Abstract

In this work, microwave energy is used for preparing a granular red mud (GRM) adsorbent made of red mud with different binders, such as starch, sodium silicate and cement. The effects of the preparation parameters, such as binder type, binder addition ratio, microwave heating temperature, microwave power and holding time, on the absorption property of GRM are investigated. The BET surface area, strength, pore structure, XRD and SEM of the GRM absorbent are analyzed. The results show that the microwave roasting has a good effect on pore-making of GRM, especially when using organic binder. Both the BET surface area and the strength of GRM obtained by microwave heating are significantly higher than that by conventional heating. The optimum conditions are obtained as follows: 6:100 (w/w) of starch to red mud ratio, microwave roasting with a power of 2.6 kW at 500℃ for holding time of 30 min. The BET surface area, pore volume and average pore diameter of GRM prepared at the optimum conditions are 15.58 m2/g, 0.0337 cm3/g and 3.1693 A0, respectively.

Introduction

Red mud, a solid waste generated in alumina refining from bauxite, is the most serious pollution sources of alumina plant. Due to its high alkalinity (pH = 10 ~ 12.5), red mud belongs to hazardous waste [1]. At present, not only does the large amount of red mud take up much land but also cause serious environmental pollution problems [2, 3].

In recent years, red mud has been successfully applied in the production of building materials such as cement, glass, etc. [4, 5], or extracting valuable metals [6, 7]. Moreover, numerous studies have examined the use of red mud as an adsorbent purification of heavy metal wastewater [8, 9] and dye wastewater treatment [10, 11]. Currently, various activation methods including acid treated [12–15], heat treated [16–18], acid–heat-treated [19, 20] schemes have been developed to improve the adsorption capacity of red mud.

As a kind of new green activation way, the microwave pore-making and activation method (MPA) is significantly different with conventional method [21]. The principle of MPA process lies in that microwave energy can selectively and quickly act with water, organics and the high-microwave-adsorption solids existing in the material, which can explosively make tiny pore and channel generated because of water evaporation and organics volatilization. Thus the process can activate the adsorption characteristics and increase the strength of the material. It can become a porous adsorbent with high strength. Li and Zhao [22] investigated that the removal efficiency of chromium from its solution by microwave-activated powder red mud could reach over 99% in the range of Cr3+ ≤ 300 mg/L when the red mud heated for 30 min at 800 W. Cheng Gong et al. [23] presented that microwave-activated red mud had a good adsorption capacity for disperse brilliant blue E-4R with 42.19 mg/g. The removal efficiency could reach 99.07% under the optimum conditions. These studies indicated that microwave activation technology had good effect to prepare red mud porous adsorbent material. However, the adsorption capacity of microwave activated red mud is mainly measured via its adsorption quantity of adsorbate in these studies. There are no reports from the pore distribution, mineral phase transformation and other factors of adsorbent to study the adsorption properties of red mud. Moreover, the mechanism of pore-forming and activation also has not been well revealed.

In this work, microwave energy is used for preparing granular red mud (GRM) adsorbent made of red mud with different binders, such as starch, sodium silicate or cement, respectively. The main contents are as following: (1) Influence of operation parameters, such as binder type, binder addition ratio on the preparation effect of GRM in microwave heating and conventional heating process. (2) Investigation of the properties, such as the specific surface area, strength, pore structure and microstructure of GRM adsorbent under different conditions of the microwave heating. (3) Finding out the optimum experimental conditions that can be used for large quantity manufacture.

Experimental

Material

The fresh red mud, used as the principal raw materials, is obtained from an alumina plant, Guizhou province, China. Its water content is about 21.64% and its initial pH value is about 13. The main chemical compositions of the raw red mud based on the dry weight are presented in Table 1.

The composition of dry raw materials (wt.%).

| Composition | Fe | Al | SiO2 | TiO2 | CaO |

| Mass (wt.%) | 16.44 | 20.34 | 16.76 | 4.38 | 17.12 |

Mineralogical phases of raw red mud.

The XRD pattern is shown in Figure 1. The raw red mud is mainly composed of hematite (Fe2O3), calcite (CaCO3), lepidocrocite (Fe + 3O(OH)), xonotlite (Ca6Si6O17(OH)2), katoite (Ca3Al2(SiO4)(OH)8), with a minor percentage of Bayerite (Al (OH)3).

The high-quality Portland cement in this study is obtained from a cement plant in Kunming, China. Other binders, including starch, sodium silicate are all analytical grade.

Preparation of GRM in the small-scale experiment

The main purpose of small-scale experiment is to investigate the activation effect of the different binders on the preparation of GRM in a low-temperature heating process.

Each 200 g of fresh red mud are directly mixed with binder at different mass ratio of 2 ~ 8% and the new mixture is kneaded by hand to be the GRM adsorbent. Then the GRM is stored for conventional activation and microwave activation process.

Microwave activation process

100 g of granulated GRM is placed in a cylindrical ceramic crucible and put into a microwave oven for pore-forming. The heating temperature is set up to 150℃. Upon reaching 150℃, the sample is held at the same conditions for 10 min. Then GRM sample is taken and cooled to room temperature. The effects of parameters such as binder type (starch, sodium silicate and cement) and binder addition ratio (2%, 4%, 6%, 8%) on the property of activated GRM have been studied.

Conventional activation process

100 g of granulated GRM is placed in a cylindrical ceramic crucible and put into a muffle furnace for heating. A number of experimental parameters of conventional heating process are the same with microwave heating process in the small-scale experiment.

Preparation of GRM in the scale-up experiment

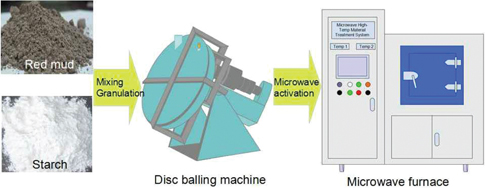

According to the results of BET surface area, strength and surface physical morphology in small-scale experiment, 6% starch as binder is used for large-scale preparation of the GRM – starch adsorbent material. The preparation procedures in the scale-up experiment are as illustrated in Figure 2.

Preparation procedure of GRM in the scale-up experiment.

In order to meet the requirements of the disc balling machine, after dried in an electric blast drying oven at 80℃ for 5 h, red mud is ground and sieved to particle size of about 100 mesh. The dry and sieved red mud powder is mixed with starch binder to produce GRM adsorbent by using a disc balling machine. The materials are appropriately sprayed water throughout granulating duration.

The obtained GRM is placed in a cylindrical ceramic crucible. Then GRM is put into a microwave heating apparatus for pore-forming. During the scale-up experiment, the heating rate and pore size distribution are studied by varying the microwave power from 2.0 to 3.0 kW, roasting temperature from 150 to 900℃, holding time from 5 to 30 min with 6% starch as a binder. The optimum conditions are obtained in this experiment.

Microwave heating system and characterization methods

Microwave furnace in this study is developed by Kunming University of Key Laboratory of Unconventional Metallurgy, Ministry of Education.

The strength of GRM is examined based on the efflorescence rate in aqueous solution. This method is reported by our formal papers [8, 24]. The BET surface area, average pore size distribution are analyzed using the surface area analyzer AUTOSORB-1 made by Quantachrome Instruments, USA. The microstructures are investigated using Scanning electron microscope (SEM, Philips XL20 ESEM-TMP).

Results and discussion

Small-scale experiment

The effect of binder on the properties of heated-GRM is carried out by putting GRM into microwave furnace and muffle furnace, respectively, and heated at 150℃ for 10 min. Then the samples are taken out and cooled to room temperature.

Efflorescence rate

The efflorescence rate of the samples is measured and shown in Table 2. It can be seen that the strength of GRM is significantly higher in microwave heating process compared to conventional heating process, especially when using starch as binder.

