Abstract

This work examines the memetic communication of the main right-wing populist movements in different Latin American countries – Brazil, Argentina, and El Salvador – during electoral competition for their countries’ presidency. The study seeks to understand how new Generative AI tools affect the dynamics in which these memes are produced and distributed, intensifying political polarisation. The methodology combines online and offline research to analyze how memetic communication mobilises elements that promote political polarisation and incite violence. Between September 2022 and February 2024, in the weeks before and after each presidential election, I collected and analyzed visual data using open-source software. Specifically, memes were gathered through open Telegram groups of right-wing populist supporters of Bolsonaro, Bukele, and Milei. I also conducted ethnographic fieldwork and digital ethnography during the weeks preceding the elections to capture online and offline discourses and the affective milieu of each electoral campaign as a means to contextualise the social media data and the impact of the memetic communication. Overall, the research shows the central role that Generative AI is playing in the way memetic communication operates, ultimately reinforcing political polarisation and the legitimisation of violence against political opponents and other social groups who are stereotyped, denigrated and deshumanised.

1 Objectives and Methods

The research seeks to understand how memetic representations of political antagonists normalise various forms of violence, building on previous studies that explore the dynamics of memetic communication. Furthermore, it aims to compare communicative productions made with generative AI tools, such as Stable Diffusion, MidJourney, DALL-E, and GANs, with those made without such technologies, to investigate the impact of generative AI on the production and distribution of memetic content. This analysis considers how generative AI intensifies political polarisation and fosters segmented information bubbles that reinforce stereotypes and legitimise violence, particularly against marginalised social groups.

The methodology combines visual data collection with digital ethnography, focusing on open Telegram groups where extreme right-wing supporters actively participate in political discourse. Between September 2022 and February 2024, visual data was collected in the weeks leading up to and following each presidential election in Brazil, Argentina, and El Salvador. Specifically, data was gathered from six Telegram groups, with two groups per country, each comprising one group considered the “official account” of a right-wing populist politician and one self-managed group. The Telegram groups were accessed by using keywords in the app’s search tool and by following open links shared on social media. These groups, open for member interaction, provide insight into the memetic strategies used by the supporter networks of prominent right-wing figures: Bolsonaro in Brazil, Milei in Argentina, and Bukele in El Salvador.

In Brazil, data collection took place from September 1 to October 30, 2022, covering the electoral rounds held on October 2 and October 30. The “Carlos Bolsonaro – official account” group, with 144,267 members, contributed 72 images, while the “Bolsonarista” group, with 38,362 members, provided 17,072 images. For Argentina’s elections on October 22 and November 19, 2023, data collection spanned from October 1 to November 30, with the “Javier Milei official” group (675 members) contributing 1,564 images, and the “Milei president 23–27. Long live freedom” group (481 members) contributing 6,202 images. In El Salvador, data was collected between December 4, 2023, and February 4, 2024, in connection with the single-round election on February 4. Here, the “Nuevas ideas” group (140 members) provided 118 images, while the “Nayib Bukele” group (3,333 members) contributed 518 images.

The collected images were analysed according to their production method, classifying them as either manually created or AI-generated, using tools such as Illuminarti to establish an AI production probability threshold of 50 % or higher. Discursive elements specific to each form of production were identified, followed by comparative analysis both within and across the three countries. Ethnographic and digital ethnographic fieldwork complemented this data by capturing online and offline discourses and the affective climate of each campaign period, providing contextual depth to the visual data and enhancing understanding of the role of memetic communication in these politically charged environments. All quotations from supporters in this article were obtained both from open Telegram groups and other publicly accessible digital materials, as well as from testimonies collected during electoral campaign events. All testimonies cited were collected directly by the author during fieldwork at these campaign events in Brazil, Argentina, and El Salvador.

2 It’s not Funny Anymore: “Good Bandit, Dead Bandit”[1]

On a fateful day in early November 2022, a dramatic turn of events unfolded in Brazil. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva had narrowly defeated the ultra-conservative Jair Messias Bolsonaro to become the President of Brazil. Having spent the previous month immersed in research on the political behaviour of right-wing populism and the campaign tactics of the Bolsonaro movement, I witnessed the aftermath first-hand.

The outcome sparked a wave of protests organised by Bolsonaro supporters who vehemently denounced alleged electoral fraud and demanded a military intervention they dubbed “federal intervention.” Truck drivers blockaded major highways, disrupting the normal flow of people and goods. In Rio de Janeiro, thousands of individuals gathered on Presidente Vargas Avenue, clad in bright yellow football shirts, which had become a symbol of Bolsonarist nationalism. The avenue transformed into a sea of flags as attendees raised their arms in praise of God, fervently prayed, and engaged in military gestures. The national anthem resounded through the air, accompanied by creative displays like cardboard ballot boxes advocating for printed votes and even a Batman car declaring support for Bolsonaro.

The atmosphere was charged with aggression unlike anything seen before. Anger and a sense of loss permeated the crowd. Voices cried out for army intervention in parliament, accusing the leftist PT party of corruption and vehemently rejecting any notion of a stolen election. Conspiracy theories of communist plots and comparisons to Venezuela’s dire state were thrown around with fervour. One woman demanded the protection of children from indoctrination, while clutching her daughter tightly. The background echoed with the mantra of Bolsonarismo: “Brazil above everything, God above everyone!”

In the aftermath, thousands of Bolsonaro supporters camped outside various military headquarters, rallying for military intervention. The climax came on a Sunday in January in Brasilia, the capital of Brazil. Protesters, with the tacit approval of the Military Police, stormed the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial powers, reminiscent of the shocking scenes witnessed during the US Capitol invasion. This attempted coup embodied the escalating violent rhetoric that had become increasingly prevalent during the electoral campaigns. “He is not funny anymore, even the memes in which he appears are no longer funny, Lula is a bandit. All left-wing politicians are bandits. He deserves to be in jail,” shouted a supporter at a campaign rally.

The Bolsonarismo campaign, much like in 2018, heavily relied on a deluge of memes, images, and viral TikTok videos disseminated through social media. These campaign messages often exhibited cognitive dissonance, distorting reality and blurring the lines of truth. Elements such as demonstrations in favour of military intervention, conspiracy theories about electoral fraud and communism, or denial of climate change played a central role. While not entirely new to Brazilian politics, their scale and intensity in 2022 were unprecedented. Fake news recycled from the 2018 campaign reappeared, such as the story of anatomically shaped baby bottles allegedly distributed in schools, the propagation of “gay kits” aimed at indoctrinating children, and fearmongering about a future Lula-led government where people would be forced to eat dogs. The political rival, Lula da Silva, was dehumanised, portrayed as a monster through a relentless barrage of character attacks.

Throughout the election cycle, this alternative reality gained traction in public spaces, fuelling demonstrations outside military institutions and ultimately culminating in the attempted coup. The events of January 8 revealed that Bolsonaro’s supporters did not interpret his electoral defeat within the framework of liberal democracy but rather through the lens of historical authoritarianism. They believed they had the superior right to demand armed intervention, viewing themselves as the “good citizens” with undeniable rights while others were seen as lacking. This normalisation of aggressive rhetoric and the open attack on democracy spread throughout the country, fueled by information bubbles and segmented algorithms that intensified political polarisation. “We are good citizens. We don’t steal, and we don’t steal elections. Bolsonaro should execute all bandits, of all types. Good bandit, dead bandit,” roared a man with several stickers in support of Bolsonaro.

A similar scene played out in Argentina during its own presidential elections in October 2023. The political landscape was marked by intense polarisation and an atmosphere of high tension. Supporters of the radical libertarian Javier Milei and the Peronista Sergio Massa filled the streets, with rallies and counter-rallies often occurring simultaneously. Milei will put an end to corruption. “The country is full of bandits. Have you seen the news on the social networks? The country is in ruins, we have to put an end to the bandits, there are bandits everywhere, some of them should be killed”, exclaimed a demonstrator wearing a T-shirt with a lion on it. The streets were awash with banners, flags, and political paraphernalia as impassioned citizens voiced their support and disdain.

In Buenos Aires, violent clashes erupted between supporters of the incumbent and the opposition, with police intervention becoming a common sight to control the aggressive confrontations. “The zurdos (leftists)[2] are laughing at the police on social media. I’ll tell you one thing, the police are allowing those fucking rojos (reds) to walk down the street in peace among so many bandits, explained a middle-aged woman in the capital. Beyond these immediate confrontations, Argentine political culture during the 2023 elections was marked by a saturation of memes framing Milei as a “chainsaw liberal” and heroic lion, while Peronist opponents were demonised as corrupt “enemies of civilisation.” Such framings echoed long-standing discourses on morality, state inefficiency, and corruption, giving the meme battles a historical resonance that went beyond the electoral moment.

Meanwhile, in El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele’s dominance in the 2024 election was virtually uncontested. With over 70 % of the electorate supporting him in the polls, Bukele dismissed the need for a traditional electoral campaign, boasting about his overwhelming popularity. Indeed, he has a constant social media presence that allowed him to stay away from campaigning during elections. Yet his party Nuevas Ideas actively campaigned for the legislative elections, disseminating messages that emphasised Bukele’s success in reducing crime while framing the opposition as a threat to national security. Supporters of Nuevas Ideas circulated images and narratives focused on how a victory of Bukele’s opponents would result in the release of imprisoned gang members, fuelling fears of chaos and violence. “Human rights should only exist for the right humans, not for pandilleros (gang members). There are hard-working people in poor neighbourhoods, those pandilleros decided to kill and torture. Thanks to our president they are now receiving their punishment,” exclaimed a satisfied neighbour at a campaign rally in San Salvador.

Despite the overwhelming support his candidacy canvassed, signs of electoral fraud, intimidation, and political suppression permeated the process, with critics fearing speaking out against the president due to cases of jailed or disappeared political opponents. Much like in Brazil, in El Salvador, pro-government content dominated the social media landscape, limiting the visibility of critical voices and discouraging dissent. “I have many funny pictures on my phone in which my president is always giving those pandilleros a good lesson. He has raised the economy by making El Salvador a safe country, where tourists want to come”, said another campaigner, wearing a T-shirt with the “B” for “Bukele” on it. At the same time, the Salvadoran case was also shaped by deep social inequalities and widespread fear of repression. Critics pointed to arrests of journalists and opposition figures, which created an atmosphere of intimidation. This broader context reinforced the appeal of memes portraying Bukele as the sole guarantor of security and prosperity.

In the digital realm, the situation was equally volatile. Memes, viral videos, and incendiary posts flooded social media platforms, each side attempting to outdo the other in a bid to sway public opinion. Memes played a crucial role in this digital warfare, often distorting facts and spreading misinformation to undermine opponents. The digital campaigns were marked by the rapid production and dissemination of content aimed at discrediting political rivals and influencing the electorate through humour, irony, and exaggerated claims. In this article, I use the term “memetic violence” to describe the ways in which jokes, ridicule, and ironic exaggerations in memes work to trivialise or legitimise aggression against political opponents and minorities. Rather than being understood as harmless entertainment, such practices become part of a communicative repertoire that naturalises hostility and exclusion.

The objective of this study is to examine the memetic communication strategies employed by right-wing populist movements in Brazil, Argentina, and El Salvador during their presidential campaigns. These digital battles were not just confined to humorous or satirical content; they included deeply personal attacks, false information, and even fabricated scandals designed to tarnish reputations. The use of AI to generate memes added a new dimension to the propaganda efforts, making it easier to create and distribute content that appeared authentic but was misleading or entirely false. This digital cacophony contributed to an atmosphere of distrust and scepticism, further polarising an already divided electorate.

In the three countries, the interplay between street-level political activism and digital propaganda underscored the power of memes and AI-generated content in shaping public perception and political discourse. The high levels of political tension and polarisation were amplified by the ease with which misinformation and emotionally charged content could be produced and spread. This highlighted the need for greater media literacy and regulatory oversight to safeguard the integrity of democratic processes.

In order to analyse this phenomenon, the article is structured to first address the types of violence that memetic communication can generate and the significance of this field within cultural studies. It then delves into the case studies of Brazil, Argentina, and El Salvador. This section includes data illustrating the evolving role of generative AI in political polarisation during election periods. The paper concludes with reflections on the challenges facing Latin American society as generative AI increasingly shapes right-wing visual narratives, primarily in constructing violent discourses around national “enemies.”

3 Right-Wing Populism and Far-Right 2.0

Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Nayib Bukele in El Salvador or Javier Milei in Argentina are just a few of the paradigmatic cases which represent, at different levels, the rise of populism, the advances of right-wing radicalism and the resurgence of extreme nationalism in Latin America. In this article, I use the term “right-wing populism” to refer, as some Latin Americanists indicate (Cesarino 2020), to the ideological conservative elements and national-populist influences (mainly the construction of political antagonisms), alongside the explicit praise and support of local capitalist systems (Cannon 2016). Building on this literature, this term describes movements that merge conservative ideological elements with nationalist antagonisms, while openly celebrating capitalist economic orders.

The cohesive element at the regional level is the post-colonial historical situation and the gradual militarisation of the civilian sphere (Bayarri 2022; Colussi et al. 2023; Montoya 2018). Latin America’s colonial roots engendered a profoundly hierarchical society whose dominant classes have felt threatened by a series of recent rights advances on the part of the most vulnerable groups, responding in reactionary terms. It is also common to observe these leaders advocating greater military investment, as well as speaking nostalgically of the order and security that military regimes would have brought to their countries in the past. This framing also makes visible the weight of nationalism in the Latin American cases: Bukele, for example, is best understood not as a pure populist but as a populist nationalist, whose rhetoric is consistently tied to sovereignty, militarisation, and exclusion.

A “populist leader” is thus defined here as someone who presents themselves as the embodiment of “the people,” while identifying and vilifying internal and external enemies. However, beyond the sociological aspects of the phenomenon, the construction of right-wing populist leaders as representatives of a mass phenomenon requires in-depth studies of new forms of communication. The dynamics of social networks encourage disintermediated communication and favour the communication strategies of what Forti calls “Far-right 2.0” (Forti 2021), highlighting exaggerated communication and polarisation. Among the characteristics of these movements, the following stand out: (1) the ideological elements and (2) the use of new technologies and social networks for the construction of simplified, dichotomous political propaganda that spreads rapidly through allegorical forms (Bizberge and Segura 2020), such as the use of bots to disseminate fake news. The distortion and manipulation of information for political purposes in social media is among the mechanisms most employed by right-wing populist politicians (Ardévol-Abreu 2022; Bakir and McStay 2018).

The communication strategies of the right-wing populists benefit from the dynamics of social networks through the publication of tweets, memes and lives, formats that circulate quickly and favour politicians during electoral campaigns, when the main objective of communication is to attract voters and win votes (Ross and Rivers 2017). In this sense, the political content published on social networks is characterised by speed and excess (Zafra 2017). Both the images and videos disseminated promote a rapid expansion of political content, whether informative or opinionated, while at the same time slowing down the in-depth reproduction of reasoned argumentation. These characteristics reinforce the role of non-verbal communication in this type of format, where the audience tends to pay more attention to the aesthetic, communicative and compositional elements of the environment (Campos Mello 2020).

Simplified messages, frequently used in the content disseminated on social networks by right-wing populists often employ resources such as metaphors, which, according to Musolff (2016), provide added pragmatic value to the descriptions. Structural and conceptual metaphors, as well as analogical representations of objects or realities, express evaluations that appeal to emotions, promoting emotional or disproportionate responses. Structural metaphors are often designed to articulate a political discourse with concrete non-verbal communication. The structural metaphor of “just war” (Lakoff 2002), in which good and evil can be opposed, is a typical example, as non-verbal communication can reinforce the aesthetic elements of a middle-class leader representing his people.

Moreover, such metaphors can distort the complexity of reality, so that its dimensions are reduced to an easy solution. Considering that metaphors are based on a historical semantic framework, this allows recipients to incorporate the new information into existing schemas (Shifman 2014).

4 Memetic Violence in Latin American Cultural Studies

While extensive scholarship has analysed the rhetorical strategies of right-wing populism globally, understanding of the communicative mechanisms that normalise violent discourse within this spectrum remains limited. In previous collaborative studies on the spread of right-wing populist ideas via internet memes, we identified a strategy commonly used by these groups: reducing complex social issues to binary oppositions of “good” versus “evil” (Fernández-Villanueva and Bayarri 2021). This approach, which casts political and social actors in rigid, polarised categories, finds historical resonance in 20th-century fascist rhetoric (Burdett 2003).

However, what distinguishes today’s meme-driven discourse is the way that these divisive framings are not only normalised but also amplified within digital spaces, where oversimplification and exaggeration fuel their viral appeal (Gallardo 2018). This dynamic, as Ahmed (2013) argues, illustrates how emotions can become attached to and mobilised by symbols and images, which, when circulated on social media, foster collective sentiments of approval or disdain among viewers.

Internet memes, typically combining an image with a concise text, serve as efficient vectors for conveying humour, particularly through the lens of ridicule, satire, and exaggeration (Dynel and Messerli 2020). This form of humour is highly multimodal, engaging recipients on various perceptual levels, as evidenced by scholars exploring the semiotics of memes (Hakoköngas et al. 2020; Ross and Rivers 2017; Smith 2019). In this regard, Shifman’s (2014) concept of “hyper-meaning” is especially relevant, as it captures the condensation of complex meanings within memes, where visual and textual elements converge to produce messages that are both accessible and ideologically charged. These messages are crafted to appeal directly to audiences’ emotions, often sparking strong reactions that facilitate the message’s circulation.

Political groups, notably right-wing populist factions, have harnessed this capacity for condensed meaning in memes to reframe and simplify complex narratives, deploying emotive phrases and evaluative language that resonate with and mobilise specific target groups. Here, Ahmed’s (2013) argument about affective attachment to objects and symbols adds another layer of understanding, suggesting that the emotions tied to memes not only engage recipients’ attention but also encourage them to internalise the polarised perspectives conveyed in these images.

Parker (2019) further notes the role of play and imagination in meme culture, where memes elicit an immediate, often non-rational pleasure that captivates users across various digital subcultures. This aspect of meme culture complicates the nature of political engagement in these online spaces, as it suggests that users are drawn in not only by ideological content but also by the humorous, irreverent playfulness that characterises memes, making the spread of divisive messages all the more potent.

Political memes in the Latin American context are not simply visual humour or light content; they are powerful tools for constructing and reinforcing dominant ideologies that often legitimise social and political exclusions (Bayarri and Fernández-Villanueva 2025a) . From a cultural studies perspective, memetic communication employs deeply rooted cultural symbols and practices to create simplified representations that reinforce power structures, often under the guise of humor or satire (Parrot and Hopp 2020).

Generative AI has intensified the capacity of memes to shape public opinion. By enabling the rapid, personalised creation of visual content, AI tools such as Stable Diffusion and MidJourney facilitate the spread of images that reflect and amplify political polarisations and social tensions, allowing humour and irony to mask messages of exclusion or symbolic violence toward certain social groups (Askanius 2021). Rather than fostering a diversity of opinions, AI-driven meme culture tends to consolidate authoritarian and nationalist discourses, legitimising representations of militarism and xenophobia, especially in Latin American environments marked by postcolonial and authoritarian legacies (Tortorici and Fernández-Galeano 2023).

Cultural studies help us understand that these memes do not only act as reflections but as generators of sociocultural realities, shaping how people perceive “the other” as threats or national enemies (Billig 2019). This dynamic creates an affective alignment where users become increasingly polarised, emotionally identifying with a political identity through shared symbols (Hall 2007), as is common with memes. This type of visual communication becomes a constant reaffirmation process, creating information bubbles that reinforce stereotypes and legitimise symbolic or even literal violence against marginalised groups such as women, LGBTQ+ individuals, or racialised communities (King 2024).

The impact of these memes is not limited to social networks; their effects extend offline, influencing attitudes and perceptions in everyday life. Thus, memes become a vehicle for polarisation and hate speech, reinforcing an exclusionary view of reality in a political framework that feeds on social divisions and conflicts (Bayarri and Fernández-Villanueva 2025b).

5 Brazil, Argentina and El Salvador: Memetic Communication and AI

The analysis of meme-based communication in Argentina, Brazil, and El Salvador underscores how both generative AI and manually produced memes contribute to ideological polarisation and the construction of nationalistic narratives and methaphors. Each country demonstrates unique thematic emphases and stylistic choices, shaped by the socio-political context, that reveal distinct approaches to representing political leaders, national identity, and opposition groups (Montage 1).

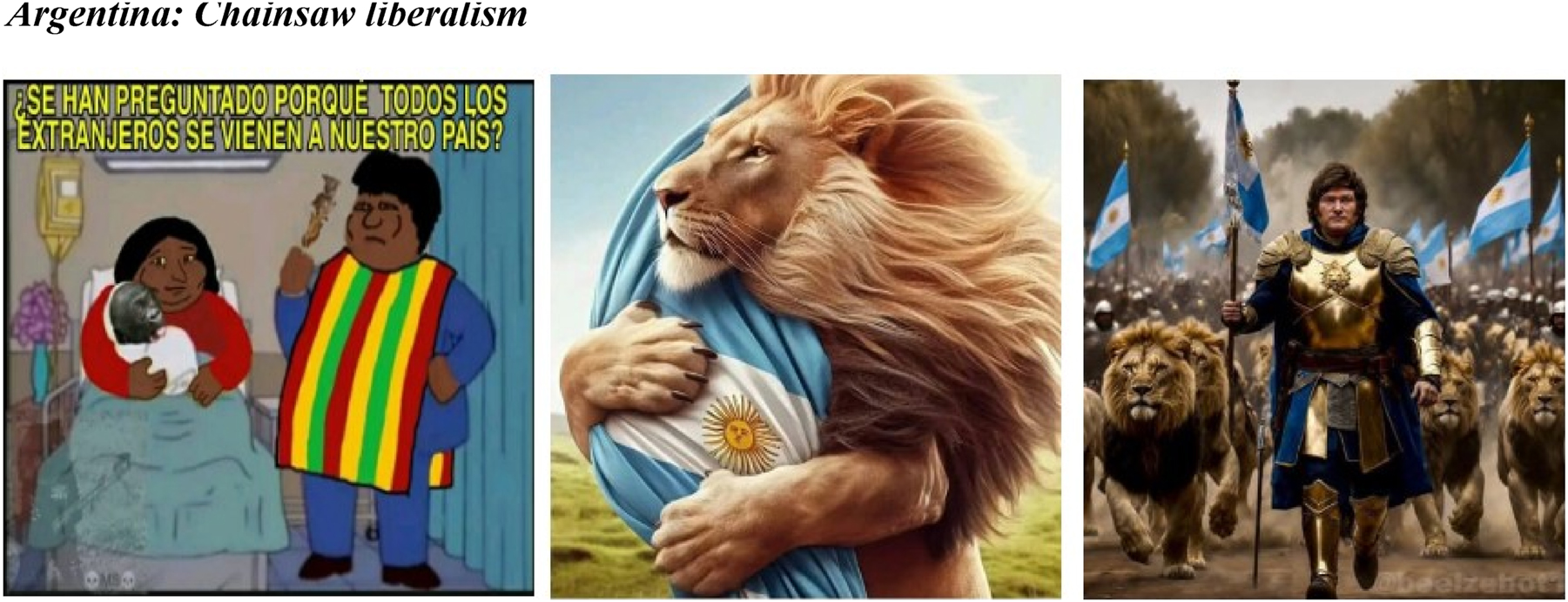

Images extracted from Telegram. Author’s collage. The image on the left has been produced manually, while the other two images (the central one and the one on the right) have been produced through a Prompt in Generative AI. The image on the left shows a caricatured and animalised immigrant couple, showing their child as if he were a monkey, dehumanising the immigrant family. The message reads “Have you ever wondered why all foreigners come to our country?” The message shows the racist trait of this political project in Argentina. The central image shows a lion embracing the Argentinean flag. Milei has been called “The Lion” during the campaign. Finally, the image on the right shows Milei dressed as a Roman warrior accompanied by an army of lions, paying tribute to his slogan “I have come to turn lambs into lions”.

In Argentina, both generative AI and manually produced memes reflect a strong focus on nationalistic and populist imagery tied to Javier Milei and his ideological narratives. The memes portray Milei through medieval and lion imagery, glorifying him as a national saviour, while opponents are ridiculed as immoral or corrupt. This symbolic contrast seeks to mobilise nationalist pride and anti-Peronist sentiment. In the “Javier Milei Official” and “Milei President 23–27. Long Live Freedom” Telegram groups, the percentage of AI-generated images is relatively low – 4.86 % and 3.53 %, respectively. However, these AI-generated visuals are effective in portraying Milei as a heroic, lion-like figure, symbolising power and the fierce independence associated with his brand of anti-establishment nationalism, often dubbed “chainsaw liberalism.” Themes such as medieval heroism, patriotism, and the defense of traditional values are recurrent, projecting Milei as a defender of the homeland against both internal and external threats. These images incorporate a visual plasticity that humanises him as both accessible and strong.

In contrast, the majority of manually created memes (95.14 % and 96.47 % in the same groups) take a more confrontational stance, often depicting Milei as Argentina’s “eccentric savior” while ridiculing traditional media and glorifying social networks as beacons of free expression. This attack on mainstream media coincides with a larger strategy to paint Milei’s opposition, such as Kirchnerist and Peronist groups, as enemies of progress or “enemies of civilization,” casting them as threats to national and religious morality.

Reactions to these images on Telegram reveal how plasticity plays an important role in the construction of political polarisation. In response to the images produced with Generative AI, people react with messages of support and reinforcement for these symbols: “Let’s all go with the lion”, exclaims one member of the group. “Milei is a national hero”, says another, “Milei is a Templar”, says another fascinated supporter. On the other hand, when faced with images that show the enemy through manual plasticity, users respond by saying “Garbage out” or react with symbols of laughter to the vexations and humiliations of the political opposition.

Moreover, these same messages are heard at demonstrations, showing the capacity of memetic communication to circulate and adapt. “Milei is a beast, a lion who will save us from those wolves in sheep’s clothing”, says a supporter at the closing rally. “Milei is coming to transform each one of us from lambs into lions”, explains Juan, a young computer scientist who supports Milei, in an interview. “Look at all these thieves. Argentina could feed 400 million people. Whoever is over 18 and is still a socialist has no heart”, comments Lucía, a middle-aged woman who owns a small cosmetics company, in a phone call (Montage 2).

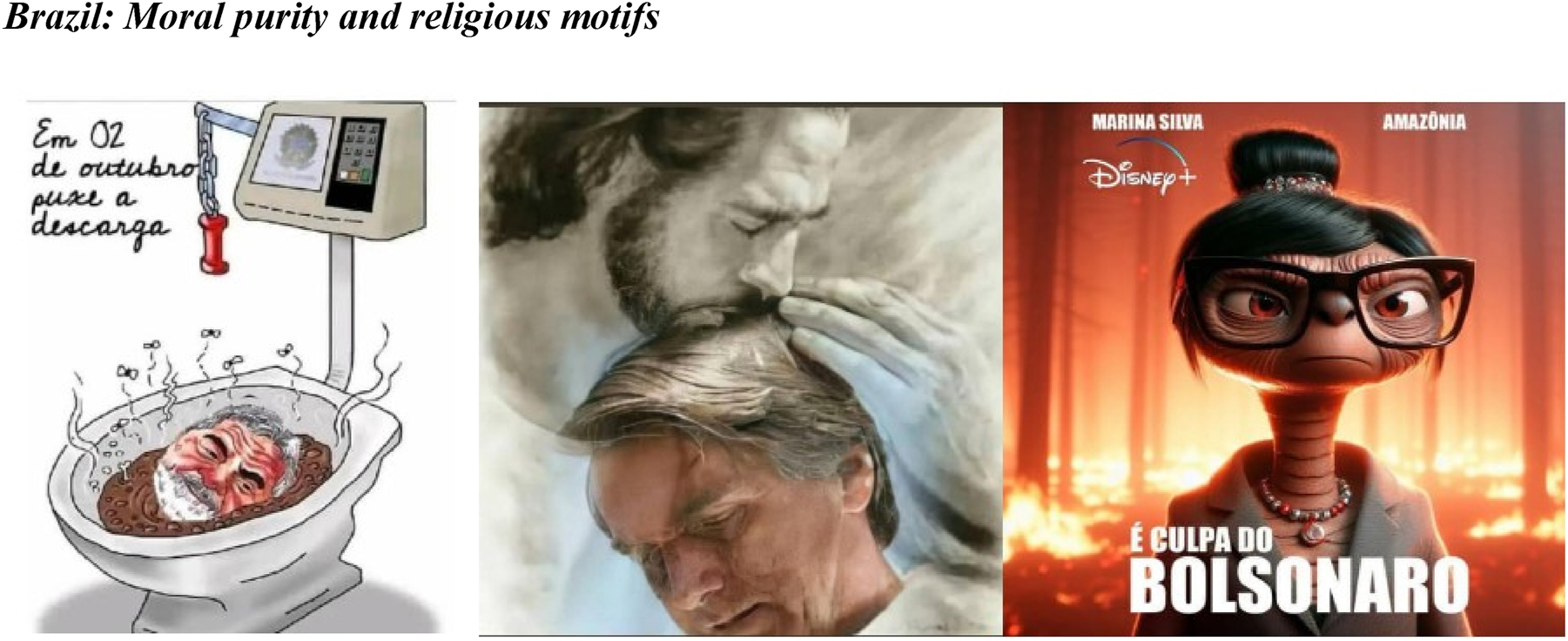

Images extracted from Telegram. Author’s collage. The image on the left has been produced manually, while the other two images (the central one and the one on the right) have been produced through a Prompt in Generative AI. The image on the left shows Lula’s head in a toilet full of excrement. The message says “on 2 October press flush”, in a scatological appeal to the electoral process. In the central image we observe Bolsonaro being kissed by Jesus, receiving his blessing. It shows the divine and theological trait of his political ideology. In the image on the right we see the minister Marina da Silva represented as a grotesque creature, animalised. The minister, an indigenous woman, thus suffers the racism and sexism of the Bolsonarist project.

In Brazil, particularly within the “Carlos Bolsonaro – Official Account” and “Bolsonaristas” Telegram groups, the discourse is marked by a significantly lower usage of AI in meme production – 2.78 % and 0.51 %, respectively – reflecting a stronger reliance on traditional meme production techniques. Lula is tinted red, in reference to accusations of alcoholism; Marina Silva is represented as an alien-like creature, alluding to her environmental policies; and Bolsonaro is embraced by Jesus in a collage that underlines divine legitimacy. Despite the low AI-generated content, manually created memes are highly potent, emphasising themes of conservative purity associated with childhood, national pride, and the symbolic centrality of the Brazilian flag. Bolsonaro is consistently portrayed as Brazil’s redeemer, symbolising a liberation from “degeneracy” attributed to opposition figures, notably Lula, who is demonised through representations of moral decay, perversion, and even dehumanisation. These recurring motifs of “good versus evil” draw on childhood innocence and Christian moralism, reinforcing Bolsonaro as a paternal figure defending the Brazilian nation.

In AI-generated imagery, the emphasis shifts to a more stylised presentation of Bolsonaro’s leadership, often portraying him as a divinised figure representing the will of the people alongside the Brazilian army. These memes evoke a corporate branding of national values, subtly aligning Bolsonaro’s image with military and patriotic symbolism. Additionally, the figure of the panther appears as a recurring motif, embodying resilience and aggressiveness, a direct challenge to opposition figures who are often depicted as chaotic or morally degraded beings.

The comments to these images show a high degree of aggression towards the opponent. The images produced with Generative AI and heroising Bolsonaro are followed by comments that unify the Bolsonarist community: “All together with the patriot”, writes one user. “Myth, let’s not forget him”, replies another member of the chat. However, most of the messages reacting to the images refer to the attack and degradation of the enemy: “That vagrant should have been killed”, “Shot in the head”, “the country is filling up with vermin”. These are some of the phrases that resonate in reaction to the memes that express duality and present an enemy.

The messages at the rallies show again how communication is interconnected, and both online and offline spaces feed back into each other. “I support Bolsonaro because he supports the family. He supports our children. He is against communism, against corruption. I support him because he is a patriot, because he believes in God”, a black man explains to me at the campaign closing in the Sao Gonçalo neighbourhood. “Globo Lixo”, exclaims a woman with a flag tied to her head (Montage 3).

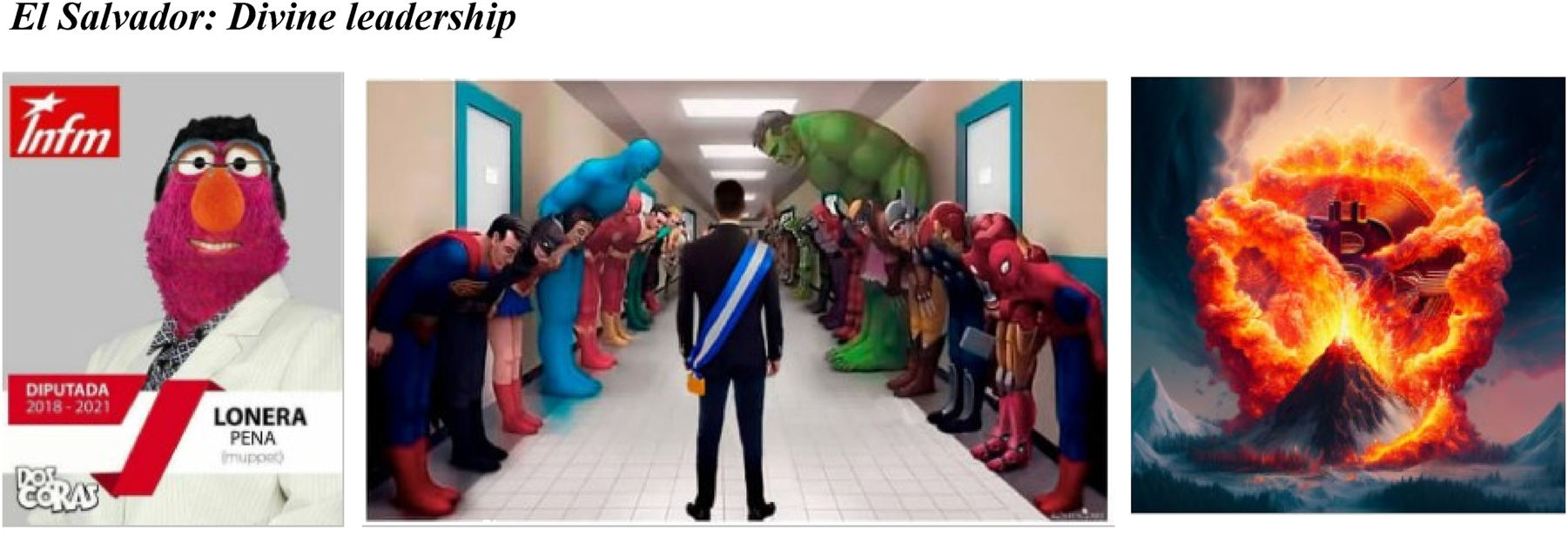

Images extracted from Telegram. Author’s collage. The image on the left has been produced manually, while the other two images (the central one and the one on the right) have been produced through a Prompt in Generative AI. The image on the left shows a representation of the Salvadoran congresswoman and ex-guerrilla Lorena Peña, who is caricatured and transformed into a cartoon. Thus, the political opponent, as well as her party, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), is trivialised and ridiculed. In the central image, we see President Nayib Bukele, standing firm in front of the admiring and respectful inclination of various Marvel and DC action figures. Representations of these super-heroes are common in the political communication of far-right populisms. These representations collaborate in the construction of Bukele’s heroism and superhuman leadership. Moreover, it supports and strengthens his hard punitive discourse, as the characters are known for their moral dichotomisation of good versus evil. In the image on the right we see a volcano exploding with fire, and in the flames the “B” of Bukele. The name of the leader does not need to be said, it is implied. And his appearance is represented as a transformative explosion. The typography of the “B” also coincides with Bitcoin, the cryptocurrency that El Salvador has formalised as co-official.

El Salvador’s Telegram groups, “Nuevas Ideas” and “Nayib Bukele,” provide a particularly high rate of generative AI use in political memes (6.16 %, the highest among the three countries analysed). AI-generated images depict Bukele as a monarch or messiah leading the nation, while manual memes attack the press and opposition. Together, these visuals reinforce a cult of the leader rooted in punitive populism. The timing of this data collection, spanning December 2023 to February 2024 around the single-round election, highlights how AI-generated images play a role in constructing Bukele’s image as a mass hero and “king-like” figure. These images reinforce a narrative of a prosperous and secure El Salvador, symbolically linked to Bukele’s leadership. AI-generated memes depict El Salvador as a nation on the rise, with Bukele at the helm, and emphasise the perceived growth in tourism, improved security, and economic stability under his administration. These digital portrayals contribute to the idea of a “divine leader” and bolster the vision of a reformed, safer El Salvador, appealing both domestically and internationally.

Manual memes in El Salvador amplify this narrative by attacking the press and political opposition while celebrating patriotic values and national sovereignty. Themes of punitive populism and social welfare are prominent, with Bukele presented as the singular force for change, strengthening the notion that El Salvador’s prosperity is inseparably linked to his leadership. Attacks on the press are frequent, as are appeals to anti-feminist morality and religious values, suggesting that Bukele’s supporters view these as integral to preserving the country’s newfound stability. Opposition figures are often demonised, marked as threats to progress and security, underscoring Bukele’s role as the protective, paternal figure defending national interests.

The hegemony of Bukelismo can be confirmed by the fact that most of the images and reactions are directed at the cult of the leader. “The best president in Latin America. Of the world”, comments one supporter. “He has saved us all. He is Jesus”, comments another. However, attacks on the opposition also occur: “International NGOs are the evil of the world”, exclaims another participant. On the streets this cult of the leader is also reflected. “The coolest president”, a member of his campaign tells me. “Young, brave, energetic”, adjectivizes another member. The memory of insecurity is latent, with a recurrent comparison of the present security situation with the pandillas of the past: “In the old days, where we are, we wouldn’t have been able to pass through here, or we would have been kidnapped or killed”, says another campaign member.

Across all three countries, the distinct patterns in meme production and the choice of themes reveal a consistent strategy of elevating leaders as near-mythical protectors while marginalising opposition figures. In Argentina, the prevalence of medieval and lion symbolism contributes to a nationalistic image of a powerful hero defending traditional values, whereas in Brazil, the use of childhood and religious motifs underscores Bolsonaro’s appeal as a conservative guardian of moral purity. El Salvador’s approach, marked by high AI use, shifts toward constructing a visionary image of prosperity and security, portraying Bukele as a benevolent leader guiding the nation to international recognition.

While manual memes in each country are more aggressive and emphasise ridicule, AI-generated memes tend to employ polished visuals, aesthetic appeal, and a somewhat restrained tone, enhancing the leaders’ legitimacy. These findings underscore the role of memes as tools for political mobilisation, exploiting national symbols, religious sentiments, and historical narratives to cultivate emotional investment in the leaders, ultimately reinforcing ideological polarisation. In all three contexts, fact-checking institutions exist but lack sufficient reach to counter viral meme circulation. In contrast, examples such as maldita.es in Spain show how systematic fact-checking can help address misinformation.

6 Final Notes: Challenges of Memetic Communication and Generative AI in the Latin American Context

The advent of new generative artificial intelligences is revolutionising meme production, significantly altering how political narratives are shaped in Brazil, El Salvador, and Argentina. These tools simplify the creation process by enabling users to generate memes using prompts or textual descriptions, eliminating the need for prior knowledge of design programs like Photoshop or GIMP. As a result, meme creation has become more accessible, allowing a broader audience to participate in content production. This democratisation of meme generation enriches public debate by increasing the diversity and quantity of political imagery circulated during electoral campaigns. However, it also intensifies the saturation of messages and competition for voters’ attention, fostering an environment ripe for polarisation.These dynamics also unfold in highly unequal societies, where limited access to education and media literacy exacerbates susceptibility to manipulative content (Bakir and McStay 2018).

AI-generated memes contribute to shaping political discourse by distilling complex ideas into easily digestible visuals. While this can enhance engagement, particularly among younger demographics attuned to digital communication, it also risks oversimplifying political issues and reinforcing stereotypes (Cesarino 2020). In the context of Latin America, where political instability and economic inequality are prevalent, these effects can exacerbate existing divisions. The highly concentrated media environments in countries like Brazil, El Salvador, and Argentina mean that social media and memes serve as critical outlets for alternative viewpoints, but they also facilitate the rapid spread of misinformation.

The ease with which AI-generated memes can be created poses significant challenges. Malicious actors can exploit these tools to produce deceptive or incendiary content, manipulating emotions and polarising opinions on a large scale. This dynamic is particularly concerning in post-colonial contexts, where economic and social inequalities contribute to disparities in access to technology and media literacy. Populations with lower digital literacy are more susceptible to the persuasive power of AI-generated memes, especially those designed to exploit cultural and social fault lines.

Furthermore, in environments characterised by high political instability and public mistrust in institutions, AI-generated memes can erode trust in democratic processes. Rapid dissemination of emotionally charged misinformation can destabilise governments and influence elections. This situation calls for a multifaceted approach to address the challenges posed by AI-generated political memes. Enhancing media literacy programs is essential for empowering citizens to critically evaluate the content they encounter online. Strengthening regulatory frameworks to ensure transparency and accountability in AI’s use in political campaigns will be crucial in mitigating the risks associated with misinformation.

In conclusion, while AI-generated memes present exciting opportunities for political engagement in Brazil, El Salvador, and Argentina, they also pose significant challenges that require careful consideration. The balance between innovation and ethical responsibility will be key in harnessing the benefits of these technologies while addressing their potential downsides. Ultimately, fostering a more pluralistic and independent media environment will ensure a more diverse and informed public discourse, supporting the development of stronger and more resilient democracies in these countries.

Funding source: British Academy /Royal Society/ Newton International Fellowship

Award Identifier / Grant number: NIF22\220263

Acknowledgments

The empirical data used in this article were collected as part of my Newton International Fellowship project Discourse Polarisation: The Memetic Violence of the Latin American Right-Wing Populisms (NIF22\220263). I gratefully acknowledge the support of the British Academy and the Royal Society, as well as the institutional backing of the Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies (CLACS) at the Institute of Languages, Cultures, and Societies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, where this postdoctoral research was carried out. The analysis and interpretation of these materials have also benefited from the work conducted within the COMMRADES research group and the project “Memes y representaciones de género en la comunicación política española” (URJC, 2024/SOLCON-137941), which provided an additional framework for discussion and refinement of the findings presented here.

-

Ethical approval: The data analysed in this article form part of a research project that was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Advanced Study, University of London, as part of Gabriel Bayarri’s British Academy Fellowship. The project was submitted under the code NIF22\220263 and received ethical clearance with the reference SASREC_2122-912-F. Accordingly, all research activities were conducted in full compliance with the institution’s standards regarding integrity, confidentiality, and risk minimisation.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the Newton International Fellowship project Discourse Polarisation: The Memetic Violence of the Latin American Right-Wing Populisms (NIF22\220263), funded by the British Academy and the Royal Society. The Fellowship provided resources for conducting fieldwork and for the systematic collection of visual and digital materials used in this study.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Author contribution: The author confirms sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

References

Ahmed, S. (2013). The cultural politics of emotion. Routledge, London.10.4324/9780203700372Suche in Google Scholar

Ardévol-Abreu, A. (2022). Influence of fake news exposure on perceived media bias: the moderating role of party identity. J. Int. Commun. 16: 22–44.Suche in Google Scholar

Askanius, T. (2021). On frogs, monkeys, and execution memes: exploring the humor-hate nexus at the intersection of Neo-Nazi and alt-right movements in Sweden. Televis. N. Media 22: 147–165, https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420982234.Suche in Google Scholar

Bakir, V. and McStay, A. (2018). Fake news and the economy of emotions. Digital Journalism 6: 154–175, https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1345645.Suche in Google Scholar

Bayarri, G. (2022). The rhetoric of the Brazilian far-right, built in the streets: The case of Rio de Janeiro. The Australian Journal of Anthropology 33: 395–411, https://doi.org/10.1111/taja.12421.Suche in Google Scholar

Bayarri, G. and Fernández-Villanueva, C. (2025a). Funny weapons”: The norms of humour in the construction of far-right political polarisation. Social Inclusion 13, https://doi.org/10.17645/si.10211.Suche in Google Scholar

Bayarri, G. and Fernández-Villanueva, C. (2025b). Violence, hate speech, and polarisation in far-right political influencers in Spain. Javnost – The. Public 32: 92–114, https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2025.2469032.Suche in Google Scholar

Billig, M. (2019). Le nationalisme banal. Presses Universitaires de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve.Suche in Google Scholar

Bizberge, A. and Segura, M. (2020). Los derechos digitales durante la pandemia Covid-19 en Argentina, Brasil y México. Revista de Comunicación 19: 61–85, https://doi.org/10.26441/RC19.2-2020-A4.Suche in Google Scholar

Burdett, C. (2003). Italian fascism and utopia. Hist. Hum. Sci. 16: 93–108, https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695103016001008.Suche in Google Scholar

Campos Mello, P. (2020). A máquina do ódio: notas de uma repórter sobre fake news e violência digital. Companhia das Letras, São Paulo.Suche in Google Scholar

Cannon, B. (2016). The right in Latin America: elite power, hegemony and the struggle for the state. Routledge, London.Suche in Google Scholar

Cesarino, L. (2020). How social media affords populist politics: remarks on liminality based on the Brazilian case. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada 59: 404–427, https://doi.org/10.1590/01031813686191620200410.Suche in Google Scholar

Colussi, J., Toscano, G.B., and Gomes-Franco e Silva, F. (2023). ‘We swear to lay down our lives for the fatherland!’: bolsonaro as influencer and agent of political polarization. Análisis Político 106: 113–132, https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/anpol/article/view/111044.10.15446/anpol.v36n106.111044Suche in Google Scholar

Dynel, M. and Messerli, T.C. (2020). On a cross-cultural memescape: switzerland through nation memes from within and from the outside. Contrastive Pragmatics 1: 210–241, https://doi.org/10.1163/26660393-bja10007.Suche in Google Scholar

Fernández-Villanueva, C. and Bayarri, G. (2021). Legitimizing hate and political violence through meme images: the bolsonaro campaign. Commun. Soc. 34: 449–468, https://doi.org/10.15581/003.34.2.449-468.Suche in Google Scholar

Forti, S. (2021). Extrema derecha 2.0: qué es y cómo combatirla. Siglo XXI de España Editores, Madrid.Suche in Google Scholar

Gallardo-Paúls, B. (2018). Tiempos de hipérbole: inestabilidad e interferencias en el discurso político. Tirant Humanidades, Valencia.Suche in Google Scholar

Hakoköngas, E., Halmesvaara, O., and Sakki, I. (2020). Persuasion through bitter humor: Multimodal discourse analysis of rhetoric in internet memes of two far-right groups in Finland. Soc. Media Soc. 6, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120921575.Suche in Google Scholar

Hall, S. (2007). Richard Hoggart, the uses of literacy and the cultural turn. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 10: 39–49, https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877907073899.Suche in Google Scholar

King, E. (2024). Gaming race in Brazil: video games and algorithmic racism. J. Lat. Am. Cult. Stud. 33: 149–165, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569325.2024.2307540.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, G. (2002). Moral politics: how liberals and conservatives think. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.10.7208/chicago/9780226471006.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Montoya, A. (2018). The violence of democracy: political life in postwar El Salvador. Springer, New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Musolff, A. (2016). Political metaphor analysis: discourse and scenarios. Bloomsbury, London.Suche in Google Scholar

Parker, I. (2019). Memesis and psychoanalysis: mediatizing donald trump. In: Bown, A. and Bristow, D. (Eds.). Post memes: seizing the memes of production. Punctum Books, Santa Barbara, CA, pp. 353–366. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv11hptdx.18.10.2307/j.ctv11hptdx.18Suche in Google Scholar

Parrot, S. and Hopp, T. (2020). Reasons people enjoy sexist humor and accept it as inoffensive. Atl. J. Commun. 28: 115–124, https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2019.1616737.Suche in Google Scholar

Ross, A.S. and Rivers, D.J. (2017). Digital cultures of political participation: internet memes and the discursive delegitimization of the 2016 U.S. presidential candidates. Discourse Context Media 3: 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2017.01.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Shifman, L. (2014). The cultural logic of photo-based meme genres. J. Vis. Cult. 13: 340–358, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412914546577.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, C. (2019). Weaponized iconoclasm in internet memes featuring the expression ‘fake news. Discourse Commun. 13: 303–319, https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481319835639.Suche in Google Scholar

Tortorici, Z. and Fernández-Galeano, J. (2023). Introduction: the politics of obscenity in Latin America. J. Lat. Am. Cult. Stud. 32: 539–547, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569325.2024.2311661.Suche in Google Scholar

Zafra, R. (2017). Redes y posverdad. In: Ibáñez, J. (Ed.). En la era de la posverdad. Calambur, Madrid, pp. 62–69.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Situated Knowledge in Motion: Reconsidering Urban Feminist Methodologies

- Feminist Worldmaking Through Collective Curating: Kaleidoskop’s Relational Urban Aesthetics

- Tactical Spatial Interventions: Design for Gendered Spatial Justice in Peri-Urban Victoria, Australia

- Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- “A Good Bandit is a Dead Bandit”: Memetic Violence and AI on the Latin American Right-Wing Populism

- Violence(s): An Introduction

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Critical Hope in South African Higher Education: Using a Theory of Change Approach for Mid-Project Reflection on a Student-Staff Partnership Programme

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

- Metamodern Oscillation and the Artisan Ethic: The Poetics and Practice of the Band Adamlar

- Idiomaticity in the English Subtitling of Jordanian Movies on Netflix: A Cultural Analysis

- Cameras Off: Cultural and Social Influences on Students’ Webcam Use in Online Learning

- A Tale of Two Houses: Returning Ghosts and Hammad’s Appropriation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet

- Rewriting Women in the Qur’an: Gender, Ideology and Translation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Situated Knowledge in Motion: Reconsidering Urban Feminist Methodologies

- Feminist Worldmaking Through Collective Curating: Kaleidoskop’s Relational Urban Aesthetics

- Tactical Spatial Interventions: Design for Gendered Spatial Justice in Peri-Urban Victoria, Australia

- Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- “A Good Bandit is a Dead Bandit”: Memetic Violence and AI on the Latin American Right-Wing Populism

- Violence(s): An Introduction

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Critical Hope in South African Higher Education: Using a Theory of Change Approach for Mid-Project Reflection on a Student-Staff Partnership Programme

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

- Metamodern Oscillation and the Artisan Ethic: The Poetics and Practice of the Band Adamlar

- Idiomaticity in the English Subtitling of Jordanian Movies on Netflix: A Cultural Analysis

- Cameras Off: Cultural and Social Influences on Students’ Webcam Use in Online Learning

- A Tale of Two Houses: Returning Ghosts and Hammad’s Appropriation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet

- Rewriting Women in the Qur’an: Gender, Ideology and Translation