Abstract

The main purpose of this study is to develop a portable syringe experiment kit for easy demonstration of the chemical kinetics of H2, C2H2, and CO2 gas-generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry classrooms. The main apparatus comprises two large (A and C) and one small (B) Luer-lock-tip syringes connected with a 3-way stopcock. Ignition is applied to test H2 and C2H2 gases. In contrast, the turbidity of lime water is used to test CO2 gas. The effects of reactant species and concentrations on the reaction rates were demonstrated. The syringe kit was implemented through the 5E inquiry learning process for a group of 33 grade 11 students, leading to an improvement in their conceptual test scores on chemical reaction rates from 33.94 % to 78.03 %, with a normalized gain in the medium range (<g = 0.67>). This suggests that using the syringe kit within the 5E inquiry learning framework effectively supported students in developing a more accurate conceptual understanding of reaction rates.

1 Introduction

Chemical kinetics or chemical reaction rate is one of the most challenging topics in chemistry since it involves many factors influencing the reaction rate (i.e., chemical species, temperature, concentration, and surface area) and requires some mathematical calculation (Justi, 2003). Students often find chemical kinetics challenging, particularly when defining reaction rates, integrating rate laws, and grasping reaction mechanisms. These difficulties can make problem-solving in kinetics a struggle, as understanding these abstract concepts requires both conceptual knowledge and mathematical skills (Stroumpouli & Tsaparlis, 2022). In addition, students are required to relate among the three levels of representation in chemistry, including (1) what they observe at a macroscopic level from experiments, (2) how to explain the changes by using an understandable symbolic level, and (3) what happens at particulate or sub-microscopic level (Luviani et al., 2021; Sotiriou & Bogner, 2008). In addition, students have to integrate the knowledge of thermochemistry, chemical reaction rate, and chemical equilibrium to deeply understand chemical reactions (Michalisková et al., 2019). Stroumpouli & Tsaparlis (2022). Many students in Thailand, as well as other countries, encountered these learning difficulties. These can lead students to accommodate mis- or alternative conceptions in chemical kinetics and further cause them to accommodate more alternative conceptions in other related topics (Stears & Gopal, 2014).

1.1 Conceptual understanding of chemical reaction rate

There are many studies on students’ conceptions of the topic of chemical reaction rate or chemical kinetics. For example, Çalik and his colleagues (Çalik et al., 2010) examined previous studies and identified problems encountered in learning the concept of chemical reaction rate. Some of these problems are (1) inability to define the rate of reaction, (2) misunderstanding, misapplying, or misinterpreting of the relationship between the rate of reaction and its influencing factors, and (3) lack of understanding of how activation energy and enthalpy relate the rate of reaction. They also investigated the effects of conceptual change pedagogy on Students’ conceptions. They found that the conceptual change pedagogy intervention helped the students to notice and correct their alternative conceptions. They suggested that combining various conceptual change methods may be more effective in decreasing student alternative conceptions.

They also explored the alternative conceptions of chemical reaction rates generated by Turkish chemistry teachers and students (grade 11). They found that chemistry teachers and students tended to accommodate similar alternative conceptions, which may be transmitted from the chemistry teachers. Examples of some alternative conceptions include: (1) lack of understanding of how enthalpy affected the rate of reaction and reaction mechanism of the reaction, and (2) misunderstanding/misapplying of the relationship between temperature or concentration and the rate of reaction (Çalik et al., 2010).

The following example concerns Thai students’ learning of chemical kinetics, which was investigated by Chairam and his colleagues (Chairam et al., 2009). It was reported that chemical kinetics is an essential concept in introductory chemistry. In Thailand, high school and undergraduate students typically begin learning chemical kinetics, focusing on qualitative aspects. Students are usually introduced to reaction rates and the factors that influence them. The study also explored the impact of inquiry-based learning activities, where first-year undergraduate science students at a public university in Thailand were asked to design and conduct an experiment investigating acid-base reactions. The results indicated that this more engaging hands-on teaching helped students build a strong conceptual understanding of chemical kinetics. A study by Supasorn and colleagues (Supasorn et al., 2022) examined grade 11 students’ understanding of reaction rates before and after they participated in the small-scale syringe-vial experiment (SSVE) and used the AR interactive Particulate-level Visualization (ARiPV) within the 5E inquiry-based learning framework at a typical upper secondary school in Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand. Initially, most students fell into partial understanding with specific misconceptions (PMU), with no students achieving good understanding (GU). Following the intervention, most students improved to partial understanding (PU), with no students remaining in the no understanding (NU) category. This study demonstrated that the integrated approach helped students better understand reaction rates.

Based on the literature review above, inquiry activities have proven effective in supporting students’ conceptual understanding of chemical kinetics. However, many upper secondary schools in Thailand encounter severe limitations in implementing conventional chemistry experiments. These limitations include insufficient equipment and chemicals, no toxic waste management system, time consumption of experimental activities, and inadequate skilled instructors for preparation and teaching experiments (Khattiyavong et al., 2014). du Toit & du Toit (2025) state that understanding chemistry is crucial for future solutions, so chemistry should be more accessible to all students. They suggest that micro-scale or small-scale chemistry is one of the effective ways to make chemistry more accessible. As a result, a portable syringe kit demonstrating the chemical kinetics of gas-generating reactions was developed to minimize the stated limitations (Supasorn et al., 2021; Supasorn et al., 2022). In addition, the kit must be repeatable, easy to set up, demonstrate, clean, safe to perform, and easy to observe changes. Please note that this article mainly discusses developing and validating the experimental kit as a demonstration tool for qualitative comparison among various gas-generating reactions.

