Abstract

This study explores Mandarin children’s competence with quantifier domain restriction. We present results from two experiments in which adults and four- to five-year old children evaluated two possible candidates for the domain selection associated with the distributive operator dou ‘all’ in Mandarin Chinese. In the first experiment, we investigated whether children and adults are capable of selecting an appropriate domain when two candidate NPs both appear inside dou’s quantification scope; i.e., both of the NPs c-command dou. In the second experiment, still two candidate NPs were presented, but one within dou’s scope and the other outside its scope. Our results indicate that four- to five-year-old children are capable of basic distributive computation associated with dou, but they may choose an NP that adults do not usually choose as the domain of dou, resulting in non-adult interpretations of distributive computation in certain cases. Based on the results, we propose that four- to five-year-old children are less certain about the domain restriction associated with dou-quantification. This proposal has important implications for the current debate on the acquisition of universal quantifiers, specifically, the problem of quantifier spreading. We explain children’s uncertainty about the domain restriction with a universal grammar-based statistical acquisition model.

1 Introduction

1.1 Problems with the acquisition of universal quantification

1.1.1 Quantifier spreading and the event quantification account

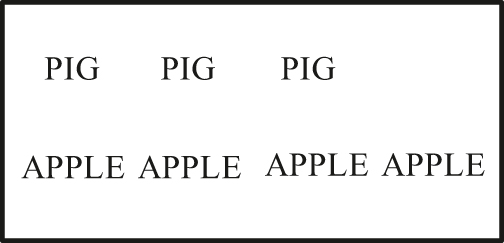

Studies on the acquisition of quantifiers have uncovered a puzzling phenomenon among 3- to 10-year-old children. For example, Philip (1995) presented adults and children with a picture depicting three pigs and four apples, where each pig is eating one apple, leaving one apple uneaten (in the picture there is also a dog eating a bone). When seeing this picture, almost all the adults said that (1) is a correct description of the scenario, because for adults the domain of the universal quantifier every includes only the subject NP pig, not the object NP apple.[1]

| Every pig is eating an apple. |

On the other hand, children between four and five years old judged (1) to be false. The children, pointing to the extra apple (which we will call the extra object), typically provided the following reason to justify their judgment: there is no pig eating the extra apple. In other words, they seemed to require an exhaustive pairing between the pigs and the apples.

What has led to such a non-adult response? Philip (1995) proposes that the exhaustive pairing is a result of a symmetrical interpretation as shown in (2),[2] where the quantifier every “spreads” its domain to the object NP. The exhaustive reading is thus also called quantifier spreading, which is also coined as symmetrical responses (cf. Inhelder and Piaget 1964; Roeper and Mattei 1975 for earlier studies on the topic).

| Every pig is eating an apple, and every apple is being eaten by a pig. |

The quantifier spreading problem leads to a question that interests many researchers: Are 4- to 5-year-old (and even older) children competent with universal quantification/distributive computation? According to Philip (1995), quantifier spreading is driven by a non-adult semantic representation of the universal quantifier. Philip argues that children may misunderstand every to be a universal quantifier that takes events, rather than individual objects, as its domain, as shown in (3).

| All minimal events in which either a pig or an apple (or both) is a participant are events in which a pig is eating an apple. |

In other words, for adults, every quantifies over only the NP it syntactically merges to, taking that NP and only that NP as its domain, but for children, every may take the whole event as its domain.

1.1.2 Problems of the event quantification account

Researchers have raised several concerns regarding Philip’s (1995) account. First, the dual-status of every, that is, every can both quantify over events or sets of individuals, causes a learnability problem. Since children still provide adult-like answers in addition to the symmetrical responses, we must assume that children can interpret every either as a determiner quantifier or as an adverbial event quantifier like always. Therefore, adults’ productions will always be consistent with one of the assumed interpretations that children assign, and so children will need to unlearn the event quantification interpretation (see examples 2 and 3 above) in the absence of negative evidence (Crain et al. 1996; Philip 2011).[3] We will return to this acquisition issue later in Section 3. Second, as pointed out by Crain et al. (1996), an important source of children’s symmetrical responses is the flawed experimental design, i.e., the presence of an extra object, e.g., the fourth apple in (1), in the pictures used in the experiments, which might give a hint that this extra object was relevant to the truth value judgment of the test sentence. In other words, a child who takes the extra object as pragmatically relevant for the judgment of the truth value of (1) will conclude that the correct and expected answer is “no.” In other words, a child may be attracted by the extra object, reasoning that (1) should be judged by taking the extra, uneaten apple into consideration. In this case, the child will simply choose the pragmatically felicitous response and violate a syntactic principle of quantifier domain restriction that is in conflict with an overriding pragmatic principle.

Crain et al. (1996) argue that Philip’s simple ‘yes/no’ task is a flawed experimental design because no alternative to assertions like (1) was provided. If (4a) and (4b) were both provided as possible outcomes of the story, Crain et al. (1996) predict that children would not be attracted by the extra objects. This is because if (4b) is instead the actual outcome, (4a) would be false. Therefore, the assertion in (4a) is in doubt at some point in the story. This satisfies the condition of plausible dissent (p. 116; see also Freeman et al. [1982]).

| Every pig is eating an apple. |

|

Some pigs, but not all, are eating an apple, and the rest are eating something else. |

In a series of experiments, Crain et al. (1996) argue that such a design flaw can be ameliorated by introducing both (4a) and (4b) as possible outcomes at certain point of the trail. Experiments conducted by Crain et al. (1996) validate this proposal, confirming that children do not have problems with universal quantification and distributive computation.

We agree that the pragmatic salience of the extra object might have attracted the subjects’ attention in Philip’s (1995) experiments, and in our experiments we will avoid such a design, but we argue that the effects of extra objects shed light on the nature of the problem of quantifier spreading. In addition, even though it is true that under certain conditions children’s symmetrical responses can be eliminated, we still lack a principled explanation for why, specifically under the single-extra-object condition, such a high percentage of non-adult symmetrical responses were observed (Minai et al. 2012; Philip 2004).

1.1.3 Salience effects and domain restriction problems

A number of other explanations for children’s symmetrical responses can be categorized as pure syntactic/semantic deficiency, or syntax-to-semantics mapping deficiency approaches (Brooks and Sekerina 2006; Roeper and de Villiers 1993; Roeper et al. 2011, 2005), in keeping with Philip (1995), assuming children’s symmetrical responses are due to their non-adult knowledge status regarding universal quantification or distributive computation. Still others advocate for pure pragmatic or cognitive deficiency approaches (de Koster et al. 2018; Gouro et al. 2001; Gualmini et al. 2003; Minai et al. 2012; Rakhlin 2007), which Crain et al. (1996) also argue for, suggesting that children do not have problems with universal quantification, but rather the observed non-adult behavior in universal quantification is caused by pragmatic factors inadvertently induced by the experimental design. Another popular string of proposals are combinatory approaches, the weak quantification hypothesis specifically, resorting to both syntactic/semantic and pragmatic factors (Drozd 2001, 2004; Drozd and van Loosbroek 2006; Drozd et al. 2017; Geurts 2003), i.e., children’s weak quantifier representation of every allows pragmatic factors to have an important influence on the interpretation of every.

Our review below will focus on a specific account of quantifier spreading, which leads to our study. Note that all the three strings of proposals mentioned above must explain why the domain of the universal quantifier can be extended to another NP. Both the syntactic/semantic deficiency approaches and the weak quantification approaches, for example, argue that children have a non-adult interpretation of universal quantifiers, whereas the pragmatic approaches do not have a principled account. We agree with the pragmatic/cognitive approaches that children may have no problems with universal quantification, and evidence from Mandarin Chinese will be provided below. However, the main difficulty for this approach is that a principled explanation, besides the flawed experimental design, should be provided to explain why quantifier spreading occurs (e.g., in extra-object conditions). If quantifier domain extension is altogether not allowed, pragmatic factors are quite unlikely to even have an opportunity to sneak in.

A specific pragmatic factor, salience effects, will be employed below to demonstrate that children must have non-adult domain restriction. Various recent studies converge on the conclusion that the extra object in studies such as Philip (1995) is significantly correlated with the emergence of quantifier spreading. We argue that extra objects can lead to quantifier spreading because the salience effects associated with the extra objects may affect the selection of the quantifier domain for strong quantifiers. Such salience effects are reported extensively in the literature.

On the one hand, increasing the salience of the target quantifier domain (the NP that every merges to) in adult grammar reduces the proportion of symmetrical responses significantly (Crain et al. 1996; Drozd and van Loosbroek 2006; Hollebrandse 2004).[4] If the target quantifier domain is brought to children’s attention or is introduced as a discourse topic before the presentation of the test sentence, the target domain will be more likely correctly selected. For example, Freeman et al. (1982) show that children’s responses may be affected by certain variation in the presentation of experimental stimuli. (see also Drozd [2001]). Freeman et al. find that, if a story is about cows, then children paid more attention to cows, and 89% of the participants required an exhaustive interpretation on cows; but when the story was about cowsheds that were burning down, 77% of the same children adopted a strategy that requires an exhaustive interpretation of cowsheds in the story context. In addition, Hollebrandse (2004) clearly shows that when the subject NP (the domain of the quantifier) is also the discourse topic, the symmetrical responses elicited by pictures with an extra object decreases significantly.

On the other hand, decreasing the salience of the extra object reduces symmetrical responses. Kiss and Zétényi (2017) replicated quantifier spreading in Hungarian five-year-olds with iconic drawings typical of previous studies on quantifier spreading. However, when replacing these iconic drawings with photos taken in a natural environment that are rich in accidental details, the occurrence of quantifier spreading was radically reduced. Kiss and Zétényi (2017) argue that in traditional pictures with one extra object, the extra object is taken as relevant to the judgment task, given Csibra and Gergely’s (2009) Natural Pedagogy theory (based on Sperber and Wilson’s [1995] Relevance Theory). An important effect alongside the distracting and noisy background in the pictures is that the extra object becomes less prominent and less relevant to the judgment of the test sentences. Therefore, it could be that the extra objects are less salient in the photos than in the iconic drawings (Gordon 1998), which might have led to a reduction of the symmetrical responses.

Similarly, Gouro et al. (2001) decreased the salience of the extra object with two design features. In one condition, Gouro et al. employed figures where the agents are of different types (e.g., different Pokemons) and the objects are of different colors (e.g., different colors of ponies that the Pokemons are riding). Therefore, both the agents and the objects are quite different from each other, and there are no extra objects that have a unique exceptional property. Gouro et al. argue that such a setting reduces the uniqueness and salience of the extra object, compared to Philips’ (1995) classical extra-object pictures, where the extra object stands out as a unique exception. In another condition, Gouro et al. included a context before the presentation of the traditional single extra object pictures, and in that context, they made the extra object less relevant to the truth value of the test sentence. For example, while the test sentence is about cats riding ponies, the context given before the presentation of the test sentence is not about riding but about whether the cats should get close to the ponies. In both conditions, the percentage of symmetrical responses dropped significantly.

In addition, Freeman (1985) shows that when the extra object is paired by an irrelevant, unmentioned agent, non-adult symmetrical responses are also significantly reduced, suggesting that the presence of this unmentioned agent lessens the salience of the extra object for the children (Drozd 2001), and therefore leads to more adult-like responses.

Lastly, increasing the number of the extra objects also decreases the salience of each of the extra objects and thus reduces quantifier spreading (Minai et al. 2012; Sugisaki and Isobe 2001). Sugisaki and Isobe (2001) included 6–7 extra objects in the testing pictures, and Minai et al. (2012) used three extra objects. Both studies find that with multiple extra objects, the percentage of symmetrical responses decreases significantly. Again, these are cases where the extra objects lose their uniqueness and become less salient than those in traditional single-extra-object pictures. Furthermore, Minai et al. (2012) find that when pictures depicting multiple extra objects were presented before pictures with a single extra object, the percentage of symmetrical responses was lower than when the single-extra-object pictures were presented first, indicating that some non-syntactic/semantic factors must have an effect on quantifier spreading. Minai et al.’s eye movement data also show that the mean proportion of eye fixation on the extra object(s) in the single-extra-object condition is much higher than that in the multiple-extra-object condition. Minai et al. (2012) thus suggest that with multiple extra objects, the extra objects lose their “uniqueness” status as in the single-extra-object condition, decreasing the salience of the extra object.

The multiple-extra-objects design may also have contributed to the decrease in the symmetrical response observed in Crain et al. (1996). The scenarios in Crain et al. (1996) typically involve more extra objects than those in Philip (1995). For instance, there are three extra objects in Experiment 4, and 2 extra objects (in addition to five other extra objects not mentioned in the test sentences) in Experiments 2, 3 and 5.

Of course, a formal theory of salience (in the visual domain as well as the linguistic domain) is needed in order to make a decisive evaluation. However, the evidence available seems to suggest that the salience of the extra object and the target domain of the quantifier has an important impact on the percentage of symmetrical responses obtained in previous studies. This leads to the question why the salience effects associated with extra objects directly influence the emergence of quantifier spreading. We argue below that this is because of children’s uncertainty of domain restriction in universal quantification.

1.2 Children’s uncertainty of domain restriction

As mentioned in the last section, the consistently observed salience effects indicate that a slight difference in domain selection may have caused children’s interpretation of universal quantification to be affected by the salient status of the domain or that of the extra objects in the experimental setting. It seems that the previous results can hardly fit into any of the existing theories of quantifier spreading. On the one hand, the pure syntactic/semantic deficiency and the combinatory approaches both need to assume that children start out with non-adult knowledge of universal quantification, so they both presuppose that children are not competent with universal quantification. On the other hand, the pragmatic approaches, without a significant modification, cannot account for the salience effects in a principled way. In order to capture the reviewed empirical phenomena, we will need to answer the following two questions:

| Are children competent with universal quantification? |

| Are children’s domain restriction different from adults’ in a way that can account for the various salience effects in children’s interpretation of universal quantification? |

In this paper, we will argue that, following the pragmatic approaches, children do have knowledge of universal quantification. We hypothesize that the salience effects in domain selection hinge on children’s uncertainty of domain restriction in a probabilistic sense[5]; that is, they are more uncertain than adults about restricting the quantifying domain only to NPs inside the quantifier’s scope.[6]

The uncertainty of domain restriction account has the very potential to answer the two questions in (5). Firstly, it assumes that children do not have problems with universal quantification itself. That is, children know that for universal quantification associated with a universal quantifier, a quantifier domain is needed, and the universal quantifier imposes universal force on the members of the domain. Secondly, since the uncertainty of domain restriction is formalized in a probabilistic sense, the grammar allows the selection of the domain to be affected by pragmatic factors. Therefore, the salience effects observed in previous studies can be explained: Since domain restriction such as the c-command requirement is violable, when a variable outside of the quantifier’s scope is salient, children may extend the domain to include that variable.

Upon this account, the question immediately arises: why should children be more uncertain about domain restriction than adults in the first place? We will answer this question in Section 3 and argue that this is a natural outcome of Yang’s (2000, 2002 language acquisition model.

1.3 Dou-quantification

In order to test the domain restriction account, we use data from Mandarin Chinese (Chinese hereafter) to investigate whether children behave differently from adults in domain restriction. We investigate four- to five-year-old children’s acquisition of the universal quantifier/distributive operator dou in Chinese, which is roughly corresponding to all or each in English.

Dou is usually considered a universal quantifier or a distributive operator (Chen 2008; Cheng 1995; Chiu 1993; Lee 1986; Lin 1996, 1998; Wu 1999; Zhang 1997). The syntax and semantics of dou elicits much debate, but most authors agree that dou is directly or indirectly associated with universal force/exhaustivity or distributivity (Cheng 2009; Giannakidou and Cheng 2006; Liu 2016, 2017, 2018; Tsai 2015; Xiang 2008; Xiang 2016a, 2016b).[7] We adopt the idea from Lin (1996, 1998 that dou is a distributive operator that carries universal force. However, for the sake of convenience, we sometimes still refer to dou as a universal quantifier as it brings universal force (but see ft. 7).

As a generalized distributive operator, dou introduces a tripartite structure, including the restrictor/domain,[8] the operator and the nuclear scope (Heim 1982; Lin 1998). For example, dou in sentence (6) derives a tripartite structure as shown in (7).

| Wugui | dou | [VP zhong-le | lanhua]. |

| tortoise | all | plant-ASP | orchid |

| ‘The tortoises all planted (an) orchid(s).’ | |||

| tortoise | dou | plant orchid |

| [domain] | D-operator | [nuclear scope/property] |

Dou distributes the property represented by the VP over every member of the domain, where “every member” indicates universal force. In order to be the domain of dou, an NP must c-command dou (Chiu 1993; Ke et al. 2018; Lin 1998; Zhang 1997).[9] In the case of (6), supposing that there are three tortoises in the context, each of the tortoises should have the property of planting an orchid, because only the subject NP wugui ‘tortoise’ c-commands dou and thus can be dou’s domain.

It can become more complicated when there are two eligible candidates for the domain within the scope of dou.[10] For instance, (8), which is a test sentence for Experiment 1 (Section 2.2), is a case where both the subject wugui ‘tortoise’ and the preposition object laoying ‘eagle’ (more accurately laoying-pangbian ‘eagle-loc’) c-command dou and thus are both in dou’s scope (see below a discussion of the dual-status of the preposition in Chinese).[11] In this case, it is important to know which NP will be selected as the domain of dou.

| A typical test sentence of Experiment 1 | |||||

| Wugui [PP/NP | zai | laoying-pangbian] | dou | zhong-le | lanhua. |

| tortoise | p | eagle-loc | all | plant-asp | orchid |

| ‘The tortoise(s) at the eagle(s) side all plant an orchid.’ | |||||

| If wugui ‘tortoise’ is selected as the domain: |

| ‘All of the tortoises planted an orchid besides the eagle(s).’ |

| If laoying-pangbian ‘eagle-loc’ is selected as the domain: |

| ‘Besides all of the eagles there is an orchid which is planted by the tortoise(s).’ |

As a fact, (8) is ambiguous (see the adult data in Experiment 1). Cheng (1995) argues that the ambiguity is due to the dual-status of the preposition in Chinese. Zai ‘at’ as a preposition can either project or not project.[12] When it projects as P and then PP, the NP complement of P does not c-command dou, and thus the NP is not in dou’s scope and cannot be dou’s domain. This syntactic possibility leads to meaning (9a), where only the subject NP wugui ‘tortoise’ is quantified by dou. However, if the preposition does not project and is vacuous, the NP c-commands dou and thus can be its domain. Based on the Principle of Economy of Derivation (Chomsky 1991), Cheng (1995) suggests that dou must quantify over only the closest NP inside its scope (“making the shortest move” in Cheng’s terms). That is, dou could distribute over only the NP laoying ‘eagle’ when the NP inside PP projects, resulting in meaning (9b).

Children and adults’ selection of domain from two candidates will be investigated further in the second experiment (Section 2.3), using test sentences such as (10). (10) includes two NPs: one NP, xiaodongwu-men ‘animals’ is inside dou’s scope, and the other, dianshi, chuang he bingxiang ‘TV, bed and refrigerator’ is outside dou’s scope. If the former NP is quantified by dou, meaning (11a) is obtained; if the latter NP is quantified, (11b).

| A typical test sentence of Experiment 2 | ||||||

| Xiaodongwu-men | dou | reng-diao-le | dianshi, | chuang, | he | bingxiang. |

| animal-plu | all | chuck-out-asp | TV | bed | and | refrigerator |

| If dou selects the subject NP ‘animals’ as the domain: |

| ‘All of the animals chucked out a TV, a bed and a refrigerator.’ |

| If dou selects the complex plural NP ‘TV, bed and refrigerator’ as the domain: |

| ‘The TV, the bed and the refrigerator are all chucked out by the animals.’ |

In adult grammar, dou can distribute over only the c-commanding subject NP xiaodongwu-men, which is within the scope of dou (Lee 1986; Li 1995; see also Ke et al. 2018). If dou quantifies over this NP, the corresponding logical form would be (12a), meaning “For every x, x an animal, x chucked out a TV, bed and refrigerator.” However, if our grammar allows dou to extend its scope to the whole sentence, and, as a result, to quantify over an NP that is outside of its normal scope, the compound NP dianshi, chuang, he bingxiang ‘TV, bed and refrigerator’ may be taken as the domain. In this case, meaning (12b) is derived, i.e., “For every x, x a TV, a bed or a refrigerator, animals chucked out x.” In other words, dou distributes the property animals chucked out something to every member of the domain TV, bed and refrigerator.

| ∀x [x ∈ [[animal]] → x chucked out [[TV, bed and refrigerator]]] |

| ∀x [x ∈ [[TV, bed, refrigerator]] → animals chucked out x] |

1.4 Children are competent with dou-quantification: previous studies

Studies investigating different aspects of children’s knowledge of dou show that children do have core knowledge of dou-quantification. Lee (1986) finds that children as young as four to five years old know the universal/exhaustive force of dou-quantification. For a sentence like (13), children were shown a picture of three pandas where all three pandas are sleeping (exhaustive), and another picture in which only two out of three pandas are sleeping (non-exhaustive). When asked to choose the picture best described by (13), children chose the exhaustive picture 91% of the time.

| Xiongmao | dou | shuijiao | le. |

| panda | all | sleep | ptcl |

| ‘Pandas all fell into sleep.’ | |||

Hsieh (2008) does a longitudinal study of her son’s production. She reports that dou emerged in the child’s production when he was two years old, consistent with Lee’s (1986) finding. In addition, from four years and two months, the child started to consistently use dou together with universally quantified expressions and wh-phrases, which may imply that this child understood that dou is obligatory a licenser in these cases.

Zhou and Crain (2011) further confirm that four- to five-year-old children give adult-like interpretation when dou quantifies over wh-phrases. The experimenter told subjects a story in which all of the three dogs in the context have climbed up a small tree, but only one of them has later climbed up a big tree. Then either a statement (14a) or a question (14b) was presented, and participants were asked to determine whether the sentence was a statement or a question.

| Shei | dou | meiyou | pa-shang | dashu. |

| who | all | not | climb-up | big-tree |

| ‘Everyone didn’t climb up the big tree.’ | ||||

| shei | meiyou | pa-shang | dashu? |

| who | not | climb-up | big-tree |

| ‘Who did not climb up the big tree?’ | |||

Participants were expected to respond with a true/false judgment when they hear a statement, and respond with an answer when they hear a question.

A crucial difference between these two sentences is that in (14a), dou quantifies over the wh-phrase shei ‘who’, which brings universal force to the wh-phrase’s interpretation. As a result, (14a) tends to be interpreted as a declarative statement. However, (14b), which does not include dou, must be interpreted as a question. The target sentences were produced with the same neutral intonation pattern in order to avoid the intonation effects on the interpretation of the test sentences.

Children, as well as adults, rejected sentence (14a) 95% of the time, and they provided correct answers such as “Two dogs didn’t.” to (14b) 96% of the time. Zhou and Crain (2011) conclude that children know that dou is a universal quantifier which can quantify over wh-phrases, enforcing an exhaustive interpretation. This is why when dou is absent, they identify the sentence correctly as a question rather than a statement.

Therefore, these studies confirm that four years old children know that dou carries universal force (exhaustivity), and dou can distribute over or act as a licenser for a wh-phrase or a universally quantified phrase. These results answer our first research question in (5a).

2 Experiments

In this section, we explore our second research question (5b) regarding children’s domain restriction in dou-quantification. We present data from two experiments, each including a pretest session and a main session.

2.1 Pretests

The pretests served both as a preliminary test on children’s knowledge of dou and as a practice for participants to become familiarized with the task. In the pretests, the experimenter assured that participants were engaged in the task. If a participant failed to answer the pretest items correctly, s/he was excluded from the data analysis. Among the children who did not provide correct answers, there were children who always answered “yes” or “no” to all sentences. These children were not included in the experiment.

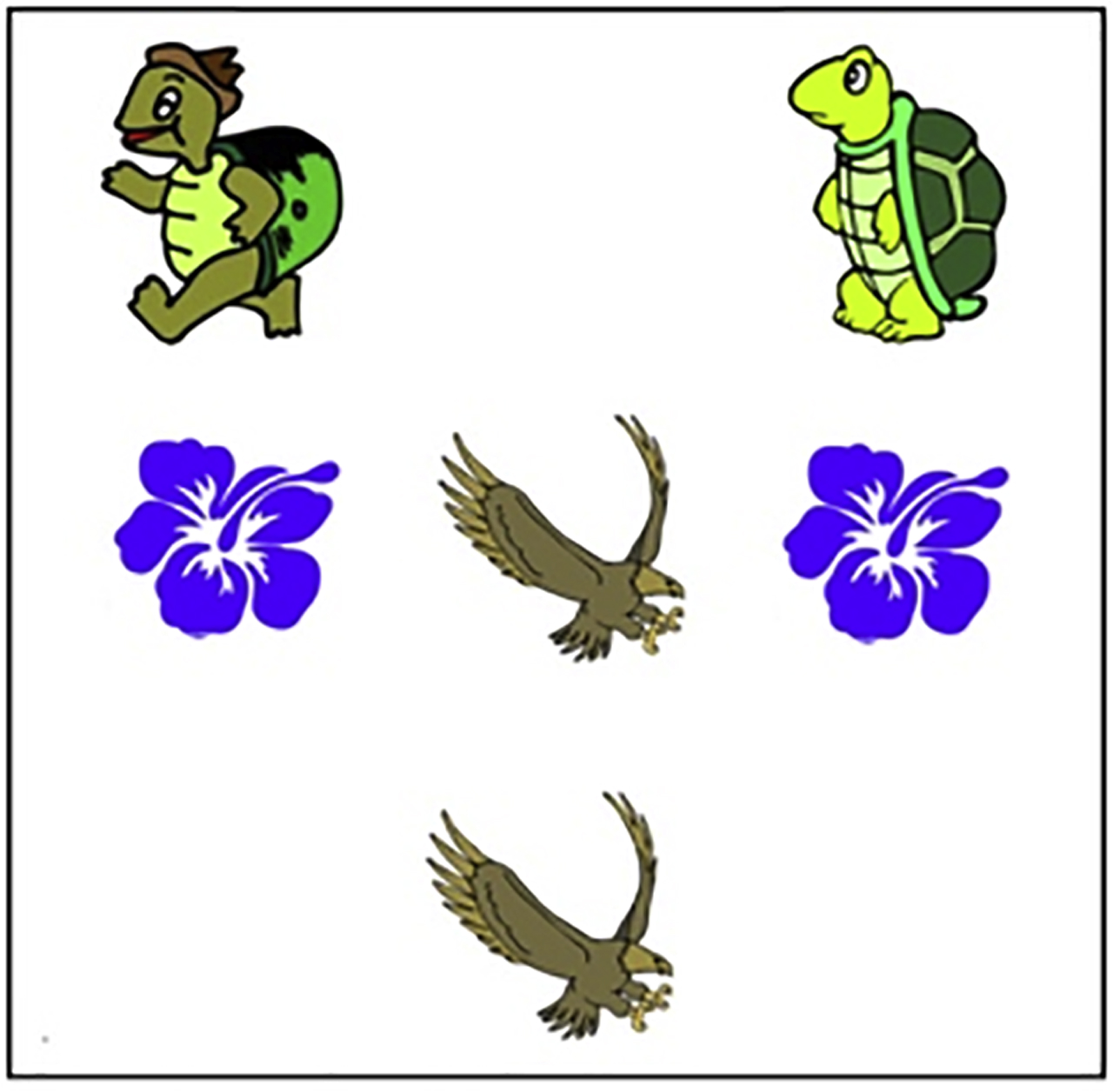

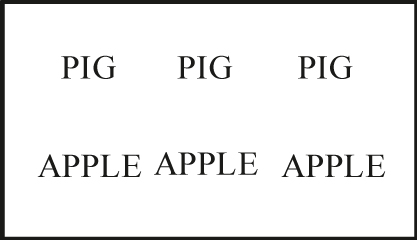

There were four pretest items in the first experiment (including two sentences with dou and the other two without dou) and one in the second experiment (a sentence with dou). Figure 1 shows a typical example of the pictures accompanying a simple introduction of the picture (“This story is about dogs who are looking for footballs.”), as well as an example of the target sentences (either one with dou or one without dou) (15) presented after Figure 1.

An example of the pictures of the pretests.

| Without dou: | Xiaogou | zhaodao-le | zuqiu. |

| dog | find-asp | football | |

| ‘The dog(s) found (a) football(s).’ | |||

| With dou: | Xiaogou | dou | zhaodao-le | zuqiu. |

| dog | all | found-asp | football | |

| ‘The dogs all found (a) football(s).’ | ||||

In the pretest for Experiment 1, participants were asked to judge whether sentences such as (15a) or (15b) were a good description of the story shown in Figure 1. Since the pretest sentences for Experiment 1 were of two types, i.e., with dou and without dou, we can identify children’s interpretation of dou by comparing their responses to these pretest items. In the second experiment, we included only a sentence with dou, because we were already sure that children answer “yes” to sentences without dou under the context as in Figure 1.

Note that bare nouns in Chinese can be used independently without a plural suffix, so the bare noun xiaogou ‘dog’ in sentence (15a) can refer to either a single dog or many dogs. However, when the NP is quantified by dou as in (15b), it must refer to all the dogs in the context, that is, the two dogs in Figure 1. The disappearance of the singular interpretation of the bare noun can thus be used as a diagnostic for dou-quantification. In other words, if participants know that dou is a universal quantifier, then they are expected to take (15b) as a false description of the story, whereas the singular interpretation of the bare noun in (15a) makes this sentence a true statement under the context in Figure 1 (interested readers are referred to Ke et al. [2018] for a full justification of this method).

Results of the pretests show that four-year-old children judged (15a), the sentence without dou, as a correct statement 91.7% of the time, while they rejected (15b), the sentence with dou, 100% of the time.[13] This is similar to adults, who accepted the sentences without dou up to 87%,[14] and rejected those with dou 100% of the time. We thus conclude that four- to five-year-old children know that dou is a universal quantifier or a distributive operator carrying universal force.

In summary, the results of our pretests confirm the answer to our first question, consistent with the results in Lee (1986), Hsieh (2008) and Zhou and Crain (2011): children have acquired dou-quantification by four years old. We conclude that four- to five-year-old children do not have problems with the core operation in dou-quantification or distributive computation. However, the target sentences in the pretests are very simple, since each sentence includes only one plural NP as a candidate for the domain of dou. In the main test session, we want to see whether children’s domain selection is the same as adults’ when there are two potential candidates available for dou’s domain.

2.2 Main test: Experiment 1

We now present data from two experiments to answer our second research question in (5b): what are the reasons that could explain children’s failure in distributive computation in some conditions? Both of the two experiments use sentences containing two candidates for domain selection in dou-quantification. The crucial difference is that in the first experiment, both of the candidates are within the scope of dou; whereas in the second experiment, one candidate is in dou’s scope and the other is not.

Experiment 1 explores children’s selection of domain when there are two NPs available within dou’s scope and tests if children extend the quantifier domain to include both NPs, both of which occur to dou’s left and c-commanding dou (see Section 1.3 for a discussion on the syntactic status of prepositions in Chinese).

2.2.1 Methodology

2.2.1.1 Participants

Twenty-five monolingual Chinese-speaking children (mean age: 4 years and 10 months; ranged from 4;1 to 5;3) participated in this experiment. Participants were recruited from a kindergarten in Beijing. In addition, forty-one adults were recruited from a university in Beijing to participate in the experiment. The data of one child and five adult participants were excluded from our analysis, because they rejected the two filler items without dou. The exclusion of these participants is to ensure, ideally, that the rest of the subjects can endure the ambiguity of the test sentences and will say “yes” to the sentences as long as one of the meanings of the sentences is consistent with the story.

2.2.1.2 Procedure

For children, we used a variant of the Truth Value Judgment Task (Crain and Thornton 1998). The task involved two experimenters. One acted out stories using pictures, and the other played the role of a puppet who watched the stories alongside the participant. After each story, the puppet would tell the participant what he thought had happened in the story using a test sentence. Participants’ task was to judge whether the puppet was correct. A between-subject design was employed for the child group to limit the experiment to 45 min: they were divided into two groups, and each group received stimuli from one of the two conditions (see Section 2.2.1.3 for details). For adults, we used a questionnaire that included materials of both conditions. The adult participants filled out the questionnaires independently.

2.2.1.3 Materials

Our first experiment included 12 target trials and 12 fillers. A typical test sentence is given in (16), as we have already discussed in (8), in which there are two NPs to the left of dou and c-commanding dou: wugui ‘tortoise’ and laoying ‘eagle’.[15]

| Wugui | zai | laoying-pangbian | dou | zhong-le | lanhua. |

| tortoise | p | eagle-loc | all | plant-asp | orchid |

| ‘The tortoise(s) at the eagle(s) side all planted orchid(s).’ | |||||

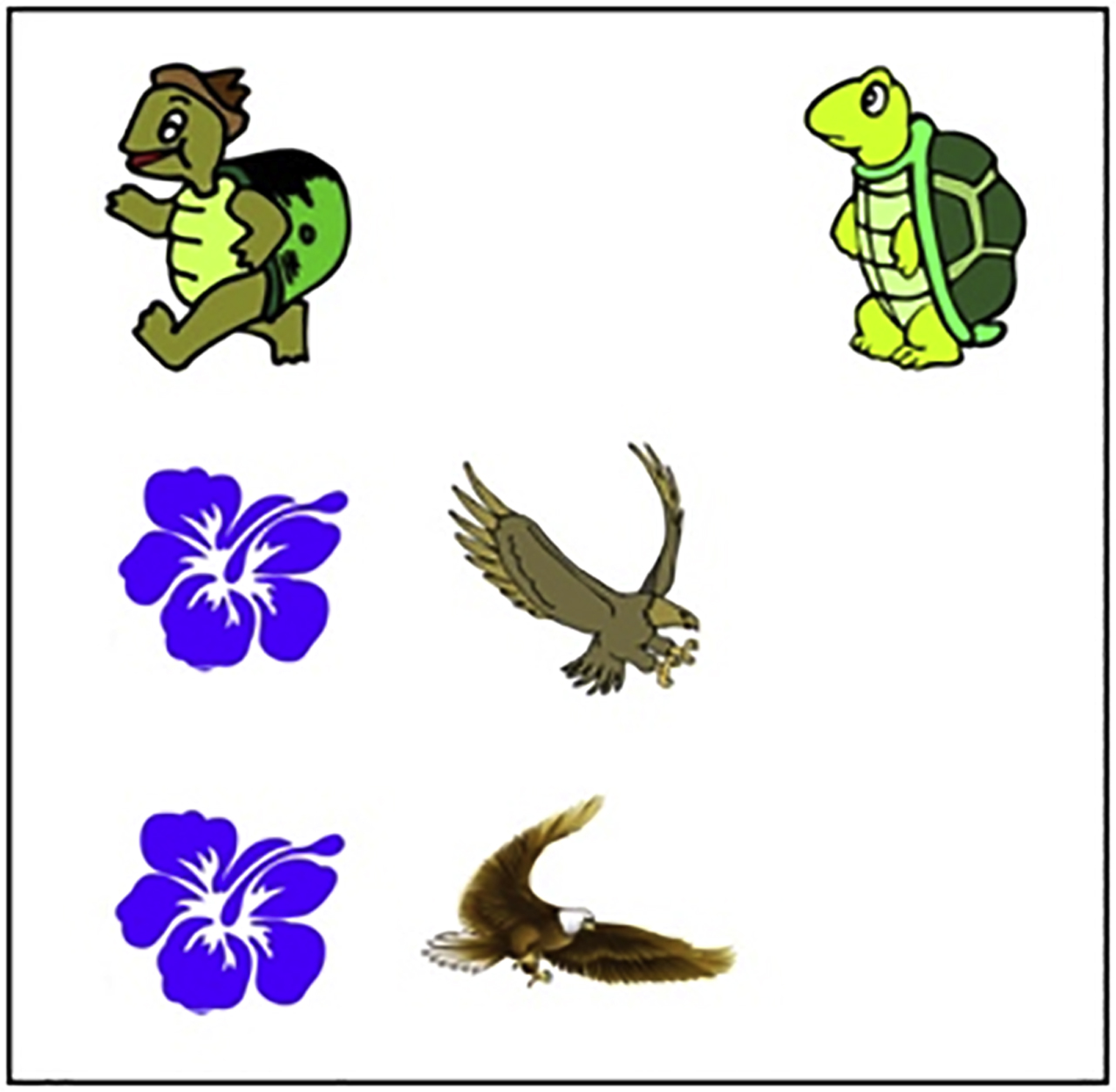

Either NP can be the domain of dou. The test sentence was presented following a scenario depicted either as in Figure 2 under the Subject Condition (six items; corresponding to the reading in which dou quantifies over the subject NP wugui ‘tortoise’) or as in Figure 3 under the Preposition Object Condition (six items; corresponding to the reading in which dou distributes over the object of the preposition, laoying ‘eagle’). The size of characters (drawings of either human or animals) was kept as similar to each other as possible. The position of the objects (the orchids in Figures 2 and 3) is counterbalanced across items.

Subject condition.

Preposition object condition.

The story associated with Figure 2 is as in (17).

| Here are two tortoises and two eagles. The tortoises want to plant orchids beside the eagles. Look, at the side of this eagle (pointing to one of the eagles) there is an orchid. Who planted it? Is it this tortoise or that tortoise (pointing to both tortoises)? Yes, it is the tortoise on the left that planted it. What about the other orchid? Hmm, it is also planted by the tortoise on the left. You see, the tortoise on the right (pointing to the tortoise on the right side) didn’t plant any orchid. |

A story with the same pattern was presented when Figure 3 was shown to the participants.

Note that when presenting the test sentences, we put the prosodic stress on dou, and left the two NPs un-emphasized, in order to avoid an influence from the emphasis pattern on domain selection.

Fillers were created to ascertain if children pay attention to the test. The fillers were designed such that half would be answered “yes,” and the other half “no.” The results of the fillers can shed light on the participants’ understanding of dou-quantification over the subject NP or the preposition object. The fillers were of two types; either only the subject NP is available to be quantified by dou (18a), or only the NP complement of the PP is available (18b).

| Wugui | dou | zhong-le | lanhua. |

| tortoise | all | plant-asp | orchid |

| ‘The tortoises all planted an orchid.’ | |||

| Laoying-pangbian | dou | zhong-le | lanhua. |

| eagle-loc | all | plant-asp | orchid |

| ‘Besides all the eagle(s) there is an orchid planted.’ | |||

2.2.2 Results

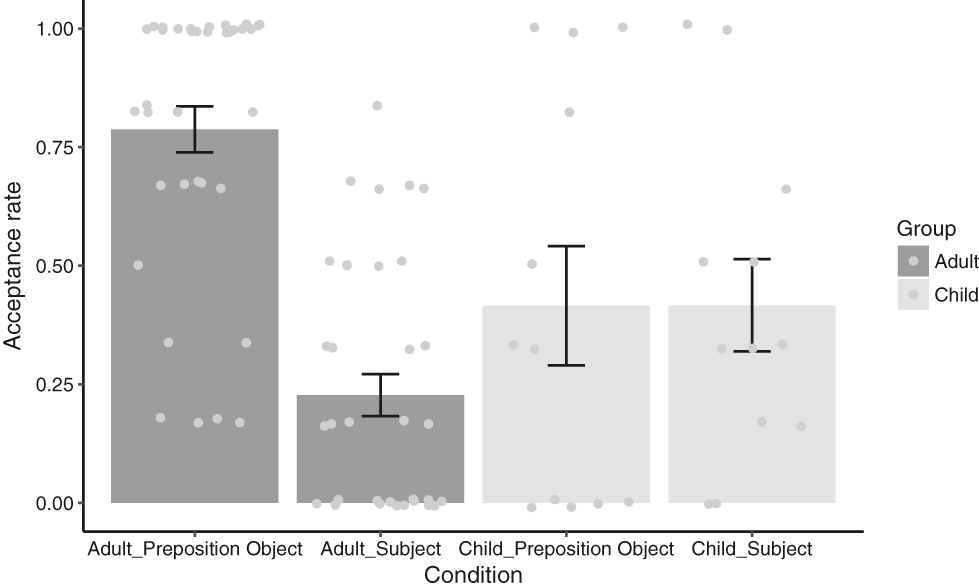

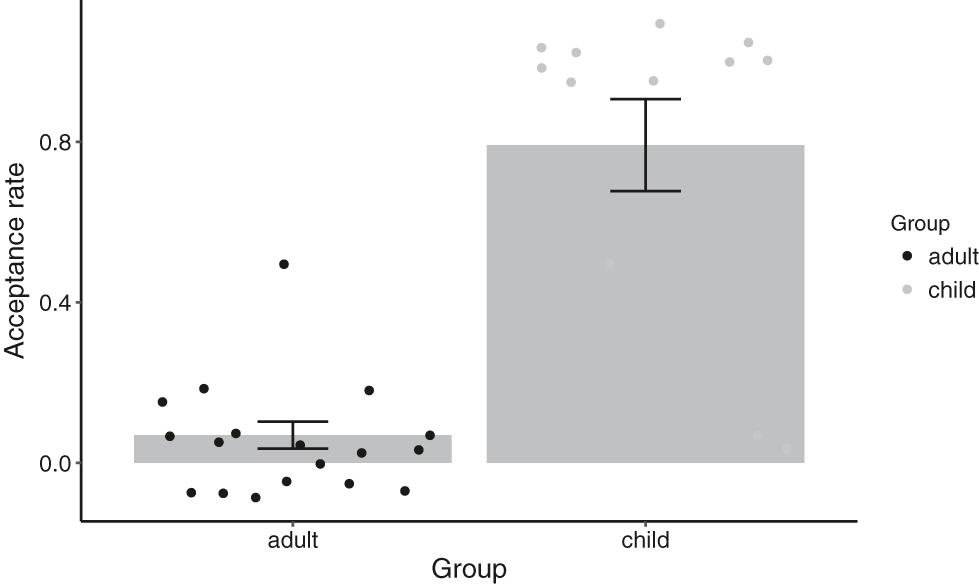

The results of the 36 adults and 24 children (12 for the Subject Condition and 12 for the Preposition Object Condition) were included in the data analysis. The results are presented in Figure 4.

Adults’ and children’s acceptance rates of the test sentences in Experiment 1 (error bars are standard errors; the dots represent the average acceptance rates of each participant).

As shown in Figure 4, adults prevailingly accepted the test sentences in the Preposition Object Condition at a rate of 79%, whereas they accepted the test sentences in the Subject Condition at a rate of only 23%. Note that these numbers are from two separate conditions and thus they both suggest that adults may prefer to take the preposition object as the domain of dou. A Pearson’s Chi-squared test reveals that the difference between the acceptance rates under the two conditions reaches statistical significance at α = 0.05, with X 2 (1, 432) = 133.36, p < 0.001. The statistical test confirms that adults have a preference to choose the NP object of the preposition instead of the subject NP as dou’s domain. However, children do not have such a preference, since the acceptance rates of the test sentences under both conditions are 42%.[16]

A closer examination of the individual results (the dots in Figure 4) underpins the idea that adults have a strong preference to select the object of the preposition as the domain of dou, whereas children do not have such a preference; on the contrary, there seem to be more children that were reluctant to take the preposition object than the subject as the domain. Five children rejected all the test sentences under the Preposition Object Condition, whereas only two children rejected all test sentences under the Subject Condition. In addition, there was much variation across individuals, which suggests that their selection of domain may be based on a probabilistic mechanism, which will be discussed in detail in Section 3.

2.2.3 Discussion

Our results confirm Cheng’s (1995) proposal regarding adults’ grammar that either the subject NP or the object of the preposition can be the domain of dou. However, it is not predicted that the object of the preposition is taken as the domain most of the time. These results suggest that dou is not a strict unselective universal quantifier (Lee 1986; Lewis 1975) that must quantify over all free variables in its scope. Indeed, if dou is a strict unselective universal quantifier, then we would expect dou to quantify over both bare nouns simultaneously. The adults would therefore have rejected the test sentences in both conditions. On the contrary, it turned out that adults could accept the test sentences in either the Subject Condition or the Preposition Object Condition, although the object of the preposition is the preferred domain (see Ke et al. [2018] for another piece of evidence showing that dou cannot be a strict unselective universal quantifier).

A similar conclusion can be drawn for the child participants: children do not require dou to quantify over all NPs in its scope. If children require dou to quantify over both NPs in the test sentences, they would always reject the test sentences under both conditions, which is rarely observed, as indicated by the individual data especially under the Subject Condition in Figure 4; namely, only two child participants completely rejected the test sentences.

The question immediately arises as to why adults prefer to take the object of the preposition rather than the subject as the domain of dou. One important reason may be that the object of the preposition is linearly and structurally closer to dou than the subject. As we have seen in the literature review, domain selection is influenced by various salience effects. The object of the preposition may thus be more salient than the subject NP because of being linearly and structurally closer to dou; that is, the path between the preposition object NP node and dou is shorter than the path between the subject NP and dou (Cheng 1995; Lee 1986; Pesetsky 1982). However, this explanation has to assume that children, on the other hand, are not sensitive to structural locality.

Another possible explanation is that adults may employ pragmatic reasoning based on the distribution of cases of dou-quantification. That is, when dou is located immediately after the subject NP as in (19), it unambiguously quantifies over the subject NP.

| Wugui | dou | zai | laoying-pangbian | zhong-le | lanhua. |

| tortoise | all | p | eagle-loc | plant-asp | orchid |

| ‘The tortoises all planted orchids beside the eagle(s).’ | |||||

Therefore, adults may perceive dou’s being located immediately after the PP as a pragmatic clue implying that dou is meant to quantify over the preposition object. In other words, the adult participants may reason: if the speaker’s intention were to have dou quantify over the subject NP specifically, why did the speaker use an ambiguous construction instead of the unambiguous one as exemplified in (19)? Child participants, on the other hand, may lack this kind of pragmatic reasoning which is based on the linguistic distribution of competing constructions.

Children accepted the test sentences under both conditions 42% of the time. These results can be interpreted in two different ways. One interpretation may be that children answer the questions randomly, and perhaps do not understand the test sentences at all. However, this interpretation seems quite unlikely. We want to highlight below several reasons why we do not believe that the children’s responses were based on random guesses, with a lack of understanding the meaning of the universal quantifier dou or even that of the whole test sentences. On the contrary, we believe that the children might “randomly” select an NP from the two NP candidates with a proper understanding of both the meaning of dou and that of the whole test sentences.

Importantly, the children provided adult-like justifications to support their “no” responses to test sentences. For example, when providing a reason why the test sentence (16) is false with regard to the story under the Preposition Object Condition, the children typically said “No, just one of the two tortoises planted an orchid,” which is a clear indication that they really understood the story and the test sentence and did not respond by guessing. If they did not understand the meaning of dou or the meaning of the whole test sentences, such right-to-the-point answers are surprising.

In addition, the children displayed adult-like competence in filler items such as those in (18) with a correct rate of 95%. These filler sentences also involve dou-quantification, and therefore the adult-like responses to these sentences strongly indicate that the children understood the meaning of dou and also took dou into consideration when judging the truth value of these sentences.

Furthermore, we only included in analysis the children who understood the universal force carried by dou in our pretest (Section 2.1). That is, those children who did not distinguish a sentence with dou from one without dou have already been excluded from the analysis.

Lastly, various previous studies on dou have showed that children understand the semantics of dou-quantification (Hsieh 2008; Lee 1986; Zhou and Crain 2011), as we have reviewed in Section 1.4.

An alternative interpretation, which we believe is much more plausible, is that it was not easy for child participants to select a proper NP as the domain of dou in the test sentences. These two NPs are syntactically close to each other, and since both of them are available to be the domain of dou, children are predicted to experience much interference when computing the domain of dou. Such competition effect is discussed in Kurtzman and MacDonald (1993) and Paterson et al. (2008). Basically, if a sentence is ambiguous, one of the interpretations would decrease the acceptability degree of the other. According to the cue-based retrieval model (Van Dyke and McElree 2006; Lewis and Vasishth 2005; Lewis et al. 2006), competitors sharing features with the target will induce similarity-based interference in memory retrieval. In the case of our test sentences, when dou is encountered, the parser needs to retrieve its domain. Either one of the NPs can be retrieved because they share almost all features, giving rise to severe interference effects. In other words, when children consider one of the NPs as the domain, another NP is also considered a competing domain. Consequently, it appears that children randomly picked one of the NPs as the domain. Different from children, adults may be affected by the similarity-based interference to a less extent, probably because adults’ memory retrieval is less noisy. This conjuncture is supported by a recent study showing that children were temporarily more distracted than adults when multiple retrieval cues supported a prominent competitor antecedent in the processing of reflexive binding (Clackson et al. 2011).

In order to further investigate children’s strategy in domain restriction, another experiment was conducted in which the two plural NPs, the subject and the object, are separated, with the subject placed inside the scope of dou and the object outside. We expect, when the two candidates are separated, the similarity-based interference discussed above can be reduced, and so we may see a cleaner picture.

2.3 Experiment 2

The second experiment was designed to investigate adults and children’s selection of the domain of dou, and to test whether children will extend the domain of dou to the non-c-commanding object NP.

2.3.1 Methodology

2.3.1.1 Procedure

Again, we used a variant of the Truth Value Judgment Task and the procedure is the same as that of Experiment 1.

2.3.1.2 Participants

We tested 13 children at a kindergarten in Beijing. Results from one child was excluded from the statistical analysis because this child did not reject the non-exhaustive reading of the sentence with dou in the pretest (see Section 2.1 for an introduction of the pretest items). The results from the rest of the children (n = 12, mean age = 4 years and 11 months, ranged from 4;7 to 5;1) were analyzed. 18 adults, all postgraduate students recruited from a university in Beijing, served as controls, independently taking questionnaires with the same materials.

2.3.1.3 Materials

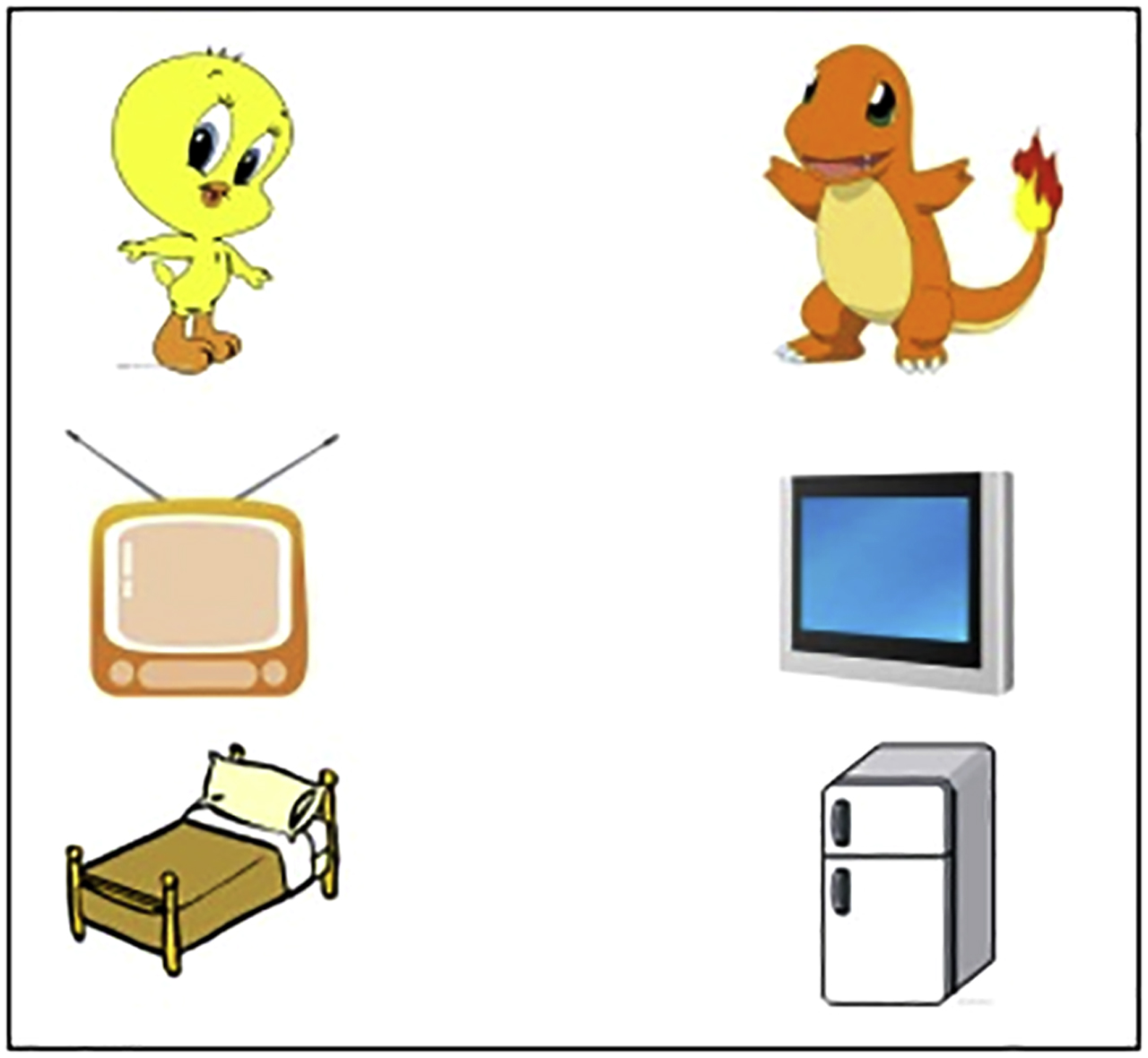

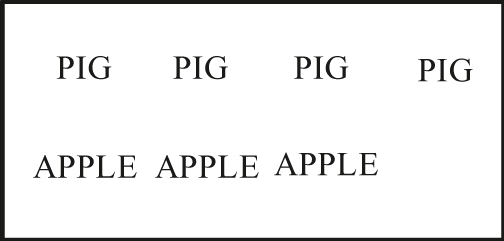

Each subject received one pretest, four test items and four fillers. Pretests used a sentence with dou. A typical example of the test sentences, as well as the pictures accompanying the stories, can be found in Figure 5 and sentence (20).[17]

A typical context of Experiment 2.

| Xiaodongwu-men | dou | rengdiao-le | dianshi, | chuang, | he | bingxiang. |

| animal-plu | all | chucked-out-asp | TV | bed | and | refrigerator |

| ‘The animals all chucked (a) TV, bed and refrigerator out.’ | ||||||

The test sentence (20) was presented following a story corresponding to Figure 5, in which one animal (the Tweety Bird) chucked out a TV and a bed, and the other (the dinosaur) a TV and a refrigerator. As we have mentioned, in adult grammar, dou must distribute over only the NPs that c-command it. In (20), dou should distribute over only the subject NP xiaodongwu-men ‘animals’ which c-commands dou. This leads to the reading in (12a), repeated below in (21). According to the story presented with Figure 5, (21) is false, because the only thing that both animals chucked out is the TVs.

| ∀x [x ∈ [[animals]] → x chucks out (a) [[TV, bed, and refrigerator]]] |

The scenario where both the animals chucked out the same kind of things is to provide a strong reason for participants who have acquired the adult grammar of dou-quantification to reject the test sentences. This is because for participants who can access the adult grammar and thus take only the subject NP as dou’s domain, the correct statement must instead be ‘The animals all chucked a TV.’ Such a design satisfies the condition of plausible dissent, which is a crucial design feature of the Truth Value Judgment Task (Crain and Thornton 1998).

On the other hand, the conjunct object NP dianshi, chuang, he bingxiang ‘TV, bed, and refrigerator,’ which does not c-command dou, is impossible to be the domain of dou in the adult grammar. This is a good case for us to test whether children can extend the domain of dou to an NP that does not c-command dou, different from adults. The prediction is that if dou distributes over the conjunct object NP in (20), the derived interpretation will be “For the TV, bed, and refrigerator, they are all chucked out by the animals,” as is translated in (12b), repeated below in (22). According to the story presented with Figure 5, (22) is true.

| ∀x [x ∈ [[TV-bed-and-refrigerator]] → animals chuck-out x] |

In addition to the test trials, each subject saw four fillers. Fillers were designed to verify whether children paid attention to the tasks by asking them simple questions about the stories. Furthermore, we used fillers to diversify the statement patterns, in order to conceal the purpose and the inherent pattern of the target trials. For instance, given the context such as Figure 5, a filler would be Xiaoniao rengdiao-le dianshi, dui haishi budui? ‘The Tweety Bird chucked out a TV, true or false?’ Children were expected to give a Yes–No answer.

2.3.2 Results

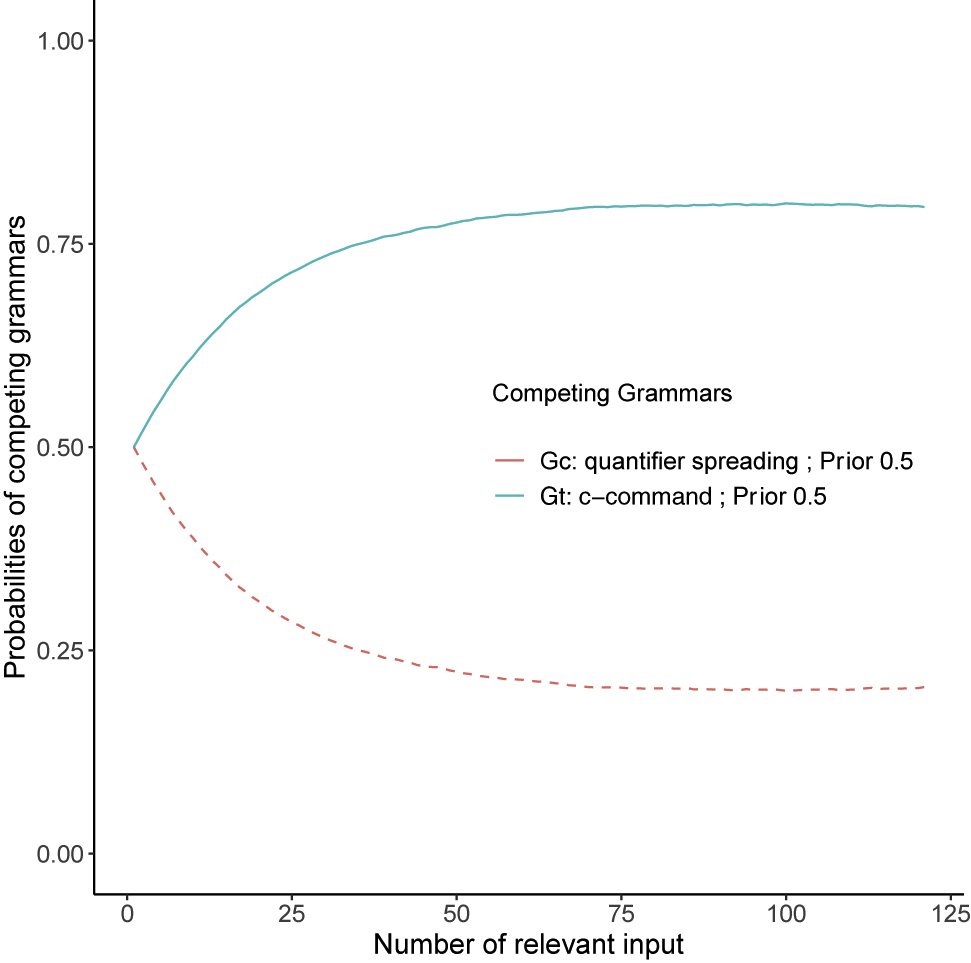

All the subjects, including adults and children, accepted or rejected the filler items at an accuracy rate of 100%, so all the data were included in the analysis. The findings shown in Figure 6 are that children accepted the test sentences 79% of the time and rejected them only 21% of the time.

Acceptance rates of the test sentences of children and adults in Experiment 2 (error bars are standard errors; the dots represent the average acceptance rates of each participant).

The reasons provided by children show that they rejected the test sentences because they assigned the subject NP as the domain of dou. In contrast, adults overwhelmingly rejected the test sentence by 93%. We performed a Pearson’s Chi-squared test in R (R Core Team 2014), which shows that children accepted the test sentences much more often than adults, with X 2 (1, 121) = 62.23, p < 0.001.

2.3.3 Discussion

The fact that almost all of the adults rejected the target sentences shows their firm compliance with the c-command requirement as a domain restriction for dou-quantification. Adults were reluctant to select the domain from the NPs outside the scope of dou. On the other hand, four- to five-year-old children showed great uncertainty of domain restriction concerning distributive computation, because they can take an NP that is outside of the scope of dou as the domain of dou.[18] Individual results further reveal that 9 out of the 12 children accepted all test items, whereas only 2 of the 12 rejected all test items, probably signaling individual differences in the acquisition of the domain restriction associated with dou-quantification.

These results support the idea that children are more uncertain than adults about the domain restriction associated with the distributive operator dou. When more than one bare NP is present, it is possible for children to take either of them to be the domain of dou, even in cases when an NP is outside the syntactic scope of dou.

These results also shed light on the problem raised in the first experiment. It was the syntactic closeness and similarities between the two NPs that might have caused severe interference effects in domain selection to children, resulting in difficulties to identify a proper domain. Therefore, when the two NPs were separated and these interference effects were reduced, children could easily select the NP that is outside of the scope of dou as its domain. There were two children overwhelmingly rejected the test sentences, suggesting that some children considered it obligatory to take the c-commanding subject NP as the domain. Therefore, the acceptance and rejection data together indicate that children can take either the subject or the object NP as the domain of dou.

Given that children are rather uncertain about the domain restriction of dou-quantification, there must be reasons why they biased toward the object NP, as we did not detect such a preference in Experiment 1. A readily available potential factor is that the object NP is a complex NP, which may be more salient than the subject NP, resonating with the salience effects observed in previous studies. This point can be tested further with an experiment where the number of the NPs inside the conjunct NP is reduced, to see if the acceptance rate of the object complex NP would decrease. We leave this to future studies.

3 General discussion

The results of the first experiment reveal that adults show a preference to take the object of the preposition as the domain of dou, compared to the subject NP, possibly due to pragmatic cues with regard to competing dou-constructions. Children, on the other hand, do not have such a preference. Children thus are rather free to choose either NP as dou’s domain. The second experiment reinforces the argument that children are much more flexible on domain restriction with the finding that children are able to take an NP which is outside of dou’s scope as the domain. However, the non-adult behavior does not imply that four- to five-year-old children are simply incompetent with dou-quantification/distribution. Actually, the results of our pretests, as well as the previous studies of Lee (1986), Hsieh (2008) and Zhou and Crain (2011), indicate that four- to five-year-old children have full grammatical competence with dou-distribution.

In order to account for children’s seemingly contradictory performance, an explanation that could reconcile the results from the current and previous studies is desirable. We argue that four-year-old children are able to execute the core computational procedure associated with the distributive operator. Children have the knowledge that a distributive operator distributes the property denoted by the VP to the members of the domain. Children’s non-adult interpretations can be attributed to the fact that children assign a different domain to the distributive operator than adults do. We propose that children will become adult-like in processing distributive quantifiers once they consistently assign the same domain as adults do. The question now is how the adult knowledge of domain restriction is acquired.

Our tentative answer is that the domain restriction is acquired with probabilistic learning mechanisms such as the ones that are advocated by Yang (2002, 2004 and Lidz and colleagues (Lidz 2010; Lidz and Gagliardi 2015). Yang (2002, 2004 argues that a combination of Universal Grammar (UG) and statistical learning can account for child language acquisition better than statistical learning alone. UG defines the hypothesis space of possible grammars and constrains it with parameters. Statistical learning then uses the mechanism in (23) to select grammars that are consistent with linguistic input. To make the model simpler, which is sufficient for our purpose, we assume there are only two grammars, G i and G j , in competition.

| For an input sentence, s, the child: |

| (i) with probability P i selects a grammar G i , |

| (ii) analyzes s with G i , |

| (iii) if successful, reward G

i

by increasing P

i

: if

|

| where γ is the learning rate (default γ = 0.05) |

In the case of dou-quantification, the two grammars are G t , the target grammar, and G c , a competing grammar. G t selects the NP that c-commands dou as the domain, and G c potentially a different NP. In order to select a different NP, G c must allow dou to extend its domain to an NP outside of its scope. That is, the c-command requirement is not operative as a domain restriction for G c , but such a requirement serves as a domain restriction for G t . In other words, G t requires the domain of dou to be a c-commanding NP, whereas G c does not impose this requirement and therefore can take an NP that does not c-command dou as dou’s domain.[19]

In Chinese, both G t and G c can parse intransitive sentences correctly since only the subject NP can be the domain. Transitive sentences are more important for children to acquire the domain restriction associated with dou. To be more precise, scenarios such as the ones in our second experiment are compatible with the target grammar G t but not with the competing grammar G c . Recall that in the example item of Experiment 2, one animal chucked out a TV and a bed, and the other a TV and a refrigerator. In this case, an adult should say (24a) rather than (24b), since only the subject NP c-commands dou and thus can be the domain of dou. If children produce (24b), they will likely get negative feedback. Such input will increase the probability of G t (gradually) and will help children to acquire the domain restriction in dou-quantification.

| Xiaodongwu-men | dou | rengdiao-le | dianshi. |

| animal-plu | all | chucked-out-asp | TV |

| ‘The animals all chucked a TV, bed and refrigerator out.’ | |||

| Xiaodongwu-men | dou | rengdiao-le | dianshi, | chuang, |

| animal-plu | all | chucked-out-asp | TV | bed |

| he | bingxiang. | |||

| and | refrigerator | |||

| ‘The animals all chucked a TV, bed and refrigerator out.’ | ||||

Note that we are not saying anything about the exact path of the acquisition of the domain restriction in dou-quantification. That would be another study examining the actual relevant primary linguistic input to children. Nevertheless, if we assume that, ultimately, enough input that favors G t will be available to children, we expect that the probability of G t , i.e., P t , will increase overtime, and we suggest that this is how adults end up adopting G t overwhelmingly. Based on Yang’s (2002, 2004) language acquisition model, we predict that the learning curve of the domain restriction in dou-quantification should be something close to what is shown in Figure 7 below, assuming that G t and G c are initially equally allowed by UG.

The acquisition of the correct domain restriction as a function of relevant input (γ = 0.05, iteration = 1000).

The modeling results suggest that the acquisition of the domain restriction in universal quantification is gradual and probabilistic. This prediction can be tested in the future to see if quantifier spreading in Chinese vanishes in a gradual manner. The model also predicts that when G t is not well established, that is, when P t is not high enough for children to select G t overwhelmingly, children will be uncertain about the domain restriction associated with G t . As a consequence, children may sometimes adopt G c to analyze a target sentence. Since G c does not require the domain to be inside dou’s scope syntactically, it allows the salience status of an NP to have an impact on the selection of the domain. This prediction is borne out clearly in our second experiment.

Now we are ready to return to the phenomenon quantifier spreading reviewed in the Introduction. In Section 1.2, we hypothesized that a promising explanation of children’s symmetrical responses is that children’s domain restriction may be slightly different from adults’ regarding universal quantification. If this explanation is on the right track, we do not need to assume that children are different from adults with regard to their syntactic and semantic knowledge of universal quantifiers. Children do not misunderstand every as an event quantifier (Philip 1995), or an adverbial quantifier (Roeper et al. 2005, 2011), or a weak quantifier (Drozd 2001; Geurts 2003). As Grimshaw and Rosen (1990) and Kang (2001) point out, children may have knowledge of certain linguistics restrictions, yet disobey them anyway. Our hypothesis is that children may not have a solid belief on certain restrictions, in the current case the domain restriction of every, i.e., every must take the NP it merges with as its domain. In other words, children may know, perhaps in a probabilistic sense, that only the NP with which every merges to is its domain. However, if the probability of the relevant restriction is not that high, the restrictions can sometimes be violated, especially when the violation results in an interpretation that is more consistent with the context. This explains why children can take a salient NP outside of its typical scope as the domain of every. As the scope of every is extended to other candidates in the sentence, the NP that is more salient is naturally more readily selected as the domain. In what follows, we will argue that the language acquisition procedure is responsible for this uncertainty of domain restriction.

On the contrary, adults comply more strictly with the principle that the quantifier every needs to quantify over its syntactic complement, that is, the NP it merges to. This may be because the probability of the relevant restrictions is raised given more positive input, and consequently the restrictions will be less possible to be violated (see Figure 6 in Section 3; also cf. Philip [2011: 360]). This explains why adults make much less domain restriction errors than children, but meanwhile such errors still exist in cases where the context strongly encourages a violation of the restrictions. A prominent example of such errors in adults can be found in Minai et al.’s (2012) study, where they report that even the adult subjects had about 30–40% of symmetrical responses in one of their groups (their control group, p. 931), suggesting that even adults were not immune to the domain restriction errors.

To summarize, we assume the following principle (25) to account for quantifier spreading and various salience effects.

| Universal quantification: a universal quantifier UQ imposes universal force on its domain. |

| Domain restriction: UQ’s domain is probabilistically restricted to the NP it merges with. Children take this NP as UQ’s domain probabilistically with some parameter p i that varies across individuals. |

| Salience effects: The distribution of this probability p i is shifted to the NP that is comparatively more salient. |

Previous studies have shown that the knowledge (25a) is firmly established by five years old.[20] The domain restriction in (25b), however, has been shown to be learned later. Children continue to make quantifier spreading errors, and that quantifier spreading does not fade away among eight- to nine-year-olds (Aravind et al. 2017; Roeper et al. 2005, 2011). Importantly, quantifier spreading is not eliminated abruptly even after children are eight or nine years old; on the contrary, the percentage decreases gradually until children are 12 years old or even older. In fact, quantifier spreading can also be found in adults with the extra object design (Brooks and Sekerina 2006; Minai et al. 2012), which means that the probability of making quantifier spreading errors is never 0. A probabilistic approach such as (25b) thus is more compatible with the observed gradual emergence of the adult-style grammar than an absolute rule-based approach. The probabilistic nature of domain restriction opens a window for salience effects in domain selection (25c).

The question now is how the domain restriction (25b) can be a probabilistic constraint. We again resort to Yang’s (2002, 2004) language acquisition model and suggest (25b) is a consequence of the interaction between competing grammars. Let the target grammar be G t . G t selects the NP that every merges with as the domain. By contrast, a competing grammar G c does not necessarily select every’s complement NP as its domain.[21] When the sentence in (4), repeated below as (26), is concerned, we consider the three possible conditions in the primary linguistic input as in (27): one-to-one matching condition, extra-agent condition and extra-object condition (cf. Kang 2001). In the real world there can be many extra objects or extra agents.

| Every pig is eating an apple. |

| a. One-to-one matching condition | b. Extra-agent condition | |

|

|

|

| c. Extra-object condition | ||

|

Both G t or G c can successfully analyze the input under the one-to-one matching condition. We therefore expect (26) to be the easiest for young children to parse under the one-to-one matching condition. This gives a neat explanation to the fact that, in sentence-picture matching tasks, children prefer to choose pictures with one-to-one matching over pictures with an extra object or agent after hearing sentences such as (26) (Brooks and Braine 1996; Brooks et al. 2001; Kuznetsova et al. 2007).

With regard to the extra-agent condition (27b), since the agent is more salient, we expect the domain of every to be primarily the subject NP. That is, if G t is selected to parse (26), only the subject NP can be every’s domain. If instead G c is selected, (26) will be parsed under the influence of the salience effects, and therefore the more salient subject NP is taken as the domain most of the time. This predicts that the majority of children’s answers should be “No, because there is an extra pig who is not eating an apple.” This prediction is substantiated by data from Roeper et al. (2005), Gavarró and Álvarez (2011), Gavarró and Lite (2015) and Aravind et al. (2017).

The most crucial case is the extra-object condition. If G t is selected, children will say “yes” to the test sentence; if G c is selected, the opposite response is obtained. As we have argued, the extra-object scenario gives a salient status to the object NP, so, according to Yang’s (2002, 2004 model in (23), when the probability of G t is roughly equal to the probability of G c , G c can be selected more than 50% of the time. Four- to five-year-old children are likely in this stage. We thus expect that four- to five-year-old children could say “no” to the test sentence (26) even more than 50% of the time under the one-extra-object condition. Again, this prediction is verified by many of the previous studies, as long as other salience effects are not also involved (Aravind et al. 2017; Drozd and van Loosbroek 2006; Gouro et al. 2001; Kang 2001; Minai et al. 2012; O’Grady et al. 2010; Roeper et al. 2011; Sugisaki and Isobe 2001).

With more input and feedback given under the extra-agent and extra-object conditions, we expect that the probability of the target grammar, P t , will increase overtime, and ultimately G t will be adopted as the grammar for every-quantification. The same computational model shown in Figure 7 can thus also be applied to the acquisition of domain restriction in every-quantification.

4 Conclusions

We presented two experiments investigating children’s domain selection of dou-quantification. Both experiments reveal that children behave differently from adults in the domain restriction of dou. The first experiment shows that adults have a preference to select the preposition object as the domain of dou, whereas children do not have such a preference. A plausible explanation that awaits future justification is that children are not as sensitive as adults to pragmatic cues regarding the distribution of dou and they are more likely suffering from similarity-based interference than adults. In addition, the results also indicate that children and adults do not take both NPs simultaneously as the domain, therefore falsifying the assumption that dou is a strict unselective universal quantifier in both children and adults’ grammars. The second experiment indicates that children allow an NP that is not inside the scope of dou to serve as dou’s domain, whereas this is impossible for adults. Therefore, it seems that in children’s grammar dou’s domain is not restricted in the same way as in adults’ grammar.

We propose that the observed non-adult results in the second experiment are due to children’s uncertainty of the domain restriction (the c-command requirement) in dou-quantification. Due to this uncertainty, children can sometimes violate the domain restriction and take an NP that does not c-command dou as its domain. We further argue that children’s uncertainty of domain restriction is derived and explained by Yang’s (2002, 2004 language acquisition model. This model sheds light on children’s general difficulties with universal quantification reflected in quantifier spreading. Quantifier spreading in English-speaking children can be accounted for if children are uncertain about the domain restriction in every-quantification. This explanation is consistent with previous findings concerning various salience effects in quantifier spreading. That is, an NP that is more salient than others is more readily selected as the domain of every, although this NP may be outside of the scope of every.

Funding source: Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金)

Award Identifier / Grant number: 17ZDJ07

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Peng Zhou and Stephen Crain for stimulating discussions during the early stages of this study. Parts of this study have been presented at Workshop on Language Development in Typical and Atypical Populations (Beijing, 2012) and Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition (GALA) (Oldenburg, 2013). We thank the audience for their feedback. We would like to extend our sincere gratitude and appreciation to Samuel Epstein, Richard Lewis, Acrisio Pires, Tom Roeper, and Andrew McInnerney for their many discussions on the topic and their very valuable comments. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Remaining errors are ours.

- 1

We call the syntactic object that the quantifier quantifies over the domain of this quantifier.

- 2

Philip (1995) formalizes this interpretation in terms of event semantics. We present a plain English analysis for the sake of simplicity.

- 3

A syntactic deficiency account such as Roeper et al.’s (2011) quantifier floating approach suffers from the same critism with the semantic approach: the acquisition problem and the flawed experimental design with extra objects.

- 4

See Arnold (1999), Cowles (2003), and Cowles et al. (2007) for psycholinguistic evidence for the salience status of topic compared to non-topic.

- 5

We thank Richard Lewis for his suggestion to use the term “uncertainty”.

- 6

We distinguish “scope” from “domain”. The scope of a quantifier includes all syntactic objects from which the quantifier finds its domain; scope is usually defined by syntactic terms such as c-command (e.g., the scope of every includes all syntactic objects that every c-commands).

- 7

The distinction between a universal quantifier and a distributive operator, according to Lin (1996), is that a universal quantifier is supposed to be able to quantify over an indefinite expression, given that indefinite expressions are treated as variables (Heim 1982; Kamp 1981). However, (i) illustrates that dou cannot quantify over the indefinite expression yi-ge erci fangchengshi ‘one quadratic equation’, unlike the unselective universal quantifier zongshi ‘always’ (Lewis 1975).

(i) Yi-ge erci fangchengshi zongshi/*dou you liang-ge butong de jie. one-cl quadratic equation always/all have two different de solution ‘A quadratic equation always/*all have two different solutions.’ Our experiment uses bare nouns/NPs as quantifier domains for dou, which could be considered as variables and can co-occur with dou. Therefore, as far as our experiments are concerned, the distinction between universal quantifier and distributive operator is not crucial.

- 8

The domain of a universal quantifier is equivalent to the restrictor of a distributive operator.

- 9

We do not consider the exceptional uses of dou in this study, where dou is associated with a syntactic object that does not necessarily c-command dou in the surface structure. For example, Jiang (1998), Pan (2006), and Jiang and Pan (2013), among others, point out that an interrogative wh-phrase or an NP that is focalized can license dou-quantification although they do not c-command dou in the surface structure. The complicated distribution of dou may have made the acquisition of the domain restriction even harder for children.

- 10

Scope (of dou) refers to all the syntactic objects c-commanding dou in a structure (see also ft. 6). The restrictor of dou is selected from the scope of dou. Therefore, our definition of scope is different from Tsai’s (2014, 2015, who takes the syntactic objects that are c-commanded by dou as dou’s scope. In fact, Lin (1998) also assumes that dou binds a variable inside dou’s c-commanding scope. However, in order to agree with dou, the head of the variable must move to a position that c-commands dou, ultimately equivalent to our definition of the scope of dou.

- 11

We follow Huang et al. (2009) that in this structure the preposition zai is a case assigner and is semantically vacuous. It does not denote a location, because the locative pangbian already denotes a location. In addition, pangbian, literally translated as ‘side’, is assumed to be a mixture of a noun and a preposition. Interestingly, as exemplified by (i) below, when only the NP laoying-pangbian inside the PP is a possible domain of dou, the dominant reading is corresponding to the reading where laoying, not the sides of the eagles, is quantified by dou.

(i)[PP Zai laoying-pangbian] dou zhong-le lanhua. p eagle-loc all plant-asp orchid ‘Besides all of the eagles there is an orchid planted.’ The semantic transparency of pangbian confirms that it has the characteristics of prepositions, as indicated by “besides” in the English translation of (i). In our experiment, no subjects understood sentences such as (i) above or (8) in the main text as “at all the sides of the eagles there is an orchid planted.”

- 12

The dual-status analysis of prepositions is of course a stipulation, but this analysis is not rare in the literature (Kayne 1998; Reinhart 1983; Williams 1983, 1989; among others). There is good evidence that prepositions in certain cases do not project. For example, the NPs inside PPs below in (i) behave as if the prepositions were not present, so these NPs can still c-command the reflexive (ia) or the proper name Mary (ib), leading to reflexive binding and Condition C violation, respectively (Hicks 2009).

(i)a.John talked [PP to Mary i] about herself i. b.*John spoke [PP to her i] about Mary i. - 13

See the subject information in the Participants sections of the two experiments.

- 14

Note that five adults (in addition to one child subject) who rejected both filler items without dou were excluded from the analysis, to ensure that the participants included in the analysis are those who can endure the ambiguity of the test sentences observed in (15a). The participants rejected (15a) because the sentence is ambiguous and does not specify the target dog who actually found the football.

- 15

Again, Chinese does not have morphological distinctions between singulars and plurals, so both NPs in (16) can be interpreted either as a singular or as a plural.

- 16

Pearson’s Chi-squared test is not needed in this case given the numbers of “yes” responses in these two conditions are identical.

- 17

Since we have confirmed that children do not have problems taking the subject NP as the domain of dou, as was shown in the pretests and the fillers in our experiments, here we only test whether children can extend the domain of dou to the object NP. The results of the present experiment, however, do show that children can quantify over the subject NP.

- 18

Another possibility that might have led to children’s acceptance of the test sentence is that children ignore dou in the test sentences, resulting in a collective reading, which in turn makes the sentence true under the designed context. This is very unlikely though, because as we have shown clearly in the results of the pretests, the children distinguish sentences with dou from sentences without dou. The perfect results from the fillers of Experiment 1 also strongly suggest that children would not ignore dou.

- 19

Note that we do not rule out the possibility that there may be other restrictions applying to the selection of the domain for the competing grammar. The claim here is that the c-command restriction is not operative as a domain restriction for the competing grammar, leaving open the possibility that other restrictions may be necessary.

- 20

In addition, at 4 or younger, children make the Un-Mentioned Object Spreading (Philip 1995; Roeper et al. 2005), in which children said ‘no’ to the test sentence (1) when the object is not mentioned in the test sentence. This type of errors signals a lack of understanding the basic meaning of universal quantification (exhaustive reading). Such errors disappeared in five years olds.

- 21