Controversial ultrasound findings in mid trimester pregnancy. Evidence based approach

-

Alaa Ebrashy

, Asim Kurjak

Abstract

Mid trimester fetal anatomy scan is a fundamental part of routine antenatal care. Some U/S soft markers or controversial U/S signs are seen during the scan and create some confusion regarding their relation to fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Example of these signs: echogenic focus in the heart, echogenic bowel, renal pyelectasis, ventriculomegaly, polydactely, club foot, choroid plexus cyst, single umbilical artery. We are presenting an evidence based approach from the literature for management of these controversial U/S signs.

Introduction

Ultrasound (US) has became a crucial tool in the field of fetal medicine.

First and mid trimester scans in particular have become a routine part of antenatal care. These ultrasounds can detect congenital anomalies that are solitary, or part of an underlying chromosomal anomaly. In addition there are a growing number of soft markers that can be seen with US that are associated with chromosomal anomalies or poor pregnancy outcomes.

As US technology has advanced the detection of these soft markers has become easier. With the increased detection of these markers comes confusion regarding the appropriate parental counseling and fetal management. This dilemma is born out of a knowledge gap between the presence of these markers and their clinical significance. We are going to present an evidence- based approach for these markers. We will include the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and underlying risk of associated chromosomal anomalies. We will also include the potential impact on the fetus during the pregnancy and after birth. Our aim is to produce a protocol for the management of pregnancies effected by the presence of these markers.

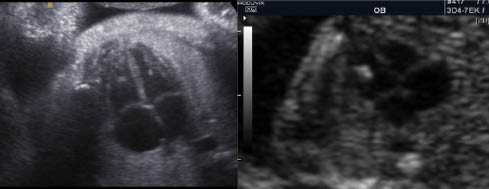

Echogenic focus of the heart

An echogenic focus (EF) of the heart is definced as an echogenic area located in the region of the papillary muscles but not attached to the ventricular walls. They move with the atrioventricular valve and can occur in either cardiac ventricle, but are mainly seen in the left ventricle [1].

EF are seen in approximately 4% of obstetric sonograms with the lowest prevalence in Black populations and highest rates seen in Asian women [2]. The exact etiology of these foci are unclear. While some consider them to be calcifications within the fetal papillary muscle, or collections of fibrous tissue with increased echogenicity, others theorize that they are micro calcifications within the cardiac muscle [2].

In the early 1990s it was reported to be associated with aneuploidy; however, the exact pathophysiologic link remains uncertain. This relation was confirmed in multiple studies, however, most of the studies were with women at high risk for aneuploidy [3].

In a metaanalysis evaluating the relation of EF with Down syndrome (T21), including 11 studies with a total of 51,831 patients, the authors concluded that the prior risk of Down syndrome (as calculated by maternal age, history of previous affected pregnancy and prior screening tests) is increased by a factor of 5.4 when EF are present and reduced by a factor of 0.8 when no foci are detected [3].

In a recent study on 12,373 cases, 267 EFs were diagnosed, 149 of them were isolated, and there were no cases of T21 among women less than 35 years of age [4]. In an another prospective study of 12,672 women, 479 cases of EF were diagnosed, of which 90% were isolated with only one case of T21 (+LH ratio of 2.66). This study concluded that amniocentesis is not warranted in low risk cases with isolated EF [5].

In the absence of aneuploidy, EF has not been associated with structural cardiac abnormalities or childhood myocardial dysfunction when compared with the general population [6].

Suggested protocol of management of EF:

Detailed fetal anatomy to search for any associated anomalies

Isolated EF is considered as incidental finding and does not warrant amniocentesis or further evaluation either prenataly or postnataly

Amniocentesis should be done to rule out aneuploidy only in high risk cases, such as: >35 years of age, associated abnormalities, other soft markers, or history of chromosomally abnormal pregnancies.

Choroid plexus cyst

Choriod plexus (CP) cysta are cysts that are seen within the substance of the choroid plexus. They can be single or multiple, unilateral or bilateral, and occur with an incidence of approximately 1%. They may result from entrapement of cerebral spinal fluid with tangled villi. As the stroma of decreases with increasing gestational age this fluid is relased and the the cyst resolves. For this reason more than 95% of these cysts resolve by the end of the second trimester [7].

The presence of a CP cyst has been associated with increased risk of trisomy 21, but even more so with trisomy 18 [8]. Seventy-one percent of trisomy 18 fetuses have CP cysts but these are usually associated with additional sonographic abnormalities [9]. The location, size, and morphology do not affect its relation to aneuploidy [9]. Isolated CP cysts create confusion, as its link to increased risk of chromosomal anomalies is less clear [9]. In a metaanalysis of more than 2000 cases with an isolated CP Cyst showed that trisomy 18 was found in one case out of 128 [10]. Based on the findings of this metaanalysis, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends offering amniocentesis in the case of an isolated CP cyst only if the age is >35 or with abnormal serum multiple marker screen [11]. Another large metaanalysis with 246,545 cases found 1346 cases of isolated CP cyst. The study concluded that only when a CP cyst was present with additional risk factors was an amniocentesis warrented [8].

Suggested protocol for the management of a CP cyst:

Careful examination for the fetal anatomy for any additional abnormalities:

careful examination of the hands and feet are very helpful as most of the cases with trisomy 18 are associated with limb posture abnormalities

A FE can be considered.

No invasive procedures for aneuploidy except if:

maternal age >35 years

presence of any other sonographic abnormalities

positive serum aneuploidy screen.

Parents should be advised that most of these cysts will disappear during pregnancy and that they are not associated with any long-term effects like mental retardation, cerebral palsy, or delayed development.

Follow-up ultrasounds are not generally needed, because most CP cysts resolve.

Follow up for growth pattern may be suggested in women with high risk who refrain from doing an invasive test since trisomy 18 is usually associated with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) [12].

Since the attitude and reaction towards CP cyst and EF has been changing, it was not surprising to see a paper published recently with an interesting title: “It is time to reconsider our approach to EF and choroid plexus” [13].

Single umbilical artery

A single umibical artery (SUA) is the most common anomaly of the cord and occurs in approximately 1% of all deliveries [14]. It may result from primary aplasia of one of the two umbilical arteries or as a consequence of atrophy of one artery [14]. It is more commen in the left artery and occurs more often in twin gestation. It is sometimes accompanied with abnormal cord insertion in the placenta, i.e. marginal and velamentous cord insertions [14].

The sonograpic diagnosis can be made either by visualizing a transverse section of a free loop of the cord or by using color Doppler to identify both arteries on both sides of the bladder in a longitudinal section of the abdomen. Using the latter method has the benefit of indentifying which side is missing [15]. The diameter of the cord with only two vessels tends also to be larger than a three vessel cord as well, with a diameter of >4 mm or a vein/artery ration of <2 perhaps being diagnostic of SUA [15]. Lastly, multiple segments should be examined to exclude fusion of the two arteries.

SUA has been associated with fetal anomalies and also with a worse pregnancy outcome when compared to fetuses with two umbilical arteries [16]. In general the increased fetal morbidity and mortality associated with pregnancies with SUA is mainly attributable to increased rates of associated anomalies and aneuploidy [16, 17]. The most common associated anomalies with SUA are cardiac and genitourinary [16]. SUA at 11–14 weeks has a high association with trisomy 18 and other chromosomal defects [17]. Dagklis et al. showed that the finding of an SUA should prompt the sonographer to search for other fetal defects, and if these are found, the risk for chromosomal abnormalities is increased. In cases of apparently isolated SUA there is no evidence of increased risk of chromosomal abnormalities [18].

Suggested protocol of management of SUA:

A detailed fetal anatomy scan should be done as well as fetal echocardiography.

In cases with isolated SUA and maternal age <35 years, invasive testing is not warranted.

Serial growth scans are warranted because SUA has been associated with increased rates of IUGR.

Color Doppler of the umbilical artery should be offered whenever there is oligohydramnios or IUGR [17].

Mild ventriculomegaly

Ventriculomegaly is a condition caused when there is dilated atrium beyond 10 mm. The mild ventriculomegaly (MVM), or what is called borderline ventriculomegaly, range between 10–12 mm and 10–15 mm [19]. It can be an isolated finding or be associated with an underlying cranial defect or anomaly such as agenesis of the corpus callosum. It is seen in almost 0.1–0.2% of births.

In a study of 140 fetuses with both isolated and non-isolated ventriulomegaly only 5% had an abnormal karyotype and only 4.3% of fetuses with MVM were abnormal. Interestingly isolated ventriculomegaly was associated with a higher risk of karyotypic abnormality as compared to those with additional anomalies [20]. The authors therefore recommended karyotype analysis in all cases of ventriculomegaly.

The remaining issue now is parental counseling. The implication of MVM without underlying cranial abnormality or fetal abnormality is slightly confusing due to the lack of good quality postnatal follow-up studies in the literature. This makes antenatal counseling for this abnormality very difficult. In one study of 60 cases of fetuses with isolated MVM of 10–12 mm that were followed up to 10 years of life, they found that all of the children displayed normal neurodevelopment. They concluded that MVM of 10–12 mm may be considered a normal variant [21].

In a recent review of cases with MVM up to 15 mm with postnatal follow-up they found that about 11% of infants with isolated MVM will display abnormal or delayed neurodevolpment. However, the authors go on to state, in conclusion, that given the lack of good quality postnatal follow-up studies it is difficult to provide accurate antenatal counseling [22].

Suggested protocol in cases of MVM:

First reassess the atrial diameter using the recommended criteria.

Perform a careful survey of the fetal brain to exluce concominant pathology.

Follow-up US should be performed to determine if the lesion is progessing

It is reasonable to offer chromosomal analysis to all patients.

Counsel parents that there is limited evidence on the long-term neurodevelopmental consequences.

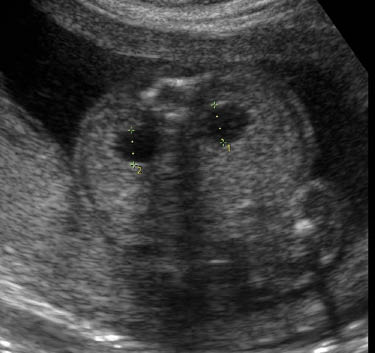

Renal pyelectasis

Dilatation of the renal pelvis is a common finding with an incidence reported to be between 0.3 and 4.5%. It is more common in male fetuses, and is often bilateral; however, if it is unilateral it is more likely to present on the left side. Although laterality does not seem to useful as a prognositic indicator, according to one study unilateral pylectasis is associated with a higher rate of urinary tract abnormalities at birth [23].

Mild pyelectasis refers to dilatation of the renal pelvis >4–5 mm and <10 mm in the antero-posterior diameter measured in transverse section of the fetal abdomen. The cut-off value which is most frequently used in this dimesion is >4 mm in the 2nd trimester and >7 mm thereafter [23].

The relation of mild pylectasis and aneuploidy, mainly trisomy 21, was first suggested by Benacerraf et al. in 1990 [23]. Others studies have subsequently supported this finding, however, all studies were done on high-risk populations [23]. Additionaly, a large multicenter prospective observational study of unselected fetuses between 16 and 26 weeks found that its association was strongest in the presence of other anomalies [24].

Examining cases of isolated mild pylectasis has found that there is very little association with aneuploidy. In a retrospective study of 25,582 low-risk pregnancies, 301 cases of isolated pyelectasis (>5 mm) were detected and none had aneuploidy [25]. In another study, Coplen and Jeanty studied 12,672 cases of which 2.9% had mild pyelectasis (>4 mm). Eight-three percent of these were isolated, and a likelihood ratio for T21 was 3.79 [26]. They concluded that in the absence of other findings, isolated pyelectasis is not a justification for amniocentesis. Lastly, another study of isolated pyelectasis was found to have a sensitivity of 0.02 for diagnosing fetuses with Down syndrome. In that case it would be necessary to screen 30,404 women in order to find one case of Down’s [27].

Pyelectasis, as mentioned above, can also be a marker for possible postnatal urinary tract abnormality. In 60–70% of fetuses found to have pyelectasis, the dilation remains stable. In only 1/3 does the pylectasis progress [28]. Wollenberg et al. showed that none of 20 children with a prenatal diagnosis of mild renal pelvis dilatation (7–9.9 mm) during the 3rd trimester experienced a urinary tract infection or underwent surgery [28]. In contrast five of 22 (23%) cases with a renal pelvis diameter of 10–14.9 mm and 23 of 36 (64%) cases with severe hydronephrosis (>15 mm) had either a UTI or required surgery after birth.

Suggested protocol in cases of renal pyelectasis:

Accurate measurement of the renal pelvis in the proper plane.

Careful search for associated fetal anomalies abnormalities.

Fetal echocardiogram to evaluate the fetal heart.

In the absence of other fetal anomalies, soft markers, or risk factors there is no need for invasive aneuploidy testing.

Thirty percent of cases with mild pyelectasis will proceed to hydronephrosis, and therefore follow-up of the renal pelvis diameter in the 3rd trimester is recommended.

All infants with persistent mild pyelectasis should undergo postnatal evaluation.

Echogenic bowel

The bowel is considered to be echogenic when it is bright compared to the adjacent bone. A echogenic bowel is reported to be present in 0.2–1.4% of 2nd trimester USs and be diffuse or focal. When present it can be associated with aneuploidy (trisomy 21), congenital infection (CMV, toxoplasmosis, parvovirus), cystic fibrosis, intra amniotic bleeding, IUGR, and thalassemia [29]. The pathophysiology of echogenic bowel differs according to the etiology [29]. In T21, poor bowel motility results in thickened meconium. In fetal infection meconium peritonitis and bowel edema results in perforation and focal calcification at the perforation sites. In IUGR the cause is areas of ischemia due to redistribution of blood flow away from the gut. In cystic fibrosis it is caused by abnormal pancreatic enzymes leading to change in meconium consistency. This leads to diffuse or focal echogenic areas with dilated bowel.

In intra-amniotic bleeding the swallowing of blood causes the increased echogenicity.

The diagnosis is made by comparing the echogenicity of the bowel to that of the liver and adjacent bone, such as the iliac crest. This can be acomplished by turning the gain setting down until other soft tissues are no longer seen and only the bone and bowel is visualized [29]. Many studies have tried to grade the echogenicity of bowel, however, the association with adverse pregnancy outcomes is strongest when the bowel is as echogenic as or more echogenic than bone [30]. To avoid confusion we recommend the use of a strict criteria for the diagnosis (echogenicity similar to the bone) in order reduce over diagnosis of echogenic bowel.

The prognosis of echogenic bowel depends mostly on whether or not it is associated with fetal abnormalities. One study showed that 34% of fetuses with echogenic bowel and IUGR or elevated maternal alpha fetoprotein have a poor perinatal outcome [31]. A larger study with 682 cases of echogenic bowel showed that 65.5% of the pregnancies resulted in the birth of a normal healthy newborn [32].

Protocol management suggested in the case of echogenic bowel:

Perform a detailed fetal anatomy scan to evaluate for other abnormalities.

Carefully examine the placenta and amniotic fluid to rule out an intraamniotic bleed.

Both parents should be tested for cystic fibrosis.

Maternal serologic testing for CMV and toxoplasmosis with both IgG and IgM, if amniocentisis is performed the PCR can be performed.

Amniocentes is recommended even when present as an isolated finding.

If all are normal, we recommend strict follow-up for the detection of IUGR.

Antenatal surveillance with Doppler or BPP seems warranted due to possible association with fetal demise.

Club foot

Club foot (talipes equinovarus) is an abnormal relationship of the foot/ankle to the tibia and fibula. The foot is excessively planter flexed with the forefoot bent medially and the sole facing inward. It occurs in 0.1–0.4% of pregnancies and is bilateral 60% of the time. It is also more common in males.

The best way to detect it with US is when the long axis of foot is in same plane as the long axis of the tibia and fibula [33]. Club foot may occur in isolation or in association with numerous other conditions, such as general musculoskeletal disorders, arthrogryposis, genetic syndromes, neural tube defects and spine defects [33]. In 10–14% of cases it coexists with other structural malformations. First degree relatives of a person with idiopathic club foot are at a higher risk of having a club foot when compared with the general population [34]. The risk of a subsequent pregnancy being affected by club foot is 2% if a previous male fetus was affected and 5% if the previous affected fetus was female [34].

In 6–22% of cases it is associated with aneuploidy, with trisomy 18 being the most common [35]. Most cases of club foot with concominant chromosomal anomalies will demonstrate other structural abnormalities. Therefore chromosomal analysis is recommended upon evidence of additional structural anomalies. In the absence of other structural anomalies, oligohydramnios, and IUGR isolated club foot has not been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Post natal successful surgery is obtained in 52–91% of cases enabling most children to participate in normal activities [34].

Protocol of management suggested in the case of club foot:

Sonographic detection of club foot warrants a detailed fetal anatomic survey, and fetal echocardiography should also be considered.

Amniocentesis should be recommended in all cases even though frequency of aneuploidy is low, because ultrasound may fail to detect subtle but significant associated abnormalities and the true frequency of aneuploidy is uncertain.

Polydactyly

Polydactyly is the presence of an extra finger or toe. It is more common in Black women and two types are recognized: type A is when the extra digit is well developed, whereas in type B the extra digit is rudimentary with only soft tissue and no skeletal structure [36]. The extra digit can be preaxial (radial or tibial side) or postaxial (ulnar or fibular side).

Polydactyly may be present as part of a syndrome or as an isolated finding. It is sometimes familial, so family history is very helpful to exclude the association with other abnormalities. Chromosomal study may be offered if there is no familial history of polydactyly. Patients should be informed that fetuses with an isolated finding of polydactyly usually have a favorable outcome, however, parents should also be informed that at present it is not possible to definitely exclude the possibility of a rare anomaly, such as Bardet-Biedl syndrome [36].

Protocol of management suggested in the case of polydactyly:

Perform an anatomic survey, including a detailed examination for other limb abnormalities.

If it is an isolated finding and there is a reported family history of polydactyl then no further testing is necessary.

If it is an isolated finding and there is no family history reported then it is reasonable to offer a chromosomal analysis.

Parents should be counseled about rare possibilities such as Bardet-Biedl syndrome.

Conclusion

Our increasing ability to dectect soft markers with US early in gestation has led to confusion regarding the appropriate management and parental counseling. In this article we have used the best available literature to create a roadmap for these difficult situations. We hope that by following these protocols obstetricians and fetal medicine specialists will be able to more accurately counsel the parents regarding the long- and short-term prognosis of their fetus and direct them to the best evidence-based managements.

Lastly, Dagklis et al. showed the presence of some soft markers (EF, echogenic bowel, and hydronephrosis) at 11–13 weeks increases the risk of aneuploidy even in the presence of a normal nuchal translucency [37]. Searching for and identifying these markers can alter the counseling and management of our patients. We believe the routine evalution for the markers listed in this article can have a meaningful impact on the care we provide.

References

[1] Huggon IC, Cook AC, Simpson JM, Smeeton N, Sharland G. Isolated echogenic foci in the heart as a marker of chromosomal abnormality. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:6–11.10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00307.xSearch in Google Scholar

[2] Bromely B, Lieberman E, Shipp TD, Richardson M, Benacerraf BR. Significance of an echognic intracardiac focus in fetuses at high and low risk for aneuploidy. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:127–31.10.7863/jum.1998.17.2.127Search in Google Scholar

[3] Sotriadis A, Makrydimas G, Ioanidis PA. Diagnostic performance of intracardiac echogenic foci for down syndrome: a meta analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003:101:1009–16.10.1097/00006250-200305000-00031Search in Google Scholar

[4] Anderson N, Jyott R. Relationship of isolated fetal intracardiac echogenic focus to trisomy 21 at the midtrimester sonogram in women younger than 35 years. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:354–8.10.1002/uog.89Search in Google Scholar

[5] Coco C, Jeanty P. An isolated echogenic heart focus is not an indication for amniocentesis in 12,672 unselected patients. Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:489–96.10.7863/jum.2004.23.4.489Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wolman I, Jaffa A, Geva E, Daimant S, Strauss S, Lessing JB, et al. Intracardiac echogenic focus: no apparent association with structural cardiac abnormality. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2000;15:216–8.10.1159/000021009Search in Google Scholar

[7] Walkinshaw SA. Fetal choroid plexus cysts are we there yet? Prenat Diagn. 2000;20:657–62.10.1002/1097-0223(200008)20:8<657::AID-PD866>3.0.CO;2-SSearch in Google Scholar

[8] Yoder PR, Sabbagh RE, Gross SJ, Zelop CM. The second trimester fetus with isolated choroid plexus cysts: a meta analysis of risk of trisomies 18 and 21. Obstet gynecol. 1999;93:869–72.10.1097/00006250-199905001-00038Search in Google Scholar

[9] Reinsch R. Choroid plexus cysts –association with trisomy: prospective review of 16059 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1381–3.10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70363-6Search in Google Scholar

[10] Demasio K, Canterino J, Ananth A, Fernandez C, Smulian J, Vinzileos A. Isolated choroid plexus cyst in low risk women less than 35 years old. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1246–9.10.1067/mob.2002.127463Search in Google Scholar

[11] American College of Obstetrician and gynecologists. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Practice Bulletin no.27, May, 2001. Obstet Gynecol. 2001, 97(supply):1–12.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Digioanni LM, Quinlan PM, Verp MS. Choroid plexus cysts: infant and early childhood developmental outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:191–4.10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00251-2Search in Google Scholar

[13] Bethune M. Time to reconsider our approach to echogenic intracardiac focus and choroid plexus cysts. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:137–41.10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00826.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Sepulveda W, Dezerega V, Carstens E, Guitierrez J. Fused umbilical arteries: prenatal sonographic diagnosis and clinical significance. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:59–62.10.7863/jum.2001.20.1.59Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Rembouskos G, Cicero S, Longo D, Sacchini C, Nickolaides KH. Single Umbilical artery at 11–14 weeks gestation: relation to chromosomal defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22:567–70.10.1002/uog.901Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Gosset DR, Lantz ME,Chisholm CA. Antenatal diagnosis of single umbilical artery: is fetal echocardiography warranted? Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:903–8.10.1097/00006250-200211000-00014Search in Google Scholar

[17] Gomall AS, Kurinczuk JJ, Konje JC. Antenatal detection of single umbilical artery: dose it matter? Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:117–23.10.1002/pd.540Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Dagklis T, Defigueiredo D, Staboulidou I, Casagrandi D, Nicolaides KH. Isolated single umbilical artery and fetal karyotype. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36:291–5.10.1002/uog.7717Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Senat V, Bernad P, Schwarzler P, Britten J, Ville Y. Prenatal diagnosis and follow up of 14 cases of unilateral ventriculomegaly. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;14:327–32.10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14050327.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Gezer C, Ekin A, Ozeren M, Taner CE, Ozer O, Koc A, et al. Chromosome abnormality incidence in fetuses with cerebral ventriculomegaly. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34:387–91.10.3109/01443615.2014.896885Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Signorelli M, Tiberti A, Valseriati D, Molin E, Cerri V, Groli C, et al. Width of the fetal lateral ventricular atrium between 10-12 mm: simple variation of the norm. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:14–18.10.1002/uog.941Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Melchiorre K, Bhide A, Gika AD, Pilu G, Papageorghiou AT. Counseling in isolated mild fetal ventriculomegaly. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:212–24.10.1002/uog.7307Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Benacerraf BR, Mandell J, Estroff JA, Harlow BL, Frigoletto F. Fetal pyelectasis a possible association with down syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:58–60.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Chudleigh PM, Chitty LS, Pembrey M, Campbell S. The association of aneuploidy and mild fetal pyelectasis in an unselected population: the results of a multicenter population. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17:197–201.10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00360.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Havutcu A, Nikolopoulos G, Adinkra P, Lamont R. The association between fetal pyelectasis on second trimester ultrasound scan and aneuploidy among 25586 low risk unselected women. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22:1201–6.10.1002/pd.490Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Coco C, Jeanty P. Isolated fetal pyelectasis and chromosomal abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:732–8.10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.074Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Smith-Bindman R, Chu P, Goldberg JD. Second trimester prenatal ultrasound for the detection of pregnancies at increased risk of down syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27:884.10.1002/pd.1725Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Wollenberg A, Neuhaus J, WilliV, Wisser J. Outcome of fetal renal pelvic dilatation diagnosed during the third trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:483–8.10.1002/uog.1879Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Al-Kouatly H, Chasen S, Streltzoff J, Chervenak F. The clinical significance of fetal echogenic bowel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1035–8.10.1067/mob.2001.117671Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Strocker Am, Snijders RJ, Carlson DE, Greene N, Gregory KD, Walla CA, et al. Fetal echogenic bowel: parameters to be considered in differential diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:159–23.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Sepulveda W, Sebire NJ. Fetal echogenic bowel: a complex scenario. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:510.10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00322.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Simon-Bouy B, Muller F; French collaborative group. Hyperechogenic fetal bowel and down syndrome: results of French collaborative study based on 680 prospective cases. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22:189–92.10.1002/pd.261Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Malone F, Maino T, Bianchi D, Johnston K, Dalton M. Isolated club foot diagnosed prenatally: is karyotyping indicated. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:437–40.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Dietz. F. The genetics of idiopathic club foot. Clin Orthop. 2002;401:39–48.10.1097/00003086-200208000-00007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Offerdal K, Jebens N, blaas H, Eik-nes S. Prenatal ultrasound detection of talipes equinovarus in a non selected population of 49314 deliveries in Norway. Ultrasound Obstet Gyecol. 2007;30:838–44.10.1002/uog.4079Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Zimmer EZ, Bronshtein M. Fetal polydactyly during early pregnancy: clinical applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:755–8.10.1067/mob.2000.106974Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Dagklis T, PLasencia W, Maiz N, Duarte L, Nicolaides K. Choroid plexus cyst, intracardiac echogenic focus, hyperechogenic bowel and hydronephrosis in screening for trisomy 21 at 11+0 to 13+6 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31:132–5.10.1002/uog.5224Search in Google Scholar PubMed

The authors stated that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

©2016 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Current topics on ultrasound in perinatology

- Recommendation and Guidelines for Perinatal Practice

- Ultrasound in Africa: what can really be done?

- 3D/4D sonography – any safety problem

- Controversial ultrasound findings in mid trimester pregnancy. Evidence based approach

- Academy’s Corner

- Sonoembryology by 3D HDlive silhouette ultrasound – what is added by the “see-through fashion”?

- Original articles – Obstetrics

- How effective is ultrasound-based screening for trisomy 18 without the addition of biochemistry at the time of late first trimester?

- Single center experience in selective feticide in high-order multiple pregnancy: clinical and ethical issues

- Diagnostic accuracy of cervical elastography in predicting labor induction success: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Birth weight-related percentiles of brain ventricular system as a tool for assessment of posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus and ventricular enlargement

- First trimester erythropoietin (EPO) serum concentration as a potential marker for abnormal placentation disorders. Reference values for erythropoietin (EPO) concentration at 11–13+6 weeks of gestation

- Original articles – Fetus

- Nonimmune fetal ascites: identification of ultrasound findings predictive of perinatal death

- First trimester severe ductus venosus flow abnormalities in isolation or combination with other markers of aneuploidy and fetal anomalies

- Evaluation of the adequacy of reference charts for the accurate identification of fetuses with bone length below the 5th percentile

- Does ethnicity have an effect on fetal behavior? A comparison of Asian and Caucasian populations

- Accuracy of ultrasound in estimating fetal weight and growth discordancy in triplet pregnancies

- Fetal nasal bone length in the second trimester: comparison between population groups from different ethnic origins

- Pregnancy outcome and long-term follow-up of fetuses with isolated increased NT: a retrospective cohort study

- Effect of antenatal betamethasone administration on Doppler velocimetry of fetal and uteroplacental vessels: a prospective study

- Opinion paper

- Fetal cerebro-placental ratio and adverse perinatal outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and diagnostic performance

- Congress Calendar

- Congress Calendar

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Current topics on ultrasound in perinatology

- Recommendation and Guidelines for Perinatal Practice

- Ultrasound in Africa: what can really be done?

- 3D/4D sonography – any safety problem

- Controversial ultrasound findings in mid trimester pregnancy. Evidence based approach

- Academy’s Corner

- Sonoembryology by 3D HDlive silhouette ultrasound – what is added by the “see-through fashion”?

- Original articles – Obstetrics

- How effective is ultrasound-based screening for trisomy 18 without the addition of biochemistry at the time of late first trimester?

- Single center experience in selective feticide in high-order multiple pregnancy: clinical and ethical issues

- Diagnostic accuracy of cervical elastography in predicting labor induction success: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Birth weight-related percentiles of brain ventricular system as a tool for assessment of posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus and ventricular enlargement

- First trimester erythropoietin (EPO) serum concentration as a potential marker for abnormal placentation disorders. Reference values for erythropoietin (EPO) concentration at 11–13+6 weeks of gestation

- Original articles – Fetus

- Nonimmune fetal ascites: identification of ultrasound findings predictive of perinatal death

- First trimester severe ductus venosus flow abnormalities in isolation or combination with other markers of aneuploidy and fetal anomalies

- Evaluation of the adequacy of reference charts for the accurate identification of fetuses with bone length below the 5th percentile

- Does ethnicity have an effect on fetal behavior? A comparison of Asian and Caucasian populations

- Accuracy of ultrasound in estimating fetal weight and growth discordancy in triplet pregnancies

- Fetal nasal bone length in the second trimester: comparison between population groups from different ethnic origins

- Pregnancy outcome and long-term follow-up of fetuses with isolated increased NT: a retrospective cohort study

- Effect of antenatal betamethasone administration on Doppler velocimetry of fetal and uteroplacental vessels: a prospective study

- Opinion paper

- Fetal cerebro-placental ratio and adverse perinatal outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and diagnostic performance

- Congress Calendar

- Congress Calendar