Abstract

In this article, the focus is on the pivotal role of speakers in shaping language dynamics and dialectal stability, particularly within the context of dialectal variation. It is evident that language is intricately tied to human experience, serving as a tool for navigation, problem-solving, and social interaction. This article posits that understanding the interplay between language dynamics and stability of dialects requires a nuanced consideration of speakers and their practical relationships with the world as well as their linguistic mental representations. People are not passive recipients of language; rather, they actively engage with it in various contexts, adapting to new situations and influencing linguistic change. Through empirical examples from German dialectology, the article illustrates how speakers’ interactions with their environment shape language evolution. Overall, the article aims to provide insight into the role of speakers in driving linguistic change and maintaining linguistic conventions within dialectal contexts. By examining the practical relationships between speakers and their environment, it contributes to the development of a comprehensive framework for understanding the complexities of language variation and evolution considering linguistic representations.

1 Speaker, language, and the world: problem outline

The speakers of a language use a symbol system for the purpose of communication which also includes receptive processes of hearing and seeing, were not considered by linguistics for a long time and their way of using language was even regarded as faulty or obstructive (e.g., in Chomsky’s Generative Grammar). However, if we look at the worlds in which we all live, we notice that language is always linked to people. People use language to find their way in their environments, to orient themselves and to solve problems that they face in the world. They are undoubtedly competent speakers of their L1, but the importance of performance, which Chomsky has ignored due to an alleged inadequacy, cannot be denied phenomenologically. The pragmatic turn has led to the assumption that language cannot be adequately described without examining its use. Because people use their language to constantly adapt to new situations, however, for communication to be possible at all, a certain structural stability is also necessary. This connection between dynamics and stability as a basic anthropological and linguistic pattern is the subject of this article. It’s argued that regional variation is a central object of speakers’ language reflection (cf. Hoffmeister 2021a; 2021b). This article poses the question of how the dynamics and stability of dialects can be explained by taking into account the role of speakers (cf. Nilsson 2015; Sharma 2005), in other words: how must speakers be modelled in order to do justice to their influence on change (dynamics) on the one hand and on conventionalizations and schematizations on the other (stability)?

As speakers, people are not simply mechanical organisms in physical spaces; people live, think, act, have ideologies, attitudes, knowledge, they influence their world, strive for change, reflect, question, doubt, interact and communicate, and so on. Language plays a more or less important role in all these aspects. Without language, human life and the cohabitation in its human-historical form would be inconceivable. This is why people have an influence on changes in language: this happens either through emergence processes that ensure that new language norms arise from language use or through direct negotiations, for example in social media (cf. Hoffmeister forth.).

The article is based on the following thesis: Diachronic language change as well as the current language structure and the connection between dynamics and stability can only be adequately explained if speakers are considered as speakers in their practical relationships, i.e. the way in which the world, with all its impressions and situations, affects people and how people react to it: e.g. rainfall causes me to put on a raincoat or open an umbrella (cf. Chomsky 1983: 8) (“What shitty weather, but the farmers are happy”); the sunshine causes me to put on sunglasses; the barking dog (“So ein Kläffer [What a barker]”) causes me to change sides of the road; I pave the driveway so that I can get to the front door with dry feet, etc. The overall long-term goal is to develop an empirically based, anthropologically plausible, and representational theory of language. This article discusses initial approaches to achieve this goal.

I begin the paper by examining various approaches to linguistic representation (Section 2) and discuss remaining desiderata. To model the role of speakers regarding the dynamics and stability of dialects in detail, the position of speakers in the world and their relationship to it must be analyzed (Section 3.1). Because speakers are the central instances for shaping linguistic change – it is crucial how they react to the situations of the world and thereby make them their own. The second aspect of the representational approach is understanding the speakers who are modeled as affectively involved (affektiv betroffen) by language (Section 3.2). The translation of Hermann Schmitz’ concept “affektives Betroffensein” from German to English is quite difficult. I am using here two alternatives: (1) to be affectively involved and (2) to be affected by language. This is followed by the recognize-and-understanding-as-relation (Section 3.3), the last aspect of a representational approach introduced here. The fact that this approach cannot be presented here in extenso is due to the limited scope of this paper. However, the three aspects picked out here are central anchors and starting points. The theoretical aspects presented in section 3 are empirically substantiated in section 4 using two examples from German dialectology, so that a concrete picture of the role of the speakers emerges.

2 (Linguistic) representations – an introduction

Linguistic representations are a lively subject of research, particularly in neuro- and psycholinguistics. However, the concept of representation is also used in (cognitive) grammar research to explain the development of language structures and language use. A rather diffuse picture emerges, particularly regarding the definition of the term linguistic representation. While in neurolinguistics a neural, electrophysical stimulation in the brain is already considered a representation, it is not quite so easy for other research disciplines to find an operational definition (on the methodological link between neurolinguistics and dialectology cf. Schmidt 2016). There are also enactivist theories that pursue the idea of radical embodiment and reject the existence or necessity of representations altogether. Weiskopf (2010) discusses a range of literature on this topic and argues comprehensibly why these approaches are not conclusive in their radicalism.

Overall, it can be stated that at least the few contributions which deal with linguistic representations explicitly position themselves according to what exactly they understand by representation. Operational definitions are mostly rare. The texts by Egan (2012), Scheerer et al. (n.d.) and Pitt (2020), among others, provide good overviews of philosophical traditions (especially regarding analytical approaches) – but they will not be discussed here in depth. The problem is when we talk about linguistic representation, we often mean mental linguistic representations. This is because linguistic signs of mediality also represent meaning. For example, morphemes, articulatory-segmental units or phonemes (grapheme), and systemic contexts. Diagrams also represent meaning (cf. Krämer 2014; 2016). They are external types of representations (cf. also Grabarczyk 2021: 338 f.) on this ontological difference). The connection between grapheme and phoneme is epistemologically profound and can be traced back to the connection between showing and saying, which has far-reaching consequences (keyword: imagery or iconicity), which cannot be explained here. I therefore refer to Krämer (2010; 2020). When I refer to linguistic representations, I mean – unless otherwise noted – mental linguistic representations (for a different approach cf. Cohen, Sasaki & German 2015). The question of what linguistic representations are is left unsolved. Grabarczyk (2021) proposes an alternative to this question and asks what can be ‘used’ or ‘utilized’ as a representation. His view of representations is thus a functional one, although by distinguishing between “use” (in the sense of token) and “usage” (in the sense of type), following the work of Pelc (1971), he subscribes to a structuralism (cf. also O’Brien & Opie 2004) that is difficult to deal with theoretically – if one takes speaker seriously as the most important instance of a representational theory. Before developing my own representational approach, I will take a brief, cursory and exploratory look at the literature – but I will not provide a systematic literature review.

Linguistic representations became an important theoretical subject, particularly in Noam Chomsky’s Generative Grammar (cf. Chomsky 1981):

I will use the term ‘generative grammar’ or simply ‘grammar’ to refer to the system of rules and principles that constitutes a person’s knowledge of language and that forms the various mental representations that enter into the use and understanding of language. (Chomsky 1983: 10).

Chomsky fundamentally assumes a nativist understanding of language, according to which not only the basic ability to learn language, but also universal language structures are innate and stored in the brain. Chomsky’s approach is therefore also psychologistic – it is based on Cartesianism (cf. Chomsky 1983). Even if no comprehensive concept of linguistic representation is explicated, Chomsky (1981: 11) speaks of “mental structures”, a “physical mechanism” (Chomsky 1981: 13). or a “belief” (Chomsky 1983: 8). The concept represents a central building block in his theory (cf. Fanselow & Felix 1984). Chomsky thus ascribes an ontological status to representations. In his understanding of language theory, human language ability (competence) is innate and human language knowledge is organized in modules. There is a specific area (module) in the brain that is responsible for processing syntax, another for semantics and yet another for phonology. These areas each provide their own aspect, from which the performance of language, the linguistic surface structure, is formed. For this to be possible, humans possess the evolutionarily given Language Acquisition Device (LAD), which is responsible for the fact that we have language; language “simply developed in our minds due to our internal equipment and the environment” (Chomsky 1981: 18). Accordingly, the mind is also a “fixed biological system with intrinsic scope and limitation” (Chomsky 1981: 14). Research into Chomsky’s concept of language is now very extensive. For this reason, his approach will only be presented briefly here. In summary, the following can be stated:

The subject of a linguistic theory is first and foremost an ideal speaker-hearer who lives in a completely homogeneous language community, knows his language perfectly well and is not affected by the application of his knowledge of language in actual speech. (Chomsky 1981: 32)

Chomsky states that he was surprised by the criticism that this statement provoked. This article is yet another article that criticizes this view, since it is precisely the fact of being affected that is made the subject of linguistic modeling (cf. Section 3).

When Chomsky speaks of representations as physical mechanisms, Adger (2022: 249) argues that the generative units are not representations; rather, the generativists used the term representation “as a technical monadic term” (Adger 2022: 250), i.e., a semantic expression that cannot be further dissected and that has both physical and mental meaning. Representations thus represent a basic unit of the mental. Adger’s main point of criticism, however, concerns the relationship to the world, which is examined in particular by studies on mental (linguistic) representations that deal with language, space, landscape and sociality (cf. Preston 1989; Purves, et al. 2023; Striedl 2022; see also Section 3). Chomsky (2000: 159–161) assumes a non-relational concept of representation that excludes the world as a reference instance and, according to Adger, denies the representation of metaphysical objects. Overall, generative psychologism is to be criticized as psychologistic reductionism because it understands all operations as mental processes and the monadic structure leads to attributing a physiological reality with psychological necessity to scientific constructs that explain linguistic phenomena (e.g., language change) (cf. also Kasper & Hoffmeister in prep. (an english version of this article can be accessed through this ▶ link (see References).

Finally, Chomsky’s approach also ignores the intentionality of representations, as described in Rey (2020), following Brentano’s (1874) concept. If representations have no physiological equivalent in the brain, what status do they have? Representations are abstractions of hypothetical, physiological elements of the brain (cf. Adger 2022: 249) and thus scientific constructs (cf. Kasper & Hoffmeister in prep.). Yet if representations are supposed to be scientific constructs as abstractions of neuronal processes, how should we deal with neuro- and psycholinguistic results? It was stated above that representations play a central role in neuro- and psycholinguistic research. However, the results of EEG experiments (e.g., early brain responses such as N400 or N600 etc.) are not themselves representations. As an electrophysical impulse, they indicate processing procedures, which in turn are the prerequisite for the assumption of representations as constructs that are necessary for understanding or explaining these processes and the significance of these processes for humans. “They [the representations] are the best explanations of the phenomena, though we do not know exactly what they correspond to in the world we can currently observe” (Adger 2022: 250). We would like to add something to Adger’s statement – because ultimately – we cannot assume that representations correspond to anything observable at all. What we can assume, however, is that they help us as an explanatory tool to explain the relationship between humans (speakers) and the (linguistic) world. This means that there is no reified concept of linguistic representations (cf. also Zahnoun 2020):

[R]epresentation should be understood as referring to a complex cognitive and socio-normative phenomenon which involves, besides certain personal cognitive capacities and socio-normative practices, physical things. But it is a mistake to therefore think that representation is itself a physical thing. (Zahnoun 2020: 95)

If one feature of representations is intentional i.e., ‘directed’ towards an object, then representations must have a meaning because, because of being directed towards something, they realize (vergegenwärtigen) these objects abstract features. What has not been clarified here, however, is how representations acquire their meaning in the first place; “to parse our constantly unfolding experience into meaningful representations” (Ünal, Ji & Papafragou 2021: 224). They conclude “that the cognitive representation of events is sensitive to aspects of events necessary for linguistic encoding” (Ünal, Ji & Papafragou 2021: 234).

This is developed theoretically in the context of Kasper’s (2015; 2020) Instruction Grammar, which is based on a comprehensive concept of meaningfulness (Bedeutsamkeit) (cf. also Grabarczyk 2021 on a functional theory of representation and Anderson & Rosenberg (2008) on the guidance theory of representation). In addition, Ünal, Ji & Papafragou (2021: 234) show “that a relative salience of certain aspects of events varies in similar ways across language and cognition”. This situational variability will be taken up again and discussed in more detail later (especially in Section 4). Mondal (2022; 2023) provides a different approach. He argues that linguistic meaning – and thus ultimately the representation of it – arises from an interplay of more general embodied cognitive representations on the one hand and formal-mathematical structures on the other. What is not resolved and instead, presupposed, is that these more general embodied cognitive representations themselves already have a meaning. Mondal is also unable to explain how this arises. Rather, it seems that he introduces a structuralist concept of representation ‘through the back door’, as he distinguishes between cognitive/conceptual representations and formal/logical representations (Mondal 2022) – this is reminiscent of the type-token distinction and Saussure’s concept of signs.

If Adger (2021: 258) denies that generativism and its understanding of representations represents anything at all, since it lacks intentionality, we can now ask with Bjerva et al. (2019): What Do Language Representations Really Represent? The authors conclude that “genetic, geographical, and structural distances” are represented, but fail to explain in detail the concept of representation. Instead, they understand representation from a computational linguistic perspective for “a real-valued vector […] which can be used to measure similarities between languages” (Bjerva et al. 2019: 382). In doing so, they reveal a fundamental problem of many works that operate with the term representation: Although these works use the term (cf. e.g. Barsalou 1992; Langacker 1999), they hardly operationalize it and certainly do not substantiate it within the framework of a consistent theory (cf. e.g. also the experimental approaches of Branigan & Pickering 2017; de Smet 2016; Tachihara & Goldberg 2019). This leads to a diffuse use of the term, so that individual works are hardly comparable with each other. Lakoff & Johnson (1999: 257–258) even speak of a “representation metaphor”.

Although a fully detailed theory is beyond the scope of this paper, the challenges to a concept of linguistic representation formulated in Kasper & Hoffmeister (in prep.) will be followed by initial approaches and starting points for such a theory. On the one hand, this considers the experience of people, which functions as an influencing factor on the perception and representation of dialectal variants (cf. Sumner & Samuel 2009), and on the other hand it considers the relationship of the speakers to their lifeworlds (cf. Malt 2024). These theoretical approaches are then empirically substantiated in section 4 using two examples from the dialectology of German, because “one cannot determinately posit a particular model of mental representation without evidence beyond introspection” (Croft 1998: 151). The descriptions and interrelationships in this section have shown that in the context of representations, the investigation and modeling of humans as ecological, perceptive, acting (cf. Tomasello 2022), affective and cognitive beings and thus as the entity to which we would attribute representations is missing (cf. for example Ramsey 2007; Rey 2020; Shea 2018). In other words, the human being is the site of investigation of mental representations. We must therefore place them at the center of our considerations, echoing the empirical challenge of “evidence beyond introspection” mentioned by Croft. The following section aims to present the first starting points for a theory of linguistic representations in practical contexts (in vivo), starting from the human being as a human being.

3 Starting points for a model of linguistic representation to explain dialect dynamics and stability

Based on the desiderata of a consistent theory of linguistic representations derived in Section 2, three starting points of such a theory will now be outlined, which place the human being at the center of consideration. To move from a general theory of representation to a theory of linguistic representations, the human being is reflected upon in his role as speaker. Speaker refers to an individual’s ability to use complex symbol systems of any mediality for the purpose of communication and to understand them. With the help of these symbol systems, people create references. The necessary prerequisite for this ability is mental performance, which in turn itself serves as a symbolic and thus culturally mediated function (cf. Schwemmer 1997: 11). Therefore, the human being must be described against the background of these mental achievements to be understood. However, since the human being is not an isolated machine fed by stimuli and reactions, but – as described above – an ecological, perceptive, active and affective being, all these dimensions must also be considered. The first starting point is therefore to model the relationship between humans with cognitive abilities, the ability to act, etc. and their environment and lifeworlds.

3.1 Presence – Presentation – Representation

Humans are in the world; they are ‘there’ (cf. Wiesing 2020: 108). Through my body, I am bound to a specific, fundamentally variable place in the world (cf. Wiesing 2020: 108). Through existence we are ‘integrated into the flow of changing environments and situations’ (Schwemmer 1997: 25). This is accompanied by a diversity and dynamism of experiences; we are present. This presence arises because we are in an input-output relation (more concise: impression-expression relation) with the world. Contact with situations and their variability (cf. Ünal, Ji & Papafragou 2021: 234) leads to positioning because they involve us affectively (cf. Section 3.2). For us to be present, certain cognitive abilities, including symbolic and cultural functions, are necessary. We find ourselves in manifold situations and recognize an event as affecting us (cf. Section 3.3). Recognition takes place via differentiation (cf. Westerkamp 2020: 18–21), via the separation of a foreground from a background (trajector-landmark). The perceived objects and aspects thus become meaningful (‘bedeutsam’) (cf. Schwemmer 1997: 105). An abstraction takes place via making a difference, which leads to our presence, in which we are exposed to concise features (prägnante Merkmale). As a result, only certain aspects or features are present to us, while others are faded out and in the background. The dynamics of experience as the triggering moment of presence controls this perspectivity. This presentation of objects is therefore different from the ontological appearance of the objects themselves (cf. Schwemmer 1997: 67). This shows that not only are we as human beings present in the world – at least if the conditions of presence just described apply – but that the world presents itself with its impressions and situations, which are absorbed and processed by the present human being. For example, the reflection of the setting sun on the mirror-smooth Baltic Sea, the smell of freshly mown grass that pervades the new housing estate on a Saturday afternoon, another traffic jam on the main traffic route at the end of the day, the slowly opening early bloomers, the praise of a loved one for my new dish I have finally cooked, etc. For the development of representations, impressions in quantity and especially in quality are central, as empirical studies show (e.g., Leybaert 1998). We need representations as visualizations of these objects of the world and their situations and moments in order to develop a ‘situation-invariant identity’ and to be able to react to other objects and future situations in an adequate and resource-saving, i.e. routinized, way (cf. Schwemmer 1997: 78). For example, by letting the sun shine on our face or taking a photo, by remembering that we also have to mow the lawn, by tuning into a radio channel that relaxes us when we get stuck in a traffic jam, by buying a bunch of tulips from the florist for the dining table, by being very happy about the praise and adding the dish to our recipe book. The world impresses itself, the person expresses himself.

This is the fundamental context of symbolic interaction. It is in this context not the interaction of two individuals with symbols (communication), but more fundamentally with goal-oriented actions (including attitudes, ideologies, motives, etc.) as the results of being confronted with such situations and objects which is the foundation. In its impressions, the world presents us with problems and tasks whose solution is not only our responsibility, but an absolute necessity. The problems include basic phylogenetic needs such as obtaining food and protection from environmental influences such as cold and heat, but also cultural evolutionary ones such as crossing a road safely, finding a way, forming, and maintaining social communities and much more. The basis of any solution to these problems is cognitive performance, including first recognizing that there is a problem to solve (cf. Section 3.3) and then planning and executing actions. Representations are formed so that this can be done without the actual situatedness and thus in a situation-invariant and routinized manner and with reduced cognitive effort. The basic function of our mental abilities lies in their applicability. Representations function as visualizations of the environment that enable people to coordinate actions aimed at the environment, even when the environment is not present (cf. also Grabarczyk 2021: 339). From this characterization, Grabarczyk derives two theses that must apply to such representations. The first thesis follows logically from the input-output relation:

3.1.1 Synchronization thesis: Mental representations and the external world must (be able to) be synchronized with each other (cf. Grabarczyk 2021: 340)

Two different concepts of synchronization are used in this article. The first refers to synchronization in the sense of an exchange and an alignment between the individual and the world (synchronization thesis). However, the concept of synchronization used below (Section 4.2) according to Schmidt & Herrgen (2011: 28) is more interactional and refers to the “alignment of competence differences in the act of performance with the consequence of stabilization and/or modification of the active and passive competences involved”. This second concept of synchronization refers to the alignment between at least two individuals.

In the first understanding of synchronization, however, a receptor problem arises (cf. Grabarczyk 2021: 340). If one considers representations as synchronized with the world, one might think that representations are a particular or special form of receptors that are directly involved in perceptual processes. However, Kasper & Hoffmeister (in prep.) show in detail why this conclusion is incorrect and why representations should rather be understood as mediators between impressions and expressions. The thesis of synchronization is thus to be understood as follows: The external world is perceived and sensed via the human perceptual apparatus in a mnemonic circuit. This connection between humans and the world leads to the establishment of a resonance relationship (cf. Rosa 2023), which, in turn, leads to representations that can be attributed a synchronized status. Synchronization here means, not in the strictly time-philosophical sense of the term, a parallelization; an exchange of characteristics and thus describes the process side of representation, which can be understood as both a product and a process due to a terminological vagueness.

Due to the parallelization and the exchange of features, thesis (2) follows logically from thesis (1):

3.1.2 Thesis of isomorphism: There is a structural similarity between mental representations and the external world (cf. Grabarczyk 2021: 340)

Thesis (2) means that a person’s connection to world events occurs when the person participates in these events as a participant and influences them in a formative way or is fundamentally able to do so (cf. Wei & Knoeferle 2023). Grabarczyk (2021) understands representations in this context as s-representations and, following Cummins (1989; 1991), refers to simulation representations and, following Swoyers (1991), to structural representations. Basically, “the essential characteristic of s-representations is that not only do they stand for their targets […] but they are structurally similar to these targets” (Grabarczyk 2021: 341). Nevertheless, the question is what exactly is meant by “structurally similar”. This isomorphic relationship between mental representations and the world is based on shared features that are integrated into the mental representations as abstractions from the world by means of the perception of impressions. For this to be possible, the world features must become concise in the circle of memory, i.e., they must be detached from the permanent stream of experience (see above and Kasper & Hoffmeister in prep.).

If an isomorphic relation is established via synchronization (thesis 1) and the world object is lost for some reason (e.g., because a certain linguistic variant is no longer part of language use), then this also has an influence on the underlying representation, because the mapping may fail (forgetting). This can lead to misrepresentations. A representation that has lost its target object in this way becomes a new, independent mental representation because of a previous synchronization process (remembering) and can be used either successfully or unsuccessfully (cf. Grabarczyk 2021: 348).

It is already clear in this brief description, which certainly still leaves central questions unanswered, that the understanding of representation presented here differs from the traditional approaches of Fodor and Pylyshyn and the amodal-propositional theory of representations (cf. most recently Quilty-Dunn, Porot & Mandelbaum 2023), particularly through the contextualization via presence and presentation. Instead, a form of a modal theory of representations is developed that is based on groundedness, embodiment, situatedness, among other things (cf. also Spivey & Huette 2016). An important core of this concept of representation is a suitable speaker model. Therefore, as one aspect of such a speaker model, the speaker is described below, following Hermann Schmitz, as affectively involved by language (von Sprache affektiv betroffen).

3.2 The Human Being as affectively involved by Language

In Hermann Schmitz’s New Phenomenology, humans are considered to be fundamentally affectively involved. I cannot and do not want to go into this fundamental affectedness in depth here, but rather show why we should understand people as affectively involved by language. This enables us to gain a deeper understanding of the impression relation in the circle of memory described in Section 3.1.

Being affectively involved by language is a direct consequence of a person’s presence in the world; it refers to the fact that someone is affected by something and is haunted by it, to quote Schmitz:

Someone is affectively involved by something when they are so affected by it that they cannot help but feel themselves and in this sense become aware of themselves, even if they do not think about it at all, do not reflect on it at all, but are completely naive like an animal or an infant. (Schmitz 2019: 13)

People are therefore present in the world and are confronted with a variety of impressions in their stream of experience. These impressions are worldly, i.e., components of the world, and they can be both linguistic and non-linguistic. Here and in the following, I will focus in particular on linguistic impressions. These impressions have an affecting quality, that is they can captivate the listener or reader in such a way that he or she feels emotions (joy at a word that has not been heard for a long time, astonishment at a word that has never been heard before, anger at a supposed linguistic fashion, etc.). Affective involvement is thus the primary relationship between the subject and the world. The connection to speech acts is obvious here. As a decisive bodily state, affective involvement is a necessary condition for the choice of action and thus both for the action itself and for refraining from it:

Our imaginative life, and this includes the processes of association, categorization and schematization, is fundamentally shaped by our own bodily exploration of our environment. Our imaginative life is action-shaped, and our actions are bodily. (Kasper 2020: 259)

Because affective involvement is “primarily and originally bodily, a bodily impulse” (Schmitz 2014: 37), it is initially impossible to distance ourseves from it. As a ‘bodily impulse’, it is an element of human dynamics. So that we do not get lost in all the situations or in the continuous stream of experiences in which impressions confront us and which trigger affective involvement, and so that the diffuseness can be transformed into an order, structuring elements are created through association, categorization, and schematization (synchronization thesis, Section 3.1), which have a similarity to the impressions (isomorphism thesis). These structuring elements are mental representations. Mental (linguistic) representations are facts of affective involvement and “the facts of affective involvement [are] subjective facts […] which in their mere factuality, apart from their content, bear the stamp of ‘myness’” (Schmitz 2014: 31). This ‘myness’ arises from the situatedness of the human being in the primitive present. This primitive present consists of these five moments: (I) I (the own/foreign), (II) here (space), (III) now (time), (IV) being (Sein/Nicht-Sein), (V) this (relative identity). Even if Schmitz (2014: 55) places the I in the last and final position, it is so central, especially in the context of affective involvement, and also so relevant for the linguistic considerations of the human being as speaker, that I would like to place it here at the beginning when I show how these five moments of primitive presence are effective in the concrete situation of being confronted with a new linguistic variant. The I (I) as the moment of the “consciousness-holder entangled in the [subjective] facts of affective concern” (Schmitz 2014: 61) is confronted with something new, challenged, stimulated to cope, shaken, burdened; here, concepts of salience and pertinence become central (cf. Purschke 2011: 2014; Kasper 2015: 2020; Kasper & Purschke 2023). For example, say I hear a new variant that I have not come across before, e.g. the lexical variants in low german Feudel for Wischtuch [wiping cloth] or Trecker for Traktor [tractor] or the prosodic elongation at a phrase boundary (as in [Es hört gleich auf zu schneien]IP [dann wird das Wetter wieder besser]IP, english: [It’s about to stop snowing]IP [then the weather will get better again]IP, for this phenomenon of pre-boundary lengthening, cf. Spina & Lameli in prep.). The present is meaningful (bedeutsam) for this person (cf. Kasper 2020). All aspects of this meaningfulness are subjective, i.e., related to a person.

If all or some of these aspects are called into question and contrasted with other aspects, for example, if something new or different arises, something that is foreign also arises (cf. Schmitz 2014: 101). For example, imagine that I always use the standard linguistic expressions Wischtuch [wiping cloth] or Traktor [tractor] and am now hearing the regional variants Feudel or Trecker for the first time. This newness, as something (initially) foreign, has the potential to involve us affectively (e.g., rejection because of incomprehension or positive reactions because it triggers curiosity) and will subsequently constitute a “sphere of one’s own” (Schmitz 2014: 61) as a kind of lifeworld contrapunctus. What was previously normal is only now recognized as a variant alongside other equally possible variants. It is obvious that this is also accompanied by an “absolute identity through self-attribution” (Schmitz 2014: 61) – this point will be discussed in more detail in Section 4 below. The moment of the here (II) constitutes the spatiality of the primitive present. The intrusion of the new also plays a central role here, as the new is able to relate different places to each other: one’s own place, where Traktor and Wischtuch are spoken of (High German), the place of the stranger, which is the place of Trecker and Feudel (Low German) and all references. I establish a reference between Traktor and Trecker as well as between Wischtuch and Feudel; this creates a “system of relative places” (Schmitz 2014: 55). The body, and thus also the person, is bound to a place. In the confrontation with the new and its place, the previously absolute personal place becomes a relative place that only exists in a correlative relationship (cf. Schmitz 2014: 55).

In addition to the absolute place, the moment of the now of the primitive present (III) is the “absolute moment of the sudden in the irruption of the new” (Schmitz 2014: 55). This moment of now separates the past from the future and manifests itself complementary to the system of relative places as a “series of relative moments” (Schmitz 2014: 55; cf. also Köller (2019) on the connection between time and language in general). This creates a temporal flow consisting of past (I only know Traktor or Wischtuch), present (the existing: I hear Trecker or Feudel for the first time) and future (the imminent: All two/four variants are known to me and I understand them).

All this finally condenses in the penultimate moment of the primitive present, the moment of being (IV). Being describes the specifically human cognitive capacities such as “planning, expecting, remembering, hoping, fearing, fantasizing, playfully identifying with something” (Schmitz 2014: 57) and so on. This means that humans also have the ability to distance themselves from an object, which is necessary for orientation in the world (cf. Schmitz 2014: 57f.). Humans therefore do not exist as instinct-driven beings that simply react, but as acting beings. The This of the primitive present (V) functions as the moment that structures being; it shows the difference from everything and in its referential function as a means of referring to something and thus not referring to something else (cf. Schmitz 2014: 60). With planning, we focus on certain options, refer to them through our planning and neglect other options (I am writing this sentence and no other because I consider it necessary at this point). When we remember, we remember just this one situation or event, others remain forgotten (This one trip to the USA. This one visit to that fantastic restaurant). When we express an expectation (Please take out the garbage), we expect exactly that action and no other (I have now cleaned the windows instead). Or we expect this one linguistic variant (e.g., Traktor). In this way, the moment of this leads directly to the as-relation of recognition and understanding.

3.3 The symbolic-hermeneutic as-Structure of Recognition and Understanding

The description of the hermeneutic relevance of the as-structure (als-Struktur) goes back to Martin Heidegger (cf. also Graeser 1993). In general, the as-structure there concerns both interpretation and assertion (cf. Guidi 2021: 64). However, interpreting and asserting presuppose cognitive processes, namely recognition and understanding. Now, one might sarcastically remark that while interpreting requires understanding, this does not apply to asserting. I can certainly assert something without having even the slightest understanding of it. What we are talking about here are propositional statements about the world that make an assertion that follows truth claims. So we leave out such moral dubiousness.

Following Guidi (2021: 64), we can state that the as-structure in general is “a constitutive feature of every experience of entities in the world – namely, the way they always present themselves in terms of a ‘for something’”. But we now want to deal with a specific form of the as-structure, namely the as-structure of cognition and understanding, the necessity of which follows logically from the this of the primitive present (cf. (V) in Section 3.2). Westerkamp (2014: 68) describes to understand [verstehen] as a two-valued verb (I understand your statement.), which, however, has a three-valued relation (I understand your statement as ironic.). This shows that conceptual understanding is “always an understanding of something as something” (Westerkamp 2014: 68). Recognition works in the same way: Recognizing is syntactically two-valued in the sense of ‘someone grasps something with the mind’ (Uli recognizes the situation. https://grammis.ids-mannheim.de/verbs/view/400526/1, last accessed: March 12, 2024), but here, too, a three-valued relation is evident: Uli recognizes the situation as dangerous. In the negation of these relations – both of recognizing and understanding – the difference that was already mentioned at the end of Section 3.2 becomes apparent: In the sentence Uli does not recognize the situation as dangerous, it is not the recognition itself but the modal adverbial that is negated (as dangerous), which means that “this is not actually about a non-understanding, but about a different understanding of something” (Westerkamp 2014: 68). Taking this thought further, we can state the following with Kasper & Hoffmeister (in prep.): “Something perceived is only insofar determined as something as it is determined for something (cf. Cassirer 2009: 145), and it is determined for something through the aforementioned motor practices.”

4 Empirical Illustration using two Examples from the Dialectology of German

The approaches developed in Section 3 will now be illustrated and empirically tested using two examples from German dialectology. This testing serves on the one hand to check the plausibility of the ideas developed and on the other hand to explain the relationship between the dynamics and stability of dialects from a new, a representational perspective.

4.1 West Central German Lambdacism

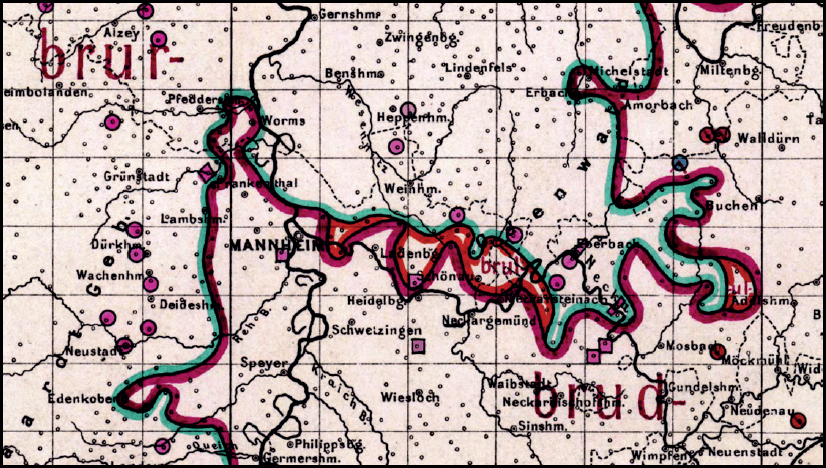

The West Middle German lambdacism (cf. the fundamental study by Lenz 2003 on the general language situation in West Central German), can be understood, for example, by the standard German word Bruder (brother). The phenomenon discussed here is about the following: It “refers to a historical substitution phenomenon in which – in the wcg. area of interest here – germ. Þ or ohg. d are represented as dialectal l” (Lameli 2015: 66). In concrete terms, this means that the standard-language Bruder (in the southern area, cf. Fig. 1) is contrasted with the dialectal Brurer in the northern area. In a border area, there is now an intended adoption of the dialectal form, but this fails, so that the people there produce Bruler instead of Brurer (recognizable in the center, Fig. 1).

The distribution of Bruder – Bruler – Brurer in wcg (conf. also Lameli 2015: 66).

The transitional area in which the intended adoption of the dialectal variant Brurer fails and in which the variant Bruler is produced instead can be defined as the region of West Central German lambdacism. Three questions are obvious: 1. Why do people try to adopt the dialectal variants? 2. Why do they not succeed? 3. What are the consequences of the failed adoption process? Lameli (2015) offers the following approach: Even if the conditions of emergence have not yet been fully clarified (cf. Lameli 2015: 66), some approaches can be traced back to the linguistic-geographical situation. Apical r allophones are generally predominant in the northern area, while uvular r variants predominate in the southern part (cf. Lameli 2015: 66). Lameli interprets the existence of lambdacism with reference to Wenker (2013 [1886]: 942) as an “effect of an intended adoption process […] in which speakers of the uvular r region strive to imitate apical rhotacism (Lameli 2015: 66–67).

Apart from a few exceptional cases, Lameli can show that the lambdacisms are all “directly at the rhotacism boundary” (Lameli 2015: 67), so that it can be assumed that this is a language contact phenomenon (cf. Lameli 2015: 68). In addition to this system linguistic explanation, Lameli also offers a sociolinguistic approach that focuses on the reasons for the lambdacism variant and is particularly interesting for the question described here. Metapragmatically, the phenomenon is the subject of evaluation processes; the speakers are stereotyped, and lambdacism is evaluated negatively (cf. Lameli 2015 with reference to Post 1992: 94). This is accompanied by a social positioning and demarcation of the speakers from the rhotacism or standard-equivalent region, which is an identity-securing measure for speakers outside the lambdacism region. It is even more surprising, however, that although the lambdacism variant is the subject of negative evaluations, there are no synchronization processes between speakers (see term (2) in footnote 17) that lead to the adoption of the d or r variant.

I would like to take these two explanatory approaches, the linguistic system on the one hand and the sociolinguistic on the other, as an opportunity for a further interpretation that places the speakers themselves at the center of the considerations and reflects on their situations and options for action. Three aspects that have already been theoretically developed above will be added to Lameli’s already very plausible explanation. What’s going on is firstly about speakers as affectively involved by language (1), then about the relation of presence, presentation, and representation (2) and finally about the symbolic-hermeneutic as-structure of recognition and understanding (3).

4.1.1 The human being as affectively involved by language

As speakers of a language, humans are affectively involved by it, as was shown in detail in Section 3.2. That is, language is close to humans (cf. Schmitz 2015: 157), from which certain (language) action dispositions and options follow.

If a speaker is affectively involved by the existence of two conflicting variants in opposition, namely Bruder and Brurer, then this is initially a purely individual phenomenon:

The facts of being affectively involved are not objective, but so peculiar that at most the person concerned – very often no one – can say them, although others can talk about them. (Schmitz 2015: 58).

Thus, as a speaker of Bruder, I can be affected by the Brurer variant (e.g. as insecurity, emotional closeness/distance or social prestige or all of these), I can ideally express this affectedness myself (to some extent) and make a (vague) statement about it (cf. Hoffmeister (in press) on the phenomenon of vagueness and its problematization). Meanwhile other speakers, who already have a substantial distance to my affective involvement, can talk about insecurities in a fundamental and abstracted way, emotional closeness/distance or social prestige, but not about my specific feelings in a certain situation, in which only I can make a statement about myself (I feel (not) comfortable with this way of speaking/this expression here now due to individual reasons).

Due to the affective involvement in this understanding, there is no possibility of effective distancing or dissociation in the contexts of everyday life. Lambdacism comes about precisely because of such a lack of effective distancing: the way of speaking concerns the speakers, it affects them whether they produce the standard variant d or the rhotacism r. The concern is always already pronounced; it is inherent in the human existence as a speaker. However, drawing conclusions in the form of a preference for a variant presupposes reflection on one’s own world position and the positioning of the self. This reflection results in the speakers recognizing themselves as speakers and developing needs and priorities in this function (cf. the symbolic-hermeneutic as-structure of recognition and understanding).

If we look back at the fundamental moments of the primitive present, these are central to the example of the choice of variant in favor of Brurer. The I (I) is confronted with something new (hearing the Brurer variant) and challenged by it. The Brurer variant thus represents a situational challenge (cf. Ünal, Ji & Papafragou 2021: 234). In the first confrontation (cf. Clopper 2021), coping strategies must be developed, which are also based on social evaluation processes. The spatiality or the Here (II) is obvious for the present example, not least because of the spatial a priori of regional language research (cf. Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 14). If, according to Schmitz (cf. Section 3.2), the new is able to relate different spaces to each other and thus constitutes not only the here, but ultimately also the human being in general, then in the case of our example, the southern space with the Bruder variant is placed in a relationship with the northern space (Brurer) through the appearance of the new, so that the “system of relative places” (Schmitz 2014: 55) emerges, namely as a place of the own (southern) and a place of the foreign (northern). The Now (III), which presupposes a before and an after, is also plausible due to the a priori status of time in linguistic interactions (cf. Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 26). The point in time at which a person encounters the new, still foreign variant (Brurer) for the first time is of individual relevance. This triggers an affectedness and places it in the temporal flow of the before, in which the variant was still unknown, and the after, in which the new variant becomes significant for one’s own being and linguistic identity.

This Being (IV) is the starting point for future linguistic actions and their planning. For Schmitz, it is responsible for specifically human cognitive capacities (planning, expecting, remembering, hoping, fearing, fantasizing, playfully identifying with something, cf. Section 3.2) and thus is not only affective-evaluative, but also conative, i.e., action-initiating. This brings us closer to an initial explanation of why the practical adoption of the new variant is intended. This opening up of options for action is only possible via the reference function of the last moment of the primitive present, the This (V). It is a matter of reference to something and not non-reference to something else. By adopting this variant (Brurer), I thus establish a relationship and refer (reference) to features that are associated with this way of speaking. In other word, I establish a relative identity.

These considerations show that by determining the five moments of the primitive present we can come close to an explanation of the intended adoption of the variant. Building on this, we will now turn our attention to the triad of presence – presentation – representation.

4.1.2 Presence – Presentation – Representation

Presence is closely related to the primitive presence described above. The affective involvement of language is a direct consequence of the human presence in the world. The world presents itself in its structures and situations, which are then represented by the affectively involved and cognitively capable speakers. The speakers are exposed to this “flow of changing environments and situations” (Schwemmer 1997: 25, quote see Section 3.1). Representations can thus be regarded as the human ability to process impressions of the world and thus to find one’s way in it. In the case of the lambdacism example, this means that the two variants d and r are presented (or present themselves) in the world and the present speakers perceive this presentation and thus represent it; the variants represent impressions. The processing sequences, the speech acts of the speakers (e.g., social indexical positioning practices or communicative acts such as the preference of a variant and the attempt at synchronization) are correspondingly expressions. The impressions are related to social information (How do I generally want to appear? How do I appear when I use brother or Brurer?). Finally, in the case of lambdacism, this results in an attempt at synchronization in favor of Brurer, which, however, fails due to the different r-production sites (uvular vs. apical) (cf. Lameli 2015: 66–67). The following is central:

It is not the intersubjective analysis of a concrete rhoticism, but the conceptualization, i.e., the subjective-mental representation of the phenomenon that is not only the goal, but also the primary calibration point of phonetic reproduction. (Lameli 2015: 71)

The maintenance of the resulting Bruler variant is then due to identity construction (see above). Because the present phoneme opposition has a meaningfulness (Bedeutsamkeit), i.e., the meanings are not (cannot be) neutralized, it is concise. Conciseness (Prägnanz) refers to the process of taking off from a basic structure (trajector-landmark) while meaning assessment; conciseness has a subjective component, so the conciseness postulate represents an alternative concept to frequency and entrenchment. Frequency, according to the basic assumption, is not the sole factor that leads to entrenchment, but rather it is about concise forms that are given relevance precisely because of their conciseness.

If conciseness is effective, the synchronization (thesis 1) of speaker and world takes place. The impression (Brurer) is recorded and represented. If Lameli (2015: 71) attaches particular importance to phonetics, then rhotacism is the central component of mental representation here, as it is the concise feature. However, in the attempt to produce isomorphism (thesis 2), the speakers fail because the apical r-variant causes them difficulties and their r-allophones are produced uvularly. This failed mapping process is then responsible for the incorrect Bruler variant.

4.1.3 The symbolic-hermeneutic as-structure of recognition and understanding

The as-relation of recognition is the general case of the as-relation of understanding. This differs in its hermeneutic understanding from the formal understanding of valence grammar. Understanding here is not a two-valued but a three-valued relation (someone understands something as something). In the same way, the as-relation of recognizing is also a three-valued relation: I recognize something as something. This differentiation of the general (recognizing) from the particular (understanding) is relevant for the lambdacism example. Speakers do not merely recognize a variant (e.g., Bruder), they recognize it as a specific variant alongside other possible variants (e.g., Brurer). The speakers do not merely understand the variant, they understand it as regional or socially indexical. This means that the existence of two variants is not merely concise (recognition), but relevant (understanding).

4.2 The Variation of bringen (to bring) in Rhine-Franconian

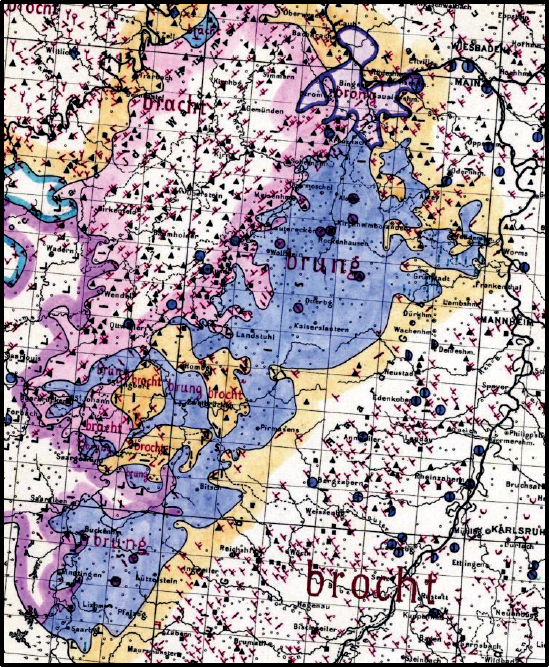

Now we come to the second example, the variation of standard German bringen (to bring) in Rhine-Franconian. This phenomenon is also observed in the greater region south of Frankfurt am Main to the west of Mannheim and Heidelberg – including the Kaiserslautern area (cf. fig. 2).

The variation of standard linguistic bringen (to bring) in Rhine-Franconian (Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 452).

In their standard work on language dynamics, Schmidt & Herrgen (2011: 153–167) analyze in detail the three inflectional classes of bringen, namely the weak, the strong and the mixed inflection. With this analysis, which Schmidt & Herrgen present for the verb bringen, the linguistic development “can be traced and explained precisely for the first time for large dialectal areas over a century using empirical data” (Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 154). In standard German, the verb bringen is inflected as follows: Infinitive: bringen (to bring), 1st pers. sg. past tense: ich brachte (I brought), past participle: gebracht (brought). In the Wenker map of 1880, the dialectal variant brung is documented in Rhine-Franconian for the standard participial formation gebracht, among others. These forms “are highly salient for speakers of the standard language and other dialects and are commented on derisively” (Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 155). However, a real-time comparison of different data sets shows “that the highly salient brung forms do not degrade” (Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 156), even though this feature should degrade quite quickly as a primary dialect feature. Quite the opposite, Schmidt & Herrgen (2011: 156) show that the feature not only does not degrade, but even spreads. The unique observation here is that

those born later […] have changed inflectional class with (ge)brung(en) (= strong inflection) compared to their ancestors and have thus morphologically distanced themselves both from the old dialect and from the standard language. (Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 156)

According to Schmidt & Herrgen, the explanation for this phenomenon is quite simple: the initial situation is that standard-language bringen – brachte – gebracht with the ablaut of i to a in addition to the dental suffix represents a system linguistically unique case in the German ablaut system (cf. Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 159). In child language acquisition, either *gebringt or *gebrungen are used before the standard variant of the participial form with a dental suffix is produced (cf. Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 160). Since the standard variant is a singular exception, it takes a certain amount of time before it is mastered without errors. The spread of the different (ge)brung(en) variants can now be explained by the fact that there is no “correction of brung forms during child dialect acquisition in the language area in question” (Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 161) on the part of the primary caregivers in linguistic socialization processes (cf. general Nilsson 2015). The (micro-)synchronization processes that are effective are such that passive competence is modified and the brung form is understood (relevance) and recognized (conciseness) and accepted as equivalent to other dialectal variants (cf. Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 162). According to Schmidt & Herrgen (2011: 163), the fact that the brung variant does not spread beyond structural boundaries (e.g., into Moselle Franconian) is because speakers are clear about which forms belong to their own (we identity) and which belong to the foreign way of speaking (they identity). While the strong inflection has thus stabilized in Rhine Franconian, a reverse process is evident in Moselle Franconian. From 1880 onwards, there is no longer any evidence of a previously detectable weak inflection, but only evidence of the mixed inflection (except for one individual case), although it can be assumed that this individual case is being reduced in favor of the general. The fact that the weak inflection was reduced in Moselle Franconian is because the mixed inflection, which is present in the standard language anyway, was dominant and the weak inflection as an exceptional case led to negative feedback, which in turn triggered mesosynchronization processes in favor of the mixed inflection.

Let us now look again at our starting points and bring them together with the explanations for the variation of standard-language bring in Rhine-Franconian.

4.2.1 The human being as affectively involved by language

About being affectively involved, it was stated above that language is close to the human being, from which certain dispositions to act follow. If we take the “regionalization of communication relations” (Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 161) as a basis and follow the premise that people are affectively involved by language and cognitively capable of reflecting on actions, then the “failure to correct brung forms in children’s dialect acquisition” (Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 161) is a direct consequence of involvement and subsequent reflection. In other words, people have an interest in preserving and transmitting the forms. It is part of their we identity (cf. the moments of I and Being of the primitive present). Since comprehension is not a problem and the variant is also positively valued in Rhine-Franconian as part of the regional language identity, the variant is stabilized as part of regional language knowledge. However, it is also important to note here that being affected is, by definition, something subjective. I myself am physically affected, realize this and recognize my involvement – it becomes concise. By comparing my situation, i.e., my being affected by brung, with other speakers and realizing that they are also affected (but possibly differently), I understand my own situation against the background of social structures – the use of brung becomes relevant.

For the rather astonishing spread of the brung forms, this means that the new and thus the initially still foreign is affectively involved due to its status as a lifeworld contrapunctus (cf. Section 3) and enters the “sphere of the own” (Schmitz 2014: 61).

4.2.2 Presence – presentation – representation

The person is present in the world, the world presents itself to the person, and as a result, the person represents the world. Using different variants of bringen (in the various inflectional classes), these are not only present, but they are also presented, since they affectively involve the speakers; this creates a synchronization process between the speaker perceiving the forms and the world in which the inflectional forms of bringen occur. Because the forms (especially brung) are not only salient for the speakers, but also pertinent, relevant to their lifeworld, they are cognitively visualized, i.e., represented. However, there is no identical representation of reality (this does not lead to the adoption of brung and the retention of one’s own paradigm, i.e. to stability), but rather a structural similarity (isomorphism) or rather a realization (Vergegenwärtigung), a processing that also goes hand in hand with charges and attributions of meaning (e.g. with evaluation patterns, social indexing, etc.), explaining the dynamics and the adoption of brung. This leads to the third aspect.

4.2.3 The symbolic-hermeneutic as-structure of recognition and understanding

The elementary connection between recognition and understanding and its as-structure is shown by the example of the bringen variation, in which we focus on the one hand on the system-linguistic connections and on the other hand on the social-indexical function of the brung form. Speakers not only recognize this form, but they also recognize it as an alternative in the verbal paradigm. They also understand the brung form as a prestige form with which they identify. For language acquisition and the lack of correction of initially incorrect forms (cf. Schmidt & Herrgen 2011: 161) in children, understanding-as is the central moment. We thus recognize the “absolute identity through self-attribution” (Schmitz 2014: 61), already explained in Section 3. According to the idea, I ascribe certain motives and characteristics to myself (e.g., regional and/or social affiliation), which I believe are attributed to me using a form (e.g., brung). My identity is therefore because I feel that I belong to a certain group of speakers through the use of brung.

5 Explaining the Dynamics and Stability of Dialects

We have seen that to be able to explain phenomena of linguistic variation in a well-founded way, we must look back at their relevance in the real world. There is no question that the speakers play a central role in this. However, they are not isolated, but interact with the world by absorbing the impressions that the world provides them with, i.e., presenting and processing them into expressions. For example, they absorb the variant brurer, evaluate it, place it against the background of their linguistic knowledge and their interests as speakers, and try to produce this variant as well. However, this fails due to the r-allophony and the lambdacism bruler emerges.

We have also seen that the three approaches of a model of linguistic representation. The person is affectively involved by language including the five moments of primitive presence, the triad of presence – presentation – representation and the hermeneutic-symbolic as-structure of recognition and understanding, are important starting points for explaining the dynamics and stability of dialects. The person affectively involved by language is responsible for both the dynamics and the stabilization of regional variants (cf. Sharma 2005).

In conclusion, central questions remain unanswered concerning the concept of linguistic representation. Conditions for its clarification are discussed in Kasper & Hoffmeister (in prep.). However, the modeling of the speaker as affectively involved by language can provide important insights into how the relationship between world and speaker can be determined. Linguistic representations, which we have determined as the result of a process of processing impressions into expressions, must then always be determined against this background. Furthermore, we should reflect on how the situation of people in their linguistic worlds, including social factors, affects representations.

If we look back at the state of research on representations in general and on linguistic representations as described in Section 2, it becomes clear that it is not expedient to assume linguistic representations as isolated mental units, but that they must be reflected phenomenologically in their lifeworld and action-related status (cf. Hausmann 1975). A modal theory of linguistic representations that considers the human being as an ecological, perceptive, acting, affective and cognitive being should therefore be the goal. In this article, the focus was primarily on the factor of involvement. Accordingly, further studies should focus primarily on the ecology, perception, agentivity and cognitivity or – in short – on the sociality (cf. Nilsson 2015), cognitivity and pragmaticity of representations. Furthermore, it would be desirable if the approach presented here were also applied to the variational situation in other languages and language families (cf. Auer, Hinskens & Kerswill 2005) to further explore the transferability and applicability of the ideas.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written as part of the Research Training Group 2700 and is funded by the German Research Foundation (project number 441119738). I would like to thank Simon Kasper (Düsseldorf) for his valuable comments on this article. I would also like to thank all members of the Research Training Group 2700 for constructive and critical general discussions. Any remaining criticisms are solely my responsibility.

-

Note

All German-language quotations in the text were translated into English by the author Toke Hoffmeister. He is responsible for any inaccuracies.

References (all links accessed February 2024)

Adger, David. 2022. What are linguistic representations? Mind and Language 37: 248–260.10.1111/mila.12407Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, Michael L. & Gregg Rosenberg. 2008. Content and action: The guidance theory of representation. The Journal of Mind and Behavior 29: 55–86.Suche in Google Scholar

Auer, Peter, Frans Hinskens & Paul Kerswill. 2005. Dialect Change: Convergence and Divergence in European Languages. Cambridge: University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486623Suche in Google Scholar

Barsalou, Lawrence W. 1992. Frames, Concepts, and Conceptual Fields. In Frames, Fields, and Contrasts: New Essays in Semantic and Lexical Organization, 21–74, eds Adrienne Lehrer & Eva Feder Kittay. Hillsdale, New Jersey, Hove and London: Erlbaum.Suche in Google Scholar

Bjerva, Johannes et al. 2019. What Do Language Representations Really Represent? Computational Linguistics 45: 381–389.10.1162/coli_a_00351Suche in Google Scholar

Branigan, Holly P. & Martin J. Pickering. 2017. An experimental approach to linguistic representation. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 40: 1–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1600202810.1017/S0140525X16002028Suche in Google Scholar

Brentano, Franz. 1874. Psychologie vom empirischen Standpunkte. 2 vols. Leipzig: Duncker and Humblot.Suche in Google Scholar

Cassirer, Ernst. 2009. Form und Technik. In Ernst Cassirer: Schriften zur Philosophie der symbolischen Formen, 123–167, ed. Marion Lauschke. Hamburg: Meiner.10.28937/978-3-7873-2121-6Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Regeln und Repräsentationen. Translated by Helen Leuninger. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1983. Mental Representations. Syracuse Scholar (1979–1991) 4: Iss. 2, Art. 2: 1–17.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. New horizons in the study of language and mind. Cambridge: University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511811937Suche in Google Scholar

Clopper, Cynthia G. 2021. Perception of Dialect Variation. In: The Handbook of Speech Perception, 335–364, eds Jennifer S. Pardo, Lynne C. Nygaard, Robert E. Remez, David B. Pisoni. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, Adam S., Joni Y. Sasaki & Tamsin C. German. 2015. Specialized mechanisms for theory of mind: Are mental representations special because they are mental or because they are representations? Cognition 136: 49–63.10.1016/j.cognition.2014.11.016Suche in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 1998. Linguistic evidence and mental representations. Cognitive Linguistics 9: 151–173.10.1515/cogl.1998.9.2.151Suche in Google Scholar

Cummins, Robert C. 1989. Meaning and mental representation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/4516.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Cummins, Robert C. 1991. The role of representation in connectionist explanations of cognitive capacities. In Philosophy and connectionist theory, 91–114, eds William Ramsey, Stephen P. Stich & David E. Rumelhart. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Elbaum Associates.Suche in Google Scholar

Egan, Frances. 2012. Representationalism. In The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Cognitive Science, 250–272, eds Eric Margolis, Richard Samuels & Stephen Stich. Oxford: University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195309799.013.0011Suche in Google Scholar

Fanselow, Gisbert & Sascha W. Felix. 1984. Noam Chomsky. Grammatik als System kognitiver Repräsentationen. Sprache und Literatur in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 15: 31–56.Suche in Google Scholar

Guidi, Lucilla. 2021. As-structure (Als-Struktur). In The Cambridge Heidegger Lexicon, 64–67, eds Mark A. Wrathall. Cambridge: University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9780511843778.01610.1017/9780511843778.016Suche in Google Scholar

Grabarczyk, Paweł. 2021. Are representations glorified receptors? On use and sage of mental representations. Semiotica 240: 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2021-001310.1515/sem-2021-0013Suche in Google Scholar

Graeser, Andreas. 1993. Das hermeneutische ‘als’. Heidegger über Verstehen und Auslegung. Zeitschrift für philosophische Forschung 47: 559–572.Suche in Google Scholar

Hausmann, Robert B. 1975. Underlying representations in dialectology. Lingua 35: 61–71.10.1016/0024-3841(75)90073-XSuche in Google Scholar

Hoffmeister, Toke. 2021a. Sprachwelten und Sprachwissen. Theorie und Praxis einer kognitiven Laienlinguistik. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110749489Suche in Google Scholar

Hoffmeister, Toke. 2021b. Das laienlinguistische Konzept von Variation. Regional – funktional – sozial. Linguistik Online 110: 75–95. https://doi.org/10.13092/l0.110.814010.13092/lo.110.8140Suche in Google Scholar

Hoffmeister, Toke. in press. Vage Differenzen. Das Konzept der Vagheit als inhärentes Merkmal laienlinguistischen Wissens. In Übersetzung für/von Laien. Perspektiven auf die Laientranslation und Laientranslatologie in der Romania, eds Marco Agnetta & Sofia Dalkeranidou. Hildesheim: Olms.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoffmeister, Toke. forth. Sprachnormen als Resultate diskursiver Praxis. Aushandlungsprozesse in einer Kultur der Digitalität. In Linguistik 2.0. Sprachdiskurse in Neuen Medien, eds Lieselotte Anderwald & Elmar Eggert. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Kasper, Simon. 2015. Instruction Grammar. From Perception via Grammar to Action. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110430158Suche in Google Scholar

Kasper, Simon. 2020. Der Mensch und seine Grammatik. Eine historische Korpusstudie in anthropologischer Absicht. Tübingen: Narr.Suche in Google Scholar

Kasper, Simon & Toke Hoffmeister. in prep. Herausforderungen an einen Begriff der mentalen sprachlichen Repräsentation. In Repräsentationen aus linguistischer und interdisziplinärer Perspektive (Special Issue of Germanistische Linguistik), eds Toke Hoffmeister, Mathias Scharinger & Christina Kauschke. In English: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379075027_Philosophical_and_linguistic_challenges_to_the_concept_of_mental_linguistic_representation_English_translation_of_KasperHoffmeister’s_2024_German_preprint_of_the_same_title).Suche in Google Scholar

Kasper, Simon & Christoph Purschke. 2023. Whatever happened to the Scene Encoding Hypothesis? Salience and pertinence as the missing links between the Usage-based Model and Scene Encoding. Constructions 15: 1–22. https://doi.org/10.24338/cons-610.Suche in Google Scholar

Köller, Wilhelm. 2019. Die Zeit im Spiegel der Sprache. Untersuchungen zu den Objektivierungsformen für Zeit in der natürlichen Sprache. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110664942Suche in Google Scholar

Krämer, Sybille. 2010. Sprache, Stimme, Schrift: Zur impliziten Bildlichkeit sprachlicher Medien. In Sprache intermedial. Stimme und Schrift, Bild und Ton, 13–28, eds Arnulf Deppermann & Angelika Linke. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110223613.11Suche in Google Scholar

Krämer, Sybille. 2014. Zur Grammatik der Diagrammatik. Eine Annäherung an die Grundlagen des Diagrammgebrauches. On the Grammar of Diagrammatics. An Approach to the Fundamentals of using Diagrams. Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik 44: 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF0337971210.1007/BF03377227Suche in Google Scholar

Krämer, Sybille. 2016. Figuration, Anschauung, Erkenntnis. Grundlinien einer Diagrammatologie. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Suche in Google Scholar

Krämer, Sybille. 2020. Medium, Bote, Übertragung. Kleine Metaphysik der Medialität. Berlin: Suhrkamp.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1999. Philosophy in the Flesh. The embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. New York: Basic Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Lameli, Alfred. 2015. Zur Konzeptualisierung des Sprachraums als Handlungsraum. In Deutsche Dialekte. Konzepte, Probleme, Handlungsfelder, 59–83, eds Michael Elmentaler, Markus Hundt & Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Stuttgart: Steiner.Suche in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 1999. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Vol. 1: Theoretical Prerequisites. Stanford: University Press.10.1515/9780804764469Suche in Google Scholar

Lenz, Alexandra N. 2003. Struktur und Dynamik des Substandards. Eine Studie zum Westmitteldeutschen (Wittlich/Eifel). Stuttgart: Steiner.Suche in Google Scholar

Leybaert, Jacqueline. 1998. Phonological representations in deaf children: the importance of early linguistic experience. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 39: 169–173.10.1111/1467-9450.393074Suche in Google Scholar

Malt, Barbara C. 2024. Representing the World in Language and Thought. Topics in Cognitive Science 00: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.1271910.1111/tops.12719Suche in Google Scholar

Mondal, Prakash. 2022. The Puzzling Chasm Between Cognitive Representations and Formal Structures of Linguistic Meanings. Cognitive Science 46: e13200. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.1320010.1111/cogs.13200Suche in Google Scholar

Mondal, Prakash. 2023. Towards a unified representation of linguistic meaning. Open Linguistics 9: 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2022-022510.1515/opli-2022-0225Suche in Google Scholar

Nilsson, Jenny. 2015. Dialect accommodation in interaction: Explaining dialect change and stability. Language and Communication 41: 6–16.10.1016/j.langcom.2014.10.008Suche in Google Scholar

O’Brien, Gerard & Jon Opie. 2004. Notes Toward a Structuralist Theory of Mental Representation. In Representation in Mind. New Approaches to Mental Representation, 1–20, eds Hugh Clapin, Phillip Staines & Peter Slezak. Amsterdam a.o.: Elsevier.10.1016/B978-008044394-2/50004-XSuche in Google Scholar

Pelc, Jerzy. 1971. Studies in functional logical semiotics of natural language. Berlin: Mouton.10.1515/9783110828375Suche in Google Scholar

Pitt, David. 2020. Mental Representation. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, eds Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/mental-representationSuche in Google Scholar

Post, Rudolf. 1992. Pfälzisch. Einführung in eine Sprachlandschaft. 2nd ed. Landau: Pfälzische Verlagsanstalt.Suche in Google Scholar

Preston, Dennis R. 1989. Perceptual Dialectology. Nonlinguists’ Views of Areal Linguistics. Dordrecht and Providence: Foris.10.1515/9783110871913Suche in Google Scholar

Purschke, Christoph. 2011. Regionalsprache und Hörerurteil. Grundzüge einer perzeptiven Variationslinguistik. Stuttgart: Steiner.10.25162/9783515101561Suche in Google Scholar

Purschke, Christoph. 2014. I remember like it was interesting. Zur Theorie von Salienz und Pertinenz. Linguistik online 66: 31–50. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.66.157110.13092/lo.66.1571Suche in Google Scholar

Purves, Ross S. et al. 2023. Conceptualizing Landscapes Through Language: The Role of Native Language and Expertise in the Representation of Waterbody. Related Terms. Topics in Cognitive Science 15: 560–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.1265210.1111/tops.12652Suche in Google Scholar

Quilty-Dunn, Jake, Nicolas Porot and Eric Mandelbaum. 2023. The best game in town: The reemergence of the language-of-thought hypothesis across the cognitive sciences. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 46, e261: 1–75.10.1017/S0140525X23002431Suche in Google Scholar

Ramsey, William M. 2007. Representation Reconsidered. Cambridge: University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511597954Suche in Google Scholar

Rey, Georges. 2020. Representation of language. Oxford: University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198855637.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Rosa, Hartmut. 2023. Resonanz. Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. 7th ed. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.Suche in Google Scholar

Scheerer, Eckart et al.: Repräsentation. In Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie online. https://doi.org./10.24894/HWPh.5675Suche in Google Scholar

Schmidt, Jürgen Erich. 2016. Neurodialektologie. Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik 83: 56–91.10.25162/zdl-2016-0003Suche in Google Scholar

Schmidt, Jürgen Erich & Joachim Herrgen. 2011. Sprachdynamik. Eine Einführung in die moderne Regionalsprachenforschung. Berlin: Erich Schmidt.Suche in Google Scholar