1.2 Gas generating reactions

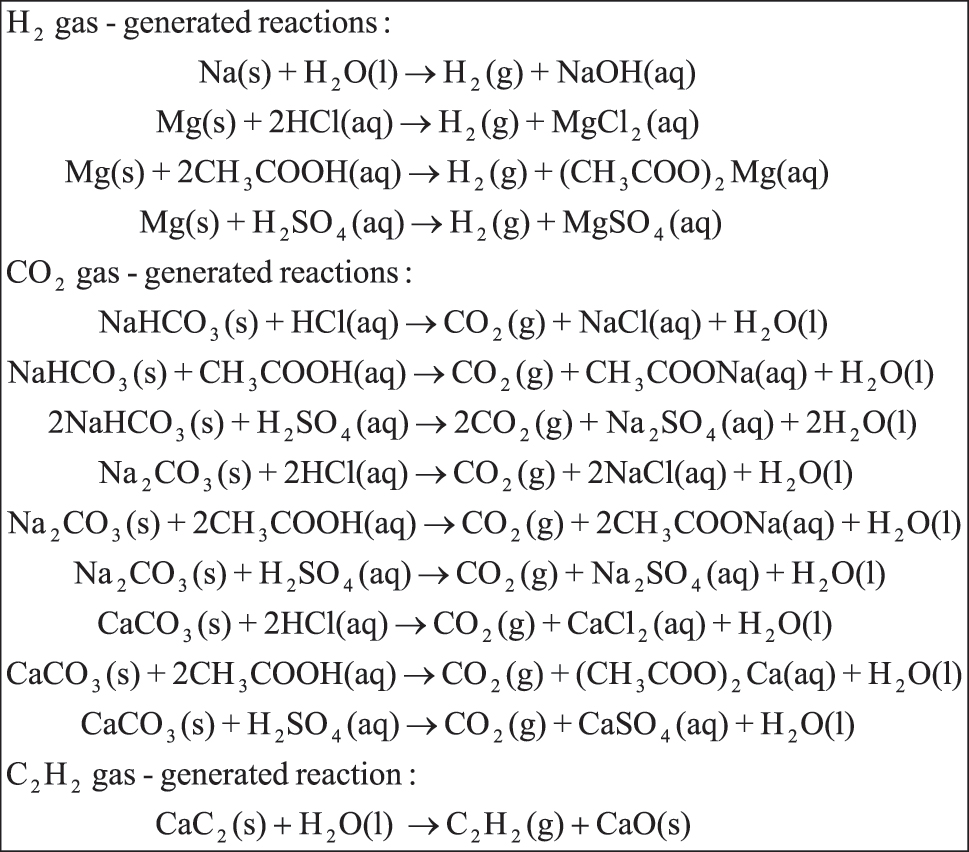

There are many reactions involving gas generation. Some of those are shown below (Herr & Cunningham, 1999).

However, this article only studies the reactions producing hydrogen (H2), carbon dioxide (CO2), and acetylene (C2H2) gases. In other words, the H2 gas was generated from the reactions of sodium metal (Na) with distilled water (H2O) and magnesium (Mg) ribbon or zinc metal (Zn) with various acids (Herr & Cunningham, 1999). The CO2 gas was generated from the reactions of bicarbonate (HCO3 −) or carbonate salts (CO3 2−) with various acids (Chairam et al., 2009). The C2H2 gas was generated from calcium carbide (CaC2) reactions with distilled water (Chang & Overby, 2019). The reaction equations for the above gas-generating reaction are shown in Figure 1.

H2, CO2, and C2H2 gas generating reactions (Chang et al., 2019).

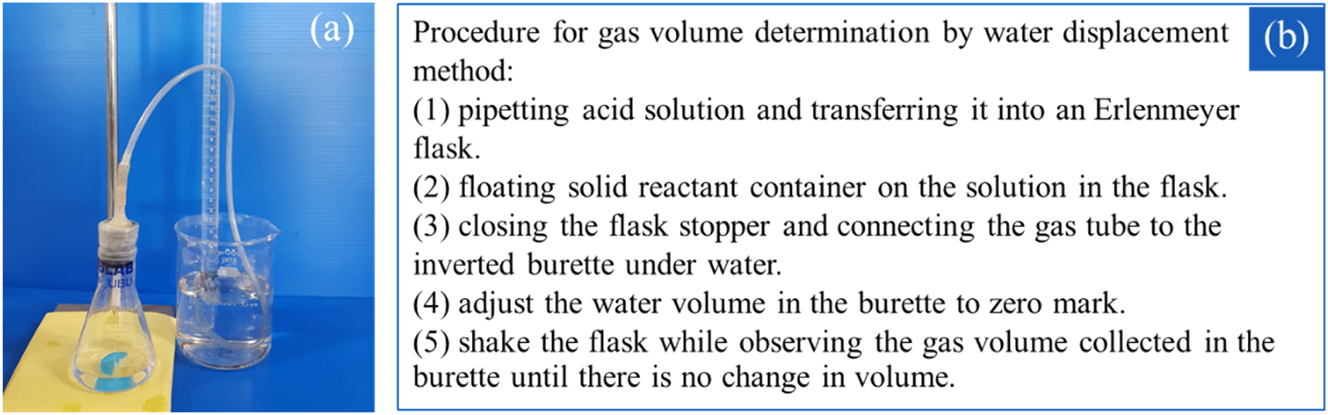

Typically, water displacement in a glass burette or a graduated cylinder can be used as the standard traditional method for measuring the volume of gas generated from any reaction (Chairam et al., 2009). As shown in Figure 2, the syringe was used as an alternative method for measuring the volume of gas in this experimental kit.

Gas volume determination by water displacement, (a) apparatus setup, (b) procedure for gas volume determination.

1.3 Chemistry in the syringe

There are many studies investigating chemical reactions via syringe systems. For example, a series of small-scale gas experiments aimed at enhancing safety and engagement in chemical education. Developed by Obendrauf (2006), these experiments minimize chemical hazards and waste while allowing students to witness visually striking reactions. The experiments cover gas production (e.g., chlorine, hydrogen, acetylene) and reactions between gases, such as the photolytic reaction of hydrogen and chlorine, which can be ignited by light, and the explosive mixture of hydrogen and oxygen. The experiments are designed to appeal to students’ emotions and curiosity, making theoretical concepts more memorable through visually appealing or intense demonstrations. Another example Ng et al. (2020) provided introduced a safe, engaging method for conducting gas-generating experiments in educational settings using disposable plastic syringes, where hydrochloric acid reacts with calcium carbonate to produce CO2 gas. The generated gas is measured by channeling it into an inverted burette for accurate volume recording. This technique minimizes exposure to hazardous chemicals and teaches fundamental concepts such as reaction rates and gas measurement, emphasizing laboratory safety and handling practices for young science students. The last example is a portable, low-cost syringe-vial kit designed by Supasorn et al. (2021) to demonstrate chemical reaction rates through gas-generating reactions, specifically CO2 gas generation from sodium bicarbonate and acid. The setup consists of a syringe, vial, and 3-way stopcock, allowing easy real-time observation of gas production and reaction rates. Tested in high school classes, the kit was shown to improve student understanding of reaction rates through hands-on, inquiry-based learning activities. The kit’s portability, simplicity, and safety make it ideal for educational use in diverse classroom settings.

Building on the reviewed literature, we introduce a portable syringe kit to demonstrate gas-generating reactions in upper secondary school chemistry easily. This kit addresses several common experimental challenges, such as limited chemical supplies, a lack of advanced equipment, and time constraints. It provides a simple, effective way to illustrate key concepts like chemical reactions and reaction rates.

2 Methods

This study used a one-group pretest/posttest design. Before data collection, human research ethics were approved with the code number UBU-REC-07/2563 (Ubon Ratchathani University Research Ethics Committee, 2020).

2.1 Treatment tool: portable syringe kit of gas generating reaction

This study used the portable syringe kit to demonstrate a gas-generating reaction as its treatment tool. This kit was adapted from the workshop entitled “Enjoy Chemistry Experiments with Syringe: Use syringes and 3-way cocks to carry out small-scale experiments” provided by Han & Kim (2013) at the 2013 ISMTEC organized by the Institute for the Promotion of Teaching Science and Technology (IPST) in Thailand, and adapted from the study of Nilsson & Niedderer (2012) in which they simulated that “chemical reaction between sodium and water takes place, and hydrogen gas is formed, in which the volume of the formed hydrogen gas can be determined by leading the gas into a syringe.” The idea of how to determine the volume of the generated gas was applied from the small-scale syringe-vial experiment (SSVE) on the rate of CO2 gas-generated reactions previously developed by our team (Supasorn et al., 2021; Supasorn et al., 2022). The kit was also designed based on Green Chemistry principles, which include reducing the amounts of chemicals used, toxic chemicals, and generated wastes (Poliakoff & Licence, 2007). Details of the kit are as follows.

2.1.1 Chemicals

The chemicals used for generating H2 gas were magnesium ribbon (Mg) and a variety of acids (HCl, H2SO4, and CH3COOH) with various concentrations (0.10 M and 0.50 M). The reaction of Na with distilled water was the other way to generate the H2 gas. Please beware of demonstrations involving Na as it is very reactive with air and water. The chemicals for generating CO2 gas include bicarbonate and carbonate compounds (NaHCO3, Na2CO3, and CaCO3) and various acids with various concentrations. Acetylene (C2H2) gas was produced by reacting calcium carbide (CaC2) with distilled water. Ignition and flammability were applied for H2 and C2H2 tests, while turbidity of lime water (Ca(OH)2) solution was used for the CO2 test. A small amount of phenolphthalein indicator was added to all solutions, but not to distilled water in syringe C, to indicate if the reaction mixtures are acid or base. In other words, the reaction mixture will turn pink if the reaction product is base, and it will still be colorless if it is acid or neutral (Chang et al., 2019). In addition, the increase or decrease of temperature of the reaction mixture in syringe A can indicate that the reaction is exothermic or endothermic, respectively. This can be easily observed by touching or measuring by using a thermometer.

2.1.2 Hazards and cautions

When preparing acid solutions from concentrated hydrogen chloric acid (HCl), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), and glacial acetic acid (CH3COOH), please do it under a fume hood and wear gloves, goggles, and lab coat. These acids can cause corrosion to the skin, eyes, nose, mucous membranes, and both the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Inhaling hydrogen chloride may result in pulmonary edema, while ingestion can severely damage the mouth, throat, esophagus, and stomach. Exercise caution when conducting experiments with sodium metal (Na), as it reacts vigorously with water, releasing highly flammable hydrogen gas. Contact of sodium metal with skin, eyes, or mucous membranes can result in severe burns. Be sure to store Na in oil when not in use. When conducting a gas-generating reaction in a syringe kit, use only the recommended amount of reactant to prevent excessive pressure buildup. In addition, a safety briefing covering essential laboratory procedures was held before students began the experiment. The experimental setup was carefully assembled and tested beforehand to reduce the chance of leaks and spills (Ng et al., 2020). Safety considerations include using minimal amounts of reactive materials, avoiding strong light exposure for light-sensitive reactions, and using explosion screens for protection. Equipment primarily involves syringes, needles, rubber bungs, and small amounts of chemicals, with syringes acting as reaction vessels and collection devices.

