Laboratory diagnostics is a highly complex and multifaceted enterprise, which provides a fundamental contribution to the clinical decision making by means of minimally invasive testing [1]. Besides this general portrayal, the organization of clinical laboratory services not only is markedly heterogeneous from one country to another, but also varies widely within the same country. Regardless of speculative or logistical considerations on consolidation and laboratory networking [2], the leading determinants of clinical laboratory services typically include quality and accuracy of testing, turnaround time, the nature of analysis and additional services provided, expenditures, revenues along with certification or accreditation to reliable standards.

Now, with the global economy dramatically affected by an unprecedented and widespread financial crisis (i.e., the most serious recession in postwar history), national healthcare systems – and clinical laboratories as well – are squeezed between a rock and a hard place, wherein the need to maintain a high degree of quality and excellence must be balanced against lower funding. The gradually widening gap between economical resources and request of testing placed on laboratory facilities is thereby expected to become the leading driver of the diagnostic market in the very next future. Another important aspect that may seriously influence the future trend of the in vitro diagnostic (IVD) market is the negative impact of the economical crisis on wealth and employment, which will expectedly generate reductions pullback in consumers’ use of non-essential routine medical care and diagnostic testing, with the tangible threat that the slowdown will soon inflate other areas which are less discretionary [3]. Long payment delays and potential bankruptcy of some countries are additional problems that may dramatically influence future trends. Another good point is the US election, with its reflection on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) strongly supported by President Obama [4]. It is in fact predictable that the policy consequences of election will be suddenly and persuasively felt in connection with the healthcare reform. If the Democrats hold the White House and Senate in 2013, the ACA will be implemented mostly as constructed. However, if the Republicans win the elections, the ACA will undergo a dramatic deconstruction along with fears that Medicaid expansion may be seriously jeopardized [5].

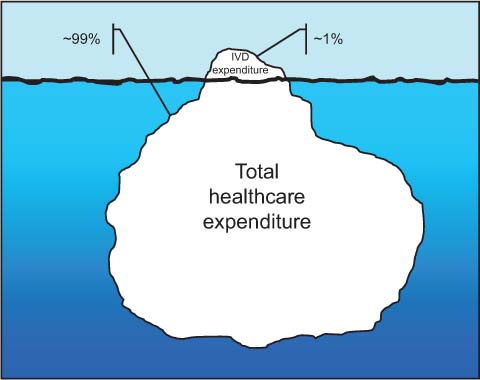

Before specifically addressing the relationship between testing volumes and expenditure, it seems reasonable to give a synthetic picture of the relationship between healthcare and laboratory economics. According to the European Diagnostic Manufacturers Association (EDMA), the 2010 revenues generated by the IVD in Europe approximated €10.5 billion, thus representing roughly 0.8% of the total European healthcare expenditure, which has been estimated at approximately €1312.5 billion [6]. The IVD expenditure per capita has reached €20.6 in the same year, thus slightly increasing from €20.1 in 2009. The five leading markets (i.e., Germany, France, Italy, Spain and UK, in decreasing order) accounted for nearly €7.5 billion, thereby representing more than two thirds of the all IVD market across Europe. Taking the Italian market as an example, the IVD expenditure has reached €1.760 billion in 2010 (official source: Assobiomedica), which represents a modest 1.6% of the total national healthcare expenditure (estimated at €112.889 billion in the same year). It is also noteworthy that the expenditure of the IVD market was nearly half of that recorded for other biomedicals (e.g., €3.628 billion for pacemakers, defibrillators, prosthetic devices, catheters, etc.), and virtually identical to that of medical informatics services and telemedicine (€1.577 billion). According to these figures, which would expectedly mirror those of other western countries, it is reasonable to put forward the concept that the costs of laboratory diagnostics are little more than the tip of the iceberg for the total healthcare expenditure (Figure 1). Essentially, the financial reforms of many governments in Europe and abroad have been insistently focused to control and even restrain IVD expenditure. This policy has been driven by several questionable conjectures. While most policy makers struggle with fragmentation of budgeting and measurement systems at different levels of healthcare, the highly accountability and easily monitoring of clinical laboratories render them particularly vulnerable to draconian interventions and with less fear of negative political revenues. While it is unpopular – and thereby politically unsustainable – that clinicians should not treat their patients or address them to another hospital for appropriate triage, it is much more accepted that laboratory professionals would cut down quality and volumes of testing, or downsize, merge and consolidate smaller and often highly focused laboratories within multifunctional, huge facilities (e.g., the so-called “factory scenario”, dominated by megalaboratories) [7], where purchase volumes are increased rather than decreased, and laboratory testing is then frequently perceived as a commodity [8]. All this would happen, despite most of us clearly acknowledging that laboratory services should be reorganized around medical conditions and care cycles, rather than according to external and often questionable financial analyses.

Burden of in vitro diagnostic (IVD) costs on total healthcare expenditure.

As the global financial crisis continues, and despite consolidated evidence that IVD testing is very often the most cost-efficient mean for obtaining clinical information, there is mounting fear among the laboratory community that these trends may even get worse. Even the consolidated concept that laboratory testing is a recession-proof industry is being seriously jeopardized by recent evidence attesting that recession has already affected this area.

Notwithstanding, the very modest role played by the IVD testing in inflating the total healthcare expenditure, some governments are continuously reducing the public funding to laboratory services, in the attempt to balance budgets, applying short-sighted limitations on sophisticated high-end equipment, testing volumes and reimbursements. One of the most conveyed and narcissist message is the unverified assumption that generalized centralization of diagnostic testing would always reveal as a reliable strategy for providing tangible economical revenues to the finances of healthcare system. In this perspective, it would become decisive to demonstrate that the dogma “larger volumes=better quality and lower cost”, which is administered like a mantra by several policy makers worldwide, is somehow flawed. The paucity of previous evidence, mostly anecdotal and poorly referenced, has prompted Barletta and co-workers to undertake an innovative and interesting analysis that we publish in this issue of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Briefly, this study was undertaken to evaluate the cost of delivering laboratory services in 20 Italian clinical laboratories by means of an universally accepted approach, that is the “activity-based costing analysis” [9]. The interesting data provided in this paper confutes the existence of a linear relationship between increasing test volumes and decreasing costs, at least outside the boundaries between 1.1 and 1.8 million tests. Conversely, the authors found a good relationship between volumes and number of staff, as well as between the number of senior staff and volumes, although such a trend was biased by some covariates (e.g., medical technologists, degree and type of automation). It seems hence reasonable that – at least in a “sentinel Country” like Italy – the only virtually reasonable reorganization of laboratory services should engage those facilities operating with modest test volumes, hypothetically comprised between 1 and 2 million tests. Over and even below such thresholds, major saving would be plausibly eroded, so that whatever politically- and economically-driven reorganization towards consolidation of medium laboratories within high volumes facilities would finally be revealed as a wasted financial effort.

Due to the severe economic recession that is more or less spreading throughout the world, it seems very unlikely that the economic growth will recover soon, and the debt may still constrain public finances for the foreseeable future. There is now mounting debate around the relationship between volume, value and outcomes in healthcare, and the concept that higher value providers would provide better outcomes at lower cost than higher volume services is prepotently affirming [10]. Expectedly, this paradigm shift in healthcare economics may soon get to a point where reimbursement and payment would be driven by outcomes achieved by delivering an effective set of services that varies according to clinical and environmental settings, rather than on volume and type of services provided. The data shown by Barletta et al. are in line with this hypothesis, and will undoubtedly cause headaches to some health policy makers, and may also become the subject of fierce controversies since it is now finally acknowledged that testing volume does not necessarily go hand in hand with costs or outcomes. We have little doubt that this study will fill the gap of the shortage of studies on clinical laboratory economics, thus encouraging governments to use this sound evidence when steering healthcare reforms or policies to face the current financial challenges. It should be clear to everybody that service delivery is directly connected with resource generation. As such, IVD testing is a potential resource and not a hindrance for filling the holes of healthcare economy, wherein indiscriminate interventions, such as those aimed at increasing the number of mega-laboratories with the false assumption of lowering costs would fall short and even turn out to be a masochist strategy. Since the IVD testing market is unequivocally one of the brightest spots in healthcare economy, public policies should aim to foster continued growth rather than depression of this area. Incidentally, there is mounting evidence that some other strategies, such as appropriateness of test requests and better utilization of test results [11, 12], may be pursued for delivering a better IVD testing without spending more.

References

1. Plebani M. Laboratory diagnostics in the third millennium: where, how and why. Clin Chem Lab Med 2010;48:901–2.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000279341900001&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Lippi G, Simundic AM. Laboratory networking and sample quality: a still relevant issue for patient safety. Clin Chem Lab Med 2012;50:1703–5.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000309955500004&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Favaloro EJ, Plebani M, Lippi G. Regulation of in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) for use in clinical diagnostic laboratories: towards the light or dark in clinical laboratory testing? Clin Chem Lab Med 2011;49:1965–73.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000299856700006&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Lippi G, Plebani M. The “Obamanomics”: a revolution in laboratory diagnostics. Clin Chem Lab Med 2010;48:741–3.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000279342700001&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. McDonough JE. The road ahead for the Affordable Care Act. N Engl J Med 2012;367:199–201.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000306522900003&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f310.1056/NEJMp1206845Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. European Diagnostic Manufacturers Association. Available at: http://www.edma-ivd.eu/. Accessed 9 July, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

7. Plebani M, Lippi G. Is laboratory medicine a dying profession? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed. Clin Biochem 2010;43:939–41.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000280026900001&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f310.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.05.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Plebani M, Lippi G. Focused factories and boutique laboratories. The truth might lie in between. Clin Biochem 2010;43:1484–5.10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.09.001http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000284520200024&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f3Search in Google Scholar

9. Barletta G, Zaninotto M, Faggian D, Plebani M. Shop for quality or quantity? Volumes and costs in clinical laboratories. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:295–301.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000314999000018&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f310.1515/cclm-2012-0415Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. VanLare JM, Conway PH. Value-based purchasing – national programs to move from volume to value. N Engl J Med 2012;367:292–5.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000306738300002&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f310.1056/NEJMp1204939Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Plebani M, Favaloro EJ, Lippi G. Patient safety and quality in laboratory and hemostasis testing: a renewed loop? Semin Thromb Hemost 2012;38:553–8.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000308401300002&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f310.1055/s-0032-1315960Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Plebani M, Lippi G. Closing the brain-to-brain loop in laboratory testing. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011;49:1131–3.http://gateway.webofknowledge.com/gateway/Gateway.cgi?GWVersion=2&SrcApp=PARTNER_APP&SrcAuth=LinksAMR&KeyUT=000292538800006&DestLinkType=FullRecord&DestApp=ALL_WOS&UsrCustomerID=b7bc2757938ac7a7a821505f8243d9f3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2013 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Letters to the Editor

- Performance evaluation of three different immunoassays for detection of antibodies to hepatitis B core

- Serum homocysteine concentrations in Chinese children with autism

- Interchangeability of venous and capillary HbA1c results is affected by oxidative stress

- Interference of hemoglobin (Hb) N-Baltimore on measurement of HbA1c using the HA-8160 HPLC method

- First human isolate of Mycobacterium madagascariense in the sputum of a patient with tracheobronchitis

- Protein S and protein C measurements should not be undertaken during vitamin K antagonist therapy

- α2-HS glycoprotein is an essential component of cryoglobulin associated with chronic hepatitis C

- An unusual interference in CK MB assay caused by a macro enzyme creatine phosphokinase (CK) type 2 in HIV-infected patients

- An automated technique for the measurement of the plasma glutathione reductase activity and determination of reference limits for a healthy population

- Is osteopontin stable in plasma and serum?

- Evidence-based approach to reducing perceived wasteful practices in laboratory medicine

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Editorials

- Testing volume is not synonymous of cost, value and efficacy in laboratory diagnostics

- Lessons from controversy: biomarkers evaluation

- Commercial immunoassays in biomarkers studies: researchers beware!1)

- Trials and tribulations in lupus anticoagulant testing

- Reviews

- Mass spectrometry: a revolution in clinical microbiology?

- Chronic Chagas disease: from basics to laboratory medicine

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Shop for quality or quantity? Volumes and costs in clinical laboratories

- Minor improvement of venous blood specimen collection practices in primary health care after a large-scale educational intervention

- Evaluation of high resolution gel β2-transferrin for detection of cerebrospinal fluid leak

- Serum kallikrein-8 correlates with skin activity, but not psoriatic arthritis, in patients with psoriatic disease

- Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) in the assessment of inflammatory activity of rheumatoid arthritis patients in remission

- Bone mass density selectively correlates with serum markers of oxidative damage in post-menopausal women

- Validation of a fast and reliable liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization method for simultaneous quantitation of voriconazole, itraconazole and its active metabolite hydroxyitraconazole in human plasma

- Performance of different screening methods for the determination of urinary glycosaminoclycans

- Intestinal permeability and fecal eosinophil-derived neurotoxin are the best diagnosis tools for digestive non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy in toddlers

- An internal validation approach and quality control on hematopoietic chimerism testing after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation

- Serum levels of IgG antibodies against oxidized LDL and atherogenic indices in HIV-1-infected patients treated with protease inhibitors

- Cooperation experience in a multicentre study to define the upper limits in a normal population for the diagnostic assessment of the functional lupus anticoagulant assays

- Contribution of procoagulant phospholipids, thrombomodulin activity and thrombin generation assays as prognostic factors in intensive care patients with septic and non-septic organ failure

- Suitability of POC lactate methods for fetal and perinatal lactate testing: considerations for accuracy, specificity and decision making criteria

- Point-of-care testing on admission to the intensive care unit: lactate and glucose independently predict mortality

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- CA125 reference values change in male and postmenopausal female subjects

- Distributions and ranges of values of blood and urinary biomarker of inflammation and oxidative stress in the workers engaged in office machine manufactures: evaluation of reference values

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Association of acute phase protein-haptoglobin, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in buccal cancer: a preliminary report

- Comparison of diagnostic and prognostic performance of two assays measuring thymidine kinase 1 activity in serum of breast cancer patients

- Evaluation of the BRAHMS Kryptor® Thyroglobulin Minirecovery Test in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma

Articles in the same Issue

- Letters to the Editor

- Performance evaluation of three different immunoassays for detection of antibodies to hepatitis B core

- Serum homocysteine concentrations in Chinese children with autism

- Interchangeability of venous and capillary HbA1c results is affected by oxidative stress

- Interference of hemoglobin (Hb) N-Baltimore on measurement of HbA1c using the HA-8160 HPLC method

- First human isolate of Mycobacterium madagascariense in the sputum of a patient with tracheobronchitis

- Protein S and protein C measurements should not be undertaken during vitamin K antagonist therapy

- α2-HS glycoprotein is an essential component of cryoglobulin associated with chronic hepatitis C

- An unusual interference in CK MB assay caused by a macro enzyme creatine phosphokinase (CK) type 2 in HIV-infected patients

- An automated technique for the measurement of the plasma glutathione reductase activity and determination of reference limits for a healthy population

- Is osteopontin stable in plasma and serum?

- Evidence-based approach to reducing perceived wasteful practices in laboratory medicine

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Editorials

- Testing volume is not synonymous of cost, value and efficacy in laboratory diagnostics

- Lessons from controversy: biomarkers evaluation

- Commercial immunoassays in biomarkers studies: researchers beware!1)

- Trials and tribulations in lupus anticoagulant testing

- Reviews

- Mass spectrometry: a revolution in clinical microbiology?

- Chronic Chagas disease: from basics to laboratory medicine

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Shop for quality or quantity? Volumes and costs in clinical laboratories

- Minor improvement of venous blood specimen collection practices in primary health care after a large-scale educational intervention

- Evaluation of high resolution gel β2-transferrin for detection of cerebrospinal fluid leak

- Serum kallikrein-8 correlates with skin activity, but not psoriatic arthritis, in patients with psoriatic disease

- Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) in the assessment of inflammatory activity of rheumatoid arthritis patients in remission

- Bone mass density selectively correlates with serum markers of oxidative damage in post-menopausal women

- Validation of a fast and reliable liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization method for simultaneous quantitation of voriconazole, itraconazole and its active metabolite hydroxyitraconazole in human plasma

- Performance of different screening methods for the determination of urinary glycosaminoclycans

- Intestinal permeability and fecal eosinophil-derived neurotoxin are the best diagnosis tools for digestive non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy in toddlers

- An internal validation approach and quality control on hematopoietic chimerism testing after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation

- Serum levels of IgG antibodies against oxidized LDL and atherogenic indices in HIV-1-infected patients treated with protease inhibitors

- Cooperation experience in a multicentre study to define the upper limits in a normal population for the diagnostic assessment of the functional lupus anticoagulant assays

- Contribution of procoagulant phospholipids, thrombomodulin activity and thrombin generation assays as prognostic factors in intensive care patients with septic and non-septic organ failure

- Suitability of POC lactate methods for fetal and perinatal lactate testing: considerations for accuracy, specificity and decision making criteria

- Point-of-care testing on admission to the intensive care unit: lactate and glucose independently predict mortality

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- CA125 reference values change in male and postmenopausal female subjects

- Distributions and ranges of values of blood and urinary biomarker of inflammation and oxidative stress in the workers engaged in office machine manufactures: evaluation of reference values

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Association of acute phase protein-haptoglobin, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in buccal cancer: a preliminary report

- Comparison of diagnostic and prognostic performance of two assays measuring thymidine kinase 1 activity in serum of breast cancer patients

- Evaluation of the BRAHMS Kryptor® Thyroglobulin Minirecovery Test in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma