Abstract

Large language model (LLM) advances the medical education process, offering innovative personalized learning approaches or scenarios. This systematic review aims to synthesize updated core themes, evaluate mainstream LLM platforms, highlight concerns regarding the integration of LLM and China’s medical education landscape and compare findings with earlier perspectives. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines, we reviewed literature from November 2022 to April 2025 from PubMed, Web of Science, CNKI, and Wanfang databases. From 915 records selected, 14 high-impact studies were selected through rigorous screening for relevance and quality. High impact abstracts from large academic conferences were also included in the systematic scoping. The number of LLM supporting Chinese language corpora and corresponding case-based learning (CBL) pedagogies in 2024 experienced a significant improvement. Compared to the previous, LLMs demonstrated better performance in accuracy of answering professional medical questions and multi-modal output capability; whereas, issues of academic dishonesty and privacy leakage, technical or logical errors still captured widespread concerns. While encountering challenges in data security, cultural alignment, and equitable regulation, further updates are needed to improve medical LLM standardization and foster a human-machine collaborative educational ecosystem.

Introduction

Mainstream Large language model (LLM) platforms represented by ChatGPT-4o, Gork-3, SuperGPQA and DeepSeek-V3 had demonstrated mighty capabilities in medical text comprehension, clinical reasoning simulation, adaptive content generation, etc. [1], 2]. Globally, LLM was applicable to the specific context of medical education to enhance teaching effect. Institutions such as Harvard Medical School had integrated ChatGPT into case-based learning (CBL) and flipped classroom pedagogy, achieving a notable improvement in diagnostic accuracy among students [3]; meanwhile Google’s Med-PaLM two had attained “expert-level” performance (85 %) on U.S. medical licensing exams (USMLE), compared to its predecessor Med-PaLM, which attained only 60 % accuracy on similar medical licensing questions in USMLE [4]. In China, an original study assessed the performance of different LLM on a question bank designed for Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination in 2020 and 2021 (2020 and 2021 NMLE), GPT-4o achieved accuracy rates of 84.2 and 88.2 %, demonstrating a significant higher overall accuracy than GPT-4 and GPT-3.5 (p<0.001) [5]; another study reviewed the performance of LLMs from Chinese companies/western countries to answer questions in the National Traditional Chinese Medicine Licensing Examination (TCMLE) and evaluated the model’s explainability in answering traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)-related questions to determine its suitability as a TCM learning tool [6]. Currently a promising alternative is to leverage the capabilities of LLM to assist the communication in medical center reception sites in outpatient and preclinical education. From interactive question answering or academic writing refinement to medical education and training, in essence, LLM is crafted to emulate human-like comprehension and capabilities in text generation encompassing diverse content formats, in line with the development of medical teaching resources in China both in terms of functions and application scenarios [7]. These innovations highlight LLM’s potential to address systemic challenges like clinic bedside teaching shortages and resource disparities in preclinical to clinical decision-making process [8]. It is also an encouraging performance to receive attentions from the public for wider attempts of LLM in specific context of medical classroom teaching pedagogies (such as flipped classroom, team-based learning [TBL], problem-based learning [PBL], and CBL), to further verify the quality of medical innovation teaching [9].

The Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Index 2025 highlighted a global surge in public LLM optimism yet regional or professional division remained [10]. The report particularly expands its coverage of the role of LLM in the fields of science and medicine. LLM is transforming from a “data analysis tool” to a “research partner,” capable of participating in hypothesis generation, experimental design, interpretation of complex systems, and even conducting creative research directly involving medical education. The related Nobel Prizes and Turing Awards also confirmed LLM’s contribution to fundamental science and healthcare business [11]. Still, technical limitations, ethical and critical concerns still exist, such as model “hallucinations,” [12] lack of common reasoning, poor explainability, and multi-faceted ethical challenges in medical teaching, which are all key obstacles to the application of LLM in high-risk, high-reliability medical educational scenarios [13]. To better utilize LLM in further medical classroom teaching pedagogies of China, assessing the true capabilities and limitations of LLM itself is also a continuously developing research field [14]. Medical education in China faces concurrent demands for digital education and humanistic quality education [15]. This study aims to conduct a comprehensive review of scientific literature examining LLM’s applications in educational contexts, with particular emphasis on their implementation within China’s medical education system, which can ultimately advance the development of LLM systems to synergize advanced computational capabilities with localized educational corpus in medical training [16].

Methods

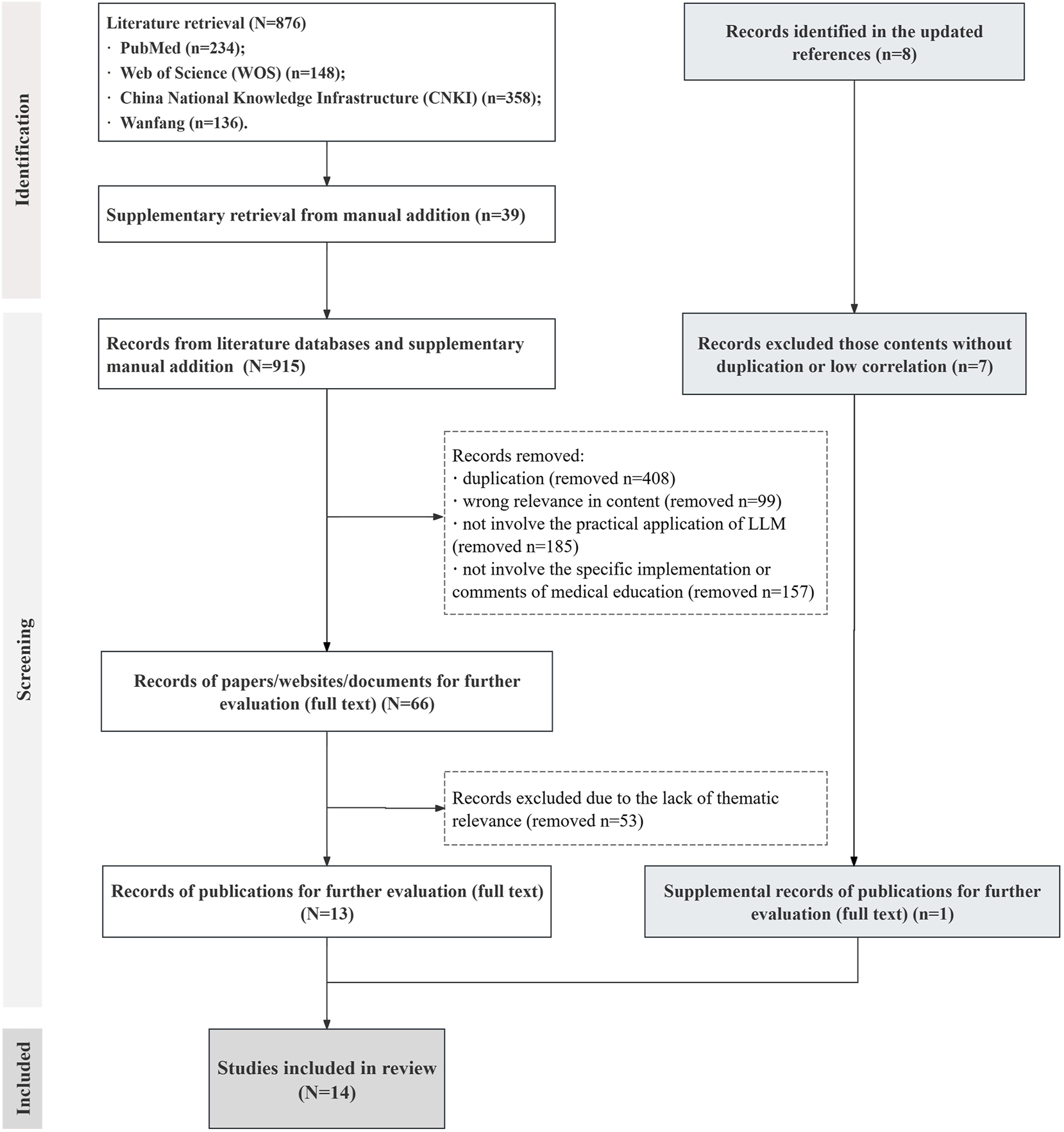

This systematic review employed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [17] framework to investigate: (1) LLMs’ implementation efficacy in China, (2) technical works and opportunities, (3) limitations and ethical compliance from campus to society, and (4) cultural collision and future orientations [18]. Both English and Chinese language databases were comprehensively searched in accordance with the query words for publications from PubMed, Web of Science (two English databases), CNKI, and Wanfang (two Chinese databases). The initial search period was limited from 1st Nov 2022 (related the release of ChatGPT 3.5 in November 2022) to 30th Apr 2025. The medical subject headings terms and search strategy keywords had been attached in Appendix file (Supplementary Appendix 1). The systematic literature review commenced with comprehensive database searches followed by duplicate removal using EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, version X9) as reference management software. The exclusion-inclusion decision protocol was documented in a PRISMA-compliant flow diagram (Figure 1) for transparency [19].

The flowchart of the review search and scoping selection process. Abbreviations: WOS, web of science; CNKI, China national knowledge infrastructure; LLM, large language model.

The initial database search retrieved 876 publications (Supplementary Appendix 1). By additional manual search, 39 additional publications were identified and included in the selection process (the selection process was attached in Supplementary Appendix 2). Materials were reviewed and grouped into categories mainly from English publication databases, Chinese publication databases, to authorized academic conference documents. After removing duplicates and records lacking thematic relevance, 13 publications were retained for screening. In the updated literature search, three additional publications were identified. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, one additional article underwent full-text evaluation and was included in the cohort. Consequently, A total of 14 selected publications with high representativeness or topic relevance were used for subsequent information collation and discussion (the basic information of involved 14 literatures had been attached in Table 1Table 1:), and the basic information and core themes were summarized according to their topics. The flowchart of the search and selection process was attached in Figure 1.

Basic information from included original papers, reviews, reports, and viewpoint articles in reviewing scope.

| Authors | Title | Year | Study type | Summary | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luo D et al. | Evaluating the performance of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in the Chinese national medical licensing examination | 2025 | Research article | This study assessed the performance of different LLMs on a question bank designed for Chinese national medical licensing examination in 2020 and 2021, exploring their potential value in medical education and clinical applications | [5] |

| Ren, Y et al. | Large language models in traditional Chinese medicine: a Scoping review | 2025 | Review article | This study reviewed the performance of LLMs in the areas of assisted diagnosis and treatment of TCM and evaluated models’ explainability in answering TCM-related questions to determine its suitability as a TCM learning tool, presenting a comprehensive perspective of LLMs’ advantages from TCM knowledge counseling and computer aided diagnosis | [6] |

| Jiang Z et al. | Application, challenges, and prospects of artificial intelligence generated content in medical education (in Chinese) | 2024 | Viewpoint | This paper explored how AIGC related technologies can be applied to medical education at different stages, and looking forward to retrieval enhanced generation, multi-agent, and Sora in future medical education. Technical feasibility, ethical standards, social acceptance, laws, and regulations were fully discussed | [7] |

| Yue J et al. | Visualization analysis of CBL application in Chinese and international medical education based on big data mining | 2025 | Review article | Chinese literature focused on students’ learning, teaching methods, courses, application fields and national policy and the ministry of education. The clusters included research national policy guidance, teaching reform, mode and evaluation and various disciplines. CBL holds immense potential for implementation across diverse disciplines, community practices, and special projects within medical education | [9] |

| Maslej N et al. | The 2025 AI index annual report | 2025 | Scientific report | Series analyses of the evolving landscape of LLM hardware, novel estimates of inference costs, and LLM publication and patenting trends summarized mainly from 2024 compared to former achievements | [10] |

| Cooper A, Rodman A | AI and medical education – a 21st-century Pandora’s box | 2023 | Perspective | This article presented evaluation on LLM and medical education’s development situation and limitations, providing speculative discussions from multiple perspectives within scholars, educators and students | [14] |

| Kung TH et al. | Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models | 2023 | Commentary | ChatGPT displayed comprehensible reasoning and valid clinical insights, lending increased confidence to trust and explainability. This study suggested that LLMs such as ChatGPT may potentially assist human learners in a medical education setting, as a prelude to future integration into clinical decision-making | [20] |

| Sandmann S et al. | Benchmark evaluation of DeepSeek large language models in clinical decision-making | 2025 | Research article | This study benchmarked their performance on clinical decision support tasks against proprietary LLMs. 125 patient cases across five specialties (gynecology, internal medicine, neurology, pediatrics, and surgery) were curated from German medical textbooks, covering frequent, less frequent, and rare diseases | [41] |

| Zhui L et al. | Impact of large language models on medical education and teaching adaptations | 2024 | Viewpoint | Viewpoints upon exploring the transformative role of LLMs in the field of medical education, highlighting their potential to enhance teaching quality, strengthening clinical skills training, etc. | [43] |

| Benítez TM et al. | Harnessing the potential of large language models in medical education: Promise and pitfalls | 2024 | Perspective | LLMs offered potential advantages to students, including convenient access to vast data, facilitation of personalized learning experiences, and enhancement of clinical skills development. Challenges included fostering academic misconduct, inadvertent overreliance on LLM, potential dilution of critical thinking skills, concerns regarding the accuracy and reliability of LLM-generated content | [24] |

| Su WH et al. | Prospects for the development of medical professionalism education in the AI perspective: a Qualitative study of Chinese postgraduate medical students’ written reflections | 2025 | Review article | This study collected 44 written reflections from first-year postgraduate students of clinical medicine in China during the spring semester of 2024 on the prospect of applying AI in conjunction with medical professionalism education. A framework for interpretation was provided in the form of a literature review | [25] |

| Lucas HC et al. | A systematic review of large language models and their implications in medical education | 2024 | Review article | This review aimed to explore LLM applications in medical education, specifically their impact on medical students’ learning experiences; key themes included LLM capabilities, benefits such as personalized learning and challenges regarding content accuracy | [26] |

| Shang L et al. | Evaluating the application of ChatGPT in China’s residency training education: An exploratory study | 2025 | Research article | A three-step survey evaluated the performance of ChatGPT in China’s residency training education found that ChatGPT performed poorly in Chinese medical exams, likely due to its training data being predominantly in English. Further research is necessary to address existing limitations and optimize their application | [42] |

| Vrdoljak J et al. | A review of large language models in medical education, clinical decision support, and healthcare administration | 2025 | Review article | A comprehensive literature review was conducted, aiming to explore the current applications, challenges, and prospects in future of LLMs in medical education, clinical decision support, and healthcare administration | [27] |

-

AI, artificial intelligence; CBL, case-based learning; LLMs, large language models; AIGC, artificial intelligence generative content; USMLE, the United States medical licensing examination; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

Results

A total of 14 full-text journal articles, reviews, and comments with high average quotation rate or regional educational characteristics were extracted from 915 retrieved studies. Study types included original research articles (n=3, 21.4 %), reviews articles (n=5, 35.7 %), and perspective/commentary/viewpoint articles (n=5, 35.7 %). Additionally, one academic report was included (n=1, 7.1 %). The basic information had been attached by category in Table 1 with corresponding specific focus themes been briefly illustrated. All 14 included studies identified the inevitable positive effects of LLMs on digital health care educational module, demonstrated the pluralistic perspective from medical education details [28].

The overall layout of LLMs in 2024

Accessible intuitive data from The 2025 AI Index Annual Report and updated information from websites or news clearly documented an increased amount of investment by various open-source or private LLM companies [10]. Compared with previous years’ extensive discussion of regulations, ethics, or concerns, this year’s market emphasis regarding LLMs probably was shifting from “debating LLM” to “investing into LLM” [29]. Technically, this is mainly reflected in three aspects. (1) LLM technologies have permeated all aspects of basic, preclinical and clinical medicine, not only the circumstances among medical students or educators intended to discuss in this review, but a broader scale [30]. Rapidly-updating domestic LLMs were released in 2025 China, such as DeepSeek-V3 and SuperGPQA, along with their wide range of conveniences and deep influence. (2) LLM products with better algorithms and faster iteration speeds were in benign competition [31]. Powerful new iterations, featuring advanced multi-modal output capabilities, swiftly facilitated the combination of educational simulation and medical trials. Furthermore, the underlying logic of LLMs’ deep-thinking processes influenced learner cognition. (3) LLM models with faster iteration speeds could achieve more results in terms of technical capabilities and experimental accuracy and feed them back to various scientific research work [32].

Returning to the application of LLM in the medical field especially in clinical medical education was mainly manifested in these aspects. (1) The transformation of clinical knowledge in medical knowledge databases from review to content enrichment and then to organization. (2) LLM could assist early diagnosis, collaboration between LLM and doctors [33]. (3) Major breakthroughs in image recognition in the interdisciplinary field of LLM and medicine in recent years, which was not closely related to undergraduate medical education but a highlight tool in postgraduate medical education [34]. (4) The application of virtual patient simulation in auxiliary diagnosis, surgery, and drug treatment. In the past two years, some high-score articles had introduced new ideas for discovering new compound drugs with the help of virtual models, which had potential in the medical education of research-oriented postgraduates. (5) The actual deployment of LLM in the medical field [35]. Corresponding studies also reported improved diagnostic accuracy among medical students who utilized tested LLMs. Through training on massive clinical cases for exam preparation or personalized case diagnosis, LLM was inclined to score higher performance in various medical examinations.

LLM’s performance in standardized clinical exams

LLM’s multi-modal input and output capabilities, along with its accuracy rate, were widely tested in various standardized clinical exams. Representative question banks, focusing on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) [20], China’s NMLE [5], and the TCMLE [6], were selected and reviewed to compare the models’ outputs, accuracy rates, and reasoning approaches across different question types such as single/multiple-choice and open-ended items.

Kung’s team [20], using the ChatGPT-3.5, achieved accuracy close to the passing rate (52.5 % vs. 75.0 %) on USMLE test questions (350 official USMLE-2022 sample questions after filtering, covering basic science, clinical diagnosis, and medical ethics, etc.) without specialized medical training, which was higher than the random guessing probability (about 25 %). As the first systematic validation of a universal LLM through physician exams in 2023, the advantages of this research related to medical education were reflected in interdisciplinary knowledge integration, structured clinical reasoning, and the potential for educational assistance. LLM could integrate interdisciplinary content such as pathology and pharmacology into a single answer and generate a hierarchical reasoning chain in open-ended case questions, such as “Gram-negative cocci, meningitis, and preferred antibiotics,” which simplified medical report terminology and improved readability for medical teachers, students, and even patients. However, limitations were also noted, with about 3 % of ChatGPT’s answers containing serious factual errors (such as confusion about drug contraindications), highlighting the risk of relying on pattern recognition rather than true understanding. Additionally, ChatGPT’s involvement in manuscript polishing and viewpoint synthesis led to it being listed as the third author, sparking discussions in the academic community regarding the attribution of AI contributions.

While GPT-3.5 passed the sample question bank in USMLE-2022, it failed in Chinese NMLE as reported by Wang et al. [36], achieving accuracy rates below the passing score (47 % and 45.8 % for the 2020 and 2021 NMLEs). These findings were corroborated by Luo et al. [5], who reported GPT-3.5 accuracy rates of 50.5 % (2020 NMLE) and 50.8 % (2021 NMLE). Luo D’s team compared the performance of adjacent GPT model generations for the 2020 and 2021 Chinese NMLE, revealing that GPT-4o demonstrated superior performance compared to GPT-3.5 and GPT-4. This paper provided the first systematic verification of GPT-4o′s outstanding performance (88.2 % accuracy) in localized medical exams in China. The updated LLM generation scored higher accuracy and validity in complex question types (e.g., A3/A4 and B1 questions). The study emphasized the following limitations: (1) accuracy or reliability – GPT-4o selected the correct answer but provided incorrect logical reasoning analysis; (2) randomness – asking the same question multiple times could result in different answers; (3) educational and ethical risks – excessive reliance on LLM could weaken critical thinking in medical students. To enhance LLM performance in standardized clinical exams, the data volume of medical training sets should cover sufficient sub-disciplines, and specific medical education databases (vertically matched in the content) might be necessary. Expanding language adaptability was also of significant importance.

Another study by Ren et al. [6] compared the performance of Chinese LLMs (Baidu’s Ernie Bot & Ernie Bot-4, Alibaba’s Qwen-max, and Wisdom AI’s GLM-4) and Western LLMs (OpenAI’s ChatGPT-3.5 & ChatGPT-4, Anthropic’s Claude-2, and Google’s Gemini-Pro) on the TCMLE question banks. The quantitative evaluation, assessing the models’ suitability for 2023–2024 TCM tests, revealed a significant gap: all evaluated Chinese models achieved≥60 % accuracy, surpassing the passing threshold, while none of the Western models met this standard. Error pattern analysis focused on core tasks like pattern differentiation. Notably, Chen et al. [37] developed HuatuoGPT-II, a TCM-specialized LLM, which achieved 70 % accuracy on the TCMLE. Collectively, these findings indicate that domain-specific LLMs demonstrate superior TCM comprehension and knowledge mastery. The research highlighted that developing effective TCM LLMs requires localization of language materials. Building a corpus of TCM classics (with annotations and medical cases) could enhance understanding of ancient texts. In medical education, TCM-specialized LLMs generated cases and provided feedback, offering a low-cost alternative to standardized patients (SPs), especially for teaching rare syndromes (e.g., “real winter vacation fever syndrome”).To optimize exam design, questions with >30 % average LLM error rates (often interdisciplinary integration types) were analyzed to refine proposition logic and compare error patterns/accuracy with human student groups. However, due to high error rates (>40 %) on safety-critical topics like acupuncture contraindications, the study proposed LLMs should serve only as teaching tools, not diagnostic aids. The core obstacle for LLM in obtaining a “Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioner License” was not due to technical deficiencies but due to a lack of traditional cultural awareness and clinical responsibility [38].

Comparison of mainstream LLM platforms

The year 2025 has seen the emergence of several new LLMs with enhanced capabilities across various industries, including GPT-4.5, Grok-3, Claude-3.5, SuperGPQA, and DeepSeek-V3 which have become widely used in China. Compared to their predecessors, these models have made notable advancements in medical education [38]. Despite differences in their technical parameters, all five models support deep reasoning and connected thinking modes. GPT, having evolved from version 3.5 to 4.5, boasts rapid model iteration, with its online versions widely cited in literature across different disciplines. Grok-3, with its creator mode and seamless integration with Microsoft’s social platforms and cloud storage, focuses on enhancing user interaction through social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter) [39]. Claude-3.5, while not supporting new user registrations, excels in security and ethical considerations but does not match GPT-4 in handling complex tasks [40]. SuperGPQA has built an extensive general-purpose database, simulating graduate-level knowledge and reasoning across hundreds of capabilities, aiming to establish an interactive human-LLM collaborative system. DeepSeek-V3 demonstrates strong reasoning abilities with Chinese language input but is slightly weaker in image recognition compared to other latest generation of LLMs [21].

In medical education, scholars utilizing LLMs for research or teaching typically needs to focus on the following capabilities: (1) mature architecture and broad application, (2) robust context understanding and text generation, (3) multi-modal input and output support, (4) powerful fine-tuning and adaptability, (5) developer tools and ecosystem support, (6) advanced reasoning and common-sense understanding, and (7) an extensive community and feedback system [41]. In practical applications, scholars are expected to build research or teaching frameworks based on scientific questions, using extensive training datasets to test the LLM’s ability to process both basic knowledge and complex specialized content. Through continual adjustments, they enhance the model’s performance, maintaining high accuracy while expanding its advanced reasoning capabilities. More empirical data on the performance of diverse LLMs within specific medical sub-disciplines is needed.

CBL pedagogies in China

CBL which emphasizes the use of cases as core elements, problems as fundamental components, students as active participants, and teachers as facilitators, has seen significant innovation in Chinese medical education over the past years. Yue et al. [9] examined the incorporation of CBL into China’s medical curriculum and the role of LLMs in this process, providing a visual analysis of CBL’s application in China from 2000 to 2023. Despite its progress, the implementation faced several challenges. CBL was recognized as an effective method to enhance students’ clinical decision-making, problem-solving, and critical thinking skills, with LLMs proving useful in medical CBL classes. However, like challenges faced in other areas, the lack of standardization across institutions led to inconsistencies in case presentation and analysis. While some medical schools successfully integrated CBL into their curricula, the process remains ongoing, with room for further development in creating standardized case libraries and methodologies to better support CBL’s role in medical education [42]. Additionally, flipped classrooms have been successfully integrated with CBL and LLMs, although standardized evaluations of this combined approach are still lacking in China. These approaches have sparked strong student enthusiasm for case reports, oral presentations, and e-poster design, aligning well with the goal of cultivating research-oriented talents [22].

Ethical and critical concerns

Almost all the selected papers highlighted ethical and critical concerns revolving the use of LLMs in medical education. This review focused on subtle differences between recently published papers and earlier articles. The ethical challenges of integrating LLMs into medical education were multi-faceted and required careful consideration to ensure responsible implementation. Data privacy remained the primary concern, as LLM tools often handled sensitive patient data without sufficient safeguards, risking breaches that could undermine patient confidentiality and trust in the healthcare system [43]. Algorithmic bias further complicated this, as biases embedded in training data or algorithms might have skewed diagnoses and case presentations [44]. Bedi et al. [23] emphasized the importance of addressing the needs of specific demographic groups, such as racial and gender considerations, ensuring fairness and equity in the educational process. Jiang et al. [7] also highlighted the ambiguity in defining responsibility when errors or adverse outcomes occurred, pointing to the need for clearer legal frameworks to establish accountability between developers and educators. Experts from the Chinese National Health Commission and the medical education department were expected to collaborate on refining laws and regulations to ensure clear legal protections and responsibility definitions [24].

Discussion

This systematic review illuminates the intricate dynamics of integrating LLMs into China’s medical education system, highlighting both their transformative potential and the persistent challenges that shape their adoption [25]. Drawing on evidence from the 14 studies included in this review, this discussion interprets the findings in the context of the existing literature, addresses their implications, and offers recommendations for educators, learners, and developers to standardize and optimize LLM use in medical education.

As discussed by Sandmann et al. [41], medical faculty and students have shown significant progression: moving beyond simply lacking LLM-based support in clinical decision-making, they are now actively engaged in identifying issues, training LLMs to enhance clinical abilities, and comparing performance details. There was a significant increase in awareness of open-source LLM related applications or knowledges, not only among faculty or academic researchers in all fields, but among the public. Similarly, as Jiang et al. [7] pointed out, clinical medicine professors had already recognized potential issues with improper LLM usage, such as academic dishonesty, discrepancies between generated results and clinical reality, and LLMs’ inability to replace actual hospital workflows or specific steps in research experiments. The growing recognition and discussion of these concerns and insights represent an encouraging development. Compared to the previous, there was a subtle shift in attitudes toward LLM among scholars and the public in China between 2024 and 2025 [25]. The 2025 AI Index Annual Report provided detailed data on economic investments, showing a global trend of “investing in more advanced and powerful LLMs.” This reflects complex critical thinking, tempered by prevailing optimism. The progress of LLMs was tangible, benefiting many medical faculty and students in areas such as extensive research, teaching, machine recognition in clinical systems, article reviews, and text editing. This aligned well with the essential needs of medical education reform in China, and the standardization of related educational courses seemed foreseeable. In medical curricula, LLMs were primarily used to test clinical cases in specific specialties, training clinical logical thinking through these cases [26], 27]. However, LLM systems still faced delays in learning, especially when dealing with newly published articles. For instance, when queried about a recently published Nature Methods paper on unsupervised domain adaptation for sequencing (UDA-seq) [45], LLMs still provided responses focused on outdated information regarding spatial transcriptomics or wrongly associated UDA-seq with bulk RNA sequencing or single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies, which was irrelevant to the topic. Extensive training was crucial, and we recommend establishing specialized medical databases to enhance precision. Balancing technical accuracy with medical humanities is crucial for optimal overall performance. In the classroom, China’s teaching methods such asCBL and flipped classrooms were closely linked with LLMs [45]. These methods aligned well with the demands of China’s National Health Commission and Ministry of Education to develop students, making the process of cultivating excellent medical students into physician-scientists in parallel with the direction of LLM development and integration in medical education.

From the students’ perspective, excessive reliance on LLMs undermined critical and clinical thinking, with practical skills potentially being neglected. This could hinder students’ ability to make independent, informed decisions in clinical practice. Moral dilemmas also stem from potential misalignments between LLM decision-making logic and established medical ethical standards, which could have affected the teaching of essential ethical principles to future healthcare professionals. The lack of humanistic care in current LLM tools was a critical gap, as these models often failed to convey emotional aspects and empathy. Training LLMs to incorporate humanistic elements could help students connect more deeply with patients. According to The 2025 AI Index Annual Report, educators, students, and the public all showed higher enthusiasm for the development and performance of LLMs, with fewer concerns compared to previous years. Addressing these ethical issues is essential to harness the benefits of LLMs in medical education while preserving fairness, accountability, and empathy, ultimately promoting the integration of “LLM clinical education” and establishing a robust oversight framework to ensure safe implementation in the medical field [27].

The long-term integration of LLM into medical education faces significant challenges. Despite its potential, Cooper et al. [14] conveyed judgements that LLM is still in the early stages of development, both technically and practically. While LLMs can enhance learning, they struggle with complex clinical scenarios, particularly in specialized fields that require nuanced, context-specific expertise. For instance, LLMs might encounter with difficulty interpreting culturally embedded knowledge such as pulse diagnosis in traditional Chinese medicine. These limitations highlight the need for ongoing testing and model refinement. Additionally, the legal framework for LLM in education remains underdeveloped, lacking clear accreditation, licensing, and oversight mechanisms, raising concerns about data privacy, algorithmic bias, and accountability. The rapid evolution of medical knowledge further complicates LLM integration, necessitating continuous updates and maintenance, which strains resources. Furthermore, a shortage of interdisciplinary talent capable of bridging AI development and medical pedagogy, coupled with the high cost of training such experts, compounds these challenges [46]. Integrating LLMs into already crowded medical curricula requires creative solutions to optimize teaching schedules without compromising quality. Despite these challenges, the potential of LLMs in medical education remains promising, though their practical application will require sustained collaboration across technology, education, and policy sectors [47].

Returning to the initial question, it is evident that standardized workflows or nationally scalable models (e.g., online open curricula) for integrating LLMs into medical education remain underdeveloped, particularly at the undergraduate level. In this paper, we compared LLM performance across three standardized medical examinations (the USMLE, China’s NMLE and TCMLE). They theoretically revealed discrepancies between LLMs without specific medical training and those fine-tuned on medical dataset, reflecting their respective mastery of core medical knowledge. During undergraduate self-directed learning, LLMs are primarily employed for manuscript drafting and refinement, exam preparation such as generating virtual patient cases or discipline-specific question sets, literature analysis, extracting structured outlines and key information from extensive text or image data, and reducing workload, especially for repetitive tasks. More specialized research and clinical task (including electronic health record management, pathology image interpretation, R script debugging, and developing models for specific clinical question) are currently primarily undertaken by graduate students within China’s mentor-based system. We propose implementing a general education course (online, offline, or hybrid) for junior undergraduates on effectively leveraging LLMs for both in-class and extracurricular learning. This approach is not only feasible but holds significant potential benefits. Simultaneously, it raises critical concerns regarding academic integrity, legal and regulatory compliance, and data privacy, necessitating collaboration among China’s relevant regulatory bodies and domain experts. Initially, undergraduates can utilize LLMs within CBL and flipped classroom to address specific clinical or research questions given at class. Subsequently, they can expand their explorations into review articles or innovation project proposals. Even students encountering research or clinical problems for the first time can gain insights by observing the problem-solving logic of LLMs, thereby enriching their own learning strategies [48]. To foster the LLM-assisted ecosystem, further collaboration among multiple universities or medical centers is essential. How to utilize their clinical data and teaching evaluable materials, and how to develop standardized protocols or publicly accessible online course modules, limitations or orientations mentioned above require adequate resources and scientific experimentation.

This study’s limitations include linguistic bias toward Chinese/English publications and urban-centric sampling. Limitations also existed in sample selection, inferences and conclusions, which might not be consistent with the reader’s affiliation. Future investigations should incorporate minority language resources and non-textual media such as clinical simulation recordings [49]. As China navigates these challenges, its experience offers unique insights into global efforts to harmonize technological progress with cultural preservation in medical education – a balance demanding continued innovation, rigorous oversight, and cross-disciplinary collaboration. China’s experience with LLM in medical education provides a unique lens on global efforts to integrate AI while preserving cultural and educational values. The findings align with international trends. By addressing these through interdisciplinary collaboration, technological iteration, and ethical oversight, China can contribute to a global model of AI-driven education that balances innovation with tradition.

Conclusions

The application of generative LLMs in China’s medical education demonstrates parallel trends of technological advancement and scenario expansion. Despite significant achievements in personalized teaching, case generation, and other fields, core challenges such as data security and assessment efficacy still require addressing through interdisciplinary collaboration, robust ethical standards, and continuous technological iteration. Future research should focus on building an educational ecosystem of “human-machine collaborative” educational ecosystem to drive the transformation of medical education towards better intelligence and precision.

Funding source: the 2025 Teaching Reform Research Project for Ordinary Undergraduate Institutions of Hunan Provincial Department of Education

Award Identifier / Grant number: 202502000136

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the valuable and insightful comments suggested by the editor and the anonymous reviewers.

-

Research ethics: The author provided the written informed consent to participate in this study. All participants signed an informed consent document as required by the institutional ethics committee. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: LLM technology was discussed in this paper.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be interpreted as a potential source of conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was supported by the 2025 Postgraduate Teaching Case Library Construction Project, Central South University [grant number 2025ALK031], Hunan Provincial Department of Education on the 2025 Teaching Reform Research Project for Ordinary Undergraduate Institutions [grant number 202502000136], Hunan Provincial Department of Education on the 2024 Teaching Reform Research Projects for Ordinary Undergraduate Institutions [grant number 202401000378], and Hunan Province Educational Science ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ 2022 Research [grant number ND227254].

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Park, SH, Han, K. Methodologic guide for evaluating clinical performance and effect of artificial intelligence technology for medical diagnosis and prediction. Radiology 2018;286:800–9. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017171920.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Zhou, M, Pan, Y, Zhang, Y, Song, X, Zhou, Y. Evaluating AI-generated patient education materials for spinal surgeries: comparative analysis of readability and DISCERN quality across ChatGPT and deepseek models. Int J Med Inf 2025;198:105871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2025.105871.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Elizabeth, G, Steve, L, Gretchen, E, John, S, Peter, G. How generative AI is transforming medical education: Harvard Medical School is building artificial intelligence into the curriculum to train the next generation of doctors. Harvard Med. the magazine of HARVARD medical school; 2024 Autumn https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/how-generative-ai-transforming-medical-education [Accessed 22 Jun 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

4. Singhal, K, Azizi, S, Tu, T, Mahdavi, SS, Wei, J, Chung, HW, et al.. Large language models encode clinical knowledge [published correction appears in Nature. 2023;620:E19]. Nature 2023;620:172–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Luo, D, Liu, M, Yu, R, Liu, Y, Jiang, W, Fan, Q, et al.. Evaluating the performance of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in the Chinese national medical licensing examination. Sci Rep 2025;15:14119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98949-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Ren, Y, Luo, X, Wang, Y, Li, H, Zhang, H, Li, Z, et al.. Large language models in traditional Chinese medicine: a scoping review. J Evid Base Med 2025;18:e12658. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12658.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Jiang, Z, Feng, S, Wang, W. Application, challenges, and prospects of artificial intelligence generated content in medical education. Chin J ICT Educ 2024;30:29–40. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-8454.2024.08.003.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Jeyaraman, M, Balaji, S, Jeyaraman, N, Yadav, S. Unraveling the ethical enigma: artificial intelligence in healthcare. Cureus 2023;15:e43262. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.43262.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Yue, J, Shang, Y, Cui, H, Liang, C, Wu, Q, Zhao, J, et al.. Visualization analysis of CBL application in Chinese and international medical education based on big data mining. BMC Med Educ 2025;25:402. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-06933-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Maslej, N, Fattorini, L, Perrault, R. The 2025 AI Index 2025 annual report. AI Index steering committee, institute for human-centered AI. Stanford University; 2025. Available from https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report [Accessed 22 Jun 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

11. Rider, NL, Shamji, M. The 2024 Nobel prizes: AI and computational science take center stage. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2025;155:808–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2024.11.040.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Howell, MD, Corrado, GS, DeSalvo, KB. Three epochs of artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA 2024;331:242–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.25057.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Weidener, L, Fischer, M. Teaching AI ethics in medical education: a scoping review of current literature and practices. Perspect Med Educ 2023;12:399–410. https://doi.org/10.5334/pme.954.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Cooper, A, Rodman, A. AI and medical education – a 21st-century Pandora’s box. N Engl J Med 2023;389:385–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2304993.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Wang, C, Zhao, J, Jiao, L, Li, L, Liu, F, Yang, S. When large language models meet evolutionary algorithms: potential enhancements and challenges. Research 2025;8:0646. https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0646.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Liu, X, Feng, J, Liu, C, Chu, R, Lv, M, Zhong, N, et al.. Medical education systems in China: development, status, and evaluation. Acad Med 2023;98:43–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004919.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Tricco, AC, Lillie, E, Zarin, W, O’Brien, KK, Colquhoun, H, Levac, D, et al.. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Qiao, J, Wang, Y, Kong, F, Fu, Y. Medical education reforms in China. Lancet 2023;401:103–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736-22-02629-0.Suche in Google Scholar

19. McGowan, J, Straus, S, Moher, D, Langlois, EV, O’Brien, KK, Horsley, T, et al.. Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol 2020;123:177–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Kung, TH, Cheatham, M, Medenilla, A, Sillos, C, De Leon, L, Elepaño, C, et al.. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digit Health 2023;2:e0000198. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000198.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Kurokawa, R, Ohizumi, Y, Kanzawa, J, Kurokawa, M, Sonoda, Y, Nakamura, Y, et al., Diagnostic performances of Claude 3 Opus and Claude 3.5 Sonnet from patient history and key images in radiology’s “diagnosis please” cases. Jpn J Radiol 2024;42:1399-402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-024-01634-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. He, Y, Wang, Z, Sun, N, Zhao, Y, Zhao, G, Ma, X, et al.. Enhancing medical education for undergraduates: integrating virtual reality and case-based learning for shoulder joint. BMC Med Educ 2024;24:1103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06103-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Bedi, S, Liu, Y, Orr-Ewing, L, Dash, D, Koyejo, S, Callahan, A, et al.. Testing and evaluation of health care applications of large language models: a systematic review. JAMA 2025;333:319–28. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.21700.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Benítez, TM, Xu, Y, Boudreau, JD, Kow, AWC, Bello, F, Van Phuoc, L, et al.. Harnessing the potential of large language models in medical education: promise and pitfalls. J Am Med Inf Assoc 2024;31:776–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocad252.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Su, WH, Zhang, ST, Chen, SH. Prospects for the development of medical professionalism education in the AI perspective: a qualitative study of Chinese postgraduate medical students’ written reflections. Med Teach 2025;47:1–9, https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2024.2445056.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Lucas, HC, Upperman, JS, Robinson, JR. A systematic review of large language models and their implications in medical education. Med Educ 2024;58:1276–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.15402.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Vrdoljak, J, Boban, Z, Vilović, M, Kumrić, M, Božić, J. A review of large language models in medical education, clinical decision support, and healthcare administration. Health Care 2025;13:603. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060603.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Hu, X, Li, J, Wang, X, Guo, K, Liu, H, Yu, Q, et al.. Medical education challenges in Mainland China: an analysis of the application of problem-based learning. Med Teach 2025;47:713–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2024.2369238.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Guo, E, Gupta, M, Deng, J, Park, YJ, Paget, M, Naugler, C. Automated paper screening for clinical reviews using large language models: data analysis study. J Med Internet Res 2024;26:e48996. https://doi.org/10.2196/48996.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Indran, IR, Paranthaman, P, Gupta, N, Mustafa, N. Twelve tips to leverage AI for efficient and effective medical question generation: a guide for educators using Chat GPT. Med Teach 2024;46:1021–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2294703.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Divito, CB, Katchikian, BM, Gruenwald, JE, Burgoon, JM. The tools of the future are the challenges of today: the use of ChatGPT in problem-based learning medical education. Med Teach 2024;46:320–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2290997.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Goh, E, Gallo, R, Hom, J, Strong, E, Weng, Y, Kerman, H, et al.. Large language model influence on diagnostic reasoning: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7:e2440969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.40969.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Kale, M, Wankhede, N, Pawar, R, Ballal, S, Kumawat, R, Goswami, M, et al.. AI-driven innovations in Alzheimer’s disease: integrating early diagnosis, personalized treatment, and prognostic modelling. Ageing Res Rev 2024;101:102497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102497.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Paul, S, Govindaraj, S, Jk, J. ChatGPT versus national eligibility cum entrance test for postgraduate (NEET PG). Cureus 2024;16:e63048. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.63048.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Anibal, J, Landa, A, Nguyen, H, Daoud, V, Le, T, Huth, H, et al.. Generative AI and unstructured audio data for precision public health. Npj Health Syst 2025;2:19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44401-025-00022-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Wang, X, Gong, Z, Wang, G, Jia, J, Xu, Y, Zhao, J, et al.. ChatGPT performs on the Chinese national medical licensing examination. J Med Syst 2023;47:86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-023-01961-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Guo, Z, Shao, W, Liu, B, Yin, W, Mou, L, Li, B, et al.. Large language models as counterfactual generator: strengths and weaknesses. arXiv [Preprint]. 2023; arXiv:2305.14791v1. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.14791.Suche in Google Scholar

38. GBD 2019 Acute and Chronic Care Collaborators, Miranda, JJ, Armocida, B, Correia, JC, Van Spall, HGC, Beran, D, et al.. Characterising acute and chronic care needs: insights from the global burden of disease study 2019. Nat Commun 2025;16:4235. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56910-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. M-A-P Team, Du, X, Yao, Y, Ma, K, Wang, B, Zheng, T, et al.. SuperGPQA: scaling LLM evaluation across 285 graduate disciplines. arXiv [Preprint]. 2025; arXiv:2502.14739v4 [cs.CL]. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.14739.Suche in Google Scholar

40. MobiHealthNews. Microsoft adds Elon Musk’s Grok 3 to Azure, citing healthcare and science use cases. MobiHealthNews. 2025. https://www.mobihealthnews.com/news/microsoft-adds-elon-musks-grok-3-azure-citing-healthcare-and-science-use-cases [Accessed 2025 Jun 22].Suche in Google Scholar

41. Sandmann, S, Hegselmann, S, Fujarski, M, Bickmann, L, Wild, B, Eils, R, et al.. Benchmark evaluation of DeepSeek large language models in clinical decision-making. Nat Med 2025;31:2546–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03727-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Shang, L, Li, R, Xue, M, Guo, Q, Hou, Y. Evaluating the application of ChatGPT in China’s residency training education: an exploratory study. Med Teach 2025;47:858–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2024.2377808.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Zhui, L, Yhap, N, Liping, L, Zhengjie, W, Zhonghao, X, Xiaoshu, Y, et al.. Impact of large language models on medical education and teaching adaptations. JMIR Med Inform 2024;12:e55933. https://doi.org/10.2196/55933.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Huang, H, Zheng, O, Wang, D, Yin, J, Wang, Z, Ding, S, et al.. ChatGPT for shaping the future of dentistry: the potential of multi-modal large language model. Int J Oral Sci 2023;15:29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-023-00239-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Li, Y, Huang, Z, Xu, L, Fan, Y, Ping, J, Li, G, et al.. UDA-seq: universal droplet microfluidics-based combinatorial indexing for massive-scale multimodal single-cell sequencing. Nat Methods 2025;22:1199–212. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02586-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Kumar, T, Sakshi, P, Kumar, C. Comparative study between “case-based learning” and “flipped classroom” for teaching clinical and applied aspects of physiology in “competency-based UG curriculum”. J Fam Med Prim Care 2022;11:6334–8.10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_172_22Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Xu, X, Chen, Y, Miao, J. Opportunities, challenges, and future directions of large language models, including ChatGPT in medical education: a systematic scoping review. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2024;21:6. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2024.21.6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. Moritz, S, Romeike, B, Stosch, C, Tolks, D. Generative AI (gAI) in medical education: chat-GPT and co. GMS J Med Educ 2023;40:Doc54. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001636.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Yang, Y, Chen, S, Zhu, Y, Zhu, H, Chen, Z. Knowledge graph empowerment from knowledge learning to graduation requirements achievement. PLoS One 2023;18:e0292903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292903.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/gme-2025-0009).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Medical education embraces new transformative opportunities

- Review Articles

- Artificial intelligence in medical problem-based learning: opportunities and challenges

- Primary exploration of the One Science integrated curriculum system construction

- Structural and policy overview of medical education in Germany

- Scaling up and dissemination of pre-service education in mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: the way moving forward

- Overview and summary of AI competency framework for teachers

- Shaping the future of healthcare: insights into Japan’s medical education system

- Study on the performance of medical disciplines in Chinese universities based on the data of ShanghaiRanking’s Global Ranking of Academic Subjects

- Basic theoretical frameworks of health education, research needs and practice implications in China

- Koch’s postulates: from classical framework to modern applications in medical microbiology

- Plastic surgery at the crossroads: historical roots and emerging frontiers

- Beyond technical efficacy: challenges and critical concerns of large language model’s impact on medical education in China: a systematic review

- Research Articles

- Impact of early clinical exposure and preclinical tutorial guide on undergraduate dental students in Shanghai

- Capable exam-taker and question-generator: the dual role of generative AI in medical education assessment

- Teaching design for chapter “primary liver cancer” in surgery course based on the clinical theory and clerkship synchronization model in the era of New Medicine

- Integration of a “cardiovascular system” curriculum into an eight-year medical education program: exploration and the experience in China

- AI agent as a simulated patient for history-taking training in clinical clerkship: an example in stomatology

- Student-centered, humanities-guided teaching of the “Medical Practical English” course and its assessment

- The teaching design and implementation of “Intravenous Therapy” in “Fundamental Nursing”

- Biomedical engineering teaching: challenges and the NICE strategy

- Exploratory research on the reform of diversified teaching methods in residency training education: a case study of orthopedics

- Innovative strategies for interdisciplinary medical-engineering education in China

- Construction and optimization of video-triggered cases in problem-based learning

- Exploration and innovation in integrating medical humanities into undergraduate Medical English education

- Innovative application of generating instrument operation videos using QR code technology in experimental teaching

- Constructing a medical humanistic competency framework for medical undergraduate students in China: a grounded theory approach

- Evolution and reform of Medical Microbiology education in New Medical Science era

- Immersive learning in dentistry — evaluating dental students’ perceptions of virtual reality for crown preparation skill development: a multi-institution study

- Enhancing surgical education through output-driven input: implementation and evaluation of the O-SITE teaching model in clinical medical students

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Medical education embraces new transformative opportunities

- Review Articles

- Artificial intelligence in medical problem-based learning: opportunities and challenges

- Primary exploration of the One Science integrated curriculum system construction

- Structural and policy overview of medical education in Germany

- Scaling up and dissemination of pre-service education in mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: the way moving forward

- Overview and summary of AI competency framework for teachers

- Shaping the future of healthcare: insights into Japan’s medical education system

- Study on the performance of medical disciplines in Chinese universities based on the data of ShanghaiRanking’s Global Ranking of Academic Subjects

- Basic theoretical frameworks of health education, research needs and practice implications in China

- Koch’s postulates: from classical framework to modern applications in medical microbiology

- Plastic surgery at the crossroads: historical roots and emerging frontiers

- Beyond technical efficacy: challenges and critical concerns of large language model’s impact on medical education in China: a systematic review

- Research Articles

- Impact of early clinical exposure and preclinical tutorial guide on undergraduate dental students in Shanghai

- Capable exam-taker and question-generator: the dual role of generative AI in medical education assessment

- Teaching design for chapter “primary liver cancer” in surgery course based on the clinical theory and clerkship synchronization model in the era of New Medicine

- Integration of a “cardiovascular system” curriculum into an eight-year medical education program: exploration and the experience in China

- AI agent as a simulated patient for history-taking training in clinical clerkship: an example in stomatology

- Student-centered, humanities-guided teaching of the “Medical Practical English” course and its assessment

- The teaching design and implementation of “Intravenous Therapy” in “Fundamental Nursing”

- Biomedical engineering teaching: challenges and the NICE strategy

- Exploratory research on the reform of diversified teaching methods in residency training education: a case study of orthopedics

- Innovative strategies for interdisciplinary medical-engineering education in China

- Construction and optimization of video-triggered cases in problem-based learning

- Exploration and innovation in integrating medical humanities into undergraduate Medical English education

- Innovative application of generating instrument operation videos using QR code technology in experimental teaching

- Constructing a medical humanistic competency framework for medical undergraduate students in China: a grounded theory approach

- Evolution and reform of Medical Microbiology education in New Medical Science era

- Immersive learning in dentistry — evaluating dental students’ perceptions of virtual reality for crown preparation skill development: a multi-institution study

- Enhancing surgical education through output-driven input: implementation and evaluation of the O-SITE teaching model in clinical medical students