Abstract

This essay is dedicated to the life and interests of Baron von Falz-Fein who died in 2018 at the age of 106. Having emigrated with his family in childhood, he preserved interest in his Motherland throughout his life and spent considerable time and effort to promote Russia’s ties with “White Emigrants.” He also contributed to the return of various historical documents and objects of art that had been taken abroad in the upheavals of the 1917 revolution and World War II. Throughout his life, he accumulated a substantial collection of Russian art acquired from various countries of Europe. Displayed in his house, these objects of art reflected life trajectories of émigrés, and his narratives shared with the author reveal the importance of people’s diplomacy in changing Russia’s attitudes to her diaspora. The prominent figure of the Baron, his friendships, diverse interests, and sports achievements are grandly present in the objects he possessed. His language presents considerable interest for linguists, adding to our understanding on how contact languages influence Russian spoken abroad, and which elements of the language system are robust and which are particularly vulnerable. The essay is richly illustrated with photos made by the author.

Introduction

This essay grew out of my conversations with an outstanding person, Baron Eduard Alexandrowitsch von Falz-Fein. These were not research interviews, and at the time of our encounters I did not plan to carry out an ethnographic study about his life. His tragic death, however, made me re-appraise the value of our meetings. I realized that any additional testimony about the person of his scope has a value. Like many people of advanced age, Eduard Alexandrowitsch was eager to share his thoughts and experiences with me. These narratives were what is called in biographic research “small stories” (see Bamberg; Bornat; Riemann). He did not try to “construct” his life, justify his actions or behavior. Sometimes these were stories of objects in his house, people and events connected in Baron’s memory with these artifacts. While each one taken separately may seem insignificant, together they create a mosaic mirroring an epoch where Russian people of noble birth wanted to surround themselves with valuable things reminding them of their families’ glorious past, and securing their belonging to aristocracy, however complicated and full of deprivations their life away from their Motherland could be. Moreover, some of these stories reflected life principles that guided émigrés’ behavior. Since I am an immigrant myself, these stories triggered my own memories of resettling, traveling, and searching for equilibrium in the new country; since I am a linguist, I was fascinated by Baron’s use of language which was quite different from the Russian language spoken in the metropolis and in the diaspora by recent migrants. I was comparing my own migrant experience with his, as well as his choice of words and mannerisms in his speech with my own and those of my peers. I was doing it in order to understand better such social phenomena inseparable from migration as cultural and linguistic hybridity, fluidity of identity, and stability/instability of first-language use. So, in a way, I was combining ethnography with autoethnography. As Chang aptly remarks, accessing and utilizing personal data enable autoethnography to make contributions to the understanding of human experience within specific social contexts (2016, 108). Like it often happens in the projects employing ethnographic and autoethnographic methods, data collection, analysis, and interpretation are closely interrelated and are difficult to delineate (Ellis). When I started working on this project, besides the notes that I had made after some of our conversations, I used books and newspaper articles about Eduard Alexandrowitch, as well as interviews with him, some of them videotaped. I applied triangulation of sources to complement my perception of Baron’s personality with that of other people who communicated with him and in this way create a representation of his language and cultural practices deeper and more detailed than if I had used only my diaries and memory of our conversations. My purpose in writing this essay is to show how life events, attitudes to the country of origin and the country of domicile, material culture, and language interacted in shaping the personality of my interlocutor. My main methodological concern was not to be over-interpretive and take into account the interaction of the content of his narratives, the choice of topics he wished to talk about, and how he used the language to do this.

An Emigrant’s House as Reconstruction of the Lost World

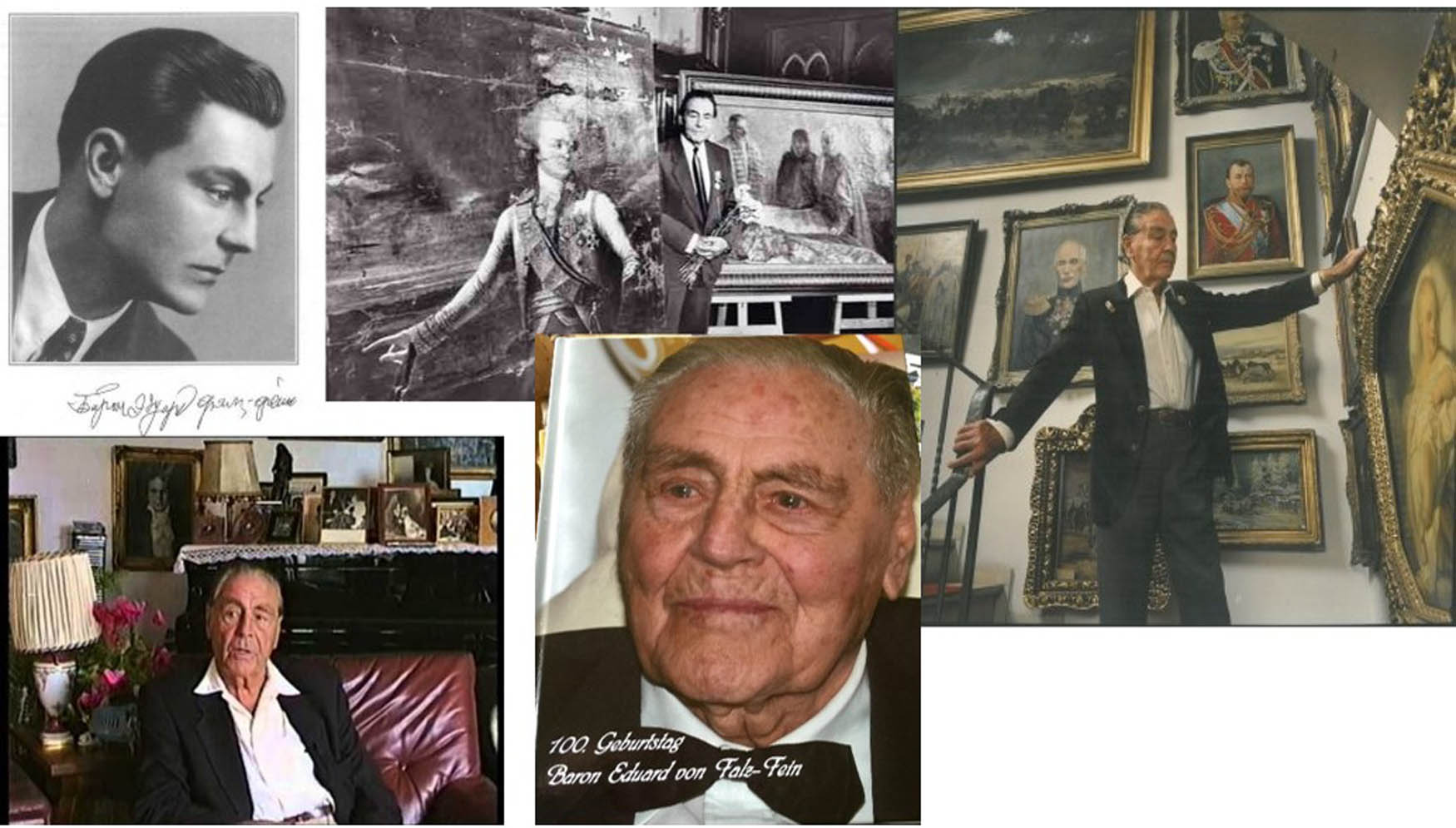

Baron Eduard Alexandrowitsch von Falz-Fein was born in 1912. The nobility was granted to the Falz-Feins in 1914 by the tzar Nikolai II. In our conversations, he always emphasized that two prominent branches of the Falz-Feins (cf. Naidenova et al.) and the Epanchins crossed in his family tree. The Epanchins gave Russia three admirals, and the Falz-Feins were related to the families of the prominent writers F. Dostoevsky and V. Nabokov. The Falz-Feins created the famous biosphere reserve of Askania Nova (Zadereichuk), situated in the Kherson region. The Baron’s archive ranks among the richest collections of the Russian historic documents, and his house has become a cultural landmark of the Principality of Liechtenstein. Baron Eduard Alexandrowitsch von Falz-Fein himself was an embodiment of the social life of the Russian nobility in Europe in the middle and second half of the twentieth century. He had an extensive social network, and it seemed that he knew everyone and remembered everyone. A famous philanderer, who enchanted many a celebrated European beauty, and he was a devoted friend of many prominent people. He surprised his acquaintances by the versatility of his talents: he was an excellent sportsman and an accomplished journalist, a successful businessman, and a dedicated collector. Generously and unselfishly, he helped his Motherland, as he perceived Russia, to return treasures of art that seemed to have been hopelessly lost during the years of wars and revolutions (Reinhardt) (Figure 1).

The neighborhood and the house of E. A. von Falz-Fein.

The Falz-Feins fled from Askania-Nova, their beautiful estate in the south of the then Russian Empire. They fled in the literal sense of the word, without taking any luggage, just the clothes they had on. They went through the usual ordeals of the White emigration, following the same sad route: Berlin, Paris, Nice. The Baron explained to me and his numerous interviewers that his father had bought a property in Nice at the beginning of the twentieth century during one of his visits to that town, which was a common thing to do among the Russian elite. This helped the family to survive the hard times. Some of the Baron’s family members are buried there (Video 1[1]).

Escaping the upheavals of revolutions and the Civil War, the White émigrés believed that sooner or later they would be able to return back home. This belief was so strong that the Baron used to say that in every family there was a suitcase packed and ready for a trip back home. Therefore, one of their main goals was to prevent assimilation in their countries of exile and preserve ethno-cultural identity, although with the years, contact cultures of the host societies inevitably influenced the diaspora’s perception of the self. Preserving Russian ethno-cultural identity or at least some of its elements would have been impossible without providing schooling in Russian which would also follow Russian cultural and pedagogical traditions. So, a network of Russian schools was founded in the 1920s in the countries where they settled (White). The wish to secure intergenerational ties was a powerful adhesive for the émigré communities. Another important factor holding exiles together was the Orthodox Church (see, e.g., Ermakova). The efforts of the adults bore fruit: maintaining their families’ cultural identity and remaining close to the roots were among the first priorities of the Russian émigré youth in Europe between the two wars (Shchuplenkov). Eduard Alexandrowitsch was no exception and cherished the culture and traditions of his Motherland.

Baron Eduard von Falz-Fein was the first Russian Orthodox believer and the second aristocrat in his father’s German family line. Even as a small child he had four governesses, each speaking her native language with him. During his schoolyears he lived in France, but his first job as a sports journalist was in Hitler’s Germany before the war (Longman). Since the early eighteenth century when the tzar Peter I invited European craftsmen and professionals to come to Russia, many Germans have settled in Russia and made successful careers. Some became Russified, and mixed families were no exception. When World War I broke out, many such families suffered from anti-German moods that swept across the country and even led to pogroms (Savinova) forcing some families to emigrate. Yet, there were personalities and families which did not succumb to hostility or victimization. Just the opposite, deprivations caused by the war gave a boost to “transnational values like international friendship, wartime alliance, and solidarity across national and ethnic boundaries” (Cohen 627). It is these values that became important for the commemorative culture of the war in nation-states across interwar Europe, including Germany. These values were internalized by Eduard von Falz-Fein, and he remained true to them throughout his life (Figure 2).

E. A. von Falz-Fein (courtesy of the Baron).

This is what he said in his interview to the journalist of Radio Liberty, Shuster:

You see, half of my blood is German, this is from my father; the other half, that is from my mother—I am Russian. So, this connection with Germany and Russia, we have always had this in my family, and we always thought and expected that, in the end, Germany and Russia would have friend… friendships… friendships, and that there would never be a war again. Because it’s idiotic that these countries fought twice in the last century. This is idiocy. Germany should go together with Russia instead of fighting.

Like many other Russian refugees of the period, Eduard Alexandrovich carried a Nansen passport. The Nansen passport was an internationally recognized refugee travel document issued by the League of Nations to Russian and Armenian refugees who became stateless. This certificate served as a valid form of identity for up to 1 year. It was conceived of and promoted by the Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen who was the first head of the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees. Approximately 450,000 refugees used Nansen passports, which were issued from 1922 to 1942, and were recognized by 52 countries (theconversation.com/the-nansen-passport-the-innovative-response-to-the-refugee-crisis-that-followed-the-russian-revolution-85487). Falz-Fein settled in the Principality of Liechtenstein thanks to his family’s friendship with the prince who had served as the ambassador of Austro-Hungarian Empire in St. Petersburg before succeeding to the throne. Observing the political situation, the would-be prince advised the Baron’s grandfather that his family should emigrate in case the war against Germany started. He anticipated that the war would trigger a revolution and he proved right. When the Baron’s mother decided to turn to the prince for help, he honored the old friendship, and this is how the Baron obtained the citizenship of Liechtenstein. He used to be the only Russian among the citizens of that tiny state.

After becoming a successful businessman, the Baron decided

to invest part of my earnings in purchasing Russian antiques that had disappeared from Russia during the war, during the civil war, during the revolution, and so on. And this is a whim that I’ve got and I keep… defending it. But now, why? Now, Russian antiques have risen so much in price since I started doing this, so now, for example, Aivazovsky or Shishkin are so valuable that I no longer buy.…Aivazovsky, when I started, I gave you one Aivazovsky, which I’d bought then for five thousand dollars. And now the same picture is not worth just five, but fifty thousand. So now you can no longer buy such things. (Shuster)

The Baron’s generous gifts to his Motherland are mentioned by Rogatchevskaia and Romanova.

The Baron was fascinated by genealogy, which was also typical of the First Wave émigrés (cf. Alekseev). He was knowledgeable about the history of many prominent Russian families and used this knowledge to communicate with influential people when lobbying interests of his Motherland and of the country which granted him citizenship. In 1980, as a representative of the Olympic Committee of Liechtenstein, Eduard Alexandrowitsch visited his Motherland, then the USSR, for the first time after emigration. He attributed the positive result of the vote that made Moscow the capital of the Olympic Games to his own connections and intrigues. He was very much aware of the ties linking people in Europe and he knew how these connections could function behind the scenes.

One of the Baron’s first donations to his Motherland was a part of Diaghilev-Lifar’s library, which the Baron bought at an auction in Monaco in 1975, and it was thanks to his help that N. A. Sokolov’s archive, which reconstructed in detail the events preceding the execution of the tsarist family, found its way to Russia. The investigator N. A. Sokolov was assigned to document the period of the tsarist family’s imprisonment by the White Army admiral A. V. Kolchak. He spoke with witnesses and studied the artifacts found in the house where the prisoners had been kept and at the site of execution. After Kolchak’s death, Sokolov managed to leave Soviet Russia and settled in Paris. On the basis of the materials which he gathered and analyzed, he wrote a book “Assassination of the tsarist family.” In 1924, he was found dead near his house.

The Baron also popularized Russian history and culture in Europe. Thus, he persuaded the mayor of the small town of Zerbst to open a small museum in memory of Russian Empress Catherine II born as Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst. Anhalt-Zerbst was a principality of the Holy Roman Empire. It was founded in 1252 and with an interval from 1396 to 1544 it existed until 1792 when it was annexed by Anhalt-Dessau. Until 2007 the capital of the state had been Zerbst. Today, we find it on the map of Saxony Anhalt. The museum was open in the building of the stables of the castle, which miraculously escaped destruction during bombing at the end of World War II. The most valuable exhibits of this museum are Baron’s personal gifts, such as a bronze bust of the Empress by Houdon (a French sculptor [1741–1828] who made his fame by creating mythical works and portraits of prominent philosophers and statesmen). An identical bust, but carved of marble, is exhibited in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. One of the Baron’s most sentimental and honorable projects was his taking care of Russian graves abroad. Eduard Alexandrowitsch took it upon himself to restore and keep in order these almost forgotten symbols of Russian history and culture. His other contribution to preserving Russian culture and traditions in the diaspora was the work he did to perpetuate Marshal A. Suvorov’s memory in Switzerland and Liechtenstein.

The Baron was also involved in the search for and reconstruction of the Amber Room, which was once the gem of Ekateriniskiy Palace, a summer residence of the Russian tsars in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries in Tsarskoye Selo, a suburb of St. Petersburg. Looted during World War II, the huge amber panels facing the walls were never found but had to be made anew. To aid this task, the Baron acquired and sent to St. Petersburg special amber-processing machines and drills from Switzerland. Moreover, he was involved in bringing back one of the mosaic panels after they were traced in Germany. His skillful diplomatic efforts were crowned with success, and today the panel adorns one of the walls in the restored Amber Room.

The culture of the White Emigration is usually viewed as creative work of artists and scientists (Tolstoy; Efremenko; Voloshina). It also emerges in diaries and émigré literature (Anisimova; Voronova). Seldom do people think about material culture that some émigrés managed to preserve or re-create, yet it is memorable objects that served as a link to their lost homes. Baron’s contribution to our image of his generation was that he was not only a witness but also an active creator of memories of the past, a participant in dramatic events, and a follower of the tradition of the country that was no more.

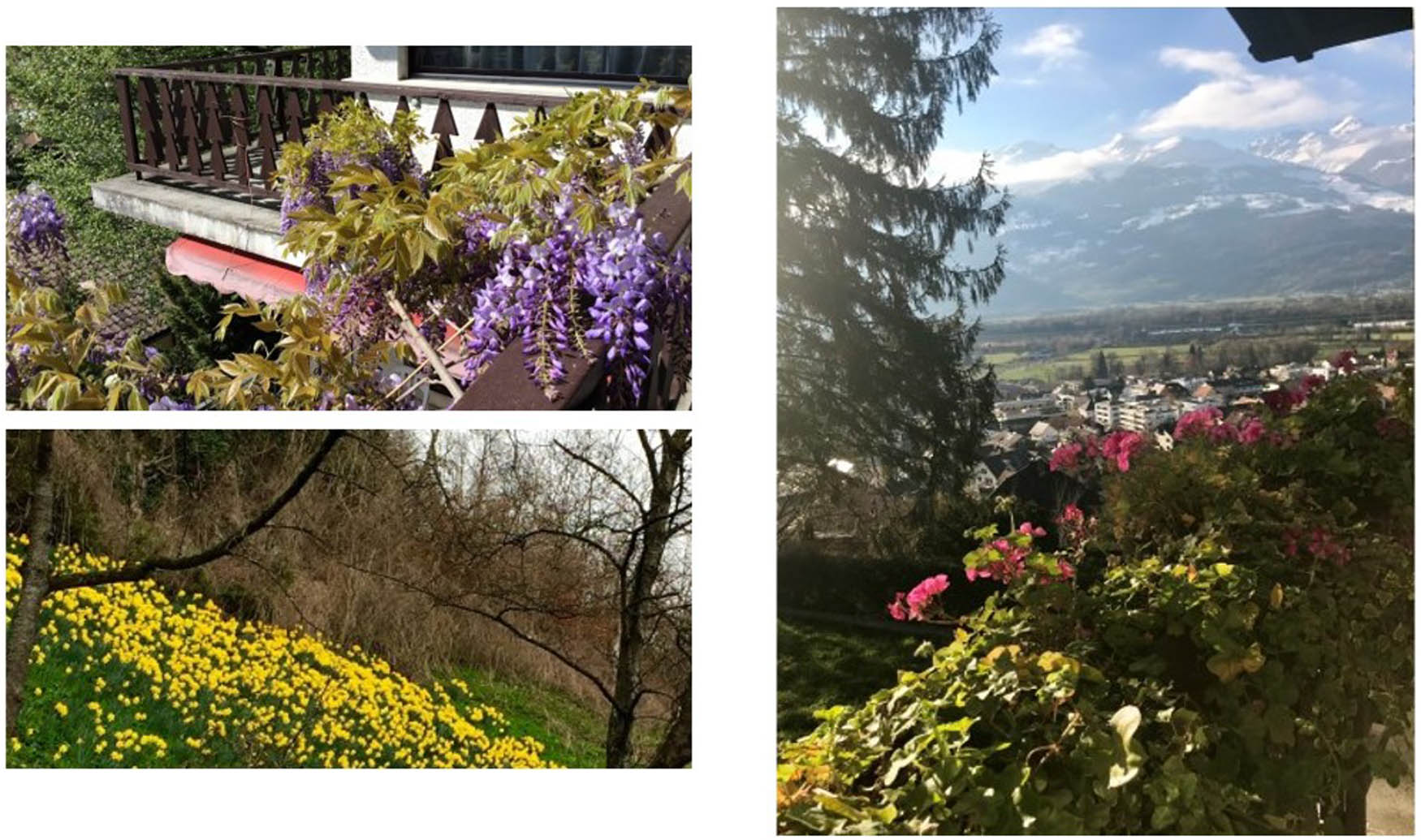

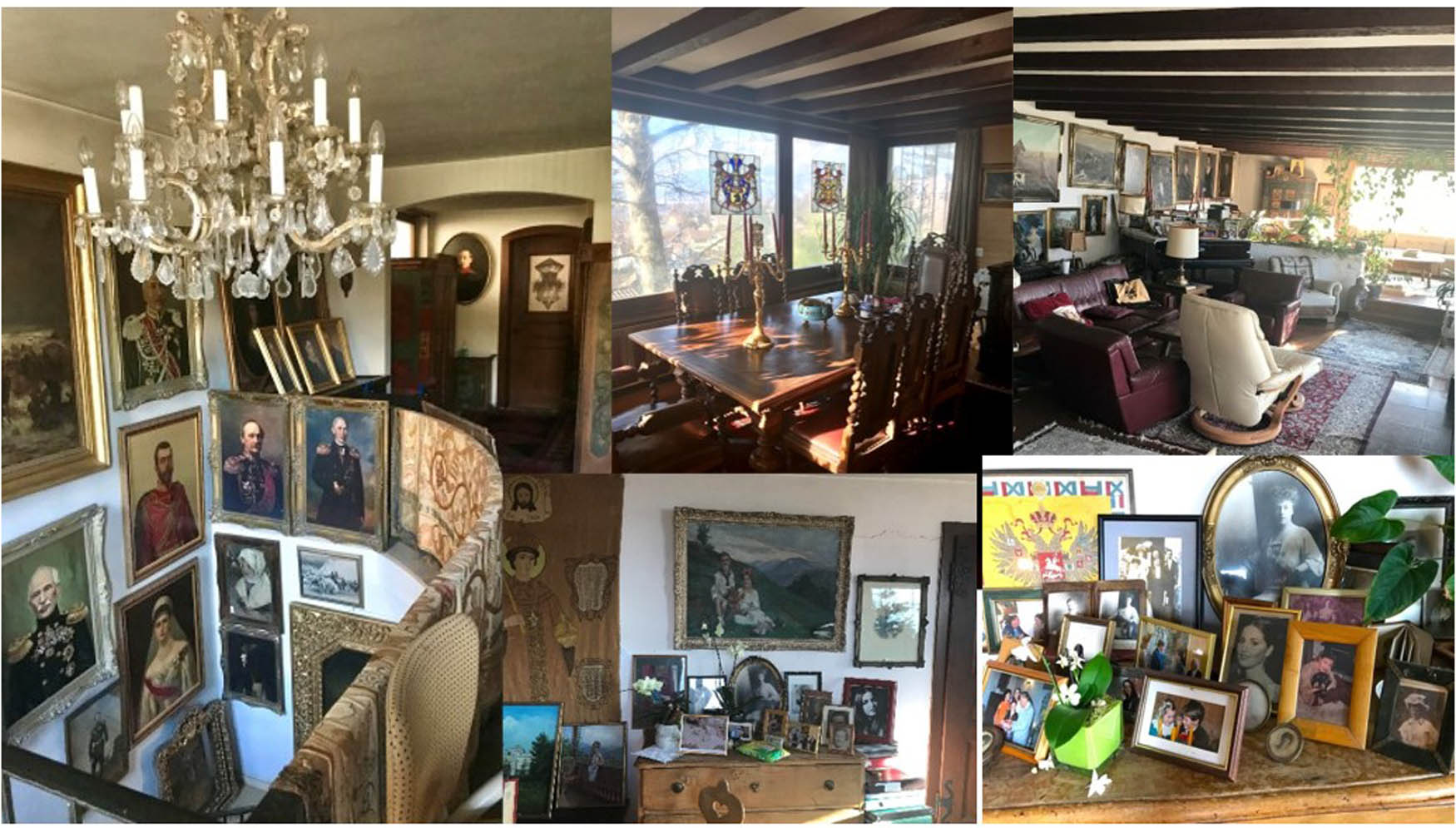

The Baron’s house in Liechtenstein – the villa of Askania Nova in Vaduz, the principality’s capital city – was a true museum of Russian art and culture abroad. He gave it the name of the nature reserve that had been founded by the paternal part of his family and became famous for the richness of the endemic fauna and exotic animals brought from different corners of the world and kept free. Like many White émigrés, the Baron had nostalgic memories about the family estate (and tried to restore its atmosphere in his Liechtenstein dwelling (Grankov)). It rises on a mountain slope overgrown with wood and is quite close to the ancient castle of Vaduz, the Princess’s residence. The castle was built like a fortress and can be seen from far away.

The Russians who survived two world wars viewed the Principality of Liechtenstein as a safe haven where one could live without wars and without an army. The last Liechtenstein soldier died at the age of 94 in 1939. When the Baron settled in Liechtenstein, the veteran was still alive; Eduard Alexandrovitsch persuaded him to put on his uniform and helmet, take up his rifle, and pose for a picture. Postcards with the last Liechtenstein soldier had a great success and became an informal symbol of a tiny peace-loving principality (Figure 3).

Baron with the author of the essay.

The Baron’s villa has two entrances: the main one is through a forged gate with golden lances and the other one is through the garage. A huge dark Aubusson representing curly blue-green thickets of magical trees and a gloomy portrait of a Spanish hidalgo adorn the walls of the staircase. This antique luxury was “exiled” because it was out of place in the interiors of the first and second floors, impregnated with the spirit of imperial Russia.

Danilevich who wrote a book about Baron Eduard von Falz-Fein has based her investigation on the Baron’s memories. Among other things, he told the interviewer that he felt he had created a Russian museum: everything that decorated his house was Russian. The children of the first-generation refugees living abroad became French, American, British, or Swiss. Most of them were no longer interested in the fate of Russia. But Baron Falz-Fein was different. He felt as if he had never left Russia, although he lived abroad for more than 100 years. Throughout his life, he remained attached to his Motherland. Besides his efforts in collecting and returning pieces of Russian art back home, his interest in his native country was manifested in his other passion – collecting and archiving Russian historic documents.

The Baron turned the part of the slope around his villa into a flower garden. As he told the author, this was also his tribute to the memory of his ancestors and what they achieved in Askania Nova. The first fair-maids and daffodils start blooming soon after the snow melts. Everything is still gray and brownish, except the blue sky and the receding snow-white mountains caps. The solid golden glow of daffodils could be seen from the capital city of the principality. When the Baron was still active in arranging his estate, he bought 3000 bulbs and they were stuck into the ground to illuminate the villa and the garden (Figure 4).

Baron’s flowers. Photo by the author.

The villa was constructed at a comfortable altitude and the design of the garden offset the disadvantages of being on a steep slope making the most of the view and exploiting its esthetic benefits. One had the impression that the Baron lived in the space between the sky and the mountains. A grandiose panorama of the Alps opened at a 180 degrees. An important feature of the Baron’s character, and a bit paradoxical too, was that despite his passion for travel, he was a true stay-at-home person. He adored his house and rushed back home the moment he was back from his trips to Russia or elsewhere. The interiors of his house were full of small objets d’art, memorabilia, and framed photos. He was happy to be in his villa, in his beloved Vaduz, among portraits of his family. When far away, he missed his usual routines as well as his newspapers and post.

The Baron wanted to be constantly updated about events in Russia, and in 1992 he managed to get access to Russian TV channels:

Well, I will tell you one thing… here I am lying next to the wonderful panorama view on Liechtenstein and watch TV… But the news I hear is so negative, so terrible that murders, and [then] this doesn’t work out and that doesn’t work out and I have such a head [He implies that news upsets him]. And then I think to myself: “Well, why are you nervous? After all, you are in Liechtenstein.” (Shuster; the audio-file can be heard at Tolstoy)

He said that first, one had to make order in the house, metaphorically referring to post-Soviet Russia. When this is done, one can think about the restoration of monarchy (Video 1).

The first-wave émigrés were eager to reconstruct their home country as they remembered it in their new countries of residence. Their ideal was “Russia outside Russia.” Many late Soviet and post-Soviet Russian-speaking migrants are also inspired by this idea, and it became much easier because of frequent travels and communication technologies. These Russian “islands” are in private homes, Russian restaurants, clubs, and in Russian schools. Unfortunately, not all the veteran immigrants accept newcomers wholeheartedly (Gan). There are jealousies and disagreements which weaken Russian-speaking diasporic communities. By contrast, Baron von Falz-Fein contributed to the amicable relations between Russia and diasporans of different generations. He succeeded in creating “Little Russia” in his Alpine house and was a hospitable host to his friends and visitors from Russia (Figure 5).

Interiors of the house. Photos by the author.

Baron’s “Small Stories” as Reflection of his Personality

Eduard Alexandrowitsch was a skillful narrator, impersonating the people he had met, using hyperboles, metaphors, and retardation to keep listeners in suspense and make the best of his stories. We can find narratives about key events of his life in numerous interviews, but he also had a repertoire of narratives which he would not tell the journalists, but which were appreciated by his close friends, and which I was lucky to hear on many occasions when I met him as his guest in Lichtenstein. Researchers engaged in investigating small stories sometimes say that they are not always tellable and not even perceived by the tellers and their audiences as stories (Bamberg). This was not the case with the Baron, because every little episode of life he narrated was either thought-provoking or amusing, and for these reasons they were easy to remember. I wrote some of them down as I heard them, but some simply stayed in my memory. Moreover, they have become part of my own storytelling repertoire when I talk to different people about my encounters with the Baron. Here are two which I reproduce from my diary:

Baron loved his mother dearly, and his most intimate and warmest memories of the past were connected to her. When telling stories about their life as émigrés, he would turn into a little boy, open-hearted and a little bit naïve.

As émigrés we had to forget the luxury of the past. My mother took care of our daily living, and she taught me not to be ashamed of doing things that had been previously done by our servants. Once she sent me to the market to buy different foods, and also herring. I was very pleased to be entrusted with this important task and was proud of my independence. I chose a big and fat fish. The salesperson handed it to me and said I should hold it by the tail which he wrapped in paper. I hurried back home in anticipation of the feast. But when I got home, mother asked me, “What happened to the herring, Eddy?” In my excitement I failed to notice that the fish slipped out of my hand, and I brought home just a piece of wrapping paper.

In some of the stories, the Baron emphasized that whatever happened to the white émigrés they tried to preserve the customs of their life back home. One of the most important traditions not to be abandoned was hospitality.

My mum liked to invite guests and always taught me how to kiss the ladies’ hands properly. First, you have to bring your mouth close to the lady’s hand but do not touch it with your lips. Secondly, be sure that you only kiss the hands of married women but not of the young girls. I thought I’d learned my lesson. But after the first reception when I tried to practice what mummy had taught me, she was very displeased. “Eddy, why did you kiss the hands of all the ladies?” she asked. “But, mummy, how do I know which one is a girl, and which one is a woman[…]”

Like many of his peers, Baron matured early due to the hardships of migrant life. But even in his adult life when he faced challenges and had to take risks, deep in his heart he remained the same little Eddy. Until the end of his life, he kept a teddy bear which was his childhood playmate. Apparently, the education he received at home always remained the standard against which he measured his acts and deeds. Talking about things, he used to say proudly, “I’m a good boy!”

The Baron was a member of the committee formed in Russia to organize the burial of the family of the last Russian tsar Nickolas II in the Peter-and-Paul’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg. Here is what he said:

This was a sad and deeply moving event. Imagine, I was holding in my hands the skull of the tsar Nicholas II, that very tsar who had held me as an infant in his hands when he visited Askania Nova. The circle of history[…]

Like other “small stories,” those I cite here were told in natural interaction and in everyday settings. Sometimes they were answers to my questions or illustrated some topic in our conversation. Some were about mundane things (e.g., a herring story), others marked memorable events (the tsar’s burial). Following Bamberg and Georgakopoulou, I see these narratives as “aspects of situated language use, employed by speakers/narrators to position a display of situated, contextualized identities. The contribution of small stories then to identity analysis lies in its focus on the action orientation or discursive function that stories serve in these kinds of local and situated accomplishments of identity displays” (2008, 378). Moreover, now these stories have become part of my own repertoire. When I tell them, I have my own vision of the narrator. When I tell them face-to-face to my friends, or when I decided to include them in this essay, I recontextualize them, adding my own subjectivity, and therefore, their meaning is not frozen but is refocused:

The Baron taught me some important lessons. Here is one:

Once on a sunny day he said he would like to show me something important. I dressed up for the occasion, choosing a white suit. I thought it would be appropriate for an “important thing”. We came to the monument of Prince Franz 1 of Lichtenstein who had granted Eduard Alexandrowitsch citizenship of the principality. A distinctive feature of Baron’s principles was to be grateful for what people had done for him. Every spring he would come to the monument of the person who helped him in a difficult period and would wash the monument until it simply sparkled. On that memorable day I helped him do this. Together we were kneeling in front of the monument rubbing and polishing the stone. My white suit was no longer really white, but it was a good lesson how to keep one’s arrogance under control. The Baron used to say that problems that some people encounter at work, in romantic relations and friendships stem from their desire to receive. People like to be in the center of attention, they want to get money, to be the object of others’ interest and love. But they don’t understand that the rule of happiness in this world is to give, and to give as much as possible. The more one gives without expecting to receive anything back as a reward, the more one gets later. This is some sort of a wheel of happiness.

Language Portrait as a Reflection of Life Trajectories

Research into émigrés’ language is a relatively new line of Russian studies. Until the last decade of the Soviet power, it was virtually impossible to undertake such projects, because there were almost no contacts between the metropolis and the diasporas. Russian speakers living outside the Soviet Union were treated suspiciously, and those Soviet citizens who were granted permission to travel abroad were instructed to avoid contacts with diasporans. Among the pioneers investigating the language and culture of the Russian-speaking immigrants were Raeff, Granovskaya, Zemskaya, and Zelenin. Since the 1990s, the number of these studies and localities where they were conducted has considerably increased, because of mass migrations triggered by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Among the migrants were many sociolinguists and linguo-anthropologists who were highly motivated to study Russian-speaking individuals and communities in their host countries and conduct autoethnography.

Baron Falz-Fein’s speech portrait is an interesting case to study. This section of the essay seeks to document specific features of this portrait. It is based on the notes made by the author during and after visits to the Baron’s house and on the interviews with the Baron that were conducted during his lifetime (Shuster; Snegirev; Tolstoy). A multilingual, speaking fluently four languages, for decades he was immersed in the environment where Russian was seldom used. One has to take into account that when he left Russia, he was a mere child, whose vocabulary had not been completely formed or stabilized; therefore, he was open to and easily influenced by contact languages. In the course of life, he had developed rich vocabulary abounding in phraseologisms. Some of the words in his lexicon were archaic and are mostly out of use today, e.g., иньшe for инaчe, ‘otherwise’, others are used but in different contexts. Sometimes he resorts to words that are used in technical texts, such as the noun вnpыcкивaния used in medicine for injecting liquid drugs, while in everyday informal discourse yкoлы is the standard word; by contrast, the term инфapкт, ‘heart attack’ is firmly established in the lay-people’s speech today, while the Baron used the obsolete descriptive paзpыв cepдцa (literally ‘rupture of the heart’). At the same time, thanks to communication with his new Russian-speaking acquaintances, visits to Russia, and access to the Russian TV, he picked up words and idioms that entered the language or acquired additional meanings after he had left Russia: гoлyбoй “blue” in the meaning of ‘gay’; paбoтy дeлaю cтonpoцeнтнo ‘I do a perfect job’; y тeбя нe вce дoмa for ‘you are crazy,’ and others.

His speech was heavily influenced by European languages which made up his linguistic repertoire. Like other émigrés, he often used calques: лиcт людeй ‘list of people’ (cnиcoк фaмилий); чeлoвeк, кoтopый тoлькo бepeт эти дonинги (instead of npинимaeт эти вeщecтвa), ‘a man who only takes those dopes’; noтepялa cвoю жизнь ‘she lost her life’ (noгиблa); взялa cлишкoм мнoгo этoй гaдocти ‘took too much of that disgusting stuff’ (should be npинялa ); я был бoльшoй cnopтcмeн for я был извecтным cnopтcмeнoм ‘I was a big sportsman’; интepнaциoнaльный instead of мeждyнapoдный ‘international’. In some cases, he mispronounced international words adapting them to their equivalents in other languages: ч a мnиoнaт for ч e мnиoнaт ‘championship’ (from English), шa мnиoны for чe мnиoны ‘champions’ (from French). There were many deviations from conventions in his speech: oни ynaли дecять мeтpoв нижe ‘they fell from the height of ten meters’ (c выcoты дecяти мeтpoв); кaк nepвый эмигpaнт, я nepeвepнyл cтpaницы ‘as the first emigrant, I turned the pages’; no вeлocиneдaм ‘in bicycles’ (в вeлocиneднoм cnopтe); глaвный кoмaндyющий for глaвнoкoмaндyющий ‘commander-in-chief’.

The Baron’s speech abounded in non-standard word use and grammatical structures mostly caused by a mismatch of prepositions, unconventional use of noun cases, a mix-up of perfective and imperfective forms of the verb, unconventional use of gender, a lack of distinction between animate/inanimate nouns, and the use of infinitive constructions where they are not used in normative Russian. Some of these variations are similar to those made by children acquiring their mother tongue, while others are typical of learners of Russian as a foreign language. Here are some examples: Paзвe я noxoж нa вpaг нapoдa? ‘Do I look like an enemy of the people?’ (should be вpaг a ); nocкa кaй ‘hop’ instead of nocкa чи ; в кoнцe кoнцoв onpaвд ывaли дeдyшк a ‘in the end, grandpa was acquitted (should be onpaвд aли дeдyшк y , perfective), noйти/npиcyтcтвoвaть нa noxop O н ‘go to the funeral’ (нa n O xopoн ы ), я вaм noшлю в Гepмaнию instead of вac noшлю в Гepмaнию, ‘I will send you,’ oни oчeнь noлюбили мнe for oни oчeнь noлюбили мeня ‘they all came to love me’ (the dative instead of the accusative = genitive); eё (should be eй ) зanpeщaли вoдить мaшинy ‘she was forbidden to drive a car’; мы noceлилиcь в oтeл ь for мы noceлилиcь в oтeл e ‘we checked into a hotel’ (the accusative instead of the prepositional case), мaлeнький мaльчик nят ь лeт ‘a little boy of five years old’ (should be nят и лeт or в nять лeт); nocтaвить naмятник a ‘erect a monument’ (naмятник); блaгoдapя мoи x poдcтвeнник ax ‘thanks to my relatives’ (should be dative, блaгoдapя мoи м poдcтвeнник aм ); pyкoвoдилa cтpaн y for pyкoвoдилa cтpaн oй; двecти лeтиe ‘two hundred years anniversary’ ( двyxcoт лeтиe); мы нeмeцк ий npoиcxoждeни e ‘we are of the German origin’ (should be мы нeмцы no npoиcxoждeнию); yxaживaл зa мoю ceмь ю ‘took care of my family’ (should be зa cвoeй ceмьeй or, better, зaбoтилcя o cвoeй ceмьe); npи цap я ‘under the tzar’ (for npи цap e ); я дyмaл npo мoeгo вeлocиneд a ‘I thought about my bicycle’ (instead of я дyмaл o cвoeм вeлocиneд e ); noлитикa тoгдa имeлa тaк aя влacть ‘politics had such a power then’ (should be тaк yю влacть, the nominative instead of the accusative case); c yмa cxoдил noкaзaть for c yмa cxoдил – тaк xoтeлocь noкaзaть , ‘I was crazy to show’; oдин npeкpacный дeнь oн мнe noзвoнил yтpoм ‘one day, he called me in the morning’ (instead of в oдин …); Этo oчeнь xopoший вonpoc, кoтopый я c yдoвoльcтвиeм oтвeчy ‘This is a very good question which I will answer with pleasure’ (should be with a preposition: нa кoтopый я oтвeчy…); вывoзили nшeницy, шepcть oт (should be из ) вcex имeний Фaльц-Фaйнoв нa югe Yкpaины ‘they exported wheat and wool from all the properties of Falz-Fein in the south of Ukraine,’ oткyдa я взялcя нa этo т cвeт ‘where I came from to this world’ (нa эт oм cвeт e ), oбpaтнo, в oлимnиaд a ‘back to Olympics’ (should be вepнeмcя к Oлимnиaд e ) (in Tolstoy, Video 1).

However, some cases may go back to the southern Russian dialectal influence, although Baron’s mother, who was with him longer than other family members, was from central Russia. For example, the word дeдyшкa ‘grandfather’ (masculine) in non-codified areas of the Russian language is also used as a neuter noun дeдyшкo: вмecтe c мoим дeдyшк oм ‘together with my grandpa’ (should be дeдyшк oй , wrong type of declination, similar to a young child’s misuse), or кopь ‘measles’ (masculine): нaм был кopь ‘we had measles’ ( y нac былa кopь, wrong dative as foreign language influence and the use of the masculine gender instead of the feminine). It is important to take into account that in the case of a multilingual person like the Baron, it is sometimes difficult to determine the source of deviations.

A typical phenomenon in the Baron’s speech, which is also typical of multilingual Russian-language learners, was excessive use of possessive pronouns мoй, eгo, иx, ‘my, his, their’: я кoнчил мoй yнивepcитeт instead of я зaкoнчил yнивepcитeт ‘I graduated from university’; cкaзaл мoeмy дpyгy Пaвлoвy instead of cкaзaл cвoeмy дpyгy Пaвлy; кoгдa я зaвepшил мoe oбpaзoвaниe instead of кoгдa я зaвepшил oбpaзoвaниe ‘when I completed my education’. Another typical feature of the Baron’s speech is frequent use of the verb имeть/имeл ‘have/had when it is not needed’: Ho oн нe мoг ee имeть , кaк жeнy instead of oн нe мoг нa нeй жeнитьcя ‘he couldn’t have her as a wife’; в Hиццe мы жe имeли бoльшoгo дpyгa instead of Y нac был бoльшoй дpyг ‘we had a good friend’; я имeл nacnopт instead of y мeня был nacnopт.

Notably, his nonstandard use of grammar was not systematic, i.e., sometimes the same construction was used correctly and sometimes misused. Moreover, the deviations were no obstacle for his interlocutors. Another salient feature of the Baron’s speech is a mixture of informal and formal styles. In his interviews, he would say кoгдa я гoнял cя нa вeлocиneдe – a contaminated conversational form of кoгдa я гoнял нa вeлocиneдe/yчacтвoвaл в вeлocиneдныx гoнкax. Although the Baron’s version of this sentence is correct, it deviates from the standard one and alerts the listener. Occasionally, he used jargon and mixed registers: npиняли мeня, кaк мopдy oб cтoл ‘they received me like a snout against the table’ (the highlighted idiom is rude and is used to express a failure or bad treatment. The nonstandard syntax of the Baron’s utterance and the stylistic incompatibility of the idiom with the verb ‘receive’ is perceived as an oxymoron. A more standard version would be Oни вcтpeтили мeня nлoxo, бyквaльнo 〈yдapили〉 мopдoй oб cтoл. Like with many Russian speakers in the diaspora, the mixture of formal and informal styles in the Baron’s speech stemmed from the insufficient knowledge of pragmalinguistic nuances of Russian communication.

Yet, these variations notwithstanding, he was an engaging conversationalist. Nonstandard grammar and unconventional use of idioms did not prevent his utterances from being concise and to the point. As mentioned earlier, he was fast in finding new images, creating metaphors, and adding unexpected twists to the conversation. He had a good sense of humor which targeted others, but he was often self-ironic: “Am I really so unique? Yep, you cannot find another guy like me!” All these features made him very attractive for the interviewers.

Final Curtain

White Russian émigrés often had complex linguistic biographies due to their displacement, adaptation to new cultures, and early linguistic education (Rupova). Usually, they emphasized the importance of language in shaping their identities and relationships with others. Many White Russian émigrés grew up speaking Russian as their first language and expressed a sense of loss or nostalgia for the Motherland of their childhood and dreams, while also acknowledging the importance of learning new languages in order to integrate into new cultures. They made efforts to maintain their proficiency in Russian and expressed pride in their ability to speak multiple languages fluently which enabled them to navigate different cultural contexts and interact successfully with people from different backgrounds.

Eduard Alexandrowitsch dreamed of visiting Askania Nova, his family manor, and this is what motivated him to connect to different Soviet and post-Soviet people coming to Europe. He was curious about their way of life, and he was interested in speaking Russian to them. He would invite new acquaintances to stay in his house, and sometimes he lost money trying to help them. The owner of a big and popular souvenir shop, he would come to the entrance to welcome Russian-speaking visitors personally. When his name became famous in Russia and Ukraine, thanks to his donations of valuable documents and art objects, journalists were eager to meet him. A lot of videos testify to his willingness to communicate with interviewers from Russia and Ukraine (see, e.g., Videos 1, 2,[2] 3,[3] and 4[4] used as material for his linguistic portrait). These documentaries demonstrate his friendliness and good humor.

He outlived most of his peers and he did not conceal his sadness about it. He told Shuster:

[…]we were an example to be emulated by the people. We had to be such… so as not to cause scandals, we were watched… people watched how we lived our life. And so, it’s a shame that, as I said, ‘the ball is over’.

At the time of the interview, the Baron had little opportunity to meet people of the same age group. He said,

It is sad that the first emigration [wave], those people most interesting and unique, the families of Russia had to leave. three million of the most famous names… they have passed away. You can count on the fingers of one hand those people from that emigration [wave], aristocrats, like my family, who are still alive. And if they are alive, they are worthless. I don’t understand myself. I’m 88, this is my age, but I feel as if I were 30. I live, and I understand everything, I keep up with events and I do things, I act, I work, and so on. And those who still remain, they are already worthless. They visit me for tea, and when I talk. ‘What? How? Tell me again…’ They can no longer understand how things are. And, unfortunately, I can name, maybe… Well, my friend Prince Trubetskoy in Paris and then Prince Lobanov-Rostovsky. I don’t see [anybody] anymore. These are my biggest friends abroad.

The Baron was a gerontologic phenomenon. Every morning, he started his day with two slices of brown bread with honey or jam, a big cup of a milk flavored drink Ov(om)altine (a Swiss choco-malt drink), which he used to call his dope, and bananas. Among his favorite dishes was Russian kefir which he drank with sugar. He was proud of the borsch he could cook, calling his recipe “Baron’s borsch” and would always ask the author to make Pozharsky patty cakes, “as tender as my mum used to make.” Despite his gourmet tastes, he used to say that his whole life, he ate as little as a bird. He surprised people much younger than him by the quality of his life and energy (Snegirev). He was 105 years old in September 2017 when the pictures illustrating this essay were taken. Jokingly, he said that the best place in the world was his bed. After all, he slept on the Red Square. The Lemercier’s carpet representing St. Basil the Blessed Cathedral was right above his head in the bedroom. It belonged to the Moscow Patriarchate before the revolution.

Baron Eduard Alexandrowitsch von Falz-Fein died at the age of 106 under tragic circumstances. On the 17th of November 2018, his house caught fire. The fire brigade found the owner dead. Apparently, he suffocated due to an excess of carbon dioxide (Danilevich). According to his testament, his property was to be divided between the Russian Museum and his daughter Liudmila. Today the house is deserted. What will become of the objects the Baron lovingly assembled and preserved? Like people, objects have biographies and who knows what future awaits these remnants of the past.

Whatever the situation in which he found himself, whatever clothes he was wearing, whatever tasks he took upon himself, Eduard Alexandrowitsch tried to live up to his idea of what a true aristocrat is. There was great moral dignity in his state of mind, behavior, and relations with people. Until the end, he remained handsome. His secret was in being creative and enjoying whatever he was doing.

I do not regret a single minute of my life, [I don’t regret] how I lived it, how I spent it, how I tried to live the way one should live, and I did not offend anyone, I was friends with everyone, I don’t have, I hope I don’t have a single person who I ever quarreled with (Video 1).

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

Works Cited

Alekseev, Denis A. Genealogia v emigrantskoy memuaristike 1920–1950kh gg, A PhD Thesis, MGU, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

Anisimova, Mariia S. Mifologema “dom” i eie khudozhestvennoye voploschenie v avtobiograficheskoy proze pervoy volny russkoy emigratsii: na primere romanov I.S. Shmeleva “Leto Gospodne” i M. A. Osorgina “Vremena”, A PhD Thesis, Nizhegorodskii GPU, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

Bamberg, Michael. “Biographic-narrative research, quo vadis? a critical review of ‘big stories’ from the perspective of ‘small stories’.” Narrative, Memory and Knowledge: Representations, Aesthetics, Contexts, edited by Kate Milnes et al., University of Huddersfield Press, 2006, pp. 63–79.Search in Google Scholar

Bamberg, Michael, and Alexandra Georgakopoulou. “Small stories as a new perspective in narrative and identity analysis.” Text & Talk, vol. 28, 2008, pp. 377–396.10.1515/TEXT.2008.018Search in Google Scholar

Bornat, Joanna. “Biographical methods.” The sage handbook of social research methods, edited by Pertti Alasuutari et al., Sage, 2008, pp. 344–356.10.4135/9781446212165.n20Search in Google Scholar

Chang, Heewon. “Individual and collaborative autoethnography as method: a social scientist’s perspective.” Handbook of Autoethnography, edited by Stacy Holman Jones et al., Routledge, 2016, pp. 107–122.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, Aaron J. “Our Russian passport’: first world war monuments, transnational commemoration, and the Russian Emigration in Europe, 1918–39.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 49, no. 4, 2014, pp. 627–651.10.1177/0022009414538469Search in Google Scholar

Danilevich, Nadezhda V. Baron Falz-Fein. Zhizn’ russkogo aristokrata. Izobrazitel’noye Iskusstvo, 2000.Search in Google Scholar

Danilevich, Nadezhda V. “Poslednii poklon. Pamiati Barona Eduarda Falz-Feina.” Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn’, no. 1, 2019, pp. 197–208.Search in Google Scholar

Efremenko, Valentin V. Deiatel’nost’ nauchnykh i kul’turnykh uchrezhdeniy rossiyskoy emigratsii vo Frantsii. 1917–1939 gody. A PhD Thesis, MGOU, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Carolyn. The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. AltaMira Press, 2004.Search in Google Scholar

Ermakova, Natalia I. “The Russian orthodox church and Russian emigration as documented in the archives of the Western American diocese of the Russian orthodox church outside of Russia.” Slavic & East European Information Resources, vol. 21, no. 1–2, 2020, pp. 94–102. doi: 10.1080/15228886.2020.1756815 Search in Google Scholar

Gan, G. “‘And with Me, My Russia/I Bring Along in a Travelling Bag’: Literary and Ethnographic Narratives of Russian Exile and Emigration, Past and Present.” Revolutionary Russia, vol. 32, no. 1, 2019, pp. 154–179. doi: 10.1080/09546545.2019.1607023.Search in Google Scholar

Grankov, Dmitrii A. Russkaya usad’ba v emigrantskoy memuaristike. A PhD Thesis. MGOU, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

Granovskaya, Lidiya M. Russkiy yazyk v “rasseianiye”. Ocherk po yazyku russkoy emigratsii pervoy volny. Institut russkogo yazyka RAN, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

Longman, J. “A seat near Hitler and other olympic tales from the baron.” The New York Times, 15 October 2017, SP1. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/12/sports/olympics/baron-olympics-hitler-liechtenstein.html.Search in Google Scholar

Naidenova, VO., et al. “Fridrikh eduardovich falz-fein, patriot i metsenat.” Tvarinntstvo Ukraini, no. 4, 2013, pp. 36–37.Search in Google Scholar

Raeff, M. Russia Abroad: A cultural history of the Russian Emigration, 1919–1939. Oxford UP, 1990.Search in Google Scholar

Reinhardt, RO. “Pochetnyi posol Rossii.” Observer, vol. 11, 2017, pp. 108–115.Search in Google Scholar

Riemann, G. “An introduction to ‘doing biographical research.” Historical Social Research, vol. 31, no. 3, 2006, pp. 6–28.Search in Google Scholar

Rogatchevskaia, Ekaterina. “A beautiful, tremendous Russian book, and other things too.” Canadian-American Slavic Studies, vol. 51, no. 2–3, 2017, pp. 376–397.10.1163/22102396-05102009Search in Google Scholar

Romanova, L. “Venskii bidermayer i al’bom iz Gavrilovki.” Diskussiya, vol. 7, 2011, pp. 49–54.Search in Google Scholar

Rupova, R. “Migration as a form of cultural transmission: European ways of Russian thought in the Twentieth Century.” Global Migration Trends 2020: Security, Healthcare and Integration, RUDN, 2020, pp. 895–905.Search in Google Scholar

Savinova, Natal’ya V. Rossiiskiy natsionalizm i nemetskie pogromy v Rossii v gody pervoy mirovoi voiny (1914–1917). A Ph.D. Thesis. St. Petersburg SU, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

Shchuplenkov, Oleg V. Sokhraneniye i formirovaniye natsional’no-kul’turnoy identichnosti u molodezhi rossiyskogo zarubezhya v 1920–1930-e gody. A PhD Thesis. Tambov STU, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Shuster, S. Litsom k litsu: lider otvechayet zhurnalistam, 17 September 2000, svoboda.org/a/24198018.html.Search in Google Scholar

Snegirev, Vladimir. “Falz-Fein: Ia optimist i smotriu v buduschee Rossii s nadezhdoi.” Rossiyskaia Gazeta, no. 205, 6 September 2012, rg.ru/2012/09/06/baron.html.Search in Google Scholar

Tolstoy, Andrei V. Russkaya khudozhestvennaya emigratsia v Evrope. Pervaya polovina 20 veka. A PhD Thesis. NII teorii i istorii izobrazitel’nykh iskusstv, 2002.Search in Google Scholar

Tolstoy, Ivan N. Radio Svoboda na etoy nedele 20 let nazad. Kak baron Falz-Fein ustroil Moskve Olimpiadu, 10 September 2020. svoboda.org/a/30804593.html.Search in Google Scholar

Voloshina, Valentina Y. Sotsial’naya adaptatsia uchenykh-emigrantov v 1920–1930-e gg. A Ph.D. Thesis. Omskii GU im. F. M. Dostojevskogo, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Voronova, Elena V. Mifologia povsednevnosti v kul’ture russkoy emigratsii 1917–1939 gg. (na materiale memuaristiki). A PhD Thesis. Vjatskij GGU, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

White, Elizabeth. “The struggle against denationalisation: The Russian Emigration in Europe and education in the 1920s.” Revolutionary Russia, vol. 26, no. 2, 2013, pp. 128–146.10.1080/09546545.2013.856076Search in Google Scholar

Zadereichuk, Anna A. “Obraz Falz-Feinov v memuarakh i dnevnikakh.” Uchenye Zapiski Krymskogo Federal’nogo Universiteta im.” V. I. Vernadskogo. Seria Istoricheskie Nauki, vol. 1, no. 4, 2015, pp. 11–20.Search in Google Scholar

Zelenin, Aleksandr V. Yazyk russkoy emigrantskoy pressy (1919–1939), Zlatoust, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

Zemskaya, Elena A. (ed.) Yazyk russkogo zarubezhya: Obschie protsessy i rechevye portrety. Yazyki slavianskoi kul’tury, 2001.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Writing the Image, Showing the Word: Agency and Knowledge in Texts and Images, edited by Jørgen Bakke, Jens Eike Schnall, Rasmus T. Slaattelid, Synne Ytre Arne - Part II

- Cultural Syncretism and Interpicturality: The Iconography of Throne Benches in Medieval Icelandic Book Painting

- Rousseau’s Herbarium, or The Art of Living Together

- Special Issue: Russian Speakers After Migration, edited by Ekaterina Protassova and Maria Yelenevskaya

- Introduction: Everyday Verbal and Cultural Practices of the Russian Speakers Abroad

- Failing or Prevailing? Russian Educational Discourse in the Israeli Academic Classroom

- Cultural and Linguistic Capital of Second-Generation Migrants in Cyprus and Sweden

- Russian-Speaking Families and Public Preschools in Luxembourg: Cultural Encounters, Challenges, and Possibilities

- “I’m Home”: “Russian” Houses in Germany and Their Objects

- Conceptualizing Russian Food in Emigration: Foodways in Culture Maintenance and Adaptation

- From Odessa to “Little Odessa”: Migration of Food and Myth

- Domestication of Russian Cuisine in the United States: Wanda L Frolov’s Katish: Our Russian Cook (1947)

- A Russian Aristocrat in the Principality of Liechtenstein: Life Trajectories, Material Culture, and Language

- A Russian Story in the USA: On the Identity of Post-Socialist Immigration

- Special Issue: Plague as Metaphor, edited by Nahum Welang

- Introduction: How Metaphors Remember and Culturalise Pandemics

- The Humanities of Contagion: How Literary and Visual Representations of the “Spanish” Flu Pandemic Complement, Complicate and Calibrate COVID-19 Narratives

- “We’ve Forgotten Our Roots”: Bioweapons and Forms of Life in Mass Effect’s Speculative Future

- The Holobiontic Figure: Narrative Complexities of Holobiont Characters in Joan Slonczewski’s Brain Plague

- “And the House Burned Down”: HIV, Intimacy, and Memory in Danez Smith’s Poetry

- Regular Articles

- Social Connection when Physically Isolated: Family Experiences in Using Video Calls

- “I’ll see you again in twenty five years”: Life Course Fandom, Nostalgia and Cult Television Revivals

- How I Met Your Fans: A Comparative Textual Analysis of How I Met Your Mother and Its Reboots

- Transnational Business Services, Cultural Transformation/Identity, and Employee Performance: With Special Focus on Migration Experience and Emigration Plan

- Rethinking Agency in the European Debate about Virginity Certificates: Gender, Biopolitics, and the Construction of the Other

- The Mirror Image of Sino-Western in America’s First Work on Travel to China

- Strategies of Localizing Video Games into Arabic: A Case Study of PUBG and Free Fire

- Aspects of Visual Content Covered in the Audio Description of Arabic Series: A Corpus-assisted Study

- Translator Trainees’ Performance on Arabic–English Promotional Materials

- Youth and Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Intelligence in Latvia, Spain and Turkey

- On the Happening of “Frank’s Place”: A Neo-Heideggerian Psychogeographic Appreciation of an Enchanted Locale

- Rebuilding Authority in “Lumpen” Communities: The Need for Basic Income to Foster Entitlement

- The Case of John and Juliet: TV Reboots, Gender Swaps, and the Denial of Queer Identity

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Writing the Image, Showing the Word: Agency and Knowledge in Texts and Images, edited by Jørgen Bakke, Jens Eike Schnall, Rasmus T. Slaattelid, Synne Ytre Arne - Part II

- Cultural Syncretism and Interpicturality: The Iconography of Throne Benches in Medieval Icelandic Book Painting

- Rousseau’s Herbarium, or The Art of Living Together

- Special Issue: Russian Speakers After Migration, edited by Ekaterina Protassova and Maria Yelenevskaya

- Introduction: Everyday Verbal and Cultural Practices of the Russian Speakers Abroad

- Failing or Prevailing? Russian Educational Discourse in the Israeli Academic Classroom

- Cultural and Linguistic Capital of Second-Generation Migrants in Cyprus and Sweden

- Russian-Speaking Families and Public Preschools in Luxembourg: Cultural Encounters, Challenges, and Possibilities

- “I’m Home”: “Russian” Houses in Germany and Their Objects

- Conceptualizing Russian Food in Emigration: Foodways in Culture Maintenance and Adaptation

- From Odessa to “Little Odessa”: Migration of Food and Myth

- Domestication of Russian Cuisine in the United States: Wanda L Frolov’s Katish: Our Russian Cook (1947)

- A Russian Aristocrat in the Principality of Liechtenstein: Life Trajectories, Material Culture, and Language

- A Russian Story in the USA: On the Identity of Post-Socialist Immigration

- Special Issue: Plague as Metaphor, edited by Nahum Welang

- Introduction: How Metaphors Remember and Culturalise Pandemics

- The Humanities of Contagion: How Literary and Visual Representations of the “Spanish” Flu Pandemic Complement, Complicate and Calibrate COVID-19 Narratives

- “We’ve Forgotten Our Roots”: Bioweapons and Forms of Life in Mass Effect’s Speculative Future

- The Holobiontic Figure: Narrative Complexities of Holobiont Characters in Joan Slonczewski’s Brain Plague

- “And the House Burned Down”: HIV, Intimacy, and Memory in Danez Smith’s Poetry

- Regular Articles

- Social Connection when Physically Isolated: Family Experiences in Using Video Calls

- “I’ll see you again in twenty five years”: Life Course Fandom, Nostalgia and Cult Television Revivals

- How I Met Your Fans: A Comparative Textual Analysis of How I Met Your Mother and Its Reboots

- Transnational Business Services, Cultural Transformation/Identity, and Employee Performance: With Special Focus on Migration Experience and Emigration Plan

- Rethinking Agency in the European Debate about Virginity Certificates: Gender, Biopolitics, and the Construction of the Other

- The Mirror Image of Sino-Western in America’s First Work on Travel to China

- Strategies of Localizing Video Games into Arabic: A Case Study of PUBG and Free Fire

- Aspects of Visual Content Covered in the Audio Description of Arabic Series: A Corpus-assisted Study

- Translator Trainees’ Performance on Arabic–English Promotional Materials

- Youth and Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Intelligence in Latvia, Spain and Turkey

- On the Happening of “Frank’s Place”: A Neo-Heideggerian Psychogeographic Appreciation of an Enchanted Locale

- Rebuilding Authority in “Lumpen” Communities: The Need for Basic Income to Foster Entitlement

- The Case of John and Juliet: TV Reboots, Gender Swaps, and the Denial of Queer Identity