Abstract

Fragment answers are nonsentential utterances quite pervasive in daily-life dialogues. This article focuses on fragment answers involving a negative dependency expression in Korean. The key question for the analysis of such a negative fragment expression is how to resolve sentential meaning from its non-sentential status. This article argues against sentential approaches that postulate clausal sources together with move-and-delete operations to generate negative fragments. Instead, the article supports a discourse-based direct interpretation analysis that allows negative fragment answers to be directly projected as a full utterance and obtain their propositional meaning by referring to the organized discourse structure in question.

1 Introduction

Fragment answers are non-sentential utterances (NSU) that function as a reply to various types of questions, as seen from the following attested data.[1]

| a. | A: What did they want? B: The secret files. (COCA 1993 MOV) |

| b. | A: Does he sing in English or Russian? B: In English. (COCA 1994 FIC) |

| c. | A: Does it still hurt? B: Not anymore. (COCA 2012 MOV) |

The fragment answers here are all incomplete sentences but receive sentential interpretations. The intended meaning of each fragment is thus equivalent to the following:[2]

| a. | They wanted the secret files. |

| b. | He sings in English. |

| c. | It does not hurt anymore. |

As a way of capturing such incongruous mapping from non-sentential fragments to propositional meanings, there have been two main strands: deletion-based sentential approaches and non-sentential direct interpretation (DI) approaches. The deletion-based approaches assume that fragments are derived from full-sentential sources like (2) together with move-and-delete operations (see, among others, Hankamer 1979; Merchant 2005; Morgan 1989; Weir 2014). For instance, the derivation of the fragment answer The secret files in (1a) starts from the usual syntax of a declarative sentence like (3) constructed from referring to its antecedent clause. In this source sentence, the NP bearing a focus value moves to the left peripheral position and then the remaining clause undergoes a focus-driven deletion (Merchant 2005):

| [FocP [NP the secret files][ |

The meaning of each fragment is thus derived from the corresponding full sentential structure, observing the usual mapping between syntax and semantics.

Meanwhile, nonsentential DI approaches assume that the complete syntax of a fragment is just the categorial phrase projection of the fragment itself (see, among others, Barton 1990; Culicover and Jackendoff 2005; Ginzburg and Sag 2000; Jacobson 2016). Within this view, the fragment NP answer The secret files can be projected into a sentential utterance with a simple syntactic structure like the following:

| [S [NP The secret files]]. |

The representation means that NP fragments can be a noncanonical type of utterance or a licensed expansion of S. With positing no unpronounced syntactic structures, this kind of simple syntax view employs a special mapping mechanism to get the propositional meaning induced from the fragment answer. For example, Culicover and Jackendoff (2005: 265) posit the following syntax-semantics rule:

| Bare Argument Ellipsis: |

| Syntax: [U XPiORPH]IL |

| Semantics:

|

The rule says that the fragment orphan XP can function as an utterance (U) ‘embedded in an indirectly licensed (IL) proposition’ and the orphan is semantically linked to an appropriate antecedent (through the function

| Syntax: [S The secret filesORPH]IL |

| Semantics: λx[want(i,x)](the.secret.files) |

Both sentential and nonsentential approaches, however, are challenged by fragment answers interacting with negation. For instance, consider fragment answers involving a negative expression from attested dialogues:[3]

| a. | A: What have the others done? B: Nothing/*Anything. (COCA 1992 SPOK) |

| b. | A: What are you not telling me? B: Nothing/*Anything. (COCA 2001 TV) |

As seen here from the data, indefinite NPs like nothing can function as a fragment answer, but those like anything in general do not serve as a fragment answer.[4] The question is then how we could account for this contrast. The deletion-based sentential approaches would derive such fragment answers from clausal sources that are syntactically identical to the antecedent clause.[5] The fragments in (7a) would thus be derived from (8a) and (8b) and those in (7b) from (9a) and (9b), respectively:

| a. | The others have done nothing. |

| b. | *The others have done anything. |

| a. | *I am not telling you nothing. |

| b. | I am not telling you anything. |

The unacceptable fragment answer Anything in (7a) could be attributed to its unacceptable putative source in (8b). However, issues could arise from the fragments Nothing/*Anything in (7b). The putative source of the fragment Nothing would be something like (9a), but this is not natural in standard English. In the meantime, the ungrammatical fragment Anything would have an acceptable source like (9b). The sentential analyses would generate a legitimate fragment answer from an illegitimate sentential source, requiring an additional mechanism to save or repair an unacceptable source.[6] It is also questionable what blocks the generation of a fragment answer from a proper sentential source, e.g., from (9b) to the unacceptable fragment Anything.

A further complication arises from the so-called negative fragment answers observed in negative concord (NC) languages like Italian and Romanian. Consider the following Romanian examples from Fǎlǎş and Nicolae (2016):[7]

| Cine | a | venit? |

| who | has | come |

| ‘Who has come?’ | ||

| Nimeni. |

| n-body |

| ‘Nobody has come.’ |

With the assumption that the clausal deletion applies under syntactic identity with its antecedent, the putative source of the fragment answer Nimeni in (10B) would be something like (11a). However, this is ungrammatical since, as in (11b), the NCI needs to be licensed by an overt sentential negator (Fǎlǎş and Nicolae 2016):[8]

| *Nimeni | a | venit. |

| n-body | has | come |

| (intended) ‘Nobody has come.’ | ||

| Nimeni | nu | a | venit. |

| n-body | neg | has | come |

| ‘Nobody has come.’ | |||

Another point to note here is that in (11b), there are two negative elements, the n-word nimeni and the sentential negator nu, but the sentence is interpreted as only being negated once. This leads to the term ‘negative concord (NC)’ (see Giannakaidou 2006 for the details). If the sentential analysis derives the fragment answer (10B) from (11b), two issues then arise: how to repair the violation of syntactic identity condition for deletion and how to compose a single logical negation from two negative expressions. Note that the semantic resolution of such a negative fragment also challenges non-sentential DI approaches. To license a negative fragment like (10), DI approaches could assume that these expressions are inherently negative, but they also require to answer the second question: how the two negative expressions, n-word and sentential negation, yield only one logical negation (see De Swart and Sag 2002 and Section 4 for further discussion).

Languages like Korean also behave like Romanian at first glance. Consider the following Korean example:[9]

| Nwu-ka | o-ass-e? |

| who-nom | come-pst-que |

| ‘Who came?’ | |

| Amwu-to. |

| anybody-also |

| ‘Nobody came.’ |

As observed here, the expression amwu-to ‘anybody-also’ marked with the delimiter -to can function as a proper fragment answer to the wh-question.[10] This expression, like the Romanian NC word nimeni in (11), needs to be licensed by a negation in other contexts, as illustrated in the following contrast:[11]

| *Amwu-to | o-ass-e. |

| anybody-also | come-pst-decl |

| (intended) ‘Nobody came.’ | |

| Amwu-to | an | o-ass-e. |

| anybody-also | not | come-pst-decl |

| ‘Nobody came.’ | ||

The syntactic identity condition for ellipsis would require the source sentence of the fragment (12B) to be the ungrammatical sentence in (13a). Korean examples like this again show us that reconstructing a sentential source of a fragment cannot simply refer to its antecedent clause. In the meantime, DI approaches could generate the NC word amwu-to ‘anybody-also’ as an independent fragment that projects into a nonsentential utterance. However, this direction also faces challenges in accounting for what kind of mechanism allows the negative fragment to be mapped into a proper NC reading.

This article first discusses two different types of negative dependencies, NPI (negative polarity items) and NCI (negative concord items) and then reviews both move-and-delete sentential approaches and surface-oriented nonsentential approaches for the account of negative fragments in Korean. The article suggests that in dealing with negative fragment answers in Korean, the sentential approaches meet more challenges than the DI approach suggested here. In particular, the article shows that a variety of empirical facts we find in negative fragment answers in Korean support a direct generation of negative fragments with a direct semantic resolution referring to the discourse structure in question.

2 Two types of negative dependencies: NCI and NPI

As noted in Zanuttini (1991), Giannakaidou (2006), and others, there are two different types of negative dependencies: negative concord item (NCI) and negative polarity item (NPI). The former NCI has more than one negative in the given sentence, but it is interpreted as being negated only once, as noted earlier. Consider the following Italian example (Zanuttini 1997: (13a)):

| *(Non) | ho | visto | nessuno. | ||||

| neg | have | seen | nobody | ||||

| ‘It is not the case that I have seen somebody.’ | |||||||

In (14), the obligatory sentential negation marker non and the object nessuno ‘n-body’ together yield one logical negation, rather than a double negation that would make the sentence as a positive one. The second type of NPI, traditionally taken to be non-negative, is similar to the NCI in that it also needs to be licensed by a negator, as seen from the following English examples:

| a. | I have *(not) seen anyone. |

| b. | I have (*not) seen nobody. |

The examples in (14) and (15) seem to illustrate that the Italian NCI nessuno ‘n-body’ and the NPI anyone are quite similar in that both need to occur in a negative context, but they differ in several respects. For example, the NCI in the subject position can occur alone, but the NPI anyone needs to have a licensor like a negation. This is seen from the following contrast:

| Nessuno | ha | telefonato. |

| n-body | has | called |

| ‘Nobody called.’ | ||

| *Anybody called. |

There are other differences between the NCI and the NPI items. The differences given in Table 1 have been often noted by the previous literature (see, among others, Sano et al. 2009; Watanabe 2004).

Differences between NPI and NCI.

| NPI | NCI | |

|---|---|---|

| used as an elliptical answer | No | Yes |

| modified by expressions like almost | No | Yes |

| appear in non-negative contexts | Yes | No |

| licensed by a higher clause negation | Yes | No |

Let us consider these distinctive features in detail. The first distinctive feature of the two concerns fragment answers: as noted earlier, the NCI can occur as a fragment answer while the NPI cannot. Compare English and Spanish examples:

| A: | Who did you meet? |

| B: | Nobody/*Anybody. |

| A: | ¿Qué | comiste? |

| what | eat-2sg.pst | |

| ‘What did you eat? | ||

| B: | Nada. | |

| ‘n-thing’ | ||

As seen from (17), NPI words like anybody in English cannot serve as a fragment answer. However, the Spanish n-word nada ‘n-thing’ can independently occur as a fragment answer, even though, just like the Italian n-word nessuno, it needs to be licensed by a sentential negation in non-elliptical environments (Giannakaidou 2006; Weir 2020):

| *(No) Comí | nada. |

| neg ate. 1st.pst | n-thing |

| ‘I ate nothing.’ | |

Let us then consider Korean examples. In Korean, there are at least three negative sensitive items, amwu-(N)-to ‘any-N-also’, etten-N-to ‘which-N-also’ and nwukwu-to ‘who-also’. Since these expressions require a sentential negator as their licensor, they seem to be candidates for either strong NPIs or NCIs:

| Amwu-to | *(an) | manna-ss-ta. |

| anybody-also | not | meet-pst-decl |

| ‘I didn’t meet anybody.’ | ||

| Etten-salam-to | *(an) | manna-ss-ta. |

| which-person-also | not | meet-pst-decl |

| ‘I didn’t meet anyone.’ | ||

| Nwukwu-to | *(an) | manna-ss-ta. |

| who-also | not | meet-pst-decl |

| ‘I didn’t meet anybody.’ | ||

However, of these three, only amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ is natural as a fragment answer (see also Chung 2012; Hwang 2020; Kim 2013; Tieu and Kang 2014):

| Ne | nwukwu(-lul) | manna-ss-ni? |

| you | who-acc | meet-pst-que |

| ‘Who did you meet?’ | ||

| Amwu-to/??Etten-salam-to/*Nwukwu-to. |

| ‘Nobody.’ |

Another key distinction between NCIs and NPIs comes from the possibility of modification by adverbs like almost. In English, the NPI anybody cannot be modified by almost (Giannakidou 2000):[12]

| a. | *Kim didn’t eat almost anything. |

| b. | *Kim didn’t meet almost anybody. |

In contrast, amwu-N-to or etten-N-to seem to occur with almost, as seen from the attested examples:[13]

| keuy | amwu-to/?etten | salam-to | o-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| almost | anybody-also/which | person-also | come-conn | not-pst-decl |

| ‘Almost nobody came.’ | ||||

| keuy | amwu-to/?etten | salam-to | an | manna-ss-ta. |

| almost | anybody-also/which | person-also | not | meet-pst-decl |

| ‘I met almost nobody.’ | ||||

| keuy | amwu-eykey-to/?etten | salam-eykey-to | kamyemtoy-ci | anh-ass-ta. | ||

| almost | anybody-dat-also/which | person-dat-also | infected-conn | non-pst-decl | ||

| ‘Almost nobody was infected.’ | ||||||

As shown here, the expression amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ can be modified by the adverb keuy ‘almost’ regardless of its grammatical function.

Another difference between NPIs and NCIs concerns their occurrences in non-negative contexts including a question or a conditional clause. It is well-noted that English NPIs can appear in non-negative contexts:

| a. | Are you guilty of anything? |

| (COCA 1992 SPOK) | |

| b. | If anybody has an idea, please let me know before the evening ends. |

| (COCA 2016 MOV) |

Unlike in English, the three negative sensitive items in Korean do not occur in polar questions:[14]

| Ne | *amwu-to/*etten-salam-to/*nwukwu-to | manna-ss-ni? |

| you | anybody-also/which-person-also/who-also | meet-pst-que |

| ‘Did you meet anybody?’ | ||

A further difference between Korean NPIs including amwu-N-to and corresponding English ones comes from the syntactic position of their licensor. The English NPI anybody can be licensed by a higher clause negation:

| a. | I don’t think it is fine to talk like that to anybody. (COCA 2010 TV) |

| b. | I don’t believe that he has any racism. (COCA 2018 SPOK) |

But this is disallowed for the three n-words in Korean, as illustrated by the following:[15]

| Mimi-nun | *amwu-to/*etten-salam-to/*nwukwu-to | manna-ss-ta-ko |

| Mimi-top | anybody-also/which-person-also/who-also | meet-pst-decl-comp |

| na-nun | sayngkakha-ci | anh-nun-ta. |

| I-top | think-conn | not-pres-decl |

| (intended) ‘I don’t think Mimi met anybody.’ | ||

The data indicate that these negative expressions in Korean need to be licensed by a local licensor.

In sum, the applications of the standard tests to distinguish NCIs and NPIs in Korean show us that Korean amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ as well as etten-N-to ‘which-N-also’ behaves more like an NCI while nwukwu-to ‘who-also’ seems to have more restrictive-uses. These are summarized in the following (Table 2).

NCI and NPI tests in Korean.

| amwu-N-to | etten-N-to | nwukwu-to | |

|---|---|---|---|

| used as an elliptical answer | Yes | ??Yes | No |

| modified by expressions like almost | Yes | ?Yes | ??No |

| appear in non-negative polar Qs | No | No | No |

| licensed by a higher clause negation | No | No | No |

3 Inherent negative versus indefinite analyses from a deletion-based perspective

The possibility of having an NCI as a fragment answer has motivated the literature to assume its inherent negativity. This ‘inherently negative’ approach then allows a fragment NCI to be interpreted negatively in the absence of any overt negation marker (see, among others, Haegeman and Zanuttini 1996; Watanabe 2004; Zanuttini 1991; Zeijlstra 2004). One immediate question concerns the semantic composition when the NCI occurs with its licensing negation in a nonelliptical declarative environment. For instance, examples like (19) have two negative expressions, n-word and sentential negator, but the semantic composition needs to yield only one logical negation (see Haegeman and Zanuttini 1991, 1996; Zanuttini 1991). The typical solution that the analysis of inherent negativity introduces is to adopt a feature copying and checking mechanism. For instance, Watanabe (2004: 564) suggests that Japanese expression nani-mo in (28B) carries a neg feature that induces negative meaning:

| Nani-o | mita | no? |

| What-acc | saw | que |

| ‘What did (you) see?’ | ||

| Nani-mo |

| what-mo |

| ‘Nothing.’ |

| Nani-mo | [mi-na-katta]. |

| what- mo | see-not- pst |

| ‘Nothing was seen.’ | |

According to Watanabe (2004), the negator, bearing a neg feature, copies another neg feature from the assumed NCI nani-mo via Agree, and then the three neg features all together render one logical negation.

One could adopt this kind of feature copying and checking approach to the uses of amwu-to ‘anybody-also’ in Korean. As we have seen in (21), unlike nwukwu-to ‘who-also’, amwu-to can serve as a fragment answer. Consider a similar example:

| Nwu-ka | Jina-lul | manna-ss-ni? |

| who-nom | Jina-acc | meet-pst-que |

| ‘Who met Jina?’ | ||

| Amwu-to./*Nwukwu-to. |

| anyone-also/who-also |

| ‘Nobody met Jina.’ |

If adopting ellipsis under syntactic identity, the putative clausal source of both fragments would be ungrammatical:

| *Amwu-to | Jina-lul | manna-ss-ta. |

| anybody-also | Jina-acc | meet-pst-decl |

| (intended) ‘Nobody met Jina.’ | ||

| *Nwukwu-to | Jina-lul | manna-ss-ta. |

| who-also | Jina-acc | meet-pst-decl |

| (intended) ‘Nobody met Jina.’ | ||

The correct resolution of the fragment requires the introduction of the negator in addition. The question is then why only amwu-to can function as a fragment answer as in (30).

Kim (2013) notes that the fragment answers Amwu-to and *Nwukwu-to in (30) are derived from (31a) and (31b), respectively. However, only the former is repaired as an acceptable one. The analysis that Kim (2013) adopts for this contrast refers to the inherent negativity of amwu-N-to. To avoid the issue of deriving the legitimate fragment answer Amwu-to from an ungrammatical source like (31a) and further obtaining a negative reading with no negator, Kim’s analysis introduces a process that repairs the source for a Neg-feature checking requirement (due to the inherent negativity). An immediate issue then arises from the fact that, as also acknowledged by Watanabe (2004), we cannot freely allow such a repair process or accommodation that assigns the oppositive polarity value to the putative sentential source. For instance, (30B) can serve as a possible fragment answer to the question in (30A), but this does not mean that we can freely posit a negative clause as its source, since the fragment could also yield a positive proposition, as seen from the following simple dialogue exchange:

| Nwu-ka | Mimi-lul | manna-ss-ni? |

| who-nom | Mimi-acc | meet-pst-que |

| ‘Who met Mimi?’ | ||

| Momo. ‘Momo met Mimi.’ |

No negative propositional meaning can be projected from the fragment answer here.

The inherently negative quantifier approach runs into another possible issue when the question is negative:

| Nwu-ka | Jina-lul | an | manna-ss-ni? |

| who-nom | Jina-acc | not | meet-pst-que |

| ‘Who didn’t meet Jina? | |||

| Amwu-to. |

| anybody-also |

| ‘Nobody met Jina.’ |

The putative source of the fragment answer here would be a grammatical one as given in (34):

| Amwu-to | Jina-lul | an | manna-ss-ta. |

| anybody-also | Jina-acc | not | meet-pst-decl |

| (intended) ‘Nobody met Jina.’ | |||

Given the inherent negative analysis of amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’, there are then two negative expressions, amwu-to and the negator an here. We then are forced to assign no negative meaning to the sentential negation an ‘not’ or introduce an apparatus that assigns no negation meaning to the sentential negator an.

Departing from such inherent negativity analyses, Giannakaidou (2006) and Zeijlstra (2016) suggest that n-words do not have the semantic force of negative quantifiers but just function as indefinites. The analysis suggests that the n-word is an indefinite noun bearing an ‘uninterpretable NEG (uNEG)’ feature to be checked under the Agr feature by an interpretable negation. Consider the Italian example in (35a) and its derivation in (35b) (Penka and Zeijlstra 2010; Zeijlstra 2008):

| Gianni | non | telefona | a | nessuno. |

| Gianni | neg | calls | to | n-body |

| ‘Gianni doesn’t call anybody.’ | ||||

| Gianni non [iNEG] telefona a nessuno [uNEG] . |

As given in (35b), the feature checking system allows the uninterpretable NEG feature of the n-word nessuno to be checked by the negator non bearing the interpretable NEG (iNEG) feature. In the meantime, when the n-word appears as a fragment answer to a positive question as in the Italian example (36B), its inherent uNEG feature is checked not by the negator but by the operator inserted as a last resort operation via a syntactic Agree relation in the ellipsis environment. This derivation is given in (37) (Fǎlǎş and Nicolae 2016; Penka and Zeijlstra 2010):

| Ha | telefonato | nessuno? |

| has | telephone | n-body |

| ‘Has anybody called?’ | ||

| No. Nessuno. |

| ‘No. Nobody has called.’ |

| [Op [iNEG] [Nessuno |

However, the analysis assumes that the situation is different in NPI contexts (Weir 2020):

| A: | What did he bring to the party? |

| B: | *Any wine. (intended: ‘He didn’t bring any wine.’) |

The unacceptability of the fragment any wine here suggests that the expression any N in English differs from the NCI, in that it carries an uninterpretable negative feature [uNEG] that has to be checked by an interpretable negative feature [iNEG] (Zeijlstra 2004). Within this feature approach, the NPI any-N cannot bear a [uNEG] feature by definition if it is inherently negative. A possible advantage of this NEG feature-based checking approach may come from examples where NCI fragments induce ambiguous readings. Consider the following Romanian data from Fǎlǎş and Nicolae (2016).

| Cine | nu | a | venit? |

| who | not | has | come |

| ‘Who has not come?’ | |||

| Nimeni. ‘Nobody.’ (= ‘Nobody came.’/‘Nobody didn’t come.’) |

The putative source of the fragment is a negative antecedent clause, as given in (40a). This clausal source then does not require the NEG operator to be inserted because of the presence of nu ‘not’. Optionally, the operator can be inserted in elliptical environments as in (40b), which would then yield a double negation reading:

| a. | [Nimeni |

| b. | [Op [iNEG] [ |

Adopting this feature checking system for Korean examples, Tieu and Kang (2014) attempt to account for the difference between amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ and etten-N-to ‘which-N-also’ in Korean. Their analysis suggests that amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ bears an interpretable Neg feature [iNeg:_] while etten-N-to ‘which-N-also’ carries an unvalued uninterpretable Neg feature [uNeg:_]. This difference in feature specifications is assumed to allow only the former to be interpreted without an overt negation head (sentential negation) in elliptical environments. Consider the following from Tieu and Kang (2014):

| Nwu-ka | Mimi-lul | manna-ss-ni? |

| who-nom | Mimi-acc | meet-pst-que |

| ‘Who met Mimi?’ | ||

| Amwu-to/*Etten-salam-to. |

| anybody-also/which-person-also |

| ‘Nobody met Mimi.’ |

The two fragment answers have the following derivations, according to Tieu and Kang (2014):[16]

| a. | Amwu [iNeg:_]-to [ |

| b. | *Etten [uNeg:_]-to [ |

As represented here, the key difference of the two expressions depends on whether they bear an interpretable feature (iNeg) or not (uNeg). This difference in the Neg feature may capture the difference in their uses as fragment answers, but raises several questions. First, it is not clear what mechanism introduces the sentential negation here even when the antecedent clause is positive. Second, the fragment n-word is claimed to introduce the negative head (sentential negation), but we cannot claim that an n-word always introduces a negative head. When the antecedent clause is negative, the analysis would then trigger a double negation reading, contrary to the fact. In addition, as also pointed out by Hwang (2020), this feature-based account runs into another empirical issue with respect to examples like (43):

| Khephi-wa | cha | cwung | etten-kes | masi-llay? |

| coffee-and | tea | among | which-thing | drink-que |

| ‘Between coffee and tea, which one do you like?’ | ||||

| Amwu-kes-to/(?)Etten-kes-to. |

| ‘Nothing/None of them.’ |

This example shows us that etten-kes-to can be used as a fragment answer. The question in (43) asks the hearer to choose one of the provided individuals, and then etten-kes-to ‘which-thing-also’ behaves like amwu-kes-to ‘anything-also’ and can serve as a fragment. The improvement of etten-kes-to as a fragment in such a context implies that it is not the lexical property but the context cues (e.g., D-linking properties) that plays a key role in licensing n-words as fragment answers.[17]

Another possible issue seems to arise from ambiguous readings in fragment answers. Consider the following fragment whose antecedent is a negative proposition (see also Hwang 2020):

| Nwu-ka | swukcey | an | nay-ess-ni? |

| who-nom | homework | not | submit-pst-que |

| ‘Who hasn’t yet submitted the homework?’ | |||

| Amwu-to(-yo). |

| anybody-also-decl |

| ‘Nobody did.’ or ‘Everyone did.’ |

The negative fragment here can give us either a negative or a positive reading, as seen from its interpretations. Given that the n-word amwu-to ‘anybody-also’ bears an interpretable NEG feature, Tieu and Kang (2014) would allow only one negative reading since the main verb or the negative auxiliary bearing an uninterpretable feature plays no role in the interpretation. Within the feature checking analysis, the only option is to allow the expression amwu-to either as an uninterpretable or interpretable. This in turn implies that we thus cannot lexically predetermine the meaning of amwu-N-to, contrary to the feature checking analyses. Contextual or discourse will tell us its meaning (see Section 5.2 for contextual variations).

4 Inherent negative analyses from a lexicalist perspective

As pointed out in passing by Weir (2020), nonsentential DI analyses need to accept that NCIs are inherently negative to induce a negative reading. If NCIs are indefinite quantifiers, issues arise from how to license n-words as well as how to obtain a negative reading. Before discussing possible analyses within the DI perspective, let us consider some key points of De Swart and Sag (2002) offering a DI approach of NC in French within the framework of HPSG.[18]

De Swart and Sag (2002), following the ideas of Zanuttini (2001) and Haegeman and Zanuttini (1996), apply the pair-list readings in multiple wh-questions (e.g., Who bought what?) to multiple negative indefinites like (45).

| Personne | (n’)aime | personne. |

| no.one | neg.likes | no.one |

This sentence, according to De Swart and Sag (2002), would have the following two readings:

| DN (double negative): no one is such that they love no one. |

| ¬∃ x ¬∃ y love(x,y) |

| ‘Nobody loves nobody.’ |

| NC (negative concord): No pair of people is such that one love the other. |

| ¬∃ x , y love(x,y) |

| ‘No one loves anyone.’ |

In order to capture the two ambiguous readings in (46), the analysis introduces quantifier resumption to (negative) quantifiers, with the following rules:

| General rules for quantification (De Swart and Sag 2002: 392) | |

| a. | All quantifiers ‘start out’ in storage. |

| b. | Quantifiers are retrieved from storage at the lexical level, e.g., by verbs other than raising verbs. |

| c. | This retrieval is affected by a constraint that relates the store values of a verb’s arguments and the verb’s semantic content. |

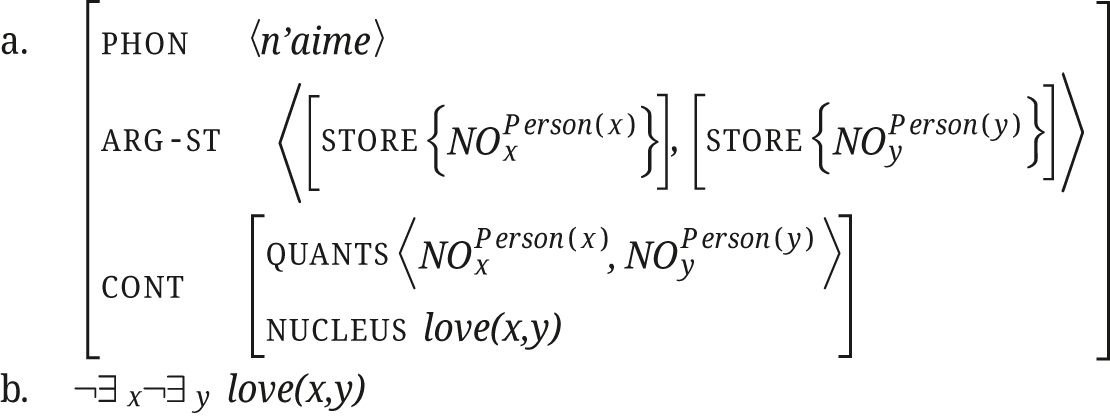

These general rules are implemented within the feature structure system of HPSG. For instance, the verb (n’)aime in (52) is taken to have the following information:

|

With the assumption that anti-additive quantifiers can undergo resumption, the retrieved quantifiers can interact with other quantifiers as in (49a) (the corresponding meaning in (49b)) or the retrieved set can be the doubleton set containing both anti-additive quantifiers as in (50a) (the corresponding meaning in (50b)):[19]

|

|

This analysis can be extended even to cases with a negative adverbial like jamais ‘never’ as in Personne n’a jamais dit ça ‘No-one NE-has never said that’. With the assumption that such an adverbial can be in a member of the extended argument structure (arg-st), the analysis can then expect two readings (NC and DN) in exactly the same way.

In spite of such merits, this negative-inherent approach of De Swart and Sag (2002) has several issues. For instance, it faces challenges when the n-word has an NC relation with a non-negative expression, as also pointed out by Zeijlstra (2016):

| Dudo | que | vayan | a | encontar | nada. |

| doubt.1Sg | that | will.3. pl.sbj | that. prt | find | n-thing |

| ‘I doubt they will find anything.’ | |||||

The n-word nada here is within the complement clause of verbs like dudo ‘doubt’, but has no negative meaning. Given that the negative quantifier is inherently negative as in De Swart and Sag (2002), such a sentence then needs to interpreted as containing a true negation, contrary to the fact.

Another possible difficulty for the analysis of De Swart and Sag (2002) arises from the treatment of examples with an n-word serving as a fragment answer. Consider the following French example (Déprez 1997):

| Qui | a | été | invite? |

| who | has | been | invited |

| ‘Who was invited?’ | |||

| Zéro personnes/personne. |

| ‘Zero people/no one’. |

The issue concerns the retrieval of store value. In De Swart and Sag (2002), the presence of a lexical head is key to the retrieval, but the fragment answer here is a stand-alone phrase serving as a non-sentential utterance: it includes no lexical head projecting a sentence. There is thus no mechanism to retrieve the quantification value unless there is an invisible lexical head selecting the n-word.

Korean examples can bring about another issue in assigning an inherently negative meaning to a NC-word. In Romanian examples like (53a), the presence of two n-words with a sentential negation can yield either an NC or a DN reading (Fǎlǎş and Nicolae 2016; Merchant 2005). However, this does not hold in languages like Korean as shown in (53b):

| Nimeni | nu | a | citit | nimic. |

| nobody | not | has | read | nothing |

| ‘Nobody has read anything.’ or ‘Nobody hasn’t read anything.’ | ||||

| Amwu-to | amwu-kes-to | an | ilk-ess-ta. |

| anyone-also | any-thing-also | not | read-pst-decl |

| ‘Nobody read anything.’ | |||

The Korean sentence in (53b) contains two allegedly n-words and one sentential negation. If these n-words behave like Romanian n-words in (53a) or French ones in (52), we would expect both a DN or NC reading. However, (53b) has only one semantic negation that scopes over both n-words.

5 A direct interpretation approach

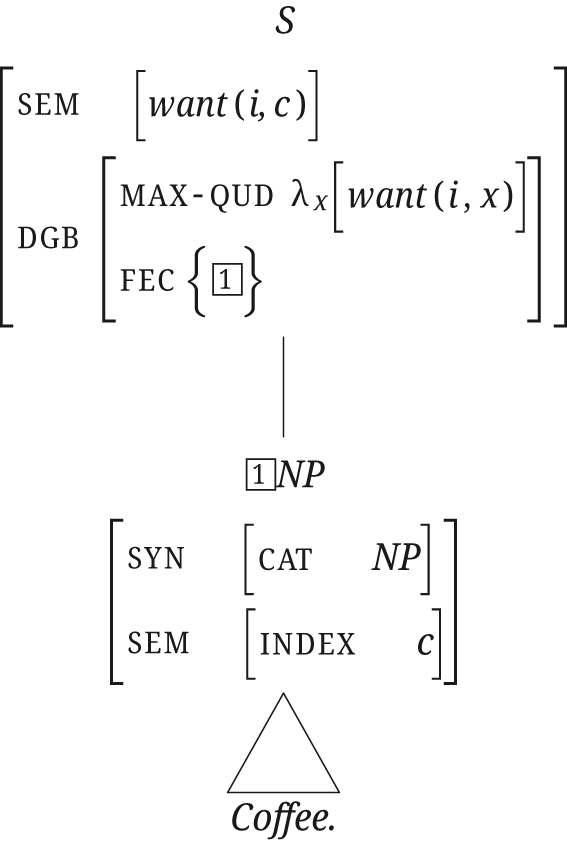

5.1 Resolving fragments

Departing from the deletion-based approach that posits a clausal source for fragment answers, the DI (direct interpretation) approach obtains a propositional meaning of fragments with no underlying syntactic structures (Culicover and Jackendoff 2005; Ginzburg 2012; Jacobson 2016). Within the DI approach, there is no syntactic structure at the ellipsis site and fragments are the sole daughter of an S-node, directly licensed from the following construction motivated from a variety of non-sentential utterances (NSUs) (Ginzburg and Sag 2000; Kim 2015; Kim and Abeillé 2019):

| Head Fragment Construction: |

| Any category can be projected into an NSU (non-sentential utterance) as long as it is a focus establishing constituent. |

The construction allows any maximal projection (functioning as a salient or focus-establishing constituent) to serve as an NSU with no reference to ellipsis. This construction-based view thus assigns a simple structure to the fragment Coffee serving as an answer to a wh-question like What did they want?, as given in the following:

|

The semantic resolution of such a fragment is then achieved by discourse-based machinery. In particular, the interpretation of a fragment depends on the notion of ‘question-under-discussion’ (qud) in the dialogue. Dialogues are described via a Dialogue Game Board (dgb) where the contextual parameters are anchored and where there is a record of who said what to whom, and what/who they were referring to (see Ginzburg 2012). Since the value of qud is constantly being updated as the dialogue progresses, the relevant context offers the basis for the interpretation of fragments. In this system, dgb is thus part of the contextual information and has at least the attributes fec (focus establishing constituent) and max-qud (maximal-question-under-discussion), as given in (56).

|

The feature max-qud, representing the question currently under discussion, takes as its value questions while the feature fec represents a focusing establishing constituent, linked to the max-qud. For example, uttering the question What do they want? will activate the following dgb information:

|

Since the fragment answer Coffee can function as the focused salient information associated with the wh-question (dgb), it can serve as a proper answer to the wh-question, as shown in (58):

|

This fragment answer is a well-formed stand-alone clause licensed by the Head-Fragment Construction. As noted, the preceding wh-question introduces a qud asking a value for the object that they want (λ x [want(i,x)]). The fragment Coffee, functioning as a salient utterance, then provides a value for this variable. This resolution process is thus quite equivalent to the view that the meaning of a question is a function that yields a proposition when applied to the meaning of the answer, as given in the following (Jacobson 2016; Krifka 2001):[20]

| a. | Meaning of the Q & max-qud: λx [want(i, x)] |

| b. | Meaning of the fragment: c |

| c. | The fragment answer applied to the Q: λx[want(i, x)](c) = [want(i, c)] |

In the DI approach, the resolution process of a fragment answer thus resorts to neither clausal sources nor movement operations, but utilizes the information evoked from the context.

5.2 Resolving negative fragments

The present analysis laid out in the previous section implies that the resolution of negative fragments is also dependent upon the interplay of their lexical semantics and discourse structure concerning question-under-discussion and salient focus information. As we have noted, Korean negative sensitive items like amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ are similar to n-words in that they need to be licensed by a negation, and can occur as a fragment answer. However, they behave like NPIs in the sense that they cannot appear by itself as in *Anybody came. For the proper analysis of these negative dependency expressions, I take such expressions as NPIs and, following the direction of Giannakidou (2000), Giannakaidou (2006), take Korean amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ expressions to be indefinites with no negative quantificational force of their own. For instance, amwu-kes-to ‘any-thing-also’ would take the following meaning representation:[21]

| [[amwu-kes-to]] = thing(x) |

The denotation of such an expression thus includes no inherent negation. The expression is just a regular indefinite one bound by existential closure under negation, as suggested by Krifka (1995) and Ladusaw (1996).[22]

| ¬∃x[… thing(x) …] |

We could interpret this kind of closure condition as an entailment condition ensured by the background information evoked from the expression referring to a scalar ordering: the negative expression makes reference to the bottom of a scale or widen the domain of quantification (Linebarger 1987; Potts 2005). According to this idea, NPIs are thus licensed either by an overt negation or by pragmatic entailment, which we take as conventional implicature (CI) here. That is, when the syntactic environment provides no overt licensor (e.g., sentence negator), the use of an NPI leads to ungrammaticality. But its use is licensed when the context enables to derive a negative inference (Chierchia 2006; Giannakaidou 2006; Krifka 1995; Linebarger 1987, 1991; Toosarvandani 2008).

As noted by Potts (2005) and others, conventional implicature (CI) is part of the agreed meaning of a lexical or phrasal item. For instance, as illustrated in the following, words like even, too, but, fail or constructions like nominal appositive have a CI meaning:

| a. | Mimi has come too. |

| b. | Entailment: Mimi has come. |

| c. | Conventional implicature: Some other person also came. |

| a. | Lance Armstrong, a Texan, has won the 2002 Tour de France. |

| b. | Entailment: Lance Armstrong has won the 2002 Tour de France. |

| c. | Conventional implicature: Lance Armstrong is a Texan. |

The expression too or the nominal apposition thus accompanies a CI meaning in addition to its semantic entailment meaning.

In Korean, CI can also be either lexically or phrasally marked. One such an example is the N-to ‘N-also’:

| onul | Kim-to | o-ass-ney. |

| today | Kim-also | come-pst-decl |

| ‘Kim too came today.’ | ||

| Entails: Kim came today. |

| Conventionally implicates: Some other given person came today. |

The NP Kim-to in (64a) evokes a CI meaning such that there is some other person who came today. Unlike this kind of positive CI, when the delimiter -to combines with an amwu-N expression or minimizer, a negative CI is evoked:

| Amwu-kes-to | mek-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| any-thing-also | eat-conn | not-pst-decl |

| ‘(I) didn’t eat anything.’ | ||

| Hanphwun-to | namkyetwu-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| one.penny-also | leave-conn | not-pst-decl |

| ‘I didn’t save one penny.’ | ||

However, when we have another type of delimiter like -ina ‘even’ or -man ‘only’, there is no such CI meaning:

| Amwu-kes-ina | mek-ess-ta. |

| any-thing-even | eat-pst-decl |

| (intended) ‘I ate anything (free choice).’ | |

| hanphwun-man | namkyetwu-ess-ta. |

| one.penny-only | leave-pst-decl |

| ‘I saved only one penny.’ | |

The examples show us that unlike -to ‘also’, the morpheme -ina ‘even’ or -man ‘only’ neither requires a negative predicate nor evokes a negative meaning. Examples in (66) have only positive CIs.

The present analysis implies that the marker -to attached to a phrasal expression plays a key role in evoking a CI meaning, and further that examples like the following are unacceptable since they are not bound by existential closure under negation:

| *I | sangca-ey | amwu-kes-to | iss-ta. |

| this | box-at | any-thing-also | exist-decl |

| (intended) ‘There is nothing in the box.’ | |||

| *Amwu-to | manna-ss-ta. |

| anybody-also | meet-pst-decl |

| (intended) ‘I didn’t meet anyone.’ | |

The NPI amwu-kes-to ‘any-thing-also’ or amwu-to ‘anyone-also’ evokes a negative inference such that there is no individual involved in the situation in question here. The examples in (67) violate this conventional implicature (CI) imbued with the expression amwu-N-to. This idea can be formalized in terms of at-issue and CI meaning. That is, the amwu-N-to expression is indefinite in terms of its at-issue meaning but carries a CI negating the existence of this indefinite expression, as given in the following constructional rule:

|

As represented here, the expression amwu-kes-to is semantically indefinite (as at-issue meaning) but at the same time accompanies a CI meaning such that the individual denoted by the indefinite amwu-kes-to is in the scope of negation. Since the expression carries a nonexistence implicature, its licensing condition is not syntactically-controlled but secured by a semantic/pragmatic environment that does not conflict with the nonexistence entailment. This is why examples like (67b) are not licensed since the context implies the existence of an individual linked to the indefinite.

The failure of having a negative conventional implicature for amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ thus results in pragmatic infelicity: The expression amwu-N-to is typically licensed by a sentential negator, but, as noted earlier, predicates like silh-ta ‘dislike’ in Korean also evoke a negative conventional implicature:[23]

| onul | amwu-kes-to | ha-ki | silh-ta. |

| today | any-thing-also | do-conn | dislike-decl |

| ‘Today I don’t like to do anything.’ | |||

There is no morpho-syntactic licensor for the NPI amwu-kes-to, but the sentence is legitimate since it implicates that there is nothing that I like to do today.

One thing to note is that this construction is a phrasal level one, not a lexical-class one, arguing against any lexical NEG feature assignment to amwu-N-to. Observe the following:

| Amwu-len | umsik-to | mek-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| any-mod | food-also | eat-conn | not-pst-decl |

| ‘(I) didn’t eat any food.’ | |||

| Amwu | umsik-ina | cal | mek-ess-ta. |

| any | food-ina | well | eat-pst-decl |

| ‘(He) could eat any food well.’ | |||

As observed here, both the delimiter -to and -ina scope over a phrasal expression. Only the -to marked expression can evoke a negative CI. These two implies that it is not lexical properties but phrasal constructions that determine negative dependency.

With this construction-based assignment of the negative CI to amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’ constructions, let us reconsider the uses of amwu-N-to as a fragment answer. As we have seen, the expression can serve as a fragment answer with no overt negation but its use is indirectly licensed by a negative inference like CI:

| Mwues | mek-ess-e? |

| what | eat-pst-que |

| ‘What did you eat?’ | |

| Motwu. ‘Everything.’ |

| Amwu-kes-to. ‘Nothing.’ |

| *Amwu-kes-to. | Sakwa-ka | masiss-ess-e. |

| any-thing-also. | apple-nom | delicious-pst-decl |

| ‘Nothing. The apple was delicious.’ | ||

The wh-question here asks if there is any entity that the hearer ate. It thus evokes the following dgb information:

|

Each of the fragment answers in (71) basically provides an answer to a question – a value to the variable evoked in the preceding qud.[24] As given here, possible fragment answers can quite vary, including B1 and B2. Consider the fragment B1 first:

|

The answer means that the hearer ate everything that is available. There is no CI evoked here from the universal quantifier. However, the fragment Amwu-kes-to ‘any-thing-also’ in B2 include a CI meaning, as represented in the following:

|

The fragment answer can serve as an answer to the question (What did you eat?), and the yielded meaning is such that there is no individual that satisfies as its value in terms of the CI meaning. This meaning resolution can be also represented in the following format:

| a. | Meaning of the Q: λx[eat(h,x)] |

| b. | Meaning of the fragment: thing(x) → P(x) |

| c. | At-issue meaning of the fragment answer: thing(x) → eat(h,x) |

| d. | CI meaning of the fragment answer: ¬∃x[… thing(x),…] |

As represented here, the dialogue introduces a qud that asks for a value of the variable (x) that hearer ate.[25] The fragment answer Amwu-kes-to ‘any-thing-also’ then provides a value for this variable. Its at-issue meaning is an indefinite individual, but the CI says there is no such individual in this eating situation.

This analysis sketched here thus implies that as long as the context satisfies the CI meaning such that there is no entity that the hearer ate, the fragment is a legitimate answer. This in turn means if the context does not entail the negation of its existence, its use is of the pragmatic infelicity, not observing the conventional implicature. This is why (71B3) is unacceptable.

As discussed earlier, we have also seen that the fragment amwu-N-to as an answer to a negative question can induce either an NC or a DN reading (see Hwang 2020 for a similar note). Context would choose a preference, as seen from the following:

| Nwu-ka | an | o-ass-ni? |

| who-nom | not | come-pst-que? |

| ‘Who didn’t come? | ||

| Amwu-to. |

| ‘Nobody came’ or ‘Everyone came.’ |

| Onul | achim | nwu-ka | yangchicil | an | ha-yess-ni? |

| this | morning | who-nom | toothbrush | not | do-pst-que |

| ‘Who didn’t do toothbrush this morning?’ | |||||

| Amwu-to. |

| ‘Nobody did.’ or ‘Everyone did.’ |

With no contextual bias for the situation, we could expect either an NC reading or a DN reading here. Before considering how these two readings are possible, consider a negative polar question and two possible answers expressed by response particles:

| Mimi | an | o-ass-ni? |

| Mimi | not | come-pst-que? |

| ‘Didn’t Mimi come? | ||

| Ung. ‘yes’ (Mimi didn’t come.) |

| Ani. ‘no’ (Mimi came.) |

As noted by Kim (2017) and others, Korean adopts the truth-based answering system, not the polarity-based system of English.[26] This is why the positive response in B1 refers to the negative proposition of the polar question, affirming that Mimi didn’t come. The negative response ani ‘no’ can be ambiguous: it can disaffirm the negative proposition, thus yielding the reading of ‘Mimi came’. However, as noted by Kim et al. (2020), it is also possible to refer to the positive proposition evoked by the polar question in a given context. In this case, the positive response in B1 would mean ‘Mimi came’ and the negative response would express the negative proposition ‘Mimi didn’t come’. This in turn means that the negative polar question has a negative proposition as its max-qud in a typical situation (following the truth-based answering system), but given a proper context, it can also evoke a positive proposition as its max-qud (following the polarity-based answering system). This can be represented in the following:[27]

| a. | Meaning of the polar question: λ{}[¬ come(m)] |

| b. | max-qud evoked from the question in the truth-based system: λ{}[¬ come(m)] |

| c. | max-qud evoked from the question in the polarity-based system: λ{}[come(m)] |

With this possibility, consider the negative wh-question ‘Who didn’t come?’ and its fragment answer Amwu-to ‘anyone-also’ in (76). As in the negative polar question, the negative wh-question can evoke either a negative proposition or a positive proposition as its max-qud. The fragment answer amwu-to can then refer to either of these two with respect to its CI meaning:

| when referring to the negative max-qud: | |

| a. | max-qud: λx[¬come(x)] |

| b. | CI meaning: ¬∃x[…person(x)…] |

| when referring to the positive max-qud: | |

| a. | max-qud: λx[come(x)] |

| b. | CI meaning: ¬∃x[…person(x)…] |

When the CI is relevant with respect to the negative max-qud as in (80), we would have a double negation meaning such that there is no one such that the one did not come. In the meantime, when it refers to the positive one as in (81), it means there is no individual who came. The interplay of the max-qud and the CI meaning thus can yield two possible readings in a systematic way.

We have noted earlier that unlike amwu-N-to, etten-N-to in general does not occur as a fragment answer, but with a proper context with D-linked referents, it becomes quite acceptable as fragment answer. Consider a similar example here:

| Ne-nun | i | mwunce | cwung | mwues-ul | phwul-ci | mos-ha-ni? |

| you-top | this | question | among | what-acc | solve-conn | not-do-que |

| ‘Among these questions, which one can’t you solve? | ||||||

| Amwu kes-to/?etten kes-to. |

| ‘any-thing-also/which-thing-also.’ |

The expression etten kes-to in general does not function as a fragment answer, but when it refers to a D-linked set, it can serve as a fragment. This contextual dependency can follow from the present system. As given in the following, we can assume that etten-N-to carries a ci meaning just like amwu-N-to in such a D-linked environment:

|

When the context supplies a set of discourse-linked individuals, etten-N-to can well evoke this CI meaning, but when the context lacks such discourse-familiar individuals, it would not have such a CI meaning and thus cannot serve as a fragment answer. Such data once again tell us that we cannot rely on a lexical-based feature-assignment system in which such Korean words are predetermined to bear an uninterpretable NEG feature (Tieu and Kang 2014).

Another advantage of the present analysis can be observed in a sentence with more than one n-word, which we have discussed earlier. Consider a similar example here:[28]

| Amwu-to | amwu | mal-to | ha-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| anyone-also | any | word-also | do-conn | not-pst-decl |

| ‘Nobody said any words.’ | ||||

| Amwu-to | amwu-kes-to | po-i-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| anyone-also | any-thing-also | see-pass-conn | not-pst-decl |

| ‘Nobody saw anything.’ | |||

| Amwu-to | amwu-kes-to | amwu-eykey-to | cwu-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| anyone-also | any-thing-also | anyone-dat-also | give-conn | not-pst-decl |

| ‘Nobody gave anything to anyone.’ | ||||

There are two or even n-words or NPIs here. The previous analyses in which the n-word is taken to be a negative quantifier or bear a neg feature would have an ambiguous reading here (De Swart and Sag 2002; Tieu and Kang 2014). However, the sentences in (84) are not ambiguous at all: each of these has just one logical negation reading in Korean. Fragment answers can also have two n-words:

| Nwu-ka | mwusen | mal | ha-yss-e? |

| who-nom | what | word | do-pst-que? |

| ‘Who said what? or ‘Did someone say something?’ | |||

| Amwu-to | amwu | mal-to. |

| anyone-also | any | word-also |

| ‘Nobody said any words.’ | ||

The only possible reading for (85B) is a single negation reading: it has no double negation reading such that nobody said no words. The data here all then imply that we can assign neither an inherent negative meaning nor a NEG feature to these n-words, which would result in a double negation reading. The examples rather support the view that the negative meaning comes only from the overt sentential negation. The present analysis, in which the n-word is taken to be an indefinite and accompanies a negative CI, we can expect this single reading. Consider the meanings of (85):

| a. | Meaning of the Q: λxλy[say(x,y)] |

| b. | At-issue meaning of the fragment: [person(x) → P(x)] & [thing(y) → P(y)] |

| c. | CI meaning of the fragment answer: ¬[∃x∃y[…person(x) & thing(y)…]] |

Both amwu-to ‘anybody-also’ and amwu mal-to ‘amwu-saying-also’ have no negative meanings. They are just indefinites, which evoke a negative CI such that there exist no individual associated with these indefinites. As the CI meaning here shows, each N-word would not introduce its own negation reading (e.g., ¬∃ x ¬∃ y ) since it would mean the existence of the individuals. This would then violate the assumed CI meaning of the two n-words. Each N-word is interpreted as an indefinite one together with its individual being bound by existential closure under negation as a CI meaning.

The present analysis can also offer an explanation for the behavior of adverbs like acik ‘still/yet’. As noted by the literature and further by Potts (2005), English words like still can evoke a CI meaning:

| a. | Mimi has still not come. |

| b. | Entailment: Mimi has not come. |

| c. | Conventional implicature: Mimi was expected to have come by now. |

Note that the adverb acik in Korean, whose meaning is similar to still, also evokes a CI meaning.

| Mimi-ka | acik | tochakha-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| Mimi-nom | still | arrive-conn | not-pst-decl |

| ‘Mimi has not arrived yet.’ | |||

| *Mimi-ka | acik | tochakha-yess-ta. |

| Mimi-nom | still | arrive-pst-decl |

One of its lexical peculiarities is that when the adverb modifies a stative verb like chwup ‘cold’, no CI is evoked, as evidenced by the following pair of examples:

| Nalssi-ka | acik | chwup-ta. |

| weather-nom | still | cold-decl |

| ‘The weather is still cold.’ | ||

| Nalssi-ka | acik | chwup-ci | anh-ta. |

| weather-nom | still | cold-conn | not-decl |

| ‘The weather is still not cold.’ | |||

The adverb acik ‘still’ can modify not only the positive situation of being cold as in (98a) but also the negative situation of not being cold as in (89b). This observation means that acik lexically accompanies its negative CI meaning only when it modifies a non-stative verb like arrive as in (88). This then would predict the following for its uses as a fragment answer:

| Mimi-nun | cip-ey | o-ass-ni? |

| Mimi-top | house-at | come-pst-que |

| ‘Did Mimi come home?’ | ||

| Acik. ‘not yet’ (‘She has not come home yet.’) |

| Mimi-nun | cip-ey | iss-ni? |

| Mimi-top | house-at | exist-que |

| ‘Is Mimi still at home?’ | ||

| Acik. ‘still’ (‘She is still at home.’) |

As seen from the examples, when acik is linked to a non-stative predicate, it evokes a negative meaning, but when it is associated with stative predicate, it evokes no negative CI.

Together with these observations, we can assume that the adverb acik, similar to still in English, is lexically encoded with a CI meaning when it modifies a nonstative VP:

|

Note that we cannot simply assume that the nonstative acik is inherently negative. Observe the following examples where it occurs with an amwu-N-to:

| Amwu-to | acik | tochakha-ci anh-ass-ta. |

| anybody-also | still | arrive-conn not-pst-decl |

| ‘Nobody has arrived yet.’ | ||

| Amwu-kes-to | acik | an | mek-ess-ta. |

| any-thing-also | still | not | eat-pst-decl |

| ‘I haven’t eaten anything yet.’ | |||

| Amwu-kes-to | acik | ha-ki silh-ta. |

| any-thing-also | still | do-conn dislike-decl |

| ‘I dislike to do anything yet.’ | ||

Both amwu-N-to and acik ‘still’ introduce a negative CI. Having the two in the same sentences thus evokes no double negative meaning and further raises no compatibility issues with respect to CI or entailment. Since both have a negative CI evoked, it is quite natural to occur with the sentential negation (LFN or SFN), or with a negative verb like silh-ta ‘dislike’.

6 Conclusions

The article started with the discussion that fragment answers with negative dependency expressions like NPI and NCI challenge both derivational and non-derivational analyses. The derivational analysis posits clausal sources for negative fragments, but, as we have discussed, this direction runs into possible problems with examples where the putative sources are ungrammatical. The non-derivational direct interpretation approach also meet difficulties in mapping proper propositional meanings from negative fragment answers.

The article discussed the behavior of three negative dependent words amwu-N-to ‘any-N-also’, etten-N-to ‘which-N-also’, and mwues-to ‘what-also’ in Korean, all of which need to be licensed by an overt negator in general. The key difference among the three lies in the distribution possibilities as fragment answers. The first and the last one show a clear contrasting behavior, but the use of the second one etten-N-to as a fragment answer is dependent upon the context. The language also employs adverbial expressions like acik ‘still’, whose occurrences as fragment answers also depend on the context. All these empirical data challenge previous analyses where such expressions are taken to be inherently negative or bear some NEG features. The present analysis suggests a more viable direction is to license such expressions in fragment answer environments in the system that allows the tight interplay between the lexical semantics and the discourse structure involving the conventional implicature (background information) linked to the negative expressions.

Funding source: Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea

Award Identifier / Grant number: (NRF-2022S1A5A2A03052578).

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at several occasions including Laboratoire de linguistique formelle at Université Paris Cité on June 13, 2023. I thank the audiences for questions and comments. My thanks also go to Anne Abeillé, Jungsoo Kim, Okgi Kim, Seulkee Park, Javier Pérez-Guerra, and Manfred Sailer for their feedback and helpful suggestions in the development of this article. The anonymous reviewers of this journal also deserve my thanks for constructive criticisms and suggestions, which helped refine the ideas developed here.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022S1A5A2A03052578).

References

Barton, Ellen. 1990. Nonsentential constituents. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.2Search in Google Scholar

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2006. Broaden your views: Implicatures of domain widening and the “logicality” of language. Linguistic Inquiry 37. 535–591. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2006.37.4.535.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Daeho. 2012. Is amwu-N-to a negative quantifier? Linguistic Research 29(3). 541–562. https://doi.org/10.17250/khisli.29.3.201212.004.Search in Google Scholar

Culicover, Peter W. & Ray S. Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199271092.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

De Swart, Henriette & Ivan Sag. 2002. Negation and negative concord in Romance. Linguistics and Philosophy 25. 373–417. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020823106639.10.1023/A:1020823106639Search in Google Scholar

Déprez, Viviane. 1997. Two types of negative concord. Probus 9(2). 103–142. https://doi.org/10.1515/prbs.1997.9.2.103.Search in Google Scholar

Fǎlǎş, Anamaria & Andreea Nicolae. 2016. Fragment answers and double negation in strict negative concord languages. In Mary Moroney, Carol-Rose Little, Jacob Collard & Dan Burgdoff (eds.), Proceedings of SALT 26, 584–600. Ithaca, NY: Linguistic Society of America & Cornell Linguistics Circle.10.3765/salt.v26i0.3813Search in Google Scholar

Giannakaidou, Anastasia. 2006. N-words and negative concord. In Martin Everaert & Henk van Riemsdijk (eds.), The Blackwell companion to syntax, 327–391. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470996591.ch45Search in Google Scholar

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2000. Negative. . . concord? Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18. 457–523. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006477315705.10.1023/A:1006477315705Search in Google Scholar

Ginzburg, Jonathan. 2012. The interactive stance: Meaning for conversation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199697922.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Ginzburg, Jonathan & Ivan A. Sag. 2000. Interrogative investigations: The form, meaning and use of English interrogatives (CSLI Lecture Notes 123). Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Groenendijk, Jeroen & Martin Stokhof. 1984. Studies on the semantics of questions and the pragmatics of answers. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Haegeman, Liliane & Raffaella Zanuttini. 1991. Negative heads and the neg criterion. The Linguistic Review 8. 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlir.1991.8.2-4.233.Search in Google Scholar

Haegeman, Liliane & Raffaella Zanuttini. 1996. Negative concord in West Flemish. In Adriana Belletti & Luigi Rizzi (eds.), Parameters and functional heads: Essays in comparative syntax, 117–197. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195087932.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

Hamblin, Charles. 1973. Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language 10(1). 41–53.Search in Google Scholar

Hankamer, Jorge. 1979. Deletion in coordinate structures. New York: Garland.Search in Google Scholar

Holmberg, Anders. 2016. The syntax of yes and no. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198701859.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hwang, Juhyeon. 2020. On different types of negative concord items and their interpretation in Korean. Studies in Linguistics 56. 81–99. https://doi.org/10.17002/sil.56.202007.81.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobson, Pauline. 2016. The short answer: Implications for direct compositionality (and vice versa). Language 92(2). 331–375. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2016.0038.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, Bob M. 1999. The Welsh answering system. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110800593Search in Google Scholar

Karttunen, Lauri. 1977. Syntax and semantics of questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 1. 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00351935.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jong-Bok. 2015. Syntactic and semantic identity in Korean sluicing: A direct interpretation approach. Lingua 166(B). 260–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2015.08.005.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jong-Bok. 2016. The syntactic structures of Korean: A construction-based perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781316217405Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jong-Bok. 2017. On the anaphoric nature of particle responses to the polar questions in English and Korean. Korean Journal of linguistics 42(2). 153–177. https://doi.org/10.18855/lisoko.2017.42.2.003.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jong-Bok. 2020. Negated fragments: A direct interpretation approach. Korean Journal of English Language and Linguistics 20(3). 427–449.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jong-Bok & Anne Abeillé. 2019. Why-stripping in English. Linguistic Research 36. 365–387. https://doi.org/10.17250/khisli.36.3.201912.002.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jong-Bok, Jungsoo Kim & Rok Sim. 2020. Discourse-based answering systems: An experiment-based analysis. Paper presented at Linguistic Evidence 2020, Feb 13–15. University of Tubingen.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Rhanghyeyun. 2013. On the negativity of negative fragment answers and ellipsis resolution. Studies in Generative Gammar 23(3). 447–467. https://doi.org/10.15860/sigg.23.3.201308.447.Search in Google Scholar

Krifka, Menfred. 1995. The semantics and pragmatics of polarity items. Linguistic Analysis 25. 209–257.Search in Google Scholar

Krifka, Menfred. 2001. For a structured meaning account of questions and answers. In Caroline Féry & Wolfgang Sternefeld (eds.), Audiatur vox sapientiae: A festschrift for Arnim von Stechow. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Ladusaw, William. 1996. Negation and polarity items. In Shalom Lappin (ed.), The handbook of contemporary semantic theory, 321–341. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1111/b.9780631207498.1997.00015.xSearch in Google Scholar

Linebarger, Marcia. 1987. Negative polarity and grammatical representation. Linguistics and Philosophy 10(1). 325–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00584131.Search in Google Scholar

Linebarger, Marcia. 1991. Negative polarity as lingusitic evidence. In Lise M. Dobrin, Lynn Nichols & Rosa Rodriguez (eds.), Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 165–188. Chicago, IL: Chicago Linguistic Society.Search in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2005. Fragments and ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 27(6). 661–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-005-7378-3.Search in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2013. Voice and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 44(1). 77–108. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00120.Search in Google Scholar

Morgan, Jerry. 1989. Sentence fragments revisited. In Bradley Music, Randolph Graczyk & Caroline Wiltshire (eds.), CLS 25: Papers from the 25th Annual Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 228–241. Chicago, IL: Chicago Linguistic Society.Search in Google Scholar

Penka, Doris & Hedde Zeijlstra. 2010. Negation and polarity: An introduction. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 28(4). 771–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-010-9114-0.Search in Google Scholar

Pesetsky, David. 1987. Wh-in-situ: Movement and unselective binding. In Eric J. Reuland & Alice G. B. ter Meulen (eds.), The representation of (in) definiteness, 98–129. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199273829.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Sailer, Manfred & Frank Richter. 2021. Negative conjuncts and negative concord across the board. In Berthold Crysmann & Manfred Sailer (eds.), One-to-many relations in morphology, syntax, and semantics, 175–244. Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sano, Tetsuya, Hiroyuki Shimada & Takaomi Kato. 2009. Negative concord vs. negative polarity and the acquisition of Japanese. In Jean Crawford (ed.), Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America, 232–240. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Search in Google Scholar

Tieu, Lyn & Jungmin Kang. 2014. On two kinds of negative concord items in Korean. In Robert E. Santana-LaBarge (ed.), Proceedings of the 31st West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 466–473. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla ProceedingsProject.Search in Google Scholar

Toosarvandani, Maziar. 2008. Letting negative polarity alone for let alone. In Tova Friedman & Satoshi Ito (eds.), Proceedings from Semantics and Linguistic Theory 18, 729–746. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publication.10.3765/salt.v18i0.2493Search in Google Scholar

Watanabe, Akira. 2004. The genesis of negative concord: Syntax and morphology of negative doubling. Linguistic Inquiry 35. 559–612. https://doi.org/10.1162/0024389042350497.Search in Google Scholar

Weir, Andrew. 2014. Fragments and clausal ellipsis. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts, Amherst dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Weir, Andrew. 2020. Negative fragment answers. In Viviane Déprez & M. Teresa Espinal (eds.), The Oxford handbook of negation. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198830528.013.14Search in Google Scholar

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1991. Syntactic properties of sentential negation: A comparative study of Romance languages. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1997. Negation and clausal structure: A comparative study of romance languages. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195080544.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 2001. Sentential negation. In Mark Baltin & Chris Collins (eds.), The handbook of contemporary syntactic theory, 511–535. Malden, MA: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470756416.ch16Search in Google Scholar

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2004. Sentential negation and negative concord. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2008. On the syntactic flexibility of formal features. In Theresa Biberauer (ed.), The limits of syntactic variation, 143–173. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.132.06zeiSearch in Google Scholar

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2016. Negation and negative dependencies. Annual Review of Linguistics 2. 233–254. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-030514-125126.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Right node raising in Mandarin Chinese: are we moving right?

- A structural and functional comparison of differential A and P indexing

- Inanimate antecedents of the Japanese reflexive zibun: experimental and corpus evidence

- Prediction in SVO and SOV languages: processing and typological considerations

- Fragment answers with negative dependencies in Korean: a direct interpretation approach

- The particle suo in Mandarin Chinese: a case of long X0-dependency and a reexamination of the Principle of Minimal Compliance

- On the property-denoting clitic ne and the determiner de/di: a comparative analysis of Catalan and Italian

- On Italian spatial prepositions and measure phrases: reconciling the data with theoretical accounts

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Right node raising in Mandarin Chinese: are we moving right?

- A structural and functional comparison of differential A and P indexing

- Inanimate antecedents of the Japanese reflexive zibun: experimental and corpus evidence

- Prediction in SVO and SOV languages: processing and typological considerations

- Fragment answers with negative dependencies in Korean: a direct interpretation approach

- The particle suo in Mandarin Chinese: a case of long X0-dependency and a reexamination of the Principle of Minimal Compliance

- On the property-denoting clitic ne and the determiner de/di: a comparative analysis of Catalan and Italian

- On Italian spatial prepositions and measure phrases: reconciling the data with theoretical accounts