Abstract

The educational content of physical chemistry can be a burden for students who are classified as sensing learners (SL). Therefore, for SL, the lecturer must adapt the educational material reflected in standardizing certain procedures (for example, performing and proving similar expressions–differential changes of thermodynamic potentials) and visualization of abstract concepts and expressions. Here is presented the connection of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in isentropic conditions with useful work (in the system, there is one exothermic reaction in the quasi-static regime) and with the differential change of internal energy in an adiabatic and isochoric composite system (reactive system + corresponding reservoir) as well as with the differential change of internal energy in the isochoric composite system. When defining an isentropic process (or system), the change in entropy that is a consequence of heat exchange and the change in entropy that is a consequence of a chemical reaction is considered. Differential changes in thermodynamic potentials are also shown schematically, facilitating SL’s mastery of the material.

1 Introduction

There are several divisions in terms of learning style; one division is sensing learners (SL) and intuitive learnings (IL). 1 , 2 It is believed that SL students prefer observation, collection of data, like to learn facts, and participate in experiments. SL students prefer standard and well-established methods in solving problems. During their studies, IL students apply indirect perception, prefer principles, innovation, new theories, and dislike similar and repetitive tasks. IL students accept symbols more easily than SL students. 1 Lectures on physical chemistry and thermodynamics are full of symbols (mathematical equations) which favors IL students. However, psychological and statistical analyses show that most chemical engineering students belong to the SL group. 3 , 4 Therefore, it is desirable to adapt lectures to SL students. Although the material is full of mathematical formulas, proving (i.e., deriving) equations can be simplified by standardizing mathematical derivation (suitable for SL). Research in the psychology of learning indicates that using visual aids, such as pictures, is effective in helping students understand abstract concepts. 5 Consequently, during lectures in physical chemistry, we focus on illustrating the processes represented by specific equations. The standard approach to learning involves visualizing the processes described by these equations.

The goal is to relate the differential changes in thermodynamic potentials (internal energy, enthalpy, Helmholtz free energy, and Gibbs compact energy) related to a system where one reaction occurs (reactive system), considering different conditions in the reactive system. The desire is for students to have a visual representation of differential changes in thermodynamic potentials and to show that if the goal is to obtain useful work (isentropic conditions) – the portion of a chemical reaction’s energy changes that can be converted into work usable for practical purposes, such as electrical work or other forms of energy transfer–then differential changes in thermodynamic potentials are reduced to differential changes in the internal energy of a composite system (a system in which the reaction takes place + the corresponding reservoir) that is adiabatic and isochoric or to a composite system that is only isochoric. An identical approach is used for each thermodynamic potential, standardizing the proof, which is convenient for SL students. The material presented in the discussion is suitable for students who have previously completed the definitions of thermodynamic potentials and partial molar quantities.

2 Discussion

2.1 Differential change in internal energy

Consider a closed reactive system in which only one reaction takes place to obtain useful work (analogously, the supply of energy to perform some reaction can be observed).

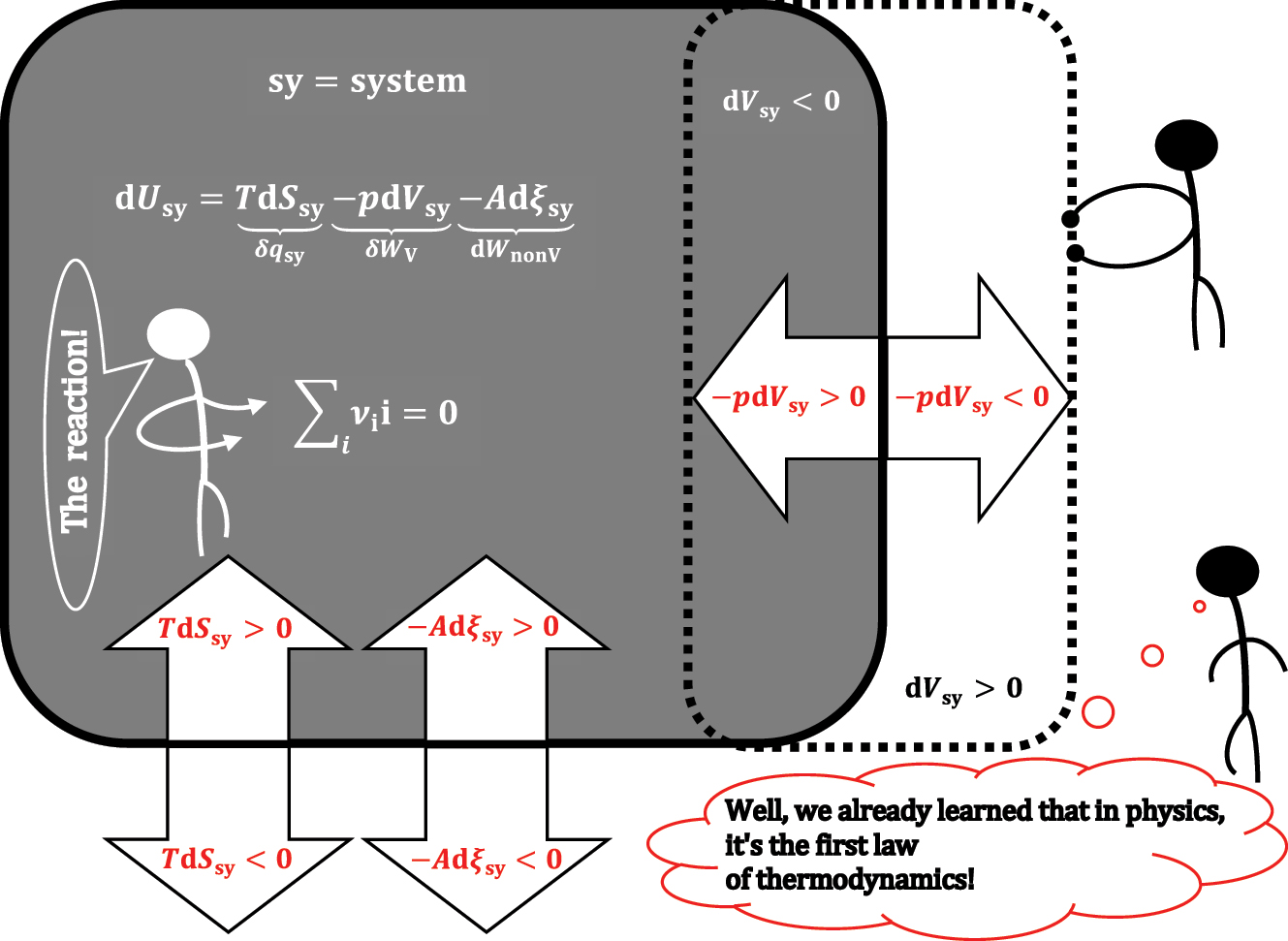

In general, the differential change in the internal energy of a closed system (sy) – which only exchanges energy with the environment (Figure 1) – can be the result of an infinitesimal change in entropy (dS

sy), which is related to the quasi-static transfer of heat between sy and the environment (δq

sy = TdS

sy); an infinitesimal change in the volume of the system (dV

sy) – i.e., the quasi-static differential pressure-volume work exchanged between sy and the environment (δW

V

= -pdV

sy); and the infinitesimal change in the amount of the i-th reactive component (

In equation (1), T, p, and μ are intensive quantities from the system sy and are, respectively, temperature, pressure, and chemical potential–which is defined for each component from the system. In sy, the change in the amount (mol) of reactive components that belong to the same reaction can be expressed in one extensive quantity (ξ sy) – the degree of progress of the chemical reaction–extent of the chemical reaction. 9 , 10 The extensive quantity ξ sy as an intensive quantity corresponds to De Donder’s affinity of a chemical reaction (Appendix A). 11 , 12

ν i denotes the stoichiometric coefficients of the reactive components in the observed reaction (∑reaction ν ii = 0) from sy. Equation (1) is the total differential of internal energy in the system sy; therefore, it can be expressed with partial differentials of internal energy:

A closed system sy in which a chemical reaction takes place: the differential change in the internal energy of the system.

