Abstract

Objectives

Adolescence is a critical period for psychosocial development, often marked by elevated stress levels. The present study examines the role of psychosocial factors as predictors of adolescent stress, with a focus on personality traits, social support, and family health.

Methods

A cross-sectional sample of 1,104 school-going adolescents from Telangana, India were analysed. Using the Adolescence Stress Scale and various psychosocial scales, hierarchical multiple regression and path analysis were employed to assess direct and indirect effects of psychosocial variables on stress levels.

Results

Key predictors of stress included ill-health experiences, conscientiousness, emotional instability, and psychosocial support. Together, these factors explained 6 % of the variance in stress. Serial mediation analysis revealed significant indirect effects, where family health and emotional efficacy acted as mediators between psychosocial factors and stress. Emotional instability and frustrative non-reward responsiveness were the strongest predictors of stress.

Conclusions

Psychosocial factors play a significant but modest role in adolescent stress, highlighting the need for further research into additional contributors. Interventions targeting family health and emotional regulation may alleviate stress among adolescents.

Introduction

Stress is a common factor throughout life, but certain stages, such as adolescence, involve stress originating from multiple sources, often peaking during this period. Adolescence is marked by hormonal changes that are not easily observed, and visible physical transformations. These changes induce significant emotional shifts largely due to hormonal imbalances and insufficient coping skills to manage these transformations. Older adolescents experience more frequent and intense [1] negative emotions compared to younger adolescents. A longitudinal study [2] found that negative emotions increase significantly between the ages of 10 and 14. These changes also influence adolescents’ social interests, including desire for intimate relationships, often accompanied by stigmas, peer pressure, and harassment (Bansal et al. 2021). These pressures often conflict with family, religious, and personal values [3]. Additionally, adolescents face heightened academic demands [4] and the need to make important career decisions [5].

Not all adolescents perceive their stress as insurmountable. However, those who do, often resort to health-risk behaviors, such as smoking, substance abuse, unsafe sex, or antisocial actions. According to the National Bureau of Crime [6]; adolescent suicide accounted for 7.4 % in 2020 and 6.5 % in 2021. The World Health Organization [7] reports a suicide occurs every 40 seconds globally and every 4 minutes in India. Various factors influence stress intensity, including personality traits like hardiness, locus of control, self-efficacy, and emotional stability [8]. Individuals with emotional stability experience lower stress levels and have less reactive sympathetic nervous systems [9]. In their review of 250 studies, Luo et al. [10] identified the five most consistent contributors to stress as extraversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness, openness, and agreeableness. Thus, personality also moderates stress [11], with high agreeableness linked to increased interpersonal stress and lower social support-seeking behaviors. Family relationships and friendships are significant stress factors [12], and academic pressures are another major contributor [13]. Smith [14] notes that adolescents in the U.S. cite school, college admissions, and family finances as primary stressors.

Overall, the literature suggests a strong link between psychological and social factors and adolescent stress. Despite extensive research on adolescent stress, few studies have explored the mediating pathways through which psychosocial factors influence stress, particularly in the Indian context. India presents unique socio-cultural dynamics, such as intense academic pressures, collectivist family structures, and societal expectations, which may amplify adolescent stress differently compared to Western populations. For instance, the emphasis on competitive examinations and familial roles often heightens stress during adolescence [15]. Thus, this study aims to explore the psychosocial factors contributing to adolescent stress and explore their mediating role in either alleviating or exacerbating stress among Indian adolescents to bridge the research gaps. This study addresses these gaps by examining serial mediation models to understand how family health, emotional efficacy, and personality traits mediate stress among Indian adolescents, contributing novel insights to global as well as cultural literature on adolescent mental health.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 1,156 school-going adolescents aged between 11 and 18 years (mean age=14.59) from nine educational institutions in rural and urban regions of Telangana, India. After accounting for subject attrition and missing data, the final sample size was 1,104 students. Missing data, which reduced the sample from 1,156 to 1,104 participants, were handled via listwise deletion, as the missingness was minimal (4.5 %) and random, minimizing bias (Little’s MCAR test, p>0.05).

The participants were distributed across different educational levels: Grade 6 (11.6 %), Grade 7 (12.6 %), Grade 8 (12.9 %), Grade 9 (12.4 %), Grade 10 (12.1 %), 11th grade (14.6 %), 12th grade (12.5 %), and first-year under-graduates (11.3 %). The gender distribution was nearly balanced, with 48.9 % girls and 51.1 % boys. Participants were grouped into early adolescence (11–14 years), which comprised 46.6 % of the sample, and late adolescence (15–18 years), comprising 53.4 %. Geographically, 46.4 % of participants resided in urban areas, 30.2 % in semi-urban areas, and 23.5 % in rural areas. In terms of economic background, 0.7 % came from economically poor backgrounds, 5.8 % from the lower middle class, 68.5 % from the middle class, 22.9 % from the upper middle class, and 2.1 % from the upper class.

Tools

The study used the Adolescence Stress Scale as its primary instrument, along with 11 additional psychological tools to measure various psychosocial factors contributing to stress.

Adolescence Stress Scale

The Adolescence Stress Scale [16] consists of 31 items covering 10 dimensions: major loss-induced stress, enforcement or conflict-induced stress, phobic stress, interpersonal conflict-induced stress, punishment-induced stress, illness and injury-induced stress, performance stress, imposition-induced stress, insecurity-induced stress, and unhealthy environment stress. The total score ranges from 31 to 155, with dimension scores calculated by summing individual item ratings. A mean score above 2.5 indicates high stress, while a mean score below 2.5 indicates low stress. The internal consistency of the scale was α=0.90, with dimensions ranging from α=0.50 to 0.80. Test-retest reliability was significant (r=0.57, p<0.01), as were convergent (r=0.29, p<0.01) and discriminant validity (r=0.20, p<0.01).

Self-efficacy questionnaire for children (SEQ-C)

The SEQ-C [17] is a 24-item, five-point Likert scale with three subscales: social self-efficacy, emotional self-efficacy, and academic self-efficacy, each containing eight items. Internal consistency for this study ranged from α=0.85 to 0.88.

Self-esteem scale

This 10-item, four-point scale [18] measures self-worth by assessing both positive and negative self-feelings. For this study, internal consistency was α=0.87.

Big five questionnaire for children (BFQ-C)

This 65-item, 13-factor questionnaire [19] measures five personality traits: energy/extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional instability, and intellect/openness. Higher scores reflect greater dominance of the corresponding trait. Internal consistency for dimensions ranged from α=0.65 to 0.81.

Frustration non-reward responsiveness subscale (FNRS)

Developed by Wright et al. [20]; this four-point subscale is part of the behavioral approach system (BAS) and behavioral inhibition system (BIS). It includes five items measuring lowered approach motivation following non-reward. Internal consistency was found to be 0.59.

Social skills scale

Developed by Wright et al. [21]; this 23-item, four-point scale measures social skills across five dimensions: leadership, team integration, affiliative, interpersonal, and social engagement skills. Reliability for the dimensions ranged from α=0.36 to 0.68, with an overall internal consistency of α=0.84.

Family health questionnaire

This five-point scale [22] measures individual and family health processes and resources across four dimensions: family healthy lifestyle, family social and emotional health processes, family health resources, and family external social support. Internal consistency ranged from α=0.82 to 0.92, with an overall α=0.86 for this study sample.

Psycho-social support scale

This 22-item, five-point scale [23] measures perceived psychosocial support across six dimensions: social support network, family-based psychological support, communicative support, supportful disposition, psychosocial support deprivation, and psychosocial support availability. Internal consistency for the total scale was α=0.79, with dimensions ranging from α=0.49 to 0.67.

Physical health scale

This scale, specifically constructed for this study, assesses the physical health of participants in three sections: health history (10 items), health risk habits (15 items), and ill health experiences (21 items). Test-retest reliability was r=0.57 (p<0.01) for health history, r=0.63 for health risk habits, and r=0.29 for ill health experiences. Internal consistency was α=0.68 for health history, α=0.70 for health risk habits, and α=0.83 for ill health experiences.

Perceived physical environment scale

This 32-item scale was developed to assess participants’ perceptions of their physical surroundings, including residence, neighbourhood, and access to essential services. Higher scores indicate a more adverse physical environment. Test-retest reliability over two months was r=0.44 (p<0.01), and internal consistency was α=0.79.

Protective factors scale

Taken from the resilience test battery [24], this 24-item scale measures characteristics that help individuals confront adversity. Participants rate each protective factor on a 10-point scale, from low strength (1) to high strength (10). The internal consistency was α=0.75.

Promotive factors scale

This 14-item scale, also from the resilience test battery [24], measures environmental resources that help individuals cope with adversity. Participants rate the availability of these resources on a 10-point scale. Test-retest reliability was r=0.57 (p<0.01), and convergent and discriminant validity were r=0.29 and r=0.20 (p<0.01), respectively.

It is to be noted that lower reliability in some dimensions (e.g., α=0.36 for interpersonal skills) reflects the diverse behavioural contexts assessed, consistent with prior validations. These were retained to preserve theoretical coverage, and their interpretation was approached cautiously.

Procedure

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee, University of Hyderabad (Ref. No. UH/IEC/2021/174). Following this, written administrative approval was obtained from the participating educational institutions, along with informed consent from parents and informed assent from the students. Data collection was then initiated. The participants completed two tests per day in their respective classrooms. Tests requiring a re-test to establish reliability were re-administered to the participants within a fortnight.

Results

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS versions 21 and 26, as well as AMOS version 21, to explore the role of psychosocial factors in predicting adolescent stress levels. Prior to conducting statistical analyses, data were checked for adherence to regression and structural equation modeling (SEM) assumptions. Normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests, confirming that variables approximated normal distributions (p>0.05). Linearity was verified through scatterplot inspections, showing linear relationships between predictors and the outcome variable (stress). Multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factor (VIF) values, all of which were below 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity.

Hierarchical multiple regression

Pearson’s correlation was calculated to identify psychosocial factors significantly associated with the overall stress levels. Of the 16 variables analysed, 12 showed significant correlations with stress levels, as presented in Table 1. Hierarchical multiple regression was employed, where predictor variables were entered into the regression equation in a predetermined order to assess the unique contribution of each predictor to the dependent variable, while controlling for other variables [25]. Table 2 provides a summary of the hierarchical multiple regression analysis for various psychosocial variables predicting stress in adolescents.

Means, standard deviations and correlations of predictor variables with total stress levels.

| Predictor variables | M, SD | Criterion (Stress) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived physical environment | 31.16 (7.49) | 0.034 |

| Self-efficacy | 78.96 (10.40) | 0.042 |

| Self-esteem | 16.52 (2.48) | 0.045 |

| Extraversion | 41.57 (8.18) | 0.054 |

| Frustrative non-reward responsiveness | 10.53 (2.70) | 0.061a |

| Ill health experiences | 30.32 (7.93) | 0.062a |

| Social skills | 60.84 (10.39) | 0.082b |

| Health risk habits | 6.05 (1.98) | −0.085b |

| Family health | 116.24 (15.27) | 0.095b |

| Openness | 37.54 (7.12) | 0.095b |

| Protective factors | 181.90 (29.04) | 0.107b |

| Agreeableness | 33.22 (6.44) | 0.113b |

| Promotive factors | 105.38 (17.71) | 0.118b |

| Psycho-social support | 88.50 (12.30) | 0.129b |

| Conscientiousness | 39.05 (8.35) | 0.146b |

| Emotional instability | 29.08 (6.22) | 0.147b |

-

M, mean; SD, standard deviations; ap<0.05; bp<0.01.

Summary table of hierarchical multiple regression analysis for a range of psychosocial variables predicting stress in adolescents.

| Model and predictor variables | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | R2 change | B | SE | β | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (C=32.18, F=4.15 a ) | 0.061 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.004a | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward | 0.528 | 0.259 | 0.061 | 2.04a | ||||

| Responsiveness | ||||||||

| Model 2 (C=24.32, F=3.57 a ) | 0.080 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward | 0.442 | 0.264 | 0.051 | 1.68 | ||||

| Responsiveness | ||||||||

| Ill health experiences | 0.155 | 0.090 | 0.053 | 1.72 | ||||

| Model 3 (C=11.54, F=6.26 c ) | 0.130 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.010c | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward | 0.550 | 0.264 | 0.064 | 2.08a | ||||

| Responsiveness | ||||||||

| Ill health experiences | 0.202 | 0.090 | 0.069 | 2.24a | ||||

| Social skills | 0.233 | 0.069 | 0.104 | 3.40c | ||||

| Model 4 (C=12.05, F=7.47 c ) | 0.163 | 0.026 | 0.023 | 0.010b | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward | 0.559 | 0.263 | 0.065 | 2.13a | ||||

| Responsiveness | ||||||||

| Ill health experiences | 0.278 | 0.093 | 0.095 | 2.99b | ||||

| Social skills | 0.215 | 0.068 | 0.096 | 3.15b | ||||

| Health risk behaviors | −1.208 | 0.365 | −0.102 | −3.31c | ||||

| Model 5 (C=6.811, F=7.58 b ) | 0.183 | 0.033 | 0.029 | 0.007b | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward | 0.638 | 0.264 | 0.074 | 2.42a | ||||

| Responsiveness | ||||||||

| Ill health experiences | 0.320 | 0.094 | 0.109 | 3.41b | ||||

| Social skills | 0.169 | 0.070 | 0.075 | 2.40a | ||||

| Health risk behaviors | −0.990 | 0.372 | −0.084 | −2.66b | ||||

| Family health | 0.140 | 0.050 | 0.092 | 2.79b | ||||

| Model 6 (C=5.28, F=7.18 c ) | 0.236 | 0.056 | 0.048 | 0.022c | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward | 0.451 | 0.271 | 0.052 | 1.67 | ||||

| Responsiveness | ||||||||

| Ill health experiences | 0.252 | 0.095 | 0.086 | 2.66b | ||||

| Social skills | 0.079 | 0.077 | 0.035 | 1.02 | ||||

| Health risk behaviors | −0.754 | 0.372 | −0.064 | −2.02a | ||||

| Family health | 0.119 | 0.050 | 0.078 | 2.37a | ||||

| Openness | −0.072 | 0.138 | −0.022 | −0.52 | ||||

| Agreeableness | −0.030 | 0.146 | −0.008 | −0.21 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.362 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 2.79b | ||||

| Emotional instability | 0.397 | 0.118 | 0.106 | 3.38c | ||||

| Model 7 (C=4.49, F=6.87 c ) | 0.243 | 0.059 | 0.051 | 0.003a | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward responsiveness | 0.466 | 0.270 | 0.054 | 1.72 | ||||

| Ill health experiences | 0.279 | 0.096 | 0.095 | 2.91b | ||||

| Social skills | 0.026 | 0.081 | 0.012 | 0.32 | ||||

| Health risk behaviors | −0.691 | 0.373 | −0.059 | −1.85 | ||||

| Family health | 0.104 | 0.050 | 0.068 | 2.06a | ||||

| Openness | −0.076 | 0.138 | −0.023 | −0.55 | ||||

| Agreeableness | −0.035 | 0.146 | −0.010 | −0.24 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.337 | 0.130 | 0.121 | 2.58b | ||||

| Emotional instability | 0.399 | 0.117 | 0.107 | 3.40c | ||||

| Protective factors | 0.056 | 0.028 | 0.070 | 1.97a | ||||

| Model 8 (C=4.26, F=6.66 c ) | 0.251 | 0.063 | 0.053 | 0.004a | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward responsiveness | 0.434 | 0.270 | 0.050 | 1.61 | ||||

| Ill health experiences | 0.292 | 0.096 | 0.099 | 3.05b | ||||

| Social skills | 0.018 | 0.081 | 0.008 | 0.22 | ||||

| Health risk behaviors | −0.700 | 0.373 | −0.059 | −1.88 | ||||

| Family health | 0.078 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 1.51 | ||||

| Openness | −0.088 | 0.138 | −0.027 | −0.64 | ||||

| Agreeableness | −0.041 | 0.145 | −0.011 | −0.28 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.335 | 0.130 | 0.120 | 2.58b | ||||

| Emotional instability | 0.413 | 0.117 | 0.110 | 3.52c | ||||

| Protective factors | 0.029 | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.92 | ||||

| Promotive factors | 0.102 | 0.049 | 0.078 | 2.08a | ||||

| Model 9 (C=3.54, F=6.77 c ) | 0.263 | 0.069 | 0.059 | 0.006b | ||||

| Frustrative non-reward responsiveness | 0.460 | 0.270 | 0.053 | 1.70 | ||||

| Ill health experiences | 0.311 | 0.096 | 0.106 | 3.25b | ||||

| Social skills | −0.008 | 0.082 | −0.003 | −0.09 | ||||

| Health risk behaviors | −0.684 | 0.372 | −0.058 | −1.84 | ||||

| Family health | 0.019 | 0.056 | 0.012 | 0.34 | ||||

| Openness | −0.089 | 0.137 | −0.027 | −0.65 | ||||

| Agreeableness | −0.056 | 0.145 | −0.015 | −0.39 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.336 | 0.130 | 0.120 | 2.59b | ||||

| Emotional instability | 0.435 | 0.117 | 0.116 | 3.71c | ||||

| Protective factors | 0.019 | 0.031 | 0.024 | 0.60 | ||||

| Promotive factors | 0.082 | 0.049 | 0.062 | 1.65 | ||||

| Psycho-social support | 0.196 | 0.071 | 0.104 | 2.75b |

-

C, constant; B, unstandardized beta coefficient, SE, standard error, β, standardized beta coefficient, ΔR2, R2 change; ap<0.05, bp<0.01, cp<0.001.

Each psychosocial factor added hierarchically to the models, resulted in nine models. Model 9 was significant, F(12, 1091)=6.77, p<0.001, explaining an additional 0.6 % of the variance (R2 change=0.006, p<0.01), with a total of 6 % of the variance in stress levels accounted for (adjusted R2=0.059), indicating a modest but significant contribution of the identified predictors. While this suggests that other factors, such as genetic or environmental influences, also play a role, low explained variance is common in psychological research due to the complexity of human behavior [26]. The analysis revealed that ill health experiences (β=0.11, p<0.01), conscientiousness (β=0.12, p<0.01), emotional instability (β=0.12, p<0.001), and psychosocial support (β=0.10, p<0.01) were significant predictors of stress – offering valuable insights for designing targeted interventions, such as emotional regulation programs, despite the modest overall impact.

Serial mediation

A serial mediation model was developed using path analysis to evaluate the direct and indirect effects of psychosocial factors on stress. This process involved several steps: confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), testing a hypothetical model, and model confirmation.

Confirmatory factor analysis. The steps involved in this stage are described below in two sections: (i) measurement model, and (ii) structural model.

Measurement model: The measurement model is essential for structural equation modeling (SEM) and was used to validate the indicators for each construct [27]. CFA was performed on a sample of 1,104 participants, separate from the sample used for exploratory factor analysis. variables with factor loadings below 0.3, and in some cases below 0.4, were considered insufficiently representative and were removed [28]. Table 3 presents the goodness-of-fit statistics for the tools used to assess psychosocial factors and stress in adolescents.

Structural model: Following the measurement model, the structural model was analysed to examine the directionality and significance of the relationships. The goal was to evaluate the serial mediation model using path analysis. This serial mediation path analysis was carried out in two steps: hypothetical model and model confirmation.

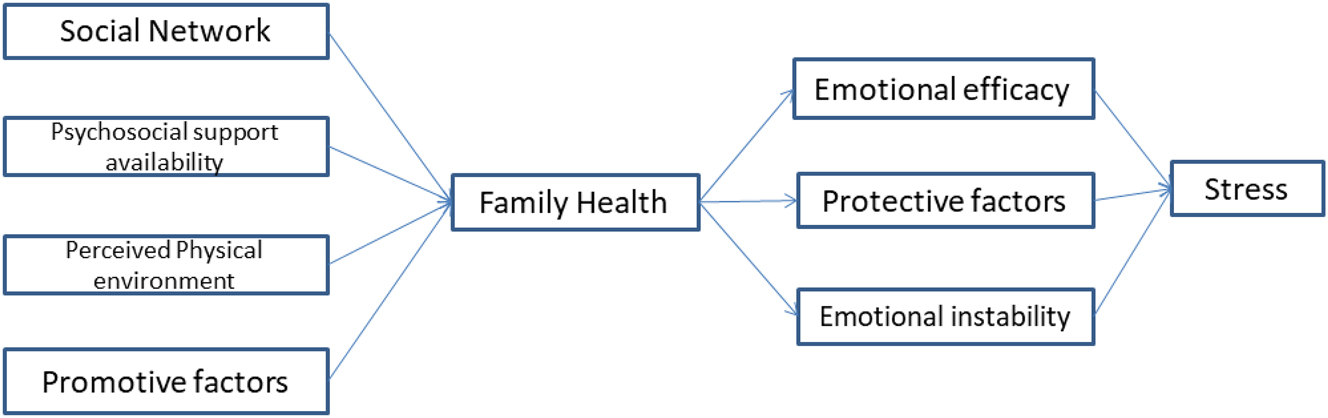

Hypothetical model. A hypothetical model was constructed based on a comprehensive literature review, with social networks, psychosocial support availability, perceived physical environment, and promotive factors considered as independent variables. Family health was proposed as the first mediator, directly associated with emotional efficacy, protective factors, and emotional instability, which together act as the second mediator leading to the dependent variable, stress. The hypothetical model is depicted in Figure 1.

Hypothetical model for depicting serial mediation path model between psychosocial factors and stress in adolescents.

Goodness-fit statistics for the tools measuring psychosocial variables and the number of items deleted after conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

| Measures | Chi-square/df | GFI | AGFI | CFI | RMSEA | No. items deleted post-CFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy scale | 2.790 | 0.957 | 0.957 | 0.912 | 0.04 | 3 |

| Self-esteem scale | 1.257 | 0.998 | 0.993 | 0.937 | 0.015 | 5 |

| Frustration non-reward responsiveness (FNR) scale | 0.835 | 0.999 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Social skills scale | 4.157 | 0.928 | 0.912 | 0.866 | 0.054 | 2 |

| Family health questionnaire | 3.642 | 0.918 | 0.904 | 0.911 | 0.049 | 3 |

| Physical health II (risk behaviors) | 5.331 | 0.991 | 0.973 | 0.982 | 0.063 | 10 |

| Physical health III (ill health experiences) | 5.126 | 0.931 | 0.912 | 0.867 | 0.061 | 4 |

| Physical environment scale | 6.534 | 0.922 | 0.900 | 0.777 | 0.071 | 16 |

| Protective factors scale | 3.805 | 0.930 | 0.917 | 0.922 | 0.050 | 2 |

| Promotive factors scale | 9.570 | 0.910 | 0.874 | 0.872 | 0.088 | 2 |

| Openness | 5.818 | 0.958 | 0.737 | 0.880 | 0.06 | 2 |

| Agreeableness | 3.805 | 0.979 | 0.966 | 0.948 | 0.05 | 4 |

| Extraversion | 5.445 | 0.949 | 0.928 | 0.863 | 0.06 | 1 |

| Conscientiousness | 4.49 | 0.966 | 0.949 | 0.936 | 0.056 | 2 |

| Emotional instability | 4.652 | 0.970 | 0.953 | 0.863 | 0.63 | 3 |

| Psychosocial support scale | 3.841 | 0.941 | 0.923 | 0.912 | 0.05 | – |

| Adolescence stress scale | 1.667 | 0.902 | 0.876 | 0.933 | 0.043 | – |

-

df, Degrees of freedom; GFI, Goodness-of-Fit Index; AGFI, Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

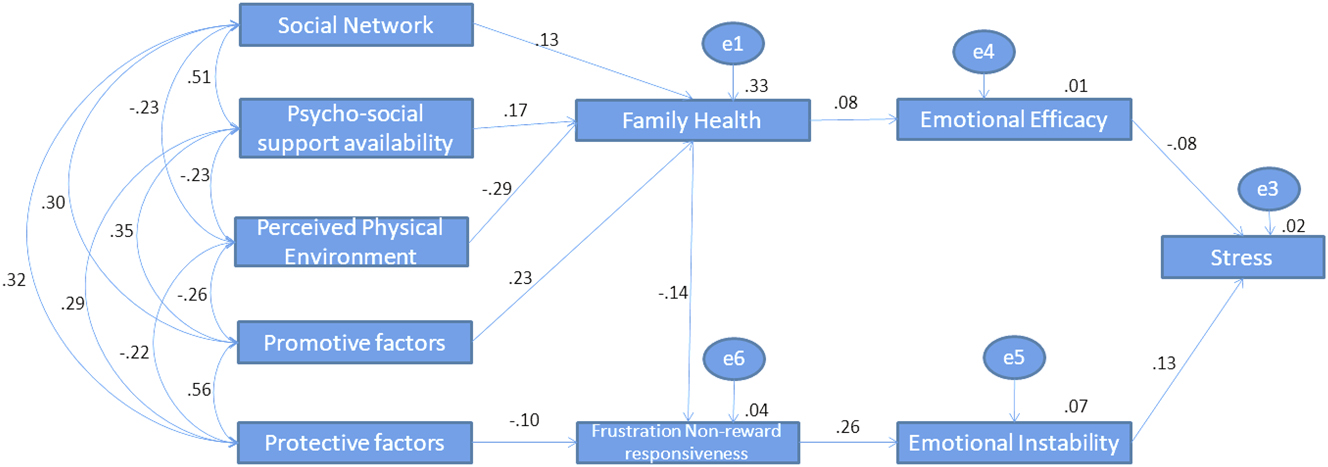

Model confirmation. The hypothetical model was tested for confirmation by examining the direction and significance of the pathways. Necessary modifications were made to arrive at the final structural model, which is presented in Figure 2.

Serial mediation path model.

In the final model, social networks, psychosocial support availability, perceived physical environment, and promotive factors were the independent variables that contributed to family health, which acted as a mediator for stress. Family health was directly related to emotional efficacy (mediator 2) and frustrative non-reward responsiveness (mediator 3). Protective factors also contributed to frustrative non-reward responsiveness, which further influenced emotional instability (mediator 4). Both mediators 3 and 4 had direct relationships with the dependent variable, stress.

The standardized estimates for all pathways are presented in Table 4.

Estimates, standard errors, and critical ratios for a structural path model.

| Path | Estimate | S. E | C.R. | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social network → family health | 0.13 | 0.187 | 4.58 | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial support availability → family health | 0.17 | 0.178 | 5.86 | <0.001 |

| Perceived physical environment → family health | −0.29 | 0.053 | −11.30 | <0.001 |

| Promotive factors → family health | 0.23 | 0.023 | 8.43 | <0.001 |

| Protective factors → frustration non-reward responsiveness | −0.10 | 0.003 | −3.26 | <0.001 |

| Family health → frustration non-reward responsiveness | −0.14 | 0.005 | −4.65 | <0.001 |

| Family health → emotional efficacy | 0.08 | 0.009 | 2.53 | <0.01 |

| Frustration non-reward responsiveness → emotional instability | 0.26 | 0.067 | 8.81 | <0.001 |

| Emotional efficacy → stress | −0.08 | 0.144 | −2.55 | <0.01 |

| Emotional instability → stress | 0.13 | 0.111 | 4.44 | <0.001 |

-

S. E, standard error, C.R., critical ratio.

The serial mediation model revealed significant pathways linking psychosocial factors to adolescent stress. Social networks positively influenced family health (β=0.13, p<0.001), as did psychosocial support availability (β=0.17, p<0.001). Conversely, perceived physical environment negatively affected family health (β=−0.29, p<0.001), indicating that adverse environmental perceptions reduced family health. Promotive factors also contributed positively to family health (β=0.23, p<0.001). Protective factors decreased frustrative non-reward responsiveness (β=−0.10, p<0.001), which was further reduced by better family health (β=−0.14, p<0.001). Family health positively influenced emotional efficacy (β=0.08, p<0.01), which directly reduced stress (β=−0.08, p<0.01), explaining 8 % of the variance. Frustrative non-reward responsiveness increased emotional instability (β=0.26, p<0.001), which in turn increased stress (β=0.13, p<0.001), explaining 13 % of the variance. The model’s fit indices supported its adequacy: χ2=162.813 (df=25, p=0.00), χ2/df=6.513, AGFI=0.939, CFI=0.923, RMSEA=0.071, and PCLOSE=0.000. While the ideal χ2/df is 5 or below, a value of 6.5 is acceptable given the large sample size [29]. Values of AGFI and CFI above 0.90, and RMSEA below 0.08, indicate good model fit. Thus, the model was considered acceptable.

The indirect effects of psychosocial factors on adolescent stress, as presented in Table 5, were also analyzed through the serial mediation model. All indirect effects were statistically significant (p<0.001). Specifically, social networks (β=−0.001), psychosocial support availability (β=−0.002), promotive factors (β=−0.002), protective factors (β=−0.003), and family health (β=−0.011) exhibited negative indirect effects, indicating that increases in these factors were associated with reduced stress levels. Conversely, perceived physical environment (β=0.003) and frustrative non-reward responsiveness (β=0.034) showed positive indirect effects, suggesting that higher levels of these factors were linked to increased stress. Although these indirect effects accounted for a small proportion of the variance, their significance was supported by 95 % confidence intervals that excluded zero [27]. These findings confirm partial mediation within the model, with both direct and indirect pathways contributing significantly to adolescent stress.

Indirect effects, lower bounds and upper bounds at 95 % confidence interval.

| Indirect paths | Indirect effect | Lower bound 95 % CI | Upper bound 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social network → stress | −0.001a | −0.003 | −0.001 |

| Psychosocial support availability → stress | −0.002a | −0.004 | −0.001 |

| Perceived physical environment → stress | 0.003a | 0.001 | 0.006 |

| Promotive factors → stress | −0.002a | −0.005 | −0.001 |

| Protective factors → stress | −0.003a | −0.007 | −0.001 |

| Family health → stress | −0.011a | −0.02 | −0.005 |

| Frustrative non-reward responsiveness → stress | 0.034a | 0.018 | 0.052 |

-

ap<0.001.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify factors predicting adolescent stress through hierarchical multiple regression and serial mediation modeling using path analysis. The findings are discussed in two sub-sections.

Hierarchical multiple regression

The final regression model revealed that ill health experiences, conscientiousness, emotional instability, and psychosocial support significantly predicted stress. Among these, emotional instability had the strongest association. However, these factors collectively explained only 6 % of the variance, suggesting that other important contributors to adolescent stress were not captured in this study.

Consistent with prior research, frustrative non-reward responsiveness and emotional instability are highly associated with negative affect. Frustration arises when adolescents do not receive expected rewards, leading to dissatisfaction and increased distress [30], 31]. Chronic stress can also negatively impact physical health, causing distress that exacerbates stress levels. Although conscientiousness is often considered protective against stress [32], high levels of conscientiousness may lead to overthinking and heightened stress due to self-imposed pressure for perfection. Emotional instability emerged as the strongest predictor reflecting a small-to-moderate effect size consistent with prior studies [33], [34], [35]; who reported similar effect sizes for emotional instability in adolescent stress. Ill health experiences and conscientiousness also showed small effect sizes, aligning with Bartley and Roesch's study [32], who noted conscientiousness effects ranging from β=0.10 to 0.14. Psychosocial support had a comparable effect, though its positive association with stress was unexpected, as discussed below.

Interestingly, the study found that psychosocial support positively predicted stress, which contradicts some previous findings. For instance Cohen and Wills [36] suggested that social support typically buffers stress, but they also noted that it can increase stress when perceived as burdensome or imposing expectations of reciprocity. The dynamics of social support have changed in recent years, with increased nuclear families and virtual social networks. High availability of virtual support may not translate to actual support, leading to elevated stress perception. For adolescents striving for autonomy, unsolicited support can be perceived as intrusive. Rui et al. [37] found that unsolicited or intrusive support, such as excessive parental monitoring, can heighten adolescent stress by undermining autonomy. Barrera [38] further observed that a discrepancy between perceived and actual support availability may lead to increased stress when adolescents’ expectations are unmet. These findings suggest that, in the context of this study, psychosocial support may have been perceived as intrusive or inadequate, contributing to elevated stress levels among adolescents striving for independence.

Serial mediation model

The serial mediation analysis revealed partial mediation through family health, frustrative non-reward responsiveness, emotional efficacy, and emotional instability, each exerting significant direct and indirect effects on adolescent stress. The path model showed that social networks, psychosocial support availability, perceived physical environment, and promotive factors influenced family health, which in turn shaped frustrative non-reward responsiveness and emotional efficacy. Protective factors mitigated frustrative non-reward responsiveness, which, when heightened, increased emotional instability, thereby elevating stress levels. In contrast, emotional efficacy reduced stress exhibiting a small but significant effect consistent with Muris [17], while emotional instability amplified stress reflecting a small-to-moderate effect size comparable to previous findings [10] (β=0.16).

Two primary pathways emerged from the model. The first pathway linked social networks, psychosocial support availability, perceived physical environment, and promotive factors to family health, which subsequently influenced emotional efficacy and consequently, stress. Family health served as a critical mediator, with secure relationships and resource availability fostering emotional awareness among adolescents [39]. Supportive parent-child relationships, indicative of positive family functioning, can buffer the impact of stressful events, as supported by Masten and Narayan [40] and Prime et al. [41]. The second pathway demonstrated that protective factors diminished frustrative non-reward responsiveness, which in turn reduced emotional instability, thereby lowering stress. Among indirect effects, frustrative non-reward responsiveness showed the strongest association with stress underscoring its pivotal role in stress pathways [42].

Despite the model’s low explained variance (6 %), the identified psychosocial factors contribute meaningfully to understanding adolescent stress. Human studies often exhibit greater unexplained variation due to the complexity of human behavior, yet significant predictors remain valuable.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Its cross-sectional design constraints causal inferences about the relationships between psychosocial factors and stress. The sample, drawn from India may restrict generalizability to other cultural contexts. Reliance on self-report measures introduces potential bias, and the modest explained variance suggests that unexamined factors, such as genetic predispositions or broader environmental influences, likely play substantial roles. Adolescent stress is a multifaceted and dynamic phenomenon, shaped by diverse life aspects that drive individual differences in perception, reactivity, and coping. Despite the low explained variance, the significant role of psychosocial factors in this study remains crucial and warrants further exploration.

Conclusions

This study highlights the roles of emotional instability, ill health experiences, and social support dynamics in predicting adolescent stress among Indian adolescents. The findings underscore complex pathways, with family health and frustrative non-reward responsiveness as partial mediators. Interventions targeting emotional regulation and family-based programs may reduce stress, while efforts to enhance in-person social relationships could address the limitations of virtual support. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs, diverse samples, and objective measures to identify additional contributors to adolescent stress, building on these insights to inform effective interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants of this study.

-

Research ethics: This study has obtained ethical clearance from Institutional Ethics Committee, University of Hyderabad (Ref. No UH/IEC/2021/174).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The data will be made available by authors upon reasonable request.

References

1. Frost, A, Hoyt, LT, Chung, AL, Adam, EK. Daily life with depressive symptoms: gender differences in adolescents’ everyday emotional experiences. J Adolesc 2015;43:132–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Larson, RW, Moneta, G, Richards, MH, Wilson, S. Continuity, stability, and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Dev. 2002;73:1151–65.10.1111/1467-8624.00464Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Clark, DA, Donnellan, MB, Durbin, CE, Nuttall, AK, Hicks, BM, Robins, RW. Sex, drugs, and early emerging risk: examining the association between sexual debut and substance use across adolescence. PLoS One 2020;15:e0228432. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228432.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Hossainkhani, Z, Hassanabadi, HR, Parsaeian, M, Karimi, M, Nedjat, S. Academic stress and adolescents’ mental health: a multilevel structural equation modeling study. J Res Health Sci 2020;20:e00496. https://doi.org/10.34172/jrhs.2020.30.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Safta, CG. Career decisions – a test of courage, responsibility, and self-confidence in teenagers. Proced Soc Behav Sci 2015;203:341–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.305.Suche in Google Scholar

6. National Crime Records Bureau. Crime in India 2020: statistics. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

7. World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2021: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240076846.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Lecic-Tosevski, D, Vukovic, O, Stepanovic, J. Stress and personality. Psychiatriki 2011;22:290–7.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Gillihan, SJ. Which personality types are the best at dealing with stress? Psychol Today 2023. https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/think-act-be/202310/which-personality-types-are-the-best-at-dealing-with-stress.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Luo, J, Zhang, B, Cao, M, Roberts, BW. The stressful personality: a meta-analytical review of the relation between personality and stress. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2023;27:128–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/10888683221104002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Brose, A. Personality and stress. In: Rauthmann, JF, editor. The handbook of personality dynamics and processes. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2021: 1209–29 pp.10.1016/B978-0-12-813995-0.00047-9Suche in Google Scholar

12. Ancel George, H, van den Berg, H. The experience of psychosocial stressors amongst adolescent learners. J Psychol Afr 2011;21:521–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2011.10820492.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Gonmei, J, Devindiran, C. Perceived stress and psychosocial factors of stress among youth. Int J Acad Res Dev 2017;2:766–70.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Smith, K. 6 Common triggers of teen stress. Psycom 2022. https://www.psycom.net/common-triggers-teen-stress.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Kumar, V, Talwar, R. Determinants of psychological stress and suicidal behavior in Indian adolescents: a literature review. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health 2014;10:47–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973134220140104.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Hariharan, M, Padhy, M, Monteiro, SR, Nakka, LP, Chivukula, U. Adolescence Stress Scale: development and standardization. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health 2023;19:197–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/09731342231173214.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Muris, P. A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2001;23:145–9. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010961119608.10.1023/A:1010961119608Suche in Google Scholar

18. Rosenberg, M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; 1965.10.1515/9781400876136Suche in Google Scholar

19. Barbaranelli, C, Caprara, GV, Rabasca, A, Pastorelli, C. A questionnaire for measuring the Big Five in late childhood. Pers Indiv Differ 2003;34:645–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00051-X.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Wright, HR, Lam, C, Brown, J. Behavioural approach system (BAS) and behavioural inhibition system (BIS); 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Padhy, M, Hariharan, M. Social skill measurement: standardization of scale. Psychol Stud 2023;68:114–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-022-00693-4.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Crandall, C, Wainwright, M, Menzies, V. Measuring family health resources: a revision of the family health questionnaire. J Fam Psychol 2020;34:717–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000649.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Padhy, M, Hariharan, M, Monteiro, SR, Kavya, C, Angiel, PR. The psycho-social support scale (Psychoss-22): development and validation. Indian J Soc Work 2022;83:95–114.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Rajendran, A, Hariharan, M, Rao, CR. A holistic approach to measuring resilience: development and Initial validation of resilience test Battery. Int J Humanit Soc Sci Stud (IJHSSS) 2019;6:52–64.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Aiken, LS, West, SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Collier, DA. Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods, 5th ed. Cengage Learning; 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Comrey, AL, Lee, HB. A first course in factor analysis, 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Schumacker, E, Lomax, G. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modelling, 4th ed. London, New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.10.4324/9781315749105Suche in Google Scholar

30. Baskin-Sommers, A, Curtin, JJ, Newman, JP. Specifying the attentional selection that moderates the fearlessness of psychopathic offenders. Psychol Sci 2012;23:673–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611436343.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Vasile, C, Albu, G. Adolescence and stress. Proced Soc Behav Sci 2011;30:1880–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.363.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Bartley, CE, Roesch, SC. Coping with daily stress: the role of conscientiousness. Pers Individ Differ 2011;50:79–83.10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.027Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Piekarska, J. Determinants of perceived stress in adolescence: the role of personality traits, emotional abilities, trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. Adv Cogn Psychol 2020;16:309.10.5709/acp-0305-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Yang, Y, Wang, J, Lin, H, Chen, X, Chen, Y, Kuang, J, Yao, Y, Wang, T, Fu, C. Emotion dynamics prospectively predict depressive symptoms in adolescents: findings from intensive longitudinal data. BMC psychol 2025;13:1–2.10.1186/s40359-025-02699-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Bailen, NH, Wu, H, Thompson, RJ. Meta-emotions in daily life: associations with emotional awareness and depression. Emotion 2019;19:776.10.1037/emo0000488Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Cohen, S, Wills, TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 1985;98:310.10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.310Suche in Google Scholar

37. Rui, Y, Guo, J, Green, E. The paradox of social support: how can support increase stress? Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2022;19:2813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052813.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Barrera, M. Social support research in community psychology. In: Rappaport, J, Seidman, E, editors. Handbook of community psychology. Springer; 2000:215–45 pp.10.1007/978-1-4615-4193-6_10Suche in Google Scholar

39. Bhatia, MS. Essentials of psychiatry. CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd.; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Masten, AS, Narayan, AJ. Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: pathways of risk and resilience. Annu Rev Psychol 2012;63:227–57. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100356.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Prime, H, Wade, M, Browne, DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol 2020;75:631–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Rentala, S, Lau, BH, Chan, ML, et al.. Emotional instability and stress among adolescents: the mediating role of frustration. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2019;24:252–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12345.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Physical Activity, Sleep, and Lifestyle Behaviours

- Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its association with hypertension among young adults in urban Meghalaya: a cross sectional study

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Psychosocial predictors of adolescent stress: insights from a school-going cohort

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Barriers and facilitators in the transition from pediatric to adult care in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe – a qualitative systematized review

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Self-care or self-risk? examining self-medication behaviors and influencing factors among young adults in Bengaluru

- Health Equity and Access to Care

- Clinical heterogeneity of adolescents referred to paediatric palliative care; a quantitative observational study

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- ‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Physical Activity, Sleep, and Lifestyle Behaviours

- Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its association with hypertension among young adults in urban Meghalaya: a cross sectional study

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Psychosocial predictors of adolescent stress: insights from a school-going cohort

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Barriers and facilitators in the transition from pediatric to adult care in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe – a qualitative systematized review

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Self-care or self-risk? examining self-medication behaviors and influencing factors among young adults in Bengaluru

- Health Equity and Access to Care

- Clinical heterogeneity of adolescents referred to paediatric palliative care; a quantitative observational study

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- ‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping