Abstract

The Korean anaphor caki-casin, which has been regarded as a local anaphor, has been shown to allow long-distance binding when local binding is not an option (Kim, Ji-Hye & James Yoon. 2009. Long-distance bound local anaphors in Korean: An empirical study of the Korean anaphor caki-casin. Lingua 119. 733–755). In this study, we examined the long-distance binding of caki-casin in domains where local binding is possible, and compare it with the long-distance binding of caki, the representative long-distance anaphor in Korean. Our investigation revealed that the availability of local binding does not rule out long-distance/exempt binding of caki-casin. The results imply that core and exempt binding may not be in complementary distribution, at least in Korean.

1 Introduction

In this paper, we argue that long-distance (LD) binding of local anaphors in Korean is available even in domains when core/local binding is possible. We reach this conclusion by examining the binding behavior of the local anaphor caki-casin. Based on Kim and Yoon (2009) who discovered that caki-casin can be bound long-distance as an exempt anaphor in contexts when the locally c-commanding NP is not a possible antecedent of the anaphor, we conducted an experiment where we investigated the long-distance binding of caki-casin in contexts where the local NP is a possible antecedent and can therefore license it as a locally bound (core) anaphor. Our investigation revealed that caki-casin can be bound by a long-distance antecedent even in such contexts, even though the long-distance binding of caki-casin is not as readily available as in contexts where the local NP is not a possible antecedent. By contrast, long-distance binding of caki, the typical long-distance anaphor, was not affected by the possible antecedent status of intervening NPs.

We take these results to contravene widely held assumptions in the foundational literature on core versus exempt binding where it is maintained that core and exempt binding occur in non-overlapping contexts (Pollard and Sag 1992, 1994; Reinhart and Reuland 1991, 1993). The robust overlap of the two kinds of binding in Korean has implications for the interaction of grammar and discourse when the two provide competing modes of licensing for a given dependency.

The organization of this paper is as follows: Section 2 discusses the theoretical background and introduces some general properties of anaphor binding in Korean. Section 3 describes the research question/hypothesis and the methodology employed in this study. Section 4 presents the results of the study, while Section 5 discusses the interpretations of the results and their theoretical implications. The conclusion follows in Section 6.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 The distribution of anaphors: Core vs. exempt binding

It is well-known that natural languages possess anaphoric expressions such as reflexives and pronouns whose interpretations are constrained by syntax. Principles A and B of Chomsky’s (1980, 1981 classical Binding Theory (BT hereafter) are best known formulations of the syntactic constraints on the interpretation of such anaphoric expressions. BT defines a syntactic domain in which reflexives (also called anaphors) need to be bound by an antecedent but pronouns cannot. As such, it is designed to capture the complementary distribution between pronouns and anaphors seen in sentences such as (1) below.

| John i thinks [that Bill j hurt himself *i/j /him i/*j ]. |

However, it has been known for some time that the complementary distribution of reflexives and pronouns fails to hold, in contexts such as those shown in (2).[1]

| Lucie i saw [a picture of herself i /her i ]. |

| Max i likes jokes [about himself i /him i ]. |

| Lucie i counted five tourists in the room [apart from herself i /her i ]. |

| Jane i thought that [an incriminating picture of herself i /her i ] was being circulated. |

In order to deal with examples such as these, proponents of BT introduced revisions to the algorithm that determines the Binding Domain, so that the Binding Domain for anaphors and pronouns can diverge in some cases. Specifically, the revised BT in Chomsky (1986) accounts for the sentences in (2) by defining the Binding Domain as the smallest complete domain of a head with all its syntactic arguments (dubbed the Complete Functional Complex, or CFC) where the BT could have been satisfied, that is, the minimal BT-compatible CFC containing the anaphoric expression. Since Principle A requires anaphors to be bound, a CFC where an anaphor occurs in the highest (A)-position cannot be the BT-compatible CFC for the anaphor, while it can for a pronoun. In such cases, the Binding Domain for anaphors is extended to the next CFC that is BT-compatible. Assuming that the bracketed constituents in (2a)–(2d) are the minimal CFCs containing the anaphoric expressions, the revised BT correctly predicts that while pronouns simply need to be free within them, anaphors need to go outside them to be bound. Thus, their overlapping distribution is predicted. By contrast, in (1), the embedded clause is a BT-compatible CFC for both reflexives and pronouns, and the two must be in complementary distribution.

While the revised BT makes some progress toward explaining when anaphors and pronouns are in complementary distribution and when they need not be, it still fails to provide an account of the full range of counterexamples to BT. For example, it fails to account for the sentences in (3). In (3a), the revised BT predicts that the anaphor should be bound in the intermediate clause. Though the anaphor is not bound in this domain, the sentence is acceptable. BT predicts that (3b), where the anaphor is unbound, to be unacceptable. Similarly, in (3c), the minimal BT-compatible CFC for the anaphor is the embedded clause and yet the sentence is fine with the anaphor bound by the matrix subject.

| John i said [that the newspaper published [an incriminating picture of himself i /him i ]]. |

| [Physicists like yourself/you] are a godsend. |

| (Ross 1970, quoted in Reinhart and Reuland 1993: 669) |

| Max i boasted [that the queen invited Lucie and himself i /him i for a drink]. |

| (Reinhart and Reuland 1993: 670) |

Data such as (2) and (3) have prompted researchers to develop a comprehensive alternative to the (revised) BT that can draw a principled distinction between anaphors that are in complementary distribution with pronouns and those that are not (Pollard and Sag 1992, 1994; Reinhart and Reuland 1991, 1993, among others). The alternative approach starts from very different premises about the nature of (anaphor) binding. The most important difference is that under this approach not all anaphors are subject to syntactic BT. Only some are, and it is these anaphors that show a complementary distribution with pronouns. It thus posits a distinction between syntactically constrained core (or plain) anaphors and exempt (or logophoric) anaphors that are not constrained by syntactic BT but are licensed extra-syntactically instead. Since it typically makes the distinction between core and exempt binding on the basis of whether an anaphor has a superior co-argument, we call this alternative approach the Argument Structure-based Binding Theory (abbreviated AS-BT).[2] In this approach, exempt anaphors are those without superior co-arguments. This can happen if the anaphor is the sole argument of a monovalent predicate, or expresses the most prominent argument of a polyvalent predicate. The anaphor in (2) expresses the sole argument of the (nominal) predicate, and hence is exempt, while that in (1) has a superior co-argument, Bill, and is predicted to be a syntactic/core anaphor that must be bound in the local (argument structure) domain. The anaphor in (3a) is also exempt, and is free to participate in discourse-sanctioned long-distance binding. The exempt anaphor in (3b) also occurs in an exempt position and is discourse-bound by the addressee, while in (3c), the anaphor is part of a coordinate object, and hence also exempt, since the argument of the verb is the entire coordinate NP and not just a part of it.

While there is some convergence between the mechanisms of how the Binding Domain for anaphors is extended in the revised BT of Chomsky (1986) and how the exempt status of an anaphor is determined in AS-BT approaches, the convergence does not extend very far. For one, in the revised BT, an anaphor in the highest position of a CFC (let’s call such a position an exempt position, though technically, the revised BT does not recognize a distinct class of exempt anaphors) needs to be bound in the next CFC that is BT-compatible. This means that the next CFC must have a binder, and that the anaphor cannot bypass that domain for an antecedent in a more superordinate domain, or be discourse-bound. On the other hand, the AS-BT makes no such predictions. An anaphor in an exempt position is released from the confines of syntactic BT, and is permitted to take long-distance antecedents in a more superordinate domain. Thus, the two theories diverge with respect to sentences such as (3a) and (3c), which show that long-distance binding of an exempt anaphor across a c-commanding DP in the immediate CFC above it is possible, supporting the prediction of AS-BT.

Another difference between the revised BT and AS-BT has to do with whether exempt anaphors can be freed from syntactic conditions on binding, specifically c-command. Proponents of the AS-BT have argued that anaphors in exempt positions can take non-c-commanding antecedents (cf. [4a]) or even discourse antecedents (cf. [3b], [4b]) under the right conditions, neither of which is predicted under the revised BT that requires an anaphor in an exempt position to be bound.

| [Incriminating pictures of himself i /him i published in the newspaper] have eliminated John i ’s chances of being promoted. |

| (Kim and Yoon 2009: 736) |

| John i was furious. The picture of himself i in the museum had been mutilated. |

| (Pollard and Sag 1992: 8) |

A final difference between the revised BT and AS-BT has to do with interpretive properties of anaphors that occupy exempt positions. In the former, since these are still syntactically bound anaphors, they are not expected to behave differently from anaphors bound by c-commanding DPs in a local domain in terms of their interpretive properties. In the latter, anaphors in exempt positions are not syntactically bound, but licensed extra-grammatically. Therefore, these anaphors are expected to show interpretive properties that are different from those that are syntactically bound. It has been claimed that this prediction is borne out. For example, when anaphors are syntactically bound, they cannot have split antecedents while anaphors in exempt positions allow split antecedents, as shown in the contrast between (5a) and (5b). They also show differences in contexts of ellipsis/pro-forms. When the antecedent for VP ellipsis contains a syntactically bound anaphor as in (5c), the elliptical VP preferentially receives a sloppy interpretation rather than a strict interpretation. On the other hand, both sloppy and strict readings can be obtained if the missing VP includes an anaphor that occupies an exempt position as in (5d). The ellipsis in (5d) can be construed either as ‘Bill also thought that an article written by Bill caused the uproar’ or as ‘Bill also thought that an article written by John caused the uproar’.

| *John i asked Mary j about themselves i+j . |

| John i asked Mary j about some pictures of themselves i+j . |

| John i defended himself i against the committee’s accusations. So did Bill . |

| John i thought that an article written by himself i caused the uproar. So did Bill . |

In sum, the AS-BT offers a principled account of the distribution of anaphors and pronouns in ways that are superior to the coverage of the revised BT. This is why the distinction between core and exempt anaphors is widely adopted in current research on anaphor binding (Cunnings and Sturt 2014; Kim et al. 2015; Koornneef 2008, 2010; Runner et al. 2002, 2006, etc.).

However, some researchers (Charnavel and Sportiche 2016; Huang and Liu 2001; Kim and Yoon 2009; Zribi-Hertz 1989) have raised questions about the additional premises held in the foundational works on core versus exempt binding. These additional premises are the following. The first premise has to do with the complementary distribution of core and exempt binding. That is, an anaphor that can be licensed by syntactic BT must be so licensed. It does not seem possible to bypass syntactic BT and license the anaphor as an exempt anaphor. If this were possible, we would not have the standard judgments that serve as the basis for the complementary distribution of anaphors and pronouns in sentences such as (1). Why would we have the judgment that an anaphor cannot be bound by the matrix subject in (1) if long-distance exempt binding remains an option for it? Therefore, the foundational works on AS-BT assume that core and exempt binding are in complementary distribution (Pollard and Sag 1992, 1994; Reinhart and Reuland 1991, 1993; Reuland 2001, 2011). Exempt binding cannot apply in a domain where core binding can. Nevertheless, theoretical and experimental research has uncovered data where this premise seems to be challenged. Consider the sentences in (6).

| John i found [a picture of himself i ]. |

| John i found [Bill j ’s picture of himself *i/j ]. |

Under AS-BT, himself in (6a) is an exempt anaphor while himself in (6b) is a core anaphor because the former lacks a superior co-argument while the other has one, the possessor Bill. Under the assumption that core binding is in complementary distribution with exempt binding, the binding of himself by John is predicted to be well-formed in (6a) but not in (6b). However, experimental investigations of binding in NPs with possessors have found that the interpretation that the AS-BT predicts to be impossible (John = himself in 6b) is accepted by many test subjects (Asudeh and Keller 2001; Runner et al. 2002), indicating that core and exempt binding may not be mutually exclusive in this context.[3]

Zribi-Hertz (1989) provides additional examples where reflexives are long-distance bound across intervening c-commanding subjects. In (7a) below, himself can be interpreted as referring to the matrix subject John even though there is a closer intervening subject, Paul, in the embedded finite clause that should force the anaphor to be bound locally under core binding. Interestingly, while long-distance binding of reflexives is possible in (6) and (7a), Zribi-Hertz (1989) notes that it is disallowed in (7b).

| John i thinks [that Paul hates himself i more than anyone in the world]. |

| *John i thinks [that Paul hates himself i ]. |

| (Zribi-Hertz 1989: 719) |

According to Zribi-Hertz (1989), the contrast between (7a) and (7b) is due to emphasis. An anaphor can bypass syntactic BT and be licensed as an exempt anaphor if such binding is motivated in discourse by factors such as emphasis.

Data like (6b) and (7a) lead us to question the assumption held in standard AS-BT that core and exempt binding are always in complementary distribution. Therefore, one of the goals of the present paper is to investigate this question further based on data from Korean.

A second additional premise that is adopted in standard AS-BT concerns the determination of the domain of core binding. As we have seen, the Binding Domain is taken to be determined by the presence of a superior co-argument. An anaphor without a superior co-argument occurs in a position exempt from syntactic BT. However, Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) argue that not all anaphors in exempt positions are licensed as exempt anaphors, which entails that the domain where core binding applies must be determined differently than in standard AS-BT. They make their argument on the basis of the distribution of inanimate anaphors in French.

If there is any consensus on what an exempt anaphor is, it is that it must be animate. This is because the antecedents of exempt anaphors must be logophoric centers (Sells 1987), animate/sentient beings whose thought, speech and internal attitudes can be assessed. Under the standard AS-BT view of how core versus exempt binding is demarcated, an inanimate anaphor is predicted not to be able to occur in an exempt position. This is because in that position it needs to be licensed as an exempt anaphor, but being inanimate, it cannot. Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) argue that this prediction is not supported, and that inanimate anaphors like elle-même ‘itself’ can occur in exempt positions in French, as seen in (9).

| [Cette loi] i a entraîné la publication d’un livre sur elle-même i (et sur son auteur). |

| ‘[This law]i led to the publication of a book about itselfi (and about its author).’ |

| (Charnavel and Sportiche 2016: 49) |

Elle-même is the sole argument of the predicate, sur ‘about’ in (8) (or of the noun livre, ‘book’, if the preposition is not counted). Hence, it is in an exempt position. AS-BT incorrectly predicts (8) to be ill-formed because the anaphor can only be licensed as an exempt anaphor, but it cannot, being inanimate. However, (8) is well-formed, which can only mean that the inanimate anaphor is licensed as a core anaphor. This in turn implies that the domain for core binding must be defined differently than in standard AS-BT. In (8), the core Binding Domain must be the entire clause, as assumed in BT and its successors.

Therefore, Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) posit that the domain in which core anaphors in French (best exemplified by inanimate anaphors) must be bound is defined by the SSC (Specified Subject Condition) and the TSC (Tensed-S Condition), as shown below.

| [La Terre] i tourne autour d’elle-même i . |

| ‘[The earth]i revolves around itselfi.’ |

| *[La Terre] i pâtit du fait qu’elle-même i n’a pas la priorité sur les hommes. |

| ‘*[The earth]i suffers from the fact that itselfi does not get priority over humans.’ |

| *[La Terre] i subit le fait que de nombreux satellites tournent autour d’elle-même i . |

| ‘*[The earth]i suffers from the fact that many satellites revolve around itselfi.’ |

| (Charnavel and Sportiche 2016: 45) |

The Binding Domain for elle-même in (9a) is the entire clause, where there is a c-commanding antecedent la terre ‘the earth’. The Binding Domain for elle-même in (9b) is the finite clause complement of the noun fait. As the anaphor is not bound in the Binding Domain, it is ungrammatical (due to a violation of the TSC). In (9c), the finite clause complement is again the Binding Domain for the anaphor. The sentence is out because the antecedent is outside this domain (incurring violations of both SSC and TSC). By contrast, under AS-BT, all sentences in (9) (as well as 8) are predicted to be ill-formed because elle-même occupies an exempt position but cannot be licensed as an exempt anaphor.

Though Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) focus on the issue of the determination of the core Binding Domain (in French), they also take a specific position on the first premise of standard AS-BT which holds that core and exempt binding are in complementary distribution. Recall that under AS-BT the anaphor himself in (10a) occupies an exempt position and must be licensed as an exempt anaphor since core and exempt binding are deemed to be in non-overlapping distribution.

| John i dislikes [recent pictures of himself i (showing hair loss)]. So does Susan . |

| (=Susan dislikes pictures of Susan/John) |

| John i dislikes himself i (for no good reason). So does Susan . |

| (=Susan dislikes Susan/*?John) |

In Charnavel and Sportiche’s (2016) approach, the Binding Domain for the anaphor qua a core anaphor is the clause and himself is predicted to be licensed as a core anaphor. However, they also assume that nothing prevents it from being licensed as an exempt anaphor as well, because they assume that the domain of core binding and exempt binding are not mutually exclusive. To the extent that the strict/sloppy reading can serve as a useful diagnostic for core versus exempt binding, the possibility of strict reading in (10a) compared to (10b) suggests that himself in (10a) can indeed be an exempt anaphor. But the fact that the sloppy (bound variable) reading is also possible would mean that core binding is still an option. And though Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) did not discuss binding of anaphors across possessors (6b), their system would predict that such binding is possible, because exempt binding (across the c-commanding possessor) is not ruled out just because core binding is possible in the same domain.[4]

In sum, there are two issues under debate within the overall approach to anaphor binding that posits a distinction between core/syntactic binding and exempt/logophoric binding. The first has to do with the relationship between core and exempt binding: are they in complementary distribution or can they overlap? The second concerns the determination of the domain of core/syntactic binding: is it the domain of argument structure or is the characterization of the domain closer to the view of Binding Domain held in BT?

Yet another question that may be raised about exempt binding is the following: since exempt binding has been investigated mostly in languages with a simple anaphor inventory consisting of local anaphors, how widespread is it? In particular, since one of the behavioral traits of exempt binding is long-distance binding, do languages with a richer inventory of anaphors—local and long-distance—exploit the core-exempt distinction in anaphor binding, or do the long-distance anaphors in the language take over the functional space occupied by exempt anaphors in other languages with a simpler anaphor inventory, especially since it has been found that many long-distance anaphors are subject to logophoric constraints? There aren’t many studies on the core-exempt distinction in languages with both local and long-distance anaphors. Huang and Liu (2001) investigated this question with respect to Mandarin Chinese, but their study focused on the long-distance anaphor ziji, rather than the local anaphor pronoun-ziji. Their conclusion was that locally bound ziji is a core anaphor, while LD-bound ziji behaves as an exempt anaphor, which implies that ziji may not be a true long-distance anaphor, contrary to widely held assumptions. Pollard and Xue (2001) challenge this conclusion, based on LD-bound ziji that is not subject to any special logophoric conditions. To the best of our knowledge, Kim and Yoon (2009) is the only study of a language (Korean) with a rich inventory of anaphors in which the core-exempt distinction was investigated for local anaphors. It is to this study that we now turn.

2.2 Exempt anaphors in Korean

Korean has a rich inventory of anaphors. They can be used interchangeably in many contexts but each anaphor has its own properties (Cole et al. 1990; Kang 1998; Yoon 1989). Among them, the morphologically complex anaphor caki-casin is generally assumed to be a local anaphor due to its preference for local antecedents while the monomorphemic anaphor caki functions as a long-distance anaphor (LDA) because it prefers long-distance antecedents to local ones.

| John i -un | Mark j -ka | caki-casin *i/j -ul/caki i/?j -lul | miwehanta-ko | malhayssta. |

| Johni-top | Markj-nom | caki-casin *i/j/cakii/?j-acc | hate-comp | said |

| ‘John said that Mark hates himself.’[5] | ||||

The question of whether the core versus exempt distinction exists in Korean, a language with both local and LDA, was not investigated until Kim and Yoon (2009). They conducted an experimental investigation to see if native speakers of Korean accept a local anaphor (caki-casin) that appears in a context where it cannot be bound locally and is forced to be LD-bound. They also examined whether the LD-bound caki-casin displays the interpretive properties attributed to exempt binding, such as sensitivity to logophoricity and allowing a greater degree of strict readings in VP ellipsis/proform contexts. The results showed that caki-casin can be coerced into LD-binding when core/local binding is not an option and that LD-bound caki-casin behaves like exempt anaphors in terms of interpretive properties, which led Kim and Yoon (2009) to conclude that the core/exempt binding distinction is independent of the existence of long-distance anaphors in a language.

However, there are shortcomings with their study which weaken their overall conclusions and call for a different study that does not suffer from these deficiencies. In order to evaluate Kim and Yoon (2009), assumptions about what constitutes the Binding Domain for core anaphors and how core and exempt binding relate to each other need to be clarified. Since Kim and Yoon (2009) did not focus explicitly on these questions, but instead on whether exempt binding of local anaphors is attested in a language with a diverse anaphor inventory, we shall reconstruct their positions in what follows, in light of the importance of these questions to the understanding of core vs. exempt binding. We turn first to the question of the determination of the Binding Domain for core binding.

AS-BT posits that a local anaphor in an exempt position can only be licensed as an exempt anaphor. However, in Korean, all kinds of anaphors (local caki-casin, neutral casin,[6] long-distance caki) can occur in what would be considered an exempt position in AS-BT, the subject position of embedded clauses, in violation of the TSC. This is shown in (12) below.

| John i -un | caki-casin i /casin i /caki i -i/ka | ku pan-eyse | ceyil calnassta-ko |

| John-top | self-nom | that class-in | is the best-comp |

| sayngkakhan-ta | |||

| thinks | |||

| ‘Johni thinks that he i is the best in the class.’ | |||

Because all anaphors can violate the TSC, Kim and Yoon (2009) assumed that TSC-violating anaphors are not exempt but core anaphors.[7]

With regard to the role of the Specified Subject Condition (SSC) in defining the core binding domain for local anaphors, things are not straightforward. This is so because when we place the local anaphor caki-casin in a configuration that violates the SSC, the acceptability of the structure seems to depend on the animacy of the SSC-inducing local NP, as shown below.

| *? John i -un | [sensayngnim-i[+animate] | caki-casin i -ul | mwusihanta-ko] |

| John-top | teacher-nom | self-acc | mistreated-comp |

| sayngkakhayssta. | |||

| thought | |||

| ‘Johni thought that the teacher mistreated him i.’ | |||

| John i -un | [hakkyo-eyse[-animate] | caki-casin i -ul | mwusihanta-ko] |

| John-top | school-dat | self-acc | mistreated-comp |

| sayngkakhayssta. | |||

| thought | |||

| ‘Johni thought that the school mistreated him i.’ | |||

That is, when the SSC-inducing local NP is a possible antecedent of caki-casin (being an animate NP), the LD-binding of the anaphor appears to be blocked (cf. [13a]). However, when the local NP is not a possible antecedent of the anaphor (being an inanimate, as in [13b]), LD-binding of caki-casin appears to be sanctioned. The main objective of Kim and Yoon (2009) was to investigate sentences like (13b), which had not been noticed before in the literature, in order to determine if sentences like (13b) are indeed accepted by native speakers of Korean, and if they are, whether the LD-bound caki-casin behaves in a manner typical of core or exempt anaphors. Their experimental investigation confirmed that native speakers accepted sentences like (13b) with LD-bound caki-casin, and that the anaphor behaves in a manner typical of exempt, not core, anaphors when it is LD-bound. Kim and Yoon (2009) reasoned that caki-casin can be LD-bound in (13b) but not (13a), because while local/core binding is possible in (13a), it is impossible in principle in (13b), so that the anaphor is allowed to be licensed via LD/exempt binding.

Kim and Yoon (2009) did not fully explore the consequences of their interpretation of the contrast between (13a) and (13b) for currently debated questions in core and exempt binding, since these questions were not their primary concern. However, we can deduce that their positions on these issues are different from those held in standard AS-based approaches to exempt binding. For one, the fact that they assumed that core anaphors can violate TSC goes against the view held in AS-based approaches that requires anaphors in exempt positions (such as the TSC-violating position) to be exempt anaphors. Rather, their position is consistent with the position advanced later in Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) which holds that core anaphors may occur in exempt positions. With regard to the SSC, the conclusion that Kim and Yoon (2009) reached is consistent with the interpretation where the SSC configuration defines the Binding Domain for core anaphors like caki-casin, but when core binding is not an option (due to the lack of a potential antecedent), the anaphor is allowed to exploit exempt binding (which yields LD-binding, as in 13b). If exempt binding were impossible in core binding domains, (13b) would be judged ungrammatical. In other words, they seem to hold the view that the domains of core and exempt binding are not mutually exclusive, unlike standard AS-based approaches to exempt binding.

Now, if the reason that (13b) is acceptable is because exempt binding can apply in core binding domains, and it is the lack of availability of core binding in the local domain that allows the anaphor contained in the core binding domain to exploit LD/exempt binding, it is predicted that even in (13a), where the anaphor can be licensed under core/local binding by an animate local antecedent, LD/exempt binding should be possible, even though the acceptability of LD/exempt binding in (13a) may not be as robust as in (13b) because that core binding is possible in the embedded clause. Unfortunately, Kim and Yoon (2009) did not investigate sentences like (13a) in their study, but simply assumed that they were ungrammatical. This is a major omission, and we need to examine sentences like (13a) systematically to determine whether LD/exempt binding of caki-casin is possible even when local/core binding remains an option.

The reason Kim and Yoon (2009) did not investigate sentences such as (13a) appears to related to their choice of baseline sentences illustrating local/core binding. Sentences like (13a) with the anaphor bound by the local subject could have been the baseline sentences illustrating local/core binding. Instead of examining them, Kim and Yoon (2009) took TSC-violating sentences where the anaphor is bound by the closest animate NP (cf. 12) to exemplify local/core binding.

However, this assumption turns out to be problematic. For one, the acceptability of a sentence like (12) does not tell us anything about whether speakers are treating the TSC-violating anaphor as core or exempt.[8] Secondly, and more problematically, when the diagnostic properties that differentiate core from exempt binding (such as strict vs. sloppy interpretations in pro-form/ellipsis contexts) were considered, Kim and Yoon (2009) found that there was essentially no difference between the TSC-violating sentences that they took to be baseline examples of core binding and sentences they took to exemplify LD/exempt binding (cf. 13b). TSC-violating caki-casin allowed a high rate of strict readings in pro-form/ellipsis contexts, just like the SSC-violating exempt anaphors in sentences such as (13b). This result, which was replicated in Kim and Yoon (2013), implies that Kim and Yoon’s (2009) study lacked genuine baseline examples of core binding. Baseline sentences exemplifying core/local binding need to be tested. Such sentences would be like (13a), but where the anaphor is bound by the local antecedent.

Another gap in Kim and Yoon’s (2009) study is the following. According to the typology of long-distance reflexives proposed in Cole et al. (2001, 2006, genuine LDAs (bound variable/anaphor type LDAs) are different from the local anaphors turned into exempt anaphors. Kim and Yoon (2009) claimed that LD-bound caki-casin is a local anaphor turned into an exempt anaphor and not a genuine LDA based on the fact that it exhibits the interpretive properties attributed to the exempt anaphors (strict reading availability; sensitivity to logophoricity). However, as Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) reminded us, using diagnostic properties to argue for exempt status is risky, as there are few, if any, properties that categorically distinguish core and exempt anaphors. For example, while LD-bound caki-casin is sensitive to logophoricity, it has long been noted in the literature (Park 1986; Yoon 1989) that genuine LDAs like caki in Korean are also sensitive to it. Therefore, a new way of establishing that the LD-binding of caki-casin differs from that of LDAs like caki needs to be sought.

To sum up, the conclusions reached in Kim and Yoon (2009) – (i) that LD/exempt binding of local anaphors is attested in Korean, a language with a diverse inventory of anaphors, and (ii) that core and exempt binding may not be in complementary distribution – need to be re-evaluated with a properly conducted follow-up study that addresses the shortcomings of the original study. This is because their study lacked genuine examples of baseline sentences showing core/local binding, due to their mistaken identification of TSC-violating sentences as exemplifying core binding, and because they failed to investigate the prediction that LD/exempt binding should be allowed even in sentences like (13a), and not just in (13b). Finally, we need to be able to establish that LD-bound caki-casin is different from typical, bound anaphor/variable type LDAs in its properties.

3 Experiment

3.1 Research questions

The theoretically relevant questions that motivate this study are the following:

Can the domains of core and exempt binding overlap in Korean?

Is the LD-binding of exempt local anaphors different from that of genuine LDAs?

The first question was addressed in Kim and Yoon (2009), but we are investigating it with a study that does not have the design flaws of that work. The second was not addressed in Kim and Yoon (2009), but is important to answer if we are to establish that LD-bound caki-casin is a local anaphor that has been coerced into LD usage, rather than a bound variable/anaphor type LDA.

The following are the specific research questions whose answers will have implications for the answers to the questions just posed.

Q1:

Do native speakers of Korean accept the long-distance exempt binding of caki-casin with a c-commanding animate NP in the core binding domain or only when the c-commanding NP is inanimate?

Q2:

Is there a difference between LD-bound caki and caki-casin with respect to the animacy of the local NP?

The first question attempts to fill a gap in the experimental design of Kim and Yoon (2009). If Kim and Yoon (2009) are correct in assuming that core and exempt binding are not in complementary distribution, we predict that caki-casin can be LD-bound even in the presence of an animate local NP, and not just with inanimate local NPs. In addition, since Kim and Yoon’s (2009) study lacked baseline examples of local/core binding because of mistaken assumptions about the status of the TSC in Korean, we compared the behavior of LD-bound caki-casin with that of the baseline sentences where it was bound by a local antecedent.

Recall that the evidence Kim and Yoon (2009) provided in support of the exempt anaphor status of LD-bound caki-casin was based largely on interpretive properties. Given that these properties are not unique to exempt anaphors, we need to look for a different way in which we can determine if LD-bound caki-casin is an exempt anaphor. This is what the second question addresses. We seek to answer this question by comparing the long-distance binding of caki-casin and caki. If LD-bound caki-casin is an exempt anaphor, and if the licensing of exempt binding involves competition with local/core binding, we expect to find reflexes of such competition. In particular, we expect the possibility of local/core binding to have an effect on the LD-binding of caki-casin. As a genuine LDA, caki will be different, since the LD-binding of caki does not involve competition with local/core binding. Since local/core binding is possible only if an NP that locally c-commands the anaphor is animate, we expect to see the effect of what we shall call animacy intervention in the LD-binding of caki-casin but not in that of caki. On the contrary, if there is no difference between the two, then we would have to revisit the conclusion reached in Kim and Yoon (2009) that LD-bound caki-casin is an exempt anaphor.

3.2 Methods

3.2.1 Participants

Forty native speakers of Korean residing in and around Seoul, South Korea, participated in the experiment (10 males, 30 females, age: M = 21.53, SD = 2.23). None of the participants had reading disorders. They were undergraduate or graduate students at a university in Seoul, South Korea. Eleven participants had experience living in English-speaking countries. Except for one whose length of stay was 4 years, the average length of stay was no more than 1.5 years (Mean length of stay = 10.4 (months), SD = 5.35).[9] Participants received monetary compensations upon completion of the task.[10]

3.2.2 Task and materials

The task used in the experiment was a Truth Value Judgment Task (TVJT, cf. Crain and Thornton 1998) with stories, where participants were asked to read a short story and judge whether the given statement is TRUE or FALSE in the context provided by the story. This task tests a speaker’s interpretation of a given sentence in controlled contexts, and is frequently used when a sentence is ambiguous and/or it is not clear whether a certain interpretation of the sentence is allowed by the grammar. Hence, we used the TVJT since we wanted to test how caki-casin is interpreted in story contexts that require it to be bound by a long-distance antecedent. All the materials were given in Korean.

The test materials included two versions: one with caki-casin and the other with caki. The reason why the task was constructed as a between-subjects design with two versions was to ensure that the interpretation speakers assign to one anaphor does not affect their judgments of the other. To exclude this possibility, the two anaphors were given separately to different participants, so that a participant saw either caki-casin or caki in the test. Twenty participants were tested for each version.

There were 52 items – 10 target items and 42 fillers – in each test version. The target items had two conditions that varied in terms of the animacy of the local NP (animate vs. inanimate). For each condition, five token sets were created. The context (story) always established a long-distance interpretation. However, among the fillers, we had 10 items where the story established a local interpretation. These items were intended as baseline data to counterbalance the usage of the given anaphor as a local/core vs. an LD/exempt anaphor. Because we are testing to see whether caki-casin can function both as a local/core anaphor and LD/exempt anaphor, data showing both local and LD readings of caki-casin are required. The version of the test with caki instead of caki-casin had the same design.

The length of the test items, including fillers, was controlled so that all of the stories were composed of four sentences. All the target sentences were bi-clausal, even when the context established a local interpretation of the anaphor. In all items, the anaphor appeared in the object position of the embedded clause. When the context requires caki-casin to be bound by the long-distance antecedent (the matrix subject, which was always animate), SSC violations ensue. For the items used for baseline data, the antecedent of the anaphor was also either the animate or the inanimate embedded subject, but the test items were still bi-clausal. The matrix verbs used were verbs of saying that facilitated logophoric interpretations,[11] while various verbs such as pota ‘see’, kulita ‘draw’ were used as embedded verbs. The embedded verbs were carefully selected to make sure that their lexical properties did not bias the interpretation of the reflexive in favor of either the local or the LD antecedent.[12]

Sample target items are shown in (14a), (14b). The story shown is true under the LD interpretation of the anaphor. If the test subjects judge the binding between the LD antecedent Youngmi and caki-casin to be possible in the presence of a locally c-commanding NP, they will give a TRUE response. If not, they will give a FALSE response. The same holds for caki. We could not balance TRUE/FALSE responses of the target items, since we could not be sure about how the speakers would interpret the test sentence in advance of actual testing. A filler/baseline item where the story establishes a TRUE local binding interpretation is given in (14c).

| Story with animate local subject (target item: compatible with LD binding interpretation) | |||

| Last weekend, Youngmi and Jieun attended the alumni association meeting. There was an election for president at the meeting. Jieun whispered to Youngmi, “I nominated you (=ne) as president.” After the meeting, when Youngmi saw Hannah later, she told her about what she heard at the meeting. | |||

| ➔ | Youngmi-nun | [ Jieuni -ka | caki-casin-ul/ caki-lul |

| Youngmi-top | Jieun-nom | self-acc | |

| hoycang-hwupo-lo | |||

| president-candidate-as | |||

| chwuchenhayssta-ko] | Hannah-eykey | malhayss-ta. | |

| nominated-comp | Hannah-dat | said. | |

| ‘Youngmi told Hannah that Jieun nominated self as president.’ (self = Youngmi) | |||

| Story with inanimate local Subject (target item: compatible with LD binding interpretation) | |||

| Last weekend, Youngmi and Jieun attended the alumni association meeting. There was an election for president at the meeting. Youngmi whispered to Jieun, “the alumni association nominated me (=na) as president.” Listening to that, Jieun was envious of Youngmi since she always wanted to be a president, so she told Hannah about what she heard at the meeting. | |||

| ➔ | Youngmi-nun | [ tongchanghoy -ka | caki-casin-ul/ caki-lul |

| Youngmi-top | alumni association-nom | self-acc | |

| hoycang-hwupo-lo | |||

| president-candidate-as | |||

| chwuchenhayssta-ko] | Jieun-eykey | malhayss-ta. | |

| nominated-comp | Jieun-dat | said. | |

| ‘Youngmi told Jieun that the alumni association nominated self as president.’ (self = Youngmi) | |||

| Story with animate local subject (filler item: compatible with local binding interpretation) | |||

| Last weekend, Youngmi and Jieun attended the alumni association meeting. There was an election for president at the meeting. Jieun whispered to Youngmi, “I nominated myself (na) as president.” After the meeting, when Youngmi saw Hannah later, she told her about what she heard at the meeting. | |||

| ➔ | Youngmi-nun | [ Jieuni -ka | caki-casin-ul/ caki-lul |

| Youngmi-top | Jieun-nom | self-acc | |

| hoycang-hwupo-lo | |||

| president-candidate-as | |||

| chwuchenhayssta-ko] | Hannah-eykey | malhayss-ta. | |

| nominated-comp | Hannah-dat | said. | |

| ‘Youngmi told Hannah that Jieun nominated self as president.’ (self = Jieun) | |||

The statements used as fillers were well-formed sentences, but they differed in terms of whether they were true descriptions of the story. The number of TRUE and FALSE responses in the fillers was balanced.

3.2.3 Procedure and data analysis

Participants were first requested to fill out a questionnaire about biographic information such as age, gender, and language background. They were then asked to read the instructions for the main task and proceed to do the task. In the main task, participants were asked to judge whether the statements given after the stories correctly described what they read. We analyzed the participants’ responses with mixed effects logistic regression models with a binomial link function, using the ‘lmerTest’ and ‘emmeans’ statistical packages of R version 3.4.1 (R-Core-Team 2012). In our model, we had anaphor type and animacy of the local antecedent as fixed effects, and subjects and items as random effects. We built the models from the maximal random effect structure, following Barr et al. (2013), and progressively simplified the random effect structure until the model converged. The converged model included random intercepts of subjects and items. Planned pairwise comparisons are reported using the Tukey test. In order to ensure that the participants understood the instructions clearly, response accuracy on the filler items was calculated. The average accuracy rate for filler items was about 85%, which indicates that the participants followed the instructions accurately and did not make random guesses about the answers.

4 Results

As for the overall results, participants’ responses were analyzed in the following way – a score of one was assigned to TRUE while zero was assigned to FALSE and then the mean scores for acceptance were calculated for each condition. Table 1 summarizes the mean acceptance scores per experimental condition as well as the mean acceptance scores of locally bound caki-casin and caki used as baseline sentences.

Mean acceptance scores of LD-bound caki-casin and caki by experimental condition.

| LD-binding | caki-casin | caki |

|---|---|---|

| Inanimate local NP | 0.78 | 0.91 |

| Animate local NP | 0.43 | 0.79 |

| Local-binding | ||

| Inanimate local NP | 0.61 | 0.18 |

| Animate local NP | 0.88 | 0.31 |

Descriptive statistics revealed that participants preferred local binding over LD binding for caki-casin, while preferring LD binding over local binding for caki. Crucially, however, the participants allowed LD-binding interpretations for both caki-casin and caki, but their acceptance was modulated by the animacy of the intervening local NP. Overall, the participants were less likely to accept the LD-binding interpretation of the anaphors when the intervening local antecedent was animate (cf. 14a) than when it was inanimate (cf. 14b), but this tendency was much more pronounced with caki-casin than with caki.

For statistical analysis, we ran a mixed effects logistic regression model to determine if and how the LD-binding of caki-casin and caki differs as a function of animacy of the intervening local NP. The fixed effects in the model included anaphor type (Anaphor, caki-casin vs. caki), animacy of the local NP (Animacy, animate vs. inanimate), and their interaction, with subjects and items as random effects. The statistical results are summarized in Table 2.

Fixed effects from the mixed effects logistic regression model performed on acceptance scores of LD-binding of caki-casin and caki (reference levels: caki-casin and inanimate).

| Estimate | SE | z-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.7335 | 0.5035 | 3.443 | 0.000575*** |

| Anaphor: caki | 1.3593 | 0.6589 | 2.063 | 0.039097* |

| Animacy: animate | −2.1130 | 0.5505 | −3.839 | 0.000124*** |

| Anaphor: caki × Animacy: animate | 0.8421 | 0.6175 | 1.364 | 0.172633 |

-

Note: +0.1 > p > 0.05; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

The model revealed main effects of anaphor type (z = 2.06, p < 0.001) and of animacy (z = −3.84, p < 0.05). The main effect of anaphor type implies that participants were more likely to accept the LD-binding of caki than that of caki-casin. This is unsurprising in light of the well-known fact that caki allows long-distance binding robustly, as a genuine LDA (Choi and Kim 2007; Kim and Yoon 2008; Kim et al. 2009a, 2009b; Yoon 1989).[13] The main effect of animacy means that it was easier for participants to allow LD-binding of anaphors when the intervening local NP was inanimate than when it was animate. However, we do not take this to mean that LD binding is disallowed in the presence of an animate intervening local antecedent. As seen in Table 1, this simply means that the acceptance score for LD-binding in the animate local NP condition was lower than that in the inanimate local NP condition.

There was no significant interaction between the two factors. Despite the lack of significant interaction, planned pairwise comparisons were performed using the Tukey test. The results revealed that the LD-binding of caki was not influenced by the animacy of the local NP (z = 2.034, p = 0.18), though that of caki-casin was (z = 3.839, p < 0.001). Moreover, the LD-binding of caki was allowed to a significantly greater degree than caki-casin when the intervening antecedent was animate (z = −3.776, p < 0.001), while the differences between the LD-binding of the two anaphors with inanimate intervening NPs did not reach significance (z = −2.063, p = 0.17). These findings indicate that the LD-binding of caki-casin and caki are different in terms of how they are affected by the animacy of the intervening local NP (a potential antecedent). Caki-casin is impacted by the presence of an animate local NP while caki is not.

In sum, the experimental results showed that the answer to research question 1 (Q1) is affirmative. Native speakers of Korean accepted the LD-binding of caki-casin even when the intervening local NP was animate, though not to the same degree as when it was inanimate. Due to the lack of significant interaction term, we should be cautious in interpreting our results regarding the second research question. However, our data revealed that there was a difference between LD-bound caki and caki-casin with respect to the animacy of the intervening local NP. The effect of animacy intervention was strong for the latter but weak for the former, indicating that the LD-binding of the two may arise in different ways.

5 Discussion

As outlined at the beginning of Section 3.1, an affirmative answer to the first research question implies that exempt binding of a local anaphor is possible in the core binding domain in Korean, meaning that core and exempt binding are not in complementary distribution, as Kim and Yoon (2009) claimed earlier. However, our conclusion rests on a firmer empirical foundation, because we tested a crucial missing condition that their study did not investigate, with proper controls for the baseline condition.

An affirmative answer to the second research question implies that the mechanisms that license LD-binding for caki and caki-casin may be different. Specifically, we can make sense of the fact that LD-bound caki-casin, but not caki, is sensitive to animacy intervention if we take LD-bound caki-casin to be a core anaphor converted into an exempt anaphor. Caki, on the other hand, is an LDA without a locality preference (in fact, if our results are indicative, it has a preference for LD over local binding). Hence the possibility of local binding (which arises when the local NP is animate) does not impact LD-binding significantly.[14] By contrast, if the LD-binding of caki-casin involves the anaphor being converted into an exempt anaphor, we can understand why the possibility of local binding would interfere significantly with LD/exempt binding. In other words, the difference between the LD-binding of caki and caki-casin can be interpreted as evidence supporting the view that the latter is an exempt anaphor while the former is not.

Crucial to our interpretation of the results is the assumption that the lowered degree of LD-binding of caki-casin with intervening animate NPs does not equate to speakers rejecting the LD construal, but arises from the competition between local/core binding and LD/exempt binding. However, since the mean acceptance score is below 0.5, one might take issue with this interpretation and instead take the results to mean the failure of LD-binding over an animate NP. We do not think that this is a viable interpretation, for the following reasons. First, the group mean hovers around chance, but this cannot be the result of simple guessing, since the test subjects were native speakers of Korean and not learners who might make random guesses about grammatical features they have not fully acquired. If the result reflects the judgment that the reading in question is not allowed by the grammar, we expect native speakers to assign a much lower rating.

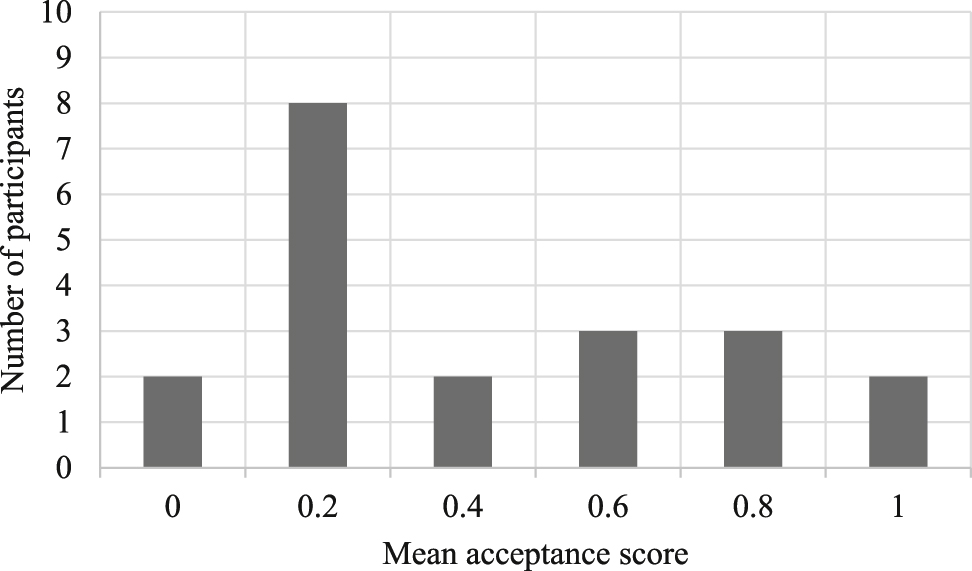

A way in which the two competing interpretations can be teased apart is to examine the individual results. The group mean might mask individual differences. In particular, there may be speakers who reject the LD interpretation, by giving greater weight to local/core binding (licensed by syntax) over LD/exempt binding (licensed by extra-syntactic conditions). But there may also be others who give greater weight to extra-syntactic, discourse licensing over syntactic licensing, for whom LD-binding will be easier to obtain. When we examine the individual results, we find the pattern shown in Figure 1 below.

Number of individual participants per the mean acceptance score of LD-bound caki-casin with an animate local NP.

While the number of subjects in our experiment is small, the individual results show that there is a sizable proportion of speakers (8 out of 20) who accept LD-binding of caki-casin over an intervening animate NP for more than half of the test items (with four speakers accepting all or a majority of such items), while a larger number of speakers (12 out of 20) accept the interpretation for less than half of the test items. We submit that this pattern can be interpreted as being due to the differing weights that native speakers place on syntactic versus extra-syntactic factors, since all of our test subjects were native speakers of Korean.

Another possible way to interpret the mean acceptance score of LD-binding of caki-casin over an animate NP is to reconsider the factors that may have affected its acceptance. As is well known, caki-casin has an inherent bias toward local binding, and our results suggest that LD-bound caki-casin is sensitive to the animacy of the local NP when it is LD-bound. If the local binding preference of caki-casin, independently of an animacy intervention effect, plays an additive role when caki-casin takes an LD antecedent over a locally present NP, then we can expect to see lowered mean acceptance scores. This may be another possibility that can explain why we get an overall acceptance score of about 0.5.

If we are on the right track, the domains of core and exempt binding are not disjoint and the two can compete to license an anaphor in a given domain in the case of Korean. This conclusion is at odds with the position taken in Argument Structure-based Binding Theory (AS-BT) established primarily on the basis of English.[15] The question is why. In order to search for a possible answer, we need to understand how the complementarity of core and exempt binding is assumed to arise in AS-BT. This question is not broached in some works on AS-BT, but simply assumed (Pollard and Sag 1992). However, Reinhart (1983) and Reuland (2001, 2011 seek to find the answer in constraints that regulate the interaction of grammatical and extra-grammatical principles when both can license a given dependency/interpretation. Recall that the premise shared among proponents of AS-BT is that binding can arise through syntactic or extra-syntactic mechanisms, which calls for principles that resolve potential conflicts. Reuland (2001: 466) posits a principle called Rule L which does this. The rule says that if two coreferential NPs A and B can enter into syntactic licensing, they must.

| Rule L: Logophoric Interpretation |

| NP A cannot be used logophorically if there is a B such that an A-CHAIN <B, A> can be formed. |

It is only when the conditions for syntactic licensing are absent that extra-syntactic (logophoric) licensing can apply. And the reason this is so is because of interface economy. Syntactic dependencies are less costly than extra-syntactic dependencies, and that is why extra-syntactic licensing takes a back seat to syntactic licensing in a domain where the latter can apply.

Rule L is modeled on a similar (and older) principle which regulates the distribution of reflexives and pronouns, Rule I.

| Rule I: Intrasentential Coreference (Grodzinsky and Reinhart 1993: 79) |

| NP A cannot co-refer with NP B if replacing A with C, C a variable A-bound by B, yields an indistinguishable interpretation. |

Rule I is designed to rule out situations where a pronoun object bypasses syntactic Binding Theory and becomes co-referential with the subject argument in discourse, yielding sentences such as (17).

| *John i hates him i . |

Since the interpretation established through binding in the syntax is indistinguishable in most cases from that established through co-reference in the discourse, Rule I demands that the syntactic option be chosen, which requires that the object be expressed as a reflexive. That is, like Rule L, Rule I gives priority to syntax over discourse in licensing a given dependency.

Sometimes, however, the co-referential reading between a pronoun and a co-argument NP sanctioned in the discourse emerges. Consider the following sentence, taken from Reinhart (1983, quoted in Koornneef 2008: 39):

| I know what Mary and Bill have in common. Mary adores him i and Bill i adores him i , too. |

In this sentence, co-reference between him and Bill is allowed, meaning that the availability of syntactic binding failed to block the co-reference option established in discourse. Reinhart’s suggestion was that the reason syntax can be bypassed by discourse is because the reading expressed by syntactic binding and that which is relevant in the discourse are not equivalent in (18), though it is difficult to see exactly how they are so. Regardless, what (18) shows is that even though there is a strong tendency for syntax to take priority over discourse in licensing a given dependency (Rule I), it is a tendency that can be overridden in some contexts.

We submit that the same holds for Rule L. Exempt binding normally cannot take place in a domain where syntactic binding can apply, and this is what gives rise to the impression that core and exempt binding are in complementary distribution. However, just as Rule I can be overridden in particular discourse contexts, we hypothesize that Rule L can also be overridden, and when it is, exempt binding is attested in a domain where core/local binding is possible.

Now, while we believe that this is the case for both English and Korean, there is a sense in which bypassing local/core binding in favor of LD/exempt binding in the local binding domain (defined by the SSC configuration) is much more restricted in English than it is in Korean.[16] The relevant examples for English are all drawn from particular registers (see 7 in Section 2.1), while in Korean, a local/core anaphor in an SSC configuration can enter into LD/exempt binding much more easily, especially when the intervening/SSC-inducing NP is inanimate, as we have seen. So, we need an account of the cross-linguistic differences concerning the degree to which syntactic principles can be bypassed by discourse principles in binding interpretations. That is, why is Korean more flexible than English?

While we do not have a definitive answer, we believe that the relative ease with which syntactic binding can be bypassed in favor of discourse binding in Korean may reflect a general property of the language that has been referred to as ‘discourse prominence’. The leading idea behind this term is that the grammar of Korean is influenced to a much greater degree by discourse-pragmatic factors than other languages. Among the better-known proposals that try to develop this intuition more concretely are those that take Korean (and, of course, Chinese) to be topic-prominent, as opposed to, subject-prominent languages (Li and Thompson 1976; Sohn 1980, among others).

What we are suggesting is that another area where we may find reflexes of discourse prominence is in the interface between syntax and discourse when the two compete to license dependencies. As a discourse-prominent language, Korean allows discourse to override syntax to a greater degree than languages that are ‘syntax-prominent’, and this is what allows Rule L to be more easily suppressed when discourse conditions are present to sanction the relevant interpretation. This is at best a conjecture. However, if the conjecture is on the right track, we expect to see a similar state of affairs with respect to Rule I as well. That is, pronoun objects should allow coreference with co-arguments much more easily in Korean than they do in English.

In fact, this is exactly what was found in a series of studies: Kim (2016, 2017) tested native speakers of Korean to see if they allow an object pronoun kunye ‘her’ to be coreferential with its co-argument subject in sentences like (19) when the discourse context supports such an interpretation.

| Janice i -ka | kunye i -lul | taytanhakey | yekiess-ta. |

| Janice-nom | her-acc | highly | thought |

| ‘Janicei thought highly of heri.’ | |||

Interestingly, about half of the participants allowed such readings in violation of Principle B. When the equivalent sentence in English was tested with native speakers of English, no such results were found, even though the coreferential reading of the pronoun with a co-argument was supported by the given discourse context. This contrast between Korean and English is consistent with the greater degree to which native speakers allow discourse to override syntax in the competition between core and exempt binding in Korean.

The discourse prominence of Korean may also be reflected in the resolution of anaphoric expressions when there is a potential competition between a forward discourse dependency and a backward syntactic dependency.

In (20), the pronoun in the adjunct clause in the second sentence can enter into a forward discourse dependency with the discourse topic (the subject of the first sentence) or a backward syntactic dependency with the sentence-internal antecedent (the subject of the second sentence).

| The housemaid/butler was working in the mansion. Before she left, the housemaid/the butler |

| informed the butler about tomorrow’s fire drill. |

| (Liversedge and van Gompel n.d.) |

Kwon (forthcoming) reports that Liversedge and Van Gompel (n.d.) found that both types of dependency are considered by native English speakers during online sentence processing. The formation of a forward discourse dependency is shown by the fact that when the pronoun in the adjunct clause in the second sentence did not match the gender of the discourse topic (e.g., the butler … she), processing difficulty occurred in the pronoun position compared to when there was a gender match (the housemaid … she). The authors take this to be due to the formation of a forward discourse dependency between the discourse topic and the pronoun. However, within the second sentence, they found longer reading times in the subject position when the gender of the NP did not match that of the pronoun (she … the butler), compared to when they matched (she … the housemaid). Liversedge and Van Gompel take this to imply that a backward sentence-internal (syntax) dependency is formed between the pronoun in the adjunct clause and the subject NP, even though the pronoun was already assigned reference through the formation of a forward discourse dependency.

Why would this be so? If we assume that forward dependencies are less costly to process than backward dependencies, but that syntactic dependencies are more economical than discourse dependencies, we can make sense of the results. While directionality favors the discourse dependency, the backward dependency is less costly than the forward one because it is a syntactic dependency. Thus, they pull in opposite directions, and the results show that both are being considered by speakers of English.

Now, if Korean allows discourse to override syntax more easily, we expect to see a different result. In particular, in configurations similar to (20), we would see a greater effect of the forward discourse dependency. Kwon (forthcoming) reports that this is exactly the result that was found in Kwon and Sturt (2013). The study found that when a discourse topic kanhosa ‘nurse’ in (21) was available, the null pronoun pro in Korean formed only a forward discourse dependency with the topic in the previous sentence, and the features of the potential sentence internal antecedent in the second sentence na ‘I’ in (21) were not considered, which implies that a sentence-internal dependency was not formed.

| I | kanhosa i -nun | maywu | chincelhata. |

| This | nursei-top | very | kind |

| ‘This nurse is very kind.’ | |||

| pro i | enceyna | aphun | hwancatul-ul | cengsengsulepkey | kanhohay-se, |

| shei | always | sick | patients-acc | with care | took care-as |

| na j -nun | ipen | ||||

| Ij-top | this | ||||

| sisangsik-eyse | kanhosa-ka | choywuswu | cikwonsang-ul |

| ceremony-at | nurse-nom | best | worker-award-acc |

| patayahanta-ko | cwucanghayssta. | ||

| be awarded-comp | claimed | ||

| ‘Because she took care of sick patients with much care, I claimed that the nurse should be awarded the best employee award at this ceremony.’ | |||

| (Kwon and Sturt 2013) | |||

Though this is in the realm of processing and deals with pronouns, it may nevertheless be another reflection of the way in which discourse can trump syntax with relative ease in Korean, due to its discourse prominence.

In sum, the idea that the discourse prominence of Korean allows a greater degree of infiltration by discourse into the territory that is normally reserved for syntax seems a promising avenue to explore.[17] Note, however, that regardless of the differences in the degree to which a language allows syntactic principles to be overridden by discourse, our conclusion that the domains of core and exempt binding are not disjoint stands, for both English and Korean.

6 Conclusion

The results of the current study showed that Korean local anaphor caki-casin can be bound long-distance as an exempt anaphor even in an SSC violating context. This is consonant with the conclusion in Kim and Yoon (2009), though their study was jeopardized by flaws in experimental design and theoretical assumptions. The status of caki-casin as an exempt anaphor was confirmed by comparing its behavior with that of caki: unlike caki, a genuine LDA, caki-casin was sensitive to the animacy of the intervening antecedent. The acceptance of exempt LD binding of caki-casin varies depending on whether a clause-mate antecedent has matching features or not. If a structurally closer NP is inanimate, it is more easily bypassed and the next plausible NP is taken as antecedent. On the other hand, if a local antecedent is animate, then it is less likely to be bypassed because there is competition between local/core binding and LD/exempt binding. This results in degraded acceptance of LD binding of a local anaphor.

The findings of the present study imply that the assumption made in AS-BT that core and exempt binding are in complementary distribution cannot be maintained, at least for Korean. A domain where core binding can apply does not rule out the application of exempt binding. We tried to make sense of the greater degree to which discourse/exempt binding can override syntax/core binding in Korean by linking it to the discourse-prominent character of the Korean language, which is manifested in different areas where grammar interacts with discourse. As for the question of what constitutes the Binding Domain for core binding, our results, together with those of Kim and Yoon (2009), show that it cannot be defined as the argument structure domain. The core binding domain is defined by the SSC in Korean. This is consistent with the conclusion reached in Charnavel and Sportiche (2016) that the argument structure domain cannot be the core binding domain, and that languages may define the domain in different walys.

References

Asudeh, Ash & Frank Keller. 2001. Experimental evidence for a predication-based binding theory. CLS 37(1). 1–14.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Carl L. 1995. Contrast, discourse prominence, and intensification, with special reference to locally free reflexives in British English. Language 71. 63–101. https://doi.org/10.2307/415963.Search in Google Scholar

Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers & Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68(3). 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001.Search in Google Scholar

Charnavel, Isabelle & Dominique Sportiche. 2016. Anaphor binding: What French inanimate anaphors show. Linguistic Inquiry 47(1). 35–87. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00204.Search in Google Scholar

Choi, Kwang-Il & Yong-Jin Kim. 2007. caykwitaymyengsa-uy tauyseng hayso-kwaceng: Ankwu-wuntong pwunsek [Ambiguity resolution processes of reflexives: Eye-tracking data]. The Korean Journal of Experimental Psychology 19(4). 263–277, https://doi.org/10.22172/cogbio.2007.19.4.001.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1980. On binding. Linguistic Inquiry 11(1). 1–46.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures in government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of language. Westport, CT: Praeger.Search in Google Scholar

Cole, Peter, Gabriella Hermon & Li-May Sung. 1990. Principles and parameters of long-distance reflexives. Linguistic Inquiry 21. 1–22.Search in Google Scholar

Cole, Peter, Gabriella Hermon & C.-T. James Huang. 2001. Long distance reflexives – The state of the art (Syntax and Semantics 33), xiii–xivii. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cole, Peter, Gabriella Hermon & C.-T. James Huang. 2006. Long-distance anaphors: An Asian perspective. In Martin Everaert & Henk van Riemsdijk (eds.), Companion to syntax, vol. 3, 21–84. Malden, MA: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470996591.ch39Search in Google Scholar

Crain, Stephen & Rosalind Thornton. 1998. Investigations in universal grammar: A guide to experiments in the acquisition of syntax and semantics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cunnings, Ian & Patrick Sturt. 2014. Coargumenthood and the processing of reflexives. Journal of Memory and Language 75. 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2014.05.006.Search in Google Scholar

Grodzinsky, Yosef & Tanya Reinhart. 1993. The innateness of binding and coreference. Linguistic Inquiry 24. 69–101.Search in Google Scholar

Han, Chung-hye & Dennis Ryan Storoshenko. 2012. Semantic binding of long-distance anaphor caki in Korean. Language 88(4). 764–790. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2012.0075.Search in Google Scholar

Hole, Daniel. 2002. Spell-bound? Accounting for unpredictable self-forms in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter stories. Zeitschrift für Anglistik und Amerikanistik 50(3). 285–300.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, C.-T. James & Chen-Sheng Luther Liu. 2001. Logophoricity, attitude, and ziji at the interface. In Peter Cole, Gabriella Hermon & James Huang (eds.), Long distance reflexives: Syntax and semantics series, 141–195. New York: Academic Press.10.1163/9781849508742_006Search in Google Scholar

Kang, Beom-Mo. 1998. Three kinds of Korean reflexives: A corpus linguistic investigation on grammar and usage. In Proceedings of the 12th Pacific Asia conference on language, information and computation (PACLIC12). Chinese and Oriental Languages Information Processing Society, Singapore, 10–19.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Ilkyu. 2013. Rethinking “island effects” in Korean relativization. Language Sciences 38. 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2013.01.003.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Eun Hee. 2016. Korean overt pronouns with local antecedents. In Poster presented at the 24th Japanese/Korean linguistics conference (JK 24), Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications Tokyo, Japan.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Ilkyu. 2016. An experimental study on island effects in Korean relativization. Language Research 52(1). 33–55, https://doi.org/10.17250/khisli.34.3.201712.001.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Eun Hee. 2017. Pronoun interpretation with referential and quantificational antecedents in SLA. In Poster presented at the 25th Japanese/Korean linguistics conference (JK 25). Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications Honolulu, Hawaii.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Ji-Hye & James Yoon. 2008. An experimental syntactic study of binding of multiple anaphors in Korean. Journal of Cognitive Science 9(1). 1–30, https://doi.org/10.17791/jcs.2008.9.1.1.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Ji-Hye & James Yoon. 2009. Long-distance bound local anaphors in Korean: An empirical study of the Korean anaphor caki-casin. Lingua 119. 733–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.10.002.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Ji-Hye & James Yoon. 2013. The tensed-S condition (TSC) and the determination of the binding domain of anaphors in Korean. In Proceedings of Japanese/Korean linguistics, Vol. 22(JK22) CSLI Publications, Stanford, CA, pp. 72–84.Search in Google Scholar

König, Ekkehard & Peter Siemund. 2000. Locally free self-forms, logophoricity, and intensification in English. English Language and Linguistics 4(2). 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1360674300000228.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Ji-Hye, Silvina Montrul & James Yoon. 2009a. Binding interpretations of anaphors by Korean heritage speakers. Language Acquisition 16(1). 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10489220802575293.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Ji-Hye, Silvina Montrul & James Yoon. 2009b. Dominant language influence in acquisition and attrition of binding: Interpretation of the Korean reflexive caki. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 13(1). 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/s136672890999037x.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Eunah, Silvina Montrul & James Yoon. 2015. The on-line processing of binding principles in second language acquisition: Evidence from eye tracking. Applied PsychoLinguistics 36(6). 1317–1374. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716414000307.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Eunah, Myeong Hyeon Kim & James Yoon. 2013. An experimental investigation of online and offline binding properties of Korean reflexives. In Proceedings of Japanese/Korean linguistics, Vol. 22(JK22), CSLI Publications, Stanford, CA pp. 85–99.Search in Google Scholar

Koornneef, Arnout Willem. 2008. Eye-catching anaphora. Utrecht: Utrecht University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Koornneef, Arnout Willem. 2010. Looking at anaphora: The psychological reality of the primitives of binding model. In Martin Everaert, Tom Lentz, Hannah De Mulder, Øystein Nilsen & Arjen Zondervan (eds.), The linguistic enterprise: From knowledge of language to knowledge in linguistics, 141–166. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.150.06kooSearch in Google Scholar

Kwon, Nayoung. forthcoming. The processing of long-distance dependencies in Korean: An overview. In Sung-dai Cho & John Whitman (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of Korean linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kwon, Nayoung & Patrick Sturt. 2013. Null pronominal (pro) resolution in Korean, a discourse-oriented language. Language & Cognitive Processes 28. 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2011.645314.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Charles N. & Sandra A. Thompson. 1976. Subject and topic: A new typology. In Charles N. Li (ed.), Subject and topic, 457–489. New York: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Liversedge, Simon P. & Roger P. G. van Gompel. n.d. Resolving anaphoric and cataphoric pronouns. Unpublished MS.Search in Google Scholar

Na, Younghee & Geoffrey J. Huck. 1993. On the status of certain island violations in Korean. Linguistics and Philosophy 16(2). 181–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00985179.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Sung-Hyuk. 1986. Parametrizing the theory of binding: The implications of caki in Korean. Language Research 22. 229–253. https://doi.org/10.3348/jkrs.1986.22.4.490.Search in Google Scholar

Pollard, Carl. 2005. Remarks on Binding Theory. In Stefan Muller (ed.), Proceedings of the 12th international conference on head-driven phrase structure grammar, Department of Informatics, University of Lisbon, 561–577. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.10.21248/hpsg.2005.32Search in Google Scholar

Pollard, Carl & Ivan A. Sag. 1992. Anaphors in English and the scope of Binding Theory. Linguistic Inquiry 23. 261–303.Search in Google Scholar

Pollard, Carl & Ivan A. Sag. 1994. Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar. Chicago, IL & Stanford, CA: The University of Chicago Press & CSLI.Search in Google Scholar

Pollard, Carl & Ping Xue. 2001. Syntactic and non-syntactic constraints on long-distance reflexives. In Peter Cole, Gabriella Hermon & James Huang (eds.), Long distance reflexives: Syntax and semantics series, 317–342. New York: Academic Press.10.1163/9781849508742_011Search in Google Scholar

R Development Core Team. 2012. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org.Search in Google Scholar

Reinhart, Tanya. 1983. Anaphora and semantic interpretation. London: Croom Helm.Search in Google Scholar

Reinhart, Tanya & Eric, Reuland. 1991. Anaphors and logophors: An argument structure perspective. In Jan Koster & Eric Reuland (Eds.), Lond distance anaphora. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. pp. 283–321.10.1017/CBO9780511627835.015Search in Google Scholar

Reinhart, Tanya & Eric Reuland. 1993. Reflexivity. Linguistic Inquiry 24. 657–720.Search in Google Scholar

Reuland, Eric. 2001. Primitives of binding. Linguistic Inquiry 32. 439–492. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438901750372522.Search in Google Scholar

Reuland, Eric. 2011. Anaphora and language design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0050Search in Google Scholar

Ross, John R. 1970. On declarative sentences. In Roderick Jacobs & Peter Rosenbaum (Eds.), Readings in English transformational grammar, Georgetown University Press, Washington. pp. 222–272.Search in Google Scholar