Abstract

This article presents a co-designed, transdisciplinary movement methodology for exploring and evidencing vulnerability with children, a central element of upstream violence prevention. The methodology blends the authors’ lived experience and professional knowledge of urban violence prevention, dance movement psychotherapy, and community-centred practice. We also build on the growing use of “visceral” artistic and kinetic methods to overcome the shortcomings of traditional talk-based methods in both social science and therapeutic settings. We first review the theoretical underpinnings of our methodology, then offer autoethnographic reflections on navigating vulnerability in our own lives and how those experiences shaped our work, and finally recount what the methodology looked and felt like in practice, focusing on the pilot we delivered in 2024. The 30 children aged 10–12 who participated reported feeling at ease, energised, and connected with each other afterwards, all feelings that counteract the anxiety, fear, and isolation that children often experience in the transition from primary to secondary school. We undertook this work in a London borough where preventing and mitigating violence affecting young people has been a strategic priority since 2009.

When we are no longer still, the world lives differently.

–Erin Manning

1 Introduction: A Moving Target

Moments of transition in children’s lives – from primary to secondary school and then from secondary school to further education or work – can be destabilising. Children without overlapping infrastructures of support to anchor themselves during these periods can end up adrift and exposed (Erikson, 1968). As a result, schools, community organisations, and local authorities in the UK increasingly recognise that preventing individual, family, and community harm necessitates early and consistent engagement in children’s lives, including reliable investment in “transitional safeguarding.”

Transitional safeguarding is the work to ensure that children and young people do not fall through the cracks as they progress through developmental transitions toward adulthood, particularly from primary to secondary school and then from secondary school into work or further education (Cocker & Cooper, 2022). As children move into adolescence, the part of their brain that controls impulses and assesses risks undergoes neurodevelopmental changes (Blakemore & Mills, 2014). This period is also when self-esteem and peer relationships become the core of a young person’s identity (Erikson, 1968). As children begin to navigate more independence when they graduate from primary to secondary school, some of them may experience social isolation and exploitation by peers. This can increase their vulnerability, including the likelihood that they might endure or use violence (Nind et al., 2011). Children with protected characteristics and/or experience in the care, criminal justice, and other state systems can be especially vulnerable (Holmes & Smale, 2018).

UK political and economic policies to slash spending on public services to bring down government debt have compelled the prioritisation of crisis response whilst eroding institutional and societal capacity for prevention (Arrieta, 2022; Bray et al., 2024). As part of this, austerity has undercut the reliability of funding for transitional safeguarding. Diminished resources and hopelessness or resignation in the face of “polycrisis” and “permacrisis” – unending catastrophic situations springing from everything, everywhere, all at once (Brown et al., 2023; Lawrence et al., 2024) – have reduced the public sector’s ability and willingness to try new things to confront violence affecting young people. This may be the case even when existing efforts routinely come up short (Stevens et al., 2025).

In 2005, before austerity, Scotland established a Violence Reduction Unit and adopted a “public health approach” to combating violence. The unit pursued targeted “treatment” grounded in an evidence-based understanding of the causes of violence and its contagion (About Us, 2022). This shift was driven in part by reports from the World Health Organization and the United Nations in the 2000s that singled out Scotland, and Glasgow in particular, as the murder capital of Europe, a consequence of escalating gang violence and young men carrying knives (Hassan, 2020). Toward the end of the 2010s, the UK government increasingly began referring to “epidemic” levels of “serious youth violence,” which they defined as homicides and knife and gun crime (Ojo et al., 2019; Serious Violence Strategy, 2018). In committing to the public health approach at a national level, in 2019, the Home Office funded the establishment of 19 additional local violence reduction units across the UK.

Many types of violence that young people experience, however – including stigma, suspicion, exclusion, adultification, gentrification, and more – fall outside the definition of serious youth violence. They are also often legal, which makes them hard to track, quantify, and measure (Nixon, 2011; Pain, 2018). Even for types of violence that are not legal, like adolescent domestic abuse and criminal and sexual exploitation, reporting mechanisms typically require accusers to be explicit about what happened to them, and accusations of “bad character” can be unfairly deployed against accusers in legal proceedings (Ofer et al., 2025). When children and young people report violence, they may use words like “weird,” “uncomfortable,” and “not ok” to describe their experiences, or there may not be a specific incident they can point to, but rather an undesirable “vibe” (Rabe, 2023). This is not uncommon. Sexton and her colleagues remind us that violence is “visceral”: “relating to, and emerging from, bodily, emotional and affective interactions with the material and discurisve environment” (2017, p. 200). In other words, violence resonates in our bodies before we try to make sense of it through our minds and articulate it in words (Hayes-Conroy, 2017; Sweet & Ortiz Escalante, 2015). That sequence conflicts with standard protocols for evidence.

Sweet underlines “the opportunity of creativity to produce pleasure, laughter, as well as to see and sense power” (2017, p. 202). In different ways, arts-based methods enable both of us to step out of line in our fields – to overcome the shortcomings of traditional methods for exploring and evidencing forms of violence that are otherwise hard to capture. Between 2023 and 2024, we co-designed a movement methodology to explore vulnerability with children in transition as an alternative way to know, resist, and prevent violence affecting young people. We piloted the methodology with children living and studying inm Lambeth, the South London borough where Ariana was employed.

Though our work was part of a broader programme to understand how violence that is hard to see and harder to count affects young people, we focus here on developing and piloting the methodology and how it benefited the children who worked with us. To that effect, we begin by reviewing the theoretical underpinnings of our methodology. Then we offer personal reflections on navigating vulnerability in our own lives and how those experiences shaped our work. Finally, we explain what the methodology looked and felt like in practice when we piloted it with 30 children in February 2024. Though every borough has its own rhythms, resources, streets, and stories, we believe our methodology may be applicable to other contexts since vulnerability in childhood transitions is universal. We are seeking opportunities to try it out elsewhere with other groups of people.

2 Taking a Step Back: The Trouble With Structural Violence

Why is structural violence less of a policy priority than direct violence, especially for violence affecting children? Rex writes about “hierarchies of evidence” in decision-making in UK local government: “In a context in which evidence is unavailable (or undesirable) and local authorities lack the resources to obtain it, decisions are made based on common-sense notions of what ‘makes sense’ or ‘feels right’” (2020, p. 197). When systems are unable to parse evidence or evidence cannot be categorised, it is often omitted. Without a systematic evidence base, planning and resourcing prevention is difficult to justify, especially when budgets are tight. This can allow harm to continue.

In response to higher levels of youth violence compared to most other London boroughs, preventing and mitigating violence affecting young people has been a priority in Lambeth since 2009 (Lambeth Made Safer, 2020; Lambeth Made Safer Violence against Women and Girls Strategy, 2021; Safer Lambeth Partnership Strategy, 2023). In 2023, the borough’s community safety partnership strategy committed the local authority, the Metropolitan Police, the National Health Service, the London Fire Brigade, and His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service to accessible and inclusive community engagement that centres victims and survivors, involves perpetrators, and recognises that violence causes both individual and social harm. The partnership also affirmed that work to prevent violence should have a public and provocative impact (Safer Lambeth Partnership Strategy, 2023, pp. 9–10).

Galtung wrangled with how to classify and define violence in his 1969 article, identifying and naming structural and personal/direct violence. Structural violence is a consequence of persistent inequity, grounded in exploitation and built into the political and economic social order. It is an outgrowth of asymmetric power dynamics and a risk factor for both chronic and acute violence (Locke et al., n.d.). Structural violence, writes Galtung, “may be seen as about as natural as the air around us” (1969, p. 173). It normalises physical and emotional suffering and distress, including patterns of adverse health outcomes and poverty (Bourgois, 2001; Farmer, 2000). Sometimes there are incidents that break through this “ordinary” suffering so that the normal becomes perceptible, “like an enormous rock in a creek, impeding the free flow, creating all kinds of eddies and turbulences” (Galtung, 1969, p. 173).

In contrast, direct or personal violence is always visible because it destroys all or part of the physical body, as in murder or maiming (Galtung, 1969). The physicality of this violence makes it easier to understand, count, and combat. Sometimes an act of direct violence can make structural violence more visible by revealing the peril of continued marginalisation, but sometimes it can distort prevention work. The discourse on violence in US schools, for example, centres mass shootings whilst mostly ignoring indirect violence (Indar et al., 2023). Likewise, the on-going “state of exception” under President Nayib Bukele in El Salvador has facilitated the mass incarceration of young men from poor urban neighbourhoods, but there is less focus on how the policy affects everyone else. This includes the women and girls who bear the burden – in time, in money, and in individual and collective exposure to risk – of keeping their families and communities afloat and their imprisoned relatives alive in the absence of adequate food, clothing, or medicine from the state (Keuleers & Mulenga Hornsby, 2022; Zulver & Méndez, 2023).

In 1990, Galtung added a third type of violence to his classification, cultural or symbolic violence. This violence is the mechanism by which “direct and structural violence look, even feel, right – or at least not wrong” (1990, p. 291). This feeling of right-ness is based on the extent to which violence is not recognised as violent, “a violence which is wielded precisely inasmuch as one does not perceive it as such” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992/2005, p. 168). Living amidst unacknowledged violence – which stigma, suspicion, exclusion, adultification, and gentrification often are – can breed dread, denial, distrust, and disengagement (e.g., Allen, 2022; Davies, 2019; Hume & Wilding, 2020; Stel, 2016). This is especially true once violence becomes chronic, which is to say persistent, recurring, embedded, and routine (Pearce, 2007). Billingham and Irwin-Rogers depict the “fear and despair” of children in British communities affected by chronic youth violence (2022, p. 4):

Children approaching adolescence can be deeply frightened of their own impending teenage years, assuming—rightly or wrongly—that they will inevitably feature violence and danger. They can fearfully anticipate having to make terrible decisions between rival groups of their peers, or having to negotiate the horrible catch-22 of choosing between the illusory safety of gang membership, on the one hand, and the potentially fragile solitude of avoiding affiliation with any local grouping, on the other.

When violence goes unrecognised, it becomes harder to remedy and prevent recurrence (Baumann & Yacobi, 2022). Harm can grow roots through repetition (Bourgois, 2001), transforming violence into an independent variable and a driver of further violence (Bergmann, 2020). Moreover, marginalisation can diminish the credibility of its victims (Das, 2006; Spivak, 1988) and, for better or for worse, society already tends to view children as unreliable narrators of their own lives (Spiteri, 2024). Violence affecting children, then, may be doubly illegible: normalised by its inscription in everyday practices and silenced because of who it harms. Because of the UK’s prioritisation of direct or personal violence in its definition of serious youth violence, and because older teenagers and young adults are statistically more likely to commit crimes than children are, work to prevent structural violence affecting children often garners less attention and support.

To be clear, following from the work of Das and Fassin (2021), we view violence prevention as “both/and.” Both acute and structural and chronic violence harm young people of all ages and the neighbourhoods where they live, study, work, and play, so both types of violence demand our attention and action. What we see in practice, however, is that difficulties in recognising structural and chronic violence as violence mean that most prevention work targets acute violence (Locke et al., n.d.). In our separate fields, we address this imbalance by integrating visceral artistic and kinetic methods into our work – which are better suited to “materialising the invisible” (Lyon, 2020) – alongside more traditional talk-based approaches. The next section explores some of our personal encounters with vulnerability and art, and how we came to understand both as key to preventing violence affecting children.

3 Getting Off on the Wrong Foot: Reflecting on Personal Experience

Our shared interest in vulnerability and creative methods stems from both of us muddling through personal and professional challenges earlier in our lives. Ariana is a researcher and urbanist who designs creative and community-led methodologies to prevent structural and chronic violence and drive organisational change. When she undertook extended fieldwork in El Salvador for her PhD in 2018, she had already been working on and amongst violence for more than a decade. Nonetheless, the fieldwork was bruising. Reflecting on that time years later (Markowitz, 2025), she wrote that:

the stories and images of violence were coming fast and furious from every direction—during my data collection but also with every taxi driver and market trader who asked me what I was doing in the city. Normally an extrovert, I was turning inward, behaving erratically, and haunted in my sleep. After a particularly gruesome incident, I stayed up for two consecutive nights to avoid nightmares.

That Ariana was working on violence with vulnerable people compounded the ethical ramifications of having inadequate emotional reinforcements for herself (San Roman Pineda et al., 2023). To regain stability and the capacity to do rigorous and careful research, she embarked on an on-going process of learning and imagining alternatives (Markowitz, 2019; Markowitz & Olmos Herrera, n.d.). A core part of that process has been becoming attuned to what deteriorating mental health feels like in her body to be better able to back away from the brink rather than plunging into the abyss. That awareness, “more than anything I’ve read or any training I’ve taken…has made me a more exacting, creative, and human researcher” (Markowitz, 2025).

Also in El Salvador, Ariana found that traditional word-based social science methods for data collection were insufficient to understand how residents metabolised the structural and chronic conditions that made San Salvador, the capital, a “dangerous city” (Markowitz, 2022). In dozens of interviews, her research participants responded to her questions with confusion, amusement, frustration, and disbelief. People often asked why she wanted to discuss things that did not matter. They talked in circles – for example, noting that they felt safe when armed security personnel were standing guard, whilst blaming those same security guards for being in cahoots with criminalised actors – and then grew indignant or morose mired in their own contradictions. In hopes of salvaging her data collection, Ariana began experimenting with arts-based methods. Taking advantage of her existing links with the city’s artistic community, she convened a workshop with filmmakers, theatre-makers, photographers, and dancers, and invited them to bring a sample of their work in which they gave fear a physical form. What might a photographer capture to convey their own unease to someone unfamiliar with where they are? she asked participants. What kinds of movements and filmmaking techniques express dread, terror, and anxiety?

For the first time in Ariana’s fieldwork, the participants in this workshop produced data on what fear looked, sounded, and felt like and how those feelings shaped the city: how people moved around, who they talked to, how they read their surroundings, and how they chose where to live, work, study, and play. The workshop made clear that “[t]he body is the vehicle of being in the world” (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 94): if fear is one type of visceral encounter with our surroundings, then understanding how fear makes a city requires “visceral methods.” Such methods focus on how bodies interact with their surroundings, moulded by sensations, moods, and states of being (Hayes-Conroy & Hayes-Conroy, 2015, p. 659; see also: Abdel-Malek Neil, 2017). Once Ariana completed her studies, Lambeth council contracted her to pilot this way of working with a focus on preventing violence affecting young people and violence against women and girls, per their existing strategies. Because of persistently high levels of this violence, the local authority was open to more experimental approaches.

Ariana met Lucy whilst looking for a partner to co-design a methodology to explore vulnerability with children in transition. Lucy is a Dance Movement Psychotherapist and life-long movement professional who sees children and adolescents one-to-one and in groups in schools and community settings. At work, she often contemplates her young clients’ internal compass, something she sometimes struggled to keep hold of earlier in her life after losing both of her parents as a young adult. When her hold on that compass became tenuous, for example, when she went through a shift in her housing situation, she faced vulnerability, volatile emotions, inner conflict, and uncertainty. As a result of her fragmented sense of belonging and home, she struggled to stay in one place and spent extended periods in Latin America, Africa, and Southern Europe, experiences that helped shape her practice. She has seen similar dynamics with young people she works with, their anxiety manifesting as emotional outbursts and other types of dysregulation that blur their sense of safety in relation to their surroundings.

Lucy trained in dance movement therapy (DMT) to support children and young people in exploring the connection between their internal and external worlds whilst offering new experiences of being (Eddy, 2002). “[M]ovement allows us to approach [dialectical concepts] from another perspective: a shifting one,” explains Manning (2009, p. 15). DMT can also foster a non-medicalised sense of safety within one’s body (Ellis, 2001). Biomedicine in the Global North tends to pathologise and individualise emotional and psychological distress (Fassin & Rechtman, 2009), and stigma around mental ill health may close off non-medicalised outlets toward healing and making meaning. This includes creative practices for children and young people to express and explore how their inner worlds interact with their outer worlds, particularly for boys and young men (Dodzro & Goode, 2023). Children may struggle to recognise difficult feelings in their bodies as a result, which may hinder their ability to move through them. Instead, angst, discomfort, confusion, and other feelings may manifest externally through, for example, explosive or erratic behaviour.

Now, in retrospect, we both wonder whether our own challenges during periods of transition could have been less destabilising and quicker to resolve had we had earlier access to preventive support to build the knowledge and skills to identify and explore our feelings. The methodology we created together aimed to teach children to soften those moments of difficulty: to explore the feeling of vulnerability like any other piece of information. We wanted to show that “body listening” (Enghauser, 2007), and specifically that being curious about vulnerability, can help move through it, tracing a path toward finding ease whilst understanding our limits, and providing a source of hope, courage, connection, and authenticity.

4 Give It a Whirl: DMT as Method and Animation as Evidence

The methodology that we designed together was part of a youth forum series, an initiative that Ariana developed within the council to centre and celebrate young people’s expertise in preventing the violence that affects their lives. Each edition of the forum had a different theme and dynamic, but all of them were co-designed, co-facilitated, and documented by artists. Depending on the methods, each edition of the forum was open to more or fewer people. Whatever the size, however, working collectively was the point because the experience of violence affecting young people is shared by definition. Visceral methods, explains Shaw, “are essentially relational: they prompt group members to speak about their lives and listen to each other; together they make sense of their realities through reflective dialogue; and later, pathways to influence are an inherent possibility” (2020, p. 106). Moreover, visceral methods carve out space for enjoyment, rest, and creative expression and agency (Sweet, 2017).

Group therapy practices create unity and hope amongst people with shared experiences, which in turn can beget validation and acceptance (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). Working in a circle can amplify these outcomes by allowing participants to see and be seen as equals (Chaiklin, 1975). Circles in DMT echo circles for restorative practice, forging a psychotherapeutic container for raw and difficult emotions (Winnicott, 2005). DMT groups also provide space to mirror and be mirrored, to see each other through relational interactions rather than being confined by our individual psychic processes (Stern, 1985). Taking our cues from somatic practices, we grounded our methodology in circular movement and mirroring (McGarry & Russo, 2011).

The selection of themes for each youth forum stemmed from Ariana’s work with community and public sector partners, including in the aftermath of lethal and life-changing violence, and from emerging research. Ariana framed each theme through the senses to determine which art form(s) could facilitate its exploration and evidencing. Intergenerational tensions, for example, are often rooted in fear that derives from bewilderment – the age-old misunderstandings of “kids these days” hardening into suspicions of criminality that touch everyone in the commiunity (Billingham & Irwin-Rogers, 2022). Theatre offers a route toward mutual understanding, enabling participants to rehearse responses to real-life scenarios, question power dynamics, surface systemic barriers, and identify levers for change.

In contrast, working on vulnerability involves scaling the porous and ragged boundary between our inner and outer lives amidst hardship. Finding ease in the movement across that boundary lends itself to dance, which is the art of conveying felt experiences as movement (Tortora, 2006). DMT can aid in loosening and shifting our feelings and externalising what we are holding inside (Schmais, 1985); in a broader sense, movement can build the foundation for change (Resnik, 1995). Through physical exploration and expression, we can fuse cognitive, sensory, and affective experiences that weave together our past and present (Bloom, 2006).

Baker et al. observe that the knowledge emerging from what they refer to as “danced movement” “may require a certain amount of reflection…to be translated and unpacked through oral and written language. For scholars wishing to engage with danced movement as methodology we would suggest that this is where the role of supporting methods comes into play” (2022, p. 8). To evidence data in motion, we turned to animation, the art of creating and capturing movement. Ariana connected with Jennifer Zheng, a local resident and the associate creative director at BUCK, an animation studio. Jennifer began participating in our meetings to develop the workshop methodology. As the workshop took shape, she had creative freedom to evidence it how she saw fit.

5 Get Into a Groove: Delivering a Movement Workshop on Vulnerability

Prior to the workshop, we spent several months building a relationship with local school administrators. At the recommendation of Ariana’s local authority colleagues, she approached the administrators of three school clusters with strong mental health and arts programming for students. In particular, these clusters run an initiative to train Pupil Wellbeing Ambassadors: Year 5 and Year 6 students (aged 9–11 years) whom the schools support to develop tools for mindfulness, wellbeing, and good mental health that they use to uplift their school community. Ambassadors meet online every month and celebrate their work together in an annual conference each summer. The programme has been running in primary schools across the three clusters since 2021, and there are plans to roll it out to secondary schools. In addition, because of the range of artistic activities available to all students, cluster schools have high-quality, specialised performance and rehearsal facilities.

Ariana explained to the cluster administrators that she was co-designing a movement workshop on vulnerability with a dance movement psychotherapist for students in Years 6 and 7. This is the last year of primary school and the first year of secondary school (aged 10–12 years old), respectively, which is a key period in transitional safeguarding. The administrators agreed that the workshop aims aligned with their wellbeing and creative programming and were keen for us to pilot it in their school community. Upon confirming that both of us had valid disclosure and barring service (DBS) certificates, they offered to assemble a group of 30 children who were all current or former Pupil Wellbeing Ambassadors; for the pilot, we decided to work with children who the administrators felt would be able to remain regulated enough to stay in the room and engage in the activity. The administrators did not inform us of any participant’s personal history of or involvement with violence, but data about young people in the borough is sobering: 40% of Lambeth’s children live in poverty, 20% have special educational needs but only 70% of them receive support for those needs, and the borough has the highest number of young people injured by knives in London. Two-thirds of respondents to a May 2023 survey chose violence affecting young people as the borough’s most urgent priority for violence prevention (Demographics Factsheet, 2024; Safer Lambeth Partnership Strategy, 2023).

Ariana wrote up a short information sheet to share with the children’s parents and carers to seek their consent for their children’s participation. Baker notes that “danced movement’s privileging of embodied and more-than-cognitive knowledges can give rise to vulnerability” (2025, p. 5), so we also discussed and committed to following the cluster safeguarding protocols in the event that a child made a disclosure. Teachers from each school accompanied their students to the workshop and remained present throughout, shifting between participating themselves and observing and offering assistance as needed.

We held the workshop in February 2024 during the school day in the dance studio at one of the secondary schools to foster a sense of safety and familiarity. We arrived early so that the school could check our DBS certificates. Since Jennifer did not have one, which we knew, we were required to accompany her at all times whilst in the school. Together, we assessed the safety and suitability of the studio and set up what we needed: open space to move, a sound system, and a place for Jennifer to observe. We also drew the curtains over the studio mirrors. The forum began with an opening circle (Figure 1), allowing participants to see each other and gain an understanding of the purpose of our time together: to feel and move through vulnerability. We made a verbal contract to prioritise each other’s safety, and we confirmed that the children understood that they had permission to withdraw at any time for any reason. Since the children came from several different schools, many of them had never met each other. Their posture was closed, they were timid and apprehensive, and they stayed near the few people they knew. When we asked how they were, they mostly gave one-word answers. One child hugged her knees and bowed her head, whilst another one repeatedly re-tied and then smoothed her ponytail. Jennifer sat to one side and sketched.

The workshop participants sit in an opening circle. Ink sketch on paper by Jennifer Zheng.

We knew from the cluster administrators that vulnerability had not yet come up in the curriculum, so we asked the participants if they knew what it was and if it was something they had experienced before. Some Year 6 students said they felt vulnerable when they thought about beginning secondary school or interacting with bigger or older children. Some participants shared their fears of insects, animals, or the dark, or talked about specific situations where they felt out of their depth or betrayed by someone they trusted, like being thrown into deep water by a parent when they could not swim. They recounted getting sweaty palms or feeling like they had a “fuzzy head.” A few children mentioned anxiety about walking to and from the bus to get to school because of the risk of “bad kids” in the neighbourhood, an assessment they sometimes shared with their families and sometimes disputed. For some, these diverging views were a source of tension at home. Ariana stayed outside the circle with macramé cords affixed to a metal ring (Figure 2). Each time a child shared their experience, she made a knot in the piece as a visual and tangible way to anchor and ground participants in the space and signal that everyone’s presence and stories mattered (Billingham & Irwin-Rogers, 2021). The piece symbolised the possibility that binding together our vulnerabilities might create something beautiful and solid. Lucy asked the participants to think about what vulnerability felt like in their bodies: Was it like a kangaroo kicking in your chest? A butterfly flapping its wings in your stomach? Both of us emphasised that feeling and expressing vulnerability could be powerful if we could use it to navigate toward comfort and ease.

A macramé plant hanger that Ariana made. Macramé is a type of textile art that uses knots to create designs. Photo by Ariana Markowitz, 2022.

Lucy led a group warm-up that included simple, repetitive movements to build community cohesion, allow the children to become familiar with the space, and aid in regulation and physical awareness. The children laughed as we moved together, and their movements became looser and larger. As they took up more space, their posture opened up (Figure 3). Lucy had curated a playlist featuring local artists to connect the children with the creative and cultural heritage of their community. Throughout the workshop, she frequently changed the music so the children could explore their movements at a different speed or to the beat of another rhythm.

The workshop participants transition from the opening circle to warming up. Ink sketch on paper by Jennifer Zheng.

After the warm-up, participants divided themselves into pairs with someone they did not know. We asked them to remember where in their bodies they felt vulnerability and to move in a way that represented that feeling (Figure 4). As the children began creating their own movements, some of them seemed confused about what they “should” be doing or concerned that they might get it “wrong.” We asked their partners to mirror them, enabling vulnerability to be simultaneously felt, expressed, and seen. Finally, we asked their partners to do the opposite movement – if one person went big, their partner went small, if one person crouched down, the other reached high – demonstrating a way to physically move through vulnerability. Then the partners switched roles, giving the second person a chance to lead. The exercise guided the children in moving into and out of vulnerability whilst accompanying, witnessing, and validating each other. In addition, though we introduced Jennifer at the start of the workshop, the participants initially paid her little mind. By this point in the workshop, however, the children noticed that she was surrounded by growing stacks of paper. They increasingly approached her to ask what she was doing and to look for themselves and their friends and partners in her sketches.

The workshop participants begin moving together. Ink sketch on paper by Jennifer Zheng.

Collaboration ignited the children’s confidence, leading to more authentic, exploratory movements. The mirroring was also a form of play, demystifying a feeling that was initially arduous, alarming, or overwhelming and transforming it into a source of curiosity, even silliness. A small child in a huge blazer began doing the Russian dance barynya, repeatedly dropping into a deep squat and then popping back up again with his heels pressed down and feet turned out. His partner struggled to mirror him, but had better luck doing the opposite: statically reaching toward the sky on his toes, his legs zipped together and edging inward. Two children found that they had learnt the same dance on TikTok and silently locked into that choreography as the basis for their exploration of vulnerability. Another pair zoomed across the room backwards and forwards, maintaining their frenzied tempo even when the music slowed. One child lay on the floor, moving as if she were making a snow angel with her hair arrayed around her head. Her partner alternately sat next to her or lay down in the opposite direction.

We all reassembled in a circle and asked pairs to volunteer to demonstrate a sequence of their favourite movements. All of us mirrored those sequences together, the energy whipping around the circle. We finished with a verbal check-out where we asked participants to share something they appreciated about the session or one word that captured how they were feeling. In contrast to the opening circle, we heard more detailed, expressive descriptions of the experience. Many children said they felt “relaxed” or “energised.” Another said he loved working with his partner and another, nearly bursting at the seams, offered that he was “just so happy to meet so many new children today!” With each comment, Ariana made another macramé knot. We, and the children’s teachers, were thrilled that something that could have been scary or heavy ended in such a positive way.

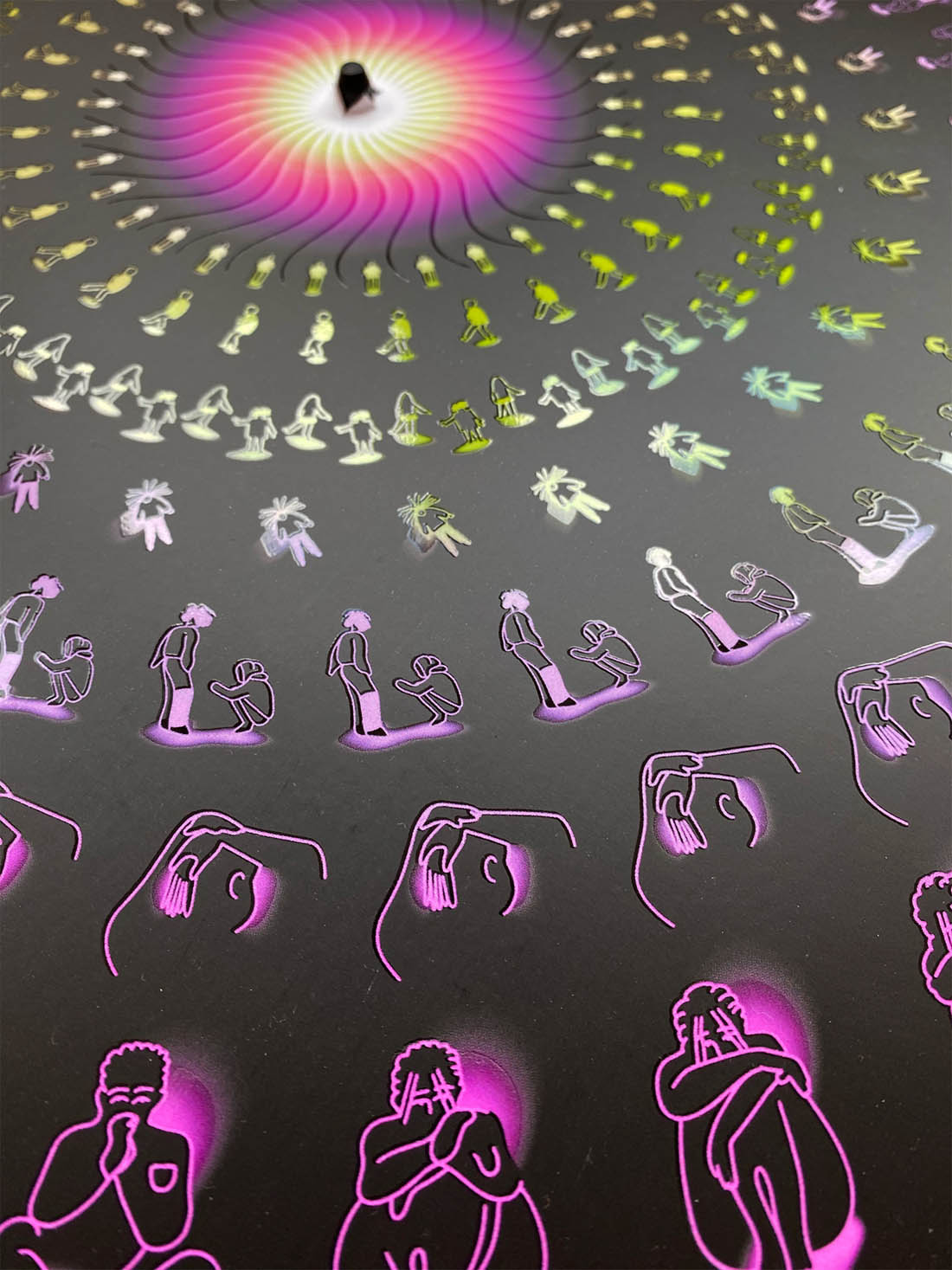

A few months later, Jennifer delivered a phenakistoscope – an animated digital print that spun on an armless record player – to Lambeth Town Hall (Figures 5 and 6). Phenakistoscopes were one of the earliest forms of animation, a novelty Victorian-era children’s toy that has since fallen out of use apart from rare picture discs. Today, viewed through a camera calibrated to the speed of the record player’s rotations, it gives the illusion of fluid motion. Jennifer created a physical rather than a digital object that the participants, and others, could touch and play with, and that they would have to manipulate with curiosity and patience for the animation to reveal itself. Rooting the animation in play also emphasised the playful dynamic of the workshop and the youth of the participants. When the print spins on the record player, the children’s movements circulate, just as they did in the forum. On the border of the print, Jennifer wrote words that the children said, which structure and contain their movements: “We have to move smooth! My hands get sweaty, I feel vulnerable when it’s dark, someone bigger than you, spiders, I get a fuzzy head. Are you Russian? No! I just like it! I get scared of secondary school, spiders!!! I feel energetic! I’m really glad I came today.” She called the piece Ring a Ring o’ Poses.

Ring a Ring o’ Poses. Animated digital print on an armless record player by Jennifer Zheng.

Close-up of Ring a Ring o’ Poses. Animated digital print on an armless record player by Jennifer Zheng.

6 Conclusion: Moving Along

Drawing from our lived and professional experience, we consider learning how to identify and find ease in vulnerability to be fundamental for upstream violence prevention. Existing scholarship indicates that talk-based methods alone – whether in social science or therapeutic settings – may be insufficient for probing experiences that are hard to name or that tend to go unrecognised by the criminal justice system. This encompasses forms of structural and chronic violence that we have witnessed and supported young Londoners to navigate, amongst them stigma, suspicion, exclusion, adultification, and gentrification.

In these situations, visceral artistic and kinetic methods, which involve “experiential inquiry inclusive of physical awareness, cognitive reflection, and insights from feelings” (Eddy, 2002, p. 119), may be more effective for data collection and transformative for the young people involved. Indeed, in feedback after the workshop, the cluster administrators affirmed that dance and movement were potent tools for guiding children to feel and move through vulnerability. As the participants themselves reported, they came out of the workshop at ease, energised, and connected with each other. These feelings are a foil to the anxiety, fear, and isolation that many children experience in the transition from primary to secondary school, which are magnified in neighbourhoods affected by violence. Evidencing non-traditional research methods can benefit from seeking out alternative ways to capture information. In our case, collaborating with an animator enabled us to document movement. Moreover, unlike a written report, Ring a Ring o’ Poses is accessible to any audience, including the young participants themselves, and it maintains their anonymity.

Our work fed into Lambeth’s 2020 commitment to become “one of the safest places for children, teenagers, and young adults in London by 2030” through early support, disruption and deterrence, education and training, assistance for people affected by violence, community engagement, and high-quality public spaces (Lambeth Made Safer, 2020, p. 11). Despite the early promise of our methodology, including recognition as a city-wide model practice by the Greater London Authority, a few months after we delivered the workshop, Lambeth opted not to extend Ariana’s contract. Like many local authorities across the country, the borough is labouring under significant debt and has redefined its priorities, restructured, and reworked its approach to community engagement. None of that detracts from our transdisciplinary collaboration, however, which was enriching and joyful. Working together allowed us to complement each other’s knowledge, question the tenets of our disciplines, and turn us from colleagues into friends.

We are now pursuing other opportunities to refine our work, tapping into our links to other areas of the city. One element that interests us is piloting a modification for adults and using Ring a Ring o’ Poses as a means of sharing insight into what vulnerability looks like in the bodies of children. An animator we met with suggested creating rectangular digital animation panels to interrogate how adults hold their emotions. Are the containers we build for that purpose more regimented than the children’s spiralling energy? If so, do sharper angles help or hinder our capacity to access our vulnerability? Adults can play a steadying role in preventing violence affecting young people, but to maintain that steadiness – to be present with children during their moments of hardship and pain – demands that we are conscious of what vulnerability feels like in our bodies. All of us, of any age, can work toward recognising that stepping out of line is stepping into resistance, power, and compassion.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the London local authority officers, educators, and children who supported our experimentation and collaboration. Thanks also to the two anonymous reviewers whose comments sharpened our writing and ensured that people and context remained front and centre.

-

Funding information: Lambeth council and the schools with which we partnered provided financial and other types of support. Ariana developed the youth forum as part of her full-time paid work as a council employee.

-

Author contributions: Both authors accept responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consent to its submission to the journal after reviewing all the results and approving the final version for publication. AM developed the Lambeth Youth Forum, of which the Stepping Out of Line methodology was a part. AM and LEW co-designed the Stepping Out of Line methodology and co-facilitated the workshop where it was piloted. The authors prepared this manuscript together.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Abdel-Malek Neil, M. (2017). Affective migration: Using a visceral approach to access emotion and affect of Egyptian migrant women settling in the Region of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. Emotion, Space and Society, 25, 37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2017.10.005.Suche in Google Scholar

About Us. (2022). Scottish violence reduction unit. https://www.svru.co.uk/about-us/.Suche in Google Scholar

Allen, A. (2022). Navigating stigma through everyday city-making: Gendered trajectories, politics and outcomes in the periphery of Lima. Urban Studies, 59(3), 490–508. doi: 10.1177/00420980211044409.Suche in Google Scholar

Arrieta, T. (2022). Austerity in the United Kingdom and its legacy: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 33(2), 238–255. doi: 10.1177/10353046221083051.Suche in Google Scholar

Baker, G. (2025). Questions of power and ethics: Doing feminist research in methodological contexts that let the body lead. Area, 1–9. doi: 10.1111/area.70030.Suche in Google Scholar

Baker, G., Kindon, S., & Beausoleil, E. (2022). Danced movement in human geographic research: A methodological discussion. Geography Compass, 16(8), 1–16. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12653.Suche in Google Scholar

Baumann, H., & Yacobi, H. (2022). Introduction: Infrastructural stigma and urban vulnerability. Urban Studies, 59(3), 475–489. doi: 10.1177/00420980211055655.Suche in Google Scholar

Bergmann, A. (2020). Glass half full? The peril and potential of highly organized violence. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 73, 31–43. doi: 10.7440/res73.2020.03.Suche in Google Scholar

Billingham, L., & Irwin-Rogers, K. (2021). The terrifying abyss of insignificance: Marginalisation, mattering and violence between young people. Oñati Socio-Legal Series, 11(5), 1222–1249. doi: 10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1178.Suche in Google Scholar

Billingham, L., & Irwin-Rogers, K. (2022). Against youth violence: A social harm perspective. Bristol University Press. https://bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/against-youth-violence.10.1332/policypress/9781529214055.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Blakemore, S. J., & Mills, K. L. (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202.Suche in Google Scholar

Bloom, K. (2006). The embodied self, movement and psychoanalysis. Karnac.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (2005). An invitation to reflexive sociology (2nd ed.). Polity Press. (Original work published 1992).Suche in Google Scholar

Bourgois, P. (2001). The power of violence in war and peace: Post-Cold War lessons from El Salvador. Ethnography, 2(1), 5–34. doi: 10.1177/14661380122230803.Suche in Google Scholar

Bray, K., Braakmann, N., & Wildman, J. (2024). Austerity, welfare cuts and hate crime: Evidence from the UK’s age of austerity. Journal of Urban Economics, 141, 103439. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2022.103439.Suche in Google Scholar

Brown, G., El-Erian, M. A., Spence, M., & Lidow, R. (2023). Permacrisis: A plan to fix a fractured world. Simon and Schuster. https://www.simonandschuster.co.uk/books/Permacrisis/Reid-Lidow/9781398525641.Suche in Google Scholar

Chaiklin, S. (1975). Dance therapy. In A. Silvano (Ed.), American handbook of psychiatry (2nd ed., Vol. 5, pp. 701–720). Basic Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Cocker, C., & Cooper, A. (2022). Transitional safeguarding: Opportunities to improve safeguarding practices with young people. Practice, 34(1), 1–6. doi: 10.1080/09503153.2021.1979505.Suche in Google Scholar

Das, V. (2006). Life and words: Violence and the descent into the ordinary. University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/books/life-and-words/paper.10.1525/9780520939530Suche in Google Scholar

Das, V., & Fassin, D. (Eds.). (2021). Words and worlds: A lexicon for dark times. Duke University Press. doi: 10.1215/9781478021476.Suche in Google Scholar

Davies, T. (2019). Slow violence and toxic geographies: ‘Out of sight’ to whom? Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 40(2), 409–427. doi: 10.1177/2399654419841063.Suche in Google Scholar

Demographics Factsheet. (2024). Children and young people aged under 20: Demographics factsheet, 2024 (p. 30). London Borough of Lambeth. https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2025-01/lambeth-children-and-young-peoples-demography.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Dodzro, R., & Goode, W. (2023). The life of a top boy: On trauma and violence in the community (p. 53). Juvenis. https://www.juvenis.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/The-Life-Of-A-Top-Boy.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Eddy, M. H. (2002). Dance and somatic inquiry in studios and community dance programs. Journal of Dance Education, 2(4), 119–127. doi: 10.1080/15290824.2002.10387220.Suche in Google Scholar

Ellis, R. (2001). Movement metaphor as mediator: A model for the dance movement therapy process. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 28(3), 181–190. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4556(01)00098-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Enghauser, R. (2007). Developing listening bodies in the dance technique class. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 78(6), 33–37, 54. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2007.10598039.Suche in Google Scholar

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W.W Norton & Company.Suche in Google Scholar

Farmer, P. E. (2000). The consumption of the poor: Tuberculosis in the 21st century. Ethnography, 1(2), 183–216. JSTOR.10.1177/14661380022230732Suche in Google Scholar

Fassin, D., & Rechtman, R. (2009). The empire of trauma: An inquiry into the condition of victimhood (R. Gomme, Trans.). Princeton University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167–191. doi: 10.1177/002234336900600301.Suche in Google Scholar

Galtung, J. (1990). Cultural violence. Journal of Peace Research, 27(3), 291–305. doi: 10.1177/0022343390027003005.Suche in Google Scholar

Hassan, G. (2020). Violence is preventable, not inevitable: The story and impact of the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit (p. 21). Scottish Violence Reduction Unit. https://www.svru.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/VRU_Report_Digital_Extra_Lightweight.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Hayes-Conroy, A. (2017). Critical visceral methods and methodologies. Geoforum, 82, 51–52. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.03.017.Suche in Google Scholar

Hayes-Conroy, A., & Hayes-Conroy, J. (2015). Political ecology of the body: A visceral approach. In R. L. Bryant (Ed.), The international handbook of political ecology (pp. 659–672). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9780857936165/9780857936165.00058.xml.10.4337/9780857936172.00058Suche in Google Scholar

Holmes, D., & Smale, E. (2018). Transitional safeguarding: Adolescence to adulthood (p. 28). Research in Practice. https://www.rip.org.uk/resources/publications/strategic-briefings/transitional-safeguarding--adolescence-to-adulthood-strategic-briefing-2018/.Suche in Google Scholar

Hume, M., & Wilding, P. (2020). Beyond agency and passivity: Situating a gendered articulation of urban violence in Brazil and El Salvador. Urban Studies, 57(2), 249–266. doi: 10.1177/0042098019829391.Suche in Google Scholar

Indar, G. K., Barrow, C. S., & Whitaker, W. E. (2023). A convergence of violence: Structural violence experiences of K–12, Black, disabled males across multiple systems. Laws, 12(5), 80. doi: 10.3390/laws12050080.Suche in Google Scholar

Keuleers, F., & Mulenga Hornsby, N. (2022). Women in El Salvador’s gang war: Surviving the State of Exception. International Crisis Group. https://facesofconflict.crisisgroup.org/women-in-el-salvadors-gang-war/.Suche in Google Scholar

Lambeth Made Safer. (2020). Lambeth Made Safer for Young People Strategy, 2020–2030 (p. 40). London Borough of Lambeth. https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2023-08/Appendix%20A%20-%20Lambeth%20Made%20Safer%20Strategy%20v19%20%281%29.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Lambeth Made Safer Violence against Women and Girls Strategy. (2021). Lambeth Made Safer Violence against Women and Girls Strategy, 2021-2027 (p. 29). London Borough of Lambeth. https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2021-10/lambeth-made-safer-vawg-strategy-2021-2027.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Lawrence, M., Homer-Dixon, T., Janzwood, S., Rockstöm, J., Renn, O., & Donges, J. F. (2024). Global polycrisis: The causal mechanisms of crisis entanglement. Global Sustainability, 7, e6. doi: 10.1017/sus.2024.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Locke, R., Shantz, K. P., Serbin-Pont, A., & Sutherland, J.-A. (Eds.). (n.d.). Identity-based mass violence in urban contexts: Uncovered. Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved 25 July 2025, https://link.springer.com/book/9783031980671.Suche in Google Scholar

Lyon, P. (2020). Using drawing in visual research: Materializing the invisible. In L. Pauwels & D. Mannay (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of visual research methods (2nd ed., pp. 297–308). SAGE Publications.10.4135/9781526417015.n18Suche in Google Scholar

Manning, E. (2009). Relationscapes: Movement, art, philosophy. MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262134903.001.0001.Suche in Google Scholar

Markowitz, A. (2019). The better to break and bleed with: Research, violence, and trauma. Geopolitcs, 26(1), 94–117. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2019.1612880.Suche in Google Scholar

Markowitz, A. (2022). Making dangerous places: Toward a feminist methodology amid extreme and chronic urban violence [Doctoral thesis, University College London]. UCL Discovery. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10157544.Suche in Google Scholar

Markowitz, A. (2025). It can get better: Making meaning from trauma. Sexual Violence Research Initiative. https://www.svri.org/it-can-get-better-making-meaning-from-trauma.Suche in Google Scholar

Markowitz, A. & Olmos Herrera, C. (n.d.). “You look good in short skirts”: Gender-based violence in fieldwork. In J. Rendell, D. Roberts, & Y. Padan (Eds.), Practising ethics: A poethic infrastructure for architectural and urban researchers. UCL Press.Suche in Google Scholar

McGarry, L. M., & Russo, F. A. (2011). Mirroring in dance/movement therapy: Potential mechanisms behind empathy enhancement. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38(3), 178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2011.04.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, Trans.). Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Nind, M., Flewitt, R., & Payler, J. (2011). Social constructions of young children in ‘special’, ‘inclusive’ and home environments. Children & Society, 25(5), 359–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00281.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.10.4159/harvard.9780674061194Suche in Google Scholar

Ofer, N., Hitchen, R., Roy, S., Rowson, M., & Couchman, H. (2025). Unfair use of ‘bad character’ evidence against rape victims: How unrelated previous disclosures of rape are used to discredit survivors (p. 9) [Joint Briefing for House of Lords]. Centre for Women’s Justice; End Violence Against Women; Imkaan; Rape Crisis England and Wales; Rights of Women. https://rapecrisis.org.uk/news/government-announce-a-new-victims-and-courts-bill/.Suche in Google Scholar

Ojo, R., Senghor, S., Robb, B. L., Oliver-Holland, C., Bakalis, C., Jago, E., Mota, H., Heald, J., Appiah, J., Floyd, J., & Sergiou, T. (2019). Our generation’s epidemic: Knife crime (p. 66). British Youth Council Select Committee. https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/youth-select-committee---our-generations-epedemic-knife-crime.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Pain, R. (2018). Chronic urban trauma: The slow violence of housing dispossession. Urban Studies, 56(2), 385–400. doi: 10.1177/0042098018795796.Suche in Google Scholar

Pearce, J. (2007). Violence, power and participation: Building citizenship in contexts of chronic violence (Working Paper 274; p. 66). Institute for Development Studies. https://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk/handle/10454/3802.Suche in Google Scholar

Rabe, J. (2023). ‘We chose what was important to us’: Navigating the ‘messiness’ of participatory research with young people [University of Bedfordshire]. Our Voices. https://www.our-voices.org.uk/news/2023/we-chose-what-was-important-to-us-navigating-the-messiness-of-participatory-research-with-young-people.Suche in Google Scholar

Resnik, S. (1995). Mental space. Karnac.Suche in Google Scholar

Rex, B. (2020). Which museums to fund? Examining local government decision-making in austerity. Local Government Studies, 46(2), 186–205.10.1080/03003930.2019.1619554Suche in Google Scholar

Safer Lambeth Partnership Strategy. (2023). Safer Lambeth Partnership Strategy, 2023–2030 (p. 56). London Borough of Lambeth. https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2024-01/102573%20Safer%20Lambeth%20Partnership%20FINAL%20ACC.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

San Roman Pineda, I., Lowe, H., Brown, L. J., & Mannell, J. (2023). Viewpoint: Acknowledging trauma in academic research. Gender, Place & Culture, 30(8), 1184–1192. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2022.2159335.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmais, C. (1985). Healing processes in group dance therapy. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 8(1), 17–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02251430.Suche in Google Scholar

Serious Violence Strategy. (2018). Serious violence strategy (p. 111). Home Office. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/serious-violence-strategy.Suche in Google Scholar

Sexton, A. E., Hayes-Conroy, A., Sweet, E. L., Miele, M., & Ash, J. (2017). Better than text? Critical reflections on the practices of visceral methodologies in human geography. Geoforum, 82, 200–201. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.03.014.Suche in Google Scholar

Shaw, J. (2020). Navigating the necessary risks and emergent ethics of using visual methods with marginalised people. In S. Dodd (Ed.), Ethics and integrity in visual research methods (Vol. 5, pp. 105–130). Emerald Publishing Limited. doi: 10.1108/S2398-601820200000005011.Suche in Google Scholar

Spiteri, J. (2024). Children’s voices and agency: Ways of listening in early childhood quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research. Elements in Research Methods for Developmental Science. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781009285407.Suche in Google Scholar

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–314). University of Illinois Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Stel, N. (2016). The agnotology of eviction in South Lebanon’s Palestinian gatherings: How institutional ambiguity and deliberate ignorance shape sensitive spaces. Antipode, 48(5), 1400–1419. doi: 10.1111/anti.12252.Suche in Google Scholar

Stern, D. N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. A view from psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. Basic Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Stevens, A., Schreeche-Powell, E., Billingham, L., & Irwin-Rogers, K. (2025). Interventionitis in the criminal justice system: Three English cases. Critical Criminology, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10612-024-09808-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Sweet, E. L. (2017). The benefits and challenges of collective and creative storytelling through visceral methods within the neoliberal university. Geoforum, 82, 202–203. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.03.018.Suche in Google Scholar

Sweet, E. L., & Ortiz Escalante, S. (2015). Bringing bodies into planning: Visceral methods, fear and gender violence. Urban Studies, 52(10), 1826–1845. doi: 10.1177/0042098014541157.Suche in Google Scholar

Tortora, S. (2006). The dancing dialogue: Using the communicative power of movement with young children. Brookes Publishing Co.Suche in Google Scholar

Winnicott, D. (2005). Playing and reality (2nd ed.). Routledge Classics.Suche in Google Scholar

Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. (2005). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (5th ed.). Basic Book.Suche in Google Scholar

Zulver, J., & Méndez, M. J. (2023). El Salvador’s ‘State of Exception’ makes women collateral damage. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2023/05/el-salvadors-state-of-exception-makes-women-collateral-damage?lang=en.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction