Abstract

The online digital sphere has recently witnessed a rapid growing of amateur audiovisual translation, which not only reinvigorates the current body of translation scholarship but also calls for a paradigm shift from the entrenched monolingualism. Though a plethora of studies have been conducted on fansubbing, little is known about blogger subtitling. Drawing on the netnographic data from a subtitling video blogger, @暴躁鸭仔 (baozao yazai, Grumpy Duckling for English) on a microblogging site (Weibo) in the mainland of China, we explored trans-translating by examining the translanguaging involved in the blogger’s subtitling translation. It is revealed that the blogger makes a hybrid, integrated use of multiple semiotic, orthographic, discursive and modal resources, without being confined by the boundaries amongst nameable languages, or linguistic/non-linguistic codes. The orchestration of the unified heterolingual repertoire builds up a social-media translanguaging space, wherein the tensions between translation and translanguaging due to distinct conceptual schemas are manipulated to yield synergy insofar as they dovetail into ingenious language making. We concluded that such creative translation can be retheorized as a process of trans-translating to encapsulate the subtitling experience in light of its dynamic and fluid nature, and transformative power of translanguaging. The results of this research might add to the picture of amateur subtitling and translation and that of translanguaging as well as their relation to one another.

1 Introduction

The democratization of digital technology (Beseghi 2021) and the ready accessibility of audiovisual contents (Díaz-Cintas 2018) have recently given birth to the thriving of diverse subtitling undertaken by net users who have no professional trainings. Of these Internet-enabled, amateur-dominated audiovisual translation phenomena, blogger subtitling is the latest surfacing form of grassroots online subtitling on Chinese microblogging site Weibo. The “technological affordances” (Zhang and Ren 2020, p. 5) provided by this social media platform facilitate a passionate involvement of more blog posters in the alternative, free-of-charge production of subtitled materials from the authentic foreign videos, through which those videos could survive screening regulations and Internet censorship before their delivery to the audience. Compared with its successful and influential predecessor fansubbing (fan subtitling), which features close-knit bonds and team collaboration (Lu and Lu 2021), blogger subtitling distinguishes itself by a kind of utterly individual, self-sustaining operation mode. This unique working pattern, as we can imagine, renders the emerging subtitling-based mediation idiosyncratically rich, bringing into focus the subtitlers’ agency and subjectivity. In this regard, this hitherto untouched subtitling practice merits in-depth study. Furthermore, the highly personalized and flexible language use, along with the multimodal nature of audiovisual materials, necessitates new approaches beyond the conventional text-to-text linguistic analysis.

Such an approach may fall on a newly developing theory of multilingualism, namely, translanguaging. Evolved from a pedagogical approach in the education context, translanguaging now refers to a fluid and dynamic practice whereby bi/multilinguals exploit a multiplicity of semiotic resources—encompassing scriptal, visual, and digital—for creative and critical meaning-making (García and Li 2014; Li 2018a; Li and García 2017; Li and Zhu 2019). The term “translanguaging” arose out of the reconceptualization of language as “a multisensory and multimodal semiotic system interconnected with other identifiable but inseparable cognitive systems” (Li 2018a, p. 20; emphasis in original). Within a translanguaging frame, language users tap into a single linguistic repertoire with features heretofore constrained by different societies and histories. And during such integrated utilization of diverse sense-making resources, a translanguaging space (Li 2018a) emerges, which, acting as a social site for creativity and criticality, contributes to the blurring of the boundaries between politically-defined languages and language varieties. From this point of view, the translanguaging lens can be easily mapped onto the cyber subtitling practices performed by bloggers who, benefited from the openness and inclusiveness of social media platforms, exploit and stretch the semiotic resources available to them (Pérez-González 2012).

Given the above, we took the theoretical apparatus of translanguaging to examine this new form of amateur subtitling on Weibo—blogger subtitling, zooming on its creative, dynamic sense-making process. Adopting a netnography with @暴躁鸭仔(baozao yazai, Grumpy Duckling for English), a subtitling blogger on Weibo, we collected screenshots of her subtitled videos together with data from online interviews and field notes to build a small corpus. Through qualitative analysis, this article explored the dynamic, fluid nature of the simultaneous engagement of varied linguistic, semiotic, orthographic, discursive, and modal elements so as to illustrate the transformative power of translingual and transcultural negotiation in “trans-translating”.

2 Literature review

2.1 Translanguaging: a theoretical lens for translation

The term translanguaging, derived from the Welsh trawsieithu, was coined by Cen Williams (1994, 1996 to delineate a pedagogical practice in bilingual classrooms where the instructional language for input (listening or reading) is different from that for output (speaking or writing). This Welsh-English translation is attributed to Baker (2001), who discussed in his textbook four potential values of translanguaging in developing both languages and content learning. Given its original use in the education domain, translanguaging has been deployed from the very start to fathom bilinguals’ language practices from a heteroglossic rather than monoglossic perspective, to examine whether this kind of multilingual teaching arrangements of integrating all the features of students’ linguistic repertoire can boost their bilingual literacy, academic achievements and metalinguistic awareness (e.g., Canagarajah 2011; Creese and Blackledge 2010a; García and Sylvan 2011; Hornberger and Link 2012; Williams 2012). In the wake of these pioneering academics, the concept of translanguaging is broadened to mean an ongoing process whereby language users harness what is called linguistic repertoire, irrespective of politically named languages, for sense-making, effective communication, and knowledge construction (Li 2018a). With the conceptual evolution of translanguaging, scholars apply it to research settings other than the classroom, probing how multilinguals translanguage to communicate as well as display subjectivities in superdiverse social life (e.g., Blackledge and Creese 2017; Creese and Blackledge 2010b; Li 2011a). Apart from all these, lines of research on linguistic landscape and visual semiotics have made use in a holistic and interdisciplinary vein of the conceptualization of translanguaging, adding to the knowledge of, among many others, the dynamics of individual signs in translingual cityscape (Gorter and Cenoz 2015), and the complex semiotic transference in visual art installations (Lee 2015). Apparently, translanguaging proves illuminating for reflections on the translingual realities in multilingual contexts of education, everyday interaction, and linguistic/semiotic landscape. This paper thus proposes to mesh translanguaging theory with translation studies that likewise calls upon flexible and strategic language use.

Admittedly, translanguaging and translation are seemingly incompatible in the sense that the former destabilizes the boundary between nameable languages, whereas the latter is respectful for and subject to it. Suffice to say that each translation activity prerequisites a definite idea of what is the source language (SL) and what is the target language (TL). However, translation is deemed as a communicative practice that entails meaning-making and expression and that is performed by a bilingual/multilingual who works at the border between languages, putting to good use his creativity and criticality from time to time. This will awaken us to the reality that translanguaging can easily occur in translation, or, to put it the other way round, “translation can be an ideal space for translanguaging where a bilingual’s linguistic features are rigorously challenged by a purposeful creative force for communication” (Sato 2017, p. 15). Hence, a translanguaging lens can shed light on various heterolingual translation phenomena, which has been corroborated in a handful of research.

As exemplified in Creese et al.’s (2018) case study on the construction of social difference through the interactions of a couple who run a butcher’s in Birmingham, UK, translation and translanguaging, serving as salient apparatus for business, both indicate social difference and produce communicative overlaps across the spatial realms of the city. Rock (2017) even related translanguaging to the ethical issues regarding translation and interpreting practices. Rejecting the previously alleged monolingual norm, the author appealed for a consensus among practitioners and scholars about the complexity of multilingual communication in this superdiverse society so as to forge “a more honest and thus ethico-moral” (ibid., p. 231) working environment for interpreters and translators. In audiovisual translation and multimodality, Tomei and Chetty (2021) scrutinized translanguaging strategies employed by analyzing intersemiotic translation in the cinematic adaptations of two African novels, where they foreground the role translanguaging approaches play in generating communicative discrepancy as well as macro-textual modifications. There is one other point worth emphasizing that translanguaging, given its incorporation of “all meaning-making modes” (García and Li 2014, p. 29), can also lend insights into translated texts as instanced by a series of studies conducted by Eriko Sato, who reported on the artifacts of translanguaging in translation of Japanese mimetics (2017), furigana (2018), and heterolingual pun (2019).

A glimpse into the theoretical venation of translanguaging and its application to translation helps reveal the validity and feasibility of connecting translanguaging lens with translation phenomena. On top of that, due to its transdisciplinary nature, it is crucial for translanguaging to free itself from the spectrum of education (Li and García 2017), supplying inspiration instead to other neighboring disciplines like translation studies. Existing research of this sort, however, is numerically scarce on the one hand, and analytically and systematically immature on the other, with many topics including, among others, translator’s motivation, skopos, subjectivity, and identity left untouched.

2.2 Translanguaging space: social media

Translanguaging space, as conceptualized by Li (2018a, p. 23), refers to “a space that is created by and for Translanguaging practices”, a venue witnessing language users’ transgressing of the artificial boundaries amongst named languages and linguistic and non-linguistic meaning-making resources. The very act of translanguaging contributes to integration of language users’ personal trajectories, ideologies, cognitive abilities, and the like, insofar as breeding a kind of “transformative power” (ibid.) in the translanguaging space. Acting as a locale with dynamics and fluidity, a translanguaging space gives into full play multilinguals’ creativity—observing or breaching the norms of linguistic behaviors, and breaking the dividing lines drawn between nameable languages, as well as criticality—utilizing available evidence to question given knowledge and articulate viewpoints (Li 2011a, 2011b).

The diversity of translanguaging space, or its inclusiveness for hybrid signifying constituents can readily find resonance with social media, which, facilitated by advanced digital technologies and globalized cultural flows, “allow the creation and exchange of User Generated Content” (Kaplan and Haenlein 2010, p. 61) and afford “new affordances for creative language use that goes beyond the traditional practices” (Li and Lee 2021, p. 133). Seen from this angle, social platforms fuel assembling of written scripts, emoji, pictures, and other communicative resources, thus opening opportunities for translanguaging. And since, in the words of Li and García (2017, p. 237), “translanguaging such as in texting, blogging, social media, gaming” constitutes a critical research area, of significance is applying the perspective and theory of translanguaging to social networking sites, which are ready for in-depth study with voluminous materials.

Up to date, this orientation has been paid attention to. Zhao and Flewitt (2020), for instance, focused on the way young Chinese immigrant children leverage multilingual, multisemiotic, and multimodal resources as they communicate with friends and family members on social media platforms. With nine immigrant families in London as research participants, they illustrated the emergent translanguaging practices of these immigrant children when using a popular social software WeChat, problematizing the idea of languages as discrete systems and thereby proving social media could facilitate translanguaging, exchanges, and language learning. Another pertinent study was conducted by Li and Huang (2021), who analyzed the dynamic translanguaging practices of an overseas Chinese student on WeChat based on his Moments posts, chat transcripts, and online and offline interviews. Their sociolinguistic case study concluded that the young overseas student musters his linguistic repertoire to construct and perform fluid and heterogeneous identities in a self-created virtual translanguaging space on WeChat. Moreover, Schreiber (2015) provided an empirical account of the translingual writing behaviors of a Serbian student on Facebook, delving into how a rich mix of language varieties, images and videos works on the molding of his online identity and on the attaining of his communicative goals within a linguistically diverse community.

The above review attests to the scholarly attempt made by a couple of researchers to investigate the creative translanguaging practices and the consequent identity-founding on social media. Their main concerns, however, go to the daily communication of transnational students on a few social networking sites (e.g., WeChat and Facebook), with less attention paid to other types of English (e.g., Twitter and Instagram) and non-English (e.g., Weibo, QQ, and Baidu Tieba) platforms alike and different kinds of language practices like online self-generated subtitling, which leaves ample room for further studies.

2.3 Blogger subtitling: a new amateur subtitling

The second generation of the Internet, i.e., Web 2.0, together with the resultant User Generated Content (UGC) and so-called participatory culture, had sounded the death knell of the time “when a single set of subtitling conventions sufficed to inform the interlingual and intercultural mediation practices of a relatively homogeneous group of professionals who worked almost exclusively for the film and television industries” (Pérez-González 2007, p. 67). Instead, in today’s media landscape of globalization and digitalization, an increasing number of network users without professional backgrounds are embarking on subtitling tasks that used to be a monopoly of specialized personnel.

Understandably, confronted with the deficiency and strict censorship of foreign films and teleplays, individuals who are of little formal training but equipped with some bilingual competence, and more importantly, enthusiasm for foreign cultures, have engaged in voluntary translation of audiovisual materials with subtitles in their mother tongue. This type of Internet-born, amateur-led subtitling practices, or amateur subtitling, has played an “intercultural brokerage role” (Pérez-González 2012, p. 336) between different sociolinguistic systems and epitomized “the subversion of consolidated practices from mainstream subtitling” (Pérez-González 2007, p. 71), whereby garnering broad interest from academic circles, especially audiovisual translation (AVT) studies. Varied facets of the subtitling practices by non-professionals have been detailed, say, the strategies and techniques used in amateur subtitling (Caffrey 2009; Luque 2018), the problems impinging on subtitling quality (Bogucki 2009; Sajna 2013), the audience reception of non-professional subtitles (Orrego-Carmona 2016), and the function amateur subtitlers perform in globally networked media industry and democratization of mainstream discourses (Pérez-González 2012, 2013).

Among these subtitling-based forms of lingual-cultural mediation operated by amateurs, fansubbing—a blend of fan and subtitling—ranks the most visible and influential one. Benefiting from a power transfer from media authorities to active prosumers, namely consumers who “participate in the design, creation, and production” (Tapscott and Williams 2006, p. 125), groups of fans of Japanese anime or animated cinema worldwide produce and disseminate subtitled versions of audiovisual works, sharing their collaborative intelligence without expecting remuneration. Granted “an unlimited degree of altitude” (Pérez-González 2007, p. 71), fansubbers tend to utilize semiotic modes to the full and, in doing so, dethrone the orthodox conventions prevailing in professional subtitling then “maximize their own visibility as translators” (ibid., p. 76). The aforementioned distinguishing characteristics, along with its proliferation in cyberspace, have taken fansubbing to the forefront of amateur subtitling scholarship. A growing number of researchers have gravitated to this emerging yet complex subtitling paradigm, seeking, to name but a few, to present the working process and methodology and unique features of fansubbing (Díaz-Cintas and Muñoz Sánchez 2006; González 2007), to examine fansubbing beyond mere anime culture and the gaps in the mainstream, commercial subtitling filled by amateur fansubbing (Dwyer 2012), and to reveal the nature and implication of fan subtitling as well as the new mechanism of content distribution it sets up (Lee 2011).

It should be noted, however, that the conspicuity of fansubbing in today’s amateur subtitling practices and studies does not necessarily mean that all the subtitling activities occupying non-professionals invariably follow a collaborative, peer working mode. Vis-à-vis fansubbing where “teamwork and co-ordination are essential among the different members” (Díaz-Cintas and Muñoz Sánchez 2006, p. 50), there are subtitlers airing their audiovisual rendition on a likewise voluntary but completely individual basis, such as in the case of blogger subtitling, which, as stated earlier, refers to a newly-emerged self-subtitling phenomenon led by bloggers who dot social media landscape. This type of subtitling developed by blog posters, despite commonalities with other amateur counterparts, assumes rich idiosyncrasies and sociolinguistic overtones, hence warranting investigation. But to date, the literature on this problem is surprisingly sparse, except for a few studies which do not use the term blogger subtitling but at least think outside the fansubbing box. Explorations on danmaku subtitling, for example, paint a picture of a “random, individual behaviour or makeshift language solution” (Yang 2021, p. 2) by means of “live” comments overlaid onto the screen. Unlike fansubbing characterized by “quality-controlled group efforts and organized workflow” (ibid.), danmaku subtitling “enables wider and freer amateur participation in audiovisual translation” (Yang 2020, p. 271).

Sketching amateur subtitling informs the thriving of this translation phenomenon—especially its salient form fansubbing—in both the Internet zone and academic community. But regrettably, it is the prevailing of fansubbing that seems to have engaged scholarly attention exclusively to the collective dimension of non-professionals’ audiovisual transfer. Despite that a tiny minority have shifted their gaze from the subtitle production done by fan groups, “very little has been said on the subject of self-translation in online and digital contexts, specifically with regard to social media” (Desjardins 2019, p. 156). The very limited research makes it imperative to look into amateur subtitling practices with an alternative set of operating patterns and different features, among which blogger subtitling comes as a case in point.

3 Methodology

Considering blogger subtitling takes place on social networking websites, as well as the fluid and transient nature of non-professional mediation networks (Pérez-González 2010), we employ netnography (i.e., Internet ethnography), a promising methodological tool “for the cultural analysis of social media and online community data” (Kozinets et al. 2014, p. 262), with its usability verified in translation studies (Ameri and Khoshsaligheh 2020) and, more relevant to this investigation, amateur subtitling research (Li 2017). This section will give a brief account of how we, under established netnographic guidelines, juggle research fieldsite and participant selection, data collection and analysis, and ethical considerations.

3.1 Research fieldsite and participant

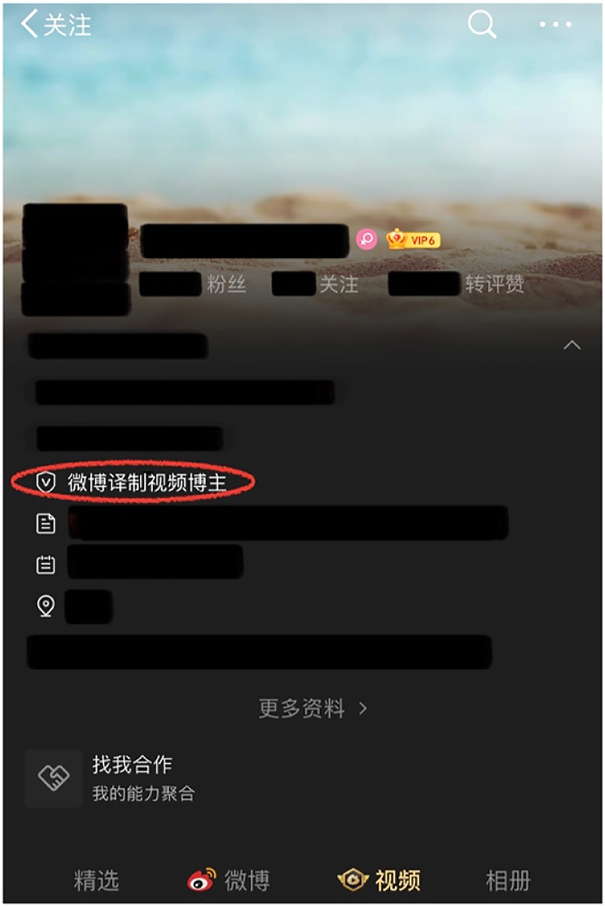

Our locating of research fieldsite is a two-step process. Since in netnographic inquiry, site choice should be based on the research topic and focus (Kozinets 2010), we first set our sights on Sina Weibo (Weibo for short), one of the biggest microblogging platforms in China, for its relevance to our research goal, i.e., to examine the phenomenon of blogger subtitling from a translanguaging perspective. Especially, on the one hand, Weibo provides its registered users with rich media uploads, ranging from texts, pictures, and graphical emoticons to music and micro-videos. This “multimodal Weibo” (Liu et al. 2019) constitutes an enabling environment for the users to make a combined and hybrid use of available linguistic and semiotic resources, from which acts of translanguaging naturally emerge. On the other, among video bloggers—a primary type of blog creators on Weibo—subtitling has started a new trend thanks to official approval and support, as well illustrated in the launching of account verification for “微博译制视频博主” (Weibo Subtitling Video Blogger) (see Figure 1), and the hashtag and topic of “#金牌译制#” (Golden Subtitling) (see Figure 2).1 As seen in Figure 2, the times of reading and discussion and the numbers of authors of the topic #金牌译制# speak volumes of the population and high-level participation of self-made subtitling on Weibo, which renders it a targeted site for our fieldwork.

The account verification of a Weibo subtitling video blogger.

The Weibo topic of “Golden Subtitling” (December 15, 2021).

With the relevant social media platform fixed, the next step was to “go site specific…concentrating on a small number of postings or a very constrained data set” (Kozinets et al. 2014). After browsing through the micro-videos posted with the hashtag #Golden Subtitling# and the Weibo homepages of active subtitling bloggers, we identified several potential Weibo accounts with research purpose-relevant contents. Drawing on the chat function of Weibo, we then sent personal messages to several video-blog producers to invite research participation. Eventually, one blogger replied in the affirmative, whose Weibo account therefore became the ultimate, small-scale yet data-rich fieldsite of this study.

The research participant @暴躁鸭仔 is a subtitling-cum-editing video blogger on Weibo with 120 thousand followers.2 Registering her Weibo account in 2018, she joined the ranks of subtitled video authors in early 2021. Out of a total of 109 video postings in her microblog page (as of December 15, 2021), 104 fall into the category of subtitled audiovisual products, and 95 are posted under #Golden Subtitling# hashtag. In the monthly-released list of quality subtitling bloggers (began in January 2021), her name appeared on the list of March, August, and September, recognized with the New Blogger Award. The general process of her subtitled video production covers collecting original materials on Tiktok, editing video clips based on topic, and composing subtitles, all completed on her own. Her subtitling practices constantly involve the innovative use of not only linguistic codes but other semiotic and modal resources. Altogether, @暴躁鸭仔 is a logical candidate for research participation on the grounds of her identity as a typical subtitling blogger and output of a high traffic of postings for data collection and analysis.

3.2 Data collection and analysis

“Crucial to the feasibility of netnography is the awareness of what can be treated as ‘data’” (Lu and Lu 2021, p. 3). Three forms of data, as Kozinets (2010) spells out, are available for collection in a netnographic study: 1) archival data, comprising pre-existing digital artifacts and web resources created by online users; 2) fieldnote data, consisting of notes inscribed by the researcher with the intension of recording and reflexing; and 3) elicited data, covering contents the researcher co-creates with the participants through social interaction. This guidance on data gathering also works for our netnographic inquiry. During a prolonged immersion in the ready-made (video) blog posts of the participant, we, through “several levels of filtering for relevance” (Kozinets 2010, p. 98), accumulated pertinent archival data in the form of screenshots to maintain their multimodal quality. Besides, since these so-called observational archived resources, though placed within easy access of netnographers, “are by no means a substitute for internal reflection” (Kozinets et al. 2014), we generated field notes when experiencing and socializing in the participant’s microblog space via liking, commenting, and participating in her Weibo fan group (without entry audit) in ways that obtained a contextualized and comprehensive understanding of the social media phenomenon. Moreover, to “improve the reliability and validity of the evidence through triangulation” (Lu and Lu 2021, p. 3), several online semi-structured interviews were incorporated into the research project to make sense of our observation and reflection. Also of note is that all these data were collected from a continuous probing which has lasted throughout the entire study until no new information was captured and saturation was reached.

An ample gathered and classified dataset moved us to the qualitative netnographic analysis. Aiming at organizing the variegated participant-observational products “into a rigorous, meaningful, and valuable form of research output” (Kozinets et al. 2014, p. 270), we, grounded in inductive and reflexive basics, approached the data in an iterative and multistage manner. First of all, given the video-heavy context of the study, we analyzed the screenshots (mainly of the participant’s subtitled audiovisual postings) as multimodal sociolinguistic resources by pondering not only the printed translation words but other meaning-making semiotics and modes. Apart from that, for the remaining textual data (the text contents and comments of her microblogs, and the interaction between members in her fan group), thematic analysis was adopted to extract interpretative themes from the participant’s language practices. And, echoing with the data collection procedure, our data analysis has been constantly updated whenever new resources emerged in compliance with the prescription of letting “ethnographic timing” unfold (Kozinets et al. 2014).

3.3 Ethical considerations

Granted, accessibility and auto-archiving—two hallmarks of netnography (Kozinets 2010; Kozinets et al. 2014)—bring about a low-cost and effortless access to prodigious amounts of online information, but this seemingly convenient and plentiful datastream may “open a Pandora’s box of ethical issues related to privacy, consent, and appropriate representation” (Kozinets et al. 2014, p. 265), which makes ethical considerations all the more tricky and pressing in netnographic exploration. Confronting this matter head-on, we have kept our research project under rigorous codes of ethics, mindful of the obligation to protect the human subject’s privacy, online presentation of identity, and copyright on her blog posts. After obtaining her consent to study participation, we enquired if we could use her online pseudonym, i.e. @暴躁鸭仔, or she needed an additional alias. Having been notified of our identities and purposes, she allowed a direct mention of her Weibo username in publication. Under the circumstances, we have always valued and defended her online presentation of identity without prying into or disclosing any information about her offline life. Aside from the above, the copyright of cyber resources constitutes an ethical problem of equal importance. Whilst information posted publicly online is accessible to anyone with an Internet connection, personal social-media accounts are rightly treated as “‘semi-private’ web spaces” (Kozinets et al. 2014, p. 269). From this standpoint, we sought permission to quote the participant’s microblog contents as well as interview materials in our research article.

4 Findings

4.1 Translanguaging in translation

In her subtitling practices, @暴躁鸭仔, as a highly computer-literate netuser benefiting from the multimodal affordance of digital technology, moves skillfully between semiotic codes, discourses, writing systems, and communicative modes to negotiate with and oftentimes manipulate the original audiovisual texts. Seen through a translanguaging lens, we put under scrutiny the screenshots of her subtitled video blogs, to elucidate her creative intermingling of multiple meaning-making resources.

4.1.1 Trans-semiotics: emoji usage

Emojis, referring to small digital images used to express ideas or concepts in computer-mediated communication (CMC), have penetrated networked online spaces, including the micro-blogosphere. With its inherent traits of being visually driven, semantically rich, and emotionally expressive (Miller et al. 2016), this pictographic mode of signification lends itself well to inventive meaning conveyance found in social media interaction as well as translanguaging maneuvers. It can be argued that emojis, outside the system of any particular language, inhere in a language user’s communicative repertoire and serve to stamp personality- and culture-specific colors on “otherwise monochrome networked spaces of texts” (Stark and Crawford 2015, p. 1). Regarding the participant’s subtitling practices, the employment of emoji also emerges as a defining feature, embodying her exploitation of multiple semiotic resources as a whole. Our close observation revealed that the blogger has embedded emojis in nearly every subtitle to 1) substitute words with icons, 2) amplify speech acts, and 3) heighten sentiments (see Table 1).

Three types of emoji usage.

| Figures |

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

Figure 5 |

| Types of emoji usage | Substituting words with icons | Amplifying speech acts | Heightening sentiments |

| Original soundtrack | throwback to when I dropped a spoon in someone’s butt crack | going super fast | oh my goodness |

| Translated subtitles | 想当年 我曾经把一个汤勺塞进某人的  缝里 缝里 |

开得特别快

|

我的天呀

|

Taking advantage of emoji’s visual resemblance to physical objects, as shown in Figure 3, the subtitler replaces the word “butt” in the original speech with an emoji of peach  based on its round shape and distinctive cleft. And in Figure 4, two dashing away emojis

based on its round shape and distinctive cleft. And in Figure 4, two dashing away emojis  are presented at the end of the Chinese subtitle text to magnify the very act of “driving fast” delivered through the original video. Moreover, Figure 5 illustrates the function of emoji to highlight emotional states as the face streaming in fear

are presented at the end of the Chinese subtitle text to magnify the very act of “driving fast” delivered through the original video. Moreover, Figure 5 illustrates the function of emoji to highlight emotional states as the face streaming in fear  conveys a feeling of intense excitement, which echoes the “emotional representations” (Zhang, 2021, p. 19) facilitated by translanguaging artifacts.

conveys a feeling of intense excitement, which echoes the “emotional representations” (Zhang, 2021, p. 19) facilitated by translanguaging artifacts.

Notwithstanding the expressional vividness resulting from an integration of text-based scripts and non-verbal cues, utilizing emoji in subtitle translation is prone to misconstrual since this kind of “nuanced, visually-detailed” (Miller et al., 2016, p. 259) semiotic resource is open to interpretation. True, the potential ambiguity looms, but at least concerning the instances captured in this research, the subtitles with emoji decoration are located in the diegetic space of the audiovisual narrative, thus ensuring the consistency of storytelling in both audio and visual layers; besides, the target audience on whom the interpretation of subtitles relies are “a specific audience niche” (Pérez-González, 2007, p. 68): active social media users who are not only willing but also able to decode the connotation carried by the emojis. We can therefore conclude that, thanks to the “intrinsic semiotic richness of audiovisual programs” (Díaz-Cintas, 2018, p. 129) and the likewise technology-savvy audience, the blogger translanguages to attain in her subtitling practices a coherent linguistic-semiotic whole.

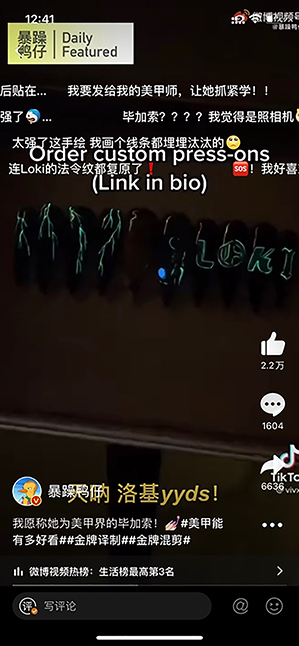

4.1.2 Trans-discourse: internet slang employment

In addition to facilitating a coordinated use of linguistic and non-linguistic codes across the semiotic barrier as analyzed earlier, translanguaging also catalyzes “multiple discursive practices” (García 2009, p. 45; emphasis in original) where language users mobilize elements from diverse discourses to mirror their knowledge and sociocultural surroundings and to make sense of their bi/multilingual worlds. Little wonder these flexible discursive experiments gradually find their way into the arena of the Internet, which, providing “a discursive web of discourse” (Zhang and Ren 2020, p. 4), accommodates complex discursive strategies deployed by online users to optimize their capabilities of meaning-making and articulation. Closely relevant to our study of blogger subtitling on social media sites, employing Internet slangs throws light on this encounter and interweaving of different discourses (see Table 2).

Internet slang employment.

Figure 6 |

|

|

|

|

| Original soundtrack | Oh my God, I’m obsessed! |

| Translated subtitle | 天呐 洛基 yyds! |

| Back translation | Oh my God, Loki is yyds! |

In the video clip, a manicurist feels so satisfied with her nail work with a hand drawing of the film role Loki on it that she says excitedly, “Oh my god, I’m obsessed!”. In the blogger subtitled version, this pleasant surprise is transferred with the use of a Chinese network buzzword “yyds”, the pinyin abbreviation of “永远的神” (yongyuan de shen), literally meaning “eternal God”. Originated from a compliment for an eSports player, this word has swept China’s cyberspace and ranked top 10 expressions on the Internet in 2021, used to show his/her feeling when one finds someone or something extraordinary, godlike and exceptional (China Daily 2021). Within a digital interaction context, “yyds” has its meaning discursively constructed, indexical of the online popular culture. For the blogger subtitler, social media platform opens a door for her to not only computer-born sociocultural variables but also creative discursive practices, which are identified as she transfers the localized usage of “yyds” to her onscreen interlingual engagement, whereby imbuing it with new expressive function.

Translanguaging in this example takes the form of a “discursive involvement process” (Creese et al. 2018, p. 2), pointing to a re-contextualization of a discourse into a new context. Along with the relocation of the Chinese netspeak “yyds” come the meeting and interaction of different discursive forces in the blogger’s subtitling practices, through which her personal understanding, environment, and identity get voiced.

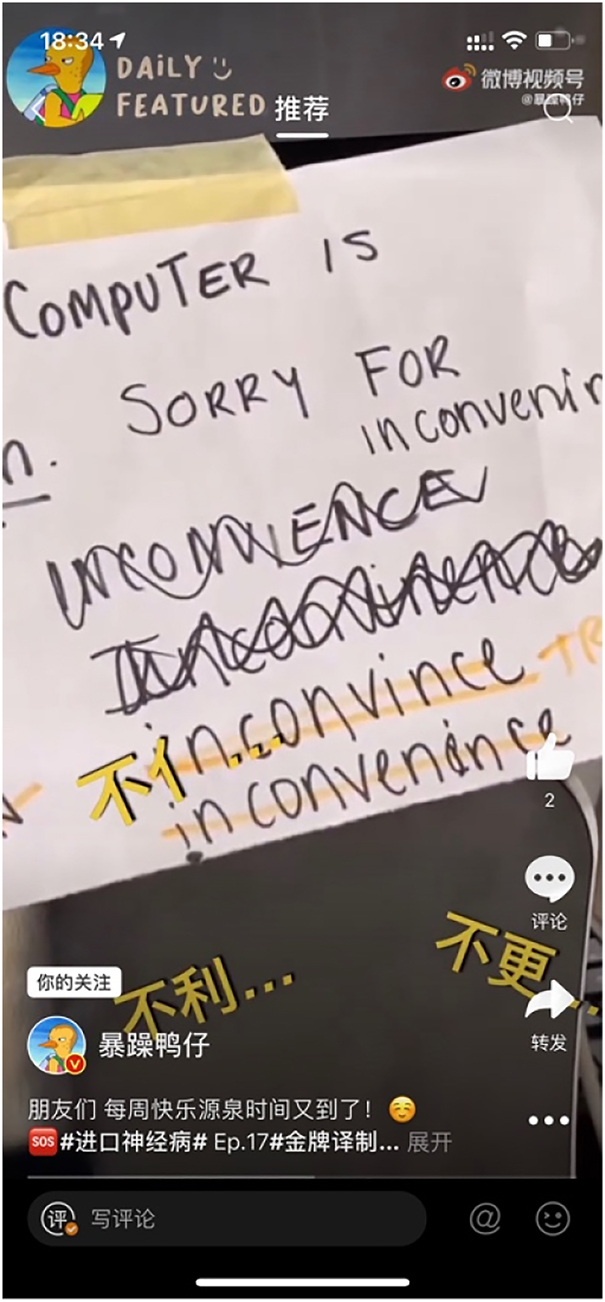

4.1.3 Trans-orthography: playful character formation

Among the novel subtitling strategies activated by the participant, the manipulation of orthographic features is particularly noteworthy and apt in our translanguaging framework. Figure 7 exemplifies how the translingual resourcefulness, together with the enabling new media environment, facilitates the blog subtitler to perform a playful operation as regards “the spatial-architectonic structure of Chinese characters and the aurality-orality of English letters” (Lee 2015, p. 447). As can be partially seen from the screenshot, written on the paper are: The computer is broken. Sorry for the inconvenience (trouble). But interestingly, the word “inconvenience” has been misspelled several times that had to be replaced by the less error-prone “trouble”, from which a humorous effect is produced. To translate this amusing spelling mistake will pose a challenge for the subtitler since, in contrast to the alphabetic writing system of English, Chinese characters are logographic in terms of orthography, which means a general separation between visual representation and pronunciation. Against this backdrop, the subtitler breaks out of the normative force of Chinese scriptal conventions to devise deconstructed characters. Specifically, she splits “不便利”, the Chinese equivalent to “inconvenience” into three parts, with “不” (the first character) combining respectively with “亻” (the pictograph-radical of “便”), “更” (the direct component of “便”), and “利” (the last character). In doing so, the subtitler mediates English phonetics with Chinese visuality as she transgresses the notion of what orthographically defines a language, thereupon resemiotizing the Chinese characters into an apparently illegitimate but de facto recognizable configuration.

Playful character formation.

Understood from a translanguaging lens, the participant’s re-creation of orthographic features acts as an example of language play for subverting China’s “uni-scriptal language ideology” (Li and Zhu 2019, p. 145), as displayed in a parallel case termed “Tranßcripting” (ibid.) concerning script production with heteroglossic writing elements. Amongst Chinese people circulates a perception that our logographic writing system, as an emblem of national heritage and identity, is of uniqueness hence should be strictly protected from breach. This long-upheld belief, however, has failed to extend its impact to the realm of social media, where the essential vibrancy and playfulness invite users to defy institutionalized rules and emancipate the hetero-lingual reality that has long been glossed over. As in the case under discussion, an increasingly active repertoire derived from the new media technology and expression equips the blog subtitler to transcend the standard framework of Chinese orthography. With the translanguaging mind and ability, she makes fun of the traditional scriptal pattern of Chinese, escaping its boundary through, to borrow Lee’s (2015, p. 451) term, “mock translation”.

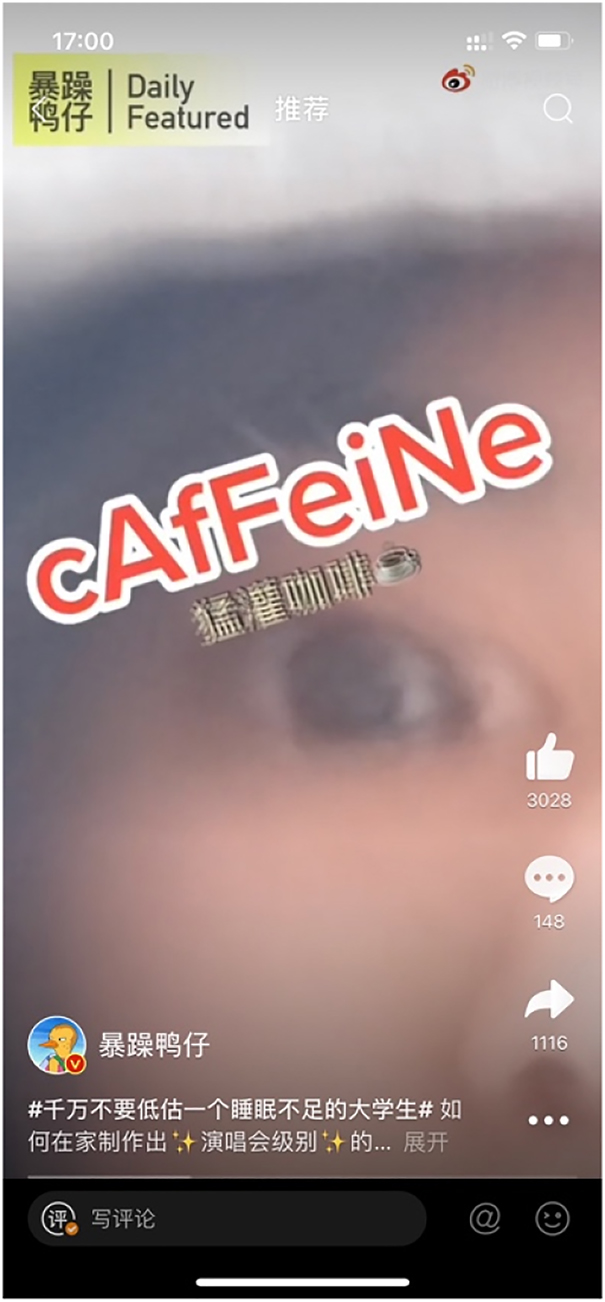

4.1.4 Trans-mode: multimodal subtitle presentation

It is a misalliance of previous linguistic theory with online subtitling practices in that the conventional equivalence-based creed is unable to keep pace with the multimodal nature of audiovisual products, and therein lies the reason why we turn to translanguaging. Translanguaging, positioned as a multimodal affair, seeks to cuts across the divides between geographically defined languages and language and other human sensory and cognitive capabilities. Then it will bring about a full unlocking of the potential for meaning construction, which does not solely resort to verbal semiotics, but also draws upon font style, spatial display, visual presentation, etc. (Li 2018b). Needless to say, this point of view indeed fits into our discussion of blogger subtitling, the practitioners of which have a wide range of sense-making modes at their disposal, including fonts, colors, position, and layout of subtitles.

A classic example is displayed below (see Figure 8). In this case, the Chinese subtitle “猛灌咖啡 ” (bolting down coffee

” (bolting down coffee ) is placed in the center of the frame, parallel to the original “cAfFeiNe”; additionally, a jiggling special-effect is adopted, which makes the subtitle blend with the shaking video picture. Thus with respect to visual representation, the subtitle witnesses an integration of written elements and non-linguistic features—positioning and visual effect.

) is placed in the center of the frame, parallel to the original “cAfFeiNe”; additionally, a jiggling special-effect is adopted, which makes the subtitle blend with the shaking video picture. Thus with respect to visual representation, the subtitle witnesses an integration of written elements and non-linguistic features—positioning and visual effect.

Multimodal subtitle presentation.

Vis-à-vis the official video captions, which are invariably put at the bottom of the screen in white color and static form, this kind of modified, living subtitles can affectively accentuate the narrative contained in the source audiovisual text, ultimately offering the viewers “an immersive spectatorial experience” (Pérez-González 2012, p. 347). With her creative and atypical exploitation of spatial layout and visual appearance of the subtitle, the participant brings an end to the consolidated norms prevailing in professional subtitling and further uncovers the multilingual and multimodal facts in audiovisual mediation. Here, translanguaging occurs as an intervention “in the articulation and reception of the audiovisual semiotic ensemble” (Pérez-González 2012, p. 335), contributing to fuzzing the erstwhile clear-cut confines between verbal and visual modes of signification.

4.2 A social-media translanguaging space

The preceding paragraphs serve as a detailed analysis of the translanguaging artifacts in @暴躁鸭仔’s subtitling acts, which are achieved by her resourceful orchestration of a multilingual, unified repertoire in which language in its traditional sense is only one. In what follows, based on the online interview material, our discussion will go to show how the subtitle translator’s leveraging of diverse linguistic, semiotic, and modal resources creates a social-media translanguaging space, within which the blog subtitler mediates between tension and synergy regarding translation and translanguaging (Baynham and Lee 2019); further, we coin a term “trans-translating” to encapsulate her dynamic audiovisual transfer, foregrounding its values in transcending the boundaries between narrowly-defined languages and in transforming the fixed norms of translation practice and language use.

4.2.1 Tension and synergy between translation and translanguaging

At first thought, as mentioned earlier, it is problematic to speak of translation and translanguaging in the same breath, given their distinct conceptual architectures. Prototypically speaking, translation is a material movement from a definable start (a prior, source text) to a definable finish (a subsequent, target text). Translanguaging, however, never entails a tangible outcome or set destination but, by its volatile nature, only concerns the simultaneous, ongoing interaction and interpenetration of diverse sense-making resources. Taken in this sense, the juxtaposition of translation and translanguaging will confront a translator with a tension that precludes the concurrent appropriation of disparate linguistic, semiotic and modal systems. Nevertheless, among creative and/or critical translational procedures may well dwell a translanguaging space which allows for a strategic negotiation “within a whirlpool of semiotic tension—repertoire” (Baynham and Lee 2019, p. 40) to materialize synergy. As for our probe into blogger subtitling, such translanguaging potentialities for translation are found in social networking sites where Web 2.0 opens up spaces for users to express their likes and ideas (Díaz-Cintas 2018).

Specific to the participant, when conducting subtitle translation of audiovisual materials featuring semiotic and modal hybridity, she is keenly aware of the tensions and conflicts between translanguaging tendency and translation ethics. This is evident in her insights into the relationship between multiple resources (linguistic, semiotic, modal) engaged in her subtitling practices.

| Researcher: 所以, 在这种情况下您想要翻译的是什么呢? 视频中的对话, 视频的情节, 还是视频的风格效果? (So what do you want to translate in this case? The dialogue, the plot, or the style and effect of the video?) |

| Participant: 我觉得最好还是能尽量还原, 但是如果不能达到, 那就按照这个顺序: 对话>情节>风格。因为情节和风格观众还可以通过视频画面去了解, 但对话就需要字幕这个媒介来传达。(I think it’s best to reproduce as much as possible, but if it cannot be achieved, follow this order: dialogue > plot > style. Because the plot and style can be understood by the audience through the video picture, but the dialogue needs to be conveyed via the medium of subtitles.) |

| Researcher: 那这种 “不能达到” 的情况多吗? (How often do you find “it can’t be achieved”?) |

| Participant: 会有。(Sometimes.) |

| Researcher: 在这种情况下需要结合不同的资源? (Is there a need to combine different resources on this occasion?) |

| Participant: 我觉得是的。(Yes, there is.) |

The participant clarifies in Excerpt 1 the collision between the potential “copresence, spontaneous interplay” (Baynham and Lee 2019, p. 36) of assorted meaning-making elements regardless of language confines and the utmost seriousness regarding language borders in prototypical translation philosophy. Involved in a linguistic transaction, she works on a model that values the perceived gaps between two language sides and depends on their resolution, that is, to find equivalence. At this point, her creativity and criticality as a translation agent lie with her ethical conforming to the translational nominalization, which runs counter to the sometimes-appearing need for unconventional, hybrid use of linguistic and sensory codes. Here, the tension between translation and translanguaging looms as homogeneous repertoires based on nameable languages integrate into a single, heterogeneous assemblage.

On the other hand, however, online social media platform, along with “the technology-driven ‘empowerment’” (Pérez-González 2007, p. 72), has turned subtitling into a channel of mediation and self-expression (Orrego-Carmona and Lee 2017). With this empowering and liberating context exists an overlapping zone between subtitle translation and online translanguaging for symbiosis and synergy. For the participant, the digital space of Weibo opens up a fluid translanguaging site that embraces creative and critical audiovisual transfer, as she said in our interview.

| Researcher: 那微博这个社交平台和您这种翻译形式和风格的形成有没有关系呢? (Is there any relation between the social media Weibo and your translation pattern and style?) |

| Participant: 有。受众、平台的调性等等都有考虑。(Yes, there is. The audience, the flavor of the platform, and so on are all taken into account.) |

| Researcher: 您觉得微博的调性是什么呢? (What do you think is the flavor of Weibo?) |

| Participant: 比较轻松娱乐向吧。(Relatively light-hearted and entertaining.) |

Excerpt 2 demonstrates the objective conditions offered by Weibo for the subtitle translator’s deployment of multiple meaning-making repertoires are not confined to linguistic ones. Characterized by a light-hearted and entertaining flavor, the social networking ecosystem celebrates “a relatively weak consciousness of the border” (Baynham and Lee 2019, p. 35; emphasis in original) and a “positive, comfortable and rewarding” (Zhang 2021, p. 21) climate as regards language use, and therefore enables translators to assert their agency. The result is that the participant mobilizes various modes of signification, including scriptal and visual resources in a dynamic and integrated fashion, bringing her creativity, criticality, cognitive capacity, reasoned response to the translational context “into one coordinated and meaningful performance” (Li 2011, p. 1223). Along the way emerges a social-media translanguaging space within which translation is embedded, entailing manipulation of the linguistic tension to realize synergy.

4.2.2 Trans-translating

From the above-stated tension and synergy between translation and translanguaging, we now take our analysis a stage further: to call the subtitle translation within a virtual translanguaging space “trans-translating”. As will become clear in the following part, it is a word-concept serviceable in reimagining translation as a dynamic, fluid process with transformative power other than merely a neat, static product. Translation, in its routinized sense, is a directional source-to-target, then-to-now movement labeled by the idea of temporal sequence (source-prior, target-subsequent). Yet from a fluid, translanguaging angle, extricated it from the temporal bounds, translation can be construed as a “moment-to-moment deployment of the multilingual repertoire” (Baynham and Lee 2019, p. 34). If so, the notion of time-succession, which underpins the conventional conceptual schema of translation, does not that matter; rather, the temporal nature of what we call trans-translating lies in the -ing grammatical aspect, indicating a work-in-progress mediation of diffuse linguistic and semiotic signs, discourses, modalities, personal experience, ideology, and identity without regard to time-based priority. As such, it displays a flux of translating regarding the participant’s cyber audiovisual transfer, which is therefore recognized as an on-going and generative condition that, in her own words, “一步一步调整” (adjusts step by step).

Using a translanguaging perspective to weaken the binary directionality and will-to-materiality entrenched in translation, however, is not meant to lay it in a vacuum, devoid of any realistic effect or outcome; instead, the trans-translating here proposed plays a transformative role in emancipating our traditional perception of subtitling and, by extension, translation and language use in a new online mediasphere. Just as García and Leiva (2014, p. 200) argue, what makes translanguaging unique is that “it is transformative, attempting to wipe out the hierarchy of languaging practices”. We thus take up this “trans” dimension to discuss how the subtitling blogger’s translating practices challenge and transform the present, thereby rejuvenating translation with new possibilities from a virtual space of translanguaging. An instantiation of the transformative potential can be seen in a kind of playful attitude and creative consciousness.

| Researcher: 您用桃子的 emoji 替换原文里的 butt, 为什么选择这样翻译呢? (Why do you choose to replace the original “butt” with an emoji of peach in your translation?) |

| Participant: 是想在字幕里加入一点网感吧。(I want to add a sense of network to the subtitles.) |

| Researcher: 这里的 “网感” 指什么呢? (What does “a sense of network” refer to?) |

| Participant: 我的理解呢, 就是对互联网内容创作的敏感度。通俗一点就是在玩梗。(I interpret it as the sensitivity to the creation of Internet contents. More colloquially, it means playing with memes.) |

In Excerpt 3, the participant gives the reasons for substituting written words with pictographic characters in subtitles. Evidently, her translation beliefs are not tied to the deep-rooted “conceptualization of subtitles as approximate linguistic representations” (Pérez-González 2012, p. 341). Rather than simply delivering accurate representations of the verbally-encoded source meaning, she plays with the multimodal resources and technological affordance in the digital platform, transcending the boundary of the written system to creatively intervene in the visual plan of the audiovisual text. Behind her amateur self-mediation, this playfulness and creativeness act as powerful forces to defy the translators’ effacement dominant in mainstream subtitling industry. And more significantly, through the release of her visibility as a subtitling agent and sensitivity to content creation, she provides an individualistic, bottom-up solution to audiovisual transfer, thus contributing to the “decentralisation and deregulation” (Díaz-Cintas 2018, p. 140) of the production and dissemination of networked narratives. In this regard, therefore, her translation practice finds its transformative strengths in its overstepping the boundaries, playfully subverting the norms, and breaking the subtitling hegemony.

Indeed, the transformative forces of the participant’s subtitling practices include but are not limited to the above-noted “playful subversion” (Li and Zhu 2019, p. 156) and creative initiative against settled normativity. Besides the hybrid use of linguistic and semiotic signs, her discursive subtitling experiments challenge the prevailing media discourse, manipulation of orthographic resources undermining the uni-scriptal language view, and exploitation of multiple modalities flouting the established subtitling norms, all of which exemplify the transformative aspect of the prefix trans-. During what we call trans-translating, these formerly separated meaning-making elements now meet and mesh into a single, heterolingual repertoire. By tapping into this unified, operating-as-one-whole gestalt (Ben-Rafael 2009), the participant opens up an alternative social space to voice her subjectivity, display amateur discourse, destabilize linguistic hierarchy, and democratize mainstream values. It is a liberal-democratic and hierarchy-free online site, and a “transformative nexus zone” (Baynham and Lee 2019, p. 35) created by and for her translating and translanguaging.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we draw on the theoretical apparatus of translanguaging to look into an emerging form of amateur audiovisual translation, blogger subtitling, which is gaining momentum on the Chinese social media platform Weibo. Deploying a netnographic case study with @暴躁鸭仔, a Weibo subtitling video blogger, we built a corpus containing screenshots of her subtitled videos, real-time field notes, and online interview materials, focusing on her creative and critical language use when approaching audiovisual texts. It is found that she flexibly incorporates pictographic symbols into text-based scripts, exploits multiple discursive elements, manipulates orthographic features of Chinese, and adopts visual modes of signification. Through this process the boundaries between named languages are challenged and blurred. In her subtitling practice, various linguistic, semiotic, modal, cognitive resources which have long been treated as independent and isolated systems are integrated into her communicative repertoire as a whole. As she skillfully traverses back and forth between all these sense- and meaning-making resources, a social-media translanguaging space is opened up, within which the tension between translation and translanguaging is mediated to produce synergy. This online zone of diversity, dynamic, and fluidity witnesses an ever-evolving translating process oozing transformative power for liberating our understanding of subtitling, translation, and language use. Such translation practice embedded in a virtual translanguaging site is what we call trans-translating, with the suffix -ing about its on-going, fluid nature and the prefix trans- about it transformative potential.

As a small-scale pilot project, the present research enters uncharted territory of amateur subtitling—self-subtitling activities performed by bloggers on Weibo—which, because of its very limited participation and scope, has so far not come into the academic horizon. Catching up with the “self-translation trends” (Desjardins 2019, p. 171) in Web 2.0 context, blog subtitlers position themselves outside the routinized, commercial pattern prevailing in professional practice, and moreover, escapes the collaborative, group-as-a-unit workflow regulating fansubbers. Their highly personal, ingenious approaches to media contents, as illustrated in this article by hybrid use of multiple resources and playful subversion of established norms, make subtitling a powerful tool to maximize individuality and agency, articulate personal knowledge and attitudes, and display their narratives of the world, insomuch that the mainstream subtitling rules, as well as centralized media discourses, might be violated and even superseded. In this regard, our work addresses the lack of scholarship on the individual dimension of amateur subtitling and uncovers the diversification of online audiovisual translation. Given, however, the limitations of this case exploration in data volume and experimental period, only further in-depth studies with a bigger size of data and various perspectives can make clear more characteristics and socio-linguistic function of this unique form of amateur audiovisual mediation.

Just as in the case of blogger subtitling, thanks to the advancement of communication technologies and the omnipresence of online materials, considerable novel translation phenomena in the digital world have gained visibility and importance in everyday life and the academic circle. For the latter, the surging of such online translation activities lends it new energy but also arises a need to move beyond the entrenched binary logic and equivalence-centered analysis to embrace fresh perspectives and theoretical tools. Set in this status quo, our investigation seeks to map translanguaging theory onto translation practices in an affirmation that a translanguaging lens lends itself well to the analysis and (re)conceptualization of translation. Understood within a translanguaging framework, translation is not simply finding parallel equivalents between the source and the target but instead involves creative and critical socio-linguistic mediation through which different meaning-making resources, individual trajectory, and personal cognitive capacities are brought into one integrated and lived performance. This finding gains in further significance that we can imagine a “translanguaging turn” (Baynham and Lee 2019, p. 33) in translation to think “not of translation as a normalized thing but of translating to further foreground the dynamic activity” (ibid., p. 35; emphasis in the original). Also, applying translanguaging to translation will, in turn, reinvigorate the extant body of translanguaging scholarship in light of the fact that the act of translanguaging comes out of not only the domains of bi/multilingual classroom or daily spontaneous interaction but also translation context and heterolingual communication in the online sphere. Thus we can say recognizing translation and translanguaging in tandem remains a promising prospect to be forwarded.

Notes

While the literal English counterpart of the Chinese term “译制” is “dubbing”, we chose “subtitling” as the translation in that these bloggers’ practices only involve adding printed words on the screen instead of replacing the original speech with a new soundtrack.

Admittedly, the current verification of @暴躁鸭仔 is “微博剪辑视频博主” (Weibo Editing Video Blogger) because Weibo only permits a sole application for being confirmed as one of the three types of re-creation bloggers: “微博解说视频博主” (Weibo Narrating Video Blogger), “微博译制视频博主” (Weibo Subtitling Video Blogger), and “微博剪辑视频博主” (Weibo Editing Video Blogger). That said, the participant’s identity as a subtitling blogger is clearly evident in the contents of the posted videos as well as her personal recognition.

Acknowledgements

Our grateful thanks are due to @暴躁鸭仔 for her constant inspiration, support and contribution during the research process even without any monetary reward or personal relationship with the researchers.

References

Ameri, Saeed & Masood Khoshsaligheh. 2020. Dubbing viewers in cyberspaces: A netnographic investigation of the attitudes of a Persian-language online community. Kome: An International Journal of Pure Communication Inquiry 8(1). 23–43, https://doi.org/10.17646/kome.75672.45.Suche in Google Scholar

Baker, Colin. 2001. Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism, 3rd edn. Multilingual matters.Suche in Google Scholar

Baynham, Mike & Tong King Lee. 2019. Translation and translanguaging. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315158877Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Rafael, Eliezer. 2009. A sociological approach to the study of linguistic landscapes. In Elana Shohamy & Durk Gorter (eds.), Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery, 40–52. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Beseghi, Micòl. 2021. Bridging the gap between non-professional subtitling and translator training: A collaborative approach. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 15(1). 102–117, https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399x.2021.1880307.Suche in Google Scholar

Blackledge, Adrian & Angela Creese. 2017. Translanguaging and the body. International Journal of Multilingualism 14(3). 250–268, https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1315809.Suche in Google Scholar

Bogucki, Łukasz. 2009. Amateur subtitling on the Internet. In Díaz-Cintas Jorge & Anderman Gunilla (eds.), Audiovisual translation: Language transfer on screen, 49–57. Oxford: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230234581_4Suche in Google Scholar

Caffrey, Colm. 2009. Relevant abuse? Investigating the effects of an abusive subtitling procedure on the perception of TV anime using eye tracker and questionnaire. Doctoral dissertation. Ireland: Dublin City University.Suche in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, Suresh. 2011. Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal 95(3). 401–417, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x.Suche in Google Scholar

China Daily. 2021. yyds 什么意思? 00 后 “行话” 已经霸占网络平台了…… (The Chinese Internet Slang You Need To Know In 2021!). https://language.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202106/02/WS60b6ece8a31024ad0bac30b6.html (Retrieved from 27 December 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Creese, Angela & Adrian Blackledge. 2010a. Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: A pedagogy for learning and teaching? The Modern Language Journal 94(1). 103–115, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00986.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Creese, Angela. & Adrian Blackledge. 2010b. Towards a sociolinguistics of superdiversity. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 13(4). 549–572, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-010-0159-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Creese, Angela, Adrian Blackledge & Rachel Hu. 2018. Translanguaging and translation: The construction of social difference across city spaces. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21(7). 841–852, https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1323445.Suche in Google Scholar

Desjardins, Renée. 2019. A preliminary theoretical investigation into [online] social self-translation: The real, the illusory, and the hyperreal. Translation Studies 12(2). 156–176, https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2019.1691048.Suche in Google Scholar

Díaz-Cintas, Jorge & Pablo Muñoz Sánchez. 2006. Fansubs: Audiovisual translation in an amateur environment. Jostrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation 6. 37–52.Suche in Google Scholar

Díaz-Cintas, Jorge. 2018. ‘Subtitling’s a carnival’: New practices in cyberspace. Jostrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation (30). 127–149.Suche in Google Scholar

Dwyer, Tessa. 2012. Fansub dreaming on ViKi: “Don’t Just Watch But Help When You Are Free”. The Translator 18(2). 217–243, https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799509.Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia. 2009. Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia & Camila Leiva. 2014. Theorizing and enacting translanguaging for social justice. In Adrian Blackledge & Angela Creese (eds.), Heteroglossia as practice and pedagogy, 199–216. Dordrecht: Springer.10.1007/978-94-007-7856-6_11Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia & Wei Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137385765_4Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia& Claire E. Sylvan. 2011. Pedagogies and practices in multilingual classrooms: Singularities in pluralities. The Modern Language Journal 95(3). 385–400, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01208.x.Suche in Google Scholar

González, Luis Pérez. 2007. Fansubbing anime: Insights into the ‘butterfly effect’ of globalisation on audiovisual translation. Perspectives 14(4). 260–277, https://doi.org/10.1080/09076760708669043.Suche in Google Scholar

Gorter, Durk & Jasone Cenoz. 2015. Translanguaging and linguistic landscapes. Linguistic landscape 1(1–2). 54–74, https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.1.1-2.04gor.Suche in Google Scholar

Hornberger, Nancy H. & Holly Link. 2012. Translanguaging and transnational literacies in multilingual classrooms: A biliteracy lens. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 15(3). 261–278, https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2012.658016.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaplan, Andreas M. & Michael Haenlein. 2010. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons 53(1). 59–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Kozinets, Robert V. 2010. Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Kozinets, Robert V., Pierre-Yann Dolbec & Amanda Earley. 2014. Netnographic analysis: Understanding culture through social media data. In Uwe Flick (ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis, 262–276. Sage.10.4135/9781446282243.n18Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Hye-Kyung. 2011. Participatory media fandom: A case study of anime fansubbing. Media, Culture & Society 33(8). 1131–1147, https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443711418271.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Tong-King. 2015. Translanguaging and visuality: Translingual practices in literary art. Applied Linguistics Review 6(4). 441–465, https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0022.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Dang. 2017. A netnography approach to amateur subtitling networks. In Yvonne Lee & David Orrego-Carmona (eds.), Non-professional subtitling, 37–62. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Luyao & Jing Huang. 2021. The construction of heterogeneous and fluid identities: Translanguaging on WeChat. Internet Pragmatics 4(2). 219–246, https://doi.org/10.1075/ip.00046.li.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 2011a. Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics 43(5). 1222–1235, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 2011b. Multilinguality, multimodality, and multicompetence: Code‐and modeswitching by minority ethnic children in complementary schools. The Modern Language Journal 95(3). 370–384, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01209.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 2018a. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39(1). 9–30, https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 2018b. Translanguaging and code-switching: What’s the difference? Retrieved December 25, 2021, from OUPblog | Oxford University Press’s Academic Insights for the Thinking World. https://blog.oup.com/2018/05/translanguaging-code-switching-difference/.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei & Ofelia García. 2017. From researching translanguaging to translanguaging research. In Kendall King A, Yi-Ju Lai & Stephen May (eds.), Research methods in language and education, 227–240. London: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-02249-9_16Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei & Tong King Lee. 2021. language play in and with Chinese: Traditional genres and contemporary developments. Global Chinese 7(2). 125–142, https://doi.org/10.1515/glochi-2021-2008.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei & Hua Zhu. 2019. Tranßcripting: Playful subversion with Chinese characters. International Journal of Multilingualism 16(2). 145–161.10.1080/14790718.2019.1575834Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Maofu, Weili Guan, Jie Yan & Huijun Hu. 2019. Correlation identification in multimodal weibo via back propagation neural network with genetic algorithm. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 60. 312–318, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2019.02.015.Suche in Google Scholar

Lu, Sijing & Siwen Lu. 2021. Methodological concerns in online translation community research: A reflexive netnography on translator’s communal habitus, 1–16. Perspectives.10.1080/0907676X.2021.1913196Suche in Google Scholar

Luque, Francisca Garcia. 2018. The French amateur subtitling of Ocho apellidos vascos (Spanish Affair): The translation of stereotypes, cultural identities and multilingualism. Anales de Filología Francesa 26. 95–110.Suche in Google Scholar

Miller, Hannah J., Jacob Thebault-Spieker, Shuo Chang, Isaac Johnson, Loren Terveen & Brent Hecht. 2016. “Blissfully Happy” or “Ready to Fight”: Varying interpretations of emoji. In Tenth international AAAI conference on web and social media.Suche in Google Scholar

Orrego-Carmona, David. 2016. A reception study on non-professional subtitling: Do audiences notice any difference? Across Languages and Cultures 17(2). 163–181, https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2016.17.2.2.Suche in Google Scholar

Orrego-Carmona, David & Yvonne Lee (eds.). 2017. Non-professional subtitling. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Pérez-González, Luis. 2007. Intervention in new amateur subtitling cultures: A multimodal account. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series-Themes in Translation Studies 6. 67–80.10.52034/lanstts.v6i.180Suche in Google Scholar

Pérez-González, Luis. 2010. “Ad-hocracies” of translation activism in the blogosphere: A geneological case study. In Mona Baker, Maeve Olohan & María Calzada Pérez (eds.), Text and context: Essays on translation and interpreting in Honour of Ian Mason, 259–287. St Jerome Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Pérez-González, Luis. 2012. Amateur subtitling and the pragmatics of spectatorial subjectivity. Language and Intercultural Communication 12(4). 335–352, https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2012.722100.Suche in Google Scholar

Pérez-González, Luis. 2013. Amateur subtitling as immaterial labour in digital media culture: An emerging paradigm of civic engagement. Convergence 19(2). 157–175, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856512466381.Suche in Google Scholar

Rock, Frances. 2017. Shifting ground: Exploring the backdrop to translating and interpreting. The Translator 23(2). 217–236, https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2017.1321977.Suche in Google Scholar

Sajna, Mateusz. 2013. Amateur subtitling—Selected problems and solutions. T21N—Translation in Transition 3. 1–18.Suche in Google Scholar

Sato, Eriko. 2017. Translanguaging in translation: Evidence from Japanese mimetics. International Journal of Linguistics and Communication 5(2). 11–26, https://doi.org/10.15640/ijlc.v5n1a2.Suche in Google Scholar

Sato, Eriko. 2018. Sociocultural implications of the Japanese multi-scripts: Translanguaging in translation. In Hye Pae (ed.), Writing systems, reading processes, and cross-linguistic influences: Reflections from the Chinese, Japanese and Korean languages, 313–332. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/bpa.7.15satSuche in Google Scholar

Sato, Eriko. 2019. A translation-based heterolingual pun and translanguaging. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies 31(3). 444–464, https://doi.org/10.1075/target.18115.sat.Suche in Google Scholar

Schreiber, Brooke Ricker. 2015. “I am what I am”: Multilingual identity and digital translanguaging. Language, Learning and Technology 19(3). 69–87.Suche in Google Scholar

Stark, Luke & Kate Crawford. 2015. The conservatism of emoji: Work, affect, and communication. Social Media+ Society 1(2). 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115604853.Suche in Google Scholar

Tapscott, Don & Anthony D. Williams. 2006. Wikinomics: How mass collaboration changes everything. New York: Portfolio.Suche in Google Scholar

Tomei, Renato & Rajendra Chetty. 2021. Translanguaging strategies in multimodality and audiovisual translation. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 39(1). 55–65, https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2021.1909486.Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, Cen. 1994. Arfarniad o ddulliau dysgu ac addysgu yng nghyd-destun addysg uwchradd ddwyieithog [An evaluation of teaching and learning methods in the context of bilingual secondary education]. Bangor: Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Wales.Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, Cen. 1996. Secondary education: Teaching in the bilingual situation. In Cen Williams, Gwyn Lewis & Colin Baker (eds.), The language policy: Taking stock, Vol. 12(2), 193–211. Llangefni: CAI.Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, Cen 2012. The national immersion scheme guidance for teachers on subject language threshold: Accelerating the process of reaching the threshold. Bangor, Wales: The Welsh Language Board.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Yuhong. 2020. The danmaku interface on Bilibili and the recontextualised translation practice: A semiotic technology perspective. Social Semiotics 30(2). 254–273, https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2019.1630962.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Yuhong. 2021. Danmaku subtitling: An exploratory study of a new grassroots translation practice on Chinese video-sharing websites. Translation Studies 14(1). 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2019.1664318.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Hong. 2021. Translanguaging space and classroom climate created by teacher’s emotional scaffolding and students’ emotional curves about EFL learning. International Journal of Multilingualism. 1–27, https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.2011893.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Yi & Wei Ren. 2020. ‘This is so skrrrrr’—Creative translanguaging by Chinese micro-blogging users. International Journal of Multilingualism. 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1753746.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhao, Sumin & Rosie Flewitt. 2020. Young Chinese immigrant children’s language and literacy practices on social media: A translanguaging perspective. Language and Education 34(3). 267–285, https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2019.1656738.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- ELF- or NES-oriented pedagogy: enhancing learners’ intercultural communicative competence using a dual teaching model

- “You can’t start a fire without a spark”. Enjoyment, anxiety, and the emergence of flow in foreign language classrooms

- “You have to repeat Chinese to mother!”: multilingual identity, emotions, and family language policy in transnational multilingual families

- On the influence of the first language on orthographic competences in German as a second language: a comparative analysis

- Validating the conceptual domains of elementary school teachers’ knowledge and needs vis-à-vis the CLIL approach in Chinese-speaking contexts

- Agentive engagement in intercultural communication by L2 English-speaking international faculty and their L2 English-speaking host colleagues

- Review Article

- Illuminating insights into subjectivity: Q as a methodology in applied linguistics research

- Research Articles

- Making sense of trans-translating in blogger subtitling: a netnographic approach to translanguaging on a Chinese microblogging site

- The shape of a word: single word characteristics’ effect on novice L2 listening comprehension

- Success factors for English as a second language university students’ attainment in academic English language proficiency: exploring the roles of secondary school medium-of-instruction, motivation and language learning strategies

- LexCH: a quick and reliable receptive vocabulary size test for Chinese Learners

- Examining the role of writing proficiency in students’ feedback literacy development

- Confucius Institute and Confucius Classroom closures: trends, explanations and future directions

- Translanguaging as decoloniality-informed knowledge co-construction: a nexus analysis of an English-Medium-Instruction program in China

- The effects of task complexity on L2 English rapport-building language use and its relationship with paired speaking test task performance

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- ELF- or NES-oriented pedagogy: enhancing learners’ intercultural communicative competence using a dual teaching model

- “You can’t start a fire without a spark”. Enjoyment, anxiety, and the emergence of flow in foreign language classrooms

- “You have to repeat Chinese to mother!”: multilingual identity, emotions, and family language policy in transnational multilingual families

- On the influence of the first language on orthographic competences in German as a second language: a comparative analysis

- Validating the conceptual domains of elementary school teachers’ knowledge and needs vis-à-vis the CLIL approach in Chinese-speaking contexts

- Agentive engagement in intercultural communication by L2 English-speaking international faculty and their L2 English-speaking host colleagues

- Review Article

- Illuminating insights into subjectivity: Q as a methodology in applied linguistics research

- Research Articles

- Making sense of trans-translating in blogger subtitling: a netnographic approach to translanguaging on a Chinese microblogging site

- The shape of a word: single word characteristics’ effect on novice L2 listening comprehension

- Success factors for English as a second language university students’ attainment in academic English language proficiency: exploring the roles of secondary school medium-of-instruction, motivation and language learning strategies

- LexCH: a quick and reliable receptive vocabulary size test for Chinese Learners

- Examining the role of writing proficiency in students’ feedback literacy development

- Confucius Institute and Confucius Classroom closures: trends, explanations and future directions

- Translanguaging as decoloniality-informed knowledge co-construction: a nexus analysis of an English-Medium-Instruction program in China