valleau, S.; Eisfeld, A.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. On the Alternatives for Bath Correlators and Spectral Densities from Mixed Quantum-Classical Simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 224103–14; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4769079.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Damjanović, A.; Kosztin, I.; Kleinekathöfer, U.; Schulten, K. Excitons in a Photosynthetic Light-Harvesting System: A Combined Molecular Dynamics, Quantum Chemistry, and Polaron Model Study. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 65, 031919; https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.65.031919.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Lee, M. K.; Huo, P.; Coker, D. F. Semiclassical Path Integral Dynamics: Photosynthetic Energy Transfer with Realistic Environment Interactions. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2016, 67, 639–668; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physchem-040215-112252.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Novoderezhkin, V.; Marin, A.; Grondelle, R. V. Intra-and Inter-monomeric Transfers in the Light Harvesting LHCII Complex: the Redfield–Förster Picture. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 17093–11.10.1039/c1cp21079cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Yang, M.; Fleming, G. R. Influence of Phonons on Exciton Transfer Dynamics: Comparison of the Redfield, Förster, and Modified Redfield Equations. Chem. Phys. 2002, 275, 355–372; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-0104-01-00540-7.Search in Google Scholar

58. Scholes, G. D.; Jordanides, X. J.; Fleming, G. R. Adapting the Förster Theory of Energy Transfer for Modeling Dynamics in Aggregated Molecular Assemblies. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 1640–1651; https://doi.org/10.1021/jp003571m.Search in Google Scholar

59. Levine, B. G.; Martínez, T. J. Isomerization Through Conical Intersections. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2007, 58, 613–634; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physchem.57.032905.104612.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Polli, D.; Altoè, P.; Weingart, O.; Spillane, K. M.; Manzoni, C.; Brida, D.; Tomasello, G.; Orlandi, G.; Kukura, P.; Mathies, R. A.; Garavelli, M.; Cerullo, G. Conical Intersection Dynamics of the Primary Photoisomerization Event in Vision. Nature 2010, 467, 440–443; https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09346.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Gozem, S.; Luk, H. L.; Schapiro, I.; Olivucci, M. Theory and Simulation of the Ultrafast Double-Bond Isomerization of Biological Chromophores. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13502–13565; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00177.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Sen, S.; Kar, R. K.; Borin, V. A.; Schapiro, I. Insight into the Isomerization Mechanism of Retinal Proteins from Hybrid Quantum Mechanics/molecular Mechanics Simulations. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1562; https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1562.Search in Google Scholar

63. Frutos, L. M.; Andruniów, T.; Santoro, F.; Ferré, N.; Olivucci, M. Tracking the Excited-State Time Evolution of the Visual Pigment with Multiconfigurational Quantum Chemistry, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 7764–7769; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701732104.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Persico, M.; Granucci, G. An Overview of Nonadiabatic Dynamics Simulations Methods, with Focus on the Direct Approach versus the Fitting of Potential Energy Surfaces. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2014, 133, 1526–28; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-014-1526-1.Search in Google Scholar

65. Crespo-Otero, R.; Barbatti, M. Recent Advances and Perspectives on Nonadiabatic Mixed Quantum–Classical Dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 7026–7068; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00577.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Nelson, T. R.; White, A. J.; Bjorgaard, J. A.; Sifain, A. E.; Zhang, Y.; Nebgen, B.; Fernandez-Alberti, S.; Mozyrsky, D.; Roitberg, A. E.; Tretiak, S. Non-adiabatic Excited-State Molecular Dynamics: Theory and Applications for Modeling Photophysics in Extended Molecular Materials. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 2215–2287; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00447.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Mai, S.; González, L. Molecular Photochemistry: Recent Developments in Theory. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16832–16846; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201916381.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

68. Tully, J. C. Molecular Dynamics with Electronic Transitions. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 93, 1061–1071; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.459170.Search in Google Scholar

69. Yang, X.; Manathunga, M.; Gozem, S.; Léonard, J.; Andruniów, T.; Olivucci, M. Quantum–Classical Simulations of Rhodopsin Reveal Excited-State Population Splitting and its Effects on Quantum Efficiency. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 441–449; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-022-00892-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

70. Chung, W. C.; Nanbu, S.; Ishida, T. QM/MM Trajectory Surface Hopping Approach to Photoisomerization of Rhodopsin and Isorhodopsin: The Origin of Faster and More Efficient Isomerization for Rhodopsin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 8009–8023; https://doi.org/10.1021/jp212378u.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

71. Salvadori, G.; Macaluso, V.; Pellicci, G.; Cupellini, L.; Granucci, G.; Mennucci, B. Protein Control of Photochemistry and Transient Intermediates in Phytochromes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6838; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34640-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

72. Morozov, D.; Modi, V.; Mironov, V.; Groenhof, G. The Photocycle of Bacteriophytochrome Is Initiated by Counterclockwise Chromophore Isomerization. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 4538–4542; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c00899.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73. Curchod, B. F. E.; Martínez, T. J. Ab Initio Nonadiabatic Quantum Molecular Dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3305–3336; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00423.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

74. Thiel, W. Semiempirical Quantum-Chemical Methods. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2013, 4, 145–157; https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1161.Search in Google Scholar

75. Fabiano, E.; Keal, T. W.; Thiel, W. Implementation of Surface Hopping Molecular Dynamics Using Semiempirical Methods. Chem. Phys. 2008, 349, 334–347; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.01.044.Search in Google Scholar

76. Rosso, K. M.; Dupuis, M. Electron Transfer in Environmental Systems: A Frontier for Theoretical Chemistry. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2006, 116, 124–136; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-005-0016-x.Search in Google Scholar