2.1.3 Equipment and apparatus

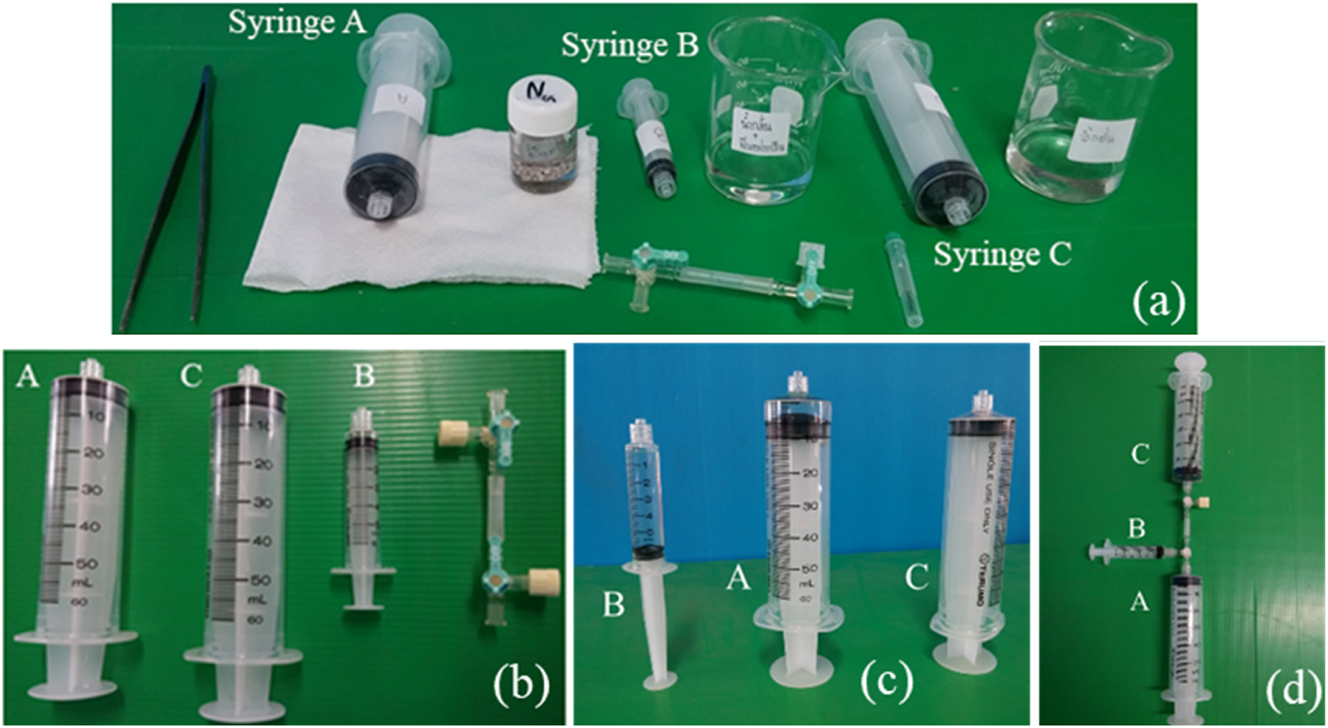

This setup involved two large and one small syringe, a 3-way stopcock, a needle, and chemical and solution containers. Luer-lock-tip syringes are preferred for tight connection (see Figure 3a).

The syringe kit demonstration, (a) preparing chemicals and equipment, (b) preparing syringe kit, (c) transferring chemicals into syringes, and connecting syringe kit using 3-way connector.

2.1.4 General procedure

Prepare all chemicals, solutions, syringes, a 3-way stopcock or connector, and equipment as shown in Figure 3a and b. In the case of Na, it should be cleaned before use, and all the rest of the Na metal should be soaked in oil to prevent any unexpected ignition. Teacher or expert demonstration is advised for the reaction of Na and water. To demonstrate such a reaction, the solid and liquid reactants are placed in syringes A and B, while distilled water is placed in syringe C as a gas filter (see Figure 3c).

Connect these three syringes by using a 3-way stopcock, in which syringes A, B, and C are in the lower, horizontal, and upper positions, and then push the plunger of syringe B to transfer liquid reactant to react with solid reactant in syringe A (ensure that syringe A connected to syringe B, but C) as shown in Figure 4a. Then, observe the reaction progress, temperature change (endothermic or exothermic), and color change of the reaction mixture, as shown in Figure 4b. After the reaction is complete, push the plunger of syringe A to collect the gas in syringe C, remove all liquid from syringe A, and observe the generated gas volume. Please ensure that syringe A connects to syringe C, but B. Remove syringe C from the 3-way stopcock and put a needle instead. Push the plunger of syringe C to transfer the generated gas through the needle to test the gas. Ignition and flammability were applied for testing H2 and C2H2 gasses (see Figure 4c), while turbidity of lime water (Ca(OH)2) solution was used for testing CO2 gas.

The syringe kit demonstration, (a) assembly of the kit, (b) initiating of the reaction, and (c) ignition test of C2H2 gas generated from the reaction.

Three experts, one chemistry professor, and two chemistry education professors, validated this experimental kit. Any suggestions from the experts were considered to improve its effectiveness and usability. Please note that some reactions may produce heat, react very fast, and produce high pressure. These can cause the syringes to disconnect or push the plungers off the syringes. As a result, please proceed with caution and hold all syringes and plungers tightly.

2.2 Data collecting tool

This study used a conceptual test of chemical reaction rate as one of its two data-gathering instruments. The test contained 20 multiple-choice questions regarding chemical reaction rate, including three topics: the definition of reaction rate (questions 1–6), energy and reaction progress (questions 7–11), and factors influencing rate (questions 12–20). Please note that all research materials were written in Thai, and classes were taught in Thai. This article’s samples were all translated into English.

