6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

-

Selma Bourichi

, Khalid Boujdi

, Rachida Amanarne

, Younes Ouzidan

, Youssef Kandri Rodi

, Fouad Ouazzani Chahdi

, Sang Loon Tan

und Edward R. T. Tiekink

Abstract

Two regioisomers obtained from the same reaction and differing in the position of an n-butyl substituent, i.e. on either an imidazoyl-N (2) or a pyridyl-N (3), have been characterised. Different electronic structures are evident, especially in key bond lengths and angles in the imidazoyl and pyridyl rings, as discerned by X-ray crystallography, and by geometry-optimisation, natural bonding orbital and electrostatic potential charge calculations. The distinctive molecular packing in their crystals has been confirmed by Hirshfeld surface analysis as well as by interaction energy and energy framework calculations. These differences notwithstanding, the calculated lattice energies indicate very similar stabilisation between the molecules in their crystals, i.e. −101.3 and −103.5 kJ/mol for 2 and 3, respectively, consistent with their similar calculated molecular volumes (376.8 cf. 374.1 Å3), packing coefficients (69.0 cf. 69.5 %) and crystal densities (1.575 cf. 1.586 g/cm3).

1 Introduction

Imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivatives are a versatile class of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds which constitute intermediates widely used in organic synthesis, medicinal chemistry and materials chemistry. 1 , 2 Compounds containing an imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine moiety have been evaluated as anti-cancer, 3 , 4 , 5 anti-inflammatory, 6 anti-viral 7 and anti-mycobacterial agents, 8 and as GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators. 9 Furthermore, certain derivatives are known as aromatase inhibitors, 10 proton pump inhibitors 11 and DNA/RNA intercalators. 12 In addition, (2-(4-(6-chloro-2-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridin-7-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-N-(thiazol-2-yl)acetamide) is a potent inhibitor of Aurora-A, Aurora-B and Aurora-C kinases, 13 see Figure 1(a) for the chemical diagram. Also, and due to the presence of nitrogen atoms in this moiety, some imidazopyridine derivatives have been reported to be corrosion inhibitors for steel in acidic medium. 14 , 15

![Figure 1:

Chemical diagrams for potential drugs constructed about the imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine scaffold: (a) (2-(4-(6-chloro-2-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridin-7-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-N-(thiazol-2-yl)acetamide), (b) Tenatoprazole (5-methoxy-2-[(4-methoxy-3,5-dimethylpyridin-2-yl)methylsulfinyl]-1H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine) and (c) Telcagepant (N-[(3R,6S)-6-(2,3-difluorophenyl)-2-oxo-1-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)azepan-3-yl]-4-(2-oxo-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridin-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxamide).](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2024-0120/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2024-0120_fig_001.jpg)

Chemical diagrams for potential drugs constructed about the imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine scaffold: (a) (2-(4-(6-chloro-2-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridin-7-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-N-(thiazol-2-yl)acetamide), (b) Tenatoprazole (5-methoxy-2-[(4-methoxy-3,5-dimethylpyridin-2-yl)methylsulfinyl]-1H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine) and (c) Telcagepant (N-[(3R,6S)-6-(2,3-difluorophenyl)-2-oxo-1-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)azepan-3-yl]-4-(2-oxo-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridin-1-yl)piperidine-1-carboxamide).

The above interest has led to many investigations on imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivatives which have resulted in drug candidates undergoing clinical trials such as Tenatoprazole, an imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine-based proton pump inhibitor, 16 Figure 1(b). Likewise, Telcagepant, has been investigated for the treatment of migraine, 17 Figure 1(c), being an antagonist of the receptor for calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). 18

Due to their applications, the development of new imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine-based derivatives is clearly of interest and deserving of on-going attention. With the above in mind, N-alkylation reactions of imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine are important and can lead to the development of efficient methods for the synthesis of new imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivatives. In continuation of on-going work devoted to the preparation of new imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivatives, 19 , 20 , 21 herein is reported the synthesis and characterisation of two N-substituted imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivatives, arising from the action of 1-bromobutane upon 6-bromo-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine, 22 1, under phase transfer catalytic (PTC) conditions, Scheme 1. The reaction leads to the formation of two regioisomeric products, 2 and 3, isolated in 66 and 24 % yields, respectively, whose structures have been elucidated by spectroscopic data and detailed by X-ray crystallography. The molecular structures of 2 and 3, and their packing in their respective crystals were also studied by a range computational chemistry techniques.

![Scheme 1:

Condensation products 2 and 3 isolated from the reaction of 6-bromo-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (1) with 1-bromobutane under PTC conditions.](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2024-0120/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2024-0120_scheme_001.jpg)

Condensation products 2 and 3 isolated from the reaction of 6-bromo-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (1) with 1-bromobutane under PTC conditions.

2 Materials and methods

All chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and used without further purification. The melting points were determined on an Electrothermal 9100 apparatus. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were measured in the range of 450–4,000 cm−1 on a Perkin Elmer Spectrum two FT-IR spectrophotometer. Column chromatography and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) were performed using silica gel and silica plates, respectively. The characterisation of 2 and 3 was performed by NMR spectroscopy on a Bruker Avance NEO 400 MHz spectrometer with CDCl3 as solvent; two-dimensional COSY and HSQC experiments were also conducted to aid the assignment of all resonances. Abbreviations: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; m, multiplet. The device used for HPLC/MS (positive mode) analyses was an Ultimate 3000 coupled to the Thermo Scientific brand Exactive Plus mass spectrometer. FTIR (Figures S1 and S2), NMR (Figures S3–S10) and HPLC/MS (Figures S11 and S12) spectra are included in the Supplementary materials.

2.1 Synthesis

2.1.1 Synthesis of 6-bromo-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (1)

To 5-bromo-2,3-diaminopyridine (1 g, 5.31 mmol) dissolved in ethanol (30 mL) was added 4-chlorobenzaldehyde (0.75 g, 5.31 mmol). The mixture was stirred under reflux for 24 h. The brown solid that formed was filtered, washed three times with distilled water and dried in an oven. 22

2.1.2 Synthesis of 2 and 3

To a dimethylformamide (25 mL) solution of 6-bromo-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (0.2 g, 0.65 mmol) was added potassium carbonate (0.13 g, 0.92 mmol), tetra-n-butylammonium bromide (TBAB, 0.032 g, 0.1 mmol) and 1-bromobutane (0.077 mL, 0.78 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. After removing KBr by filtration, the dimethylformamide was evaporated under reduced pressure and the obtained residue was dissolved in dichloromethane. Any remaining KBr was extracted with distilled water and the resulting mixture was subjected to chromatography on a silica-gel column (eluent: ethyl acetate/hexane, 1:3) leading to clean separation as the Rf values for 2 and 3 of 0.65 and 0.23, respectively, were distinct; the Rf for 1 was 0.39. Crystals of 2 and 3 were obtained by the slow evaporation of their respective ethanol solutions.

2.1.2.1 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (2)

Yield = 66 % (0.16 g); m. pt = 118–120 °C. FTIR (υ, cm−1): 3,047 (νC–H aromatic), 2,969 and 2,887 (νC–H, Csp3), 1,619 (νC=C aromatic), 1,459 (δC–H, Csp3), 834 and 729 (out-of-plane C–H bending vibrations). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.45 (s, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H, HAr), 7.57 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H, HAr), 4.36 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Nimidazo-CH2), 1.92–1.72 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.34–1.18 (m, 2H, CH2), 0.87 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.0 (C7q), 149.7 (C1q), 142.6 (C13q), 140.0 (CHAr), 125.6 (C2q), 125.6 (C10q), 125.1 (2CHAr), 124.8 (2CHAr), 123.7 (CHAr), 109.4 (Cq-Br), 38.9 (CH2), 27.0 (CH2), 15.1 (CH2), 8.7 (CH3). HRMS (ESI +) (m/z): [M + H]+ – Calcd. for C16H15BrClN3 365.01957 found: 365.01776.

2.1.2.2 6-Bromo-4-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-4H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (3)

Yield = 24 % (0.06 g). m. pt = 140–142 °C. FTIR (υ, cm−1): 3,041 (νC–H aromatic), 2,960 and 2,944 (νC–H, Csp3), 1,610 (νC=C aromatic), 1,451 (δC–H, Csp3), 859 and 758 (out-of-plane C–H bending vibrations). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.41 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 4.67 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.04–2.11 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.41–1.50 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.02 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 148.8 (C7q), 148.5 (C1q), 147.0 (C2q), 141.8 (C13q), 131.6 (C10q), 127.7 (2CHAr), 124.9 (2CHAr), 124.5 (CHAr), 124.0 (CHAr), 101.3 (Cq-Br), 49.3 (CH2), 27.0 (CH2), 15.1 (CH2), 8.8 (CH3). HRMS (ESI +) (m/z): [M + H]+ – Calcd. for C16H15BrClN3 365.01957 found: 365.01797.

2.2 X-ray crystal structure determination

Intensity data for colourless crystals of 2 and 3 were measured at 100 K on a Rigaku/Oxford Diffraction XtaLAB Synergy diffractometer (Dualflex, AtlasS2) fitted with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å) so that θfull = 67.1 and 67.0°, respectively. Data reduction and Gaussian absorption corrections were by standard methods. 23 The structures were solved by direct methods 24 and refined on F 25 with anisotropic displacement parameters and with C-bound H atoms included in the riding model approximation. A weighting scheme of the form w = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (aP)2 + bP] where P = ((Fo2 + 2Fc2)/3) was introduced in each case. The molecular structure diagrams, showing 70 % probability displacement ellipsoids, were generated by ORTEP for Windows 26 and the packing diagrams employed DIAMOND. 27 Additional data analysis was made with PLATON. 28 Crystal and refinement data are presented in Table 1.

Crystal data, data collection and refinement details for 2 and 3.

| Compound | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Formula | C16H15BrClN3 | C16H15BrClN3 |

| Formula weight | 364.67 | 364.67 |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.02 × 0.06 × 0.20 | 0.04 × 0.05 × 0.09 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/c | P21/c |

| a (Å) | 14.00476(14) | 14.13929(12) |

| b (Å) | 4.61023(4) | 8.70873(7) |

| c (Å) | 24.4561(3) | 12.89474(12) |

| β (°) | 103.0985(11) | 105.8919(9) |

| V (Å3) | 1,537.93(3) | 1,527.11(2) |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| Density (g cm−3) | 1.575 | 1.586 |

| μ (mm−1) | 5.204 | 5.241 |

| F(000) | 736 | 736 |

| Reflections: | ||

| Collected | 23,565 | 19,167 |

| Unique | 2,731 | 2,727 |

| With I > 2σ(I) | 2,576 | 2,587 |

| θmax (°) | ||

| (100 % completeness) | 67.1 | 67.0 |

| R(F) [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.019 | 0.019 |

| a, b in weighting scheme | 0.024, 0.658 | 0.022, 1.002 |

| wR(F2) [all data] | 0.048 | 0.049 |

| Max/min Δρ (e·Å−3) | 0.30/−0.27 | 0.25/−0.33 |

| CCDC deposition number | 2215118 | 2215119 |

2.3 Computational chemistry

The initial molecular structures were obtained in the gas-phase by the ab initio Hartree–Fock model 29 with the 3-21G basis set 30 followed by optimisation using the hybrid B3LYP density functional 31 with Ahlrichs’s valence triple-zeta polarisation basis set augmented with the Def2TZVPP diffuse function, 32 , 33 available in Gaussian16. 34 The frequency validation of the local minimum structures, natural bond order (NBO) analysis 35 , 36 as well as molecular electrostatic mapping (MEP) were performed using the same density functional theory (DFT) model and basis set, with the results processed and visualised in GaussView6. 37 The combined Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) analysis and Non-Covalent Interaction (NCI) mapping were performed based on the reduced density gradient approach 38 using the wavefunction files obtained from the previous step in Gaussian16. 34 The analysis was conducted through Multiwfn 39 and the results were visualised using the VMD program. 40 The Hirshfeld surface analysis was performed using CrystalExplorer17 41 based on the methods reported in the literature, 42 with all X–H bond lengths being adjusted to their neutron-derived values prior to the calculations. 43 The interaction energies, energy frameworks and crystal lattice energies were calculated using the dispersion corrected CE-B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) model, 44 also available in CrystalExplorer17. 41

3 Results and discussion

The colourless regioisomeric compounds 2 and 3 were synthesised as outlined in Scheme 1; 2 was the major isolated product, i.e. 66 % yield cf. 24 % for 3. The 1H NMR spectra of the two compounds show triplets corresponding to the protons of the CH3 groups at 0.89 and 1.03 ppm for compounds 2 and 3, respectively. The spectra, including those for COSY and HSQC experiments, enabled unambiguous assignment of resonances as detailed in the Experimental section. The most distinctive features of the obtained spectra include the presence of a triplet centred at 4.36 and 4.67 ppm, corresponding to the NCH2 protons of 2 and 3, respectively. It is noted the resonances due to the protons adjacent to the pyridyl-N atoms of 2 and 3 occur at 8.18 and 8.21 ppm respectively, with the small downfield shift ascribed to the +I (inductive) effect of the n-butyl group in 3. Also notable are the resonances due to the methyl protons occurring at 0.87 and 1.02 ppm, respectively. This is also reflected in the 13C NMR spectra which show the presence of signals corresponding to the CH3 group resonating at 8.7 and 8.8 ppm for 2 and 3, respectively.

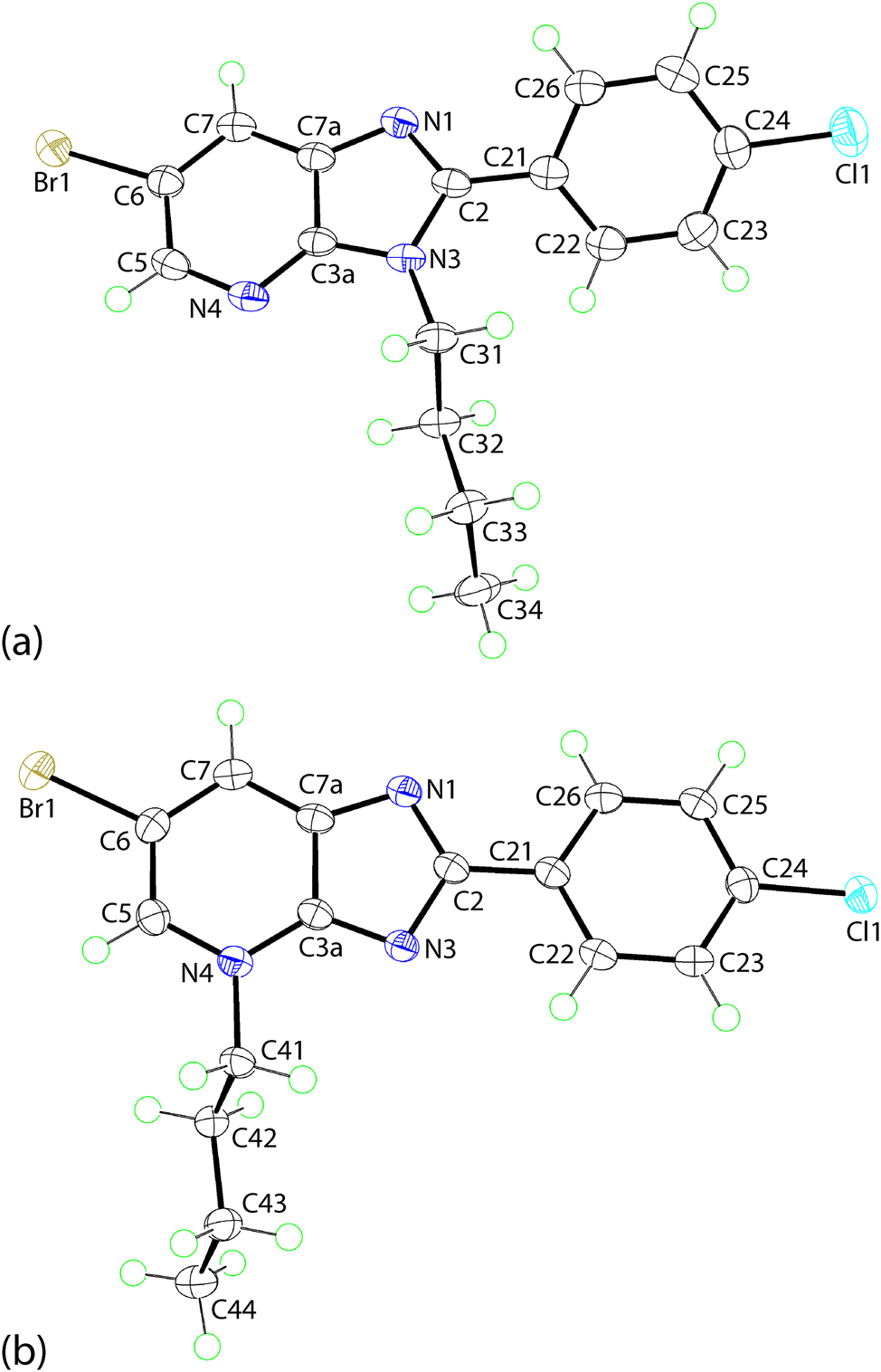

3.1 Molecular structures

The molecular structures of 2 and 3 have been established by X-ray crystallography and are represented in Figure 2 with selected geometric parameters collated in Table 2; a more exhaustive comparison of geometric data is presented in Supplementary materials Table S1. The molecule of 2 comprises a nine-membered fused ring system with the r.m.s. deviation for the fitted atoms being 0.0129 Å; the maximum deviation from the least-squares plane is 0.0206(9) Å for the N1 atom. Attached at the C2 atom is a 4-chlorophenyl ring which is inclined towards the central plane, forming a dihedral angle of 38.60(5)°. The N3 atom of the imidazoyl ring carries an n-butyl substituent which is approximately orthogonal to the fused-ring system, as seen in the C3a–N3–C31–C32 torsion angle of 79.22(17)°. The chain adopts an all-trans conformation with the N3–C31–C32–C33 and C31–C32–C33–C34 torsion angles being −176.18(12) and −175.32(13)°, respectively.

The molecular structures of regioisomeric (a) 2 and (b) 3 showing atom labelling schemes and 70 % anisotropic displacement parameters.

Selected geometric parameters (Å, °) for the experimental structures of 2 and 3, and the geometry-optimised structures for 2 and 3, i.e. opt-2 and opt-3, respectively.a

| Parameter | 2 | Opt-2 | 3 | Opt-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1–C2 | 1.323(2) | 1.319 | 1.346(2) | 1.341 |

| N1–C7a | 1.379(2) | 1.370 | 1.367(2) | 1.355 |

| N3–C2 | 1.383(2) | 1.387 | 1.375(2) | 1.376 |

| N3–C3a | 1.377(2) | 1.379 | 1.333(2) | 1.322 |

| N4–C3a | 1.331(2) | 1.323 | 1.355(2) | 1.354 |

| N4–C5 | 1.339(2) | 1.333 | 1.357(2) | 1.361 |

| N1–C2–N3 | 113.4(1) | 112.9 | 117.5(1) | 116.6 |

| N3–C2–C21 | 123.7(1) | 125.2 | 119.2(1) | 121.1 |

| N4–C3a–N3 | 126.2(1) | 127.2 | 127.5(1) | 128.4 |

| C2–N3–C3a | 105.6(1) | 105.7 | 101.2(1) | 101.9 |

| C3a–N4–C5 | 113.9(1) | 114.8 | 119.3(1) | 119.1 |

| C7a–N1–C2 | 104.9(1) | 105.5 | 102.6(1) | 103.5 |

| N1–C2–C21–C22 | −141.0(2) | −145.5 | 175.2(1) | 179.9 |

| N1–C2–C21–C26 | 36.9(2) | 32.0 | −4.5(2) | −0.1 |

| N3–C2–C21–C22 | 37.9(2) | 35.7 | −4.4(2) | −0.1 |

| N3–C2–C21–C26 | −144.3(1) | −146.9 | 175.8(1) | 179.9 |

-

aThe correlation coefficients for all bond lengths between 2 and opt-2, as well as between 3 and opt-3 is the same at 0.999, while the correlation coefficients for all angles between 2 and opt-2 as well as between 3 and opt-3 is the same at 0.994.

The molecular structure of 3 resembles that of regioisomeric 2 with the key difference being the relocation of the n-butyl substituent from the N3-position to the N4-site, Figure 2(b). The r.m.s. deviation of the nine-fitted atoms of the fused-ring system is 0.0075 Å, and the maximum deviation from the plane is exhibited by the N1 atom, i.e. 0.0116(10) Å. By contrast to 2, the pendent 4-chlorophenyl ring in 3 is almost co-planar with the fused-ring system forming a dihedral angle of 4.01(7)°, an observation related to the reduced steric hindrance at the now unsubstituted N3 atom. The orientation and conformation of the n-butyl group in 3 resembles that in 2, Table 2.

There are systematic and experimentally significant variations apparent in the key geometric parameters characterising the regioisomers consistent with the repositioning of the n-butyl group. Particularly notable within the five-membered ring of 2, is the relatively short N3–C3a bond length compared with the equivalent bond in 3, and conversely for the six-membered ring, the relatively long bond for N4–C3a in 2 cf. 3. Further, more acute angles are subtended at the N3 atom in 2 and at the N4 atom in 3, consistent with the relatively greater localisation of π-electron density at these sites, respectively.

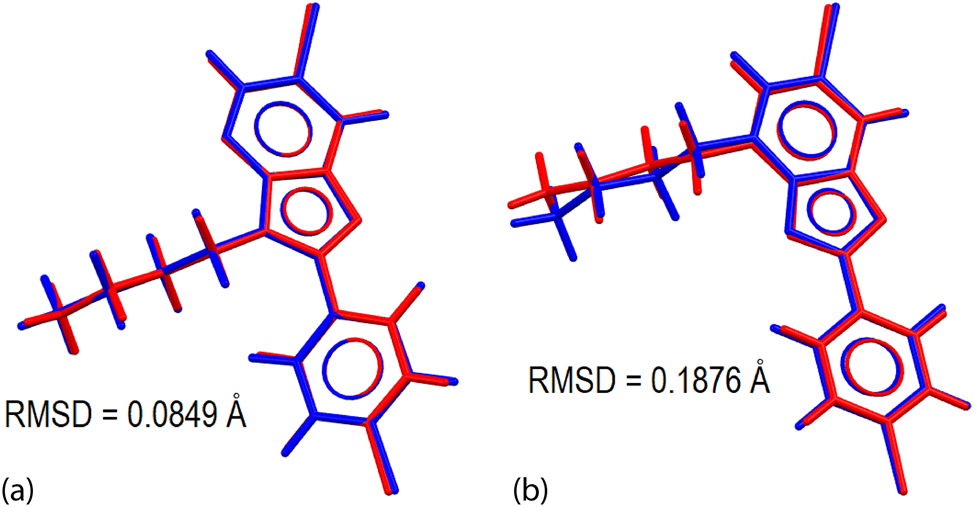

The regioisomers were subjected to geometry-optimisation calculations to compare the experimental conformations with those calculated in the gas-phase, and to derive electronic properties useful for the correlation with the packing behaviour in the crystals; the energy-converged coordinates are listed in Supplementary materials Tables S2 and S3. The optimisation leads to a pair of local minima conformations as validated through the vibrational analysis confirming the absence of an imaginary frequency in each case. The derived geometric data are also presented in Table 2; a more complete listing is included in Supplementary materials Table S1. A comparison between the respective pairs of molecules, i.e. 2 & opt-2 and 3 & opt-3 shows that the data for the optimised structures closely resemble those of their experimental counterparts but with the differences in the pairs of N3–C3a and N4–C3a bond lengths slightly accentuated. The concordance between the molecular conformations is highlighted in Figure 3, generally being very closely overlapped with the main difference noted for the n-butyl groups in 3 and opt-3, as highlighted in the C42–C41–N4–C3a torsion angles which differ by about 23° versus the typical range of 2–5° for the other torsion angles. Accordingly, the r.m.s. deviation calculated for the overlay of 2 with opt-2, i.e. 0.0849 Å, is rather less than 0.1876 Å for the analogous comparison between 3 and opt-3.

Molecular overlay diagrams between the experimental (red) and optimised structures (blue) for (a) 2 and opt-2, and (b) 3 and opt-3.

3.2 Calculation of electronic properties

The theoretical, gas-phase structures were subjected to electronic properties calculations, namely NBO and electrostatic potential charge calculations (ESP). The NBO analysis on the hybridised bonding orbitals of opt-2 and opt-3 reveals differences in the aromatic character of the imidazole rings because of the variation in the position of the n-butyl substituent. As shown in Table 3, almost all the hybridised orbitals in the five-membered ring of opt-2 exhibit a bonding character that is close to sp2-hybridisation. The notable exceptions are for the C2 and C3a atoms which display compositions consistent with some sp3 character. A similar observation is noted for the C3a–C7a bond of opt-3 with s- and p-orbital compositions of 28.8 and 71.1 %, respectively. Such deviations are not generally noted for the other atoms comprising the pyridyl rings of opt-2 and opt-3; see Supplementary materials Table S4. The above observations indicate that electron density is withdrawn from the imidazole ring of opt-2 by the n-butyl group, cf. opt-3. This effect is also reflected by the generally longer C7a–N1, C2–N3 and C3a–N3 bond lengths in opt-2 cf. opt-3, which is partially compensated by the concomitant shortening of the C1–N1 bond, Table 2.

The hybrid composition of selected natural bonding orbitals for opt-2 and opt-3.

| X⋯Y | Opt-2 | Opt-3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall occupancy (%) | s (%) | p (%) | Overall occupancy (%) | s (%) | p (%) | ||

| C2–N1 | N1 | 56.9 | 33.5 | 65.8 | 57.7 | 32.8 | 66.6 |

| C2 | 43.1 | 33.7 | 66.2 | 42.4 | 33.2 | 66.8 | |

| C7a–N1 | N1 | 56.4 | 30.7 | 68.8 | 55.9 | 31.2 | 68.2 |

| C7a | 43.6 | 31.9 | 68.7 | 44.1 | 32.9 | 67.0 | |

| C2–N3 | N3 | 61.9 | 33.3 | 66.5 | 58.2 | 30.7 | 68.7 |

| C2 | 38.1 | 29.9 | 70.1 | 41.8 | 31.8 | 68.2 | |

| C3a–N3 | N3 | 61.2 | 31.7 | 68.1 | 56.1 | 32.4 | 66.9 |

| C3a | 38.8 | 29.2 | 70.7 | 43.9 | 34.9 | 65.0 | |

| C3a–C7a | C3a | 50.6 | 35.0 | 64.9 | 51.0 | 33.5 | 66.4 |

| C7a | 49.4 | 30.3 | 69.5 | 49.0 | 28.8 | 71.1 | |

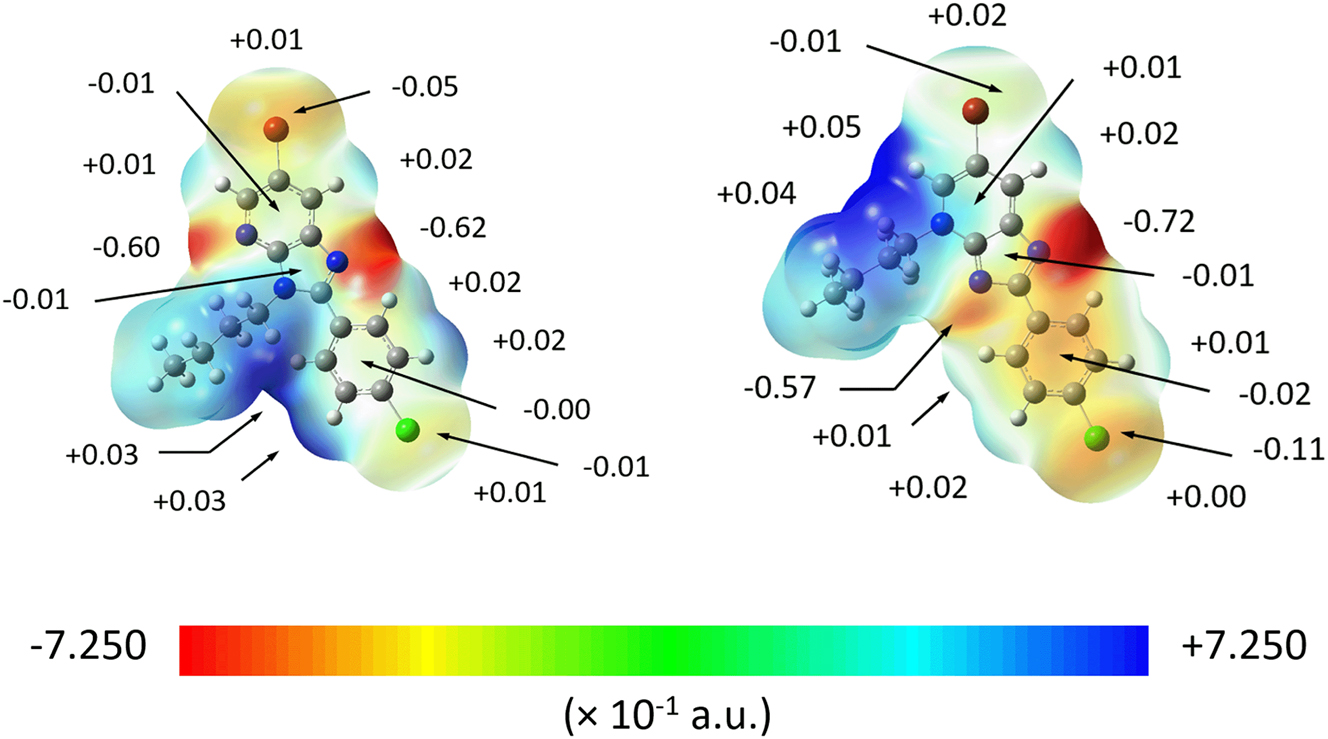

Owing to the relatively good accuracy and reduced sensitivity towards the choice of basis set, 45 the Merz-Singh-Kollman electrostatic potential fitting method 46 was employed by scaling the radii by a factor of 1.4–2.0 to estimate the electrostatic potential charges for the regioisomers. The electron distributions are significantly affected by the position of the n-butyl group in each regioisomer. Thus, the electronic charges about the respective substituted-N3 and N4 atoms in opt-2 and opt-3, is dispersed over the adjacent n-butyl-carbon atoms thereby influencing the charges about the atoms comprising the imidazolyl and pyridyl rings they are attached to. Specifically, for opt-2, the negative charges on the N1, and substituted-N3 and N4 atoms are −0.62, −0.17 and −0.60 a.u., while C2 carries positive potential (+0.37 a.u.); see Supplementary materials Table S5 for a listing of all charges. In opt-3, the charges on the N1 and N3 atoms become more negative cf. opt-2, i.e. −0.72 and −0.57 a.u., while the charge on the substituted-N4 atom is now positive (+0.13 a.u.); the positive charge on atom C2 becomes more positive (+0.70 a.u.).

The influence of n-butyl substituent is also apparent on the charges on adjacent atoms. Thus, the unsubstituted-N4 atom in opt-2 withdraws negative charge from adjacent atoms in the pyridyl ring so C3a and C5 exhibit positive charge values of +0.50 and +0.41 a.u., respectively. With the relocation of the n-butyl group to give opt-3, the negative charges of the N4 and Br1 atom delocalise over the pyridyl ring resulting in a positive charge for N4 with a reduced negative charge for Br1 (−0.01 cf. −0.05 a.u. for opt-2). As for the phenyl group, there are some discrepancies between the equivalent atoms in the aromatic rings whereby alternate positive-negative charges are observed within the aromatic ring of opt-2 with Cl1 having a negative charge of −0.01 a.u. By contrast, a random distribution of charges is seen in opt-3 with a slight increase in negative potential for Cl1 (−0.11 a.u.). A plausible reason for this difference is the proximity of the n-butyl in opt-2 to the phenyl ring causing the ring to be tilted so that charge induction between the n-butyl group and the electron cloud of the aromatic ring occurs. As indicated above, the phenyl ring in opt-3 is close to co-planar with the imidazoyl ring incurring little or no influence from the n-butyl group located in the N4-position.

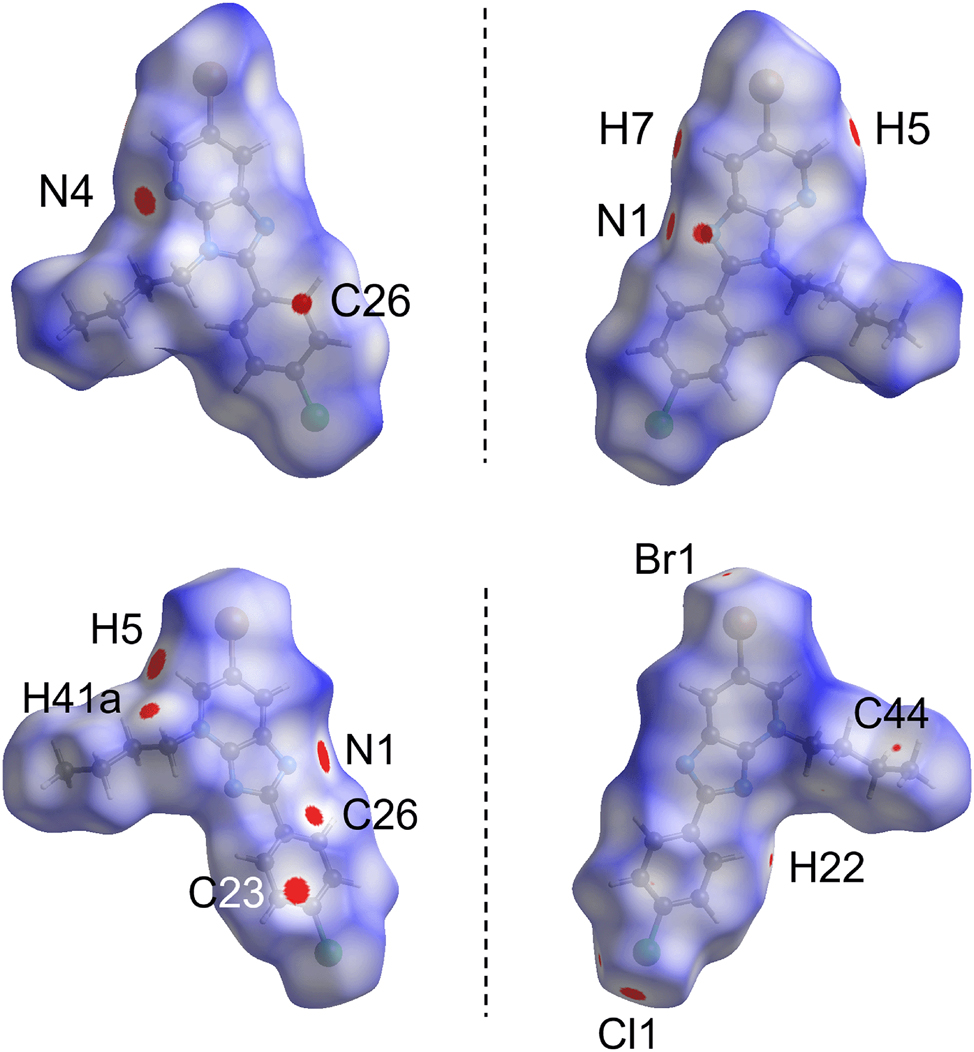

The translation of the ESP fitted charges into graphical molecular electrostatic mapping (MEP) results in a clearer visualisation of the electronic properties for opt-2 and opt-3, as illustrated in Figure 4. Apart from those atomic sites with strong electrostatic negative or positive potential as indicated by red or blue regions, some additional information was obtained through the MEP mapping which was not immediately apparent in the charge fitting approach. For instance, weakly positive electrostatic potential resides at the σ-holes of the Br1 and Cl1 atoms of each molecule and the sides of their mapped surfaces have negative potential. The σ-hole of Br1 in opt-3 is slightly more positive than its counterpart in opt-2 owing to the reduced electron density upon charge distribution towards the n-butyl group. A similar observation is also noted for the σ-hole of the Cl1 sites even though the difference in the positive potentials is not as great as for the Br1 atoms. The alternate positive-negative charge distribution for the phenyl group in opt-2, as mentioned earlier, results in an almost zero electrostatic potential at the centre of the aromatic ring in contrast to that of −0.02 a.u. for opt-3. The centre of pyridyl ring in opt-2 exhibits a net negative electrostatic potential of −0.01 a.u. when compared to the net positive electrostatic potential of +0.01 a.u. at the centre of the pyridyl ring of opt-3 owing to the charge dispersion to the n-butyl group in the latter. On the other hand, there is no deviation in the electrostatic potential observed for the centre of the imidazole between the two molecules.

The MEP map of opt-2 (left) and opt-3 (right), showing the electrostatic potential charges for selected atoms.

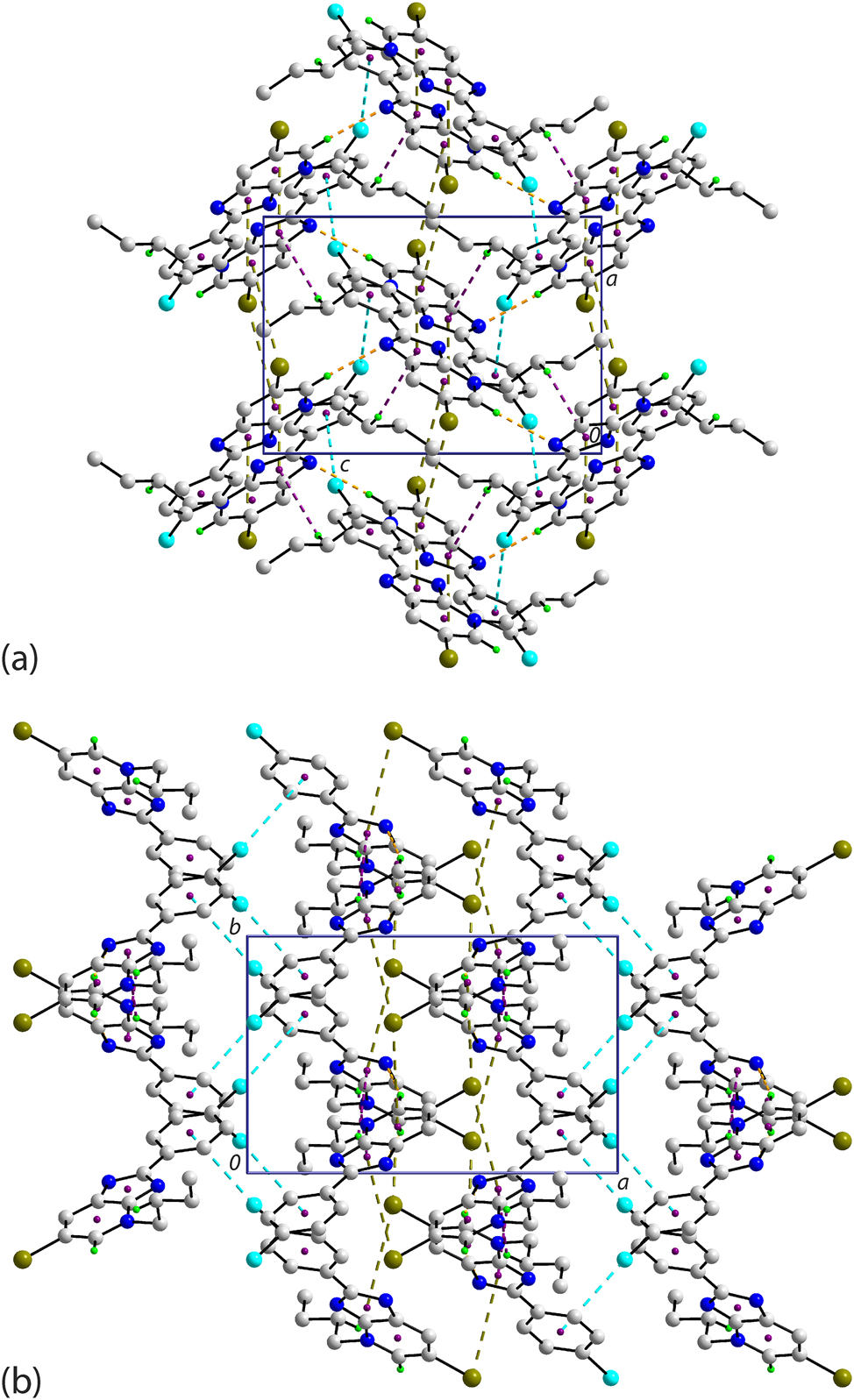

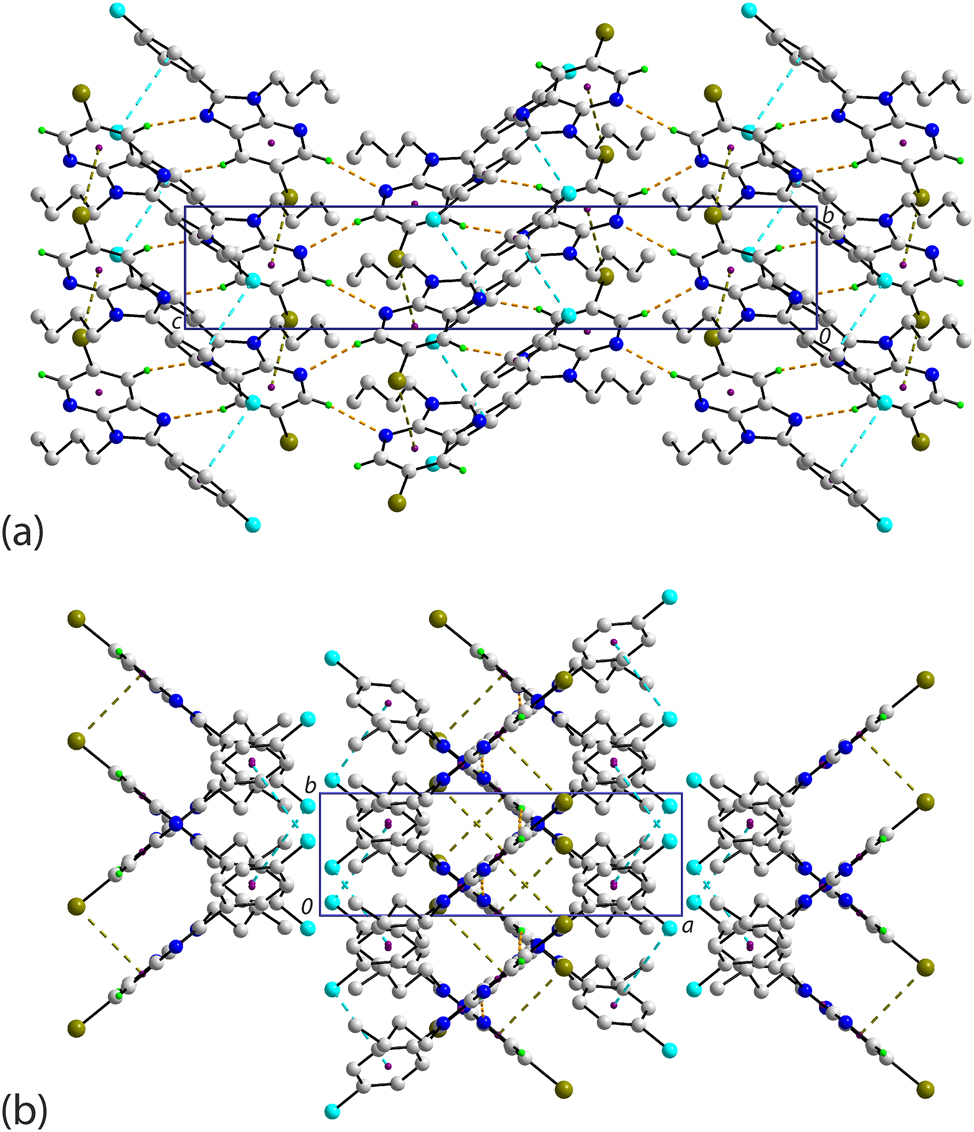

3.3 Molecular packing

The molecular packing in the crystal of 2 features a range of point-to-point contacts, as summarised in Table 4. Helical chains of molecules are formed along the b-axis and feature pyridyl-C–H⋯N(pyridyl) interactions. These chains are connected into a supramolecular layer via pyridyl-C–H⋯N(imidazoyl) interactions. As highlighted in Figure 5(a), stacks of molecules along the b-axis are connected by pyridyl-C–Br⋯π(pyridyl) and phenyl-C–Cl⋯π(phenyl) interactions; the C–X⋯Cg angles indicate side-on interactions. There is also evidence for off-set π(pyridyl)⋯π(imidazoyl) interactions which reinforce the aforementioned pyridyl-C–Br⋯π(pyridyl) contacts. The slippage between rings is 1.53 Å which brings into proximity the C3a and C6 atoms, i.e. 3.546(2) Å for symmetry operation x, 1 + y, z. When the unit-cell contents are viewed along the c-axis, Figure 5(b), it is apparent that the supramolecular layers stack along the a-axis so the chloride atoms face each other. Despite this, there are no close Cl⋯Cl contacts less than the sum of the van der Waals radii but there are some long butyl-C–H⋯Cl contacts.

Summary of intermolecular interactions (A–H⋯B; Å, °) operating in the crystals of 2 and 3.

| A | H | B | H⋯B (A°) | A⋯B (A°) | A–H⋯B (°) | Symmetry operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | ||||||

| C5 | H5 | N4 | 2.53 | 3.3967(19) | 152 | 1 − x, ½ + y, ½ − z |

| C7 | H7 | N1 | 2.56 | 3.4830(19) | 165 | 1 − x, 2 − y, 1 − z |

| C6 | Br1 | Cg(N4, C3a, C5–C7, C7a) | 3.5625(6) | 3.8816(15) | 84.77(4) | x, 1 + y, z |

| C24 | Cl1 | Cg(C21–C26) | 3.9057(7) | 4.0314(15) | 81.38(5) | x, −1 + y, z |

| Cg(N1, N3, C2, C3a, C7a) | – | Cg(N1, C4–C8) | – | 3.8773(8) | 1.32(8)a | x, −1 + y, z |

| 3 | ||||||

| C5 | H5 | N1 | 2.47 | 3.3930(19) | 164 | x, 3/2 − y, ½ + z |

| C42 | H42b | Cg(N1, N3, C2, C3a, C7a) | 2.90 | 3.6495(16) | 133 | x, 3/2 − y, ½ + z |

| C6 | Br1 | Cg(N1, N3, C2, C3a, C7a) | 3.9004(6) | 3.9391(17) | 77.18(5) | 1 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z |

| C6 | Br1 | Cg(N4, C3a, C5–C7, C7a) | 3.9831(6) | 4.9324(16) | 108.94(5) | 1 − x, 2 − y, 1 − z |

| C24 | Cl1 | Cg(C21–C26) | 3.7012(7) | 159.78(5) | 81.38(5) | 2 − x, −½ + y, ½ − z |

-

aAngle between aromatic rings.

Molecular packing in the crystal of 2 viewed in projection down the (a) a-axis and (b) c-axis. The C–H⋯N, C–Br⋯π and C–Cl⋯π interactions are highlighted as orange, olive and cyan dashed lines, respectively. Non-participating H atoms are omitted for clarity.

A rather distinct mode of molecular packing is apparent in the crystal of 3 owing to the participation of the imidazoyl ring in supramolecular connections. Thus, zigzag chains, arising from glide symmetry along the c-axis, feature pyridyl-C–H⋯N(imidazoyl) and butyl-C–H⋯π(imidazoyl) interactions, as seen in Figure 6(a). The chains are consolidated into a three-dimensional architecture by pyridyl-C–Br⋯π(imidazoyl, pyridyl) and phenyl-C–Cl⋯π(phenyl) interactions, as highlighted in Figure 6(b). As for 2, the C–Br⋯Cg angles indicate side-on interactions but the C–Cl⋯Cg angle indicates an end-on interaction.

Molecular packing in the crystal of 3 viewed in projection down the (a) b-axis and (b) c-axis. The C–H⋯N, C–H⋯π, C–Br⋯π and C–Cl⋯π interactions are highlighted as orange, purple, olive and cyan dashed lines, respectively. Non-participating H atoms are omitted for clarity.

3.4 Hirshfeld surface analysis

The crystals of 2 and 3 were subjected to a Hirshfeld surface analysis to better comprehend the nature of the intermolecular interactions. The analysis results in a dnorm-surface map containing several red spots of variable intensity, being proportional to the difference between the contact distance and the sum of van der Waals (ΣvdW) radii of the contact atoms, 43 see Table 5 for a listing. For 2, there are five red spots on the dnorm-surface resulting from three sets of interactions, viz. C5–H5⋯N4, C7–H7⋯N1 and N1⋯C26; these contacts are shorter than their respective ΣvdW in line with the relative intensity of the red spots on the Hirshfeld surface, Figure 7.

The dnorm contact distances (adjusted to neutron values) computed through the Hirshfeld surface analysis for interactions present in 2 and 3.

| Contact | Distance (A°) | ΣvdW (A°) | Δ|dnorm – ΣvdW| (A°) | Symmetry operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (X–Y⋯Z) | Y⋯Z | Y⋯Z | ||

| 2 | ||||

| C5–H5⋯N4 | 2.41 | 2.64 | 0.23 | 1 − x, ½ + y, ½ − z |

| C7–H7⋯N1 | 2.43 | 2.64 | 0.21 | 1 − x, 2 − y, 1 − z |

| N1⋯C26 | 3.17 | 3.25 | 0.08 | x, 1 + y, z |

| 3 | ||||

| C5–H5⋯N1 | 2.34 | 2.64 | 0.30 | x, 3/2 − y, ½ + z |

| Cl1⋯C23 | 3.31 | 3.45 | 0.14 | 2 − x, −½ + y, ½ − z |

| C41–H41a⋯C21 | 2.67 | 2.79 | 0.12 | x, 3/2 − y, ½ + z |

| C22–H22⋯Cl1 | 2.79 | 2.84 | 0.05 | x, ½ − y, ½ + z |

| C42–H42a⋯C25 | 2.77 | 2.79 | 0.02 | x, ½ − y, ½ + z |

| Br1⋯C44 | 3.53 | 3.55 | 0.02 | 1 − x, ½ + y, 3/2 − z |

The two views of the dnorm-surface mapping within the range of −0.0071 to 1.3930 arbitrary units for 2 (top) and 3 (bottom), showing the presence of close contacts indicated by red spots with their intensity relative to the contact distance between the interacting atoms.

The differences in the interactions between the two regioisomers are clearly seen as, in contrast to 2, 3 exhibits nine red spots which can be associated with the C5–H5⋯N1, Cl1⋯C23, C41–H41a⋯C21, C22–H22⋯Cl1, C42–H42a⋯C25 and Br1⋯C44 interactions, see Table 5. Among these, only C5–H5⋯N1 is common with 2 but with a shorter contact distance of 2.34 Å. The Cl1⋯C23 and C41–H41a⋯C21 contacts give rise to relatively intense red spots. On the other hand, moderate to weak intensities are observed for C22–H22⋯Cl1, C42–H42a⋯C25 and Br1⋯C44 as each respective contact distance is only slightly shorter than the ΣvdW radii by 0.055, 0.024 and 0.020 Å, respectively.

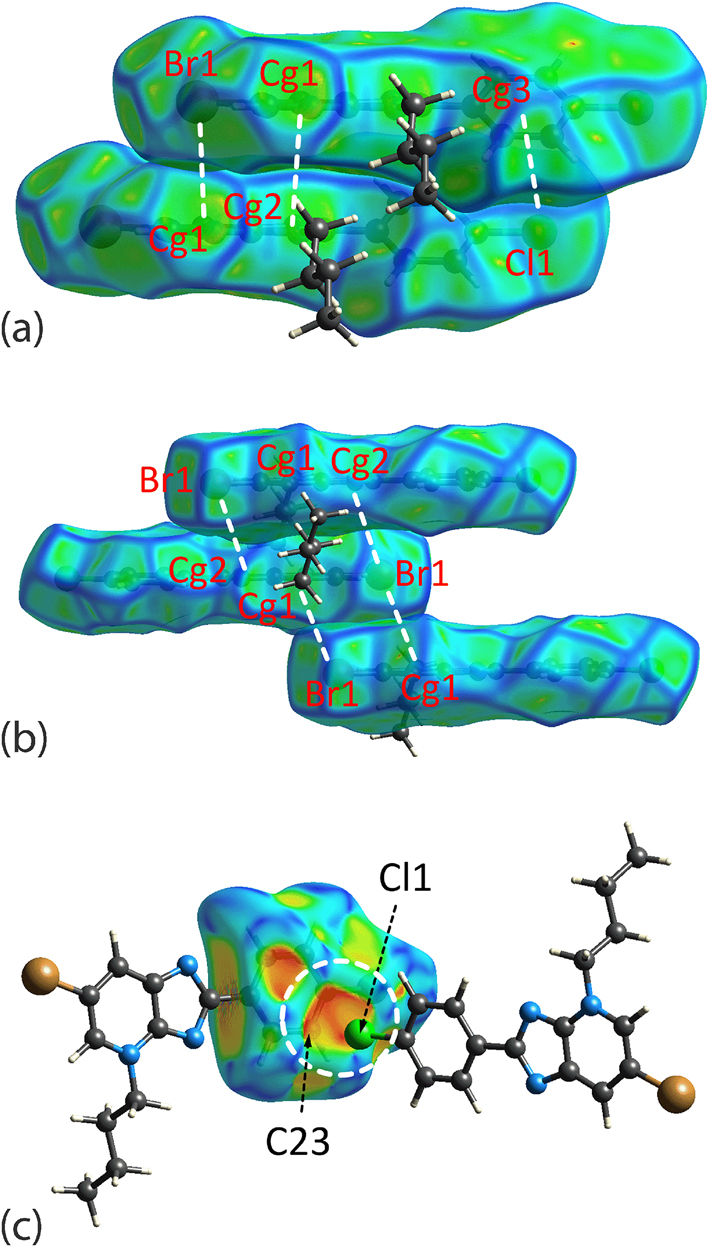

While the just mentioned close contacts in the crystals of 2 and 3 may be observed directly through the distinctive red spots on the dnorm-surfaces, there are other contacts, particularly those involving aromatic rings, such as the combination of Br1⋯π(pyridyl), π(imidazoyl)⋯π(pyridyl) (i.e. N1⋯C26) and Cl1⋯π(phenyl) contacts in 2 (symmetry operation: x, 1 + y, z). In 3, Cl1⋯π(phenyl) (i.e. Cl1⋯C23; symmetry operation: 2 − x, −½ + y, ½ − z), {Br1⋯π(pyridyl)}2 (symmetry operation: 1 − x, 2 − y, 1 − z) and combined {Br1⋯π(imidazoyl)}2 and π(pyridyl)⋯π(pyridyl) (symmetry operation: 1 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z) interactions present. Thus, these contacts were subjected to mapping of curvedness and shape index over the Hirshfeld surfaces. The mapping results show these interactions are formed partly due to shape complementarity upon stacking between the planar components or interacting in the form of a bump and a crater between the contact atoms of two molecules, Figure 8. In protein-ligand chemistry, where the ligand refers to putative drugs, such as 2 and 3, shape complementarity can maximise the configuration entropy for effective entropy-induced interactions which is one of the key factors in influencing the interaction behaviour of protein complexes apart from electrostatic-complementarity and hydrophobic-complementarity. 47

The Hirshfeld surface mapped with (a) curvedness for 2, (b) curvedness for 3 and (c) the shape index for 3, with each showing the shape complementarity between the corresponding halide atom and aromatic rings either through stacking between the planar surfaces or via a bump and crater interaction (highlighted in white dashed circle in the mapping of shape index). The property range for curvedness is within −4.0 to +4.0 arbitrary units and −1.0 to +1.0 arbitrary units for the shape index. Only the mapping for the fragments involved in the interactions are shown. Cg1 = pyridyl, Cg2 = imidazoyl and Cg3 = phenyl.

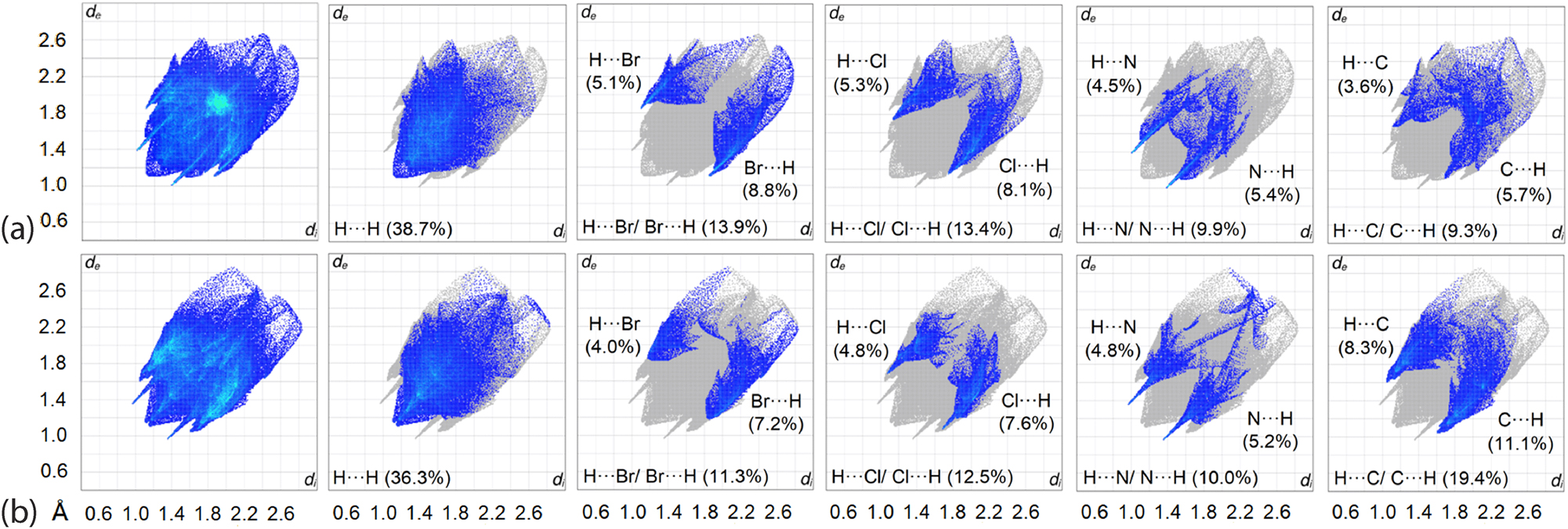

The fingerprint plot analysis was performed to quantify the close contacts identified on the dnorm-surfaces by combining the di and de contact distances at 0.01 Å intervals, see Figure 9. At first glance, the analysis results in a shield-like fingerprint plot for overall 2 and 3, and forceps-like profiles for all the decomposed fingerprint plots of the major contacts in each crystal with deviations mainly found in the diffuse region as well as in those decomposed plots with distinctive features such as that observed for H⋯Cl/Cl⋯H and H⋯N/N⋯H contacts.

The overall two-dimensional fingerprint and main decomposed plots delineated into H⋯H, H⋯Br/Br⋯H, H⋯Cl/Cl⋯H, H⋯N/N⋯H and H⋯C/C⋯H contacts along with their distributions for (a) 2 and (b) 3.

A detailed analysis in the respective decomposed fingerprint profiles reveals that 2 and 3 differ significantly in terms of contact distributions: the former is dominated by contacts in the order H⋯H (38.7 %) > H⋯Br/Br⋯H (13.9 %) > H⋯Cl/Cl⋯H (13.4 %) > H⋯N/N⋯H (9.9 %) > H⋯C/C⋯H (9.3 %) > C⋯C (5.5 %) > other minor contacts, whereas the contact distribution for 3 follows the order H⋯H (36.3 %) > H⋯C/C⋯H (19.4 %) > H⋯Cl/Cl⋯H (12.5 %) > H⋯Br/Br⋯H (11.3 %) > H⋯N/N⋯H (10.0 %) > C⋯Br/Br⋯C (4.4 %) > other minor contacts. Among the major contacts in the crystal of 2, only H⋯N/N⋯H had di + de contact distances shorter than the ΣvdW radii as indicated by the peaks in the profile which are attributed to (internal)–H5⋯N4-(external) and (internal)-N1⋯H7-(external) contacts with the respective composition being 4.5 and 5.4 %. The peaks observed for the corresponding forceps-like profile of H⋯Br/Br⋯H, H⋯Cl/Cl⋯H and H⋯C/C⋯H are assigned to the reciprocal H25⋯Br1, with a di + de distance ∼2.97 Å, H33b⋯Cl1 (∼2.92 Å) and H31a⋯C5 (∼2.83 Å), all of which are at separations longer than their ΣvdW radii of 2.94, 2.84 and 2.79 Å for H⋯Br, H⋯Cl and H⋯C, respectively. On the other hand, almost all the dominant contacts in 3 exhibit a profile with the peaks tipped at di + de distances shorter than their corresponding ΣvdW radii except for H⋯Br/Br⋯H, attributed to the reciprocal H44c⋯Br1 contact with a separation of 3.05 Å, i.e. longer than ΣvdW of 2.94 Å. In conclusion, despite being structurally closely related, 2 and 3 present rather different interaction profiles, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

3.5 Interaction energies

To evaluate their strength, the identified interactions present in the crystals of 2 and 3 were subjected to interaction energy calculations. For 2, the combination of Br1⋯π(pyridyl), π(imidazoyl)⋯π(pyridyl) and Cl1⋯π(phenyl) interactions results in the strongest interaction energy among all, i.e. Eint = −56.3 kJ/mol, with the main contribution from dispersion forces between two stacking molecules, Table 6. The C7–H7⋯N1 contact that leads to the formation of an eight-membered {⋯NC2H}2 synthon gives rise the second strongest interaction energy, i.e. Eint = −36.5 kJ/mol, followed by the C5–H5⋯N4 contact (Eint = −21.3 kJ/). The former interaction is sustained by a significant electrostatic component cf. dispersive, while the opposite is true for the latter.

Interaction energies (kJ/mol) for close contacts identified in the crystals of 2 and 3.a

| Contact | E ele | E pol | E disp | E rep | E tot | Symmetry operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | ||||||

| Br1⋯Cg1 + Cg1⋯Cg2 + Cl1⋯Cg3 | −26.2 | −2.4 | −73.2 | 45.5 | −56.3 | x, 1 + y, z |

| {C7–H7⋯N1}2 | −36.6 | −4.1 | −28.0 | 32.2 | −36.5 | 1 − x, 2 − y, 1 − z |

| C5–H5⋯N4 | −15.4 | −1.7 | −20.3 | 16.2 | −21.3 | 1 − x, ½ + y, ½ − z |

| 3 | ||||||

| C5–H5⋯N1 + C41–H41a⋯Cg3 | −31.9 | −5.4 | −41.9 | 30.0 | −49.2 | x, 3/2 − y, ½ + z |

| {Br1⋯Cg2}2 + Cg1⋯Cg1 | −13.6 | −1.4 | −40.1 | 22.4 | −32.7 | 1 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z |

| C22–H22⋯Cl1 + C42–H42a⋯C25 | −17.7 | −1.9 | −31.8 | 22.7 | −28.7 | x, ½ − y, ½ + z |

| {Br1⋯Cg1}2 | −8.5 | −0.4 | −17.3 | 10.1 | −16.1 | 1 − x, 2 − y, 1 − z |

| Br1⋯C44 | −6.1 | −0.4 | −11.3 | 8.8 | −9.1 | 1 − x, ½ + y, 3/2 − z |

| Cl1⋯Cg3 | −4.5 | −0.4 | −8.58 | 9.3 | −4.1 | 2 − x, −½ + y, ½ − z |

-

aCg1 = C3a–N4–C5–C6–C7–C7a; Cg2 = N1–C2–N3–C3a–C7a; Cg3 = C21–C22–C23–C24–C25–C26.

As for 3, the strongest interaction energy is attributed to the combination of C5–H5⋯N1 and C41–H41a⋯π(phenyl), with Eint of −49.2 kJ/mol, while the combination of {Br1⋯π(imidazoyl)}2 and π(pyridyl)⋯π(pyridyl) constitutes the second strongest interaction within the crystal of 3. The next strongest interactions arise from the combination of C22–H22⋯Cl1 and C42–H42a⋯π(phenyl) as well as {Br1⋯π(pyridyl)}2 with Eint being −28.7 and −16.1 kJ/mol, respectively. The Br1⋯C44 and Cl1⋯π(phenyl) contacts constitute the weakest interactions with Eint of −9.1 and −4.1 kJ/mol, respectively. Unlike 2, all interactions in 3 are mainly sustained by dispersive forces.

While the main interactions present in 2 and 3 are considered unique, a comparison against the literature shows that typical π⋯π interactions range between −13.8 and −93.2 kJ/mol depending on the type and number of aromatic rings involved, 48 and C–H⋯N as well as C–X⋯π (X = Cl, Br) are known to range between −11.2 and −14.4 kJ/mol 49 and −8.4 to −15.1 kJ/mol, 50 respectively. The calculated results are in line with the reported ranges for the corresponding interactions.

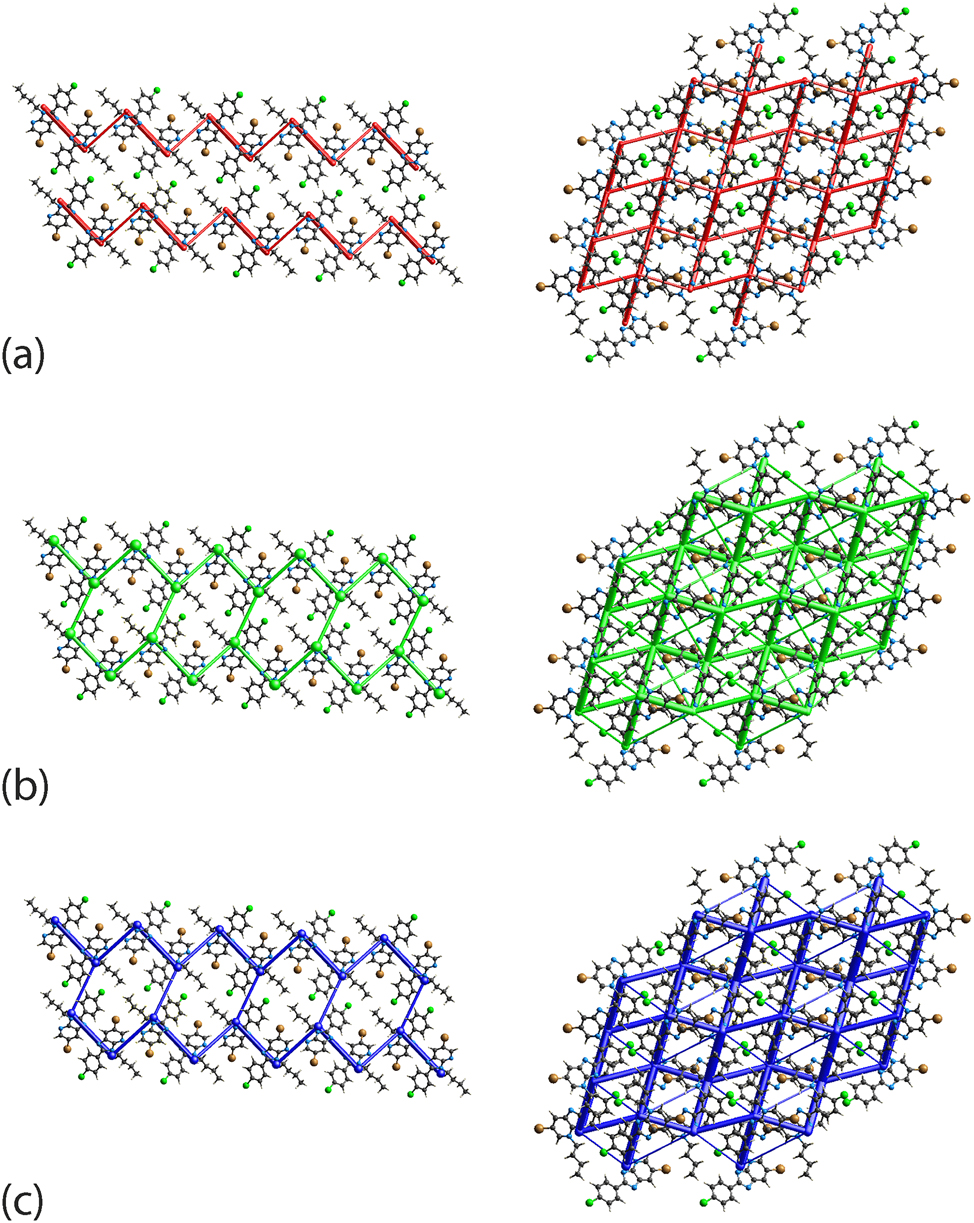

The difference in interactions operating in 2 and 3 is clear when the energy frameworks are generated within 2 × 2 × 2 unit-cells. As shown in Figure 10, the connections between molecules in 2 through {C7–H7⋯N1}2 and C5–H5⋯N4 result in a zigzag electrostatic framework extended along the c-axis, while the strong dispersion forces mainly arise from the combined interactions of Br1⋯π(pyridyl), π(imidazoyl)⋯π(pyridyl) and Cl1⋯π(phenyl) lead to additional energy layers down the a- and b-axes to form a honeycomb-like dispersion energy framework which is also integrated into the overall energy framework. Crystal 3 exhibits a distinct sheet-like framework profile manifested in the electrostatic, dispersion as well as the overall energy models.

The (a) electrostatic (red), (b) dispersion (green) and (c) overall energy frameworks (blue) for 2 (left) and 3 (right). The cylindrical radius is proportional to the relative strength of the corresponding energies and were adjusted to the same scale factor of 120 with a cut-off value of 8 kJ/mol within a 2 × 2 × 2 unit-cells.

Despite the difference in the energy frameworks, crystal lattice energy calculations through CrystalExplorer 41 show the regioisomers to have similar lattice energies of −101.3 and −103.5 kJ/mol for 2 and 3, respectively, Table 7. The result concurs with literature expectation since lattice energy is dependent upon the variation of charge and molecular volume. 51 The molecules in 2 and 3 exhibit similar molecular volumes, i.e. 376.8 and 374.1 Å3, packing coefficients, i.e. 69.0 and 69.5 %, and crystal densities, i.e. 1.575 and 1.586 g cm−3.

The lattice energy, Elattice (kJ/mol), and the corresponding energy components (Eelectrostatic, Epolarization, Edispersion and Erepulsion) calculated for a cluster of molecules within 25 Å from a reference molecule through the CE-B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) model.

| Compound | E electrostatic | E polarization | E dispersion | E repulsion | E lattice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | −56.4 | −6.1 | −111.0 | 72.2 | −101.3 |

| 3 | −54.2 | −6.6 | −110.9 | 68.2 | −103.5 |

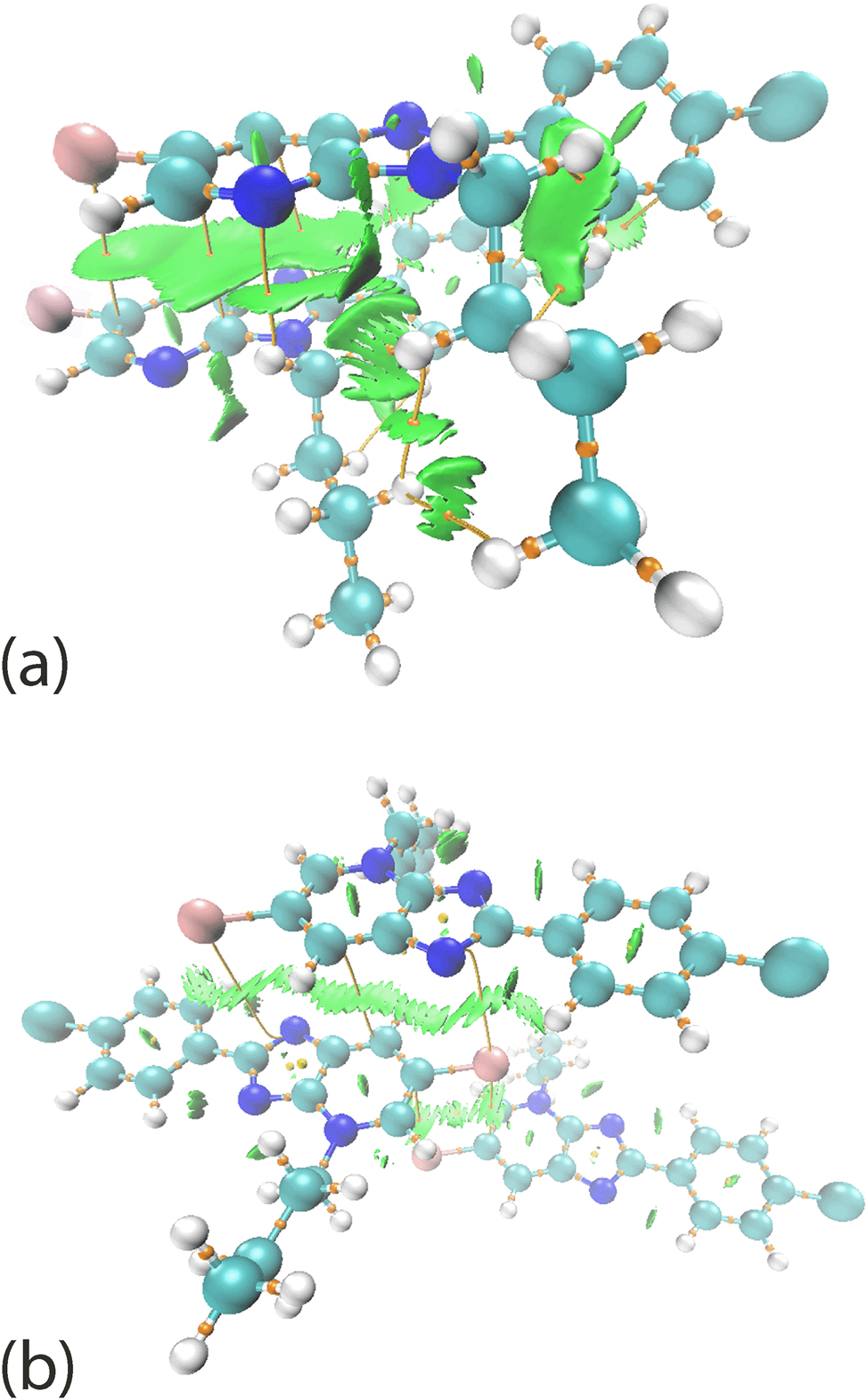

3.6 Combined quantum theory of atoms in molecule (QTAIM) and non-covalent interaction (NCI) mapping

The QTAIM analysis was performed to define the nature of the intermolecular interactions through the partitioning of molecular electron density based on the zero-flux surfaces, which are also known as line critical points (LCPs). 52 The calculation may lead to four possible outcomes represented by (3, −3), (3, −1), (3, +1) and (3, +3) notations. 39 , 53 In the analysis, the focus is upon (3, −1) line critical points between atom pairs in the respective aggregates, linked by the maximal gradient path (also known as bond path), indicating attractive forces between the atoms. The combined QTAIM and NCI mapping demonstrate that there are several (3, −1) line critical points along with a considerable localised domain detected between Br1 and π(pyridyl), π(imidazoyl)⋯π(pyridyl), Cl1⋯π(phenyl), C31–H31b⋯C22 and C22–H22⋯C32 as well as H33b⋯H32a and H33b⋯H34a, indicative of attractive forces between the offset pyridyl-imidazole rings in 2, Figure 11(a). Similar results are observed between Br1⋯π(imidazoyl), π(pyridyl)⋯π(pyridyl) and Br1⋯π(pyridyl) of 3, but with relatively fewer (3, −1) line critical points and localised domains, Figure 11(b), thereby justifying the deviation of the Eint as obtained for the corresponding pairwise molecules, Table 6.

The combined QTAIM-NCI mapping between the stacking molecules in (a) 2 and (b) 3, showing the connections represented by line critical points between the stacked molecules.

4 Conclusions

The electronic structures and molecular packing of two regioisomers show the positioning of the n-butyl group, i.e. on imidazoyl-N (2) or on pyridyl-N (3) atoms, has important ramifications. Thus, by employing a full range of experimental and computational chemistry techniques, different electronic structures in the fused rings and molecular packing patterns are discerned. Despite these differences, the calculated lattice energies show 2 is less stable than 3 by only 2.2 kJ/mol.

Acknowledgments

La Cité de l’Innovation de Fès (USMBA).

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Selma Bourichi: Spectroscopic characterisation. Khalid Boujdi: 1D and 2D NMR analyses. Rachida Amanarne: Synthesis. Younes Ouzidan: Synthesis, Writing – review & editing. Youssef Kandri Rodi: Conceptualization, Supervision. Fouad Ouazzani Chahdi: Conceptualization, Supervision. Sang Loon Tan: Calculations, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Edward R. T. Tiekink: Crystallography, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Sunway University Sdn Bhd (Grant no. GRTIN-RRO-56-2022).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Lavanya, P.; Suresh, M.; Kotaiah, Y.; Harikrishna, N.; Rao, C. V. Synthesis, Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antioxidant Activity Studies on 6-bromo-2-substitutedphenyl-1H-imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridine. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2011, 4, 69–73.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Futatsugi, K.; Huard, K.; Kung, D. W.; Pettersen, J. C.; Flynn, D. A.; Gosset, J. R.; Aspnes, G. E.; Barnes, R. J.; Cabral, S.; Dowling, M. S.; Fernando, D. P.; Goosen, T. C.; Gorczyca, W. P.; Hepworth, D.; Herr, M.; Lavergne, S.; Li, Q.; Niosi, M.; Orr, S. T. M.; Pardo, I. D.; Perez, S. M.; Purkal, J.; Schmahai, T. J.; Shirai, N.; Shoieb, A. M.; Zhou, J.; Goodwin, B. Small Structural Changes of the Imidazopyridine Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2) Inhibitors Produce an Improved Safety Profile. Med. Chem. Comm. 2017, 8, 771–779. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6MD00564K.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Aridoss, G.; Balasubramanian, S.; Parthiban, P.; Kabilan, S. Synthesis and in Vitro Microbiological Evaluation of Imidazo (4, 5-b) Pyridinylethoxypiperidones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 41, 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.10.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Guo, Z.; Tellew, J. E.; Gross, R. S.; Dyck, B.; Grey, J.; Haddach, M.; Kiankarimi, M.; Lanier, M.; Li, B. F.; Luo, Z.; McCarthy, J. R.; Moorjani, M.; Saunders, J.; Sullivan, R.; Zhang, X.; Zamani-Kord, S.; Grigoriadis, D. E.; Crowe, P. D.; Chen, T. K.; Williams, J. P. Design and Synthesis of Tricyclic Imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridin-2-ones as Corticotropin-releasing Factor-1 Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5104–5107; https://doi.org/10.1021/jm050384+.10.1021/jm050384+Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Kirwen, E. M.; Batra, T.; Karthikeyan, C.; Deora, G. S.; Rathore, V.; Mulakayala, C.; Mulakayala, N.; Nusbaum, A. C.; Chen, J.; Amawi, H.; McIntosh, K.; Trivedi, P.; Sahabjada; Shivnath, N.; Chowarsia, D.; Sharma, N.; Arshad, M.; Trivedi, A. K. 2,3-Diaryl-3H-imidazo [4,5-b] Pyridine Derivatives as Potential Anticancer and Anti-inflammatory Agents. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2017, 7, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2016.05.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Ock, J.; Kim, S.; Yi, K.-Y.; Kim, N. J.; Soo Han, H.; Cho, J. Y.; Suk, K. A Novel Anti-neuroinflammatory Pyridylimidazole Compound KR-31360. Biochem. Pharm. 2010, 79, 596–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2009.09.026.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Hartwich, A.; Zdzienicka, N.; Schols, D.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R.; Głowacka, I. E. Design, Synthesis and Antiviral Evaluation of Novel Acyclic Phosphonate Nucleotide Analogs with Triazolo [4, 5-b] Pyridine, Imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridine and Imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridin-2 (3H)-one Systems. Nucleos. Nucleot. Nucl. 2020, 39, 542–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/15257770.2019.1669046.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Özçelik, A.; Ulger, M.; Aslan, G.; Emekdaş, G.; Ozden, T. Studies on in Vitro Antimycobacterial Activities of Some 2-substituted Imidazo [4, 5-b] and [4, 5-c] Pyridine Derivatives. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2014, 59, 5–8.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Foster, A. C.; Kemp, J. A. Glutamate- and GABA-based CNS Therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2005.11.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Dowsett, M.; Smithers, D.; Moore, J.; Trunet, P. F.; Coombes, R. C.; Powles, T. J.; Rubens, R.; Smith, I. E. Endocrine Changes with the Aromatase Inhibitor Fadrozole Hydrochloride in Breast. Eur. J. Canc. 1994, 30, 1453–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-8049(94)00281-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Bamford, M. 3 H+/K+ ATPase Inhibitors in the Treatment of Acid-related Disorders. Prog. Med. Chem. 2009, 47, 75–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6468(08)00203-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Hranjec, M.; Lučić, B.; Ratkaj, I.; Pavelić, S. K.; Piantanida, I.; Pavelić, K.; Karminski-Zamola, G. Novel Imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and Triaza-benzo[c]fluorene Derivatives: Synthesis, Antiproliferative Activity and DNA Binding Studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2748–2758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.062.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Bavetsias, V.; Sun, C.; Bouloc, N.; Reynisson, J.; Workman, P.; Linardopoulos, S.; McDonald, E. Hit Generation and Exploration: Imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridine Derivatives as Inhibitors of Aurora Kinases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 6567–6571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.09.076.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Saady, A.; Rais, Z.; Benhiba, F.; Salim, R.; Ismaily Alaoui, K.; Arrousse, N.; Elhajjaji, F.; Taleb, M.; Jarmoni, K.; Kandri, R. Y.; Warad, I.; Zarrouk, A. Chemical, Electrochemical, Quantum, and Surface Analysis Evaluation on the Inhibition Performance of Novel Imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridine Derivatives Against Mild Steel. Corros. Sci. 2021, 189, 109621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109621.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Saady, A.; Ech-chihbi, E.; El-Hajjaji, F.; Benhiba, F.; Zarrouk, A.; Kandri Rodi, Y.; Taleb, M.; El Biache, A.; Rais, Z. Molecular Dynamics, DFT and Electrochemical to Study the Interfacial Adsorption Behavior of New Imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridine Derivative as Corrosion Inhibitor in Acid Medium. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2021, 51, 245–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10800-020-01498-x.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Galmiche, J. P.; Bruley, D. V. S.; Ducrotté, P.; Sacher-Huvelin, S.; Vavasseur, F.; Taccoen, A.; Fiorentini, P.; Homerin, M. Tenatoprazole, a Novel Proton Pump Inhibitor with a Prolonged Plasma Half‐Life: Effects on Intragastric pH and Comparison with Esomeprazole in Healthy Volunteers. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 19, 655–662. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01893.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Edvinsson, L.; Linde, M. New Drugs in Migraine Treatment and Prophylaxis: Telcagepant and Topiramate. Lancet 2010, 376, 645–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60323-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Ho, T. W.; Ferrari, M. D.; Dodick, D. W.; Galet, V.; Kost, J.; Fan, X.; Leibensperger, H.; Froman, S.; Assaid, C.; Lines, C.; Koppen, H.; Winner, P. K. Efficacy and Tolerability of MK-0974 (Telcagepant), a New Oral Antagonist of Calcitonin Gene-related Peptide Receptor, Compared with Zolmitriptan for Acute Migraine: A Randomised, Placebo-controlled, Parallel-treatment Trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 2115–2123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61626-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Bourichi, S.; Misbahi, H.; Kandri, R. Y.; Ouazzani Chahdi, F.; Essassi, E. M.; Szabó, S.; Szalontai, B.; Gajdács, M.; Molnár, J.; Spengler, G. In Vitro Evaluation of the Multidrug Resistance Reversing Activity of Novel Imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridine Derivatives. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 999–4003. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.12687.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Bourichi, S.; Kandri Rodi, Y.; Hökelek, T.; Haoudi, A.; Renard, C.; Capet, F. Crystal Structure and Hirshfeld Surface Analysis of 4-Allyl-6-bromo-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-4H-imidazo [4, 5-b] Pyridine. Acta Crystallogr. E 2019, 75, 43–48; https://doi.org/10.1107/S2056989018017322.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Ouzidan, Y.; Essassi, E. M.; Luis, S. V.; Bolte, M.; El Ammari, L. 6-Bromo-3-methyl-2-phenyl-3H-imidazo [4, 5-b]pyridine. Acta Crystallogr. E 2011, 67, o1684. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600536811022318.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Shelke, R. N.; Pansare, D. N.; Pawar, C. D.; Deshmukh, A. K.; Pawar, R. P.; Bembalkar, S. R. Synthesis of 3H-imidazo[4,5-b] Pyridine with Evaluation of Their Anticancer and Antimicrobial Activity. Eur. J. Chem. 2017, 8, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5155/eurjchem.8.1.25-32.1522.Suche in Google Scholar

23. CrysAlis PRO. Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, Yarnton, Oxfordshire, England, 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Sheldrick, G. M. Shelxt-Integrated Space-group and Crystal-structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053273314026370.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with Shelxl. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053229614024218.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Farrugia, L. J. WinGX and Ortep for Windows: An Update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889812029111.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Diamond, Visual Crystal Structure Information System, Version 3.1, CRYSTAL IMPACT, Postfach 1251, D-530 02 Bonn, Germany, 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Spek, A. L. checkCIF Validation ALERTS: What They Mean and How to Respond. Acta Crystallogr. E 2020, 76, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2056989019016244.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Roothaan, C. C. J. New Developments in Molecular Orbital Theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1951, 23, 9–89. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.23.69.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Pietro, W. J.; Francl, M. M.; Hehre, W. J.; DeFrees, D. J.; Pople, J. A.; Binkley, J. S. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. 24. Supplemented Small Split-valence Basis Sets for Second-row Elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 5039–5048. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00383a007.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Becke, A. D. Density-Functional Thermochemistry. III. the Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.464913.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. https://doi.org/10.1039/B508541A.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting Basis Sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. https://doi.org/10.1039/B515623H.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Caricato, M.; Li, X.; Hratchian, H. P.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Bloino, J.; Zheng, G.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Montgomery, J. A.; Peralta, Jr. J. E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Knox, J. E.; Cross, J. B.; Bakken, V.; Adamo, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Gomperts, R.; Stratmann, R. E.; Yazyev, O.; Austin, A. J.; Cammi, R.; Pomelli, C.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Voth, G. A.; Salvador, P.; Dannenberg, J. J.; Dapprich, S.; Daniels, A. D.; Farkas, Ö.; Foresman, J. B.; Ortiz, J. V.; Cioslowski, J.; Fox, D. J. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, Connecticut, USA, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Glendening, E. D.; Reed, A. E.; Carpenter, J. E.; Weinhold, F. NBO Version 3.1; University of Winconsin: Madison, USA, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Reed, A. E.; Curtiss, L. A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular Interactions from a Natural Bond Orbital, Donor-acceptor Viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr00088a005.Suche in Google Scholar

37. Dennington, R.; Keith, T. A.; Millam, J. M. GaussView, Version 6; Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission: Kansas, USA, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Johnson, E. R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A. J.; Yang, W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498–6506. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja100936w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Lu, T.; Multiwfn, C. F. A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.22885.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD – Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Turner, M. J.; McKinnon, J. J.; Wolff, S. K.; Grimwood, D. J.; Spackman, P. R.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M. A. CrystalExplorer, Version 17.5; University of Western Australia: Western Australia, Australia, 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Tan, S. L.; Jotani, M. M.; Tiekink, E. R. T. Utilizing Hirshfeld Surface Calculations, Non-covalent Interaction (NCI) Plots and the Calculation of Interaction Energies in the Analysis of Molecular Packing. Acta Crystallogr. E 2019, 75, 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2056989019001129.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Spackman, M. A.; Jayatilaka, D. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1039/B818330A.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Mackenzie, C. F.; Spackman, P. R.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M. A. CrystalExplorer Model Energies and Energy Frameworks: Extension to Metal Coordination Compounds, Organic Salts, Solvates and Open-shell Systems. IUCrJ 2017, 4, 575–587. https://doi.org/10.1107/S205225251700848X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Martin, F.; Zipse, H. Charge Distribution in the Water Molecule–A Comparison of Methods. J. Comp. Chem. 2005, 26, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20157.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Singh, U. C.; Kollman, P. A. An Approach to Computing Electrostatic Charges for Molecules. J. Comp. Chem. 1984, 15, 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.540050204.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cao, D. The Role of Shape Complementarity in the Protein-protein Interactions. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3271. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03271.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. Cabaleiro-Lago, E. M.; Rodríguez-Otero, J. On the Nature of σ–σ, σ–π, and π–π Stacking in Extended Systems. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 9348–9359. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.8b01339.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Geiger, D. K.; DeStefano, M. R. Conformational Differences and Intermolecular C–H⋯N Interactions in Three Polymorphs of a Bis(pyridinyl)-subtituted Benzimidazole. Acta Crystallogr. C 2016, 72, 867–874. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053229616015837.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Riley, K. E.; Tran, K.-A. Strength and Character of R–X⋯π Interactions Involving Aromatic Amino Acid Sidechains in Protein-ligand Complexes Derived from Crystal Structures in the Protein Data Bank. Crystals 2017, 7, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst7090273.Suche in Google Scholar

51. Jenkins, H. D. B.; Roobottom, H. K.; Passmore, J.; Glasser, L. Relationships Among Ionic Lattice Energies, Molecular (Formula Unit) Volumes, and Thermochemical Radii. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 3609–3620. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic9812961.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Wick, C. R.; Clark, T. On Bond-critical Points in QTAIM and Weak Interactions. J. Mol. Model. 2018, 24, 142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-018-3684-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Foroutan-Nejad, C.; Shahbazian, S.; Marek, R. Toward a Consistent Interpretation of the QTAIM: Tortuous Link Between Chemical Bonds, Interactions, and Bond/line Paths. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 10140–10152. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201402177.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2024-0120).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Gd5Rh19Sb12 − a metal-rich antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12 related structure

- Synthesis of schafarzikite-type (PbBi)(Fe1−xMn x )O4: a study on structural, spectroscopic and thermogravimetric properties

- Crystals of Racemic Mimics. Part II. Some Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds crystallizing thus, and remarks on the chirality of atoms containing non-bonded electron pairs as stereogenic centers

- The plumbides SrPdPb and SrPtPb

- In situ crystallization of the tetrahydrate of pentafluoro-benzenesulfonic acid, featuring the Eigen ion (H9O4)+

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Two novel copper(II) supramolecular complexes: synthesis, crystal structures, and Hirshfeld surface analysis

- 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

- Synthesis, crystal structure, and Hirshfeld analysis of an ultrashort hybrid peptide

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Ni3Sn4 and FeAl2 as vacancy variants of the W-type (“bcc”) structure

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Gd5Rh19Sb12 − a metal-rich antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12 related structure

- Synthesis of schafarzikite-type (PbBi)(Fe1−xMn x )O4: a study on structural, spectroscopic and thermogravimetric properties

- Crystals of Racemic Mimics. Part II. Some Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds crystallizing thus, and remarks on the chirality of atoms containing non-bonded electron pairs as stereogenic centers

- The plumbides SrPdPb and SrPtPb

- In situ crystallization of the tetrahydrate of pentafluoro-benzenesulfonic acid, featuring the Eigen ion (H9O4)+

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Two novel copper(II) supramolecular complexes: synthesis, crystal structures, and Hirshfeld surface analysis

- 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

- Synthesis, crystal structure, and Hirshfeld analysis of an ultrashort hybrid peptide

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Ni3Sn4 and FeAl2 as vacancy variants of the W-type (“bcc”) structure