77. Beratan, D. N.; Liu, C.; Migliore, A.; Polizzi, N. F.; Skourtis, S. S.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y. Charge Transfer in Dynamical Biosystems, or the Treachery of (Static) Images. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 474–481; https://doi.org/10.1021/ar500271d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

78. Blumberger, J. Recent Advances in the Theory and Molecular Simulation of Biological Electron Transfer Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11191–11238; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00298.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

79. Narth, C.; Gillet, N.; Cailliez, F.; Lévy, B.; de la Lande, A. Electron Transfer, Decoherence, and Protein Dynamics: Insights from Atomistic Simulations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1090–1097; https://doi.org/10.1021/ar5002796.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

80. Escudero, D. Revising Intramolecular Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) from First-Principles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1816–1824; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00299.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Saen-Oon, S.; Lucas, M. F.; Guallar, V. Electron Transfer in Proteins: Theory, Applications and Future Perspectives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 15271–15285; https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cp50484k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Hammes-Schiffer, S. Exploring Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer at Multiple Scales. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 291–300; https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-023-00422-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

83. Zanetti‐Polzi, L.; Pantazis, D. A.; Daidone, I. Intermolecular Photoinduced Electron Transfer in Biosystems: Impact of Conformational Transitions and Multiple Channels on Kinetics. ChemPhotoChem 2024, 8, e202300307; https://doi.org/10.1002/cptc.202300307.Search in Google Scholar

84. Marcus, R. A. Chemical and Electrochemical Electron-Transfer Theory. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1964, 15, 155–196; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pc.15.100164.001103.Search in Google Scholar

85. Oberhofer, H.; Reuter, K.; Blumberger, J. Charge Transport in Molecular Materials: An Assessment of Computational Methods. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10319–10357; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00086.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

86. Dral, P. O.; Barbatti, M.; Thiel, W. Nonadiabatic Excited-State Dynamics with Machine Learning. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 5660–5663; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b02469.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

87. Dral, P. O. Quantum Chemistry in the Age of Machine Learning. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2336–2347; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b03664.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

88. Westermayr, J.; Marquetand, P. Machine Learning for Electronically Excited States of Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 9873–9926; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00749.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

89. Richings, G. W.; Habershon, S. Predicting Molecular Photochemistry Using Machine-Learning-Enhanced Quantum Dynamics Simulations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 209–220; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00665.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

90. Häse, F.; Valleau, S.; Pyzer-Knapp, E.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Machine Learning Exciton Dynamics. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 5139–5147; https://doi.org/10.1039/c5sc04786b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

91. Sokolov, M.; Hoffmann, D. S.; Dohmen, P. M.; Krämer, M.; Höfener, S.; Kleinekathöfer, U.; Elstner, M. Non-Adiabatic Molecular Dynamics Simulations Provide New Insights into the Exciton Transfer in the Fenna–Matthews–Olson Complex. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 19469–19496; https://doi.org/10.1039/d4cp02116a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

92. Cignoni, E.; Cupellini, L.; Mennucci, B. Machine Learning Exciton Hamiltonians in Light-Harvesting Complexes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 965–977; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.2c01044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 IUPAC & De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Minimum energy path methods and reactivity for enzyme reaction mechanisms: a perspective

- The quantum revolution in enzymatic chemistry: combining quantum and classical mechanics to understand biochemical processes

- A quantum chemical perspective of photoactivated biological functions

- Does chemistry need more physics?

- Rotational dynamics of ATP synthase: mechanical constraints and energy dissipative channels

- Transforming dreams into reality: a fairy-tale wedding of chemistry with quantum mechanics

- The quantum chemistry revolution and the instrumental revolution as evidenced by the Nobel Prizes in chemistry

- Influence of symmetry on the second-order NLO properties: insights from the few state approximations

- The dichotomy between chemical concepts and numbers after almost 100 years of quantum chemistry: conceptual density functional theory as a case study

- How ‘de facto variational’ are fully iterative, approximate iterative, and quasiperturbative coupled cluster methods near equilibrium geometries?

- Electronic structure of methyl radical photodissociation

- Bridging experiment and theory: a computational exploration of UMG-SP3 dynamics

- Research Articles

- O–Li⋯O and C–Li⋯C lithium bonds in small closed shell and open shell systems as analogues of hydrogen bonds

- Metal–ligand bonding and noncovalent interactions of mutated myoglobin proteins: a quantum mechanical study

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Minimum energy path methods and reactivity for enzyme reaction mechanisms: a perspective

- The quantum revolution in enzymatic chemistry: combining quantum and classical mechanics to understand biochemical processes

- A quantum chemical perspective of photoactivated biological functions

- Does chemistry need more physics?

- Rotational dynamics of ATP synthase: mechanical constraints and energy dissipative channels

- Transforming dreams into reality: a fairy-tale wedding of chemistry with quantum mechanics

- The quantum chemistry revolution and the instrumental revolution as evidenced by the Nobel Prizes in chemistry

- Influence of symmetry on the second-order NLO properties: insights from the few state approximations

- The dichotomy between chemical concepts and numbers after almost 100 years of quantum chemistry: conceptual density functional theory as a case study

- How ‘de facto variational’ are fully iterative, approximate iterative, and quasiperturbative coupled cluster methods near equilibrium geometries?

- Electronic structure of methyl radical photodissociation

- Bridging experiment and theory: a computational exploration of UMG-SP3 dynamics

- Research Articles

- O–Li⋯O and C–Li⋯C lithium bonds in small closed shell and open shell systems as analogues of hydrogen bonds

- Metal–ligand bonding and noncovalent interactions of mutated myoglobin proteins: a quantum mechanical study