Abstract

This study advances the application of Pierre Bourdieu’s social field as a heuristic conceptual tool in the context of translation studies, offering a methodological framework that integrates socio-historical analysis with bibliographical research. By exploring the field of Arabic translations of English self-help literature in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) between 1982 and 2016, the article illustrates how Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of social fields can be operationalised to define the boundaries, agents, production, and practices within a translation field. A bespoke bibliographical database comprising 993 translated self-help titles was constructed to provide a detailed mapping of the field’s historical trajectory and production dynamics. Through this integration of theory and empirical data, the study demonstrates how field theory can enrich the analysis of translation as a social practice, revealing the interactions between translation agents and the socio-historical forces that shape the production of translations. The findings suggest that this integrated approach can serve as a heuristic model for the socio-historical analysis of translation fields across different language pairs, temporal periods, and geographic contexts, contributing to future research in translation sociology and translation bibliographies.

1 Introduction

Investigating translations within their respective fields or domains of cultural production has attracted the attention of many translation researchers (cf. Alkhamis, 2013, 2019; Alsiary, 2016; Hanna, 2016; Heilbron & Sapiro, 2007; Khalifa, 2017; Sapiro, 2008, 2010; Sapiro & Bustamante, 2009). Their views are impacted by the social turn in translation studies, aiming to examine the broader social space within which translations occur and to address what Gouanvic (1997, p. 126) called the “absence of the social” in translation studies. Gouanvic used this phrase to describe the perceived lack of social context, understanding, or consideration in Gideon Toury’s work, Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond (1995). Gouanvic emphasises the importance of incorporating a social perspective by proposing a shift towards a sociology of translation, specifically drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of social practice.

This article provides a practical application of Bourdieu’s theory, integrating the concept of field as a theoretical framework with bibliographical research as a methodological framework. This combination serves to define the field of Arabic translations of English self-help books in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) from 1982 to 2016. It is important to note that this article does not aim to analyse the field under study fully but rather to delineate its boundaries, showcasing how a translation field’s boundaries can be set using Bourdieu’s field theory and bibliographical research. The study is guided by the key research question:

How can Bourdieu’s field theory be integrated with bibliographical research to enhance data verification and socio-historical analysis in the study of the field of Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA?

The article begins by outlining the theoretical foundations of Bourdieu’s concept of field and its relevance to translation studies, as well as how it has been adopted to study relevant translation fields and production. This is followed by a discussion of the bibliographical research on translations in KSA. The discussion addresses the realities of the available translation bibliographies in KSA and how they are used for socio-historical analysis. It also discusses recent developments in translation bibliographies in KSA that can enhance both the quality of the extracted bibliographical data and, in turn, the quality of the socio-historical analysis in this study. The discussion then moves to how this study reciprocally uses the concept of field to define the bibliographical data, which in turn helps to define the field’s boundaries. The opening section begins by illustrating how the concept of field is used to define the field theoretically, with the aim of transforming this theoretical definition into practical boundaries for the bibliographical data to be collected. The focus then shifts to a discussion of the initial findings on the field, drawing socio-historical maps and illustrations of the translation field, its agents, and production, and the socio-historical events that impact its emergence and development throughout its history. This study benefits from different levels of mapping that Bourdieu’s field provides, clarifying how the field under study can be discussed and analysed socio-historically. Finally, the article concludes with closing remarks revisiting the research question and offering recommendations for future research.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Bourdieu’s Field and Fields of Translation

As part of the sociological turn in translation studies, Bourdieu’s theory of social practice has been introduced to investigate translations as social practices that impact and are impacted by their social contexts. Central to Bourdieu’s theory is the concept of field, which was developed to explain social reality and social practices, and which has been applied in various ways in translation studies. He argues that people’s interactions and social practices cannot be justified or explained solely by looking at what has been said or what has happened; rather, it is crucial to account for the whole social space within which these interactions and practices have taken place (Bourdieu, 2005, p. 148). The field can be defined as a network of relationships between different positions or roles occupied by individual or institutional agents. These agents are characterised by how much power or resources (capital) they hold – which affects their ability to gain specific benefits within the system – and by their relative relationships to each other – i.e., whether one is above another or similar to another (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 97). Thomson (2012, pp. 66–67) simplifies Bourdieu’s field by comparing it to a football field, highlighting its clear boundaries and defined roles for participants. Just as football players must understand the rules and their positions, individuals within Bourdieu’s field need to comprehend its dynamics and their roles within it. Additionally, similar to how the state of the football field affects gameplay, the conditions within Bourdieu’s field influence the actions and opportunities available to its participants.

Thus, the social field consists of social positions occupied by individual or institutional social agents. The practices of the field’s agents are governed by participation rules, termed the “rules of the game” or “doxa” (Bourdieu, 1998a, p. 32). The agents in each field competitively apply various strategies or “position-takings” (Bourdieu, 1983, p. 312) to safeguard their positions and to achieve particular “stakes” or “capital” in the field (Bourdieu, 1990a, pp. 87–88). Bourdieu (1998b, p. 32), uses the notion of “struggle” or “competition” to describe these dynamic interactions in the field. Agents interact and compete to achieve various valuable forms of capital based on these socially organised objective relations, which, over time, create a definable but conditional history of development that represents the “dynamics of the field” (Jenkins, 1992, p. 70). Additionally, each social field interconnects and interacts with others within a particular social space – a phenomenon that Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992, p. 105) refer to as a “homology.”

According to Bourdieu (1996, p. 110), a field’s dynamics result from “the positions and the position-takings of the agents.” These positions are determined by the agents’ dispositions, known as “habitus,” which encompass their accumulated experiences, social backgrounds, and internalised ways of perceiving and acting in the world (Bourdieu, 1990b, pp. 53–60). The strategies employed by individual or institutional agents in this competitive environment are guided by their accumulated capital, social experiences, and habitus (Bourdieu, 1996, p. 99). Bourdieu argues that the concept of a “field of positions and position-takings” allows for a more comprehensive research approach that goes beyond individual analysis (1996, p. 34). It avoids limiting the research to internal considerations, such as focusing solely on a specific context, or to external considerations, such as solely examining the social conditions of production or the roles of producers and consumers in the field.

Bourdieu applies this concept to many fields, including education, art and culture, literature, social class, and power structures. However, his analysis of the French publishing field that encompasses translations seems the most relevant to the fields of translation both theoretically and methodologically, particularly when collecting bibliographical data on translations. Bourdieu (2008) collected bibliographical data from 38 publishers with the aim of mapping his field of study. He provides a comprehensive analysis of the French publishing industry, particularly focusing on the dynamics and transformations within the field of literary publishing in France. Sapiro (2008, pp. 163–164) argues that Bourdieu’s approach to studying the French publishing field is pertinent to translation studies. It can be employed to understand any translation field by grasping the broadest structures and forces that shape this field (macro level), understanding intermediate structures and forces such as publishing houses and cultural institutions which influence this respective translation field (mezzo level), and comprehending the individual agents and their interactions that shape production such as translators, editors, and readers (micro level).

Many translation researchers have combined Bourdieu’s field theory with bibliographical research to contextualise their field of translation, offering a theoretical and methodological framework for situating translations or translation fields within their respective social contexts (Alkhamis, 2013; Alsiary, 2016; Khalifa, 2017). Abdullah Alkhamis (2013) employs Bourdieusian theory to analyse the field of translation in KSA during the second half of the 20th century, for example. Alkhamis primarily relies on an existing bibliography – namely “The King Fahad National Library (KFNL) Bibliography of Translated Books in Arabic in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia” (2008) – which documents 2,218 books translated into Arabic in KSA from 1966 to 2007. Alsiary (2016) explores the impact of socio-cultural norms on children’s literature translation activities in KSA. Alsiary maps the field of children’s literature translation by creating a bibliography of 664 translations published in KSA between 1997 and 2016.

Alkhamis (2013) and Alsiary (2016) appear to overlook a crucial aspect in delineating their respective fields’ boundaries: the reliance merely on available bibliographical data, which does not suffice to comprehensively depict the history, agents, production, and practices of a translation field. Mapping a translation field through Bourdieu’s conceptual framework aims to include, as comprehensively as possible, the agents, practices, and productions within that field, while also striving to define the field’s boundaries with maximum precision. However, it is essential to recognise that a complete mapping of any translation field is likely unattainable. Instead, this approach calls for the utmost attention to detail in every step of the field’s definition, including the compiled data and the field’s parameters, such as the genre, the location, and the period, which all assist in achieving a more precise socio-historical analysis. The clear definition of these parameters is vital for facilitating more nuanced and accurate bibliographical research on translations and, thus, socio-historical analysis.

A notable scholarly contribution that effectively integrates Bourdieu’s field with bibliographical research to contextualise a translation field is presented by Khalifa (2017). Khalifa explores the socio-cultural determinants of the field of translation of modern Arabic fiction into English, drawing on Bourdieu’s theory. He examines the activity of translating English as a socially constructed practice, alongside the related individuals and institutions as socially regulated agents. To this end, he analyses a bibliography of English translations published between 1908 and 2014, combining statistical and socio-historical analyses with historical and archival materials. Khalifa’s study is notably advanced in terms of defining its field boundaries, which facilitates the delineation of its bibliographical data. The study’s key terminology – “modern,” “Arabic,” “fiction,” and “in English translation” – was carefully framed to define the study’s postulated translation field (2017, pp. 3–5).

Such framing and definition enable Khalifa (2017) to map the field, practices, production, and agents more precisely within their social context through a bibliography that was compiled for that specific study. The particular genre or literature, the languages of both the source and target texts, the spatial location and the temporal period of the particular genre or literature under study, and the translation medium are essential considerations for the definition of specific translation fields. Each of these considerations can present significant theoretical and practical challenges for the definition of a translation field. This is because establishing clear boundaries and employing a rigorous methodology are intended to create a standardised tool used to determine which translations should be included or excluded from the bibliographical data, thereby enhancing their accuracy and reliability for socio-historical investigation. Such an approach ensures a robust and systematic field analysis, contributing to a more accurate understanding of the socio-historical dynamics and practices involved in the respective translation field. Building on the above developments, this article proposes a practical framework that can aid in defining any translation field of cultural production and its bibliographical data, exemplified through the postulated field of Arabic translations of English Self-help books in KSA.

2.2 Bibliographical and Socio-Historical Research on Translations in Saudi Arabia

One challenge faced by many translation studies within the broader Arab context, including KSA, that employ Bourdieu’s framework and utilise bibliographical databases is the difficulty in delineating the boundaries of the fields, and particularly in identifying the agents and production, due to incomplete bibliographical databases (see, e.g., Alkhamis, 2019, 2013; Alsiary, 2016; Hanna, 2011, 2016; Khalifa, 2017). The absence of thorough empirical bibliographical investigations in studies related to the Arabic context hampers a comprehensive grasp of their socio-historical and Bourdieusian dimensions. This issue has been acknowledged by the authors of these studies themselves, as indicated by Alkhamis (2013, p. 22) and Alsiary (2016, p. 19). Hence, it is crucial to shed some light on the history and present state of bibliographical databases in KSA. This exploration aims to elucidate both their merits and constraints for the bibliographical research in this socio-historical investigation.

In the context of KSA, many studies have attempted to compile and analyse translations prior to the emergence of the first official bibliography of translations, namely the KFNL bibliography of the 2,218 translated books in Arabic published in KSA from 1966 to 2007, which itself was published in 2008. These studies include: (1) Halbawi (1987), which presents and discusses a bibliography of Arabic translations published in KSA between 1970 and 1985; (2) Alnasser (1998), which presents and discusses a bibliography of 502 translations published in KSA between 1932 and 1992; (3) Alkhatib (2007), which offers a discussion on the economic performance of the Arabic translation industry in KSA by studying a bibliographical database of 1,206 translations into Arabic published between 1955 and 2004. However, the authors recognise the challenge of achieving completeness in their bibliographies of translations. Moreover, the analysis in these studies is primarily statistical, rather than investigating the socio-historical aspects of these translations. A core issue in these studies is the excessive emphasis on the shortage of bibliographical data on translations at that time. Focusing on these issues is understandable, considering the scarcity of book documentation and comprehensive bibliographies, an issue which has been acknowledged by even more recent studies on the Saudi context, such as Alkhamis (2013), Alsiary (2016), and Alshehri (2019, 2020).

The emergence of the KFNL bibliography of translated books in 2008 has opened avenues for translation researchers in KSA to conduct socio-historical investigations of translations, as seen in the work of Alkhamis (2013) (Section 2.1). However, one critique of Alkhamis’s work is the lack of systematic verification of the bibliographical data used in the study. Although Alkhamis (2013, pp. 20–21) discusses that numerous translations produced by governmental bodies are not listed in the KFNL bibliography (2008), he does not provide a solid solution for how to solve such a methodological issue, which impacts the sociological definition of the field’s agents, production, and practices.

Therefore, Alsiary (2016), who maps the field of children’s literature translation in KSA (Section 2.1), recognises this issue and criticises the exclusion of many children’s book translations from the KFNL bibliography (2008). Consequently, she deems it necessary to consult numerous other resources to compile and verify her bibliography. However, despite employing Bourdieu’s theory of social practice as an analytical framework, Alsiary’s focus on verification leads to less emphasis on the socio-cultural and historical context of the translations and the mapping of the field, in comparison to Alkhamis (2013). This places translation researchers in a dilemma: either to prioritise socio-historical analysis with minimal data verification or to focus on verifying the data at the expense of the depth of socio-historical investigation.

Building upon these insights, this study not only addresses the limitations of prior research but also takes advantage of recent major developments in the field of translation bibliographies in KSA. The first major development is the emergence of the Saudi Observatory on Translated Publications (Alshehri, 2022), which offers a bibliography of 7,611 translations from and into Arabic published in KSA between 1932 and 2016. This bibliography is the most comprehensive in terms of temporal coverage and the range of resources and databases consulted. The other major development is the emergence of the Arabic Union Catalog, which provides a catalogue with 14,121 entries of translations published in KSA, surpassing the combined numbers of the KFNL bibliography (2008) and the Saudi Observatory on Translated Publications (Alshehri, 2022).

Through the investigation of the field of Arabic Translations of English self-help books in KSA from 1982 to 2016, significant potential is recognised in this study in employing Bourdieu’s field reciprocally with bibliographical research for both data verification and the enhancement of socio-historical analysis. The aim is to bridge the gap and support the researcher’s difficult choice between bibliographical data accuracy and deep socio-historical investigation. The following section discusses the compilation and filtering of bibliographical data, which is, at the same time, a way to define the field’s boundaries, including its translation agents and production.

3 The Field’s Definition: Arabic Translations of English Self-Help Books in KSA from 1982 to 2016

For Bourdieu, the boundaries of a field can be defined by the positions and interactions of various agents within it. In the context of translation fields, Bourdieu’s concept can be applied practically through the identification of translation agents and products, which help in identifying all other components of the field. Building on Khalifa’s work (2017), this article suggests considering the definition of the genre, the languages of both the source and target texts, the spatial location, the temporal period of the genre under study, and the translation medium for defining a particular field of translation.

This can begin by suggesting field descriptors that consider the above parameters, such as “Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA from 1982 to 2016.” Each descriptor within this hypothesised field serves to delineate the field’s boundaries. However, it is important to note that these descriptors are not fixed but can evolve continuously during bibliographical research. New data may reveal additional translation agents or products that influence the socio-historical boundaries of the field. This socio-historical framing is designed to transform Bourdieu’s theoretical concept into a more quantifiable instrument for establishing boundaries within this translation field. The following are a deconstruction and reconstruction of these descriptors, aimed at proposing a definition that outlines the scope of the field’s bibliographical data, through which its boundaries are delineated. This approach makes it easier to identify the field’s production, agents, and socio-historical contexts.

3.1 The Descriptors “Self-Help” and “English”

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “self-help” as follows:

The action or faculty of using one’s own efforts and resources to achieve something, or provide for oneself, with little or no assistance from others; (in later use) specifically the action of managing or overcoming personal or emotional problems in this way.

However, the term is frequently used in a more general sense to describe various non-fiction works that have evolved over the past few centuries, mainly in the American and Anglophone social contexts (Dolby, 2008, p. 35). For instance, the Barnes and Noble website categorises over 241,000 books as self-help, spread across 77 subcategories ranging from personal growth, psychological self-help, emotional healing, and inspiration, to relationships, dating, love and romance, weddings, marriage, divorce, and sexuality, and extending to addiction and recovery, ageing, death, and dying. However, books on other topics such as spirituality, medicine, environment, science, creativity, and business were intentionally excluded from Barnes and Noble’s self-help categories.

The lack of clarity in categorisation and definition of what can be called self-help is also prevalent in academic circles. For instance, The Authoritative Guide to Self-Help Books (Santrock et al., 1994) categorises 1,000 works as self-help books. It defines self-help books as “written for the lay public to help individuals cope with problems and live more effective lives” (Santrock et al., 1994, p. 4). On the other hand, Ad Bergsma (2008, p. 343) argues that any book that serves the practical purpose of assisting individuals in dealing with emotional or personal matters ought to be regarded as self-help. Therefore, any book can be classified as self-help if the reader perceives it as such.

Dolby (2008) proposes a definition of self-help books that falls between the two aforementioned definitions. He suggests that self-help books differ from other genres of popular literature by virtue of their unique combination of self-improvement content, informal and rhetorical style, general problem and solution structure, and educational function (2008, p. 37). Dolby’s modified version of Santrock et al.’s definition is as follows:

Self-help books are books of popular nonfiction written with the aim of enlightening readers about some of the negative effects of our culture and worldview and suggesting new attitudes and practices that might lead them to more satisfying and more effective lives. (2008, p. 38)

This study therefore adopts Dolby’s definition (2008) as the most precise descriptor of self-help literature.[1] It serves as a guiding principle for the selection of self-help books in the bibliography of this research. It ensures that overlaps with other literary and non-literary writings, such as biographies, autobiographies, storytelling, philosophy, sacred texts, and psychological and sociological writings are minimised, thereby maintaining the consistency of the self-help literature.

The definition is also used to outline the scope of the self-help literature in this study. Self-help content can have various forms. It can be spoken (e.g., videos, talks, training courses, and groups) or written (e.g., books, articles, and leaflets). However, the bibliography produced for this study focuses on Arabic translations in KSA of original English self-help books that were published with an International Standard Book Number (ISBN) in their countries of origin. By narrowing the scope to these criteria, the availability of controlled and valid data for analysis is ensured.

The term “English,” which here refers to the language rather than the nationality, is as problematic as the previous term, “self-help.” Factors such as the writer’s nationality, the country of publication, and the original language of the source text could be potentially considered. Considering these and similar examples, the definition of “English” in relation to self-help literature is multifaceted. This study’s bibliography includes all Arabic translations published in KSA of original or translated English self-help books published in any country that fit the definition of self-help literature adopted in this study. Section 3.4 of this article elaborates on the practical implementation of this definition within the context of bibliographical research.

3.2 The Descriptors “Arabic Translations” and “in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA)”

The last two terms, “Arabic translations” and “in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA),” have relatively clear definitions compared to the previous terms. In this study, they refer to any Arabic translation of an English self-help book that has been published as a book with an ISBN by a Saudi publisher within the geographical boundaries of KSA, irrespective of the nationality of the translator.

3.3 The Descriptor “from 1982 to 2016”

This study examines all translations published in KSA from 1932 – the year of the country’s unification – to 2016. The decision to conclude the timeframe of this study in 2016 was based on various factors, including the significant social, cultural, political, and religious changes introduced in KSA with the launch of the country’s new vision, “Saudi Vision 2030,” in 2016. These changes had a profound impact on the structure of the Saudi social space, necessitating a focused independent investigation to comprehend their implications. However, while the socio-historical mapping covered a longer period before 1982, the field is framed precisely between 1982 and 2016 to indicate the first Arabic translation of an English self-help book published in KSA and the end period of the analysis. A total of 993 Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA have been identified during this period. This timeframe provides a comprehensive understanding of the field within the context of the socio-historical transformations that occurred before and during this period.

These various descriptors were designed to compile a thorough bibliography by establishing clear boundaries for the field. However, questions remain about the comprehensiveness of the definitions used and the inclusivity of self-help translations in the bibliography. This article considers Anthony Pym’s concerns (1998, pp. 41–47) regarding the challenges of constructing historical analyses using pre-existing translation lists and bibliographical databases, such as catalogues compiled by publishers or libraries, which may restrict research scope and fail to fully capture the diversity of translations. He underscores that most operational definitions and lists in translation history are contingent upon prior selection criteria, necessitating critical engagement and potential adjustment by researchers (Pym, 1998, pp. 41–47). Therefore, A thorough examination of the descriptors and their definitions was conducted, ensuring that the data were compiled and verified. This process involved consulting multiple bibliographical resources, studies, and catalogues, as well as engaging in personal communication to represent the studied field accurately, as detailed in the following sections.

4 Transforming Theoretical Field Descriptors into Practical Bibliographical Boundaries

4.1 Identification of the Required Bibliographical Data

Turning the theoretical definition of the field’s descriptors into tangible boundaries through bibliographical research represents the second crucial empirical step in defining the field’s boundaries. This process aids in identifying the field’s agents, products, and practices, while also providing insights into its overall history and trajectory. To map the field of Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA, several categories of bibliographical data were identified as necessary to collect for both the translations and their English source texts. For the translations, they were: (1) the title, (2) the date of publication, (3) the translator, (4) the publisher, and (5) the link to websites containing images of the front and back covers. For the source texts, they were: (1) the title, (2) the date of publication, (3) the author, (4) the publisher, (5) the country of publication, and (6) the link to websites containing images of the front and back covers. These specific types of data are essential for understanding the field’s history, trajectory, agents and their practices, production, historical phases, and characteristics.

4.2 Identification of the Existing Bibliographical Resources

After identifying the required bibliographical data for defining the field, the next step in this empirical research involves identifying the existing bibliographical resources and databases. This includes examining their completeness and validity for defining the boundaries of the field. The present research incorporates the existing studies and bibliographies that have collected and discussed translations published in KSA, mentioned above, including Alnasser (1998), El-Khoury (1988), Halbawi (1987), the KFNL bibliography (2008), and the Saudi Observatory in Translated Publication (Alshehri, 2022). While these bibliographies are useful, the data they provide on the Arabic translations published in KSA are incomplete and fragmented, lacking information on the source texts altogether. To address this limitation, extensive research was conducted using online resources and catalogues to verify and complete the available bibliographical data. These included the catalogues of KFNL (2008), King Abdul-Aziz Public Library, Barnes & Noble, the Arabic Union Catalog, online catalogues of large publishers such as Jarir and Obeikan, WorldCat, the UNESCO Index of translations (Translationum), the British National Bibliography, Google Play Books, Google Books, Goodreads, Google Image, Amazon, Abebooks, and ThriftBooks. Also consulted were the online catalogues of publishers of the source texts, such as Simon & Schuster, HarperCollins, McGraw-Hill, Wiley, Thomas Nelson, Taylor & Francis, Pearson, Hachette Book Group, and Penguin Random House. The collection and filtering of bibliographical data in this study went beyond simple compilation and assessment of bibliographical data, to the development of a more in-depth understanding of the field’s dynamics, activities, and agents.

4.3 Compilation, Filtering, and Digitalisation of the Bibliographical Data

After the initial steps outlined above, the focus shifts to conducting real empirical bibliographical research of the data using all available resources mentioned previously. This involves filtering and validating the existing bibliographical data while also addressing any missing or incomplete bibliographical data required. The objective is to collect as much complete and accurate data on the field and translations as possible, as the field boundaries will be defined according to this bibliographical data.

All works translated into Arabic and published in KSA between 1932 and 2016 – totalling more than 5,000 titles – have been filtered to identify the self-help translations among them. The filtering of the translations includes: (1) the translation’s title, which serves as an initial indicative signal of the translation’s relation to the definition of self-help literature, although it could at times be ambiguous; (2) the publishers’ classifications of the source text and the translation, which were considered to determine whether the translation fell under the category of self-help literature; (3) keywords found in the source text and in the translation’s bibliographical card, which provided further insight; (4) if these three steps did not result in a definitive classification of the translation, the author’s preface, the translator’s introduction, the publisher’s introduction, and the book’s blurb were examined. Finally, if the results of these four steps were inconclusive, the language in which the translation is written and its content were briefly examined, as these frequently indicate how closely related the translation is to self-help literature. By the end of this stage, 993 translations had been identified as self-help translations through cross-referencing all previous translation bibliographies, databases, and catalogues with the publishers’ lists and catalogues. These translations met the criteria based on the definition of the translation field of this study given in Section 4.

The compiled bibliographical data were organised using Microsoft Excel, which has proven to be highly effective in compiling, verifying, and filtering bibliographical data. However, one limitation of Excel is its inability to support photographic data, making it impossible to store images of the covers of translated books. Despite this limitation, Excel has been effective in examining bibliographical data due to its analytical features. It is important to acknowledge that the compilation, filtering, and verification of the data were time-consuming, particularly given the large number of self-help book translations discovered. The magnitude of these findings was unexpected, as previous studies and bibliographies did not indicate such a high number of self-help book translations in KSA. The lack of crucial bibliographical information, including publishing dates, translator names, and details about source texts – particularly in the case of older self-help book translations – presented additional obstacles and time pressures during the verification and digitalisation processes. Furthermore, the absence of standardised bibliographical practices added complexity to the verification and digitalisation.

5 Mapping and Bounding the Field

5.1 Initial Findings of the Field

While the history of book translation into Arabic in KSA dates back to the early 1950s (Alshehri, 2019, p. 165), the first documented Arabic translation of an English self-help book into Arabic in KSA was only published in 1982, according to this study’s bibliographical database. Only 68 translations into Arabic were released by private publishers in KSA between 1951 and 1982 (Alshehri, 2019, p. 170). Even though Arabic translations of English self-help books were introduced in KSA later than some other genres, it was still one of the first types of literature to be introduced in the country. However, in comparison to the introduction of Arabic translations of English self-help literature in other Arabic-speaking states – which dates back to the early 1880s (Alkheder, 2013, p. 55)[2] – its history in KSA is relatively new.

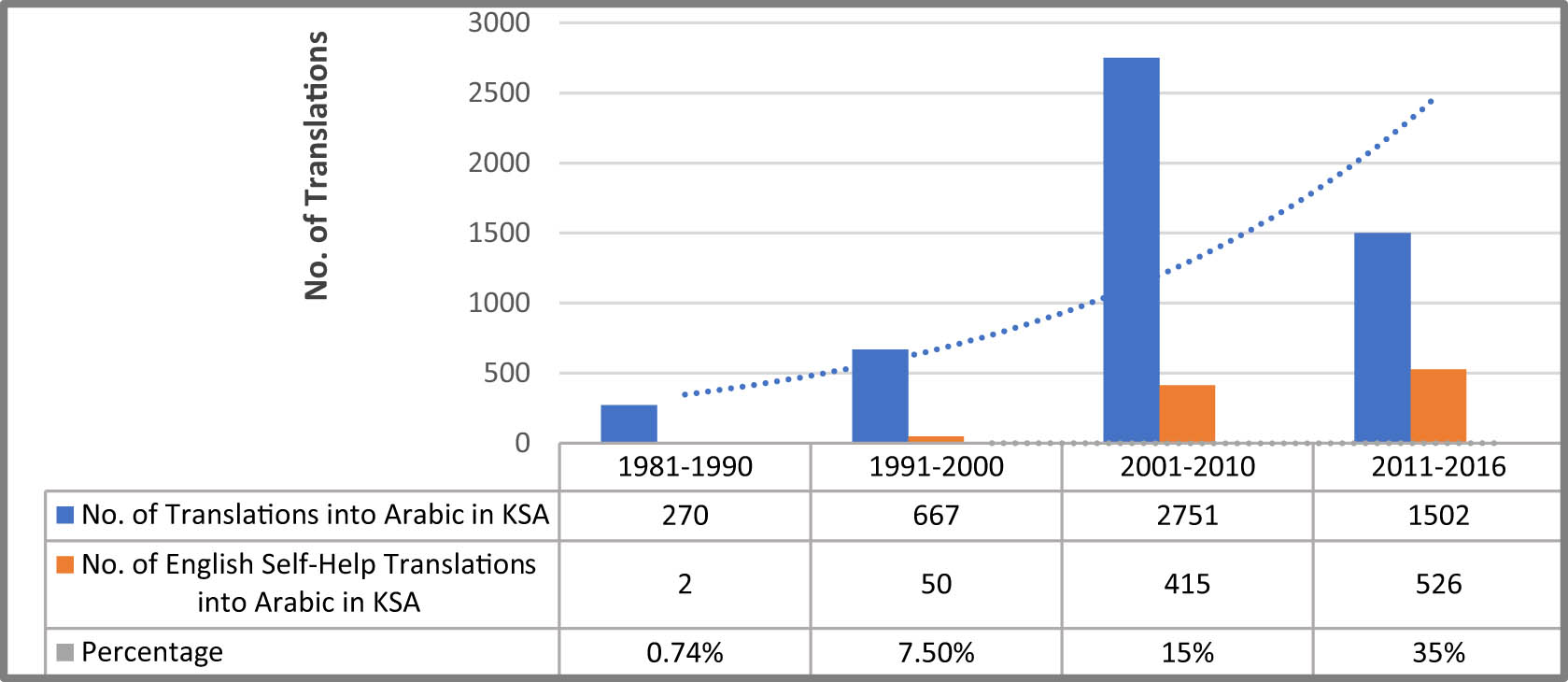

Based on the findings of this study’s bibliographical database, the total production of Arabic translations of English self-help books represents 18.5% of the entire Saudi production of Arabic translations in KSA from 1932 to 2016. By the end of the 1990s, English self-help literature translated into Arabic in KSA accounted for only 0.74% of the overall translation production in the country during the same period. This production increased to 7.5% by the end of the next decade, in 2000, reaching 15.1% by the end of the following decade, in 2010, and rose to 35% by 2016, as shown in Figure 1.

Ascending curve of the production of Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA compared to the overall translations published in KSA. The data were extracted from a comparison of the bibliographical database compiled for this study with the already available databases.

The findings of this study allow us to identify the key agents in the field during its two distinct phases of production. The first phase (the emergence phase) occurred between 1982 and 1998 and was characterised by relatively low production of translated works, with only 25 recorded translations.[3] During this phase, five institutional agents were identified in the form of publishers: Dar Al-Refaey (Al-Refaey, with one translation), Dar Al-Mutaman (Al-Mutaman, with two translations), International Ideas Home (IIH, with 18 translations), Dar Al-Faisal (Al-Faisal, with one translation), and Institute of Public Administration (IPA, with three translations). Three individual translators were also identified: Abdullmun’im Al-Ziyadi, Ahmad Al-Mohandes, and Sami Salman. These agents all played active roles in introducing translated self-help literature into Arabic in KSA. In the first phase, production was characterised by (1) less competitiveness, (2) less organisation, and (3) limited recognition among publishers and translators of the works as translated self-help literature. Additionally, the production was (4) mainly introduced by external translation agents, and (5) not numerous. This phase is described in this study as “the emergence phase,” wherein the field is considered a subfield of the Saudi publishing industry conditioned by its logic.

On the other hand, the second phase (the flourishing phase) – spanning from 1998 to 2016 – was characterised by a significant increase in the production of translations, with 968 out of the 993 documented translations being produced during this period. In this phase, five institutional agents (publishers) were identified: Jarir Bookstore (Jarir, with 829 translations), Obeikan Bookstore (Obeikan, with 79 translations), Al-Shegrey for Publishing & Information Technology (Al-Shegrey, with 16 translations), Dar Al-Marifa for Human Development (Al-Marifa, with 27 translations), and Dar Al-Maiman (Al-Maiman, with 17 translations). These contributed to the formation of the field of Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA as an independent field with its own structure and agents. This phase witnessed (1) the emergence of new indigenous translation publishers, (2) a significant increase in the translation of self-help literature, (3) widespread recognition of self-help literature as an independent translated genre among publishers and translators, (4) increased organisation and stability in production, and (5) clearer translation practices among the agents. During this phase, the field became more distinct, with its own dominant and dominated agents competing for different forms of capital by employing various position-takings and strategies.

5.2 Illustration and Visualisation of the Field’s Definition and Boundaries

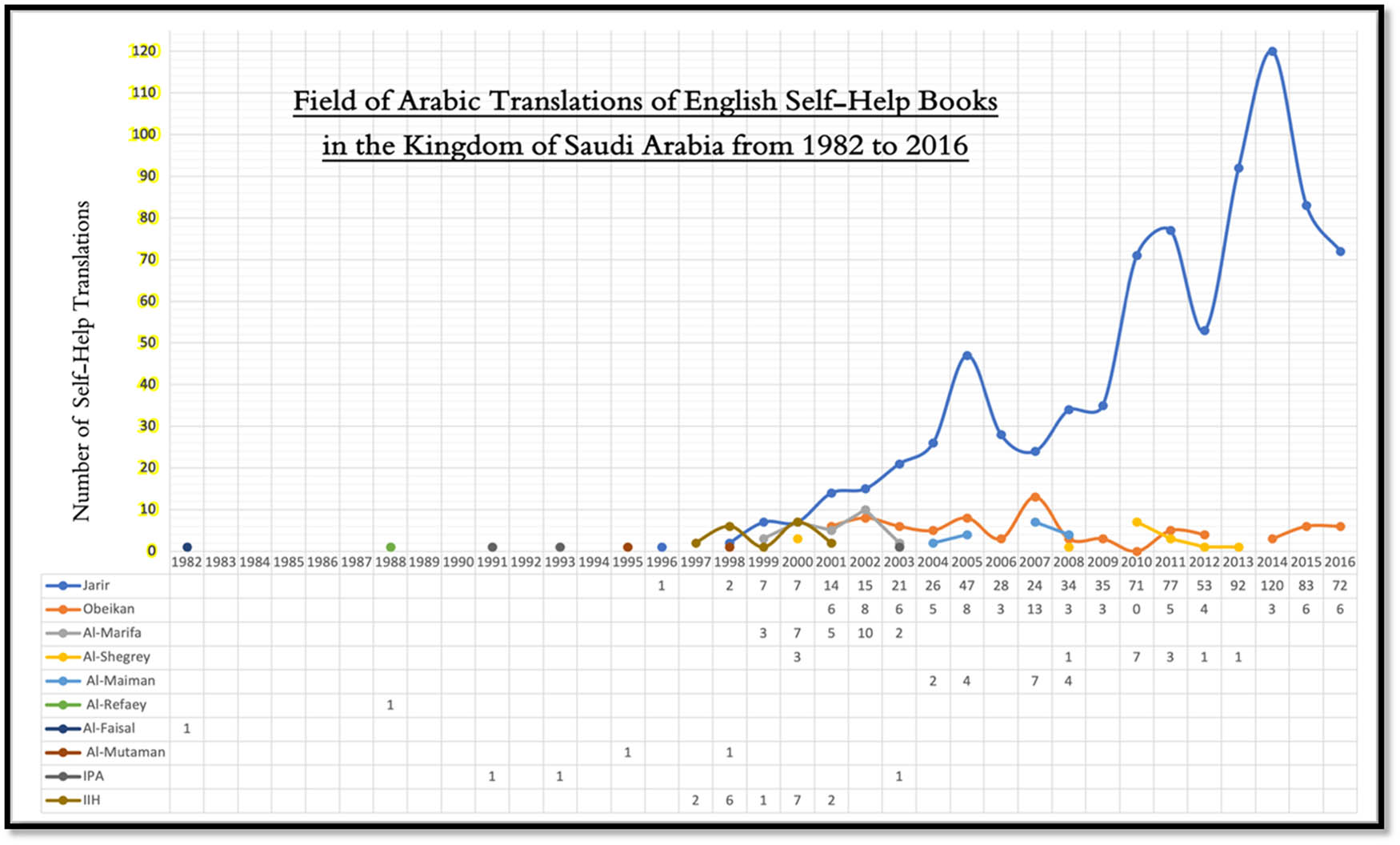

Based on the above analysis of the bibliographical database compiled on the field and cross-referenced with resources and literature on the Saudi socio-historical context, suggested boundaries can be drawn visually. The aim is to incorporate the field’s trajectory, agents, and production within their wider sociological context, including the socio-historical events and factors that impacted the field’s emergence and development. The following sections delineate various conceptual representations (metaphorically referred to as maps) of the field, inspired by Bourdieu’s concept of the social field and informed by the compiled bibliographical database on the subject. It is important to note that this article does not aim to analyse the translation field under study fully but rather to delineate its boundaries, showcasing how these can be set using Bourdieu’s notion of field. The first map (Figure 2) displays a timeline of the field’s trajectory and the agents’ production from 1982 to 2016. This map serves as a starting point from which the statistical data can be linked to other socio-historical information.

Chronological trajectory of publishers’ self-help translation production across the period from 1982 to 2016.

This map defines the fields’ and the agents’ chronological trajectories through the verified bibliographical data on the translation agents, products, and chronological context. This definition provides some socio-historical context by positioning this translation field, agents, and products within their specific historical context. However, this context alone is not enough to conduct a socio-historical analysis of the field. Crucially, the wider socio-historical contexts and boundaries that impact the field must also be recognised.

These wider contexts can be divided based on Bourdieu’s understanding of the field into two levels. The first level includes the most relevant social fields that encompass the field under study and from which it emerged. In this article, the field of Arabic translations of English self-help Books in KSA from 1982 to 2016 can be seen as emerging from the Saudi publishing field, and is therefore influenced by its logic and practices. This is because almost all the translations in question are produced by private publishers. This perspective is supported by the findings of Alkhamis (2013, pp. 53, 97) and Alshehri (2019, pp. 165–173) that private publishing companies are more active in translation than public or governmental academic and literary institutions. Viewing a translation field as a sub-field of a larger field – such as the publishing field in that specific geographical context – is endorsed by Thompson (2010, p. 4), who employs Bourdieusian concepts to define the Anglo-American book market as a field. Thompson concludes that the publishing field is not one field but rather “a plurality of fields, each of which has its own distinctive characteristics” (2010, p. 4). Therefore, while this study considers its field to be independent, particularly during its flourishing phase (from 1998 onwards), it aligns with the conclusions of Alkhamis and Alshehri that translation in KSA is influenced by the logic of the field of the Saudi private publishing industry.

The second level includes the wider social fields that govern all cultural fields, which Bourdieu refers to as the fields of power. According to Wacquant (1992, p. 18), the field of power for Bourdieu must be conceived of at a higher level than other fields, such as the fields of cultural production, because it partially encompasses them. It should be viewed more as a “meta-field” with various emergent and unique properties (Wacquant, 1992, p. 18). According to Bourdieu, the fields of cultural production are influenced by the fields of power, namely the economic and political fields. Fields of cultural production are positioned within fields of power, and their rules and practices are subject to the laws of economic profit and political gain (Bourdieu, 1993, p. 39). For this study, the Saudi religious field has been added to Bourdieu’s political and economic fields of power to define the socio-historical impact, due to its substantial influence on all fields of cultural production in KSA, including that under the analytical lens of this study.[4]

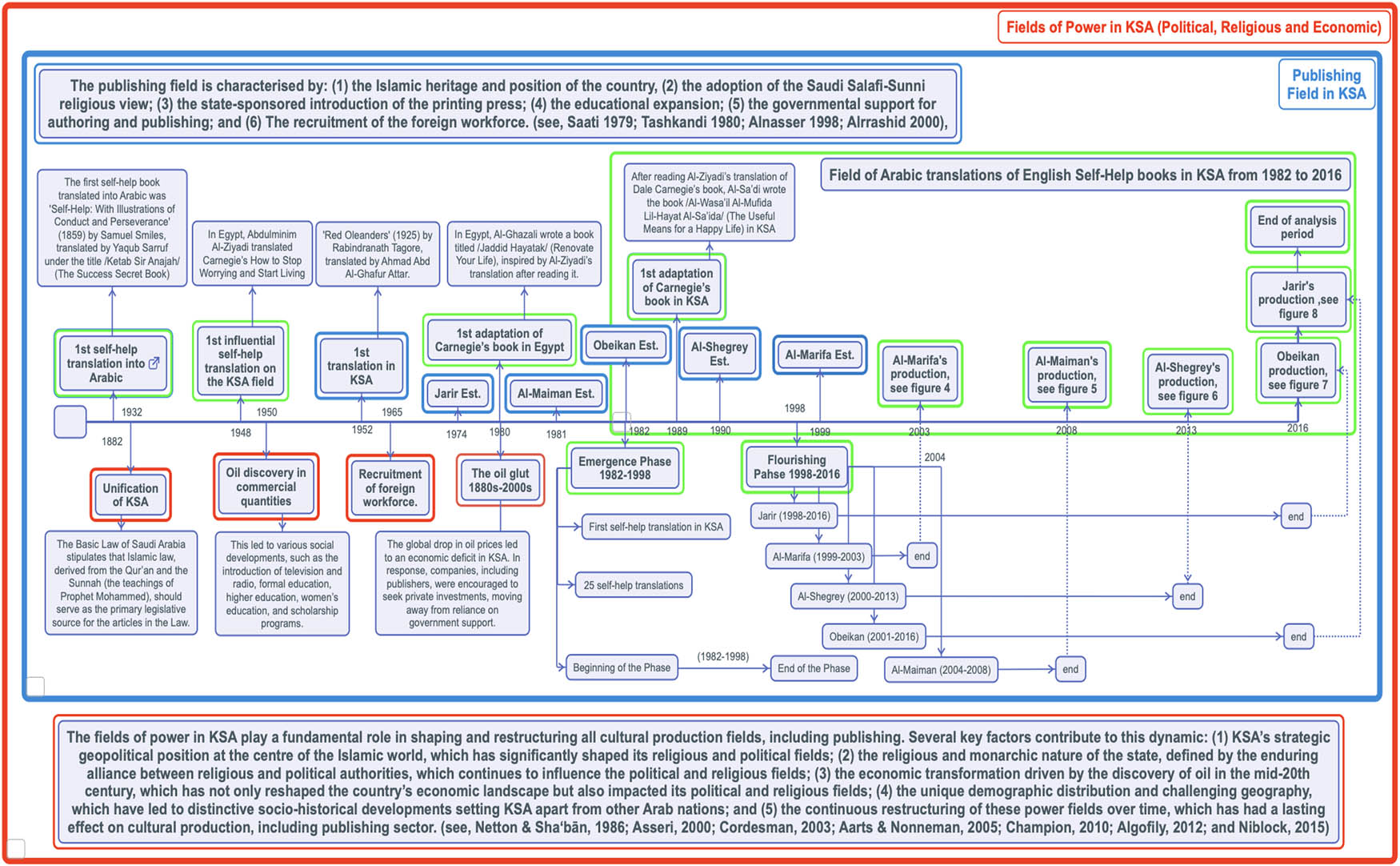

The following field map and definition (Figure 3) chronologically situate the field’s trajectory and the agents’ production within the most relevant socio-historical events and factors of the encompassing field – the Saudi publishing field. This includes the establishment years of publishing houses, the earlier translations, and the translators that contributed to the field’s emergence and development. Also under consideration here are the other significant socio-historical events and factors that characterised the parent publishing field. Additionally, this map situates the field’s trajectory and the agents’ production within those social-historical events and factors emanating from the fields of power in KSA that had an impact on all Saudi cultural production fields. It chronologically links the field’s emergence and developments to the wider political, religious, and economic factors and events that (re)shape its overall trajectory, as seen in Figures 3–8.

Suggested socio-historical map and boundaries of the field of Arabic Translations of English Self-Help Books in KSA, positioned within the Saudi publishing field and influenced by the fields of power.

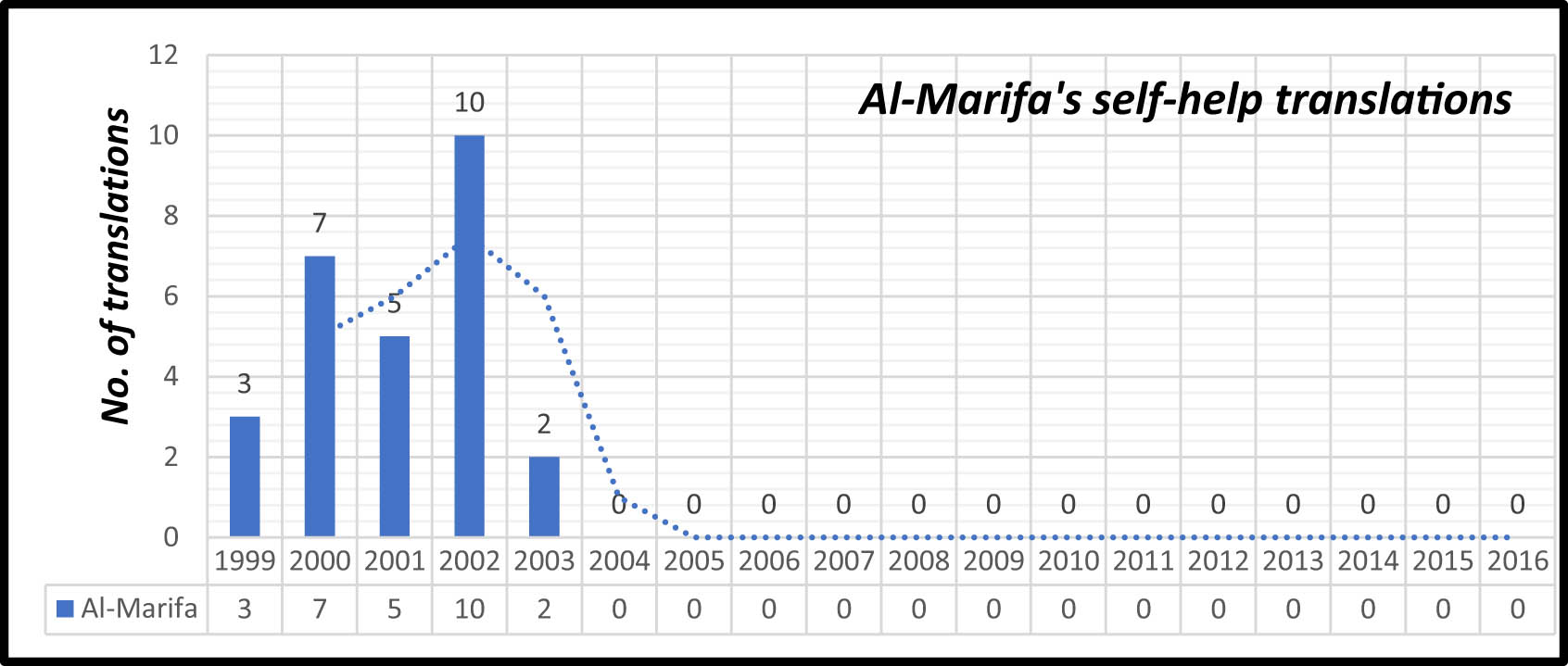

Chronological trajectory of Al-Marifa’s production of self-help translations.

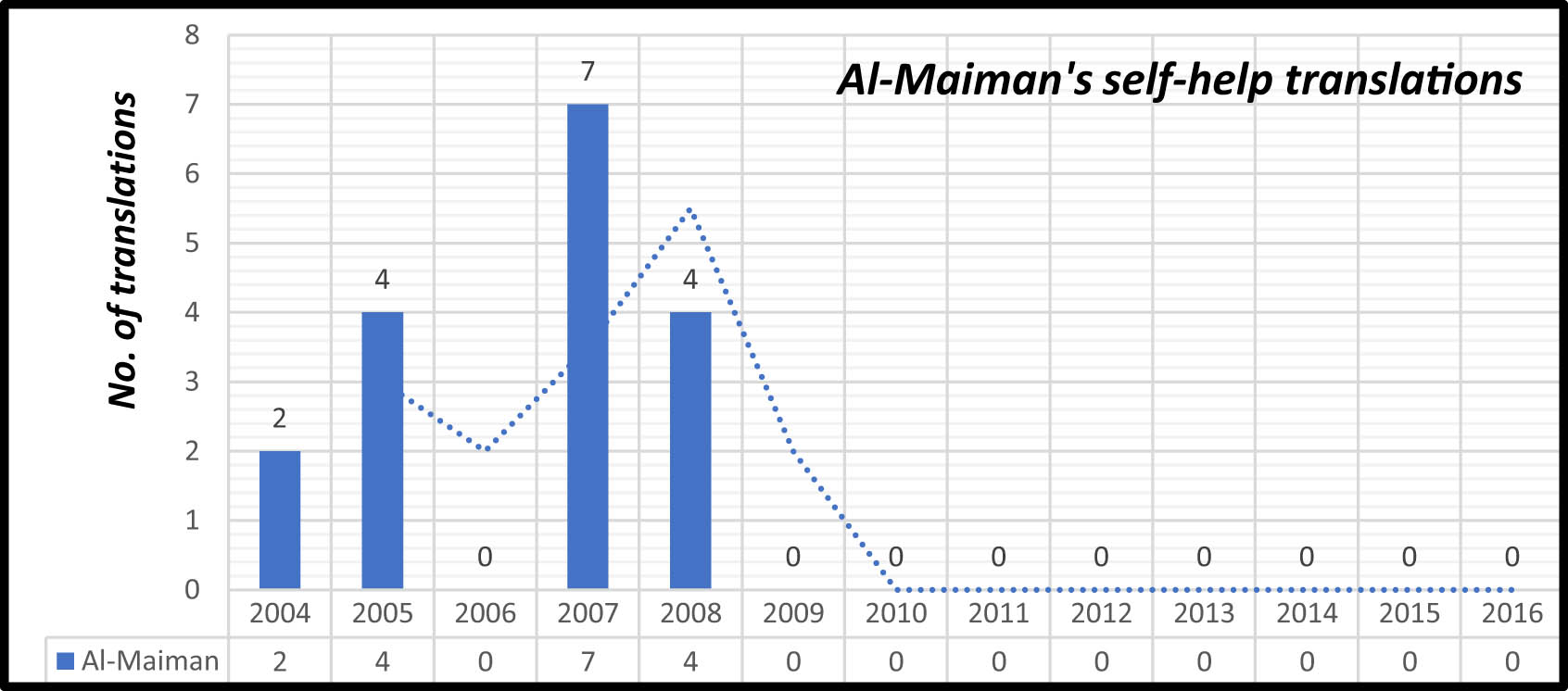

Chronological trajectory of Al-Maiman’s production of self-help translations.

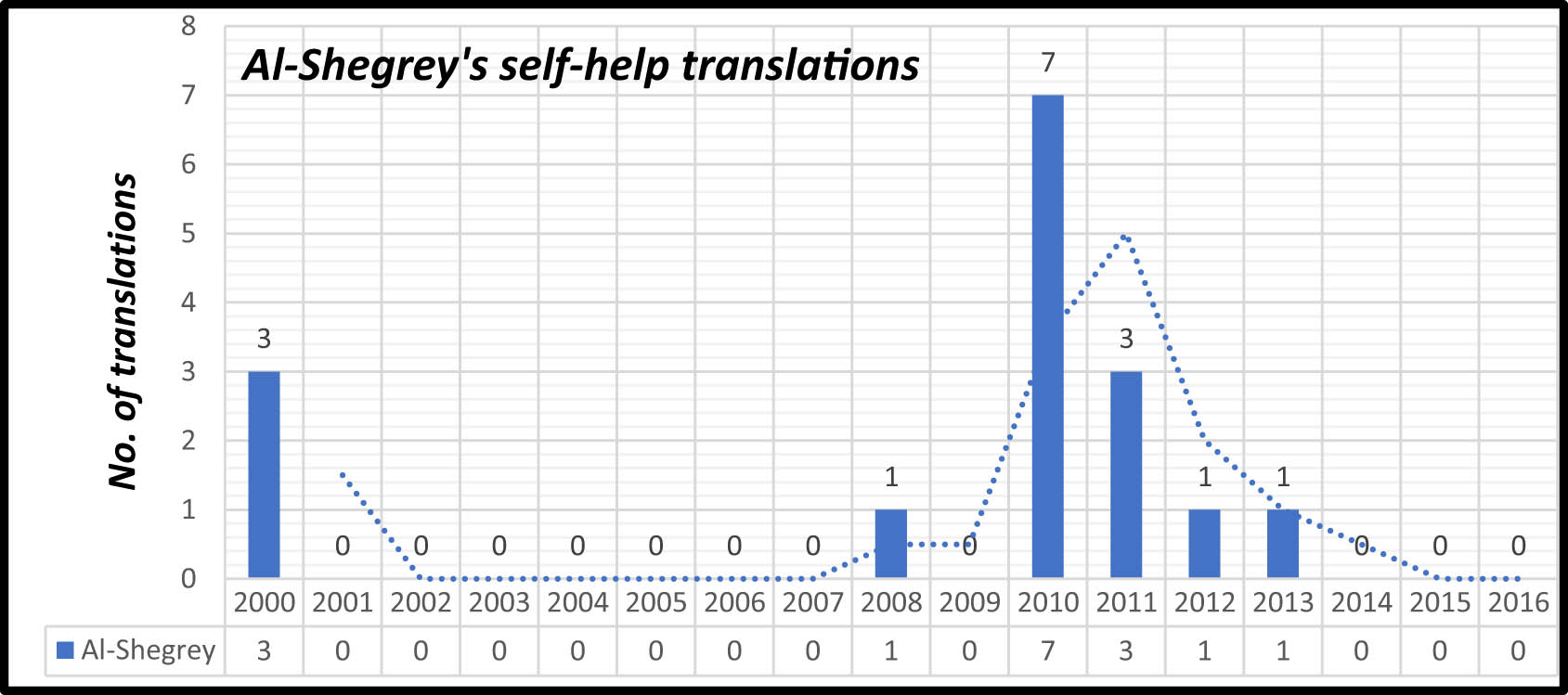

Chronological trajectory of Al-Shegrey’s production of self-help translations.

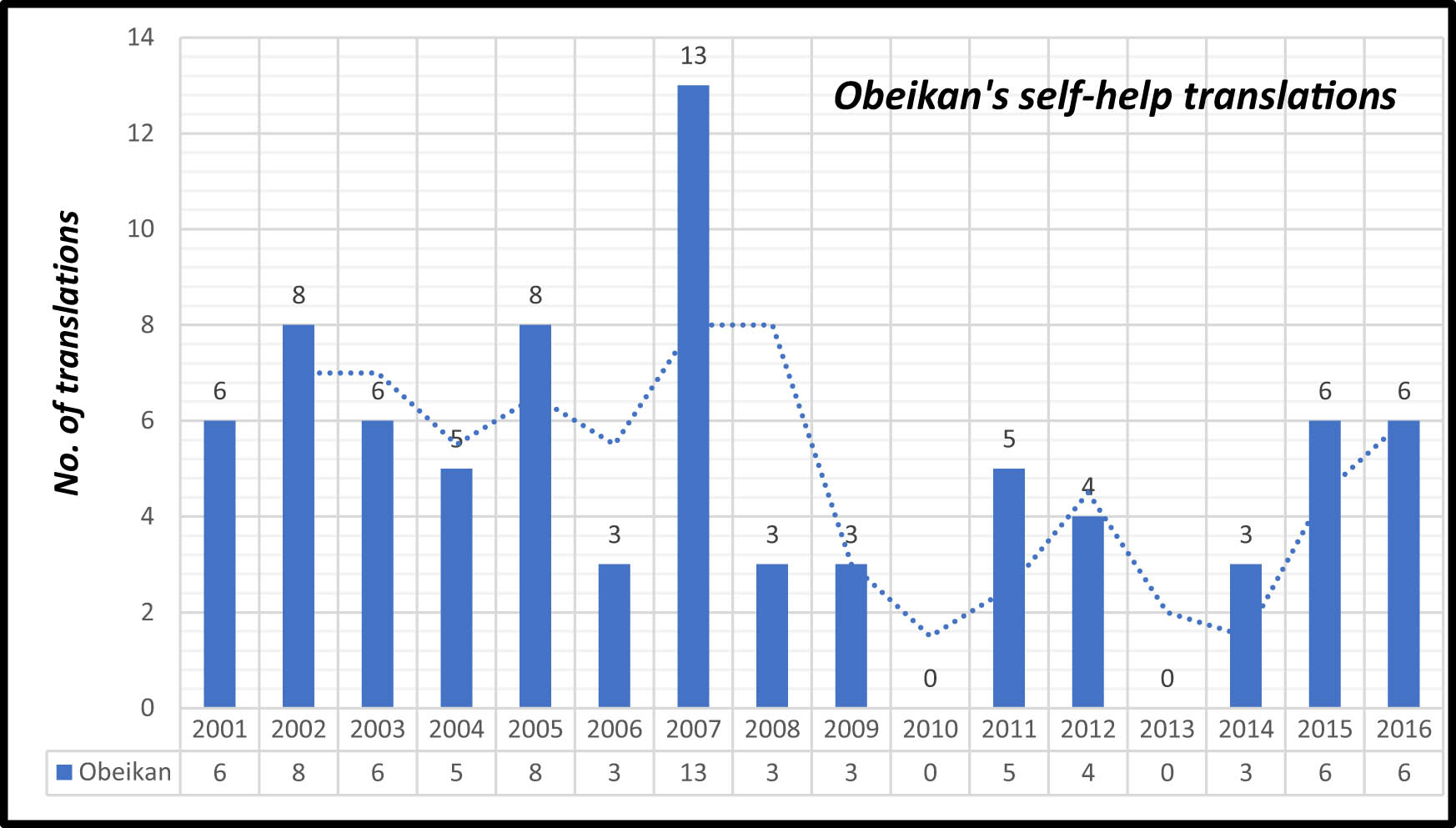

Chronological trajectory of Obeikan’s production of self-help translations.

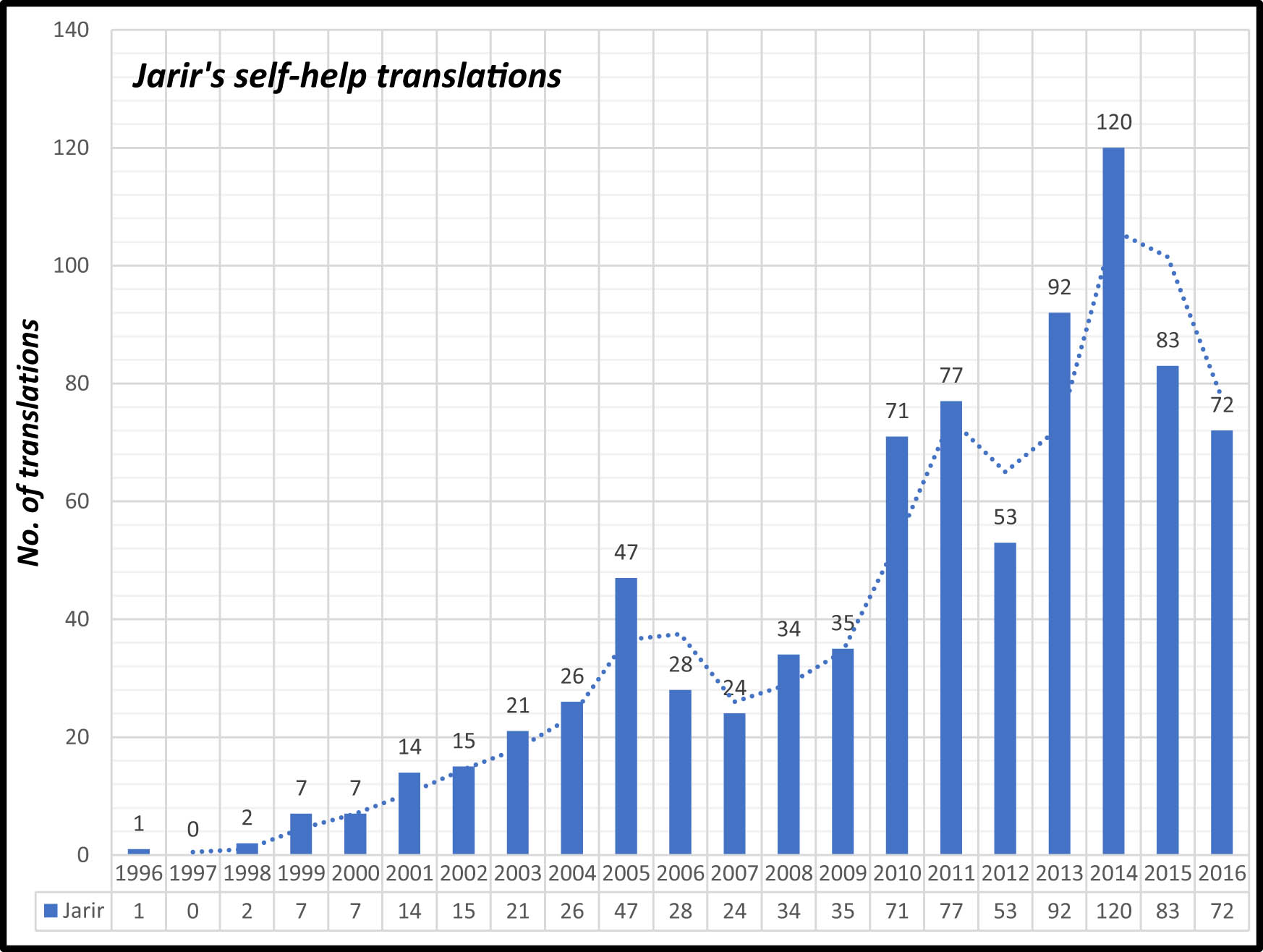

Chronological trajectory of Jarir’s production of self-help translations.

This map (Figure 3) can be divided into three rectangles or fields of socio-historical contextualisation. The green rectangle signifies the field of Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA. This rectangle includes the field’s trajectory, chronological phases, agents, and production from 1982 to 2016. Within this rectangle, researchers can map and discuss any socio-historical events and factors that directly related to and impacted the field, agents, production, and practices. Linked to the large green rectangle are the small green rectangles, which signify the pre-emergence socio-historical factors and events that subsequently had a direct impact on the field’s emergence and introduction. Before 1982, several socio-historical factors and events related to the field, such as those originating from counterpart fields in other Arab countries, contributing to its emergence and development. This study considers, for instance, but is not limited to, the first self-help translation into Arabic published in Lebanon and Egypt, dating back to 1882, and the first self-help translations and adaptations published in Egypt but sold in KSA or read by Saudis. These socio-historical factors and events served as the initial catalysts for the field’s emergence in KSA.

The blue rectangle in the map represents the Saudi publishing field, within which the field under study (the large green rectangle) is situated. This encompasses the factors and events originating in the Saudi publishing field that later influenced the emergence and development of the field under study. This includes events (in blue) such as the publishers’ respective establishment dates and the first translations published in KSA. The blue rectangle on the map also delineates the characteristics of the Saudi publishing field as discussed in various studies (e.g., Alnasser, 1998; Alrrashid, 2000; Saati, 1979; Tashkandi, 1980), which encompass (1) the Islamic heritage and position of the country, (2) the adoption of the Saudi Salafi-Sunni religious view, (3) the state-sponsored introduction of the printing press, (4) the expansion of education in KSA, (5) the governmental support for authoring and publishing, and (6) the recruitment of the foreign workforce.[5] These features are influenced by the red rectangle, which represents the fields of power (political, religious, and economic).

The fields of power in KSA (the red rectangle) are characterised by several features as discussed in various studies (e.g., Aarts & Nonneman, 2005; Algofily, 2012; Asseri, 2000; Champion, 2010; Cordesman, 2003a, b; Kay, 1982; McLachlan, 1986; Netton & Shaʻbān, 1986; Niblock, 2015). The country’s geopolitical position in the heart of the Islamic world has profoundly shaped its religious and political fields of power. The religious and monarchic nature of the State, exemplified by the coalition between religious and political agents, has significantly influenced these fields. Additionally, the dramatic economic changes resulting from the discovery of oil in commercial quantities in the 1950s and the oil glut in the 1980s to early 2000s have not only (re)shaped the country’s economic field of power, but also impacted its religious and political fields. Finally, the unique demographic distribution and challenging geographical features of the country – which have led to distinct socio-historical developments, setting it apart from other Arab nations – have an impact on the overall (re)structuring of the fields of power in KSA.[6] This structuring and restructuring in the fields of power throughout Saudi Arabia’s history have played a pivotal role in (re)shaping all the fields of cultural production in KSA, including the publishing field explored in this study.

This delineation of its boundaries and structure can facilitate robust socio-historical investigations of the translation field under examination. Many individual, collective, and comparative forms of socio-historical discussion may be facilitated by understanding this field’s definition, map, and boundaries. This can include discussions on the levels of translation agents and agency, translation process and production, translation motivations, and translation socio-historical contexts.

6 Final Remarks and Conclusion

This article sought to advance the application of Pierre Bourdieu’s field theory in translation studies by proposing a methodological framework grounded in bibliographical research. By integrating Bourdieu’s field with empirical data, the study has aimed to answer the key research question: How can Bourdieu’s field theory be integrated with bibliographical research to enhance data verification and sociological analysis in the study of the field of Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA? This study has sought to elucidate the boundaries, agents, and production within the field of Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA from 1982 to 2016. Through the compilation and Bourdieusian analysis of a bibliographical database comprising 993 self-help translations published in KSA, this article has demonstrated how Bourdieu’s field can be integrated with bibliographical research as reciprocal frameworks to socio-historically delineate and map a translation field, such as the one examined here.

Firstly, Bourdieu’s concept of field has been socio-historically implemented to (re)define the scope of the bibliographical data of the studied translation field. This includes the definition of the genre under study, the languages of both the source and target texts, the spatial location, the temporal period of the genre under investigation, and the translation medium. The article defined the Arabic translations of English self-help books in KSA not only as a translated literary genre but also as a social product of activities conducted by social agents within a social field. Therefore, the article ensured adopting an inclusive yet accurate definition of the genre, as suggested by Dolby (2008, p. 38). The article also defined the languages and the geographical contexts of the source texts (English language in the Anglophone context) and of the target texts (Arabic language in the Saudi context). Such precise definitions ensured the accuracy of the socio-historical contextualisation of this translation field.

Considering a variety of geographical contexts for both source and the target texts can have a negative impact on the accuracy and validity of the bibliographical data and, therefore, the accuracy and validity of the socio-historical analysis of the translation field. However, this study acknowledged the influence of other Arabic contexts whensoever they are relevant to the field under investigation, as Saudi social fields are impacted by their wider national and transnational Arab socio-cultural contexts.

The temporal boundaries of the field were left flexible during the definition process to accommodate updates from bibliographical findings, which could potentially redefine the field’s temporal boundaries. The temporal period was also extended to cover the period prior to the field’s emergence (from the 1880s to the early 1980s), as the field had not emerged in a vacuum but rather in response to socio-historical events, factors, and developments occurring in other prior relevant social fields and fields of power.

Secondly, by applying Bourdieu’s field, this study was able to identify the necessary types of bibliographical data required for defining the field’s boundaries. It was crucial to integrate bibliographical data on the social agents involved (translators and publishers in this case), their social products and activities (translations), and the social contexts (chronology of events, locations, and social conditions and factors) within which the agents operate and produce their products. This definition greatly assisted in determining the required bibliographical data, without which socio-historical analysis would be challenging. Therefore, I endeavoured to include information on translation co-producers (publishers, translators, and supervisors), details of translations (titles, dates, numbers, themes, editions, and covers), and information about the original texts (titles, authors, dates, editions, and covers). This enabled a more socio-historically-originated compilation and verification of the data needed for this study.

Thirdly, building on the compiled self-help bibliographical data and Bourdieu’s concept of field, this study was able to draw an initial map and boundaries of the field’s agents and production chronologically. The data and framework also aided in establishing connections between the field’s translation production and the overall translation and publishing production in KSA, thereby positioning the field within its wider socio-cultural context of cultural production in KSA.

Finally, integrating the data from the compiled bibliographical database with literature on the Saudi publishing field – from which the field’s agents originated – allowed for positioning the agents, production, and practices within the larger social field of impact. This facilitated the creation of links and connections to broader socio-cultural factors and events that influenced the emergence and development of the field. This integration also supported the definition of the field’s practices and production by considering the socio-historical characteristics not only of the Saudi publishing industry as the parent field, but also of the Saudi fields of power (political, religious, and economic), which have an influence on all fields of cultural production in KSA. This approach provided a distinctive method for the socio-historical contextualisation of the translation field under study within its encompassing fields.

Future research on other translation fields can pragmatically adopt this framework as a heuristic example for the socio-historical definition and mapping of translation fields. It can be adjusted for application to various translation fields across different temporal, geographical, and linguistic contexts, as well as for the accommodation of diverse social contexts and data-collection methods for non-literary translation fields or domain-specific sectors, such as audio-visual translation.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program. This research also received grant no. (101/2023) from the Arab Observatory for Translation (an affiliate of ALECSO), which is supported by the Literature, Publishing & Translation Commission in Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Abdullah Alqarni conceptualised the study, conducted the research, and wrote the manuscript. Bandar Altalidi and Yousef Sahari assisted with data verification and provided feedback on the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Aarts, P., & Nonneman, G. (2005). Introduction. In P. Aarts & G. Nonneman (Eds.), Saudi Arabia in the balance: Political economy, society, foreign affairs (pp. 1–7). New York University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Algofily, F. (2012). Maẓāhir al-taghayyur fī al-mujtamaʿ al-Suʿūdī: Al-maẓāhir al-māddiyya wa-al-thaqāfiyya [Manifestations of change in Saudi society: Physical and cultural manifestations]. Dar Al-Mujaddid.Suche in Google Scholar

Alkhamis, A. (2013). Socio-cultural perspectives on translation activities in Saudi Arabia: A Bourdieusean account. (PhD thesis). University of Manchester. https://bit.ly/38x1vjU.Suche in Google Scholar

Alkhamis, A. (2019). Mumārasāt al-muʾassasāt al-akādīmiyya lil-tarjama fī al-Mamlaka al-ʿArabiyya al-Suʿūdiyya: Al-ghāyāt al-fardiyya wa-al-muʾassasiyya [The translation practices of academic institutions in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Individual and institutional objectives]. In M. Alwadai (Ed.), Al-juhūd al-Suʿūdiyya fī al-tarjama min al-ʿArabiyya wa-ʾilayhā [The Saudi efforts in translation from and into Arabic] (pp. 121–145). King Abdullah Bin Abdulaziz Int’l Centre for The Arabic Language.Suche in Google Scholar

Alkhatib, M. (2007). Economic performance of the Arabic translation industry in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In Performance of the Arabic translation industry in selected Arab countries: Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Saudi-Arabia and Syria (pp. 101–137). Mamdouh Alkhatib. https://bit.ly/3RGssIy.Suche in Google Scholar

Alkheder, H. (2013). Self-Help in translation: A case study of The Secret and its Arabic translation. (PhD thesis). York University. https://bit.ly/3q0GAeE.Suche in Google Scholar

Alnasser, N. (1998). Tarjamat al-kutub ʾilā al-ʿArabīya fī al-Mamlaka al-ʿArabīya al-Suʿūdīya [Translation of books into Arabic in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia]. King Abdullaziz Public Library.Suche in Google Scholar

Alrrashid, M. (2000). Ḥarakat al-taʾlīf wa-al-nashr fī al-Mamlaka al-ʿArabīya al-Suʿūdīya [The authoring and publishing movement in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia]. Journal of King Fahad Library, 6(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/search.mandumah.com/Record/31435.Suche in Google Scholar

Alshehri, F. (2019). Al-Marsad al-Suʿūdī fī al-tarjama [Saudi observatory on translated publications]. In M. Alwadai (Ed.), Al-juhūd al-Suʿūdiyya fī al-tarjama min al-ʿArabiyya wa-ʾilayhā [The Saudi efforts in translation from and into Arabic] (pp. 147–180). King Abdullah Bin Abdulaziz Int’l Centre for The Arabic Language.Suche in Google Scholar

Alshehri, F. (2020). Al-Marsad al-Suʿūdī fī al-tarjama [Saudi observatory on translated publications]. King Saud University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Alshehri, F. (2022). Saudi Observatory on Translated Publications [Saudi Observatory on Translated Publications]. Saudi Observatory on Translated Publications. https://sotp-marsad.com/en.Suche in Google Scholar

Alsiary, H. (2016). Mapping the field of children’s literature translation in Saudi Arabia:translation flow in accordance with socio-cultural norms. (PhD thesis). University of Leeds. https://bit.ly/2LCYDJf.Suche in Google Scholar

Anker, R. (1999). Self-Help and popular religion in early American culture: An interpretive guide. Greenwood.10.5040/9798216012641Suche in Google Scholar

Asseri, A. (2000). Marāḥil al-taghayyurāt al-thaqāfiyya fī al-mujtamaʿ al-Suʿūdī: Dirāsa waṣfiyya [The stages of cultural changes in the Saudi society: A descriptive study]. Journal of the Faculty of Arts, Helwan University, 1(8), 203–243.Suche in Google Scholar

Bergsma, A. (2008). Do self-help books help? Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(3), 341–360. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10902-006-9041-2.10.1007/s10902-006-9041-2Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1983). The field of cultural production, or: The economic world reversed. Poetics, 12(4), 311–356. doi: 10.1016/0304-422X(83)90012-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1990a). In other words: Essays towards a reflexive sociology. Stanford University Press.10.1515/9781503621558Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1990b). The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature (R. Johnson, Ed.). Columbia University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field. Polity Press.10.1515/9781503615861Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1998a). On television. The New Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1998b). Practical reason: On the theory of action. Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (2005). The social structures of the economy (C. Turner, Trans.). Polity.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (2008). A conservative revolution in publishing. Translation Studies, 1(2), 123–153. doi: 10.1080/14781700802113465.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An Invitation to reflexive sociology. Polity Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Champion, D. (2010). The paradoxical kingdom: Saudi Arabia and the momentum of reform. Columbia University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Cherry, S. (2008). The ontology of a self-help book: A paradox of its own existence. Social Semiotics, 18(3), 337–348. doi: 10.1080/10350330802217113.Suche in Google Scholar

Cordesman, A. H. (2003a). Saudi Arabia enters the twenty-first century. The military and international security dimensions. Praeger.Suche in Google Scholar

Cordesman, A. H. (2003b). Saudi Arabia enters the twenty-first century: The political, foreign policy, economic, and Eenergy dimensions. Praeger.10.5040/9798216189343Suche in Google Scholar

Dolby, S. (2008). Self-Help books: Why Americans keep reading them. University of Illinois Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Effing, M. (2009). The origin and development of self-help literature in the United States: The concept of success and happiness, an overview. Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies, 31(2), 125–141. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41055368.Suche in Google Scholar

El-Khoury, S. (1988). Al-Tarjama wa-al-nahḍa al-ʿArabiyya al-muʿāṣira [Translation and the contemporary Arab renaissance]. The Literary Position: The Arab Writers Union, 202–203(17), 64–71. http://search.mandumah.com/Record/303782.Suche in Google Scholar

Gouanvic, J. M. (1997). Translation and the shape of things to come: The emergence of American science fiction in post-war France. The Translator, 3(2), 125–152. doi: 10.1080/13556509.1997.10798995.Suche in Google Scholar

Halbawi, K. (1987). Waqiʿ al-tarjama fi al-Mamlaka al-ʿArabiyya al-Suʿudiyya [Translation Reality in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia]. In Dirasat ʿan waqiʿ al-tarjama fi al-watan al-ʿArabi [Studies on the translation reality in the Arab World] (pp. 41–63). Arab League Educational, Cultural, and Scientific Organization.Suche in Google Scholar

Hanna, S. (2011). Flows of English-Arabic translation in Egypt in the areas of literature, literary/cultural and theatre studies: Two case studies of the genesis and development of the translation market in modern Egypt. Transeuropéennes, Paris & Anna Lindh Foundation, Alexandria, 1–112.Suche in Google Scholar

Hanna, S. (2016). Bourdieu in translation studies: The socio-cultural dynamics of Shakespeare translation in Egypt. Routledge.10.4324/9781315753591Suche in Google Scholar

Heilbron, J., & Sapiro, G. (2007). Outline for a sociology of translation: Current issues and future prospects. In M. Wolf & A. Fukari (Eds.), Constructing a sociology of translation (Vol. 74, pp. 93–107). John Benjamins Publishing. doi: 10.1075/btl.74.07hei.Suche in Google Scholar

Jenkins, R. (1992). Key sociologists: Pierre Bourdieu (P. Hamilton, Ed.). Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, W. B., Johnson, W. L., & Hillman, C. (1997). Toward guidelines for the development, evaluation, and utilization of Christian self-help materials. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 25(3), 341–353. doi: 10.1177/009164719702500303.Suche in Google Scholar

Kay, S. (1982). Social change in Modern Saudi Arabia. In T. Niblock (Ed.), State, society, and economy in Saudi Arabia (pp. 85–171). St. Martin’s Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Khalifa, A. (2017). The socio-cultural determinants of translating modern Arabic fiction into English: The (re)translations of Naguib Mahfouz’s ‘Awlād Hāratinā. (PhD thesis). University of Leeds. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/18329/.Suche in Google Scholar

McGee, M. (2005). Self-Help, Inc.: Makeover culture in American life. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195171242.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

McLachlan, K. (1986). Saudi Arabia: Political and social evolution. In I. R. Netton & M. ʻAbd al-Ḥayy M. Shaʻbān (Eds.), Arabia and the Gulf: From traditional society to modern states. Croom Helm.Suche in Google Scholar

Netton, I. R., & Shaʻbān, M. ʻAbd al-Ḥayy M. (Eds.). (1986). Arabia and the Gulf: From traditional society to modern states. Croom Helm.Suche in Google Scholar

Niblock, T. (2015). State, society and economy in Saudi Arabia. Routledge.10.4324/9781315727455Suche in Google Scholar

Pym, A. (1998). Method in translation history. Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Saati, Y. (1979). Ḥarakat al-taʾlīf wa-al-nashr fī al-Mamlaka al-ʿArabiyya al-Suʿūdiyya: 1390–1399 [Authoring and publishing movement in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia:1390_1399 AH]. Literary Club In Riyadh.Suche in Google Scholar

Santrock, J. W., Campbell, B. D., & Minnett, A. M. (1994). The authoritative guide to self-help books. Guilford Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Sapiro, G. (2008). Translation and the field of publishing: A commentary on Pierre Bourdieu’s “A conservative revolution in publishing”. Translation Studies, 1(2), 154–166. doi: 10.1080/14781700802113473.Suche in Google Scholar

Sapiro, G. (2010). Globalization and cultural diversity in the book market: The case of literary translations in the US and in France. Poetics, 38(4), 419–439. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2010.05.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Sapiro, G., & Bustamante, M. (2009). Translation as a measure of international consecration. Mapping the world distribution of Bourdieu’s books in translation. Sociologica, 3(2–3), 1–45. https://www.rivisteweb.it/doi/10.2383/31374.Suche in Google Scholar

Tashkandi, A. (1980). Ṣināʿat al-kitāb al-Suʿūdī al-muʿāṣir: Dirāsa taḥlīliyya [The contemporary Saudi book industry: An analytical study]. Economics and Administration Journal-King Abdulaziz University, 1(11), 145–165. http://search.mandumah.com/Record/47821.Suche in Google Scholar

Thompson, J. B. (2010). Merchants of culture: The publishing business in the twenty-first century. Polity.Suche in Google Scholar

Thomson, P. (2012). Field. In M. Grenfell (Ed.), Pierre Bourdieu: Key concepts. Acumen.Suche in Google Scholar

Toury, G. (1995). Descriptive translation studies and beyond. John Benjamins Publishing.10.1075/btl.4Suche in Google Scholar

Translated books in Arabic in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. (2008). King Fahad National Library.Suche in Google Scholar

Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). The structure and logic of Bourdieu’s sociology. In P. Bourdieu & L. J. D. Wacquant (Eds.), An invitation to reflexive sociology (pp. 1–59). Polity Press.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction