Abstract

Embolic protection devices were developed to reduce the risk of stroke during carotid artery stenting. The aim of this study was to test the capture efficiency of five embolic protection devices under reproducible in vitro conditions. The setup consisted of silicone tubes representing the vessel modeling round and oval cross sections. Spherical polystyrene particles (150 μm, COOH-coating) were used to simulate the plaque. The particles were inserted in a clean water circuit and either captured by the device or collected in a glass filter. The missed particles were counted by laser obscuration as a measure of device leakage. The systems Angioguard RX, RX Accunet, FiberNet, FilterWire EZ and EmboshieldNAV were analyzed. At the round cross section, FilterWire EZ demonstrated the highest capture efficiency (0% of missed particles) and RX Accunet the lowest, at 34%. The amount of leaked particles increased to 22% for FilterWire EZ and 89% for Angioguard RX during the test with the oval cross profile.

Introduction

Carotid artery occlusive disease leading to stroke is one of the leading causes of death in the United States and Europe. While carotid endarterectomy is still the treatment of choice, carotid artery stenting (CAS), as a less invasive method, has become a valuable treatment option [1, 6].

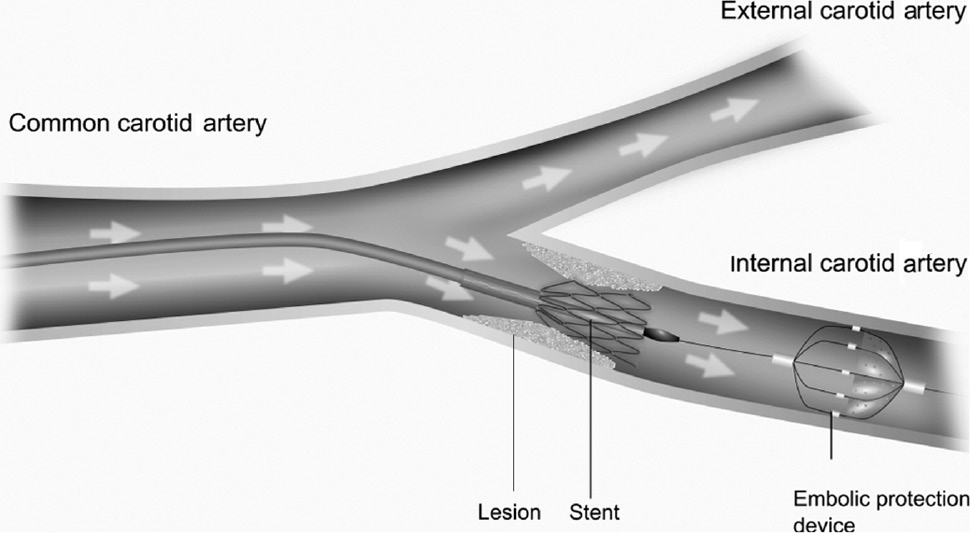

Systems for embolic protection are usually applied during dilatation and implantation of stents in the carotid artery. The purpose is to avoid the movement of parts of the arterial plaque that can come off during the intervention. In cases where these parts reach the vessels of the brain, they can lead to vascular occlusion and increase the risk of a stroke. Embolic protection devices (EPDs) have the function of catching the plaque material and keeping it during the intervention. As shown in Figure 1, they are placed distal to the stent in the internal carotid artery (ICA) [14]. Although the use of EPDs during CAS intuitively suggests advantages, there is no clinical randomized trial showing a statistical meaningful difference [10].

Scheme of stent implantation in the internal carotid artery using an embolic protection device.

There are already results of other experimental studies that show differences between the EPDs (e.g. [15]). These studies vary in test setups, tested systems and used particles.

In this study, several systems are tested to estimate their efficiency in capturing the particles not only in circular but also in oval cross sections of the vessel. In this way, a more realistic direct comparison of efficiency of EPDs under objective non-ideal conditions is provided.

