Abstract

This article discusses the right node raising construction in Chinese (henceforth the RNR). It aims to provide a novel analysis that can deal with two new observations made in the Chinese RNR construction, including the tone sandhi phenomenon, which provides clues to the syntax of RNR from syntax-prosody mapping, and a syntactic constraint that only arguments, but not adjuncts, may qualify as an RNR target. Based on these new observations, I show that none of the previous analyses of the RNR (mainly in English) are fully adequate in accounting for the RNR in Chinese. An alternative analysis is pursued here. Given the syntactic and syntax-prosodic properties, I propose to analyze the gaps within the coordinated structure in Chinese Right-Node Raising (RNR) by exploring the notion of an empty noun, along with the concept of the True Empty Category. In the RNR construction, the coordinated structure undergoes leftward movement over the RNR target, which is driven by considerations of information structure. As a result, this induces an illusion of rightward movement on the surface.

1 Introduction

It has been claimed that rightward dislocations are generally unacceptable in Chinese sentences (Huang 1982). Therefore, we should not expect to find the right node-raising construction (RNR) in Chinese. However, the following sentences suggest that Chinese does allow RNR, where the shared object DPs (italicized) are dislocated to the rightmost position:

| Zhangsan | yao | mai, | keshi | Lisi | bu | yao | mai, | wo-de | fangzi. |

| Zhangsan | want | buy | but | Lisi | not | want | buy | my | house |

| ‘Zhangsan wants to buy, but Lisi does not want to buy, my house.’ | |||||||||

| bu-zhi | Zhangsan | xihuan, | erqie | Lisi | ye | xihuan, | zhe | suo | xuexiao |

| not-only | Zhangsan | like | and | Lisi | also | like | this | Cl. | school |

| ‘Not only does Zhangsan like, but Lisi also likes, this school.’ | |||||||||

In the literature, there are two major structural analyses of this phenomenon. The rightmost element (the RNR target), wo-de fangzi ‘my house’ or zhe suo xuexiao ‘this school’ in the coordinated structures in (1a)–(1b), is either base generated in the surface position or is moved out of the coordinated structures.[1] According to the former analysis, if the rightmost element is base generated in the second conjunct, then there is only one gap in the first conjunct of the coordinated structure, and the gap can be analyzed as a deleted element at PF, as shown in (2a). According to the latter, the rightmost element is moved to some higher position out of the coordinated structure, and the ATB (across-the-board)-style movement (Williams 1978) leaves a gap (trace) in each conjunct in the coordinated structure, as in (2b):

| […V |

(‘backward’ PF-deletion of the first DP) |

| [… V t], but [… V t], DP | (rightward ATB-movement out of both conjuncts) |

Since Chinese generally does not allow rightward dislocation, it might be tempting to adopt the PF-deletion approach and claim that the rightmost element in (1) is base generated. However, evidence from prosodic boundaries suggests otherwise. As shown in Example (3), it is observed that in the second conjunct, no tone sandhi occurs between the verb mai ‘buy’ and the object wo-de fangzi ‘my house’, which signals a prosodic boundary between the verb and its dislocated object (or the RNR target). The lack of tone sandhi suggests that the verb and the RNR target are not in a head-complement configuration, and since the syntactic movement may create a prosodic boundary that blocks the application of tone sandhi (Liu and Chen 2020; Yin 2003), the blocking of tone sandhi in the second conjunct in (3) seems to provide empirical support for the movement analysis:[2]

| [[Zhangsan | yao | mǎi/*mái __], | [keshi | Lisi | bu | yao | mǎi/*mái__], | [wǒ de | fangzi]] |

| # | # |

It seems that we now reached an impasse – on. the one hand, the base-generated PF-deletion approach cannot account for the prosodic boundary in the second conjunct. On the other hand, the movement approach forces us to assume an ad hoc rightward movement rule specifically tailored for the RNR in Chinese, and this rule is absent from other constructions in Chinese. This article is an attempt to find a way out of the deadlock.

The organization of this article is as follows. I will first investigate in detail the properties of the Chinese RNR in Section 2. In Section 3, I address the problems of previous analyses, including the PF-deletion approach and the rightward ATB movement approach. It will be argued that none of them are tenable for the analysis of RNR in Chinese. On the other hand, by adopting the proposal of the empty noun by Panagiotidis (2003), the True Empty Category by Li (2005, 2007, 2014) and Aoun and Li (2008) and the focus dislocation analysis in Cheung (2009), I propose an alternative solution for the Chinese RNR in Section 4. Section 5 concludes the article.

2 Properties of the Chinese RNR

2.1 The coordinated structure in the Chinese RNR

In this section, we compare the RNR in Chinese with that in English, which is better studied. Generally speaking, in both languages, RNR sentences always involve coordinated structures, and more specifically, they target clausal coordination. Two kinds of connectives are seen in the Chinese RNR, as shown in (4) and (5):

| bu | zhi | Zhangsan | xihuan ____, | erqie | Lisi | ye | xihuan | _____, | na | tai | che. |

| not | only | Zhangsan | like | and | Lisi | also | like | that | Cl. | car | |

| ‘Not only Zhangsan likes, but Lisi also likes that car.’ | |||||||||||

| Zhangsan | xihuan ____, | keshi | Lisi | bu | xihuan ____, | na | tai | che. |

| Zhangsan | like | but | Lisi | not | like | that | Cl. | car |

| ‘Zhangsan likes but Lisi doesn’t like that car.’ | ||||||||

Literally, erqie is a connective like and in English, and keshi is like but. However, unlike and/but in English, which can connect various types of phrases of equal size, erqie and keshi can only take clausal and verbal phrases (CPs and VPs), but not nominal ones (NPs and DPs). With respect to this difference, Aoun and Li (2003) have shown that Chinese has various kinds of conjunctions that connect different domains/levels of phrases of the same size:

| jian ‘and’: connecting NPs (properties) | ||||||

| ta | shi | yi | ge | [NP geshou] | jian | [ NP yanyuan]. |

| he | is | one | Cl. | singer | and | actor |

| ‘He is a singer and actor.’ | ||||||

| he/gen ‘and’: connecting DPs (individuals) | |||||||||||

| wo | hen | xihuan | [DP | zhe | jian | maoyi] | gen | [DP | na | tiao | qunzi]. |

| I | very | like | this | Cl. | sweater | and | that | Cl. | skirt | ||

| ‘I like this sweater and that skirt.’ | |||||||||||

| erqie ‘and’/ keshi ‘but’: connecting CPs and VPs (clauses and predicates) |

| [Zhangsan | xihuan | chang | ge] | erqie | [Lisi | ye | xihuan | chang | ge]. |

| Zhangsan | like | sing | song | and | Lisi | also | like | sing | song |

| ‘Zhangsan likes to sing and Lisi also likes to sing.’ | |||||||||

| [Zhangsan | xihuan | chang | ge] | keshi | [Lisi | bu | xihuan | chang | ge] |

| Zhangsan | like | sing | song | but | Lisi | not | like | sing | song. |

| ‘Zhangsan likes to sing but Lisi does not like to sing.’ | |||||||||

The examples in (8) then suggest that the conjuncts in the Chinese RNR are both clauses.[3] There is only one minor difference between erqie ‘and’ and keshi ‘but’– erqie can be freely omitted on the surface as long as the adverb ye ‘also’ appears. Therefore, (8a) can also be paraphrased as follows in (9).

| Zhangsan | xihuan | chang | ge, | (erqie) | Lisi | ye | xihuan | chang | ge |

| Zhangsan | like | sing | song | and | Lisi | also | like | sing | song |

| ‘Zhangsan likes to sing and Lisi also likes to sing.’ | |||||||||

We have shown that the sentential RNR in Chinese involves CP-coordinated structures, on a par with the sentential RNR in English. Another property that can be compared to English RNR constructions is that the gaps in the Chinese RNR must occur in the right-most position of each conjunct. That is to say, the RNR target can only be associated with the right edges of each conjunct, as illustrated in (4) and (5) above. This property is formulated in Wilder (1999) as the Right Edge Restriction.

| Right Edge Restriction (Wilder 1999) |

| If α surfaces in the final conjunct, gap(s) corresponding to α must be at the right edge of their non-final conjuncts. |

It is generally assumed that the Right Edge Restriction is a precondition for RNR. The following examples demonstrate how the Right Edge Restriction works in the Chinese RNR.

| [Zhangsan | song-le | Lisi _____ ], | [Wangwu | ye | song-le | Lisi _____ ], |

| Zhangsan | give-Asp | Lisi | Wangwu | also | give-Asp | Lisi |

| yi | ben | shu. | |||||

| one | Cl. | book | |||||

| ‘Zhangsan gave Lisi, and Wangwu also gave Lisi, a book.’ | |||||||

| *[Zhangsan | song-le | ____ | yi | ben | shu], | [Wangwu | ye | song-le | _____ |

| Zhangsan | give-Asp | one | Cl. | book | Wangwu | also | give-Asp |

| yi | ben | shu], | Lisi. |

| one | Cl. | book | Lisi |

| [Zhangsan | mingtian | hui | qu | _____ ], | keshi | [Lisi | mingtian | bu | hui | qu | _____ | ], |

| Zhangsan | tomorrow | will | go | but | Lisi | tomorrow | not | will | go | |||

| canjia | huiyi. | |||||||||||

| participate | conference | |||||||||||

| ‘Zhangsan will, but Lisi will not, go to the conference tomorrow.’ | ||||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan_____ | hui | qu | canjia | huiyi ], | keshi | [Lisi | _____bu |

| Zhangsan | will | go | participate | conference | but | Lisi | not |

| hui | qu | canjia | huiyi ], | mingtian | |||||||||

| will | go | participate | conference | tomorrow |

(11a) and (12a) illustrate that the phrase yi ben shu ‘one book’ or canjia huiyi ‘go to the conference’ is dislocated from the rightmost edge of each conjunct, and it is a legitimate RNR target.[4] On the other hand, (11b) and (12b) show that the ungrammaticality results from a violation of the Right Edge Restriction because the dislocated elements Lisi (the indirect object) and mingtian ‘tomorrow’ (the adjunct) are not dislocated from the rightmost position of the associated conjunct.

Although Chinese RNR sentences exhibit some typical properties like the English RNR, there is also language-particular variation, which has not been documented before, to the best of my knowledge. For example, in (13), although the descriptive, resultative, duration and frequency phrases, i.e., the shared elements, are extracted from the rightmost edge of each conjunct, these sentences are nonetheless ill-formed RNR sentences:[5]

| Descriptive Complement | ||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan | kan | shu | kan-de _____ ], | [Lisi | ye | kan | shu | kan-de | ||

| Zhangsan | read | book | read-de | Lisi | also | read | book | read-de | ||

| _____ ], | hen | kuai. |

| very | fast |

| Resultative Complement | ||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan | kan | shu | kan-de _____ ], | [Lisi | ye | kan | shu | kan-de _____ ], | ||

| Zhangsan | read | book | read-de | Lisi | also | read | book | read-de | ||

| hen | lei. |

| very | tired |

| Duration Phrase | |||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan | kan | shu | kan-le _____ ], | [Lisi | ye | kan | shu | kan-le _____ ], | |||

| Zhangsan | read | book | read-Asp. | Lisi | also | read | book | read-Asp. | |||

| san | ge | xiaoshi. |

| three | Cl. | Hour |

| Frequency Phrase | ||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan | kan | shu | kan-le _____ ], | [Lisi | ye | kan | shu | kan-le _____ ], | ||

| Zhangsan | read | book | read-Asp. | Lisi | also | read | book | read-Asp. | ||

| san ci. | ||||||||||

| three-time | ||||||||||

What sets the sentences in (13) apart from the grammatical RNR sentences is the status of argumenthood. These postverbal elements, despite occupying the typical complement position (as they trigger verb copying due to the Phrase Structural Condition, Huang 1982, 1984a), are not the canonical argument that is s-selected by the verb. Therefore, Chinese actually displays a stronger version of the Right Edge Restriction, which states that non-arguments are prohibited from being the RNR targets in Chinese even if they occur in the right edges.[6] This additional restriction is crucial, but the issue has not been addressed in the literature. An explanation for such a restriction will be discussed in Section 4.

2.2 The prosodic structure of the RNR

It has been claimed that prosodic structures are often mapped from syntactic trees (Selkirk 1984). Therefore, the prosodic structure of the RNR may be regarded as a direct reflection of its syntactic derivation. The syntax-prosody mapping approach is also rooted in Hartmann’s (2000) analysis. In Germanic languages, a pitch accent is easily detected in each conjunct right before the gaps, as in (14a), and the pitch accent (stress) is not allowed on the RNR target, as in (14b):

| [CP … V́ #] and [CP … V́ #] [RNR target] | (#: pause or prosodic boundary) |

| *[CP …V #] and [CP … V #] [RNR target] |

As a result, the tonal contour of the RNR is that the stress falls on the elements immediately preceding the gaps (viz. on the final verb of each conjunct), and the intonation becomes entirely flat on the RNR target. Moreover, there is an intonation pause following the verb in each conjunct, as shown in (14a).

Plausibly, this phonological pause should be regarded as a prosodic boundary. The prosodic structure in (14a) then entails a syntactic structure where the RNR target in the second conjunct is in fact not a complement of its preceding verb, opposite to what the surface form may have suggested.

Although Chinese is different from Germanic languages in not displaying obvious pitch accents, the prosodic boundaries in Chinese can nevertheless be detected by observing the application of the tone sandhi rule. That is, a prosodic boundary can be detected if the tone sandhi rule is blocked. Let me first introduce the tone sandhi rule of Mandarin Chinese, and then move to the prosodic structure of the Chinese RNR constructions. There are four contrastive tones in Mandarin Chinese listed in (15):

| T1: high level | [55] | H | |

| T2: rising | [35] | MH = (R) | |

| T3: dipping | [214] | MLH = (L) | |

| T4: falling | [51] | HL | (from Chen 2000) |

T1–T4 represent the four underlying tonal values, the numbers in the square brackets indicate pitch levels, and the letters stand for high (H), mid (M), rising (R), and low (L) tones. In daily speech, however, the third tone (T3) is often reduced to a low tone (L). In Mandarin, the tone sandhi rule takes place when two (underlying) third tones are adjacent to each other. If so, an underlying T3–T3 (LL) sequence becomes T2–T3 (RL) on the surface, as in (16):

| T3(L) → T2(R)/ ___T3(L). |

As observed in Cheng (1973), Cheng (1987), and Shih (1986) among many others, the Mandarin tone sandhi rule respects the underlying syntactic structure instead of being applied in a way that is entirely based on the surface linear string. For our purpose here, it is important to note that the tone sandhi rule always takes place between a verb and its complement.

|

In general, a verb and its complement are in the same tone sandhi domain, and a third-tone (low-and-rising tone) verb must undergo tone sandhi to a second-tone (rising tone) if its following complement also carries the third tone.

Now let us examine the prosodic boundaries of the Chinese RNR constructions. Observe the contrast between (18) and (19):

|

|

(18) is a typical non-RNR sentence, where the tone sandhi must apply on the verb because the first syllable of its complement carries a low tone. In an RNR sentence like (19), on the other hand, the verb mai ‘buy’ does not undergo tone sandhi before the RNR target. Crucially, the lack of tone sandhi in this configuration indicates that the RNR target, which is adjacent to the second verb on the surface, no longer stays in the complement position of the second verb. As shown on the surface, there are two prosodic boundaries in the Chinese RNR constructions, and they are found at the end of each conjunct.[7] Recall that the RNR constructions are coordinated structures of CPs, and each conjunct is a full clause. As shown in (19), if the RNR target were base generated in the complement position of the second conjunct, then the verb in the second conjunct should have to undergo tone sandhi since the verb and its complement NP would be in the same tone sandhi domain.[8]

2.3 The semantic interpretation of the RNR constructions

In addition to phonological boundaries, it has also been claimed that syntax-prosodic structures are highly associated with information structure. According to Selkirk (1984, 1995, the constituent that is accented receives the focus value. Therefore, it is the elements before the gap that are focused in the corresponding information structure (with stress and rising tonal contour), as illustrated in (14a) above (Hartmann 2000). On the other hand, since the RNR target does not bear any intonation contour, the RNR target is not focused, and it does not carry new information. In other words, the reference of the RNR target can always be retrieved from the prior discourse, or can be entailed from the other conjunct. This condition is known as the GIVENness rule in Schwarzschild (1999):

| The GIVENness Rule of Interpretation |

| If a constituent is not Focus marked, it must be GIVEN. |

Chinese is not a language with a prominent stress system in its phonology. However, we may use the wh-question to show that the Givenness rule also applies to Chinese. Consider (21):

| *Zhangsan | mai-le, | keshi | Lisi | mei | you | mai, | ji | ping | jiu? |

| *Zhangsan | buy-Asp. | but | Lisi | not | have | buy | how.many | Cl. | wine |

| ‘(intended) How many bottles of wine did Zhangsan buy, but Lisi did not buy?’ | |||||||||

Since the interpretation of the RNR targets should be GIVEN, the wh-element is not qualified as an RNR target. Furthermore, (22) shows that a focus-associated element, such as eryi ‘only’ is not allowed to be associated with the RNR target, either:

| *Zhangsan | mai-le, | keshi | Lisi | mei | you | mai, | wu | ping | jiu | eryi. |

| *Zhangsan | buy-Asp. | but | Lisi | not | have | buy | five | Cl. | wine | only |

| ‘(intended) Zhangsan bought, but Lisi did not buy, only five bottles of wine.’ | ||||||||||

The ungrammaticality can be explained if we assume that the focus is carried by the verbs in the coordinated structure, mai ‘buy’ and mei-you mai ‘not buy’, and the RNR target cannot be associated with focus due to the intervention effect (Beck 2006; Kim 2002; Li 2011; Soh 2005; Yang 2008, among others). (21) and (22) therefore clearly indicate that the semantic and pragmatic properties of the Chinese RNR targets are subject to the similar conditions as those in the Germanic languages. In contrast, it is the coordinated structure that bears the focus interpretation. Therefore, we should predict that the wh-elements and focus particle shi ‘be’ are allowed to appear in the coordinated structures. The predictions are borne out, as shown in the following examples:

| shei | yao | mai, | keshi | shei | bu | yao | mai, | na | ping | jiu? |

| who | want | buy | but | who | not | want | buy | that | Cl. | wine |

| ‘Who wants to buy but who doesn’t want to buy, that bottle of wine?’ | ||||||||||

| shi | Zhangsan | mai-le, | bu | shi | Lisi | mai-le, | na | wu | ping | jiu. |

| be* | Zhangsan | buy-Asp. | not | be | Lisi | buy-Asp. | that | five | Cl. | wine |

| ‘It is Zhangsan but not Lisi who bought that five bottles of wine.’ | ||||||||||

Zubizarreta (2010) offers yet another clue for our analysis here. Notice that there is a prosodic boundary at the end of the second conjunct. She proposes that the strong prosodic boundaries are always due to the presence of a functional category.[9] If the idea of Zubizarreta (2010) is on the right track, we may assume a phonologically null functional head, identified as Focus, in the Chinese RNR, and such a functional head not only introduces a prosodic boundary (as evidenced by the Tone Sandhi rule), but it also triggers an overt syntactic movement of the coordinated structure in the Chinese RNR. This analysis then successfully accounts for the prosodic boundaries between the coordinated structure and the RNR target, as well as the focus interpretation of the coordinated structure in the Chinese RNR. The postulation of a focus projection is not arbitrary, but this actually results in the observed word order, where the focused coordinated structure moves across the RNR target.[10] We will come back to this point in Section 4.

To sum up, three general properties of the RNR construction are observed in Chinese. First, the Chinese RNR contains a coordinated structure which requires the conjuncts to be full clauses (CPs), and the shared elements (RNR targets) must respect the Right Edge Restriction. Second, the prosodic boundaries appear at the end of each conjunct. Third, the elements preceding the RNR targets are focused, whereas the RNR target per se must be given (non-focused).

In the next section, two previous analyses will be reviewed carefully, including the PF-deletion approach and the rightward ATB movement approach. It will be shown that neither of the previous approaches is fully adequate in dealing with the properties of the Chinese RNR construction.

3 Previous analyses of the RNR constructions

There has been a debate of whether the RNR construction should involve PF-deletion in the first conjunct (Hartmann 2000; Kayne 1994; Levine 1985; Wexler and Culicover 1980; Wilder 1997), or it is derived through rightward ATB movement (Bresnan 1974; Hudson 1976; Maling 1972; Postal 1974; Ross 1967; Sabbagh 2007). In this section, we show that none of the two analyses may fully account for the RNR construction in Chinese.

3.1 The PF-deletion approach

Among the proponents of the PF-deletion approach, in particular, Hartmann (2000) treats the RNR construction as a type of ellipsis in terms of a symmetric distribution of pitch accents and focus assignment. The main proposal is that the shared element in the non-final conjunct is subject to backward deletion when it does not receive any pitch accent, that is, when it is not focused. The following example illustrates how a RNR sentence under the PF-deletion approach is derived:

| [John

likes

|

In (25), the pitch accent is associated with the verb like (in contrast to dislike in the second conjunct), which immediately precedes the RNR target that car. The accent on the verb may trigger deaccenting of the RNR target, and the deaccenting in turn triggers backward PF-deletion of the RNR target in the first conjunct.

One of the advantages of assuming PF-deletion is that the RNR does not lead to island violation, which has been considered a serious problem of the ATB movement approach. See Examples (26)–(29) (English examples from Abels 2004:5):

| Wh-island |

|

John wonders [when Bob Dylan wrote |

| Mary wants to know [when he recorded his great song about the death of Emmett Till]. |

| (*What does John wonder when Bob Dylan wrote?) |

| Complex NP island |

|

I know a man [who buys |

| you know a woman [who sells gold rings and raw diamonds from South Africa]. |

| (*What do you know a man who sells?) |

| Adjunct island |

| Josh got angry [after he discovered |

| (*What did Josh get angry after he discovered?) |

| Wh-island (Chinese)[11] | ||||||||||

| Zhangsan | xiangzhidao | weishenme, | keshi | Lisi | xiangzhidao | shenme | ||||

| Zhangsan | wonder | why | but | Lisi | wonder | what | ||||

| shihou, | ni | yao | likai. | |||||||

| time | you | want | leave | |||||||

| ‘Zhangsan wonders why, but Lisi wonders when you will leave.’ | ||||||||||

| (*Zhangsan | xiangzhidao | weishenme | shei | yao | likai) | |||||

| Zhangsan | wonder | why | who | want | leave | |||||

| ‘Zhangsan wonders why who wants to leave.’ | ||||||||||

The above examples indicate that the gaps in the sentences are not derived through movement. Another argument for the PF-deletion analysis is that the RNR target allows disjoint reference, as shown in (30):

| John bought |

| Which book i did John buy t i and Mary read t i yesterday? |

The indefinite objects in (30) may refer to different books in the first and second conjuncts as if the object were not deleted. However, as we see in (31), ATB-movement only allows a co-referential reading. The availability of the disjoint reading therefore suggests that an ATB-movement analysis of the RNR construction is not on the right track.

However, there are also problems for the PF-deletion approach. If the RNR construction is derived via PF-deletion, they are supposed to be subject to Merchant’s (2001) e-GIVENness condition, which is specifically designated as a constraint of PF-deletion in general. The definition is given in (32).

| e-GIVENness |

| An expression E counts as e-GIVEN if E has a salient antecedent A and, modulo ∃-type shifting, |

| (i) A entails F-clo(E), and (ii) E entails F-clo(A). |

According to e-GIVENness, the deleted element must have a salient antecedent in the sentence containing it. In all of Merchant’s examples, the antecedent either c-commands or precedes the deleted element. On the contrary, the deleted element in the RNR construction is in the first conjunct. This means that the antecedent (the preceding shared element) undergoes deletion instead. This causes a problem for the PF-deletion approach because PF-deletion will eventually become too powerful. For instance, if PF-deletion can be applied freely, we might wonder why the RNR construction does not have a forward counterpart in English, as shown in (33). And, why can’t we find the backward gapping constructions as illustrated in (34)?

| John likes, but Bill hates his mother. |

| *John likes his mother, but Bill hates. |

| John likes apples, and Bill oranges. |

| *John apples, and Bill likes oranges. |

Furthermore, when we move to the Chinese RNR construction, such as (13), repeated as (35) below, it is again unclear why PF-deletion cannot apply to the following examples even though the shared element obeys Right Edge Restriction, and it has a flat intonation:

| Descriptive Complement | ||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan | kan | shu | kan-de _____ ], | [Lisi | ye | kan | shu | kan-de _____ ], | ||

| Zhangsan | read | book | read-de | Lisi | also | read | book | read-de | ||

| hen | kuai. |

| very | fast |

| Resultative Complement | ||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan | kan | shu | kan-de _____ ], | [Lisi | ye | kan | shu | kan-de _____ ], | ||

| Zhangsan | read | book | read-de | Lisi | also | read | book | read-de | ||

| hen | lei. |

| very | tired |

| Duration Phrase | |||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan | kan | shu | kan-le _____ ], | [Lisi | ye | kan | shu | kan-le _____ ], | |||

| Zhangsan | read | book | read-Asp. | Lisi | also | read | book | read-Asp. | |||

| san | ge | xiaoshi. |

| three | Cl. | hour |

| Frequency Phrase | ||||||||||

| *[Zhangsan | kan | shu | kan-le _____ ], | [Lisi | ye | kan | shu | kan-le _____ ], | ||

| Zhangsan | read | book | read-Asp. | Lisi | also | read | book | read-Asp. | ||

| san | ci. |

| three- | time |

In addition, the PF-deletion approach also fails to explain the tone sandhi boundary between the RNR target and its coordinated structure. Recall that in (19), the RNR target is not base generated in the complement position of its preceding verb, contrary to what the PF-deletion approach claims.

Another crucial counterexample to the PF-deletion approach comes from Jackendoff’s (1977) observation, which concerns RNR targets that contain a relational modifier such as same or different. The relational modifier generally allows distributive readings when it appears in contexts with plural nouns or plural predicates. However, a distributive reading is not available when the relational modifier modifies the RNR target. Consider the contrast between (36) and (37):

| John hummed ___ i , and Mary sang ___ j , the same i=j tune/a different i≠j tune. |

| #John hummed the same tune/a different tune and Mary sang the same tune/a different tune. |

In (36), the same modifies the identical tune that John hummed and Mary sang. Following Carlson (1987), the scope of the relational modifier has to be higher than the coordinated structure so that the tune can be referred to the same one. The same reasoning also applies to the case of different. On the other hand, if the relational modifier is pronounced twice, as we see in (37), the reading is not the same as in (36). Instead, the tunes are not the same/different tunes in relation to each other, but they must make reference to another contextually salient tune (hummed by Bill, for example). If the PF-deletion approach were on the right track, we should predict that (36) and (37) have the same reading. To account for this observation in the RNR constructions, as a result, we may need to go back to the ATB-movement approach.

3.2 The rightward ATB-movement approach

One of the serious problems of the ATB movement approach that we mentioned above is the island insensitivity of the RNR construction. Sabbagh (2007), however, attempts to solve the island problem by adopting the principle of Order Preservation by Fox and Pesetsky (2004):

| Order Preservation |

| The linear ordering of syntactic units is affected by Merge and Move within a Spell-Out Domain, but is fixed once and for all at the end of each Spell-Out Domain. |

Before we see how the principle of Order Preservation works in RNR, let us briefly review the application of Spell-Out in syntax. According to Fox and Pesetsky (2004), the Spell-Out domain is assumed to be vP and CP. When we do linearization at PF, Spell-Out is applied to the complement of the head of the Spell-Out domain. For example, when Spell-Out applies to CP, it is the complement of C, i.e., IP, which is sent to PF for linearization. Similarly, when Spell-Out applies to vP, it is the complement of v, i.e., VP, which is spelled-out. When there is movement, the moved element needs to move to the edge of Phases before Spell-Out applies. Moreover, in order to avoid the island violation, movement has to apply in a successive-cyclic fashion.

Let us first see how the principle of Order Preservation works in the wh-island violation.

|

The wh-movement in (39b) will cause contradictory orders, as we see in (39c). Therefore, the principle of Order Preservation provides an account for the case of island violation. Let us move to rightward movement and see why island violations are obviated:

|

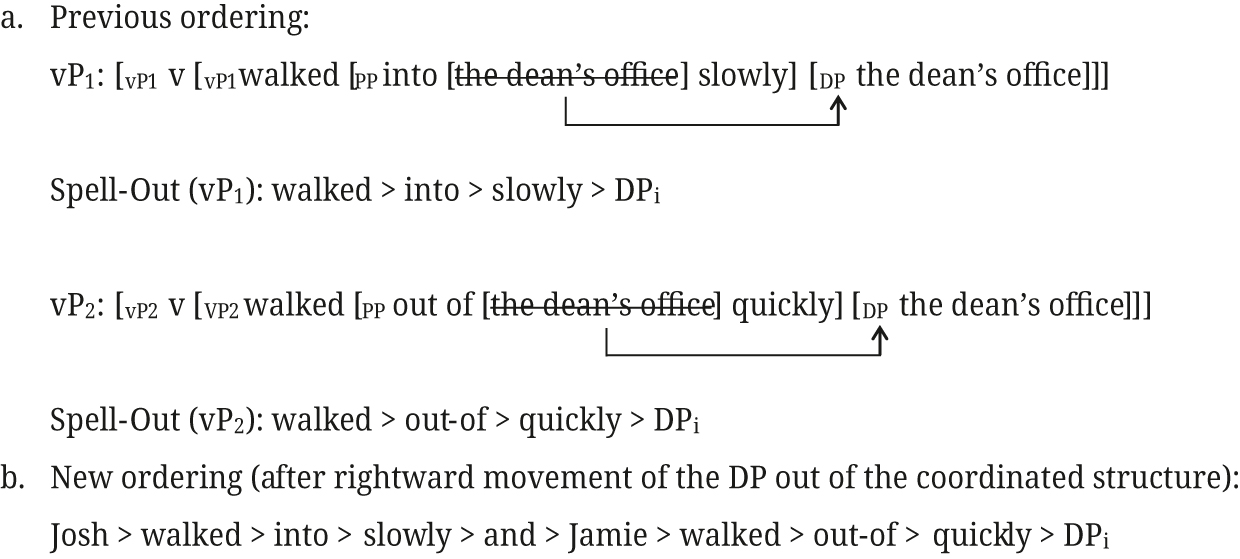

As we see in (40), since there is nothing at the right side of the DP his great song, the rightward movement of the DP his great song will not result in contradictory orders. As a result, there is no island violation. From this perspective, Sabbagh can also use the principle of Order Preservation to derive the same effect of Right Edge Restriction in the RNR construction. If there are some other elements at the right edge within the conjuncts (not the RNR target), the contradictory order occurs immediately when the RNR target undergoes rightward movement to a higher position. To illustrate how the effect of Right Edge Restriction is derived, consider (41) (from Sabbagh 2007: Example (77)):

| *Josh walked into _ slowly, and Jamie walked out of _ quickly, the dean’s office. |

| Previous ordering (before the rightward movement of the DP) |

| Spell-Out(vP1): walked > into > DP i > slowly |

| Spell-Out(vP2): walked > out-of > DP i > quickly |

| Spell-Out(CP1): Josh > VP1 |

| Spell-Out:(CP2): Jamie > VP2 |

| New ordering (after the rightward movement of the DP) |

| CP1 > Conj; Conj > CP2 |

| ConjP[CP] > DPi |

| Josh > walked > into > slowly > and > Jamie > walked > out-of > quickly > DP i |

Before the DP the dean’s office undergoes rightward movement out of the coordinated structure, we have to first spell out the conjuncts (CPs). At this moment, the order between the DP the dean’s office and the adverb slowly/quickly is that the DP precedes the adverb in each conjunct. However, after the DP moves out of the coordinated structure, this creates a new order when Spell-Out applies, in which the DP follows the adverbs. As a consequence, the new ordering contradicts the previous one, and the principle of Order Preservation is violated. Sabbagh therefore concludes that the unbounded rightward movement can still be constrained by the principle of Order Preservation.

The core idea of Sabbagh’s analysis is that rightward movement is unbounded, and it is only restricted by the ordering constraint. The assumption is useful in deriving the Right Edge Constraint, but more careful inspection shows that the assumption may become too powerful. Specifically, if rightward movement is unbounded in the first place, it is unclear what prevents us from moving the DP the dean’s office across the adverb slowly/quickly to the right edge of each conjunct before the vP phases are spelt out? Consider (42) for illustration:

|

The DP follows the adverbs after final Spell-Out, and their orderings are preserved. As a result, we should predict that the unbounded rightward movements within conjuncts should have come to the rescue of the contradictory orders observed in the previous example (41).[12] In other words, Sabbagh’s attempt to derive the Right Edge Restriction from the Order Preservation may involve more complications than he originally proposed. It is therefore concluded that the ATB-movement approach to RNR constructions is not fully adequate, either.

Moreover, recall that the descriptive, resultative, duration, and frequency phrases in Chinese follow the VP in general, but these pseudo-arguments cannot be the RNR target even though each of them is located at the right edge of the conjuncts in the RNR construction. As a result, the rightward ATB-movement approach cannot be adopted to account for the Chinese RNR, either.

4 Proposal: true empty category + focus dislocation

So far, we have shown that none of the existing analyses can provide a fully satisfactory account. This may be largely due to the paradoxical properties of the RNR construction, and therefore, each analysis may only account for a subset of phenomena associated with the Chinese RNR construction. The paradox calls for an alternative analysis. To this end, I argue that the empty noun in Panagiotidis (2003) and Li’s (2005, 2007, and 2014) proposal of the True Empty Category (TEC) may provide a solution to this impasse, and I will defend such an analysis with the properties of the Chinese RNR construction. In addition, I will further argue that the apparent ‘rightward’ dislocation of the RNR target actually derives from a ‘leftward’ movement of the coordinated structure (through focus fronting), for which the particular prosodic pattern of the RNR construction will be taken as evidence. Specifically, I propose that the derivation of the Chinese RNR construction should consist of the following two steps:

|

(43a) illustrates the underlying structure of the RNR construction, where both the RNR target (situated in a higher functional position) and the empty objects are generated in their base positions. Li’s (2005, 2007, 2014) analysis of the true empty category and its application in the RNR construction will be discussed in Sections 4.1 and 4.2.[13] Example (43b) shows that the surface order of the RNR construction is derived through leftward focus movement of the coordinated structure. Such movement is motivated by prosodic structure and information structure, as proposed by Cheung (2009), and Cheung’s analysis will be discussed in Section 4.3.

4.1 Beyond movement and deletion

In Li’s (2005, 2007, 2014) study on Chinese empty categories, she has demonstrated that the empty object construction in Chinese have met a similar problem like the RNR construction. That is, empty objects are not derived through syntactic movement or through PF-deletion. Her analysis is summarized as follows.

Empty categories are widely used in Chinese in a seemingly unrestricted fashion. Huang (1984b), however, has demonstrated that the empty category (a big small Pro in Huang’s term) in the subject position should be constrained by the Generalized Control Rule (GCR): The empty subject has to be coindexed with the closest c-commanding nominal phrase. See (44).

| Lisi i , | [[Pro i | kan | de | shu] | bu | duo]. |

| Lisi | Pro | read | De | book | not | plenty |

| ‘Lisi, the books he reads are not many.’ | ||||||

| Lisi i , | wo | yinwei | [ta i /*Pro i | bu | lai] | hen | shiwang. |

| Lisi | I | because | he/Pro | not | come | very | disappointed |

| ‘Lisi, I am disappointed because he doesn’t want to come.’ | |||||||

(44b) shows that the empty subject has to be coindexed with the nearest possible antecedent (i.e., the first person pronoun), in accordance with the GCR. However, the GCR cannot apply to the empty object (represented here as e); otherwise, a violation of Binding Principle B ensues, as show in (45a):

| *Lisi i | da | ei. |

| *Lisi | hit | e |

| ‘(intended) Lisi hit himself.’ | ||

| Lisi i | jiao | Zhangsan j | bie | da | ei/*j/k. |

| Lisi | ask | Zhangsan | not | hit | e |

| ‘Lisi asked Zhangsan not to hit him.’ | |||||

(45b) also confirms the fact that the empty object is not governed by GCR since it is not co-indexed with the nearest antecedent (i.e., Zhangsan). As a result, empty objects cannot be Pro on a par with empty subjects, nor can empty objects be treated as a variable/trace left by syntactic movements. The reason for the latter is that as shown in (45b), empty objects can be A-bound by the subject of the matrix clause (when no movement is involved).[14]

Since the empty object is neither a pronoun nor a variable, Li (2005, 2007, 2014) and Aoun and Li (2008) argue that we need a new type of empty category, and the empty object should be analyzed as a True Empty Category (TEC). Such a proposal is also reminiscent of the empty noun analysis of Panagiotidis (2003). According to Li (2005, 2007, 2014) and Aoun and Li (2008), TEC is not a lexical item, and it does not participate in the syntactic derivation. On the other hand, TEC is more like a (skeletal) syntactic position that is solely driven by interpretative requirements at LF (namely, subcategorization frames of verbs), and it is interpreted through LF copying (from the antecedent back to the empty position). By definition, then, TEC does not involve movement or deletion, and for our purpose here, adopting TEC clearly provides an alternative route out of the dilemma in the previous analyses.

Let us examine more evidence why TEC does not involve PF-deletion by looking at the Missing Object Constructions (MOC) in Chinese (Aoun and Li 2008). MOC refers to a sentence like the following, where there is no object in the second conjunct:

| Zhangsan | chi-le | san | ke | li, | Lisi | ye | chi-le | e. |

| Zhangsan | eat-Asp | three | CL | pear | Lisi | also | eat-Asp | |

| ‘Zhangsan ate three pears, and Lisi did (eat other three pears), too.’ | ||||||||

Aoun and Li (2008) show that MOC cannot be treated as an instance of the VP-ellipsis construction, which involves PF-deletion of the whole VP, including the VP-level modifier. One of the crucial findings, however, is that the MOC in (47) does not necessarily contain the adjunct in the unpronounced part, unlike the VP-ellipsis sentence in (48):

| tamen | jian-guo | Lisi | san-ci; | Wangwu | ye | jian-guo |

| they | see-Asp | Lisi | three-time | Wangwu | also | see-Asp |

| (dan | zhi | jian-guo | yi-ci). | |||||||

| but | only | see-Asp | one-time | |||||||

| ‘They have met Lisi for three times; Wangwu has also met Lisi (but only once).’ | ||||||||||

| tamen | jian-guo | Lisi | san-ci; | Wangwu | ye | shi | #(dan | zhi | jian-guo | yi-ci) |

| they | see-Asp | Lisi | three-time | Wangwu | also | Aux | but | only | see-Asp | one-time |

| ‘They have met Lisi for three times; Wangwu also did #(but only once).’ | ||||||||||

In the VP-ellipsis sentence like (48), the frequency phrase must be contained in the deleted part. However, in an MOC, the frequency phrase is excluded from the unpronounced part. This indicates that the only the object is missing. A PF-deletion approach will run into difficulties explaining the contrast in (47) and (48) because it is unclear what restricts the deletion to the object NP only, but not to the adjunct NP in (47).

Another piece of evidence against the PF-deletion comes from the following examples (from Li 2011: 10):

| ta | nian | shu | nian | san ci/tian | le; | wo | ye | nian | le | *(san ci/tian) |

| he | read | book | read | three-time/day | Asp | I | also | read | Asp | (three-time/day) |

| ‘He read books three times/days; I also read.’ | ||||||||||

| ta | nian | shu | nian-de | hen | kuai; | wo | ye | nian | *(de hen kuai) |

| he | read | book | read-DE | very | fast | I | also | read | (DE very fast) |

| ‘He reads books fast; I also read.’ | |||||||||

| ta | nian | shu | nian-de | hen | lei; | wo | mei | nian *(de hen lei) |

| he | read | book | read-DE | very | tired | I | not | read (DE very tired) |

| ‘He read books and became tired; I did not read.’ | ||||||||

According to Lobeck (1995), PF-deletion is permitted when the deleted elements are lexically governed by a head. On the other hand, although the frequency, duration, descriptive, and resultative phrases in Chinese satisfy all the conditions for PF-deletion, they cannot be deleted. This indicates that resorting to PF-deletion cannot fully deal with MOC. Since the only element that can be omitted/elided is the subcategorized object, adopting TEC is more theoretically adequate and restricted.

To sum up, we have shown that the missing object in Chinese cannot be derived through syntactic movement or PF-deletion. TEC, however, helps solve the tension between the movement and deletion approaches, and at the same time, it sheds new light upon the MOC in Chinese. In the next subsection, I attempt to adopt TEC to account for the Chinese RNR construction.

4.2 TEC in Chinese RNR

Different from the rightward ATB-movement approach and the PF-deletion approach, we propose a schematized structural representation of the Chinese RNR construction in (50), in which the gaps are analyzed as the TEC:

| [[S V ei(=TEC) ] + conj. + [S V ei(=TEC) ]]j, RNR targeti […]j |

The structure in (50) suggests that the RNR target is base generated in a position independent of the coordinated structure. Therefore, TECs in (50) are not the same as traces left by rightward ATB-movement. To recapitulate, a TEC simply occupies a position in order to satisfy the subcategorization requirement of verbs.[15] As for the referential properties of TECs, they can be obtained through LF-copying from the antecedent or the discourse context. Recall that the information of the RNR targets has to be given, which can be identified as a Topic-like element. As a result, the references of TECs are obtained through copying the topic-like reference of the RNR target.

If (50) is on the right track, not only will the properties of the RNR be well captured, but the problems of the previous analyses may also be solved. First, since the RNR targets are base generated, the problem of island insensitivity is accounted for. Second, since the subcategorization requirement of the TEC must be satisfied in the Chinese RNR construction, the proposal also accounts for why the descriptive, resultative, duration, and frequency phrases cannot be the RNR target (although these phrases are at the right edge of the conjunct).[16] The reason is that these phrases are not canonical arguments that are subcategorized by the verb. Third, the TEC obtains its reference through LF-copying, meaning that the TEC per se lacks any interpretation. The mechanism provides an explanation for why the reference of the TEC is more flexible than traces. In other words, we can account for the disjoint reference of the TEC in the RNR construction, as in (51):

| Zhangsan | xiang | mai | e tec , | Lisi | ye | xiang | mai | e tec , | yi | ben | shu |

| Zhangsan | want | buy | Lisi | alo | want | buy | one | Cl. | book | ||

| ‘Zhangsan | wants to buy a book, and Lisi also wants to buy one.’ (different books) | ||||||||||

Moreover, we also predict that the sloppy reading is plausible in the RNR:

| Zhangsan i | hen | zunjing | e tec , | Lisi j | ye | hen | zunjing | e tec , | ta i/j/k | de | laoshi |

| Zhangsan | very | respect | Lisi | also | very | respect | he | DE | teacher |

| ‘Zhangsan respects Zhangsan teacher, and Lisi also respects Zhangsan’s teacher.’ (strict reading) |

| ‘Zhangsan respects Zhangsan teacher, and Lisi also respects Lisi’s teacher.’ (sloppy reading) |

If the gaps were Pro or A′-variables bound by the RNR target, their references should be identical. The flexible interpretations of the gaps in the RNR construction indicate again that they should not involve syntactic movement, but their interpretations are simply recovered by LF copying.

Next, I show that the interpretative mechanism of the TEC allows us to account for the problems related to relational modifiers and anaphoric binding, which can hardly be explained by the ATB-movement or PF-deletion accounts. First, the problem of the relational modifiers same/different in the RNR target can be solved because the position of the RNR target is base generated outside the coordinated structure, and the RNR target may take scope over the coordinated structure, as shown in (53):

| [∃!x: x is a tune][John hummed x and Mary sang x] |

| [∃x, y: x and y are tunes, and x≠y][John hummed x and Mary sang y] |

(53) gives us the intended interpretation at LF: The tune that John hummed is the same tune as or a different tune from the one that the Mary sang. Such a scope relation can be captured in the TEC approach in (54). Notice that the LF-copying can either be full or partial (only tune is copied) since partial copying is already enough to satisfy the subcategorization requirement of the verb. Therefore, in (54) TECs are realized by partial LF-copying of the RNR target, excluding the relational modifier, to the argument positions:

| [The same tune x ] [John hummed tune x and Mary sang tune x ] |

| [Different tunes x, y ] [John hummed tune x and Mary sang tune y ] |

Since the relational modifier is not part of the core theta component of the argument NP that needs to be copied, the problem related to the relational modifier can be neutralized.

Let us turn to the problem related to anaphoric binding. As is well known, in the double object construction like (55), the indirect object c-commands the direct object when the indirect object precedes the direct object containing the anaphor. When the anaphor precedes its binder, the sentence becomes ungrammatical because the anaphor is not bound:

| wo | song | gei | Lisi i | yi | zhang | taziji i | de | zhaopian. |

| I | give | to | Lisi | one | Cl. | himself | de | picture |

| ‘I gave Lisi a picture of himself.’ | ||||||||

| (cf. *wo song yi zhang tazijii de zhaopian gei Lisii) | ||||||||

The situation becomes more complicated when we put the double object construction into the RNR construction:

| wo | song | gei | Lisi i | e tec , | danshi | ni | song | gei | Zhangsan j | e tec , |

| I | give | to | Lisi | but | you | give | to | Zhangsan |

| yi | zhang | taziji i/j | de | zhaopian | e tec , | ||||||||||

| one | Cl. | himself | de | picture | |||||||||||

| ‘I gave Lisi, but you gave Zhangsan, a picture of himself.’ | |||||||||||||||

When the anaphor sits within the RNR target, the sentence may have a sloppy reading in which taziji refers to Lisi and Zhangsan. Such a sloppy reading indicates that both Lisi and Zhangsan should be able to bind the reflexive contained by the RNR target at LF (although on the surface structure, the antecedent does not c-command the RNR target). Furthermore, in the case of the bound variable pronoun, either the sloppy or the strict reading is possible:

| wo | song | gei | meigeren i | e tec , | ni | ye | song | gei | meigeren i | e tec , | yi | zhang | ta i/j |

| I | give | to | everyone | you | also | give | to | everyone | one | Cl. | he |

| de | zhaopian. | ||||||||||||||

| de | picture | ||||||||||||||

| ‘I gave everyone, and you also gave everyone, a picture of his.’ | |||||||||||||||

Let us assume that Condition A and bound variable binding apply at LF (after LF reconstruction or LF copying) (Chomsky 1995; Lebeaux 2009). In (56), the occurrence of a reflexive, which requires binding, drives the full LF-copy of the RNR target to the TEC. After full LF-copying the anaphors are bound in the conjuncts by Lisi and Zhangsan, respectively. On the other hand, in (57), whether partial copying or full copying is adopted depends on the status of the pronoun. If the pronoun is a full pronoun, which refers to an entity j (referring to a salient entity in the context), then only picture is partially copied to the conjunct, and we obtain the strict reading. If the pronoun is a variable pronoun, then due to its binding requirement, full LF-copying will be adopted, and the bound variable pronoun is bound by everyone in each conjunct, resulting in the sloppy reading.[17]

So far, we have demonstrated that adopting the TEC approach not only helps us to account for the properties of the RNR construction (i.e., no island violation) but the TEC approach may also avoid the problems of previous analyses (i.e., disjoint references and relational modifiers).

4.3 Focus movement in Chinese RNR

Two issues are pending. One concerns the question of why a prosodic boundary occurs and blocks the application of relevant tone sandhi rule in the Chinese RNR construction. The other issue is how to derive the focus interpretation of the coordinated part. Recall that (21)–(24), repeated below as (58)–(61), show that it is the element in the coordinated structure, not the RNR target, that receive focus in the Chinese RNR construction:

| *Zhangsan | mai-le, | keshi | Lisi | mei | you | mai, | ji | ping | jiu? |

| *Zhangsan | buy-Asp. | but | Lisi | not | have | buy | how.many | Cl. | wine |

| ‘(intended) How many bottles of wine did Zhangsan buy, but Lisi did not buy?’ | |||||||||

| *Zhangsan | mai-le, | keshi | Lisi | mei | you | mai, | wu | ping | jiu | eryi . |

| *Zhangsan | buy-Asp. | but | Lisi | not | have | buy | five | Cl. | wine | only |

| ‘(intended) Zhangsan bought, but Lisi did not buy, only five bottles of wine.’ | ||||||||||

| shei | yao | mai, | (keshi) | shei | bu | yao | mai, | na | ping | jiu? |

| who | want | buy | but | who | not | want | buy | that | Cl. | wine |

| ‘Who wants to buy and who doesn’t want to buy, that bottle of wine?’ | ||||||||||

| shi | Zhangsan | mai-le, | bu | shi | Lisi | mai-le, | na | wu | ping | jiu. |

| be* | Zhangsan | buy-Asp. | not | be | Lisi | buy-Asp. | that | five | Cl. | wine |

| ‘It is Zhangsan but not Lisi who bought that five bottles of wine.’ | ||||||||||

Given the condition that stress assignment is not apparent in Chinese (in contrast to the Germanic languages), we need to know what mechanism is responsible for deriving the focus assignment in the Chinese RNR construction. With respect to this problem, I argue that the Chinese RNR construction can be compared to the Dislocation Focus Constructions (DFC) in Cheung’s (2009) analysis.

The canonical word order in Chinese is that a clausal complement, followed by a sentence-final particle, appears after the matrix verb, as in (62a). In DFC, on the other hand, the clausal complement along with the particle is fronted altogether to the sentence-initial position, as illustrated in (62b).

| ni | juede | [[Zhangsan | hui-bu-hui | lai] | ne]? | (Canonical word order) |

| you | think | Zhangsan | will-not-will | come | Q | |

| ‘Do you think whether Zhangsan will come or not?’ | ||||||

| [[ Zhangsan | hui-bu-hui | lai] | ne ], | ni | juede? | (DFC) |

| Zhangsan | will-not-will | come | Q | you | think | |

| ‘Do you think whether Zhangsan will come or not?’ | ||||||

According to Cheung, the non-canonical word order results from focus fronting of the part that carries information focus (É. Kiss 1998). One piece of evidence for the focus feature of the fronted part comes from the wh-question. Since the wh-phrase (and its answer) always represents the focus in a sentence, non-focused parts (which do not include the wh-phrase and its answer) cannot be fronted. The condition can be illustrated by the contrasts between (63) and (64):

| Question: | ||

| Zhangsan | mai-le | shenme ? |

| Zhangsan | buy-Asp | what |

| ‘What did Zhangsan buy?’ | ||

| Answer: |

| Zhangsan | mai-le | na | tai | che. | (Canonical word order) |

| Zhangsan | buy-Asp | that | Cl. | car | |

| ‘Zhangsan bought that car.’ | |||||

| mai-le | na | tai | che , | Zhangsan. | (DFC) |

| buy-Asp | that | Cl. | car, | Zhangsan |

| na | tai | che , | Zhangsan | mai-le. | (DFC) |

| that | Cl. | car | Zhangsan | buy-Asp |

| Question: | ||||

| shei | mai-le | yi | tai | che? |

| who | buy-Asp | one | Cl. | car |

| ‘who bought a car?’ | ||||

| Answer: |

| Zhangsan | mai-le | na | tai | che. | (Canonical word order) |

| Zhangsan | buy-Asp | that | Cl. | car | |

| ‘Zhangsan bought that car.’ | |||||

| # | [mai-le | na | tai | che], | Zhangsan. | |

| buy-Asp | that | Cl. | car, | Zhangsan | ||

| (DFC) → focus excluded in the fronted part | ||||||

| # | [na | tai | che], | Zhangsan | mai-le. | |

| that | Cl. | car | Zhangsan | buy-Asp | ||

| (DFC) → focus excluded in the fronted part | ||||||

In (63a), the wh-object is focused. The forms of the answers can be either a canonical one, in which the object remains in situ, or a DFC, in which the focused object is contained in the fronted part. However, if the subject is a wh-phrase in (64), the DFC sentences are not felicitous because the answers, or the focused elements, are not contained in the fronted parts. Another piece of evidence for focus fronting comes from the prosodic behavior of the DFC. As in other constructions that involve focus fronting, the focus movement in DFC always generates a prosodic boundary right after the moved part, and the intonation of in-situ (non-focused) parts must remain low and flat. This is reminiscent of Zubizarreta’s (2010) proposal. She proposes that the Focus head, which is a functional projection, always results in an insertion of a prosodic boundary (#). In other words, the prosodic boundary is viewed as a byproduct of the focus movement.

Following the analysis in the DFC, I propose that the Chinese RNR construction may also involve the same derivation, which is shown as follows:

|

On the surface, the RNR target always appears after the coordinated structure. I argue that such word order is derived from the entire coordinated structure moving across the RNR target, i.e., the leftward focus movement of the coordinated structure. In addition, the focus movement also generates a prosodic boundary between the coordinated structure and the RNR target. As predicted, the intonation of the RNR target must be low and flat. The derivation in (65) also provides a quick solution to the blocking of tone sandhi rule in RNR sentences. Since the focus movement creates a prosodic boundary, the tone sandhi rule is interfered by the prosodic boundary between the verb and the RNR target.

Two reviewers raise the question of why unlike DFC, in which the Sentence Final Particle (SFP) appears in the middle of the sentence, the SFP can appear at the end of the RNR sentence. Cheung (2009), Pan (2022), and Simpson and Wu (2002) assume that the SFP in Chinese is underlyingly head-initial in the CP domain, and the syntactic constituents following the SFP may be attracted to its specifier position to derive the surface word order. It has been noted that the SFP may appear in two possible positions on the surface. One is in the sentence-final position, as in the case of IP-raising (66a), and the other is in the sentence-internal position, as in the case of the DFC (66b). Note that in the DFC, the β part can be of any kind of syntactic category, and the α part is the remnant.

| SFP α β | → | a. | [[α β] SFP] |

| b. | [[β SFP] α] |

Just like the derivation in the DFC in (66b), I assume that it is the coordinated structure that moves to the specifier position of the SFP in the RNR construction, and the surface word order is thus obtained in (67):

| SFP α β → [[β SFP] α] | |||||||||||

| SFP [RNR target] [coordinated structure] → [[coordinated structure] SFP] [RNR target] | |||||||||||

| Zhangsan | yao | mai, | kehsi | Lisi | bu | yao | mai | ya, | wo-de | fangzi. | |

| Zhangsan | want | buy | but | Lisi | not | want | buy | SFP | my | house | |

| ‘Zhangsan wants to buy, but Lisi does not want to buy, my house.’ | |||||||||||

However, the reviewers correctly point out that the SFP can also appear in the sentence final position, i.e., after the RNR target, as in (68). This seems to pose a serious problem if we assume that the word orders of the RNR construction and DFC are derived in the same fashion. Specifically, the SFP is not expected to appear at the end of the RNR sentence.

| SFP α β → [[β] [α SFP]] | ||||||||||

| SFP [RNR target] [coordinated structure] → [coordinated structure] [[RNR target] SFP] | ||||||||||

| Zhangsan | yao | mai, | kehsi | Lisi | bu | yao | mai, | wo-de | fangzi | ya. |

| Zhangsan | want | buy | but | Lisi | not | want | buy | my | house | SFP |

| ‘Zhangsan wants to buy, but Lisi does not want to buy, my house.’ | ||||||||||

To account for the word order in (68), the following derivation is therefore proposed.

| [SFP, [RNR target], [[coordinated structure]]] |

| Step 1 → [RNR target] SFP], [[coordinated structure]]] |

| Step 2 → [[[coordinated structure]], [RNR target SFP]] |

First, the RNR target moves as a whole to the specifier of the SFP, and then the coordinated structure moves across over the combination of the RNR target and the SFP. As a result, the SFP appears at the end of the sentence. The reason why the RNR target can be moved to the specifier of the SFP is that the RNR target per se is a syntactic constituent. However, it is not clear whether movement of the RNR target is also triggered by the focus interpretation, and I shall leave the question for future investigation. Moreover, unlike DFC, in which the SFP seems to only appear in a sentence-internal position, the SFP in the RNR construction can be located in either the sentence-internal or sentence-final positions. The reason may be attributed to whether the moved item is a syntactic constituent. In the RNR construction, the RNR target is a syntactic constituent, so it can be moved to the specifier of the SFP. In the DFC, however, the remnant α part is not always a well-formed syntactic constituent so it cannot be moved like the RNR target. As a result, the surface position of the SFP in these two constructions may have different patterns.

5 Conclusions

This article has argued that RNR does exist in Chinese, and it is subject to the same Right Edge Restriction and displays similar properties as those found in Germanic languages with respect to their syntactic, prosodic and information structural properties. Two language-particular properties of the Chinese RNR construction have been discussed. First, the Chinese RNR construction displays an argument/adjunct asymmetry, in which only the argument can surface as the RNR target. Second, since Chinese lacks a stress system, the tone sandhi boundary is employed to identify the prosodic structure. The properties of the Chinese RNR construction, however, lead us to a dilemma of the previous movement/deletion approaches. Hence, I argue that Panagiotidis’s empty noun and Li’s proposal of the True Empty Category may shed new light on this impasse by introducing a new type of empty category, which relies on the syntactic subcategorization frame and the LF-copying mechanism. Following the analysis of empty nouns, the RNR target is base generated outside the coordinated structures in an RNR sentence, and therefore, Li’s analysis neutralizes the differences between movement and deletion approaches. I then show that the apparent rightward movement is a result of leftward focus movement of the coordinated structure over the RNR target. Such movement can be subsumed under the Dislocation Focus Construction in Cheung (2009), which may account for the prosodic and information structural properties of the RNR construction in Chinese.

Acknowledgments

This article is an extension of my dissertation. Earlier versions were presented at IACL-21 and at GLOW in Asia X and I am grateful to both audiences for their inspiring questions and feedback. I also thank Audrey Li for her invaluable input, and I very much appreciate Roger Liao’s detailed comments on the draft of the present article. Finally, I am deeply grateful to the Editorial Board and the two anonymous reviewers of Linguistics for their insightful questions and constructive comments. All remaining errors are mine.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2003. Successive cyclicity, anti-locality, and adposition stranding. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Abels, Klaus. 2004. Right node raising: Ellipsis or ATB movement? North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 34. 44–59.Search in Google Scholar

Aoun, Joseph & Yen-hui Audrey Li. 2003. Essays on the representational and derivational nature of grammar: The diversity of wh-constructions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/2832.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Aoun, Joseph & Yen-hui Audrey Li. 2008. Ellipsis and missing objects. In Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero & Maria Luisa Zubizarreta (eds.), Foundational issues in linguistic theory, 251–274. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/7713.003.0013Search in Google Scholar

Beck, Sigrid. 2006. Intervention effects follow from focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 14. 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-005-4532-y.Search in Google Scholar

Bresnan, Joan. 1974. The position of certain clause-particles in phrase structure. Linguistic Inquiry 5. 614–619.Search in Google Scholar

Carlson, Gregory. 1987. Same and different: Some consequences for syntax and semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy 10. 531–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00628069.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Matthew. 2000. Tone sandhi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486364Search in Google Scholar

Cheng, Chin-Chuan. 1973. A synchronic phonology of Mandarin Chinese. The Hague: Mouton.10.1515/9783110866407Search in Google Scholar

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 1987. Derived domains and Mandarin third tone sandhi. Paper presented at the Chicago Linguistic Society 23, Parasession on Autosegmental and Metrical Phonology, Chicago.Search in Google Scholar

Cheung, Lawrence. 2009. Dislocation focus construction in Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 18. 197–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-009-9046-z.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

den Dikken, Marcel. 2006. Relators and linkers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/5873.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

É. Kiss Katalin. 1998. Identificational focus versus information focus. Language 74. 245–273. https://doi.org/10.2307/417867.Search in Google Scholar

Fox, Danny & David Pesetsky. 2004. Cyclic spell-out, ordering and the typology of movement. Theoretical Linguistics 31. 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1515/thli.2005.31.1-2.235.Search in Google Scholar

Hartmann, Katharina. 2000. Right node raising and gapping: Interface conditions on prosodic deletion. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.106Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Cheng-Teh James. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Cheng-Teh James. 1984a. Phrase structure, lexical integrity, and Chinese compounds. Journal of Chinese Language Teachers Association 14. 53–78.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Cheng-Teh James. 1984b. On the distribution and reference of empty pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 15. 521–574.Search in Google Scholar

Hudson, Richard. 1976. Conjunction reduction, gapping, and right node raising. Language 52. 535–562. https://doi.org/10.2307/412719.Search in Google Scholar

Jackendoff, Ray. 1977. X-bar syntax: A study of phrase structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kentner, Gerrit, Caroline Féry & Kai Alter. 2008. Prosody in speech production and perception: The case of right node raising in English. In Anita Steube (ed.), The discourse potential of underspecified structures, 207–226. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110209303.3.207Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Shin-Sook. 2002. Intervention effects are focus effects. Japanese/Korean Linguistics 10. 615–628.Search in Google Scholar

Lebeaux, David. 2009. Where does binding theory apply? Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9780262012904.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Levine, Robert D. 1985. Right node (non-)raising. Linguistic Inquiry 16. 492–497.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Haoze. 2011. Focus intervention effects in Mandarin. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Yen-hui Audrey. 1987. Duration phrases: Distributions and interpretation. Journal of Chinese Language Teachers Association 22. 27–65.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Yen-hui Audrey. 2005. VP-ellipsis and null objects. Linguistic Sciences 15. 3–19.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Yen-hui Audrey. 2007. Beyond empty categories. Bulletin of the Chinese Linguistic Society of Japan 254. 74–106. https://doi.org/10.7131/chuugokugogaku.2007.74.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Yen-hui Audrey. 2014. Born empty. Lingua 151. 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2013.10.013.Search in Google Scholar

Liao, Wei-wen Roger. 2004. The architecture of aspect and duration. Hsinchu: National Tsing Hua University MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Chin Ting & Li Mei Chen. 2020. Testing the applicability of third tone sandhi at the intonation boundary: The case of the monosyllabic topic. Language and Linguistics 21. 636–651. https://doi.org/10.1075/lali.00073.liu.Search in Google Scholar

Lobeck, Anne. 1995. Ellipsis: Functional heads, licensing and identification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195091816.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Maling, Joan. 1972. On gapping and the order of constituents. Linguistic Inquiry 3. 101–108.Search in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and identity in ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199243730.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Pan, Victor Junnan. 2022. Deriving head-final order in the peripheral domain of Chinese. Linguistic Inquiry 53(1). 121–154.10.1162/ling_a_00396Search in Google Scholar

Panagiotidis, Phoevos. 2003. One, empty nouns, and (theta)-assignment. Linguistic Inquiry 34(2). 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2003.34.2.281.Search in Google Scholar

Postal, Paul. 1974. On raising. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, John. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Sabbagh, Joseph. 2007. Ordering and linearizing rightward movement. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25. 349–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-006-9011-8.Search in Google Scholar

Schwarzschild, Roger. 1999. GIVENness, AvoidF and other constraints on the placement of accent. Natural Language Semantics 7. 141–177. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008370902407.10.1023/A:1008370902407Search in Google Scholar

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1984. Phonology and syntax: The relation between sound and structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1995. Sentence prosody: Intonation, stress, and phrasing. In John A. Goldsmith (ed.), The handbook of phonological theory, 550–569. London: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Shih, Chi-lin. 1986. The prosodic domain of tone sandhi in Chinese. San Diego, CA: University of California, San Diego dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Simpson, Andrew & Zoe Wu. 2002. IP-raising, tone sandhi and the creation of sentence-final particles. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 11. 67–99. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1013710111615.10.1023/A:1013710111615Search in Google Scholar

Soh, Hooi Ling. 2005. Wh-in-situ in Mandarin Chinese. Linguistic Inquiry 36. 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2005.36.1.143.Search in Google Scholar

Tsai, Wei-Tien Dylan. 2002. Yi, er, san [one, two, three]. Yuyanxue Luncong [Journal of Linguistics] 26. 301–312.Search in Google Scholar

Wexler, Kenneth & Peter W. Culicover. 1980. Formal principles of language acquisition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wilder, Chris. 1997. Some properties of ellipsis in coordination. In Artemis Alexiadou & T. A. Hall (eds.), Studies on Universal Grammar and typological variation, 59–107. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.13.04wilSearch in Google Scholar

Wilder, Chris. 1999. Right node raising and the LCA. WCCFL 18. 586–598.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, Barry. 2008. Intervention effects and covert component of grammar. Hsinchu: National Tsing Hua University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Yin, Hui. 2003. The blocking of tone sandhi in Mandarin Chinese. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1–4 June, 2003.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Ning. 1997. The avoidance of the third tone sandhi in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 6. 293–338. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008232121848.10.1023/A:1008232121848Search in Google Scholar

Zubizarreta, Maria Luisa. 2010. The syntax and prosody of focus: The Bantu-Italian connection. IBERIA: An International Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 2. 131–168.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Right node raising in Mandarin Chinese: are we moving right?

- A structural and functional comparison of differential A and P indexing

- Inanimate antecedents of the Japanese reflexive zibun: experimental and corpus evidence

- Prediction in SVO and SOV languages: processing and typological considerations

- Fragment answers with negative dependencies in Korean: a direct interpretation approach

- The particle suo in Mandarin Chinese: a case of long X0-dependency and a reexamination of the Principle of Minimal Compliance

- On the property-denoting clitic ne and the determiner de/di: a comparative analysis of Catalan and Italian

- On Italian spatial prepositions and measure phrases: reconciling the data with theoretical accounts

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Right node raising in Mandarin Chinese: are we moving right?

- A structural and functional comparison of differential A and P indexing

- Inanimate antecedents of the Japanese reflexive zibun: experimental and corpus evidence

- Prediction in SVO and SOV languages: processing and typological considerations

- Fragment answers with negative dependencies in Korean: a direct interpretation approach

- The particle suo in Mandarin Chinese: a case of long X0-dependency and a reexamination of the Principle of Minimal Compliance

- On the property-denoting clitic ne and the determiner de/di: a comparative analysis of Catalan and Italian

- On Italian spatial prepositions and measure phrases: reconciling the data with theoretical accounts