Abstract

Objectives

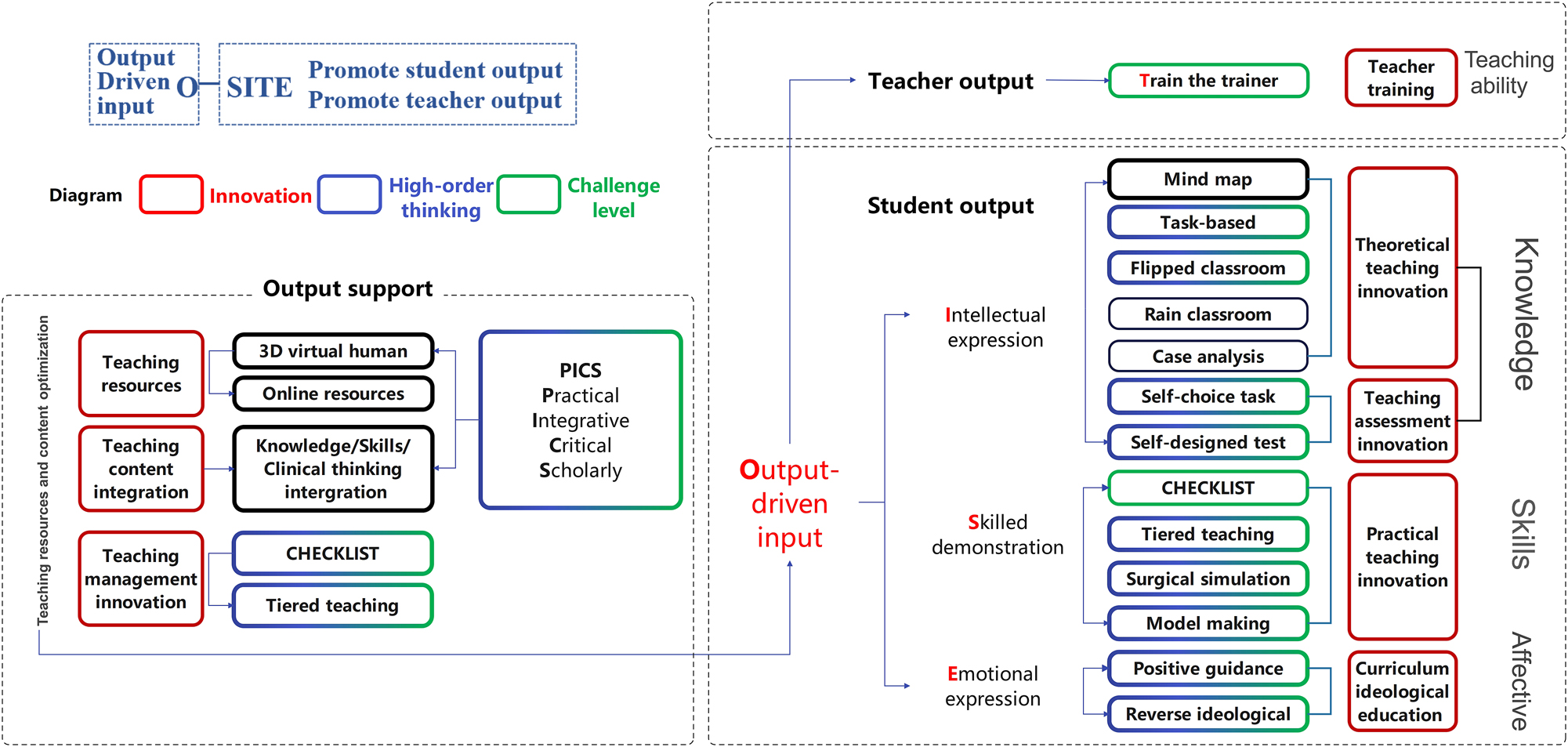

Surgical education in undergraduate medical curricula often faces fragmented content delivery, insufficient student engagement, and uneven teaching competencies. To address these issues, we developed and implemented the O-SITE model (O emphasizes the Output-driven input concept; SITE fosters student output and improves faculty teaching through Skilled demonstration, Intellectual expression, Train-the-trainer model, and Emotional expression).

Methods

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach to evaluate the effectiveness of the O-SITE model. A cohort of 119 clinical medical students (O-SITE group) received surgical education based on the O-SITE framework, and 108 students served as historical controls under traditional teaching. Quantitative outcomes included formative and summative assessment scores and the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) questionnaire. Qualitative insights were derived from semi-structured interviews with 12 students and analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

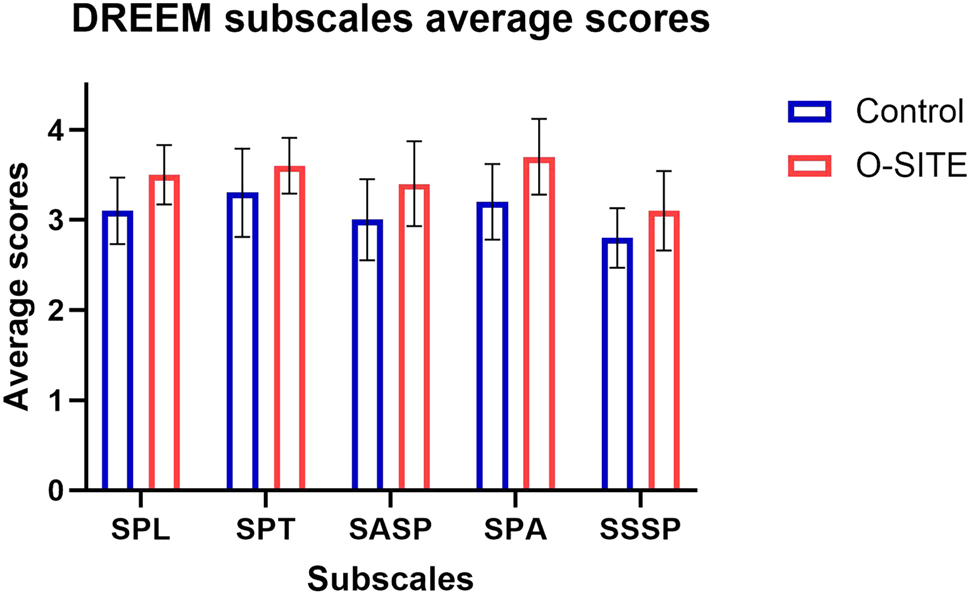

Compared to controls, the O-SITE group demonstrated significantly higher formative ([84.5 ± 5.2] vs. [81.2 ± 5.5]) and summative ([81.3 ± 5.7] vs. [80.1 ± 5.6]) assessment scores (both p<0.001). DREEM scores in all five dimensions, including perceptions of learning, teachers, academic self-perception, atmosphere, and social self-perception, significantly improved in the O-SITE group (all p<0.001). Thematic analysis identified three key outcomes: increased learning initiative, enhanced clinical reasoning and skills, and improved empathy and professional identity.

Conclusions

The O-SITE model effectively promotes active learning and clinical competency through structured multidimensional student output. By integrating learner-centered design with faculty development, this approach addresses the core deficiencies in traditional surgical education and provides a scalable framework for competency-based medical training.

Introduction

Surgery is a core course in undergraduate clinical medicine curriculum, comprising 120 class hours and 6 credits. It emphasizes theory–practice integration and fusion of basic and clinical knowledge. The course covers diagnosis, treatment principles, and basic surgical skills for common surgical diseases, cultivating students’ clinical reasoning, fundamental operative skills, and preliminary clinical decision-making [1]. At the First Clinical Medical College of Gansu University of Chinese Medicine, all surgical teaching is delivered by dual-qualified clinical physicians with both medical practitioner and teaching certifications. Over the past decade, the course has undergone continuous reform and innovation and was recognized as a provincial first-class course in 2021.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain for implementing surgical education. Fragmented teaching content and little systematic knowledge hinder building a coherent knowledge framework and sound clinical thinking. Limited clinical teaching resources and low student engagement prevent the effective integration of theory and practice. Additionally, teaching competencies remain uneven, curriculum design lacks interdisciplinary integration, and students’ development of humanistic care and professional identity receives insufficient attention. These issues significantly constrain surgical education quality and cultivation of competency-based medical professionals.

To address these challenges – students’ low learning initiative, the disconnect between knowledge and skills, and disparities in teaching abilities – this study, guided by competency-based education principles [2], introduces and implements the O-SITE (O emphasizes the Output-driven input concept; SITE fosters student output and improves faculty teaching through Skilled demonstration, Intellectual expression, Train-the-trainer model, and Emotional expression) teaching model for surgical education. This model is grounded in the core concept of “output-driven input” (ODI,O), with the SITE framework facilitating information output across four dimensions: intellectual expression, skilled demonstration, emotional expression, and train-the-trainer (TTT) for faculty development. These dimensions correspond to the educational goals of knowledge acquisition, skill development, competency enhancement, and teaching capacity-building. Through innovative instructional design and resource development, the model supports active student output and fosters autonomous learning, clinical reasoning, technical proficiency, and humanistic values.

Using a systematic evaluation approach combining quantitative analysis and qualitative interviews, this study comprehensively assesses the effectiveness of the O-SITE model to provide scientific evidence and practical insights for medical education reform and to develop competency-based healthcare professionals.

Methods

Educational objectives

The Surgery course at The First School of Clinical Medical, Gansu University of Chinese Medicine aims to enhance competency for positions in primary healthcare settings with three core dimensions – knowledge, skills, and affect – with the following educational objectives:

Knowledge objectives

Describe fundamental surgical theories and commonly used terminology;

Identify pathogenesis and clinical features of common surgical diseases encountered in primary care;

Summarize diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for common conditions in various surgical subspecialties;

Understand and outline commonly used surgical techniques in primary care and their developmental trends.

Skills objectives

Determine surgical indications and contraindications for common surgical diseases;

Analyze clinical surgical cases and reason through decision-making;

Perform basic surgical procedures relevant to primary care (e.g. suturing, dressing changes, and drainage);

Document case records and deliver preliminary case presentations;

Collaborate effectively in simple surgical team settings, demonstrating communication and teamwork.

Affective objectives

Demonstrate empathy and a caring attitude toward patients;

Uphold patient-centered medical humanism in clinical practice;

Articulate a sense of responsibility to serve grassroots communities and safeguard public health;

Exhibit responsiveness to public health emergencies and a strong sense of medical mission.

Enhancing students’ knowledge, skills, and affective output

Promoting knowledge output

Mind mapping

To enhance understanding of common and frequently encountered surgical conditions in primary care, students were assigned mind-mapping tasks [3]. Before class, students previewed the relevant content and created mind maps covering etiology, key diagnostic points, and treatment principles. This approach encourages active knowledge organization and internalization while improving comprehension and transfer of surgical anatomy and procedural essentials.

Flipped classroom

In a two-session oncology module, over 10 student-selected topics were designed, including “cancer and lifestyle,” “cancer and exercise,” and “cancer and environmental pollution.” Students formed self-selected groups, chose topics independently, conducted literature searches, and prepared presentations. Each group selected one representative to deliver a 7-min presentation; then, a randomly selected second member provided a 3-min supplementary speech, ensuring full participation. After each presentation, a 3-min class discussion was conducted. All students participated in scoring, and groups shared the final grade for formative assessment. This approach enabled the effective implementation of the flipped classroom model in large class settings, fostering collaboration, individual accountability, and active engagement.

Self-selected assignments

For formative assessment, a self-selected assignment module was introduced, allowing students to choose any form of expression, such as drawings, videos, essays, models, or reflective writing, to demonstrate understanding and internalization of core surgical knowledge. This method emphasized personalized expression and creative output, encouraging students to reinterpret and rephrase professional knowledge, thereby enhancing learning initiative and depth.

Student-generated exam questions

For summative assessment, a pilot “student-generated question” approach was implemented. In groups of 6–8, students were instructed to design a complete examination paper based on pre-specified formats and content coverage with answer keys, rationales, and confidentiality agreements. The teaching team selected, integrated, and refined student-generated questions to create the final examination. This process embodied the ODI philosophy by guiding students to engage with course content from an examiner’s perspective, enhancing knowledge integration and application skills.

Promoting skills output

Checklist-based teaching

Clinical skills training employed a checklist-based teaching model [4]. For wound dressing, students independently designed a step-by-step checklist, which was reviewed and approved by faculty. Key knowledge points were highlighted. Students were expected to consult relevant resources and master theoretical knowledge in advance. Before hands-on practice, faculty conducted on-site questioning to verify students’ knowledge readiness; then, students performed the procedure following the checklist. This approach effectively enhanced student engagement, ensured teaching quality and procedural safety, and promoted skill acquisition and knowledge integration.

Model construction

For commonly encountered surgical conditions in primary care, students worked in groups to design and build teaching models based on relevant surgical anatomy and procedures. The models were presented and demonstrated in class. This process deepened the students’ understanding of surgical concepts and operative techniques.

Video demonstration

A “video demonstration” module required students to video-record themselves performing and explaining basic surgical skills (e.g. knot-tying). Faculty assessed procedural accuracy and explanation quality, providing feedback accordingly. This method was retained from online teaching practices during the COVID-19 pandemic because of its effectiveness in reinforcing technical mastery and knowledge internalization. The “practice-while-explaining” format not only assessed operational skills but also embodied the ODI philosophy, enhancing students’ communication abilities and procedural clarity.

Promoting affective output

To cultivate affective output, we proposed “reverse ideological and political education,” moving away from the traditional teacher-centered, passive value inculcation model. Instead, we emphasized students’ active, inside-out expressions of values and emotions.

Several clinically relevant, conflict-driven case scenarios, including complications and emergencies, were designed. Students were divided into groups to role-play both healthcare providers and patients, engaging in simulated clinical encounters. Through role immersion, adversarial dialogue, and collaborative decision-making, students experienced the essence of “patient-centered care” and were encouraged to express their understanding and reflections on professional responsibility, empathy, and humanistic values. This approach facilitated internalizing and expressing affective values, truly embodying the ODI teaching philosophy.

Promoting faculty output to enhance teaching competence

To enhance the teaching capabilities of dual-qualified clinical faculty and implement the ODI philosophy, we adopted a sequential TTT model [5]. Faculty members underwent systematic training across four structured modules: educational regulations, teaching techniques, instructional design, and clinical mentoring. Subsequently, they transitioned to instructors for the next cycle of faculty training while engaging in real-time teaching practice with students. Faculty received continuous multi-dimensional feedback throughout from students, peer teachers, and educational supervisors. This iterative approach accelerated internalization of teaching concepts and methods, facilitated transformation from “learning to teach” to “teaching to master,” and effectively promoted homogenization and overall improvement of teaching skills.

Developing educational resources to support student-driven output

Instructional content integration

To address the challenges of large dual-qualified teaching teams, fragmented content, and inconsistent instructional styles, the curriculum team proposed and implemented the PICS (stands for Practical, Integrative, Critical, and Scholarly) content-integration framework. This framework optimizes surgical education content in four dimensions to unify instructional approaches, standardize teaching logic, and improve educational quality:

Practical: Emphasizes alignment with real-world clinical practice by incorporating multimodal resources such as images, videos, and physical specimens to help students build clinical perceptions and strengthen practical relevance;

Integrative: Promotes knowledge integration across systems and modules, particularly bridging basic science with clinical applications and fostering interdisciplinary coherence to help students construct a comprehensive knowledge framework;

Critical: Highlights surgery’s dual nature by encouraging students to move beyond technical mastery (“how to”) and focus on clinical judgment and reflection (“whether to” and “why to”);

Scholarly: Advocates a research-oriented mindset by integrating the latest disciplinary advances into teaching content, guiding students to approach clinical problems through academic enquiry, and cultivating lifelong-learning competencies.

Building online teaching resources

To meet diverse learning needs and enhance flexibility in pre-class preparation and post-class review, three categories of online teaching resources were developed and fully integrated into the curriculum, providing robust support for output-oriented learning.

First, a self-developed video library covering aseptic techniques, basic surgical skills, and common procedures was created based on students’ cognitive characteristics. This resource enables visualized skill learning outside clinical settings and is an essential, high-usage component.

Second, to assist students who might struggle with new teaching formats, traditional lecture-style resources were constructed, including synchronized audio, text, and PowerPoint materials. These structured and accessible resources allow students to review and fill knowledge gaps at any time.

Third, digital tools, real-time classroom audio, and slide content were leveraged to seamlessly integrate online and offline teaching, supporting personalized post-class review of key and challenging topics and enhancing learning continuity and accessibility (Figure 1).

The O-SITE model for surgical education. O emphasizes the output-driven input concept; SITE fosters student output and improves faculty teaching through skilled demonstration, intellectual expression, train-the-trainer model, and emotional expression.

Assessment and evaluation methods

Guided by the ODI philosophy, this course established a multidimensional evaluation system integrating formative and summative assessments and emphasizing continuous assessment and competency development. Formative assessment accounts for 60 % of the total grades and includes group performance, humanistic competencies, mind maps, clinical skills, and self-selected assignments. It focuses on student performance in teamwork, self-directed learning, clinical practice, and personalized development. Summative assessment constitutes 40 % of the total grade and evaluates the mastery of core knowledge, comprehensive analysis, and innovative thinking through a final examination or comprehensive assessment aimed at enhancing students’ clinical application abilities and lifelong learning skills.

Evaluation of teaching effectiveness

Both quantitative and qualitative methods were employed to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the O-SITE teaching model. One hundred nineteen undergraduate students majoring in five-year clinical medicine programs (Class of 2019) received surgical education following the O-SITE model. A control group of 108 students from the Class of 2018 underwent traditional teaching prior to the comprehensive reform. Both groups received the same course content, class hours, and assessment standards and were taught by dual-qualified clinical faculty with comparable qualifications, ensuring baseline consistency in teaching context.

The course adopted a “teaching-assessment separation” policy, with instructors not involved in summative assessment scoring. Summative assessments were constructed using student-generated questions, with faculty selection and integration of exam items. All exam content strictly adhered to a standardized syllabus and learning objectives, ensuring consistency in exam scope, question formats, and evaluation criteria across groups.

Quantitative evaluation utilized the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) questionnaire to assess students’ learning experiences. Feedback was collected electronically within two weeks of course completion. The DREEM, widely used to evaluate students’ perceptions of the educational environment, measures students’ perceptions of learning, teachers, and atmosphere; academic self-perception; and social self-perception with 50 sub-items rated on a five-point Likert scale (0–4) [6].

For qualitative evaluation, purposive sampling was used to select 12 representative students from the O-SITE group for one-on-one semi-structured interviews. The interviews explored overall perceptions of the teaching model, changes in learning motivation, improvements in clinical skills, enhancement of humanistic competencies, and suggestions for improvement. Each interview lasted approximately 20–30 min, and audio recordings were transcribed into text. Thematic analysis was conducted using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework to extract key themes and insights [7]. For quantitative data, before applying parametric tests, normality checks were performed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the data met normality assumptions.

Results

Course assessment outcomes

Both groups successfully completed the course assessments with 108 students in the control group and 119 in the O-SITE group. The O-SITE group scored significantly higher in formative assessment (84.5 ± 5.2), summative assessment (81.3 ± 5.7), and overall performance (83.1 ± 4.8) compared to the control group ([81.2 ± 5.5], [80.1 ± 5.6], [81.0 ± 5.1]) (all p<0.001).

DREEM scale results

Baseline characteristics showed no significant between-group differences in gender (control: 52 male and 56 female; O-SITE: 58 male and 61 female, p=0.92), age ([21.3 ± 0.9] vs. [21.2 ± 0.8] years, p=0.45), or grade point average ([3.45 ± 0.22] vs. [3.47 ± 0.25], p=0.38), confirming good comparability.

In the DREEM assessment, 119 questionnaires were distributed to the O-SITE group with 107 valid responses (response rate: 90.0 %); 108 were distributed to the control group with 92 valid responses (response rate: 85.2 %). The O-SITE group scored significantly higher across all five DREEM dimensions: students’ perceptions of learning (SPL: 3.5 vs. 3.1), perceptions of teachers (SPT: 3.6 vs. 3.3), academic self-perceptions (SASP: 3.4 vs. 3.0), perceptions of atmosphere (SPA: 3.7 vs. 3.2), and social self-perceptions (SSSP: 3.1 vs. 2.8) (all p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Quantitative evaluation of the O-SITE model and the conventional teaching model using the DREEM scale. For O-SITE, O emphasizes the output-driven input concept; SITE fosters student output and improves faculty teaching through skilled demonstration, intellectual expression, train-the-trainer model, and emotional expression. DREEM, dundee ready education environment measure; SPL, students’ perceptions of learning; SPT, students’ perceptions of teachers; SASP, students’ academic self-perceptions; SPA, students’ perceptions of atmosphere; SSSP, students’ social self-perceptions.

Qualitative analysis results

Twelve semi-structured interviews were conducted, with an accumulated interview time of approximately 250 min, generating over 60,000 words of valid transcripts. Thematic analysis identified three major themes.

Theme 1: enhanced learning initiative and engagement

Most students reported that class presentations, mind mapping, and group discussions effectively stimulated their motivation for active learning and increased classroom engagement. For example, one student stated, “To give a presentation, I had to study in advance. This made me learn more proactively” (Student 3).

Theme 2: improved clinical thinking and skills

Students generally agreed that case analysis and simulation exercises enhanced their ability to apply theory to practice and fostered clinical reasoning development. As one student noted, “The case analysis helped me start thinking like a doctor” (Student 7).

Theme 3: strengthened humanistic qualities and reflective capacity

Some students reported that role-playing and group collaboration improved their communication skills, empathy, and sense of professional identity. One student shared, “Experiencing things from the patient’s perspective helped me better understand what empathy really means” (Student 10).

Discussion

This study systematically evaluated the implementation and effectiveness of the O-SITE teaching model for Surgery, which is centered on promoting information output, using a combination of quantitative analysis and qualitative interviews. The quantitative results demonstrated that students who received O-SITE-based instruction achieved significantly higher scores in formative assessment, summative assessment, and overall performance than those in the traditional teaching group. Additionally, analysis of the DREEM scale revealed that the O-SITE group scored significantly higher across all five dimensions. The qualitative findings further validated the quantitative data, with students consistently reporting that the O-SITE model enhanced their learning initiative and engagement, improved clinical reasoning and skills, and fostered greater humanistic awareness and professional identity. These results provide preliminary evidence of the practical value of the O-SITE model in advancing medical education reform.

The theoretical foundation of the O-SITE model is the Feynman Technique, which emphasizes that actively outputting information facilitates deeper understanding and knowledge internalization [8]. Unlike traditional medical education, which often overemphasizes passive information input, the O-SITE model shifts focus toward the quality and depth of student information output from the perspective of knowledge transmission. When students are able to express information clearly and logically across cognitive, skill-based, and affective domains, it reflects that they have internalized and integrated this knowledge into their existing cognitive frameworks, thereby constructing a solid, transferable knowledge system [9]. Furthermore, the model introduces an innovative focus on faculty development by applying an output-driven sequential TTT approach [5], which fosters comprehensive improvements in teaching design, instructional skills, and clinical mentorship among dual-qualified faculty. This creates a virtuous cycle of mutual promotion and collaborative growth between students and teachers.

The findings further revealed that various dimensions of information output under the O-SITE model positively influenced student performance, learning experience, clinical reasoning, and humanistic development. In terms of learning outcomes, students in the O-SITE group consistently achieved significantly higher scores across all five dimensions of the DREEM scale than those in the control group (all p<0.0001). Notably, improvements in SPA and SPL were particularly pronounced, indicating that the model’s use of flipped classrooms, video demonstrations, and checklist-based learning effectively enhanced students’ perceptions of the learning environment, increased engagement, and stimulated active learning. These findings align with existing research emphasizing the critical role of classroom atmosphere in fostering learning motivation and improving learning outcomes [10].

Additionally, the O-SITE group performed exceptionally well in SASP and SSSP, suggesting that the output-driven teaching model not only strengthened students’ mastery of professional knowledge and clinical thinking but also promoted humanistic competencies and social responsibility. This aligns with the current direction of medical education, which emphasises integrating clinical competence with humanistic care [11]. In contrast, although the control group maintained moderately high scores across dimensions, clear deficiencies were observed in learning initiative, classroom atmosphere, and humanistic awareness, highlighting the limitations of traditional teaching models in motivating students and enhancing comprehensive competencies [12].

Qualitative interviews further validated the conclusions drawn from the quantitative data. Student feedback indicated that knowledge output activities such as mind mapping, student-generated examinations, and self-selected assignments significantly enhanced the systematization and transferability of knowledge structures. Task-oriented output forms, including clinical case analysis and surgical model construction, enabled students to develop a deeper understanding of surgical anatomy and key procedural concepts, thereby substantially improving clinical decision-making and logical reasoning skills. Moreover, affective output activities such as reverse role-play and values-based discussions effectively strengthened students’ perceptions of medical humanism and professional identity, deepening their sense of medical mission and social responsibility. Overall, the O-SITE teaching model, through a systematic and multidimensional approach to information output, effectively promoted integrated development of knowledge internalization, skill acquisition, clinical reasoning, and humanistic competence.

A growing body of research in medical education supports student-centered, output-driven teaching models such as the Feynman Technique and flipped classrooms [13], which emphasize active student expression and practice to foster knowledge internalization and competency development. Compared to traditional passive learning approaches, these models have been shown to significantly improve students’ learning motivation, engagement, and problem-solving abilities [14] – findings consistent with the advantages of the O-SITE model observed in this study, particularly in enhancing learning initiative, clinical thinking, and skills acquisition. Each O-SITE dimension not only represents an output form but also embodies the ODI principle by requiring learners or faculty to internalize knowledge, skills, values, and teaching methods before expression. However, most existing output-oriented models focus on a single dimension (e.g. knowledge presentation or skill demonstration) without addressing the broader educational landscape [15], 16]. In contrast, the O-SITE model integrates four complementary dimensions – intellectual expression, skilled demonstration, emotional expression, and faculty development – through TTT, thus systematically operationalizing the ODI principle. This integration achieves innovation not only in instructional design (e.g. checklist-based learning, student-generated assessments, video demonstrations) but also in faculty training (through the TTT model). Unlike most existing output-driven models that focus on a single dimension, O-SITE simultaneously enhances students’ knowledge, skills, and affective competencies while systematically improving faculty teaching capacity, thereby creating a reciprocal cycle of student–teacher advancement. This comprehensive and scalable framework demonstrates greater innovation and broader applicability than current models reported in the literature.

Some potential challenges exist in implementing the O-SITE model. Both the iterative TTT approach and student output activities require considerable time investment. This workload can be mitigated by gradually introducing output-driven activities, starting with common surgical conditions in general surgery and then expanding to broader course content. Regarding resource requirements, although self-developed materials are ideal, abundant high-quality online educational resources are readily available to support both teachers and students, providing feasible alternatives in resource-limited settings. Finally, some students initially struggled to adapt to the shift from passive learning to output-driven formats. To ease this transition, we supplemented the O-SITE curriculum with traditional lecture-style online resources, which helped students adjust quickly and gradually embrace the new approach.

This study had several limitations. First, as a single-center study with a relatively limited sample size, the generalizability and external validity may have been constrained. Second, although a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative analysis with qualitative interviews was employed, the small sample size and inherent subjectivity of the qualitative interviews may have introduced potential bias. Third, the observation period was relatively short, and no long-term follow-up was conducted to assess the sustained impact of the O-SITE model on teaching outcomes. Future research should involve multicenter studies with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods to further validate the effectiveness and scalability of the model.

Conclusions

This study developed and implemented the O-SITE teaching model for Surgery, which is grounded in the core ODI principle. By systematically integrating information output across four dimensions – knowledge, skills, affective development, and faculty growth – the model significantly enhanced students’ active learning ability, clinical reasoning, procedural skills, and humanistic competence, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional surgical education. The O-SITE model not only improved students’ overall learning experience and clinical competency development but also innovatively facilitated the continuous advancement of dual-qualified teaching faculty. It demonstrates substantial value for educational reform and holds promise for broader application and dissemination.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Junliang Li, Haibang Pan, Jianfeng Yi and Hui Cai authored this manuscript. The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: No AI or machine-learning tools were used.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Gansu Province “14th Five-Year Plan” Educational Science Research Project (GS[2021]GHB1859), the Teaching Research and Reform Project of Gansu University of Chinese Medicine (2021-KCSZ-009, ZHXM-202207), and Graduate Education and Teaching Reform Project of Gansu University of Chinese Medicine (308107030103).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Nguyen, S, Johnston, T, McCrary, HC, Berg, E, Mitchell, A, Patel, R, et al.. Medical student attitudes and actions that encourage teaching on surgery clerkships. Am J Surg 2021;222:1066–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.03.067.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Alharbi, NS. Evaluating competency-based medical education: a systematized review of current practices. BMC Med Educ 2024;24:612. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05609-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. He, J, Wu, B, Zhong, H, Zhang, Y, Li, F, Chen, L, et al.. Implementing mind mapping in small-group learning to promote student engagement in the medical diagnostic curriculum: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ 2024;24:336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05318-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Bhat, S. Checklist-based training for essential clinical skills in 3 term MBBS students. Int J Acad Med 2021;7:150–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijam.ijam_141_20.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Nexø, MA, Kingod, NR, Eshøj, SH, Kjærulff, EM, Nørgaard, O, Andersen, TH. The impact of train-the-trainer programs on the continued professional development of nurses: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ 2024;24:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04998-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Awawdeh, M, Alosail, LA, Alqahtani, M, Almotairi, A, Almikhem, RN, Alahmadi, RA, et al.. Students’ perception of the educational environment at King Saud Bin abdulaziz university for health sciences using DREEM tool. BMC Med Educ 2024;24:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-05004-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Braun, V, Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counsell Psychother Res J 2021;21:37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Reyes, EP, Blanco, RMFL, Doroon, DRL, Limana, JLB, Torcende, AMA. Feynman technique as a heutagogical learning strategy for independent and remote learning. Recoletos Multidiscip Res J 2021;9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.32871/rmrj2109.02.06.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Lombardi, D, Shipley, TF, Astronomy Team BT, Chemistry Team, Engineering Team, Geography Team, Geoscience Team, Team P, Bretones, PS, Prather, EE, Ballen, CJ, et al.. The curious construct of active learning. Psychol Sci Publ Interest 2021;22:8–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100620973974.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Gutiérrez, M, Tomás, JM. Motivational class climate, motivation and academic success in university students. Rev Psicodidáctica 2018;23:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicoe.2018.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Doukas, DJ, Ozar, DT, Darragh, M, de Groot, JM, Carter, BS, Stout, N. Virtue and care ethics and humanism in medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ 2022;22:131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03051-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Javed, M. The effectiveness of different teaching methods in education: a comprehensive review. J Social Signs Rev 2023;1:17–24.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Shi, XY, Yin, Q, Wang, QW. Is the flipped classroom more effective than the traditional classroom in clinical medical education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers Media SA; 2025:1485540 p.10.3389/feduc.2024.1485540Suche in Google Scholar

14. Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A, Pawlak, M. Production-oriented and comprehension-based grammar teaching in the foreign language classroom. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012.10.1007/978-3-642-20856-0Suche in Google Scholar

15. Fan, Y. A preliminary exploration of the POA teaching model for ideological and political education in college English. Int J New Dev Educ 2025;7.10.25236/IJNDE.2025.070407Suche in Google Scholar

16. Liu, F. Implementing E-learning in English translation teaching using deep learning models and output-oriented methods. Comput-Aided Des Appl 2024;21:219–35. https://doi.org/10.14733/cadaps.2024.s22.219-235.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Medical education embraces new transformative opportunities

