SIDM2022 15th Annual International Conference

October 16-18, 2022

Planning Committee

Andrew Olson, MD | Chair

Christina L. Cifra, MD, MS | Chair

Dan Berg

Eliana Bonifacino, MD, MS

John D. Bundrick, MD, MACP

Joseph A. Grubenhoff, MD, MSCS

Helen Haskell, MA

Abraham Jacob, MD, MHA

Marie Jaffe

Rebecca Jones, MBA, BSN, RN, CPHRM, CPPS

Janice Kwan, MD, MPH

David L. Meyers, MD, MBE, FACEP

Sandra Monteiro, PhD

Ruth Ryan, RN-ret, BSN, MSW

Kathryn Schaefer, MSN, RN, CPHRM, CHCP, FASHRM

Verity Schaye, MD, MHPE

Suz Schrandt, JD

Divvy K. Upadhyay, MD, MPH

Ronald Wyatt, MD, MHA

Abstract Selection Committee

Christina L. Cifra, MD, MS

Janice Kwan, MD, MPH

Ava Liberman, MD

Najlla Nassery, MD, MPH

Rebecca Jones, MBA, BSN, RN, CPHRM, CPPS

Thilan Wijesekera, MD, MHS

Poster Session 1

Sunday, October 16

5:00 PM – 6:00 PM

A Real Headache: A Delayed Diagnosis of GCA

N. Gregorich 1, B. Pollitt Golden1

1University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Milwaukee, WI

Learning Objectives: 1) Understand real world presentation of Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA). 2) Identify types of bias leading to a delayed GCA diagnosis.

Case Report: A 72-year-old male presented with multiple complaints, including scrotal pain, transient vision loss, fatigue, weight loss and new headaches. ED work-up showed leukocytosis and aortic dilation on imaging. Clinicians recommended further work-up for possible infection but did not raise concern for GCA. The patient declined admission but re-presented 2 days later endorsing similar symptoms. Ultrasound showed epididymitis for which he received Bactrim. He presented to clinic several days later with “confusion” which was attributed to Bactrim. The following week, he represented with scrotal pain and confusion. Ultrasound showed improving epididymitis, but his symptoms were attributed to epididymitis, and he was prescribed cefpodoxime. Three days later, he re-presented with worsening headaches, temporal swelling, and elevated CRP, prompting admission. He underwent temporal artery biopsy which confirmed GCA.

Discussion: GCA is the most common systemic vasculitis and should be considered for patients over 50 who have new headaches, visual disturbances, and vascular abnormalities. Patients may also present with confusion. Prompt identification and treatment with corticosteroids is imperative as untreated GCA can progress to blindness. Despite his age and multiple complaints consistent with GCA, this diagnosis was not initially considered. His presentation was attributed to epididymitis, which interestingly has been associated with GCA. This patient is emblematic of broader issues in prompt GCA diagnosis, which takes a mean of 9 weeks from symptom onset. Heuristics are a helpful tool for physicians to make diagnoses. However, using mental shortcuts may have played a role in this delay, as GCA is more common in females. Anchoring bias may also have contributed. This patient endorsed persistent scrotal pain and was diagnosed with epididymitis, which may have clouded his additional complaints.

Anchoring on Ultrasound: Need for Point-of-Care-Ultrasound Competencies in Medicine Residencies

K. Huber 1, E. Breitbach2, M. Knees1

1University of Colorado, Aurora, CO

2Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, Aurora, CO

Learning Objectives: Describe existing standards for point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) training for resident physicians. Highlight risks of utilizing new technologies for trainees without clear standardization or proof of competency.

Case Description: A 57-year-old man with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction presented to the hospital for evaluation of lower extremity edema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and syncopal episodes. His initial exam was notable for normal vital signs, 2+ pitting edema, and elevated JVP. Initial labs revealed a normal CBC and CMP, normal troponin, and a pBNP of 9000. His EKG had diffusely low amplitude voltages and chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly. The overnight admitting resident utilized POCUS—for which they had received informal training during residency—to perform a bedside cardiac ultrasound where they noted no appreciable pericardial effusion. During morning handoff, the resident noted the lack of pericardial effusion on bedside ultrasound and the primary team-initiated treatment for presumed decompensated heart failure. During dialysis the following day, the patient became more hypotensive with a pulsus paradoxus of 14. A formal TTE was obtained which demonstrated a large circumferential pericardial effusion; the patient was taken for emergent pericardiocentesis.

Discussion: Point-of-care ultrasound is rapidly becoming a standard tool utilized during internal medicine residency training. While there is growing evidence regarding the clinical and educational merits of implementing POCUS training, there is no clear guidance on quality markers of proficiency. We present a case of early anchoring bias based on inaccurate POCUS assessment that resulted in delayed diagnosis and care. Competency assessments and standardization, like procedure certifications mandated elsewhere in graduate medical training, are one way to prevent similar errors. Proficiency assessments are a necessary component for much of residency training and should be extended to the rising use of POCUS in care.

Assessing Clinical Reasoning in Medical Students Using a Virtual Patient Simulator

R. Abdulnour 1, M. O’Rourke2, T. Smith3

1Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

2NEJM Group, Waltham, MA

3Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, Erie, PA

Background:

– NEJM Healer is a computer-based simulator using illness script theory to enhance the teaching and assessment of clinical reasoning.

– During a virtual patient encounter, learners must select data, write problem representations, build a differential diagnosis, and propose a management plan

– After the encounter, learners perform informed self-assessments of their problem representations, management plan, and level of confidence in their lead diagnosis.

– They are given formative assessment on their lead diagnostic accuracy, differential diagnostic accuracy (DDxA), and illness script concordance.

– Educators can view all the feedback data in the NEJM Healer Educator Portal, including informed self-assessment of problem representations, management plan, and level of confidence.

Objectives:

– To augment deliberate practice for over 1100 medical students at Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine (LECOM) dispersed across several campuses.

– To compare performance in NEJM Healer with learner clinical experience in a cross-sectional analysis.

Results:

– Normalized data was used to support early identification of learners who could use additional support for developing clinical reasoning skills using a defined framework.

– Comparative cross-sectional analysis of all encounters showed that pre-clerkship students spent significantly more time per encounter and had significantly lower diagnostic accuracy than post-clerkship students.

– In one encounter of medium-difficulty, DDxA was significantly lower after history-taking than after physical exam and review of diagnostic interventions (Fig. 1). DDxA of pre-clerkship students was significantly lower than post-clerkship students at every stage of the encounter.

– Post-clerkship students were significantly more confident of their diagnosis than pre-clerkship students.

– Diagnostic accuracy in NEJM Healer significantly but weakly correlated with NBOME COMLEX-USA Level 2 CE test scores.

Conclusion:

– Performance in NEJM Healer identified students who could use additional support for developing clinical reasoning skills.

– Clinical reasoning performance in NEJM Healer correlated with clinical-student experience level.

– While differential diagnostic accuracy was significantly correlated with COMLEX Level-2 CE scores in this large sample size, very little of the variation between students was predicted by their knowledge test scores, indicating that clinical reasoning requires a distinct set of skills in addition to clinical knowledge.

Challenging Nursing Students to Apply Clinical Judgment in an Online Learning Environment

L. Benike 1, R. Linck2

1University of Minnesota, Rochester, MN

2University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MN

Purpose/Problem: For health sciences students, achieving clinical judgment demands the ability to recognize clinical cues, generate and weigh hypotheses, and take action to arrive at a satisfactory clinical outcome. Teaching to achieve clinical judgment is important and complex and requires the ability for learners to actively engage with complex clinical scenarios in a realistic context.

Description of Program: We utilized Zoom and Mentimeter technologies to facilitate an online “Active Learning Day” in an advanced nursing course for 175 senior Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) students with the primary objectives of demonstrating clinical judgment and responding effectively to acute changes in patient conditions. During a 115-minute synchronous course session, students experienced complex case studies in patient care, care interruptions that required immediate intervention, NCLEX-style questions, problem solving in pairs, and faculty-led debriefing. Students were challenged to demonstrate clinical judgment by Assessing, Analyzing, and Acting upon recognized clinical cues in real-time. Mentimeter technology and Zoom breakout rooms were used to support anonymous participation amongst participants.

Outcomes: The Active Learning Day was designed to: a) achieve high learner engagement with case-based learning scenarios, b) achieve good clinical judgment as evidenced by learner responses to clinical scenarios. Participants were surveyed on their learning experience. We received a 35% survey response rate. Of those who responded, 77% (48/62) reported high engagement throughout the session, 95% (59/62) agreed the scenarios included during the session felt applicable to clinical practice, and 84% (52/62) of participants agreed that the session left them feeling better prepared to manage similar clinical situations in the future.

Discussion and Significance: Interactive learning supported by digital technology provides clinical learners with opportunities to apply clinical judgment to patient care scenarios. The use of anonymous submission functions within Mentimeter supports all learners to submit their thoughts, ideas, and responses without fear of judgment from their peers or instructors. Students engage with delivered content through Zoom connection, and by following along in a simplified format in Mentimeter using an additional personal device such as a cellphone or tablet. Learners without access to an additional device are able to engage with Mentimeter using an internet browser on their computer. Anonymity enhances the ability and willingness for students to share their thinking, which often results in richer sharing and enhanced individual metacognition during the learning session.

Characteristics of Diagnostic Errors in Outpatients Referred for Diagnosis in a University Hospital

S. Katsukura 1, T. Shimizu2, Y. Otaka2, Y. Harada2

1Dokkyo Medical University, Mibu, Japan

2Department of Diagnostic and Generalist Medicine, Dokkyo Medical University, Mibu, Japan

Background: The characteristics of diagnostic errors in primary care and emergency department settings have been investigated; however, there are scarce data regarding the characteristics of diagnostic errors in referred outpatients for diagnosis in the tertiary care setting. This study aimed to describe the characteristics of diagnostic errors in outpatients referred to a tertiary hospital for diagnostic evaluation.

Methods: We reviewed medical records of consecutive outpatients referred for diagnosis to the Department of Diagnostic and Generalist Medicine in a university hospital between January 1st, 2019, and December 31st, 2019. Diagnostic errors were judged using the Revised Safer Dx Instrument. In the cases of diagnostic errors, we conducted further reviews to clarify the contributing factors and outcomes of diagnostic errors using the Safer Dx Process Breakdown Supplement. Age, sex, referral pattern, the reason for referral, the final diagnosis, the duration, and the number of outpatient visits between the index visit and the time the final diagnosis was made, the outcome of diagnostic errors, and contributing factors for diagnostic errors were collected.

Results: A total of 534 cases were included in the analysis. Diagnostic errors were observed in 12 cases (2.2%). In the cases of diagnostic errors, the median age was 68 (57-76) years, 5 (41.7%) were women, and 5 (41.7%) were referred from other departments within the hospital. The most common reason for referral was abnormal test results (3/12, 25.0%). Based on the ICD-10 classification, the most common missed diagnosis category was ""Neoplasms"" (6/12, 50.0%: lung cancer, 2; gastric cancer, 2; pancreatic cancer, 1, cardiac myxoma, 1). The median duration and number of outpatient visits between the index visit and when the final diagnosis was made were 169 (111-310) days, and 8 (4-12) visits, respectively. Diagnostic errors resulted in temporary or permanent harm in 8 (66.7%) cases. The top three most common contributing factors for diagnostic errors were ""problems with data integration and interpretation"" (8/12, 66.7%), ""problems ordering diagnostic tests for further workup"" (5/12, 41.7%), and ""problems with monitoring patients through follow-up"" (3/12, 25.0%).

Conclusion: In referred outpatients who experienced diagnostic errors, neoplasms were missed in 50%, and 67% of diagnostic errors resulted in temporary or permanent harm. Considering the period from the index visit to the time that the final diagnosis was made in this study, reviewing 6-12 months of medical records should be required to survey diagnostic errors for referred outpatients in tertiary care settings.

Codesigning Tools to Overcome Barriers to Diagnostic Safety for Underrepresented Patients

T. Giardina 1, S. Jefferson2, M. Graber3

1Baylor College of Medicine and Houston VA, Houston, TX

2Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

3Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, Alpharetta, GA

Background: The NASEM report, Improving Diagnosis in Health Care, recommends partnerships with patients and families to facilitate patient engagement in the diagnostic process. While several such efforts have begun, engagement with marginalized patients needs additional focus as many patients may not be specifically included in such initiatives. Increased engagement with diverse patient populations will ensure identification of diagnostic issues that would otherwise go unnoticed and create a foundation for reducing inequality in diagnostic safety. Using a health equity lens, we conducted codesign workshops to develop a patient-centered structured tool to engage underrepresented patients in the diagnostic process following an outpatient visit.

Methods: To identify potential participants, we contacted (i.e., telephone and email) local community organizations focused on health equity and access in marginalized communities and a Veterans association in Houston, Texas. We met with the leadership at two organizations and presented a project overview and objectives. Once approved, we recruited participants via email. Interested participants were split into two groups, community health workers (CHWs, n= 5) and Veterans (n=11). To reduce burden, workshops were designed to be completed in 3-4 one-hour meetings and included: 1. Empathy mapping to identify patient concerns, 2. Developing a list of high priority concerns, 3. Developing questions, and 4. Reviewing final tool design. Workshops were conducted by an experienced qualitative methodologist via Zoom. Participants were compensated for their time. Together participants and the facilitator co-produced key areas of concern and began developing associated questions.

Results: Thus far, we have conducted 9 one-hour codesign workshops with 16 participants total. Participants were majority female (n=14) and the groups were diverse in race and ethnicity. Four participants self-disclosed as disabled. Empathy mapping helped create a shared understanding amongst participants about the experiences of diagnostic errors and to identify concerns and gaps in care. Key concerns included: bedside manner (e.g., I’d rather be sick than pushed [rushed] through. I can feel the difference), communication (e.g., There is a difference between listening and feeling heard), uncertainty (e.g., multiple referrals and diagnosis is unknown) and bias (e.g., They [doctors] do not believe Black and Brown patients.). We are currently developing questions to represent these key diagnostic safety concerns.

Conclusions: While this tool remains in development, working closely with community members holds promise for identifying relevant diagnostic concerns in diverse patient populations.

Database Design: Ensuring Positive Fecal Immunochemical Test Follow-up and Diagnostic Error Tracking

P. Foulis 1, K. Legard1, S. Bhaskar1, J. Kreinbrook2*

(*Presenting Author)

1James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital, Tampa, FL

2Tampa VA Clinical Research and Education Foundation, Tampa, FL

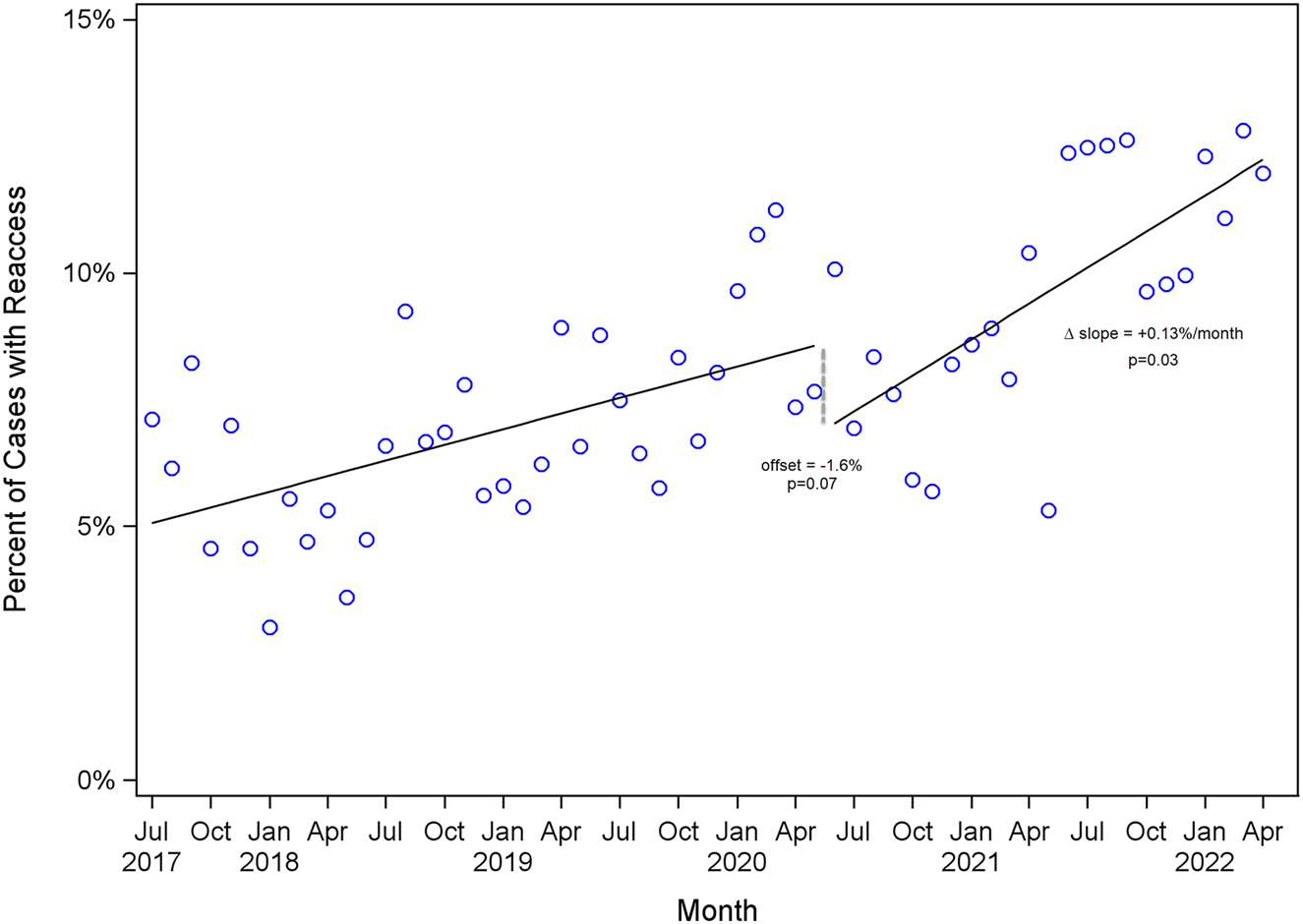

Statement of the Problem: The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted colorectal cancer (CRC) screening globally, reducing screening colonoscopies. In the Veterans’ Health Administration (VHA), we overcame this by utilizing mail-out fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), a stool-based screening test. However, minimizing inappropriately administered FIT and following-up on any positive FIT (+FIT) with diagnostic colonoscopy became noticeable issues in our system. Inappropriate FIT testing is a diagnostic error as it lacks the appropriate sensitivity and specificity outside of CRC screening. Alongside mail-out FIT, we initiated a FIT navigator program to facilitate +FIT follow-up. While navigators traditionally aid in test follow-up, overcoming known patient, provider, and system-level barriers; they are also poised to capture data regarding inappropriate FIT utilization (i.e., diagnostic error).

Process Improvement Description: A FIT navigator process was introduced in late 2020 at our local VA, James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital, with no improvement in 180-day compliance: the uptake of colonoscopy <180 days (180-day compliance). We noted a steady decline of this metric even after FIT navigator introduction, prompting this QI project which began with retrospective chart review and stakeholder meetings.

Findings to Date: Of 512 index +FIT from October 2020 (FIT navigator introduction) to August 2021, 214 did not meet 180-day compliance and 14 had an unknown colonoscopy completion due to poor documentation, yielding 286 (65.1%) with compliant follow-up. When removing inappropriately ordered FIT (N=123; 24.0%), the successful follow-up proportion dropped from 65.1% to 60.0%. In the 214 who did not meet our metric, 75 refused follow-up (35.0%). 24 of these (33.3%) failing to reach the FIT navigator. Poor system communication and transportation issues were also major factors. This data informed our inclusion of inappropriate FIT tracking into our planned intervention, a Microsoft Access database which semi-automates +FIT data retrieval and navigator tasks while also tracking FIT order appropriateness.

Lessons Learned: While +FIT navigation is an evidence-based intervention, local implementation teams should incorporate inappropriately ordered FIT tracking to capture diagnostic error. Additionally, interventions should place navigators as close as possible to the +FIT result, easing the burden on primary care providers and ensuring that barriers to follow-up are identified.

Deliberate Practice of Clinical Reasoning Reveals Important Diagnostic Justification Insights

J. Waechter 1, L. Zwaan2, J. Staal2

1University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

2Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Purpose: Diagnostic errors are a large burden on patient safety and improving clinical reasoning (CR) education could contribute to reducing these errors. To this end, calls have been made to implement CR training as early as the first year of medical school. However, much is still unknown about pre-clerkship students’ reasoning processes and which aspects could be improved. The current study therefore aimed to observe how pre-clerkship students use clinical information during the diagnostic process.

Methods: In a prospective observational study, first- and second-year medical students at one medical school completed self-directed online CR diagnostic case vignettes. CR skills that were measured included: creation of the differential diagnosis (Ddx), diagnostic justification (DxJ), ordering investigations, and the final ranking of the most probable diagnosis. We also analyzed how students used history, physical exam, and investigation data, as well as pertinent positive and pertinent negative data, in their DxJ process.

Results: 121 of 133 (91%) medical students consented to the research project and completed 10 clinical cases each. We collected over 100 data per case on average, analyzing over 121,000 data. Compared with scores obtained for creation of the Ddx, ordering tests, and identifying the correct diagnosis, students scored much lower with DxJ (30-48%, p < 0.001). Specifically, students under-utilized physical exam data (p < 0.001) and pertinent negative information (p < 0.001). We observed that DxJ scores increased 40% with 10 practice cases (p < 0.001). We analyzed scores for building a Ddx, DxJ and ordering investigations and observed that higher scores in each category were independently associated with lower rates of misdiagnoses.

Conclusions: We implemented deliberate practice with formative feedback for CR starting in the first year of medical school. Students underperformed in DxJ, particularly with analyzing the physical exam data and pertinent negative data. We observed improvement in DxJ performance with increased practice and an association between higher scores in individual CR tasks and lower rates of misdiagnosis.

Development and Psychometrics of the Diagnostic Competency During Simulation-based Learning Tool

L. Burt 1, A. Olson2

1University of Illinois Chicago, Evanston, IL

2University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, MN

Even though diagnostic errors impact as estimated 12 million people in the United States each year, educational strategies that foster diagnostic accuracy among healthcare learners remain elusive (1-4). One solution is to focus explicitly, rather than tacitly, on competencies that are fundamental for diagnostic excellence. Individual diagnostic reasoning competencies address actions, processes and knowledge that contribute to diagnostic accuracy through information acquisition, problem representation, prioritization, decision support, and critical thinking (5). As a learning modality that allows educators to directly observe learner behaviors, simulation-based learning can be leveraged to provide behaviorally anchored feedback that will foster student competency mastery. Currently, there are no tools that comprehensively address individual diagnostic reasoning competencies during simulated learning (6-14). Our research team sought to remedy this deficit by developing and exploring psychometric properties of the “Diagnostic Competency During Simulation-based (DCDS) Learning Tool.” The purpose of this study is (1) to develop an assessment tool to quantify learner progression towards mastery of the individual diagnostic reasoning competencies during simulation and (2) to explore preliminary evidence of reliability and validity. The DCDS Learning Tool is a 28-item, behaviorally anchored tool assessing six individual diagnostic reasoning competencies (1). Items are stratified between six competencies and are rated on a 4-point ordinal scale. Educators are encouraged to leverage ratings to analyze learner behaviors, identifying trends and asymmetry between competencies, in preparation for feedback conversations. Final individual competency domain scale CVI scores ranged between 0.9175 and 1.0 and the total scale CVI score was 0.96, reflecting adequate construct representation. Inter-rater reliability is currently pending. The DCDS tool expands the current landscape of diagnostic reasoning assessment by providing educators with granular, actionable, individual competency-specific assessment measures. Linking competencies to behaviors observed during simulation, the tool can be applied by educators to facilitate conversations guided by principles of high-quality feedback—i.e., explanatory feedback tied to specific behaviors. As more healthcare disciplines pivot to competency-based education, integrating this tool into the existing landscape of simulation-based learning will aid educators striving to foster diagnostic competency. Exploratory data supports the DCDS Learning Tool as a reliable and valid instrument that can be utilized by educators to promote individual diagnostic reasoning competency growth.

Diagnostic Analysis of Initial Non – Contrast CT for Abdominal Pain During a Contrast Shortage

J. Ha 1, J. Thomas2

1Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA

2Penn State Health, Dept. of Radiology, Hershey, PA

Background: An increase in COVID–19 in 2022 resulted in significant shortage of Iohexol Iodinated Contrast media. Our institution adopted contrast restrictions on 5/9/2022, including that patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with atraumatic abdominal pain would not receive contrast. ACR recommendations for imaging of abdominal pain primarily recommend CT with contrast as the most appropriate imaging. This presents an opportunity to assess patterns of contrast utilization for improvement.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective review of CT abdomen & pelvis (a/p) exams without contrast ordered in the ED for abdominal pain from 5/9/2022-5/27/2022. Cases were categorized by indication for imaging as per ACR appropriateness criteria. Appropriateness of CT without contrast ordered was compared to appropriateness of CT with contrast. Clinical outcomes were qualitatively categorized into three groups. We also recorded types of final diagnoses, patient repeat or additional imaging, and patient outcomes.

Results: 421 CT a/p examinations were ordered in the ED from 5/9/2022-5/27/2022. 164 were excluded due to indications of trauma and sole flank pain for renal calculus. 257 cases were screened for ACR appropriateness, and 126 cases qualified for ACR appropriateness. CT with contrast was more appropriate in 86 cases, equally appropriate with ACR criteria evidence level of 4,5,6 in 16 cases and equally appropriate with ACR evidence level of 7,8,9 in 24 cases. Clinical outcome distribution is summarized in the figure. The most common final diagnoses were no diagnosis (36/126), appendicitis (9/126), and small bowel obstruction (8/126). In clinical diagnoses where CT with contrast was more appropriate abdominopelvic CT findings were still well visualized. In diagnoses where CT with and without contrast were equally appropriate, 30% (12/40) patients had no CT findings and were discharged. In diagnoses where CT with contrast was more appropriate 24% (21/86) patients had no CT findings and were discharged with none returning to the ED within 72 hrs.

Conclusion: For imaging indications where CT with and without contrast are equally appropriate this preliminary data supports CT without contrast as an acceptable alternative. This preliminary analysis suggests that CT without contrast may be an acceptable alternative for contrast CT, with room for improvement in resource utilization.

Diagnostic Correction in a Curious Case of Pylephlebitis

N. Faraci 1, G. Olenginski1

1University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA

Learning Objectives: 1. Explain the diagnostic process for the rare diagnosis of pylephlebitis. 2. Discuss how additional testing was needed beyond the preferred diagnostic methods to lead to the correct diagnosis.

Case Information: A 67-year-old woman with history of diverticulitis presented with subacute fatigue, malaise, anorexia, and progressive epigastric discomfort. On examination, she was afebrile, BP 84/53 mmHg, HR 134 bpm, and mildly tender to palpation in the epigastrium with decreased capillary refill. Labs demonstrated leukocytosis to 20.9 K, mild cholestatic liver injury, and lactic acidosis to 2.2 which prompted CT scan of her abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast to assess for a source of her sepsis. Acute sigmoid diverticulitis without abscess or perforation was demonstrated, as well as ill-defined right liver lobe hypodensity with intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation with associated narrowing/effacement of the right portal vein concerning for cholangiocarcinoma. She was resuscitated with crystalloid and started on empiric piperacillin-tazobactam. The next day she underwent MRCP which demonstrated pylephlebitis and thrombosis of the posterior right portal vein. Her blood cultures were without growth. She was treated with 4 weeks of piperacillin-tazobactam as well as a 3-6 month course of anticoagulation with apixaban.

Discussion: Pylephlebitis is infective thrombosis of the portal vein and can complicate intraabdominal sepsis of any etiology. Diagnosis is often delayed due to its nonspecific presenting symptoms, and it is an uncommon condition. CT and ultrasonography are typical first line diagnostic studies for pylephlebitis. This is where we were led astray in the present case, since the findings of pylephlebitis on CT scan were called as concerning for cholangiocarcinoma by the interpreting radiologist. Pursuing further imaging with MRCP allowed re-direction to the final diagnosis, which had profound impacts on her management – long-term antibiotics and anticoagulation…rather than surgical consultation.

Diagnostic Delays of MSK Infections and Clinical Pathway Execution

J. Grubenhoff 1, L. A. Bakel1, J. Searns1

1University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Background: Clinical pathways (CPs) aim to align best evidence with local practice and resources and overcome the bounded rationality of diagnosticians. Some studies indicate reductions in diagnostic error (DxE) attributable to shorter time to diagnosis for emergent conditions after CP implementation. Few studies have explored diagnostic delays associated with incomplete execution of CP elements. Our objectives were to compare the clinical characteristics of patients with and without delayed diagnosis of musculoskeletal infections (MSKI) and identify repeatedly missed opportunities when applying an MSKI diagnostic CP.

Methods: E-trigger followed by manual screening identified children with unplanned admission within 10 days of index ED encounters from 1/1/2018-12/31/2021. Cases with disparate but potentially related diagnoses at index encounter and hospital discharge were reviewed using the Revised SaferDx to determine presence of DxE. The diagnostic evaluation of patients discharged with pyomyositis, osteomyelitis or septic arthritis during the index encounter was compared to the recommended diagnostic testing and consultation in the CP. Descriptive statistics comparing patients with and without MSKI diagnostic delays were performed: X2 for proportions and Wilcoxon Rank Sum for continuous variables.

Results: 3407 patients met e-trigger criteria. 774 (22.7%) screened in for SaferDx review and 163 had DxE. 33 patients (4.2%) had MSKI; 23 (63.6%) experienced diagnostic delays accounting for 14.1% of all DxEs. Patients did not differ in age, sex, race, language, triage acuity or presence of fever. Patients with MSKI DxE more often had fever + limb/back pain (57.1% vs 16.7%; p=0.02). The differential diagnosis included MSKI more often in patients with DxE (61.9% vs 25.0%; p=0.04). Patients with MSKI DxE returned 4 days sooner than those without DxE [median days to diagnosis 2.9 (IQR 1.9-3.8) vs 6.9 (IQR 3.8-8.6); p<0.01]. The figure shows the diagnostic trajectories of the two groups.

Conclusions: Despite having a history concerning for and differential diagnosis including MSKI, patients with delayed diagnoses demonstrated three distinct CP failure points: not receiving indicated labs; not receiving consultation; and not receiving indicated imaging. Incomplete execution of an MSKI CP delayed diagnosis of MSKI.

Driving Close the Loop Communication with Medicaid Quality Incentive

T. Anderson 1

1Washington State Hospital Association, Seattle, WA

The Medicaid Quality Incentive program is a driver of change and reward for accomplishments of quality improvement for the state. Hospitals in Washington State can earn a one percent incentive payment under the Medicaid Quality Incentive Program. The payment is funded in part from a Safety Net Assessment and federal matching dollars. The Association develops 12 quality measurement guidelines for the Medicaid Quality Incentive each year. In selecting the measures, national guidelines and clinical experts are utilized to identify potential measures that are evidence-based and significant for Medicaid patients. The final selection of measures was done by the Medicaid Administrator for the state. Eligible hospitals wishing to earn the quality incentive will report on accomplished measures for specified care units. One of the newer association strategies for the Safety & Quality team and the hospitals is Diagnostic Excellence. This topic does not have well-established, published, and satisfactory baseline measures. The Association’s Subcommittee on Diagnostic Excellence desired to understand the completeness of close-the-loop communications surrounding critical lab and imaging results to an actionable provider. Data was collected on critical lab and imaging studies communications, as well as the total number of critical labs and studies as well as the total number of completed labs and studies for a hospital. Aggregated findings will be discussed as well as plans to continue to drive improvement on this measure.

Electronic Triggers to Study Diagnostic Errors in Pediatric Emergency Departments

P. Mahajan 1, A. Payne2, K. Shaw3, H. Singh4, M. Carney1, K. O’Connell2, D. Morrison Ponce5, J. Chamberlain2, J. Corboy6, R. Ruddy7, E. Alpern8, B. Ku9, N. Klekowski1, E. White1, A. Krack10, E. Freiheit1

1University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

2Children’s National Health System, Washington, D.C.

3University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

4Baylor College of Medicine and Houston VA, Houston, TX

5Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences F. Edward Hebert School of Medicine, Bethesda, MD

6Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL

7University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

8Northwestern University, Evanston, IL

9Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

10University of Colorado, Denver, Denver, CO

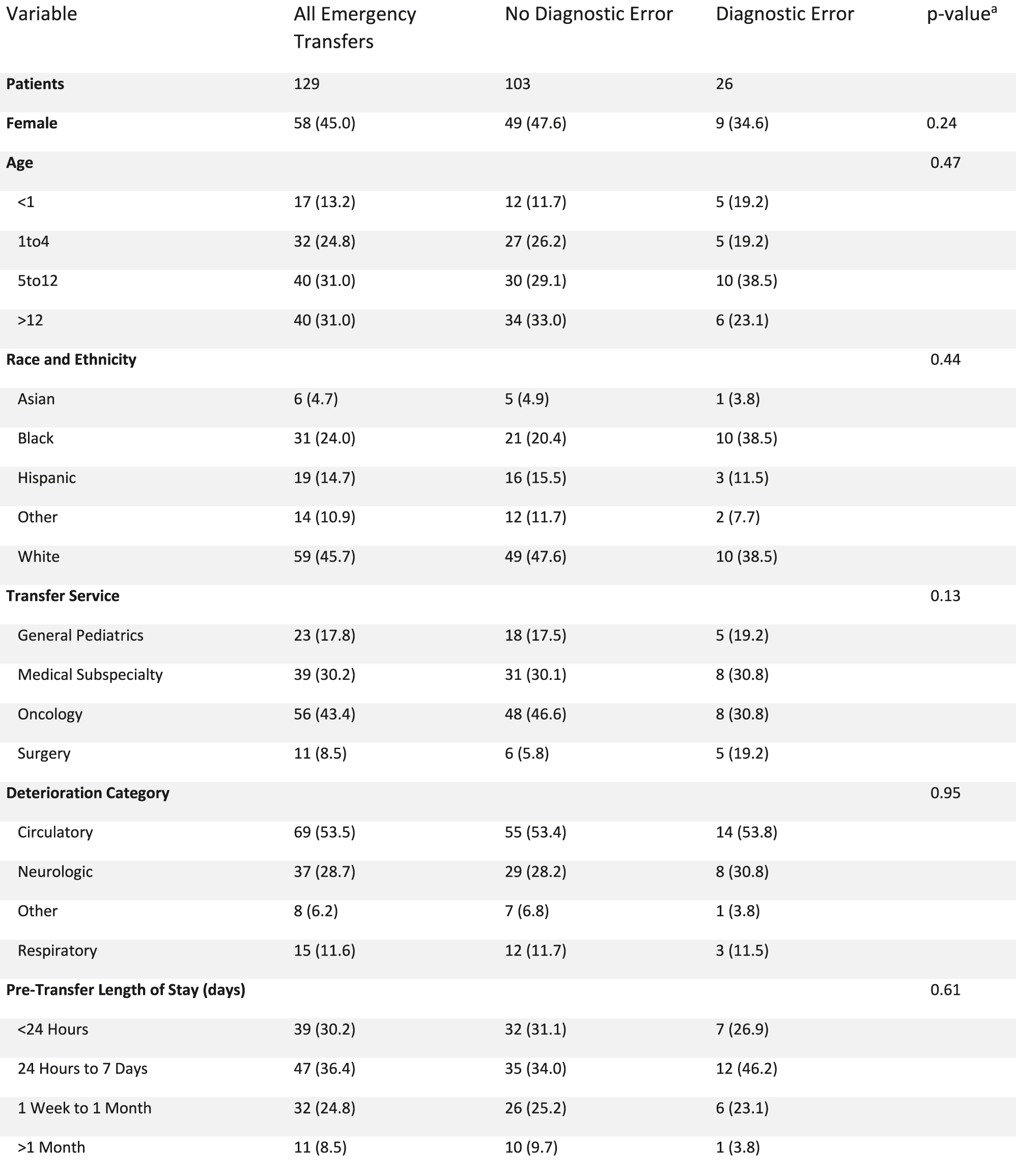

Background: Diagnostic errors, or missed opportunities for improving diagnosis (MOIDs), lead to safety concerns in pediatric emergency departments (EDs). We sought to identify triggers to screen ED records for diagnostic errors. After pilot testing, we applied three electronic triggers (eT) to study frequency and contributory factors of diagnostic errors in pediatric EDs: return visits within 10 days resulting in admission (eT1), care escalation to intensive care unit within 24 hours of ED presentation (eT2), and death within 24 hours of ED visit (eT3).

Methods: We created a standardized electronic query and reporting template for the 3 eTs and applied them to electronic health record systems of 5 pediatric EDs. Using ED visits from 2019, we included a random subset of 400 ED visits for eT1 and all visits for eT2 and eT3 at each site. We trained 2 clinicians from each ED to review the triggered cases. Each reviewer manually screened the chart and initially categorized charts as “unlikely for MOIDs” or “unable to rule out MOIDs”. For the latter category, reviewers performed a detailed chart review using Revised Safer Dx Instrument to categorize as MOIDs or no MOIDs, dichotomized as a score ≥ 5 out of 7 on a Likert scale as suggestive of a MOID.

Results: 2785 ED records met trigger criteria (eT1 1885 (68%), eT2 786 (28%), eT3 114 (4%)), of which 2638 (95%) were categorized as unlikely for MOIDs. The Safer Dx Instrument was applied to 147 (5%) records and 72 (49%) had MOIDs. The proportion of charts with MOIDs ranged from 0.6% to 4.3% across sites. The overall frequency of MOIDs in the triggered charts was 2.6% (72/2785) for the entire cohort, 3.0% (57/1885) for eT1, 1.9% (15/786) for eT2, and 0% (0/114) for eT3. The most common diagnoses associated with MOIDs were pneumonia (10/72) and appendicitis (7/72). 54% (39/72) had patient harm due to MOIDs. Contributing factors were most often able to be assigned to patient-provider factors (36/72), followed by patient factors (16/72), system factors (10/72), and provider factors (8/72).

Conclusions: Electronic triggers with selective record review is an efficient way to screen large numbers of medical records to identify diagnostic errors in pediatric ED visits. Detailed chart review of 5% of charts revealed MOIDs in half, of which half were harmful. Triggers can be an integral part of diagnostic safety measurement systems and can identify cases for additional review, analysis, and improvement.

Emphysematous Pyelonephritis in a Kidney Transplant Recipient: A Diagnosis Not to Miss!

R. Lomanto Silva 1, C. Caglayan1, R. Correa Fabiano Filho1

1University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA

Learning Objectives: Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is a necrotizing infection of the urinary tract with gas formation. This condition affects almost exclusively (90-96%) patients with diabetes mellitus or urinary tract obstruction. EPN carries high mortality thus early recognition is crucial. It can present with vague complaints and develop a fulminant course. We highlight here a rather unusual case of a female with systemic erythematous lupus (SLE) who presented with delusions and non-specific symptoms, making EPN a diagnostic challenge.

Case Information: 41-year-old female with SLE and lupus nephritis post failed kidney transplant on dialysis presented with reports of being assaulted by spirits. Due to a history of mental illness and no signs of physical trauma, she was recommended outpatient psychiatric follow-up. Two days later, she returns to the hospital with chest pressure, anorexia, fatigue, dysuria, and body aches. Initial vital signs and basic laboratory studies were unremarkable. CRP was elevated. Urinalysis (UA) revealed >900 white blood cells, leukocyte esterase, many bacteria. Chest x-ray showed small pleural effusions. Empiric coverage for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) was started. Over the next 48 hours, patient became subfebrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive. Per results of UA, dysuria, and unsatisfying diagnosis of CAP, we pursued CT abdomen/pelvis. CT showed EPN on the transplanted kidney. After transplant nephrectomy and antibiotics, delusions and systemic symptoms resolved.

Discussion: From a death sentence decades ago, in modern medicine mortality due to EPN is decreased with the advent of antibiotics with percutaneous drainage, ureteral stenting, or nephrectomy. A nonspecific presentation leading to delayed radiographic workup has a central role in detrimental outcomes, as EPN’s diagnosis is established with imaging. We wish to underscore the importance of sensitizing providers to the seriousness of this disease, especially considering the literature on EPN on non-diabetic patients without obstructive uropathy is still scarce.

Exploring Diagnosis through Clinical Pathways: A Qualitative Study

Y. Fatemi 1, S. Mamede2, J. Shea3, J. Hart1, A. Costello1, S. Coffin1, K. Shaw4, L. Lieberman1

1Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

2Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

3University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

4University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

Background: Clinical pathways adapt evidence-based recommendations to local settings. They have been shown to improve patient outcomes and reduce resource utilization by decreasing unnecessary admissions, improving time to treatment, and decreasing variations in care. However, it is unknown how physicians integrate clinical guidelines into their diagnostic reasoning and how clinical pathways affect the diagnostic re-evaluation process.

Methods: We conducted a single-center qualitative study involving one-on-one semi-structured interviews of pediatric residents and pediatric hospitalist attendings between August 2021 and March 2022. Recruitment of participants was conducted primarily via email with some targeted recruitment of residents due to initial low response. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. We utilized an inductive thematic analysis strategy to code data and identify themes.

Results: We interviewed a total of 27 physicians: 15 pediatric residents and 12 pediatric hospitalists. Thematic analysis of interview transcripts revealed 4 themes related to physician utilization of and experience with clinical pathways: 1) clinical pathways use as a tool, 2) clinical pathways as a representation of standardization of care in medicine, 3) clinical pathways as a reflection of institutional culture, and 4) the dynamic relationship between clinical pathways and clinician diagnostic process. Within theme 4, the clinician’s experience was integral to choosing a clinical pathway. Additionally, clinical pathways were felt to influence the overall diagnostic process with many participants expressing concern for cognitive biases such as diagnostic momentum leading to missed or delayed diagnoses.

Conclusions: Clinical pathways are an integral component of many healthcare practices and systems. These pathways are also part of a clinician’s diagnostic framework. Pathways are commonly used as a reference and teaching tool, operationalize standardization of care in medicine, reflect local institutional culture, and can influence the diagnostic process. Further research is required to determine optimal clinical pathway design to augment and not impede the diagnostic process. In particular, further exploration of “diagnostic pauses” may address concerns about diagnostic momentum.

Gabapentin Induced Myoclonus

R. Deshpande 1, R. Thirumaran1, T. S. Rajmohan1, N. V. D. Kagita1, A. S. Shaik1

1Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital, Newtown, PA

Learning Objective: Evaluation of gabapentin adverse effects.

Case: A 71-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, and peripheral neuropathy with recent history of urinary tract infection presented with myoclonic jerks of both upper extremities and altered mental status for 6 hours. Her home medications included amlodipine, aspirin, clopidogrel, statin, gabapentin, and acetaminophen. Initial vitals were notable for tachycardia to 110 beats/min, hypotension to 80/60 mm Hg, tachypnea to 24 respirations/min. Labs showed creatinine-5.2 mg/dl, serum potassium-7.5mmol/L, and lactate-3.5 mmol/L. Resuscitation with 30 mL/kg body weight of normal saline was performed and broad-spectrum antibiotics were started. Due to persistent hypotension post-resuscitation, norepinephrine infusion was initiated. Her blood pressure and heart rate improved, but the myoclonic jerks persisted. Thus, gabapentin was withheld. Creatinine improved and the patient’s myoclonic jerks then subsided. She remained symptom free and was discharged with an adjusted dose of gabapentin for her creatinine clearance.

Discussion: Gabapentin is a neurotransmitter structurally similar to GABA, and freely crosses the blood-brain barrier. It has a half-life (t1/2) of 6-7 hours and is renally excreted after approximately 48 hours which is 7-8 half lives. Gabapentin toxicity usually remains asymptomatic but may present with myoclonus as seen in our patient. The exact mechanism, though unknown, is attributed to serotonin involvement. Serum concentrations of >/=15 μg/mL, end stage renal disease, and acute kidney injury are most commonly associated with it. The t½ is prolonged with extended release preparations and in patients with renal impairment, thus requiring dose adjustment based on creatinine clearance. Treatment is mainly supportive, and severe cases may require dialysis. Gabapentin has many off-label uses and hence understanding of its pharmacokinetics, toxicity and dosing in renal failure is important to all clinicians.

God, I could sure use a vodka!

T. Schousek 1

1Vital Innovations LLC, Houlton, WI

The patients subject to diagnostic error included a twenty-nine-year-old female, white, professional electrical engineer, pregnant, and a newborn, male, white, whom shall be referred to as Patient 1 and Patient 2, respectively.

Patient 1 had received routine prenatal care for six months. Patient experienced symptoms of first trimester bleeding that subsided. Symptoms, including visual distortion, lethargy and breathlessness during exertion, intensified in the four weeks prior to the Serious Adverse Event (SAE). Conversation regarding increasing symptoms with scheduling receptionist yielded an appointment six weeks from previous check-up.

At last check-up, a maternal blood triple test was conducted. Patient obtained the triple test results by fax, after intentional delays and thwarted attempts to see the provider. These were motivated by personal anti-abortion beliefs of the provider’s staff. Patient’s sister, a physician, reviewed the test results and indicated the need for an ultrasound to assess validity of the test. Patient 1, unable to get a near-term appointment, sought an ultrasound at an abortion provider who provided a next day appointment. Ultrasound indicated no likely fetal abnormalities. This, however, did not fully explain the positive test results in the odd pattern. No diagnosis was given. These test results were known to indicate problems with the pregnancy, such as preeclampsia and placental abruption. (Cnattingius S, et al., 1997)

Patient 1 presented at a small rural hospital emergency room with vaginal bleeding and pain. Bleeding persisted with patient in tetanic labor. The ob/gyn broke the water during a dilation digital examination. This prompted an emergency, classical c-section and preterm delivery. Ob/gyn ‘nicked’ the newborn badly, leading to a copious amount of blood loss. Pulse rate dropped to 60 bpm and newborn expired.

Ultimate diagnosis was suspected preeclampsia leading to placental abruption. Upon reflection, there were clear signs of preeclampsia that Patient 1 provided to her primary ob/gyn’s staff. The delay in access ultimately led to the death of Patient 2 and the near death of Patient 1.

Other reflections include the observation that:

Provider was unaware of patient’s symptoms and efforts to reach her.

Providers/staff with political agendas may work against the patient’s best interest.

Rural hospitals are ill equipped for any type of uncommon emergency.

Opportunities for learning and research include:

Catastrophic failures are predictable.

Attempts to reach a provider should be logged.

Diagnostic error events are frequently preceded by provider or institution switching.

Cost of Fear “is appalling” (Walton, 1986)

Rarely does diagnostic error exist in a vacuum.

Hypercholesterolemia in Nephrotic Syndrome

R. Deshpande 1, N. V. D. Kagita1, A. U. Kulkarni1, A. S. Shaik1, A. Shah1

1Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital, Newtown, PA

Learning Objective: Evaluation of Hypercholesterolemia

Case: A 21-year-old male with a past medical history of asthma presented for bilateral lower extremity pitting edema and bilateral eyelid swelling. Significant labs were as follows- Cholesterol: 819 mg/dL, LDL: 753 mg/dL, triglycerides: 175 mg/dL, albumin: <1.5 g/dL, proteinuria: >500 mg/dL, and occult hematuria. Nephrology suggested serologies for double-stranded DNA, ANA, PLA-2 antibody complements, and Hepatitis B/C panels which were negative. Cryoglobulin, as well as antibodies for glomerular basement membrane, proteinase, and myeloperoxidase were negative. Renal ultrasound showed bilateral echogenic kidneys with maintained cortical thickness. Other labs included ApoB >240 mg/dL, urine protein/creatinine ratio of 7.13. Protein electrophoresis showed elevated alpha-2 globulins at 35.7% and serum viscosity remained normal at 1.5. Patient was started on atorvastatin for hyperlipidemia, lisinopril for proteinuria and furosemide for pedal edema. Patient improved symptomatically and was discharged to follow up outpatient with renal biopsy showing membranous nephropathy.

Discussion: Nephrotic syndrome is glomerular disease with heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and peripheral edema. Membranous nephropathy (MN) is one of the most common causes which can be secondary to conditions like Hepatitis B/C or systemic lupus erythematosus and primary as seen in our patient which is diagnosed after ruling out secondary causes. Hyperlipidemia in nephrotic syndrome occurs with 87% having >200 mg/dl of cholesterol levels with only 25% having levels >400 mg/dL, which likely is due to upregulation of apoprotein B production secondary to reduced plasma oncotic pressure. Our case is unique because of the marked elevation in cholesterol and LDL. Treatment for MN includes statin therapy and an ACE inhibitor for underlying kidney disease which usually reverses hyperlipidemia. Nephrotic syndrome secondary to membranous nephropathy should be suspected in patients presenting with unduly high lipid panel and edema.

Identifying Diagnostic Opportunities Using Clinical Trajectories: Case Study in Colorectal Cancer

J. Koola 1, D. Laub1, S. Nemati1, R. El-Kareh1

1University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA

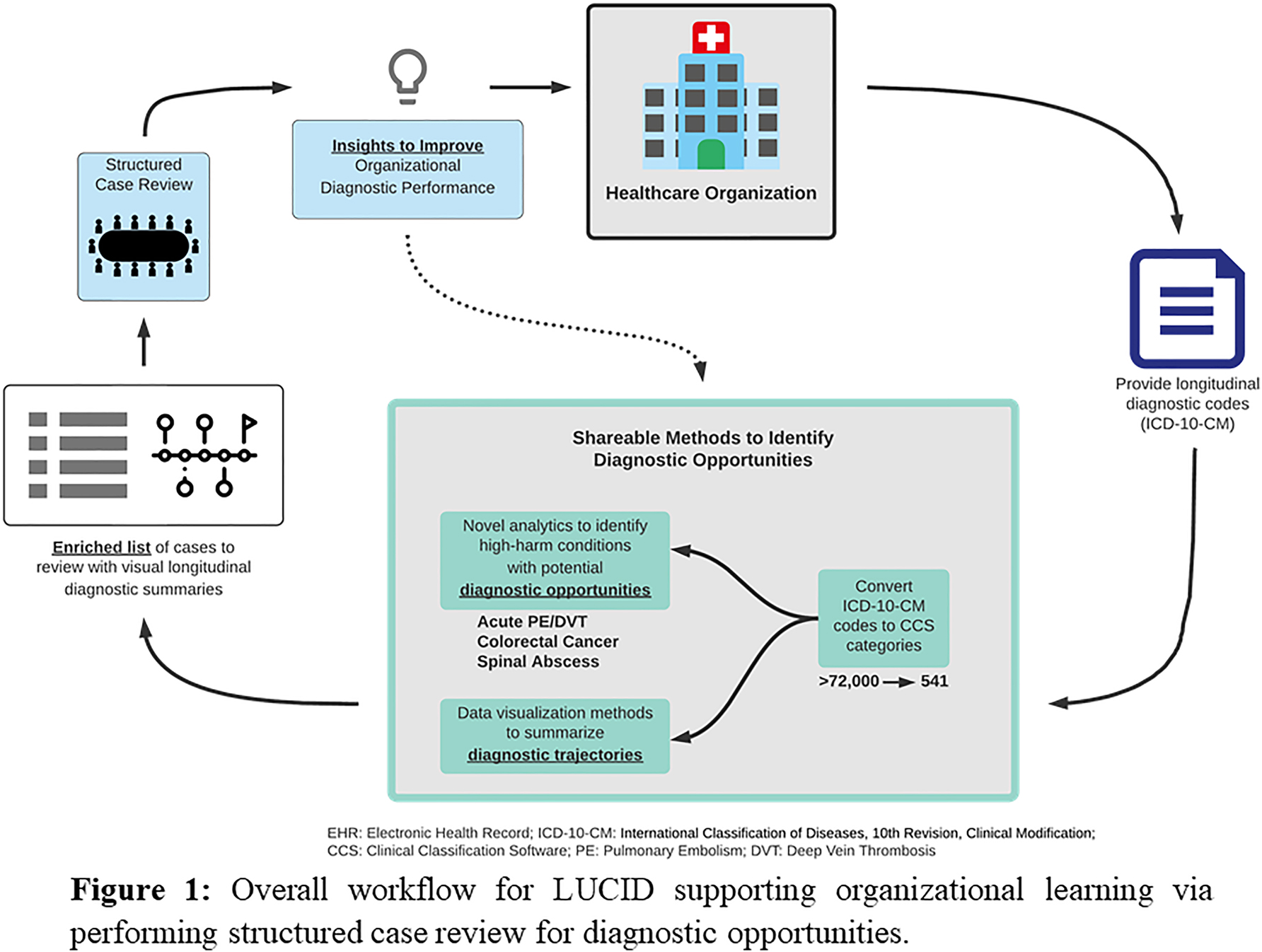

Background: Identifying organizational opportunities to improve diagnostic safety often requires retrospective chart review—a time-intensive process. To support organizational learning from diagnostic opportunities, Longitudinal Analysis of Codes to Identify Diagnostic Opportunities (LUCID) identifies high yield cases for chart review (Figure 1). LUCID summarizes diagnostic trajectories and meaningful transitions prior to the target diagnosis. We hypothesized that these trajectories and transitions provide a signal for diagnostic opportunities.

Methods: We extracted data for adult patients with CRC, defined using International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD10) codes. We created a matched control cohort based on demographics and healthcare utilization. To identify diagnostic transitions, we mapped ICD10 codes to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) categories and identified new CCS categories in the 180-day pre-CRC diagnosis “lookback” period. We constructed a logistic regression model predicting CRC diagnosis with these new categories as predictors and assessed model discrimination and calibration. Using clinical trajectory visualizations and summaries, we performed structured case reviews to identify diagnostic opportunities for a random sample of CRC subjects with a new CCS in the lookback period. We compared presence of diagnostic opportunity to quartiles of predicted probability from the regression model.

Results: We analyzed a cohort of 387 CRC subjects who met inclusion criteria. The logistic regression model had an AUC of 0.74 and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test showed acceptable calibration. Cases had a median predicted CRC probability of 13.4% (IQR:5.6%–48.5%). Of the 27 subjects where we performed chart review to date, 15 (55.6%) had potential diagnostic opportunities. Within the lowest to highest quartiles of predicted CRC probability there were 4/9 (44.4%), 4/5 (80.0%), 4/6 (66.7%), and 3/7 (42.9%) opportunities.

Discussion: Our LUCID system pilot demonstrated feasibility of using longitudinal codes to highlight cases for diagnostic learning. Diagnostic opportunities were common in LUCID-identified cases and the summaries facilitated efficient case review. We are performing additional CRC case reviews to adequately power an analysis between quartiles of predicted probability and diagnostic opportunities. The LUCID workflow is generalizable to any target diagnosis, and our future work will assess its utility for other conditions at risk for diagnosis-related harm.

Implementation of a Novel Electronic Handoff Tool in ICU-to-ward Transitions of Care

E. Fukui 1, E. Harris2, L. Santhosh2, P. G. Lyons3, E. K. McCune2, J. C. Rojas4

1University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA

2University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, San Francisco, CA

3Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

4University of Chicago Medical Center, Chicago, IL

Statement of Problem: The transition of hospitalized patients from the intensive care unit (ICU) to the inpatient ward is a particularly high-risk period due to medical complexity, reduced monitoring, and diagnostic uncertainty. Miscommunication during clinician handoff (e.g., missing or unclear information, ambiguous responsibility for patients) increases the likelihood of medical errors and adverse events (Lyons et al., 2016), as well as cognitive errors such as anchoring bias and premature closure. Although standardized handoff processes are known to reduce medical errors and adverse outcomes (Starmer et al., 2014), these approaches are understudied at the ICU-ward interface, which remains vulnerable to non-standard and suboptimal practices (van Sluisveld et al., 2017).

Description of the Intervention: The ICU-PAUSE is a user-centered, electronic ICU-to-ward transfer tool created using Human-Centered Design methods with focus groups of Internal Medicine residents across three academic medical centers (Santhosh et al., 2022) (Figure 1). It explicitly embeds a diagnostic pause at the time of transfer of care, acknowledging that this is a high-risk period for patients. ICU-PAUSE was piloted in the medical ICU at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, the teaching hospital of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, in 2019 and 2020.

Findings to Date: The ICU-PAUSE offers a structured ICU-ward template to synthesize key information, communicate clinical reasoning, and prevent associated medical errors in the handoff process (Santhosh et al., 2019). Thus far, six of ten participating sites have begun implementation and data analysis, including analysis of equity metrics (e.g., diagnostic uncertainty as it relates to age, sex, race/ethnicity). Post-implementation analysis will evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and adoption of ICU-PAUSE into the physician transfer workflow. We will assess the perceived impact by residents and hospitalists on communication failures and clinical reasoning during transfer.

Lessons Learned: We used Human-Centered Design to co-create a novel standard communication framework for patients transitioning from the ICU to the ward, called ICU-PAUSE, which explicitly embeds a diagnostic pause at transition of care. The inclusion of a diagnostic “pause” in the ICU-PAUSE tool allows explicit acknowledgment and discussion of diagnostic uncertainty to decrease the risk of communication errors and prevent premature closure.

Improvement of Diagnostic Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence-based Differential Diagnosis Lists

A. Hayashi 1, Y. Harada1*, S. Tomiyama1, R. Kawamura1, T. Sakamoto1, T. Shimizu1, M. Yokose1

(*Presenting Author)

1Department of Diagnostic and Generalist Medicine, Dokkyo Medical University, Shimotsuga, Japan

Background: Recently the concept of “collective intelligence” has been expected to improve the accuracy of diagnosis. An Artificial Intelligence (AI) -based automated medical history taking system (AI-AMHTS) collects appropriate information prior to consultation and presents a list of differential diagnoses (DDx), but the diagnostic accuracy of single AI-AMHTS is said to be low. This study aims to clarify whether combining the DDx lists from multiple AIs (collective intelligence of AI) improves diagnostic accuracy.

Methods: We used charts and DDx lists developed by an AI-AMHTS with a DDx generator (system A) from a cohort of 103 patients aged 18 years and older who visited the outpatient department of a community hospital in Japan and were admitted within 30 days from the index outpatient visit between January 1 and December 31, 2020. Two researchers (researchers A and B) read the charts made by system A and inputted items into two commercially available differential diagnosis generators (system B and C, respectively) to develop additional DDx lists without seeing the DDx lists of system A. Other independent researchers assessed whether the correct diagnosis was included in the DDx lists of systems A, B, and C. The primary outcome was the prevalence of cases where the correct diagnosis was included in the DDx lists of AIs (correct diagnosis rates). We used McNemar’s tests to compare the correct diagnosis rates.

Results: A total of 103 cases were included in this study. The baseline correct diagnosis rate of system A was 45.6%. The correct diagnosis rates were improved by using combined DDx lists of the three systems (researcher A, 63.1%, p < 0.001; researcher B, 66.0%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, in 55 cases (53.4%) that one or more same diagnoses were included in each DDx list of the three systems, compared to the correct diagnosis rate of system A (49.1%), the correct diagnosis rates of the combined DDx lists were further improved to 74.5% (researcher A, p=0.01) and 70.9% (researcher B, p=0.001), respectively.

Conclusion: The accuracy of DDx lists of AI-AMHTS can be improved by combining other AI-based DDx generators.

Correct diagnosis rates of each and combined DDx lists of AI-based DDx generators

| Researcher A | p-Value (vs. system A) | Researcher B | p-Value (vs. system A) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| System A | 47/103 (45.6%) | N/A | 47/103 (45.6%) | N/A |

| System B | 40/103 (38.8%) | 0.24 | 44/103 (42.7%) | 0.75 |

| System C | 32/103 (31.1%) | 0.02 | 23/103 (22.3%) | <0.001 |

| At least one system included correct diagnosis | 65/103 (63.1%) | <0.001 | 68/103 (66.0%) | <0.001 |

| At least two systems included correct diagnosis | 38/103 (36.9%) | 0.052 | 33/103 (32.0%) | 0.006 |

| All systems included correct diagnosis | 16/103 (15.5%) | <0.001 | 13/103 (12.6%) | <0.001 |

Inclusion of the PE in SyncoPE

D. Amin 1, A. Vasa1

1Cook County Stroger Hospital, Chicago, IL

Learning Objectives: • Analyze the common but less recognized presentation of a pulmonary embolism. • Describe the pathophysiology of syncope caused by a pulmonary embolism.

Case: 79-year-old female history of coronary artery disease status post stents, diabetes, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obstructive sleep apnea presented to the emergency department (ED) after a witnessed syncopal episode in the lobby of the hospital. On arrival she was neurologically intact and found to be in atrial fibrillation on EKG. VS: 36.3ºC (oral), HR 00, BP 111/58, RR 21, SaO2 88%on 2 liters of oxygen. Exam showed small hematoma to the back of head with non-labored respirations and clear lung sounds. Head CT and chest x-ray were negative. Labs were normal. She continued to be hypoxic while on 2L of oxygen in the ED. A chest CT was pursued the next day and revealed large pulmonary emboli in bilateral main pulmonary arteries with extension to bilateral lobar and subsegmental levels. Patient taken urgently for thrombectomy with interventional cardiology.

Discussion: The diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) is challenging and diagnostic error or delays in diagnosis can lead to death or severe morbidity. Failure to diagnose PE leads to devastating complications, with up to 30% of untreated patients die. Our patient was found to be in atrial fibrillation without being on anticoagulation which was her largest risk factor for PE. The prevalence of PE in patients presenting with syncope to the ED is unknown but investigation should be guided by the patient’s history and physical and risk factors. PE-induced syncope can be explained by three mechanisms. First, occlusion of more than 50% of pulmonary vessels leads to right ventricular failure and left ventricular filling impairment, causing a sudden drop in cardiac output and cerebral blood flow. Second, PE may induce arrhythmias from right ventricular strain. Third, the embolism itself may provoke a vasovagal reflex leading to neurogenic syncope. Early identification is vital to avoid hemodynamic compromise and to optimize survival.

International Classification of Disease (ICD) Code Set for Adverse Drug Event Detection and Quality

T. Adam 1, M. Rafiei2

1University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

2St. Catherine University, St. Paul, MN

Statement of Problem: Adverse drug events (ADEs) lead to injury or death for 1.6 million patients annually in the United States, according to the 2007 Institute of Medicine report, “Preventing Medication Errors”. Adverse drug events can include allergic reactions, untoward medication-specific side effects, or unexpectedly large medication effects resulting in toxicity. ADE identification is a key starting point to investigate ADE causes such as diagnostic error, inappropriate prescribing, and drug-drug interactions.

Description of Program: The ADE program utilized available data sources for retrospective screening of ADEs for quality improvement and research. A previously developed ADE terminology, using ICD9 codes, was reviewed and updated.1 The ICD9-based ADE terminology was mapped to ICD10 using web-based mapping tools, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services general equivalence mapping files, text matching and expert clinical review. The 2015 National Inpatient Sample was used to provide inpatient adverse event data for ADE validation.

Findings to Date: The ICD mapping and ADE validation results are in Table 1. The mapping of the ADE codes is notable for a larger number of ICD codes which are relevant for ADEs with ICD10 codes (533 codes for ICD9 and 1409 codes for ICD10). The relative numbers of ADEs identified with ICD9 codes (Events9) are compared to those identified with ICD10 codes (Events10).

Lessons Learned: The greater granularity of ICD10 yields more ADE-related ICD codes. The number of identified events was relatively lower in some drug categories and higher in others which will require additional evaluation for mapping quality. The ICD10 mapping appears to provide sufficient representation to identify ADEs. Future work will replicate the results in another large clinical data with more recent data.

References: 1. Adam TJ, Wang J. “Adverse Drug Event Ontology: Gap Analysis Clinical Surveillance Application” AMIA Jt Summits Trans Sci Proc.(2015) 16–20.

Measuring Missed Opportunity in Diagnosis in Abnormal Test Result Follow up In Post ED Visit

V. Vaghani 1, U. Mushtaq1, H. Singh2, D. Sittig3, D. Murphy1, U. Mir1, W. Li4

1Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

2Baylor College of Medicine and Houston VA, Houston, TX

3University of Texas School of Biomedical Informatics, Houston, TX

4Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Background: Missed opportunities in diagnosis (MOD) resulting from failures in abnormal test result communication are a significant patient safety concern in outpatient settings and often lead to patient harm and malpractice claims. Electronic health records (EHRs) are used to communicate abnormal test results to providers and to patients and can help to ensure reliable delivery of important clinical information. However, they do not guarantee that this communication results in appropriate follow-up action. In this study, we aimed to measure MODs due to follow-up failures related to three abnormal test results in the post-ED visit setting.

Methods: We developed a new e-trigger using the Safer Dx Trigger Tools Framework. Based on current literature and our prior work on test result communication failures in outpatient primary care settings, we developed an algorithm to detect abnormal urine cultures, blood cultures, and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) test results ordered in treat and release ED visits that had not been followed-up. We excluded patients who were enrolled in hospice or palliative care and terminal cancer patients. One physician served as the primary reviewer for all records, and a second physician-reviewer independently evaluated a random subset of 20% of records to assess the reliability of judgements related to MODs. Prior to the validation chart review, we pilot-tested the chart review process using operational definitions and standardized procedures. Physician-reviewers were trained to use structured electronic data collection instruments to ensure standardized data collection and to minimize data entry errors.

Results: The e-trigger was applied to >9 million patient records, and 105 randomly selected trigger-positive cases, including 35 each of trigger-positive cases for Urine culture, Blood culture, and TSH were identified. Of 100 trigger-positive cases reviewed thus far (Table 1), 52 (52%) cases had MODs, and 48 (48%) had no MODs. Nine (25.7%) of 35 Blood culture, 22 (62.9%) of 35 TSH, and 21 (70.0%) of 30 Urine culture results had MODs. Thus, positive predictive value (PPV) of this e-trigger is 52.0%.

Conclusion: An abnormal test result-based e-trigger using data mining and confirmatory record reviews identified patients with MODs with high PPV. This e-trigger could be used to proactively identify and track patients who need follow-up in order to prevent delays in diagnosis.

Table 1 Baseline Characteristics of Patients in MOD (missed opportunity in diagnosis) and No MOD group

| Overall (n=100) | MOD (n=52) | No MOD (n=48) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 68.9 (15.8) | 70.2 (15.2) | 67.6 (16.4) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 87 (87.0%) | 46 (88.8%) | 41 (85.4%) |

| Female | 13 (13.0%) | 06 (11.5%) | 07 (14.6%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 69 (69.0%) | 38 (73.0%) | 31 (64.5%) |

| African American | 16 (16.0%) | 6 (11.5%) | 10 (20.8%) |

| Native Indians | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Others | 8 (8.0%) | 3 (5.7%) | 5 (10.4%) |

| Decline to answer | 7 (7.0%) | 5 (9.6%) | 2 (4.1%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 07 (7.0%) | 04 (7.6%) | 03 (6.2%) |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 87 (87.0%) | 46 (88.4%) | 41 (85.4%) |

| Other | 06 (6.0%) | 02 (3.8%) | 04 (8.3%) |

| Ordered Test | |||

| Blood culture | 35 (35.0%) | 9 (17.3%) | 26 (54.2%) |

| TSH | 35 (35.0%) | 22 (42.3%) | 13 (27.1%) |

| Urine culture | 30 (30.0%) | 21 (40.4%) | 9 (18.8%) |

Nothing About Us Without Us: Creation of a Family Advisory Board to Drive Diagnostic Equity

A. Mack 1, J. Schaffer1, I. Rasooly1, U. Nawab1, A. Kratchman1, A. Colfer1

1Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

Problem: Engagement with patients and families as collaborators in the diagnostic process has been recognized as a primary driver of diagnostic excellence. Strategies for sustained collaboration with patients/families are needed.

Method: As a part of our institution’s efforts to improve diagnosis and enhance patient safety we established a family advisory panel with the goal of prioritizing involvement of patients and families as we establish best practices for promoting diagnostic excellence. Participants were recruited through our already-established Research Family Partners program, with the goal of recruiting a diverse group of parents who have one or more children currently or previously treated at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Meetings were held virtually on a quarterly basis and scheduled for two-hour sessions in the evenings to allow for participation of people employed during the workday. Participants were compensated monetarily for their time. Initial topics for discussion focused on communication styles between families and hospital staff. Conversations were facilitated by team members. Detailed notes were taken during each meeting to share with the larger group, and to be reflected on in subsequent team meetings in a form of qualitative analysis.

Results: This dedicated family advisory council was developed to reflect the community composition, including disadvantaged populations at risk for disparate care. On average, five parents were able to attend each meeting, with a 6th partner joining our third meeting. Retention, participation. Within these first 3 meetings family advisory council members gave input on best practices to communicate uncertainty with families, discussed patient post-care survey comments that addressed concepts such as feeling dismissed and being left out of their child’s care, and talked through the utility of family access to patient medical records. Record. To date, this endeavor has informed improvement efforts such as working to improve communication of uncertainty in the emergency department, including developing note templates, revamping MD to MD handoff, and brainstorming future PDSA cycles.

Conclusion: Through its first three council sessions, the organizers have received positive feedback from the family partners and the larger diagnostic excellence project alike. This council is enabling us to build improvement initiatives in partnerships with the families, rather than asking for feedback on already established practices. Our experience is that we have found that family advisory councils are a feasible, valuable approach to engaging diverse stakeholders in the diagnostic improvement process.

Patients’ and Clinicians’ Experiences and Views on Safety-netting Advice and its Use in Consultation

R. Fernholm 1, K. Pukk Härenstam1

1Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden

Background: One of the biggest patient safety problems in emergency and primary care is the failure to follow up uncertain diagnoses, with the risk of leading to preventable diagnostic harm. A promising approach is to use safety-netting, which has received increased attention in recent years. However, there is still limited knowledge about how to successfully apply safety-netting strategies in practice and few studies have accounted for patient experiences in this area. Objective: To explore clinicians’ and patients’ experiences of diagnostic uncertainty and their ideas/views on how safety-netting can be successfully applied in primary and emergency care settings.

Method: The study was performed in a Swedish setting. An exploratory research design was used, based on six interviews and two focus group discussions, involving a total of nine clinicians working in primary and emergency care, as well as seven patients and one family caregiver with experiences of diagnostic uncertainty. Data were analyzed inductively, using the framework method. The COREQ guidelines for reporting qualitative research were used.

Results: To manage diagnostic uncertainty, clinicians and patients emphasized the need to understand preconditions for the consultation (i.e., the patient’s capacity and their social context; aspects influencing the patient-clinician collaboration; the healthcare context) and gain shared situational awareness regarding the patient’s perspective and experiences, as well as the need for safety-netting. We identified six strategies for successfully applying safety-netting: 1) openness about uncertainties; 2) communicating expected course of events; 3) tailoring information; 4) using multiple modalities; 5) teach-back; 6) facilitate re-consultation.

Conclusions: The understanding of preconditions for the clinical encounter and the establishment of shared situational awareness between the clinician and the patient were identified as vital aspects for the successful selection, tailoring, and application of safety-netting strategies. Implications for practice can be that safety-netting can be systematically built in the consultation technique taking these aspects in consideration.

Physics in Medicine: Pedagogical Reforms Focused on More Effective, Accurate and Expedient Diagnoses

E. Szuszczewicz 1

1George Mason University, Haymarket, VA

Learning modules are under design and development with innovations providing more effective diagnoses, treatments, and cures for everything from cardiovascular and neurological diseases to cancer. The focus is on physics as the foundational science of all life sciences, with the Physics in Medicine (PIM) program designed to educate students of medicine, and the medical and physics teaching and research communities, on the needs-for and applications-of a first-principles cause-effect understanding of life science and medical care processes. The effort is in response to mandates from numerous panels that have raised concerns about the basic science content in medical education and have advocated for reform in curricular and competency requirements. These critical needs are manifested in data pointing to 40,000-80,000 deaths/year resulting from misdiagnoses. Learning modules are concentrated on six major medical themes, with the most fundamental theme considered to be “Neuroscience, Electrodynamics and Cellular Biology - The Mind and the Brain - The Pathways to Cognition, Sensory Perception and Bio-Feedback”. It is considered most fundamental, with electrodynamics at the core of all human functionality. And the theme is being built on learning modules starting with single-cell electrodynamics, working into biological system and subsystem applications. To meet the challenges of educational structures, student workloads, and mandated reforms, PIM has a team of practitioners, academicians and researchers from the medical and physics communities that focuses not only on content but on approach, and on the development of quantitative predictive skills and adaptive thinking capabilities that transcend the current algorithm-based diagnostic protocols of medicine’s evidence-based training. The underlying strategy involves not just an accumulation of facts and the study of the laws of physics, but the development of an inquiring scientific mind and a method of cause-effect inquiry, thinking, and problem solving based on first-principles analysis. In the end, the students will be far better prepared to meet the challenges to their understanding and use of ever-advancing technologies, and the intellectual demands of causal processes and ever-expanding databases dealing with disease onset, progression and controls. Indeed, the onset of all diseases, their progression and their in vivo controls are traceable to the attributes of cell and tissue properties controlled by atomic and molecular physics and an arsenal of electrical, kinetic, thermodynamic, fluidic and gradient-driven forces. Early-stage testing of PIM concepts within pre-medical, grand-rounds, residency, and critical-care venues has reinforced its goals, approach and developing curricular deliverables.

Physics in the Medical School Curriculum: Foundational Science Content to Support Medical Diagnosis

L. LaConte 1, B. Roth2, N. Donaldson3, E. Szuszczewicz4, E. Redish5

1Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, VA

2Oakland University, Rochester, MI

3Rockhurst University, Kansas City, MO

4George Mason University, Haymarket, VA

5University of Maryland, College Park, MD