Equations (1) and (3) obtain the definitions of intensive quantities using partial derivatives of internal energy:

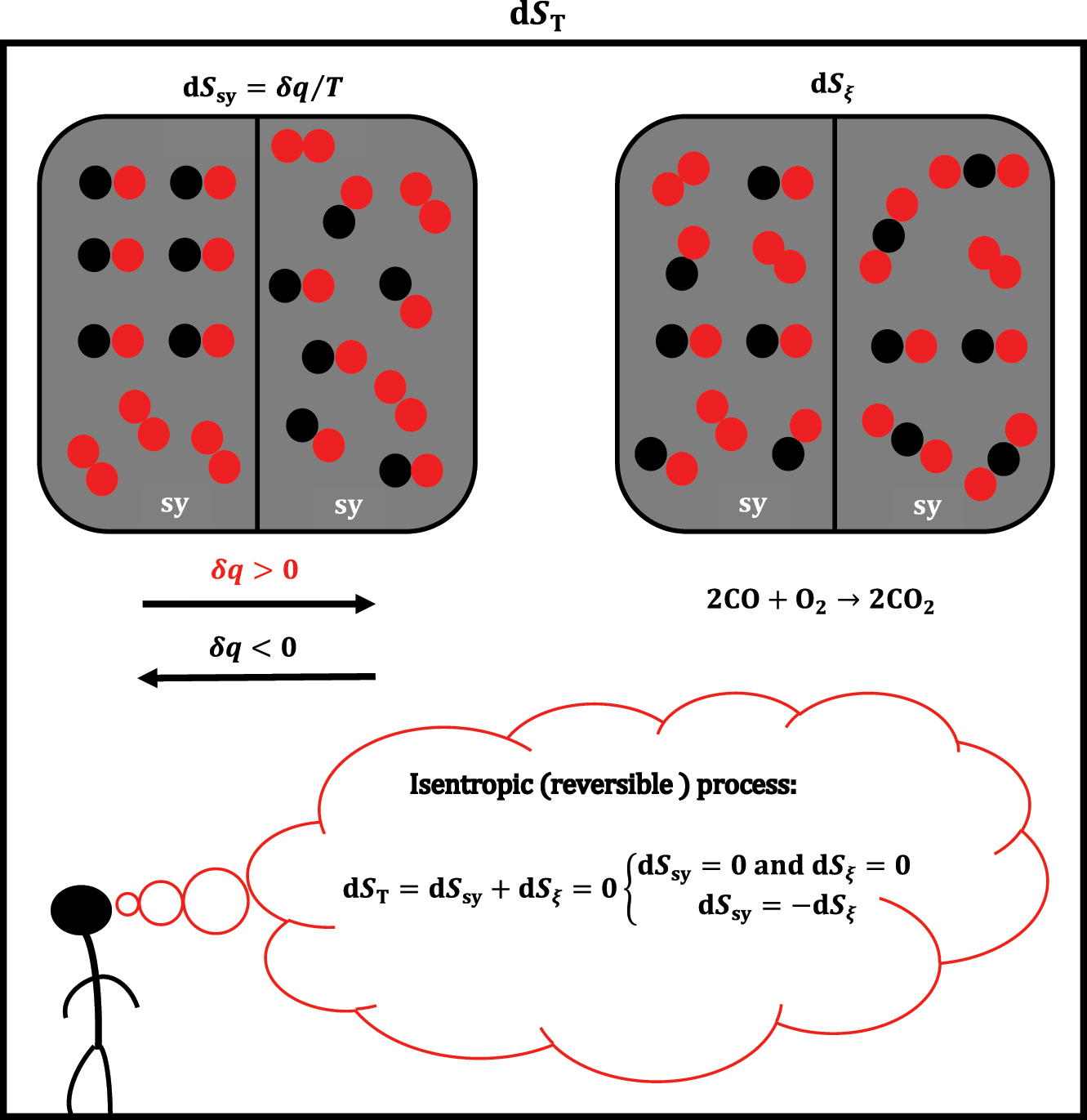

According to equation (1), the quasi-static exchange of infinitesimal heat between system sy and the environment (δq sy) results in a differential entropy change in sy (dS sy):

However, there is also a differential change in entropy that is not covered by equations (1) and (3), which is a differential change in entropy due to the infinitesimal progression of the chemical reaction from the system (dS ξ ). So, the total differential change of entropy in sy is (Figure 2):

The change in entropy of a system of constant volume is a consequence of the heat exchange between the system (sy) and the environment or the occurrence of a chemical reaction in the system or both processes simultaneously.

Suppose in sy, i.e., in equations (1) and (3), entropy S sy (entropy related to heat exchange) and volume V sy are constant (S sy,V sy = const.). In that case, i.e., the system is rigid (isochoric) and adiabatic (the system does not exchange heat with the environment: dS sy = 0→TdS sy = δq sy = 0), the differential change of internal energy in system sy is:

Let reaction ∑

i

ν

ii = 0 from sy occur quasi-statically and isentropically (approximations for a reversible thermodynamic process),

7

,

8

,

13

,

14

which implies that the differential change of the total entropy in the system is zero (dS

T = 0). However, as the reaction proceeds in an adiabatic system (dS

sy = 0), it follows that under isentropic conditions–according to equation (5) – the equality dS

ξ

= 0 must also apply (Figure 2). In other words, if equality

5

holds, in sy without heat exchange with the environment under the isentropic conditions, the reaction ∑

i

ν

ii = 0 does not change the system’s entropy. Under isentropic conditions in the case of

that can be obtained from system sy (Figure 3).

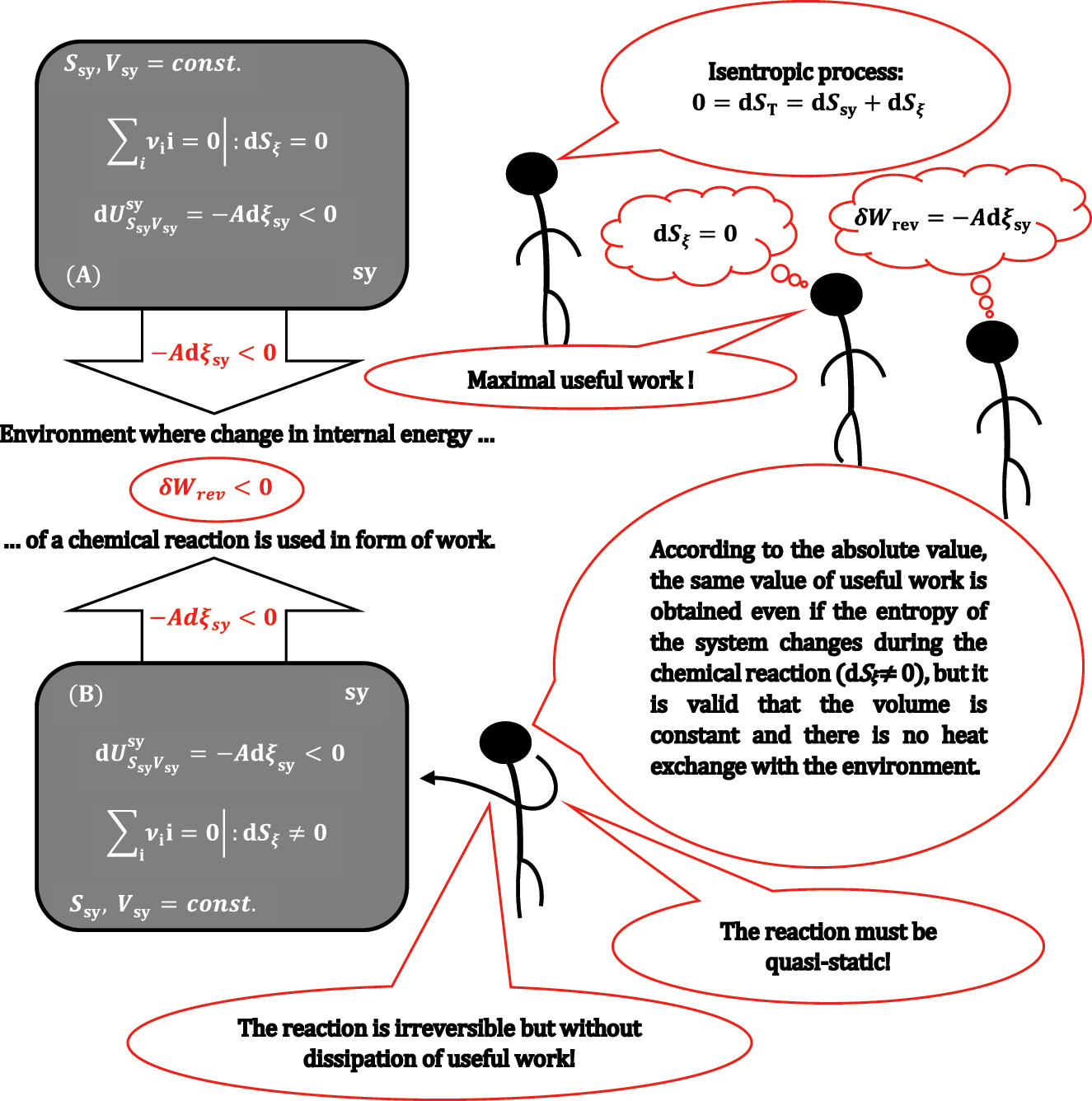

A closed rigid and adiabatic system sy in which a chemical reaction takes place under isentropic conditions (A) and under non-isentropic conditions (B).

During the lecture, usually, a student, after the introduction of equations (6) and (7), asks the following question: what if there is a change in entropy (dS ξ ≠0) during the quasi-static reaction ∑ i ν ii = 0 in a rigid adiabatic (dS sy = 0) system? Answer follows from equation (5):

Suppose equation (6) is valid, and there is a chemical reaction–a thermodynamic process–in a system with dS

ξ

≠0. In that case, the thermodynamic process in system sy cannot be isentropic or reversible (in a reversible process, the total entropy does not change). Namely, there is no possibility for dS

ξ

compensation due to heat transfer between the system and the environment. However, it should be emphasized to the students that even under conditions dS

ξ

≠0, if the observed reaction from sy is in the quasi-static regime, then equation (6) is still valid, and the same amount of work is obtained as when dS

ξ

= 0, i.e., in the quasi-static regime, energy dissipation into heat is negligible. However, due to equality,

8

the reaction generally belongs to an irreversible thermodynamic process in the quasi-static regime. Students from earlier lectures know that if a thermodynamic process is non-isentropic (irreversible), then a smaller amount of useful work is obtained than when the same process is isentropic (reversible), for example, during isothermal irreversible expansion of a system, the environment receives a smaller amount of work in absolute value than during reversible isothermal expansion. This means that if system sy in which the reaction

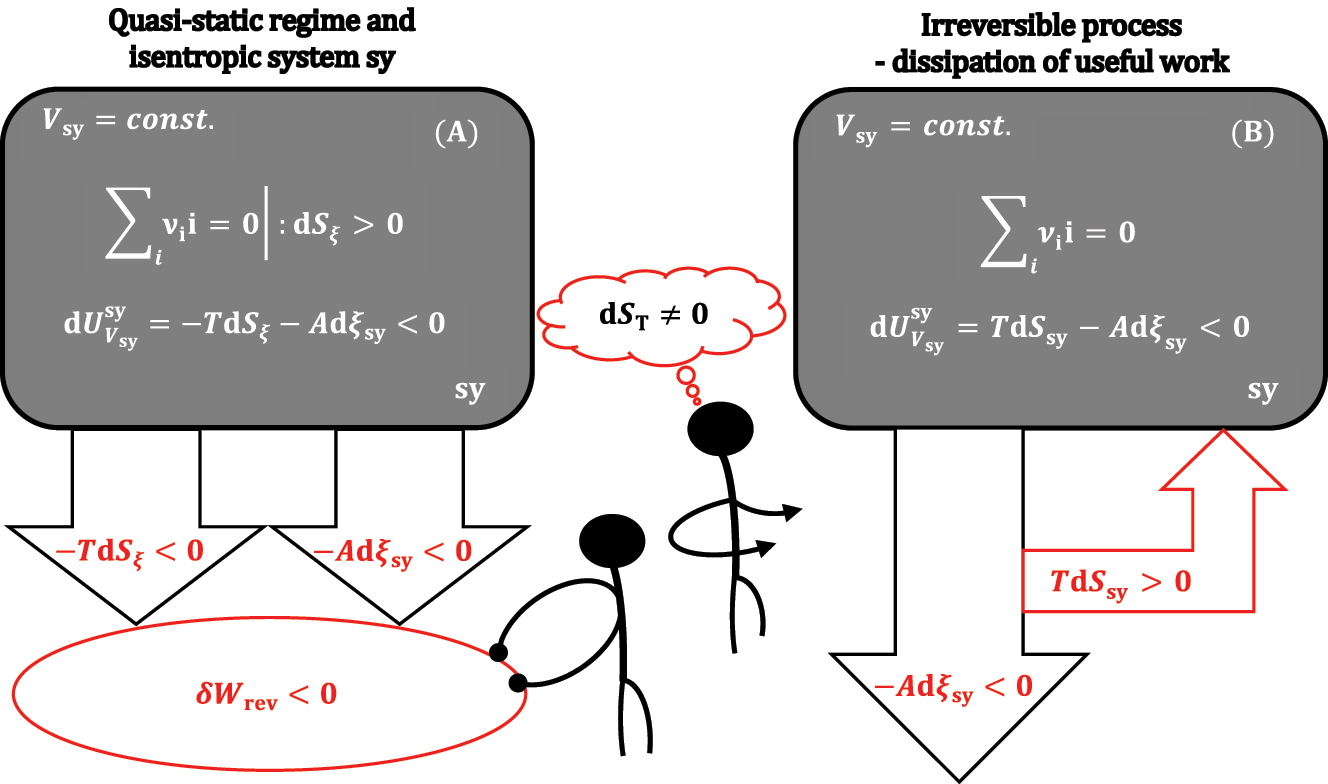

Of course, under isentropic conditions in sy, dS sy = -dS ξ applies, so the total differential 9 is:

It follows from equation (10) that if it is dS ξ >0, then under isentropic conditions, the inequality holds:

According to the inequality 11 in the case of an isentropic thermodynamic process (chemical reaction) from sy, under the conditions V sy = const., a greater amount of useful work is obtained by the absolute value for the quantity |-TdS ξ |, i.e., for the amount of quasi-static heat required for dS ξ >0 compensation, than under adiabatic-isochoric (S sy,V sy = const.) conditions (Figure 4).

An isochoric system that is isentropic (A) or not isentropic (B).

If the thermodynamic process at V sy = const. conditions in sy is not isentropic and quasi-static (reversible), then TdS sy formally represents the thermal energy supplied to sy and represents the energy loss of the useful work -Adξ sy (for example, if the useful work from the chemical reaction is used to drive the piston and if friction occurs when the piston moves, then part of |-Adξ sy| is lost as frictional thermal energy |TdS sy|, i.e., -Adξ sy<0 and TdS sy>0 are valid, Figure 4).

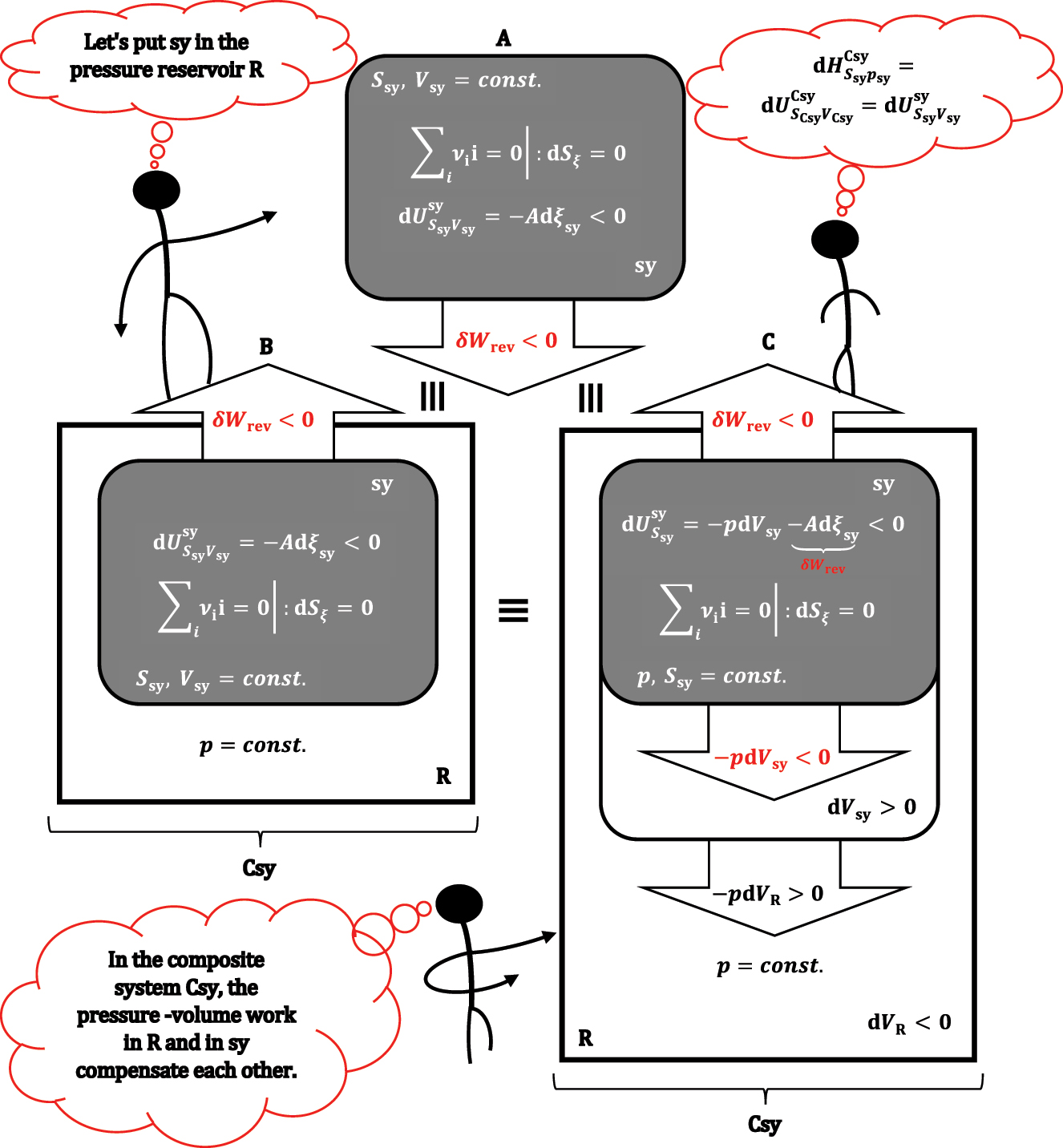

2.2 Differential change of enthalpy

In general, from the function of internal energy (U = f(S,V,ξ)≡U(S,V,ξ)), enthalpy (H) is defined by a partial Legendre transformation 7 , 14 , 15 , 16 – in the state function U, the independent variable (extensive quantity) V is replaced by the intensive quantity pressure p (whose values are easily monitored by manometer):

Differentiation of equation (12) leads to the following expression:

If equation (13) refers to the system sy from Figure 1 (dH = dU sy + pdV sy + Vdp sy), then by introducing the total differential of internal energy 1 we get:

However, with equation (14), usually a student guesses: professor, you left out the subscript “sy” for the symbol H. Then the professor says: let us wait a while longer; let the subscript be a mystery:

In equation (14), the term TdS

sy comes from equation (1) and, therefore, represents the exchanged heat between isochoric sy and the environment:

Based on equation (15), it can be noted that during the heating of isochoric sy, the total supplied thermal energy is spent on increasing the internal energy of the system, while when heating isobaric sy, a part of the heat is spent on pressure-volume work (

From the above equation (

If the pressure in sy is constant and if sy does not exchange heat with the environment (sy is adiabatic), then equation (14) is:

However, as -Adξ sy derives from the expression for the total differential of internal energy 1 , then the following applies:

In order to understand equation (18) in more detail, it is necessary to return to the differential change in enthalpy from equation (13a) under adiabatic conditions and constant pressure of the system:

If in expression, 19 the two terms for pressure-volume work are not shortened, then it can be seen that the first and second terms (-pdV sy-Adξ sy) refer to the differential change of internal energy in sy, while the last term–as in absolute value is equal to the first term, but has the opposite sign–it represents pressure-volume work in the environment (i.e., the first term represents the work of the system on the environment, while the last term in equation (19) is the work of the environment on the system). Furthermore, the environment can only change volume at the expense of the system volume dV sy = -dV surrounding; the environment and system sy have a constant total volume (V sy+V surrounding = const.). In a quasi-static change of the state of the system, in order for the system and the environment to be in mechanical equilibrium in each infinitesimal step (volume change), the pressures in sy and the environment must be equal, which is possible if the volume of the environment is multiple (infinitely) more significant than the volume of sy (V surrounding≫V sy). In this way, the change in volume in the environment does not affect the pressure of the environment; therefore, the environment behaves as a reservoir of constant pressure. The R symbol will be used as a subscript for physical quantities related to the reservoir (dV sy = -dV R). The last term in equation (19), according to the total differential of internal energy, 1 represents the differential change in the internal energy of the reservoir when its composition does not change (there is no exchange of particles with sy and with the environment of the total system (i.e., composite system: sy + R ≡ Csy); also R is not a reactive system, i.e., no chemical reaction takes place in R). According to equation (19), R does not exchange heat with the system or with the environment of Csy, which means that R is an adiabatic system. Therefore, equation (19) is:

Therefore,

An isochoric adiabatic system (A) is placed in reservoir R that provides a constant pressure in sy; formally, first the chemical reaction takes place in the adiabatic and isochoric sy (B) and only then the adiabatic volume changes in sy (system expansion, C) and R (reservoir compression, C).

It is important to emphasize that enthalpy as a function H(S sy,p sy,ξ sy) depends exclusively on the parameters of system sy. In contrast, the differential enthalpy change (and the finite change) refers to the sum of the system and the pressure reservoir, i.e., to the composite system. Of course, when students learn the properties of enthalpy, in the course of further lectures, superscripts and subscripts for the symbol H are omitted (this also applies to other thermodynamic potentials). Considering, equation (18) the above equality is:

moreover, it has the following equality:

If the differential changes of internal energy and volume are

If the isobaric sy is still located in the adiabatic reservoir of constant pressure R, but sy is no longer adiabatic, then according to equations (14a) and (20) the differential change of enthalpy in Csy is:

of course, as with equation (20), it applies dV

sy = -dV

R. Let the differential change of entropy be dS

ξ

>0 during the differential advancement of the reaction from sy (during the reaction, sy is formally adiabatic and isochoric). If the thermodynamic process from sy is isentropic quasi-static (dS

T = 0 – the maximum useful work is obtained), then in each infinitesimal step of the reaction advancement from sy, the change in entropy dS

ξ

must be compensated with the departure of heat

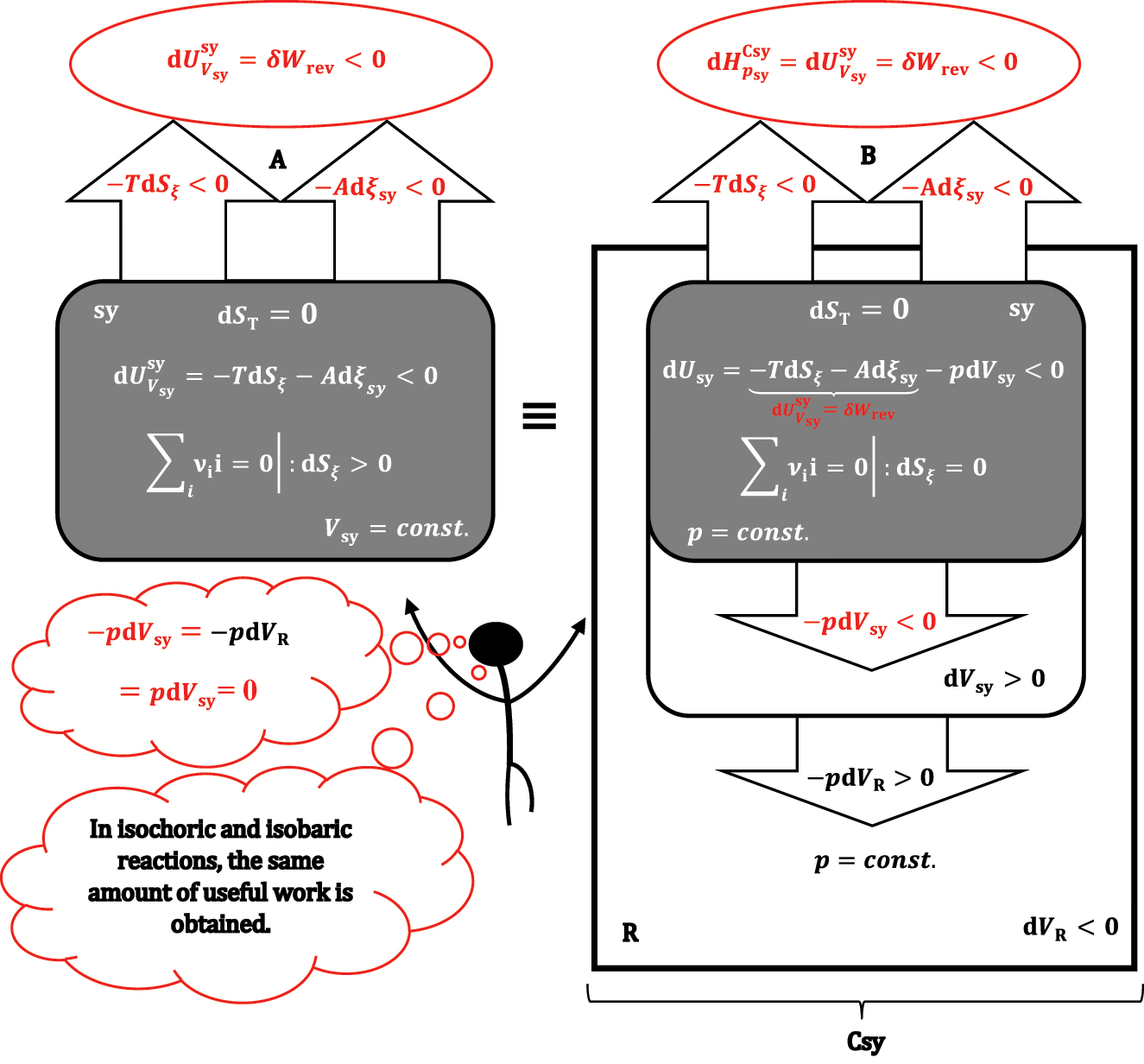

The reaction in the isochoric (A) and isobaric (B) system sy, the isobaric system and the reservoir R form the composite system Csy.

The reaction and heat exchange is followed by a change in the volume of the system and reservoir under formally adiabatic and isobaric conditions. Since the total volume of the composite system (Csy) is constant, when the volume of sy and R changes, the pressure-volume work compensates each other, meaning that equation (26) turns into equality:

As the total entropy change is zero in the isobaric thermodynamic process (27), it follows that the internal energy change of the composite system (enthalpy change at isobaric conditions) is equal to the maximum useful work (δW

rev). From equation (27), it can also be concluded that the same amount of work is obtained (at isentropic conditions) when the reaction takes place at isochoric conditions (

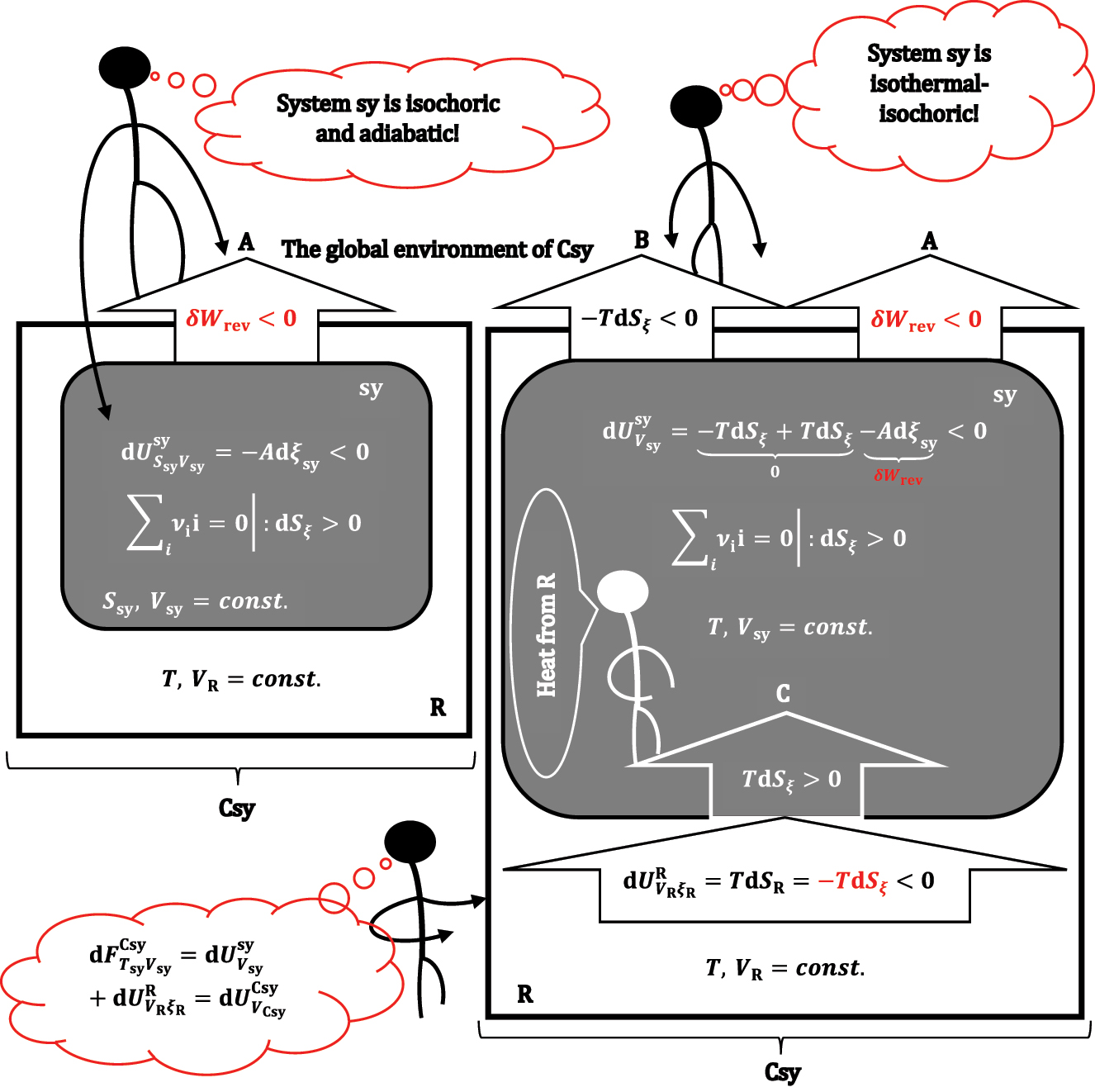

2.3 Differential change of helmholtz free energy

Legendre’s definition of Helmholtz free energy is 7 , 14 , 15 , 16

Therefore, the Helmholtz free energy is a function F = f(T,V,ξ)≡F(T,V,ξ). By differentiating equation (28) and introducing the total differential of internal energy related to system sy, the following equation is obtained:

and if the volume and temperature in sy are constant, i.e., isochoric and isothermal sy is observed, then it is:

Equation (30) corresponds to a chemical reaction during which the entropy of sy does not change (dS

ξ

= 0). Similar to equation (20), in equation (30), the first and second terms refer to the differential change of internal energy in the isochoric system sy:

Considering equations (18) and (30), the equality follows:

or

Equation (32) can be interpreted in two ways. Indeed, during the progression of the exothermic reaction (if the goal is to obtain useful work) from sy, the entropy of the isochoric and adiabatic system does not change (dS

ξ

=0). In each infinitesimal step of the reaction progress, differential useful work is obtained

A reaction whose progress results in a change in the entropy of the system (dS

ξ

≠0). If, for example, an exothermic reaction occurs in an isothermal and isochoric system, then in some infinitesimal step of the quasi-static reaction progress

A formal illustration of the differential change in Helmholtz free energy: first, under adiabatic and isochoric conditions, the chemical reaction (A) progresses infinitely, and the entropy of the system increases infinitely, which is then compensated by the departure of differential heat (in the form of useful work) from sy to the global environment at isothermal and isochoric conditions (B), the lost heat from sy is compensated from the thermoreservoir (C).

Namely, in equation (30), TdS

sy = ∑δq can represents the exchanged heat between sy and other compartments of the global environment, which means that the first term in equation (33) represents the heat leaving the isochoric and isothermal sy (after the infinitesimal progress of the reaction in a formally adiabatic and isochoric system, Figure 7A) to compensate for the infinitesimal increase in entropy (dS

ξ

>0) during the progress of the reaction (Figure 7B). However, since sy is isothermal, heat TdS

ξ

enters the system from the thermoreservoir (Figure 7C). At the same time, the same amount of heat leaves R (-TdS

ξ

) so that the heat that compensates for the entropy of the reaction from sy comes from the thermoreservoir. It follows that equation (33) is equal to equation (10), i.e., the differential change

Based on equation (33a), it can be concluded that if dS ξ is > 0 in the observed reaction from sy, then in each infinitesimal step of the reaction progress, a higher differential useful work is obtained in absolute value than the differential change in internal energy of formally adiabatic and isochoric systems (due to differential progress reactions). On the contrary, if dS ξ < 0, the differential useful work is smaller in absolute value than -Adξ sy since part of -Adξ sy goes to R as heat to compensate for the decrease in reaction entropy in system sy. 21 If expressions (10) and (24)–(27) are compared with expression (33a), then the equality follows:

Namely, if sy is in contact with the corresponding reservoir, then the exchanged energy (heat or pressure-volume work) between the system and the reservoir is mutually compensated, i.e., the net effect is to move some of the internal energy from one part of the composite system to another part. In each infinitesimal step of the progress of the reaction, regardless of the presence of R, the system sy from the composite system behaves as an isochoric system without R and with an infinitesimal change in internal energy:

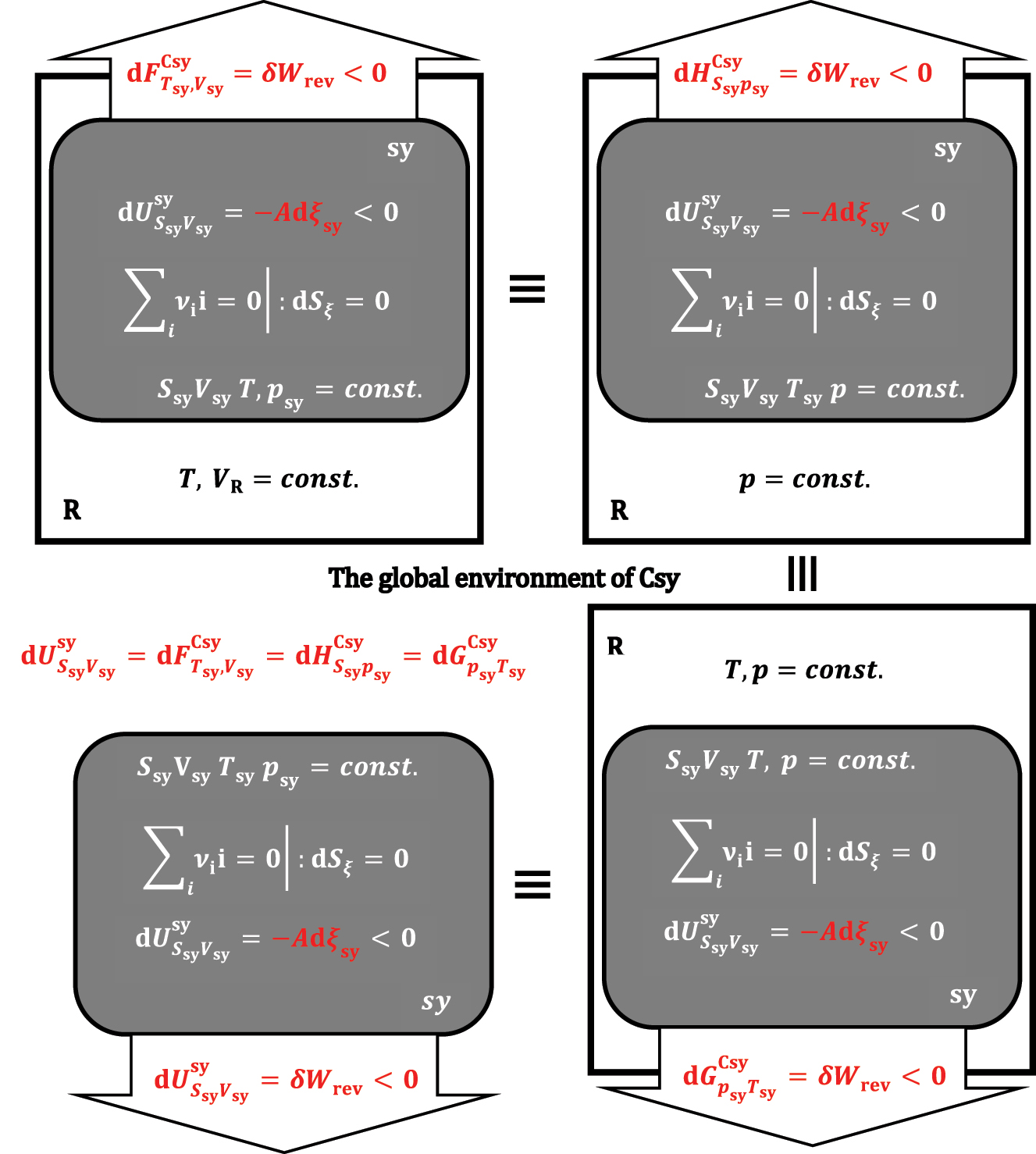

2.4 Differential change of gibbs free energy

The definition of the Gibbs free energy from the internal energy U(S,V,ξ) based on the Legendre transformation is 7 , 14 , 15 , 16

which means that G is a function: G = f(T,p,ξ)≡G(T,p,ξ). We arrive at the expression (36) by differentiating equation (35) and introducing the total differential of the internal energy related to the system sy where one reaction occurs:

If sy is isotherm and isobar, then the above equation is:

In equation (37), the first three terms represent the differential internal energy change in sy. As the H and F functions (thermodynamic potentials) show, appropriate reservoirs of intensive state quantities were required to maintain the system’s constant pressure and temperature. Similarly, with the thermodynamic potential G, a p, T-reservoir (R) is needed to maintain the constant temperature and pressure in sy. The last two terms in equation (37) correspond to the differential internal energy change in R. Since the first term (TdS

sy) and the fourth term (-TdS

sy) in equation (37) are equal in absolute value, it means that R exchanges heat exclusively with sy (analogously, sy can exchange heat exclusively with R). Similarly, the second term (-pdV

sy) and the last term (pdV

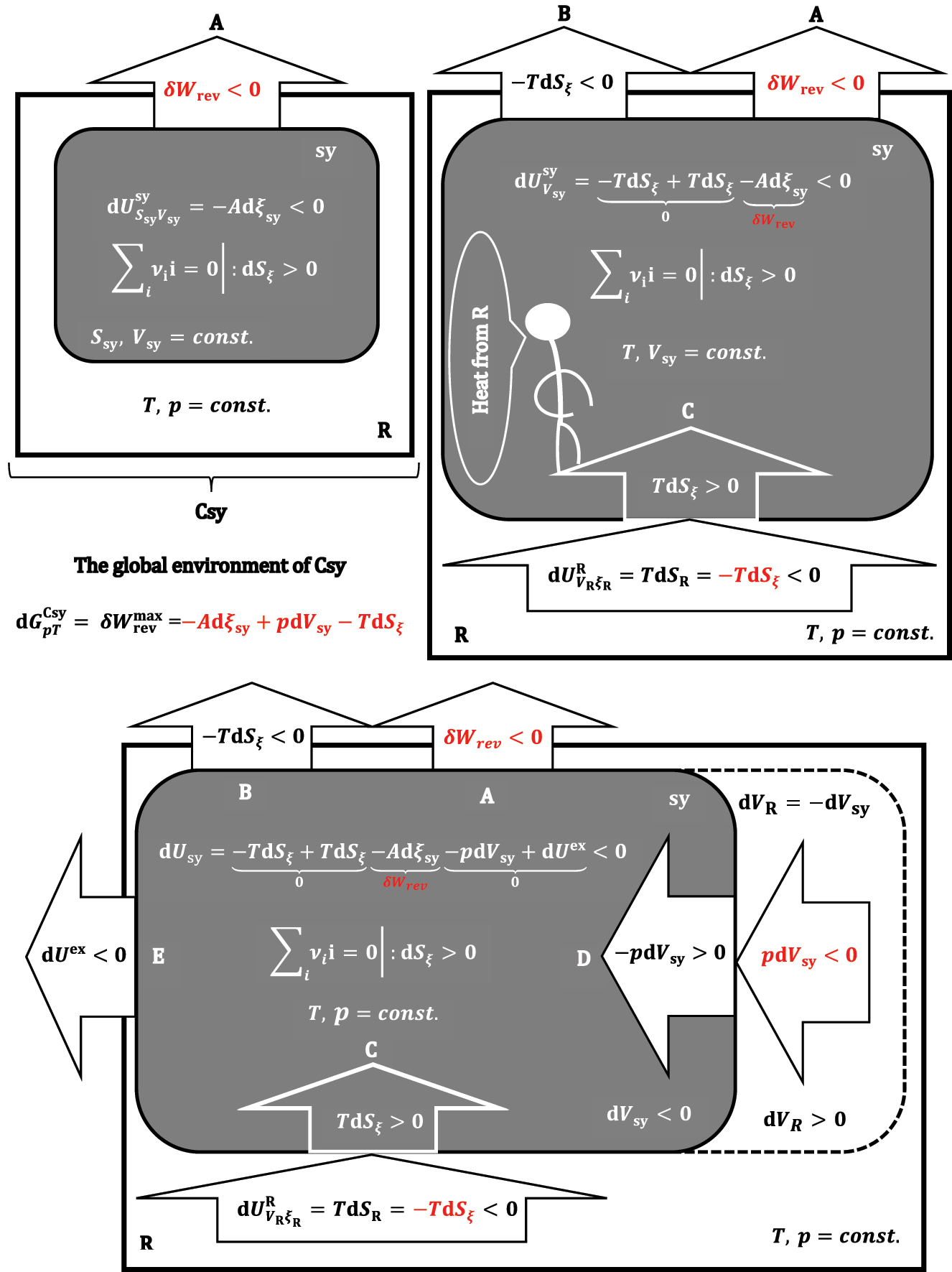

sy) in absolute value are equal to each other and represent the pressure-volume work exchanged between sy and R. It can be concluded that the differential change of Gibbs free energy (37) under isothermal and isobaric conditions represents a differential change of internal energy in the composite system Csy = sy + R (

or

Suppose the reaction progress from sy is not accompanied by a change in the system’s volume and a thermal fluctuation with R. In that case, every system from the composite system is also an isochoric-adiabatic sy and is equivalent to an isochoric-adiabatic system without R.

Let us now study the system (sy) with a p,T-reservoir when the reaction’s progress changes the system’s entropy (dS

ξ

≠0). If, formally, the infinitesimal progression of the exothermic reaction occurs first in a system that is adiabatic and isochoric, then the differential change in internal energy of sy is:

In the above expression, the differential enthalpy change appears, which differs from the differential enthalpy changes introduced by equations (22) and (27) (Figure 10):

A formal illustration of the differential change in equation (39).

Absolute values of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials.

Based on the expression (39), it can be concluded that the global environment of the composite system from Csy receives the differential useful work partly from the system (-Adξ

sy) and partly from the p,T-reservoir (-TdS

ξ

+pdV

sy) (Figure 9). If it is

and

Let the goal be the carry-out of a non-spontaneous chemical reaction in the isentropic and quasi-static regime, and let the differential changes be:

The differential change in Gibbs free energy represents the minimum work (

2.5 Reaction entropy

One more comment remains. Sometimes, during lectures, students ask what precisely the entropy change of a reaction is. It is clear to the students that in exothermic reactions, chemical bonds of different energies are broken and created, and the excess energy can be used as useful work or dissipated in the environment in the form of heat. However, the entropy change during the reaction is quite mysterious for them. In the teaching of physical chemistry and thermodynamics, there is a direction that tends to explain thermodynamic functions (i.e., their changes), if possible (or at least to try) at the molecular (microscopic) level, 22 , 23 which we will also try. Let the entropy change in the system (where the reaction occurs) with p,T-reservoir be followed, and for simplicity, let the reaction mixture in the system (sy) behave as an ideal gas (IG). The partial molar entropy of some components in the IG mixture at pressure p and temperature T and composition x = (x 1…x i …) - the vector of mole fractions in sy–is 24 , 25

where

Since the system contains a reactive mixture, the vector x changes as the reaction progresses. Every component in the system is either a reactant or a product of the studied reaction, and no inert components are present. If the amount (mol) of each component from the reactive mixture is expressed using the stoichiometric coefficient and the degree of progress of the reaction, then taking into account expression (44), equation (45) is (x i(ξ)≡x i = f(ξ)):

The last term in the above equation represents the entropy of mixing depending on the degree of progress of the reaction. As the values of the mole fractions in the mixture are less than unity, lnx i(ξ)<0 follows; therefore, it is:

The second term (

or more generally at some constant pressure:

The first term (

that is, taking into account expressions (47) and (48a):

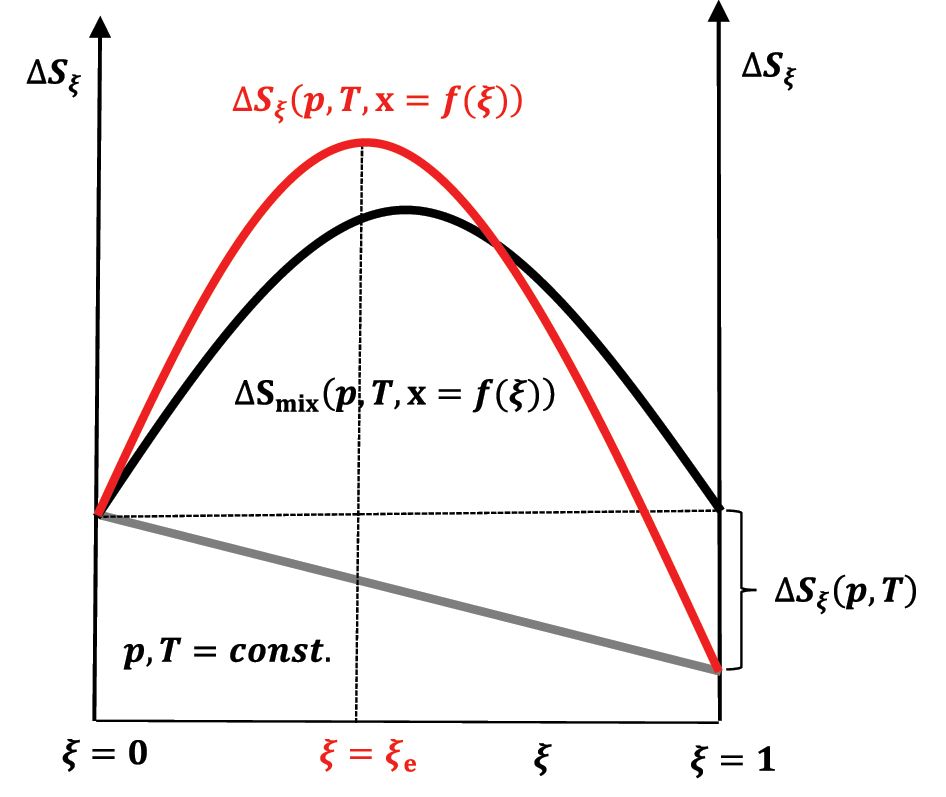

The change in entropy of the system during the reaction progress in case ΔS ξ (p,T) < 0; reactants at time t = 0 are in stoichiometric amount.

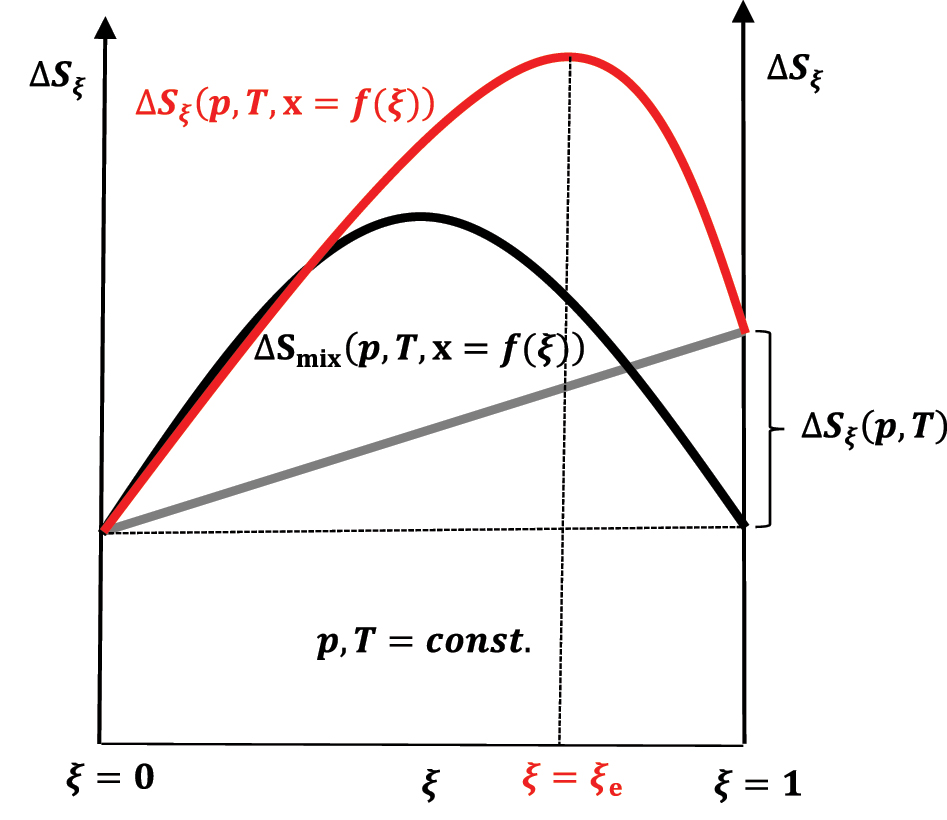

If the first term in equation (50) is zero (ΔS ξ (p,T) = 0) or |ΔS ξ (p,T)<0|<ΔSmix(p,T,x = f(ξ)), then the increase in entropy to the equilibrium state (ξ = ξ e) in the chemical reaction through a series of quasi-static changes of state between ξ = 0 and ξ = ξ e (Figure 11) is a consequence of the entropy of mixing (ΔSmix(p,T,x = f(ξ))>0), which is compensated by the departure of heat from the composite system–an isentropic process–into the global environment as useful work that is superimposed on the useful work that originates from the change in the internal energy of the exothermic reaction (Figure 9). During the quasi-static change of the system’s state during the reaction progress to the equilibrium state, 6 in each infinitesimal step of the progress of the exothermic reaction, the infinitesimal change in the system’s internal energy enters the differential useful work–isentropic process. Of course, if ΔS ξ (p,T)>0 and this is the case when the energy is distributed over a more significant number of the product’s quantum states than there are reactant’s quantum state numbers–the partition function of the product increases concerning the partition functions of the reactants–or by in classical mechanics, energy is distributed over a more significant number of product’s degrees of freedom, then ΔS ξ (p,T) is superimposed on ΔSmix(p,T,x = f(ξ)) and the entropy of the reaction increases to ξ = ξ e>ξ = 0.5ξ = ξ e>ξ = 0.5 (Figure 12). 21 , 26

The change in entropy of the system during the reaction progress in case ΔS ξ (p,T) > 0; reactants at time t = 0 are in stoichiometric amount.

3 Conclusions

Here, differential changes of internal energy and other thermodynamic potentials in a system in which an exothermic reaction takes place are discussed with the aim of obtaining differential useful work. Equations and symbols are derivated for SL students, who, when mastering the material, can follow and analyze in detail every step of a given teaching unit.

What is necessary for every student to take away from this teaching unit is that the differential changes in thermodynamic potentials refer to the differential change in the internal energy of the composite system (system + reservoir). If the composite system is adiabatic and isochoric and the thermodynamic process in the system is isentropic, then the reaction’s progress does not accompany the system’s entropy (reaction entropy) change. The composite system’s differential change in internal energy is equivalent to an adiabatic and isochoric system’s (without a reservoir) differential change in internal energy:

Suppose the entropy of the system increases during the reaction progress. In that case, in order for the thermodynamic process to be isentropic, the reaction entropy must be compensated by the departure of heat from the composite system to the global environment where it contributes to useful work so that the composite system is only isochoric (not adiabatic). The differential change in the internal energy of an isochoric composite system (due to the infinitesimal progress of the reaction from the system) with a pressure reservoir or a thermoreservoir is equal to the differential change in the internal energy of an isochoric reactive system (without a reservoir)

The isochoric composite system, in which the reactive system is simultaneously in contact with a pressure reservoir and a thermoreservoir, deserves special attention. Namely, in this case, the most significant differential change in internal energy in absolute value (isentropic conditions) is obtained from the composite system, i.e., the highest absolute value of the differential useful work (maximum non-expansion work) if the entropy of the system increases during the progress of the exothermic reaction, and the volume of the system decreases at the same time

Correction note

Correction added after online publication on March 24, 2025: In the PDF version, the display of equation (33) has been modified to match its presentation on the website.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Acquisition and analysis of data, literature survey and writing of manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

The extent of reaction ξ, considering the reaction equation as it is written, may be calculated by dividing the number of times the chemical transformation occurs by the Avogadro constant, which means that it has the dimension of mol (sometimes denoted by mol-rxn). 9 The extent of a chemical reaction is an extensive variable whose value ranges from zero to the theoretical maximum value. The amount of some reactant r and some product p belonging to the same reaction in time t if the extent of reaction has the value ξ(t) is:

In the above equations, ν r<0 and ν p>0 are the stoichiometric coefficients of the selected reactant and product in the observed reaction. Before the start of the reaction, the amount of reactant r is n r(t = 0); this amount of the observed reactant decreases with the progress of time during the reaction. Equations (A1) and (A3) follow the definition of the extent of reaction:

If the initial amount of each reactant is equal to the stoichiometric coefficient, then the extent of the chemical reaction if the total stoichiometric amount of reactants is converted into the stoichiometric amount of products (i.e., one mole of the observed reaction takes place), according to equations (A3) and (A4), is:

Suppose the reactants are in a non-stoichiometric relationship. In that case, a normalized extent of reaction can be introduced (normalization to a value of 1), which is explained in detail in the literature references. 9 , 10

The change in Gibbs free energy of a reaction at constant temperature and pressure is:

The slope of the Gibbs free energy function from the extent of the chemical reaction according to De Donder’s equation (2) is:

Multiplying the above equation by dS sy gives:

References

1. Felder, R. M.; Silverman, L. K. Learning and Teaching Styles. Engr. Education. 1988, 78 (7), 674–681.Search in Google Scholar

2. Litzinger, T. A.; Lee, S. H.; Wise, J. C.; Felder, R. M. A Psychometric Study of the Index of Learning Styles©. J. Eng. Educ. 2007, 96 (4), 309–331; https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2007.tb00941.x.Search in Google Scholar

3. McCaulley, M. H. Psychological Types of Engineering Students – Implcations for Teaching. Engr. Education 1977, 66 (7), 729–736.10.1017/S003329170000653XSearch in Google Scholar

4. McCaulley, M. H.; Godleski, E. S.; Yokomoto, C. F.; Harrisberger, L.; Sloan, E. D. Applications of Psychological Type in Engineering Education. Engr. Education 1983, 73 (5), 394–400.Search in Google Scholar

5. Hebb, D. O. Textbook of Psychology; W. B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, 1972.Search in Google Scholar

6. Glasser, L. Correct Use of Helmholtz and Gibbs Function Differences, ΔA and ΔG: The Van’t Hoff Reaction Box. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93 (5), 978–980. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00925.Search in Google Scholar

7. Callen, H. B. Thermodynamics and Introduction to Thermostatistics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc: Singapore, 1985.Search in Google Scholar

8. Daily, J. W.. Statistical Thermodynamics an Engineering Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridg, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

9. Moretti, G. The “Extent of Reaction”: a Powerful Concept to Study Chemical Transformation at the first-Year General Chemistry courses. Found. Chem. 2015, 17 (2), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10698-014-9212-x.Search in Google Scholar

10. Novak, I. Efficiency of Reversible Reaction: A Graphical Approach. Chem. Teach. Int. 2022, 4 (3), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2022-0004.Search in Google Scholar

11. Kondepudi, D.; Prigogine, I. Modern Thermodynamics, from Heat Engines to Dissipative Structures; John Wiley & Sons Inc: Chichester, 2002.Search in Google Scholar

12. Poša, M. Connecting De Donder’s Equation with the Differential Changes of Thermodynamic Potentials: Understanding Thermodynamic Potentials. Found. Chem. 2024, 26 (2), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10698-024-09507-z.Search in Google Scholar

13. Engel, T.; Reid, P. Thermodynamics, Statistical Thermodynamics, & Kinetics 2nd ed.; Pearson Education Inc: Upper Saddle River, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

14. Keszei, E. Chemical Thermodynamics; An Introduction; Springer-Verlag: Berlin-Heidelberg, 2012.10.1007/978-3-642-19864-9Search in Google Scholar

15. Alberty, R. A. Use of Legendre Transforms in Chemical Thermodynamics. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73 (8), 1349–1380. https://doi.org/10.1515/iupac.73.0802.Search in Google Scholar

16. Xiaofei, X.; Weiqiang, T.; Qingwei, G.; Chongzhi, Q.; Yangfeng, P.; Shuangliang, Z. Explaining Thermodynamic Potential to Undergraduates. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (11), 4714–4721. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00351.Search in Google Scholar

17. Keifer, D. Enthalpy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96 (7), 1407–1411. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00326.Search in Google Scholar

18. Hladky, P. W. From Bunsen Burners to Fuel Cells: Invoking energy Transducers to Exemplify “Paths” and Unify the Energy-Related Concepts of Thermochemistry and Thermodynamics. J. Chem. Educ. 2009, 86 (5), 582–586. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed086p582.Search in Google Scholar

19. Noll, R. J.; Hughes, J. M. Heat Evolution and Electrical Work of Batteries as a Function of Discharge rate: Spontaneous and Reversible Processes and Maximum Work. J. Chem. Educ. 2018, 95 (5), 852–857. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00653.Search in Google Scholar

20. Raff, L. Principles of Physical Chemistry; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, 2001.Search in Google Scholar

21. Atkins, P. W. Physical Chemistry, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2002.Search in Google Scholar

22. Hanlon, R. T. Deciphering the Physical Meaning of Gibbs’s Maximum Work Equation. Found. Chem. 2024, 26 (1), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10698-024-09503-3.Search in Google Scholar

23. Stephan, F. C. An Integrated, Statistical Molecular Approach to the Physical Chemistry Curriculum. J. Chem. Educ. 2009, 86 (12), 1397–1401. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed086p1397.Search in Google Scholar

24. Sandler, S. I. Chemical, Biochemical, and Engineering Thermodynamics 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc: Asia, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

25. Lozar, J. Thermodynamique des Solutions et des Mélanges; Elipses: Paris, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

26. Nash, L. K. Elements of Statistical Thermodynamics; Dover Publications: Mineola, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Non-formal chemistry learning: a scoping review

- Research Article

- Discussion on definition and understanding of the thermodynamic spontaneous process

- Good Practice Report

- A molecular motion-based approach to entropy and application to phase transitions and colligative properties

- Research Articles

- Interrelationship of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in a system in which a reaction takes place intending to obtain useful work in isentropic conditions–lectures adapted to sensing learners

- A role-playing tabletop game on laboratory techniques and chemical reactivity: a game-based learning approach to organic chemistry education

- Predominant strategies for integrating digital technologies in the training of future chemistry and biology teachers

- Enhancing conceptual teaching in organic chemistry through lesson study: a TSPCK-Based approach

- Enhancing chemistry understanding and attitudes through an outreach education program on circular plastic economy: a case study with Thai twelfth-grade students

- Process oriented guided inquiry learning: a possible solution to improve high school students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and attitude

- Good Practice Report

- Portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry

- Research Article

- Determination of total hardness of water sample by titration using double burette method: an economical approach

- Good Practice Reports

- Interpretation of galvanic series when teaching metal corrosion

- Synthesis of valproic acid for medicinal chemistry practical classes

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Non-formal chemistry learning: a scoping review

- Research Article

- Discussion on definition and understanding of the thermodynamic spontaneous process

- Good Practice Report

- A molecular motion-based approach to entropy and application to phase transitions and colligative properties

- Research Articles

- Interrelationship of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in a system in which a reaction takes place intending to obtain useful work in isentropic conditions–lectures adapted to sensing learners

- A role-playing tabletop game on laboratory techniques and chemical reactivity: a game-based learning approach to organic chemistry education

- Predominant strategies for integrating digital technologies in the training of future chemistry and biology teachers

- Enhancing conceptual teaching in organic chemistry through lesson study: a TSPCK-Based approach

- Enhancing chemistry understanding and attitudes through an outreach education program on circular plastic economy: a case study with Thai twelfth-grade students

- Process oriented guided inquiry learning: a possible solution to improve high school students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and attitude

- Good Practice Report

- Portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry

- Research Article

- Determination of total hardness of water sample by titration using double burette method: an economical approach

- Good Practice Reports

- Interpretation of galvanic series when teaching metal corrosion

- Synthesis of valproic acid for medicinal chemistry practical classes