Abstract

Introduction

The increasing use of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (t-mAbs) has improved cancer and autoimmune disorder treatment. These therapeutics can interfere with serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation (IF), potentially leading to the appearance of monoclonal bands that may be misinterpreted as monoclonal gammopathies. Identifying the migration patterns and detection thresholds of t-mAbs is crucial to avoid misinterpretation in clinical laboratories.

Content

A systematic review following PRISMA guidelines was conducted using Pubmed and ScienceDirect databases, with algorithm-based searches and double-blind article selection. Data on the matrix used, separation methods and type of interference were collected into an extraction table.

Summary

A total of 30 articles were included and 30 t-mAbs were described. 11 t-mAbs migrated at the end of the gamma region, 12 in the mid-gamma region, 5 in the early gamma region, one in the beta-2 globulin region and one in the alpha-2 globulin region. Most t-mAbs were detectable by SPEP and IF at concentrations above 100 mg/L.

Outlook

Caution is needed when a new peak appears on SPEP, as it may be mistaken for a monoclonal spike leading to misdiagnosis. Therefore, understanding the migration profiles of these t-mAbs is essential. Different methods are available to remove t-mAbs interference and could be used in daily practice.

Introduction

Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation (IF) are standard biochemical investigations widely performed in daily practice. The main indication remains the diagnosis and monitoring of monoclonal gammopathies [1], 2]. The others indications for SPEP are exploration of acute or chronic inflammatory syndromes, detection of a humoral deficiency, exploration of chronic liver disease, nephrotic syndrome or peripheral neuropathy [3]. Indeed, these two techniques are complementary: SPEP enables monoclonal spike quantification whereas IF is used to determine the isotype of the monoclonal immunoglobulin. During follow-up, IF allows the detection of lower residual levels of monoclonal immunoglobulins, because of its greater sensitivity than SPEP. The lower detection limits of SPEP and IF are variable depending on the polyclonal background, migration area of the monoclonal protein, and gating method, generally ranging between approximately 100 and 1,000 mg/L [4], [5]. Monoclonal gammopathies are common in the general population, which explains the large number of biological tests performed to manage them. They form a heterogeneous group of diseases. Half of them are defined as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) [6]. The prevalence of MGUS is estimated at 3.2 % of people over 50 years, increasing to 5.3 % in those over 70 years and 7.5 % in those over 85 years [7]. The most studied remains the multiple myeloma (MM), which accounts for approximately 16.5 % of all monoclonal gammopathies [6]. Unlike MGUS, which are asymptomatic, MM is characterized by the presence of CRAB criteria (i.e. lytic bone lesions, hypercalcaemia, renal insufficiency, anaemia) and a proportion of plasma cells in bone marrow ≥10 %. In addition, the SLiM-CRAB criteria were added as recognized myeloma defining events: 60 % clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow; serum involved/uninvolved free light chain (FLC) ratio ≥100; MRI with the presence of more than one focal lesion [1]. In daily practice, monoclonal gammopathies represent the main indications of SPEP and IF.

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (t-mAbs) are now commonly used in the treatment of various diseases and are playing an increasingly important role in the therapeutic landscape. They are mainly used in haematology for the treatment of MM (e.g. daratumumab, isatuximab) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (e.g. rituximab). Anti-CD38 t-mAbs such as daratumumab or isatuximab can be used in association as a first-line treatment for patients with MM [8]. Different t-mAbs are often used in oncology as inhibitors of immune checkpoints (e.g. pembrolizumab and nivolumab) [9], [10]. Anti-TNF t-mAbs are used in the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn’s disease (e.g. infliximab or adalimumab) [11]. T-mAbs can also be used in nephrology for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria or hemolytic uremic syndrome (e.g. eculizumab) [9] or in neurology for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (e.g. ocrelizumab) [12]. More recently, anti-SARS-CoV-2 t-mAbs have received FDA approval as a treatment of COVID-19 [13].

T-mAbs are immunoglobulins (Ig), usually IgGκ, whose migration can be visualized using electrophoretic methods. Moreover, they usually have a long half-life that can increase with repeated administrations, which may lead to prolonged interference. Patients with autoimmune disease in particular may be treated for a long time with t-mAbs. Circulating t-mAbs concentrations are sometimes above the detection limit of SPEP and IF, allowing them to be detected. Therefore, they may be responsible for the presence of a small monoclonal spike that can be misinterpreted as a monoclonal gammopathy. This can lead to unnecessary, costly and sometimes invasive, stressful additional procedures, such as bone marrow aspirate and/or bone marrow biopsy. Electrophoretic migration of t-mAbs may also interfere with treatment monitoring and the classification of therapeutic response in MM. For example, migration of t-mAbs may be mistaken for that of the endogenous monoclonal gammopathy or the emergence of a new monoclonal spike. This could lead to misinterpretation of a complete response, which requires both a negative SPEP and IF.

Accurate interpretation of SPEP and IF is crucial, and the potential interference from t-mAbs must be considered with caution. Given the diversity of the available t-mAbs, a thorough knowledge of their potential interferences is important for the interpretation of SPEP and IF. The objective of this systematic review is to identify t-mAbs interferences on SPEP and IF, to identify their electrophoretic migration zones and to establish the serum concentrations at which they become detectable.

Methods

We performed a systematic review following the PRISMA guidelines [14]. The research had 3 components: t-mAbs, interference and laboratory techniques (SPEP and IF). Variations in spelling and plurals were taken into account. We carried out a PubMed and a ScienceDirect algorithm using predefined keywords. Mesh Terms were selected using HeTOP™ software. The following algorithm was used for the search the Pubmed database ((“electrophoresis” [MeSH Terms] OR “electrophores*” [Title/Abstract] OR “immunofixation” [Title/Abstract])) AND ((“interference*” [Title/Abstract] OR (“false positi*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“false-positi*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (false positive reactions [MeSH Terms]))) AND ((“antibodies, monoclonal” [MeSH Terms] OR “monoclonal antibod*” [Title/Abstract])). ScienceDirect algorithm was as follows (electrophoresis OR “capillary electrophoresis” OR immunoelectrophoresis OR immunofixation) AND (“monoclonal antibodies” OR “monoclonal antibody”) AND (interference OR interferences). The article search started on February 4th, 2024 and was limited between January 1st, 2000 and May 30th, 2025.

The search included publications describing the migration profile of one or more t-mAbs on SPEP or IF. Only articles in English and French languages were included. All types of articles were considered, including original articles, reviews, letters, clinical cases and case series. Moreover, t-mAbs described in this search had to be used in human medicine. Articles only focused on interference removal methods were excluded. The references of the selected articles were also analyzed to include additional articles relevant to the work that were not selected by the algorithm. The selection process of the articles shortlisted by the algorithm was carried out using Rayyan.ai™ platform. After automatic duplicate elimination, articles were screened through titles and then by abstract. To do this, the articles were first sorted in a double-blind process (SP and JBO). Discrepancies in article selection were resolved by a third person (LF). Final inclusion was checked by reading the full article.

The following data were collected in a reading grid: title, DOI, first author, publication date, journal, article type, main objectives, cases included, matrix used, separation method, interference (yes or no), tested t-mAbs (International Nonproprietary Name, indication and target, in vitro concentration, therapeutic concentration, half-life, electrophoretic migration zone) and method to remove interference. The presence of t-mAbs interference on SPEP and IF has been described. A focus was made on the methodology used in the articles (i.e. serum spiked with t-mAbs and/or use of patient’s sera).

Results

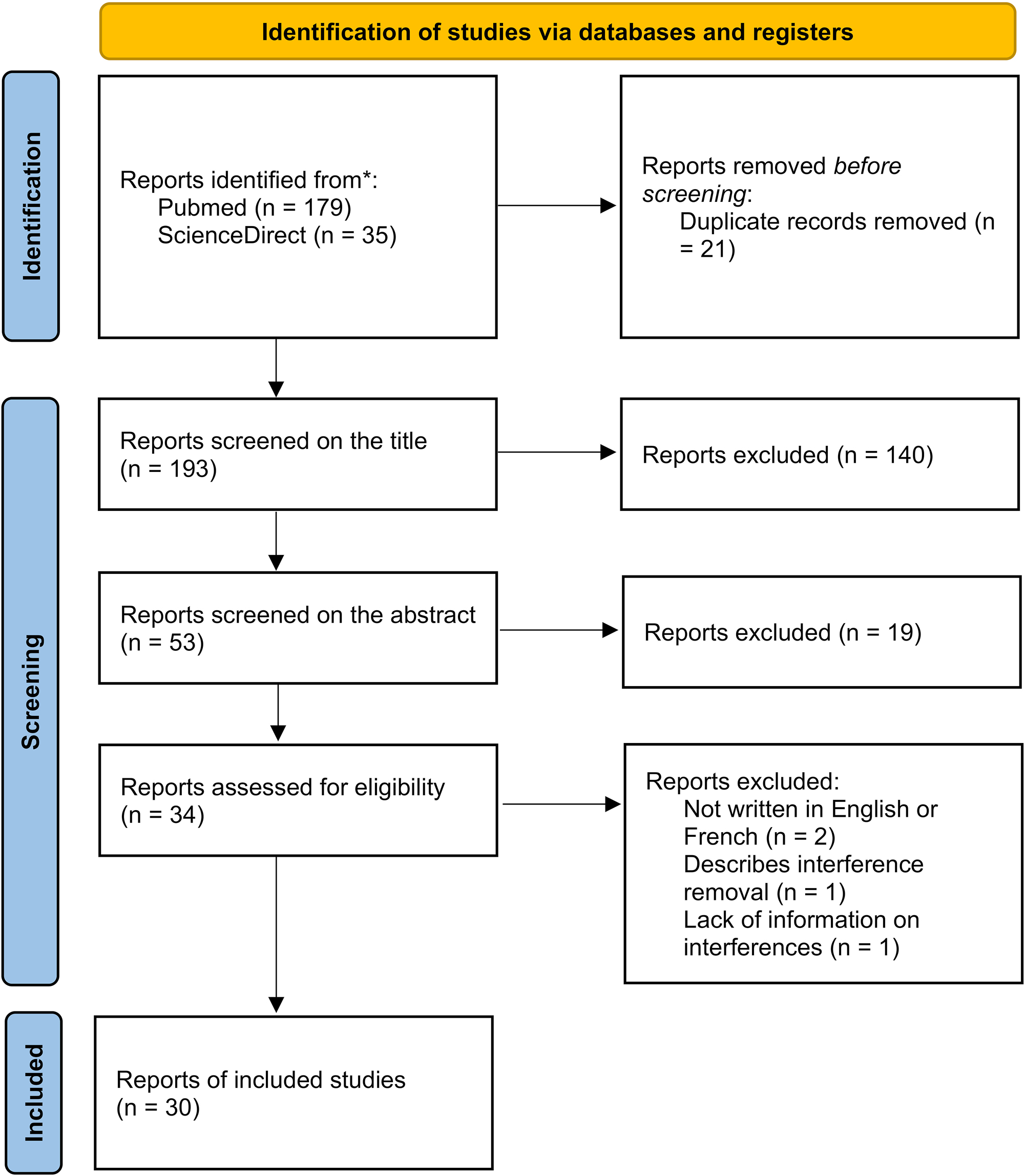

Figure 1 described the article selection process. 193 articles were initially selected from the databases using the selection algorithms. Finally, 34 papers were examined as full-text, and 4 of them were excluded due to the exclusion criteria. Overall, 30 articles were included in this systematic review.

Flowchart of the study selection and inclusion process.

T-mAbs were tested by electrophoresis on Sebia Capillarys™ or Helena Laboratories™ SPIFE, and by immunofixation on Sebia Hydrasys™ or Helena Laboratories™ SPIFE.

A total of 30 t-mAbs were identified across the selected literature (Table 1). Daratumumab, primarily indicated for the treatment of MM, was the most frequently reported, appearing in 12 of the 30 selected articles (∼40 %). Rituximab was also commonly reported, being mentioned in 8 articles (∼27 %). Most studies investigated multiple t-mAbs simultaneously. For example, all articles including infliximab also reported data on rituximab.

Interference of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies on electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation (IF).

| Monoclonal Ig | Isotype | Target | Max serum concentration, mg/L | Method of evaluation | Migration zone | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPEP | IF | ||||||

| Abatacept | Fusion protein | Anti-CD80, CD86 | 290a | Spiked serum (25 mg/L) [15] | Ø | Ø | [15] |

| Diluted in saline solution (1,000 mg/L) [15] | A | NA | [15] | ||||

| Adalimumab | IgGκ | Anti-TNFα | 100 [11] Cthrough=5a |

Spiked serum (100 mg/L) [11] | Ø | Ø | [11] |

| Patient serum (36 mg/L) [11] (NI) [16] | Ø | Ø | [11], [16] | ||||

| Diluted in saline solution (100 mg/L) [17] (NI) [18] | NA | D | [17], [18] | ||||

| Bamlanivimab | IgGκ | Anti-Sars-Cov2 | 187 [19] 196a |

Spiked serum (200 mg/L) [19] | E | E | [19] |

| Belantamab mafodotin | IgGκ | Anti-BCMA | 42 [20] 43a |

Spiked serum (1,000 mg/L) [20] | D | D | [20] |

| Patient serum (NI) [20] | Ø | Ø | [20] | ||||

| Bevacizumab | IgGκ | Anti-VEGF | 123 [21] | Spiked serum (200 mg/L) [15] | D | D | [15] |

| Diluted in saline solution (1,000 mg/L) [15] | D | NA | [15] | ||||

| Diluted in saline solution (200 mg/L) [17] (NI) [18] | NA | D | [17], [18] | ||||

| Casirivimab | IgGκ | Anti-Sars-Cov2 | 192 [19] 182.7a |

Spiked serum (200 mg/L) [19] | C | C | [19] |

| Patient serum (NI) [19] | Ø | Ø | [19] | ||||

| Cetuximab | IgGκ | Anti-EGFR | 160 [9] 185a |

Diluted in saline solution (200 mg/L) [17] (NI) [9], [18] | NA | D | [9], [17], [18] |

| Cilgavimab | IgGκ | Anti-Sars-Cov2 | 15.3 [22] 26.9a |

Spiked serum (153 mg/L in hypogammaglobulinemia) [22] | D | D | [22] |

| Patient serum (NI) [23] | D | D | [23] | ||||

| Daratumumab | IgGκ | Anti-CD38 | 910 [9] 993 [24] 915a |

Spiked serum (900 mg/L) [25] (250 mg/L) [9], [26] (707 mg/L) [24] | E | E | [9], [24], [25], [26] |

| Patient serum (mean=1,100 mg/L) [27] (NI) [9], [25], [26], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33] | E | E | [9], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33] | ||||

| Patient serum (NI) [10] | NA | E | [10] | ||||

| Denosumab | IgGκ | Anti-RANK | 6a | Spiked serum (1,000 mg/L) [20] | E | E | [20] |

| Patient serum (NI) [20], [34] | NA | E | [34] | ||||

| Ø | Ø | [20] | |||||

| Eculizumab | IgGκ | Anti-C5 | 100 [9] 200 [11] |

Spiked serum (200 mg/L) [9], [11] | Ø | B | [9], [11] |

| Patient serum (249 mg/L) [9], [11] | Ø | B | [9], [11] | ||||

| Elotuzumab | IgGκ | Anti-SLAMF7 | 190 [9] 563 [24] |

Patient serum (NI) [9], [24], [25], [26, 29] | C | C | [9], [24], [25], [26, 29] |

| Spiked serum (250 mg/L) [26] (625 mg/L) [24] (NI) [9], [31] | C | C | [9], [24], [26], [31] | ||||

| Etesevimab | IgGκ | Anti-Sars-Cov2 | 422 [19] 196a |

Spiked serum (200 mg/L) [19] | E | E | [19] |

| Imdevimab | IgGλ | Anti-Sars-Cov2 | 198 [19] 182.7a |

Spiked serum (200 mg/L) [19] | E | E | [19] |

| Patient serum (NI) [19] | E | E | [19] | ||||

| Infliximab | IgGκ | Anti-TNF | 270 [9] 100 [11] 77–277a |

Spiked serum (200 mg/L) [9] (NI) [35] | D | D | [9], [35] |

| Spiked serum (500 mg/L) [11] (NI) [18] | NA | D | [11], [18] | ||||

| Diluted in saline solution (100 mg/L) [17] | NA | D | [17] | ||||

| Spiked serum (67 mg/L) [15] (100 mg/L) [11] | Ø | Ø | [11], [15] | ||||

| Patient serum (NI) [11], [16] | Ø | Ø | [11], [16] | ||||

| Diluted in saline solution (1,000 mg/L) [15] | D | NA | [15] | ||||

| Isatuximab | IgGκ | Anti-CD38 | 230 [9] 351a |

Spiked serum (3,000 mg/L) [36] (834 mg/L) [24] (NI) [9] | C | C | [9], [24], [36] |

| Patient serum (NI) [20], [36] | C | C | [20], [36] | ||||

| Patient serum (NI) [37] | NA | C | [37] | ||||

| Natalizumab | IgGκ | Anti-4-integrin | 110a | Spiked serum (31 mg/L) [15] | Ø | Ø | [15] |

| Diluted in saline solution (1,000 mg/L) [15] | D | NA | [15] | ||||

| Nivolumab | IgGκ | Anti-PD-1 | 86.6a | Patient serum (NI) [10] | NA | E | [10] |

| Ofatumumab | IgGκ | Anti-CD20 | 1.43a | Patient serum (NI) [9], [38] | E | E | [9], [38] |

| Panitumumab | IgGκ | Anti-EGFR | 213a | Spiked serum (100 mg/L) [15] | Ø | Ø | [15] |

| Diluted in saline solution (1,000 mg/L) [15] | C | NA | [15] | ||||

| Pembrolizumab | IgGκ | Anti-PD1 | 320 [9] Cthrough=29a |

Spiked serum (250 mg/L) [39] (NI) [9] | NA | D | [9], [39] |

| Patient serum (NI) [39] | NA | Ø | [39] | ||||

| Pemivibart | IgGλ | Anti-Sars-Cov2 | 1750 [40] 1820a |

Patient serum (NI) [40] | NA | D | [40] |

| Spiked serum (1,000 mg/L) [40] | NA | D | [40] | ||||

| Rituximab | IgGκ | Anti-CD20 | 390–1,180 [9] 400 [11] 486a |

Spiked serum (400 mg/L) [9], [11], [15] (NI) [35], [41] | E | E | [9], [11], [15], [35], [41] |

| Diluted in saline solution (1,000 mg/L) [15] | E | NA | [15] | ||||

| Patient serum (NI) [16], [41] | E | E | [16], [41] | ||||

| Spiked serum (NI) [18] | NA | E | [17], [18] | ||||

| Diluted in saline solution (485 mg/L) [17] | NA | E | [17] | ||||

| Siltuximab | IgGκ | Anti-IL6 | 330 [9] 332a |

Spiked serum (NI) [9], [18], [31] | D | D | [9], [17], [18], [31] |

| Diluted in saline solution (400 mg/L) [17] | D | D | [17] | ||||

| Patient serum (NI) [9], [17], [18] | NA | D | [9], [17], [18] | ||||

| Sotrovimab | IgGκ | Anti-Sars-Cov2 | 143 [19] 170a |

Spiked serum (2,000 mg/L) [19] | E | E | [19] |

| Patient serum (NI) [19] | Ø | Ø | [19] | ||||

| Teclistamab | Bispecific IgGλ | Anti-BCMA/Anti-CD3 | 23.8a | Patient serum (NI) [42] | D | D | [42] |

| Tixagevimab | IgGκ | Anti-Sars-Cov2 | 16.5 [22] 26.9a |

Spiked serum (165 mg/L in hypogammaglobulinemia) [22] | D | D | [22] |

| Patient serum (NI) [23] | D | D | [23] | ||||

| Tocilizumab | IgGκ | Anti-sIL-6R/Anti-mIL-6R | 182a | Spiked serum (100 mg/L) [15] | Ø | Ø | [15] |

| Diluted in saline solution (1,000 mg/L) [15] | E | NA | [15] | ||||

| Trastuzumab | IgGκ | Anti-HER2 | 180 [9] 76a |

Spiked serum (NI) [9], [18] | NA | E | [9], [17], [18] |

| Diluted in saline solution (100 mg/L) [17] | NA | E | [17] | ||||

| Diluted in saline solution (1,000 mg/L) [15] | E | NA | [15] | ||||

| Spiked serum (67 mg/L) [15] | Ø | Ø | [15] | ||||

| Vedolizumab | IgGκ | Anti-α4-β7 integrin | 300 [11] 15.4a |

Spiked serum (300 mg/L) [9], [11] | D | D | [9], [11] |

| Patient serum (131 mg/L) [11] (NI) [16] | Ø | D | [11], [16] | ||||

-

aMaximum concentrations defined by the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema. Accessed on April, 2025. NA, not analysed; Ø, no interference; NI, concentration not indicated. The migration zones correspond to the position of each t-mAb on serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and/or immunofixation (IF). Zones were defined as follows; A, alpha-2 globulin region; B, beta-2 globulin region; C-zone, gamma region close to the beta-2 globulin region; D-zone, mid-gamma region; E-zone, end of the gamma region.

Almost all t-mAbs were of the IgGκ isotype, except for imdevimab and pemivibart which were IgGλ [19], [40]. Teclistamab was a bispecific IgG, containing lambda light chains [42], [43]. The t-mAbs were either present in the patient’s serum after in vivo administration, spiked into a healthy patient’s serum, or spiked into a saline solution. Maximum therapeutic concentrations of t-mAbs in serum were highly variable, ranging from 1.43 to 993 mg/L, with the highest value observed for daratumumab. The concentrations used to assess interferences in the literature ranged from 25 to 3,000 mg/L. No interference was detected below 100 mg/L. Most t-mAbs with a concentration greater than 100 mg/L were visible on IF. Ruinemans-Koerts et al. used a saline solution in which t-mAbs were diluted to 1,000 mg/L to determine their migration zone on SPEP. Although this concentration is much higher than therapeutic levels, it has made it possible to identify previously unknown migration zones of different t-mAbs: natalizumab, panitumumab, tocilizumab and trastuzumab [15]. In the same way, Bianchi et al. spiked maximum therapeutic concentrations of rituximab, siltuximab, infliximab, cetuximab, trastuzumab, bevacizumab, and adalimumab in a saline solution. This study was able to determine their migration zones on IF without the masking effect of endogenous gamma globulins [17].

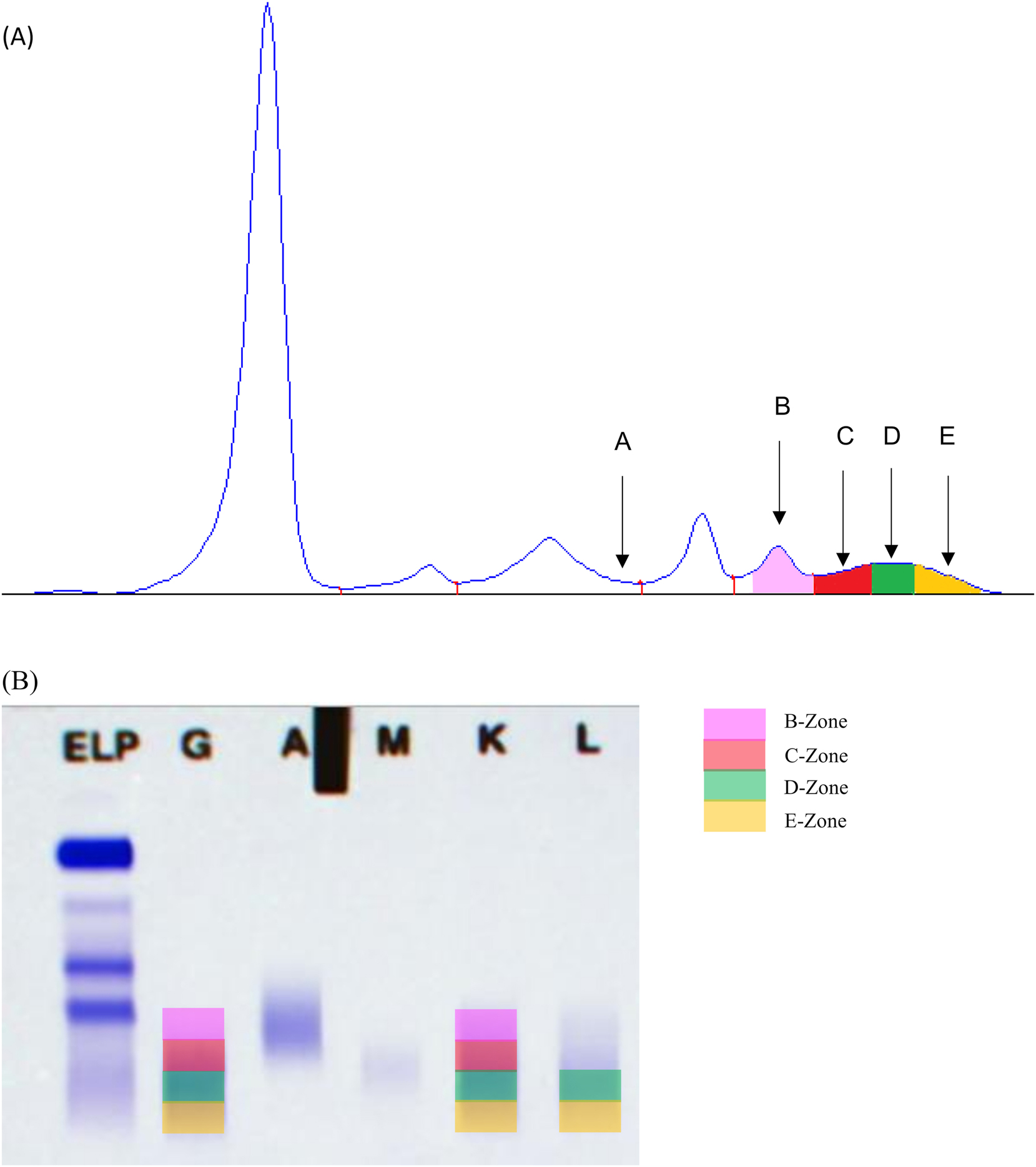

Most of t-mAbs migrated in the gamma globulin zone. More specifically, migration was most frequently observed in the mid-gamma region (13 antibodies, labeled as D-zone in Figure 2, followed by the end of the gamma region (11 antibodies, labeled as E-zone in Figure 2) and the gamma region close to the beta-2 globulin region (4 antibodies, labeled as C-zone in Figure 2). Eculizumab was the only t-mAb that migrated in the beta 2 globulin zone (labeled as B-zone in Figure 2B). Abatacept, was a fusion protein composed of the extracellular domain of CTLA-4 linked to a modified IgG1 Fc region wich explains its migration in the alpha-2 globulin region (labeled as A-zone in Figure 2A). Of note, migration of the two IgGλ t-mAbs was observed in the gamma region close to the beta-2 globulin region for pemivibart, and in the end of the gamma region for imdevimad. The migration zone of the bispecific IgG teclistamab was observed in the mid-gamma region. The interferences of t-mAbs on IF were consistent with SPEP findings, with all SPEP-detected t-mAbs also observed in IF. Since IF is more sensitive than SPEP, some t-mAbs were only detectable using IF at therapeutic concentrations (e.g. eculizumab).

Electrophoretic migration zones of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. (A) Serum protein capillary electrophoresis. A-zone: abatacept; C-zone: casirivimab, elotuzumab, isatuximab, panitumumab; D-zone: belantamab mafodotin, bevacizumab, cilgavimab, infliximab, natalizumab, siltuximab, teclistamab, tixagevimab, vedolizumab; E-zone: bamlanivimab, daratumumab, denosumab, etesevimab, imdevimab, ofatumumab, rituximab, sotrovimab, tocilizumab, trastuzumab. (B) Serum protein immunofixation. B-zone: eculizumab; C-zone: casirivimab, elotuzumab, isatuximab; D-zone: adalimumab, belantamab mafodotin, bevacizumab, cetuximab, cilgavimab, infliximab, pembrolizumab, pemivibart, siltuximab, tecistamab, tixagevimab, vedolizumab; E-zone: bamlanivimab, daratumumab, denosumab, etesevimab, imdevimab, nivolumab, ofatumumab, rituximab, sotrovimab, trastuzumab.

Discussion

This review showed that many t-mAbs can interfere with electrophoretic methods and may lead to misinterpretation of results in daily practice. Currently, the interference of 30 t-mAbs was described in the literature, which represented a small fraction of the available t-mAbs. T-mAbs interference occurs at therapeutic concentrations above approximately 100 mg/L, which is consistent with the variable detection limits of SPEP and IF [4], [5]. The limit of detection of t-mAbs by these methods is variable. Indeed, it has been shown that for daratumumab and elotuzumab, the limit is significantly influenced by the polyclonal immunoglobulin background [4], [5]. Specifically, increasing polyclonal background results in decreased sensitivity and accuracy of detection, with hypergammaglobulinemia causing elevated background noise that may mask the t-mAb signal. Conversely, hypogammaglobulinemia facilitates t-mAb detection due to reduced background interference. These findings highlight the importance of considering polyclonal background variations when interpreting SPEP and IF results for t-mAb monitoring. Recent developments in t-mAb formulations must also be considered when interpreting electrophoretic profiles. Several studies reporting serum concentrations of t-mAbs were conducted at a time when most t-mAbs were administered intravenously. However, some t-mAbs such as vedolizumab and infliximab are now available in subcutaneous formulations, which are increasingly used in clinical practice. Subcutaneous administration leads to more stable serum concentrations [44]. This underscores the need to account for evolving pharmacokinetic profiles in the interpretation of electrophoretic findings and to remain vigilant to possible interferences.

Two main methods are used in the literature to characterize t-mAbs interference: the use of sera from patients treated with t-mAbs or sera spiked with t-mAbs. There are only few conflicting data in the literature. In some cases, discrepancies arise between the patient’s serum and the serum spiked with the same t-mAb. In that case, the exact concentration of t-mAb in the patient’s serum remains unknown, though it is likely lower than in the spiked serum. Indeed, the circulating t-mAb concentration depends on a range of factors, including the patient’s individual characteristics (e.g., age and weight), his/her immune response, which may trigger the development of antibodies against the treatment, and concomitant treatments that may modify t-mAb pharmacokinetics. Furthermore, genetic variants may affect the absorption, metabolism, and elimination of the t-mAbs. The t-mAb concentration is also depending on the timing of blood collection relative to the last injection and the number of treatment cycles already administered. Dose accumulation can lead to a progressive increase in the serum concentration of the t-mAb, potentially resulting in a detectable interference in some patients undergoing prolonged treatment, but not observed in others due to shorter treatment duration or faster drug clearance. The maximum serum concentrations provided by the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) are based on cohort studies, but inter-individual variations may exist.

For some antibodies t-mAbs such as natalizumab, panitumumab and tocilizumab, no interferences were detected by spiking serum with t-mAbs [15]. However, the concentrations used for SPEP and IF analysis were significantly lower than the maximum therapeutic concentrations specified in the SmPC for each antibody. In the same way, no interferences were found for belantamab mafodotin, casirivimab and sotrovimab in the serum of treated patients [19], 20].

Regarding adalimumab, two studies reported no interference in patient serum [11], [16] as well as in spiked serum [11] when analyzed by SPEP and IF. However, another study [17] reported IF interference in spiked saline solution at the same concentration. This may be explained by the presence of endogenous gamma globulins which masked the t-mAb migration in the spiked serum. The same situation was reported for infliximab [11], [17]. Concerning casirivimab, infliximab, sotrovimab and vedolizumab, interferences were observed in spiked serum samples [9], [11], [15], [18], [19], [35], [39] but not in patient serum [11], [16], [19], [39] using SPEP analysis. Nevertheless, the concentrations used for sotrovimab were supratherapeutic. For pembrolizumab and trastuzumab, interference on IF was observed in spiked serum [9], [17], [18], [39] but not in patient serum [15], [39]. Overall, the interpretation of SPEP and IF should be performed with caution in these cases. The t-mAb bands are usually present at a low concentrations and are not likely to be mistaken for monoclonal bands associated with MM. However, in MM patients there may be confusion with residual or recurrent malignant clone. A review of medical record and treatments given should reveal the administration of monoclonal antibodies. If the location of the band is in consonance with the expected location of the therapeutic monoclonal antibody, a statement to the effect that “a low-concentration IgGκ (or IgGλ) is observed at [specified location] and is consistent with [name of therapeutic monoclonal antibody]”, would usually suffice. Serial monitoring would show a non-evolving monoclonal band further supporting its exogenous source. Specifically, removal or neutralization of the t-mAbs is hardly ever needed in addressing clinical samples.

Different methods are available to remove t-mAbs interference, involving either immunoassays based on antigen-antibody binding or mass spectrometry (MS) techniques. One of the immunological approaches is the Daratumumab Interference Reflex Assay (DIRA). DIRA utilizes an anti-daratumumab antibody (anti-idiotype) to form a daratumumab/anti-daratumumab complex. IF is then performed with the complex migrating in the alpha-globulin zone. This technique is employed by Hydrashift (Sebia™) system. DIRA is fast, specific, and does not require additional automation, but it necessitates the production of new antisera [10], [45], [46], [47], [48]. The Hydrashift Daratumumab assay, based on the DIRA technique, is commercially available. A Hydrashift Isatuximab assay has also been developed and is available for clinical use. A recent study presents an algorithm based on the SPEP position of the monoclonal peak to suspect the presence of daratumumab. The ratio of the SPEP x-axis position of daratumumab (x dara) to the position of the β1-globulin fraction (x β1) appears reliable for suspecting the presence of daratumumab and performing a DIRA [33]. Another immunological technique is the Label-Free Immunoassay (LFIA) using thin-film interferometry. Label-free technologies detect changes in refractive index or optical thickness resulting from the binding of antibody and antigen, allowing for real-time immunometric measurement. The TFI-based LFIA is rapid and automated, but currently suffers from limited sensitivity and has been developed so far only for the detection of daratumumab. However, this technique is not yet available for routine clinical practice [49].

Antigen Specific therapeutic monoclonal Antibody Depletion Assay (ASADA) use magnetic beads coated with the cognate antigen of the t-mAbs to deplete the respective t-mAb in patient samples. As a result, t-mAb becomes undetectable using IF. The serum is supplemented with biotinylated recombinant human CD38 and streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. The streptavidin-biotinylated CD38-daratumumab complex is isolated using a magnetic stand. The pre-treated samples are then analyzed like other samples using SPEP and IF. The main advantages of ASADA include its ability to be multiplexed with several antigens used to coat the solid support. In contrast to the time-consuming process of generating new antisera, soluble protein antigens can be obtained easily. It is a fast, specific method that does not require additional automation, but it is not yet available for routine clinical use [50].

Target Protein-Collision Immunofixation Electrophoresis Reflex Assay (T-CIERA) is also available to avoid t-mAbs interference. T-CIERA employs His-tagged human CD20, CD38, CD319 and PD-L1 as collision proteins. During electrophoresis, t-mAb contained in patient serum collides with the collision proteins, forming a complex. This complex exhibits a specific migration pattern. T-CIERA does not require additional instruments and can be used for a wide variety of t-mAbs, provided that the target protein is commercially available, although it has not yet been implemented in routine clinical practice [51].

Besides immunological methods, MS is an alternative approach able to distinguish monoclonal gammopathies from t-mAbs. The monoclonal immunoglobulin rapid accurate mass measurement (miRAMM) uses microflow liquid chromatography to separate heavy and light chains, coupled with electrospray-time-of-flight MS to identify the accurate molecular mass of the light chain portion of a monoclonal immunoglobulin. The multiply charged ions of the light and heavy chain ions are converted to their molecular masses, and the reconstructed peak area calculations for light chains are used for quantification. Endogenous monoclonal immunoglobulins and t-mAbs have distinct retention times making it possible to distinguish them [11], 52].

The matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) technique allows the analysis of protein composition. A laser heats a matrix, which ionizes the patient serum containing the t-mAb, converting it into ions. These ions are then accelerated by an electric field and pass through a flight tube. The time it takes for them to reach the detector is proportional to their mass, enabling their identification [53]. For instance, the MALDI-TOF method enables precise identification of t-mAbs mass within an initial analytical run without requiring additional specific reagents, facilitating adaptation to new therapeutic antibodies. However, it requires a substantial upfront investment in instrumentation.

Several methods to overcome t-mAb interferences have been described, each with its own advantages and limitations. Techniques such as DIRA, ASADA, or T-CIERA necessitate additional analytical runs with specific reagents, resulting in longer turnaround times and increased costs, whereas this is not required in MS and MALDI-TOF methods. Overall, all methods remain complex to implement in routine practice and demand significant technical expertise within clinical laboratories.

Conclusions

T-mAbs play an important role in the therapeutics landscape, especially in the treatment of MM, other tumors or chronic inflammatory diseases. This review shows that many t-mAbs interfere with electrophoretic methods and describes the various methods available to counter them in order to avoid misinterpretation of results and inappropriate decisions. Most t-mAbs with a concentration greater than 100 mg/L are visible on IF. Although almost all t-mAbs migrate into the gamma-globulin zone, some may migrate into the beta- or even alpha-globulin zone. Knowledge of the migration zones of t-mAbs in SPEP and IF constitutes an important tool for the interpretation in daily practice. However, the interferences of only a small proportion of t-mAbs are reported in the literature. New t-mAbs are developed every year for a wide range of indications, requiring constant updating of knowledge and expertise in this field.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Conceptualization, JBO; Data Curation, SP, LF; writing – original draft preparation, SP, LF and JBO; writing – review and editing SP, LF, PG and JBO; visualization SP, LF, PG and JBO; supervision, LF, JBO; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Rajkumar, SV, Dimopoulos, MA, Palumbo, A, Blade, J, Merlini, G, Mateos, MV, et al.. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:e538–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70442-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Kumar, S, Paiva, B, Anderson, KC, Durie, B, Landgren, O, Moreau, P, et al.. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e328–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30206-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. HAS (Haute Autorité de Santé). Quand prescrire une électrophorèse des protéines sériques (EPS) et conduite à tenir en cas d’une immunoglobuline monoclonale. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_2742018/fr/quand-prescrire-une-electrophorese-des-proteines-seriques-eps-et-conduite-a-tenir-en-cas-d-une-immunoglobuline-monoclonale [Accessed 18 Mar 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

4. Jacobs, JFM, Turner, KA, Graziani, MS, Frinack, JL, Ettore, MW, Tate, JR, et al.. An international multi-center serum protein electrophoresis accuracy and M-protein isotyping study. Part II: limit of detection and follow-up of patients with small M-proteins. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020;58:547–59. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2019-1105.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Turner, KA, Frinack, JL, Ettore, MW, Tate, JR, Graziani, MS, Jacobs, JFM, et al.. An international multi-center serum protein electrophoresis accuracy and M-protein isotyping study. Part I: factors impacting limit of quantitation of serum protein electrophoresis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020;58:533–46. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2019-1104.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Kyle, RA, Rajkumar, SV. Epidemiology of the plasma-cell disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2007;20:637–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beha.2007.08.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Kyle, RA, Therneau, TM, Rajkumar, SV, Larson, DR, Plevak, MF, Offord, JR, et al.. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1362–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa054494.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Dimopoulos, MA, Moreau, P, Terpos, E, Mateos, MV, Zweegman, S, Cook, G, et al.. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2021;32:309–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Malik, S, Toong, C. Monoclonal antibody interference in electrophoresis. Pathology (Phila) 2023;55:163–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2022.05.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Noori, S, Verkleij, CPM, Zajec, M, Langerhorst, P, Bosman, PWC, de Rijke, YB, et al.. Monitoring the M-protein of multiple myeloma patients treated with a combination of monoclonal antibodies: the laboratory solution to eliminate interference. Clin Chem Lab Med 2021;59:1963–71. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2021-0399.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Willrich, MAV, Ladwig, PM, Andreguetto, BD, Barnidge, DR, Murray, DL, Katzmann, JA, et al.. Monoclonal antibody therapeutics as potential interferences on protein electrophoresis and immunofixation. Clin Chem Lab Med 2016;54:1085–93. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2015-1023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Montalban, X, Gold, R, Thompson, AJ, Otero-Romero, S, Amato, MP, Chandraratna, D, et al.. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J 2018;24:96–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517751049.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. FDA (Food and Drug Administration). Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibodies for treatment of COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-monoclonal-antibodies-treatment-covid-19 [Accessed 18 Mar 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

14. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al.. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Ruinemans-Koerts, J, Verkroost, C, Schmidt-Hieltjes, Y, Wiegers, C, Curvers, J, Thelen, M, et al.. Interference of therapeutic monoclonal immunoglobulins in the investigation of M-proteins. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014;52:e235–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2013-0898.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Šahinović, I, Sinčić-Petričević, J, Oršić-Frič, V, Borzan, V, Pavela, J, Fijačko, M, et al.. Therapeutic monoclonal antibody interference in electrophoretic and immunofixation techniques. Clin Chim Acta 2019;493:S45–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2019.03.104.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Bianchi, GD, Voorhees, PM, Hainsworth, SA, Whinna, HC, Chapman, JF, Hammett-Stabler, CA, et al.. Therapeutic monoclonal antibody interference with serum protein electrophoresis testing. Blood 2010;116:5025. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v116.21.5025.5025.Suche in Google Scholar

18. McCudden, CR, Voorhees, PM, Hainsworth, SA, Whinna, HC, Chapman, JF, Hammett-Stabler, CA, et al.. Interference of monoclonal antibody therapies with serum protein electrophoresis tests. Clin Chem 2010;56:1897–9. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2010.152116.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Scholl, AR, Korentzelos, D, Forns, TE, Brenneman, EK, Kelm, M, Datto, M, et al.. Characterization of casirivimab plus imdevimab, sotrovimab, and bamlanivimab plus etesevimab-derived interference in serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation electrophoresis. J Appl Lab Med 2022;7:1379–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/jalm/jfac064.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Jimenez, A, Scholl, AR, Wang, B, Schilke, M, Carlsen, ED. Characteristics of isatuximab-derived interference in serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and an absence of sustained in vivo interference due to belantamab mafodotin and denosumab. Clin Biochem 2024;127–128:110761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2024.110761.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Wu, JY, Wu, X, Ding, L, Zhao, YB, Ai, B, Li, Y, et al.. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of bevacizumab in Chinese patients with advanced cancer. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:901.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Baloda, V, McCreary, EK, Goscicki, BK, Shurin, MR, Wheeler, SE. Tixagevimab plus cilgavimab does not affect the interpretation of electrophoretic and free light chain assays. Am J Clin Pathol 2023;159:10–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqac137.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Shah, SK, Hagrass, HA. Evusheld, a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-directed attachment inhibitor, appears in serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation: a case study. Lab Med 2023;54:e201–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmad085.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Murata, K, McCash, SI, Carroll, B, Lesokhin, AM, Hassoun, H, Lendvai, N, et al.. Treatment of multiple myeloma with monoclonal antibodies and the dilemma of false positive M-spikes in peripheral blood. Clin Biochem 2018;51:66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.09.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Liu, L, Wertz, WJ, Kondisko, A, Shurin, MR, Wheeler, SE. Incidence and management of therapeutic monoclonal antibody interference in monoclonal gammopathy monitoring. J Appl Lab Med 2020;5:29–40. https://doi.org/10.1373/jalm.2019.029009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Tang, F, Malek, E, Math, S, Schmotzer, CL, Beck, RC. Interference of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies with routine serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation in patients with myeloma: frequency and duration of detection of daratumumab and elotuzumab. Am J Clin Pathol 2018;150:121–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqy037.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Kirchhoff, DC, Murata, K, Thoren, KL. Use of a daratumumab-specific immunofixation assay to assess possible immunotherapy interference at a major cancer center: our experience and recommendations. J Appl Lab Med 2021;6:1476–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/jalm/jfab055.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Rabut, É, Castro-Fernandez, A, Le Gall, V, Meknache, N. Case report: serological testing interference of daratumumab (anti-CD38) therapy in multiple myeloma. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 2017;75:351–5. https://doi.org/10.1684/abc.2017.1237.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. van de Donk, NWCJ, Moreau, P, Plesner, T, Palumbo, A, Gay, F, Laubach, JP, et al.. Clinical efficacy and management of monoclonal antibodies targeting CD38 and SLAMF7 in multiple myeloma. Blood 2016;127:681–95. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-10-646810.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Liang, S, Feng, W, Ma, H, Zhang, L, Jia, C. False positive results: a challenge for laboratory physicians and hematologists in treating multiple myeloma with daratumumab. Hematology 2022;27:332–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078454.2022.2045723.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. McCudden, CR, Jacobs, JFM, Keren, D, Caillon, H, Dejoie, T, Andersen, K. Recognition and management of common, rare, and novel serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation interferences. Clin Biochem 2018;51:72–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.08.013.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Karmali, J, Alibay, Y, Baba-Ahmed, F, Ngo, S, Victor, M, Bardet, V, et al.. Traitement par daratumumab (anticorps anti-CD38), une avancée thérapeutique majeure pour les patients atteints de myélome multiple mais une complexité pour les biologistes. Rev Francoph Lab 2022;2022:26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1773-035x(22)00280-5.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Leonard, A, Bonnet, B, Croizier, C, Evrard, B, Sapin, V, Fogli, A, et al.. [Studying daratumumab’s interference in serum protein electrophoresis: two case reports]. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 2025;83:202–10. https://doi.org/10.1684/abc.2025.1963.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Aydin, O, Aykas, F. Therapeutic monoclonal antibody interference in monoclonal gammopathy monitoring: a denosumab experience. Lab Med 2023;54:e95–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmac129.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Malik, S, Toong, C. Monoclonal antibody interference in serum electrophoresis. Pathology (Phila) 2019;51:S67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2018.12.156.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Wheeler, RD, Costa, MV, Crichlow, A, Willis, F, Reyal, Y, Linstead, SE, et al.. Case report: interference from isatuximab on serum protein electrophoresis prevented demonstration of complete remission in a myeloma patient. Ann Clin Biochem 2022;59:144–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/00045632211062080.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Thoren, K, Menad, S, Nouadje, G, Macé, S. Isatuximab-specific immunofixation electrophoresis assay to remove interference in serum M-protein measurement in patients with multiple myeloma. J Appl Lab Med 2024;9:661–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jalm/jfae028.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Genzen, JR, Kawaguchi, KR, Furman, RR. Detection of a monoclonal antibody therapy (ofatumumab) by serum protein and immunofixation electrophoresis. Br J Haematol 2011;155:123–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08644.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Kourelis, T, Murray, DL, Dispenzieri, A, Frinack, JL, Hetrick, MD, Willrich, MAV. Evaluating pembrolizumab interference with monoclonal protein detection by immunofixation and by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MASS-FIX). Blood 2017;130:4428.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Fink, SL, Treger, RS. The therapeutic monoclonal antibody pemivibart causes persistent interference in immunofixation electrophoresis. J Appl Lab Med 2025:jfaf002.10.1093/jalm/jfaf002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Guancial, EA, Mahajan, VS, McCaffrey, RP, Lindeman, N. Theraputic monoclonal antibody interference in immunofixation electrophoresis. Blood 2010;116:4996. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v116.21.4996.4996.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Kadkhoda, K, Faiman, B, Valent, J, Albahra, S, Boyert, N. The first case of Teclistamab interference with serum electrophoresis and immunofixation. Clin Chem Lab Med 2025;63:e172–4. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2025-0382.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Choi, SM, Lee, JH, Ko, S, Hong, SS, Jin, HE. Mechanism of action and pharmacokinetics of approved bispecific antibodies. Biomol Ther 2024;32:708–22. https://doi.org/10.4062/biomolther.2024.146.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Little, RD, Ward, MG, Wright, E, Jois, AJ, Boussioutas, A, Hold, GL, et al.. Therapeutic drug monitoring of subcutaneous infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease-understanding pharmacokinetics and exposure response relationships in a new era of subcutaneous biologics. J Clin Med 2022;11:6173. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11206173.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Shirouchi, Y, Kazumi, K, Sekita, T, Amano, N, Nakayama, K, Miyake, K, et al.. Impact of M-protein detection on the response evaluations of patients undergoing treatment with the IgG-κ monoclonal antibodies daratumumab or isatuximab, and discrepancies between immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) systems and reagents. Cancer Med 2024;13:e70128. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.70128.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Thoren, KL, Pianko, MJ, Maakaroun, Y, Landgren, CO, Ramanathan, LV. Distinguishing drug from disease by use of the Hydrashift 2/4 daratumumab assay. J Appl Lab Med 2019;3:857–63. https://doi.org/10.1373/jalm.2018.026476.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Van de Donk, NWCJ, Otten, HG, El Haddad, O, Axel, A, Sasser, AK, Croockewit, S, et al.. Interference of daratumumab in monitoring multiple myeloma patients using serum immunofixation electrophoresis can be abrogated using the daratumumab IFE reflex assay (DIRA). Clin Chem Lab Med 2016;54:1105–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2015-0888.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Caillon, H, Irimia, A, Simon, JS, Axel, A, Sasser, K, Scullion, MJ, et al.. Overcoming the interference of daratumumab with immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) using an industry-developed dira test : Hydrashift 2/4 daratumumab. Blood 2016;128:2063. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v128.22.2063.2063.Suche in Google Scholar

49. Luo, YR, Chakraborty, I, Zuk, RF, Lynch, KL, Wu, AHB. A thin-film interferometry-based label-free immunoassay for the detection of daratumumab interference in serum protein electrophoresis. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem 2020;502:128–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2019.12.019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Liu, L, Shurin, MR, Wheeler, SE. A novel approach to remove interference of therapeutic monoclonal antibody with serum protein electrophoresis. Clin Biochem 2020;75:40–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.10.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Teuwen, JTJ, Ritzen, LFL, Knapen-Portz, YM, Ludwiczek, PK, Damoiseaux, JGMC, van Beers, JJBC, et al.. Identifying therapeutic monoclonal antibodies using target protein collision electrophoresis reflex assay to separate the wheat from the chaff. J Immunol Methods 2023;522:113552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2023.113552.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Mills, JR, Kohlhagen, MC, Willrich, MAV, Kourelis, T, Dispenzieri, A, Murray, DL. A universal solution for eliminating false positives in myeloma due to therapeutic monoclonal antibody interference. Blood 2018;132:670–2. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-05-848986.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Moore, LM, Cho, S, Thoren, KL. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry distinguishes daratumumab from M-proteins. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem 2019;492:91–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2019.02.017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Challenging the dogma: why reviewers should be allowed to use AI tools

- Multivariate approaches to improve the interpretation of laboratory data

- Review

- Interference of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies with electrophoresis and immunofixation of serum proteins: state of knowledge and systematic review

- Opinion Papers

- Urgent call to the European Commission to simplify and contextualize IVDR Article 5.5 for tailored and precision diagnostics

- The importance of laboratory medicine in the management of CKD-MBD: insights from the KDIGO 2023 controversies conference

- Supplementation of pyridoxal-5′-phosphate in aminotransferase reagents: a matter of patient safety

- HCV serology: an unfinished agenda

- From metabolic profiles to clinical interpretation: multivariate approaches to population-based and personalized reference intervals and reference change values

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- A multiplex allele specific PCR capillary electrophoresis (mASPCR-CE) assay for simultaneously analysis of SMN1/SMN2/NAIP copy number and SMN1 loss-of-function variants

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- From assessment to action: experience from a quality improvement initiative integrating indicator evaluation and adverse event analysis in a clinical laboratory

- Evaluation of measurement uncertainty of 11 serum proteins measured by immunoturbidimetric methods according to ISO/TS 20914: a 1-year laboratory data analysis

- Assessing the harmonization of current total vitamin B12 measurement methods: relevance and implications

- The current status of serum insulin measurements and the need for standardization

- Method comparison of plasma and CSF GFAP immunoassays across multiple platforms

- Cerebrospinal fluid leptin in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to plasma levels and to cerebrospinal amyloid

- Verification of the T50 Calciprotein Crystallization test: bias estimation and interferences

- An innovative immunoassay for accurate aldosterone quantification: overcoming low-level inaccuracy and renal dysfunction-associated interference

- Oral salt loading combined with postural stimulation tests for confirming and subtyping primary aldosteronism

- Evaluating the performance of a multiparametric IgA assay for celiac disease diagnosis

- Clinical significance of anti-mitochondrial antibodies and PBC-specific anti-nuclear antibodies in evaluating atypical primary biliary cholangitis with normal alkaline phosphatase levels

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Establishment of region-, age- and sex-specific reference intervals for aldosterone and renin with sandwich chemiluminescence immunoassays

- Validation of a plasma GFAP immunoassay and establishment of age-related reference values: bridging analytical performance and routine implementation

- Comparative analysis of population-based and personalized reference intervals for biochemical markers in peri-menopausal women: population from the PALM cohort study

- Hematology and Coagulation

- Evaluation of stability and potential interference on the α-thalassaemia early eluting peak and immunochromatographic strip test for α-thalassaemia --SEA carrier screening

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Analytical and clinical evaluation of an automated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay for whole blood

- Diabetes

- Method comparison of diabetes mellitus associated autoantibodies in serum specimens

- Letters to the Editor

- Permitting disclosed AI assistance in peer review: parity, confidentiality, and recognition

- Response to the editorial by Karl Lackner

- Hemolysis detection using the GEM 7000 at the point of care in a pediatric hospital setting: does it affect outcomes?

- Estimation of measurement uncertainty for free drug concentrations using ultrafiltration

- Cryoglobulin pre-analysis over the weekend

- Accelerating time from result to clinical action: impact of an automated critical results reporting system

- Recent decline in patient serum folate test levels using Roche Diagnostics Folate III assay

- Kidney stones consisting of 1-methyluric acid

- Congress Abstracts

- 7th EFLM Conference on Preanalytical Phase

- Association of Clinical Biochemists in Ireland Annual Conference

- Association of Clinical Biochemists in Ireland Annual Conference

- 17th Congress of the Portuguese Society of Clinical Chemistry, Genetics and Laboratory Medicine

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Challenging the dogma: why reviewers should be allowed to use AI tools

- Multivariate approaches to improve the interpretation of laboratory data

- Review

- Interference of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies with electrophoresis and immunofixation of serum proteins: state of knowledge and systematic review

- Opinion Papers

- Urgent call to the European Commission to simplify and contextualize IVDR Article 5.5 for tailored and precision diagnostics

- The importance of laboratory medicine in the management of CKD-MBD: insights from the KDIGO 2023 controversies conference

- Supplementation of pyridoxal-5′-phosphate in aminotransferase reagents: a matter of patient safety

- HCV serology: an unfinished agenda

- From metabolic profiles to clinical interpretation: multivariate approaches to population-based and personalized reference intervals and reference change values

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- A multiplex allele specific PCR capillary electrophoresis (mASPCR-CE) assay for simultaneously analysis of SMN1/SMN2/NAIP copy number and SMN1 loss-of-function variants

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- From assessment to action: experience from a quality improvement initiative integrating indicator evaluation and adverse event analysis in a clinical laboratory

- Evaluation of measurement uncertainty of 11 serum proteins measured by immunoturbidimetric methods according to ISO/TS 20914: a 1-year laboratory data analysis

- Assessing the harmonization of current total vitamin B12 measurement methods: relevance and implications

- The current status of serum insulin measurements and the need for standardization

- Method comparison of plasma and CSF GFAP immunoassays across multiple platforms

- Cerebrospinal fluid leptin in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to plasma levels and to cerebrospinal amyloid

- Verification of the T50 Calciprotein Crystallization test: bias estimation and interferences

- An innovative immunoassay for accurate aldosterone quantification: overcoming low-level inaccuracy and renal dysfunction-associated interference

- Oral salt loading combined with postural stimulation tests for confirming and subtyping primary aldosteronism

- Evaluating the performance of a multiparametric IgA assay for celiac disease diagnosis

- Clinical significance of anti-mitochondrial antibodies and PBC-specific anti-nuclear antibodies in evaluating atypical primary biliary cholangitis with normal alkaline phosphatase levels

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Establishment of region-, age- and sex-specific reference intervals for aldosterone and renin with sandwich chemiluminescence immunoassays

- Validation of a plasma GFAP immunoassay and establishment of age-related reference values: bridging analytical performance and routine implementation

- Comparative analysis of population-based and personalized reference intervals for biochemical markers in peri-menopausal women: population from the PALM cohort study

- Hematology and Coagulation

- Evaluation of stability and potential interference on the α-thalassaemia early eluting peak and immunochromatographic strip test for α-thalassaemia --SEA carrier screening

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Analytical and clinical evaluation of an automated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay for whole blood

- Diabetes

- Method comparison of diabetes mellitus associated autoantibodies in serum specimens

- Letters to the Editor

- Permitting disclosed AI assistance in peer review: parity, confidentiality, and recognition

- Response to the editorial by Karl Lackner

- Hemolysis detection using the GEM 7000 at the point of care in a pediatric hospital setting: does it affect outcomes?

- Estimation of measurement uncertainty for free drug concentrations using ultrafiltration

- Cryoglobulin pre-analysis over the weekend

- Accelerating time from result to clinical action: impact of an automated critical results reporting system

- Recent decline in patient serum folate test levels using Roche Diagnostics Folate III assay

- Kidney stones consisting of 1-methyluric acid

- Congress Abstracts

- 7th EFLM Conference on Preanalytical Phase

- Association of Clinical Biochemists in Ireland Annual Conference

- Association of Clinical Biochemists in Ireland Annual Conference

- 17th Congress of the Portuguese Society of Clinical Chemistry, Genetics and Laboratory Medicine