2.3 Participants

The participants of this study were 33 grade-11 students in one regular classroom from a large high school in the Thailand province of Ubon Ratchathani. With the previous agreement of the school principal and the chemistry instructor, in the 2nd semester of the academic year 2020 (November 2020 to February 2021), all participants signed informed consent forms and approved the study’s report and publishing to utilize their conceptual test data anonymously.

2.4 Implementation of portable syringe kit demonstration on chemical reaction rate

During the chemical reaction rate topic, the pre-conceptual test on chemical reaction rate took students 30 min to complete before the implementation, also called the pretest. Following that, a group of three to four students engaged in three 2-h inquiry-based learning activities using a portable syringe kit demonstration to investigate chemical reaction rate as follows: (1) demonstrations of H2 gas generating reactions, (2) demonstrations of CO2 and C2H2 gas generating reactions, and (3) factors influencing the rate of gas generating reactions. These activities were performed in a typical classroom environment. The 5E inquiry learning cycle provided the foundation for each initially created by Bybee (2014; as cited in Joswick & Hulings, 2024). In each 5E inquiry learning activity, the students were engaged with a scientifically-oriented question regarding chemical reaction rate (E1: Engagement step) and then explored data by performing a portable syringe kit demonstration of a generating reaction (E2: Exploration step). Next, they formulate explanations based on their experimental data (E3: Explanation step) and then relate or connect these explanations to principles and other scenarios involving reaction rates (E4: Elaboration step). Finally, their understanding was assessed through discussions, questions, and answers in both group and class settings (E5: Evaluation step). Finally, the post-conceptual test on chemical reaction rate took students 30 min to complete after the implementation, also called the post-test (identical to the pre-test but with the choices rearranged).

3 Results and discussion

The results of this study are divided into two parts: (1) experimental results of the portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reaction and (2) students’ conceptual test scores of chemical reaction rate before and after performing the portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reaction.

3.1 Experimental results of the portable syringe kit demonstration

The variety of H2, CO2, and C2H2 gas-generating reactions were observed using this syringe demonstration; please find the chemical equations for each gas in Figure 1. The % yields of gas products from the small-scale reactions using the syringe kit were in the range of 76–86, slightly lower than those of the conventional scale reactions (82–93). Furthermore, investigations of chemical reaction rates using the small-scale syringe kit could be completed within 6 min. In contrast, those using the conventional scale and water displacement method could take up to 25 min. For the H2 gas-generating reactions (see Table 1), the following reactions were compared to demonstrate some effects on the reactions of Na and Mg with water and acids. Reactions No.1.1 and No.1.2 demonstrate that Na is more reactive than Mg as it can rapidly react with water, while reactions No.1.2 and No.1.3 demonstrate that Mg reacts with acid but water. Reactions No.1.3 and No.1.4 demonstrate that the reaction of monoprotic HCl acid and Mg produces less H2 gas than diprotic H2SO4 acid, while reactions No.1.3 and No.1.5, strong HCl acids, react with Mg more rapidly than weak CH3COOH acid. In addition, reactions No.1.3 and No.1.6 also demonstrate that increasing acid concentration increases the reaction rate. In addition, the appearance of pink color and the warming of the reaction mixture in syringe A indicates that the reaction mixture is basic and exothermic. The H2 gas can be tested using ignition, and rarely visible yellow or orange flame can be observed.

Demonstration of H2 gas generating reactions.

| No. | Reactant in syringe | Observation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Aa | Liquid Bb | Gas volumec | Rated | Colore | |

| 1.1 | Na | H2O | ++++ | xxxxx | Turn pink + vw |

| 1.2 | Mg | H2O | – | – | Colorless + n |

| 1.3 | Mg | 0.10 M HCl | ++ | xx | Turn pink + w |

| 1.4 | Mg | 0.10 M H2SO4 | +++ | xxx | Turn pink + w |

| 1.5 | Mg | 0.10 M CH3COOH | + | x | Turn pink + w |

| 1.6 | Mg | 0.20 M HCl | ++++ | xxxx | Turn pink + w |

-

aAmount of reactant A is ∼23 mg for Na and ∼24.3 mg for Mg (∼1.0 mmol). bAmount of reactant B is 10.00 mL (∼1.0 mmol). cNumber of + roughly indicates the amount of gas volume. dNumber of x roughly indicates the rate of reaction. en, w and vw indicate normal, warm, and very warm reactions.

For the CO2 gas-generating reactions (see Table 2), reactions No.2.1 and No.2.2 demonstrate that NaHCO3 reacts with acid slower than Na2CO3, resulting in less gas product, while reactions No.2.3 and No.2.2 demonstrate that increasing concentration of acid increases the volume of gas product. The CO2 gas can be tested using turbidity of lime water. For the quantitative experiment to investigate the rate of CO2-generating reaction and factors influencing the rate, please study supplementary materials.

Demonstration of CO2 gas generating reactions.

| No. | Reactant in syringe | Observation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Aa | Liquid Bb | Gas volumec | Rated | Colore | |

| 2.1 | NaHCO3 | 0.10 M HCl | + | x | Turn pink + n |

| 2.2 | Na2CO3 | 0.10 M HCl | ++ | xx | Turn pink + n |

| 2.3 | Na2CO3 | 0.20 M HCl | ++++ | xxxx | Turn pink + n |

-

aAmount of reactant A is ∼84 mg for NaHCO3 and ∼106 mg for Na2CO3 (∼1.0 mmol). bAmount of reactant B is 10.00 mL (∼1.0 mmol). cNumber of + roughly indicates the amount of gas volume. dNumber of x roughly indicates the rate of reaction. en, w and vw indicate normal, warm, and very warm reactions.

For the C2H2 gas-generating reactions (see Table 3), reactions No.3.1 and No.3.2 demonstrate that increasing the amount of CaC2 increases the volume of the gas product. In contrast, reactions No.3.2 and No.3.3 demonstrate that increasing the volume of water may not increase the reaction product since CaC2 is a limited reagent of this reaction. The C2H2 gas can be tested using combustion in which the flame is very bright.

Demonstration of C2H2 gas generating reactions.

| No. | Amount in syringe | Observation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaC2 in A | H2O in B | Gas volumea | Rateb | Colorc | |

| 3.1 | 1.00 g | 5.00 mL | + | x | Turn pink + vw |

| 3.2 | 2.00 g | 5.00 mL | +++ | xx | Turn pink + vw |

| 3.3 | 2.00 g | 10.00 mL | +++ | xxx | Turn pink + vw |

-

aNumber of + roughly indicates the amount of gas volume. bNumber of x roughly indicates the rate of reaction. cn, w and vw indicate normal, warm, and very warm reactions.

3.2 Students’ conceptual test score of chemical reaction rate

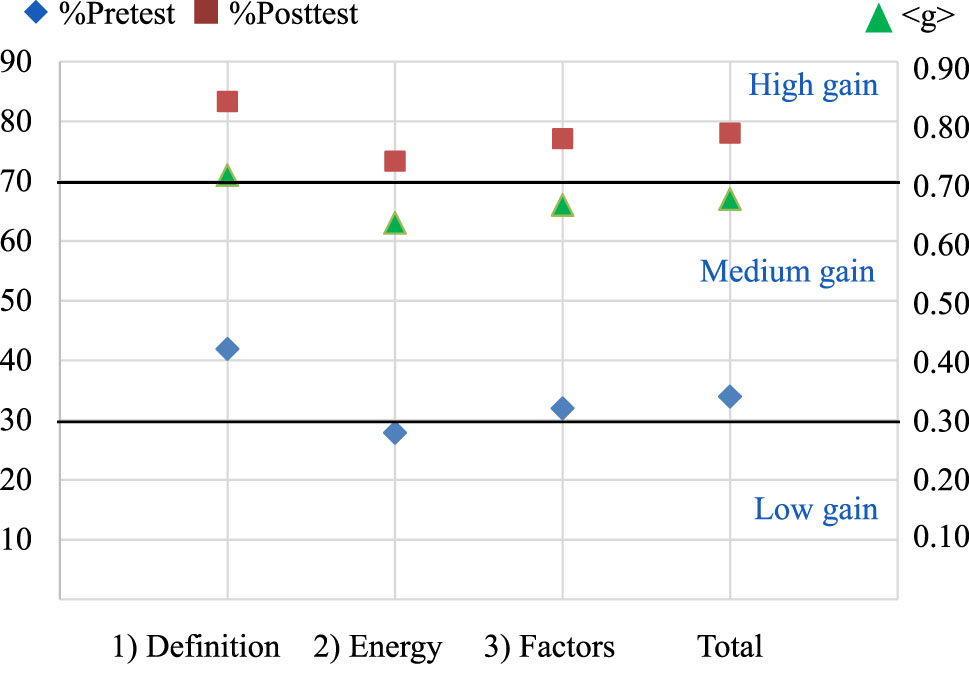

To verify the success of implementing the activity using the portable syringe kit demonstration of gas-generating reaction whereby students’ understanding of the concepts of chemical reaction rate could be improved, the volunteered participants were required to complete a conceptual test before and after experimenting, respectively called pre- and post-conceptual understanding tests. Before the undertaking of the experiment, the student’s average percentages of the pre-test scores for the concepts of the definition of reaction rate, energy, and reaction progress, factors influencing rate, and total were 41.92, 27.88, 31.99, and 33.94, respectively (see Table 4).

Conceptual understanding test scores of chemical reaction rate (n = 33).

| Concepts | Pretest | Post-test | Normalized Gain | T (T-test) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | % | mean | SD | % | <g> | Level | ||

| 1) Definition of rxn. rate (6 points) | 2.52 | 1.42 | 41.92 | 5.00 | 0.83 | 83.33 | 0.71 | High | 9.60a |

| 2) Energy and rxn. progress (5 points) | 1.39 | 1.41 | 27.88 | 3.67 | 0.96 | 73.33 | 0.63 | Medium | 15.84a |

| 3) Factors influencing rate (9 points) | 2.88 | 1.24 | 31.99 | 6.94 | 0.93 | 77.10 | 0.66 | Medium | 26.54a |

| Total (20) | 6.79 | 2.25 | 33.94 | 15.61 | 1.64 | 78.03 | 0.67 | Medium | 26.73a |

-

aDefined as statistically different at 95 % confidence level.

After the experiment, their average percentages rose to 83.33, 73.33, 77.10, and 78.03, respectively. The dependent samples t-test analysis indicated that their post-test scores were significantly higher than the pre-test at a 95 % confidence level. In addition, their normalized learning gains or <g> values fell in the medium range for energy and reaction progress (0.63), factors influencing rate (0.66), and total (0.67), and fell in the high range for the definition of reaction rate (0.71), see Figure 5. It can be seen that the students obtained a higher score percentage and normalized gain for the concept of the reaction rate than for the concepts of energy and reaction progress and factors influencing rate. This arose from the idea that the definition of reaction rate involves less complexity. In contrast, factors affecting the rate involve various elements (concentration, surface area, temperature, etc.), and each factor uniquely impacts the rate (Çalik et al., 2010).

Percentages of pre- and post-conceptual test scores (left scale) and normalized gain or <g> (right scale) of chemical reaction rate.

This showed that implementing a portable syringe kit demonstration of a gas-generating reaction effectively encouraged students to understand the reaction rate accurately. This is consistent with earlier research studies, which showed that using the corresponding chemistry experiment through an inquiry-based learning process assisted students in improving their conceptual understanding of chemical reaction rate (Çalik et al., 2010; Chairam et al., 2009; Supasorn et al., 2022).

4 Conclusions remarks

This study verified that using a syringe kit demonstration in which two large syringes and one small syringe are connected by using a 3-way connector effectively demonstrated a qualitative comparison of various gas-generating reactions. Since this kit is a closed system, it allows us to transfer liquid reactant from the small syringe to react with solid reactant in the lower large syringe and then transfer and filter gas product through water to the upper large syringe. The addition of phenolphthalein in liquid reactants allows us to indicate whether the reaction mixture or reaction product is acid or base. The exothermic or endothermic reaction can be observed by touching the lower syringe containing the reaction mixture. In addition, ignition test can be applied to test H2 (rarely visible flame) and C2H2 (very bright flame) gases, while turbidity of lime water or Ca(OH)2 solution is applied to test CO2 gas. The syringe kit, integrated within the 5E inquiry learning framework, effectively enhanced grade-11 students’ conceptual understanding of reaction rates, as evidenced by an increase in their conceptual test scores from 33.94 % to 78.03 %, with a medium normalized gain (<g = 0.67>). This experimental kit has proven to be an effective and accessible tool for upper secondary school students (du Toit & du Toit, 2025) as it addresses several limitations. It is also repeatable, easy to set up, demonstrate, and clean, safe to perform, generates minimal waste, requires little time, and allows for precise observation of changes in reaction rates.

5 Limitations

Some reactions are exothermic and may cause plastic syringes to be damaged. As a result, the amount of the limiting reagent should be carefully considered, and reactants should be gradually combined to prevent high pressure from gas products. The plunger lag of syringes using distilled water should be assessed before the demonstration. Syringes with similar lags should be selected for use in the same demonstration to ensure consistency. If the plunger becomes stiff, applying petroleum jelly can help it move more smoothly. It is recommended that all syringes and plungers be cleaned and dry after use to prevent stiffness.

6 Implications

The syringe experimental kit demonstration on chemical kinetics of gas-generating reactions could be implemented in conjunction with corresponding particulate learning activities (such as analogies, models, animations, or augmented reality (Supasorn et al., 2015)) to support upper secondary school students to enhance their conceptual understanding and conceptual changes at both macroscopic, symbolic and particulate levels (Luviani et al., 2021; Sotiriou & Bogner, 2008). Inquiry-based learning (Gialouri et al., 2011) could be used to integrate experimental kits and particulate tools. The investigation of how they develop and change their conceptual understanding will be reported in the further study.

Funding source: Thailand Research Fund

Award Identifier / Grant number: RSA590021

Acknowledgments

This study was part of the RSA590021 project, “Development of low-cost small-scale chemistry experimental kits in conjunction with inquiry-based learning activities to promote upper secondary school students’ conceptual understanding and changes at molecular level,” which was co-funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI), formerly known as Thailand Research Fund (TRF), and Ubon Ratchathani University (UBU). The PERCH-CIC is also acknowledged. The authors thank the TRF and UBU for their financial support.

-

Research ethics: Human research ethics were approved with the code number UBU-REC-07/2563 (Ubon Ratchathani University Research Ethics Committee, 2020).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Grammarly and Quillbot are used to improve language.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Thailand Research Fund (TRF)

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials consist of instructor notes, student notes, and experiment results from the investigation of CO2 volume with time.

References

Bybee, R. W. (2014). The BSCS 5E instructional model: Personal reflections and contemporary implications. Science and Children, 51(8), 10–13. https://doi.org/10.2505/4/sc14_051_08_10.Search in Google Scholar

Çalik, M., Kolomuc, A., & Karagolge, Z. (2010). The effect of conceptual change pedagogy on students’ conceptions of rate of reaction. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 19(5), 422–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-010-9208-9.Search in Google Scholar

Chairam, S., Somsook, E., & Coll, R. E. (2009). Enhancing Thai students’ learning of chemical kinetics. Research in Science & Technological Education, 27(1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635140802658933.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, R., & Overby, J. (2019). Chemistry (ISE) (13th ed.). New York, NY: Mcgraw-hill Education.Search in Google Scholar

du Toit, M. H., & du Toit, J. I. (2025). Accessible chemistry: The success of small-scale laboratory kits in South Africa. Chemistry Teacher International 7(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2022-0042 Search in Google Scholar

Gialouri, E., Uzunoglou, N., Gargalakos, M., Sotiriou, S., & Bogner, F. X. (2011). Teaching real-life science in the lab of tomorrow. Advanced Science Letters, 4(11–12), 3317–3323. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2011.2041.Search in Google Scholar

Han, Y., & Kim, Y. (2013). Enjoy chemistry experiments with syringe: Use syringes and 3-way cocks to carry out small-scale experiments. In Abstracts in 2013 International Science, Mathematics and Technology Education Conference (ISMTEC) (p. 43). IPST.Search in Google Scholar

Herr, N., & Cunningham, J. B. (1999). Hands-on chemistry activities with real-life applications: Easy-to-use labs and demonstrations for grades 8–12. Upper Saddle River, Pearson Education.Search in Google Scholar

Joswick, C., & Hulings, M. (2024). A systematic review of BSCS 5E instructional model evidence. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 22(1), 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-023-10357-y.Search in Google Scholar

Justi, R. (2003). Teaching and learning chemical kinetics. In J. K. Gilbert, O. de Jong, R. Justi, D. F. Treagust & J. H. van Driel (Eds.), Chemical education: Towards research-based practice (pp. 293–315). Springer.10.1007/0-306-47977-X_13Search in Google Scholar

Khattiyavong, P., Jarujamrus, P., Supasorn, S., & Kulsing, C. (2014). The development of small-scale and low-cost galvanic cells as a teaching tool for electrochemistry. Journal of Research Unit on Science, Technology and Environment for Learning, 5(2), 146–154.Search in Google Scholar

Luviani, S. D., Mulyani, S., & Widhiyanti, T. (2021). A review of three levels of chemical representation until 2020. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1806, 012206. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1806/1/012206.Search in Google Scholar

Michalisková, R., Haláková, Z., & Prokša, M. (2019). Concept of chemical reaction in chemistry textbooks. Chemistry Teacher International, 1(2), 20180027. https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2018-0027.Search in Google Scholar

Ng, E. M. W., Song, Z., Yau, C. D., Liew, O. W., & Ng, T. W. (2020). Safe handling of gas generating experiments using disposable plastic syringes. Journal of Chemical Education, 98(1), 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00102.Search in Google Scholar

Nilsson, T., & Niedderer, H. (2012). An analytical tool to determine undergraduate students’ use of volume and pressure when describing expansion work and technical work. Chemistry Education: Research and Practice, 13(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2rp20007d.Search in Google Scholar

Obendrauf, V. (2006). More small scale hands on experiments for easier teaching and learning. In Proceedings of the 19th international conference on chemical Education (pp. 10–21). Seoul: Korean Chemical Society.Search in Google Scholar

Poliakoff, M., & Licence, P. (2007). Sustainable technology: Green chemistry. Nature, 450(6), 810–812. https://doi.org/10.1038/450810a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Sotiriou, S., & Bogner, F. X. (2008). Visualizing the invisible: Augmented reality as an innovative science education scheme. Advanced Science Letters, 1(1), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2008.012.Search in Google Scholar

Stears, M., & Gopal, N. (2014). Exploring alternative assessment strategies in science classrooms. South African Journal of Education, 30(4), 591–604. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v30n4a390.Search in Google Scholar

Stroumpouli, C., & Tsaparlis, G. (2022). Chemistry students’ conceptual difficulties and problem solving behavior in chemical kinetics, as a component of an introductory physical chemistry course. Chemistry Teacher International, 4(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2022-0005.Search in Google Scholar

Supasorn, S., Jarujamrus, P., Chairam, S., & Amatatongchai, M. (2021). Portable syringe-vial kit of gas-generating reactions for easy demonstration of chemical reaction rate. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1806 (1), 012175. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1806/1/012175.Search in Google Scholar

Supasorn, S., & Promarak, V. (2015). Implementation of 5E inquiry incorporated with analogy learning approach to enhance conceptual understanding of chemical reaction rate for grade-11 students. Chemistry Education: Research and Practice, 16(1), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4rp00190g.Search in Google Scholar

Supasorn, S., Wuttisela, K., Moonsarn, A., Khajornklin, P., Jarujamrus, P., & Chairam, S. (2022). Grade-11 students’ conceptual understanding of chemical reaction rate from learning by using the small-scale experiments. Journal Pendidikan IPA Indonesia, 11(3), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.15294/jpii.v11i3.36535.Search in Google Scholar

Ubon Ratchathani University Research Ethics Committee. (2020). UBU-REC-07/2563 – development of low-cost small-scale chemistry experimental kits to promote high school students’ conceptual understanding of chemical reaction and chemical equilibrium. Ubon Ratchathani: Ubon Ratchathani University. Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2024-0090).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Non-formal chemistry learning: a scoping review

- Research Article

- Discussion on definition and understanding of the thermodynamic spontaneous process

- Good Practice Report

- A molecular motion-based approach to entropy and application to phase transitions and colligative properties

- Research Articles

- Interrelationship of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in a system in which a reaction takes place intending to obtain useful work in isentropic conditions–lectures adapted to sensing learners

- A role-playing tabletop game on laboratory techniques and chemical reactivity: a game-based learning approach to organic chemistry education

- Predominant strategies for integrating digital technologies in the training of future chemistry and biology teachers

- Enhancing conceptual teaching in organic chemistry through lesson study: a TSPCK-Based approach

- Enhancing chemistry understanding and attitudes through an outreach education program on circular plastic economy: a case study with Thai twelfth-grade students

- Process oriented guided inquiry learning: a possible solution to improve high school students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and attitude

- Good Practice Report

- Portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry

- Research Article

- Determination of total hardness of water sample by titration using double burette method: an economical approach

- Good Practice Reports

- Interpretation of galvanic series when teaching metal corrosion

- Synthesis of valproic acid for medicinal chemistry practical classes

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Non-formal chemistry learning: a scoping review

- Research Article

- Discussion on definition and understanding of the thermodynamic spontaneous process

- Good Practice Report

- A molecular motion-based approach to entropy and application to phase transitions and colligative properties

- Research Articles

- Interrelationship of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in a system in which a reaction takes place intending to obtain useful work in isentropic conditions–lectures adapted to sensing learners

- A role-playing tabletop game on laboratory techniques and chemical reactivity: a game-based learning approach to organic chemistry education

- Predominant strategies for integrating digital technologies in the training of future chemistry and biology teachers

- Enhancing conceptual teaching in organic chemistry through lesson study: a TSPCK-Based approach

- Enhancing chemistry understanding and attitudes through an outreach education program on circular plastic economy: a case study with Thai twelfth-grade students

- Process oriented guided inquiry learning: a possible solution to improve high school students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and attitude

- Good Practice Report

- Portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry

- Research Article

- Determination of total hardness of water sample by titration using double burette method: an economical approach

- Good Practice Reports

- Interpretation of galvanic series when teaching metal corrosion

- Synthesis of valproic acid for medicinal chemistry practical classes