Materials and methods

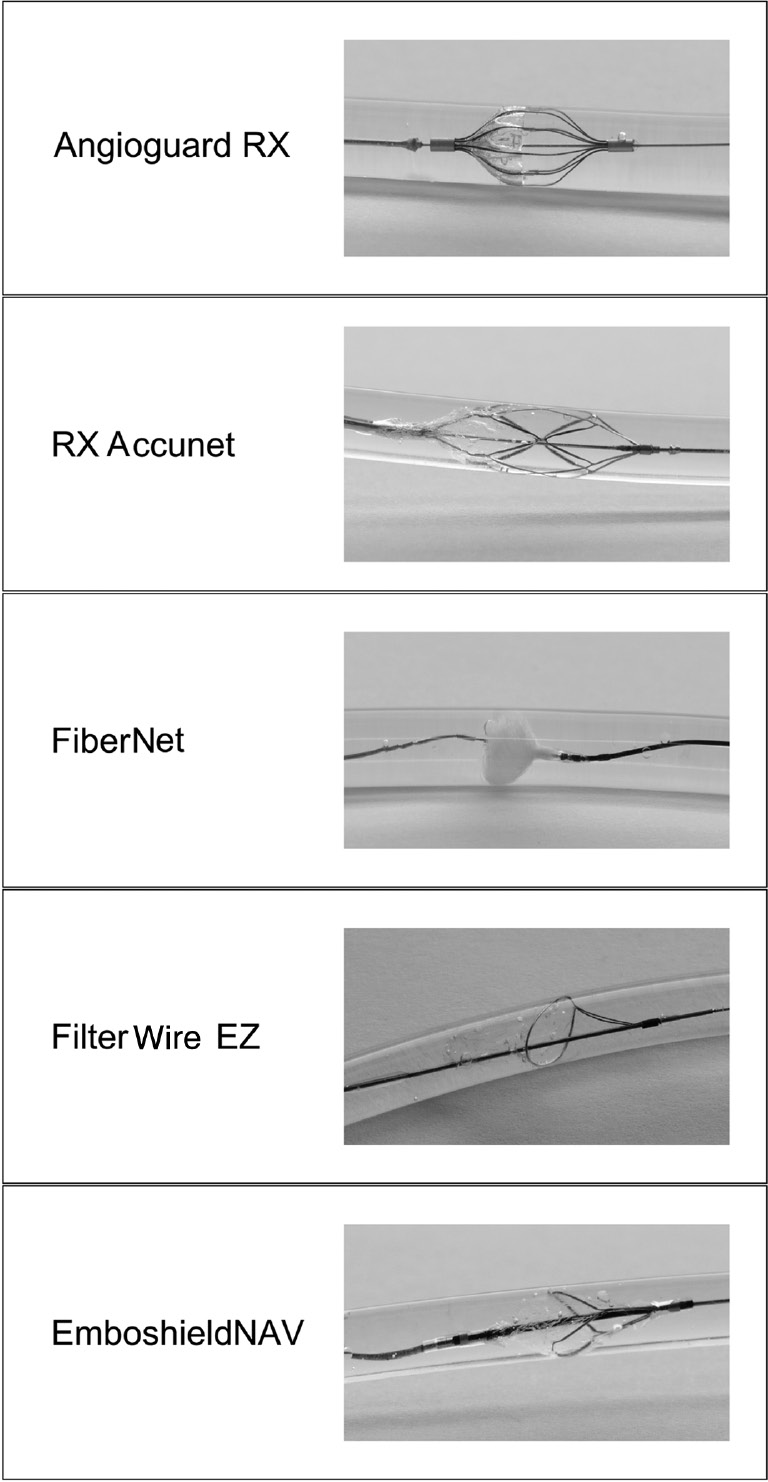

The efficiency of five different embolic protection systems was tested. They consist of a guide wire and a mechanism to catch particles in a filter. They have a pore size between 40 μm and 115 μm. Table 1 shows the devices and their properties [3, 4, 5, 8, 12].

Tested embolic protection systems.

| Name | Producer | Pore size | Recommended vessel size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angioguard RX | Cordis, Milpitas, CA, USA | 100 μm | 4.5–5.5 mm |

| RX Accunet | Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA | 115 μm | 5.0–6.0 mm |

| FiberNet | Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA | 40 μm (equivalent) | 5.0–6.0 mm |

| FilterWire | Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA | 110 μm | 3.5–5.5 mm |

| EmboshieldNAV | Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA | 120 μm | 4.0–7.0 mm |

In Figure 2, the tested EPDs are shown expanded in a tube filled with water.

Images of the tested embolic protection systems.

The test setup was built based on a test setup assembled and evaluated in a previous study [11]. All EPDs were tested in a vessel model (see Figure 3) that consisted of silicone tubes with an inner diameter (ID) of 5 mm (mean diameter of the ICA [9]). The volume flow rate of 942 ml/min was generated by a peristaltic pump (Watson Marlow, Wilmington, MA, USA 323 S/D, three pump heads). It was calculated considering the systolic flow rate in the ICA [9]. The systolic flow rate was chosen to simulate maximum flow as the worst case in carotid arteries. It can be assumed that high flow rates may compromise the filter architecture and, thus, reduce efficiency. The flow rate and the pressure were measured during the test. Clean water was used as a test medium.

