Vein of Galen aneurysm that was diagnosed prenatally and supracardiac obstructed total anomalous pulmonary venous return with pulmonary hypertension: case report

Abstract

The vein of Galen aneurysm is the most common form of symptomatic cerebrovascular malformation in neonates and infants. This anomaly may be diagnosed prenatally by several imaging modalities and causes high cardiac output, which may lead to cardiac failure, in newborns. Total anomalous pulmonary venous return is a rare entity that makes up approximately 0.4%–2% of all congenital heart diseases. The most common type of total anomalous pulmonary venous return is the supracardiac type. The pulmonary veins drain to a confluence posterior to the heart and then to a vertical vein, most commonly on the left, which enters the innominate vein and the drains to the right atrium. Obstructed pulmonary veins with supracardiac-type total anomalous pulmonary venous return can cause severe cardiac and respiratory failure. In this article, a case of a neonate with a vein of Galen aneurysm diagnosed prenatally by magnetic resonance imaging, and a supracardiac obstructed type of total anomalous pulmonary venous return with pulmonary hypertension is presented.

Introduction

A vein of Galen aneurysm is a rare disease that has an incidence of <1% of all cerebral vascular malformations and can involve different cerebral arteriovenous malformations associated with dilatation of the vein of Galen. Vein of Galen aneurysm is estimated to be seen in only 2.5 out of 100,000 live births [1]. It is characterized by saccular dilatation of the vein of Galen, pooling blood shunted directly from abnormally enlarged cerebral arteries and often causes congestive heart failure. Its prognosis depends on the patient’s age when the manifestation occurs and on the size of the aneurysm. Two major factors affect the prognosis of a vein of Galen aneurysm: (a) the severity of congestive heart failure, which depends on the volume of arteriovenous shunting, and (b) brain injury. Vein of Galen aneurysm causes high mortality and morbidity in neonates [1].

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return is a rare entity that makes up approximately 0.4%–2% of all congenital heart diseases and can be categorized according to the site of drainage into the systemic circulation (supracardiac 45%, infracardiac 25%, cardiac 25%, and mixed 5%) [4]. The most common type of total anomalous pulmonary venous return is the supracardiac type. The pulmonary veins drain to a confluence posterior to the heart and then to a vertical vein, most commonly on the left, which enters the innominate vein and then drains to the right atrium. The left heart receives oxygenated blood through a patent foramen ovale. The clinical presentation differs, depending on whether the pulmonary venous drainage is unobstructed (cardiac failure, mild cyanosis) or obstructed (respiratory failure, severe cardiac failure) [5]. Children with obstructed total anomalous pulmonary venous return present with more respiratory issues, hypoxia, and even low cardiac output, as well as pulmonary artery hypertension. Occasionally, infants with obstructed total anomalous pulmonary venous return are referred for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation caused by respiratory failure or pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary hypertension can cause death at the 1st week of neonatal life [2].

We report the case of a neonate with Galen aneurysm diagnosed prenatally by magnetic resonance imaging, and a supracardiac obstructed type of total anomalous pulmonary venous return. The neonate died of pulmonary hypertension, and congestive heart and respiratory failure.

Case report

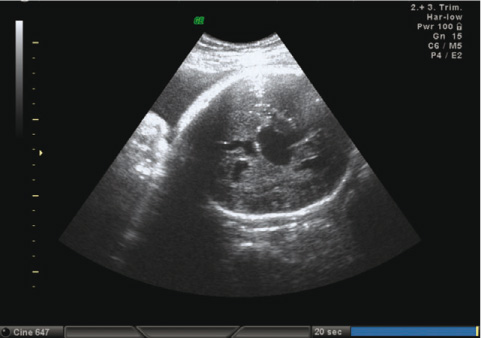

A Vein of Galen aneurysm was detected by color Doppler ultrasonography in the fetus of a 26-year-old woman at 35 weeks’ gestation (Figures 1 and 2). There was no other cardiac anomaly (tricuspid regurgitation, etc.) or cardiomegaly, and the ductus venosus was normal on prenatal echocardiography. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging was performed at 36 weeks’ gestation. It showed a grossly dilated vein of Galen with prominent choroidal arteries as supplying vessels and a significant dilatation of the straight sinus, the confluence of sinuses, and the transverse sinuses (Figures 3 and 4).

Vein of Galen aneurysm at color Doppler ultrasonography.

Blood flow at aneurysm.

Fetus at magnetic resonance imaging.

Dilated vein of Galen and sinuses at fetal magnetic resonance imaging.

The mature male neonate was delivered by elective cesarean section at 37 weeks’ gestation. His Apgar scores were 5 at 1 min and 7 at 5 min. The neonate was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit because of respiratory distress. His birth weight was 3400 g (50th–75th percentile), height was 50 cm (50th percentile), head circumference was 35 cm (25th–50th percentile), pulse rate was 145/min, respiratory rate was 70/min, arterial blood pressure was 69/45 mm Hg, and arterial oxygen saturation was 93%. There was 3/6 systolic murmur on cardiac auscultation; respiratory auscultation was normal and a mild hepatomegaly was present. The pH was 7.29, pO2 was 45 mm Hg, pCO2 was 56.5 mm Hg, and HCO3 was 26.6 on arterial blood gas test. Hemoglobin was 19.7 g/dL, hematocrit was 54.6%, white blood cell was 36,900/mm3, and platelet was 109,000/mm3 at complete blood count. Urea, creatinine, liver function tests, and electrolytes were normal.

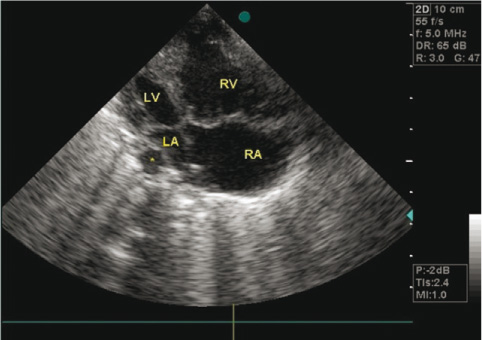

Cardiomegaly was detected on chest roentgenography (Figure 5). Electrocardiography demonstrated right ventricle hypertrophy (Figure 6). Dilated right-sided heart structures (right atrium, right ventricle, pulmonary artery), a small left atrium, and an echo-free space behind the left atrium were observed on echocardiography. Also, the right upper pulmonary veins drained to the coronary sinus. The pulmonary veins were obstructed, and the infant presented with patent ductus arteriosus with pulmonary hypertension. The pulmonary veins drained to the left vertical vein, which drained to the coronary sinus and to the right atrium. All of these findings are diagnostic of the supracardiac and obstructed type of total anomalous pulmonary venous return (Figures 7–10).

Cardiomegaly on chest roentgenography.

Right ventricle hypertrophy on electrocardiography.

Dilated right-sided heart structures, a small left atrium, and an echo-free space behind the left atrium on echocardiography.

Atriums, ventricules and space behind left atrium on echocardiography.

Pulmonary veins drained to the left vertical vein, which drained to the coronary sinus and to the right atrium (magnetic resonance imaging angiography).

Supracardiac and obstructed type of total anomalous pulmonary venous return at magnetic resonance imaging angiography.

Dopamine, digoxin, and furosemid were initiated for congestive heart failure, and sildenafil was started for pulmonary hypertension. Severe cardiac and respiratory failure occurred in the neonate. The cardiopulmonary failure progressed, and resistance to treatment occurred. Surgical treatment to repair the total anomalous pulmonary venous return and endovascular embolization of the vein of Galen aneurysm could not be performed because of the severe cardiopulmonary failure. The neonate died on the 9th day of treatment.

Discussion

Cerebrovascular malformations are rarely diagnosed in fetuses. The most common of these malformations is a vein of Galen aneurysm. In most cases, it represents an anomaly of choroidal arteries that drain into the vein of Galen. Vein of Galen aneurysm causes high cardiac output, which may lead to heart failure. Cardiac failure associated with a vein of Galen aneurysm depends on the volume of arteriovenous shunting, and thus is more severe than cardiac failure associated with congenital cardiac diseases. The treatment and management of this type of cardiac failure is difficult [3]. In our case, the neonate had a vein of Galen aneurysm and we believe that cardiac failure associated with the vein of Galen aneurysm occurred during the intrauterine life because cardiomegaly was detected on prenatal magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography. There was no other cardiac anomaly (tricuspid regurgitation, etc.) or cardiomegaly, and the ductus venosus was normal on prenatal echocardiography. We diagnosed total anomalous pulmonary venous return with pulmonary hypertension according to postnatal echocardiography results; thus, the cardiac failure was very severe.

Fetal echocardiography should be performed by specialists who are familiar with prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart diseases. In addition to information provided by the basic screening examination, a detailed analysis of cardiac structure and function may further characterize the visceroatrial situs, systemic and pulmonary venous connections, foramen ovale mechanism, atrioventricular connections, ventriculoarterial connections, great vessel relationships, and sagittal views of the aortic and ductal arches. Some lesions are not discovered until later in pregnancy, and specific types of abnormalities (e.g., transposition of the great arteries, total anomalous pulmonary venous return, or aortic coarctation) may not be evident from this scanning plane alone. Thus, we were not able to diagnose the total anomalous pulmonary venous return on prenatal echocardiography.

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return is a rare congenital cardiac disease that constitutes approximately 0.4%–2% of all congenital heart diseases. Abnormal development of the pulmonary veins may result in either partial or complete anomalous drainage into the systemic venous circulation. The diagnosis of total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage is made when all four pulmonary veins drain anomalously to the right atrium or to a tributary of the systemic veins. The supracardiac type accounts for roughly 45% of the total anomalous pulmonary venous returns in children. In this type, the pulmonary vein drains to a confluence posterior to the heart and then to a vertical vein, most commonly on the left, which enters the innominate vein and then drains to the right atrium. The clinical presentation differs depending on whether the pulmonary venous drainage is unobstructed (cardiac failure, mild cyanosis) or obstructed (respiratory failure, severe cardiac failure) [2, 5]. In our case, the pulmonary veins drained to the left vertical vein, which drained to the coronary sinus and then to the right atrium, and were obstructed. A supracardiac and obstructed type of total anomalous pulmonary venous return was thus diagnosed. Severe cardiac and respiratory failure occurred in our case because of obstructed pulmonary veins.

Cardiac failure with a vein of Galen aneurysm is rare in the intrauterine period because of the low resistance of the placenta. More than 70% of cardiac flow goes to cerebral circulation at birth, and cardiac failure occurs. Most cases show cardiac failure in the neonatal life [3, 4]. In our case, cardiomegaly was determined prenatally by magnetic resonance imaging. The supracardiac obstructed type of total anomalous pulmonary venous return and pulmonary hypertension were determined after birth. We believe that cardiac failure associated with the vein of Galen aneurysm occurred during the intrauterine life because cardiomegaly was detected on prenatal magnetic resonance imaging. The cardiac failure progressed postnatally because of supracardiac obstructed total anomalous pulmonary venous return and pulmonary hypertension.

A vein of Galen aneurysm with cardiac failure complicated by total anomalous pulmonary venous return with pulmonary hypertension must be treated postnatally to prevent infant death.

References

[1] Ciricillo SF, Edwards MS, Schmidt KG, Hieshima GB, Silverman NH, Higashida RT, et al. Interventional neuroradiological management of vein of Galen malformations in the neonate. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:22–8.10.1227/00006123-199007000-00003Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ertuğrul T, Tanman B, Cantez T, Ömeroğlu R, Dindar A, Aydoğan Ü. Kalp ve damar hastalıkları. In: Neyzi O, Ertuğrul T, editors. Pediatri. İstanbul: Nobel Tıp Kitabevleri; 2002. p. 918–1009.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Frawley GP, Dargaville PA, Mitchell PJ, Tress BM, Loughnan P. Clinical course and medical management of neonates with severe cardiac failure related to vein of Galen malformation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;87:F144–9.10.1136/fn.87.2.F144Search in Google Scholar

[4] Geva T, Van Praagh S. Anomalies of the pulmonary veins. In: Allen HD, Driscoll DJ, Shaddy RE, editors. Moss and Adams’ heart disease in infants, children and adolescents: including the fetus and young adults. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. p. 761–92.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Launer RM, Driscoll DJ, Sanders SP, Cohen MS, Wolfe RR. Cardiology. In: Frinberg L, editor. Saunders manual of pediatric practice. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 1998. p. 532–617.Search in Google Scholar

-

The authors stated that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

©2012 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Case reports – Obstetrics

- Sonographic presentations of uterine rupture following vaginal birth after cesarean – report of two cases 12 h apart

- Prenatal diagnosis of thrombocytopenia-absent radius syndrome

- Cervico-isthmic pregnancy with cervical placenta accreta

- Prelabor uterine rupture and extrusion of fetus with intact amniotic membranes: a case report

- Hyperreactio luteinalis in a spontaneously conceived pregnancy associated with polycystic ovarian syndrome and high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin

- Should clinicians advise terminating a pregnancy following the diagnosis of a serious fetal cardiac abnormality?

- Absence of hemolytic disease of fetus and newborn (HDFN) in a pregnancy with anti-Yka (York) red cell antibody

- Congenital midgut malrotation causing intestinal obstruction in midpregnancy managed by prolonged total parenteral nutrition: case report and review of the literature

- Skin popping scars – a telltale sign of past and present subcutaneous drug abuse

- Botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia in pregnancy

- Thrombotic stroke in association with ovarian hyperstimulation and early pregnancy rescued by thrombectomy

- Normal pregnancy outcome in a woman with chronic myeloid leukemia and epilepsy: a case report and review of the literature

- Three-dimensional power Doppler assessment of pelvic structures after unilateral uterine artery embolization for postpartum hemorrhage

- Deep congenital hemangioma: prenatal diagnosis and follow-up

- Case reports – Fetus

- Diagnosis of cleft lip-palate during nuchal translucency screening – case report and review of the literature

- Vein of Galen aneurysm that was diagnosed prenatally and supracardiac obstructed total anomalous pulmonary venous return with pulmonary hypertension: case report

- A fetus with 19q13.11 microdeletion presenting with intrauterine growth restriction and multiple cystic kidneya

- Prenatal detection of periventricular pseudocysts by ultrasound: diagnosis and outcome

- Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and limb ischemia: a case report

- Prenatal surgery in a triplet pregnancy complicated by a double twin reversed arterial perfusion (TRAP) sequence

- A case of a four-vessel umbilical cord: don’t stop counting at three!

- Case reports – Newborn

- Supratentorial hemorrhage suggested on susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in an infant with hydranencephaly

- Differential diagnosis of pseudotrisomy 13 syndrome

- Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome: a spectrum of presentations

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Case reports – Obstetrics

- Sonographic presentations of uterine rupture following vaginal birth after cesarean – report of two cases 12 h apart

- Prenatal diagnosis of thrombocytopenia-absent radius syndrome

- Cervico-isthmic pregnancy with cervical placenta accreta

- Prelabor uterine rupture and extrusion of fetus with intact amniotic membranes: a case report

- Hyperreactio luteinalis in a spontaneously conceived pregnancy associated with polycystic ovarian syndrome and high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin

- Should clinicians advise terminating a pregnancy following the diagnosis of a serious fetal cardiac abnormality?

- Absence of hemolytic disease of fetus and newborn (HDFN) in a pregnancy with anti-Yka (York) red cell antibody

- Congenital midgut malrotation causing intestinal obstruction in midpregnancy managed by prolonged total parenteral nutrition: case report and review of the literature

- Skin popping scars – a telltale sign of past and present subcutaneous drug abuse

- Botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia in pregnancy

- Thrombotic stroke in association with ovarian hyperstimulation and early pregnancy rescued by thrombectomy

- Normal pregnancy outcome in a woman with chronic myeloid leukemia and epilepsy: a case report and review of the literature

- Three-dimensional power Doppler assessment of pelvic structures after unilateral uterine artery embolization for postpartum hemorrhage

- Deep congenital hemangioma: prenatal diagnosis and follow-up

- Case reports – Fetus

- Diagnosis of cleft lip-palate during nuchal translucency screening – case report and review of the literature

- Vein of Galen aneurysm that was diagnosed prenatally and supracardiac obstructed total anomalous pulmonary venous return with pulmonary hypertension: case report

- A fetus with 19q13.11 microdeletion presenting with intrauterine growth restriction and multiple cystic kidneya

- Prenatal detection of periventricular pseudocysts by ultrasound: diagnosis and outcome

- Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and limb ischemia: a case report

- Prenatal surgery in a triplet pregnancy complicated by a double twin reversed arterial perfusion (TRAP) sequence

- A case of a four-vessel umbilical cord: don’t stop counting at three!

- Case reports – Newborn

- Supratentorial hemorrhage suggested on susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in an infant with hydranencephaly

- Differential diagnosis of pseudotrisomy 13 syndrome

- Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome: a spectrum of presentations