Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

-

Emiko Takeoka

, Shizuko Akiyama

Abstract

Objectives

Maternal obesity increases a child’s risk of neurodevelopmental impairment. However, little is known about the impact of maternal obesity on fetal brain development.

Methods

We prospectively recruited 20 healthy pregnant women across the range of pre-pregnancy or first-trimester body mass index (BMI) and performed fetal brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of their healthy singleton fetuses. We examined correlations between early pregnancy maternal BMI and regional brain volume of living fetuses using volumetric MRI analysis.

Results

Of 20 fetuses, there were 8 males and 12 females (median gestational age at MRI acquisition was 24.3 weeks, range: 19.7–33.3 weeks, median maternal age was 33.3 years, range: 22.0–37.4 years). There were no significant differences in clinical demographics between overweight (OW, 25≤BMI<30)/obese (OB, BMI≥30 kg/m2) (n=12) and normal BMI (18.5≤BMI<25) (n=8) groups. Fetuses in the OW/OB group had significantly larger left cortical plate (p=0.0003), right cortical plate (p=0.0002), and whole cerebellum (p=0.049) compared to the normal BMI group. In the OW/OB BMI group, cortical plate volume was larger relative to other brain regions after 28 weeks.

Conclusions

This pilot study supports the concept that maternal obesity impacts fetal brain volume, detectable via MRI in living fetuses using quantitative analysis.

Introduction

Maternal obesity [pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2] affects 29 % of pregnancies in the U.S. [1], and increases life-long cardiometabolic [2], 3] and neurodevelopmental health risks in offspring [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Children and young adult offspring of women with obesity have increased risk for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) [4], [5], [6], [7], [8] and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [9], [10], [11], [12] by 47–89 % [4], [5], [6], [7, 13] and 1.5–2 fold [9], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18] respectively. Therefore, maternal obesity is a significant risk-enhancing factor for these neurodevelopmental disorders in addition to genetic, perinatal, and other etiologies [19], 20].

While the underlying pathology of ADHD and ASD is considered to originate in utero, knowledge of how maternal obesity impacts development of these conditions is limited [21]. Animal models of diet-induced obesity show that maternal obesity affects intrauterine brain development such as increased neuroprogenitor proliferation [22], 23], neuroinflammation, oxidative stress [24], 25], altered neuroprogenitor differentiation, maturation [23], 26], gene expression, and DNA methylation patterns [27].

In humans, recent volumetric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analysis revealed that higher pre-pregnancy maternal BMI correlates with a smaller hippocampus in school-age boys (but not in girls) [28]. Diffusion-based MRI analyses of school-aged and adult offspring of pregnancies with high BMI revealed higher fraction anisotropy and lower mean diffusivity in multiple brain tracts such as Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, thalamic radiation, and medial lemniscus, reflecting altered white matter integrity [29]. In newborns of women with obesity, diffusion MRI [30] and functional brain MRI [31] studies revealed lower fraction anisotropy values (poor white matter maturation), and decreased functional connectivity was seen compared to that of lean women. Taken together, these results suggest maternal obesity impacts offspring brain development as early as the neonatal period. However, knowledge on the intrauterine origin of altered fetal brain development is lacking [21] and may guide future interventions. Specifically, a comprehensive qualitative analysis of substructural fetal brain volumes has not been reported.

Quantitative analysis of fetal brain MRI enables precise assessment of fetal brain development in various conditions such as ventriculomegaly [32], [33], [34], [35], congenital heart disease [36], 37], isolated agenesis of corpus callosum [38], Down syndrome [39], 40] or Dandy-Walker malformation [41]. We sought to identify differences in fetal brain structures according to pre-pregnancy or first-trimester BMI, hypothesizing that maternal overweight or obesity influences fetal brain growth. This pilot study measured regional fetal brain volume using regional volumetric analysis of fetal brain MRI in women across a range of pre-pregnancy BMI.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Tufts Medical Center (IRB#10214, approved on 5/10/12). We have complied with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki regarding ethical conduct of research involving human subjects. The study utilized a subset of control subjects from a prospective fetal anomaly cohort study where maternal BMI data was available [38], 41], 42]. We prospectively identified and approached healthy pregnant women with uncomplicated pregnancies who had no fetal abnormalities on ultrasound at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic at Tufts Medical Center from August 2014 to March 2021. In addition, we recruited a healthy pregnant woman whose fetus was initially suspected of brain anomalies (cerebral ventriculomegaly) by their routine obstetric ultrasound studies but subsequently had normal fetal brain MRI scans. We recruited all subjects with written informed consent.

The inclusion criteria were healthy pregnant women aged 15 to 45, singleton pregnancy, the gestational week between 18 and 36, and both fetal sexes. We determined the gestational age of each subject by utilizing sonographic measurement of the embryonic crown-rump length in the first trimester per standard care at obstetric clinics. Exclusion criteria were multiple pregnancies, fetal growth restriction (FGR), abnormal extra-brain fetal sonographic findings, any abnormal fetal MRI findings, or known chromosomal abnormalities. FGR was determined by estimated fetal weight<10th percentile, based on Hadlock formula [43] and the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology guideline [44].

We collected following clinical demographic data from medical records: maternal age, ethnicity, gravidity, maternal complications such as gestational diabetes, hypertension, and infection, fetal sex, presence of fetal abnormalities and FGR as exclusion criteria, birth weight, and gestational age at birth. MRI images were excluded if significant motion or other artifacts were detected. Only one fetal brain MRI for each fetus was included in this study. We identified the subjects’ BMI from their medical records of the first-trimester obstetric visit. We did not directly measure BMI for the study purpose.

Investigators performed MRI acquisition, post-acquisition processing, segmentation, and volumetric analysis blinded to each subject’s BMI. The investigators of neonatologists (ET, SA), and the obstetrician (RK) segmented all images with final curation by pediatric neurologist (TT).

MRI acquisition and post-acquisition processing

We used the following computational pipeline for fetal structural MRI processing as previously described in several of our recent studies [38], 45], 46]. Fetal brains were scanned on a Phillips 1.5 T scanner at Tufts Medical Center. MRI sequence was T2 weighted Half-Fourier Acquisition Single-Shot Turbo Spin Echo (HASTE), field of view=256 mm, time repetition=12.5 s, time echo=180 ms, in-plane resolution=1 mm, and slice thickness=2–3 mm. Multiple (3–12) HASTE scans were acquired at least 3 times in different orthogonal orientations to perform reconstruction process. We combined data from multiple series to reconstruct motion-corrected high-resolution volumes with a voxel size of 0.75 × 0.75 × 0.75 [mm] [47]. These fetal brain MR images were manually aligned along the anterior and posterior commissure (AC-PC) points by using AFNI (afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni) [48]. One radiologist (NM) reviewed MRI studies for unexpected fetal anomalies. One pediatric neurologist with experience in clinical and research fetal brain MRI analysis (TT) reviewed raw MR images and processed MR images quality (motion artifact, reconstruction quality) to assess if the images were feasible for quantitative analysis.

Segmentation and volumetric analysis

We manually segmented regional structures, such as cortical plate, subcortical parenchyma, brainstem, cerebellar hemispheres, vermis, lateral ventricles, third ventricle, and fourth ventricle on coronal planes by using Freeview (Freesurfer®, surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). We also used automatic segmentation methods for some cases (after 30 weeks of gestational age). We manually curated automatically segmented images. Because we could not consistently identify the border of basal ganglia and white matter structures, we determined subcortical parenchyma as the sum of all substructures in cerebrum except for the cortical plate and ventricles. Axial and sagittal planes were used to confirm borders of these structures. After completing the segmentation, we used 3D Slicer 4.11 (slicer.org) to calculate each volume [mm3]. Dice coefficients of segmentation were obtained to confirm the reproducibility of the volumetric analysis. Researchers were blinded to the maternal BMI in all steps of post-acquisition processing and regional volumetric analysis.

Statistical analysis

We divided participants into two groups depending on mothers’ pre-pregnancy or first trimester BMI recorded from their medical records. According to the Center of Disease Control (CDC) [49], BMI less than 25 is normal and BMI greater than or equal to 25 is overweight; thus, the subjects were sorted into the normal maternal pre-pregnancy BMI group or the overweight/obese (OW/OB) maternal pre-pregnancy BMI group. We performed subgroup analyses to compare MRI measures between normal and obese (OB, BMI greater than or equal to 30) maternal pre-pregnancy or first trimester BMI groups.

The volume of regions which we compared between two groups were left/right and whole cortical plate, left/right and whole subcortical parenchyma, left/right lateral ventricle, whole cerebrum (cortical plate + subcortical parenchyma), cerebellar hemispheres, vermis, whole cerebellum, and whole brain (cerebrum + cerebellum + brainstem).

For patient demographics, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables were performed to compare the two groups using Stata. As for the regional volumetric comparisons, group differences in slopes and intercepts were tested with nonlinear regression models using Prism. We also created general linear regression models for each regional volume measure using gestational age and BMI as continuous variables and assessed their significant effects. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Subjects

The study utilized a subset of control subjects from a prospective fetal anomaly cohort study initially aimed to recruit fifteen controls. After completing the original recruitment, we expanded the study and scanned 41 fetuses as controls. Of 41, 20 did not have BMI recorded. Twenty-one fetuses' BMIs were available. One female case was excluded from the analysis because she developed significant developmental delay early in life and was suspected of other underlying neurodevelopmental disorders. One fetus was scanned with ultrasound suspicion of unilateral ventriculomegaly, which resulted in normal fetal brain MRI and postnatal MRIs. Of 20 cases, there were 8 males and 12 females, and the median gestational age at the time of MRI acquisition was 24.3 weeks (range: 19.7–33.3 weeks). The median maternal age at the time of MRI image acquisition was 33.3 years (range: 22.0–37.4 years). No MRI studies were excluded due to unexpected anomalies or poor quality. All subjects had only one MRI per subject.

We divided these 20 cases into two groups: a normal BMI group with a maternal pre-pregnancy/first-trimester BMI under 25 (normal BMI) and an overweight/obese (OW/OB) group with a BMI equal to and over 25. There were 8 fetuses in the normal BMI group and 12 fetuses in the OW/OB BMI group (Table 1). No subjects had a BMI over 40. There were no significant differences in clinical demographics – fetal sex, gestational age, maternal age, or ethnicity between the two groups (Table 1). The medical records of 6 infants in the normal BMI group and 11 infants in the OW/OB group were available to follow up on their perinatal and early developmental outcomes. One pregnant woman in the normal BMI group developed hypertension just before delivery though the MRI scan was completed earlier (22.9 weeks). Another case in OW/OB group had gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 27 weeks, and the MRI scan took place later (30.7 weeks).

Clinical characteristics by BMI group. aSignificance set p-value <0.05.

| Total n=20 | BMI<25 kg/m2 n=8 | BMI>25 kg/m2 n=12 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal BMI median (range) | 26.5 (19.5–35.6) | 20.2 (19.5–23.5) | 30.6 (25.8–35.6) | |

| Gestational age median (range) | 24.3 (19.7–33.3) | 23.0 (19.7–33.3) | 27.4 (20.4–32.6) | 0.877 |

| Maternal age median (range) | 33.3 (22.0–37.4) | 32.1 (23.0–34.9) | 33.8 (22.0–37.4) | 0.396 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.167 | |||

| Male | 8 (40) | 5 (63) | 3 (25) | |

| Female | 12 (60) | 3 (38) | 9 (75) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.310 | |||

| White | 12 (60) | 7 (88) | 5 (41) | |

| Asian | 4 (20) | 1 (12) | 3 (25) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (10) | 0 | 2 (17) | |

| Black or African | 2 (10) | 0 | 2 (17) | |

| American | ||||

| Gravidity | 0.009a | |||

| Nulliiparity, n (%) | 4 (21) (unknown=1) | 4 (57) (unknown=1) | 0 (0) | |

| Birth weight, g median (range) | 3,209 (2,298–3,685) | 3,146.5 (2,755–3,555) | 3,209 (2,298–3,685) | 0.6153 |

| Gestational age at birth, years, median (range) | 38.4 (36.7–40.3) | 38.7 (36.7–40.1) | 38.1 (36.7–40.3) | 0.9196 |

The median birth weight of OW/OB group was 3,209 g (range; 2,298–3,685 g), and that of the normal BMI group was 3,147 g (range; 2,755–3,555 g) (p=0.6153, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test). The range of birth gestational age was 36.7–40.3 weeks in OW/OB group and 36.7–40.1 weeks in the normal BMI group (p=0.9196, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test).

Fetuses in OW/OB group had increased regional volume compared to the ones in the normal BMI group

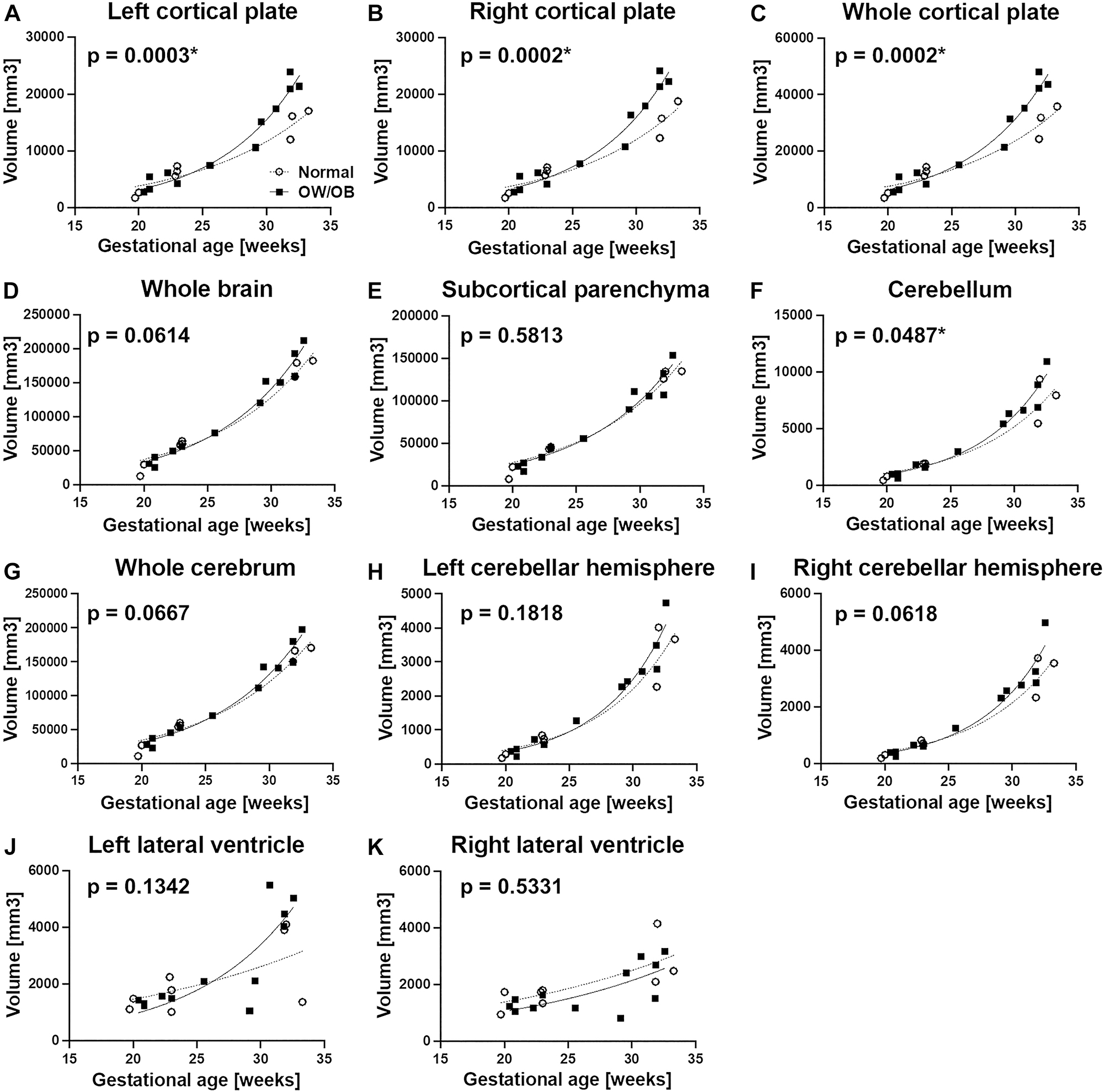

We compared the regional volume between BMI groups for various anatomical regions of interest by plotting the volume measurements according to the gestational age within each group. We found that the fetuses in OW/OB BMI group had significantly accelerated volume patterns in the left cortical plate (p=0.0003) and in the right cortical plate (p=0.0002) in late pregnancy (after 28 weeks) compared to the normal BMI group (Figure 1A and B). OW/OB BMI group also had significantly accelerated volume patterns in the whole (left + right) cortical plate (p=0.0002) and whole cerebellum (p=0.0487) compared to the normal BMI group (Figure 1C–F). There was no significant difference between the two groups in other regions, such as the whole brain (p=0.0614), subcortical parenchyma (p=0.5813), whole cerebrum (p=0.0667), left and right cerebellar hemispheres (p=0.0618, 0.1818), and left and right lateral ventricles (p=0.1342, 0.5331) (Figure 1D and E, G–K). In this method, inter-rater agreements of volumetric measures – Dice coefficients of the left and right cortical plate volume measurements were 0.907 ± 0.027 and 0.906 ± 0.03, respectively.

Comparison of regional brain volume between the normal BMI group (○, n=8) and OW/OB group (■, n=12). The fetuses in OW/OB BMI group had significantly larger left cortical plate and the right cortical plate in late pregnancy (after 28 weeks) compared to the normal BMI group (A and B). OW/OB BMI group also had significantly larger whole (left + right) cortical plate and whole cerebellum compared to the normal BMI group (C–F).

We created general linear models for each regional volume measure using gestational age and BMI as continuous variables. When controlled for gestational age, BMI significantly increased the right cortical plate volumes (p=0.0460) (Supplementary Table 1). Left cortical plate and whole cortical plate volumes did not meet statistically significant effects (p=0.058 and 0.052, respectively), and neither did cerebellar volume (p=0.296). In all models, gestational age had significant effects on fetal brain regional volumes.

Fetuses in OB group had increased regional volume compared to the ones in the normal BMI group

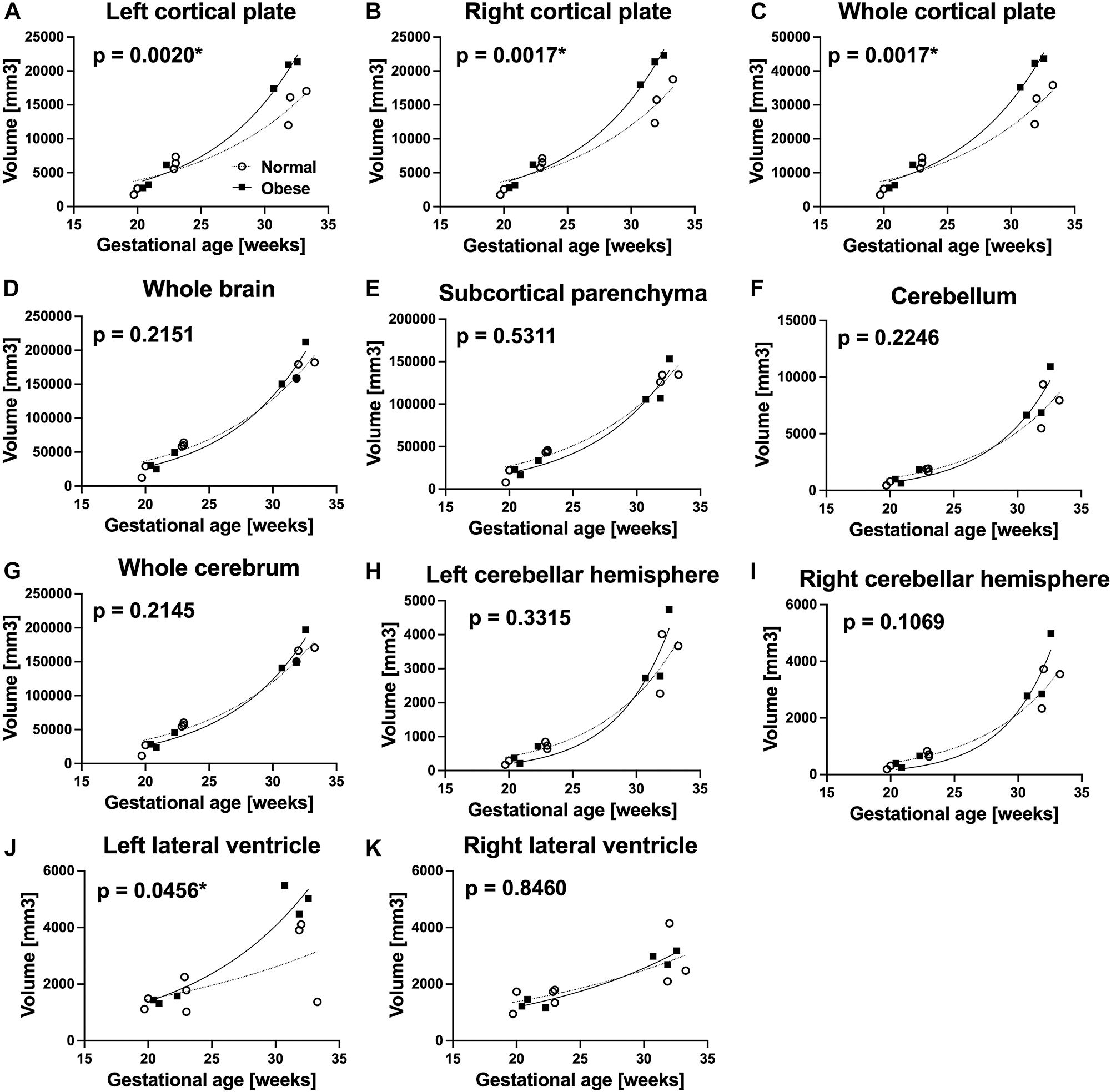

As a subgroup analysis, we analyzed regional volumes of 6 fetuses with maternal obesity (OB group, BMI≥30) in comparison with 8 fetuses with normal maternal BMI (<25). There were no significant differences in clinical demographics between the two groups in terms of fetal sex, maternal gestational age, maternal age, and gravidity (Supplementary Table 1). Similar to the fetuses in OW/OB group, the fetuses in the OB group showed significantly larger volume with left cortical plate (p=0.0020), right cortical plate (p=0.0017), whole cortical plate (p=0.0017) in the late pregnancy (after 28 weeks) (Figure 2A–C). Additionally, the fetuses in the OB group had increased regional volume in the left lateral ventricle (p=0.0456) (Figure 2J). However, one outlier may have influenced this difference, thus cautious interpretation may be needed. There are no significant group differences in the growth of the whole brain, subcortical parenchyma, cerebellum, whole cerebrum, left and right cerebellar hemispheres and right lateral ventricle (Figure 2D and E, F–I, K).

Comparison of regional brain volume between the normal BMI group (○, n=8) and obese group (■, n=6). The fetuses in the OB group showed significantly larger left cortical plate, right cortical plate, and whole cortical plate in the late pregnancy (after 28 weeks) (A–C). Additionally, the fetuses in the OB group had larger left lateral ventricles (J).

As an additional subgroup analysis, we analyzed regional volumes of 6 fetuses with maternal obesity (OB group, BMI≥30) in comparison with 12 fetuses with normal maternal and overweight BMI (<30). There were no significant group differences except left lateral ventricle (p=0.0138) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Timing of increased brain volume

We calculated the ratio of each regional volume to the whole brain and cerebral volumes and plotted it as a function of gestational age. The model reflects each regional volume relative to the whole brain (Supplementary Figure 2). Particularly, we found that in the OW/OB BMI group, cortical plate volume was larger relative to the whole brain and cerebrum after 28 weeks when modeled to polynomial curves (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). In the OW/OB BMI group, the volume of the whole cerebellum was also larger after 25 weeks using linear regression modeling (Supplementary Figure 2d).

Discussion

To assess the impact of high maternal BMI on fetal brain development, we conducted a volumetric analysis of fetal brain MRIs of healthy pregnant women with a range of early first-trimester BMIs. We found that fetuses of Overweight (OW)/Obese (OB) women had a larger cortical plate and cerebellar volumes after 28 weeks compared to the fetuses of normal BMI women. Such differences remained when compared between the OB BMI group and the normal BMI group fetuses. The differences became less significant when we compared fetuses of OB women to fetuses of normal BMI and OW women. Cortical plate volume was specifically increased relative to the overall cerebral volume, as seen in the volume ratio of cortical plate/whole brain as a function of gestational age. Our results may suggest that maternal obesity, as represented by high BMI, alters the regional volume of the fetal brain.

Impacts of maternal obesity on offspring’s brain development

Previous magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) based studies used volumetric MRI analysis, diffusion-based MRI analyses, and resting state functional MRI analysis and found that child and adult offspring of pregnancies complicated with maternal obesity have altered regional volumes (hippocampus) and connectivity (projection and association fibers) [28], [29], [30], [31]. These studies suggest that maternal obesity alters offspring’s brain development in utero, which has long-lasting effects on brain structure even into adulthood. However, studies into fetal brain growth are lacking.

Recent resting-state functional MRI analysis of fetuses of women with a range of BMI showed altered functional connectivity in fetal brain subnetworks (left anterior insula/inferior frontal gyrus and bilateral prefrontal cortex), at 26–39 weeks of gestation [50]. However, this finding was inconsistent among the subjects, perhaps because of technical difficulties associated with fetal functional MRI [50]. Our pilot study identified the impacts of maternal obesity on fetal cortical plate and cerebellar volume growth. It is difficult to compare our result to the volumetric data from school-age children. Our study measured the volume of subcortical parenchyma which includes basal ganglia, white matter, and various structures. Cortical plate would be divided into each cortical region and hippocampal complex. Longitudinal volumetric analysis may provide a continuum of altered brain growth to understand its pathophysiology and stage-specific intervention.

Differences between fetuses of OB and normal BMI women became less significant compared to those of OB and normal BMI/OW women. These results suggest that even maternal overweight could affect fetal brain development. Another explanation might be a small sample size error associated with only six fetuses in the OB group.

General linear regression analyses identified significant effects between BMI and right cortical plate volume. While BMI also appears to affect the left and whole cortical plate volumes, they did not meet statistical significance. This may be due to a small sample size or a smaller effect size of BMI than gestational age. Alternatively, the impacts of BMI may have a threshold effect depending on the degree of maternal obesity. A larger study is needed to answer the above questions.

The question remains if larger cortical plate and cerebellar volumes in fetuses of maternal OW/OB pregnancy are independent of the overall fetal growth. In our cohort, there was no difference in birth weight and birth gestational age between OW/OB and normal BMI groups. However, the gestational age at the time of MRI scans was variable (Table 1). Without knowing each fetal weight at the time of MRI scans, we cannot conclude if, indeed, fetal brain growth differences are independent of overall fetal growth. The next logical step is to reproduce our findings in a larger cohort and determine how such anatomical changes influence child offspring’s neurodevelopment. When conducting a large-scale study in the future, time-coordinated ultrasound studies should be included to assess both overall fetal and brain growth at the same time.

Neurodevelopmental impacts of maternal obesity

Maternal obesity increases offspring’s risk of neuropsychiatric disorders, including ADHD [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], ASD [9], [10], [11], [12], anxiety, and depression [51], 52]. It remains unclear how the greater volume of cortical plate and cerebellum observed in our study affects the future neurodevelopmental functionality of affected fetuses. Greater cortical plate and cerebellar volumes may reflect developmental neurobiological changes such as accelerated neurogenesis or increased production of the intracellular matrix that can be seen in various neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder [53], tuberous sclerosis, or hemimegalencephaly [54]. Toddlers and young children with autism spectrum disorders have abnormally accelerated brain growth up to 6–8 years of age [53]. The brain growth slows at later ages and eventually results in a smaller brain compared to typically developing adults suggesting that brain growth should be assessed and interpreted within a longitudinal context. Similar longitudinal changes may occur in child offspring of mothers with obesity during pregnancy. Smaller hippocampal volume in the school-age children [28] may be the result of evolving developmental changes initiated in the fetal period, and possibly, influenced by postnatal nutritional and environmental factors associated with maternal obesity. Functional connectivity changes observed in newborns of women with obesity [30], 31] may also have such longitudinal evolution into the school age [29]. Epidemiological studies suggested a 1.5 to 2 times increased risk of autism spectrum disorder in child offspring of pregnancies complicated by obesity [9], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Altogether, abnormally accelerated early fetal brain growth in pregnancies complicated by obesity may not be beneficial and require longitudinal growth evaluation and follow-up functional assessment of offspring.

Sex differences in fetal brain volume

Nadel et al. reported that male fetuses had slightly larger cerebral lateral ventricles than female fetuses [55]. Several previous articles reporting differences in the size of the fetal brain by sex showed that male neonates had larger total brain cortical gray and white matter volumes than females [55], [56], [57]. The impact of maternal obesity on offspring brain growth may also have sex-specific effects. As mentioned above, higher pre-pregnancy maternal BMI correlates with a smaller hippocampus in school-age boys but not in girls. Sex-dependent effects of maternal obesity on offspring brain development should be tested in a larger-scale study.

Strengths and limitations

The primary limitation of this study is the exploratory and hypothesis-developing nature due to the small sample size. The study utilized control subjects of a prospective fetal anomaly cohort study. Therefore, the study was not designed to be hypothesis-testing. The preliminary findings identified in this study should be confirmed with a more extensive cohort study. Because of the small sample size, we could not compare sex differences in fetal brain development [28]. We had more females (9 of the 12) in the OW/OB BMI group compared to the lean group (3 of the 8). Due to this imbalance, we may be underestimating the impact of maternal BMI on fetal brain growth.

The study also recruited pregnant women who underwent fetal brain MRI with suspicion of fetal sonographic anomalies such as cerebral ventriculomegaly or abnormal cranial shape. For this study, we used one fetus with sonographic suspicion of unilateral ventriculomegaly that fetal and neonatal brain MRIs were confirmed to be normal. However, it might have caused unrecognized implications that might affect the generalizability to the population. In the future study, we will only recruit healthy pregnant women with uncomplicated pregnancies who have no fetal abnormalities on ultrasound as the subjects.

Our study measured fetal brain regional volumes but not relative to fetal body size due to technical limitations. Though some ultrasound studies were available to estimate fetal weight, the timing between the ultrasound and MRI studies varied significantly, complicating correlation analysis. Ultrasound estimation of fetal weight is not sensitive, and including such data may interfere with more precise brain volume data analysis. Although only one brain MRI scan per fetus was included in the study, it could be more robust to take multiple scans on the same fetus and to longitudinally analyze brain MRI scans over different gestational periods in order to assess actual fetal brain volume growth. Future studies will align with each subject’s ultrasound and fetal MRI assessments to reduce gestational age-associated factors. Comparing all participants within narrower gestational windows and including multiple longitudinal scans are necessary to describe the growth trajectory of each fetus.

Our study analyzed macro-anatomical changes in fetal brain development but did not study histological and molecular changes in the fetal brain, which may drive these anatomical changes. While it is not possible to study living human fetal brain tissue, potential mechanisms associated with altered neurodevelopment have been investigated in animal models [22], 23], 26], 27]. In pregnancies complicated with maternal obesity, metabolic, inflammatory, epigenetic, or microbiomic aberrations impact offspring (reviewed in [58]). Maternal and placental lipid metabolism, altered in maternal obesity, impacts the delivery of fatty acids (e.g. omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids) critical for normal neurodevelopment, which may contribute to the mechanism of aberrant fetal brain development [21], and should be explored in future studies in correlation with fetal MRI analysis. Though clinically relevant, using BMI and the criteria by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) [49] as our only marker of maternal adiposity is a limitation of our study. Also, the low number of participants in this pilot study limited our ability to analyze sex differences. Future studies should include other measures of obesity, such as body fat and maternal metabolism (e.g. resting metabolic rate, gestational weight gain), to comprehensively assess correlations between maternal adiposity, metabolic adaptations to pregnancy, and fetal brain development.

Our study contributes to fundamental knowledge on the impact of high maternal BMI on fetal brain development. We observed increased cortical plate and cerebellar volumes in later pregnancy (28∼ weeks) in the offspring of women with a BMI>25 kg/m2 in early pregnancy. Larger studies will be necessary to determine how this larger fetal brain regional volume impacts neurodevelopmental and behavioral outcomes and whether this change predisposes offspring to the development of ADHD and ASD associated with maternal obesity.

Key points

What’s already known about this topic?

Maternal obesity increases offspring children’s risk of neurodevelopmental impairment. However, little is known about how maternal obesity impacts fetal brain volumetric development.

What does this study add?

Maternal overweight/obesity accelerates fetal cortical plate and cerebellar growth compared to the pregnancy with a normal body mass index (BMI). The growth pattern of the cortical plate was specifically accelerated after 28 weeks of gestation.

Neurodevelopmental impairment in children exposed to maternal obesity in utero may originate from altered fetal brain development.

Funding source: Susan Saltonstall Foundation

Funding source: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Award Identifier / Grant number: Tufts Clinical Translational Science Institute

Funding source: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Award Identifier / Grant number: K23HD079605

Acknowledgments

We are highly appreciative of the participants who volunteered their time to this study. We thank Kenichiro Takeoka for his contribution to the process of imaging analysis.

-

Research ethics: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Tufts Medical Center 58 (IRB#10214, approved on 5/10/12).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. All authors contributed to either conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was supported by funding from NICHD K23HD079605, Tufts Clinical Translational Science Institute, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and Susan Saltonstall Foundation. The fundings supported the collection, method development, analysis and interpretation of the data. The above funding sources have not been involved in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Driscoll, AK, Gregory, ECW. Increases in prepregnancy obesity: United States, 2016-2019. NCHS Data Brief 2020;392:1–8.Search in Google Scholar

2. Gaillard, R, Steegers, EA, Duijts, L, Felix, JF, Hofman, A, Franco, OH, et al.. Childhood cardiometabolic outcomes of maternal obesity during pregnancy: the Generation R Study. Hypertension 2014;63:683–91. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.113.02671.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Alba-Linares, JJ, Perez, RF, Tejedor, JR, Bastante-Rodriguez, D, Ponce, F, Carbonell, NG, et al.. Maternal obesity and gestational diabetes reprogram the methylome of offspring beyond birth by inducing epigenetic signatures in metabolic and developmental pathways. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023;22:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01774-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Rodriguez, A, Miettunen, J, Henriksen, TB, Olsen, J, Obel, C, Taanila, A, et al.. Maternal adiposity prior to pregnancy is associated with ADHD symptoms in offspring: evidence from three prospective pregnancy cohorts. Int J Obes 2008;32:550–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803741.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Chen, Q, Sjolander, A, Langstrom, N, Rodriguez, A, Serlachius, E, D’Onofrio, BM, et al.. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and offspring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study using a sibling-comparison design. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt152.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Andersen, CH, Thomsen, PH, Nohr, EA, Lemcke, S. Maternal body mass index before pregnancy as a risk factor for ADHD and autism in children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr 2018;27:139–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1027-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Kong, L, Norstedt, G, Schalling, M, Gissler, M, Lavebratt, C. The risk of offspring psychiatric disorders in the setting of maternal obesity and diabetes. Pediatrics 2018;142. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0776.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Fuemmeler, BF, Zucker, N, Sheng, Y, Sanchez, CE, Maguire, R, Murphy, SK, et al.. Pre-pregnancy weight and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and executive functioning behaviors in preschool children. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2019;16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040667.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Dodds, L, Fell, DB, Shea, S, Armson, BA, Allen, AC, Bryson, S. The role of prenatal, obstetric and neonatal factors in the development of autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2011;41:891–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1114-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Krakowiak, P, Walker, CK, Bremer, AA, Baker, AS, Ozonoff, S, Hansen, RL, et al.. Maternal metabolic conditions and risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1121–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2583.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Reynolds, LC, Inder, TE, Neil, JJ, Pineda, RG, Rogers, CE. Maternal obesity and increased risk for autism and developmental delay among very preterm infants. J Perinatol 2014;34:688–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2014.80.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Moss, BG, Chugani, DC. Increased risk of very low birth weight, rapid postnatal growth, and autism in underweight and obese mothers. Am J Health Promot 2014;28:181–8. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.120705-quan-325.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Pugh, SJ, Hutcheon, JA, Richardson, GA, Brooks, MM, Himes, KP, Day, NL, et al.. Gestational weight gain, prepregnancy body mass index and offspring attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and behaviour at age 10. BJOG 2016;123:2094–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13909.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Getz, KD, Anderka, MT, Werler, MM, Jick, SS. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and autism spectrum disorder among offspring: a population-based case-control study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2016;30:479–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12306.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Li, M, Fallin, MD, Riley, A, Landa, R, Walker, SO, Silverstein, M, et al.. The association of maternal obesity and diabetes with autism and other developmental disabilities. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20152206. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2206.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Varcin, KJ, Newnham, JP, Whitehouse, AJO. Maternal pre-pregnancy weight and autistic-like traits among offspring in the general population. Autism Res 2019;12:80–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1973.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Windham, GC, Anderson, M, Lyall, K, Daniels, JL, Kral, TVE, Croen, LA, et al.. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain in relation to autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disorders in offspring. Autism Res 2019;12:316–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2057.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Matias, SL, Pearl, M, Lyall, K, Croen, LA, Kral, TVE, Fallin, D, et al.. Maternal prepregnancy weight and gestational weight gain in association with autism and developmental disorders in offspring. Obes (Silver Spring) 2021;29:1554–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23228.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Faraone, SV, Banaschewski, T, Coghill, D, Zheng, Y, Biederman, J, Bellgrove, MA, et al.. The World federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021;128:789–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Bai, D, Yip, BHK, Windham, GC, Sourander, A, Francis, R, Yoffe, R, et al.. Association of genetic and environmental factors with autism in a 5-country cohort. JAMA Psychiatr 2019;76:1035–43. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1411.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Tarui, T, Rasool, A, O’Tierney-Ginn, P. How the placenta-brain lipid axis impacts the nutritional origin of child neurodevelopmental disorders: focus on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Exp Neurol 2021;347:113910.10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113910Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Chang, GQ, Gaysinskaya, V, Karatayev, O, Leibowitz, SF. Maternal high-fat diet and fetal programming: increased proliferation of hypothalamic peptide-producing neurons that increase risk for overeating and obesity. J Neurosci 2008;28:12107–19. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.2642-08.2008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Niculescu, MD, Lupu, DS. High fat diet-induced maternal obesity alters fetal hippocampal development. Int J Dev Neurosci 2009;27:627–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.08.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Bilbo, SD, Tsang, V. Enduring consequences of maternal obesity for brain inflammation and behavior of offspring. Faseb J 2010;24:2104–15. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.09-144014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Edlow, AG. Maternal obesity and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in offspring. Prenat Diagn 2017;37:95–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4932.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Stachowiak, EK, Srinivasan, M, Stachowiak, MK, Patel, MS. Maternal obesity induced by a high fat diet causes altered cellular development in fetal brains suggestive of a predisposition of offspring to neurological disorders in later life. Metab Brain Dis 2013;28:721–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-013-9437-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Grissom, NM, Herdt, CT, Desilets, J, Lidsky-Everson, J, Reyes, TM. Dissociable deficits of executive function caused by gestational adversity are linked to specific transcriptional changes in the prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40:1353–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.313.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Alves, JM, Luo, S, Chow, T, Herting, M, Xiang, AH, Page, KA. Sex differences in the association between prenatal exposure to maternal obesity and hippocampal volume in children. Brain Behav 2020;10:e01522. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1522.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Verdejo-Roman, J, Bjornholm, L, Muetzel, RL, Torres-Espinola, FJ, Lieslehto, J, Jaddoe, V, et al.. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and offspring white matter microstructure: results from three birth cohorts. Int J Obes 2019;43:1995–2006. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0268-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Ou, X, Thakali, KM, Shankar, K, Andres, A, Badger, TM. Maternal adiposity negatively influences infant brain white matter development. Obes (Silver Spring) 2015;23:1047–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21055.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Li, X, Andres, A, Shankar, K, Pivik, RT, Glasier, CM, Ramakrishnaiah, RH, et al.. Differences in brain functional connectivity at resting state in neonates born to healthy obese or normal-weight mothers. Int J Obes 2016;40:1931–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.166.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Grossman, R, Hoffman, C, Mardor, Y, Biegon, A. Quantitative MRI measurements of human fetal brain development in utero. Neuroimage 2006;33:463–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.07.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Scott, JA, Habas, PA, Rajagopalan, V, Kim, K, Barkovich, AJ, Glenn, OA, et al.. Volumetric and surface-based 3D MRI analyses of fetal isolated mild ventriculomegaly: brain morphometry in ventriculomegaly. Brain Struct Funct 2013;218:645–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-012-0418-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Keunen, K, Isgum, I, van Kooij, BJ, Anbeek, P, van Haastert, IC, Koopman-Esseboom, C, et al.. Brain volumes at term-equivalent age in preterm infants: imaging biomarkers for neurodevelopmental outcome through early school age. J Pediatr 2016;172:88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Kyriakopoulou, V, Vatansever, D, Elkommos, S, Dawson, S, McGuinness, A, Allsop, J, et al.. Cortical overgrowth in fetuses with isolated ventriculomegaly. Cerebr Cortex 2014;24:2141–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bht062.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Ortinau, CM, Mangin-Heimos, K, Moen, J, Alexopoulos, D, Inder, TE, Gholipour, A, et al.. Prenatal to postnatal trajectory of brain growth in complex congenital heart disease. Neuroimage Clin 2018;20:913–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.09.029.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Peyvandi, S, Latal, B, Miller, SP, McQuillen, PS. The neonatal brain in critical congenital heart disease: insights and future directions. Neuroimage. 2019;185:776–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.045.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Tarui, T, Madan, N, Farhat, N, Kitano, R, Ceren Tanritanir, A, Graham, G, et al.. Disorganized patterns of sulcal position in fetal brains with agenesis of corpus callosum. Cerebr Cortex 2018;28:3192–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhx191.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Tarui, T, Im, K, Madan, N, Madankumar, R, Skotko, BG, Schwartz, A, et al.. Quantitative MRI analyses of regional brain growth in living fetuses with Down syndrome. Cerebr Cortex 2020;30:382–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhz094.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Yun, HJ, Perez, JDR, Sosa, P, Valdes, JA, Madan, N, Kitano, R, et al.. Regional alterations in cortical sulcal depth in living fetuses with Down syndrome. Cereb Cortex 2021;31:757–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaa255.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Akiyama, S, Madan, N, Graham, G, Samura, O, Kitano, R, Yun, HJ, et al.. Regional brain development in fetuses with Dandy-Walker malformation: a volumetric fetal brain magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS One 2022;17:e0263535. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263535.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Tarui, T, Madan, N, Graham, G, Kitano, R, Akiyama, S, Takeoka, E, et al.. Comprehensive quantitative analyses of fetal magnetic resonance imaging in isolated cerebral ventriculomegaly. Neuroimage Clin 2023;37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2023.103357.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Hadlock, FP, Harrist, RB, Martinez-Poyer, J. In utero analysis of fetal growth: a sonographic weight standard. Radiology 1991;181:129–33. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.181.1.1887021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Lees, CC, Stampalija, T, Baschat, A, da Silva Costa, F, Ferrazzi, E, Figueras, F, et al.. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: diagnosis and management of small-for-gestational-age fetus and fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020;56:298–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.22134.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Im, K, Guimaraes, A, Kim, Y, Cottrill, E, Gagoski, B, Rollins, C, et al.. Quantitative folding pattern analysis of early primary sulci in human fetuses with brain abnormalities. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:1449–55. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.a5217.Search in Google Scholar

46. Ortinau, CM, Rollins, CK, Gholipour, A, Yun, HJ, Marshall, M, Gagoski, B, et al.. Early-emerging sulcal patterns are atypical in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Cerebr Cortex 2019;29:3605–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhy235.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Kuklisova-Murgasova, M, Quaghebeur, G, Rutherford, MA, Hajnal, JV, Schnabel, JA. Reconstruction of fetal brain MRI with intensity matching and complete outlier removal. Med Image Anal 2012;16:1550–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2012.07.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. Cox, RW. AFNI: what a long strange trip it’s been. Neuroimage 2012;62:743–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.056.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. CDC. Weight gain during pregnancy. 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-weight-gain.htm.Search in Google Scholar

50. Norr, ME, Hect, JL, Lenniger, CJ, Van den Heuvel, M, Thomason, ME. An examination of maternal prenatal BMI and human fetal brain development. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 2021;62:458–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13301.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Rodriguez, A. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and risk for inattention and negative emotionality in children. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 2010;51:134–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02133.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Van Lieshout, RJ, Robinson, M, Boyle, MH. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and internalizing and externalizing problems in offspring. Can J Psychiatr 2013;58:151–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371305800305.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Ecker, C, Bookheimer, SY, Murphy, DGM. Neuroimaging in autism spectrum disorder: brain structure and function across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:1121–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(15)00050-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Severino, M, Geraldo, AF, Utz, N, Tortora, D, Pogledic, I, Klonowski, W, et al.. Definitions and classification of malformations of cortical development: practical guidelines. Brain 2020;143:2874–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa174.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Nadel, AS, Benacerraf, BR. Lateral ventricular atrium: larger in male than female fetuses. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1995;51:123–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7292(95)02523-f.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Bromley, B, Frigoletto, FDJr, Harlow, BL, Evans, JK, Benacerraf, BR. Biometric measurements in fetuses of different race and gender. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1993;3:395–402. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.1993.03060395.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Gilmore, JH, Lin, W, Prastawa, MW, Looney, CB, Vetsa, YS, Knickmeyer, RC, et al.. Regional gray matter growth, sexual dimorphism, and cerebral asymmetry in the neonatal brain. J Neurosci 2007;27:1255–60. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3339-06.2007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Tong, L, Kalish, BT. The impact of maternal obesity on childhood neurodevelopment. J Perinatol 2021;41:928–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-00871-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2024-0222).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?