Abstract

We conducted a study on how people refer to gender-neutral, grammatically feminine role or job nouns in German, like “die Lehrkraft” (the teacher [fem.]), and compared it to masculine role or job nouns, like “der Lehrer” (the teacher [masc.]). We found that people use different pronouns depending two factors: the grammatical gender of the nouns and the social gender associated with these nouns, that means how gender-typical these nouns are perceived to be. Our results showed that grammatically masculine role or job nouns were almost always referred to with masculine pronouns. In contrast, grammatically feminine role or job nouns were more often referred to in ways that could apply to any gender. We take this as support that these terms have a gender-neutral interpretation. We conclude that grammatically feminine, gender-neutral role or job nouns are better for being inclusive in German than masculine role or job titles, which tend to have a male bias. This research is important to anyone in the German-speaking community striving for gender equality.

1 Introduction

The German language has three grammatical genders in the singular: feminine, masculine and neuter. Nouns that denote women are usually assigned feminine gender (e.g., die Frau ‘the woman’, die Hebamme ‘the midwife’, die Lehrerin ‘the female teacher’), and nouns denoting men typically have masculine gender (e.g., der Mann ‘the man’, der Onkel ‘the uncle’, der Lehrer ‘the male teacher’). Neuter is rarely used for human entities. Exceptions include references to children (e.g., das Kind ‘the child’, das Neugeborene ‘the newborn’, das Mädchen ‘the girl’), some neuter epicene nouns (e.g., das Opfer ‘the victim’, das Mitglied ‘the member’, das Individuum ‘the individual’), and a few derogatory nouns used with reference to women (e.g., das Weib ‘the hag’, das Luder ‘the hussy’, das Mensch ‘the person [pejorative]’, used instead of the usually masculine form der Mensch ‘the person’ [Nübling and Lind 2021]).

In the plural, nouns referring to humans have traditionally been formed using grammatical forms which correspond to the singular masculine forms (e.g., der Lehrer ‘the teacher [singular]’ – die Lehrer ‘the teachers [plural]’). For this reason, plural forms such as die Lehrer ‘the teachers (plural)’ have been regarded by some scholars as the “generic masculine” forms. Such forms have been used to refer to groups of people of mixed socio-cultural genders, as opposed to forms such as die Lehrerinnen ‘the teachers’, which refer to groups consisting exclusively of females. The generic masculine form in the singular, e.g., der Lehrer ‘the teacher’, has traditionally been used with generalised meaning to refer to individuals of any socio-cultural gender.

Today, the generic masculine is at the centre of an increasingly heated debate that has polarised German speakers across the nation. The debate concerns gender-equitable language and prompts the question of how the German language can be made more gender-inclusive and gender-fair, which means making women and diverse (e.g., transgender,[1] intersex, non-binary) individuals more visible. Extensive research has been conducted on the linguistic means to achieve gender-fairness as well as the potential effects of gender-inclusive forms (e.g., Bruns and Leiting 2022; Diewald and Nübling 2022; Kotthoff 2020, 2022; Kotthoff and Nübling 2018; Löhr 2022; Nübling 2020; Schunack and Binanzer 2022).

The proponents of gender-inclusive language state that if not only men, but also women, transgender, intersex and non-binary people are referred to, the language should make that reference explicit. Based on this approach, gender-inclusive plural forms such as LehrerInnen (with capitalised “I”), Lehrer/-innen, Lehrer_innen, Lehrer*innen ‘teachers’ (all meaning ‘teachers [plural; gender-inclusive]’), die Lehrenden ‘those who teach’ and die Lehrkräfte ‘teaching staff’ have been proposed for use in German instead of generic masculine plural forms such as die Lehrer ‘teachers [plural]’, as they correspond to specifically male forms, in this case der Lehrer ‘the (male) teacher’. Thus, when the form die Lehrer ‘teachers [plural]’ is used, it is not straightforwardly clear whether a group of people of mixed genders or a group of men only is referred to. In response to this debate, the DUDEN (Kunkel-Razum et al. 2020) changed its online entries for human nouns, adding the feminine versions. This influential dictionary of the German language has also re-defined masculine versions of entries with human reference as referring only to men instead of everyone (previously, the generic use), thereby reducing their dominant reading to male-specific and non-generic ones (i.e., der Lehrer ‘a male person teaching at a school’).[2]

Opponents of this approach describe such efforts as not only too convoluted linguistically but also unnecessary given the conventionalised genericity of the masculine form. They fear that the language will be degraded by the creation of artificially complicated linguistic structures that are too complex to use, often striving for linguistic conservatism.

The issue of gender-equitable language is causing an enormous rift in the German-speaking society, evident not only in vehement linguistic and journalistic discussions, but also in court cases (some of which led to a change in the German gender-equality laws). For example, in December 2018, a “third” legal gender category was introduced in Germany based on a decision by the Federal Constitutional Court (see Dunne and Mulder 2018 for a detailed description). The court case involved an intersex German plaintiff, a registered female whose chromosomal make-up did not fit the binary sex division. The case lasted four years and ended up with the German government being ordered to establish a third gender option for intersex persons, who may now register within the category divers ‘diverse’ in the civil registry. In consequence, all legal documents in Germany must now include three gender options: m (männlich ‘male’), w (weiblich ‘female’), and d (divers ‘diverse’), as well as the category keine/ohne Angabe ‘not specified’. In a less successful court case that same year (2018), a woman sued her bank for addressing her using the generic masculine form der Kunde ‘client’ instead of the feminine equivalent die Kundin ‘client (female)’. The court ruled in favour of the bank, stating that the masculine form used generically does not violate the German gender-equality laws.

While some embrace attempts to make the German language more gender-inclusive and gender-fair in order to increase the visibility of women, transgender, intersex, and non-binary individuals, others see such attempts as an intrusion on the established traditional use of the German language, specifically its linguistic economy. This conflict raises important questions with high social relevance concerning societal values and gender-equity policy in Germany. How to include people of all genders? How to address everybody rather than primarily men? How to use language that does not disadvantage individuals of diverse genders? The present study is a contribution to this discussion, in the hope of shedding some light on these pressing questions for the German society by investigating the grammatical and semantic effects of the choice of referential means in contemporary German.

This article is organised as follows: Section 2 provides a brief overview of some previous studies on the generic masculine and its alternatives in German; Section 3 outlines our research methodology; Section 4 presents the data analyses and findings of the study; and Section 5 contains concluding remarks.

2 Previous studies

There are multiple studies of German grammatical gender showing that the generic masculine is interpreted as having male connotations (meaning that a male individual is assumed), thus creating a so-called “male bias”[3] in the language. This challenges the intended generic meaning of such forms, making female and diverse individuals less visible or even excluding them when the generic masculine is employed. For example, Gygax et al. (2008: 480) observe that the generic use of the masculine form “biases gender representations in a way that is discriminatory to women” (see Diewald and Steinhauer 2017; Elmiger et al. 2017; Ivanov et al. 2018; Wetschanow 2017 for a similar view). Gender-fair language is considered more appropriate for making social roles and professions accessible, and once these can be occupied by anyone, “more gender-balanced mental representations [of these roles] should emerge” as the stereotypes derived from observing a certain gender in certain roles would no longer be “backed by a higher prevalence of men […], which facilitates their cognitive accessibility”, resulting in a male bias of linguistic asymmetries (Sczesny et al. 2016: 7).

Because of the high social relevance of people’s roles and professions, a large part of the research body on the generic masculine has focused specifically on such terms. As Schütze (2020: 43) notes, these are the social domains in which gender proportions matter most for equal opportunities: “These areas of personal expressions have been reconstructed as the crux of the matter where [grammatical and social gender] interactions demand empirical material to discuss and re-evaluate said interactions and the linguistic and social behaviour we derive from them”.

In what follows, we provide – in chronological order – short descriptions of some empirical studies on German that we consider most relevant for the present experimental work, as they investigate how reference is established on the sentence-level and in short sections of text.

Scheele and Gauler (1993) investigated generic expressions of human reference in each grammatical gender in German: masculine (e.g., der Mensch ‘the human’), neuter (e.g., das Individuum ‘the individual’), and feminine (e.g., die Person ‘the person’). They conducted two experiments. In the first one, sentences were completed with free associations in the participants’ own words. In the second one, completions were realised via multiple choice options. The results revealed that two grammatical genders (masculine and neuter) exhibited a male bias in the responses, while feminine gender included men and women in nearly equal proportions.

In Heise (2000), the participants were asked to write stories about given sentences which were presented in the generically intended plural (e.g., die Schüler ‘the pupils’), so-called “gender-balanced” (masculine-feminine) pairs (e.g., Lehrer ‘teachers’ and Lehrerinnen ‘female teachers’), orthographic alternatives (e.g., VegetarierInnen ‘vegetarians [masc./fem.]’ or Vegetarier/innen ‘vegetarians [masc./fem.]’), and with gender-nonspecific plural forms (e.g., Kinder ‘children’, as opposed to the gender-specific forms Jungen ‘boys [masc.]’ and Mädchen ‘girls [fem.]’). The stories were analysed for cues to gender-marked reference. Once again, masculine nouns resulted in mostly male associations being evoked, as primarily male-centred stories were produced. Only grammatically feminine variants with capitalised “I” (e.g., VegetarierInnen ‘vegetarians’) increased female reference, even producing a female bias in some cases (Heise 2000).[4]

Questionnaire responses as well as proportions of women and men estimated for social role and profession nouns in the generic masculine forms, gender-balanced masculine-feminine pairs and capital “I” forms (see examples directly above) were collected from the research group by Braun, Stahlberg and Sczesny. This group added copious evidence to the findings reported above on the improvement of female visibility under gender-fair forms in contrast to the “generic” masculine forms (see Braun et al. 2005 for a review of the cognitive effects of gendered language). Their research confirmed a male bias associated with the masculine forms of reference (Braun et al. 1998; Stahlberg and Sczesny 2001). However, no advantage over the generic masculine forms was found for gender-nonspecific forms (sometimes also termed “gender-neutral”). At the time of their publication, alternative forms such as Studierende ‘students (gender-neutral)’ had no effect on female visibility, hence perpetuating a male bias (Braun et al. 1998).

Irmen and Roßberg[5] (2004) investigated anaphoric reference between a pronoun and its noun antecedent. The experimental sentences introduced a role noun and were continued with a coreferential pronoun agreeing with the referent’s grammatical or semantic gender, causing a mismatch if the pronoun referring to the preceding noun phrase conflicted in gender due to grammatical or conceptual incongruency: “Ein Elektriker … er / sie …” (‘An electrician [masc.] … he / she …’). In other words, social roles and professions were presented in the singular with generic descriptions of contexts and then resolved with a gender-specifying subclause. The experiment was designed in parallel to further studies of similar material, in which the fit between the first sentence subject and the subsequent gendered anaphoric reference, i.e., these two sources of information about gender, moderated reading times of the two clauses. Findings indicate that both grammatical and stereotypical information on gender “contribute to the mentally represented person information” (Irmen and Roßberg 2004: 293). Their experiments showed that both stereotypical associations of the noun and grammatical gender information influences processing of the subsequent anaphoric continuation. The authors included feminine epicenes (e.g., die Aushilfe ‘the help [fem.]’), for which stereotypical information trumped the grammatical gender.

Thurmair (2006) presents a detailed empirical study based on a large German corpus and some experimental approaches to establishing reference in German. She investigates discrepancies between the grammatical gender of a noun and the gender (referred to as “sex”) of a person to which that noun refers (what she calls “gender-sex-divergent nouns”). Thurmair argues that with such nouns, there is a strong tendency by German speakers to use gender-convergent pronominal forms, especially in the domain of personal pronouns (das Model [neuter] – sie [fem.] instead of es [neuter] ‘the model – she’), except for relative pronouns and articles whose grammatical gender is employed under anaphoric reference in such cases. It was also shown that in the cases of appositions formed with such nouns, proforms tend to be gender-based, that is, to agree semantically, in narrow appositions, while they are grammatically congruent in broad appositions. The impact of gender-stereotypicality or differences in language forms referring to female or male referents were not addressed explicitly by Thurmair (2006).

Oelkers (1996: 6) came to a similar conclusion when she presented fill-in-the-gap texts using nouns “with gender-neutral denotations” of different grammatical genders (feminine, masculine, neuter, e.g., der Filmstar [masc.], die Person [fem.], das Opfer [neuter] – er [masc.] / sie [fem.] / es [neut.] ‘the movie star’, ‘the person’, ‘the victim’ – ‘he/she/it’). Overall, semantic agreement based on referential gender prevailed, from which Oelkers (1996) concludes a systematic relation, a dependency even, between grammatical and “biological” gender. Additionally, an influence of feminist language politics is assumed.

Klein (2022) argues that the division of human nouns into different noun classes, i.e., grammatical gender categories, is problematic. He presents two empirical case studies that support this claim. He shows that epicene nouns in German (“Epikoina”), usually attributed gender-nonspecific meanings as they “lack” a gender cue (2022: 235), are not entirely free of gender implications. Thus, the term “Pseudoepikoina” is introduced to denote nouns that do not have a gender-specific counterpart, yet specifically do not fulfil such function of gender indifference, but rather behave according to the referential implication. In addition, Klein (2022) proposes important insights on changes in the German gender system. First, he suggests that the avoidance of the generic masculine may lead to an increasing use of grammatically feminine forms, such as those with feminine grammatical suffixes (e.g., -kraft: Hilfskraft, Fachkraft). Second, his questionnaire illustrates that German feminine forms are viewed by speakers as more gender-neutral, compared with masculine forms. However, this was inferred by the first names provided by the participants in reference to the tested epicene nouns. The author concludes that it would be important to verify these claims by other research studies, which, as a starting point, is realised in the present study.

Schütze (2020) presents behavioural data that justify recommendations to use gender-nonspecific alternatives. In her visual world study using eye-tracking, the participants reliably identified a mixed gender group as referents for gender-nonspecific forms in the plural, such as die Lehrkräfte (‘the teachers’/‘the teaching persons’). In contrast, the plural noun die Lehrer ‘the teachers’, which coincides in its grammatical form with the masculine singular noun der Lehrer ‘the teacher [masc.]’, was too often inferred as male-specific to be a successful generic candidate, i.e., in almost half of the cases it was interpreted to refer exclusively to a male-only group. Gender-nonspecific nouns such as Lehrkräfte ‘teachers’/‘teaching persons’ belong to the strategy known as “gender neutralisation”, aimed at achieving a gender-fair and non-discriminatory use of language (Braun et al. 2005; Formanowicz et al. 2013; Rothmund and Scheele 2004). Schütze (2020) concludes that such language use must level up with the reality of gender diversity and the striving for equal opportunities, following in the steps of researchers who have repeatedly shown the practical consequences of gender-fair profession nouns (e.g., Formanowicz et al. 2013), namely how the language used in job advertisements either encourages or discourages choices and hiring (Horvath 2015). Within a non-heteronormative language policy that also includes non-binary genders, gender-neutralising terms are ranked highest in Motschenbacher’s (2014: 255) recommendations for gender-inclusive language.

Motschenbacher (2010) describes an experimental study in which masculine (e.g., der Flüchtling ‘the fugitive [masc.]’, der Mensch ‘the human [masc.]’) and feminine (e.g., die Person ‘the person [fem.]’, die Bedienung ‘the waiter [fem.]’) nouns were analysed and compared in terms of their gender typicality. The study involved a small-scale questionnaire survey filled in by 34 female and 29 male students at a German university. The participants were asked to rate the relevant nouns on a 7-point Likert scale reflecting their perception of the socio-cultural genders (1 = “strongly male”, 7 = “strongly female”). Interestingly, Motschenbacher (2010: 45) observes “a slight […] female bias” in the results for feminine nouns, as they yield higher average scores compared with masculine nouns. For example, the feminine nouns die Aushilfe ‘the temporary worker (fem.)’ and die Bedienung ‘the waiter (fem.)’ all had scores higher than average, closer to the “strongly female” perception. Though small in scope, this study illustrates that in German, it is not only masculine nouns that evoke male biases, but also feminine ones that can evoke female biases. Using the insights from Motschenbacher (2010),[6] it was our goal in this work to analyse and compare German masculine and feminine social role and profession nouns in order to understand if they can induce male and female biases, respectively. Another question is, if they do, whether there is any difference between them with regard to gender typicality.

3 Research methodology

We designed and administered an online survey for adult native speakers of German. The survey was advertised on various social media platforms, a number of professional language and linguistic lists as well as participant pools. It was freely available online for 8 weeks (October – November 2021). Any native German speaker over the age of 18 at the time of the experiment who wished to participate in this survey could do so. Participation was entirely voluntary, and people were able to withdraw from the study at any time they wished. The survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete. The first page contained a consent form explaining the participants’ rights and the goals of the study. The participants were informed that the data collected would be used only for academic purposes. In the experiment, no information that would identify the participants appeared with the data, as each one was anonymised by using a code number known only to the investigators to identify them.

The participants were asked to provide their gender identity if they wished to do so. The options included female/male/diverse gender identities as well as keine Angabe ‘no answer’. We thus relied on gender self-identification by the participants using the gender options legally recognised in Germany. We further asked which pronoun the participants preferred to use in reference to themselves (she, he, the singular they as in English, “no pronoun/only the name”, or “no answer”). The participants were also asked to indicate if they belonged to, were close to, or distant to the LGBT*QIA+ community. In addition, they were asked to state if they were a member of FLINTA+ (females, lesbians, inter, non-binary, trans, agender people, typically sharing a feminist perspective).[7] At the end of the survey, the participants were invited to give feedback (opinions, critique, questions, inputs) regarding the questionnaire.

The study was built on an online survey platform (www.surveyhero.com, previously known as www.esurvey.com) which allows users to create their own surveys using templates that can be individualised using a drag-and-drop menu, adapting the survey tools to particular research needs. It is possible to design a single survey but run two versions of it (corresponding to the two conditions) in so-called “monadic testing”. In this case, implementing different survey versions that share a common set-up ensures that the generated link redirects to one of the two lists[8] randomly per participant visit to the link, and then selects version A or B to be presented. This allows researchers to pre-define the surveys and have participants spread evenly across both versions.

The body of the survey consisted of two main parts: (i) a sentence completion task, and (ii) a rating task. The first task was an extended cloze exercise in which a given continuation to a simple sentence was to be completed. For this purpose, a generic statement about a person in a social or professional role appeared for each item, containing desired or generalised characteristics of this referent, e.g., Ein Lehrer sollte weltoffen sein ‘A teacher should be open-minded’ in the masculine condition, or in the second version Eine Lehrkraft sollte weltoffen sein ‘A teaching person should be open-minded’ in the feminine condition.[9] Following the first sentence, the initial phrase was given: Zum Beispiel sollte … ‘For example should …’ and synonymous conjunctions or juxtaposed collocations like Unter anderem … ‘Among others’ or Außerdem … / Darüber hinaus … ‘Additionally’/ ‘Furthermore’ with a modal verb (see Table A in the Appendix for all presented sentence items). The blank space text field after the open continuation was to be filled in by participants, who were asked to type in freely and complete the sentence. This gap was inserted in such a way that, syntactically, it would likely elicit a response containing referential terms to a noun phrase in the first sentence. The social role and profession nouns of the stimulus sentence were expected to prompt anaphoric co-reference in the second clause to be established in relation to the first universal description of the role or profession, as the participants were expected to keep a connection between the first (given) and second (self-typed) sentence. The coreferential element could be a personal pronoun referring back to the introduced referent, in agreement with the latter, as German requires adherence to a noun’s grammatical gender. Congruency was expected to be matching in number – that is, in the singular –, somewhat restricted in grammatical gender – feminine or masculine for human referents –, and open in referential gender, since a teacher, for example, could be of male, female, diverse or simply unknown gender. Unlike previous questionnaires of this kind (a more restrictive method was used by Heise 2000; Klein 1988; Scheele and Gauler 1993), there was no introduction of a single outstanding gap to be filled. We improved the design of Scheele and Gauler (1993) to merge both a reference prompt and a more open association (more targeted than completely free writing in their Experiment 1 and more natural than forced multiple choice in Experiment 2), as well as leaving the option of a circumvention of any (pro-)nominal specification, as this may indicate or result from missing gender cues in cases of nonspecific, epicene nouns. Examples of referential means and the way they were coded are given in Table 2 in the next section. By eliciting written sentence continuations to human referents, as described above, the effect of grammatical gender on the preferred referentiality was assessed. German requires the third person singular pronouns (sie ‘she’, er ‘he’, es ‘it’) to agree in grammatical gender with their antecedents. In the case of human nouns, a conflict may arise when agreement is semantic (i.e., congruent with the referent’s socio-cultural gender identity) instead of being grammatical (i.e., abiding by the rules of grammar). Thus, a feminine epicene noun, such as die Sicherheitskraft ‘the security guard (fem.)’, in reference to a male individual may be referred to with the masculine pronoun er ‘he’ (i.e., semantic agreement), instead of the feminine pronoun sie ‘she’ (i.e., grammatical agreement). The choice is informative of either language-internal grammatical or language-external socio-cultural gender cues (in German, there is no good equivalent of the English gender-neutral “singular they” pronoun).[10] We have focused on -kraft, -hilfe, and -person compounds, as such feminine epicenes constitute a very productive word formation strategy in the language.

Besides the open writing task, the survey included a noun typicality rating. All role and profession nouns contained in the simple declarative sentences to be continued by the participants in the writing part of the study (Experiment 1) were to subsequently receive rating values according to gender typicality of the respective occupation in Experiment 2. After having included each noun for personal reference in a sentence in the previous task, the participants were presented individually with a scalar gradient on which degree and direction of typicality was indicated (ranging from the concepts Frauen ‘women’ on the left to Männer ‘men’ on the right extreme). The nature of Experiment 2 and its results are described in detail in Schütze and Steriopolo (forthcoming).

The participants were given a practice example with detailed task explanations. They were instructed to follow their intuition and to respond quickly when (i) writing down a continuation (e.g., by further describing, giving general statements or relying on their own experiences about the introduced referential from the previous sentence), and (ii) deciding on a typicality value for the social roles and professions presented. The study was designed so that the participants proceeded through the experiment incrementally, item by item, for sentences and ratings, to avoid extensive re-consideration and hence re-adjustments emerging from later processes of re-interpretation. This setting was considered essential to minimise the amount of re-formulated answers and ratings grades aligned with other responses given.

4 Results

The sentence completion task in Experiment 1 yielded observations on the use of kinds of, and preferences for, referential expressions specifying the referents’ socio-cultural genders based on written sentence continuation responses. Altogether, these observations illuminate potential differences between two types of nouns denoting humans with masculine or feminine grammatical gender. According to German grammatical rules, gender categories must agree – a masculine noun requires masculine reference and a feminine noun requires feminine reference. Incongruencies and imbalances, if present in the data, will point to asymmetries and the impact of non-grammatical factors such as typicality or the role of participants’ demographic properties, both of which are analysed below.

Ninety-nine participants (having applied selections to the initial 133 participants as in Table 1) aged 18–70 years took part in the survey.

The inclusion criteria.

| Declaration of consent to take part | First or most familiar language | Age (year of birth) |

|---|---|---|

| “yes” | German | 18+ (2003 or earlier) |

The inclusion criteria defined above (declaration of consent to participate in the study as well as having German as their first or most familiar language) led to the exclusion of 34 participants. Thus, of the potential 133 participants, 99 who completed the survey remained for the analysis, which amounts to an exclusion rate of 26 %.[11] The overall dropout rate resulting from incomplete surveys was much higher, however, reflecting experiences with other questionnaire-based studies that lament the large amount of people whose interest is piqued at first, who inspect and start a survey but then terminate early and quit. One more person was excluded from the rating analysis because their typicality values remained at zero, indicating the scalar device was not moved but simply clicked through the ratings, leaving data from 98 participants.

Of these, the majority indicated “female” as their gender identity (n = 70), 27 “male”, and 2 “diverse”.[12] The majority belonged to the early adulthood generation (mean age = 33.96 years, similar for both versions).

The respondents’ relationship to the LGBT*QIA+ community was mainly reported as “close” (n = 46), followed by “distant” (n = 24) and “belonging” (n = 18). Thus, the total community affiliation of the categories proximity (being “close”) and membership (“belonging”) amounted to almost three quarters (n = 64), which will further be treated as adjacent and non-adjacent. Thirteen participants considered themselves to be “additionally FLINTA+” and ten participants did not provide an answer to the question.

4.1 Referential means

In total, we collected 1,422 means of reference in response to the sentence completion task (787 in the feminine and 635 in the masculine condition). In the post-experimental analysis of responses produced, we annotated each anaphoric referential element to the given social role and profession noun that appeared in the formulated responses to Experiment 1. For this purpose, the following coding scheme (see Table 2) was used to account for any means of reference encountered. Examples in this section stem from the sentence completions collected from the participants.

The coding scheme to annotate written responses to the sentence continuations.

| Referential means | Examples from response data | No. of responses containing these per condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feminine | Masculine | |||

| Masculine reference | Masculine pronoun | er, der, dieser ‘he’ |

15 | 558 |

| Masculine noun | ein Arzt ‘a doctor (m.)’, ein Türsteher ‘a bouncer (m.)’, ein Pychologe ‘a psychologist (m.)’ |

7 | 5 | |

| Feminine reference | Feminine pronoun | sie, die, diese ‘she’ |

596 | 1 |

| Feminine noun | eine Vertrauenslehrkraft ‘a liaison teacher (f., GN)’,a eine Kellnerin ‘a waitress’ |

5 | 3 | |

| Other | Neutral pronoun | es ‘it’ |

4 | 2 |

| Plural | [sollten] sie ‘should (pl.)’ |

1 | 4 | |

| Repetition | Repetition (of the given noun form) | 17 | 8 | |

| Avoidance | “man” circumvention | [sollte] man stets die Sicherheit im Auge behalten ‘one should always keep an eye on safety’ |

5 | 4 |

| Missing reference | No means of reference (to the given referent / personal noun) | [sollte] auf Sicherheit und Sauberkeit geachtet werden ‘safety and cleanliness should be minded’ |

60 | 43 |

| Inclusive reference | Inclusive pronouns | er/sie; sie oder er; er:sie; sie*er; sein*ihr; ihre oder seine; etc. ‘he or she’, ‘hers or his’, ‘he*she’ |

57 | 9 |

| Inclusive nouns | die oder der [Noun]; der:die [Noun] ‘theFEM or theMASC’; die Person ‘the person’ |

20 | 13 | |

| Conflicts in agreement (i.e., masc. pronoun and fem. noun, or fem. pronoun and masc. noun) | er

i

(m.) [sollte] eine gute Arbeitskraft

i

(f.) ‘he [should be] a good worker (GN)’ sie (f. [die Person]) [ist] ein Kontakt (m.) ‘she [is] a contact (m.)’ |

0 | 3 | |

-

aHere, we use the abbreviation GN for “gender-neutral” to highlight a difference between masculine nouns and feminine epicene nouns, the difference not visible in the English translations, such as “teacher”, etc.

Each linguistic unit was counted that co-referred with the referent of the initial sentence, either a masculine or feminine noun. We did not focus on any other elements in the responses that were not coreferential with another discourse entity. Note that the category “missing reference” also includes responses that did contain a referential element, but one referring to another, new and stimulus-external referent (e.g., [Beispielsweise sollte] der Arbeitgeber… ‘[For example,] the employer [should] …’, sollten die Experimente … ‘the experiments should …’ when the sentence introduced Laborkraft ‘lab assistant’). Such linguistic units that were not coreferential with the social roles and professions under discussion were excluded from the analysis, as they did not provide cues to the referent’s socio-cultural gender.

Note also that inclusive pronouns could be paired reference (e.g., er oder sie ‘he or she’) or orthographically marked for gender inclusivity (as is ever more common in German – er*sie ‘he*she’ and er:sie ‘he:she’, symbolising a spectrum of gender identities, including non-binary ones), as in [Unter anderem sollte] sie*er sich gut durchsetzen können ‘Among others, she*he should be able to assert oneself’ when referring to Pflegekraft ‘caregiver [fem.]’.

Moreover, we applied a hierarchical process in the coding of responses that contained more than one means of reference, or even conflicting referential elements regarding grammatical gender. For example, some participants continued the sentence about a profession in the masculine form (here, Saisonarbeiter ‘seasonal worker’) with [Außerdem sollte] er eine gute Arbeitskraft sein ‘[In addition], he [masc.] should be a good worker [fem.]’.

While many cases in which either feminine or masculine reference was established via pronouns or nouns were straightforward, such instances of incongruency and agreement rule violation were not rated as an either masculine pronoun or feminine noun, but as “inclusive” – due to the apparently deliberate attempt to be gender-fair instead of grammatically consistent. Likewise, if reference was established by using der Mensch ‘the human [masc.]’ or die Person ‘the person [fem.]’, it was annotated as “inclusive” (not as a masculine or feminine noun) because of the evident strategy of truly generic, gender-fair reference. The hierarchy also applied to any use of inclusive strategies on top of grammatical agreement coded as the inclusive means of reference, as in [Darüber hinaus kann] sie häufig ein_e Expert_in auf dem jeweiligen Gebiet sein ‘[Furthermore,] she can be an expert [masc._fem.] on the respective field’ or [Zum Beispiel sollte] er nicht ein geschwätziger Mensch sein ‘[For instance,] he [should] not be a gossipy person (lit. human)’ in reference to Ansprechpartner ‘contact [masc.]’. Whenever a grammatically matching feminine or masculine pronoun (er ‘he’ or sie ‘she’) was not employed in a continuation of the sentence, but the introduced subject was repeated instead, e.g., Eine Ansprechperson … – [Zum Beispiel sollte] die Ansprechperson ein offenes Ohr für die Anliegen haben. ‘A contact person [fem.] …’ – ‘[For example,] the contact person [fem.] should have an empathetic ear for the concerns’, it was treated as an attempt to circumvent a pronominal specification of the referent’s gender. Other ways of avoiding anaphoric reference included utterances with generalised meaning (or avoidance of co-reference), passive constructions, change of subject, etc. These cases were coded as “zero reference” to a given role or profession noun. Rarely, a plural form or the neuter pronoun es ‘it’ were found in the responses coded as “other”.

4.1.1 Choice and distribution by condition (grammatical gender)

For the quantitative analysis, we subsumed feminine (pro)nouns under (a) feminine forms of reference (n = 605), and masculine (pro)nouns under (b) masculine forms of reference (n = 570), as these show concord with the grammatical gender of a referent noun; (pro)nominal inclusive forms were categorised as (c) inclusive reference (n = 99); missing, passive or referential terms with generalised meaning (“man”) were classified as (d) avoidance of a specific reference (n = 112); recurring identical noun forms were subsumed under (e) repetition of the referent (n = 25); and finally, we summarised neutral pronominal and plural references under (f) other instances of reference (n = 11).

The data were transformed into counts of how often the different types of linguistic means were mentioned by referential option (feminine, masculine, inclusive, neutral, plural forms of reference or avoidance and the ones with generalised meaning) and condition (feminine vs masculine noun), as outlined above. The results are presented in Figure 1. The percentages of referential means encountered in the sentence completion section can be found in Table B of the Appendix at the end of this article.

Types of referential means used for feminine or masculine role and profession nouns by condition.

In the questionnaire version using masculine grammatical gender for nouns, the sentences were predominantly continued with masculine forms of reference: there were 86.3 % masculine pronouns when the referent noun was in the masculine form, as opposed to only 2.8 % for epicene feminine nouns. The mirror image was found for the other version of the questionnaire, which presented epicene feminine forms: sentences were mostly continued with feminine pronominal reference (76.4 % versus a negligible 0.6 % in the masculine version).

The fact that feminine means of reference were used for feminine nouns and masculine forms of reference for social role and profession nouns in the masculine gender, with very few exceptions (see Figure 1), is unsurprising in light of German gender agreement rules: it reflects grammatical restrictions of congruency in the language. What is striking, however, is the asymmetry: feminine referents did not lead to feminine reference as strongly as masculine referents evoked masculine reference, as illustrated by the asymmetric proportions of feminine nouns – feminine referential means, and masculine nouns – masculine referential means in Figure 1. Apparently, other types of referential means were used instead. In fact, when drawing attention to the relative distribution of referential means to contrast the conditions, the difference in use of inclusive reference is remarkable. Epicene nouns in the feminine grammatical form led to more than three times more inclusive pronominal means than were used for masculine nouns (9.8 % vs 3.5 %). Furthermore, reference was avoided one third more often in sentence continuations following a feminine referent (8.3 %) than in continuations following a masculine noun (7.4 %). Social role and profession nouns were repeated almost twice as often in the epicene feminine (2.2 %) than masculine (1.3 %) version of the questionnaire, though this was not a frequent strategy overall. Instances of other referential means, such as the use of the pronoun man with generalised meaning for an impersonal, non-gender-specific statement or plural forms were comparably low in both conditions, with relative frequencies of <1 %.

Based on morphological structure and pragmatic function, we hypothesised more gender-sensitive, i.e., inclusive means of reference to co-occur with feminine epicene nouns, which the descriptive analysis clearly supports. Crucially, the feminine epicene nouns tested in this study contained the suffixes -kraft, -hilfe and -person, which Klein (2022: 184) termed “human suffixes”, given their morphological expression of some gender-abstract human entity involved in the relevant social roles and professions. Indeed, the inclusive means of reference to the presented role and profession nouns were much more preferred in the feminine over the masculine noun forms.

Figure 1 displays the cumulative percentages of referential means contained in the written sentence continuations of statements in the masculine and feminine versions of the survey. Social role and profession nouns given in a preformulated sentence were referred to with distinct linguistic means by the participants: the distribution of the referential usages analysed differs between conditions (a masculine vs feminine noun introducing a referent).

Below, we statistically compare both conditions with respect to the referential means the two grammatical genders prompted for a social role and profession noun. Differences of using the six types of referential means between the two conditions reached high significance in a chi-square test of association (χ2(5) = 981, p < 0.001) with a large effect size (Cramer’s V = 0.88).[13]

4.1.2 Choice and distribution by item

Here we report the social role and profession nouns that received the largest percentage of one specific type of referential means. Referents that were “service workers”, “carers/supervisors”, “care takers”, “office workers” or “teachers” were referred to with feminine grammatical gender elements most frequently (all above 45 %). Evidently, these are professions from the social domain and/or low-prestige jobs. Referents that denoted “paralegals”, “security service” and “emergency workers” had the highest number of masculine elements to establish reference (all above 44 %). The most inclusive referential means were used with “contact” and “reference person”, as well as “office worker” (all above 8 %). Referential means were avoided the most with “lab worker”, “contact” and “reference person” (all above 11 %). In the next section, we delve into the differences between conditions – that is, the grammatical gender of a noun form and a noun’s gender typicality, addressing the following question: Does the semantic component of how gender-typical a social role or profession is affect the referential means chosen to refer to a given referent?

4.1.3 Interactions with noun typicality

For the following presentation of the results, we analyse the second part of the study, namely the typicality ratings for the social role and profession nouns in the feminine and masculine versions (see Table B in the Appendix), in which we investigated the impact of a noun’s gender typicality (as highly typically female, highly typically male, or low, meaning balanced) on the choice of referential means used. Rating values for each role and profession noun, the impact of condition – i.e., the grammatical gender the noun was presented in – and the demographic effects of gender, age and LGBT*QIA+ adjacency are reported in Schütze and Steriopolo (forthcoming). The additionally collected gender typicality of social role and profession nouns from “typically female” to “typically male” was associated with these forms to a different degree according to socially informed cues to gender. Yet this depended on the grammatical genders. If a noun was presented in its masculine form, the proportion of “men” who typically take a role or perform a job was increased in the scalar ratings, hence we observe a male bias (similar to the result reported in Motschenbacher 2010).

In the data, we find that nouns of high female typicality receive the largest amount of feminine means of reference (Bürokraft ‘office worker [fem.]’, with a median typicality rating value of -50 indicating highly female-typical interpretations, has 81.5 % feminine means of reference; Betreuungsperson ‘carer/supervisor [fem.]’ has a rating of -55 and 80.4 % feminine means of reference). At the same time, these items were also often referred to in an inclusive way (Bürokraft [fem.]: 15.7 %). These noun forms contain the word stem -hilfe, -kraft or -person and hence support the notion of a signalling effect of such nouns toward a meaning of gender-fairness. For example, Bürohilfe ‘office worker [fem.]’ and Rechtsanwaltshilfe ‘paralegal [fem.]’ were referred to with inclusive means of reference in 15.7 % and 11.3 % of the responses, while their supposedly generic masculine counterparts remained at about 2 %. The -kraft suffix in many feminine epicenes elevated feminine referential elements, too, as shown by items like Rettungskraft ‘emergency worker [fem.]’ (9.8 %), Pflegekraft ‘caregiver [fem.]’ (12 %) and Servicekraft ‘service worker [fem.]’ (13.5 %), but these likewise came with female-typical ratings. Another factor that increased the inclusive means of reference was a balanced typicality rating. This also led to more cases of avoidance. Lehrkraft ‘teacher [fem.]’, with a median rating value of low female typicality (-15.0), had 11.5 % inclusive means; Ansprechperson ‘reference person [fem.]’, with a rating value of -20.0, had 9.4 % inclusive means and 15.1 % avoided reference; similarly, Kontaktperson ‘contact person [fem.]’ had a centred rating of 0.0, 17.5 % inclusive means and 12.5 % avoided reference. Strikingly, to establish reference without relying on agreeing, binary grammatical gender seems to be mainly necessitated by non-gender-typical social roles and professions when a semantic gender cue is not additionally driving grammatical choices. There are, however, exceptions, such as the highly female-typical Haushaltshilfe ‘household help [fem.]’ and Pfleger ‘carer [masc.]’, for which avoidance of referential means was 11.6 % and 12.2 % respectively. These findings show that stereotypical gender information can be countered by deliberately not using grammatical cues to referential gender.

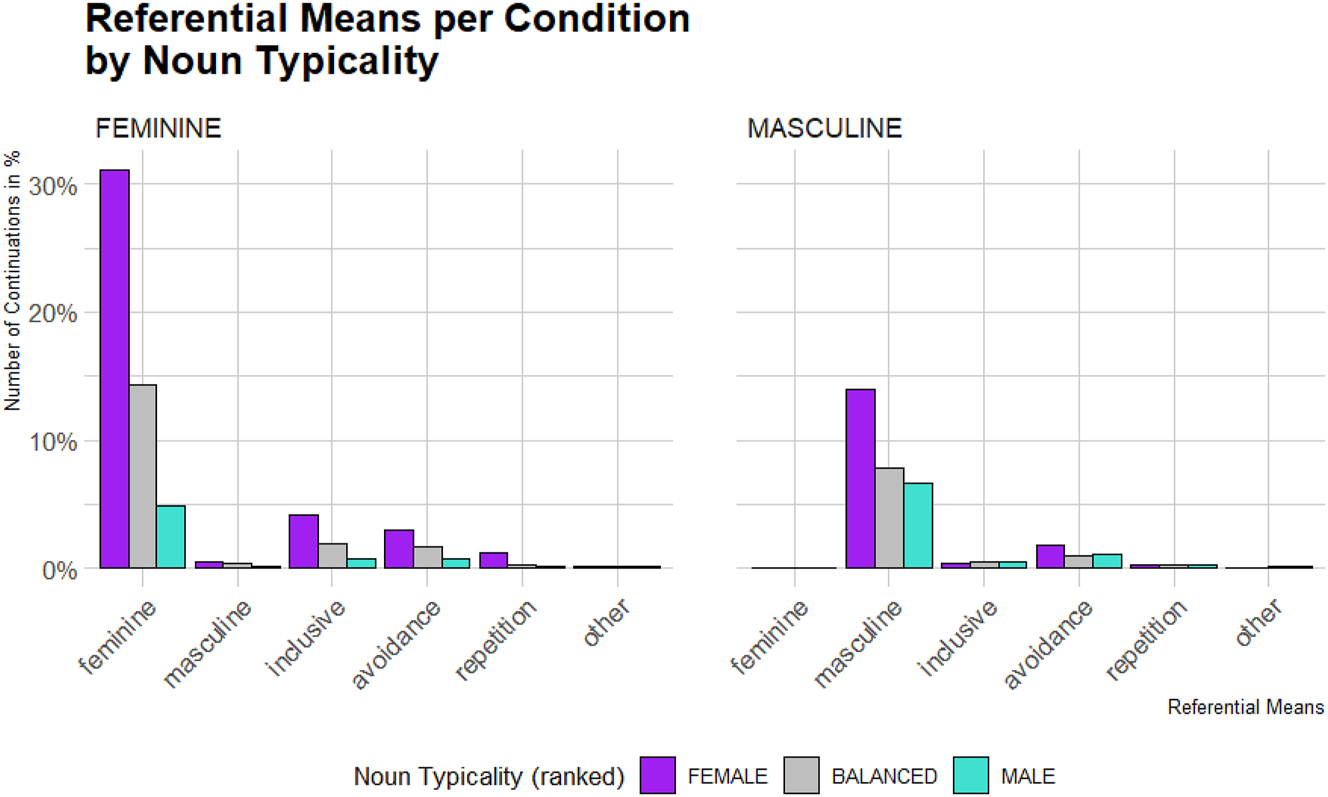

Table C in the Appendix provides percentage proportions of the types of referential means for each item in both conditions, for masculine and epicene feminine nouns denoting social roles and professions. To inspect correlations visually, the response data were further split by the given ratings, grouped into noun gender typicality ranks of female, male or balanced derived from the scalar values of Task 2 as illustrated in Figure 2[14] below, with the aim of analysing the referential means in response to differently gender-typical social role and profession nouns.

Types of referential means used for feminine and masculine nouns by typicality rank (female, balanced, male gender typicality) for each condition.

The socio-semantic information reflected in the gender typicality ratings played a role when establishing reference in both the feminine and masculine versions. Figure 2 gives an indication of a typicality-dependent use of reference in the data: with increased female typicality for a noun, masculine forms of reference were produced less often than feminine forms. A balanced gender typicality, on the other hand, reduced the amount of congruent masculine or feminine reference elements for nouns. The data illustration supports the finding that inclusive forms were used more frequently for feminine epicene nouns (see the left panel of Figure 2). Even so, feminine forms of reference were never given for masculine role or profession nouns in the inspected data set, regardless of how female in gender typicality a referent was rated.[15] Those items that had received highly female and balanced typicality lacked forms of reference more than highly typical male nouns did. Laborant ‘lab assistant [masc.]’, for example, had the most instances of avoided reference in the analysed item set, and both this form and its feminine alternative die Laborkraft ‘the lab assistant [fem.]’ obtained the fewest feminine and masculine means of reference in the respective condition. Interestingly, inclusive elements were most frequently employed when referring to highly female-typical roles or professions of feminine gender.

Gender typicality seems to drive masculine grammatical gender choices when typicality is on the extremes of highly (fe)male typicality, whereas a low rating value (around zero, the centre of the scale) that indicated balanced gender typicality for a noun can elicit inclusive (and avoid gender-specific) reference more often. The relatively small effects of variation between grammatical gender conditions are in line with a cross-linguistic study by Gygax et al. (2008: 464), which found that stereotypicality had a higher influence on gender-unmarked items in English than languages like German and French, “where interpretations were dominated by the masculinity of the masculine […]”. The consistency of fewer grammatically congruent references irrespective of a grammatical gender category may hint at the underlying fact that nouns which are neither female-specific nor male-typical but more gender-neutral evoke less formal agreement that is not exploited – or exploited less – for the gender specification of referents.

To single out the effects of the grammatical gender of a noun form, a linear regression analysis was performed with type of referential means as the dependent variable (that is, the frequency with which a form of reference was observed in the data), gender typicality as a covariate (this value comprised how typically female, male or balanced a noun was rated) and condition (a masculine or feminine noun form) as a factor. For this purpose, referential means were each recoded in a binary way (occurrences indexed with 1). Recall that typicality direction (termed “rank” above) captured whether a noun was rated as female / balanced / male, while typicality degree reflects the extent to which a noun was rated as gender-typical (values from 0 to 100, with higher numbers indicating more pronounced gender typicality and lower numbers meaning low typicality).

For feminine means of reference, typicality degree as a covariate did just reach significance (t = 2.28, p = 0.022), with typicality direction reaching low significance for the male-balanced values (t = -2.22, p = 0.026 comparison [but female-balanced n.s.] and a large R2 = 0.535), meaning that condition accounts for a large proportion of variance in the data. Thus, when the typicality of a noun was rated as rather balanced, feminine means of reference became more probable than when it was rated as male.

For the masculine means of reference, typicality degree was highly significant (t = -3.492, p < 0.001) and typicality direction was significant for the female-balanced comparison (t = 3.478, p < 0.001), but n.s. for male-balanced, which means that when the typicality of a noun was rated rather female, masculine means of reference were used less often irrespective of condition (with an even larger R2 = 0.711), once more pointing to the combined impact of noun form grammatical gender and noun gender typicality on the choice of agreeing means of reference.

For inclusive means of reference, typicality degree was not found to be significant in this analysis, neither was typicality direction significant in any comparison: the production of inclusive referential forms was independent of a noun’s gender typicality, yet highly related to condition (t = -9.267, p < 0.001), which reaffirms that the masculine condition received fewer inclusive means than the feminine one. In each analysis, condition was highly significant, which substantiates the observation above. For cases in which referential means were avoided, typicality degree as a covariate was not found significant in this analysis, neither was typicality direction a factor in any comparison. Nominal repetition as a means of reference remained non-significant, as did other means of reference besides the frequent types listed.

4.2 Choice and distribution by the participants’ demographics

As the variation outlined in the previous section leaves questions about whether it arises across gender identities and ages or is specific to a particular demographic, we sub-analysed the results by three demographic factors: gender identity (Section 4.2.1), LGBT*QIA+ community affiliation (Section 4.2.2), and age (Section 4.2.3).

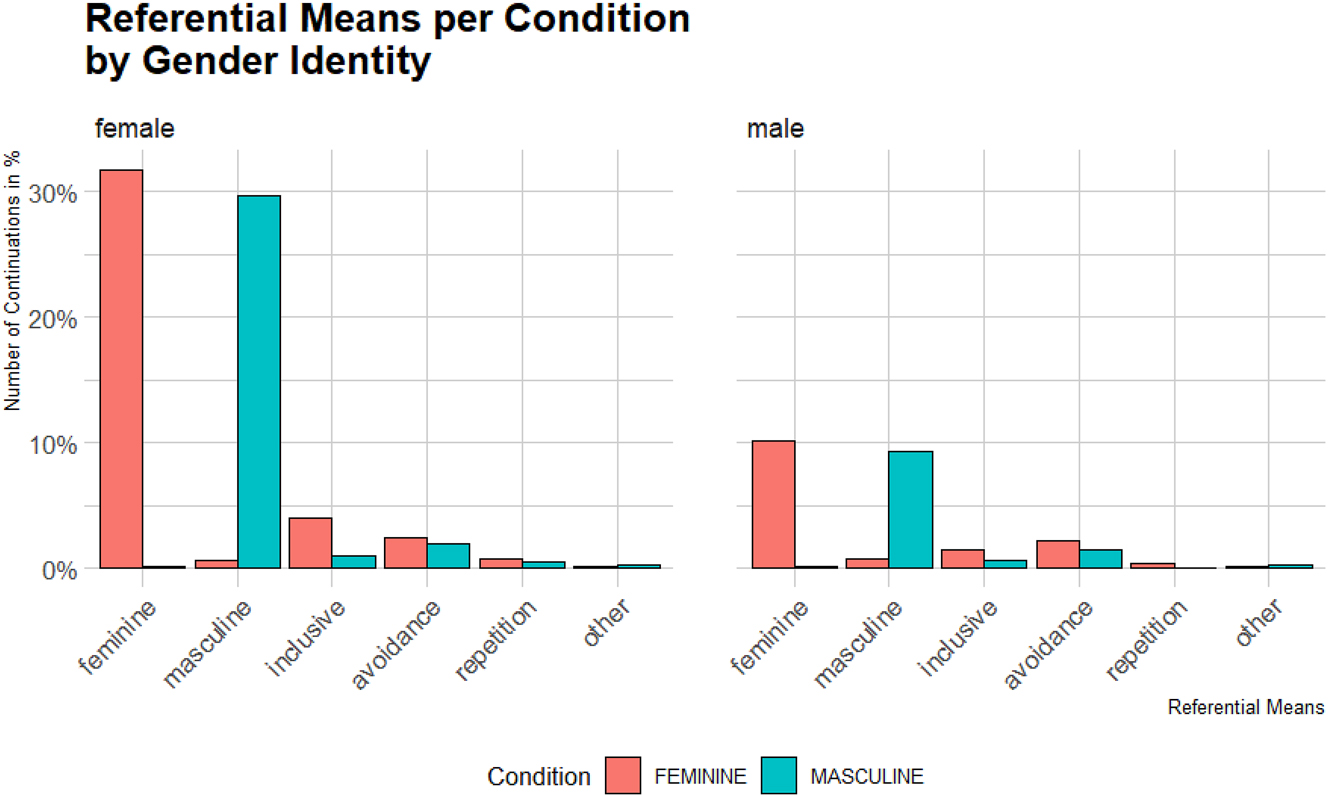

4.2.1 Gender identity

Overall, the proportional differences between gender identities were small, except for more cases of inclusive and fewer cases of avoiding references by the participants identifying as female compared with the participants identifying as male.[16] Split by condition, however, different choices of establishing reference emerged: Figure 3 illustrates that the female participants used the most feminine means of reference in the feminine condition (79.8 % versus 67 % produced by the male participants) in the extended cloze task when referring back to the introduced referent. In parallel, the female participants used slightly more masculine means of reference in the masculine condition (88.7 % versus 79.4 % produced by the male participants). Interestingly, the male participants tended to choose incongruent continuations of feminine noun forms with masculine pronouns more often than the female participants (albeit rare overall, 5.2 % vs 1.6 %).

Types of referential means used for feminine and masculine role and profession nouns by the participants’ gender identity for each condition.

The participants identifying as female mentioned slightly more inclusive means of reference in the feminine condition than their male peers (10.2 % vs 9.4 %), whereas the reverse was observed in the masculine condition, in which the participants identifying as male chose some more inclusive means of reference than their female peers (4.8 % vs 3 %). A clearer picture can be seen for cases in which referential means were avoided: in both conditions, the male participants circumvented establishing reference to a greater extent than the female participants (14.6 % in the feminine and 12.1 % in the masculine version were instances of avoidance among the participants with a male gender identity, while references were avoided by the female participants to 6.1 % in the feminine and 5.7 % in the masculine version). The referents were repeated slightly more frequently for the feminine epicene nouns by both gender identities (2 % by female ones and 2.8 % by male ones) than for their masculine counterparts. The participants identifying as male were more likely to choose means of reference subsumed as “other” than those identifying as female, but again, the latter two categories fall between only 0.4 % and 2.8 %.

The usage of the six types of referential means between the gender identities of the participants by condition and across conditions reached high significance in a chi-square test of association with the two-level factor gender as a layer (female: χ2(5) = 858, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.91), (male: χ2(5) = 247, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.81).

4.2.2 LGBT*QIA+ community affiliation

The numerical differences in the production of referential means between the participants that self-reported as adjacent to the LGBT*QIA+ community and those that did not are displayed in Figure 4. Even across conditions, variations in reference usage became apparent in overall more feminine means of reference used by the LGBT*QIA+ community-adjacent participants compared with non-adjacent participants, who relied on more masculine means of reference in total. Specifically, the community-adjacent participants used feminine referential means for feminine epicene nouns in 78.5 % of all instances, while the non-adjacent ones used these 69.2 % of feminine epicene nouns when completing the given sentence scenario. The non-adjacent participants referred to feminine role and profession nouns more often with the incongruent masculine form of reference (5.3 %) than the adjacent participants did (2.4 %).

Types of referential means used for the feminine and masculine role and profession nouns by the participants’ relation to the LGBT*QIA+ community for each condition.

A similar enhanced willingness to use masculine forms of reference among the participants not adjacent to the LGBT*QIA+ community was also observed in the masculine condition, in which they employed masculine (pro)nouns in 86.1 % of all their responses, compared with 84.6 % of responses from the LGBT*QIA+ adjacent people.

What is striking is the average usage of inclusive means: the non-adjacent language users were those who referred to the role or occupation nouns with inclusive forms of reference more often (18 % in the feminine condition and 5.5 % in the masculine conditions) than the community-adjacent language users (8.9 % of inclusive referential means in the feminine condition, 2.6 % in the masculine). It appears that first, even those individuals who are not members of, or close to, the LGBT*QIA+ community strive for linguistic inclusion; and secondly, that individuals who are part of, or in proximity to, this community may rely on different types of elements to refer to the presented referents. In fact, the number of responses in which reference was avoided altogether is higher for the community-adjacent participants (7.6 % in the feminine version and 9.6 in the masculine version) than for the non-adjacent ones (about 5.3 % in both conditions). The strategies of repetition or using other means of reference were equally less often found (between 0 and 2.3 %).

The differences in the use of the six types of referential means between the participants’ relationship to the LGBT*QIA+ community by condition and across conditions reached high significance in a chi-square test of association with the two-level factor community affiliation as a layer (adjacent: χ2(5) = 732, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.89; non-adjacent: χ2(5) = 245, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.86).

4.2.3 Age

The participants below the age of 34 (here termed “younger participants”) indicated a higher sensitivity to female visibility in the language and inclusion of referents, as shown by the greater extent of feminine means of reference they chose as well as their rejection of masculine forms as generic means of reference in the sentence continuation task (Figure 5). When the role and profession nouns were presented in the feminine version, the younger participants used feminine references on average 78.7 % of the time, while the figure for participants above the age of 34 (here termed “older participants”) was 72 %. For the older participants, the congruent continuations are closer to each other (79.6 % masculine references in the masculine condition). The younger participants, however, received the highest proportion of congruent, masculine forms of reference in the masculine condition (90.3 % and therefore more than 10 % stricter agreement than for epicene nouns in the feminine condition), which can be interpreted as a strong connection between masculine grammatical gender (mainly reflected in the -er suffix that can also denote male-specific referentiality) and masculine pronominalisation, which is demonstrably stronger than the grammatical agreement effect in any other condition and demographic aspect investigated. By implication, the masculine nouns received the fewest inclusive means of reference (3 % by the younger and 4.3 % by the older participants), whereas the feminine epicene nouns were referred back to with 9.6 % (younger participants) and 10.1 % (older ones) of inclusive referential means.

Types of referential means used for the feminine and masculine role and profession nouns by the participants’ age groups for each condition.

Moreover, the older participants avoided establishing reference (12.7 % in the feminine and 10.6 % in the masculine conditions) and repeating the noun form more often (3 % in both conditions) than the younger participants did, who avoided reference in the feminine in 6 % and in the masculine in 5.5 % of cases (the use of repetition being under 2 %).

The participants in the older age group used as many inclusive means of reference across conditions as the younger age group. The differences in the use of the six types of referential means between the age groups of the participants by condition and across conditions reached high significance in a chi-square test of association with the two-level factor age group as a layer (younger: χ2(5) = 747, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.90; older: χ2(5) = 365, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.85).

4.3 Discussion

What Motschenbacher (2014: 246) attests for languages without a strong masculine-feminine grammatical contrast like English can be extended to German as well (on top of grammatical constraints), namely the semantic base of the socio-cultural genders of personal nouns “may have repercussions in pronominalization” (Motschenbacher 2014: 246). Inclusive forms of establishing reference were used seldom overall, yet much more frequently when the feminine epicene forms denoted social roles and professions. In reverse, balanced pronouns or noun phrases rarely appeared with masculine nouns. However, the feminine noun forms also led to somewhat more instances of avoidance, where the participants refrained from establishing reference to the subject of a given sentence, and to more repetitions of the introduced noun, another strategy to circumvent reference based on the inferred referential gender. A task design that did not require responses to be dichotomised, which means that the participants were not forced to establish a gender-specific reference like the one presented here, was open to individual strategies by which we detected different forms of gender-fair language in actual usage. The motive for language users to (occasionally) prefer linguistic inclusion or circumvention of gender specification potentially lies in the epicene forms themselves: referential gender of a non-gender-specific noun can accommodate gender-neutral personal reference, because it grammatically avoids the “male-female macro-division” (Motschenbacher 2014: 248), and “does not further entrench gender binarism on the discursive level” (Motschenbacher 2014: 253) by grammatically backgrounding the gender category, i.e., backgrounding men just like women (for whom the specific forms could be used) while leaving space for identities beyond the binarism. Grammatically, the epicene personal nouns can accomplish this through not marking gender specificity of referents formally, thus employing fewer features indicating the referents’ socio-cultural genders (Betreuungsperson lit. ‘caretaking person [fem.]’ instead of Betreuer ‘caretaker [male/generic] [masc.]’ or Betreuerin ‘caretaker [fem.]’). Our assumption is supported by Scheller-Boltz (2020: 19) as far as the linguistic realisation of gender neutrality – and thus, gender-fairness – is achieved when a dichotomy and the traditional discrimination between specified binary features is avoided; one could say: deconstructed. Gender-neutral language can be seen as constructing a reality that admits an openness of gender identities in which more than female or male referents can be present, and in which male referents, unlike under “generic masculines”, are not overrepresented.

Formal agreement of personal pronouns has repeatedly been shown to be (i) the preferred strategy compared to other pronoun types, and (ii) even more pronounced when the linear distance[17] between a referent and its pronominal target is short, while semantic agreement with referential gender increases with distance (cf. Binanzer et al. 2022; Oelkers 1996; Thurmair 2006, in line with Corbett's (2006) Agreement Hierarchy). The syntactic distance between these elements in our design was at least n = 8 words (sentence item “carer/caregiver”, see Table A in the Appendix) and always extended the clause in which the referent was introduced to the continuation that required an anaphoric referential means to the continuation prompt. Since we cannot infer formal or gender-based agreement for the masculine nouns (in both cases, masculine referential forms like er ‘he’), the epicenes provide a useful case for an investigation. Agreement with grammatical gender was thus more likely to predominate, similar to what was observed by Binanzer et al. (2022) for the epicene “baby”, yet given their gender-indifferent denotation, they can also be open for semantic agreement (as they found for “child”). The impact of syntactic distance and domain would be worth controlling for in a follow-up study.

With respect to the methodological caveats, our study faces the constraints of controlled experimental settings, as these are necessarily more controlled than spontaneous, everyday language use in order to contrast conditions and isolate factors that potentially influence how reference to humans is established in German. A future research endeavour with much potential could therefore lie in corpus analyses of gender-fair pronouns referring to epicene nouns. At the same time, the present study is limited in gaining information about underlying cognitive processes and the costs to employ inclusive versus binary, grammatically congruent pronouns, which calls for time-sensitive elicitation of behavioural production data. In an adapted design, the role and profession nouns could be contextualised in gender-(non)specific contexts to account for the impact of gender stereotypes on discourse information (the more context provided, the weaker the grammatical gender impact on reference, see Klein 2022: 179). Finally, we acknowledge that some pairs are semantically deviant in their precise denotation, especially those formed with -hilfe ‘help’ as these result in assistant denotations. To test how formal versus gender-based agreement surfaces, they are appropriate nevertheless. What is left for future research is whether an epicene denoting a role or profession yields different effects (as was reported by De Backer and De Cuypere 2012). Although there are few masculine epicenes available in German, they await further scrutiny (see Klein 2022 for a survey on referential effects of Mensch ‘human’).

5 Conclusions

We have provided a detailed investigation of German feminine epicene nouns. We have shown that both socio-semantic (stereotypical) information of social role and profession nouns and their grammatical gender category are sources to construct referential gender. This study has illustrated how language-internal, language-external and individual factors interact with the motivation for grammatical gender agreement.

We have contrasted grammatically feminine social role and profession epicene nouns with their grammatically masculine counterparts. In doing so, we have found asymmetrical effects on reference production and interpretation of such nouns, depending on their grammatical gender as well as interactions of the choice of referential means with noun typicality. In these findings, our research validates the earlier work by Irmen and Roßberg (2004) showing that the grammatical gender effect in German substantiates the influence of gender typicality of a social role and profession noun.

Furthermore, our findings provide additional experimental evidence in support of the fundamental insights into the classification, function, and use of epicenes in Klein (2022). In this regard, we add gender-stereotypical information as one source of the gradient between gender-specific and epicene human nouns proposed by Klein (2022: 167).

Our subanalyses investigated the impact of various sociodemographic aspects on the findings. The contrasts of task performances on both the typicality ratings (see Schütze and Steriopolo forthcoming) and production revealed differential responses to gender-neutral expressions regarding feminine reference to epicenes, which peaked for the female and queer-community-adjacent participants, and masculine continuations that were most strictly used in correspondence to masculine nouns by the younger participants. This shows that when examining language, gender and sexuality empirically, the interrelation of grammatical, referential and social genders, these factors need to be taken into consideration. They can lead to tremendous variation within a German-speaking sample in terms of individual language behaviour and linguistic habits that vary in terms of using and interpreting gender-fair language.

Coreferential material of the gendered language forms was found to match with the respective direction of a masculine-male and feminine-female manifestation, such that the feminine epicenes were more prone to female typicality. Typicality information was adduced as an integral semantic path to referential interpretation and, by being channelled through a grammatically feminine or masculine form, yielded different effects such that grammatical features crucially led to asymmetric representations of referential gender, indicated with co-referring elements. Thus, compared with the masculine forms, the feminine epicenes yielded a higher proportion of inclusive means of reference, and may therefore mark gender-fair means in the German language.

The feminine epicenes that do not mark social gender cues overtly were therefore more open to innovative strategies of gender-fair (inclusive) reference, which – unlike their masculine counterparts – led to more frequent use of gender-equitable language. Despite comparable grammatical constraints on congruent referentiality, feminine social role and profession epicenes presented higher socio-cultural gender inclusivity compared with the masculine nouns. We therefore conclude that feminine epicene nouns can help overcome male and cis-normative biases and can thus be used as recommendations for future language conventions to achieve linguistic and cognitive gender-fairness in the German language. Finally, we propose to consider inclusive pronominalisation as a very recently emerging form of semantic agreement with a referent in German motivated by the striving for gender equality, as opposed to purely grammatical agreement, as gender conflicts are being effectively resolved with gender-overarching means of reference.

Our findings are of interest to sociolinguists, psycholinguists, cognitive linguists and German-language specialists, as well as anyone interested in the social and grammatical facets of gender. They are especially of interest to readers interested in the interrelated issues of gender, sexuality, linguistic diversity and language attitudes, and specifically in issues concerning the German-speaking community that strives to achieve meaningful gender equality. Since this study accounts for demographic variation regarding gender and sexuality, it contributes to the research fields of feminist, lavender and queer linguistics, as well as the research field of transgender studies.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all the participants in this experimental study and cordially thank three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their very helpful comments on this work.

-

Data availability: The data, metadata and stimulus item lists can be accessed in the repository: https://osf.io/8evms/.

A full list of stimulus sentences (in alphabetical order of nouns) and continuations.

| Sentence with masculine/(gender-neutral) feminine forms Translation |

Continuation Translation |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ein Ansprechpartner/Eine Ansprechperson sollte sämtliche Anliegen für sich behalten, also ganz besonders vertrauenswürdig sein. A reference person should keep all concerns to themselves, that is, be particularly trustworthy. |

Zum Beispiel sollte For instance, |

| 2 | Ein Betreuer/Eine Betreuungsperson muss im Miteinander sehr einfühlsam sein. A carer/caregiver (or supervisor) has to be very empathic when dealing with people. |

Beispielsweise muss For example, |

| 3 | Ein Büroangestellter/Eine Bürohilfe sollte idealerweise immer hilfsbereit und bei allen Tätigkeiten aufmerksam sein. An office employee/help should ideally be always helpful and attentive to all tasks. |

Außerdem sollte Furthermore, |

| 4 | Ein Haushälter/Eine Haushaltshilfe muss in höchstem Maße organisiert und verlässlich sein. A housekeeper/household help must be highly organised and reliable. |

Genauer gesagt muss More precisely, |

| 5 | Ein Kontakt/Eine Kontaktperson muss jederzeit, vor allem im Notfall, erreichbar sein. A contact/contact person needs to be available anytime, especially in case of an emergency. |

Unter anderem muss Among others, |

| 6 | Ein Laborant/Eine Laborkraft sollte bei der Durchführung von Experimenten und Versuchen stets gewissenhaft sein. A lab assistant should be careful at all times when carrying out experiments and tests. |

Zum Beispiel sollte For instance, |

| 7 | Ein Lehrer/Eine Lehrkraft sollte allen gegenüber weltoffen und tolerant sein. A teacher should be open-minded and tolerant towards everyone. |

Beispielsweise sollte For example, |

| 8 | Ein Pfleger/Eine Pflegekraft muss manchmal sehr bestimmt, dabei aber immer rücksichtsvoll sein. A carer worker has to be very decisive sometimes, but always be considerate at the same time. |

Unter anderem muss Among others, |

| 9 | Ein Rechtsanwaltsgehilfe/Eine Rechtsanwaltshilfe sollte bei jedem Fall wissbegierig und unterstützend sein. A lawyer’s clerk should be inquisitive and supportive in each case. |

Darüber hinaus sollte Moreover, |

| 10 | Ein Rettungshelfer/Eine Rettungskraft muss im Einsatz überdurchschnittlich belastbar sein. An ambulance or emergency worker must be outstandingly resilient on duty. |

Genauer gesagt muss More precisely, |

| 11 | Ein Reinigungsmitarbeiter/Eine Reinigungskraft wird in der Firma flexibel, häufig sogar kurzfristig, einsetzbar sein müssen. A cleaner will need to be requested flexibly, often even at short notice, by the company. |

Außerdem wird Furthermore, |

| 12 | Ein Saisonarbeiter/Eine Saisonkraft kann über mehrere Monate äußerst engagiert sein. A seasonal worker can be highly dedicated for several months. |

Darüber hinaus kann Moreover, |

| 13 | Ein Servicemitarbeiter/Eine Servicekraft sollte zu jeder Zeit erreichbar, kommunikativ und aufgeschlossen sein. A service employee should be available, communicative, and approachable at any time. |

Zum Beispiel sollte For instance, |

| 14 | Ein Sicherheitsdienst/Eine Sicherheitskraft muss sowohl verantwortungsbewusst als auch durchsetzungsfähig sein. A security service/guard has to be responsible as well as assertive. |

Beispielsweise muss For example, |

| 15 | Ein Teilzeitbeschäftigter/Eine Teilzeitkraft mit verringerter Arbeitszeit sollte dennoch motiviert und zielstrebig sein. A part-time employee/worker with reduced working hours should still be motivated and goal-oriented. |

Unter anderem sollte Among others, |

A full list of role and profession nouns (in alphabetical order) with percentages of referential means extracted after annotation from the sentence completion task and the received median rating values from the rating task (ranging from −100 to +100, with zero indexing balanced, negative numbers pointing to female typicality and positive numbers to male typicality).

| Item (in German) | English translation | Condition | Means of reference among responses (in %) | Typicality |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feminine | Masculine | Inclusive | Avoidance | Repetition | Other | Median rating value | ||||

| 1 | Ansprechperson Ansprechpartner |

‘reference person’ | Feminine | 62.3 | 9.43 | 9.43 | 15.1 | 1.89 | 1.89 | −20.0 |

| Masculine | 2.33 | 76.7 | 6.98 | 9.3 | 0 | 4.65 | −25.0 | |||

| 2 | Betreuungsperson Betreuer |

‘carer’/‘supervisor’ | Feminine | 81.5 | 3.7 | 5.56 | 7.41 | 1.85 | 0 | −55.0 |

| Masculine | 0 | 88.4 | 2.33 | 9.3 | 0 | 0 | −22.5 | |||

| 3 | Bürohilfe Büroangestellter |

‘office employee’ ‘office help’ |

Feminine | 80.4 | 0 | 15.7 | 1.96 | 1.96 | 0 | −50.0 |

| Masculine | 0 | 90.2 | 2.44 | 4.88 | 2.44 | 0 | −5.0 | |||

| 4 | Haushaltshilfe Haushälter |

‘housekeeper’ ‘household help’ |

Feminine | 74.5 | 1.82 | 9.09 | 7.27 | 7.27 | 0 | −77.5 |

| Masculine | 0 | 86 | 2.33 | 11.6 | 0 | 0 | −65.0 | |||

| 5 | Kontaktperson Kontakt |

‘contact’ ‘contact person’ |

Feminine | 82.4 | 0 | 7.84 | 9.8 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Masculine | 0 | 65 | 17.5 | 12.5 | 5 | 0 | −5.0 | |||

| 6 | Laborkraft Laborant |

‘laboratorian’ ‘lab assistant’ |

Feminine | 69.1 | 1.82 | 5.45 | 16.4 | 3.64 | 3.64 | 0.0 |

| Masculine | 0 | 76.7 | 2.33 | 20.9 | 0 | 0 | 25.0 | |||

| 7 | Lehrkraft Lehrer |

‘teacher’ | Feminine | 82.7 | 1.92 | 11.5 | 3.85 | 0 | 0 | −15.0 |

| Masculine | 0 | 88.4 | 2.33 | 6.98 | 2.33 | 0 | −20.0 | |||

| 8 | Pflegekraft Pfleger |

‘care worker’ | Feminine | 82 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 0 | −45.0 |

| Masculine | 2.44 | 82.9 | 0 | 12.2 | 0 | 2.44 | −45.0 | |||

| 9 | Rechtsanwalthilfe Rechtsanwaltsgehilfe |

‘paralegal’ | Feminine | 75.5 | 9.43 | 11.3 | 1.89 | 1.89 | 0 | −35.0 |

| Masculine | 2.38 | 92.9 | 2.38 | 2.38 | 0 | 0 | −17.5 | |||

| 10 | Reinigungskraft Reinigungsmitarbeiter |

‘cleaner’ | Feminine | 74.1 | 1.85 | 5.56 | 16.7 | 1.85 | 0 | −50.0 |

| Masculine | 2.33 | 90.7 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 0 | −50.0 | |||

| 11 | Rettungskraft Rettungshelfer |

‘ambulance/emergency worker’ | Feminine | 76.5 | 3.92 | 9.8 | 3.92 | 3.92 | 1.96 | 30.0 |

| Masculine | 0 | 92.9 | 0 | 4.76 | 2.38 | 0 | 40.0 | |||

| 12 | Saisonkraft Saisonarbeiter |

‘seasonal worker’ | Feminine | 74.5 | 0 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 1.96 | 0 | 20.0 |

| Masculine | 0 | 86 | 4.65 | 4.65 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 55.0 | |||

| 13 | Servicekraft Servicemitarbeiter |

‘service employee’ | Feminine | 84.6 | 0 | 13.5 | 1.92 | 0 | 0 | −17.5 |

| Masculine | 0 | 95.3 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 0 | 0 | −22.5 | |||

| 14 | Sicherheitskraft Sicherheitsdienst |

‘security service/guard’ | Feminine | 74.5 | 5.88 | 11.8 | 5.88 | 0 | 1.96 | 62.5 |