Efflorescence rate of different GRM samples with different binders (%).

| Adding ratio (%) | Starch | Sodium silicate | Cement | |||

| Conventional heating | Microwave heating | Conventional heating | Microwave heating | Conventional heating | Microwave heating | |

| 2 | 98.12 | 25.25 | 21.31 | 20.10 | 25.1 | 21.3 |

| 4 | 97.09 | 21.57 | 12.22 | 7.33 | 24.7 | 20.4 |

| 6 | 94.04 | 5.70 | 9.79 | 4.68 | 14.5 | 13.1 |

| 8 | 96.17 | 19.53 | 9.21 | 4.31 | 16.83 | 7.8 |

BET surface area

Effect of binder addition ratio

In order to evaluate the effect of binder addition ratio, the experiments are carried out by starch as binder. The results show that the BET surface area of the GRM samples prepared with 2%, 4%, 6% and 8% starch in microwave heating process are 13.22, 9.02, 35.06 and 3.54 m2/g, respectively. As can be seen, the BET surface area of GRM is affected by the binder addition ratio but it is not significantly increased with the increase of binder addition ratio.

Effect of binder type

The BET surface area of the GRM samples prepared with different addition rations of different binders is measured. The results show that the sequence of activation effect is starch > sodium silicate > cement. The activation effect of organic binder is better than the activation effect of inorganic binder, because the organic binder is easily decomposed and formed pores by microwave heating. The BET surface area of GRM samples which are prepared by the optimum adding ration of binders is shown in Table 3.

BET surface area of different GRM samples with different binders (m2/g).

| 6 wt.% starch | 6 wt.% sodium silicate | 2 wt.% cement | |||

| Conventional heating | Microwave heating | Conventional heating | Microwave heating | Conventional heating | Microwave heating |

| 19.17 | 35.06 | 14.07 | 31.02 | 17.63 | 20.18 |

Effect of microwave heating process

According to the results of the Tables 2 and 3, it can be seen that microwave heating has a better effect on pore-making of GRM as compared to conventional heating. The BET surface area of the GRM prepared with 6% sodium silicate increases from 14.07 m2/g to 31.02 m2/g and the strength increases by 5% in microwave heating system. A significant increase in the BET surface area of GRM prepared with 6% starch is observed with microwave heating as compared to conventional heating, from 19.17 m2/g to 35.06 m2/g. The strength significantly increases by 88.34%. Hence, the microwave heating process plays an important role in contributing to pore formation.

SEM micrographs of GRM sample prepared with 6% starch.

SEM micrographs of GRM sample prepared with 6% sodium silicate.

SEM analysis of microstructure

Figures 3 and 4 show the surface physical morphology of obtained GRM with 6% starch and 6% sodium silicate, respectively. A significant difference of the surface topography between GRM prepared with 6% starch and with 6% sodium silicate is observed. It can be seen that the surface of GRM prepared with 6% starch has large number of pores of irregular and heterogeneous morphology, which attests a significant development of pore structure. In addition, the diameter pore size of obtained GRM with 6% starch is relatively wide. All of the pores observed by SEM are mesopores and macropores, without micropore.

From the above results, it can be found that the activation effect of GRM prepared with 6% starch is the best.

Characterization of GRM in scale-up experiment

According to the optimum conditions of small-scale experiments, starch with addition ratio of 6% is used as binder in this scale-up experiment.

A series of experiments were conducted at the heating temperature in a range of 150 ~ 900℃, holding time with range of 5 ~ 30 min. Figure 5 shows the SEM images of the prepared GRM samples with different heating temperature, including 150℃, 600℃ and 900℃. It can be seen that with the increase of microwave heating temperature during the temperature from 150℃ to 600℃, the effect of pore-making by microwave also increases. When the temperature is higher than 600℃, the effect of pore-making decreases with increasing temperature. And the GRM is easily burned at temperature higher than 700℃. Moreover, prolonging holding time is helpful to improve the strength of the GRM.

SEM micrographs of the prepared GRM samples with different heating temperatures.

Due to the above results, the experimental conditions in this scale-up experiment are controlled at the heating temperature with range of 500 ~ 600℃, holding time with range of 20 ~ 30 min and microwave power with range of 2.0 ~ 3.0 kW. The experimental condition and the characterization of obtained GRM samples are listed in Table 4.

The experimental condition and the characterization of different GRM samples.

| Sample definition | Experimental condition | Characterization of GRM | |||||

| Microwave power (kW) | Heating temperature (℃) | Holding time(min) | Efflorescence rate (%) | BET surface area (m2/g) | Total pore volume (cm3/g) | Average pore diameter/A0 | |

| GRM-1 | 2.0 | 600 | 20 | 5.2 | 17.06 | 0.0340 | 31.693 |

| GRM-2 | 2.6 | 600 | 30 | 7.9 | 13.62 | 0.0333 | 30.600 |

| GRM-3 | 3.0 | 600 | 20 | 6.5 | 11.41 | 0.0316 | 27.691 |

| GRM-4 | 2.6 | 500 | 20 | 16.22 | 13.89 | 0.0525 | 33.152 |

| GRM-5 | 2.6 | 500 | 30 | 9.6 | 15.58 | 0.0337 | 31.693 |

Pore structure

Pore size and distribution are the important parameters of porous materials. According to the classification of IUPAC-pore dimensions, the pores of adsorbents are grouped into micropore (d < 2 nm), mesopore (d = 2 ~ 50 nm) and macropore (d > 50 nm) [25].

The results of GRM pore size distribution of the samples are shown in Figure 6. The results show that, the GRM samples under different conditions have nearly similar curve shape with pore size distribution curve. Although without micropore, the GRM adsorbents contain well-developed pore structure in both regions of mesopore and macropore. A few peaks are detected, with the sharpest peak occurred at pore width between 2.5 and 35 nm, with an average pore size of 27.691 ~ 33.152 A0 shows that a majority of the pores fall into the range of mesopore. The mesopores are mainly distributed in the regions of 2.5 ~ 10 nm and 25 ~ 35 nm. We observed that both of outrageous microwave power, excessive temperature and lack of holding time cause a decrease in the peak height and will not be benefit to pore-forming process.

Pore size distribution of different GRM samples.

Efflorescence rate and BET surface area

The actual photographs of GRM heated by microwave under different conditions are shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that the outrageous microwave power or excessive temperature make material temperature is risen quickly and results the material is heated unevenly. Those small spherical particles of the GRM around thermocouple are bonded together to form objects of larger spherical shapes. Conversely, when the microwave power is low, the material temperature is risen slowly resulting in the waste of energy. Therefore, adjusting the microwave power and the heating temperature, and prolonging the holding time improve the strength and the BET surface area of GRM sample.

The actual photographs of GRM samples.

It can be seen from Table 4, the BET surface area and the strength of the sample GRM-1 and of the sample GRM-5 are ideal. However, compared with GRM-1, the heating temperature of GRM-5 sample is lower. So GRM-5 sample has shorter heating time and less energy consumption. When industrial cost is considered, the experimental condition of the GRM-5 sample is more favorable.

According to the above results, the experimental conditions of the GRM-5 sample prepared are regarded as the optimum conditions in this scale-up experiment. The optimum conditions include 6% starch as binder, microwave heating temperature of 500℃, microwave power of 2.6 kW, holding time of 30 min. The BET surface area, pore volume and efflorescence rate of the GRM adsorbent prepared under the optimum conditions are 15.58 m2/g, 0.0337 cm3/g and 9.6%, respectively. Therefore, the GRM adsorbent prepared from red mud and starch after microwave roasting has potentials to be a suitable adsorbent with large specific surface. And this process can be used for large-scale preparation.

The characterization of the GRM produced by the optimum conditions

Figure 8 presents the XRD pattern of the GRM-5 sample which produced by the optimum conditions. As can be seen, the main peak of bayerite has been totally eliminated, while new phases such as α-Al2O3 and Ca4Al4Si4O6(OH)24·3H2O have been formed.

XRD pattern of GRM-5 sample.

Conclusions

Among three kinds of binder, the sequence of activation effect is starch > sodium silicate > cement. The GRM adsorbent produced by fresh red mud directly mixed with 6% starch, which has the best activation effect with the high strength and the BET surface area of 35.06 m2/g.

In comparison to conventional heating, the microwave roasting has a good effect on pore-making of GRM, especially when using organic binder.

Adjusting the microwave power and the heating temperature, and prolonging the holding time, which is benefit for heating evenly and improving the strength of GRM sample.

At the optimum condition (microwave heating temperature: 500℃, microwave power: 2.6 kW, holding time: 30 min), the BET surface area, pore volume and average pore diameter of the GRM adsorbent which produced from dry powder red mud and 6% starch are estimated to be 15.58 m2/g, 0.0337 cm3/g and 3.1693 A0, respectively.

Funding statement: Funding: Project (No. 51264022) supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China and Applied Basic Research Program of Yunnan Province (KKSY 201232038).

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 51264022) and Applied Basic Research Program of Yunnan Province (KKSY 201232038).

References

[1] M.Samouhos, M.Taxiarchou, P.E.Tsakiridis and K.Potiriadis, J. Hazard. Mater., 254–255 (2013) 193–205.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.03.059Search in Google Scholar

[2] X.J.Li and J.L.Zhao, Light Metals, 9 (2005) 16–19.Search in Google Scholar

[3] W.C.Liu, J.K.Yang and B.Xiao, Int. J. Miner. Process., 93 (2009) 220–231.10.1016/j.minpro.2009.08.005Search in Google Scholar

[4] P.E.Tsakiridis, S.Agatzini-Leonardou and P.Oustadakis, J. Hazard. Mater., 116 (2004) 103–110.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.08.002Search in Google Scholar

[5] Z.H.Pan, L.Cheng, Y.N.Lu and N.R.Yang, Cem. Concr. Res., 32 (2002) 357–362.10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00683-4Search in Google Scholar

[6] Y.Cengeloglu, E.Kir, M.Ersoz, T.Buyukerkek and S.Gezgin, Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects, 223 (2003) 95–101.10.1016/S0927-7757(03)00198-5Search in Google Scholar

[7] P.K.N.Raghavan, N.K.Kshatriya and K.Wawrynink, Light Metals, TMS, San Diego (2011) 103–106.10.1002/9781118061992.ch18Search in Google Scholar

[8] S.H.Ju, S.D.Lu, J.H.Peng, L.B.Zhang, C.Srinivasakannan, S.H.Guo and W.Li, Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China, 22 (2012) 3140–3146.10.1016/S1003-6326(12)61766-XSearch in Google Scholar

[9] S.W.Zhang, C.J.Liu, Z.K.Luan, X.J.Peng, H.J.Ren and J.Wang, J. Hazard. Mater., 152 (2008a) 486–492.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Q.Wang, Z.K.Luan, N.Wei, J.Li and C.X.Liu, J. Hazard. Mater., 170 (2009) 690–698.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] S.B.Wang, Y.Boyjoo, A.Choueib and Z.H.Zhu, Water Res., 39 (2005) 129–138.10.1016/j.watres.2004.09.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] A.Tor and Y.Cengeloglu, J. Hazard. Mater., 138 (2006) 409–415.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.04.063Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] W.T.Liang, S.J.Couperthwaite, G.Kaur, C.Yan, D.W.Johnstone and G.J.Millar, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 423 (2014) 158–165.10.1016/j.jcis.2014.02.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] I.Smiciklas, S.Smiljanic, A.Peric-Grujic, M.Sljivic-Ivanovic, M.Mitric and D.Antonovic, Chem. Eng. J., 242 (2014) 27–35.Search in Google Scholar

[15] H.Nadaroglu and E.Kalkan, Int. J. Phys. Sci., 7 (2012) 1386–1394.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Q.Y.Yue, Y.Q.Zhao, Q.Li, W.H.Li, B.Y.Gao, S.X.Han, Y.F.Qi and H.Yu, J. Hazard. Mater., 176 (2010) 741–748.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.11.098Search in Google Scholar

[17] C.L.Zhu, Z.K.Luan, Y.Q.Wang and X.D.Shan, Sep. Purif. Technol., 57 (2007) 161–169.10.1016/j.seppur.2007.03.013Search in Google Scholar

[18] Y.Q.Zhao, Q.Y.Yue, Q.Li, B.Y.Gao, S.X.Han and H.Yu, J. Hazard. Mater., 182 (2010) 309–316.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.06.031Search in Google Scholar

[19] R.Apak, E.Tutem, M.Hugul and J.Hizal, Water Res., 32 (1998) 430–440.10.1016/S0043-1354(97)00204-2Search in Google Scholar

[20] C.J.Liu, Y.Z.Li, Z.K.Luan, Z.Y.Chen, Z.G.Zhang and Z.P.Jia, J. Environ. Sci., 19 (2007) 1166–1170.10.1016/S1001-0742(07)60190-9Search in Google Scholar

[21] Q.H.Jin, S.S.Dai and K.M.Huang, Microwave chemistry, Beijing, Science Press, (1999), pp. 1 (in Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[22] X.J.Li and J.L.Zhao, Light Metals, 9 (2005) 16–19. (in Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[23] G.Cheng, D.S.Xiaand and Q. F.Zeng, Ind. Water and Wastewater, 4 (2008) 43–46. (in Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[24] T.Q.X.Le, H.R.Wang, S.H.Ju, J.H.Peng, L.X.Zhou and L.Q.Dai, Desalin. Water Treat., (2014). doi: 10.1080/19443994.2014.970578.Search in Google Scholar

[25] K.Y.Foo and B.H.Hameed, Bioresource Technol., 111 (2012) 425–432.10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.141Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2016 by De Gruyter

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Effects of Cations on Corrosion of Inconel 625 in Molten Chloride Salts

- Thermodynamic Analysis on the Minimum of Oxygen Content in the Deoxidation Equilibrium Curve in Liquid Iron

- Air Oxidation Behavior of Two Ti-Base Alloys Synthesized by HIP

- Generation of Constant Life Diagram under Elevated Temperature Ratcheting of 316LN Stainless Steel

- Effect of c-BN Size and Content on the Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of c-BN Composites Bonded with Ti-Al-C System Multiphase Products

- Effect of Welding Speeds on Mechanical Properties of Level Compensation Friction Stir Welded 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloy

- Simulation of Thermo-viscoplastic Behaviors for AISI 4140 Steel

- Transition Metal Nitrides: A First Principles Study

- The Constitutive Relationship and Processing Map of Hot Deformation in A100 steel

- Preparation of Granular Red Mud Adsorbent using Different Binders by Microwave Pore – Making and Activation Method

- On the Structure and Some Properties of LaCo Co-substituted NiZn Ferrites Prepared Using the Standard Ceramic Technique

- Effect of MgO and MnO on Phosphorus Utilization in P-Bearing Steelmaking Slag

- Dependence of Temperature and Slag Composition on Dephosphorization at the First Deslagging in BOF Steelmaking Process

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Effects of Cations on Corrosion of Inconel 625 in Molten Chloride Salts

- Thermodynamic Analysis on the Minimum of Oxygen Content in the Deoxidation Equilibrium Curve in Liquid Iron

- Air Oxidation Behavior of Two Ti-Base Alloys Synthesized by HIP

- Generation of Constant Life Diagram under Elevated Temperature Ratcheting of 316LN Stainless Steel

- Effect of c-BN Size and Content on the Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of c-BN Composites Bonded with Ti-Al-C System Multiphase Products

- Effect of Welding Speeds on Mechanical Properties of Level Compensation Friction Stir Welded 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloy

- Simulation of Thermo-viscoplastic Behaviors for AISI 4140 Steel

- Transition Metal Nitrides: A First Principles Study

- The Constitutive Relationship and Processing Map of Hot Deformation in A100 steel

- Preparation of Granular Red Mud Adsorbent using Different Binders by Microwave Pore – Making and Activation Method

- On the Structure and Some Properties of LaCo Co-substituted NiZn Ferrites Prepared Using the Standard Ceramic Technique

- Effect of MgO and MnO on Phosphorus Utilization in P-Bearing Steelmaking Slag

- Dependence of Temperature and Slag Composition on Dephosphorization at the First Deslagging in BOF Steelmaking Process