Test setup for the forward flow direction.

A reservoir, consisting of a glass bottle with a volume of 150 ml, contained spherical particles (micromer, d=150 μm, polystyrene, surface modified with carboxyl group (COOH) surface, micromod Partikeltechnologie GmbH, Rostock, Germany) in a phosphate buffer saline (PBS) buffer solution to simulate detached plaque particles. Thus, the particle diameter was larger than the maximum filter pore size of each EPD being tested. The regular spherical shape of the particles enables correct counting and size measurement.

To collect the particles missed by the system, an inline filter made of sintered glass with a pore size of 40 μm was used.

The spherical particles were added in advance to an 80-ml PBS buffer solution in each particle reservoir. The concentration was measured by a particle counter (according to USP 788, HIAC ROYCO 9703, Beckmann Coulter GmbH, Krefeld, Germany). The vessel model was cleaned for 10 min before the testing of each device to ensure that no particles other than the test particles would be collected. The inline filter and the particle reservoir were integrated immediately before starting the test. Then, the first system was implanted in the marked region of the vessel model (implantation site) according to the individual instructions for use over the arterial sheath and proximally fixed with a torquer. The flow was started and the particles were washed out of the reservoir. To make sure that all particles come into the circuit, the suspension in the reservoir was homogenized by a magnetic stirrer.

After 5 min, all particles were flushed through the EPD and the flow was stopped. The inline filter was removed (filter sample 1). Then, the system was pulled back carefully and parked in the tube in front of the introduction sheath. The tube system was carefully changed to the assembly seen in Figure 4 without losing any liquid. Then, the test setup was washed backwards for 5 min so that particles that could not be kept by the system while pulling it backwards were collected at the inline filter 2. After 5 min, the flow was stopped and the inline filter (filter sample 2) was removed. Both inline filters were washed with ethanol and water and the suspension was kept for analysis of particulate matter.

Test setup for the inversed flow direction.

For the next test with an oval vessel, the assembly shown in Figure 1 was realized with a new particle reservoir and a clean inline filter and the system was implanted in the same position as in the first test. The cross section of the tubes in the filter region was modified from the original circular to an oval by outer mechanic compression. The diameter of the segment was reduced to 80% of the original diameter (ID=4 mm). The oval profile was chosen to simulate a geometrically defined deformation of the vessel. The test was repeated with the same parameters as before and the system was removed completely with the help of the recovery catheter after removing inline filter 1, changing the assembly and integrating inline filter 2. The inline filters were washed with ethanol and water and the suspension was kept. Table 2 shows the test procedure.

Test process of each system.

| Step 1 | Curved vessel | Insertion of particles after implantation |

| Step 2 | Curved vessel | Backflow after retraction |

| Step 3 | Oval vessel | Insertion of particles after implantation |

| Step 4 | Oval vessel | Backflow after retraction |

The particle concentration in the suspensions was measured as described before. The procedure was repeated for each EPD being tested. Additionally, the procedure was performed three times without a device to prove that no particles were lost in the tube system itself and vice versa that all particles could be recovered.

Results

The particle reservoirs contained between 2000 and 4000 particles before the insertion of the EPD.

The particle count value of the test without an EPD is the average of three single measurements and shows that no particles remain in the tubing. The recovery of more than 100% of inserted particles, as seen in Figures 5 and 6, is caused by statistical variations during the particle counting process, in which several samples of a probe were taken to calculate the particle concentration as a mean value. As expected, there are no particles found with the inversed flow direction (respective after retraction) because all particles were caught by the inline filter after the insertion of the particles.

Results of the particle counts in a curved vessel behind the EPD and after retraction of the EPD in % of the inserted particles.

Results of the particle counts in an oval vessel before insertion, behind the EPD and after retraction of the EPD in % of the inserted particles, *discarded.

The recovery of particles behind each EPD in a curved but circular vessel is shown in Figure 5, normalized by the amount of actually inserted particles. The measured value represents the leakage of particulates. It differs between 70% (Cordis Angioguard RX) and 0% (FilterWire EZ). The amount of missed particles for the other systems is 34% for RX Accunet, 1% for FiberNet and 32% for EmboshieldNAV. The recovery after the retraction of the system is a measure of particulate loss during system retraction. It is lower than 10% except for FiberNet and Emboshield NAV. The results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 6 shows that the amount of particles that pass the EPD is higher in an oval vessel than in a curved vessel. The amount of leaked particles provides values between 89% (Cordis Angioguard RX) and 22% (FilterWire EZ). The amount of missed particles for the other systems is 53% for RX Accunet, 55% for FiberNet and 34% for EmboshieldNAV.

Twenty-five percent of the particles are caught after the retraction of the system at maximum with the inversed flow. In the case of FilterWire EZ, the results of inversed flow testing were discarded because of an accidental handling error.

During the test with the implanted EmboshieldNAV system in the curved and the oval vessels, the pressure rose higher than 1 bar and exceeded the pressure resistance of the test setup. The test was continued with a lower flow rate for a shorter time period. There were no particles found in the reservoir after the test, so it was suggested that all particles passed or were caught by the implanted device. For the other systems, the pressure rose by about 200–300 mbar compared to the pressure without any implanted system. This increase of pressure is not expected to occur in clinical practice because higher flow in collateral vessels would compensate for this effect.

Discussion

The technical setup for the presented in vitro study of EPDs was based on literature but was improved to overcome some limitations. It was the general aim to use a reproducible and technically well-described setup.

In contrast to other studies [13, 15], no bifurcation anatomy was simulated. Using a single vessel model guarantees that all introduced particles pass the measuring path with a placed EPD. The chosen flow rate, as derived from physiological data, was measured directly as no flow split could occur.

The influence of a pulsatile flow on the capture efficiency of the EPD has not been proven [16] in the past. So the flow rate was held constant. The amount of volume flow rate was selected considering the mean flow rate in the ICA [9] during the systolic phase. It is higher than the volume flow rate in precedent studies, so the stress on the EPDs is maximal [4, 6, 13, 15]. The higher flow rate results in a higher pressure across the EPD and can be seen as an additional challenge.

The definition and use of only one particle size has the advantage of reducing the risk of particle agglomeration [7]. This effect could be effectively avoided as only particles 150 μm in diameter were counted and the numbers of introduced and recovered particles were in the same range.

The particle diameter is higher than the largest pore size of the EPD. This circumstance ensures that the particles cannot pass the EPD through the pores and the results give an indication about the wall apposition of the device. Compared to the injection of the particle suspension with a syringe, the insertion by a particle reservoir and the continuous homogenization with a stirrer has the advantage that all particles actually come into the circuit.

The measurement method of particle recovery differs from those in other studies (microscopic [6] or weighing [13]). The counting of the particles in the particle reservoir before the test and in the inline filter with a particle counter is a validated method. The result of the particle recovery without an EPD in the test setup shows that the process of washing out the particles of the inline filter does not leave any particles behind.

The results show that FilterWire EZ had the highest capture efficiency in a curved and an oval vessel (0%, 22%, respectively). The result for the round cross profile is in good accordance with previous studies (1%, 4%, 1%) [6, 13, 15]. The good capture efficiency might be reasoned by the filter geometry [15].

The capture efficiency of RX Accunet (34% of missed particles) was measured to be lower than in previous studies. There, the amount of particles found behind the system was lower than 10% [4, 6]. That might suggest that the wall apposition in the actual test was worse because of higher deformation of the device, reasoned by higher flow rate or higher pressure.

The EPD EmboshieldNAV showed an amount of 35% of missed particles after injection in a previous test [15]. This value matches with the one found in our study (32%). Also, it must be considered that the test time was smaller than that for the other systems because the pressure was higher than 1 bar.

For Angioguard RX, the amount of missed particles was higher than in the studies (70% vs. 4%–36%) that used larger or less-defined particles. But in other studies, this type of EPD has the lowest particle capture efficiency as well [6, 13, 15].

In a curved vessel with a round profile, FiberNet captured more than 99% of the inserted particles. This is more than in a previous study (94%) [16]. But the amount of missed particles increased by about more than 55% for the oval vessel. This shows that especially for this system, the capture efficiency depends on the profile of the vessel. This relation and the comparison between the results for the capture efficiency on a curved and an oval vessel are shown in Figure 7.

Comparison between the missed particles by the EPD in a curved and an oval vessel model.

The amount of missed particles was higher for each device during the implantation in the oval vessel model. That shows that more particles can pass the EPD through the gap between the system and the vessel wall when the vessel is oval. It increased from 70% to 89% for Angioguard RX and from 34% to 54% for RX Accunet. FilterWire EZ kept all particles in a curved vessel but missed 22% in the oval vessel. So the decline of the wall apposition in the deformed vessel led to an augmentation of missed particles of 20% for those three systems. The difference for EmboshieldNAV is smaller with an increase of only 2%.

Asymmetries of real calcified neck vessels are supposed to decrease wall apposition of filter devices by forming gaps between the system and the vessel wall. This effect will depend on the grade of deformation and calcification and is assumed to reduce particle capture efficiency. The FilterWire device had low percentages of leaked particles for the round and oval cross profiles of the vessel model. This system is able to adapt to different cross profiles, which can also be reasoned for more complex vessels. The FiberNet system, with its extremely flexible fibers, would also perfectly adapt; however, the device missed more than 50% of the particles in an oval vessel. The FiberNet design with more and longer fibers would probably improve particle capture efficiency. Further investigations are necessary to assess the different design principles in more detail.

Although there is no clear evidence for using protection devices in CAS, many physicians keep on using such devices to minimize the risk of embolism. Taking a closer look at the different types of protection devices, the EPD has the advantage that it is very simple to use with no interruption of an antegrade blood flow [6, 10]. The results in these and in previous studies assume the use of FilterWire EZ as an EPD when patients have a higher risk for embolization, i.e. in case of soft tissue plaques [2, 6, 16].

Limitations

The recovery of particles after retraction is influenced by the test procedure where the flow is stopped to pull the system back. During the application of an EPD in a human body, the flow is continuously present and particles would not probably get lost this way.

The particle size was chosen to be large enough to ensure that the missed particles leaked through the gap between the system and the vessel but not through the pores. But there might be differences in the wall apposition of the device in a silicone tube and in a human vessel, reasoned by differences in the surface structure and the stiffness. The study can only give an indication of how the devices will work in an asymmetric narrowed vessel because the chosen cross profile was symmetric in both cases.

Each test of the particle recovery behind the EPD in a curved or an oval vessel was only performed once so that there is no statement about statistical variations.

Conclusion

The test setup allows a good comparison between different EPDs with regard to capture efficiency in a standardized surrounding. The implantation in the model and the counting of missed particles after injection shows the quality of the wall apposition. Because of the increase of missed particles in the deformed vessel, it can be concluded that the behavior in a real vessel depends on the individual anatomical conditions. Concerning the chosen test setup and parameters, FilterWire EZ has the highest capture efficiency.

References

[1] Andresen R, Roth M, Brinckmann W. Outpatient primary stent-angioplasty in symptomatic internal carotid artery stenoses. Zentral Chir 2003; 128: 703–708.10.1055/s-2003-42745Search in Google Scholar

[2] Biasi GM, Froio A, Diethrich EB, et al. Carotid plaque echolucency increases the risk of stroke in carotid stenting: the imaging in Carotid Angioplasty and Risk of Stroke (ICAROS) study. Circulation 2004; 110: 756–762.10.1161/01.CIR.0000138103.91187.E3Search in Google Scholar

[3] Boston Scientific. FilterWire EZ: Embolic Protection System for carotid artery; 2016. Available from: URL:http://www.bostonscientific.com/en-US/products/embolic-protection/filterwire-ez-embolic-protection-system.html [cited 2016 Feb 19].Search in Google Scholar

[4] Charalambous N, Jahnke T, Bolte H, Heller M, Schäfer PJ, Müller-Hülsbeck S. Reduction of cerebral embolization in carotid angioplasty: an in-vitro experiment comparing 2 cerebral protection devices. J Endovasc Ther 2009; 16: 161–167.10.1583/08-2355.1Search in Google Scholar

[5] Cordis. Katalog Cordis Emboli Protection Device: ANGIOGUARD® RX Emboli Capture Guidewire System Product Page; 2016. Available from: URL:http://pdf.medicalexpo.de/pdf-en/cordis/angioguard-r-rx-emboli-capture-guidewire-system-product-page/71108-153612.html [cited 2016 Feb 19].Search in Google Scholar

[6] Finol EA, Siewiorek GM, Scotti CM, Wholey MH, Wholey MH. Wall apposition assessment and performance comparison of distal protection filters. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15: 177–185.10.1583/07-2272.1Search in Google Scholar

[7] Ho Chi Anh. Modellierung der Partikelagglomeration im Rahmen des Euler/Lagrange-Verfahrens und Anwendung zur Berechnung der Staubabscheidung im Zyklon. Halle (Saale): Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg 2004 Jan 27.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kao J. Emboshield NAV 6 Embolic Protection System 510 (k) summary FDA: Abbott Vascular; 2014. Available from: URL:http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf12/K121015.pdf [cited 2016 Feb 18].Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kopp H, Ludwig M. Checkliste Doppler- und Duplexsonografie. 4th ed., Stuttgart; New York: Georg Thieme Verlag 2012.10.1055/b-001-2169Search in Google Scholar

[10] MacDonald S. New embolic protection devices: a review. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2011; 52: 821–827.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Matthies J, Kurzhals A, Schmidt W, et al. Test setup for characterizing the efficacy of embolic protection devices. Current Directions in Biomedical Engineering 2015; 1: 454–457.10.1515/cdbme-2015-0109Search in Google Scholar

[12] Medtronic. FiberNet Embolic protection system: Technical specifications; 2013. Available from: URL: http://www.peripheral.medtronicendovascular.com/international/product-type/carotid-package/fibernet/technical-specifications/index.htm [cited 2016 Feb 19].Search in Google Scholar

[13] Müller-Hülsbeck S, Jahnke T, Liess C, et al. In vitro comparison of four cerebral protection filters for preventing human plaque embolization during carotid interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2002; 9: 793–802.10.1177/152660280200900612Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ohki T, Roubin GS, Veith FJ, Iyer SS, Brady E. Efficacy of a filter device in the prevention of embolic events during carotid angioplasty and stenting: an ex vivo analysis. J Vasc Surg 1999; 30: 1034–1044.10.1016/S0741-5214(99)70041-8Search in Google Scholar

[15] Siewiorek GM, Wholey MH, Finol EA. In vitro performance assessment of distal protection devices for carotid artery stenting: effect of physiological anatomy on vascular resistance. J Endovasc Ther 2007; 14: 712–724.10.1177/152660280701400517Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Siewiorek GM, Wholey MH, Finol EA. In vitro performance assessment of distal protection filters: pulsatile flow conditions. J Endovasc Ther 2009; 16: 735–743.10.1583/09-2874.1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Efficiency test of current carotid embolic protection devices

- Influence of sizes of abutments and fixation screws on dental implant system: a non-linear finite element analysis

- Biomechanical evaluation of novel ultrasound-activated bioresorbable pins for the treatment of osteochondral fractures compared to established methods

- Fabrication of multifunctional CaP-TC composite coatings and the corrosion protection they provide for magnesium alloys

- An experimental study of shear-dependent human platelet adhesion and underlying protein-binding mechanisms in a cylindrical Couette system

- The influence of implant body and thread design of mini dental implants on the loading of surrounding bone: a finite element analysis

- RapidNAM: generative manufacturing approach of nasoalveolar molding devices for presurgical cleft lip and palate treatment

- Enamel shear bond strength of different primers combined with an orthodontic adhesive paste

- Biomechanical analysis of stiffness and fracture displacement after using PMMA-augmented sacroiliac screw fixation for sacrum fractures

- Regular research articles

- An investigation of the effects of suture patterns on mechanical strength of intestinal anastomosis: an experimental study

- Relationship between linear velocity and tangential push force while turning to change the direction of the manual wheelchair

- Analysis of voluntary opening Ottobock Hook and Hosmer Hook for upper limb prosthetics: a preliminary study

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Efficiency test of current carotid embolic protection devices

- Influence of sizes of abutments and fixation screws on dental implant system: a non-linear finite element analysis

- Biomechanical evaluation of novel ultrasound-activated bioresorbable pins for the treatment of osteochondral fractures compared to established methods

- Fabrication of multifunctional CaP-TC composite coatings and the corrosion protection they provide for magnesium alloys

- An experimental study of shear-dependent human platelet adhesion and underlying protein-binding mechanisms in a cylindrical Couette system

- The influence of implant body and thread design of mini dental implants on the loading of surrounding bone: a finite element analysis

- RapidNAM: generative manufacturing approach of nasoalveolar molding devices for presurgical cleft lip and palate treatment

- Enamel shear bond strength of different primers combined with an orthodontic adhesive paste

- Biomechanical analysis of stiffness and fracture displacement after using PMMA-augmented sacroiliac screw fixation for sacrum fractures

- Regular research articles

- An investigation of the effects of suture patterns on mechanical strength of intestinal anastomosis: an experimental study

- Relationship between linear velocity and tangential push force while turning to change the direction of the manual wheelchair

- Analysis of voluntary opening Ottobock Hook and Hosmer Hook for upper limb prosthetics: a preliminary study