- Review Articles

- Artificial intelligence in medical problem-based learning: opportunities and challenges

- Primary exploration of the One Science integrated curriculum system construction

- Structural and policy overview of medical education in Germany

- Scaling up and dissemination of pre-service education in mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: the way moving forward

- Overview and summary of AI competency framework for teachers

- Shaping the future of healthcare: insights into Japan’s medical education system

- Study on the performance of medical disciplines in Chinese universities based on the data of ShanghaiRanking’s Global Ranking of Academic Subjects

- Basic theoretical frameworks of health education, research needs and practice implications in China

- Koch’s postulates: from classical framework to modern applications in medical microbiology

- Plastic surgery at the crossroads: historical roots and emerging frontiers

- Beyond technical efficacy: challenges and critical concerns of large language model’s impact on medical education in China: a systematic review

- Research Articles

- Impact of early clinical exposure and preclinical tutorial guide on undergraduate dental students in Shanghai

- Capable exam-taker and question-generator: the dual role of generative AI in medical education assessment

- Teaching design for chapter “primary liver cancer” in surgery course based on the clinical theory and clerkship synchronization model in the era of New Medicine

- Integration of a “cardiovascular system” curriculum into an eight-year medical education program: exploration and the experience in China

- AI agent as a simulated patient for history-taking training in clinical clerkship: an example in stomatology

- Student-centered, humanities-guided teaching of the “Medical Practical English” course and its assessment

- The teaching design and implementation of “Intravenous Therapy” in “Fundamental Nursing”

- Biomedical engineering teaching: challenges and the NICE strategy

- Exploratory research on the reform of diversified teaching methods in residency training education: a case study of orthopedics

- Innovative strategies for interdisciplinary medical-engineering education in China

- Construction and optimization of video-triggered cases in problem-based learning

- Exploration and innovation in integrating medical humanities into undergraduate Medical English education

- Innovative application of generating instrument operation videos using QR code technology in experimental teaching

- Constructing a medical humanistic competency framework for medical undergraduate students in China: a grounded theory approach

- Evolution and reform of Medical Microbiology education in New Medical Science era

- Immersive learning in dentistry — evaluating dental students’ perceptions of virtual reality for crown preparation skill development: a multi-institution study

- Enhancing surgical education through output-driven input: implementation and evaluation of the O-SITE teaching model in clinical medical students

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Medical education embraces new transformative opportunities

- Review Articles

- Artificial intelligence in medical problem-based learning: opportunities and challenges

- Primary exploration of the One Science integrated curriculum system construction

- Structural and policy overview of medical education in Germany

- Scaling up and dissemination of pre-service education in mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: the way moving forward

- Overview and summary of AI competency framework for teachers

- Shaping the future of healthcare: insights into Japan’s medical education system

- Study on the performance of medical disciplines in Chinese universities based on the data of ShanghaiRanking’s Global Ranking of Academic Subjects

- Basic theoretical frameworks of health education, research needs and practice implications in China

- Koch’s postulates: from classical framework to modern applications in medical microbiology

- Plastic surgery at the crossroads: historical roots and emerging frontiers

- Beyond technical efficacy: challenges and critical concerns of large language model’s impact on medical education in China: a systematic review

- Research Articles

- Impact of early clinical exposure and preclinical tutorial guide on undergraduate dental students in Shanghai

- Capable exam-taker and question-generator: the dual role of generative AI in medical education assessment

- Teaching design for chapter “primary liver cancer” in surgery course based on the clinical theory and clerkship synchronization model in the era of New Medicine

- Integration of a “cardiovascular system” curriculum into an eight-year medical education program: exploration and the experience in China

- AI agent as a simulated patient for history-taking training in clinical clerkship: an example in stomatology

- Student-centered, humanities-guided teaching of the “Medical Practical English” course and its assessment

- The teaching design and implementation of “Intravenous Therapy” in “Fundamental Nursing”

- Biomedical engineering teaching: challenges and the NICE strategy

- Exploratory research on the reform of diversified teaching methods in residency training education: a case study of orthopedics

- Innovative strategies for interdisciplinary medical-engineering education in China

- Construction and optimization of video-triggered cases in problem-based learning

- Exploration and innovation in integrating medical humanities into undergraduate Medical English education

- Innovative application of generating instrument operation videos using QR code technology in experimental teaching

- Constructing a medical humanistic competency framework for medical undergraduate students in China: a grounded theory approach

- Evolution and reform of Medical Microbiology education in New Medical Science era

- Immersive learning in dentistry — evaluating dental students’ perceptions of virtual reality for crown preparation skill development: a multi-institution study

- Enhancing surgical education through output-driven input: implementation and evaluation of the O-SITE teaching model in clinical medical students