Abstract

Objectives

With over 54,000 people affected, cystic fibrosis is one of the most common rare diseases in Europe. As life expectancy of this disease has steadily increased in recent years, the transition from pediatric to adult care has become a principal issue. This study aimed to identify facilitating and hindering factors in the transitional care of cystic fibrosis patients in order to derive indications for improving care.

Methods

A qualitative systematized review was conducted in May 2024 with a systematic search carried out in MEDLINE, CINAHL and Livivo, including European studies from 2009 to 2024. The studies’ quality was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative studies. Thematic analysis was applied for analyzing the data to identify categories.

Results

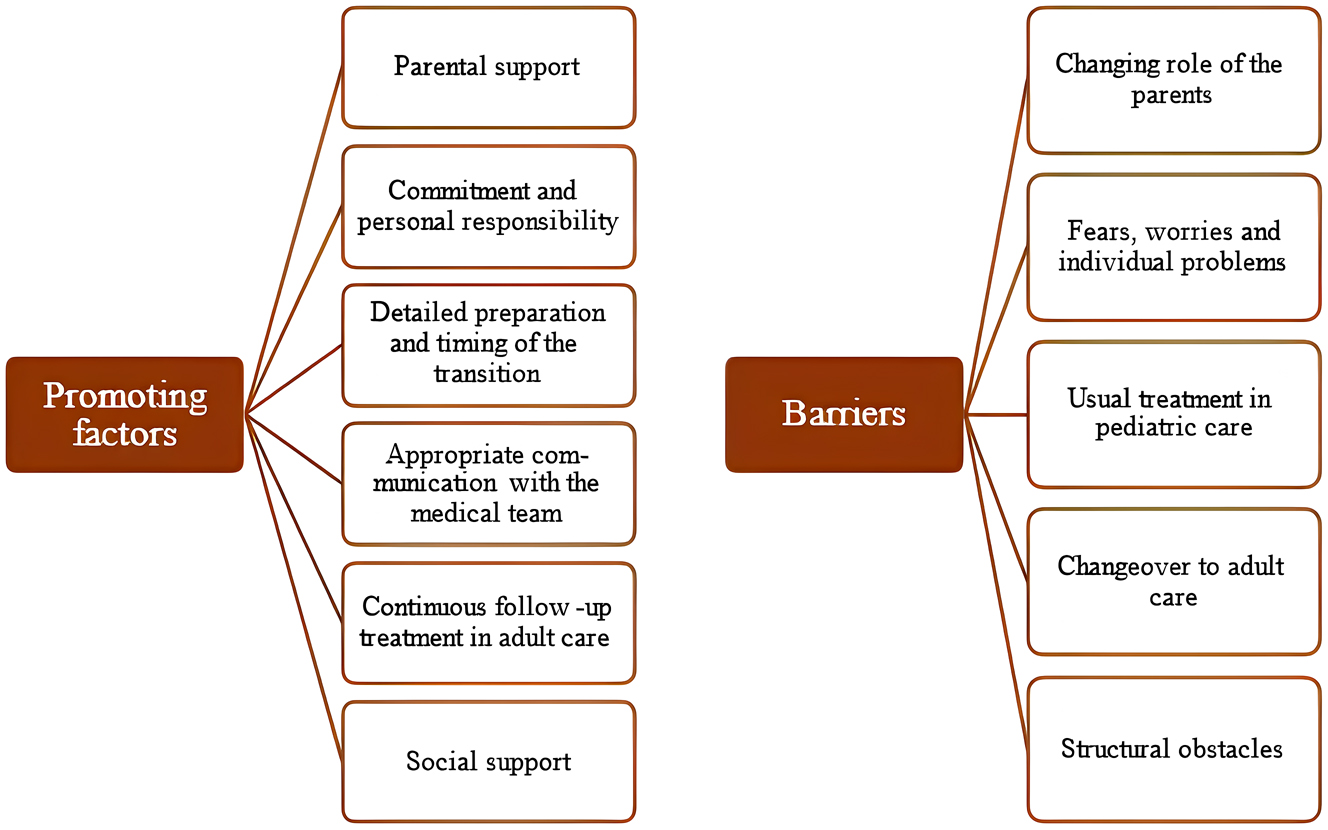

Nine studies met the inclusion criteria. Their quality can be rated as medium to high. Parental support, commitment and social support were identified as beneficial factors. Preparation for the transition, appropriate communication and continuous follow-ups at the adult center also contributed to a continuous transition. However, the parents’ changing roles, fears and the usual treatment in pediatrics were obstacles. The adjustment to the adult center and structural problems presented further barriers to transition.

Conclusions

Various factors were identified to influence the transition process in cystic fibrosis, with consistency across the studies. In practice, comprehensive care is required, focused on the patients’ needs, with more information provided and enhanced collaboration among stakeholders. Further research regarding the long-term effects of transition and the utilization of structured transition programs is needed.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is one of the most common autosomal recessive hereditary diseases and associated with high morbidity and mortality. The incidence of CF differs internationally, with Europe, North America and Australia having the highest number of patients [1]. Cystic fibrosis leads to increased viscosity of secretions in the body which affects the function of several organs [2]. Consequences of CF include chronic lung disease, pancreatic insufficiency and diseases of the liver and bile ducts [3]. Until this day, no cure for the illness exists [4]. Nonetheless, the use of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators prolongs the life expectancy of patients compared to best supportive care therapies. If therapy is started early, a near-normal life expectancy may be achieved [5], underlining the necessity for a well-structured transitional care.

According to the patient registry of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society (ECFS), in 2021, most affected people aged between 5 and 15 years. From the age of around 15, the number of people affected steadily decreases [6]. While up until the 1980s, the life expectancy was still at around 18 years [7], the proportion of adults with CF in Europe reached 56 % in 2023 [8]. These figures are expected to increase further in the upcoming years [9] although there are major variations between the countries [6].

In 2014, standards of care were released by the ECFS. Due to the complexity of the disease, a care in specialized CF centers with multidisciplinary teams from different disciplines is required, e.g., respiratory pediatricians, clinical nurse specialists, psychologists and social workers. Each center is supposed to have sufficient staff and facilities to provide high-quality and evidence-based care in all European countries. The standards contain information about transitional care as well, such as the cooperation between the pediatric and adult services, responsibilities and tasks concerning appropriate care [10].

Regarding the number of affected people and the importance of continuous care, the uninterrupted transition from pediatric to adult health care plays a significant role. Transition refers to the planned transfer of adolescents with chronic conditions from pediatric to adult-oriented care [11] as well as increasing responsibility, self-management and the acquisition of medical knowledge [12]. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes “adolescence” with the span from 10 to 19 years, while “young people” are defined as persons ranging 10 to 24 years of age [13]. The process of transition should be family-centered, stepwise and provide flexibility [12]. A transition must be distinguished from a transfer which describes the single event of changing physicians providing care [14]. An inadequate preparation for the change can result in higher risk of non-compliance to therapy, a lack of follow-up [15], a deterioration in the state of health and hence, cause negative long-term effects [16]. The timing for transition depends on distinct factors such as age, health status [17], developmental maturity and the availability of adult physicians [18]. The average age for a CF transition varies between 16 and 21 years [19] and thus, often coincides with other major life events (e.g., graduation from high school) [18]. A transition pursues several goals, such as continuous care [20], increased knowledge of the illness [14] and maintaining quality of life [21].

Various transition programs for CF exist whereby the implementation and realization differs between the CF centers and regions, meaning that no consistent model is used [22]. A commonly used model, e.g. in the United Kingdom [22] and Germany [23], contains the handover from the pediatric to the adult care team, often in joint consultations. Some centers also have youth clinics to help facilitate the transition. Regardless of the utilized concept, responsibilities and competences of the disciplines should be defined and the care should be adapted to the patients’ needs [22]. A well-planned transition is necessary to ensure a good health status [24] and to treat CF patients in the best way possible [22]. It is therefore important to include the patients’ perspective to understand how they have experienced the transition.

To examine precisely these subjective perspectives, the aim of this qualitative systematized review is to identify and analyze the facilitating and inhibiting factors for a transition from pediatric to adult care in patients with cystic fibrosis in Europe, as reported by the patients, their parents or the medical staff. As transition approaches in Europe differ greatly from one another [25], this review wants to present an overview of studies on the experiences with the CF transition. It also aims to draw attention to the importance of cystic fibrosis care and to identify any gaps in care and areas for improvement.

Materials and methods

Study design

A systematized review of qualitative studies was conducted. The qualitative approach enabled deeper insights and understandings of the process examined. Due to a lack of time resources, the work was carried out by one person. However, in order to make the process as objective as possible, the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting of Qualitative Research Syntheses (ENTREQ) checklist [26], the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist [27] as well as a guideline for qualitative systematic reviews [28] were strictly adhered to.

The ENTREQ checklist was used for writing a qualitative review [26] as well as the guideline for qualitative systematic reviews [28]. The PRISMA checklist served as the basis for composing a review and the study selection process [27].

Search strategy & search string

The systematic search was carried out in the MEDLINE (via PubMed) and CINAHL (via EBSCOhost) databases as well as in Livivo. In addition, the reference lists of eligible articles were screened and a manual search was conducted. To operationalize the research aim, the PEO scheme was used as shown in Table 1.

PEO scheme for operationalizing the research question.

| Population | People affected by CF |

| Exposure | Transition from pediatric to adult-oriented health care |

| Outcome | Factors that support or inhibit the transition which were reported by patients, parents or health care professionals |

The search for relevant studies was carried out in May 2024 using the search terms shown in Table 2. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) – Terms were applied in MEDLINE and Livivo. For the CINAHL database, the equivalent CINAHL-Headings were used for the same terms. The search string was adapted to the syntax in the databases.

Search string in PubMed.

| Search Number | String |

|---|---|

| #1 | (mucoviscidosis OR cystic fibrosis [MeSH]) AND |

| #2 | (transition OR transfer OR shift OR adaptation OR change) AND |

| #3 | (care OR health care OR health services OR medical care OR p?ediatric care OR adult care OR internal care OR health professional OR clinical staff OR physician [MeSH] OR nurse [MeSH] OR therapist) AND |

| #4 | (adult [MeSH] OR grown up OR parent [MeSH] OR parents) AND (child [MeSH] OR p?ediatric OR infant [MeSH] OR young adult OR teenager [MeSH] OR adolescent OR patient [MeSH]) AND |

| #5 | (experiencea OR perception [MeSH] OR needa OR viewa OR understanding [MeSH] OR opinion [MeSH] OR belief [MeSH] OR conception [MeSH] OR perspective) |

| #6 | Search #1 & #2 & #3 & #4 & #5 |

-

astands for truncation; ? stands for a wildcard. Search date: 31 May 2024; Filters applied: Publication year: 2009 – 2024 (no language filters applied; studies were manually selected).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Qualitative studies and qualitative data from mixed-methods studies were included. Only studies that used interviews to collect data were considered. These were integrated if the transition in cystic fibrosis from pediatric to adult-oriented care was addressed from the patients’, parents’ or health care professionals’ perspective. The studies had to be conducted in European countries within the last 15 years (2009–2024) as the research on CF transition has intensified in recent years and the 2009 recommendation of the Council of the European Union on rare diseases has focused greater attention on their care [29]. Studies in German, English and French were considered for this review.

Studies were excluded if the CF transition was assessed in non-European countries, if the transition process was generally examined for chronic diseases or if it focused on other (pulmonary) illnesses. Articles were not integrated if comorbidities of CF were looked at, if specific CF therapies or disciplines were explored or when only a quantitative research approach was used.

Quality appraisal

A quality appraisal of the selected studies was conducted, utilizing the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative studies. The qualitative study design, data collection and analysis and ethical aspects were part of the evaluation [30]. Since this instrument comes without an assessment tool, Butler et al. [28] developed a point system which was the basis for the quality appraisal in this review with a maximum score of 10 points.

Data extraction and analysis

All identified studies were imported in the reference management program EndNote 21 (Clarivate Analytics, USA) and duplicates were removed using the software check and a manual elimination. The most relevant data from all included studies were documented in an extraction table in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA).

The data analysis was performed using thematic analysis. This method contains the identification of recurring themes and a summary of categories from different studies in thematic headings [31]. A combination of a deductive and an inductive approach was applied.

As the research objective is based on facilitating factors and barriers in the CF transition, these two topics were considered separately and categories were formed within each of these themes. The data were analyzed according to the thematic analysis of qualitative research in systematic reviews by Thomas & Harden [32] in three stages. First, the studies were coded line-by-line and relevant text passages were color-coded. Codes for each study were noted in a Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, USA) table. Second, descriptive themes were developed where similarities and differences between the codes of the studies were searched for [32] and a hierarchy of the categories was established [33]. To make comparisons, codes of subsequent studies were categorized into existing concepts and new categories were created when required [26]. Lastly, analytical themes were generated and described themes were summarized, analyzed and organized [32].

Both the statements of the participants and the interpretations of the researchers of the qualitative primary studies were integrated in this review to be able to analyze both forms of data [28] and to obtain a comprehensive perspective.

Results

Study selection

As shown in Figure 1, 602 studies were identified and nine studies were found through a manual search. After removing the duplicates, 404 studies were integrated into the pre-selection. By screening the titles and abstracts, 371 papers were eliminated from inclusion and the full texts of 33 studies were read. In the end, nine studies were included in this qualitative review. The complete study selection process was conducted using EndNote 21 (Clarivate Analytics, USA).

![Figure 1:

Study selection process (according to Liberati et al. [27]).](/document/doi/10.1515/ijamh-2024-0192/asset/graphic/j_ijamh-2024-0192_fig_001.jpg)

Study selection process (according to Liberati et al. [27]).

Study characteristics and quality

The nine included studies were published between 2010 and 2023 and realized in seven European countries. One study each was conducted in Switzerland [34], France [35], Germany [36], Belgium [37] and the Netherlands [38]. Two studies were carried out in Ireland [39], 40] as well as in Great Britain [41], 42]. Seven studies were realized using a qualitative study design while the other two utilized a mixed-methods design. The sample size for the young people ranged from 6 [34] to 50 participants [41]. The number of interviewed parents varied from 7 [34] to 41 people [35] and of the health care staff from 16 [36] to 28 respondents [38]. One study did not provide information about the sample size [40]. The patients’ age ranged from 13 years [41] to a maximum age of 26 years [34]. The staff came from various disciplines, including medicine, nursing, physiotherapy and nutritional counselling [41], social work [36] as well as psychology [38].

According to the CASP checklist, the quality of the included studies can be rated as medium [36], [38], [39], [40] to high [34], 35], 37], 41], 42]. In most studies, there was a lack of reflection on the researchers’ own role during the data collection and analysis.

Identified categories

Three main categories were deductively derived from the literature: The role of the parents, care in the pediatric center and further treatment in the adult center. After the coding and analysis process, six categories could be identified within the theme of promoting factors and five categories within the topic of barriers in the CF transition process, which are shown in Figure 2.

11 deductively and inductively identified categories, assigned to the two subject areas “promoting factors” and “barriers”

Promoting factors

Parental support

Six studies described parental support as a facilitating factor. The adolescents wanted their parents to accompany them during the transition preparation and the first appointments at the new facility. The parents’ presence was seen as a guarantee that patients would not provide the medical team with incorrect information [34] and as a courage to ask more questions [42].

“I prefer that there is always someone with me. Just in case I forget something, then, someone says it for me.” [35] (p.261)

The patients reported that their parents were supportive, especially in emergency situations [37], 41]. Furthermore, the adolescents determined the degree of their parents’ integration which was encouraged by a positive attitude of the parents regarding the process of letting go [37]. They also protected their kids from thoughts of premature death and the shortening of life due to CF [41]. The health professionals confirmed the importance of an ongoing partnership between the parents and the patient to maintain the health of the affected person [41].

Commitment and personal responsibility

Eight studies identified commitment and autonomy as a basis for a good orientation in the new care structures [39]. Most young people looked forward to more personal responsibility [42], took the opportunity to decision-making power in the new facility [41] and showed engagement regarding the choice of a new clinic [34]. By having individual conversations in the children’s hospital, the medical team supported the development of their independence [34]. The patients found the therapy more rewarding as they were motivated by their own decision and drive [42]. The hospital regulations also played a role since the adolescents learned to stand up for themselves [35], 37]. The health professionals named intrinsic motivation and commitment as crucial requirements to successful transition [38].

Detailed preparation and timing of the transition

Preparation to transition and its timing was explored by seven studies. A gradual and thorough handover [40] as well as flexibility [38] were reasons for an improved transition. An early start was seen as essential by the medical staff [36], 38], 40]. The recommended age varied between 11 and 16 years but there were discrepancies with regard to the timing, as some health professionals preferred a flexible start while others favored a clear age limit [36].

“Absolutely, we should have an individualised comprehensive approach that cares about each individual separately and meets their needs.” [40] (p.31)

The patients wanted to have a say in the timing [35] and a detailed planning [40] to ensure a structured and continuous care [38]. Furthermore, the information transfer during the preparation phase and to the adult center was crucial [39]. The possibility of meeting the new medical team [36] and the organization [35] was considered important and appreciated by the patients [42].

Appropriate communication with the medical team

Seven studies dealt with the communication between the young people and the health staff. The patients wished that the professionals listened to them and their needs [39] and reported this as a selection criterion for the choice of an adult clinic [34]. The difference in the communication was perceived positively [34], 42].

“So, the older I got, the more they (i.e. physicians) addressed the conversation directly to me.” [37] (p.4)

The patients wanted to have individual conversations [35] but therefore needed to gain competences [37]. The medical team too, had to adapt their communication style, regarding the adolescents’ special stage of life [40]. The patients were glad that they talked about difficult topics, such as the life shortening of the disease, with the professionals and parents [41].

Continuous follow-up treatment in adult care

Seven studies thematized the treatment in adult care. To ensure a smooth transition, the health professionals recommended to engage transition coordinators, e.g. specialized nurses [36], 38]. Also, the presence of the CF-pediatrician at the first appointment in adult care [34] and a time span of a joint care was reported helpful [40]. Continuing with the usual treatment from pediatric care was perceived positively by the adolescents as there were no gaps in care [34]. Permanent contact persons who accompany the patients [36] and have an open mind helped them with the change [42]. Organizing a patient-centered care [39] and information transfer between the centers were facilitating factors to transition [34].

“It is no longer the case that you just hand over the person. Instead, ‘This is the patient as a whole: this is his disease, this is his personality and these are goals or concerns.’ I think that’s the secret of a good transition, that you know all these facets.” [38] (p.1816)

To constantly improve the transition, the health professionals proposed evaluations and trainings about specific transition topics [40].

Social support

The opportunity of a psychosocial support for the family was a positive influence [36] and transition would profit from more attention for these aspects [38]. Talking to other affected adolescents about transition or the choice of a center was relevant for patients [34] as were close relations and support from friends, siblings and other family members [41].

Barriers

Changing role of the parents

Five studies addressed the changing role of the parents. They found it difficult to let their children go into independence [36] and the start of adult life [35] and described this situation as challenging [37].

“Where will our place be (as parents)?” [35] (p.262)

The parents tended to be overprotective, involved [36] and still felt responsible [37]. A problem was the shift from control to support for the children [34]. These adjustment problems became visible in the parents’ need for information [37] and concerns about a lack of information [35], 41]. Overall, the situation led to tensions between the adolescents’ autonomy and the parents’ solicitude [41].

Fears, worries and individual problems

Seven studies described fears and worries of the young people which were reported as barriers to transition by the patients and led to doubts [36]. Fears included the new care, concerns about not being noticed, worries about infections, quality of care and hospital regulations [39].

“It is not like I don’t want to go, I really want to but [I am] a bit worried how they will be like, you know with CF you should be careful from infections.” [39] (p.852)

Some patients did not feel prepared for the transition [37]. Moreover, the youth was a time with decreased compliance as they lived out their newfound autonomy and other life events gained importance [36], e.g., the change to university or the start of professional life [35], 42].

Usual treatment in pediatric care

Seven studies identified hindering factors regarding the usual treatment in pediatrics. A majority of young people noticed a lack of information [39] and preparation in pediatric care [34]. Some affected people felt that their needs were neglected due to uncertainties in the rules of responsibility [42]. A close bond to the pediatric team which was established over several years [42] was seen as a barrier by the patients, the parents [34] and the health professionals [42].

“It’s not that it scares me, but I’m so attached to the team that I don’t really want to leave.” [35] (p.260)

Because of an individual care [34] and strong commitment of the pediatric team [38], the adolescents preferred to stay in the child and youth care services [34].

Changeover to adult care

The changeover to adult care was thematized by seven studies. Changes between pediatric and adult care were reported as well as alternating practitioners in the new center [36]. Furthermore, the affected people needed to learn how to cope with their new role as a central contact person [42]. They were supported less in adult care [38] and the care was more anonymous [36]. An insufficient communication and networking between the disciplines was described by the medical team [36] and the patients [37]. There were long waiting times for a first appointment [42] and different hospital regulations led to frustrations on the parents’ part [37].

Structural obstacles

Three studies depicted structural obstacles. Major barriers were lack of staff and time, which is why improved communication between the disciplines was considered difficult by the health professionals [36] as were longer consultations or team meetings [38].

“Nowadays, everyone is too busy. […] I think that our collaboration suffers from that. Because there is just too little time to think about things quietly and to align or fine-tune things.” [38] (p.1817)

In addition, there were often no regulations for further treatments or a standardized transition [39]. Another factor was funding, as transitional care was not covered [38].

Discussion

This qualitative review included nine studies and identified promoting and hindering factors in the CF transition based on the experiences of the patients, parents and health professionals. The quality of the studies was assessed as medium to high. Positive aspects were parental and social support, commitment, a detailed and early preparation, a continuous care and an appropriate communication. A changing role of the parents, fears, the usual care in pediatrics, the changeover to adult care and structural obstacles presented barriers to transition.

Parental support during the transition process was determined as beneficial [34], 35], 41] although the change in the parents’ role was perceived as challenging [35], 37], 41]. Bregnballe et al. [43] explored the disease-related challenges of 18–25-year-old CF patients and their parents. 51 % of parents whose children had already moved out, reported difficulties regarding the best possible support. Moreover, therapy adherence was lower amongst those who had moved out than amongst those who were still living at home, even if the difference was not statistically significant [43]. Butcher & Nasr [44] discovered that adherence was higher if the patients received attention from their parents and if negative statements were avoided [44]. It remains a crucial challenge to find the right level of involvement in this sensitive stage of life which has to be considered individually in each case.

Commitment and responsibility were identified as promoting factors for a CF transition. Office & Heeres [45] suggest that adolescents should gain confidence before the transfer to adult services. Thus, individual conversations and communication competences should be trained in a comfortable setting with the pediatric team [45], which was also mentioned by other studies [34]. Singh et al. [46] add that assessing the patients’ knowledge of their disease is a prerequisite for promoting engagement. Developing independence can help to overcome the interface between pediatric and adult services [46]. Nevertheless, it could also lead to the patients being overwhelmed if they do not feel ready yet [47]. This highlights the importance of an individualized and flexible approach which was identified as a facilitator to transition in this review.

Fears and worries were described by several studies as barriers to transition. Coyne et al. [24] found concerns from multiple studies, including fears regarding the differences and quality in care and the changeover to the adult team which are similar to the worries determined in this review. Fears by the CF patients are not solely restricted to health care. The International Depression Epidemiological Study assessed psychological symptoms in affected people and their caregivers in 154 CF centers, including Belgium, Germany and Spain [48]. Depression and anxiety symptoms were two to three times higher than in the general population [48]. Therefore, special attention needs to be given to the young people.

A detailed and planned transition as well as information transfer were seen as important while the changeover to adult services was deemed a hindrance. Jamieson et al. [49] described that many patients did not feel prepared for transition and stated insufficient recognition in pediatric care which aligns with findings of this review. Care standards for people with CF were published in 2024 and an early beginning, enhanced communication between the disciplines, common facilities and a preparation for adult life are recommended [50]. Thus, these standards are consistent with outcomes of this review. To achieve a continuous transition, engaging coordinators was found as helpful [36], 38]. A coordinated process is also mentioned by Office & Heeres [45] and Singh et al. [46] who describe the task of coordinators to identify CF patients who are prepared to start transition. Coyne & Hallowell [51] add the importance of appropriate communication which was also identified as a facilitating factor. The role of the coordinating nurses can include information and data transfer from pediatric to adult care and maintaining connections between the teams for any uncertainties [51].

A lack of a standardized transition could be identified. There is limited availability of CF-specific guidance on the structure of the process as reported by Gramegma et al. [50]. Nevertheless, there already exist guidelines for the transition of chronically ill children and adolescents to adult services in Europe which can serve as a basis for the use in CF patients (e.g. the NICE guideline in the United Kingdom [52] or the evidence-based guideline on health transition from Germany [53]). The advantages of a structured transition were also explored in a study from 2022 which examined the differences in outcomes between adolescents who underwent a formal transition (e.g., preparation and multidisciplinary collaboration) and those who experienced an informal transition (regular care). Participants of the formal transition had significantly lower levels of anxiety and were more content with the process [54]. Chaudhry et al. [55] additionally found that patients in the formal transition showed an improved perceived health status and independence but anxiety did not decrease. However, elements of the formal transition included facilitators from this review and thus can be seen to be important for CF transition.

Lastly, psychosocial support was viewed as helpful. Jamieson et al. [49] confirmed these findings and described support from close people as a resource. Contact with other affected adolescents also strengthened social interactions [49]. Furthermore, the 2018 ECFS guideline states that psychosocial help is an essential part of CF care [56]. Flewelling et al. [57] determined that social support is associated with positive outcomes in CF adult patients, such as less self-stated health problems and an enhanced emotional functioning. Hence, psychosocial support is of particular relevance in the CF transition.

Implications for practice

Implications for action can be derived for application in clinical practice as well as possible improvement opportunities in transitional care. Regarding the parental involvement in the process, young, affected patients proposed an educational style and meetings with other parents [58]. Hence, events for parents of CF adolescents could be a possibility to exchange experiences during the transition period.

To enhance the commitment and responsibility of the adolescents and simultaneously reduce worries, “Transition Readiness Scales” can be utilized to assess the patients’ skills and knowledge to determine transition willingness [59]. Bourke & Houghton [59] confirmed the need of this tool for CF and discovered advantages, such as an improved transitional care [59]. In 2011, it was developed and validated for CF, but it was inadequate for clinical use and a concise tool is required [60], whereby general tools can provide a framework [61]. Besides implementing and using such instruments, providing more information to increase peoples’ knowledge and an improved collaboration and networking between the disciplines could contribute to coordinate the transition individually and ensure an uninterrupted care.

Using telemedicine and virtual checks in CF care can reduce fears regarding the risk of infection in the clinics and strengthen an active role of the patients as well as an eased communication between the practitioners [62]. It is not a substitute for in-person care, rather it can be integrated into the existing standard of care [62], thereby facilitating its implementation in transitional care settings.

Psychosocial support was identified as an important resource. The “Impact on Family Scale” to assess social loads in families with chronically ill children [63] might be suitable for the identification of psychosocial support services for CF patients [64] and to adequately consider the patients’ families.

Additionally, organizational and administrative structures should be expanded, including training for medical staff to counteract the shortage of specialists. An increased sensibilization of all those involved (including decision-makers) may contribute to an improved transition.

Limitations

This review included the patients’, parents’ and health professionals’ experiences which provides a variety of perspectives and can be seen as a strength. Since qualitative research generates theories in the first place [65], publication bias is considered unlikely. Yet, it cannot be ruled out that relevant studies have not been published. The included studies had a medium to high quality but often lacked a reflection of the researchers’ role which should be considered while interpreting the results of this review. Using checklists to assess the quality of qualitative research can have disadvantages, such as a lack of sensitivity due to an insufficient distinction of methodological approaches or forms of data acquisition [66]. This should be taken into account while looking at the quality of the integrated studies. The origin of the studies is a further limitation since they were only conducted in Western and Middle Europe. Only a limited number of databases were used and time and language restrictions were applied. Thus, other relevant studies may have not been included. One person carried out the search, quality appraisal and data analysis. Therefore, a personal bias cannot be excluded. Furthermore, since qualitative research does not claim to be representative [65], the results cannot be generalized or transferred to other diseases with different priorities in the transition processes. Nonetheless, they provide a good insight into peoples’ experiences across national borders.

Conclusions

Different factors promote and hinder the process of a CF transition. Overall, there was agreement between the factors reported in the studies. Thus, it would be necessary to implement the identified facilitators in practice to enable a continuous transition for CF patients. The growing proportion of adult CF patients justifies the necessity of a clearly regulated transition from pediatrics to internal medicine. It is important to address the individual needs of patients and provide more information during the preparation. The Europe-wide networking in cystic fibrosis can be highlighted and should be strengthened to ensure high-quality care across different European countries. Standardized transition programs, the use of transition readiness scales and telemedicine are potential improvements, although further research about the sustainability and acceptance is required.

Additional research could be based on quantitative approaches on the topics identified to capture larger samples and obtain generalizable results. The long-term effects of transition should be further researched to make improvements to care. Various transition programs could be implemented and scientifically supported in Europe. With further efforts by all stakeholders, the transitional care can be improved to enable a smooth and continuous transition from pediatric to adult-oriented care for all patients with cystic fibrosis, providing the basis for an optimal health care in the patients’ adult life.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Elborn, JS. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2016;388:2519–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00576-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. López-Valdez, JA, Aguilar-Alonso, LA, Gándara-Quezada, V, Ruiz-Rico, GE, Ávila-Soledad, JM, Reyes, AA, et al.. Cystic fibrosis: current concepts. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 2021;78:584–96. https://doi.org/10.24875/BMHIM.20000372.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Castellani, C, Assael, BM. Cystic fibrosis: a clinical view. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017;74:129–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2393-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Sawicki, GS, Tiddens, H. Managing treatment complexity in cystic fibrosis: challenges and opportunities. Pediatr Pulmonol 2012;47:523–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.22546.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Lopez, A, Daly, C, Vega-Hernandez, G, MacGregor, G, Rubin, JL. Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor projected survival and long-term health outcomes in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for F508del. J Cyst Fibros 2023;22:607–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2023.02.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Zolin, A, Orenti, A, Jung, A, Jv, R, Adamoli, A, Prasad, V, et al.. ECFSPR annual report 2021: European Cystic Fibrosis Society; 2023. Available at: https://www.ecfs.eu/sites/default/files/Annual%20Report_2021_09Jun2023.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

7. Bierlaagh, MC, Muilwijk, D, Beekman, JM, van der Ent, CK. A new era for people with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Pediatr 2021;180:2731–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04168-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. European Cystic Fibrosis Society Patient Registry. 2023 highlights report: Cystic Fibrosis in Europe Facts and Figures; 2025. Available at: https://www.ecfs.eu/sites/default/files/250129_PR_Highlights.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

9. Burgel, PR, Burnet, E, Regard, L, Martin, C. The changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis: the implications for adult care. Chest 2023;163:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2022.07.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Conway, S, Balfour-Lynn, IM, De Rijcke, K, Drevinek, P, Foweraker, J, Havermans, T, et al.. European cystic fibrosis society standards of care: framework for the cystic fibrosis centre. J Cyst Fibros 2014;13:S3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2014.03.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Blum, RWM, Garell, D, Hodgman, CH, Jorissen, TW, Okinow, NA, Orr, DP, et al.. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions: a position paper of the society for adolescent medicine. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:570–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139x(93)90143-d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Tuchman, LK, Schwartz, LA, Sawicki, GS, Britto, MT. Cystic fibrosis and transition to adult medical care. Pediatrics 2010;125:566–73. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2791.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. World Health Organization. Adolescent health n.d. Available at: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1.Search in Google Scholar

14. Toulany, A, Gorter, JW, Harrison, M. A call for action: recommendations to improve transition to adult care for youth with complex health care needs. Paediatr Child Health 2022;27:297–309. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxac046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Viner, RM. Transition of care from paediatric to adult services: one part of improved health services for adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:160–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2006.103721.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Sipanoun, P, Aldiss, S, Porter, L, Morgan, S, Powell, E, Gibson, F. Transition of young people from children’s into adults’ services: what works for whom and in what circumstances - protocol for a realist synthesis. BMJ Open 2024;14:e076649. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-076649.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. David, TJ. Transition from the paediatric clinic to the adult service. J R Soc Med 2001;94:373–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680109400801.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Yankaskas, JR, Marshall, BC, Sufian, B, Simon, RH, Rodman, D. Cystic fibrosis adult care: consensus conference report. Chest 2004;125:1S–39S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.1_suppl.1s.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Office, D, Madge, S. Transition in cystic fibrosis: an international experience. In: Betz, CL, Coyne, IT, editors. Transition from pediatric to adult healthcare services for adolescents and young adults with long-term conditions: an international perspective on nurses’ roles and interventions. Cham: Springer Cham; 2020:171–88 pp.10.1007/978-3-030-23384-6_8Search in Google Scholar

20. Kaufman, M, Pinzon, J, Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee. Transition to adult care for youth with special health care needs. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12:785–8.10.1093/pch/12.9.785Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Kreindler, J, Miller, V. Cystic fibrosis: addressing the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented health care. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:1221–6. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.s37710.Search in Google Scholar

22. Nazareth, D, Walshaw, M. Coming of age in cystic fibrosis – transition from paediatric to adult care. Clin Med (Lond) 2013;13:482–6. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.13-5-482.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Fischer, R, Nährig, S, Kappler, M, Griese, M. Betreuung von Mukoviszidosepatienten beim Übergang vom Jugendalter zum Erwachsenen. Internist (Berl) 2009;50:1213–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00108-009-2399-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Coyne, I, Sheehan, AM, Heery, E, While, AE. Improving transition to adult healthcare for young people with cystic fibrosis: a systematic review. J Child Health Care 2017;21:312–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493517712479.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Poamaneagra, SC, Plesca, DA, Tataranu, E, Marginean, O, Nemtoi, A, Mihai, C, et al.. A global perspective on transition models for pediatric to adult cystic fibrosis care: what has been made so far? J Clin Med 2024;13:7428. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13237428.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Tong, A, Flemming, K, McInnes, E, Oliver, S, Craig, J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Liberati, A, Altman, DG, Tetzlaff, J, Mulrow, C, Gøtzsche, PC, Ioannidis, JP, et al.. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. https://doi.org/10.2427/5768.Search in Google Scholar

28. Butler, A, Hall, H, Copnell, B. A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs 2016;13:241–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12134.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation of 8 June 2009 on an action in the field of rare diseases 2009. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2009:151:0007:0010:EN:PDF.Search in Google Scholar

30. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP checklist: for qualitative research; 2024. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-checklists/CASP-checklist-qualitative-2024.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

31. Dixon-Woods, M, Agarwal, S, Jones, D, Young, B, Sutton, A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/135581960501000110.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Thomas, J, Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Nicholson, E, Murphy, T, Larkin, P, Normand, C, Guerin, S. Protocol for a thematic synthesis to identify key themes and messages from a palliative care research network. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:478. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2282-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Becher, C, Regamey, N, Spichiger, E. Transition - Wie Jugendliche mit Cystischer Fibrose und ihre Eltern den Übertritt von der Kinder- in die Erwachsenenmedizin erleben. Pflege 2014;27:359–68. https://doi.org/10.1024/1012-5302/a000389.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Genovese, VV, Perceval, M, Buscarlet-Jardine, L, Pinsault, N, Gauchet, A, Allenet, B, et al.. Smoothing the transition of adolescents with CF from pediatric to adult care: pre-transfer needs. Arch Pediatr 2021;28:257–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2021.03.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Jungbauer, J, Orf, J, Heidemann, K. Transition bei Jugendlichen mit Mukoviszidose: Ergebnisse einer Expertenbefragung. Kinder- Jugendmed 2022;22:100–5. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1761-6359.Search in Google Scholar

37. Wyngaert, KV, Debulpaep, S, Van Biesen, W, Van Daele, S, Braun, S, Chambaere, K, et al.. The roles and experiences of adolescents with cystic fibrosis and their parents during transition: a qualitative interview study. J Cyst Fibros 2023;23:512–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2023.10.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Peeters, MAC, Sattoe, JNT, van Staa, A, Versteeg, SE, Heeres, I, Rutjes, NW, et al.. Controlled evaluation of a transition clinic for Dutch young people with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2019;54:1811–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.24476.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Al-Yateem, N. Child to adult: transitional care for young adults with cystic fibrosis. Br J Nurs 2012;21:850–4. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2012.21.14.850.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Al-Yateem, N. Guidelines for the transition from child to adult cystic fibrosis care. Nurs Child Young People 2013;25:29–34. https://doi.org/10.7748/ncyp2013.06.25.5.29.e175.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Iles, N, Lowton, K. What is the perceived nature of parental care and support for young people with cystic fibrosis as they enter adult health services? Health Soc Care Community 2010;18:21–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00871.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Tierney, S, Deaton, C, Jones, A, Oxley, H, Biesty, J, Kirk, S. Liminality and transfer to adult services: a qualitative investigation involving young people with cystic fibrosis. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:738–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Bregnballe, V, Boisen, KA, Schiøtz, PO, Pressler, T, Lomborg, K. Flying the nest: a challenge for young adults with cystic fibrosis and their parents. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11:229–36. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S124814.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Butcher, JL, Nasr, SZ. Direct observation of respiratory treatments in cystic fibrosis: parent-child interactions relate to medical regimen adherence. J Pediatr Psychol 2015;40:8–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsu074.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Office, D, Heeres, I. Transition from paediatric to adult care in cystic fibrosis. Breathe (Sheff) 2022;18:210157. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0157-2021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Singh, J, Towns, S, Jayasuriya, G, Hunt, S, Simonds, S, Boyton, C, et al.. Transition to adult care in cystic fibrosis: the challenges and the structure. Paediatr Respir Rev 2022;41:23–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2020.07.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Gravelle, AM. Bridging pediatric and adult healthcare settings in a nurse-led cystic fibrosis transition intiative. In: Betz, C, Coyne, I, editors. Transition from pediatric to adult healthcare services for adolescents and young adults with long-term conditions: an international perspective on nurses’ roles and interventions. Cham: Springer Cham; 2020:229–54 pp.10.1007/978-3-030-23384-6_10Search in Google Scholar

48. Quittner, AL, Goldbeck, L, Abbott, J, Duff, A, Lambrecht, P, Solé, A, et al.. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis and parent caregivers: results of the International Depression Epidemiological Study across nine countries. Thorax 2014;69:1090–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205983.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Jamieson, N, Fitzgerald, D, Singh-Grewal, D, Hanson, C, Craig, J, Jaure, A. Children’s experiences of cystic fibrosis: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics 2014;133:e1683–97. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Gramegna, A, Addy, C, Allen, L, Bakkeheim, E, Brown, C, Daniels, T, et al.. Standards for the care of people with cystic fibrosis (CF); Planning for a longer life. J Cyst Fibros 2024;23:375–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2024.05.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Coyne, B, Hallowell, SC. Measurable outcomes for transition: the nurses’ role. In: Betz, CL, Coyne, IT, editors. Transition from pediatric to adult healthcare services for adolescents and young adults with long-term conditions: an international perspective on nurses’ roles and interventions. Cham: Springer Cham; 2020:111–25 pp.10.1007/978-3-030-23384-6_5Search in Google Scholar

52. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social services. NICE guideline; 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng43/resources/transition-from-childrens-to-adults-services-for-young-people-using-health-or-social-care-services-pdf-1837451149765.Search in Google Scholar

53. Pape, L, Ernst, G. Health care transition from pediatric to adult care: an evidence-based guideline. Eur J Pediatr 2022;181:1951–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04385-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Middour-Oxler, B, Bergman, S, Blair, S, Pendley, S, Stecenko, A, Hunt, WR. Formal vs. informal transition in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective comparison of outcomes. J Pediatr Nurs 2022;62:177–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2021.06.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Chaudhry, SR, Keaton, M, Nasr, SZ. Evaluation of a cystic fibrosis transition program from pediatric to adult care. Pediatr Pulmonol 2013;48:658–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.22647.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Castellani, C, Duff, AJA, Bell, SC, Heijerman, HGM, Munck, A, Ratjen, F, et al.. ECFS best practice guidelines: the 2018 revision. J Cyst Fibros 2018;17:153–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2018.02.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Flewelling, KD, Sellers, DE, Sawicki, GS, Robinson, WM, Dill, EJ. Social support is associated with fewer reported symptoms and decreased treatment burden in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2019;18:572–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2019.01.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Bregnballe, V, Schiøtz, PO, Lomborg, K. Parenting adolescents with cystic fibrosis: the adolescents’ and young adults’ perspectives. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011;5:563–70. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S25870.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Bourke, M, Houghton, C. Exploring the need for Transition Readiness Scales within cystic fibrosis services: a qualitative descriptive study. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:2814–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14344.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Dudman, L, Rapley, P, Wilson, S. Development of a transition readiness scale for young adults with cystic fibrosis: face and conten validity. Neonatal Paediatr Child Health Nurs 2011;14:9–13.Search in Google Scholar

61. Killackey, T, Nishat, F, Elsman, E, Lawson, E, Kelenc, L, Stinson, JN. Transition readiness measures for adolescents with chronic illness: a scoping review of new measures. Health Care Transitions 2023;1:100022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hctj.2023.100022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62. Dixon, E, Dick, K, Ollosson, S, Jones, D, Mattock, H, Bentley, S, et al.. Telemedicine and cystic fibrosis: DO we still need face-to-face clinics? Paediatr Respir Rev 2022;42:23–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2021.05.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Stein, RE, Riessman, CK. The development of an impact-on-family scale: preliminary findings. Med Care 1980;18:465–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198004000-00010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Lang, S, Brandstetter, S, Kiefer, A. Belastungssituation von Familien mit an Mukoviszidose erkrankten Kindern und Jugendlichen. In: Mukoviszidose, e.V, Bundesverband, CF, editors. Abstractband zur Deutschen Mukoviszidose Tagung. Bonn; 2023:23–5 pp. 37-8. https://www.muko.info/fileadmin/user_upload/was_wir_tun/dmt/dmt_2023_abstractband.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

65. Pyo, J, Lee, W, Choi, EY, Jang, SG, Ock, M. Qualitative research in healthcare: necessity and characteristics. J Prev Med Public Health 2023;56:12–20. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.22.451.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

66. Williams, V, Boylan, AM, Nunan, D. Critical appraisal of qualitative research: necessity, partialities and the issue of bias. BMJ Evid Based Med 2020;25:9–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111132.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Physical Activity, Sleep, and Lifestyle Behaviours

- Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its association with hypertension among young adults in urban Meghalaya: a cross sectional study

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Psychosocial predictors of adolescent stress: insights from a school-going cohort

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Barriers and facilitators in the transition from pediatric to adult care in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe – a qualitative systematized review

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Self-care or self-risk? examining self-medication behaviors and influencing factors among young adults in Bengaluru

- Health Equity and Access to Care

- Clinical heterogeneity of adolescents referred to paediatric palliative care; a quantitative observational study

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- ‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Physical Activity, Sleep, and Lifestyle Behaviours

- Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its association with hypertension among young adults in urban Meghalaya: a cross sectional study

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Psychosocial predictors of adolescent stress: insights from a school-going cohort

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Barriers and facilitators in the transition from pediatric to adult care in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe – a qualitative systematized review

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Self-care or self-risk? examining self-medication behaviors and influencing factors among young adults in Bengaluru

- Health Equity and Access to Care

- Clinical heterogeneity of adolescents referred to paediatric palliative care; a quantitative observational study

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- ‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping