Abstract

The present study, an ultrashort hybrid peptide, namely, Boc-L-Pro-5-AIA(OMe)2 was synthesized, where 5-amino isophthalic acid (5-AIA) was employed as a rigid non-coded aromatic γ-amino acid. The single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis revealed that L-Pro created a turn with ϕ, Ψ values around −65°, 150° for which a bend was generated in the molecular conformation. In the solid state, two hybrid peptide molecules are assembled in antiparallel fashion and interlocked by using two N–H⋯O hydrogen bonding interactions, resulting in a robust dimer. Interestingly, the dimers are self-assembled via N–H⋯O, O–H⋯O, C–H⋯O, π⋯π, and C–H⋯π interactions to fabricate a unique water-mediated sheet network. The classical and non-classical interactions play a crucial role in the stability of the crystal packing, which are supported by Hirshfeld surface and 2D fingerprint analysis.

1 Introduction

The formation of supramolecular structures is a common phenomenon in organic, biomolecular, and medicinal chemistry. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Various noncovalent interactions and complementarity in aggregating entities are crucial factors in spontaneous self-assembly processes that give rise to supramolecular arrangements. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 It is noteworthy that short peptide assemblies play a significant role as aggregating entities because of their numerous advantages, such as biocompatibility, small size, assembling propensity, various possible combinations, and high selectivity for specific targets. 9 , 10 , 11 Therefore, short peptide assemblies are designed and synthesized with ease to develop new smart functional biomaterials with a wide range of applications from hydrogels to drug delivery agents, biosensors, and emulsifiers for example. 12 , 13 , 14 Backbone modifications of small peptides by incorporation of organic molecular frameworks, especially by non-proteinogenic amino acid residues, is an exciting research area because of gaining resistance to enzymatic degradation and in some cases increasing the conformational stability of the peptides. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 In fact, γ-aminobutyric acids are important non-coded amino acid residues, often employed for the fabrication of supramolecular structures. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 On the other hand, L-proline is a proteogenic amino acid containing a secondary amine ring structure and traditionally exploited for introducing a turn in synthetic peptide sequences. 24 , 25 , 26 To our knowledge, self-assembly pattern of proline and aromatic γ-amino butyric acid hybrid was not investigated earlier.

In continuation of our research on peptide synthesis, 23 , 25 herein, we have designed and synthesized a chiral α, γ-hybrid peptide containing rigid non-coded aromatic amino acid 5-AIA, viz., Boc-L-Pro-5-AIA(OMe)2 (Figure 1) for the first time. The solid-state structure of the peptide is determined by the single crystal X-ray diffraction study. The conformation and supramolecular structure of this ultrashort hybrid peptide are investigated. Hirshfeld surface analysis is employed for identifying potential intermolecular contacts within the crystal structure. This comprehensive approach to structural characterization and intermolecular interaction analysis provides a deep insight into the conformation and supramolecular arrangement of the compound.

Structure of the hybrid peptide 1.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and methods

Commercially available reagents and chemicals sourced from Merck and Spectrochem were utilized to synthesize the hybrid peptide. All solvents used in the reaction were obtained commercially and used directly without additional purification steps. IR spectra were recorded on Perkin-Elmer L120-00A spectrometer (νmax in cm−1) using KBr pellet. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were registered on a Bruker NMR spectrometer (400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively) in CDCl3.

2.2 Crystal structure determination

A single crystal suitable for X-ray diffraction was loaded on a Bruker D8 QUEST diffractometer configured with PHOTON 100 detector device, and the diffraction data were collected using a monochromatic Mo-target rotating-anode X-ray source and graphite monochromator (Mo-Kα, λ = 0.71073 Å) with the ω and φ scan technique. The crystal was refined as an inversion twin. The unit cell was determined using SMART, 27 the diffraction data were integrated with Bruker SAINT System 27 and the data were corrected for absorption using SADABS. 27 The structure was solved using SHELXS 97 28 by direct method and was refined by full matrix least squares based on F2 using SHELXL-2018/3. 29 All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Most of the H atoms were included at calculated positions as riding atoms with C (sp2)–H distances of 0.95 Å and C(sp3)–H distances of 0.99 Å for CH2 units and 0.98 Å for CH3 units and others being located from respective Q picks. Some most disagreeable reflections were excluded from the refinement. ORTEP-plot and packing diagram were generated with ORTEP-3 for Windows. 30 WinGX 30 was used to prepare the material for publication. CCDC 2428616 contains Supplementary crystallographic data for this paper.

2.3 Hirshfeld surface analysis

The CRYSTAL EXPLORER 17.5 software program 31 , 32 was used to compute the Hirshfeld surfaces and the associated 2D fingerprint plots across the constituent ionic and molecular geometries. The properties such as normalized contact distance, shape index, curvedness, and fragment patch were mapped over the Hirshfeld surface and plotted with the appropriate colour scale. The 2D fingerprint plots were presented as de versus di.

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Synthesis of hybrid peptide

The t-butyloxycarbonyl and methyl ester groups were used for amino and carboxyl protections, respectively. Couplings were mediated by dicyclohexylcarbodiimide/1-hydroxybenzotriazole (DCC/HOBT). All intermediates were characterized by thin layer chromatography on silica gel and used without further purification. Final peptide was purified by column chromatography using silica gel (100–200 mesh) as the stationary phase and an ethyl acetate and petroleum ether (60:40, v/v) mixture as the eluent. The reported peptide was fully characterized by FT IR, NMR and X-ray crystallography.

Boc-L-Pro-5-AIA-(OMe) 2 (hybrid peptide), 1: Boc-L-Pro-OH (1.0 g, 4.7 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (15 ml). Free amine of 5-AIA-(OMe)2 was extracted with ethyl acetate by treating the aqueous solution of 5-AIA-(OMe)2.HCl (2.3 g, 9.3 mmol) with excess NaHCO3, and added to the reaction mixture, followed by DCC (1.4 g, 7.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 day. The precipitated dicyclohexylurea (DCU) was filtered off and the filtrate was diluted with ethyl acetate. The organic layer was washed with excess of water, 1M HCl (3 × 30 ml), 1M Na2CO3 solution (3 × 30 ml), and again with water. The solvent was then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated in vacuo, giving a light yellow solid, which was purified by column chromatography using silica gel (100–200 mesh) as the stationary phase and an ethyl acetate and petroleum ether (60:40, v/v) mixture as the eluent.

Yield: 1.7 g (72 %). Mp = 148–150 °C; IR (KBr): 3,433, 3,295, 2,981, 1,729, 1,662, 1,561, 1,423 cm−1; 1H NMR 400 MHz (CDCl3, δ ppm): 9.87 (5-AIA-NH, 1H, s); 8.32 (5-AIA-H, 3H, m); 4.51(CαH of Pro, 1H, m); 3.91 (–OCH3, 6H, s); 3.44 (Pro-H, 2H, m); 2.45 (Pro-H, 1H, m); 1.93 (Pro-H, 3H, m); 1.51 (Boc-CH3s, 9H, s); 13C NMR 100 MHz (CDCl3, δ ppm): 170.6, 165.9, 139.1, 131.2, 125.9, 125.8, 124.5, 81.2, 60.5, 52.4, 47.3, 28.4, 27.5, 24.6.

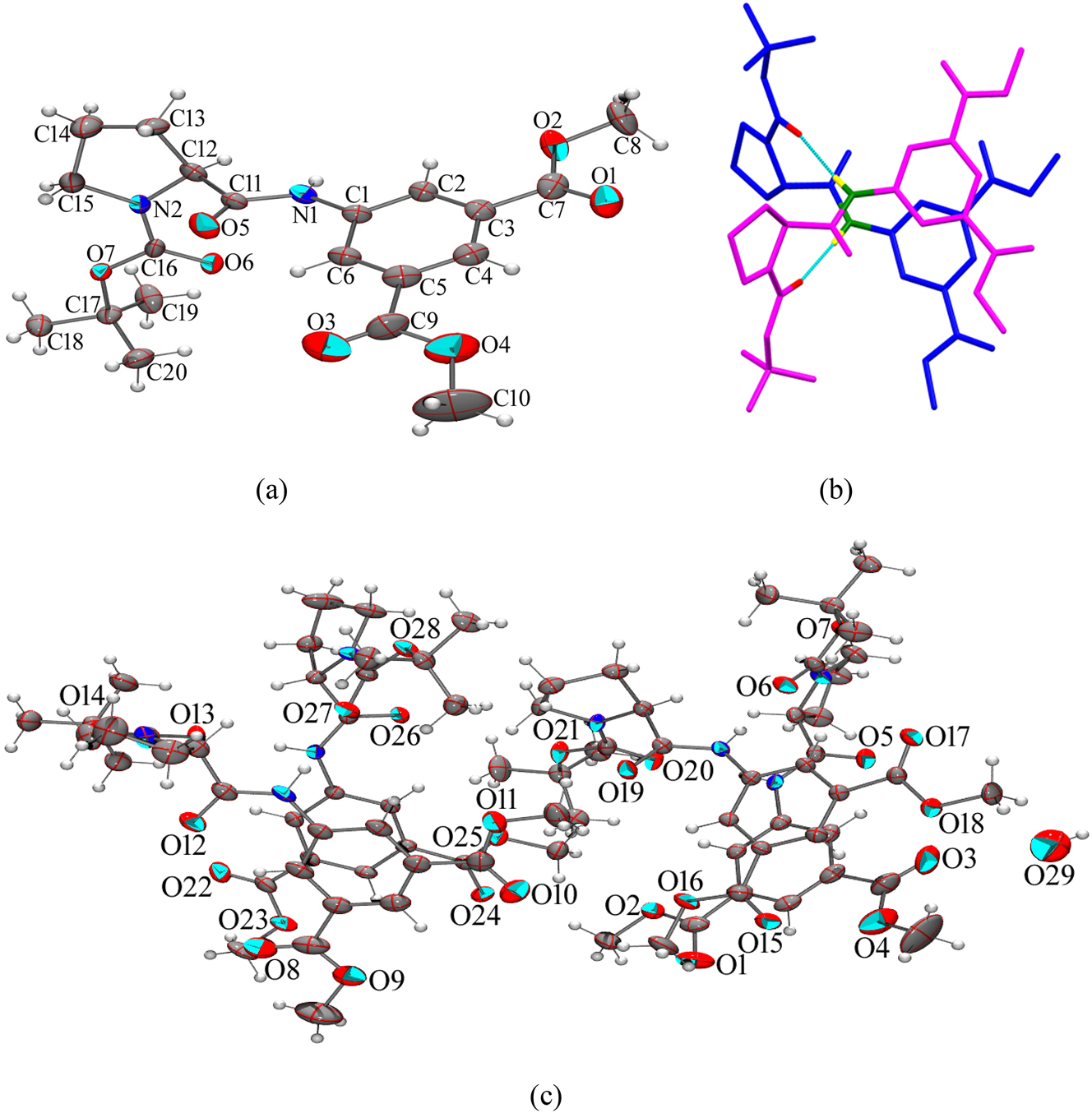

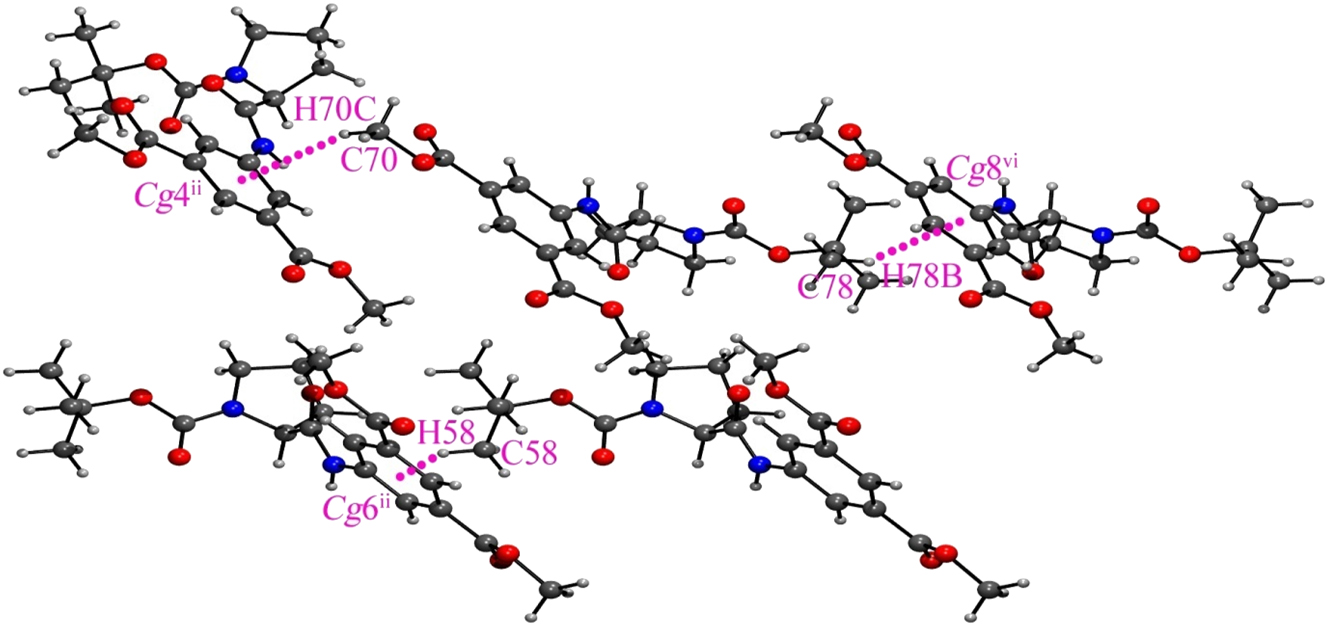

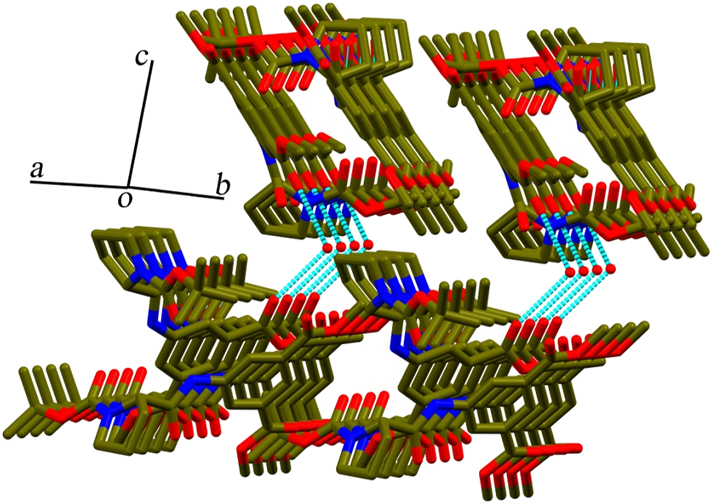

3.2 Single crystal X-ray and supramolecular assembly

The hybrid peptide 1 crystallizes by slow evaporation of its methanolic solution. The obtained colourless monoclinic crystals exhibit the space group C 2. Crystal data, data collection, and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 1. The asymmetric unit is composed of four peptide molecules and water. The L-Pro at the N-terminus generates a turn, which is evident from the backbone torsion angles in the solid state conformation (Figure 2). The molecular conformations are similar in all four molecules in the asymmetric unit, which is reflected from the backbone torsion angles with L-Pro. φ and Ψ values at L-Pro are ranging from −56.4(8)° to −78.4(6)° and 137.5(5)° to 148.3(5)° respectively (Figure 2, Table 2). L-Proline’s torsion angles are often visualized in the Ramachandran plot with φ value around −65° and Ψ clusters around 150° (β region), comparable with this hybrid peptide. Two peptide molecules are interlocked in antiparallel criss-cross fashion, through two N–H⋯O hydrogen bonding interaction, involving 5-AIA-NH⋯O=C-Βοc (N3–H3⋯O27 and N7–H7⋯O13; N1–H1⋯O20 and N5–H5⋯O6) with donor–acceptor distances ranging from 1.97 Å to 2.22 Å (Figure 2b, Table 3) forming a robust dimer. Here, proline-induced bent molecular conformation is responsible for a unique criss-cross twin formation. The dimeric assemblage is further strengthened by π−stacking in a parallel manner between the aromatic rings of 5-AIA with Cg–Cg distance 3.756(4) and 3.651(4) Å (Figure 3, Table S1). One water molecule holds two asymmetric units via hydrogen bonding with the ester carbonyl of 5-AIA (O29–H29⋯O3) with donor–acceptor distances of 2.14 Å (Table 3). In the self-assembly process, two termini of peptide molecule, i.e., Boc-CH3 at N-terminus and ester-CH3 at C-terminus are participate in C–H⋯π interaction with C–H⋯Cg distance ranging from 2.82 to 2.93 Å (Figure 4, Table S2). Moreover, many non-classical C–H⋯O interactions reinforce the supramolecular arrangement involving C–H of proline ring, aromatic ring, and Boc group with O-atom of amide carbonyl, ester group, and oxycarbonyl group (Table 3). As a result, self-assembly of the ultrashort hybrid peptide unveils a unique water-mediated supramolecular sheet architecture (Figure 5). Notably, in this supramolecular arrangement, 5-AIA plays a substantial role in π-stacking and water-mediated hydrogen bonding interaction.

Crystal data collection and structure refinement for the hybrid peptide 1.

| Crystal data | |

| CCDC reference number | 2428616 |

| Empirical formula | C160H210N16O57 |

| Moiety formula | 8(C20H26N2O7), H2O |

| Formula weight | 3,269.43 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Space group | C 2 |

| Colour, habit | Colourless |

| Size, mm | 0.19 × 0.18 × 0.16 |

| Unit cell dimensions | |

| a = 22.926(3) Å | |

| b = 9.8644(10) Å | |

| c = 38.316(4) Å | |

| β = 95.264(5)° | |

| Volume Å3 | 8,628.6(16) |

| Z | 2 |

| Density (calculated), Mg/m3 | 1.258 |

| Absorption coefficient, mm−1 | 0.096 |

| F(000) | 3,476 |

| Data collection | |

| Temperature, K | 203(2) |

| Theta range for data collection | 1.784°–24.994° |

| Index ranges | −27 ≤ h ≤ 27 |

| −11 ≤ k ≤ 11 | |

| −45 ≤ l ≤ 45 | |

| Reflections collected | 148,197 |

| Unique reflections | 15,119 |

| Observed reflections (>2σ(I)) | 10,806 |

| Rint | 0.0799 |

| Completeness to θ, % | 24.994°, 99.6 |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan (Sadabs; Sheldrick, 2000) |

| Tmin = 0.982, Tmax = 0.985 | |

| Refinement | |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 15,119/1/1,088 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.099 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0676, wR2 = 0.1296 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.1099, wR2 = 0.1486 |

| Absolute structure parameter | 0.5 |

| Extinction coefficient | 0.00179(15) |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 0.654 and −0.260 e.Å−3 |

The single crystal stucture of the hybrid peptide 1. (a) ORTEP diagram of the single molecule of 1 drawn of 30 % probability, (b) two molecules are arranged in anti-parallel criss-cross pattern (H atoms are omitted for clarity) forming a robust dimer, and (c) asymmetric unit with ellipsoid drawn of 30 % probability consist of two dimers and a water molecule.

Selected backbone torsion angles (°) at L-Pro of four hybrid peptides in the asymmetric unit of 1.

| Molecule A | Molecule B | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| C(36)-N(4)-C(32)-C(31) | −56.4(8) | C(16)-N(2)-C(12)-C(11) | −56.9(7) |

| N(4)-C(32)-C(31)-N(3) | 148.3(5) | N(2)-C(12)-C(11)-N(1) | 137.5(5) |

|

|

|||

| Molecule C | Molecule D | ||

|

|

|||

| C(56)-N(6)-C(52)-C(51) | −78.4(6) | C(76)-N(8)-C(72)-C(71) | −60.0(7) |

| N(6)-C(52)-C(51)-N(5) | 139.8(5) | N(8)-C(72)-C(71)-N(7) | 139.8(5) |

Hydrogen bonding parameters of the hybrid peptide 1.

| Bond | D–H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D–H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(1)–H(1)⋯O(20) | 0.76(5) | 2.22(6) | 2.970(7) | 174(5) |

| N(3)–H(3)⋯O(27) | 0.89(5) | 2.04(5) | 2.929(6) | 171(5) |

| N(5)–H(5)⋯O(6) | 0.83(5) | 1.99(5) | 2.821(6) | 177(4) |

| N(7)–H(7)⋯O(13) | 0.86(6) | 1.97(6) | 2.828(7) | 176(6) |

| O(29)–H(29)⋯O(3)i | 1.01 | 2.14 | 2.908(11) | 131 |

| C(6)–H(6)⋯O(5) | 0.95 | 2.25 | 2.842(8) | 119 |

| C(8)–H(8B)⋯O(15)ii | 0.98 | 2.53 | 3.405(11) | 149 |

| C(8)–H(8C)⋯O(24) | 0.98 | 2.54 | 3.334(9) | 138 |

| C(15)–H(15A)⋯O(17)iii | 0.99 | 2.48 | 3.309(8) | 141 |

| C(19)–H(19)⋯O(6) | 0.98 | 2.39 | 2.945(8) | 115 |

| C(20)–H(20A)⋯O(6) | 0.98 | 2.43 | 2.996(9) | 116 |

| C(22)–H(22)⋯O(12) | 0.95 | 2.22 | 2.838(8) | 122 |

| C(26)–H(26)⋯O(11) | 0.95 | 2.38 | 2.710(8) | 100 |

| C(28)–H(28A)⋯O(8) | 0.98 | 1.99 | 2.492(14) | 110 |

| C(34)–H(34B)⋯O(12)iv | 0.99 | 2.53 | 3.309(12) | 135 |

| C(35)–H(35A)⋯O(22)iv | 0.99 | 2.53 | 3.220(9) | 126 |

| C(38)–H(38A)⋯O(13) | 0.98 | 2.43 | 2.982(9) | 115 |

| C(39)–H(39B)⋯O(13) | 0.98 | 2.36 | 2.954(8) | 119 |

| C(42)–H(42)⋯O(19) | 0.95 | 2.35 | 2.862(7) | 113 |

| C(50)–H(50B)⋯O(17) | 0.98 | 2.24 | 2.643(8) | 103 |

| C(52)–H(52)⋯O(6) | 1.00 | 2.56 | 3.377(7) | 138 |

| C(58)–H(58A)⋯O(20) | 0.98 | 2.48 | 3.061(8) | 117 |

| C(60)–H(60C)⋯O(20) | 0.98 | 2.44 | 2.988(8) | 115 |

| C(62)–H(62)⋯O(26) | 0.95 | 2.30 | 2.853(7) | 116 |

| C(68)–H(68B)⋯O(19) | 0.98 | 2.35 | 3.324(9) | 173 |

| C(72)–H(72)⋯O(13) | 1.00 | 2.52 | 3.328(7) | 138 |

| C(75)–H(75B)⋯O(24)v | 0.99 | 2.57 | 3.226(8) | 124 |

| C(78)–H(78A)⋯O(27) | 0.98 | 2.44 | 2.976(8) | 114 |

| C(80)–H(80C)⋯O(27) | 0.98 | 2.50 | 3.035(8) | 114 |

-

Symmetry code: (i) −1/2 + x, −1/2 + y, z; (ii) x, −1 + y, z; (iii) 1/2 − x, −1/2 + y, −z; (iv) 1/2 − x, 1/2 + y, 1 − z; (v) −1/2 + x, 1/2 + y, z.

Non-classical π−π interactions (H atoms are omitted for clarity), Cg2, Cg4, Cg6 and Cg8 are the centroids of C1–C6, C21–C26, C41–C46 and C61–C66 rings respectively.

Non-classical C–H⋯π interactions, Cg4, Cg6 and Cg8 are the centroids of C21–C26, C41–C46 and C61–C66 rings respectively; Symmetry Codes: (ii) x, −1 + y, z; (vi) x, 1 + y, z.

Water-mediated supramolecular sheet arrangement of the hybrid peptide 1.

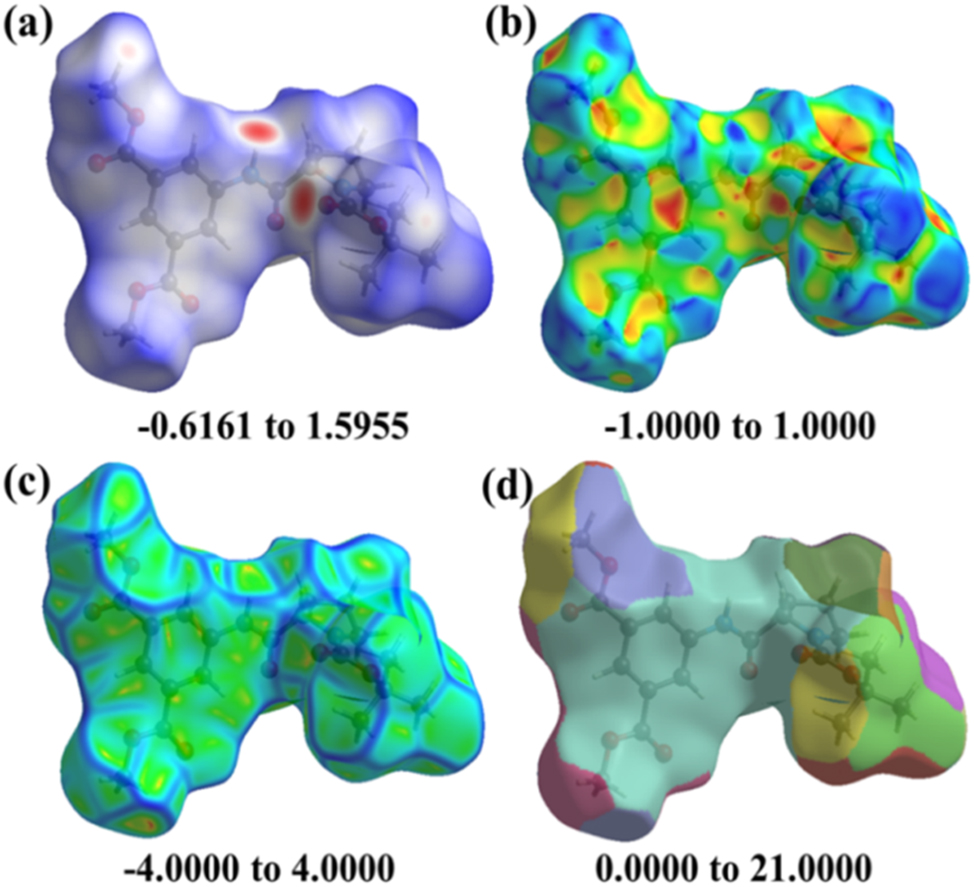

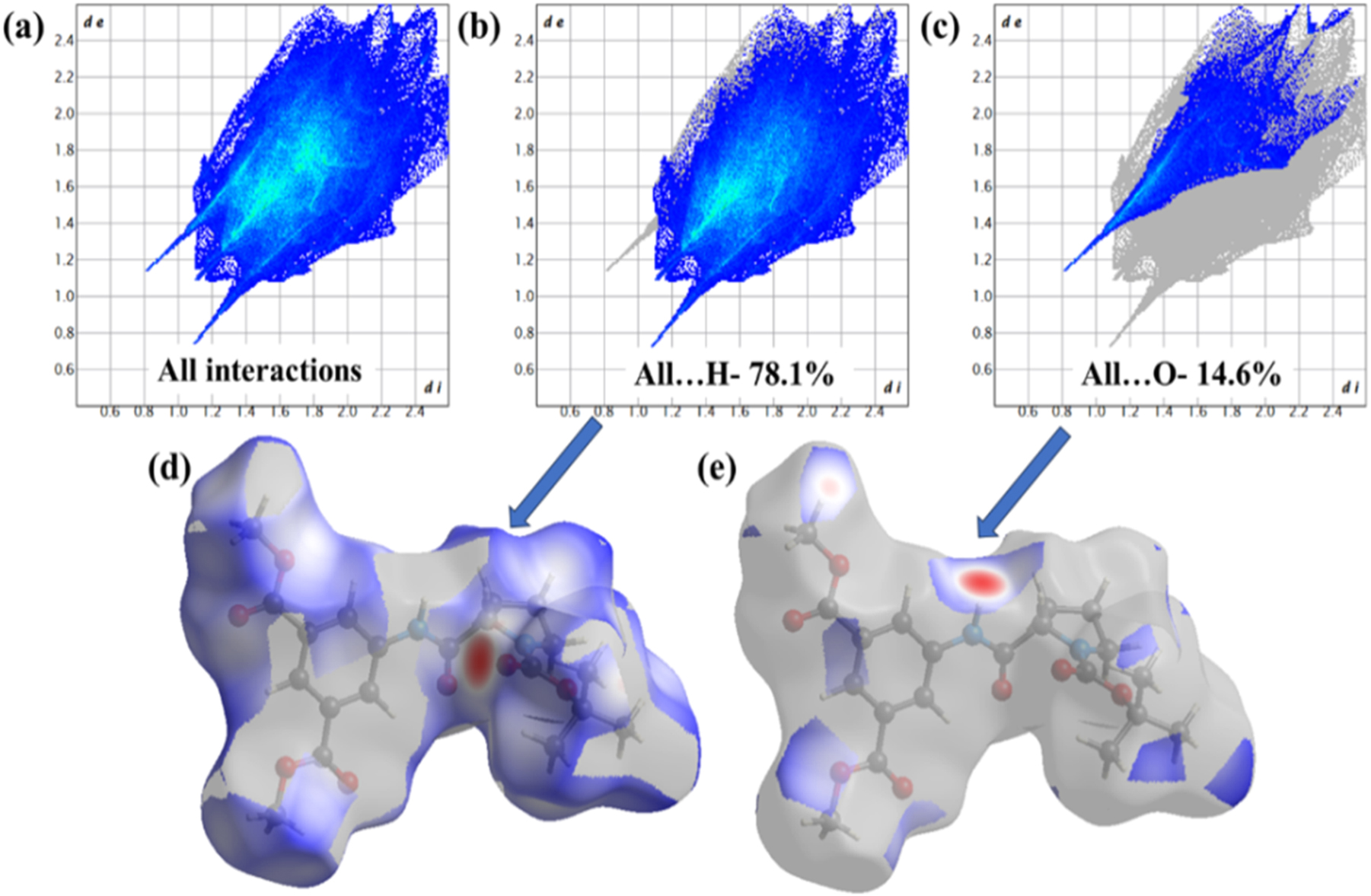

3.3 Hirshfeld surface analysis

Hirshfeld surface (HS) analysis (dnorm, shape index, curvedness, and fragment patch) was conducted to explore the weak non-covalent intermolecular interactions inside the molecule. This experiment intimates the quantitative ratios of short contacts between atoms, indicating the potential for weak hydrogen bond intermolecular interactions and their location. Colour coding was used to determine intermolecular interactions. The red, white, and blue patches in dnorm indicate intermolecular interactions with distances less than, equal to, and greater than van der Waals radii (Figure 6a). From Figure 6a, it is observed that the molecule has strong interactions, which are evident by the obvious variation in red and blue patches in the picture.

Hirshfeld surface of crystal mapped over (a) dnorm, (b) shape index, (c) curvedness, and (d) fragment patch.

Useful curvature factors like shape-index and curvedness provide further chemical insight into molecular shaping. Dark-blue borders in shape index (Figure 6b) with “bumps and hollows” belonging to blue and red, respectively, to show flatness of the surface, highlight a high degree of curvature. Large green areas that are generally flat and are bordered by dark blue margins are typically indicated by the curvedness (Figure 6c). The H-bond interaction is evident by the red spots located close to the O-atom of the carbonyl group of Boc-protection at the N-terminus and the H-atom of the amide –NH, which is also reflected in the 2D fingerprint plot (Figure 8b). In addition to hydrogen bonding interactions, HS analysis also reveal weak interactions involving phenyl rings and the aliphatic protons.

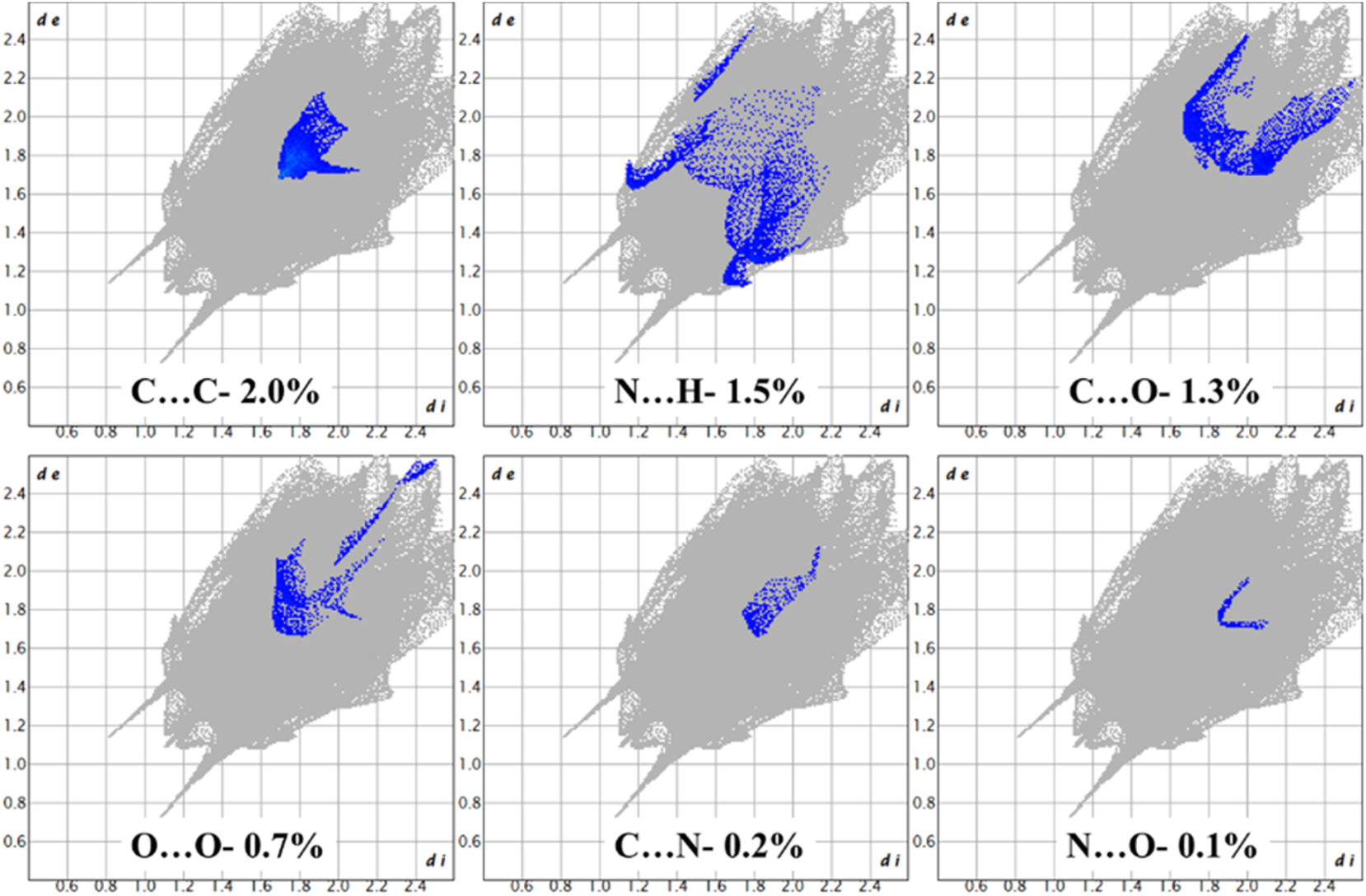

Additionally, 2D fingerprint (FP) plots were generated to emphasize the quantitative information regarding the types and nature of intermolecular interactions in the crystal packing (Figure 7). 2D FP plots were produced for each interatomic contact, as well as for all interactions. The reciprocal contact of each interatomic connection was also taken into account when calculating the individual interatomic interactions. The 2D FP plots for the hybrid peptide, displayed in Figure 7, demonstrate that H atom has the maximum interactions (78.1 %) with the other atoms outside the Hirshfeld surface, followed by the O-atom (14.6 %). Their corresponding dnorm plots are also highlighted with blue patches in Figure 7d and e.

2D fingerprint plots of the hybrid peptide 1 showing (a) all interactions, (b) H-atom interaction with all other atoms outside the Hirshfeld surface, (c) O-atom interaction with all other atoms outside the Hirshfeld surface, (d) dnorm plot for 7b, and (e) dnorm plot for 7c.

From the atom-to-atom interaction study (Figure 8), it is found that H–H interaction has the largest contribution to the total Hirshfeld surface which is account for 56.5 % in the range of de + di ≈ 2.2 Å, followed by the O–H interaction (28.0 %) in the range of de + di ≈ 1.9 Å. The dnorm plot of O–H interaction is provided in Figure 8d with blue patches. Other weak interactions are given in Figure 9.

2D fingerprint plots of the hybrid peptide 1 showing all major interactions (a) H–H interactions, (b) H–O interaction, (c) C–H interaction with all other atoms outside the Hirshfeld surface, (d) dnorm plot for 8b.

2D fingerprint plots of the hybrid peptide 1 showing weak interactions.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, we have designed, synthesised and demonstrated the conformation, self-assembly of an ultrashort hybrid peptide containing L-Pro and a rigid non-coded aromatic γ-amino acid (5-AIA). The Single crystal XRD analysis reveals that the molecule adopts a turn at proline with characteristic torsion angles and creates a bend in peptide conformation. Two peptide bends are interlocked in an anti-parallel criss-cross fashion and produce a robust dimer, which is stabilized by two N–H⋯O hydrogen bonding and π−π interactions. Each water molecule takes part in two hydrogen bonding with the ester carbonyl of 5-AIA. Moreover, plenty of C–H⋯π interactions and non-classical C–H⋯O interactions participate in the self-assembly process. As a result, the ultrashort hybrid peptide exhibits a unique water-mediated supramolecular sheet architecture by utilizing its remarkable crosslinking property. The Hirshfeld surface analysis reveals that the surfaces are influenced by H⋯H (56.5 %) and O⋯H (28.0 %) contacts for gaining the overall stability of the supramolecular structure. This study conveys a comprehensive understanding of detailed molecular conformation, molecular interactions, and self-assembly of a small hybrid peptide containing 5-AIA. This work may hold potential for understanding the correlation between small peptide sequences containing non-proteogenic γ-amino acids with their variable supramolecular arrangement.

Acknowledgments

SRD thanks CSIR, India, for providing fellowship. AD acknowledges laboratory facilities at R. B. C. Evening College, Naihati.

-

Research ethics: The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by ongoing institutional funding.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Ma, X.; Zhao, Y. Biomedical Applications of Supramolecular Systems Based on Host–Guest Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7794–7839; https://doi.org/10.1021/cr500392w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Song, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Kariuki, M.; Hall, S. C. L.; Hill, S. K.; Rho, J. Y.; Perrier, S. Molecular Self-Assembly and Supramolecular Chemistry of Cyclic Peptides. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 13936–13995; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01291.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Kim, N. H.; Choi, H.; Shahzad, Z. M.; Ki, H.; Lee, J.; Chae, H.; Kim, Y. H. Supramolecular Assembly of Protein Building Blocks: From Folding to Function. Nano Converge 2022, 9, 4; https://doi.org/10.1186/s40580-021-00294-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Lehn, J.-M. From Supramolecular Chemistry towards Constitutional Dynamic Chemistry and Adaptive Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 151–160; https://doi.org/10.1039/b616752g.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Rest, C.; Kandanellia, R.; Fernández, G. Strategies to Create Hierarchical Self-Assembled Structures via Cooperative Non-covalent Interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2543–2572; https://doi.org/10.1039/c4cs00497c.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Haque, A.; Alenezi, K. M.; Khan, M. S.; Wong, W.-Y.; Raithby, P. R. Non-Covalent Interactions (NCIs) in π-Conjugated Functional Materials: Advances and Perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 454–472; https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cs00262k.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Fyfe, M. C. T.; Stoddart, J. F. Synthetic Supramolecular Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997, 30, 393–401; https://doi.org/10.1021/ar950199y.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Philp, D.; Stoddart, J. F. Self-Assembly in Natural and Unnatural Systems. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1996, 35, 1154–1196; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199611541.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Sheehan, F.; Sementa, D.; Jain, A.; Kumar, M.; Najjaran, M. T.; Kroiss, D.; Ulijn, R. V. Peptide-Based Supramolecular Systems Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121 (22), 13869–13914; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00089.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Chang, R.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, P.; Xing, R.; Yan, X. Peptide Self-Assembly: From Ordered to Disordered. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 289–301; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.3c00592.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Levin, A.; Hakala, T. A.; Schnaider, L.; Bernardes, G. J. L.; Gazit, E.; Knowles, T. P. J. Biomimetic Peptide Self-Assembly for Functional Materials. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 615–634; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-0215-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Das, R.; Gayakvad, B.; Shinde, S. D.; Rani, J.; Jain, A.; Sahu, B. Ultrashort Peptides – A Glimpse into the Structural Modifications and Their Applications as Biomaterials. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 5474–5499; https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.0c00544.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Sun, B.; Tao, K.; Jia, Y.; Yan, X.; Zou, Q.; Gazit, E.; Li, J. Photoactive Properties of Supramolecular Assembled Short Peptides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4387–4400; https://doi.org/10.1039/c9cs00085b.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Hu, X.; Liao, M.; Gong, H.; Zhang, L.; Cox, H.; Waigh, T. A.; Lu, J. R. Recent Advances in Short Peptide Self-Assembly: From Rational Design to Novel Applications. Curr. Opin. Colloid & Interface Sci. 2020, 45, 1–13; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocis.2019.08.003.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Misra, R.; Rudnick-Glick, S.; Adler-Abramovich, L. From Folding to Assembly: Functional Supramolecular Architectures of Peptides Comprised of Non-canonical Amino Acids. Macromol. Biosci. 2021, 21, 2100090; https://doi.org/10.1002/mabi.202170020.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Sharma, K. K.; Sharma, K.; Rao, K.; Sharma, A.; Rathod, G. K.; Aaghaz, S.; Sehra, N.; Parmar, R.; VanVeller, B.; Jain, R. Unnatural Amino Acids: Strategies, Designs, and Applications in Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 19932–19965; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c00110.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Wanga, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Meng, D. Unnatural Amino Acids: Promising Implications for the Development of New Antimicrobial Peptides. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 49, 231–255; https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841x.2022.2047008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Das, A. K.; Gavel, P. K. Low Molecular Weight Self-Assembling Peptide-Based Materials for Cell Culture, Antimicrobial, Anti-Inflammatory, Wound Healing, Anticancer, Drug Delivery, Bioimaging and 3D Bioprinting Applications. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 10065–10095; https://doi.org/10.1039/d0sm01136c.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Dutta, A.; Drew, M. G. B.; Pramanik, A. Amyloid‐Like Fibrillogenesis Through Supramolecular Helix‐mediated Self‐assembly of Tetrapeptides Containing Non‐coded α‐Aminoisobutyric Acid (Aib) and 3‐Aminobenzoic Acid (m‐ABA). Helv. Chim. Acta 2010, 93, 1025–1037; https://doi.org/10.1002/hlca.200900335.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Koley, P.; Drew, M. G. B.; Pramanik, A. Salts Responsive Nanovesicles through π-Stacking Induced Self-Assembly of Backbone Modified Tripeptides. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011, 11, 6747–6756; https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2011.4219.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Maity, S. K.; Maity, S.; Jana, P.; Haldar, D. Supramolecular Double Helix from Capped γ-Peptide. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 711–713; https://doi.org/10.1039/c1cc15570a.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Dutta, A.; Drew, M. G. B.; Pramanik, A. Design of a Turn-Linker-Turn Foldamer by Incorporating Meta-Amino Benzoic Acid in the Middle of a Helix Forming Hexapeptide Sequence: A Helix Breaking Approach. J. Mol. Str. 2009, 930, 55–59; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2009.04.037.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Dutta, A.; Das, S.; Das, P. Helical Self-Assembly of an Unusual Pseudopeptide: Crystallographic Evidence. Z. Kristallogr. 2023, 238, 373–378; https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2023-0034.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Balaram, H.; Venkataram Prasad, B. V.; Balaram, P. Multiple Conformational States of a Pro-pro Peptide. Solid-State and Solution Conformations of Boc-Aib-Pro-Pro-NHMe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 4065–4071; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00350a053.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Dutta, A.; Das, S.; Das, P.; Maity, S.; Ghosh, P. Solid State Self-Assembly and Morphology of a Rigid Non-coded γ-Amino Acid Inserted Tripeptide. Z. Kristallogr. 2021, 236, 123–127; https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2021-2006.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Kar, S.; Drew, M. G. B.; Pramanik, A. Nano Structures Through Self-Assembly of Protected Hydrophobic Amino Acids: Encapsulation of Rhodamine B Dye by Proline-Based Nanovesicles. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 47, 1825; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-011-5969-7.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Bruker, Smart, Saint and Sadabs, Madison: Bruker AXS Inc., 2000.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Sheldrick, G. M. A Short History of Shelx. Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112–122; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108767307043930.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with Shelxl. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229614024218.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Farrugia, L. J. WinGX and Ortep for Windows: An Update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889812029111.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Spackman, M. A.; Jayatilaka, D. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2009, 11, 19–32; https://doi.org/10.1039/b818330a.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Spackman, M. A.; McKinnon, J. J. Fingerprinting Intermolecular Interactions in Molecular Crystals. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2002, 4, 378–392; https://doi.org/10.1039/b203191b.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2025-0022).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Gd5Rh19Sb12 − a metal-rich antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12 related structure

- Synthesis of schafarzikite-type (PbBi)(Fe1−xMn x )O4: a study on structural, spectroscopic and thermogravimetric properties

- Crystals of Racemic Mimics. Part II. Some Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds crystallizing thus, and remarks on the chirality of atoms containing non-bonded electron pairs as stereogenic centers

- The plumbides SrPdPb and SrPtPb

- In situ crystallization of the tetrahydrate of pentafluoro-benzenesulfonic acid, featuring the Eigen ion (H9O4)+

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Two novel copper(II) supramolecular complexes: synthesis, crystal structures, and Hirshfeld surface analysis

- 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

- Synthesis, crystal structure, and Hirshfeld analysis of an ultrashort hybrid peptide

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Ni3Sn4 and FeAl2 as vacancy variants of the W-type (“bcc”) structure

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Gd5Rh19Sb12 − a metal-rich antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12 related structure

- Synthesis of schafarzikite-type (PbBi)(Fe1−xMn x )O4: a study on structural, spectroscopic and thermogravimetric properties

- Crystals of Racemic Mimics. Part II. Some Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds crystallizing thus, and remarks on the chirality of atoms containing non-bonded electron pairs as stereogenic centers

- The plumbides SrPdPb and SrPtPb

- In situ crystallization of the tetrahydrate of pentafluoro-benzenesulfonic acid, featuring the Eigen ion (H9O4)+

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Two novel copper(II) supramolecular complexes: synthesis, crystal structures, and Hirshfeld surface analysis

- 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

- Synthesis, crystal structure, and Hirshfeld analysis of an ultrashort hybrid peptide

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Ni3Sn4 and FeAl2 as vacancy variants of the W-type (“bcc”) structure