Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

-

Ahmad Bin Aamir

, Joory Osamah Fallatah

Abstract

Following prospective registration (PROSPERO CRD42024564275), three databases (PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science) were searched for trials reporting the effects of anti-obesity drugs (AODs) (with placebo as control) on cardiometabolic risk factors in the pediatric population with obesity. Data was synthesized using RStudio within a Random effect model. Risk of Bias was assessed through the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool. Five clinical trials fulfilled the eligibility criteria. Pooled estimates showed significant reductions in triglycerides [−13.84 mg/dl (CI: −26.46 to −1.21; p 0.03) (I2 93 %, p<0.01), Systolic blood pressure [−1.49 mmHg (CI: −2.77 to −0.21; p 0.02) (I2 0 %, p 0.61)], and Waist circumference [−6.55 cm (CI: −10.56 to −2.55; p<0.01) (I2 93 %, p<0.01)]. Fasting glucose, Insulin, Insulin resistance, Glycated hemoglobin, Diastolic blood pressure, Total cholesterol, Low density lipoproteins, High density lipoproteins, Very low density lipoproteins, and C-Reactive Protein showed insignificant reductions. No significant publication bias was detected in any outcome except Waist circumference (p 0.03).

Introduction

As per the World Health Organization fact sheet (2024) [1], obesity has increased in children and adolescents aged 5–19 from just 2 % in 1990 to 8 % by 2022. Lifestyle modification is the main weight management approach for obese children and adolescents. However, the impact of such behavioral interventions on body weight status is often limited and there is a need for adjunctive therapies such as anti-obesity drugs (AODs) for patients who are unable to lose sufficient weight with lifestyle interventions alone [2], 3].

Currently, there are four AODs authorized by the US FDA (Food and Drug Administration) for use in children and adolescents with obesity; Orlistat [3], Phentermine-topiramate [4], Liraglutide [5], Semaglutide [6]. FDA approved a drug named Setmelanotide as well for children≥6 years of age for unique genetic disorders producing obesity [7].

Orlistat inhibits gastrointestinal lipase and decreases 30 % of fat absorption [8]. Phentermine is a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor that decreases appetite and leads to satiety [9]. Topiramate enhances GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) activity and inhibits carbonic anhydrase [10]. Combining Phentermine-topiramate enables weight loss at a low dosage due to complementary mechanisms, at maximum safety and tolerability [11], 12]. Liraglutide and Semaglutide are GLP-1 receptor agonists [13], [14], [15]. Their weight control mechanism reduces hunger by acting on the CNS and slows down gastric emptying [16].

Previous meta-analysis (MA) analyzed the effects of pediatric AOD on body mass index (BMI) and quality of life but not on CRFs [17], 18]. A systematic review (SR) and MA published in 2010 analyzed the effects of AODs on cardiometabolic risk factors (CRFs) in pediatric obese subjects [19]. They included eight trials; five on Orlistat and 3 trials on Sibutramine. Sibutramine is not an FDA-approved drug for pediatric obesity. After 2010, the FDA approved three more AODs for pediatric obesity (Liraglutide, Semaglutide, and Phentermine) [4], [5], [6]. Given the approval of three new AODs, the exponential increase in childhood obesity, and its associated acute and chronic comorbidities, we considered it timely to conduct an updated SR and MA which analyzed the impact of FDA-approved pediatric AODs on CRFs in children/adolescents with obesity.

Methodology

This review was conducted according to the methods in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-2020 statement and its extensions [20], [21], [22]. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (Registration number CRD42024564275 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42024564275).

Electronic search

Three databases Medline, SCOPUS, and Web of Science (WOS) were searched by the search themes/key concepts as 1) Obesity 2) Anti-obesity drugs 3) Adolescents 4) Cardiometabolic risk factors 5) Randomized controlled trials. The search phrases for themes 1–5 were combined using the AND Boolean operator.

The complete search strategy and the results yielded have been provided in the supplementary file (Table S1). Two authors screened studies independently according to the predefined eligibility criteria.

Eligibility criteria

All completed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting effects of AOD (with placebo as control) on at least one of the selected CRFs outcomes in the pediatric population with obesity, in the English language regardless of their publication status were eligible for this meta-analysis.

Inclusion criteria

Population: Children or adolescents (less than 19 years of age) diagnosed with pediatric obesity (i.e. who have BMI of 95th percentile for their age and gender) with or without co-morbidities.

Intervention: FDA-approved AODs for pediatric obesity (Orlistat, Phentermine-Topiramate, Semaglutide, Liraglutide, setmelanotide). The intervention duration must be≥12 weeks. Co-interventions such as diet and exercise (if any) must be the same in experimental and placebo groups.

Comparator: Placebo

Outcome: Outcomes of interest were any of the CRFs [Waist circumference, Systolic/diastolic blood pressure, Lipid Profile, Fasting plasma glucose/Insulin, Insulin resistance, Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c %), C-Reactive Protein (CRP) etc.]. The study reporting at least one of the above-mentioned CRFs as either “post-intervention” or “change from baseline” values for both intervention and comparator groups were eligible.

Study Design: Randomized controlled trial

Exclusion criteria

Trials with follow-up duration less than 12 weeks

Trials not reporting the relevant CRFs as “post-intervention” or “change from baseline” values for both intervention and comparator groups

Trials of medications approved for purposes other than obesity in children/adolescents e.g. Metformin because Metformin is approved as an anti-diabetic drug in children/adolescents.

Non-human, observational studies

The bibliography of all the included studies was explored manually for additional publications.

Risk of bias

Risk of Bias (RoB) was assessed through Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (ROB-2) tool and categorized as “high,” “low,” or “some concern” [23]. Conflicts and disagreements were resolved through discussions.

Publication bias

The publication bias was assessed by funnel plot symmetry.

Two authors conducted the literature search, data extraction, and RoB estimation and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Data synthesis was carried out RStudio using meta and metafor packages. Since CRFs data were continuous, Mean Differences with 95 % CIs were calculated by random-effects model to estimate the effects of AODs on CRFs. The heterogeneity of treatment effects between studies/study variability was investigated statistically by the I2 statistic. All p values less than 0.05 were significant. Publication bias was detected statistically by Egger’s regression asymmetry test. To ensure the robustness of the data, sensitivity analysis was done.

Results

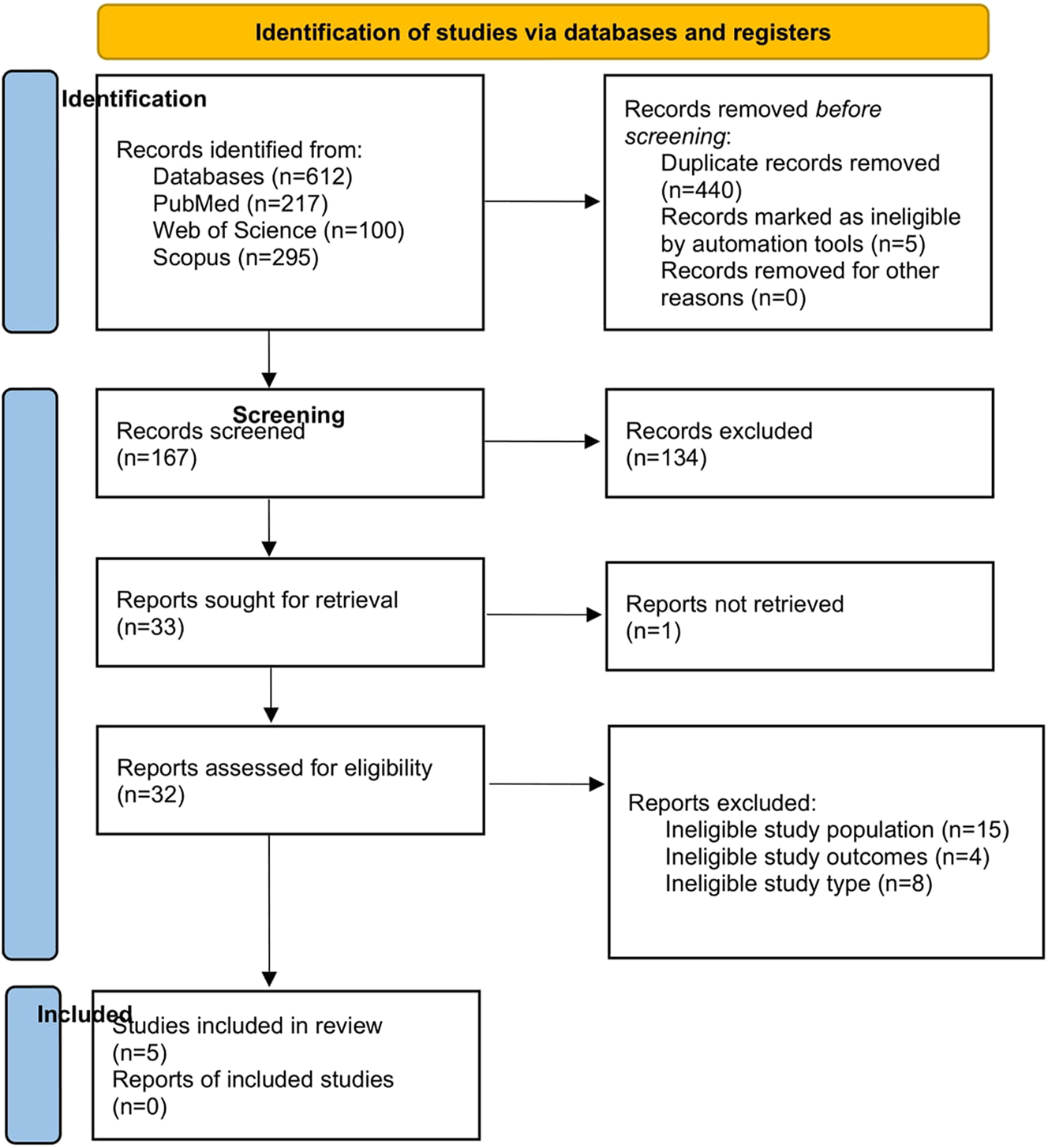

Preliminary electronic search yielded 612 potential articles (PubMed=217; Web of Science=100; Scopus=295). After removing duplicates and title and abstract screening, 33 studies were retrieved for detailed assessment and five randomized controlled trials [24], [25], [26], [27], [28] met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The study characteristics are in Table 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study ID | Country, time period, industry funding (Y/N/NR) protocol registration (number/NR) | Study population (baseline) (PP) | Intervention: Drug component (Route, frequency, total dose/d, duration Comparators: (Route, frequency, total dose/d, duration |

Number of participants randomized/completed | Inclusion criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) Mean ± SD |

Age, years Mean ± SD |

Female gender n, % | |||||

| Chanoine et al. [24] | US, Canada Aug 2000 – Aug 2002, Y, NR |

D: 35.7 ± 4.2 P: 35.4 ± 4.1 |

D: 13.6 (1.3) P: 13.5 (1.2) |

D: 228 (65) P: 129 (71) |

Drug: Orlistat, oral, 120 mg 3 times a day for 52 weeks Placebo: oral, 120 mg 3 times daily for 52 weeks |

D: 357/232 P: 182/117 |

|

| Kelly et al. [25] | Belgium, Mexico, Russia, Sweden, US Sep 2016-Aug 2019, Y, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02918279 |

D: 35.3 ± 5.1 P: 35.8 ± 5.7 |

D: 14.6 ± 1.6 P: 14.5 ± 1.6 | D: 71 (56.8) P: 78 (61.9) |

Drug: Liraglutide, subcutaneous, 3 mg, once daily for 56 weeks (including dose escalation period of 4–8 weeks). Placebo: subcutaneous, 3 mg, once daily for 56 weeks |

D:125/101 P:126/100 |

|

| Kelly et al. [26] | US May 2019-Apr 2021, Y, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03922945 |

Mid dose D: 36.9 ± 6.8 P: 36.4 ± 6.4 |

Mid dose D: 14.1 ± 1.28 P: 14.0 ± 1.41 |

Mid dose D: 28 (51.9) P: 30 (53.6) |

Mid dose Drug: Phentermine/Topiramate, oral, 7.5 mg/46 mg, once daily for 56 weeks Placebo: oral, once daily for 56 weeks. |

Mid dose D: 54/37 P: 56/29 |

|

| Top dose D: 39.0 ± 7.4 P: 36.4 ± 6.4 |

Top dose D: 13.9 ± 1.36 P: 14.0 ± 1.41 |

Top dose D: 63 (55.8) P: 30 (53.6) |

Top dose Drug: Phentermine/Topiramate, oral, 15 mg/92 mg, once daily for 56 weeks Placebo: oral, once daily for 56 weeks. |

Top dose D: 113/73 P: 56/29 |

|||

| Maahs et al. [27] (3 months, 6 months) | New Mexico Dec 2002-Sep 2003, N, NR |

D: 39.2 ± 5.3 P: 41.7 ± 11.7 |

D: 15.8 ± 1.5 P: 15.8 ± 1.4 |

D: 12 (60) P: 15 (75) |

Drug: Orlistat, oral, 120 mg 3 times daily for 12 weeks Placebo: oral, 120 mg 3 times daily for 12 weeks |

D: 20/16 P: 20/18 |

|

| Drug: Orlistat, oral, 120 mg 3 times daily for 24 weeks Placebo: oral, 120 mg 3 times daily for 24 weeks |

|||||||

| Weghuber et al. [28] | US, Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Ireland, Mexico, Russian Federation, UK. Oct 2019-Mar 2022 Y, ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04102189 |

D: 37.7 ± 6.7 P: 35.7 ± 5.4 |

D: 15.5 ± 1.5 P: 15.3 ± 1.6 |

D: 84 (63) P: 41 (61) |

Drug: Semaglutide, subcutaneous, 2.4 mg once weekly for 68 weeks Placebo: subcutaneous, 2.4 mg once weekly for 68 weeks |

D: 134/120 P: 67/60 |

|

-

D, drug; P, placebo; Y, yes; N, no; NR, not reported. In all studies, study design is Double-blinded, Placebo-controlled Randomized controlled trial and co-intervention is Lifestyle modifications (Diet, Physical activity).

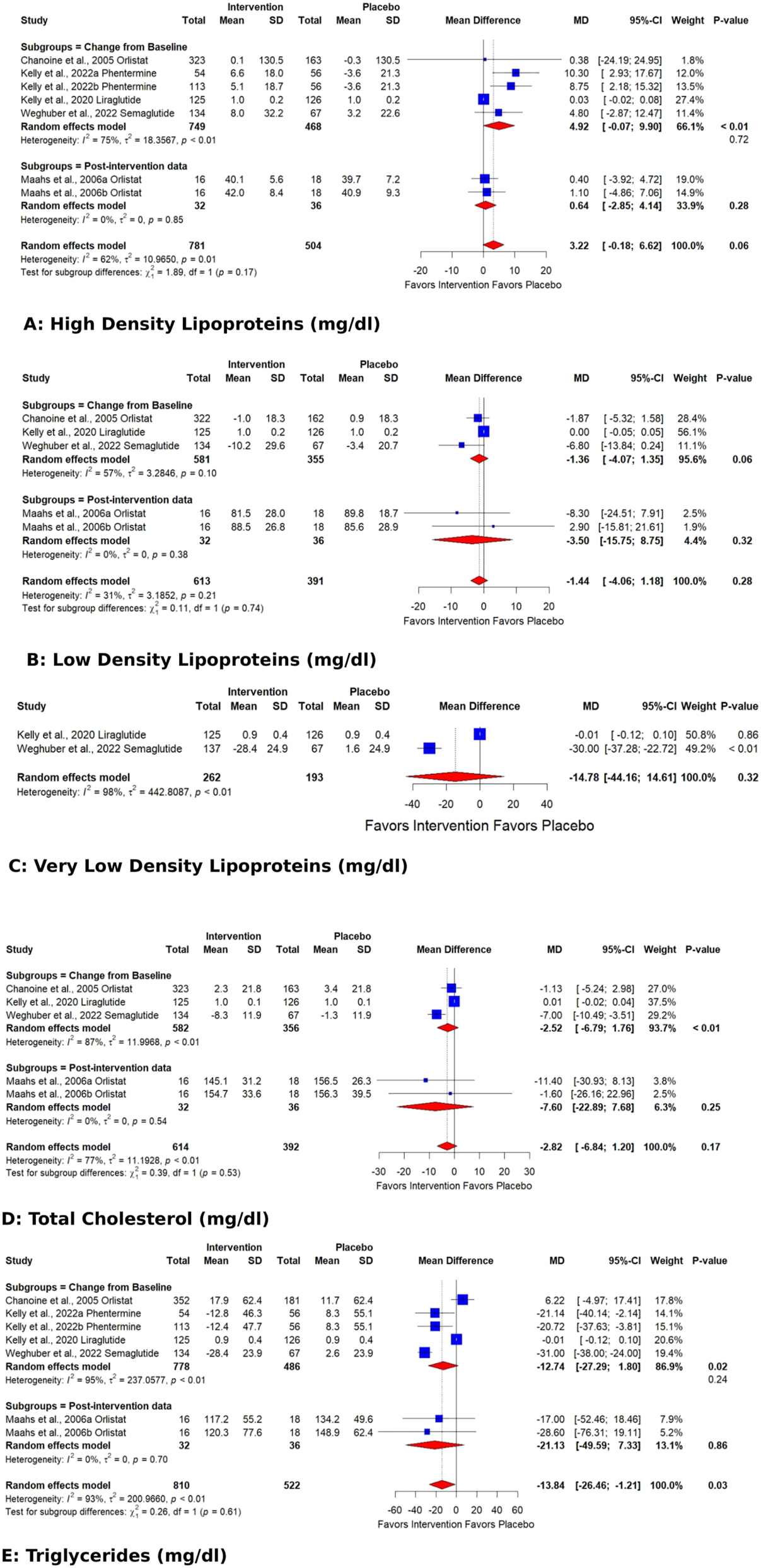

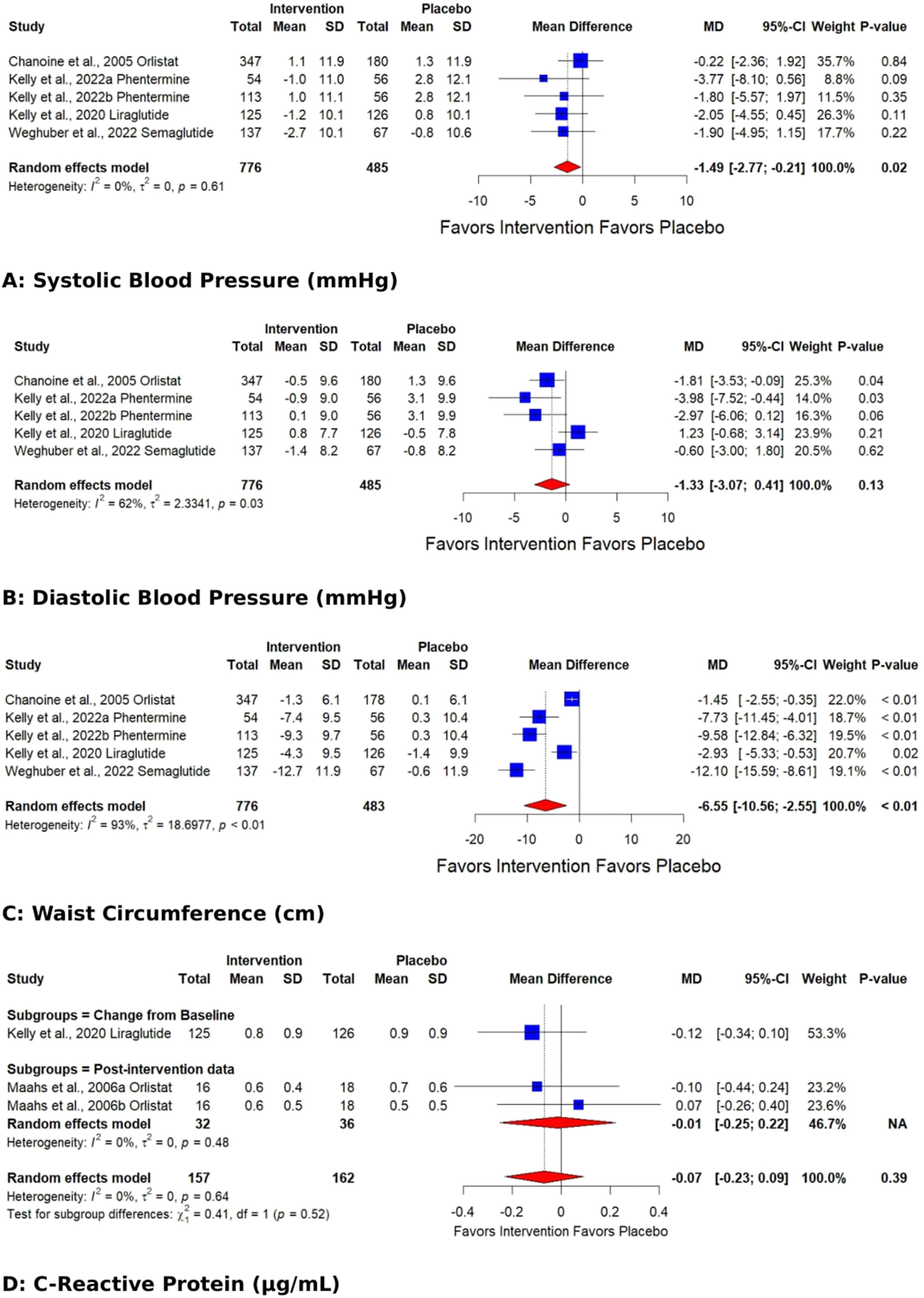

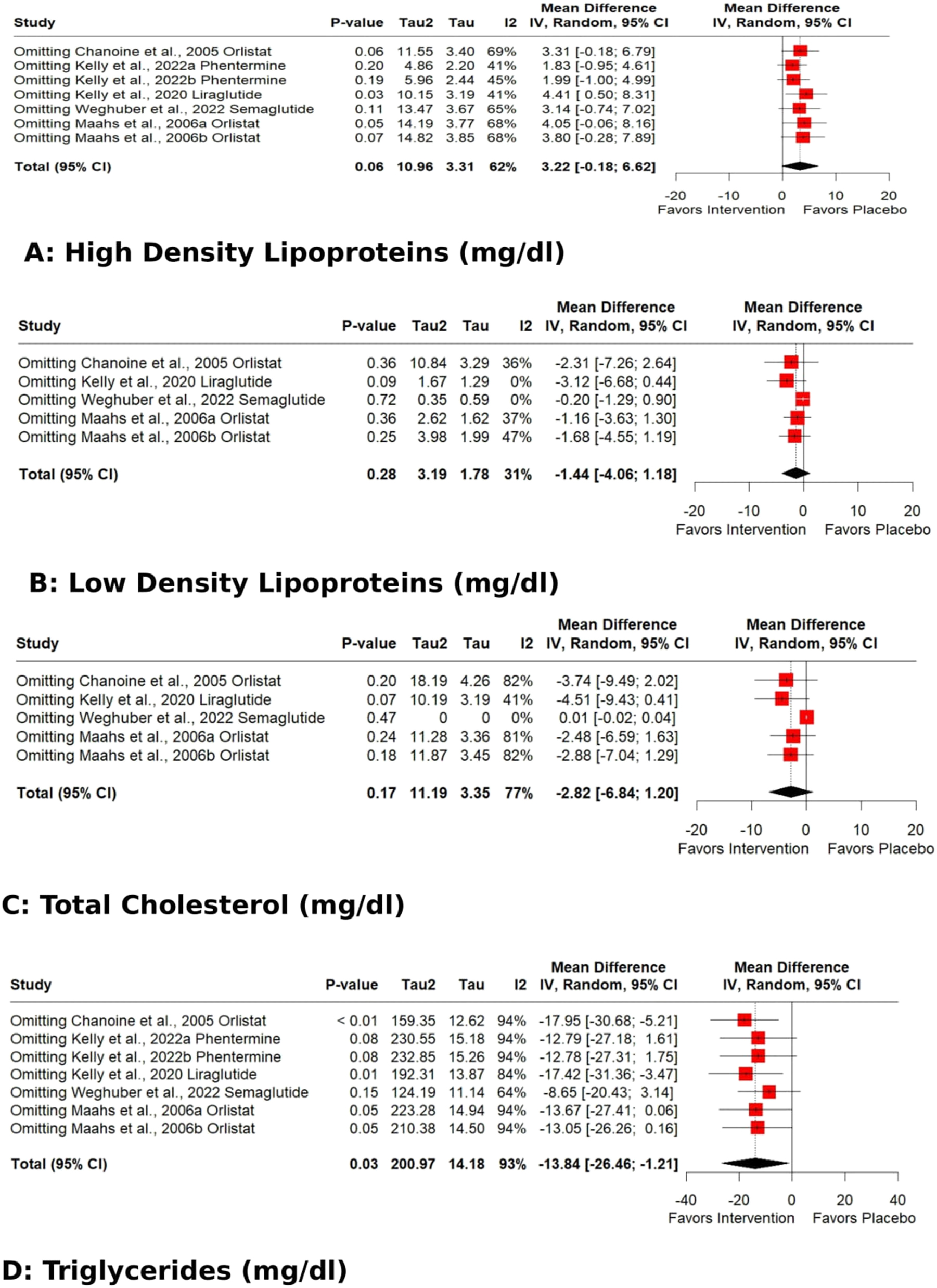

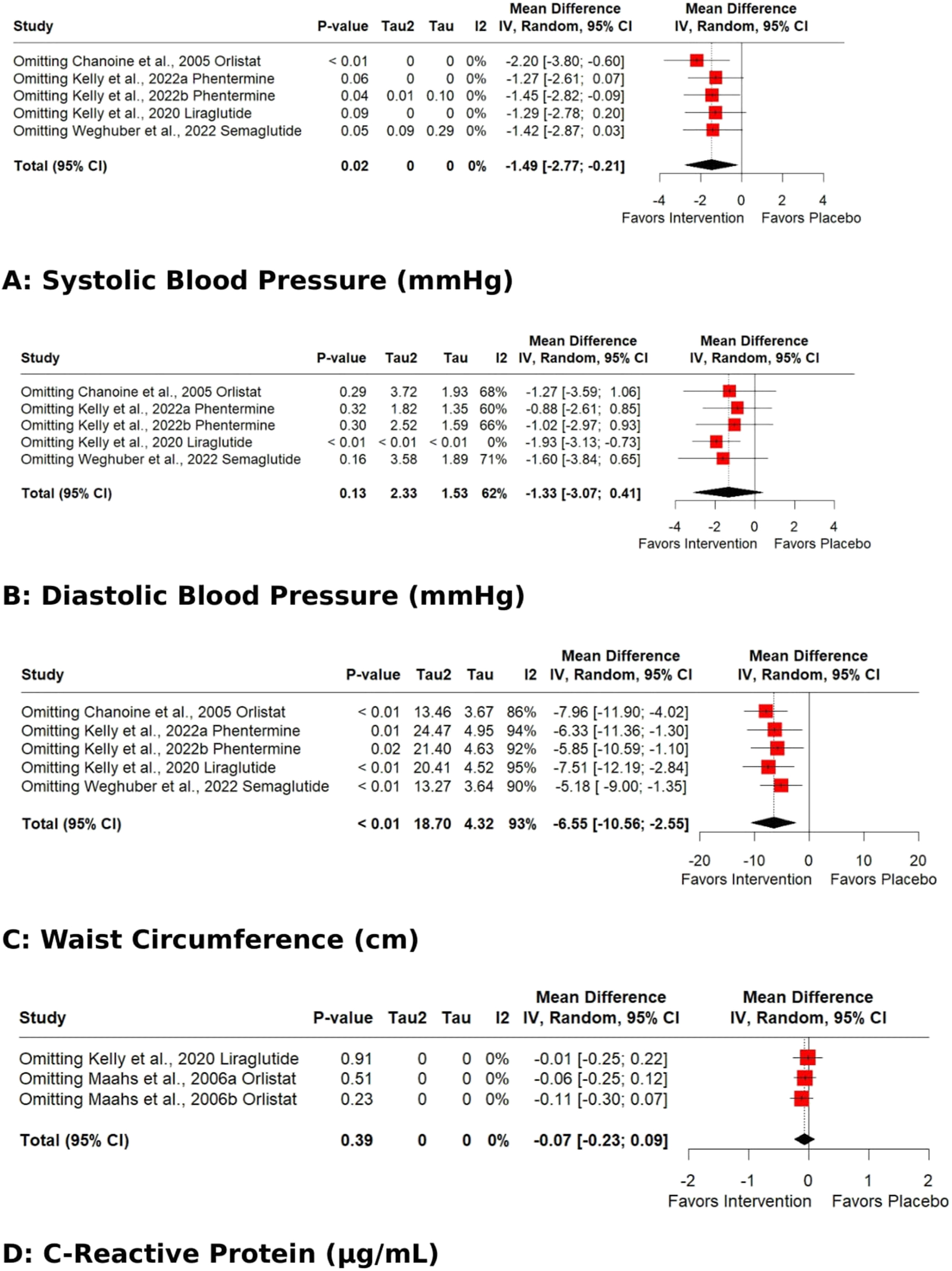

The outcomes whose pooled analysis showed a significant reduction by AOD in comparison to placebo were triglycerides [reduced by 13.84 (CI: −26.46 to −1.21; p 0.03; Figure 2)] with significant heterogeneity (I2 93 %, p<0.01), SBP [−1.49 mmHg (CI: −2.77 to −0.21; p 0.02; I2 0 %, p 0.61 Figure 3)], and waist circumference [reduced by 6.55 cm (CI: −10.56 to −2.55; p<0.01; I2 93 %, p<0.01; Figure 3)].

Forest plots showing the pooled estimates of the effects of anti-obesity drugs on lipid profile (A) high density lipoproteins B) low density lipoproteins (C) very low density lipoproteins (D) total cholesterol (E) triglycerides.

Forest plots showing the pooled estimates of the effects of anti-obesity drugs on (A) systolic blood pressure (B) diastolic blood pressure (C) waist circumference (D) C-reactive protein.

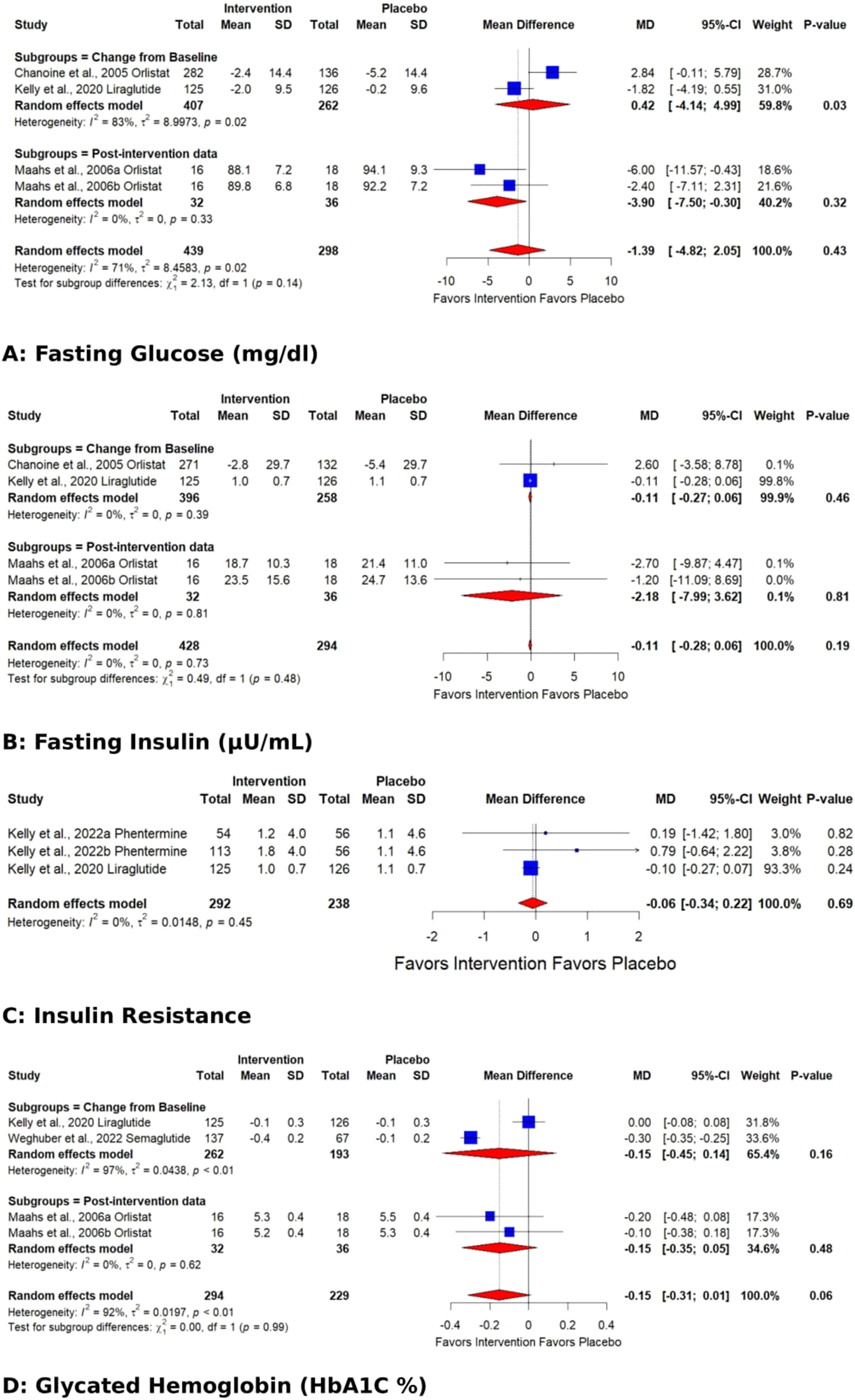

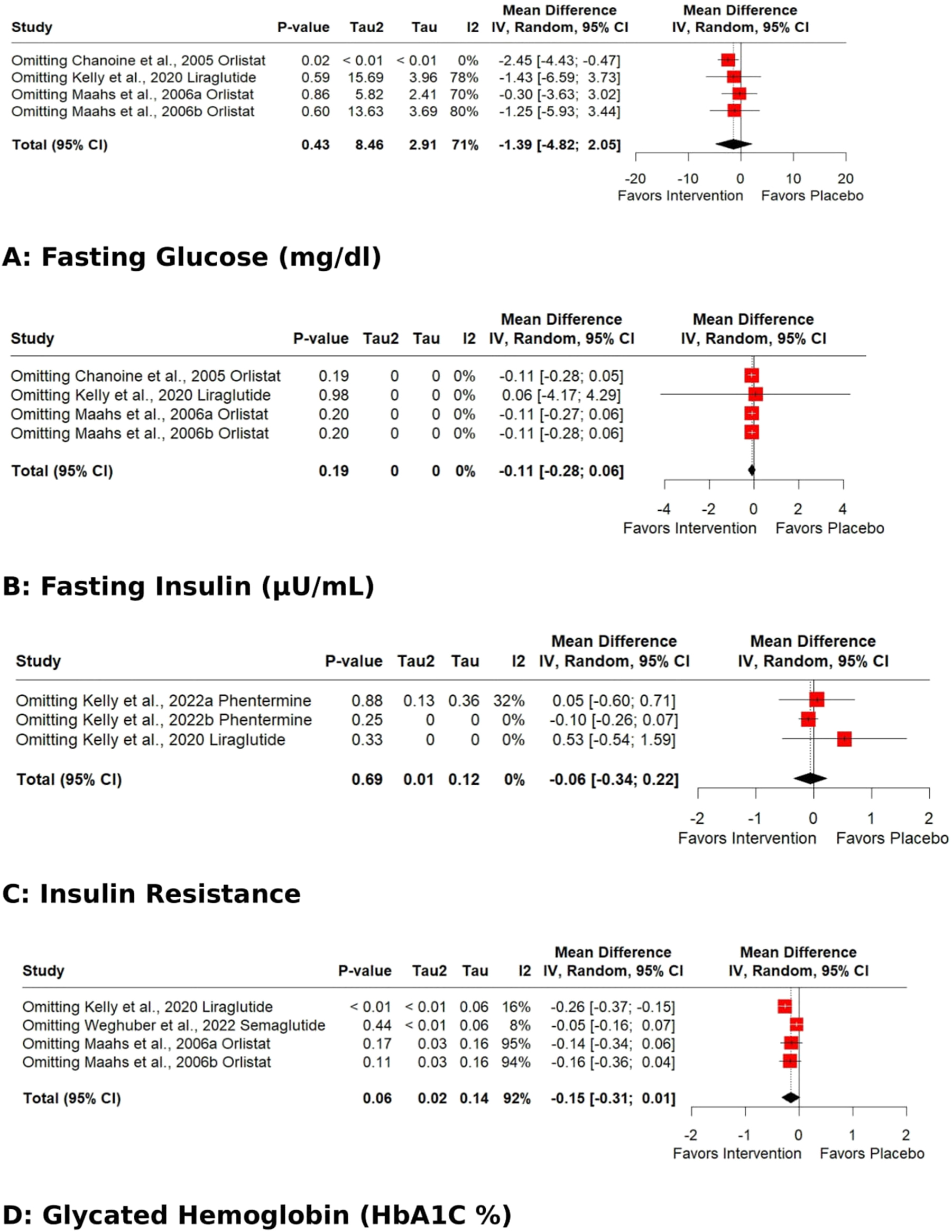

The remaining parameters decreased but could not reach the “significance” level. AOD-induced reductions in fasting glucose were 1.39 mg/dl (CI:−4.82 to 2.05); fasting insulin 0.11 µU/mL (CI:−0.28 to 0.06); Hb1AC % 0.15 (CI:−0.36 to 0.05); Insulin resistance 0.06 (CI:−0.34 to 0.22) (Figure 4) compared to placebo.

Forest plots showing the pooled estimates of the effects of anti-obesity drugs on glucose homeostasis (A) fasting glucose (B) fasting insulin (C) insulin resistance (D) glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C %).

The pooled effect for HDL, VLDL, Total cholesterol, TG, Fasting glucose, HbA1C %, DBP, and WC exhibited significant heterogeneity [I2=62 % (p 0.01), 98 % (p<0.01), 77 % (p<0.01), 93 % (p<0.01), 71 % (p 0.02), 92 % (p<0.01), 62 % (p 0.03), 93 % (p<0.01)]. Subgroup analysis based on the data type (change from baseline values or post-intervention values) revealed that the source of heterogeneity was the trials reporting change from baseline values. Trials reporting post-intervention values had I2 value 0 %. Sensitivity analysis showed that the exclusion of the study Kelly et al. 2020 [25] caused a significant increase in HDL (p 0.03; I2 41 %) (Figure 5) and a significant reduction in HbA1C % (p<0.01; I2 16 %) (Figure 6) and DBP (p<0.01; I2 0 %) (Figure 7). There was no evidence of heterogeneity for LDL, Fasting Insulin, Insulin resistance, SBP, and CRP (insignificant p values for I2).

Sensitivity analysis (Leave-one-out) of the effects of anti-obesity drugs on lipid profile (A) high density lipoproteins (B) low density lipoproteins (C) total cholesterol (D) triglycerides.

Sensitivity analysis (Leave-one-out) of the effects of anti-obesity drugs on glucose homeostasis (A) fasting glucose (B) fasting insulin (C) insulin resistance (D) glycated hemoglobin (Hb1AC).

Sensitivity analysis (Leave-one-out) of the effects of anti-obesity drugs on (A) systolic blood pressure (B) diastolic blood pressure (C) waist circumference (D) C-reactive protein.

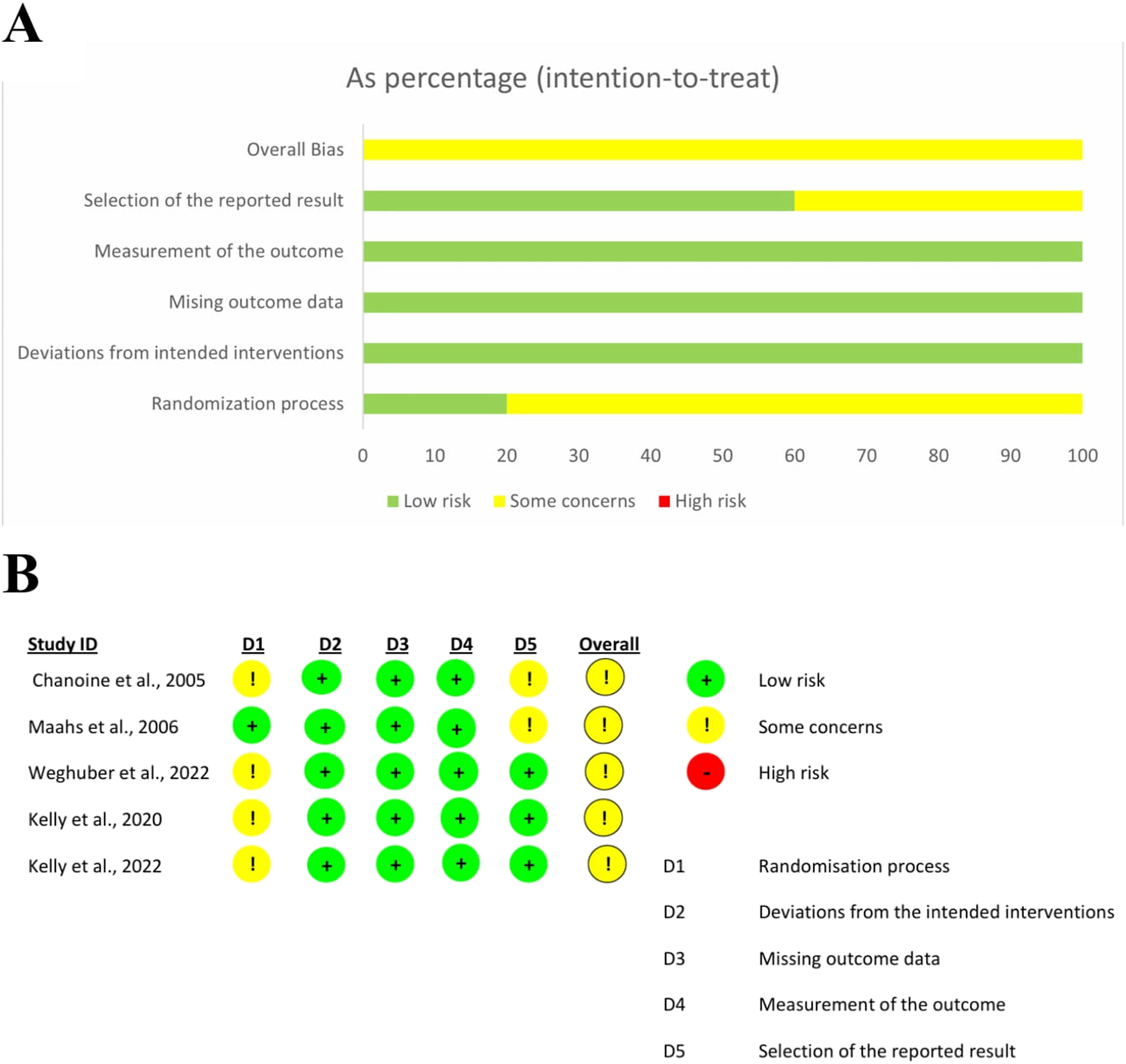

Risk of bias

Figure 8A and B represent the risk of bias in all studies and individual studies, respectively. The risk was low in all five risk assessment domains except in the “Randomization process” and “selection of the reported result” domains. In four trials, information about “Was the allocation sequence concealed until participants were enrolled and assigned to interventions?” was missing, leading to “some concerns” in the randomization process. In two trials, there were concerns about the “selection of the reported results.” Overall, there were “some concerns” in all trials.

(A) Risk of bias in all studies (B) risk of bias in individual studies.

Publication bias

Funnel plots have been given in the supplementary file (Figure S1 A-M). The Egger test calculated significance levels. No significant publication bias was detected in any outcome except WC (Egger regression asymmetry test p for WC=0.03). The Egger test was not conducted with the outcome of VLDL because of fewer studies (k=2).

Discussion

The current meta-analysis showed that AOD approved for use in the pediatric population significantly reduces triglycerides, SBP, and waist circumference. There was no evidence that AODs use caused any significant improvement in variables related to glucose homeostasis (fasting glucose, Insulin, Insulin resistance, HbA1c), DBP, Total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, VLDL or CRP.

Contrary to our results, Zhou et al. reported in their MA that AODs significantly reduced total cholesterol, LDL and fasting glucose [29]. No significant effect was observed on TG. The underlying reason for this apparent discrepancy could be the much shorter duration of the follow-ups/intervention in the trials included in the current MA [3–17 months (mean: 11 months) vs. 4–48 months (mean:14.7 months)] in MA by Zhou et al. [29] This may also be a drug-specific effect related to Orlistat because Zhou et al.’s MA included more Orlistat trials than other AODs (6 trials of Orlistat). Another reason could be the variations in age of the study participants. In 15 out of 21 trials included in Zhou’s MA, participants’ mean age was≥40.6 years (n: 12,047) and 5 trials involved adolescents (mean age 13.6–16.2 years; n: 1,225). Contrarily, all trials included in the current MA involved adolescents/pediatric populations. The effects of weight loss strategies in children or adolescents may differ from those produced in adults [30]. Hence, it could be assumed that the AOD-induced improvements in CVD risk factors may vary with study follow-up duration, drug type and participants’ age.

The AODs may not affect CRFs directly, but indirectly through reducing body weight. Weight loss reduces triglycerides, cholesterol, and fasting glucose in individuals who are overweight or obese [31], [32], [33]. Brown et al. observed the effects of a “lifestyle change program” on CRFs; and reported that the magnitude of risk factor improvement was associated with weight loss extent and the risk factor levels at the baseline [34]. A 10 % weight loss produced significant reductions in fasting glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol, 5–10 % weight loss improved triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol, and <5 % weight loss improved triglycerides only. Moreover, the CRFs attenuations were more pronounced when pre-intervention CRFs were at higher risk levels. Garvey et al. observed a decrease in SBP, DBP and hyperglycaemia/HbA1c with a 5 % weight loss whereas Morris et al. reported a 0.2 mmol/mol decrease in HbA1c per kg weight loss [35], 36]. Trials included in our MA might not have produced that weight loss % needed to improve CVD risk factors.

Last but not least, weight loss strategies may result in significant average weight loss in study participants, however, there exists larger interindividual variability. Some study participants may be hypo or hyper responders to weight loss strategies based on genetic variations [37].

Study Limitations: The subgroup analysis based on the type of anti-obesity drugs, intervention duration, and baseline BMI of participants could not be conducted due to the limited number of current trials. Anti-obesity drugs’ types might contribute to heterogeneity. The wide confidence intervals observed in some outcomes (e.g., triglycerides) indicate variability and reduced precision. Larger sample sizes or better standardization of interventions could reduce this variability in future studies. Meta-regression can not be conducted due to the limited number of trials.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. WHO. World Health Organization Fact sheet obesity and overweight released on March 1, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [Accessed Jul 1, 2024].Search in Google Scholar

2. Ells, LJ, Rees, K, Brown, T, Mead, E, Al-Khudairy, L, Azevedo, L, et al.. Interventions for treating children and adolescents with overweight and obesity: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Int J Obes 2018;42:1823–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0230-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Hampl, SE, Hassink, SG, Skinner, AC, Armstrong, SC, Barlow, SE, Bolling, CF, et al.. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics 2023;151. https://doi.org/10.1542/9781610027052-part01-clinical. e2022060640.Search in Google Scholar

4. US Food & Drug Administration. News release on June 27, 2022. FDA approves treatment for chronic weight management in pediatric patients aged 12 years and older. www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-treatment-chronic-weight-management-pediatric-patients-aged-12-years-and-older.Search in Google Scholar

5. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA approves weight management drug for patients aged 12 and older. News release on June 15, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-weight-management-drug-patients-aged-12-and-older.Search in Google Scholar

6. US Food & Drug Administration. New drug therapy approvals 2022. News release on Jan 10, 2023. www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/new-drug-therapy-approvals-2022.Search in Google Scholar

7. US Food & Drug Administration. News release on Nov 27, 2020. FDA approves first treatment for weight management for people with certain rare genetic conditions. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-approves-first-treatment-weight-management-people-certain-rare-genetic-conditions.Search in Google Scholar

8. Sherafat-Kazemzadeh, R, Yanovski, SZ, Yanovski, JA. Pharmacotherapy for childhood obesity: present and future prospects. Int J Obesity 2013;37:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.144.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Heal, DJ, Gosden, J, Smith, SL. What is the prognosis for new centrally-acting anti-obesity drugs? Neuropharmacology 2012;63:132–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Astrup, A, Toubro, S. Topiramate: a new potential pharmacological treatment for obesity. Obes Res 2004;12:167s–173s. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2004.284.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Gadde, KM, Allison, DB, Ryan, DH, Peterson, CA, Troupin, B, Schwiers, ML, et al.. Effects of low-dose, controlled-release, phentermine plus topiramate combination on weight and associated comorbidities in overweight and obese adults (CONQUER): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:1341–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60205-5.Search in Google Scholar

12. Garvey, WT, Ryan, DH, Look, M, Gadde, KM, Allison, DB, Peterson, CA, et al.. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:297–308. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.024927.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Drucker, DJ. GLP-1 physiology informs the pharmacotherapy of obesity. Mol Metab 2022;57:101351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101351.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Basolo, A, Burkholder, J, Osgood, K, Graham, A, Bundrick, S, Frankl, J, et al.. Exenatide has a pronounced effect on energy intake but not energy expenditure in non-diabetic subjects with obesity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Metabolism 2018;85:116–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2018.03.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Wadden, TA, Walsh, OA, Berkowitz, RI, Chao, AM, Alamuddin, N, Gruber, K, et al.. Intensive behavioral therapy for obesity combined with Liraglutide 3.0 mg: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019;597 27:75–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22359.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Vergès, B, Bonnard, C, Renard, E. Beyond glucose lowering: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, body weight and the cardiovascular system. Diabetes Metab 2011;37:477–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2011.07.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Torbahn, G, Jones, A, Griffiths, A, Matu, J, Metzendorf, MI, Ells, LJ, et al.. Pharmacological interventions for the management of children and adolescents living with obesity-an update of a Cochrane systematic review with meta-analyses. Pediatr Obes 2024;19:e13113. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.13113.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Axon, E, Atkinson, G, Richter, B, Metzendorf, MI, Baur, L, Finer, N, et al.. Drug interventions for the treatment of obesity in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;11:CD012436. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012436.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Czernichow, S, Lee, CM, Barzi, F, Greenfield, JR, Baur, LA, Chalmers, J, et al.. Efficacy of weight loss drugs on obesity and cardiovascular risk factors in obese adolescents: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2010;11:150–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00620.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Higgins, JP, Thomas, J, Chandler, J, Cumpston, M, Li, T, Page, MJ, et al.. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Glasgow, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2019.10.1002/9781119536604Search in Google Scholar

21. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al.. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Rethlefsen, ML, Kirtley, S, Waffenschmidt, S, Ayala, AP, Moher, D, Page, MJ, et al.. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021;10:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542.Search in Google Scholar

23. Sterne, JAC, Savović, J, Page, MJ, Elbers, RG, Blencowe, NS, Boutron, I, et al.. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Chanoine, JP, Hampl, S, Jensen, C, Boldrin, M, Hauptman, J. Effect of orlistat on weight and body composition in obese adolescents: a randomized controlled trial [published correction appears in JAMA. 2005;294(12):1491]. JAMA 2005;293:2873–83. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.23.2873.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Kelly, AS, Auerbach, P, Barrientos-Perez, M, Gies, I, Hale, PM, Marcus, C, et al.. A randomized, controlled trial of Liraglutide for adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2117–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1916038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Kelly, AS, Bensignor, MO, Hsia, DS, Shoemaker, AH, Shih, W, Peterson, C, et al.. Phentermine/topiramate for the treatment of adolescent obesity. NEJM Evid 2022;1. https://doi.org/10.1056/evidoa2200014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Maahs, D, de Serna, DG, Kolotkin, RL, Ralston, S, Sandate, J, Qualls, C, et al.. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of orlistat for weight loss in adolescents. Endocr Pract 2006;12:18–28. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP.12.1.18.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Weghuber, D, Barrett, T, Barrientos-Pérez, M, Gies, I, Hesse, D, Jeppesen, OK, et al.. Once-weekly Semaglutide in adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med 2022;387:2245–57. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2208601.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Zhou, YH, Ma, XQ, Wu, C, Lu, J, Zhang, SS, Guo, J, et al.. Effect of anti-obesity drug on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2012;7:e39062. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039062.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Deram, S, Villares, SM. Genetic variants influencing effectiveness of weight loss strategies. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 2009;53:129–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-27302009000200003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Gregg, EW, Jakicic, JM, Blackburn, G, Bloomquist, P, Bray, GA, Clark, JM, et al.. Association of the magnitude of weight loss and physical fitness change on long-term CVD outcomes: the Look Ahead study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:913–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30162-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Lean, M, Leslie, W, Barnes, A, Brosnahan, N, Thom, G, McCombie, L, et al.. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018;391:541–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33102-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Sundström, J, Bruze, G, Ottosson, J, Marcus, C, Näslund, I, Neovius, M, et al.. A nationwide study of gastric bypass surgery versus intensive lifestyle treatment. Circulation 2017;135:1577–85. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.116.025629.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Brown, JD, Buscemi, J, Milsom, V, Malcolm, R, O’Neil, PM. Effects on cardiovascular risk factors of weight losses limited to 5-10. Transl Behav Med 2016;6:339–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-015-0353-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Garvey, W, Mechanick, J, Brett, E, Garber, AJ, Hurley, DL, Jastreboff, AM, et al.. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract 2016;22:842–84. https://doi.org/10.4158/ep161356.esgl.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Morris, E, Jebb, S, Oke, J, Nickless, A, Ahern, A, Boyland, E, et al.. Effect of weight loss on cardiometabolic risk: observational analysis of two randomized controlled trials of community weight loss programmes. Br J Gen Pract 2021;71:e312–19. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20x714113.Search in Google Scholar

37. van der Meer, R, Mohamed, SA, Monpellier, VM, Liem, RSL, Hazebroek, EJ, Franks, PW, et al.. Genetic variants associated with weight loss and metabolic outcomes after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2023:e13626. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13626.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2024-0196).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Physical Activity, Sleep, and Lifestyle Behaviours

- Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its association with hypertension among young adults in urban Meghalaya: a cross sectional study

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Psychosocial predictors of adolescent stress: insights from a school-going cohort

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Barriers and facilitators in the transition from pediatric to adult care in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe – a qualitative systematized review

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Self-care or self-risk? examining self-medication behaviors and influencing factors among young adults in Bengaluru

- Health Equity and Access to Care

- Clinical heterogeneity of adolescents referred to paediatric palliative care; a quantitative observational study

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- ‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Physical Activity, Sleep, and Lifestyle Behaviours

- Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its association with hypertension among young adults in urban Meghalaya: a cross sectional study

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Psychosocial predictors of adolescent stress: insights from a school-going cohort

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Barriers and facilitators in the transition from pediatric to adult care in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe – a qualitative systematized review

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Self-care or self-risk? examining self-medication behaviors and influencing factors among young adults in Bengaluru

- Health Equity and Access to Care

- Clinical heterogeneity of adolescents referred to paediatric palliative care; a quantitative observational study

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- ‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping