Abstract

Objectives

Chemotherapy-induced senescent cells are recognized to lead to cancer progression and resistance to treatment by releasing factors associated with the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Therefore, targeting SASP via senomorphic agents is an emerging therapeutic strategy. In this study, we evaluated the potential of L-type Ca2+ channel blockers, nifedipine and verapamil, and K+ ATP channel openers, minoxidil and diazoxide, to influence senescence development and SASP-related secretory activity.

Methods

Senescence development was evaluated by beta-galactosidase activity and senescent cell morphology. Senomorphic activity was evaluated by measuring the secretion levels of total protein and IL-6, which are considered indicators of the SASP. Additionally, the effects of SASP were tested for cancer cell proliferation using the transwell system and cell migration using wound healing methods.

Results

Our findings indicate that neither L-type Ca2+ channel blockers, nifedipine and verapamil, nor K+ ATP channel openers, minoxidil and diazoxide, influence the induction of senescence by doxorubicin or alter senescent cell morphology. The K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide notably inhibit the secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 and VEGF-A in senescent HeLa cells, implying potential senomorphic properties. Moreover, although minoxidil and diazoxide did not reduce the proliferative effects of SASP on cancer cells, these drugs modulated the secretory phenotype of senescent cells to reduce HeLa cell migration significantly.

Conclusions

We suggest that minoxidil and diazoxide may have potential as senomorphic adjuvants in cancer therapy. If confirmed by invivo and clinical studies, these drugs may be repurposed to attenuate SASP-induced tumor progression. Moreover, K+ ATP channels represent potential targets for senotherapy.

Introduction

Cellular senescence, initially characterized by Hayflick and Moorhead, refers to a distinct cellular state marked by an irreversible loss of proliferative capacity [1]. Senescence can occur replicatively at the end of the cellular lifespan (replicative senescence) or can be triggered rapidly by various stressors (stress-induced premature senescence, SISP). Senescent cells exhibit dramatic morphological changes, such as increased cell size and multinucleation [2], 3]. Moreover, these cells display increased activity of senescence-associated β-galactosidase and secrete a complex mixture of immune-modulatory factors collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [4]. The SASP includes chemokines, inflammatory cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases, growth factors, bioactive lipids, and exosomes [5], [6], [7]. Through the SASP, senescent cells can contribute to undesirable effects such as tumor initiation, migration, invasion, and drug resistance [8], [9], [10]. The accumulation of senescent cells within tissues has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various age-related diseases, including cancer, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and aging. Therefore, the selective elimination of senescent cells and modulation of the SASP represent a promising therapeutic strategy.

One of the stressors that can trigger stress-induced premature senescence is chemotherapeutic drugs with genotoxic activity. Although chemotherapy provides significant therapeutic benefits, it can lead to the accumulation of therapy-induced senescent cells, which may contribute to various detrimental outcomes. These effects, largely driven by the SASP, include chronic inflammation, enhanced tumorigenesis, induction of bystander senescence, and increased drug resistance [8], [9], [10]. Therefore, pharmacological interventions targeting chemotherapy-induced SASP, known as senomorphics, are being considered as potential adjuvant therapies to enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy and improve the quality of life in cancer patients [11].

The membrane potential regulated by ion channels plays a critical role in many physiological processes, including cell cycle progression, cell volume regulation, proliferation, muscle contraction, and wound healing [12]. One of the important roles of ion channels is to regulate secretion mechanisms in cells. For instance, K+ ATP channels are involved in the insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells and the glucagon release from pancreatic alpha cells [13], [14], [15]. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (such as P/Q-type, L-type, and T-type) play a crucial role in both neurotransmitter and hormone release [16]. These regulatory roles of ion channels in secretory mechanisms suggest that ion channel modulators may also have the potential to modulate the SASP. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to evaluate the potential senomorphic effects of the FDA-approved K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide and the voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and verapamil. Accordingly, we used HeLa cancer cells, which are known to express both of these channel types [17], 18], and investigated how these selected ion channel modulators influence doxorubicin-induced SASP development, as well as how the resulting SASP affects cancer cell proliferation and migration.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and drug concentration determination with xCELLigence

Human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells were obtained from ŞAP Institute (Turkey). HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere in 5 % CO2. Senescence induction was achieved by 72 h incubation of 300 nM doxorubicin (Tocris) as previously described [5]. Ion channel modulators nifedipine (Tocris), verapamil (Sigma), minoxidil (Tocris), and diazoxide (Tocris) were dissolved in DMSO, and the drugs were applied to the medium at a rate that would not cause DMSO toxicity (0.2 %).

The activity of ion channel modulators on cell viability in HeLa cells was evaluated using the xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA) DP system (Agilent) [19], 20]. Cells were seeded on e-plates at 5,000 cells/well. After approximately 16 h, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium, containing drugs at increasing logarithmic concentrations (10–300 µM). Cell proliferation was quantified as the normalized cell index using RTCA software v2.0. Viability was determined by comparing maximum cell index values obtained at 48 h of drug exposure.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining assay

The effects of ion channel modulators on senescence were evaluated using the Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining kit (Cell Signaling). After 2 h of preincubation with ion channel modulators, HeLa cells were treated with 300 nM doxorubicin for 72 h. Following treatment, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 15 min at room temperature. After washing twice with PBS, the β-Galactosidase Staining Solution, pH 6.0, was added, and the cells were incubated in a CO2-free dry incubator for 16 h. Development of blue staining in the perinuclear region was visualized by light and phase-contrast microscopy (Leica DMIL). SA-β-gal positive cells were quantified as a percentage of total cells.

Holographic imaging

As another marker of senescence development, changes in cell morphology were evaluated by holographic microscopy. After preincubation with channel modulators (2 h), HeLa cells were treated with 300 nM doxorubicin for 72 h. Parameters, including cell volume, area, maximum thickness, and mean thickness, were measured with a Holomonitor M4 system using Holostudio 2.7 software (Phase Holographic Imaging AB, Sweden) [3].

Determination of protein amount per cell

HeLa cells were treated with 300 nM doxorubicin for 72 h for senescence induction, washed with PBS, incubated in serum and phenol red-free medium containing ion channel modulators for 48 h. Cells were collected by trypsinization, and the total number of cells was counted. Samples were lysed in homogenization buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 400 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 100 μM sodium ortho-vanadate, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM NaF, plus protease inhibitors) and sonicated (Sonics Vibra Cell). The total protein amount in the cells was measured using the BCA Protein Quantitation Kit (Pierce). The “total protein amount per cell” was calculated by dividing the number of cells by the number of cells.

MTT assay

HeLa cells were treated with 300 nM doxorubicin for 72 h, followed by incubation with channel modulators for 48 h. After treatment, the culture medium was carefully removed, and cells were incubated with MTT solution (1 g/L in PBS; Invitrogen) for 3 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the MTT solution was aspirated, and the formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices SpectraMax i3x). Cell viability (%) was calculated based on absorbance values.

Collection of conditional media

HeLa cells were treated with 300 nM doxorubicin for 72 h for senescence induction. After the cells were washed twice with PBS, serum and phenol red-free medium were added. To evaluate the role of ion channel modulators in the development of SASP, senescent or non-senescent cell groups were treated with ion channel modulators (1 μM, 3 μM, 10 μM, 30 and 100 μM) for 48 h. Then, the medium of the cells was collected and centrifuged at 800×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and filtered through 0.2 μm filters [5]. In addition, the cells collected from the CMs were trypsinized, and the total cell number was determined. Then, the CMs were normalized according to cell numbers and stored at −20 °C until analysis.

Measurement of IL-6 levels in conditional media

IL-6 levels in CM were determined using a Human IL-6 ELISA Kit (Thermo). Normalized CMs were added to the wells of the plate in the kit, and biotinylated antibody solution was added to them. After 2 h of incubation at room temperature, the wells were washed and incubated with streptavidin-HRP solution for 30 min. Subsequently, TMB substrate was added, and reactions were stopped after 30 min in the dark. Absorbance values of the wells were measured at 450 nm in the plate reader (Molecular Devices SpectraMax i3x). IL-6 levels in CM were calculated as pg/ml according to the IL-6 standards in the kit.

Measurement of VEGF-A levels in conditional media

VEGF-A levels were analyzed in CM using a Human VEGF-A ELISA Kit (Thermo). Normalized CMs were added to the wells of the kit plate and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Following incubation, the wells were washed, and a biotinylated antibody solution was added and incubated for 1 h. After washing, the wells were treated with streptavidin-HRP solution and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the wells were washed again and incubated with TMB substrate for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Reactions were terminated with stop solution, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm (Molecular Devices SpectraMax i3x). VEGF-A levels in CM were calculated as pg/ml according to the VEGF-A standards in the kit.

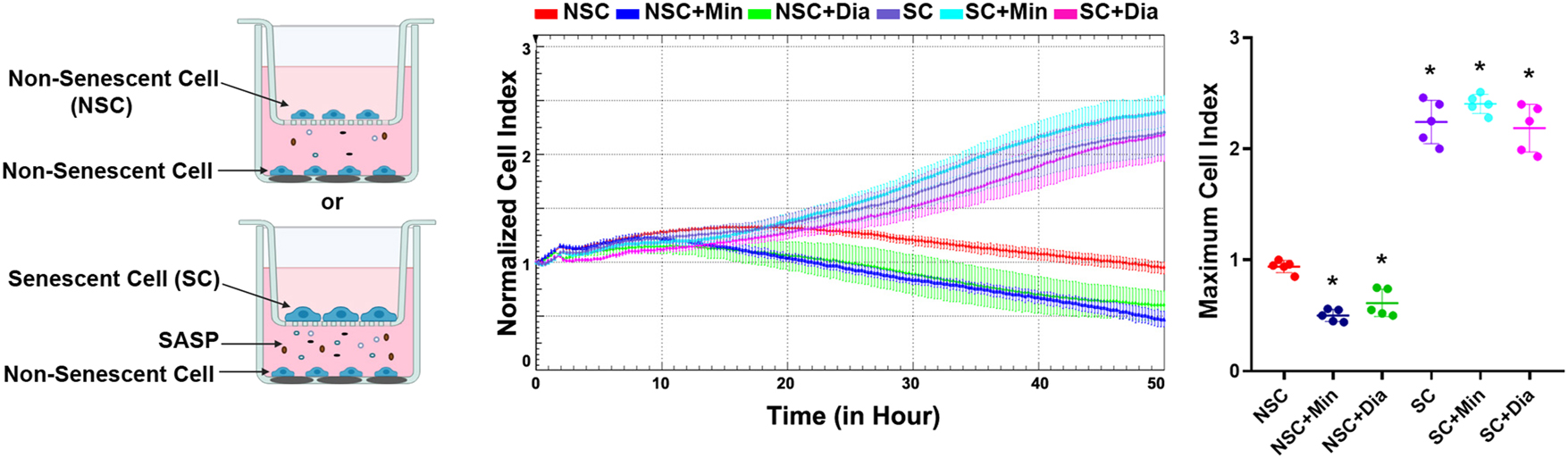

Determination of cell proliferation by co-culture

The effect of factors secreted from senescent/non-senescent cells on HeLa cell proliferation was determined by co-culture experiments using the xCELLigence RTCA DP system (Agilent). 100,000 senescent/non-senescent HeLa cells were seeded in the upper plate with a 0.4 µm pore diameter membrane at the bottom. 5,000 non-senescent HeLa cells, whose proliferation would be assessed, were seeded on the lower plate with microelectrodes at the bottom. After overnight incubation, both compartments were washed with PBS, and serum-free medium with or without channel modulators was added. Cell proliferation in the lower plate was monitored every 15 min for 50 h, and maximum cell index values were compared across groups [5].

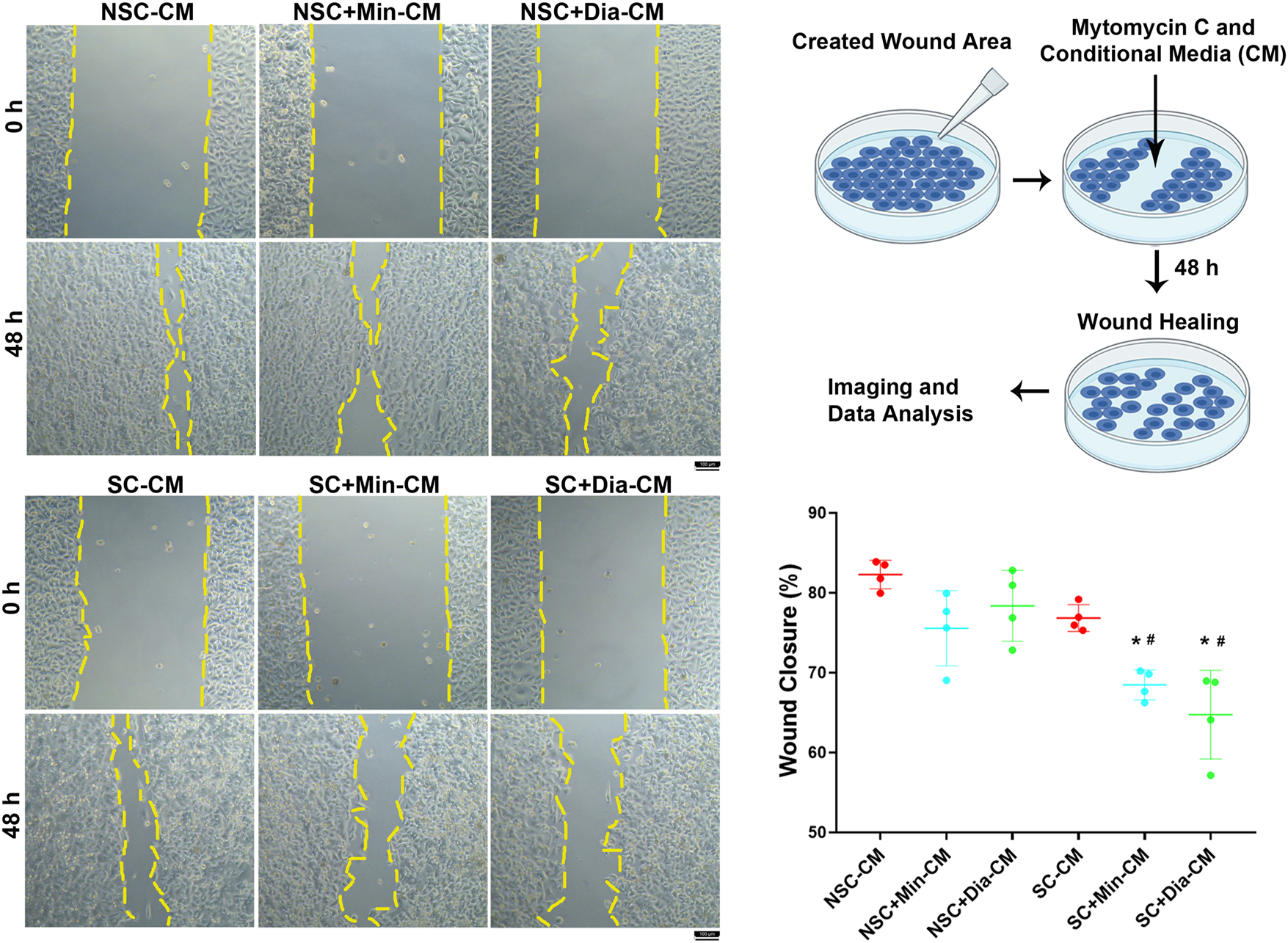

Determination of cell migration by wound-healing assay

A wound-healing assay was performed to evaluate the effects of senescent/non-senescent CM on HeLa cell migration [21]. 750,000 HeLa cells/well were plated in a 12-well plate and incubated until 100 % confluency. Scratch wounds were created with a 10 µl pipette tip, and the cells were washed twice with PBS. CMs (pre-warmed at 37 °C) were added to the cells and treated with 0.1 μg/mL mitomycin C to prevent cell proliferation. Then, two wound images were randomly taken for each well at 0 and 48 h using a phase contrast microscope (Leica DMIL). The wound area was measured using the Image J program from the phase contrast images, and “wound closure%” was calculated [5].

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as the mean±S.E.M. and analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test with GraphPad Prism 8.0.1. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

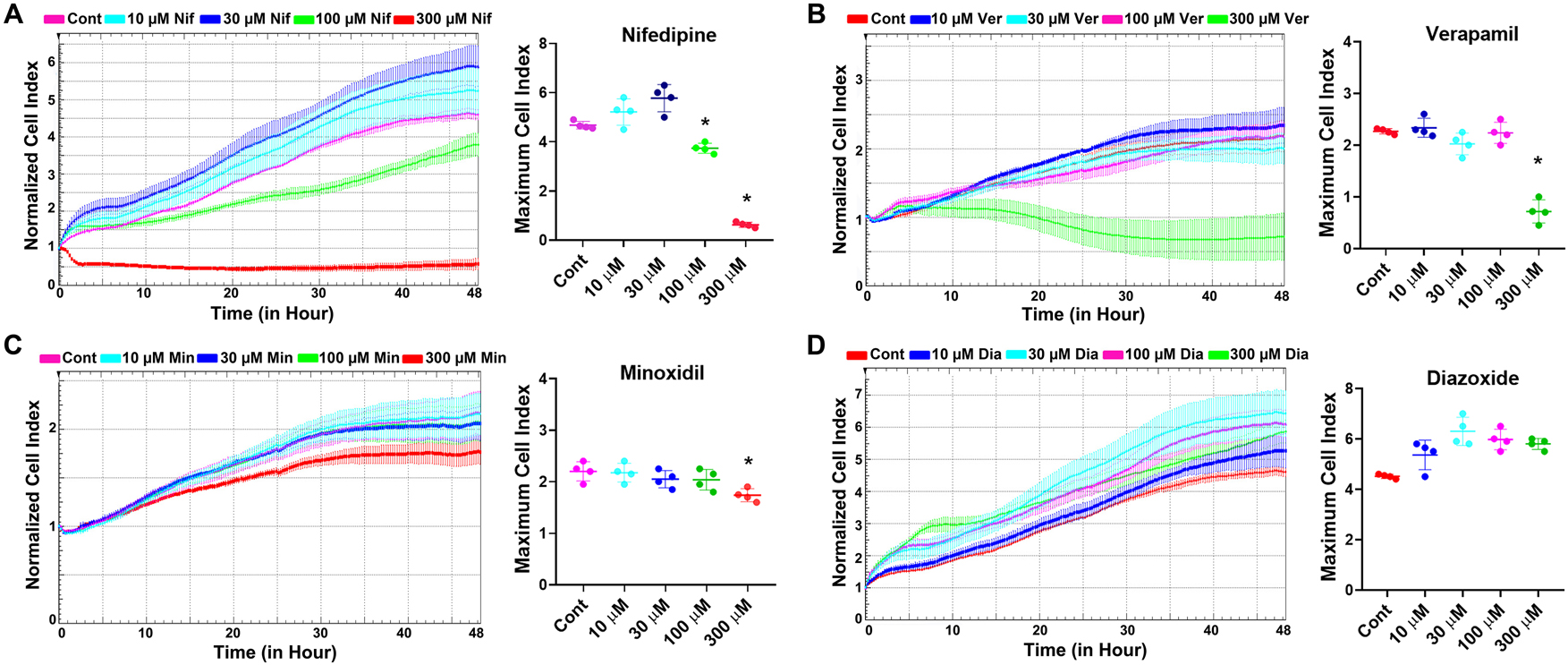

Determination of the concentrations of nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide to be used in testing senomorphic activity

In our study, we first determined the concentrations of the L-type Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and verapamil, and the K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide, to be used to test their senomorphic activities. For this purpose, the drugs were applied to HeLa cells in a concentration-dependent manner, and their effects on cell viability were monitored over 48 h using the xCELLigence system. Based on the normalized cell index values, which indicate cell proliferation in the xCELLigence system, concentrations that did not affect cell viability were selected for evaluating senomorphic activity.

According to the literature, cardioprotective effects of diazoxide have been studied in vivo and ex vivo at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 µM, and the sensitivity of pancreatic beta cells to diazoxide falls within the same concentration range; therefore, 100 µM was selected as the diazoxide concentration [22]. On the other hand, since the concentration range required for verapamil to inhibit Ca2+ channels is reported as 10–50 µM, 30 µM was selected as the verapamil concentration [23]. For nifedipine and minoxidil, the highest concentrations that did not exhibit cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells were used to evaluate their senomorphic potential (Figure 1A–C).

Determination of the effects of L-type Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and verapamil, and K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide on cell viability. (A) Original real-time monitoring graph and maximum cell index of the concentration-dependent effects of nifedipine on HeLa cell viability. (B) Original real-time monitoring graph and maximum cell index analysis of the concentration-dependent effects of verapamil on HeLa cell viability. (C) Original real-time monitoring graph and maximum cell index analysis of the concentration-dependent effects of minoxidil on HeLa cell viability. (D) Original real-time monitoring graph and maximum cell index analysis of the concentration-dependent effects of diazoxide on HeLa cell viability. Cont, control; Nif, nifedipine; Ver, verapamil; Min, minoxidil; Dia, diazoxide. *Indicates statistically significant difference from the control group (One Way ANOVA, n=4, p<0.05).

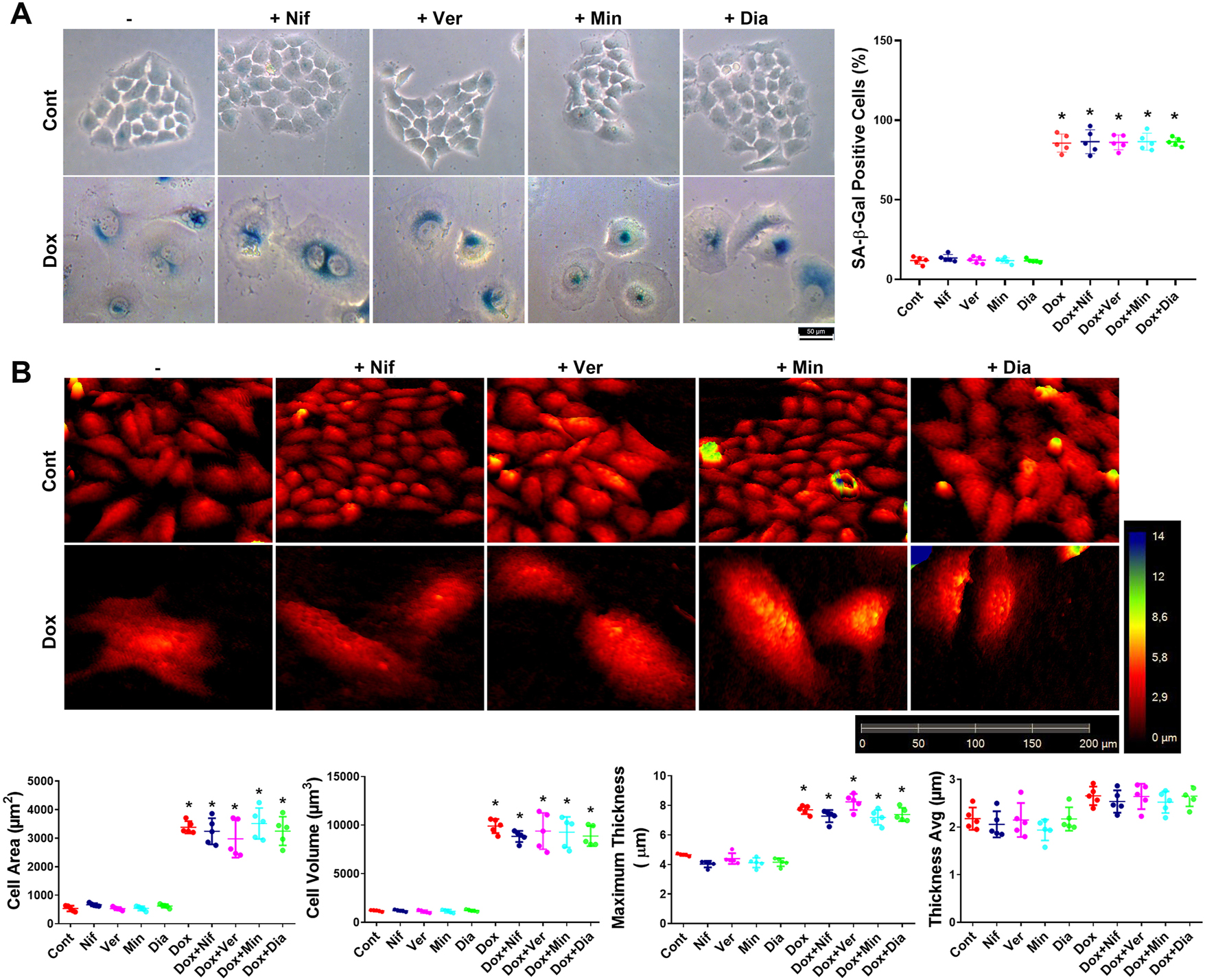

Evaluation of the effects of nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide on senescence development and senescent cell morphology

To determine the role of ion channel modulators in the development of senescence, SA-β-Gal staining, which is a widely used senescence marker, was performed. For this purpose, HeLa cells were pre-treated with nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide (4 h), followed by treatment with doxorubicin (300 nM, 72 h) to evaluate senescence induction. After incubation, holographic images of the cells were captured, and subsequently, SA-β-Gal staining was conducted. Our results showed a significant increase in the number of SA-β-Gal positive cells with doxorubicin treatment; however, ion channel modulators did not alter this effect (Figure 2A). These findings suggest that nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide do not play a role in doxorubicin-induced senescence development in HeLa cells.

Evaluation of the effects of the L-type Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and verapamil, and the K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide on senescence development and senescent cell morphology. (A) Determination of the effects of nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide on senescence induction via SA-β-Gal staining. (B) Analysis of nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide effects on senescent cell morphology using holographic microscopy. Cont, control; Nif, 30 µM nifedipine; Ver, 30 µM verapamil; Min, 100 µM minoxidil; Dia, 100 µM diazoxide; Dox, 300 nM doxorubicin; Dox+Nif, 300 nM doxorubicin + 30 µM nifedipine; Dox+Ver, 300 nM doxorubicin + 30 µM verapamil; Dox+Min, 300 nM doxorubicin + 100 µM minoxidil; Dox+Dia, 300 nM doxorubicin + 100 µM diazoxide. *Indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the control group (One-Way ANOVA, n=5, p<0.05).

On the other hand, it has been shown that changes in senescent cell morphology, particularly in the cell membrane, may affect the secretory profile of senescent cells [5]. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the possible role of L-type Ca2+ channel and K+ ATP channel modulators in the development of senescent cell morphology using holographic microscopy images. In doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells, cell area, volume, and maximum thickness increased significantly compared to the control group, while average thickness did not change (Figure 2B). Pre-treatment with nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide did not affect these altered morphological parameters observed in senescent cells (Figure 2B).

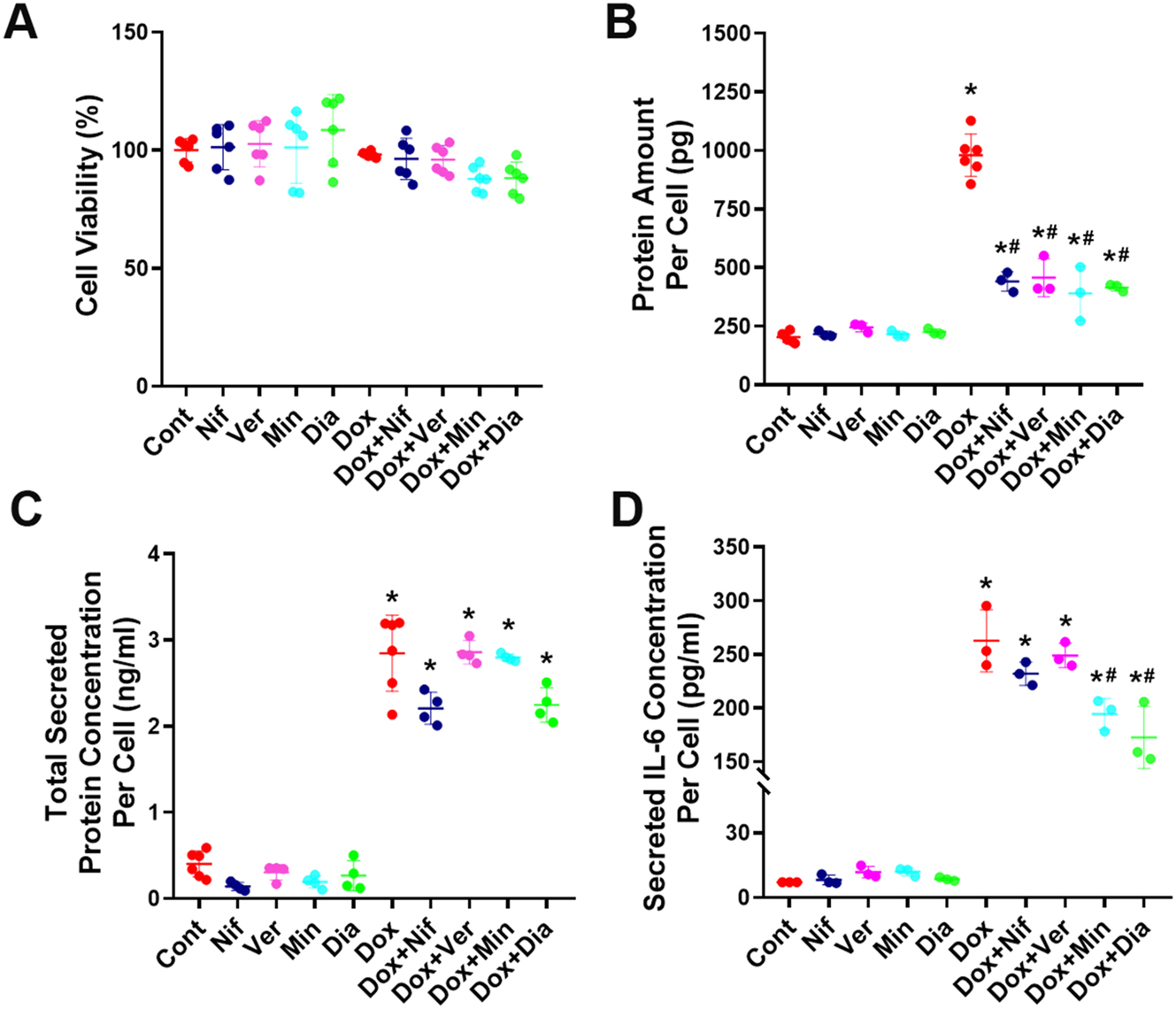

Moreover, following senescence induction, cells were treated with nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide to determine the possible cytotoxic effects of drugs. Our data demonstrate that none of these channel modulators exerted toxic effects on senescent HeLa cells (Figure 3A).

Evaluation of the effects of the L-type Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and verapamil and, the K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide on protein amounts per cell and the secretome of senescent cells. (A) Determination of the effect of nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide on cell viability in senescent and non-senescent HeLa cells (n=6). (B) Determination of the potential effects of nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide on the total protein amounts per cell in doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells (n=3). (C) Evaluation of the total protein secreted from doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells in the presence of nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide (n=4). (D) analysis of IL-6 levels, a key SASP marker, in the secretome of doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells following treatment with nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide (n=3). Cont, control; Nif, 30 µM nifedipine; Ver, 30 µM verapamil; Min, 100 µM minoxidil; Dia, 100 µM diazoxide; Dox, 300 nM doxorubicin; Dox+Nif, 300 nM doxorubicin + 30 µM nifedipine; Dox+Ver, 300 nM doxorubicin + 30 µM verapamil; Dox+Min, 300 nM doxorubicin + 100 µM minoxidil; Dox+Dia, 300 nM doxorubicin + 100 µM diazoxide. *Indicates a statistically significantly different from the control group, #indicates a significantly different from the doxorubicin group (One-Way ANOVA, p<0.05).

Evaluation of the effects of L-type Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and verapamil, and K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide on cellular protein content and the secretome of senescent cells

Total protein quantification was performed after treatment of doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells with nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, or diazoxide to determine whether these drugs altered the total protein amounts of senescent cells. Doxorubicin-induced senescence significantly increased the amount of protein per cell. This increase was significantly attenuated by all tested drugs, nifedipine, verapamil, minoxidil, and diazoxide (Figure 3B), suggesting that modulation of L-type Ca2+ and K+ ATP channels may lead to functionally relevant reductions in cellular protein content. Next, we evaluated whether L-type Ca2+ and K+ ATP channel modulators affect the SASP secreted from senescent cells. For this purpose, we measured both total protein amounts and IL-6 levels, which are considered the most common markers of SASP, in secretomes [24]. Our results showed that while doxorubicin-induced senescent cells exhibited increased total protein secretion, the presence of ion channel modulators did not significantly alter this increase (Figure 3C). However, the increased IL-6 levels observed in senescent cell secretomes were significantly reduced following treatment with minoxidil and diazoxide, whereas nifedipine and verapamil showed no notable effect on this increased secretion (Figure 3D).

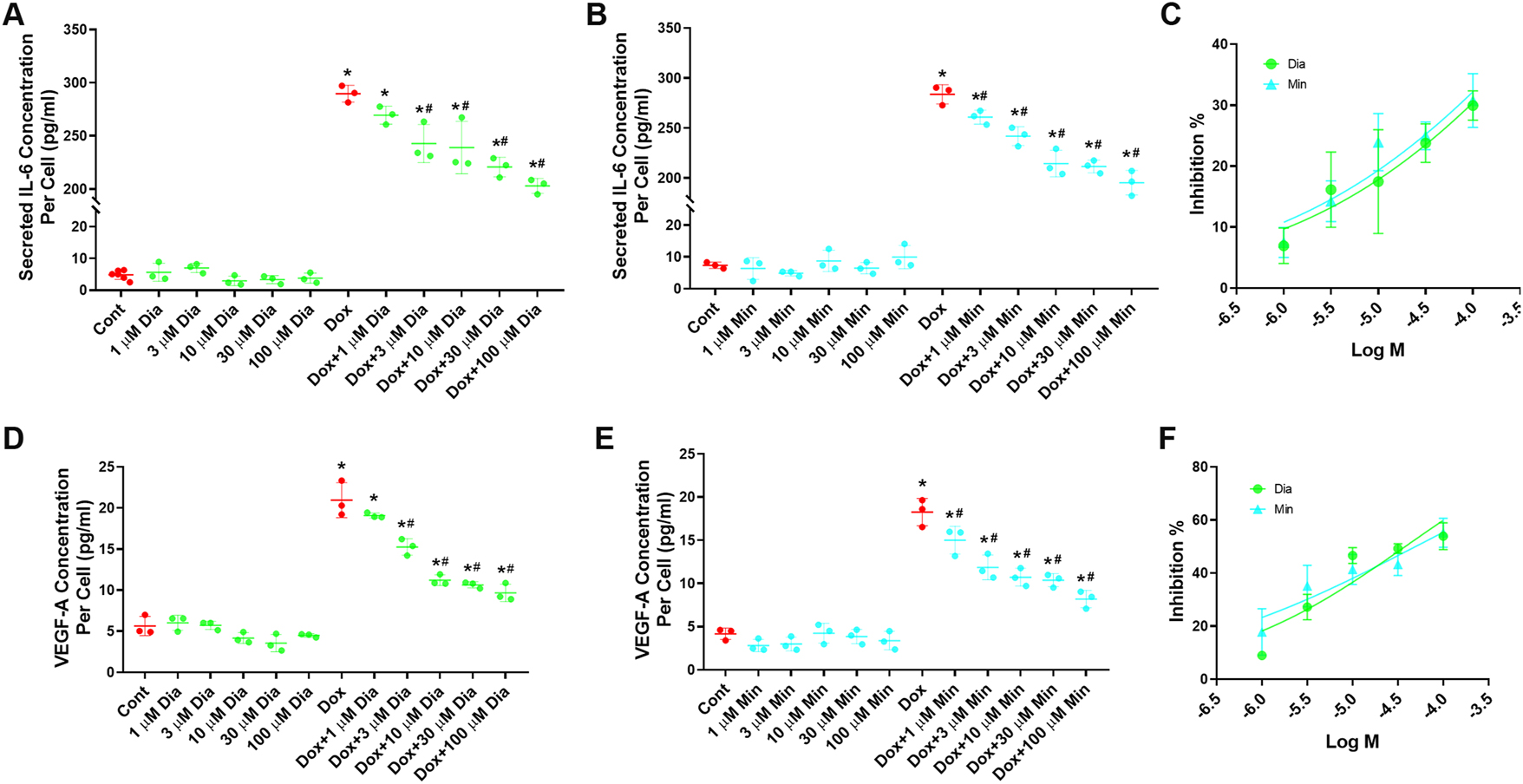

We further investigated whether the suppressive effect of minoxidil and diazoxide on IL-6 secretion from senescent cells exhibited concentration dependence. Since minoxidil exhibited toxic effects at 300 µM (Figure 1C), the impact of logarithmically lower concentrations on secretion was subsequently evaluated. Our results revealed that both minoxidil and diazoxide significantly attenuated the senescence-associated induction of IL-6 within the secretome (Figure 4A and B, and 4C). In addition, the secretion of VEGF-A, another key SASP marker, was quantified in a concentration-dependent manner, and concentration-inhibition curves were generated (Figure 4D and E, and 4F). Consistently, the treatment of minoxidil and diazoxide treatment resulted in a significant decrease of VEGF-A levels in the senescent cell secretome. Moreover, the inhibition of both IL-6 and VEGF-A secretion occurred in a concentration-dependent manner.

Evaluation of the dose-dependent effects of the K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide on the secretome of senescent cells. (A) Dose-dependent effects of diazoxide on IL-6 levels in the secretome of doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells (n=3). (B) Dose-dependent effects of minoxidil on IL-6 levels in the secretome of doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells (n=3). (C) Dose-response curves showing the effects of diazoxide and minoxidil on IL-6 levels in the secretome of doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells. (D) Dose-dependent effects of diazoxide on VEGF-A levels in the secretome of doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells (n=3). (E) Dose-dependent effects of minoxidil on VEGF-A levels in the secretome of doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells (n=3). (F) Dose-response curves showing the effects of diazoxide and minoxidil on VEGF-A levels in the secretome of doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells. Cont, control; Min, 100 µM minoxidil; Dia, 100 µM Diazoxide; Dox, 300 nM doxorubicin; Dox+Min, 300 nM doxorubicin + 100 µM minoxidil; Dox+Dia, 300 nM doxorubicin + 100 µM diazoxide. *Indicates a statistically significantly different from the control group, #indicates a significantly different from the doxorubicin group (One-Way ANOVA, p<0.05).

Evaluation of the effects of secretomes from minoxidil and diazoxide-treated senescent cancer cells on cancer cell proliferation

Since the L-type Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and verapamil did not alter the amount of SASP secreted from senescent cells, this part of the study focused solely on assessing the effects of secretomes from minoxidil- and diazoxide-treated senescent HeLa cells on cancer cell proliferation. Co-culture experiments were conducted using the xCELLigence system to investigate whether the SASP secreted from senescent cells treated with minoxidil or diazoxide affects the proliferation of non-senescent cancer cells. In this setup, senescent or non-senescent cells were seeded in the upper chambers of a transwell co-culture system, while non-senescent HeLa cells were cultured in the lower chambers for proliferation analysis. After the chambers were assembled, minoxidil or diazoxide was applied to the upper chamber. The proliferation of non-senescent HeLa cells in the lower chamber was continuously monitored via cell index values.

The secreted factors from non-senescent cells in the upper chamber caused a time-dependent decrease in the cell index values of the lower chamber non-senescent cells (Figure 5). This suggests that the secretome of non-senescent cells can reduce the proliferation and/or induce the death of other cancer cells. Notably, treatment with minoxidil and diazoxide further enhanced this suppressive effect (Figure 5). Considering that minoxidil and diazoxide have no effect on cell proliferation in HeLa cells not cultured in the transwell system, the observed decrease in proliferation in the co-culture experiments is likely not a direct effect of the drugs. Instead, it probably results from the modulation of cell secretions by these drugs.

Determination of the effects of the secretome from senescent cancer cells treated with minoxidil and diazoxide on cancer cell proliferation. NSC, non-senescent cells co-cultured with non-senescent cells; NSC+Min, non-senescent cells co-cultured with non-senescent cells treated with 100 µM minoxidil; NSC+Dia, non-senescent cells co-cultured with non-senescent cells treated with 100 µM diazoxide; SC, non-senescent cells co-cultured with 300 nM doxorubicin-induced senescent cells; SC+Min, non-senescent cells co-cultured with doxorubicin-induced senescent cells treated with 100 µM minoxidil; SC+Dia, non-senescent cells co-cultured with doxorubicin-induced senescent cells treated with 100 µM diazoxide. *Indicates statistically significant difference from the NSC group (One Way ANOVA, n=5, p<0.05).

Conversely, the factors secreted from senescent cells caused a time-dependent increase in the cell index of non-senescent cells due to cell proliferation (Figure 5). This increase in cancer cell proliferation induced by the factors secreted from senescent cells was not changed by the application of minoxidil and diazoxide (Figure 5).

Taken together, these results indicate that minoxidil and diazoxide treatment change the secretome composition of non-senescent cells in a way that reduces cancer cell proliferation, but do not show a similar effect on the content of the senescent cell secretome. This suggests that the proliferation-promoting factors secreted from senescent cells could mask the changes in the secretome composition mediating the anti-proliferative effects of minoxidil and diazoxide on non-senescent cells.

Determination of the effects of senescent cancer cell secretome treated with minoxidil and diazoxide on cancer cell migration

Wound healing assays were performed to evaluate whether the SASP secreted from senescent cells treated with minoxidil and diazoxide affects the migration of non-senescent cancer cells. For this purpose, a scratch wound was created on non-senescent HeLa cells, and conditioned media (CM) collected from senescent or non-senescent HeLa cells were applied to these cells. In addition, mitomycin C was used to inhibit cell proliferation, allowing assessment of migration ability only by calculating the percentage of wound closure at 48 h.

Although the CM from senescent cells caused a decrease in the percentage of wound closure compared to CM from non-senescent cells, this change did not reach statistical significance. Treatment with minoxidil and diazoxide did not result in a statistically significant change in the effect of CM from non-senescent cells. However, the CM from senescent cells treated with minoxidil and diazoxide significantly decreased the percentage of wound closure compared to CM from untreated senescent cells (Figure 6). This indicates that minoxidil and diazoxide alter the composition of the senescent cell CM in a way that reduces cancer cell migration.

Evaluation of the effects of senescent cancer cell secretome treated with minoxidil and diazoxide on cancer cell migration. NSC-CM: conditioned media from non-senescent cells applied to non-senescent cells; NSC+Min-CM: conditioned media from non-senescent cells treated with 100 µM minoxidil applied to non-senescent cells; NSC+Dia-CM: conditioned media from non-senescent cells treated with 100 µM diazoxide applied to non-senescent cells; SC-CM: conditioned media from doxorubicin-induced senescent cells applied to non-senescent cells; SC+Min-CM: conditioned media doxorubicin-induced senescent cells treated with 100 µM minoxidil applied to non-senescent cells; SC+Dia-CM: conditioned media doxorubicin-induced senescent cells treated with 100 µM diazoxide applied to non-senescent cells. *Indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the NSC-CM group; #Indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the SC-CM group (One Way ANOVA, n=4, p<0.05).

Discussion

Chemotherapy-induced senescent cells in the tumor microenvironment can adversely affect treatment outcomes through various mechanisms, including promoting migration and proliferation of non-senescent cancer cells and contributing to drug resistance via SASP factors [8], [9], [10]. Therefore, it is predicted that targeting SASP with therapeutic approaches as adjuvant strategies in cancer treatment may enhance therapeutic efficacy. Previous studies have demonstrated that several FDA-approved drugs, such as metformin, rapamycin, atorvastatin, and ruxolitinib, have senomorphic activity [6], 25]. As in these examples, drug repurposing may offer clinical advantages by enabling the rapid and cost-effective development and implementation of novel senotherapeutic agents.

Our data indicate that the L-type Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and verapamil, as well as the K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide, do not affect the development of senescence induced by doxorubicin in HeLa cells. Moreover, these drugs did not cause any changes in the characteristic senescent cell morphology. There are currently no reported studies directly evaluating the effects of verapamil, minoxidil, or diazoxide on the development of senescence. On the other hand, Hayashi et al. showed that nifedipine significantly inhibits high glucose-induced vascular endothelial cell senescence. In this study, the researchers determined that the anti-senescent effect of nifedipine occurs through an eNOS-dependent mechanism rather than via Ca2+ channel blockade [26]. The absence of a comparable effect of nifedipine in our study may be due to the use of HeLa cells, which are epithelial-derived cancer cells that do not display an eNOS-dependent signaling pathway [27].

We also demonstrated that both L-type Ca2+ channel blockers and K+ ATP channel openers significantly reduced the increased intracellular total protein amount in doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells. However, this decrease may not fully reflect a global suppression of protein synthesis, as the applied method did not specifically assess the incorporation of newly synthesized proteins at the ribosomal level. Interestingly, the increased total protein amounts secreted from senescent HeLa cells were not changed by L-type Ca2+ channel blockers and K+ ATP channel openers. On the other hand, the secretion of IL-6 from doxorubicin-induced senescent HeLa cells was not affected by L-type Ca2+ channel blockers, while K+ ATP channel openers reduced IL-6 levels in the secretome. An increase in SASP secreted from these cells could be expected secondary to the increase in total protein expression in senescent cells. However, our findings do not support this possibility. The fact that L-type Ca2+ channel blockers reduce the increased total intracellular protein amount in senescent cells but do not alter IL-6 secretion indicates that protein transcription and cellular secretion in senescent cells may not be directly related and that other mechanisms involved in secretion, such as vesicular transport, vesicular fusion, and cargo content, may be important.

There is no study in the literature evaluating the direct effects of K+ ATP channel openers on the secretory activity of senescent cells. However, several studies demonstrating the anti-inflammatory properties of K+ ATP channel openers suggest that they may have senomorphic potential. For instance, minoxidil has been shown to reduce the expression of interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α), which is responsible for the expression of many proinflammatory cytokines in human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells [28]. In another study, Chen Y.F. et al. reported that minoxidil suppressed paclitaxel-induced neuroinflammation in mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons [29]. Additionally, Jahandideh S. et al. demonstrated that the intraperitoneal administration of secretome obtained from diazoxide-treated (100 µM, 30 min) human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells significantly reduced systemic pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in an LPS-induced acute systemic inflammation model in mice [30].

A study that directly assessed the effects of L-type Ca2+ channel blockers on the secretory activity of senescent cells found that loperamide and niguldipine exhibited senomorphic properties in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts [31]. The authors based this conclusion on the observation that these compounds reduced the number of senescent cells without altering the total cell count in a co-culture system containing both senescent and non-senescent cells. However, this finding appears to result from the selective elimination of senescent cells while non-senescent cells continued to proliferate. Therefore, the evidence presented in that study suggests that the observed effects of L-type Ca2+ channel blockers are more consistent with senolytic rather than senomorphic activity [31]. In contrast, our findings indicate that nifedipine and verapamil, at their highest non-cytotoxic concentrations in cancer cells, did not induce senescent cell death, implying a lack of senolytic activity.

Several studies demonstrate the anti-inflammatory effects of L-type Ca2+ channel blockers. Li G. et al. demonstrated that verapamil modulated LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production in rat liver by inhibiting NF-κB activation, which resulted in decreased TNF-α and IL-6 levels and increased IL-10 expression [32]. Similarly, verapamil significantly suppressed the production of pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, superoxide, and nitric oxide) in neuron-glia cultures exposed to LPS [33]. The different cell types and senescence inducers used in all these studies may explain the different results from our study.

IL-6 and VEGF-A are widely used as SASP markers and also play an important role in promoting cancer cell proliferation and invasion in the tumor microenvironment [24]. Since our data show that diazoxide and minoxidil suppress IL-6 and VEGF-A secretions in senescent cancer cells, we evaluated whether K+ ATP channel openers alter the effects of SASP on cancer cell proliferation and migration. Our findings indicate that factors secreted by non-senescent cells treated with minoxidil and diazoxide reduced cancer cell proliferation. However, minoxidil and diazoxide were not effective on the cancer cell proliferation-enhancing effects of factors secreted by senescent cells. On the other hand, our data show that, in contrast to conditioned media from non-senescent cells, conditioned media from senescent cells treated with minoxidil or diazoxide significantly inhibited HeLa cell migration, suggesting that these drugs alter the secretory profile of senescent cells in a way that suppresses cancer cell migration.

The senomorphic effects of K+ ATP channel opener drugs may arise either directly from ion balance alterations mediated by activation of K+ ATP channels or as a consequence of their anti-inflammatory properties through suppression of cytokine expression [28], [29], [30]. A study employing in situ drug-gene-disease association predictions also demonstrated that diazoxide inhibits multiple kinase genes [34]. Although this was not shown for minoxidil, multiple kinase gene inhibition may also be one of the reasons for the senomorphic effect of these drugs.

Several studies suggest that the K+ ATP channel openers minoxidil and diazoxide may have therapeutic potential in cancer treatment. Fukushiro-Lopes D. et al. demonstrated that minoxidil suppresses ovarian cancer cell proliferation and induces apoptotic cell death both in vitro and in vivo [35]. Furthermore, a single-center phase II clinical trial is currently underway to evaluate the efficacy and safety of minoxidil in the treatment of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (NCT05272462). Qiu S. et al. showed that minoxidil (50 µM) did not affect breast cancer cell proliferation but significantly reduced cancer cell invasion [36]. It is plausible that, in addition to these reported effects, the suppressive effects of K+ ATP channel openers on SASP may also contribute to their antitumor activity.

The therapeutic plasma concentrations of minoxidil and diazoxide in the clinical management of hypertension are approximately 0.3 µM [37] and 160 µM [38], respectively. In the context of our experimental conditions, the concentration of diazoxide at which a senomorphic effect was observed remained below its reported therapeutic plasma level. This observation suggests that diazoxide may represent a more suitable candidate for adjuvant application in cancer therapy, as its efficacy at sub-therapeutic concentrations is less likely to be associated with adverse systemic effects.

Conclusions

In our current study, we suggest that minoxidil and diazoxide, which are FDA-approved and chronically used drugs, have the potential to be used as adjuvants to chemotherapy for senomorphic purposes. If their senomorphic effects are further supported by in vivo and clinical studies, the clinical application of minoxidil and diazoxide in this context may become feasible. Additionally, K+ ATP channels emerge as promising targets for senotherapeutic intervention.

Funding source: The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey

Award Identifier / Grant number: 122S564

Funding source: The Scientific Project Unit of Gazi University

Award Identifier / Grant number: TKB-2021-7385

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was supported by the Scientific Project Unit of Gazi University (Grant number TKB-2021-7385) and TUBITAK (Grant number: 122S564).

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Hayflick, L, Moorhead, PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res 1961;25:585–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Campisi, J. Cellular senescence as a tumor-suppressor mechanism. Trends Cell Biol 2001;11:S27–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02151-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Simay, YD, Ozdemir, A, Ibisoglu, B, Ark, M. The connection between the cardiac glycoside-induced senescent cell morphology and Rho/Rho kinase pathway. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2018;75:461–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/cm.21502.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Hernandez-Segura, A, Nehme, J, Demaria, M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol 2018;28:436–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Simay Demir, YD, Ozdemir, A, Sucularli, C, Benhur, E, Ark, M. The implication of ROCK 2 as a potential senotherapeutic target via the suppression of the harmful effects of the SASP: do senescent cancer cells really engulf the other cells? Cell Signal 2021;84:110007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Ozdemir, A, Simay Demir, YD, Yesilyurt, ZE, Ark, M. Senescent cells and SASP in cancer microenvironment: new approaches in cancer therapy. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2023;133:115–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apcsb.2022.10.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Sucularli, C, Simay Demir, YD, Ozdemir, A, Ark, M. Temporal regulation of gene expression and pathways in chemotherapy-induced senescence in HeLa cervical cancer cell line. Biosystems 2024;237:105140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystems.2024.105140.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Ewald, JA, Desotelle, JA, Wilding, G, Jarrard, DF. Therapy-induced senescence in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1536–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq364.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Wang, B, Kohli, J, Demaria, M. Senescent cells in cancer therapy: friends or foes? Trends Cancer 2020;6:838–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2020.05.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Nelson, G, Wordsworth, J, Wang, C, Jurk, D, Lawless, C, Martin-Ruiz, C, et al.. A senescent cell bystander effect: senescence-induced senescence. Aging Cell 2012;11:345–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00795.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Liu, H, Zhao, H, Sun, Y. Tumor microenvironment and cellular senescence: understanding therapeutic resistance and harnessing strategies. Semin Cancer Biol 2022;86:769–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.11.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Abdul Kadir, L, Stacey, M, Barrett-Jolley, R. Emerging roles of the membrane potential: action beyond the action potential. Front Physiol 2018;9:1661. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01661.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Rorsman, P, Trube, G. Glucose dependent K+-channels in pancreatic beta-cells are regulated by intracellular ATP. Pflügers Archiv 1985;405:305–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00595682.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Ashcroft, FM, Rorsman, P. ATP-sensitive K+ channels: a link between B-cell metabolism and insulin secretion. Biochem Soc Trans 1990;18:109–11. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst0180109.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Rorsman, P, Salehi, SA, Abdulkader, F, Braun, M, MacDonald, PE. K(ATP)-channels and glucose-regulated glucagon secretion. Trends Endocrinol Metabol 2008;19:277–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2008.07.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Sudhof, TC. Calcium control of neurotransmitter release. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 2012;4:a011353. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a011353.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Vazquez-Sanchez, AY, Hinojosa, LM, Parraguirre-Martinez, S, Gonzalez, A, Morales, F, Montalvo, G, et al.. Expression of K(ATP) channels in human cervical cancer: potential tools for diagnosis and therapy. Oncol Lett 2018;15:6302–8. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.8165.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Jacquemet, G, Baghirov, H, Georgiadou, M, Sihto, H, Peuhu, E, Cettour-Janet, P, et al.. L-type calcium channels regulate filopodia stability and cancer cell invasion downstream of integrin signalling. Nat Commun 2016;7:13297. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13297.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Özdemir, A, Ibisoglu, B, Simay, YD, Polat, B, Ark, M. Ouabain induces rho-dependent rock activation and membrane blebbing in cultured endothelial cells. Mol Biol (Mosc) 2015;49:138–43. https://doi.org/10.1134/s0026893315010136.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Ozdemir, A, Ibisoglu, B, Simay Demir, YD, Benhur, E, Valipour, F, Ark, M. A novel proteolytic cleavage of ROCK 1 in cell death: not only by caspases 3 and 7 but also by caspase 2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021;547:118–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.02.024.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Simay Demir, YD, Ozdemir, A, Ozdemir, RG, Cevher, SC, Caliskan, B, Ark, M. Antimigratory effect of pyrazole derivatives through the induction of STAT1 phosphorylation in A549 cancer cells. J Pharm Pharmacol 2021;73:808–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpp/rgab022.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Coetzee, WA. Multiplicity of effectors of the cardioprotective agent, diazoxide. Pharmacol Ther 2013;140:167–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.06.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Veytia-Bucheli, JI, Alvarado-Velazquez, DA, Possani, LD, Gonzalez-Amaro, R, Rosenstein, Y. The Ca(2+) channel blocker verapamil inhibits the in vitro activation and function of T lymphocytes: a 2022 reappraisal. Pharmaceutics 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14071478.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Fisher, DT, Appenheimer, MM, Evans, SS. The two faces of IL-6 in the tumor microenvironment. Semin Immunol 2014;26:38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Zhang, L, Pitcher, LE, Prahalad, V, Niedernhofer, LJ, Robbins, PD. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS J 2023;290:1362–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.16350.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Hayashi, T, Yamaguchi, T, Sakakibara, Y, Taguchi, K, Maeda, M, Kuzuya, M, et al.. eNOS-dependent antisenscence effect of a calcium channel blocker in human endothelial cells. PLoS One 2014;9:e88391. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088391.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. TheHumanProteinAtlas. https://www.proteinatlas.org; 2025. Available from: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000164867-NOS3/cell+line.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Pekmezci, E, Turkoglu, M, Gokalp, H, Kutlubay, Z. Minoxidil downregulates Interleukin-1 alpha gene expression in HaCaT cells. Int J Trichol 2018;10:108–12. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijt.ijt_18_17.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Chen, YF, Chen, LH, Yeh, YM, Wu, PY, Chen, YF, Chang, LY, et al.. Minoxidil is a potential neuroprotective drug for paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Sci Rep 2017;7:45366. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45366.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Jahandideh, S, Khatami, S, Eslami Far, A, Kadivar, M. Anti-inflammatory effects of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells secretome preconditioned with diazoxide, trimetazidine and MG-132 on LPS-induced systemic inflammation mouse model. Artif Cells, Nanomed Biotechnol 2018;46:1178–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2018.1481862.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H, Ling, YY, Zhao, J, McGowan, SJ, Zhu, Y, Brooks, RW, et al.. Identification of HSP90 inhibitors as a novel class of senolytics. Nat Commun 2017;8:422. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00314-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Li, G, Qi, XP, Wu, XY, Liu, FK, Xu, Z, Chen, C, et al.. Verapamil modulates LPS-Induced cytokine production via inhibition of NF-kappa B activation in the liver. Inflamm Res 2006;55:108–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-005-0060-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Liu, Y, Lo, YC, Qian, L, Crews, FT, Wilson, B, Chen, HL, et al.. Verapamil protects dopaminergic neuron damage through a novel anti-inflammatory mechanism by inhibition of microglial activation. Neuropharmacology 2011;60:373–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Wang, A, Lim, H, Cheng, SY, Xie, L. ANTENNA, a multi-rank, multi-layered recommender system for inferring reliable drug-gene-disease associations: repurposing diazoxide as a targeted anti-cancer therapy. IEEE ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinf 2018;15:1960–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcbb.2018.2812189.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Fukushiro-Lopes, D, Hegel, AD, Russo, A, Senyuk, V, Liotta, M, Beeson, GC, et al.. Repurposing Kir6/SUR2 channel activator minoxidil to arrests growth of gynecologic cancers. Front Pharmacol 2020;11:577. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00577.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Qiu, S, Fraser, SP, Pires, W, Djamgoz, MBA. Anti-invasive effects of minoxidil on human breast cancer cells: combination with ranolazine. Clin Exp Metastasis 2022;39:679–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-022-10166-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Werning, C. The effect of minoxidil on blood pressure and plasma renin activity in patients with essential and renal hypertension. Klin Wochenschr 1976;54:727–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01470464.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Ogilvie, RI, Nadeau, JH, Sitar, DS. Diazoxide concentration-response relation in hypertension. Hypertension 1982;4:167–73. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.4.1.167.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/tjb-2025-0249).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Pregnancy associated plasma protein-A: a promising biomarker in kidney diseases

- Research Articles

- Potential of the FOX gene family and LncRNAs as biomarkers in differentiated thyroid cancer treated with I-131

- Does modifying energy metabolism alter cellular signaling and proliferation in KRAS mutant NSCLCs?

- To investigate the action mechanism of lncRNA CDKN2B-AS1/hsa-miR-134-5p/CCND1 axis in cervical cancer based on bioinformatics

- Dysregulation of miR-709 in diabetic kidney disease and its role in inflammatory response

- The possible link between endocannabinoid system gene polymorphisms and overweight/obesity susceptibility in individuals living in the Marmara Region

- Homocysteine induces iNOS and oxLDL accumulation in murine immune cells

- Novel prostaglandin and isoprostane panel for evaluating Wilson’s Disease

- miR-15b-5p affects the innate immune response through PAQR3 in patients with reflux esophagitis

- MiR-26b-5p and its association with inflammatory markers in infants and toddlers with bronchiolitis and respiratory symptoms

- LncRNA MALAT1 regulates the inflammatory response of dry eye disease via sponging miR-302d

- Awareness and knowledge levels of patients regarding pre-analytical errors

- Comparison between free light chains and immunofixation electrophoresis: one-year data from a tertiary hospital

- Geniposide effect on cardiac zinc level, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in rats with obesity-linked heart injury

- Xanthohumol inhibits extracellular matrix degradation via the Nrf2/PERK/ATF4/C/EBPβ pathway in osteoarthritis

- Targeting SASP with FDA-approved agents: minoxidil and diazoxide as potential senomorphic agents in cancer therapy

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Pregnancy associated plasma protein-A: a promising biomarker in kidney diseases

- Research Articles

- Potential of the FOX gene family and LncRNAs as biomarkers in differentiated thyroid cancer treated with I-131

- Does modifying energy metabolism alter cellular signaling and proliferation in KRAS mutant NSCLCs?

- To investigate the action mechanism of lncRNA CDKN2B-AS1/hsa-miR-134-5p/CCND1 axis in cervical cancer based on bioinformatics

- Dysregulation of miR-709 in diabetic kidney disease and its role in inflammatory response

- The possible link between endocannabinoid system gene polymorphisms and overweight/obesity susceptibility in individuals living in the Marmara Region

- Homocysteine induces iNOS and oxLDL accumulation in murine immune cells

- Novel prostaglandin and isoprostane panel for evaluating Wilson’s Disease

- miR-15b-5p affects the innate immune response through PAQR3 in patients with reflux esophagitis

- MiR-26b-5p and its association with inflammatory markers in infants and toddlers with bronchiolitis and respiratory symptoms

- LncRNA MALAT1 regulates the inflammatory response of dry eye disease via sponging miR-302d

- Awareness and knowledge levels of patients regarding pre-analytical errors

- Comparison between free light chains and immunofixation electrophoresis: one-year data from a tertiary hospital

- Geniposide effect on cardiac zinc level, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in rats with obesity-linked heart injury

- Xanthohumol inhibits extracellular matrix degradation via the Nrf2/PERK/ATF4/C/EBPβ pathway in osteoarthritis

- Targeting SASP with FDA-approved agents: minoxidil and diazoxide as potential senomorphic agents in cancer therapy

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment