‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping

-

Virginia F. Byron

, Richard Lopez

Abstract

The transition from adolescence to young adulthood presents an opportunity for health promotion and illness prevention. However, the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare services is complex and exposes systemic vulnerabilities in the healthcare system, particularly in access to care for marginalized youth. There exist high rates of discontinuity in primary care for young adults, amplifying health disparities. In the final stages of the transition process, the transfer to adult healthcare services is critical to continuity of care. There is a need to better understand and address access to care issues for young adults. This study explores barriers and facilitators to access to primary care for young adults in an urban Latinx community through community-based participatory research (CBPR) and youth participatory action research (YPAR). This study was developed in partnership with a hospital-affiliated community-based youth program and youth research leaders. Group concept mapping methodology was used to structure discussions with the organization’s youth and staff members. Results indicate that the highest priority factors for young adults in seeking primary care are related to the culture of the clinical setting, including intangible factors such as “respect by front desk staff” and “relationship with provider.” These factors are also perceived by young adults to be more feasible targets for improvement as opposed to, for example, insurance coverage. The findings provide a roadmap to advocate for interventions to transform young adult services within the healthcare system as well as a framework for integrating youth voices and leadership into the research process.

Introduction

Young adults’ access to care

Young adulthood is a critical period for establishing lifelong health behaviors, presenting an important opportunity for healthcare providers to engage and support young people through routine care [1], 2]. Recommended preventive health care for young adults (approximately 18–26 years of age) includes screening for non-communicable and infectious diseases, mental health care, vaccinations, family planning, and health education [3]. However, the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare services is also a point of vulnerability for access, resulting in high rates of discontinuity in care, especially for primary care and preventive health services. Upon aging out of usual sources of care (i.e. pediatric practices or school-based health centers), many young adults face barriers to accessing adult-centered health services. As the final stage of the transition process, transfer to adult health services is critical to continuity of care. There is a need to better understand and address primary care access for young adults.

A growing body of literature has documented a drop off in numerous health indicators for young adults as compared to adolescents, including health risk behaviors and access to care [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Young adults have higher emergency department utilization rates with disparities along gender and racial lines; nearly half of the care delivered to young Black men takes place in emergency departments [12], 13]. Young adults face structural barriers in initiating adult healthcare services, including disruptions in insurance coverage, housing, employment and educational status. Further challenges arise from learning to navigate and initiate care independently from parents and caregivers [1]. Existing health disparities are perpetuated, if not amplified, along racial and economic lines in this transition to adult health care, with particularly low rates of preventive health services delivered to young Black and Latino men [14], 15].

Conceptual framework: youth-engaged research

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach to scientific investigation and program development that is based on partnership and collaboration between researchers and communities at every stage of the research process [16]. A subset of CBPR, youth participatory action research (YPAR), centers youth as experts in their own lived experiences and integrates youth-led advocacy based on study findings [17]. Both CBPR and YPAR provide avenues for capacity building and positive youth development through community-academic partnerships [18]. In the “action” stage of YPAR, youth partners leverage the study outcomes to create transformative change in their community. Through the process of YPAR, youth participants gain skills and experience in academic inquiry and civic engagement, while building social connections and developing self-efficacy.

Group concept mapping

Group concept mapping (GCM) is a mixed-methods participatory methodology that has been previously applied in CBPR and YPAR studies [19], 20]. GCM inherently centers the lived experiences and priorities of participant-researchers through a series of two participatory activities: (1) group idea generation (i.e. brainstorming) and (2) individual data structuring and rating. The resulting “concept map” is a graphical representation of the themes that emerged during the group discussions, as interpreted by the participants. GCM has been used to engage adolescents and young adults in studies focused on community health, health equity, program design, and health risk behaviors [20], [21], [22], [23].

Materials and methods

This project was developed in collaboration with a hospital-affiliated community-based youth program in New York City, referred to as “The Hub.” All recruitment and study methods took place at The Hub. The Hub provides positive youth development services, mentoring, and mental health support for youth ages 14–24 years. Although proximately located to a hospital complex, The Hub does not provide clinical healthcare services outside of mental health care. Youth are connected to The Hub through community outreach or through direct referral from hospital-affiliated clinical services. Upon enrollment, members are paired with an “advocate,” a staff member who is available to meet regularly with the member to connect them with services and programs, advise on educational and career paths, or assist with health system navigation. Members of The Hub have access to on-site mental health services through staff psychologists and group sessions. Regular programming includes health education seminars, social events, cooking classes, and art workshops.

The focus of this study was developed in discussions with staff members of The Hub who work directly with the youth members. Staff members identified an increased need for health system navigation among older members of The Hub (18–24 year olds) associated with the transfer from from pediatric to adult primary care. Members of The Hub’s Youth Council then co-developed the group brainstorming prompt. Two youth members of The Hub were hired and trained to be youth research leaders (authors JS and AM), and, along with the director of The Hub (author RL), were involved in each step of the research process.

Participants were recruited from the youth membership and adult staff of The Hub. Youth members aged 18–24 years were eligible (Hub membership ends at 24 years old), and all staff members were eligible. Participants were recruited through The Hub membership network by word-of-mouth, emails, paper fliers posted in The Hub space, and social media. All eligible youth members and staff of The Hub were English-speaking. The study materials and procedures were IRB approved. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was performed in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki ethical standards. Participants were compensated $30 in the form of cash gift cards for each of the two activities that they took part in.

Group concept mapping (GCM) was used to generate, structure, and analyze perspectives on access to primary care for young adults across two participatory sessions: (1) group brainstorming (idea generation) and (2) individual sorting and rating (data structuring). Two group brainstorming sessions were conducted in February 2023, one for The Hub youth members, and one for adult staff members; both were co-facilitated by youth research leader JS. The youth session took place in-person at The Hub, and the staff session was conducted virtually via video conference, using the cloud-based brainstorming platform Google Jamboard [24]. Participants were first led through a warm-up exercise to provide context of primary care for young adults, exploring reasons for seeking care, settings for receiving services, and the steps involved in accessing care. Participants were then asked to generate responses to the prompt “what things make it easier or harder for young adults to go to the doctor?” Participants recorded individual responses on sticky notes or spoke them aloud to the research staff, who transcribed the statement onto sticky notes. Notes were posted for display on a wall during the youth session, and on the virtual Jamboard during the staff session. Responses were clarified by participants at the request of study staff when necessary (i.e. “What did you mean when you wrote ‘transportation’?”).

Responses generated in both youth and staff group brainstorming sessions were compiled for “cleaning” by the research team. Statements were edited for clarity, neutrality, and redundancy, removing valenced language and consolidating duplicate or similar statements to create a set of items of comparable level of specificity, that encompassed all of the ideas that emerged in discussion. For example, the statements “friendly staff” and “rude staff” became “staff characteristics.” This final list of statements was entered into the groupwisdom™ concept mapping web-based platform [25] for use in the sorting and rating phase.

The sorting and rating session, conducted in April 2023, consisted of a web-based activity using the groupwisdom™ platform. Participants were again recruited from youth membership, those ages 18–24 years, and from the staff. They were not required to have participated in the prior group brainstorming session. This activity was conducted primarily in-person at The Hub facility on laptops supplied by The Hub, although one participant completed the activity on a personal device offsite. Participants were each asked to sort the finalized statements into clusters based on what they determined to be related topics or themes. Then, they were asked to rate each statement on a scale of 1 (least important or feasible) to 5 (most important or feasible) for the following two questions: “How important is it to you to intervene on this item?” and “how feasible do you think it would be to intervene on this item, if you were in charge of a clinic?”

Data analysis

The GCM methodology combines qualitative data collection with quantitative data analysis. Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) were conducted using the groupwisdom™ software. Responses from the sorting activity are aggregated and converted into quantitative data in the form of a similarity matrix, which assigns a binary value based on whether any two given statements were sorted together in each potential instance. MDS is used to assign each point a coordinate on an x-y graph to spatially represent the “closeness” of each statement to each other statement based on the similarity matrix. Then, HCA is applied to the basic point map to create clusters of the most closely related points, typically resulting in several cluster models. A best-fit cluster map is a graphical representation of the themes that emerged in discussion, as interpreted by each participant [4], 5]. The stress value is the metric used to determine the appropriateness of fit of the multi-dimensional scaling solution to the original similarity matrix. Values typically fall between 0.20 and 0.35, with a lower value indicating a closer fit, i.e. less stress [26].

As opposed to the cluster map, which graphically represents the themes that emerged in the brainstorming session, the go-zone map assigns each statement a spatial coordinate based on its average value for two rating variables along the X-Y axes, which in this study were “importance” and perceived “feasibility” for intervention. The go-zone map provides valuable information about the priorities that the participant group places on each statement, as a product of its importance and feasibility ratings. A pattern match analysis can be used to compare ratings between two participant groups.

Results

A total of 25 participants took part in the study across the two activities, including 17 youth (mean age 21 years, range 18–23) and 8 staff members (mean age 33 years, range 27–41). In total, 16 participants (10 youth and 6 staff) took part in the group brainstorming activity and 18 participants (12 youth and 6 staff) participated in the sorting and rating activity; 9 participants completed both activities. Overall, participants were 40 % cis-female, 52 % cis-male, and 8 % non-binary. Based on self-reported race/ethnicity, participants were 92 % Latinx (including 36 % Black) and 8 % Asian. All youth participants identify as Latinx and 15 out of 17 reported speaking Spanish or English+Spanish at home. Most participants lived in Upper Manhattan or The Bronx. All participants reported having active health insurance coverage (52 % public, 40 % commercial, 8 % unsure of type), and 76 % reported having completed an annual physical in the past year.

In total, 130 responses were generated from both the youth and staff group brainstorming sessions. Statements were then consolidated and edited for clarity, neutrality, and redundancy, resulting in a final set of 34 distinct statements. Responses that were phrased in the form of specific solutions or suggestions for improvement (i.e. “clinics should have printers available for use to print out school forms”), were removed and set aside to be referenced in the advocacy phase.

Sorting and rating data were assessed for validity by the research team and removed from analysis (n=6 of 18 for sorting responses, all youth participants) if not valid. For example, instead of following the instructions to sort statements into clusters based on the related meanings of statements, a few participants sorted statements based on value (i.e. “important to me,” “not important to me”). One rating response was excluded based on the participant entering the same rating response across all statements.

Concept map

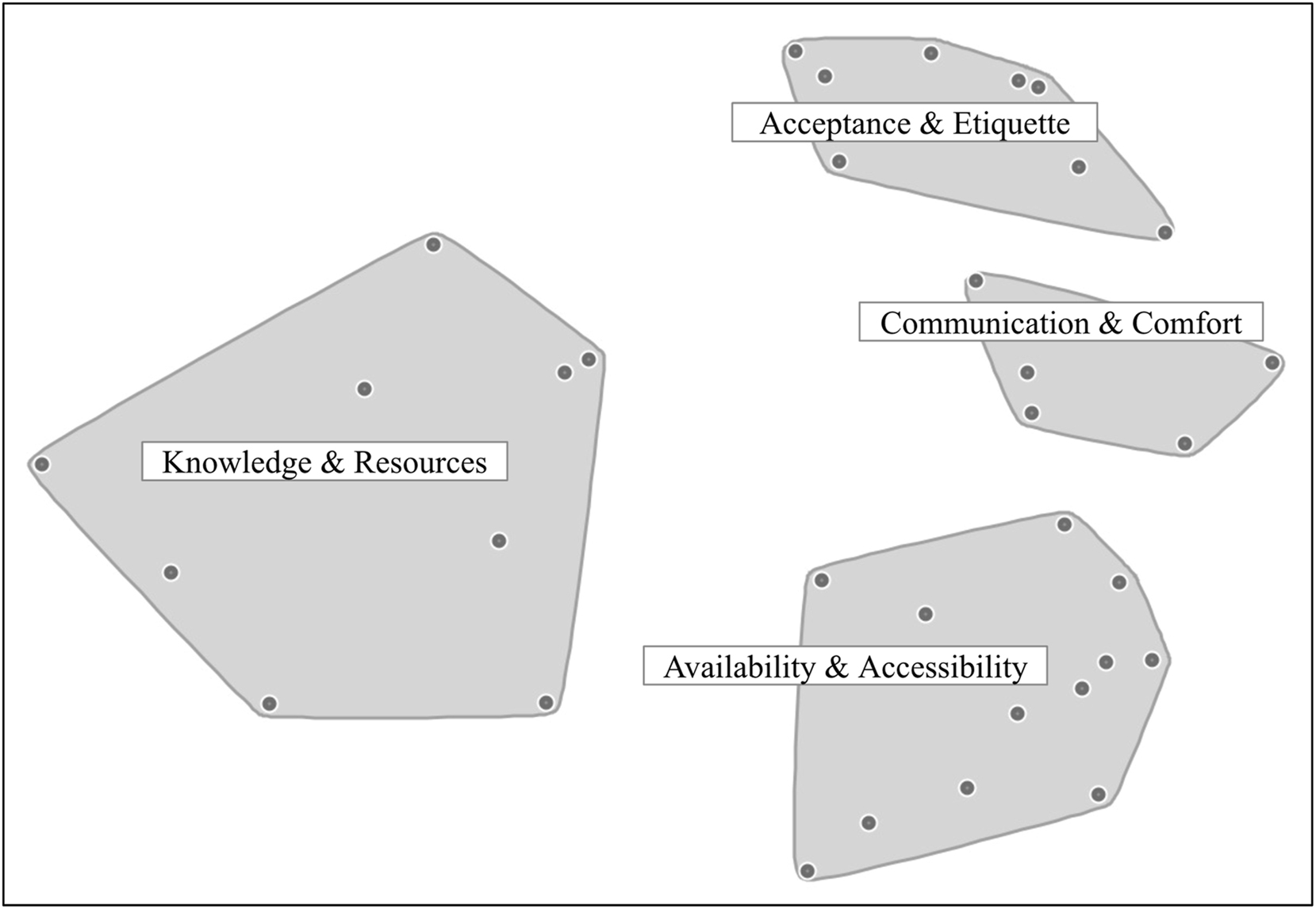

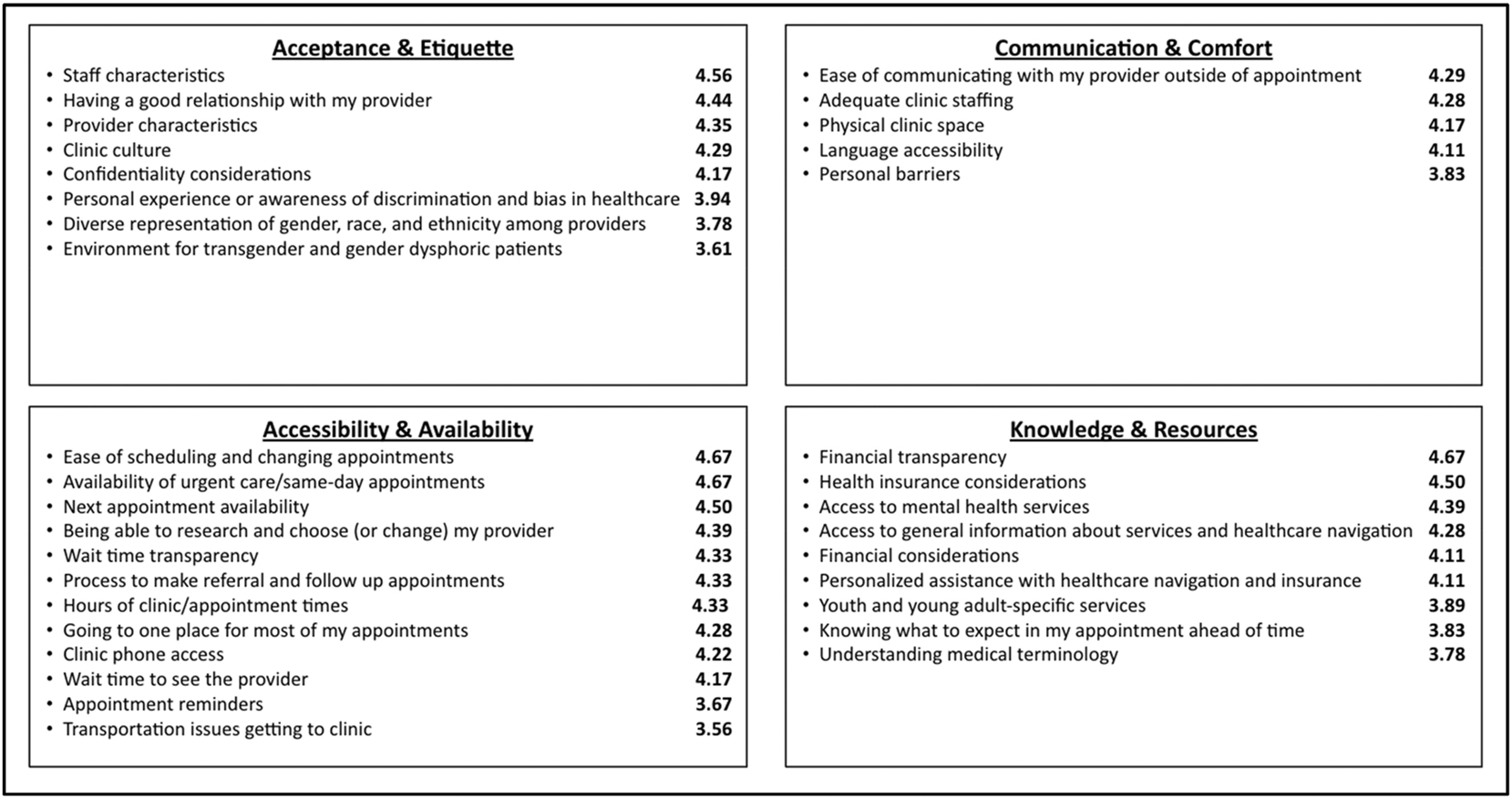

A 4-cluster arrangement was determined to be the best fit concept map (Figures 1A and 1B). The stress value for the chosen map was 0.21, within the range of interpretable values, indicating an acceptable fit [26], 27]. Four topic clusters emerged: Acceptance & Etiquette; Communication & Comfort; Availability & Accessibility; and Knowledge & Resources.

Acceptance & Etiquette: This theme captured intangible characteristics of the patient experience, including interpersonal interactions with clinical staff and healthcare providers, and cues that contributed to participants feeling respected and welcome within the clinical space, particularly with regards to identity (i.e. gender identity or race/ethnicity). Included in this theme was also the patient’s comfort seeking care in general, and medical mistrust based on negative personal experience or accounts from family, friends, or in the media (e.g. news coverage of physician abuse cases).

Communication & Comfort: This theme encompassed the operations of the clinical office as perceived by the patient, from a sense that the clinical office was adequately staffed, to language services and the physical environment (e.g. clean, well-furnished).

Availability & Accessibility: This theme encompassed statements related to clinical care access, including the process of making appointments (including same day/urgent care appointments, follow up appointments, and referral appointments within the system), availability of appointments, and contacting the clinical office. Also included in this theme were transportation to clinical space, having a medical home (multiple specialties in one place), and having agency over provider choice.

Knowledge & Resources: This theme reflected the need for ancillary services directed towards young adults, including education around available services, healthcare navigation support, and insurance navigation. Many participants referred to their assigned “advocate,” a service provided through The Hub that pairs youth members with a staff member who are equipped to answer questions regarding healthcare navigation. The item with the highest importance rating in this theme was “financial transparency,” referring to an expressed fear of surprise billing and a lack of information about cost of services, which participants stated was a barrier to accessing care.

Cluster map. Each cluster represents a theme that emerged from group discussion and analysis. Each point represents a statement. Stress value of 0.21 indicates an acceptable fit for this particular solution. Points are geographically located on the map based on multi-dimensional scaling analysis that averages all valid cluster activity responses. Points that are closer together were more frequently clustered together in the participant responses.

Statements by cluster. Statements are listed in full, organized by cluster topic, with statements ordered by average importance rating (on 1–5 scale), listed to the right of each statement.

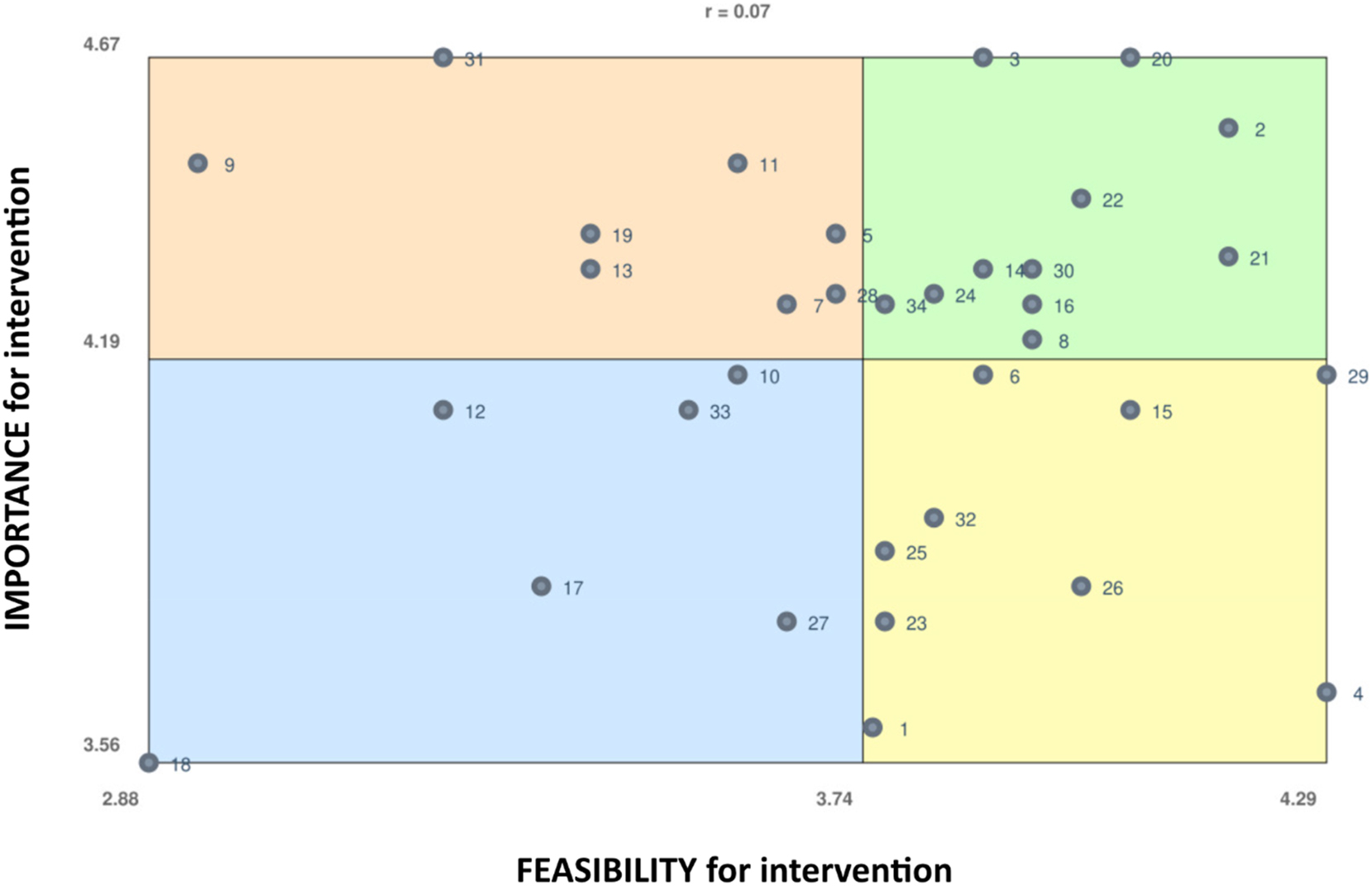

Go-zone map

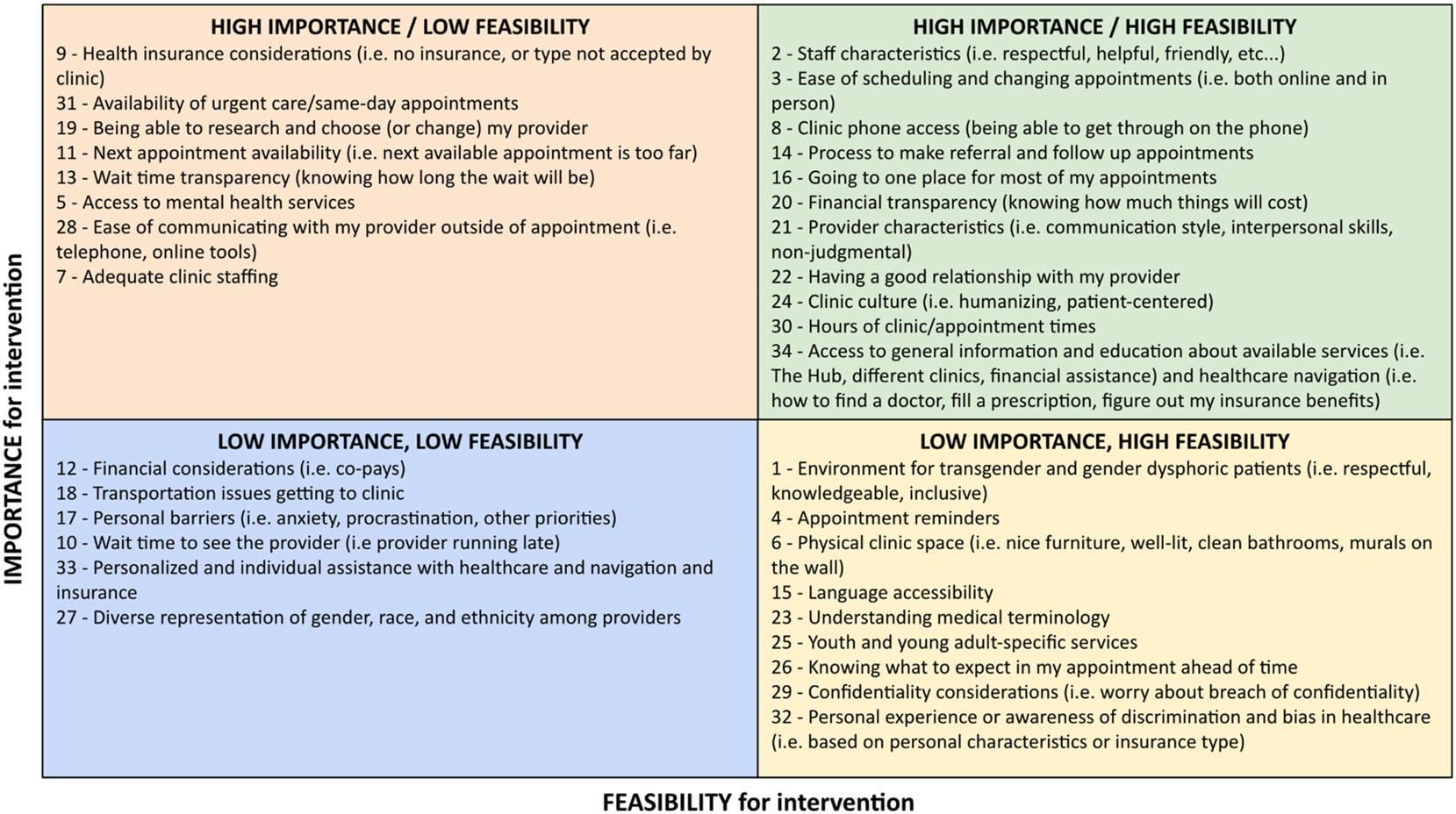

The go-zone map (Figures 2A and 2B) positions each statement as a coordinate on a spatial plane based on the average participant ratings for “feasibility for intervention” (X axis) and “importance for intervention” (Y axis). The plane is then divided into quadrants “low feasibility/low importance,” “low feasibility/high importance,” “high feasibility/low importance,” and “high feasibility/high importance.” The statements in the “high feasibility/high importance” category can be considered to be the highest priority for intervention.

Go-zone map. Coordinates are based on each statement’s average rating for “importance for intervention” (Y-axis) and “feasibility for intervention” (X-axis), on a 5 point scale. Statements are numbered for reference in Figure 2B. The correlation value is 0.07, indicating no predictable correlation between the two variables.

Statements by go-zone quadrant. Statements (numbered) are listed in full, grouped by quadrant of the go-zone map.

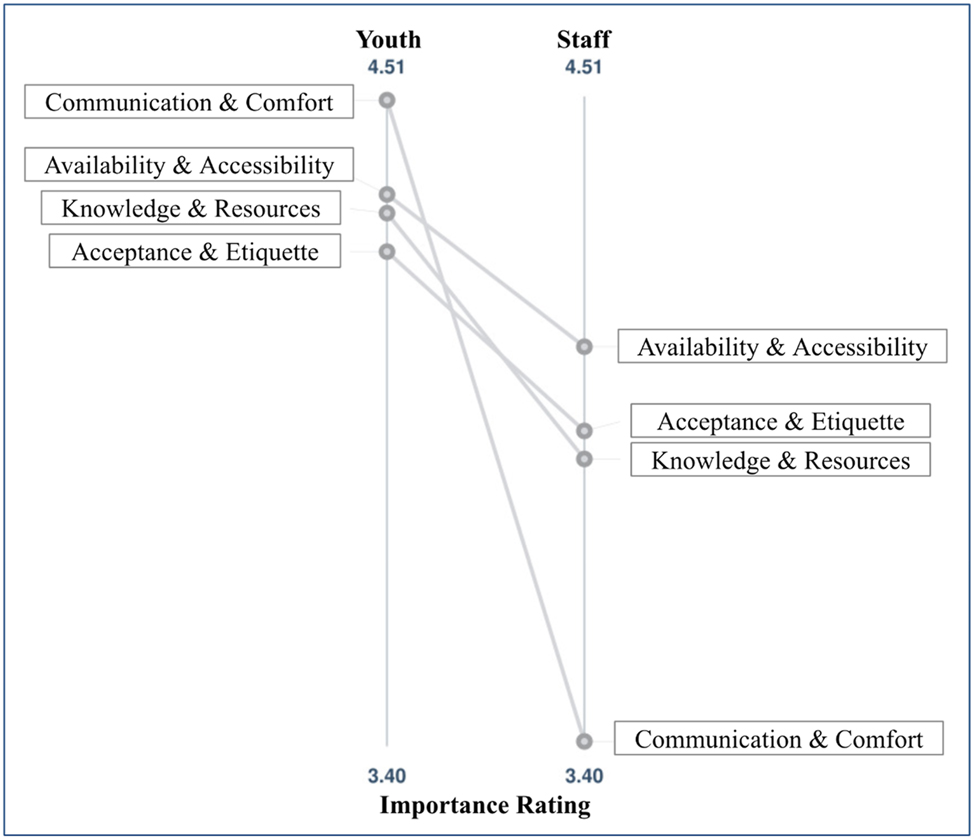

Pattern match

The pattern match graph (Figure 3) compares cluster ratings between two groups. Here, we compare importance ratings between youth and staff participants. The two main findings are that the youth ratings are consistently higher (on a 1–5 scale) than the staff ratings, and that the most discordant importance rating between the two groups is for the “Communication & Comfort” cluster, which contains the items “ease of communicating with my provider,” “physical clinical space (i.e. nice furniture, clean bathrooms, murals on the wall),” “adequate clinic staffing,” “language accessibility,” and “personal barriers.”

Pattern match for importance, youth vs. staff. The pattern match graph compares youth and staff importance ratings for each cluster.

Youth-led interpretation

The study results were presented to The Hub youth and staff in March 2024 for further discussion and interpretation. In discussion groups led by youth researcher leaders, The Hub youth members who attended (8 in total, ages 19–24 years, 3 of whom participated in the prior study methods) generated labels for the concept map clusters, and discussed the overarching themes that emerged from the data, which one participant summarized as “we need transparency and communication to build trust.” Youth then generated several recommendations for interventions to present to hospital system stakeholders, which were subsequently presented to clinician and administration stakeholders to advocate for changes to improve access to care for young adults. These proposals include a text-based notification system that would allow patients to know when they are next in line to see the clinician when appointments are delayed, an “office hours” feature for sending messages to their provider during which they can expect an immediate response, and a web-based educational repository to learn the basics of healthcare navigation (including how to make an appointment, find a provider, manage prescriptions, and navigate insurance benefits).

Discussion

Access to preventive healthcare services declines in young adulthood, contributing to health disparities, particularly affecting young people of color. Our study explores the factors that affect access to primary care services for young adults through partnering with a youth-serving organization, training and empowering youth researchers, and engaging young adults in a participatory research method. Youth participants were largely bilingual, from Spanish-speaking immigrant families. Partnering with young adults to explore the barriers and facilitators to healthcare access is crucial in understanding and addressing these factors to transform healthcare systems to meet the needs of young people. The existing literature on transition of care centers more extensively on issues affecting youth with special healthcare needs (i.e. condition-specific transition programs); to our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to use participatory methods to explore the transfer from pediatric to adult primary care.

Our study found four main themes that affect access to care for young adults: Acceptance & Etiquette; Communication & Comfort; Availability & Accessibility; and Knowledge & Resources. Factors identified as highest priority (both important and feasible) were primarily non-tangible characteristics of the clinical environment, such as staff friendliness, clinic office culture and values, relationship with providers, and ease of communication. Young adults also identified several factors of high importance but low perceived feasibility, including health insurance considerations, being able to change providers easily, access to mental health services, and clinical staffing considerations. Factors that were identified by participants as lower importance included wait times to see a provider. Comparison of importance ratings by staff and youth showed a disconnect that was most stark with the Communication & Comfort cluster, relating to communication with providers outside of appointment times and physical clinical spaces, underscoring the need to center youth voices in designing these systems. Overall, participants expressed a need for resources and guidance to develop the skills to independently navigate the healthcare system. This, along with a desire for financial transparency (i.e. knowing upfront the costs of seeking care) and ease of communication with their providers, was summarized succinctly by one participant in the youth-led interpretation session: “We need transparency and communication to build trust.”

Youth participatory action research

Youth participatory action research (YPAR), as a variant of community-based participatory research (CBPR), has utility beyond the descriptive research outcomes. The process of involving youth participants as leaders and co-researchers builds capacity through several avenues. In our project, one youth leader (JS) was trained in research ethics and methods, co-led participant activities, was active in data analysis, and presented findings at a research symposium. A second youth leader (AM) was actively involved in preparation for participant sessions and data analysis. Both youth leaders facilitated the youth participatory interpretation sessions, presenting results to participants and eliciting their perspectives and interpretation of results. The participants themselves were exposed to the process of academic inquiry through transparent and participatory study processes and were active in interpreting the results through a youth-led participatory interpretation session. While we did not evaluate the impacts of study participation, previous studies have shown YPAR to increase self-efficacy, empowerment, and civic participation among participants [28].

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the study is that participants represented a group of young adults from demographic backgrounds that historically face numerous barriers to health access; nearly all participants identified as Latinx or Black-Latinx and live in Spanish-speaking households in low-income urban neighborhoods. All study activities took place at the Uptown Hub facility where participants were familiar and comfortable in the setting. One limitation, however, is that by partnering with a youth-serving program affiliated with a large healthcare system, we may have selected for participants who are more connected to care than demographically similar youth in New York City. While The Hub does not provide clinical services aside from mental health care, they do provide healthcare navigation support including assistance with insurance enrollment. Since all participants reported having health insurance coverage, this study did not capture the experiences of uninsured young adults, a group who face significant barriers to healthcare access. We hypothesize that non-Hub connected youth in the community experience at least these barriers, and likely more.

Limitations to the methodologic design included the observed cognitive difficulty of the sorting and rating activity, which was a barrier to collecting valid data from several participants, as evidenced by several invalid responses to the sorting activity. In future studies with a similar population, we would spend more time reviewing the instructions, sharing examples, and having participants practice the activity before completing it. In order to mitigate anticipated task fatigue, we limited the number of statements for the sorting and rating task to 34, which is smaller than other studies with similar populations. Some of the items that were rated lower for “importance”, including language access, accessibility, and clinical environment for non-binary and transgender individuals, were likely affected by low representation among the participant group, of which there were fewer gender expansive participants, with all participants being fluent in English. While this study did include the perspectives of adult staff members who work closely with youth on matters related to health system navigation, future studies could explore including the perspectives of caregivers and healthcare providers who care for young adults.

Summary

This paper contributes to the growing body of literature on transition of care for adolescents and young adults, with a unique focus on the transfer to adult-focused services by exploring access to primary care and preventive services for young adults from a Latinx urban community, who face many structural barriers to healthcare access. This study provides a framework for applying YPAR to questions of healthcare access, prioritizing the experiences and priorities of young adults through participatory research methods in partnership with a youth-serving organization. Our findings provide valuable information for stakeholders in the local healthcare context in the form of clear and actionable next steps for transforming health services for young adults. Our hope is that future research will apply this and other creative approaches to amplify the voices of young people and build partnerships to create transformative change in our healthcare system in pursuit of health equity.

Funding source: Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University

Award Identifier / Grant number: Lawrence R. Stanberry Fellowship Research Grant

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the youth members and staff of The Uptown Hub of NewYork-Presbyterian for enthusiastically supporting this project, particularly Luis Acevedo for facilitating the study sessions. We would also like to acknowledge Nick Szoko, Renata Schiavo, Dodi Meyer, and Marina Catallozzi for their advice and support in the conceptualization of this project.

-

Research ethics: The protocol was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board, #AAAU1384.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI, and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interests: Author RL is employed as the Program Director of The Uptown Hub. JS and AM are Youth Members of The Uptown Hub.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Lawrence R. Stanberry Fellowship Research Grant from the Department of Pediatrics of Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Committee on Improving the Health, Safety, and Well-Being of Young Adults, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Institute of Medicine, National Research Council. Investing in the health and well-being of young adults [Internet]. In: Bonnie, RJ, Stroud, C, Breiner, H, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK284787/ [Accessed 17 May 2022].Suche in Google Scholar

2. Graves, L, Leung, S, Raghavendran, P, Mennito, S. Transitions of care for healthy young adults: promoting primary care and preventive health. South Med J 2019;112:497–9. https://doi.org/10.14423/smj.0000000000001017.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Ozer, EM, Urquhart, JT, Brindis, CD, Park, MJ, Irwin, CE. Young adult preventive health care guidelines: there but can’t be found. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:240–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.794.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Harris, KM, Gordon-Larsen, P, Chantala, K, Udry, JR. Longitudinal trends in race/ethnic disparities in leading health indicators from adolescence to young adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:74–81. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.160.1.74.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Park, MJ, Paul Mulye, T, Adams, SH, Brindis, CD, Irwin, CE. The health status of young adults in the United States. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2006;39:305–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Park, MJ, Scott, JT, Adams, SH, Brindis, CD, Irwin, CE. Adolescent and young adult health in the United States in the past decade: little improvement and young adults remain worse off than adolescents. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2014;55:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Adams, SH, Park, MJ, Twietmeyer, L, Brindis, CD, Irwin, CEJ. Young adult preventive healthcare: changes in receipt of care pre- to post-affordable care act. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2019;64:763–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.12.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Irwin, CE. Young adults are worse off than adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2010;46:405–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Callahan, ST, Cooper, WO. Changes in ambulatory health care use during the transition to young adulthood. J Adolesc Health 2010;46:407–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.09.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Neinstein, LS, Irwin, CE. Young adults remain worse off than adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2013;53:559–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Stroud, C, Walker, LR, Davis, M, Irwin, CE. Investing in the health and well-being of young adults. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:127–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.11.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Fortuna, RJ, Robbins, BW, Mani, N, Halterman, JS. Dependence on emergency care among young adults in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:663–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1313-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Lau, JS, Adams, SH, Boscardin, WJ, Irwin, CE. Young adults’ health care utilization and expenditures prior to the Affordable Care Act. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2014;54:663–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Callahan, ST, Hickson, GB, Cooper, WO. Health care access of Hispanic young adults in the United States. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2006;39:627–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Fortuna, RJ, Robbins, BW, Halterman, JS. Ambulatory care among young adults in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:379–85. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-00002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Wallerstein, N, editor. Community-based participatory research for health: advancing social and health equity, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley; 2017:1 p.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Ozer, EJ, Abraczinskas, M, Duarte, C, Mathur, R, Ballard, PJ, Gibbs, L, et al.. Youth participatory approaches and health equity: conceptualization and integrative review. Am J Community Psychol 2020;66:267–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12451.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Lincoln, AK, Borg, R, Delman, J. Developing a community-based participatory research model to engage transition age youth using mental health service in research. Fam Community Health 2015;38:87–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/fch.0000000000000054.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Minh, A, Patel, S, Bruce-Barrett, C, O’Campo, P. Letting youths choose for themselves: concept mapping as a participatory approach for program and service planning. Fam Community Health 2015;38:33. https://doi.org/10.1097/fch.0000000000000060.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Vaughn, LM, Jones, JR, Booth, E, Burke, JG. Concept mapping methodology and community-engaged research: a perfect pairing. Eval Progr Plann 2017;60:229–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.013.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Baskin, ML, Dulin-Keita, A, Thind, H, Godsey, E. Social and cultural environment factors influencing physical activity among African-American adolescents. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2015;56:536–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Hiler, M, Spindle, TR, Dick, D, Eissenberg, T, Breland, A, Soule, E. Reasons for transition from electronic cigarette use to cigarette smoking among young adult college students. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2020;66:56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Ridings, JW, Powell, DM, Johnson, JE, Pullie, CJ, Jones, CM, Jones, RL, et al.. Using concept mapping to promote community building: the African American initiative at Roseland. J Community Pract 2008;16:39–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705420801977890.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Jamboard. Google; 2017 (Google Workspace).Suche in Google Scholar

25. The Concept System® groupwisdomTM [Internet]. Ithaca, NY: Concept Systems, Incorporated; 2022. Available from: https://www.groupwisdom.tech.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Kane, M, Rosas, S. Conversations about group concept mapping: applications, examples and enhancements. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2018:226 p.10.4135/9781506329161Suche in Google Scholar

27. Rosas, SR, Kane, M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Progr Plann 2012;35:236–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Ozer, EJ, Douglas, L. The impact of participatory research on urban teens: an experimental evaluation. Am J Community Psychol 2013;51:66–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9546-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Physical Activity, Sleep, and Lifestyle Behaviours

- Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its association with hypertension among young adults in urban Meghalaya: a cross sectional study

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Psychosocial predictors of adolescent stress: insights from a school-going cohort

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Barriers and facilitators in the transition from pediatric to adult care in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe – a qualitative systematized review

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Self-care or self-risk? examining self-medication behaviors and influencing factors among young adults in Bengaluru

- Health Equity and Access to Care

- Clinical heterogeneity of adolescents referred to paediatric palliative care; a quantitative observational study

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- ‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Effects of anti-obesity drugs on cardiometabolic risk factors in pediatric population with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Physical Activity, Sleep, and Lifestyle Behaviours

- Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its association with hypertension among young adults in urban Meghalaya: a cross sectional study

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Psychosocial predictors of adolescent stress: insights from a school-going cohort

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Barriers and facilitators in the transition from pediatric to adult care in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe – a qualitative systematized review

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Self-care or self-risk? examining self-medication behaviors and influencing factors among young adults in Bengaluru

- Health Equity and Access to Care

- Clinical heterogeneity of adolescents referred to paediatric palliative care; a quantitative observational study

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- ‘We need transparency and communication to build trust’: exploring access to primary care services for young adults through community-based youth participatory action research and group concept mapping