Abstract

This study examines the multimodal pragmatic abilities of older adults experiencing typical aging in contrast to those with Alzheimer’s disease, via the statistical and comparative analysis of harmful illocutionary forces expressed in their discourse. The results indicated that individuals with Alzheimer’s disease showed a noticeable lack of emotional engagement, which hindered the felicity of illocutionary forces. Furthermore, these patients struggled to use appropriate prosodic indicators, alongside a diminished integration of conventional gestures. Highlighting the significance of multimodal illocutionary force indicators in speech acts, this study contributes to a more intricate comprehension of interpersonal communication.

1 Introduction

The intensification of population aging has precipitated a rise in the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which impairs the older adults’ semantic memory and emotional experience, leading to atypical daily behaviours that undermine both communicative abilities and overall quality of life. Notwithstanding the adverse effects of AD on language, systematic explorations into language changes associated with senescence, and particularly pragmatic competence, have been scant. A focused analysis of pragmatic attributes of AD patients can potentially enhance the sensitivity of early dementia diagnosis. Therefore, the primary goal of our study was to perform a comparative study and to investigate different harmful illocutionary forces expressed by older adults with and without Alzheimer’s disease.

The study utilized a self-built multimodal corpus to examine the role of emotions, gestures, prosody and bodily movement in situated discourse. It inherits Gu (2013a, 2013b) and Huang (2017) ’s classification of illocutionary forces[1] from personal ‘interests’ into four groups of neutral, beneficial, harmful, and counterproductive illocutionary acts. This categorical approach recognizes that emotions are commonly tied to the participants’ interests, and manifest through prosody, facial expressions, and body movement. ‘Harmful illocutionary forces’, our research focus, are therefore defined as those in which the discourse affects the interlocutors’ interests adversely, including “sadness,” “rejection,” “complaint,” and “fear,” etc. This investigation focuses on the variances in the expression of harmful illocutionary forces among seniors experiencing normal aging and those with Alzheimer’s disease.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Illocutionary Forces and Multimodal Corpus Linguistics

Against the background of the ‘linguistic turn’ in Western philosophy, Austin (1962) proposed the Speech Act Theory in the 1950s, and further elaborated by Searle (1969), thriving as a classic topic in pragmatics. Austin (1962) holds that as far as the speakers are sincere when they make the utterance, they are ‘doing things with words’ and producing the corresponding illocutionary force. As the first scholar to put forward a set of speech act theories and the concept of an ‘indirect speech act,’ Searle made a unique contribution to speech act theory. Following Searle (1969, 21), speech act is the most basic unit of human communication. Based on the discussion of (1) the illocutionary point of a speech act, (2) the direction of fit between discourse and the objective world, (3) the psychological states of discourse expression, (4) force or strength of the point, (5) status or position of the hearer or speaker, (6) way the utterance relates to the interests of the hearer or speaker, (7) relations to the rest of the discourse, (8) propositional content, (9) requirement that some acts must be speech acts while others need not be, (10) lack or need for extra-linguistic institutions, (11) lack of or need for illocutionary verbs, and (12) style of performance, Searle (1979) divided speech acts into five categories: assertives, directives, commissives, expressives, and declarations. However, the criteria of his taxonomy was based on the speaker’s ‘intentionality’, overlooking the fact that speech acts are social behaviours in nature (Huang 2021b) and serve as pivotal benchmarks for assessing the pragmatic competence in older adults (Huang and Yang 2023). Correspondingly, the investigation of illocutionary force indicating devices (IFID) was narrow and inadequate, mainly focusing on the linguistic means (Huang 2018).

The development of modern multimedia technology reveals the essence of language activities, and the data that linguists concerned changed from monomodal to multimodal. Linguists began to pay increasing attention to the fact that verbal and nonverbal cues fit together into integrated messages in daily interaction. With such a background, multimodal corpus comes into being as the ‘Corpus 4.0’ (Knight 2009), which provides a richer representation of different aspects of discourse, including participants’ utterance content, prosody, gestures, and also the context or co-text in which interaction takes place (Huang 2021a). The adoption of the multimodal corpus in pragmatic research provides the classic theories with fresh perspectives and new practices (Knight and Adolphs 2008).

So far, few studies utilized multimodal corpus-based approaches. Nevertheless, Gu (2013a) made a breakthrough in this regard, presenting a conceptual model for empirically studying the tripartite interaction between illocution, emotion and prosody based on cases taken from the Spoken Chinese Corpus of Situated Discourse (SCCSD). Gu unprecedentedly investigated speech acts as human behavior rather than treating language use as sheer information-exchanging activity, while such non-verbal cues as facial expressions, gestures, and bodily movements were absent from the analysis (Huang 2018).

In this study, Gu’s analytic framework is refined to some extent, and other cues including gestures and bodily movement, indispensable components of the felicitousness of illocutionary acts performed by ‘the whole person,’ have been taken into account. To bring to the fore the close relations between illocutionary force tokens, the speaker’s individuality, and the discursive environment, illocutionary forces are examined in the context of Chinese situated discourse.

Filiou et al. (2024) suggest that speech acts serve as a valuable tool for gaining insights into how AD older adults perceive and tackle daily activities, as well as the consequences of their choices of actions. Our study examines the harmful illocutionary forces in speech by elderly individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), noting their increased expression of negative emotions and unpredictable behaviours, such as irritability and pessimism (Huang and Che 2023). By identifying how these individuals’ speech acts are marked by sudden emotional shifts, it may inform tailored support and communication strategies for those with AD.

2.2 Pragmatic Impairment in Dementia and Multimodal Compensation

Recent decades have witnessed an escalating scholarly interest in the pragmatic deficits exhibited in dementia patients, with the contrast between healthy and cognitively impaired older adults occupying the spotlight of academic inquiry. Drawing upon empirical evidence sourced from the Chinese context, seminal investigations conducted by Huang, Yang, and Liu (2021), alongside Zhou and Huang (2023), have begun to scrutinize the speech act execution among cognitively healthy and impaired older adults. Earlier research has encapsulated an array of pragmatic deficits associated with elderly individuals afflicted by Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). These encompass challenges with forward-and-backward interdependency, speech act repetition, vague deixis, compromised emotional expression, vague self-awareness, and the need for multimodal communicative strategies (Huang and Che 2023).

However, the pragmatic compensation mechanisms advance the communication under some circumstances. Research has found that cognitively impaired individuals often rely on physical contacts to initiate, maintain or strengthen interactions (Magai, Cohen, and Gomberg 1996); and those with aphasia use non-verbal resources to compensate for their compromised verbal abilities (Perkins 2007; Simmons-Mackie and Stoehr 2016). Both interpersonal and intrapersonal compensatory adaptation operates in the interaction of the elders with AD (Huang, Yang, and Liu 2021; Zhou and Huang 2023). Among these studies, some focus on the production of co-speech gestures. Older adults reportedly deploy more referential nonverbal behaviors to communicate complex content (Asplund, Jansson, and Norberg 1995), with an increase in iconic gestures, which have a high semantic load, to support their verbal discourse that might probably otherwise be perceived as more affected by the memory deficits (Geladó, Gómez-Ruiz, and Diéguez-Vide 2022). Alzheimer’s patients usually favor congruent co-speech gestures over incongruent ones, which facilitate their comprehension (Eggenberger et al. 2016). In addition, AD patients often resort to non-verbal resources to communicate and express their emotions, though they cannot directly deliver the propositional content in performing speech act (Cummings 2009). It has been observed that cognitively impaired seniors employ laughter as a compensatory act to overcome communication disorders, and to acknowledge their troubles in comprehension and expression of utterances (Kasper 2006).

Preliminary investigations into the pragmatic deficits of older individuals with cognitive disabilities have commenced from a multimodal standpoint. However, studies detailing the specific attributes and mechanisms of pragmatic disorder and multimodal compensation in communication, remain scant.

2.3 The Multimodal Perspective of Investigating Illocutionary Forces and Emotions

The enactment of speech acts involves a multimodal interplay – not merely verbal, but also dynamic and expressive – through which illocutionary force is generated, transmitted, and received, as postulated by Huang (2017). Among those non-verbal cues, emotions are fundamental to the performance and interpretation of speech acts, linking intentionality with communicative action (Alba-Juez and Larina 2018; Goldie 2002; Gu 2017). Additionally, emotions are usually related to the interest of interlocutors and emotions further influence and are conveyed by facial expressions, prosodic features and gestures (Huang 2021a; Johar 2016; Martin and Devillers 2009). Many studies pointed out that prosodic features such as intonation, pitch, speech rate and stress are not only alternatives to realizing illocutionary acts but also IFIDs (Austin 1962; Searle 1969), which play an essential role in the older adults’ expression of IF.

Given this interrelation, it is quite necessary to investigate how multimodal information has been impacted by speakers’ occurrent emotions, and how the triadic interaction of emotion, prosody, and non-verbal acts demonstrates harmful illocutionary forces.

This study follows the hierarchical method of Gu (2013a) and divides emotional states into three tiers: background emotion, primary emotion, and social emotion. Background emotions hinge on the speaker’s physical conditions, such as well-being, fatigue, anxiety, etc.; primary emotions refer to universal human emotions, including happiness, sadness, fear, and even no emotions; and social emotions are emotions learned socially, which can be divided into two main sources (other-directed and self-directed) and three types (positive, neutral, and negative). This study will annotate the emotions in speech acts based on the classification.

3 Discovery Procedures of Illocutionary Forces

The principle, rationale, and characteristics of the Discovery Procedure are oriented towards examining the illocutionary forces within situated discourse and employs the technique of Simulative Modelling.

3.1 Fundamental Principle

Primarily, the Discovery Procedure is developed according to the ‘live, whole person’ principle proposed by Gu (2013b), which advocates that cues like prosody, bodily movement, and postures are all indispensable components of the felicitous performance of illocutionary acts in situated discourse. Therefore, the eloquent ‘live, whole person’ in discourse activities constitute the object of Simulative Modelling (Huang 2021b). Accordingly, such cues as prosody, facial expressions, gestures, postures, and bodily movements should be considered.

Under the methodology of Simulative Modelling, illocutionary forces in situated discourse are modelled and investigated through the four perspectives, i.e. what is said, what is thought, what is felt, and what is embodied (STFE Principle).

3.2 Analytical Framework

To analyse the interactive relationships between illocutionary force, emotions, and prosody, Gu (2013a) proposed a ‘Discovery Procedure for the tripartite interaction’. Aiming to improve such procedure of analysis, Huang (2021b) established his refined procedure with the distinctive addition of gestures (including facial expressions, physical attributes, and postures) and situational factors. The Discovery Procedure contains five programme segments, including the conceptual model of illocutionary force, situational factors, emotional states, prosodic features, and gestures. In the following sections, elaboration is given on the basic framework, connotations, and analytic methods of the Discovery Procedure.

The conceptual model

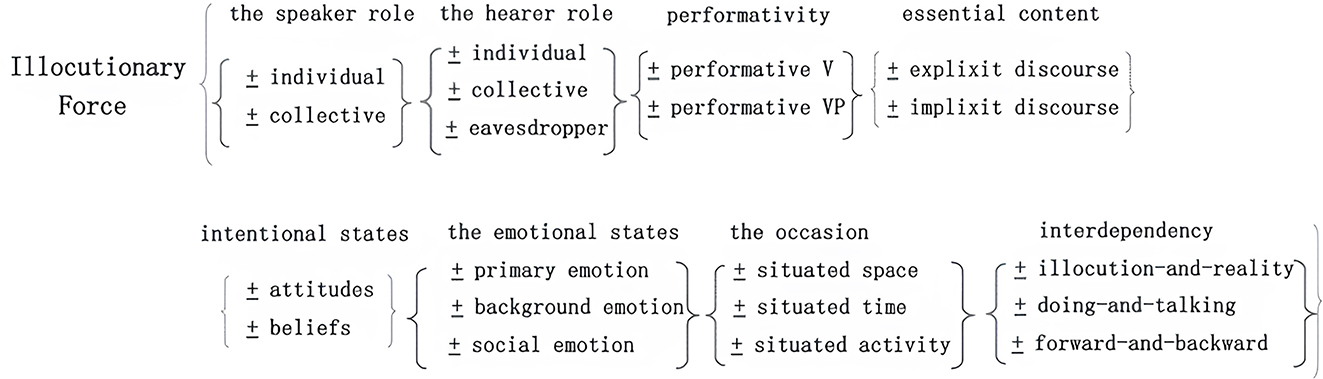

Illocutionary act-tokens in situated discourse are abstracted and generalized from different angles through concept modelling. It should be noted that here we adopt Gu’s (2013a) ‘octet scheme’ to shape our Conceptual Model. Having considered the basic forms of illocutionary force and the relevant characteristics and influential factors of the discourse it situated, the ‘octet scheme’ is represented. The Conceptual Model established by this formalized method describes and defines the characteristics and properties of a certain type of illocutionary force and provides perspectives for investigating the felicity/infelicity of certain illocutionary forces type in situated discourse.

The Conceptual Model of illocutionary force adopts the ‘octet scheme,’ as shown in Figure 1.

Data modelling

In this study, data modelling aims to prepare the required data types for the study of live illocutionary forces (IFs) from the perspective of the STFE-match principle, i.e., what is said, what is thought of, what is felt, and what is embodied.

Specifically, the data sets of text layer, audio layer, and video layer were constructed based on AntConc, Praat, and Elan. The implementation and evaluation stage are reflected in the annotator using the above-mentioned software to annotate and present the data of multiple layers according to the dimensions of concept modelling, to check whether the resultant data conform to concept modelling, and thus to lay the data foundation for the subsequent descriptive analysis of speech acts.

In this corresponding and multiple-tier scheme, eight tiers have been established to annotate speech acts (see Table 1) with the information from different perspectives conforming to our research target. The fundamental purpose of concept modelling and data modelling is to depict and reveal the characteristics and compensatory mechanisms of the language impairment of older adults with AD.

Conceptual model of illocutionary force.

The eight tiers of annotation.

| (1) Performance unit of illocutionary force | A specific instance of a certain speech act type performed by a speaker in the specific situation (Huang 2019) |

| (2) Background emotion | The emotional states that are closely related to the physical and mental condition of the speaker, such as anxiety, fatigue, discouragement, malaise, relaxation, well-being, enthusiasm, and energy |

| (3) Primary emotion | Seven types of primary emotion, i.e. joy, anger, sadness, fear, disgust, surprise, and anxiety |

| (4) Social emotion | Subcategorized into: (1) positive social emotions, (2) negative social emotions, and (3) neutral social emotions (Gu 2013a) |

| (5) Intonation group | Segmented by the ‘external criteria’, e.g. the phonetic cues, such as pauses etc. |

| (6) Prosodic pattern | The pitch, length, and loudness of the sound. The judgment is from the acoustic cues presented by ‘Praat’, including fundamental frequency, duration, intensity, spectrum, etc. |

| (7) Other prosodic features | The information of stress, pause, quality of the sound, and other para-linguistic cues, including laughter, sigh, cough, weeping, etc. |

| (8) Non-verbal act | The body language in its narrow sense, including eye contact, facial expression, head and hand movement, body posture, etc. |

4 Data Collection and Processing

The life course data were collected from interviews with 20 cognitively healthy older adults and 20 with Alzheimer’s disease.[2] The length of interviews varied from one to one based on each elder’s situation, with an average length of about 1 h per person. After trial runs and data collection, a raw corpus with audio and video of 39.52 h, i.e., a multimodal data corpus, was built. The corpus consists of situated discourse, i.e., discourse that has not been rehearsed, prepared, or informed in advance.

In this study, 113 tokens of the harmful illocutionary force were expressed by cognitively healthy older adults, while 103 that of AD older adults in the corpus.

4.1 Data Sources and Collecting Methods

The corpus was collected in community senior activity centres, senior service centres, community activity centres for senior Communists, and Grade A tertiary hospitals. All participants had signed informed consent for data collection. The life course data were collected using a wireless digital voice recorder (SONY SX2000-A10) with sampling rates of 16 kHz and 44.1 kHz, and a high-sampling rate CNC camera (SONY FDR-AX60) to capture video streams.

This study’s data collection and research scheme were reviewed by the research ethics committee of the author’s institution under the review number tjsflrec202101.

4.2 Data Processing and Annotation

The annotation scheme follows the STFE-match principle (Gu 2013b) and adopts the primary thought of ‘Simulative Modelling’ to compile a multimodal corpus that approximates, as faithfully, as accurately, and as fully as possible, the whole person’s total saturated experience with total saturated signification in situated discourse.

Faced with miscellaneous illocutionary force tokens in situated discourse, Gu (2013a) suggested that they should be classified from the perspective of the relations between ‘what is talked about’ and the speaker/hearer’s interests. In this regard, speech acts are classified according to discourse activities which carry illocutionary forces/acts, following the method of examining speech acts at the level of behaviour activities (discourse activities). Classifying Speech act from a discourse perspective, oriented toward the speech acts in natural discourse, has built a bridge between speech acts and the discourse in which they are located (Adolphs 2008, 47). This study will focus on the indication of harmful illocutionary forces.

In order to ensure the accuracy, objectivity, and consistency of corpus annotation, this study used internal testing (intra-annotator consistency) and external validation (expert reliability and validity tests) to evaluate the quality of annotation. It shows that the intra-annotator consistency is 0.813, the professional verification of validity is 0.820, and the reliability is 0.631, all statistically significant. Overall, the annotation was reliable and valid, which effectively reflected the illocutionary force in Chinese situated discourse.

5 A Comparative Study of the Two Groups in Performing Harmful Illocutionary Force

In Chapter 5, the harmful IFs of cognitively healthy older adults are analysed to identify patterns and speech characteristics. The goal is to set a pragmatic competence benchmark for older adults and to compare these patterns with those of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patients. Furthermore, the chapter explores the multimodal aspects of the harmful IFs exhibited by older adults with AD, providing insights into how cognitive health influences the language use in older adults.

5.1 The Multimodal Features of the Older Adults with Normal Aging in the Expression of Harmful Illocutionary Force

In 113 tokens of the harmful illocutionary force, the five most frequent tokens are 44 instances of the IF of bao’yuan (complaining), 31 of su’ku (grumbling), 18 of ju’jue (refusing), 8 of fan’si (self-reflection), and 4 of hai’pa (feeling scared).

This section draws on the multimodal nature of IF and the multidimensionality of IFIDs. Such IF expressive devices as emotions, prosodic features and gestures bear different significance and collaborate in the performance of illocutionary acts and then the production of IFs.

5.1.1 Emotions

Emotions include background emotion, primary emotion, and social emotion.

Background emotions hinge on the speaker’s physical conditions, such as well-being, fatigue, anxiety, etc. The healthy older adults have shown the background emotion of “relaxed” or “well-being”.

As mentioned, primary emotions can be classified as positive, negative, or default. In the harmful class, the primary emotions are mainly negative, accounting for 69 %, including anger, sadness, fear, and disgust. A small proportion (23.9 %) of older adults did not show distinctive primary emotion (‘default’), and only a few (8 %) expressed positive emotions. This is related to the definition of the harmful classification of IF, since its essential content is negative or will have a negative effect on the speaker’s interest. Indeed, in some cases, if the elder has been relieved of a previous harmful situation, he or she could stay calm when talking about it. This explains why the primary emotion of default has been annotated in some tokens of the harmful class.

Among the tokens of harmful IF in this corpus, social emotions are mainly negative, including “other-directed_negative_unsatisfied,” “other-directed_negative_blaming,” “other-directed_negative_complaining,” and “self-directed_negative_compassionate.” The act of “complaining” is the speaker commenting negatively on others’ words and deeds, so the emotion is usually other-directed. When complaining, the older adults expressed negative social emotions 56 times. The act of “grumbling” is the elder talking about his or her own experience, so the emotion is self-directed. In this corpus, the negative social emotions of “grumbling” account for 72 %, and that of “self-reflection” is as high as 75 %.

5.1.2 Gestures

Gestures include head movements, facial expressions, hand movements, and body postures.

The frequency of head movements in the harmful classification for healthy older adults is 38.9 %, and movements like “shaking one’s head” appeared the most (13.3 %). In some types of speech, “lowering head” (9.7 %), “nodding” (13.3 %) and “turning one’s head” (8.8 %) also existed. For example, in the “rejecting” tokens, the more frequent head movements are “shaking one’s head” and “head down,” while in the “self-reflection” tokens, only 2 head movements occur, both of which are “nodding,” which is in line with the characteristics of this class.

When expressing harmful acts, neutral expressions such as relaxation account for the vast majority (92.9 %). Facial expressions such as seriousness and worry emerge more frequently (95 %) in the tokens of feeling distressed and grumbling, which are related to the negative emotional states of older adults. There is also a high frequency of “occasional eye contact” with the listener (36 %).

In terms of hand movements, “pointing” and “knocking on the table” were present, and the body posture was mostly “sitting upright” (78.8 %).

5.1.3 Prosodic Features

Prosodic features include pitch, speech pace, tonal pattern, stress and pauses.

Pitch

The low pitch is the most frequent in 113 harmful tokens, accounting for 73.5 %, followed by the middle pitch at 65.5 %. While in the harmful classification, the low pitch mainly appears in the tokens of bao’yuan (complaining), su’ku (grumbling), and ju’jue (refusing). The discourse content negatively correlates with the interests of the speaker/hearer, so their primary emotions are primarily negative. For example, in a token expressing “sadness”, the elder intended to tell the hearer about the hardships of raising five children on her own and therefore presented a low pitch when performing the illocutionary act.

The high pitch occasionally occurred (54.9 %), mainly in the tokens of bao’yuan (complaining) and su’ku (grumbling). When performing these speech acts, cognitively healthy older adults often show strong negative emotions, including the primary emotions of anger and the social emotions of discontent and disgust. As they got emotionally engaged, their pitch level increased. In an instance of complaint, the speaker was compelled by familial pressure to marry an undesired man due to the superstition ‘chong xi’. This cultural concept posits that wedding as a happy event can bring good luck to the family and contribute to the recovery of ailing members, such as her father in this scenario. Contrary to the expectations set by this superstition, her father unfortunately succumbed to his illness shortly after the ceremony. In expressing the harmful IF, the speaker’s emotional intensity was markedly enhanced. Initially, she experienced a profound sense of injustice pertaining to her circumstances, followed by a feeling of resentment towards her father for orchestrating the marriage against her personal interest. Throughout this discourse, she consistently employs high pitches.

Speech pace

The speech pace in harmful illocutionary class is mainly fast (85 %). In the harmful classification, a fast speech pace is mainly concentrated in the tokens as complaining, anger, and fear (whose frequencies are 0.909,1,1, respectively). The speaker vents his dissatisfaction with the complaining object and is emotionally engaged. A fast speed, therefore, reflects this in prosody. For example, Mr. Ruan, who used to be a soldier, complained about the awful food in the army with strong emotions. His speech had 33 syllables in total and lasted for 7,755 ms, with a speech pace of 235 ms/syllable, which is fast according to the average syllable duration parameter (135–300 ms/syllable) of fast speech in Chinese (Wu and Zhu 2001).

The frequencies of slow speech pace are relatively low (15 %), occurring more often in the IFs of bao’yuan (complaining) and shi’wang (feeling disappointed).

Tonal pattern

The tones are primarily even and descending (90 %), with some rising and convex tones (10 %). Intonation varies as the speaker’s emotional states varies. The elder presents more distinctively negative emotions in performing harmful illocutionary acts, which causes fluctuations in the intonation. For example, the frequency of falling tone in ‘feeling sorry’ is 100 %, and a rising tone accounts for a higher proportion (75 %) in complaining and ‘feeling afraid’.

If look at the three prosodic features (pitch, speech pace, and tonal mode), we can find that the high pitch and fast tempo patterns usually occur when a speaker is emotionally excited.

Stress and pauses

Stress is found in 80 % of the utterances, with a frequency of 1 in the feeling anger token and 88 % in the complaining token. Stress is a coding method that helps speakers efficiently express their intentions, emotions, or attitudes and promotes hearers’ accurate and quick perception of these (Zhang 2014, 122). Therefore, the more a speaker expresses his or her subjective attitudes and emotions, the more stress will be present in performing the speech acts. In this corpus, cognitively healthy older adults were more likely to use stress to express anger and dissatisfaction when performing harmful IFs, most common in the tokens of complaining and grumbling. Generally, 51 out of 113 utterances had pauses, with an average duration of 0.5 s. The longest average pause (1.2 s) was found in the feeling anger token.

To further explore the correlation between emotions and multimodal features, this study used SPSS to conduct Spearman correlation analysis on relevant variables. It is found that there is a significant positive correlation between the healthy older adults’ negative emotions and multimodal features such as “bowing the head” (p = 0.04), and negative expressions (p = 0.03).

5.1.4 Correlation of Emotions, Prosodic Features and Gestures in the Harmful Class

In this section, 113 dummy variables of multimodal features in the harmful classification were input into SPSS for multidimensional scaling analysis to investigate the clustering of multimodal features. The analysis was terminated normally at iteration step 7 with stress = 0.148 and RSQ = 0.927, indicating that the results are ideal.

As we can see from Figure 2, among the tokens of harmful IF, neutral facial expression, low pitch, sitting upright, fast speed pace, stress, even tone, neutral expression and neutral background emotion belong to the same classification (in the first quadrant), reflecting the multimodal features of harmful class. Under the background emotion of “relaxed” or “well-being”, cognitively healthy older adults tend to speak faster and in an even tone. Since the discourse content is against the individual’s interest, the speech is more likely to be presented at a low pitch. In the fourth quadrant, self-directed negative social emotion, long pause, middle pace, falling tone, high pitch, and negative primary emotion are basically grouped into one class. It indicates that due to the influence of negative primary emotion, the speaker’s speech pace changes from fast to middle, the tone changes to a descending manner, and there is a high frequency of pause in the discourse. Low pitch, fast speech pace, and middle pitch, fast speed rate are the most frequent modal types.

Multidimensional scaling analysis of cognitively healthy older adults’ IF expression in the harmful class.

5.1.5 Case Study

Chou – harmful class – suku: (Huang 2021b)

ai //zhen ku ai //na shi hou shi ku a //ta men dou shuo de //ni ma ma ne // zai de hua duo hao

[sighs] Alas. really suffering at that time. They all said that it would be more consummate if your mother is still alive.

a //ni ma ma //xiang fu mei you xiang fu //ku que chi gou le //wo men mei you de chi

Your mother didn’t enjoy her life, but only suffered a lot. We suffered from hunger.

na hui lai he wo ba ba jiang //ge jiang jiang wo men ba ba //yi jin bai mi liang ge (error)

san ge ren (repair) chi liang tian //hu yi hu chi chi

I told my father when I returned … told my father. Two [error] three persons [repair] took only about a pound of flour for two days. Stir with water

duo shao can guo a //ku tou chi si lao zao

How miserable we were then.

Emotions

Primary emotion: Report – sad, angry; situated – sad, angry* (* means this emotion is weak or uncertain). The speaker is sad about her unfortunate past including suffering hunger due to poverty and experiencing her mother’s death;

Social emotion: Report – self-directed negative and pity + other – directed negative and resentful; situated – self-directed negative, pity + other-directed negative, resentful*. Since the speaker is recalling her own past miserable experiences, the emotion is self-directed. And the emotional nature is negative, misery, helplessness, and self-pity respectively in three segments;

Background emotion: It is related to the speaker’s physical condition and directly impacts the tonal pattern. Although aged over 70 years old, the speaker exhibits a remarkable degree of emotional engagement and articulates with a vigorous tone. So, the background emotion can be annotated as energy and well-being.

Gestures

Also, this old lady presents rich non-verbal cues, including wry smiles, frowning, and head shaking, and waving hands. Within this instance, the speaker’s lamentation, combined with facial expressions and other physical attributes, strongly convey the intensity of her emotional state of sorrow.

Prosodic features

Prior to the commencement of the act of suku, there is a distinctly extended and emphasized prosodic segment, specifically the syllable ‘ai.’ This segment functions as a subordinate element to a preceding pause and is markedly pronounced. Evidently, it is a profound sigh, as a modulatory particle indicative of the speaker’s sorrow and sense of helplessness regarding the forthcoming narrative of her experiences. Two exclamatory phrases follow:

zhen ku ai//na shi hou shi ku a (so hard// life then was so hard)

The intonation patterns predominantly feature a falling tone. Notably, the vocal strength diminishes, and the pitch lowers as the speaker progresses, revealing a deepening of her sadness concerning the tragic events of her past.

5.1.6 Summary

By conducting a quantitative analysis of the IFs devices in the way of elaborating the triadic interaction between emotions, prosodic features, and gestures, it is found that negative emotions, head lowering, pointing, stretching out hands, low pitch, falling tones, are typical features of harmful and counterproductive IFs.

5.2 The Multimodal Features of the Older Adults with Alzheimer’s Disease in the Expression of Harmful Illocutionary Force

In 103 instances of the harmful IF, the top five most frequent instances are 31 instances of the IF of bao’yuan (complaining), 30 of su’ku (grumbling), 19 of ju’jue (refusing), 7 of hai’pa (feeling scared), and 5 of fan’si (self-reflection).

5.2.1 Emotions

The emotional state of older adults with AD is predominantly negative when expressing harmful IFs, featuring negative primary emotions and self-directed negative social emotions. Statistically, 67.9 % of these 103 utterances conveyed negative primary emotions and 24.2 % conveyed neutral primary emotions. The background emotions in these utterances are also predominantly neutral.

5.2.2 Gestures

In terms of gestures, 49 % of the harmful IFs were expressed with head movements, mostly nodding, turning, and shaking heads. Although AD older adults often presented constant eye contact, almost half of the harmful IFs were expressed with occasional or no eye contact. The frequency of hand movements is 70.9 %, and most speakers tended to sit upright when expressing harmful IFs.

5.2.3 Prosodic Features

Stress, rapid speech pace, and even tone are the most common prosodic features in the harmful IF of older adults with AD. In 95 % of the harmful IFs, for instance, there is a fast speech pace, and in 87 %, there is an even tone.

5.2.4 Correlation of Emotions, Prosodic Features and Gestures in the Harmful Class

As previously discussed, speech acts encompass multimodal behaviors. With the decline of linguistic competence, AD seniors are inclined to ‘compensate’ their pragmatic communication from other resources, including gestures, gaze, body pose, etc. Therefore, examining IFs in older adults with AD from a multimodal perspective and exploring correlations among the multimodal features is crucial.

Figure 3 shows the clustering of the multimodal features of the 103 instances of harmful IFs. This analysis terminated naturally at the 4th iteration with stress = 0.178 and RSQ = 0.882, and the fitting results are rather ideal.

Multidimensional scaling analysis of AD older adults’ IF expression in the harmful class.

As can be seen in Figure 3, the emotional state of older adults with AD is predominantly negative when expressing harmful IFs, with features such as negative primary emotions and self-directed negative social emotions appearing on the left side of the first modal. Statistically (see Table 4 in Appendix 3), 68.0 % of these 103 utterances convey negative primary emotions and 24.3 % no primary emotions. The background emotions in these utterances are also predominantly neutral (57.3 %). In terms of gestures, 49.5 % of the harmful IFs are expressed with head movements, mostly turning (16.5 %), raising (15.5 %) and nodding heads (12.6 %). Although constant eye contacts appear more often (42.7 %) in terms of older adults with AD’ eye movements, more than a half (56.3 %) of the harmful Ifs are expressed with no and occasional eye contact. The frequency of hand movements is 70.9 %, and most speakers (74.8 %) tend to sit upright when expressing harmful IFs. In terms of prosodic features, fast pace, stress, and even tone are rather clustered in Figure 3, and these are also the most frequently appeared features in the harmful IF of older adults with AD. For example, rapid speech pace appears in 95.1 % of the harmful IFs and even tone 87.4 %.

5.2.5 Case Study (I-Interviewer, P-Participant)

I: dan shi ni jia mei mei //hai shi jing chang lai kan ni de //dui ba

But your sister often visits your, right?

P: (2s) wo bu yao ta lai //(3s) wo bu yao ta lai //wo yao wo zi ji lao gong lai ya

(2s) I asked her not to come (3s) I don’t want her to come. I want my husband to come.

I: o //dan shi ni bu shi li hun le ma

Oh, but didn’t you divorce?

P: ((Immediately head up and cast a glance at the older adults beside her in the same room))

he ni shuo guo //jie mei jian bu zhu zai yi kuai de

Told you that sisters don’t live together.

P: ni zen me you

How could you

P: shuo zhe hua //bu shi shuo guo le ma // jie mei jian bu zhu zai yi kuai de

say that! I had told you! Sisters don’t live together!

P: (6s) mei jia ren dou bu zhu zai yi kuai de //zhu yao shi kan fu mu de //you bu shi kan ni de

(6s) Every one doesn’t live together. They mainly come to visit parents, not you.

The participant LMJ (short for Li Mingjia) is a 69-year-old female with AD and a MoCA-B[3] score of 8. She speaks slowly with a low pitch and repeatedly keeps mute during the interview. According to the entire discourse content and the participant’s background information, the study learns that LMJ faces some family conflicts for divorce, having no kid, and a poor relationship with her little brother and sister. The logical coherence is poor in her pragmatic communication.

Emotions

In this case, LMJ’s emotional state is negative.

The background emotion is spry, depending on her physical and mental conditions. The primary emotion is raged. The social emotion is resentful. Her negative emotional state appears suddenly and indicates that the AD patient LMJ fails to control her emotions, even though the state aligns with the IF of complaining.

In the conversation, when the interviewer performs the IF of asking – how could her husband visit her after divorce, LMJ does not use the IF of hui’da (answering) but angrily blames the interviewer for saying that (Line 4–7). It meets the STFE-Match Assumption but lacking logical coherence to align with the forward-and-backward interdependency (FBID).

Gestures

In this example, LMJ performs the gestures of heads-down, frowning and staring (see Figure 4). When hearing the interviewer’s question about whether she has divorced, LMJ immediately heads up and glances at her roommate (see Figure 4) and then expresses the IF of bao’yuan (complaining). The reason may be LMJ’s unwillingness to let her roommate know the interviewer’s repeated content about her divorce.

Prosodic features

Upon conducting a spectrogram analysis with Praat, it becomes evident that LMJ’s speech is characterized by low pitch, slow pacing and even and falling tones.

P: he ni shuo guo //jie mei jian bu zhu zai yi kuai de

Notably, there is a sudden increase in pitch and pace when she articulates the complaining IF.

The case above demonstrates that cognitive impairment abnormalizes the emotions and attitudes of older adults with AD, making their pragmatic communication peculiar.

AD-69-F-LMJ’s facial expressions.

5.3 A Comparative Analysis of Multimodal Features in the Expression of Harmful Illocutionary Force Conducted Between the Older Adults with Normal Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease

These instances of IF expressed by people with AD and cognitively healthy older adults are transformed into binary variables and inputted into SPSS as dummy variables for a Chi-square test to explore the differences in the multimodal resources between the two groups.

5.4 Summary

According to statistical data (see Tables 3 and 4 in Appendix), both AD group and healthy group show strong negative primary emotion when expressing harmful IFs, with multimodal features such as sitting upright, stress and even tone occurring frequently. However, as shown in Table 2 participants diagnosed with AD often exhibit less consistent eye contact during interviews than their healthy counterparts. In terms of facial expressions, older adults with AD were more prone to show negative facial expression such as sadness and anger, whereas healthy controls tended to put on neutral faces, expressing tranquillity and calmness. Furthermore, compared to healthy controls, AD older adults exhibited substantially fewer head shaking and forward tilting such multimodal features. When it comes to the prosodic traits observed in elderly individuals with AD, the occurrence of low pitch and pauses is less frequent. Conversely, a rising intonation and a fast speech rate, which are indicative of heightened emotions such as excitement and anger, are more prevalent.

The Chi-square analysis of the multimodal features of harmful illocutionary acts performed by cognitively healthy older adults and older adults with AD (Notes: (a) the numbers in the middle 2 columns represent the frequency of the multimodal feature in the harmful IF; (b) the letters in the brackets represent different groups in the Chi-square analysis and the same letter represents that the differences between the listed multimodal features are minor; (c) in the column of Results of Chi-square analysis, the numbers out of the brackets are the Chi-square values and the numbers in the brackets are the significance of difference (P value). If P value < 0.05, it means that at the 95 % level, the corresponding multimodal feature is not at the same level for older adults with AD and cognitively healthy older adults. (d) Please refer to the Appendix to see more details about the frequency of other multimodal features).

| Older adults with AD | Cognitively healthy older adults | Results of Chi-square analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant eye contact | 42.7 % (a) | 57.5 % (b) | 4.724 (p = 0.03) |

| Negative facial expression | 22.3 % (a) | 5.3 % (b) | 13.430 (p = 0.000) |

| Neutral facial expression | 71.8 % (a) | 92.9 % (b) | 16.861 (p = 0.000) |

| Leaning forward | 7.8 % (a) | 19.5 % (b) | 6.170 (p = 0.013) |

| Low pitch | 49.5 % (a) | 73.5 % (b) | 13.109 (p = 0.000) |

| Fast speech pace | 95.1 % (a) | 85.8 % (b) | 5.315 (p = 0.021) |

| Rising tone | 23.3 % (a) | 10.6 % (b) | 6.239 (p = 0.012) |

| Frequency of pause | 26.2 % (a) | 45.1 % (b) | 8.360 (p = 0.004) |

6 Discussion

The study finds substantial differences between the two groups after doing a Chi-square analysis of the harmful IFs voiced by older adults with AD and older adults in cognitive health. It also summarises an initial pattern of illocutionary acts carried out by older adults with AD.

6.1 AD Older Adults Present a Certain Degree of Emotional Apathy and Are Troubled by Affective Disorders and Infelicity Compared with Cognitively Healthy Older Adults

The analysis in Chapter 5 shows that when expressing certain type of IF, older adults in good cognitive health are typically able to convey the corresponding emotions. Statistical data (see Appendix 2 and 3) indicates that the percentage of negative social emotions is notably reduced in the AD group, with other-directed social emotions at 21.4 % and self-directed social emotions at 39.8 %, compared to cognitively healthy older adults where these figures stand at 29.2 % and 41.6 % respectively. In contrast, the AD group exhibits a much higher frequency (35.9 %) of neutral social emotions. This suggests that older adults with AD did not meet the felicity condition when performing speech acts, because they were unable to display the accompanying emotions when expressing IFs with clear emotional inclinations (Austin 1962). According to the classical Speech Act Theory, emotion is the constitutive condition of illocutionary acts and correlating to its appropriateness.

Research has demonstrated that older adults with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) often suffer from an emotional recognition disorder, i.e., the inability to infer the mental states of others, process information, navigate social contexts, and adjust their behaviour appropriately. Such deficits often lead to adverse outcomes such as social dysfunction and difficulties in grasping the nuances of interpersonal dynamics (Zhang et al. 2020). As AD progresses, afflicted individuals encounter a significant risk, ranging from 35 % to 85 %, of developing neuropsychiatric issues including apathy, depression, anxiety, and agitation. Moreover, emotional apathy is the most predominant symptom in dementia patients, surpassing other conditions (Zhao et al. 2016). Studies additionally point out that older adults with AD particularly struggle in identifying negative emotions like sadness, fear, and anger (Moreira et al. 2021; Mccade et al. 2013), while the recognition of happiness and neutral expressions is less problematic.

It follows that emotional apathy in seniors with AD may substantially contribute to the production of infelicitous illocutionary forces (IFs) in their speech acts. Compared with cognitively healthy older adults, older adults with AD manifest a certain degree of emotional impairment, which may manifest as a reduction or absence of emotion, reduced spontaneous emotion, and a lack of emotional response to positive or negative stimuli. These factors lead to the inconsistency in the emotional state of cognitively impaired older adults when expressing harmful IFs with significant emotional tendency, resulting in infelicitous IFs. Analyses have indicated that, in contrast to cognitively healthy seniors, those with AD exhibit deficiencies in negative emotions when enacting harmful IFs, leading to instances of infelicity.

6.2 AD Older Adults Are Inconsistent in Their Emotions and Facial Expressions when Expressing IFs

The comparative analysis elucidates a paradoxical phenomenon among the older adults suffering from AD: despite their capacity to produce diverse facial expressions, they exhibit a notable degree of emotional apathy. This incongruence between affection and its outward manifestation is symptomatic of a divergence from the STFE-Match Assumption proposed by Gu (2013b). This principle asserts that a ‘whole person’, the agent of real-life discourse activities, has dynamic sounds, emotions, and gestures. If the prosody, facial expressions, movements and other features of external expressions can faithfully reflect the speaker’s inner thoughts and emotions, the speaker follows the STFE-match principle; otherwise, the speaker violates the principle. Deviations may arise from either deliberate rhetorical strategy or from pragmatic impairment. The latter is notably exemplified by the disconnect between emotional intent and its corresponding expressions elucidated in AD patients, who predominantly project a neutral emotion when engaging in harmful IF. This pragmatic decline therefore complicates the interpretation for interlocutors.

6.3 AD Older Adults Are Less Capable of Employing Resources Such as Gestures Compared with Cognitively Healthy Older Adults

Prior research has established that communication inherently incorporates multiple modalities, thereby rendering illocutionary forces (IFs) multimodal and IFIDs multidimensional. Indeed, the harmonious interplay of speech, gestures, and emotions is indispensable for expressing IFs and for recipients’ comprehension of speakers’ intent. It is rather common in clinical studies to examine the importance of non-verbal behaviours for communication. Some studies have shown that people with dementia can demonstrate verbal and gestural disorders associated with their semantic memory deficits. This is in accordance with our findings.

The above analysis shows that cognitively healthy older adults can better employ gestures in their speech. However, there is an observable decline in the use of multimodal features that typically associate with the four established classes of IFs. Conversely, AD patients tend to exhibit more frequent occurrence of non-normative features. Additionally, the quantitative study discloses that elderly individuals with AD utilize hand gestures less frequently, with a rate of 70.9 %, compared to the 73.5 % observed in their cognitively healthy peers. This manifests AD older adults’ deficit in employing bodily modes in communication. This is consonant with the literature, which documents that cognitively compromised individuals struggle to incorporate hand movements in their communication. They produce more ambiguous gestures, fewer metaphorical gestures than gestures referring to specific content, and fewer two-handed gestures expressing complex concepts (Glosser, Wiley, and Barnoski 1998).

Nonetheless, the communicative behavior of AD patients is not homogeneous. In fact, people with neurodegenerative diseases, including aphasia and AD, are known to ‘compensate’ in verbal communication (Perniss 2018). Hamilton (2008) examined the communication of older adults with dementia in terms of gestures, expressions and tones, and concluded that even those with severe dementia retained some capability to convey their pragmatic intents non-verbally, melding speech with prosody, facial expressions, and gestures.

6.4 AD Older Adults Demonstrate Insufficient Ability to Employ Prosody-Assisted Verbal Expression

The prosodic features of AD older adults are also different from cognitively healthy ones, mainly in low scale, high scale, falling tone, convex tune, stress, and pause, etc. A comparative analysis of the four classes of IFs in the two groups reveals that the prosodic features closely related to the corresponding IFs are less frequently observed in AD patients’ speech. For instance, in the harmful class, the speakers’ emotions are often negative, and are usually filled with helplessness, frustration, and grievance. Correspondingly, they shall speak faintly or at a low pitch. However, in the harmful class, moderate and low pitch only account for 49.5 % in AD older adults, which is much lower than the 73.5 % of cognitively healthy older adults. As mentioned, although even tones are the most common tonal pattern (87.4 %), they are less likely to reflect specific emotions; whereas falling tones, which do reflect negative emotions, are less dominant (43.7 %) in the harmful IFs of AD older adults. This corresponds to the emotional apathy of AD older adults, and reflects their deficiency to resort to prosodic resources.

7 Conclusions

All human interaction is multimodal in nature. Many linguistic theories or interaction rules could be enriched or even revised with the introduction of both corpus method and multimodal data. In multimodal corpus-based study on speech act, speaker/hearer is no longer just a rational meaning-maker based on traditional conceptualization of pragmatics, but a ‘whole man’ with emotions, which can be embodied in speech, prosody, and gestures.

The major findings previously discussed further extend the scope of Speech Act Theory and develop the concept of IFID by using the novel methodology and new linguistic data. Starting with the core concept of speech act, we quantitatively analysed the distinctive multimodal features exhibited by cognitively healthy seniors and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients when expressing harmful illocutionary force. It is found that individuals with AD often resorted to multimodal resources as compensation in pragmatic communication, but they displayed infelicity in illocutionary forces compared to the healthy counterparts, characterized by an incongruity between their emotions, facial expressions, and the intended illocutionary forces (IFs). Moreover, AD patients have shown a limited ability to use gestures effectively, often applying less powerful and atypical movements such as “head-down”; and they had difficulty utilizing proper intonation and other prosodic cues in communication. The infelicity observed in the illocutionary force of their speech acts indicates compromised pragmatic competence, which, in turn, serves as an indicator of their diminished cognitive functioning.

This research extends the application scope of multimodal pragmatics and contributes a novel perspective to clinical pragmatics, particularly concerning the specific populations like the older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Through this approach, the paper aims to enhance our understanding of pragmatic competence in the context of cognitive decline and its impact on communication. Prospectively, healthcare professionals may employ the multimodal analysis of speech acts as a primary metric for evaluating the pragmatic competence among the elderly.

Funding source: The Project of Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Shanghai “A Study of Pattern and Criteria of Age-Friendly Business Development”

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2023BSH011

Funding source: The Project of China Disabled Persons’ Federation “A Study of Semantic Disorder of Older Adults with Dementia in China”

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2023CDPFHS-04

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Project of Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Shanghai “A Study of Pattern and Criteria of Age-Friendly Business Development” (2023BSH011) and The Project of China Disabled Persons’ Federation “A Study of Semantic Disorder of Older Adults with Dementia in China” (2023CDPFHS-04).

| Illocutionary Force Indicating Devices (IFID) | Coding |

|---|---|

| performativity | performativity |

| positive primary emotion | P_PE |

| negative primary emotion | N_PE |

| no primary emotion | No_PE |

| positive other-directed social emotion | P_OD_SE |

| negative other-directed social emotion | N_OD_SE |

| neutral other-directed social emotion | Nu_OD_SE |

| positive self-directed social emotion | P_SD_SE |

| negative self-directed social emotion | N_SD_SE |

| neutral self-directed social emotion | Nu_SD_SE |

| positive background emotion | P_BE |

| negative background emotion | N_BE |

| neutral background emotion | Nu_BE |

| head movement | head_movement |

| lowering head | head_lowering |

| nodding head | head_nodding |

| raising head | head_raising |

| shaking head | head_shaking |

| turning head | head_turning |

| no eye contact | eye_no_contact |

| steady eye contact | eye_steady |

| unsteady occasional eye contact | eye_unsteady_occasional |

| positive expression | P_expression |

| negative expression | N_expression |

| Illocutionary Force Indicating Devices (IFID) | Coding |

|---|---|

| neutral expression | Nu_expression |

| hand movement | hand_movement |

| leaning forward | body_lean_forward |

| leaning back | body_lean_back |

| upright body | body_upright |

| low pitch | low_pitch |

| high pitch | high_pitch |

| middle pitch | middle_pitch |

| fast pace | fast_pace |

| middle pace | middle_pace |

| slow pace | slow_pace |

| falling tone | falling_tone |

| even tone | even_tone |

| rising tone | rising_tone |

| convex tune | convex_tune |

| concave tune | concave_tune |

| pause | pause |

| stress | stress |

| laughter | laughter |

Frequency and percentage of IFIDs in cognitively healthy older adults’ expression of harmful IFs.

| Illocutionary Force Indicating Devices (IFID) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Nu_expression (neutral expression) | 105 | 92.9 % |

| fast_pace | 97 | 85.8 % |

| even_tone | 92 | 81.4 % |

| stress | 91 | 80.5 % |

| body_upright | 89 | 78.8 % |

| low_pitch | 83 | 73.5 % |

| hand_movement | 83 | 73.5 % |

| N_PE (negative primary emotion) | 78 | 69.0 % |

| Nu_BE (neutral background emotion) | 74 | 65.5 % |

| middle_pitch | 74 | 65.5 % |

| eye_steady | 65 | 57.5 % |

| high_pitch | 62 | 54.9 % |

| falling_tone | 54 | 47.8 % |

| middle_pace | 53 | 46.9 % |

| pause | 51 | 45.1 % |

| N_SD_SE (negative self-directed social emotion) | 47 | 41.6 % |

| head_movement | 44 | 38.9 % |

| eye_unsteady_occasional | 41 | 36.3 % |

| Nu_SD_SE (neutral self-directed social emotion) | 33 | 29.2 % |

| N_OD_SE (negative other-directed social emotion) | 33 | 29.2 % |

| P_BE (positive background emotion) | 30 | 26.5 % |

| Nu_OD_SE (neutral other-directed social emotion) | 27 | 23.9 % |

| No_PE (no primary emotion) | 27 | 23.9 % |

| slow_pace | 22 | 19.5 % |

| body_lean_forward | 22 | 19.5 % |

| convex_tune | 20 | 17.7 % |

| P_OD_SE (positive other-directed social emotion) | 18 | 15.9 % |

| head_shaking | 15 | 13.3 % |

| head_nodding | 15 | 13.3 % |

| rising_tone | 12 | 10.6 % |

| body_lean_back | 12 | 10.6 % |

| head_lowering | 11 | 9.7 % |

| eye_no_contact | 11 | 9.7 % |

| head_turning | 10 | 8.8 % |

| P_PE (positive primary emotion) | 9 | 8.0 % |

| N_BE (negative background emotion) | 9 | 8.0 % |

| laughter | 9 | 8.0 % |

| head_raising | 8 | 7.1 % |

| concave_tune | 7 | 6.2 % |

| N_expression (negative expression) | 6 | 5.3 % |

| P_SD_SE (positive self-directed social emotion) | 5 | 4.4 % |

| P_expression (positive expression) | 2 | 1.8 % |

Frequency and percentage of IFIDs in AD older adults’ expression of harmful IFs.

| Illocutionary Force Indicating Devices (IFID) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| fast_pace | 98 | 95.1 % |

| even_tone | 90 | 87.4 % |

| Stress | 84 | 81.6 % |

| body_upright | 77 | 74.8 % |

| Nu_expression (neutral expression) | 74 | 71.8 % |

| hand_movement | 73 | 70.9 % |

| N_PE (negative primary emotion) | 70 | 68.0 % |

| middle_pitch | 60 | 58.3 % |

| Nu_BE (neutral background emotion) | 59 | 57.3 % |

| high_pitch | 54 | 52.4 % |

| head_movement | 51 | 49.5 % |

| low_pitch | 51 | 49.5 % |

| falling_tone | 45 | 43.7 % |

| eye_steady | 44 | 42.7 % |

| middle_pace | 42 | 40.8 % |

| N_SD_SE (negative self-directed social emotion) | 41 | 39.8 % |

| eye_unsteady_occasional | 39 | 37.9 % |

| Nu_SD_SE (neutral self-directed social emotion) | 37 | 35.9 % |

| P_BE (positive background emotion) | 37 | 35.9 % |

| Nu_OD_SE (neutral other-directed social emotion) | 36 | 35.0 % |

| pause | 27 | 26.2 % |

| No_PE (no primary emotion) | 25 | 24.3 % |

| rising_tone | 24 | 23.3 % |

| N_expression (negative expression) | 23 | 22.3 % |

| N_OD_SE (negative other-directed social emotion) | 22 | 21.4 % |

| body_lean_back | 20 | 19.4 % |

| eye_no_contact | 19 | 18.4 % |

| slow_pace | 18 | 17.5 % |

| head_turning | 17 | 16.5 % |

| head_raising | 16 | 15.5 % |

| head_nodding | 13 | 12.6 % |

| P_PE (positive primary emotion) | 12 | 11.7 % |

| P_OD_SE (positive other-directed social emotion) | 12 | 11.7 % |

| head_lowering | 12 | 11.7 % |

| convex_tune | 12 | 11.7 % |

| laughter | 12 | 11.7 % |

| head_shaking | 11 | 10.7 % |

| body_lean_forward | 8 | 7.8 % |

| N_BE (negative background emotion) | 7 | 6.8 % |

| concave_tune | 4 | 3.9 % |

| P_SD_SE (positive self-directed emotion) | 3 | 2.9 % |

| P_expression (positive expression) | 3 | 2.9 % |

References

Alba-Juez, Laura, and Tatiana Larina. 2018. “Language and Emotion: Discourse Pragmatic Perspectives.” Russian Journal of Linguistics 22: 9–37. https://doi.org/10.22363/2312-9182-2018-22-1-9-37.Search in Google Scholar

Asplund, K., L. Jansson, and A. Norberg. 1995. “Facial Expressions of Patients with Dementia: A Comparison of Two Methods of Interpretation.” International Psychogeriatrics 7 (4): 527–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610295002262.Search in Google Scholar

Austin, J. L. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. William James Lectures 1955. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cummings, Louise. 2009. Clinical Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Eggenberger, Noëmi, B. Preisig, R. Schumacher, Simone Hopfner, T. Vanbellingen, T. Nyffeler, K. Gutbrod, et al.. 2016. “Comprehension of Co-Speech Gestures in Aphasic Patients: An Eye Movement Study.” PLoS One 11: e0146583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146583.Search in Google Scholar

Filiou, Renee-Pier, Simona Maria Brambati, Maxime Lussier, and Nathalie Bier. 2024. “Speech Acts as a Window to the Difficulties in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living: A Qualitative Descriptive Study in Mild Neurocognitive Disorder and Healthy Aging.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 97 (4): 1777–92. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-230031.Search in Google Scholar

Geladó, Sandra, Isabel Gómez-Ruiz, and Faustino Diéguez-Vide. 2022. “Gestures Analysis during a Picture Description Task: Capacity to Discriminate between Healthy Controls, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease.” Journal of Neurolinguistics 61: 101038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2021.101038.Search in Google Scholar

Glosser, G., M. J. Wiley, and E. J. Barnoski. 1998. “Gestural Communication in Alzheimer’s Disease.” Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 20 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.20.1.1.1484.Search in Google Scholar

Goldie, Peter. 2002. “Emotions, Feelings and Intentionality.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 1 (3): 235–54.10.1023/A:1021306500055Search in Google Scholar

Gu, Yueguo. 2013a. “A Conceptual Model of Chinese Illocution, Emotion and Prosody.” In Human Language Resources and Linguistic Typology, 309–62. Taipei: Academia Sinica.Search in Google Scholar

Gu, Yueguo. 2013b. “The Study of STFE-Match Principle and Situated Discourse – Multimodal Corpus Linguistics Approach.” Contemporary Rhetoric 6: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.16027/j.cnki.cn31-2043/h.2013.06.002.Search in Google Scholar

Gu, Yueguo. 2017. “Intentionality, Consciousness, Intention, Purpose/Goal, and Speech Acts: From Philosophy of Mind to Philosophy of Language.” Contemporary Linguistics 19 (3): 317–47.Search in Google Scholar

Hamilton, Heidi. 2008. “Language and Dementia: Sociolinguistic Aspects.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 28: 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190508080069.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Lihe. 2017. “Speech Act Theory and Multimodal Analysis: The Logic in Multimodal (Corpus) Pragmatics.” Journal of Beijing International Studies University 39 (3): 12–30+133.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Lihe. 2018. A Multimodal Corpus-based Study of Illocutionary Force: An Exploration of Multimodal Pragmatics from a New Perspective. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Lihe. 2019. “Speech Act and Emotion Analyses in Multimodal Pragmatics and the Application in Geronto-Linguistics.” Contemporary Rhetoric 38 (6): 42–52. https://doi.org/10.16027/j.cnki.cn31-2043/h.2019.06.005.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Lihe. 2021a. “Toward Multimodal Corpus Pragmatics: Rationale, Case, and Agenda.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 36 (1): 101–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqz080.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Lihe. 2021b. Toward Multimodal Pragmatics: A Study of Illocutionary Force in Chinese Situated Discourse, 1st ed. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003251774-1Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Lihe, and Jingjing Yang. 2023. “Developing Multimodal Pragmatics: Perspectives and Methods.” Contemporary Rhetoric 42 (6): 84–93. https://doi.org/10.16027/j.cnki.cn31-2043/h.2023.06.007.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Lihe, and Yiran Che. 2023. “Pragmatic Impairment and Multimodal Compensation in Older Adults with Dementia.” Language and Health 1: 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.laheal.2023.06.004.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Lihe, Jingjing Yang, and Zhuoya Liu. 2021. “Pragmatic Compensation for the Elders with Cognitive Impairment: A Speech Act Perspective.” Chinese Journal of Language Policy and Planning 6 (6): 33–44, https://doi.org/10.19689/j.cnki.cn10-1361/h.20210603.Search in Google Scholar

Johar, Swati. 2016. “Emotion, Affect and Personality in Speech.” In SpringerBriefs in Electrical and Computer Engineering. Cham: Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-319-28047-9Search in Google Scholar

Kasper, Gabriele. 2006. “Speech Acts in Interaction: Towards Discursive Pragmatics.” Pragmatics and Language Learning 11: 281–314.Search in Google Scholar

Knight, Dawn. 2009. “A Multi-Modal Corpus Approach to the Analysis of Backchanneling Behaviour.” Doctoral diss., University of Nottingham.Search in Google Scholar

Knight, Dawn, and Svenja Adolphs. 2008. “Multi-Modal Corpus Pragmatics: The Case of Active Listenership.” In Pragmatics and Corpus Linguistics: A Mutualistic Entente, 175–90. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110199024.175Search in Google Scholar

Magai, Carol, Carl Cohen, David Gomberg, C Malatesta, and C Culver. 1996. “Emotional Expression during Mid- to Late-Stage Dementia.” International Psychogeriatrics 8 (3): 383–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161029600275X.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, Jean-Claude, and Laurence Devillers. 2009. “A Multimodal Corpus Approach for the Study of Spontaneous Emotions.” In Affective Information Processing, 267–91. London: Springer.10.1007/978-1-84800-306-4_15Search in Google Scholar

Mccade, Donna, Greg Savage, Adam Guastella, Simon Lewis, and Sharon Naismith. 2013. “Emotion Recognition Deficits Exist in Mild Cognitive Impairment, but Only in the Amnestic Subtype.” Psychology and Aging 28: 840–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033077.Search in Google Scholar

Moreira, Helena, Ana Costa, Alvaro Machado, São Castro, Selene Vicente, and César Lima. 2021. “Impaired Recognition of Facial and Vocal Emotions in Mild Cognitive Impairment.” Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 28: 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135561772100014X.Search in Google Scholar

Perkins, Mick. 2007. “Pragmatic Theory and Pragmatic Impairment.” In Pragmatic Impairment, 8–32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486555.003Search in Google Scholar

Perniss, Pamela. 2018. “Why We Should Study Multimodal Language.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1109. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01109.Search in Google Scholar

Searle, John R. 1969. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139173438Search in Google Scholar

Searle, John R. 1979. Expression and Meaning: Studies in the Theory of Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511609213Search in Google Scholar

Simmons-Mackie, Nina, and Roxanne Stoehr. 2016. “Advancing Social Solidarity: Preference Organization in the Discourse of Speech-Language Pathology.” Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders 7 (2): 243–63. https://doi.org/10.1558/jircd.v7i2.29963.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Jiemin, and Hongda Zhu. 2001. HANYU JIELU XUE. Language and Culture. Press.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Lixia. 2014. Study of Sentential Accent in Chinese Discourse from the Perspective of Pragmatics. Guangzhou: World Publishing Corporation.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Xueqing, Lihui Cheng, Yulei Song, XU Guihua, and Yamei Bai. 2020. “Application Status Quo of Emotion Recognition Technology in Mild Cognitive Impairment.” Chinese Nursing Research 34 (10): 1750–3.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, Qing-Fei, Lan Tan, Hui-Fu Wang, Teng Jiang, Meng-Shan Tan, Lin Tan, Wei Xu, et al.. 2016. “The Prevalence of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Affective Disorders 190: 264–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069.Search in Google Scholar

Zhou, Deyu, and Lihe Huang. 2023. “Performance and Mechanism of Multimodal Compensation in Pragmatic Impairment.” 现代外语 46: 15–28. https://doi.org/10.20071/j.cnki.xdwy.2023.01.010.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Shanghai International Studies University

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Medicines as Subjects: A Corpus-Based Study of Subjectification in Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Policy

- Adjusting Mood in Mandarin Chinese: A Game Theory Approach to Double and Redundant Negation with Entropy

- Charting the Trajectory of Corpus Translation Studies: Exploring Future Avenues for Advancement

- Exploring Harmful Illocutionary Forces Expressed by Older Adults with and Without Alzheimer’s Disease: A Multimodal Perspective

- Categorizing and Quantifying Doctors’ Extended Answers and their Strategies in Teleconsultations: A Corpus-based Study

- Gunmen, Bandits and Ransom Demanders: A Corpus-Assisted Critical Discourse Study of the Construction of Abduction in the Nigerian Press

- Three Faces of Heroism: An Empirical Study of Indirect Literary Translation Between Chinese-English-Portuguese of Wuxia Fiction

- From Traditional Narratives to Literary Innovation: A Quantitative Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s Stylistic Evolution

- Book Reviews

- A Corpus-Based Analysis of Discourses on the Belt and Road Initiative: Corpora and the Belt and Road Initiative

- A Sourcebook in Classical Confucian Philosophy

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Medicines as Subjects: A Corpus-Based Study of Subjectification in Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Policy

- Adjusting Mood in Mandarin Chinese: A Game Theory Approach to Double and Redundant Negation with Entropy

- Charting the Trajectory of Corpus Translation Studies: Exploring Future Avenues for Advancement

- Exploring Harmful Illocutionary Forces Expressed by Older Adults with and Without Alzheimer’s Disease: A Multimodal Perspective

- Categorizing and Quantifying Doctors’ Extended Answers and their Strategies in Teleconsultations: A Corpus-based Study

- Gunmen, Bandits and Ransom Demanders: A Corpus-Assisted Critical Discourse Study of the Construction of Abduction in the Nigerian Press

- Three Faces of Heroism: An Empirical Study of Indirect Literary Translation Between Chinese-English-Portuguese of Wuxia Fiction

- From Traditional Narratives to Literary Innovation: A Quantitative Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s Stylistic Evolution

- Book Reviews

- A Corpus-Based Analysis of Discourses on the Belt and Road Initiative: Corpora and the Belt and Road Initiative

- A Sourcebook in Classical Confucian Philosophy