Abstract

The Spanish discourse marker bueno has multiple functions ranging from the expression of (dis)agreement to topic management. The present paper sets out to explore what happens when bueno starts to be used in written monological contexts. We examine the use of bueno in spoken sociolinguistic interviews and written internet texts in Mexican and Peninsular Spanish. We propose a unified account of the different functions of bueno based on preference structure and mitigation, tracing a grammaticalization path from adjectival to dialogical and, subsequently, monological uses of bueno. We use regression analysis to examine the hypotheses that (a) written medium serves as a catalyst for monologization, and (b) the two dialects studied represent two different stages of grammaticalization of bueno. While the first hypothesis is confirmed, evidence supporting the second hypothesis is less conclusive, suggesting that written uses are more similar between the two dialects than the spoken ones.

1 Introduction

In Spanish, the adjective bueno ‘good’ has developed interactional functions such as mitigation. For instance, in example (1), bueno mitigates a non-preferred response: I is not able or willing to give a polar response about their future travel plans as projected by the interlocutor’s question, but instead starts an explanation about past travels and travel habits. The turn-initial bueno, particularly with the connective pues ‘so’, indicates that the speaker will deviate from the preference structure and modify or even change the conversational topic.

| Sociolinguistic interview GRAN_H33_015, PRESEEA, Granada, Spain, 20061 | |

| E: | ¿tiene en mente realizar algún viaje? |

| ‘do you currently have any travel plans?’ | |

| I: | bueno (.) pues por mi profesió:n (0.5) tengo que viajar dentro de España y al extranjero (.) ayer llegué de Madrid y: el día nueve si no hay nada pendiente antes pues salgo para:: para Nivega |

| ‘BUENO because of my job I have to travel in Spain and abroad; yesterday I got in from Madrid and on the ninth, if nothing else happens, I will leave for Nivega.’ | |

- 1

The PRESEEA corpus will be introduced in Section 3 below.

Previous research on bueno has focused on spoken informal interaction and identified a number of interactive discourse functions such as (dis)agreement and topic management (Bauhr 1994; Borreguero Zuloaga 2017; García Vizcaíno and Martínez-Cabeza 2005; Landone 2009: 264–267; López Serena and Borreguero Zuloaga 2010; Maldonado and Palacios 2015; Martín Zorraquino and Portolés 1999; Martínez Hernández 2016; Pons Bordería 2003; Serrano 1999). By contrast, the use of bueno in writing has received little attention. Recent research has shown that due to the communicative restrictions in writing (e.g., lack of immediacy and shared context), discourse markers may acquire functions in writing that differ considerably from their use in speech. Sansò (2022) proposes the term “monologization” to account for the process where discourse markers become dissociated from their original dialogical use and develop new functions in monological contexts, including written texts.

In this study, we compare the use of bueno in spoken and written Peninsular and Mexican Spanish, focusing on the influence of the medium on the discourse functions of this discourse marker. Based on a qualitative and quantitative analysis of 2,829 cases of bueno taken from a corpus of sociolinguistic interviews and another corpus comprising texts from online blogs and forums (see Section 4 for a description of the data), we propose that bueno has been subject to a monologization process in both varieties of Spanish. We document innovative uses of bueno in non-initial position in written texts serving perspective management functions. In particular, bueno is frequently used to introduce and discuss an objection to an assertion made by the same or the previous writer, thereby introducing alternative perspectives in the discourse. Since turn management and politeness are more useful in spoken discourse and in dialogue than in writing and monological contexts, we propose that the use of bueno in writing is disconnected from these dialogical functions and, rather, is used for topic and perspective management (see Section 5).

This article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we review previous literature on the use of bueno in spoken Spanish. In Section 3, we describe the notion of monologization and its relevance for the research topic. The data used for the study are introduced in Section 4. Results from the analysis of bueno in spoken and written Peninsular and Mexican Spanish are described in Section 5. Based on this analysis, we propose a historical pathway for the emergence of the different discourse functions of bueno in Section 6. The paper concludes with a summary and discussion of results, in Section 7.

2 Discourse functions of bueno in spoken Spanish

There is a considerable body of research on discourse markers in Spanish (see, e.g., Briz et al. 2008; Llopis Cardona 2016; Llopis Cardona and Pons Bordería 2020; Martín Zorraquino and Portolés 1999, and references therein). As pointed out by Martín Zorraquino and Portolés (1999), the discourse marker bueno is extremely versatile and can express several pragmatic functions. These authors include bueno in the category of discourse markers, as opposed to other markers occurring also or mainly in written and/or monological contexts, and distinguish three different functions: (a) marking deontic modality (e.g., expression of acceptance or consent by the speaker), (b) expressing disagreement with the interlocutor while protecting the positive face of the speaker by mitigating the disagreement, and (c) structuring the conversation, e.g., by signaling reception of the message or beginning, ending or changing the topic. A similar tripartite division is suggested by Pons Bordería (2003), who distinguishes between (a) agreement with the interlocutor, including concessive and mitigating uses (especially with sí ‘yes’ and no ‘no’), (b) disagreement with the interlocutor, and (c) formulative uses, including reformulation of previously uttered discourse. In their online dictionary of discourse particles (Diccionario de partículas discursivas del español), Briz et al. (2008) also consider three different meanings for bueno: (a) indicating agreement with what has been said previously, possibly nuancing the previous content, (b) indicating disagreement, together with an “emphatic intonation”, and (c) presenting what is being said as a continuation of previous discourse.

Some of the functions in (a) to (c) are illustrated below in Examples (2–4). In (2), bueno appears to express agreement to E’s previous utterance. In (3), bueno is used to mitigate a disagreement; I forcefully contradicts E’s implication that Alcalá is no longer an interesting or nice city. Finally, in (4), bueno is used to change the conversational topic.

| Agreement | |

| Sociolinguistic interview MEXI_H22_054, PRESEEA, Mexicali, Mexico, 2007 | |

| E: | la podrías obviar en folclor (.) ¿eh? (.) porque: los ejercicios son diferentes (.) ¿no? |

| ‘you could disregard this in folklore, eh? because the exercises differ, no?’ | |

| P: | bueno sí |

| ‘BUENO yes’ | |

| E: | ajá |

| ‘okay’ | |

| Mitigation | |

| Sociolinguistic interview ALCA_H31_050, PRESEEA, Alcalá, Spain | |

| E: | y: claro naturalmente vinimos en un momento en el que Alcalá era una [cosa] |

| ‘and of course we came in a moment in which Alcalá was still a thing’ | |

| I: | [bueno:] |

| ‘okay’ | |

| E: | y: a lo largo de todos estos años [pues] |

| ‘and over all these years, well’ | |

| I: | [ bueno :] bueno : ¡no ha cambiado nada Alcalá madre mía del Pilar! |

| ‘BUENO BUENO (but) Alcalá hasn’t changed at all, My Lady Pilar!’ | |

| Topic management | |

| Sociolinguistic interview GUAD_H31_066, PRESEEA, Guadalajara, Mexico, 2017 | |

| I: | pues no no podía uno por la situación eh económica que (.) que vivía uno en ese tiempo |

| ‘because you could not do this [study] due to the economic situation at that time’ | |

| E: | mj (0.5) y: (0.5) respecto (.) bueno (.) regresando a (.) a lo que me comentaba |

| ‘mmh and with regard BUENO going back to what you told me about your kids’ | |

While acknowledging the multifunctionality of bueno, most authors consider the functions as clearly distinct from one another, not contemplating the possibility that bueno may serve several functions simultaneously. For instance, in (4), it may be argued that bueno is not only used to mark a change of topic but also to mitigate the face-threatening act of topic change.

López Serena and Borreguero Zuloaga (2010), who discuss the differences between discourse markers in oral versus written language, present a classification of discourse markers in general (cf. also the more recent study by Fernández Madrazo and López Serena [2022]). They consider that all discourse markers fall into three categories, representing the following macro functions: (a) interactional, (b) metadiscursive, and (c) cognitive. Bueno is given as an example in all three macrofunctions: as an interactional marker, it is related with the management of conversational turns; as a metadiscursive marker, it is used for topic management; and as a cognitive marker, it is used for mitigation. While mitigation is not considered a separate category by Martín Zorraquino and Portolés (1999), Pons Bordería (2003), or Briz et al. (2008), these authors do generally recognize it as one of the functions of bueno when it is used as a marker of disagreement. However, mitigation is not limited to the expression of disagreement; consider, for example, (5) where bueno prefaces a turn expressing agreement rather than disagreement, while saving the speaker’s positive face, otherwise threatened by the bald acceptance of the implication that she is a good cook.

| Agreement with mitigation | |

| Sociolinguistic interview MADR_M21_024, PRESEEA, Madrid, Spain, 2002 | |

| E: | ¿eres buena cocinera? |

| ‘Are you a good cook?’ | |

| I: | bueno , no mm me disgusta (0.5) me gusta (laughs) |

| ‘BUENO I don’t dislike it, I like it’ | |

While López Serena and Borreguero Zuloaga (2010) restrict the interactional macrofunction to spoken language, they consider the two others to be common in spoken and written language. However, all the examples of bueno they provide are from spoken data. In general, previous research has not considered the use of bueno in written data. As we will show, bueno does occur in colloquial, informal texts, including but not restricted to interactional writing such as forums and chats. We propose that in written contexts, bueno has obtained new discourse functions due to a process of “monologization” (Sansò 2022), as described in Section 3.

3 Monologization processes

The development of new uses for discourse markers in monologues from previous dialogical uses has recently been labeled “monologization” (Sansò 2022), consisting of a process in which an originally dialogic sequence (i.e., stretching over two turns) starts to be used within a single turn. Thus,

Monologization consists in the progressive emancipation of a given element from a dialogic structure to become an autonomous, monological marker/construction, which no longer requires the original dialogic structure in which it was embedded in order to be felicitously uttered. (Sansò 2022: 201).

Sansò exemplifies this development with the Italian discourse markers e niente ‘and nothing’ that emerges as a turn-initial mitigation device and subsequently starts to be used as a polite turn-taking marker. In a third stage, e niente is used as a topic progression marker in both turn-initial and turn-medial positions. While the first two functions are dialogical, the third is monological, i.e., not necessarily related to interaction between interlocutors. Finally, e niente has also acquired uses as an opening formula initiating a totally new discourse topic in social media texts where it gives the impression of intimacy and informality (Sansò 2022).

In the case of bueno, we can also observe a distinction between dialogical and monological uses. Affirmation, negation, mitigation of a non-preferred action, and turn-taking are dialogical uses, given that they occur in discourse patterns stretching over two or more turns. Topic management functions, such as topic change or adopting a new perspective towards a previous topic, can occur in both dialogical and monological contexts. Crucially, while the dialogical functions are typical of spoken language and communicative contexts with several speakers, monological functions can also occur in written texts where there is no interlocutor present. Dialogical uses, on the other hand, should be more frequent – or even occur exclusively – in our oral data.

In addition to the division between the medium of communication (oral vs. written), another relevant dimension is the continuum between communicative immediacy and communicative distance (Koch and Oesterreicher 1985). While an intimate conversation between family members and a premeditated lecture or a sermon both occur in spoken medium, the former represents communicative immediacy while the latter represents communicative distance. Traditionally, most texts in the written medium have been characterized by communicative distance rather than proximity, but the rise of informal writing in “new” electronic media such as text messages, chats, discussion boards, and blogs has created text types characterized by communicative immediacy rather than distance, in particular in the case of interactive textual genres like chats or forums. However, the written uses of bueno are not limited to dialogical texts, but it is also found in contexts where it does not function as a reaction to a previous turn or a turn-taking device. Such uses are illustrated in Examples (6) and (7), discussed below.

Since bueno is primordially a dialogical and interactional discourse marker, it is important to note that its monologization process is facilitated through fictive interaction (Pascual 2006, 2010, 2014; Pascual and Oatley 2017). Fictive interaction is manifested in “non-genuine citations” (Pascual 2010: 64), i.e., the use of direct reported speech in monological discourse without presenting it as something said by a specific speaker. Fictive interaction thus often represents what has been called reported thought (e.g., Casartelli et al. 2023). One of the examples discussed in Pascual (2010) showcases the use of bueno in a stretch of reported thought in fictive interaction, as a part of a monological turn.

| Lo que realmente sentí fue una pesadilla, que [había] muchos más heridos de los que yo podía atender. Y no terminaba de entender por qué no había más compañeros allí, allí cerca de mí, no, no terminaba de entenderlo. Entonces al principio fue un poco de descoloque mental, de decir, bueno, ¿qué está ocurriendo? (TV Program Netwerk, canal NL1, 9/3/2005) |

| ‘What I really felt was a nightmare, that [there were] many more wounded than I could care for. And I didn’t quite understand why there weren’t more colleagues there, there close to me, no, I didn’t quite understand it. So at first it was a bit of a mental breakdown, of saying, BUENO, what is happening?’ |

Although example (6) is from an oral interview, as we shall see in examples from our written data, not only is bueno used to introduce reported speech in monological contexts (see Rosemeyer and Posio [2023] for the quotative uses of this marker in spoken Spanish), but bueno itself may be interpreted as signaling fictive interaction. Thus, consider example (7) from a written text:

| Te voy a poner un ejemplo: El profesor dice que deben formar grupos de 4 estudiantes para realizar una tarea. Pepito se hace con Juanita, con Perlita y con Pablito. Juanita, se esmera en acercar a sus compañeros para poder debatir el trabajo y entregarlo con alta calidad en la resolución del problema; por su lado, Pablito y Pepito se reúnen y aprovechan el momento para hablar de sus múltiples relaciones amorosas, de su serie anime favorita y del partido del día anterior que estuvo buenísimo. ¿Perlita? Bueno , ella también es participe por momentos de la conversación y al tiempo ayuda a escribir las ideas de Juanita en la hoja de papel. |

| ‘I am going to give you an example: The teacher says that they must form groups of 4 students to carry out a task. Pepito takes over Juanita, Perlita and Pablito. Juanita strives to bring her colleagues closer to be able to discuss the work and deliver it with high quality in solving the problem; on her side, Pablito and Pepito meet and take advantage of the moment to talk about their multiple love relationships, their favorite anime series and the game the day before that was terrific. Perlita? BUENO, she too participates at times in the conversation and at the same time helps to write Juanita’s ideas on the piece of paper.’ |

In example (7), rather than introducing reported speech or thought, bueno signals that the following sentence is a response to the fictive question (¿Perlita? ‘[What about] Perlita?’) posed by the writer. Here, the use of bueno seems to serve not only topic management purposes but also gives the written monological text an interactional flavor, as if the following sentence was answering an actual question produced by the reader. Thus, the use of bueno in writing is not restricted to dialogical or informal text types, but also occurs as a stylistic device in texts aiming to reproduce dialogicity or conversationality. Fictive interaction, as illustrated in (7), arguably functions as a bridging context (Heine 2002) in the monologization process. It is a necessary point of transition between fully dialogical and fully monological uses. As the result of the monologization process, bueno can be used in contexts where neither genuine nor fictive interaction is needed to motivate the use of the discourse marker.

4 Data

We extracted n = 4,000 randomized occurrences of bueno from two corpora. For spoken Spanish, we used the Mexican and Peninsular Spanish data from the PRESEEA, a dialectal corpus of semi-structured sociolinguistic interviews (Preseea 2014). PRESEEAMexico includes 70 interviews of about 919,000 words dated between 2001 and 2018, recorded in Guadalajara, Mexicali, Mexico City, and Monterrey. PRESEEASpain includes 88 interviews of about 916,000 words dated between 1988 and 2011, recorded in Alcalá de Henares, Granada, Madrid, Málaga, and Valencia. For written Spanish, we used Mexican and Peninsular Spanish data from the Corpus del Español Web/Dialects (henceforth CdE, Davies 2016). The CdEMexico contains about 246 million words, whereas the CdESpain contains about 426.6 million words. For each of the sub-corpora (PRESEEAMexico, PRESEEASpain, CdEMexico, CdESpain), n = 1,000 occurrences of bueno were extracted. These data were then coded manually according to whether bueno was used as a discourse marker or an adjective,[2] leaving us with a final dataset of n = 2,829 discourse marker uses. Table 1 presents the results of these coding procedures.

Usage frequencies of bueno as a discourse marker and as an adjective in the PRESEEA and CdE.

| Data type | Subcorpus | Bueno as discourse marker | Bueno as adjective | % Bueno as discourse marker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spoken sociolinguistic interviews | PRESEEAMexico | 860 | 140 | 86.0 |

| PRESEEASpain | 941 | 59 | 94.1 | |

| Written blogs and forums | CdEMexico | 501 | 499 | 50.1 |

| CdESpain | 527 | 473 | 52.7 |

Table 1 demonstrates that discourse marker uses are overwhelmingly more frequent than adjectival uses in spoken data, while in written data discourse marker and adjectival uses are equally frequent. This finding confirms that bueno is primarily used in spoken interactions (cf. Martín Zorraquino and Portolés 1999). Note also that some dialectal variation seems to be at play in spoken data, where discourse marker uses are more frequent in Peninsular Spanish, suggesting a more advanced grammaticalization of the discourse marker in that variety (see Rosemeyer and Posio 2023).

In our data, PRESEEA represents oral interactions characterized by a relatively high communicative distance in the sense of Koch and Oesterreicher (1985): the sociolinguistic interview format consists of a semi-structured series of questions by the interviewer that are answered by the informant, and both speakers have their specific, asymmetric roles in the communication. The “written” corpus, on the other hand, represents a relatively low communicative distance for written media, given that the texts are mostly written for blogs and other personal web pages and reveal a low grade of premeditation (reflected, e.g., in non-standard orthography and lack of punctuation). There are also elements of dialogicity in the written data. Many uses of bueno occur in commentaries to blogs and forums and consequently react directly to the preceding post.

To compare usage frequencies of bueno according to both medium and communicative distance, we coded all turn- or sentence-initial tokens of our Peninsular data. In addition, we extracted all turn- or sentence-initial uses of bueno from two complementary corpora of Peninsular Spanish, which represent more prototypical spoken and written texts, respectively. In initial position, bueno is almost always used as a discourse marker. For spoken texts, we used the family/informal section of the C-ORAL ROM (Cresti and Moneglia 2005), which represents informal spoken Spanish (only conversations and dialogues). For written texts, we used the non-spoken sections of the CORPES (Real Academia Española 2023), representing formal written Spanish. Table 2 presents the usage frequencies of sentence- or turn-initial bueno in these corpora.

Usage frequencies of sentence- (CORPES, CdE) or turn-initial bueno (PRESEEA, C-ORAL) in four Spanish corpora.

| Corpus | CORPES (formal written texts) | CdE (written blogs and forums) | PRESEEA (sociolinguistic interviews) | C-ORAL (informal conversations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n initial bueno | 10,858 | 187,086 | 441 | 97 |

| n initial bueno per million words | 92.43 | 438.6 | 485.9 | 701.1 |

Inspection of the normalized usage frequencies of bueno in Table 2 reveals great differences between the four corpora, which can be explained in terms of the communicative distance. The use of bueno as a discourse marker is least frequent in formal written texts (CORPES) and most frequent in spoken informal texts (C-ORAL ROM). The data selected for the present study (CdE and PRESEEA) occupy a mid-position with respect to the usage frequency of bueno, suggesting relatively small differences between written informal and spoken formal texts. The similarity between the CdE and the PRESEEA in terms of communicative distance makes these data a perfect test case for an analysis of the relevance of the linguistic medium (spoken vs. written) on the use of the discourse marker bueno.

5 Monologization of bueno

In this section of the paper, we first present the different discourse functions of bueno in written and spoken Spanish in order to be able to posit a historical monologization path for bueno.

Our results suggest that the most important predictors of the type of function expressed by bueno are (a) the position of bueno within the turn and (b) the difference between dialogical and monological contexts. These two predictors are not independent from each other. We define dialogical contexts as contexts in which the utterance introduced with bueno stands in relation to a previous utterance by a different speaker, whereas monological contexts are contexts in which the utterance introduced with bueno stands in relation to a previous utterance by the same speaker. This can be schematically represented as in (8), where u stands for utterance, A for a turn by speaker A, and B for a turn by speaker B.

| a. | Dialogical bueno: | A[u1] |

| B[bueno (u2)] | ||

| b. | Monological bueno: | A[u1 bueno u2] |

A third important parameter, also represented in (8), concerns the question whether bueno projects a following utterance. Projection is defined as “the fact that an individual action or part of it foreshadows another” (Auer 2005). This is true for all examples of bueno discussed in this paper until now except (2). For instance, in example (4), repeated below as (9), the use of bueno projects a change of the conversational topic. Indeed, theories of grammaticalization posit that it is this increase of the (syntactic or semantic) scope that defines discourse markers. Thus, discourse markers “have scope over (pairs of) text segments” (Detges and Waltereit 2016: 639, italics in the original).

| Sociolinguistic interview _GUAD_H31_066, PRESEEA, Guadalajara, Mexico, 2017 | |

| E: | mj (0.5) y: (0.5) respecto (.) bueno (.) regresando a (.) a lo que me comentaba de sus hijos |

| ‘mmh and with regard BUENO going back to what you told me about your kids’ | |

By contrast, in (10) where bueno expresses agreement, it does not project a following utterance and could easily be used without any additional following linguistic material. Even when bueno signals agreement, it nevertheless differs from the canonical agreement marker sí ‘yes’ in that it mitigates the agreement and presents it as less direct. In example (10), the use of bueno in I’s turn softens the response and makes it more polite than the use of just sí. The combination sí claro ‘yes of course’ in both A1’s and I’s responses arguably serves the same function.

| Sociolinguistic interview MADR_H32_043, PRESEEA, Madrid, Spain, 2002 | |

| E: | ¿preparáis algo o: algu:na comida especial o alguna:? |

| ‘Do you prepare something or some special food or some?’ | |

| A1: | sí claro |

| ‘Yes, of course’ | |

| I: | bueno sí (.) sí claro |

| ‘BUENO yes, yes of course’ | |

It is our contention that the most important discourse functions of bueno can be described in terms of the combination of these three features. Table 3 summarizes the resulting typology of discourse functions employed in this paper. As our description of these functions will show, they can be interpreted in terms of subsequent semantic reanalyses of bueno that successively lead from interactional to topic and perspective management meanings.

Summary of the typology of discourse functions developed in this paper.

| Function | Position in turn/sentence | Dialogicity | Projects utterance? | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Initial | Dialogical | No | (10) |

| Agreement with modification of topic | Initial | Dialogical | Yes | (11), (12) |

| Disagreement with modification of topic | Initial | Dialogical | Yes | (13) |

| Modification of topic (without agreement or disagreement) | Initial | Dialogical | Yes | (14) |

| Topic management | Medial | Monological | Yes | |

|

(15) | |||

|

(16) | |||

| Perspective management | Medial | Monological | Yes | |

|

(17), (18) | |||

|

(19) |

We have already given an example for the discourse function of agreement in spoken Spanish in (10) above, where the agreeing function of bueno is reinforced by the following affirmative polar particle sí ‘yes’. Agreeing bueno is always used turn-initially in dialogical contexts and does not project an utterance. Crucially for the interpretation of the historical process yielding the discourse functions of bueno, the agreement use of bueno can be easily explained in terms of the semantics of adjectival bueno. In an initial stage of the grammaticalization[3] process from the adjective meaning ‘good’ towards a discourse particle, despite the lack of direct historical evidence, we can hypothesize that bueno was used to signal agreement by characterizing the interlocutor’s previous turn as ‘good’. In contemporary Spanish, the adjective bueno is no longer used in such a manner, having been replaced by the adverb bien ‘well’. Using bueno for agreement is not frequent in our spoken data, and – crucially to our monologization hypothesis – no agreement uses were documented in our written corpus data.

Even in the basic agreement function illustrated in (10), however, bueno differs from the affirmative particle sí ‘yes’ in that it not only signals agreement but also implies that the response differs slightly from what the interlocutor could have expected (on bueno introducing unexpected or dispreferred responses, see García Vizcaíno and Martínez-Cabeza 2005: 58; Landone 2009: 264; Pons Bordería 2003: 229–234; Raymond 2018). This observation can be formalized using the concept of preference, developed in Conversation Analysis. In a sequential structure organized as an adjacent pair, certain second pair part actions are always preferred and thus require less conversational work (Schegloff 1972, 2007; Schegloff and Sacks 1973): for instance, in evaluation sequences, when speaker A utters a positive evaluation (e.g., Great weather today!), an identically positive evaluation by speaker B (such as It is, indeed) is preferred as the second pair part (Stukenbrock 2013: 234).

In sociolinguistic interviews (PRESEEA), initial bueno is often found in answers where the informant answers a slightly different question than the one made by the interviewer, or the answer is somehow unexpected. In other words, initial bueno is used in dispreferred second pair parts. For instance, in (11) the informant does provide an answer to the question ‘what is the typical dish in Guadalajara?’, but the answer clearly exceeds the limits of a preferred response projected by the question, as the informant provides a wide list of dishes and a personal anecdote about their relatives visiting Guadalajara.

| Sociolinguistic interview PRESEEA_GUAD_M33_013, Guadalajara, Mexico, 2016 | |

| E: | ¿y cuál es la comida típica de Guadalajara? |

| ‘and what is the typical dish from Guadalajara?’ | |

| I: | bueno la comida típica de Guadalajara es el pozole los tacos dorados las tostadas // am hay personas que piensan que la birria |

| ‘BUENO the typical dish from Guadalajara is the pozole, the tacos dorados, the tostadas… um… some people think the birria’ | |

| [several lines omitted, including a description of relatives’ visit to Guadalajara] | |

| pero pues es que ya/te digo que Guadalajara es una ciudad cosmopolita y ya por ejemplo/ya los tacos de de este al vapor de esos de cabeza y que // qué sé yo hay un montón de cosas que las que ahora últimamente las carnes en su jugo/también se ya se volvieron típicas de aquí de Guadalajara/y pues tenemos un una amplia gama de/de sabores/en nuestras comidas ¿verdad? | |

| ‘but the thing is that Guadalajara is a cosmopolitan city and that’s why; for instance, those steamed tacos and those with head and what… what do I know there are a lot of things that now… lately the meats in their own juice, they have also become typical here in Guadalajara and we have a wide range of flavors in our meals, right?’ | |

A more extreme example of a response with modification of topic is found in (12), where the informant does not answer directly the question ‘where are you living at the moment’ but rather modifies the topic and starts talking about her marriage – a related topic, but not identical to the one initiated by the interviewer. Both speakers then go on to talk about this new topic, not returning to the one initiated by the interviewer.

| Sociolinguistic interview PRESEEA MONR_M21_044, Monterrey, Mexico, 2006 | |

| E: | bueno/entonces/¿y orita tú dónde estás viviendo? |

| ‘BUENO so and where do you live right now?’ | |

| I: | bueno yo me volví a casar |

| ‘BUENO I got married again’ | |

| [two lines where I speaks of her marriage omitted] | |

| E: | y/¿y cómo te va con/con tu nuevo esposo? |

| ‘and, and how are things going with your new husband?’ | |

In both (11) and (12), bueno initiates a dispreferred second member of a question–answer adjacency pair, violating Grice’s (1975) maxims of manner (in Example 11) or relevance (in Example 12).

In dialogical contexts, bueno is also found in negative responses where the informant does not necessarily modify the topic presented in the question, but the answer itself is negative and hence dispreferred with regard to the first member of the adjacency pair. For instance, in (13), the informant indirectly offers the interviewer dinner or coffee, to which the interviewer provides a negative response hedged by bueno, arguably mitigating the face-threatening act of refusing a polite offer.

| Sociolinguistic interview MONR_M31_082, Monterrey, Mexico, 2006 | |

| I: | […] no pidió de cenar/no pidió café <risas> |

| ‘you didn’t want dinner, you didn’t want coffee’ <laughter> | |

| E: | bueno no/muchas gracias |

| ‘BUENO no, many thanks’ | |

Finally, dialogical bueno also occurs in contexts where it is not related to agreement or disagreement, but rather only signals a modification or change of topic. This is done more often by interviewers than informants, due to the asymmetrical nature of sociolinguistic interviews. For instance, in (14), the informant is first providing an answer to the interviewer’s question about playing basketball when he was younger. The interviewer then abruptly changes the topic and asks where the informant prefers to live. The turn-initial bueno signals and mitigates the change of topic, a dispreferred and face-threatening act.

| Sociolinguistic interview VALE_H13_020, Valencia, Spain, 1998 | |

| I: | […] no sé si tenía carrera o no sé si tenía futuro pero // ¿quién sabe? |

| ‘I don’t know if I would have had a career or if I would have had a future but, who knows?’ | |

| E: | bueno /¿dónde prefieres vivir en el campo o en la ciudad? |

| ‘BUENO where do you prefer to live, in the countryside or in the city?’ | |

| I: | mmm/no lo sé // yo en la ciudad vivo muy bien/[…] |

| ‘mmm, I don’t know, I like living in the city’ | |

The dialogical functions of bueno in our data thus range from agreement to disagreement, but in all uses the function of bueno is related with signaling that the response is dispreferred. In these dialogical contexts, bueno does not only mitigate the answer, but at the same time signals that there is gradual or total topic change.

In monological contexts, agreement and disagreement functions of bueno become less prominent, giving primacy to topic management functions. Thus, the monologization process can be understood as a gradual shift from more dialogical agreement/disagreement functions to more monological topic management functions in contexts where there is only one speaker or writer. Crucially for our purposes, this means that (a) the use of bueno is no longer governed by preference structure to the same extent as in dialogical contexts, leading to (b) a lack of politeness and mitigation effects typical for the use of bueno in dialogical contexts. Rather, the use of bueno as a discourse marker in monological contexts is made possible through fictive interaction where the utterance introduced by bueno resembles a dispreferred response to a fictive question (recall the discussion of Examples [6] and [7] above). In a second step, the monologization process would then involve a loss of the inherent polyphony created by using bueno in monological contexts. In other words, we posit that a degree of monologization of bueno is highest in monological contexts where its use has been routinized to such an extent that it can no longer be explained in terms of introducing a dispreferred response to a fictive first pair part.

The topic management function in monological contexts can be further divided into two subfunctions: (a) topic modification, such as introduction of a related subtopic or a new perspective to an old topic, and (b) change of topic. The topic modification function is illustrated in example (15), where the writer moves from the previous main topic (a person appearing in a YouTube video) to a new but related topic (another video where the same person auditions for a reality show). The topic modification function coincides with the first function of bueno distinguished by Briz et al. (2008), i.e., signaling that what follows is a continuation of something that has been said before and thus answering the fictive question ‘What does this have to do with the topic being discussed?’.

| Topic modification (CdE Mexico Blog) |

| Se acuerdan de el niño coreano que sale bailando en el video oficial de el ‘Gangnam Style’, para ser exactos sale en los minutos 0:16 y 0:21, bueno navegando por YouTube encontré el video donde audicionó a un reality coreano, que les robará más de una sonrisa. |

| ‘You might remember the Korean kid that dances in the official video of “Gangnam Style”, in minutes 0:16 and 0.21, to be exact, BUENO going through YouTube videos I found the video in which he auditioned in a Korean reality show, which will cause you to laugh more than once.’ |

A more radical topic change is found in (16), where the writer first wishes happy Father’s Day to an advice columnist and then proceeds to formulate her question. Here, the sentence introduced with bueno is arguably constructed as a response to the fictive question ‘What is your question?’ implicit in this interactional context.

| Topic change (CdE Spain Blog) |

| buenas días daniel por cierto feliz día del padre que fue ayer. bueno mi pregunta es que llevó unos 15 días tomandome la temperatura y la e tenido vaja […] |

| ‘Good day, Daniel, by the way a happy Father’s Day, which was yesterday. BUENO my question is that I have been taking my temperature for 15 days and it has been very low […]’ |

In addition to signaling a transition to a new topic related with the previous one, as in (15), the topic modification function can be associated with the admission of another perspective. This is illustrated by (17), where the writer admits that their advice is only valid if the recipient wants to maintain her friendship. Similarly, in (18) the writer admits that their evaluation of new metal music might be a matter of taste, thus limiting the validity of their previous evaluation. Crucially for our purposes, in such examples it would be difficult to reconstruct a fictive question to which the sentence introduced with bueno might be a response.

| Admission of another perspective (CdE Mexico General) |

| Animo, no estas sola estamos nosotros aquí para apoyarte, sabemos que te hace falta una amiga con quien llorar y desahogarte, un consejo debes de buscar a tu amiga poco a poco debes de hacer que vuelva esa amistad, bueno si tu crees y quieres esa amistad. |

| ‘Cheer up, you are not alone, we are here to support you, we know that you need a friend with whom to cry and vent, some advice you must look for your friend little by little, you must make that friendship come back, BUENO if you believe and want that friendship.’ |

| Admission of another perspective (CdE Mexico Blog) |

| en mi opinión el ñu metal es para fresas y personas que se quieren sentir malas oyendo grititos según eyos pero bueno cada quien su gusto |

| ‘In my opinion, nu metal is for superficial youngsters and people who want to feel bad hearing screams according to them, but BUENO, to each their own’ |

Finally, a more specific use of bueno in topic management is found in self-initiated repairs, as in (19), where the writer specifies that instead of not having observed something, they just had not stopped to think about it. As in (17) and (18), the use of bueno in these contexts appears to no longer be motivated in terms of fictive interaction. In our data, bueno seems not to be used in self-repairs of obvious mistakes (where other markers such as digo ‘I say’ are more common), but rather to nuance or modify a previous evaluation.

| Self-repair (CdE Spain Blog) |

| No me había dado cuenta. Bueno , sí, pero no me había parado a pensarlo. |

| ‘I had not noticed. BUENO, yes, but I hadn’t stopped to think about it.’ |

In summary, our descriptions of the functions of bueno lead us to propose that the monologization process of bueno can be modeled as in Table 4. After the use of bueno for (dis)agreement and mitigation connected to topic management is established in dialogical contexts (Stage I), speakers can exploit it for polyphony effects and topic management also in monological contexts (Stage II). Routinization of bueno in monological contexts leads to loss of the polyphony effect, and thus to the apparition of the perspective management functions (Stage III).

Monologization of bueno as a discourse marker.

| Stage I | Stage II | Stage III |

|---|---|---|

| Bueno mitigates a dispreferred response in dialogical contexts | Bueno is used in monological contexts and can be described as a dispreferred response to a fictive first pair part | Bueno is used in monological contexts, but can no longer be described as a dispreferred response to a fictive first pair part |

| Primarily disagreement/agreement functions | Topic management functions | Perspective management functions |

| First pair part uttered by previous speaker | First pair part attributed to a fictive interlocutor | No first pair part |

Crucially for our analysis in the rest of this paper, the description of monologization outlined in (20) goes beyond the original definition by Sansò (2022). The monologization of bueno does not only involve the use of an originally dialogic sequence in a monological context, but also a change in terms of the epistemic status of the first pair part. Whereas in Stage I, the first pair part is uttered by the previous speaker, in Stage II the first pair part is merely fictive. In Stage III, it is no longer possible to reconstitute a fictive first pair part.

6 Quantitative evidence of monologization

The hypothesis regarding the monologization of bueno laid out in Table 4 leads to measurable predictions regarding the distribution of this marker in spoken and written Spanish. While both spoken and written texts can be either monological or dialogical, they differ systematically in terms of the degree of integration of the situational context (Koch and Oesterreicher 1985: 20) and audience design (Bell 1984, 2001). We have assumed that the discourse marker bueno originated in contexts in which a dispreferred linguistic action is mitigated using the rhetorical strategy of displaying agreement with the interlocutor’s previous linguistic action. The necessity of employing mitigation strategies is correlated to the degree of integration of the situational context. In written texts such as internet blogs, where the addressee is an unknown group of readers, mitigation strategies are less relevant than in spoken texts like sociolinguistic interviews, in which interpersonal relations play a much more prominent role. If monologization can be defined purely in terms of using an originally dialogic sequence in a monological context, the use of bueno in spoken and written monological texts should not differ in terms of the distribution of topic management and perspective management functions. In contrast, if monologization is a type of semantic change, we would expect that written texts serve as a catalyst for the monologization of bueno (H1). This hypothesis leads to the prediction that there is a higher probability of using bueno for perspective management functions in written as opposed to spoken monological contexts. Conversely, we expect a lower probability of use of bueno with topic management functions in written as opposed to spoken monological contexts. This analytical approach allows us to test a hypothesis about historical language change in the absence of diachronic data: since the discourse marker use of bueno in writing is a feature of highly colloquial and informal texts such as blogs and discussion forums, it is underrepresented in historical corpus data even if it was used in writing.

Indeed, even if H1 concerning the elevated probability of use of bueno with perspective-managing functions in written monological texts is confirmed, this does not prove that bueno has routinized these functions. However, the fact that our data is stratified in terms of dialectal variation allows us to approach this question from a different angle: we can use a diachronic typological approach, in which language states regarding a particular grammatical phenomenon are reinterpreted as stages in one and the same diachronic process, such as grammaticalization (Croft 2013: 232–233). If we find measurable differences in the degree to which bueno has acquired perspective-marking functions in Mexican and Peninsular Spanish, this would strengthen our case that the monologization of bueno is in fact a diachronic process. The monologization of bueno is firmly connected to highly informal written texts, such as the online blogs we examine in this study. Given the lack of transmission of informal texts in language history (Labov 1994: 11) due to the fact that colloquial writing only started to emerge on a greater scale in the second half of the 20th century (Pons Bordería and Salameh Jiménez 2024), it is exceedingly difficult to trace monologization in actual longitudinal studies. The diachronic typological approach employed in this study allows us to circumvent this problem (Rosemeyer and Posio 2023).

As was mentioned in Section 4, we assume that bueno is less grammaticalized as a discourse marker in Mexican than in Peninsular Spanish (Rosemeyer and Posio 2023: 116). In Mexican Spanish, bueno is rather more frequently used as an adjective than in Peninsular Spanish. Prototypical usage contexts for adjectival bueno are attributive (20a) and predicative uses (20b), as well as exclamatives formed with the interrogative pronoun qué ‘how’ (20c).

| Es un amigo bueno. |

| ‘He is a good friend.’ |

| El ordenador es bueno. |

| ‘The computer is good.’ |

| ¡Qué bueno! |

| ‘Great!’ (Mexican Spanish)/‘How funny!’ (Peninsular Spanish) |

Table 5 summarizes the usage frequency of bueno in these contexts in Peninsular and Mexican Spanish according to the CdE. It demonstrates that adjectival bueno is more frequent in Mexican than in Peninsular Spanish in every one of these contexts.

Usage frequencies of adjectival bueno in Peninsular and Mexican Spanish in the CdE.

| Usage context | Usage frequency of bueno per million words in the CdE | |

|---|---|---|

| Peninsular Spanish | Mexican Spanish | |

| Attributive contexts (21a) | 21.41 (n = 9,832) | 24.25 (n = 6,319) |

| Predicative contexts (21b) | 39.15 (n = 17,984) | 44.24 (n = 11,528) |

| Exclamatives with qué (21c) | 2.39 (n = 1,097) | 4.70 (n = 1,225) |

In several of these contexts, there is variation between constructions with the adjective bueno and others with the adverb bien ‘well’ (see 21).

| El ordenador está bien. |

| ‘The computer is good/okay.’ |

| ¡Qué bien! |

| ‘Great!’ (both Mexican and Peninsular Spanish) |

Table 6 summarizes the usage frequencies of bien in these contexts in Peninsular and Mexican Spanish in the CdE. As shown in Tables 5 and 6, there is a preference for exclamative bueno in Mexican Spanish and exclamative bien in Peninsular Spanish. These results suggest a stronger specialization of bueno towards discourse-marking functions in Peninsular Spanish than in Mexican Spanish.

Usage frequencies of lexical bien in Peninsular and Mexican Spanish in the CdE.

| Usage context | Usage frequency of bien per million words in the CdE | |

|---|---|---|

| Peninsular Spanish | Mexican Spanish | |

| Predicative contexts (21a) | 33.22 (n = 15,260) | 26.52 (n = 6,910) |

| Exclamatives with qué (21b) | 4.96 (n = 2,276) | 1.90 (n = 494) |

In summary, comparison of the usage frequencies of bueno as a discourse marker and lexical item in Peninsular and Mexican Spanish, as well as the patterns of competition between bueno and bien, supports our assumption of a greater degree of grammaticalization of bueno towards discourse-marking functions in Peninsular than in Mexican Spanish.

This result allows us to take the dialectal variation in our data as a test case for the relationship between grammaticalization and monologization. If monologization is a historical process related to the development of discourse-marking functions, we can hypothesize that monologization of bueno has been implemented to a stronger degree in Peninsular than in Mexican Spanish (H2).

In order to test these hypotheses, it is necessary to evaluate to which degree bueno specializes in the expression of topic versus perspective management in written and spoken texts from Mexico and Spain. However, manual annotation of the discourse functions established in Section 5 is difficult and runs the risk of subjectivity. We therefore propose that the difference between topic and perspective management functions can be operationalized by looking at the expressions that follow bueno. Table 7 summarizes the distribution of the most frequent recurring expressions and expression types that follow bueno in our data, as well as our classification of these continuers in terms of the macro types of discourse functions established in Section 5.

Distribution and classification of the most frequent expressions following bueno.

| Continuation type | Expression | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| (Dis)agreement (ntotal = 98) |

Agreement (sí ‘yes’, claro ‘sure’, vale, ya ‘okay’, etc.) | n = 68 |

| Disagreement (no ‘no’, ni modo ‘surely not’, etc.) | n = 30 | |

| TopicManagement (ntotal = 639) |

pues ‘so’ | n = 270 |

| y ‘and’ | n = 112 | |

| pero/mas ‘but’ | n = 41 | |

| es que, resulta que ‘the thing is … ’ | n = 40 | |

| Topic-opening questions | n = 40 | |

| este, eeh, ehm (hesitation markers) | n = 19 | |

| entonces ‘so’ | n = 17 | |

| ahor(it)a ‘now’ | n = 17 | |

| porque ‘because’ | n = 13 | |

| Attention getters (mira ‘look’, oye ‘listen’, etc.) | n = 12 | |

| (vamos) a ver ‘let’s see’ | n = 11 | |

| Other expressions, with n < 10 | n = 47 | |

| Perspectivization (ntotal = 323) |

Stance markers (yo ‘I’, a mí ‘to me’, creo ‘I believe’, digamos ‘let’s say/assume’ etc.) | n = 183 |

| Conditional sentences | n = 36 | |

| Epistemic adverbials (la verdad [es que] ‘in truth’, tal vez ‘maybe’, en realidad, realmente ‘really’ etc.) | n = 50 | |

| Evidential expressions (según X ‘according to’, dicen [que] ‘they say [that]’, es sabido que ‘it is well-known that’) | n = 12 | |

| Other expressions, with n < 10 | n = 42 |

In order to carry out a quantitative analysis of our data in terms of the distribution of types of continuers, a number of data elimination processes were necessary. First, we restricted the data to monological, i.e., turn- and sentence-medial, contexts. This step was necessary because our hypotheses do not concern the position of bueno within a turn, but the type of discourse functions expressed by bueno in turn-/sentence-medial positions. Elimination of turn-/sentence-initial uses led to a dataset of n = 2,156 turn-medial tokens of bueno. Second, our hypotheses do not lead to predictions regarding the global likelihood of continuers being used in our data. We consequently excluded all cases of bueno from our data in which the following element was not evidently indicative of its discursive function. This reduction process led to a final dataset of n = 771 turn-medial tokens of bueno and a following element. Even if more than half of the turn-medial tokens of bueno were consequently left out, the resulting dataset is large enough to warrant a probabilistic analysis.

We conducted a multinomial logistic regression analysis (Levshina 2015: 277–289; Orme and Combs-Orme 2009: Ch. 3; Rosemeyer and Enrique-Arias 2016) calculating the correlations between the dependent variable ContinuationType, with three levels ([Dis]agreement, TopicManagement, Perspectivization), a predictor variable Corpus with two levels (CdE, PRESEEA), a predictor variable Dialect with two levels (Mexican Spanish, Peninsular Spanish), as well as the interaction between Corpus and Dialect. The analysis was performed in R (R Development Core Team 2024), using the multinom() function from the nnet package (Venables and Ripley 2002).

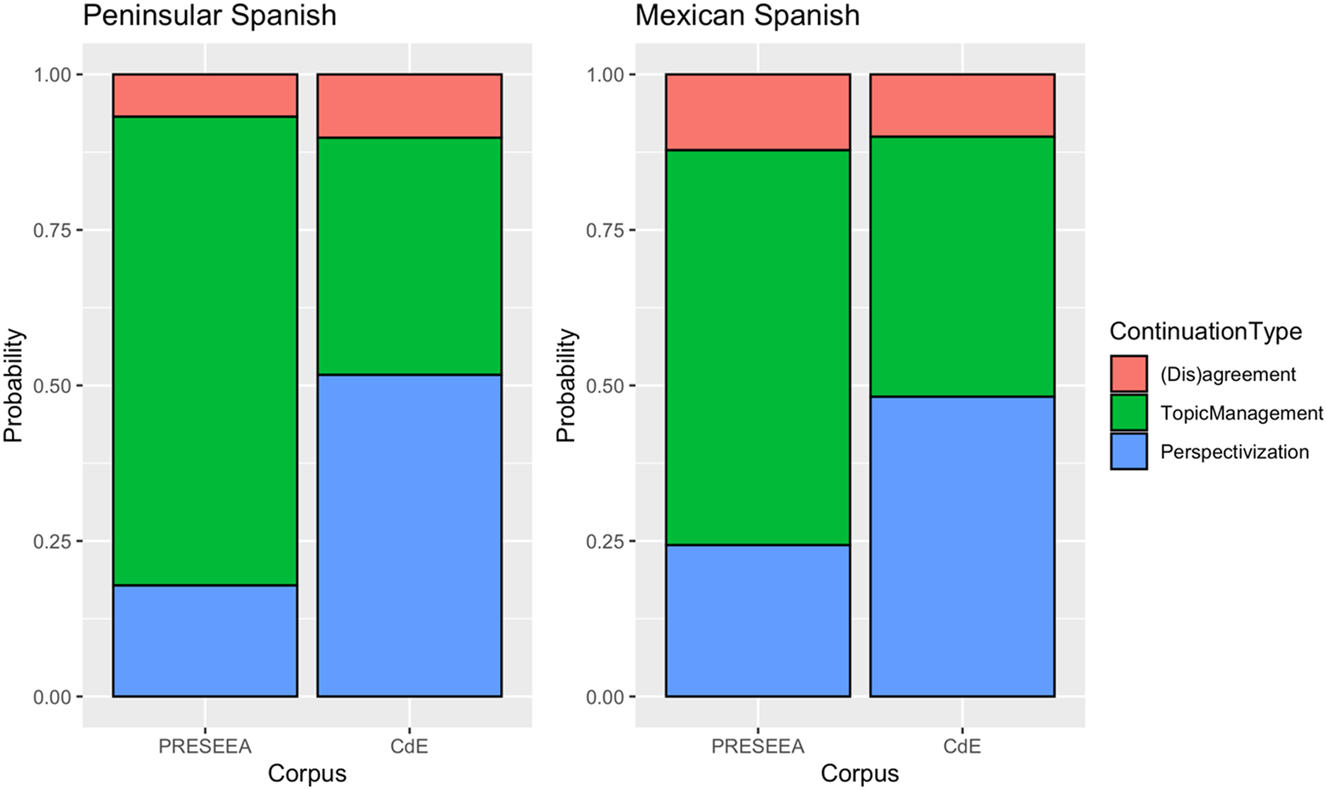

Figure 1 visualizes the probabilistic distribution of ContinuationType by Corpus and Dialect. It demonstrates a consistent difference between the use of bueno in written (CdE) and spoken monological data (PRESEEA) in terms of the probability of use of continuers. In particular, in both Peninsular and Mexican Spanish, elements following bueno are more likely to express topic management than perspectivization functions in spoken than in written texts. In contrast, the elements following bueno are more likely to express perspectivization functions than topic management functions in written than in spoken texts. The main effect of Corpus reaches high statistical significance (see Table 8 in the Appendix for a complete summary of the results from the regression analysis).

Probabilistic distribution of ContinuationType by Corpus and Dialect (results from multinomial logistic regression analysis).

The analysis did not find a significant difference between Peninsular and Mexican Spanish texts in terms of the probability of use of (dis)agreement, topic continuation, and perspectivization continuers after bueno (variable Dialect). Regarding the interaction effect between Corpus and Dialect, the tendency for written monological texts to favor perspectivization continuers is slightly stronger in Peninsular than in Mexican texts. However, this result only reaches marginal statistical significance (p = 0.07) in the analysis.

The results from our quantitative analysis clearly support H1, the assumption that written texts may serve as catalysts for monologization processes. If monologization was independent from linguistic modality (spoken vs. written texts), we would not expect a difference between spoken and written texts in terms of the typical discourse functions of turn-/sentence-medial bueno. In contrast, our results indicate that bueno is more likely to be used with perspectivization functions, and less likely to be used with topic management functions, in written than in spoken texts.

Regarding H2 – the assumption of Peninsular Spanish presenting a more advanced monologization, suggested by the higher usage rate, indicative of a more advanced grammaticalization – our results are inconclusive. The regression model did not find a significant difference between Peninsular and Mexican Spanish regarding the distribution of discourse functions of bueno. Likewise, the interaction effect between Corpus and Dialect did not reach statistical significance, although the direction of the effect – slightly stronger tendency for written monological texts to favor perspectivization in Peninsular than in Mexican texts – is in line with H2.

7 Conclusions

The present study contributes in two ways to the increasing body of studies on Spanish discourse markers and, in particular, the discourse marker bueno. First, we established a description of the discourse functions of bueno in spoken and written informal texts (sociolinguistic interviews and internet blogs from Mexico and Spain), proposing a new, unified account of these functions based on the conversational principles of preference and mitigation. The dialogical function of the discourse marker bueno can be described as mitigating dispreferred second pair parts such as disagreeing responses. Unlike previous accounts, this description also explains the uses of bueno in contexts such as over-informative or hedged agreeing responses.

Second, the study also set out to explore whether the discourse marker bueno is undergoing a process of monologization whereby an originally dialogic sequence starts to be used within a single turn or sentence. Our analysis associated the emergence of topic management functions of bueno with its use in monological, i.e., turn- or sentence-medial, contexts where bueno is used to introduce an utterance that can be conceptualized as a dispreferred response to a fictive, implicit first pair part. In line with the definition of monologization developed in Sansò (2022), this means that an originally dialogic sequence starts to be used in monological contexts. In other words, our analysis describes the emergence of topic management functions as a second stage in the monologization of bueno, retaining the original mitigation function despite the interaction being fictive.

In a third stage of the monologization of bueno, we document a perspective management function that had not been described systematically in previous literature. In this function, bueno downplays the validity of the speaker’s or writer’s previous evaluation, providing a new perspective to the discourse topic without a full-fledged topic shift. Crucially, in such contexts, the utterance introduced with bueno can no longer be described as a dispreferred response to an implicit and fictive first pair part. Perspective-managing bueno thus exhibits the highest degree of monologization of the discourse particle, given that there is neither genuine nor fictive dialogue involved and the original interactional function is lost.

The description of the monologization of bueno based on our qualitative analysis allowed us to formulate two hypotheses concerning the nature of monologization as a historical process that were tested by comparing the distribution of the discourse functions of bueno in spoken and written texts. First, we assumed that written data would show more frequent use of bueno for perspectivization, the most grammaticalized and monologized of the functions of the discourse particle. Second, we assumed – based on evidence from previous studies and the higher frequency of discourse marker bueno in Peninsular Spanish – that the monologization of bueno would have reached a higher level in Peninsular as opposed to Mexican Spanish. While the quantitative comparison of spoken and written data revealed clearly confirm the first hypothesis, there is less conclusive evidence for the second hypothesis. Although the discourse-particle use of the form bueno is more frequent than its adjectival use in spoken Peninsular Spanish, the dialectal difference is leveled in the written data. However, we did find a slightly stronger tendency for the perspectivization function to occur in monological written contexts in Peninsular Spanish. Subsequent analyses of informal written data including blogs, chats, and forum texts from both dialects might shed more light on eventual differences in the current written usage of bueno. Of course, it would be even better to study the diachronic change in historical data. However, as mentioned in Section 6, this endeavor would face severe difficulties due to the scarcity of data. Indeed, it is possible that the use of bueno in writing is related to the emergence of the new communicative contexts, media, and discourse traditions such as blog texts and discussion forums.

In addition to contributing to the description of the Spanish discourse marker bueno by proposing a new, unified account of its functions based on the conversational principles of preference and mitigation, the present paper proposes a grammaticalization path from the adjective meaning ‘good’ to dialogical uses for agreement and disagreement, followed by turn-taking and topic management functions, and finally the perspective management function. We have also shown how the distribution of the functions is affected by a change from dialogical to monological discourse contexts and, in parallel, from spoken to written medium, thus enriching and supporting the monologization account proposed by Sansò (2022).

-

Competing interests: The authors declare none.

-

Data availability: The data and R code necessary to reproduce the analyses presented in this paper are publicly available at https://osf.io/4n9tw/ (last accessed 22 July 2024) under the CC-By Attribution 4.0 International license. DOI https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4N9TW.

Appendix: Results from the multinomial logistic regression analyses

Table 8 illustrates the results from the multinomial regression analyses. It gives the coefficient (Coeff) and the p value calculated for each of the levels of the predictor variables for each of the three levels of the dependent variable ContinuationType. Because the reference level of the dependent variable is set to TopicManagement, the coefficients refer to the probability of use of one of the two other levels in comparison to TopicManagement in these specific usage contexts. The tables also give the total number of occurrences for each variable level, as well as the relative frequencies of the four constructions for each variable level.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis. Dependent variable ContinuationType (reference level = TopicManagement), n = 1,014.

| Variable | Effect type | Level | n | TopicManagement | (Dis)agreement | Perspectivization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rel. Freq. % | Rel. Freq. % | Coeff | Std. error | p value | Rel. Freq. % | Coeff | Std. error | p value | ||||

| (Intercept) | – | – | – | – | – | −1.43 | 0.36 | <0.001 | – | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.482 |

| Corpus | Main effect | CdE | 803 | 39.9 | 10.1 | Reference level | 50.0 | Reference level | ||||

| PRESEEA | 1,353 | 69.6 | 9.4 | −0.22 | 0.39 | 0.567 | 21.0 | −1.10 | 0.25 | <0.001 | ||

| Dialect | Main effect | Mexico | 1,062 | 57.1 | 11.5 | Reference level | 31.4 | Reference level | ||||

| Spain | 1,094 | 64.3 | 7.8 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.815 | 27.9 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.564 | ||

| Corpus:Dialect | Interaction effect | PRESEEA:Spain | – | – | – | −0.86 | 0.56 | 0.122 | – | −0.64 | 0.35 | 0.069 |

-

Notes: Model formula: ContinuationType ∼ Corpus + Dialect + Corpus: Dialect. Model evaluation statistics: AIC = 1,307.69, Residual deviance = 1,291.69.

References

Auer, Peter. 2005. Projection in interaction and projection in grammar. Text – Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 25(1). 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.2005.25.1.7.Suche in Google Scholar

Bauhr, Gerhard. 1994. Funciones discursivas de bueno en español moderno. Lingüística Española Actual 16. 79–124.Suche in Google Scholar

Bell, Allan. 1984. Language style as audience design. Language in Society 13(2). 145–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004740450001037X.Suche in Google Scholar

Bell, Allan. 2001. Back in style: Reworking audience design. In Penelope Eckert & John R. Rickford (eds.), Style and sociolinguistic variation, 139–169. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Borreguero Zuloaga, Margarita. 2017. Los relatos coloquiales: Partículas discursivas y polifonía. Pragmalingüística 25. 62–88. https://doi.org/10.25267/pragmalinguistica.2017.i25.04.Suche in Google Scholar

Briz, Antonio, Salvador Pons Bordería & José Portolés Lázaro. 2008. Diccionario de partículas discursivas del español. Madrid: Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología. www.dpde.es (accessed 21 March 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Casartelli, Daniela Elisabetta, Silvio Cruschina, Pekka Posio & Stef Spronck (eds.). 2023. The grammar of thinking: From reported speech to reported thought in the languages of the world. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Cresti, Emanuela & Massimo Moneglia. 2005. C-ORAL-ROM: Integrated reference corpora for spoken Romance languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 2013. Typology and universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Davies, Mark. 2016. Corpus del español, web/dialects. http://www.corpusdelespanol.org/ (accessed 15 February 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Detges, Ulrich & Richard Waltereit. 2016. Grammaticalization and pragmaticalization. In Fischer Susann & Gabriel Christoph (eds.), Manual of grammatical interfaces in Romance, 635–658. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Fernández Madrazo, Carmen & Araceli López Serena. 2022. De la atenuación a la cohesión: La polifuncionalidad de los mecanismos pragmático-discursivos más allá de los marcadores. Anuari de Filologia. Estudis de Lingüística 12. 247–274. https://doi.org/10.1344/afel2022.12.11.Suche in Google Scholar

García Vizcaíno, María José & Miguel A. Martínez-Cabeza. 2005. The pragmatics of well and bueno in English and Spanish. Intercultural Pragmatics 2(1). 69–92. https://doi.org/10.1515/iprg.2005.2.1.69.Suche in Google Scholar

Grice, H. Paul. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Peter Cole & Jerry L. Morgan (eds.), Syntax and semantics, 41–58. New York: Academic Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd. 2002. On the role of context in grammaticalization. In Ilse Wischer & Gabriele Diewald (eds.), New reflections on grammaticalization, 83–101. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Koch, Peter & Wulf Oesterreicher. 1985. Sprache der Nähe – Sprache der Distanz: Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachtheorie und Sprachgebrauch. Romanistisches Jahrbuch 36. 15–43. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110244922.15.Suche in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 1994. Principles of linguistic change, vol. 1: Internal factors. Oxford: Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Landone, Elena. 2009. Los marcadores del discurso y la cortesía verbal en español. Bern: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Levshina, Natalya. 2015. How to do linguistics with R. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Llopis Cardona, Ana. 2016. Significado y funciones en los marcadores discursivos. Verba 43. 231–268. https://doi.org/10.15304/verba.43.2112.Suche in Google Scholar

Llopis Cardona, Ana & Salvador Pons Bordería. 2020. Discourse markers in Spanish. In Dale A. Koike & César Felix-Brasdefer (eds.), The Routledge handbook of Spanish pragmatics, 185–202. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

López Serena, Araceli & Margarita Borreguero Zuloaga. 2010. Los marcadores del discurso y la variación lengua hablada vs. lengua escrita. In Óscar Loureda Lamas & Esperanza Acín Villa (eds.), Los estudios sobre marcadores del discurso en español, hoy, 415–495. Madrid: Arco Libros.Suche in Google Scholar

Maldonado, Ricardo & Patricia Palacios. 2015. Bueno, a window opener. In Daems Jocelyne, Zenner Eline, Heylen Kris, Speelman Dirk & Cuyckens Hubert (eds.), Change of paradigms – New paradoxes, 97–108. Berlin, Munich & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Martín Zorraquino, María Antonia & José Portolés. 1999. Los marcadores del discurso. In Ignacio Bosque & Violeta Demonte (eds.), Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, vol. 3, 4051–4212. Madrid: Espasa.Suche in Google Scholar

Martínez Hernández, Diana. 2016. Análisis pragmaprosódico del marcador discursivo bueno. Verba 43. 77–106. https://doi.org/10.15304/verba.43.1888.Suche in Google Scholar

Orme, John G. & Terri Combs-Orme. 2009. Multiple regression with discrete dependent variables. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Pascual, Esther. 2006. Fictive interaction within the sentence: A communicative type of fictivity in grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 17(2). 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1515/COG.2006.006.Suche in Google Scholar

Pascual, Esther. 2010. Interacción ficticia en español: De la conversación a la gramática. Dialogía 5. 64–98.Suche in Google Scholar

Pascual, Esther. 2014. Fictive interaction: The conversation frame in thought, language, and discourse. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Pascual, Esther & Todd Oatley. 2017. Fictive interaction. In Barbara Dancygier (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of cognitive linguistics, 347–360. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Pons Bordería, Salvador. 2003. From agreement to stressing and hedging: Spanish bueno and claro. In Gudrun Held (ed.), Partikeln und Höflichkeit, 219–236. Bern: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Pons Bordería, Salvador & Shima Salameh Jiménez. 2024. From synchrony to diachrony: The study of the 20th century as a distinct place for language change. In Salvador Pons Bordería & Shima Salameh Jiménez (eds.), Language change in the 20th century: Exploring micro-diachronic evolutions in Romance languages, 1–16. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Posio, Pekka & Malte Rosemeyer. 2021. Pragmatics and word order. In Dale A. Koike & César Felix-Brasdefer (eds.), The Routledge handbook of Spanish pragmatics, 73–90. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Preseea. 2014. Corpus del Proyecto para el estudio sociolingüístico del español de España y de América. Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá. http://preseea.linguas.net (accessed 6 January 2020).Suche in Google Scholar

R Development Core Team. 2024. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org (accessed 5 March 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Raymond, Chase Wesley. 2018. Bueno-, pues-, and bueno-pues-prefacing in Spanish conversation. In John Heritage & Marja-Leena Sorjonen (eds.), Between turn and sequence: Turn-initial particles across languages, 59–96. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Suche in Google Scholar

Real Academia Española. 2023. Corpus del Español del Siglo XXI (CORPES). http://www.rae.es (accessed 2 January 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Rosemeyer, Malte & Andrés Enrique-Arias. 2016. A match made in heaven: Using parallel corpora and multinomial logistic regression analysis to analyze the expression of possession in Old Spanish. Language Variation & Change 28. 307–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954394516000120.Suche in Google Scholar

Rosemeyer, Malte & Pekka Posio. 2023. On the emergence of quotative bueno in Spanish: A dialectal view. In Stef Spronck, Daniela Casartelli, Silvio Cruschina & Pekka Posio (eds.), The grammar of thinking: From reported speech to reported thought in the languages of the world, 107–140. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Sansò, Andrea. 2022. Discourse markers from processes of monologization: Two case studies. In Miriam Voghera (ed.), From speaking to grammar, 201–225. Bern: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1972. Notes on a conversational practice: Formulating place. In David Sudnow (ed.), Studies in social interaction, 75–119. New York: Free Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2007. Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. & Harvey Sacks. 1973. Opening up closings. Semiotica 8. 289–327. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1973.8.4.289.Suche in Google Scholar

Serrano, María José. 1999. Bueno como marcador discursivo de inicio de turno y contraposición: Estudio sociolingüístico. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 1999(140). 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1999.140.115.Suche in Google Scholar

Stukenbrock, Anja. 2013. Sprachliche Interaktion. In Peter Auer (ed.), Sprachwissenschaft: Grammatik – Interaktion – Kognition, 217–259. Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer.Suche in Google Scholar

Venables, William & Brian Ripley. 2002. Modern applied statistics with S. New York: Springer.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- What a nominal predicate may mean: eel, merfolk, and other creatures

- Left Dislocation in Spoken Hebrew, it is neither topicalizing nor a construction

- Semantic variation and semantic change in the color lexicon

- Creativity, paradigms and morphological constructions: evidence from Dutch pseudoparticiples

- Referential means in German: an experimental study comparing feminine epicene nouns with masculine generic nouns

- Between (anti-)grammar and identity: a quantitative and qualitative study of hyperdialectisms in Brabantish

- Dialogical and monological functions of the discourse marker bueno in spoken and written Spanish

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- What a nominal predicate may mean: eel, merfolk, and other creatures

- Left Dislocation in Spoken Hebrew, it is neither topicalizing nor a construction

- Semantic variation and semantic change in the color lexicon

- Creativity, paradigms and morphological constructions: evidence from Dutch pseudoparticiples

- Referential means in German: an experimental study comparing feminine epicene nouns with masculine generic nouns

- Between (anti-)grammar and identity: a quantitative and qualitative study of hyperdialectisms in Brabantish

- Dialogical and monological functions of the discourse marker bueno in spoken and written Spanish