Abstract

We conduct a real-effort laboratory experiment to examine how disclosure of information about the pay received by co-workers affects work performance in Germany and China. We employ an individual piece-rate setting in which a piece rate is received for each unit of output successfully produced. We find that receiving information that one’s co-workers are all receiving the same piece rate as oneself has no significant effect on performance compared to non-disclosure. In contrast, learning that one co-worker is receiving a higher piece rate than oneself does significantly affect performance. In particular, receiving such information initially results in a larger performance increase than receiving information that others are all receiving the same piece rate as oneself. However, this performance gap decreases toward the end of the experiment.

Acknowledgements

The authors like to thank Xuejun Jin, J. Atsu Amegashie and Daniel Houser for their valuable suggestions and comments. Xiaolan Yang is grateful to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project NO.71303210), the National Social Science Fund of China (Project No.10zd&034) and the 985 Project of Zhejiang University for financial support.

References

Abeler, J., S.Altman, S.Kube, and M.Wibral. 2010. “Gift Exchange and Workers’ Fairness Concerns: When Equality Is Unfair.” Journal of the European Economic Association8(6):1299–324.10.1162/jeea_a_00026Suche in Google Scholar

Akerlof, G. A., and J. L.Yellen. 1990. “The Fair Wage-Effort Hypothesis and Unemployment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics105(2):255–83.10.2307/2937787Suche in Google Scholar

Angelova, V., W.Güth, and M.Kocher. 2012. “Co-Employment of Permanently and Temporarily Employed Agents.” Labour Economics19(1):48–58.10.1016/j.labeco.2011.06.017Suche in Google Scholar

Bartling, B. 2011. “Relative Performance or Team Evaluation? Optimal Contracts for Other-Regarding Agents.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization79:183–93.10.1016/j.jebo.2011.01.029Suche in Google Scholar

Bartling, B., and F.von Siemens. 2011. “Wage Inequality and Team Production: An Experimental Analysis.” Journal of Economic Psychology32(1):1–16.10.1016/j.joep.2010.09.008Suche in Google Scholar

Bartol, K. M., and D. C.Martin. 1988. “Effects of Dependence, Dependency Threats, and Pay Secrecy on Managerial Pay Allocations.” Journal of Applied Psychology74:105–13.10.1037/0021-9010.74.1.105Suche in Google Scholar

Bierman, L., and R.Gely. 2004. “Love, Sex, and Politics? Sure. Salary? No Way: Workplace Social Norms and the Law.” Berkley Journal of Law and Employment25:167–91.Suche in Google Scholar

Burchett, R., and J.Willoughby. 2004. “Work Output When Knowledge of Different Incentive System Varies: Reports from an Economic Experiment.” Journal of Economic Psychology25(5):591–600.10.1016/S0167-4870(03)00066-7Suche in Google Scholar

Burroughs, J. D. 1982. “Pay Secrecy and Performance: The Psychological Research.” Compensation Review14:44–54.10.1177/088636878201400305Suche in Google Scholar

Camerer, C., L.Babcock, G.Loewenstein, and R.Thaler. 1997. “Labor Supply of New York City Cabdrivers: One Day at a Time.” Quarterly Journal of Economics112(2):407–41.10.1162/003355397555244Suche in Google Scholar

Card, D., A.Mas, E.Moretti, and E.Saez. 2012. “Inequality at Work: The Effect of Peer Salaries on Job Satisfaction.” American Economic Review102:2981–3003.10.1257/aer.102.6.2981Suche in Google Scholar

Charness, G., and P.Kuhn. 2007. “Does Pay Inequality Affect Worker Effort? Experimental Evidence.” Journal of Labor Economics25(4):693–724.10.1086/519540Suche in Google Scholar

Clark, A., D.Masclet, and M. C.Villeval. 2010. “Effort and Comparison Income.” Industrial & Labor Relations Review63(3):407–26.10.1177/001979391006300303Suche in Google Scholar

Clark, A., and A.Oswald. 1996. “Satisfaction and Comparison Income.” Journal of Public Economics61(3):359–81.10.1016/0047-2727(95)01564-7Suche in Google Scholar

Cohn, A., E.Fehr, B.Herrmann, and F.Schneider. 2011. “Social Comparison in the Workplace: Evidence from a Field Experiment.” Technical report, University of Zurich, IZA Discussion Papers.10.2139/ssrn.1778894Suche in Google Scholar

Crawford, V., and J.Meng. 2011. “New York City Cab Drivers’ Labor Supply Revisited: Reference-Dependent Preferences with Rational-Expectations Targets for Hours and Income.” American Economic Review101:1912–32.10.1257/aer.101.5.1912Suche in Google Scholar

Day, N. 2007. “An Investigation Into Pay Communication: Is Ignorance Bliss?” Personnel Review36(5):739–62.10.1108/00483480710774025Suche in Google Scholar

Demougin, D., C.Fluet, and C.Helm. 2006. “Output and Wages with Inequality Averse Agents.” Canadian Journal of Economics39(2):399–413.10.1111/j.0008-4085.2006.00352.xSuche in Google Scholar

Edwards, M. 2005. “The Law and Social Norms of Pay Secrecy.” Berkeley Journal of Empirical and Labor Law25:41–67.Suche in Google Scholar

Englmaier, F., and A.Wambach. 2010. “Optimal Incentive Contracts Under Inequity Aversion.” Games and Economic Behavior69:312–28.10.1016/j.geb.2009.12.007Suche in Google Scholar

Eurostat Statistics. 2012. The European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). Luxembourg: Eurostat.Suche in Google Scholar

Farber, H. 2008. “Reference-Dependent Preferences and Labor Supply: The Case of New York City Taxi Drivers.” American Economic Review98(3):1069–82.10.1257/aer.98.3.1069Suche in Google Scholar

Fehr, E., and K. M.Schmidt. 1999. “A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics114(3):817–68.10.1162/003355399556151Suche in Google Scholar

Fischbacher, U. 2007. “Z-Tree: Zurich Toolbox for Ready-Made Economic Experiments.” Experimental Economics10(2):171–8.10.1007/s10683-006-9159-4Suche in Google Scholar

Futrell, C. M., and O. C.Jenkins. 1978. “Pay Secrecy Versus Pay Disclosure for Salesmen: A Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Marketing Research15:214–19.10.1177/002224377801500204Suche in Google Scholar

Gächter, S., and C.Thöni. 2010. “Social Comparison and Performance: Experimental Evidence on the Fair Wage-Effort Hypothesis.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization76(3):531–43.10.1016/j.jebo.2010.08.008Suche in Google Scholar

Gely, R., and L.Bierman. 2003. “Pay Secrecy/Confidentiality Rules and the National Labor Relations Act.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Labor and Employment Law6:120–56.Suche in Google Scholar

Geng, H.. 2010. “Experimental Studies on Cross-Cultural Behaviour between Germans and Chinese.” University of Bonn, Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Greiner, B., A.Ockenfels, and P.Werner. 2011. “Wage Transparency and Performance: A Real-Effort Experiment.” Economics Letters111(3):236–8.10.1016/j.econlet.2011.02.015Suche in Google Scholar

Güth, W., M.Königstein, J.Kovács, and E.Zala-Mezõ. 2001. “Fairness Within Firms: The Case of One Principal and Many Agents.” Schmalenbach Business Review53:82–101.10.1007/BF03396629Suche in Google Scholar

Hennig-Schmidt, H., and Z.Li. 2006. “On Power in Bargaining: An Experimental Study in Germany and the People’s Republic of China.” Nankai Business Review2006, 9(2):31–38 (in Chinese with English abstract).Suche in Google Scholar

Herrmann, B., C.Thöni, and S.Gächter. 2008. “Antisocial Punishment Across Societies.” Science319:1362–7.10.1126/science.1153808Suche in Google Scholar

Itoh, H. 2004. “Moral Hazard and Other-Regarding Preferences.” Japanese Economic Review55(1):18–45.10.1111/j.1468-5876.2004.00273.xSuche in Google Scholar

Koszegi, B., and M.Rabin. 2006. “A Model of Reference-Dependent Preferences.” Quarterly Journal of Economics50(4):1133–65.Suche in Google Scholar

Lawler, E. E. 1967. “Secrecy About Management Compensation: Are There Hidden Costs?” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance2:182–9.10.1016/0030-5073(67)90030-XSuche in Google Scholar

Leventhal, G. S., J.Karuza, and W. R.Fry. 1980. “Beyond Fairness: A Theory of Allocation Preferences.” In Justice and Social Interaction-Experimentation and Theoretical Research From Psychological Research, edited byG.Mikula, 167–218. New York: JAI Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lind, E. A., and K.Van den Bos. 2002. “When Fairness Works: Toward a General Theory of Uncertainty Management.” In Research in Organizational Behaviour, edited by B. M. Staw and R. M. Kramer, Vol. 24, 181–223. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.10.1016/S0191-3085(02)24006-XSuche in Google Scholar

Milgrom, P., and J.Roberts. 1992. Economics, Organizations, and Management. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.Suche in Google Scholar

Nosenzo, D. 2013. “Pay Secrecy and Effort Provision.” Economic Inquiry51(3):1779–1794.10.1111/j.1465-7295.2012.00484.xSuche in Google Scholar

Rey-Biel, P. 2008. “Inequity Aversion and Team Incentives.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics110(2):297–320.10.1111/j.1467-9442.2008.00540.xSuche in Google Scholar

Survey and Research Center for China Household Finance. 2012. A Report on Income Inequality. Chengdu, China: Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.Suche in Google Scholar

- 1

Burchett and Willoughby (2004) is an exception. Their experiment was conducted in the United Arab Emirates.

- 2

The exchange rate between Yuan RMB and Euro was around 9–10 at the time when the experiment was conducted.

- 3

For example, in task A the computer screen presented a series of numbers: “12, 10, 18, 54, 52, 60, 180, ___”. Subjects were required to calculate the number after “180” according to the pattern revealed by the previous numbers. The relationship between the consecutive numbers is as follows: 12−2 = 10, 10+8 = 18, 18×3 = 54, 54–2 = 52, 52+8 = 60, 60×3 = 180. The algorithm repeated here is subtracting 2, adding 8, and multiplying by 3. Therefore, the right answer is 178 (180–2 = 178). In task B, the computer screen presented a series of letters, such as “H C D E K Q”, and subjects were required to arrange these letters in alphabetical order. Thus, the correct answer is “C D E H K Q”.

- 4

Instructions are available from the authors upon request.

- 5

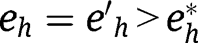

In an appendix, available from the authors upon request, we analyze this model more formally in a game-theoretic framework. We show there that when a Nash equilibrium such that

and

and  exists, that equilibrium is unique. However, if there is a Nash equilibrium such that

exists, that equilibrium is unique. However, if there is a Nash equilibrium such that  and

and  , other Nash equilibria may also exist for some parameter values. In those Nash equilibria,

, other Nash equilibria may also exist for some parameter values. In those Nash equilibria,  and

and  such that

such that  Note that in any such equilibrium

Note that in any such equilibrium  . In the appendix, we also show that any such equilibrium is Pareto inferior to the equilibrium where

. In the appendix, we also show that any such equilibrium is Pareto inferior to the equilibrium where  and

and  .

. - 6

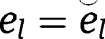

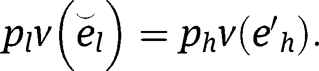

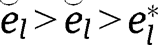

In an appendix, available from the authors upon request, we analyze more formally a game-theoretic model with both disadvantageous and advantageous inequities in the utility functions of both the h and the l players. We show there that if, for a set of parameter values, a Nash equilibrium in which l’s monetary income is below h’s monetary income exists, that equilibrium is unique with

. However, if, for a set of parameter values, a Nash equilibrium in which l’s monetary income equals h’s monetary income exists, there will in general be multiple equilibria. In all of those equilibria, l’s monetary income will equal h’s monetary income. Thus, in such equilibria, neither player is receiving disutility from any form of inequity. Any such equilibria for which the incomes of l and h are between l’s self-interested maximum level of income,

. However, if, for a set of parameter values, a Nash equilibrium in which l’s monetary income equals h’s monetary income exists, there will in general be multiple equilibria. In all of those equilibria, l’s monetary income will equal h’s monetary income. Thus, in such equilibria, neither player is receiving disutility from any form of inequity. Any such equilibria for which the incomes of l and h are between l’s self-interested maximum level of income,  , and h’s self-interested maximum level of income,

, and h’s self-interested maximum level of income,  , are not Pareto-rankable. This is because being closer to

, are not Pareto-rankable. This is because being closer to  is better for l, while being closer to

is better for l, while being closer to  is better for h. In all such equilibria,

is better for h. In all such equilibria,  , qualitatively the same prediction as is given by the equilibrium where

, qualitatively the same prediction as is given by the equilibrium where  . However, it is also possible that equilibria for which the incomes of l and h are equal exist outside of this range. We show in the appendix that any equilibrium in which the equal income levels of l and h are below

. However, it is also possible that equilibria for which the incomes of l and h are equal exist outside of this range. We show in the appendix that any equilibrium in which the equal income levels of l and h are below  will be Pareto-dominated by an equilibrium where the incomes of both l and h are equal to

will be Pareto-dominated by an equilibrium where the incomes of both l and h are equal to  . This is because there are no inequity considerations in either equilibrium since incomes are equal in both cases. However, at

. This is because there are no inequity considerations in either equilibrium since incomes are equal in both cases. However, at  , both l and h are closer to their self-interested maxima. Analogously, any equilibrium at an income level above

, both l and h are closer to their self-interested maxima. Analogously, any equilibrium at an income level above  will be Pareto-dominated by an equilibrium where the incomes of both l and h are equal to

will be Pareto-dominated by an equilibrium where the incomes of both l and h are equal to  . We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting we analyze the multiple equilibria that can arise in the case of both disadvantageous and advantageous inequities.

. We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting we analyze the multiple equilibria that can arise in the case of both disadvantageous and advantageous inequities. - 7

As in Bartling (2011), if the cost of effort is partially but not completely accounted for in assessing disadvantageous inequity, low-piece-rate participants would increase their effort levels relative to uninformed participants but not by as much as if the sole concern was a monetary-income comparison.

- 8

We also examine differences in average performance between high-piece-rate and low-piece-rate participants in a panel-data regression framework with clustered errors for each participant, analogous to the framework introduced below for comparing the performance of low-piece-rate participants among the different treatments. Despite a lack of statistical power owing to the small number of high-piece-rate participants, the results are consistent with the Mann–Whitney results. For Germany, they indicate no performance differences between high- and low-piece-rate participants. For China, they show a significantly lower increase in performance over time for the high- than for the low-piece-rate participants. These results are not reported here to save space, but are available from the authors upon request.

- 9

We thank two anonymous referees for this observation.

- 10

As a robustness check, we also ran the same regressions using two slightly different methods to account for the lack of independence across periods for each participant: in one, we used random effects for each participant and in the other we used a combination of both random effects and error clustering by participant. The coefficients are identical for each method, while the standard errors differ slightly. There are no qualitative differences in any of the statistical inferences obtained by any of the three methods.

- 11

The tests on both countries combined reported in Table 4 are done by first running a regression for both countries combined, clustering the errors by participant. A dummy variable for country is used and interacted with each of the independent variables. To save space, the results of the regression itself are not reported here, because they are identical to the reported results of the regressions run separately for Germany and China. However, the hypothesis tests reported in Table 4 are based on this regression for both countries combined.

- 12

In the first five periods, the intercept for the UPRI treatment is Constant + Infotrmt + Upri. In the last five periods, the intercept for the UPRI treatment is Constant + Infotrmt + Upri + Lasthalf + Infotrmt × Lasthalf + Upri × Lasthalf. The difference between the intercept in the last versus the first five periods is Lasthalf + Infotrmt × Lasthalf + Upri × Lasthalf = 2.05 − 1.24 + 3.41 = 4.22.

- 13

In the first five periods, the intercept for the EPRI treatment is Constant + Infotrmt. In the last five periods, the intercept for the EPRI treatment is Constant + Infotrmt + Lasthalf + Infotrmt × Lasthalf. The difference between the intercept in the last versus the first five periods is Lasthalf + Infotrmt × Lasthalf = 2.05 − 1.24 = 0.81.

- 14

In the first five periods, the slope of the trend line for the UPRI treatment is equal to Period + Infotrmt × Period + Upri × Period. In the last five periods, the slope of the trend line for the UPRI treatment is equal to Period + Infotrmt × Period + Upri × Period + Lasthalf × Period + Info × Lasthalf × Period + Upri × Lasthalf × Period. The difference between the slope of the trend line in the last versus the first five periods is Lasthalf × Period + Info × Lasthalf × Period + Upri × Lasthalf × Period = −0.37 + 0.11 − 0.49 = −0.75.

- 15

In the first five periods, the slope of the trend line for the EPRI treatment is equal to Period + Infotrmt × Period. In the last five periods, the slope of the trend line for the UPRI treatment is equal to Period + Infotrmt × Period + Lasthalf × Period + Info × Lasthalf × Period. The difference between the slope of the trend line in the last versus the first five periods is Lasthalf × Period + Info × Lasthalf × Period = −0.37 + 0.11 = −0.26.

- 16

As in Footnote 12, the difference between the intercept in the last versus the first five periods for the UPRI treatment is Lasthalf + Infotrmt × Lasthalf + Upri × Lasthalf. For China, this equals 2.71 + 0.48 + 3.45 = 6.64.

- 17

As in Footnote 13, the difference between the intercept in the last versus the first five periods for the EPRI treatment is Lasthalf + Infotrmt × Lasthalf. For China, this equals 2.71 + 0.48 = 3.19.

- 18

As in Footnote 14, the difference between the slope of the trend line in the last versus the first five periods for the UPRI treatment is Lasthalf × Period + Info × Lasthalf × Period + Upri × Lasthalf × Period. For China, this equals –0.59–0.16–0.50 = –1.25.

- 19

As in Footnote 15, the difference between the slope of the trend line in the last versus the first five periods for the EPRI treatment is Lasthalf × Period + Info × Lasthalf × Period. For China, this equals –0.59–0.16 = –0.75.

©2013 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin / Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Advances

- When Does Inter-School Competition Matter? Evidence from the Chilean “Voucher” System

- Investment, Dynamic Consistency and the Sectoral Regulator’s Objective

- Contributions

- Vertical Contracts and Mandatory Universal Distribution

- Ticket Pricing and Scalping: A Game Theoretical Approach

- Loyalty Discounts

- Age, Human Capital, and the Quality of Work: New Evidence from Old Masters

- Effects of the Endogenous Scope of Preferentialism on International Goods Trade

- Fiscal Decentralization and Environmental Infrastructure in China

- Declining Equivalence Scales and Cost of Children: Evidence and Implications for Inequality Measurement

- Political Parties, Candidate Selection, and Quality of Government

- Professors’ Beauty, Ability, and Teaching Evaluations in Italy

- Pass-through of Per Unit and ad Valorem Consumption Taxes: Evidence from Alcoholic Beverages in France

- The Tuesday Advantage of Politicians Endorsed by American Newspapers

- Topics

- The Effects of Medicaid Earnings Limits on Earnings Growth among Poor Workers

- Opportunities Denied, Wages Diminished: Using Search Theory to Translate Audit-Pair Study Findings into Wage Differentials

- Horizontal Mergers, Firm Heterogeneity, and R&D Investments

- Product Differentiation and Consumer Surplus in the Microfinance Industry

- The Multitude of Alehouses: The Effects of Alcohol Outlet Density on Highway Safety

- Solving the Endogeneity Problem in Empirical Cost Functions: An Application to US Banks

- The Internet, News Consumption, and Political Attitudes – Evidence for Sweden

- A Cross-Cultural Real-Effort Experiment on Wage-Inequality Information and Performance

- Are Students Dropping Out or Simply Dragging Out the College Experience? Persistence at the Six-Year Mark

- The Welfare Effects of Location and Quality in Oligopoly

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Advances

- When Does Inter-School Competition Matter? Evidence from the Chilean “Voucher” System

- Investment, Dynamic Consistency and the Sectoral Regulator’s Objective

- Contributions

- Vertical Contracts and Mandatory Universal Distribution

- Ticket Pricing and Scalping: A Game Theoretical Approach

- Loyalty Discounts

- Age, Human Capital, and the Quality of Work: New Evidence from Old Masters

- Effects of the Endogenous Scope of Preferentialism on International Goods Trade

- Fiscal Decentralization and Environmental Infrastructure in China

- Declining Equivalence Scales and Cost of Children: Evidence and Implications for Inequality Measurement

- Political Parties, Candidate Selection, and Quality of Government

- Professors’ Beauty, Ability, and Teaching Evaluations in Italy

- Pass-through of Per Unit and ad Valorem Consumption Taxes: Evidence from Alcoholic Beverages in France

- The Tuesday Advantage of Politicians Endorsed by American Newspapers

- Topics

- The Effects of Medicaid Earnings Limits on Earnings Growth among Poor Workers

- Opportunities Denied, Wages Diminished: Using Search Theory to Translate Audit-Pair Study Findings into Wage Differentials

- Horizontal Mergers, Firm Heterogeneity, and R&D Investments

- Product Differentiation and Consumer Surplus in the Microfinance Industry

- The Multitude of Alehouses: The Effects of Alcohol Outlet Density on Highway Safety

- Solving the Endogeneity Problem in Empirical Cost Functions: An Application to US Banks

- The Internet, News Consumption, and Political Attitudes – Evidence for Sweden

- A Cross-Cultural Real-Effort Experiment on Wage-Inequality Information and Performance

- Are Students Dropping Out or Simply Dragging Out the College Experience? Persistence at the Six-Year Mark

- The Welfare Effects of Location and Quality in Oligopoly