Abstract

In a time of deeply divided political parties, how do Americans think political decisions should be made? In surveys, most Americans say that politicians should be willing to find compromises with the other side. I propose that people endorse compromise because they see it as both a political and a social norm. Conflict is inevitable in politics and in life. People must find ways to navigate the disagreements they have with family, friends, and coworkers – and they expect the same from members of Congress. Using survey evidence from the 2020 American National Social Network Survey, I show that people’s experiences navigating political differences in their social lives sharpens their support for compromise. When people have stronger social ties and more conversations with those who do not share their views, they are more likely to endorse compromise in politics.

Americans are deeply divided by partisanship. Over time, Democrats and Republicans have come to hold increasingly negative views of the opposing party (Abramowitz and Webster 2016; Lelkes 2016). Negative stereotypes of out-partisans abound. Strong partisans perceive members of the opposing party as lazy, less intelligent, and closed-minded (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes 2012; Pew Research Center 2019). While partisanship has always been important to explaining people’s preferences on policy issues, its role in structuring people’s issue preferences has increased over time (Fiorina, Abrams, and Pope 2011; Iyengar et al. 2019; Levendusky 2009). Partisanship is the lens through which politics and government are perceived. While presidential approval was once a barometer of how people felt things were going in the United States, it now seems to be mostly driven by partisanship (Donovan et al. 2020). People like the president when he shares their party affiliation, and dislike presidents from the opposing party. As an example of the depth of this divide, 82% of Democrats said they approved of the job that President Biden was doing in a January 2022 Gallup poll – while only 5% of Republicans offered a positive rating of Biden’s performance as president.

People’s partisan leanings leave their mark outside of politics as well. Partisanship can inform people’s judgments of the physical attractiveness of other people as well as their choice of romantic partners (Huber and Malhotra 2017; Nicholson et al. 2016). Democrats and Republicans see the world on different terms, diverging in their tastes in dining options and their preferences on which cars to drive (Hetherington and Weiler 2018; Wilson 2016). When asked to choose a favorite color, Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to select red.[1]

When we look for partisan differences in the American public, we often find them. Yet in focusing on these partisan fault lines in politics, we often overlook those things that Democrats and Republicans have in common. As one example, consider the public’s ratings of the U.S. Congress. Even though Democrats and Republicans are deeply divided in their views of Joe Biden’s job performance as president, they are more likely to agree than disagree when it comes to their evaluations of Congress. In a January 2022 poll by Gallup, 90% of Republicans said that they disapproved of the job performance of Congress – but 73% of Democrats said the same. While Americans are divided on many things, overwhelming majorities within both political parties share a sense of disappointment with the job performance of Congress.

When asked to explain their frustrations with Congress, most do not mention ideological goals or policy priorities. Instead, they talk about how Congress works – or does not work (Wolak 2020). They mention the problems of gridlock and stalemate. They believe that lawmakers are caught up in partisan squabbles, unwilling to work together to address the problems of everyday Americans (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 2002). They wish that lawmakers would reach across the aisle and work with their opponents. In a 2018 survey, 88% of Americans agreed that “our political leaders are too divided to get anything done—they need to be more willing to compromise.”[2] This is a place of common ground among members of both parties, as 84% of Republicans and 92% of Democrats believe politicians need to be more willing to compromise.

Even as Americans are divided by their partisan loyalties, the need for compromise is a point of shared agreement (Wolak 2020). Members of both parties lament the divisions they see in Congress and wish that politicians would be more willing to work with the other side. In this paper, I demonstrate Americans’ support for political compromise. Within politics, people care about more than just partisanship – they also have preferences about how politics should be practiced. Evidence from a number of surveys confirm that Americans see compromise as a desirable way to resolve political disputes. Support for compromise persists even when partisans are asked if their own party should compromise. While people are more likely to demand concessions from the opposing side than to ask the same of their own party, a majority of partisans nonetheless believe their own party should be willing to compromise.

I argue that people’s desires for compromise find their origins beyond partisan politics, following from political socialization and social considerations. Taking advantage of a survey conducted during the 2020 presidential campaign season, I show that support for compromise is only weakly tied to the intensity of people’s political preferences. Strong partisans are just as supportive of compromise as independents. People’s animosities toward the opposing party, as captured in a measure of affective polarization, are also unrelated to their willingness to support compromise. Only strength of ideology is correlated with openness to compromise, where moderates seem more willing to tolerate the concessions that compromise require. I show that people’s support for compromise is socialized, where those with greater educational attainment are more likely to have internalized support for compromise as a norm. I also show that people’s support for compromise is social. Those who have greater experience navigating political differences in their own lives are more likely to expect politicians to find routes to compromise. People with greater social interactions are more open to compromise, as are those who more frequently have conversations with those who do not share their views.

Party polarization dominates media coverage of the public’s political thinking – but Americans have more shared foundations than these accounts would suggest. In focusing on differences, division, and conflict, we miss the ways in which the public finds consensus. People hold partisan preferences, but they do not demand a political process that guarantees favorable partisan outcomes. In a time of deep partisan divides, it is important to mark out the boundaries of partisan thinking. While people’s support for the democratic norm of political compromise is not immune from partisan thinking, neither is it overwhelmed by it.

1 Points of Agreement Between Democrats and Republicans

Americans contribute to the partisan fervor of the current political environment in their reliance on partisan thinking and their tendency to see the partisan world as “us versus them” (Iyengar et al. 2019; Mason 2018). This rise of partisan thinking can have its virtues, in engaging political interest and motivating action (Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe 2015). But for many, this is not how they ideally want to engage with politics. Many Americans express dismay at the fractured state of partisan politics. Four out of five Americans say they are concerned about the divisions between the two parties, a sentiment shared by 80% of Republicans and 83% of Democrats (Gómez 2020). Seventy-two percent of Americans believe it would be a good thing for Americans to reject political hostility and focus more on their common ground (King and Cox 2021).

While some are drawn in by the ideological battles between the left and the right, others are turned off by these disagreements (Krupnikov and Ryan 2022; Wolak 2022). What appears to be aversion toward the opposing party can actually reflect a negativity toward conflictual politics generally (Klar, Krupnikov, and Ryan 2018). People often say in surveys that they are tired of party divisions and frustrated by direction of politics today (Samuels and Yi 2022). Politics can be a source of personal stress, where one in five Americans say they have lost sleep because of politics (Smith, Hibbing, and Hibbing 2019). Party divides can contribute to negative moods, where perceived party polarization is associated with negative emotions (Levendusky and Malhotra 2016a) as well as heightened anxiety and depression (Nayak et al. 2021).

Even as party loyalty is on the rise, people have mixed feelings about the political parties. People are critical of their partisan adversaries, but many also feel frustrated with their own party. People recognize flaws in their own party as well as the political system generally (Groenendyk 2018). Many do not feel like the political parties represent their views. Most Americans describe both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party as too extreme in their positions (Pew Research Center 2019). They wish that more attention was paid to centrist views. In a 2018 survey, 84% of Americans agreed that “people with extreme views are getting too much attention in public life—we need to have more moderate and reasonable voices.”[3]

People are frustrated with how Congress works. Many Americans would like to see a less divisive and less acrimonious approach to politics. In a 2018 survey, a sample of Americans was asked, “New Year’s Eve is approaching soon. If you could make a New Year’s resolution for Washington, D.C., what would it be?” The most common answer was that members of Congress would stop fighting and work together on bipartisan legislation (Page and Theobald 2018). When people look to Congress, they see lawmakers as too divided, too partisan, and too stubborn to work together. Congress is viewed as an institution that gets very little done because lawmakers would rather argue and debate rather than tackling the problems that average Americans care about (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 2002).

Voters are drawn to the prospect of bipartisan cooperation, where 87% of Americans say attempts at bipartisanship are a good thing (Agiesta 2021). When asked about how they want Congress to work, people wish the parties could work together more effectively. They want politicians to move past their differences and consider compromise (Wolak 2020). Moreover, these preferences for bipartisanship and compromise affect how people evaluate the job performance of their representatives and their approval of Congress. Members of Congress who voice their commitment to bipartisanship increase their support in the electorate (Westwood in press). The public rewards politicians who pledge to reach across the aisle to find compromises (Wolak 2020). When members of Congress choose to hold the party line, they often face penalties at the ballot box (Carson et al. 2010; Koger and Lebo 2017). High levels of party conflict serve to drive down public support for the institution of Congress (Ramirez 2009), and people offer negative views of Congress when it fails to reach compromises on legislation (Wolak 2020).

2 Support for Compromise in Surveys

Compromise offers a way for polarized parties in Congress to make policy progress. To reach a compromise, the parties in dispute do not need to reach a consensus. Instead, compromise asks parties to find those concessions they are willing to make in order to achieve at least some of the outcomes they desire. Across surveys, people are drawn to compromise as desirable way to resolve political disputes. In Table 1, I report six recent survey questions that ask the public how they think about compromise. Each asks about people’s views on compromise in somewhat different ways, but citizens voice consistent support for compromise across the range of measures.

Support for compromise in surveys.

| Chooses compromise option | Rejects compromise | |

|---|---|---|

| aPlease choose the statement that comes closer to your own views--even if neither is exactly right. Compromise in politics is really just selling out on what you believe in. Compromise is how things get done in politics, even though it sometimes means sacrificing your beliefs | 71% | 26% |

| bPlease say if you agree or disagree with the following statements: In politics, willingness to compromise is generally a sign of a weak position | 77% | 22% |

| cIn general, is it more important for politicians to compromise to find solutions, or stick to their principles even if it means nothing gets done? | 74% | 24% |

| dIf you had to choose, would you rather have a member of Congress who compromises to get things done or sticks to their principles, no matter what? | 64% | 36% |

| eWould you rather political leaders in Washington compromise with others and find middle ground on key issues, or stand their ground and fight hard to put in place the ideas they believe in? | 60% | 31% |

| fWhich comes closer to your view? … I want my members of Congress to work across party lines on big issues, even if it means less gets done, I want my members of Congress to get things done, even if it means doing them along partisan lines | 50% | 39% |

-

aPew Research Center. July 8–18, 2021. n = 10221, bSurvey Center on American Life. September 6–8, 2019. n = 1004, cPRRI. September 16–29, 2021. n = 2508, dThe Economist/YouGov. June 26–29, 2021. n = 1500, eFox News. October 16–19, 2021. n = 1003 registered voters, fSuffolk University Political Research Center/USA Today. August 19–23, 2021. n = 1000 registered voters.

The first two items in Table 1 ask people about the principle of compromise, and whether it is something desirable or undesirable in politics. In these items, overwhelming majorities offer positive views of the principle of compromise. In the first item, only 26% of Americans say that compromise is about selling out on what you believe, while 71% agree that compromise is how things get done in politics – even when it means sacrificing your beliefs. Likewise, 77% of Americans reject the statement that a willingness to compromise is the sign of a weak position.

The remaining items in the table ask people what kinds of politicians they prefer: leaders who stand up for what they believe in versus those who are willing to embrace compromise. Each item describes this tradeoff in somewhat different ways. When asked whether it is more important for politicians to compromise to find solutions or stick to their principles even if nothing gets done, 74% say it is more important to find compromises. The next item presents a similar tradeoff but excludes the language suggesting that principled thinking means nothing gets done. Nonetheless, support for compromise remains strong, with 64% of respondents saying they prefer a member of Congress who compromises to get things done and 36% saying they prefer a lawmaker who sticks to their principles no matter what.

The next item frames refusing to compromise favorably, as a commitment to fight for one’s beliefs. Even so, only 31% say they prefer politicians who stand their ground and fight hard to put in place the ideas they believe in. 60 percent still prefer leaders who are willing to find middle ground and compromise. In the last item in Table 1, people are asked if they prefer compromise even if it means less gets done. When compromise is framed in negative terms, half of Americans still say that they prefer to see members of Congress work together across party lines. Thirty-nine percent of Americans choose the alternative, preferring members of Congress who focus on getting things done even if it means voting along partisan lines. People’s support for compromise is sensitive to how the question wording is framed. Americans are more enthusiastic about compromise described as an alternative to gridlock than when it described as something that can slow down progress. But across these different survey questions, we see that a majority of Americans select the compromise option in every instance. Most people think compromise is a good thing in politics. Most people prefer politicians who are willing to work with the other side to find compromises.

How can we reconcile this high level of public enthusiasm for political compromise against what we know about the depth of partisan thinking in the electorate? Some assume that these statements of support for compromise are insincere in some way. Editorial writers pen essays with titles like “You Want Compromise? Sure You Do” (Stolberg 2011) and “People Want Congress to Compromise. Except That They Really Don’t” (Cillizza and Sullivan 2013). Maybe people say they like compromise in the abstract even as they dislike it in specific circumstances. Maybe people only think the other side should make compromises, even as they are unwilling to tolerate any concessions from their own party.

To address this, I turn to survey questions that ask people about the importance of compromise for their own political party versus the need for the other side to be willing to compromise. If people really put partisanship ahead of all other considerations, then we should expect to see deep differences in the demand for compromise along partisan lines. Democrats should expect Republicans to compromise, while calling on members of their own party to stand firm to their convictions. Republicans should demand loyalty to the party line from co-partisans, even as they expect Democrats to be willing to make concessions.

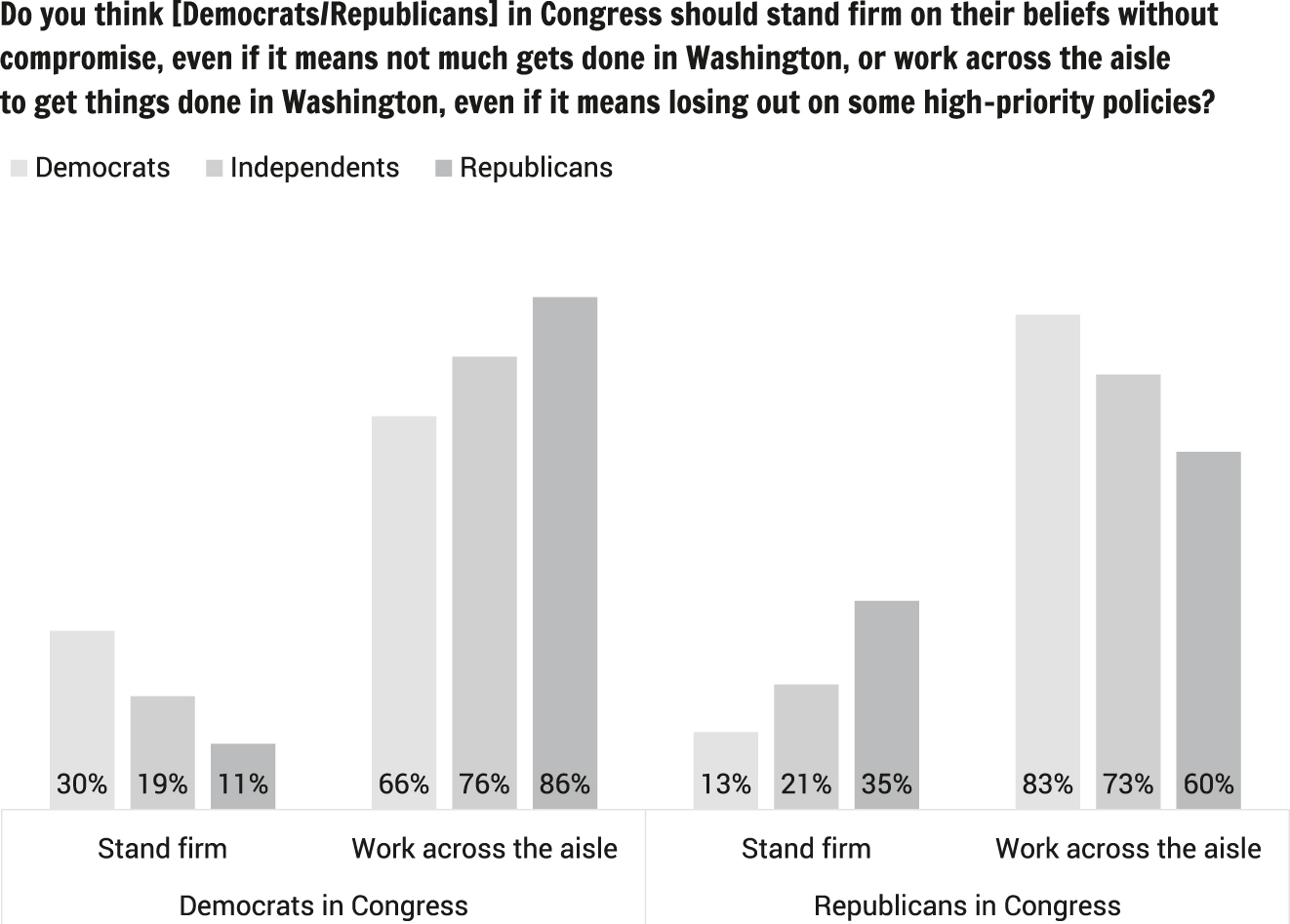

To explore this, I rely on a survey conducted by CNN in April 2021. In the survey, Americans were asked whether they believe that Democrats and Republicans in Congress should stand firm on their beliefs without compromise or work across the aisle even if it means losing out on some high-priority policies.[4] As was true in the other question wordings, most people believe that they parties should be willing to compromise. Less than one in four Americans said they felt that the parties should refuse to compromise. Twenty-one percent said the Democratic Party should stand firm on their beliefs, while 22% said that Republicans in Congress should avoid making compromises. When respondents are subdivided by their party identification in Figure 1, we see that partisanship leaves an imprint. People hold different views of what their own party should do compared to what they expect of the other party. Among Democrats, 83% say that Republicans should be willing to compromise, while only 66% say that Democrats in Congress should reach across the aisle. A similar pattern is found among Republicans, where 86% say that the lawmakers from the opposing party should be willing to compromise and 60% say that Republicans in Congress should be willing to compromise.

Partisan demands for compromise by democrats and republicans.

In this, people’s demands for compromise are not immune from partisanship. People hold their own party and the opposing party to different standards. But at the same time, the survey also reveals that even among partisans, most believe that their own party should be willing to compromise. Only a small share of partisans opposes compromise from their own party, where 30% of Democrats and 35% of Republicans say that members of their own party should stand firm in their convictions. Resistance to compromise is a minority view – even when people are asked about their willingness to see their own party in Congress make compromises.

3 The Basis of Public Support of Compromise

Why are Americans so supportive of political compromise? I argue that people care about more than just partisanship in politics – they also hold preferences about how politics should be practiced. These preferences find their origins outside of partisan politics. People have policy goals, but they also have beliefs about how government should work. These beliefs are rooted in political socialization. In school and in civic life, people learn about how democracy works. Classes in history, government, and social studies provide lessons on not just the Constitution and the design of government, but also the norms that govern political spaces. There are norms around good citizenship, where citizens have the responsibility to engage with politics and participate in elections. There are norms of civility about how to treat those who disagree with you. There are also norms about how political disputes should be resolved. Compromise is one such norm of democratic life (Wolak 2020).

Through their socialization, Americans come to see compromise as a virtuous and desirable way to settle political conflicts. People endorse compromise in part because they believe that they should – they have internalized it as a norm for how politics should be practiced. In school, students are taught about the compromises that were needed to craft a constitution that would be able to gain support across all the states. Separation of powers and checks and balances across the branches of government are presented as a strength of American democracy, where politicians must find ways to negotiate their differences with their opponents. Outside of formal civics lessons in school, people also learn about the merits of compromise in social situations. Young children are encouraged to settle disputes with words, not fists. Parents and teachers encourage children to work out disputes with friends or siblings by finding compromise solutions. In adulthood, many situations ask people to find cooperative solutions over competitive ones. Compromises are often a necessary part of maintaining the peace with partners or family members.

After all, conflict is not unique to politics. People have squabbles with their partners, disagreements with their coworkers, and different values than their close friends and family. Sometimes, people can just avoid the conflicts – unfriending an acquaintance on social media or sitting at the other end of the dinner table at Thanksgiving. But in other cases, people find that their social ties are more important than their political differences. In these spaces, people must find ways to move forward even as they disagree. Whether it is a collaboration with co-workers, planning a fundraiser with the parent–teacher association, or planning a weekend trip with friends, we cannot win every disagreement. Sometimes we win, sometimes we lose, and sometimes we are able to find a compromise that gives both sides some of what they hoped for.

Unlike members of Congress, members of the public are often unable to enjoy the luxury of living in a perpetual state of unresolved conflict with those who disagree. In the conflicts people experience in their personal lives, compromise can be an appealing path forward. In making a compromise, we respect that other people value different things. We accept something less than our ideal outcome in favor of a resolution that allows us to move past this disagreement. In this way, I argue that the origins of support for compromise are as much social as they are political. Just as people must find ways to navigate disagreements in their own lives, they believe that elected officials should find ways to get along with their co-workers.

To demonstrate this, I explore the social foundations of people’s endorsement of compromise in politics. I consider first the value of face-to-face interactions for increasing people’s openness to compromise. People spend time with others because they find it personally rewarding. But for Putnam (2000), this kind of socializing can also be a civic virtue. Our informal social connections – whether in socializing with our neighbors or inviting friends over for dinner – can strengthen the social ties between individuals. These social relationships give us practice at finding shared ground among people with different backgrounds, experiences, and beliefs. These social ties can grow social capital. When people feel connected to others, it can promote interpersonal trust and feelings of reciprocity. These feelings in turn facilitate communication and cooperation, setting the stage for finding workable compromises.

Our social encounters can also reinforce social norms around working with others. Whether spending time with friends or with those in a community group, our interactions with others follow a number of social norms. These include things like letting others speak without interruption, being polite, and respecting the fact that others see the world differently. The time we spend with others can serve to reinforce the importance of these social norms. In homeowners’ association meetings, church groups, and book clubs, people are reminded that not everyone shares their views. In order to maintain these social ties and not disrupt these relationships, people try to find ways to navigate these differences and work collaboratively with others to solve problems. This too can contribute to people’s willingness to support compromise as a social norm.

I also consider how the composition of people’s social networks affects their willingness to compromise. People vary in the degree to which their lives ask them to navigate political differences. When we look at people’s core social discussion networks, most people spend more time talking to those who share their views than those who disagree (Butters and Hare in press; Mutz 2006). At the same time, people do not live in entirely homogenous discussion networks. Most people have at least one close friend who does not support the same presidential candidate as they do (Dunn 2020). I expect that people’s experiences dealing with political differences in their social lives sharpens their support for compromise.

The conversations people have with those who disagree with them are thought to be one way to disrupt people’s tendencies toward partisan thinking. In-person conversations with out-party members can suppress partisan motivated reasoning and reduce the negative views people have toward the opposing party (Klar 2014; Levendusky and Stecula 2021; Wojcieszak and Warner 2020). I propose two main ways that people’s social ties to those with competing views may encourage an openness to compromise. First, talking with others has the potential to correct misperceptions about the other side. We know that people tend to think about members of the political parties in stereotypical ways (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes 2012). These stereotypical impressions are often wrong. People misperceive and exaggerate the differences between themselves and members of the opposing party (Ahler and Sood 2018; Levendusky and Malhotra 2016b). They also overestimate the degree to which members of the opposing party judge them negatively for their political beliefs (Lees and Cikara 2020).

People’s understandings of the political parties reflect the stories they see in the news, and these media accounts emphasize how Democrats and Republicans differ, not what they have in common. As a result, people perceive a more polarized public than reality bears out (Fernbach and Van Boven 2022). People’s misperceptions of how they think about the opposing party are consequential for how they understand politics (Enders and Armaly 2019). Disrupting these inaccurate stereotypes with accurate information about the opposing party can correct misperceptions and lead people to feel closer to members of the out-party (Ahler and Sood 2018). It is easier to vilify the opposing side when we see them as caricatures of extreme partisans rather than as real people. But interacting with friends, family, and acquaintances who hold opposing views has the potential to interrupt people’s tendencies to see the opposing party in abstract “us versus them” terms. If we see the opposing party as less extreme and less socially distant, it may be easier to imagine that compromise is possible.

A second way that diverse discussion may encourage compromise is in helping people appreciate the common ground that may exist between themselves and the other side. People learn about politics when they engage in conversations with others (Amsalem and Nir 2021; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1995). When they discuss politics with those who do not share their views, they come to better understand the reasons why they come to hold those views (Mutz 2002). Discussions that take place across party lines can help people appreciate the perspectives of those who do not share their views (Levendusky and Stecula 2021). This understanding of the other side can lessen partisan animosities and promote tolerance for those who do not share the same political beliefs (Levendusky and Stecula 2021; Mutz 2002). By better understanding where others are coming from, it can be easier to envision working together to find compromises.

4 Data and Measures

To explore the political and social roots of support for compromise, I draw on responses to the American National Social Network Survey. This survey was conducted by the Survey Center on American Life with a nationally-representative sample of 4067 American adults interviewed ahead of the 2020 presidential election.[5] Respondents were asked, “Thinking about politics and our political system … on the issues you care most about, do you think it is possible to compromise and find common ground with people who disagree with you or would you say this is not possible?” Most Americans agree that compromise is possible on the issues they care about most. 80% agreed that common ground can be found with people who do not share your views, while only one out of five said they felt it was not possible.

To explain why some are more likely to believe in the possibility of compromise than others, I consider three types of explanations: partisan beliefs, political socialization, and social considerations. I start with partisan motives, given the common assumption that partisans are reluctant to accept any outcome other than a win for their political party. Compromises may be seen as undesirable to strong partisans on multiple fronts. By their nature, compromises will involve settling for something less than the ideal outcome. Compromises ask for collaboration with deeply-disliked opponents. A compromise means ceding ground to the other side, allowing opponents to achieve some of their objectives. Compromises also are more likely to deliver moderate outcomes than ideologically extreme ones. As such, we have reason to believe that those with strong prior political beliefs will be reluctant to support compromise in politics. To test this, I first consider the effects of party loyalty, to see whether people with strong partisan attachments are pessimistic about compromise. I also consider the effects of ideological strength, to see whether strong ideologues are less supportive of compromise than moderates. Strength of partisanship and strength of ideology are measured as folded versions of seven-point scales of partisan and ideological self-identification.

It may be that the greatest opposition to compromise is not tied to people’s partisan and ideological commitments, but instead the hostilities they feel toward those in the opposing party. If people dislike their opponents and mistrust their motives, it will be difficult to agree to work together to find successful compromises. I test this with a measure of affective polarization that asks respondents how upset they would feel if they had a son or daughter who married someone who holds the opposite opinion on Donald Trump.[6] This is a common measure in prior studies of affective polarization that captures the social animus people feel toward those who disagree with them (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes 2012; Klar, Krupnikov, and Ryan 2018).

I next consider the effects of political socialization. I have argued that people see compromise as a norm of democracy. If this is true, then support for compromise should follow from the same factors that reinforce public support for democratic principles. The best available option to measure this in the survey is a marker of educational attainment. Past studies confirm that increasing education is associated with greater support for democratic values (Nie, Junn, and Stehlik-Berry 1996; Prothro and Grigg 1960). I expect that greater education will also predict greater support for compromise.

Finally, I consider whether people’s experiences in navigating differences in their social network are associated with greater willingness to support compromise. I start with a measure of informal social connections. Respondents were asked when they were last invited over to someone’s home to have dinner or socialize.[7] Patterns of informal socializing are a marker of social capital for Putnam (2000), where socializing strengthens social ties and reinforces social norms that govern getting along with other people. I expect that those who are more socially engaged will be more likely to support compromise, while those who are more socially isolated will be less enthusiastic about the prospect of compromise.

I also consider how people interact with their social discussion network, drawing on a social network battery included in the survey. Respondents were asked about those people with whom they regularly discuss important matters. The items capture patterns of talk within people’s core discussion networks. These core discussion networks usually include partners and spouses, family members, and close friends, reflecting strong, established social ties that typically persist over time (Mutz 2006). While it is possible that political motives can influence the composition of our core political networks, these social ties typically exist prior to elections and persist after they end. Core networks are usually stable over time, defined by our social relationships and shared pursuits rather than political considerations (Minozzi et al. 2020; Sokhey, Baker, and Djupe 2015).

Respondents are first asked to name up to seven individuals with whom they have discussed important personal matters or concerns.[8] The names people share are piped into a series of follow-up questions that ask people how often they talk to this person as well as whether this person favors Donald Trump or Joe Biden in the upcoming 2020 presidential election.[9] From these items, I construct three measures to describe how people engage in talk within their core discussion networks. The first is a count of the number of discussion partners that the respondent names. I expect that people with wider social discussion networks will be more likely to support compromise than those who name few discussants.

The second measure reflects the frequency of discussion with any discussion partners who share the same presidential candidate preference, as a share of total frequency of discussion among all named discussants. This measure allows me to assess whether conversations with like-minded discussants undermine people’s support for compromise. In past studies, patterns of discussion in homogenous networks are thought to lead to greater polarization (Druckman, Levendusky, and McLain 2018; Schkade, Sunstein, and Hastie 2010). If people spend most of their time with people who are like-minded, they may underestimate the degree to which other Americans do not share their political outlook. If they believe that most share their views, they will see less reason to consider compromises. The third measure complements this item, reflecting the share of overall discussion takes place with those who have opposing candidate preferences. Discussion with those with unknown candidate preferences serves as the baseline category. I expect that greater discussion with those who hold opposing views should increase support for compromise.

Finally, I include an indicator of people’s mindsets toward political conflict with those who disagree with them. Respondents were asked, “In your experience, when you talk about politics with people who you disagree with, do you generally find it to be interesting and informative or stressful and frustrating?” Those who answer “interesting and informative” are coded 1, indicating that they are tolerant of disagreement. Those who say “stressful and frustrating” are coded 0, indicating that they are intolerant of political disagreement. I expect those that have a negative reaction to political disagreement will be less willing to consider compromise. I also include several control variables, including age, gender, and identifying as Black, Latino, or Asian-American.

5 Explaining Attitudes about Compromise

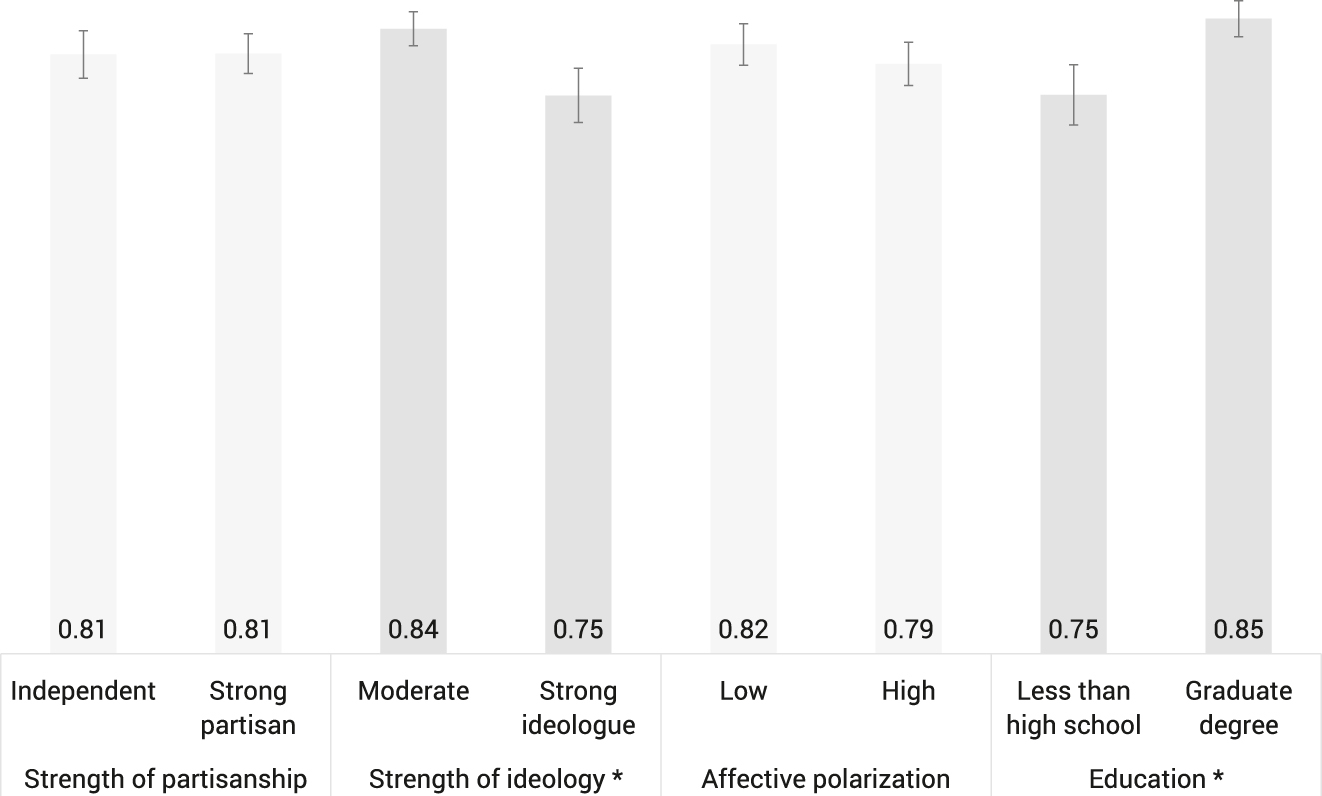

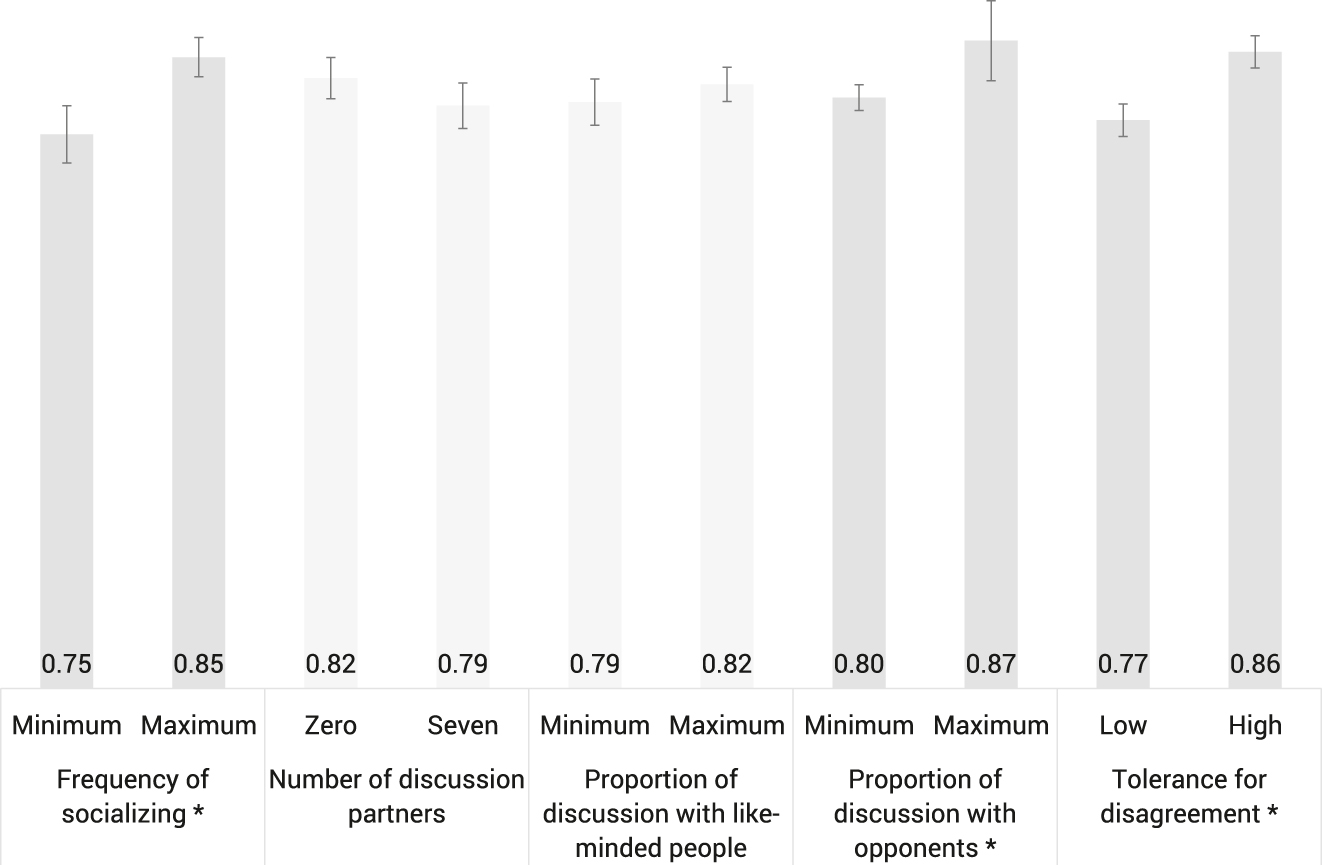

In Table 2, I present logit results. In Figures 2 and 3, I show the predicted probability of supporting compromise at the minimum and maximum levels of each of the substantive predictors. Significant differences are shown with darker gray bars, insignificant effects are in light gray. Starting first with the set of partisan explanations, I find only partial support for the argument that the intensity of people’s partisan and ideological commitments undercuts their optimism about the prospects of compromise. As shown in Figure 2, strong partisans and independents are not significantly different in their endorsement of compromise. Nor do I find a significant effect associated with affective polarization. People who say they would be very upset if their son or daughter married someone with the opposite opinion of Donald Trump are not any more negative about compromise than those who say this would not make them upset at all. Knowing the degree to which people are hostile toward those with opposing political views fails to explain attitudes toward compromise. The only political factor that predicts opposition to compromise is strength of ideology. As shown in Figure 2, moderates have a predicted level of support for compromise of 0.84, which is significantly greater than is seen among those who self-identify as strong liberals or strong conservatives (0.75).

Political and social correlates of support for compromise.

| Support for compromise | |

|---|---|

| Strength of partisanship | 0.002 |

| (0.057) | |

| Strength of ideology | −0.193a |

| (0.054) | |

| Affective polarization | −0.174 |

| (0.163) | |

| Education | 0.682a |

| (0.192) | |

| Informal socializing | 0.688a |

| (0.193) | |

| Number of discussion partners named | −0.036 |

| (0.025) | |

| Proportion of discussion with like-minded discussants | 0.159 |

| (0.150) | |

| Proportion of discussion with those with opposing preferences | 0.590a |

| (0.279) | |

| Tolerance for disagreement | 0.635a |

| (0.115) | |

| Female | 0.015 |

| (0.105) | |

| Black | −0.092 |

| (0.174) | |

| Latino | −0.293a |

| (0.139) | |

| Asian-American | 0.318 |

| (0.308) | |

| Age | 0.000 |

| (0.003) | |

| Constant | 0.832a |

| (0.235) | |

| N | 3890 |

-

American National Social Network Survey. Logit estimates. Standard errors in parentheses. a p < 0.05.

Predicted support for compromise by partisan priors.

Predicted support for compromise at the minimum and maximum of each predictor. Significant relationships in dark gray, insignificant differences in light gray.

Predicted support for compromise by social ties.

Predicted support for compromise at the minimum and maximum of each predictor. Significant relationships in dark gray, insignificant differences in light gray.

Considering the effects of political socialization, I find that higher levels of education are associated with greater support for political compromise. Those who have less than a high school degree have a predicted level of support for compromise of 0.75, which rises to 0.85 among those with a graduate degree. This is consistent with past work that argues that the origins of support for compromise are found in political socialization (Wolak 2020).

Turning to the social origins of support for compromise, I find that higher levels of informal socializing are associated with more positive views of compromise. Someone who says that they have never been invited to someone else’s home for dinner or to socialize have a predicted level of support for compromise of 0.75. This rises to 0.85 for someone who has received an invitation to socialize in the past day. People with stronger social connections are more optimistic about the prospect of compromise. The social exchanges people have in their informal social interactions contribute to the belief that it is possible to collaborate in politics to find compromises. However, I fail to find evidence that the size of one’s social discussion network affects support for compromise. Those who name no discussants are just as likely to endorse compromise as those who name seven people as part of their core discussion network.

When considering the effects of diverse versus reinforcing patterns of discussion, greater discussion with like-minded discussants does not undercut support for compromise. Those who frequently talk with those who share their political views are just as willing to compromise as those who have low rates of discussion with those who share their political preferences. Scholars have raised concerns that homogenous discussion networks can fuel partisan animosities (Druckman, Levendusky, and McLain 2018; Parsons 2015). Even so, talking with like-minded others does not undermine people’s willingness to consider compromise with the other side.

I find that support for compromise climbs with the frequency of people’s discussions with those who hold opposing views. Moving from the lowest level of discussion with those with opposing candidate preferences to the highest is associated with an increase in support for compromise from 0.80 to 0.87. Those who have more experience navigating political differences with their close friends and family are more open-minded about the prospects of finding compromises. Diverse discussions have the potential to reduce people’s negativity toward the opposing party (Levendusky and Stecula 2021; Wojcieszak and Warner 2020). I find that these interactions are also associated with greater open-mindedness about finding workable compromises with political opponents.

Finally, I find that people’s mindset toward political disagreement is also predictive of their willingness to endorse compromise. Those who say that talking with people who disagree with them is interesting and informative have a predicted likelihood of compromise of 0.86, which drops to 0.77 for those who describe discussion with those who disagree as stressful and frustrating. Those who are more tolerant of political disagreement are more optimistic about the prospect of successfully negotiating political compromises.

6 Conclusions

In surveys, Americans regularly say that they want to see politicians work together to find common ground and forge compromises. Most people believe that compromise is a desirable way to approach the conflicts created by the deep partisan divides in Congress. Even in a time of heightened social polarization in the electorate, Americans arguably care about things other than partisanship alone. They also care about how politics is practiced. They believe it is important for Democrats and Republicans to move forward to achieve policy goals – even if it means not achieving all of the party’s objectives. People’s demands for compromise are not entirely free from partisan thinking – people are more likely to expect that the opposing party should compromise than to demand the same from their own party. Even so, a majority of party identifiers still believe that their own party should be willing to compromise. Americans are much more open to the prospects of compromise than we might expect given the partisan animosities people report in surveys.

The origins of public support for compromise are political as well as social. Political forces can pull people away from compromise, where strong ideologues are less keen on compromise compared to moderates. These effects are bounded, however, as neither strength of partisanship nor affective polarization predict opposition to compromise. People are drawn to compromise by social factors, where experiences in navigating political differences can encourage an openness to compromise. Those who report more frequent informal social interactions are more supportive of compromise, as are those who spend a greater share of time discussing politics with those who do not share their political views. Interpersonal discussion with members of the opposing party has been argued to weaken partisan animosities (Klar 2014; Levendusky and Stecula 2021; Wojcieszak and Warner 2020). I find here that it also is associated with greater enthusiasm for finding compromise. Partisans may want to see their political party succeed in advancing its policy goals, but at the same time they recognize that other people want different things in politics. These social ties may help people recognize the importance of working with those who disagree to find compromise.

Party polarization in politics today is thought to originate among elites, but is reinforced by the public in their affective polarization and animosities toward the out-party. As such, it can be tempting to assign blame to the public for the gridlock we see in Washington. Perhaps members of Congress are just doing as their constituents wish in holding the party line and resisting calls to compromise. Yet the evidence here suggests that public demand for partisan intransigence is much lower than we might expect. Strong majorities of Americans would like to see more compromise in politics. Elected officials have greater incentives to compromise than is often acknowledged in discussions of party polarization in America.

In focusing on the ways partisans disagree, we underestimate how much shared ground exists among average Americans. These findings serve as a useful reminder that there are bounds to the partisan thinking of the electorate. Partisanship is absolutely important to how Americans understand politics. But it is not the only thing that voters care about. They often put policy progress ahead of partisan goals (Costa 2021). They care about democratic norms and the process of political decision-making (Broockman, Kalla, and Westwood in press; Lelkes and Westwood 2017; Wolak 2020). Because they care about both policy outcomes and the process of political decision-making, they are willing to make compromises even when these compromises come at the cost of partisan goals.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., and S. Webster. 2016. “The Rise of Negative Partisanship and the Nationalization of U.S. Elections in the 21st Century.” Electoral Studies 41: 12–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.11.001.Search in Google Scholar

Agiesta, J. 2021. CNN Poll: Americans Want Bipartisanship, But Most Don’t Think it Will Happen. CNN. www.cnn.com/2021/04/29/politics/cnn-poll-bipartisanship/index.html (accessed April 29, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Ahler, D. J., and G. Sood. 2018. “The Parties in Our Heads: Misperceptions about Party Composition and Their Consequences.” The Journal of Politics 80 (3): 964–81, https://doi.org/10.1086/697253.Search in Google Scholar

Amsalem, E., and L. Nir. 2021. “Does Interpersonal Discussion Increase Political Knowledge? A Meta-Analysis.” Communication Research 48 (5): 619–41, https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219866357.Search in Google Scholar

Broockman, D. E., J. L. Kalla, and S. J. Westwood. In press. “Does Affective Polarization Undermine Democratic Norms or Accountability? Maybe Not.” American Journal of Political Science, https://dx.doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9btsq.10.31219/osf.io/9btsqSearch in Google Scholar

Butters, R., and C. Hare. In press. “Polarized Networks? New Evidence on American Voters’ Political Discussion Networks.” Political Behavior, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09647-w.Search in Google Scholar

Carson, J. L., G. Gregory Koger, J. M. J. MatthewLebo, and Y. Everett. 2010. “The Electoral Costs of Party Loyalty in Congress.” American Journal of Political Science 54: 598–616, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00449.x.Search in Google Scholar

Cillizza, C., and S. Sullivan. 2013. “People want Congress to Compromise. Except that They Really Don’t.” In The Washington Post. www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2013/06/13/people-want-congress-to-compromise-except-that-they-really-dont/ (accessed June 13, 2013).Search in Google Scholar

Costa, M. 2021. “Ideology, Not Affect: What Americans want from Political Representation.” American Journal of Political Science 65: 342–58, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12571.Search in Google Scholar

Donovan, K., P. M. Kellstedt, E. M. Key, and M. J. Lebo. 2020. “Motivated Reasoning, Public Opinion, and Presidential Approval.” Political Behavior 42: 1201–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09539-8.Search in Google Scholar

Druckman, J. N., M. S. Levendusky, and M. L. Audrey. 2018. “No Need to Watch: How the Effects of Partisan Media can Spread via Interpersonal Discussions.” American Journal of Political Science 62 (1): 99–112, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12325.Search in Google Scholar

Dunn, A. 2020. Few Trump or Biden Supporters have Close Friends who Back the Opposing Candidate: Pew Research Center. www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/18/few-trump-or-biden-supporters-have-close-friends-who-back-the-opposing-candidate/ (accessed September 18, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Enders, A. M., and M. T. Armaly. 2019. “The Differential Effects of Actual and Perceived Polarization.” Political Behavior 41 (3): 815–39, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9476-2.Search in Google Scholar

Fernbach, P. M., and L. Van Boven. 2022. “False Polarization: Cognitive Mechanisms and Potential Solutions.” Current Opinion in Psychology 43: 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.06.005.Search in Google Scholar

Fiorina, M. P., S. J. Abrams, and J. C. Pope. 2011. Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America, 3rd ed. New York: Pearson.Search in Google Scholar

Gómez, V. 2020. Democrats More Optimistic than Republicans that Partisan Relations in Washington will Improve in 2021. Pew Research Center. www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/12/01/democrats-more-optimistic-than-republicans-that-partisan-relations-in-washington-will-improve-in-2021/ (accessed December 1, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Groenendyk, E. 2018. “Competing Motives in a Polarized Electorate: Political Responsiveness, Identity Defensiveness, and the Rise of Partisan Antipathy.” Political Psychology 39: 159–71, https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12481.Search in Google Scholar

Hetherington, M., and J. Weiler. 2018. Prius or Pickup? How the Answers to Four Simple Questions Explain America’s Great Divide. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.Search in Google Scholar

Hibbing, J. R., and E. Theiss-Morse. 2002. Stealth Democracy: Americans’ Beliefs about How Government Should Work. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511613722Search in Google Scholar

Huber, G. A., and N. Malhotra. 2017. “Political Homophily in Social Relationships: Evidence from Online Dating Behavior.” The Journal of Politics 79: 1269–283, https://doi.org/10.1086/687533.Search in Google Scholar

Huckfeldt, R., and J. Sprague. 1995. Citizens, Politics, and Social Communication: Information and Influence in an Election Campaign. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511664113Search in Google Scholar

Huddy, L., L. Mason, and L. Aarøe. 2015. “Expressive Partisanship: Campaign Involvement, Political Emotion, and Partisan Identity.” American Political Science Review 109 (1): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055414000604.Search in Google Scholar

Iyengar, S., Y. Lelkes, M. Levendusky, N. Malhotra, and S. J. Westwood. 2019. “The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 22: 129–46, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034.Search in Google Scholar

Iyengar, S., G. Sood, and Y. Lelkes. 2012. “Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (3): 405–31, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038.Search in Google Scholar

King, L., and C. Cox. 2021. “Poll: Americans Agree with Rejecting ‘Political Hostility,’ But Think Divisions will Rise.” In USA Today. www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2021/12/09/poll-finds-most-americans-pessimistic-political-rancor-ease/8860329002/ (accessed December 9, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Klar, S. 2014. “Partisanship in a Social Setting.” American Journal of Political Science 58: 687–704, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12087.Search in Google Scholar

Klar, S., Y. Krupnikov, and J. B. Ryan. 2018. “Affective Polarization or Partisan Disdain? Untangling a Dislike for the Opposing Party from a Dislike of Partisanship.” Public Opinion Quarterly 82 (2): 379–90, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfy014.Search in Google Scholar

Klofstad, C. A., S. D. McClurg, and R. Meredith. 2009. “Measurement of Political Discussion Networks: A Comparison of Two ‘Name Generator’ Procedures.” Public Opinion Quarterly 73 (3): 462–83, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfp032.Search in Google Scholar

Krupnikov, Y., and J. B. Ryan. 2022. The Other Divide: Polarization and Disengagement in American Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Koger, G., and M. J. Lebo. 2017. Strategic Party Government: Why Winning Trumps Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226424743.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Lees, J., and M. Cikara. 2020. “Inaccurate Group Meta-Perceptions Drive Negative Out-Group Attributions in Competitive Contexts.” Nature Human Behaviour 4: 279–86, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0766-4.Search in Google Scholar

Lelkes, Y. 2016. “Mass Polarization: Manifestations and Measurements.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80: 392–410, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw005.Search in Google Scholar

Lelkes, Y., and S. J. Westwood. 2017. “The Limits of Partisan Prejudice.” The Journal of Politics 79: 485–501, https://doi.org/10.1086/688223.Search in Google Scholar

Levendusky, M. S. 2009. The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226473673.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Levendusky, M., and N. Malhotra. 2016a. “Does Media Coverage of Partisan Polarization Affect Political Attitudes?” Political Communication 33: 283–301, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1038455.Search in Google Scholar

Levendusky, M. S., and N. Malhotra. 2016b. “(Mis)Perceptions of Partisan Polarization in the American Public.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80: 378–91, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfv045.Search in Google Scholar

Levendusky, M. S., and D. A. Stecula. 2021. We Need to Talk: How Cross-Party Dialogue Reduces Affective Polarization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009042192Search in Google Scholar

Mason, L. 2018. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226524689.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Minozzi, W., H. Song, D. M. J. Lazer, M. A. Neblo, and K. Ognyanova. 2020. “The Incidental Pundit: Who Talks Politics with Whom, and Why?” American Journal of Political Science 64: 135–51, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12469.Search in Google Scholar

Mutz, D. C. 2002. “Cross-Cutting Social Networks: Testing Democratic Theory in Practice.” American Political Science Review 96 (1): 111–26, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055402004264.Search in Google Scholar

Mutz, D. C. 2006. Hearing the Other Side: Deliberative Versus Participatory Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511617201Search in Google Scholar

Nayak, S., T. Fraser, C. Panagopoulos, D. P. Aldrich, and D. Kim. 2021. “Is Divisive Politics Making Americans Sick? Associations of Perceived Partisan Polarization with Physical and Mental Health Outcomes among Adults in the United States.” Social Science & Medicine 284: 1–7.10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113976Search in Google Scholar

Nicholson, S. P., C. M. Coe, J. Emory, and A. V. Song. 2016. “The Politics of Beauty: The Effects of Partisan Bias on Physical Attractiveness.” Political Behavior 38 (4): 883–98, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9339-7.Search in Google Scholar

Nie, N. H., J. Junn, and K. Stehlik-Barry. 1996. Education and Democratic Citizenship in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Page, S., and B. Theobald. 2018. “USA TODAY/Suffolk Poll: What Do Democrats want in 2020? Someone New – and Biden. But Definitely Not Hillary.” In USA Today. www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/12/26/2020-democrats-usa-today-suffolk-university-poll/2399076002/ (accessed December 26, 2018).Search in Google Scholar

Parsons, B. M. 2015. “The Social Identity Politics of Peer Networks.” American Politics Research 43 (4): 680–707, https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673x14546856.Search in Google Scholar

Pew Research Center 2019. Partisan Antipathy: More Intense, More Personal. Also available at www.people-press.org/2019/10/10/partisan-antipathy-more-intense-more-personal.Search in Google Scholar

Prothro, J. W., and C. M. Grigg. 1960. “Fundamental Principles of Democracy: Bases of Agreement and Disagreement.” The Journal of Politics 22: 276–94, https://doi.org/10.2307/2127359.Search in Google Scholar

Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.10.1145/358916.361990Search in Google Scholar

Ramirez, M. D. 2009. “The Dynamics of Partisan Conflict on Congressional Approval.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (3): 681–94, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00394.x.Search in Google Scholar

Samuels, A., and J. Yi. 2022. Americans Feel Burnt Out. FiveThirtyEight. fivethirtyeight.com/features/americans-feel-burnt-out-personally-and-politically/ (accessed January 21, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Schkade, D., C. R. Sunstein, and Hastie Reid. 2010. “When Deliberation Produces Extremism.” Critical Review 22: 227–52, https://doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2010.508634.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, K. B., M. V. Hibbing, and J. R. Hibbing. 2019. “Friends, Relatives, Sanity, and Health: The Costs of Politics.” PLoS One 14 (9): 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221870.Search in Google Scholar

Sokhey, A. E., A. Baker, and P. A. Djupe. 2015. “The Dynamics of Socially Supplied Information: Examining Discussion Network Stability over Time.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 27 (2): 565–87, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edv028.Search in Google Scholar

Stolberg, S. G. 2011. “You Want Compromise? Sure You Do.” In The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2011/08/14/sunday-review/you-want-compromise-sure-you-do.html (accessed August 12, 2011).Search in Google Scholar

Westwood, S. J. In press. “The Partisanship of Bipartisanship: How Representatives Use Bipartisan Assertions to Cultivate Support.” Political Behavior, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09659-6.Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, C. 2016. “Do You Eat like a Republican or a Democrat?” In Time. time.com/4400706/republican-democrat-foods/ (accessed July 18, 2016).Search in Google Scholar

Wojcieszak, M., and B. R. Warner. 2020. “Can Interparty Contact Reduce Affective Polarization? A Systematic Test of Different Forms of Intergroup Contact.” Political Communication 37 (6): 789–811, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1760406.Search in Google Scholar

Wolak, J. 2020. Compromise in an Age of Party Polarization. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780197510490.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Wolak, J. 2022. “Conflict Avoidance and Gender Gaps in Political Engagement.” Political Behavior 44: 133–156, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09614-5.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Jennifer Wolak, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Introduction: Volume 20 Issue 1: Public Opinion in America

- Articles

- Explanations for Inequality and Partisan Polarization in the U.S., 1980–2020

- Collective Narcissism and Perceptions of the (Il)legitimacy of the 2020 US Election

- Two Sides of the Same Coin? Race, Racial Resentment, and Public Opinion Toward Financial Compensation of College Athletes

- Public Perceptions of the Supreme Court: How Policy Disagreement Affects Legitimacy

- Do Elite Appeals to Negative Partisanship Stimulate Citizen Engagement?

- Who Are Leaners? How True Independents Differ from the Weakest Partisans and Why It Matters

- Nationalism in the ‘Nation of Immigrants’: Race, Ethnicity, and National Attachment

- The Social Foundations of Public Support for Political Compromise

- Books Reviews

- Meghan Condon, and Amber Wichowsky: The Economic Other: Inequality in the American Political Imagination

- Daniel W. Drezner: The Toddler-in-Chief: What Donald J. Trump Teaches Us About the Modern Presidency

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Introduction: Volume 20 Issue 1: Public Opinion in America

- Articles

- Explanations for Inequality and Partisan Polarization in the U.S., 1980–2020

- Collective Narcissism and Perceptions of the (Il)legitimacy of the 2020 US Election

- Two Sides of the Same Coin? Race, Racial Resentment, and Public Opinion Toward Financial Compensation of College Athletes

- Public Perceptions of the Supreme Court: How Policy Disagreement Affects Legitimacy

- Do Elite Appeals to Negative Partisanship Stimulate Citizen Engagement?

- Who Are Leaners? How True Independents Differ from the Weakest Partisans and Why It Matters

- Nationalism in the ‘Nation of Immigrants’: Race, Ethnicity, and National Attachment

- The Social Foundations of Public Support for Political Compromise

- Books Reviews

- Meghan Condon, and Amber Wichowsky: The Economic Other: Inequality in the American Political Imagination

- Daniel W. Drezner: The Toddler-in-Chief: What Donald J. Trump Teaches Us About the Modern Presidency