Abstract

Objectives

Autonomic regulation has been identified as a potential regulator of pain via vagal nerve mediation, assessed through heart rate variability (HRV). Non-invasive vagal nerve stimulation (nVNS) and heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB) have been proposed to modulate pain. A limited number of studies compare nVNS and HRVB in persons with chronic pain conditions. This systematic review compared interventions of nVNS and HRVB in adults with long-standing pain conditions.

Methods

PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, Google Scholar, and Cochrane library were used to retrieve the randomized controlled trials for this review between the years 2010 and 2023. Search terms included chronic pain, fibromyalgia, headache, migraine, vagus nerve stimulation, biofeedback, HRV, pain assessment, pain, and transcutaneous.

Results

Ten full-text articles of 1,474 identified were selected for full qualitative synthesis, with a combined population of 813 subjects. There were n = 763 subjects in studies of nVNS and n = 50 subjects for HRVB. Six of the nine nVNS studies looked at headache disorders and migraines (n = 603), with two investigating effects on fibromyalgia symptoms (n = 138) and one the effects on chronic low back pain (n = 22). Of the nVNS studies, three demonstrated significant results in episode frequency, six in pain intensity (PI) reduction, and three in reduced medication use. The HRVB study showed statistically significant findings for reduced PI, depression scores, and increased HRV coherence.

Conclusion

Moderate to high-quality evidence suggests that nVNS is beneficial in reducing headache frequency and is well-tolerated, indicating it might be an alternative intervention to medication. HRVB interventions are beneficial in reducing pain, depression scores, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication, and in increasing HRV coherence ratio. HRVB and nVNS appear to show clinical benefits for chronic pain conditions; however, insufficient literature exists to support either approach.

1 Introduction

Chronic pain conditions can have a negative impact on an individual’s quality of life with increased time lost from work resulting in lower production, often accompanied by an elevated financial burden [1,2,3]. As the prevalence increases [4,5,6] conservative financial estimates are in the billions of dollars in European and North America countries [5,7–9]. Therefore, finding non-pharmacological interventions that may complement medical use or be an alternative is vital for addressing the problem of chronic pain.

Chronic pain persisting for 3 months or longer has been associated with autonomic dysfunction, which contributes to increased resting heart rate and reduced heart rate variability (HRV) [10]. In many cases, long-standing pain induces an imbalance of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in which there is increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and decreased activity of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) [10,11]. This imbalance reduces the flexibility of the ANS adaptive response to various threats of physical or emotional pain [12] and is suspected of playing a key role in pain persistence. The imbalances are evidenced by self-reports of increased pain and disability. Because of this connection between HRV, ANS, and long-standing conditions, it may be a reliable objective metric for assessing the health of the SNS and PNS stress response [10,11].

An important link between the cardiovascular system and pain regulation mechanisms is the vagus nerve [13]. Pain control occurs through vagally mediated afferent and efferent stimuli [13]. The vagus nerve is also known to modulate the ANS [13]. Impaired vagal tone can be directly measured through the assessment of HRV [10]. Treatments affecting vagally mediated pain control includes non-invasive vagal nerve stimulation (nVNS) and heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB). To date there is no research comparing the effects of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) to HRVB interventions attempting to affect autonomic pain control processes in persons with chronic pain conditions. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to evaluate randomized control trials (RCTs) to assess the effectiveness of nVNS vs HRVB in the treatment of chronic pain conditions.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategy

Electronic database searches were conducted through PubMed, Cochrane, MEDLINE, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, and Google Scholar. The bibliographies of the collected studies were reviewed for further references applicable to this systematic review. The search was performed to identify all relevant published randomized controlled trials written in English, over the past 13 years (January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2023). An initial search was conducted on May 30, 2020, with a second search completed on October 29, 2024, during which the four review authors conducted a search with established search terms using a combination of keywords ranging from “chronic pain” or “fibromyalgia” or “headache disorder” or “migraine disorder” or “heart rate variability” or “biofeedback” or “vagus nerve stimulation” or “transcutaneous” or “pain assessment.” A full list of all search term strategies for each database are provided in the supplemental materials (Table A1).

2.2 Study selection

The protocol was developed a priori. All titles and abstracts were independently reviewed for inclusion or exclusion [14]. Inclusion criteria were expansively planned to capture all relevant literature, including unpublished (i.e., grey literature and dissertations), in order to minimize reviewer bias [15]. To further limit bias, quality assessment metrics were used, studies with plainly defined data management strategies with specific synthesis reporting metrics were included, and systematically appraising for risk of bias are mitigation strategies that were utilized.

Inclusion criteria included (1) ages of 18–65 years with chronic pain conditions more than 3 months, (2) studies with a randomized controlled design, (3) a treatment consisting of nVNS intervention, (4) a comparison utilizing HRVB, (5) a primary outcome using a validated pain intensity (PI) metric, and (6) a secondary outcome using a validated functional disability measure and HRV metric. Exclusion criteria included studies that were non-English, studies prior to 2010, studies related to non-human, where the participants had a progressive disease, were post-operative or had a surgically implanted vagus nerve stimulator, or had a traumatic brain injury, concussion, brain tumor, spinal cord injury, seizure disorder, and visceral pain. Titles and abstracts were screened for the inclusion and exclusion criteria and full text were retrieved and assessed if the initial screen was not clear. Duplicate articles were then removed. Discrepancies over trial inclusion were discussed between the authors. Trials were excluded if they failed to meet the inclusion criteria previously described. None of the review authors were blinded to each reviewed manuscripts authors, institutions, or results during assessment for inclusion or exclusion but were blinded to each other’s individual data extraction.

2.3 Data collection process

The results of the literature search and study selection were independently evaluated by three evaluators (K.P., J.H., and P.T.) examining article title, abstracts, and keywords during the initial screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Duplicate citations from the multiple databases were then removed. Afterwards, selected articles were obtained for full-text review. In cases of disagreement, a fourth reviewer (B.H.) was consulted. The complete data collection procedure is shown as a flowchart (Figure 1).

PRISMA flow diagram. *Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. Source: Page MJ, et al. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

2.4 Selected manuscript details

2.4.1 Participants

Participants included in this review were of all genders, between the ages of 18 and 65 with pain for longer than 3 months duration [16,17]. The chronic pain populations included in this review had chronic pain, fibromyalgia, migraines, or headache disorders [16,17].

2.4.2 Types of interventions

The interventions included in this review were any nVNS treatment and any HRVB interventions on chronic pain conditions [10]. Excluded interventions include any other type of biofeedback and any invasive vagus nerve treatment [10].

2.4.3 Description of the intervention

Descending inhibitory pain control processes are impaired in persons with chronic pain [13]. It is hypothesized that when impaired parasympathetic control (vagal dysfunction) occurs, it is primarily due to impaired descending control processes [13]. HRVB is an intervention which attempts to restore ANS function by achieving “HRV coherence” [18]. The participants’ heartbeat is presented to them while they breathe slowly, trying to match a particular, normal heart rate pattern called respiratory sinus arrhythmia [18]. HRVB has received increasing attention for its promising results in pain modulation [19].

Recent studies have also explored nVNS as a novel treatment option for pain conditions. nVNS is direct, noninvasive stimulation of the vagal afferent descending pain control pathway and modulates ANS activity [20–22]. The literature has demonstrated a benefit in the use of nVNS on pain reduction.

2.4.4 Eligible intervention comparisons

Eligible intervention comparisons include (1) the nVNS with conventional treatment (e.g., analgesics) vs conventional treatment alone; nVNS vs placebo; and nVNS vs other non-pharmacological modalities for managing pain. (2) The HRVB with conventional treatment (e.g., analgesics) vs conventional treatment alone; HRVB vs placebo; and HRVB vs other non-pharmacological modalities for managing pain.

2.5 Outcome measures

2.5.1 Primary

Primary outcome measures include (a) moderate pain relief (PR) described as 30% PR over baseline with substantial PR >50% PR over baseline [23]; (b) PI, as assessed by the visual analog scale (VAS) or any validated assessment tool for measuring PI; and (c) pain episode frequency for migraine episodes and chronic pain or fibromyalgia flare-ups.

2.5.2 Secondary

Secondary outcome measures include (a) changes in opioid and analgesic consumption frequency with pain episodes; (b) changes in pain-related disability, as assessed by the beck depression inventory, or any other validated assessment tool for measuring pain-related disability; and (c) any reported adverse events.

2.6 Data extraction and management

All data extraction procedures were conducted according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 [14]. The researchers independently extracted data from included articles. After independent review, the researchers then met to discuss any differences in the individual data extraction as a team, verifying each other’s review of the extracted data. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion amongst the authors and a fourth author, if needed. Qualitative data were extracted, compiled, and synthesized using a data extraction form that was designed by the authors following the “Checklist of items to consider in data collection” in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [14] (Table 1). Meta-analysis was not performed due to the limited amount of quality evidence for HRVB for chronic pain. Differences in outcome reporting between studies prevented synthesis of p-values between included studies.

Data synthesis

| Author | Design/study | Participants/setting/time | Intervention/comparison | Outcome measures | Results | HOV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Pain | ||||||

| Winstead [33] | RCT | M/F/Veterans/ages 43–65/VA hospital, SC/16 weeks | I: HRVB; C: sham | PI; Meds*; D | PI: ES −0.66, p = 0.05; Meds: not significant; D: −4.82 (95% CI: −5.34, −4.30) p = 0.02; ES 0.6 | Not significant except for race p = 0.04 |

| Cluster HA (significant results are for episodic cluster headaches only) | ||||||

| Gaul et al. [22] | RCT | M/F/ages 18–70/10 European sites/4 weeks | I: nVNS; C: SOC | PI; PR; PF; Meds | PI: 8.93 (95% CI: 0.47, 17.39 points); p = 0.039; PF: 3.9 (95% CI: 0.5, 7.2) p = 0.02; PR: 32% greater PR than controls (p = 0.001); Meds: −15 (95% CI: −22.8, −7.2) p < 0.001 | Not reported |

| Goadsby et al. [28] | RCT | M/F/age >18/4 European countries/9 sites | I: nVNS; C: sham | PI; PR | PI: 42% greater change than controls (p < 0.01); PR: 15% greater PR than controls (p = 0.05) | Not reported |

| Silberstein et al. [30] | RCT | M/F 18–75/20 U.S. centers (university, medical centers, clinics)/1 month OR until 5 CH treated | I: nVNS C: 1 Hz sham | PI; PR; Meds* | PI: p = 0.008; PR: total: nVNS, 2.1 [95% CI: 1.8, 2.3]; sham, 2.0 [95% CI: 1.8, 2.2]; p = 1.0) Meds: p = 0.15 | Not reported |

| Fibromyalgia | ||||||

| Kutlu et al. [32] | RCT | F/ages 18–50/Beykoz Public Hospitals dept. of PT and rehab/4 weeks | I: nVNS & exercise; C: exercise | PI; D | PI: p ≤ 0.001 D: p ≤ 0.001 | HOV not significant except 3 measures of SF-36 (physical function p = 0.023, Social functionality p = 0.021, pain p = 0.018) |

| Paccione et al. [36] | RCT | M/F 18–65 Oslo hospital 2 weeks | I: tVNS and Breathing | PI | tVNS results: | Tx group similar characteristics for cardioactive medication use, but diff for hormonal contraceptive use. HOV statistical test not provided |

| FMS | PI tVNS group: (−0.82; 95% CI: −1.32−0.31) | |||||

| CVR | P < 0.001 for widespread, average, and current pain. | |||||

| FM: P < 0.001 | ||||||

| CVR: No statistical diff | ||||||

| Low Back Pain | ||||||

| Uzlifatin et al. [37] | RCT | M/F/ages 18–55/Indonesia/3–12 mo LBP/2 weeks | I: nVNS and exercise; C: exercise | D | D: p = 0.001 | HOV not significant for PI, D, HDRS |

| Migraine | ||||||

| Chaudhry et al. [21] | RCT | M/F/ages 27–66/Belgium/8 weeks | I: nVNS; C: Sham | PI; PF | PI : p > 0.05 (not significant) PF: p = 0.049 (severe attacks only) | Not reported |

| Grazzi et al. [29] | RCT | M/F/ages 18–75/10 France centers/4 weeks | I: nVNS; C: Sham | PI; PF; Meds | PI: p = 0.002: PF: p = 0.037; Meds: p = 0.008 | Not reported |

| Straube et al. [31] | RCT | M/F/ages 18–70/1 Outpatient clinic/12 weeks | I: nVNS 25 Hz; C: nVNS 1 Hz | PI*; PF* | PI: p > 0.05 (not significant) PF: p = 0.094 | Not significant |

Note. *Non-significant findings. Abbreviations: RCT, randomized control trial; M/F, males/females; VA, veterans; SC, South Carolina; I, intervention; C, comparison; HOV, homogeneity of variance; PI, pain intensity; ES, effect size; Meds, medication use; D, disability; PF, pain frequency; PR, pain relief; SOC, Standard of care; CH, cluster headache; FMS, Fibromyalgia Severity; CVR, Cardio-vagal response; tVNS, transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation.

2.7 Quality assessment

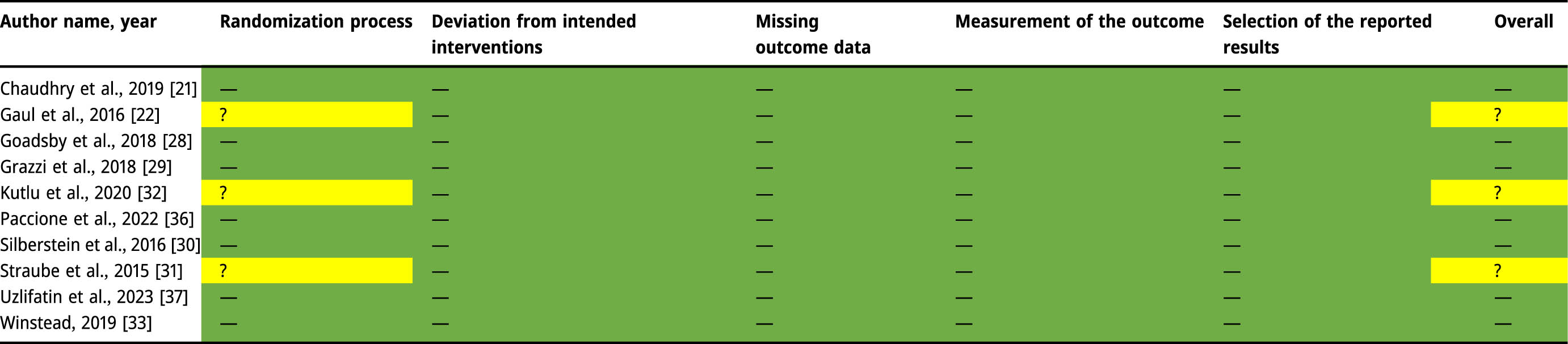

The Revised Tool to Assess Risk of Bias (RoB 2) in Randomized Trials is the recommended tool to assess risk of bias for Cochrane reviews [24]. The RoB 2 was used to collect and assess the risk of bias data [25]. It functions by answering a series of signaling questions with yes, probably yes, probably no, no, or no information. These answers are then interpreted through an algorithm to create a risk of bias judgement which is proposed on a judgement scale of “low,” “some concerns,” or “high risk” of bias. Five domains are assessed with a series of signaling questions in each domain. These domains include: “(1) risk of bias arising from the randomization process, (2) risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions, (3) risk of bias due to missing outcome data, (4) risk of bias in measurement of the outcome, and (5) risk of bias in selection of the reported result” [25]. Three authors independently reviewed the risk of bias of included trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention [26]. Any disagreements over the risk of bias assessment were discussed and resolved amongst the three review authors (KP, JH, and PT), and a fourth reviewer (BH), as necessary (Table 2).

Assess risk of bias in randomized trials (RoB 2)

|

Green: Low Risk of bias (–); Yellow: Some Concern for risk of bias (?); Red: High Risk of bias (+).

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

The search strategy returned 1,474 articles with 236 references from PubMed, 224 references from Cochrane, 3 references from websites (e.g., Google Scholar), and 1,011 references from MEDLINE, CINAHL, and SportDiscus. A total of 531 duplicates were removed from this initial search. The titles and abstracts were screened (n = 961) and 932 were excluded based on not meeting inclusion or exclusion criteria. A total of 29 articles were sought for retrieval and all received full-text review for eligibility. Of these, 19 were excluded, leaving 10 RCTs included for review with level 2 evidence according to Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (Figure 1). PRISMA Checklist is available in the Appendix (Table A2).

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

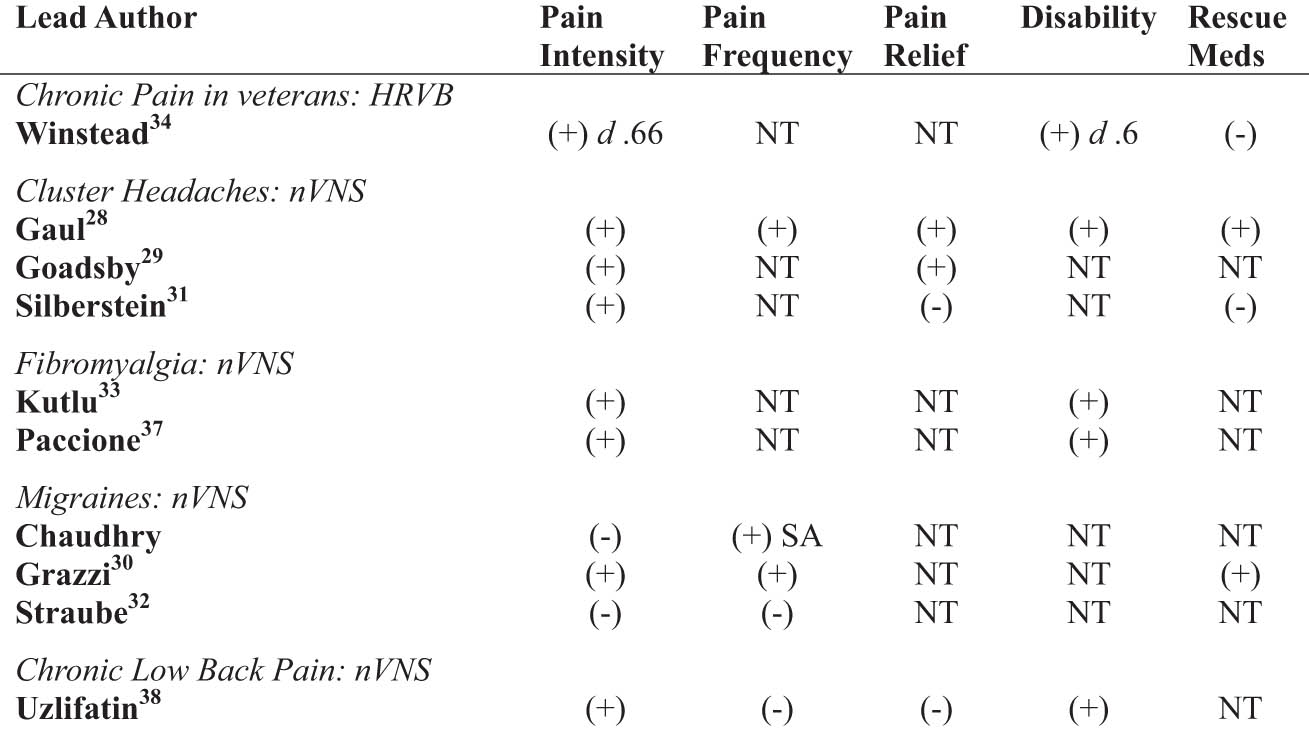

The systematic review consisted of ten RCTs. The total number of patients within the 10 articles yielded 813 subjects. There were n = 763 subjects in studies of nVNS and n = 50 subjects for one HRVB RCT. Six of the nine nVNS studies looked at headache disorders and migraines (n = 603) [21,27–31] with two investigating effects on fibromyalgia symptoms (n = 138) [32,36] and one for chronic low back pain (n = 22) [37]. Of the studies evaluating nVNS, three demonstrated significant results in episode frequency [21,27,29], six in PI reduction [27–30,32,37], and two in reduced medication use [27,29]. One study showed significant findings for reduced PI, depression scores, and increased HRV coherence [33]. Adverse effects of nVNS included skin irritation at the application site, facial twitching, tingling or pulling, and chest discomfort [30,31,37]. There were no negative effects reported in the use of HRVB [33]. Findings for the primary and secondary outcomes are listed in Figure 2.

Summary of results by outcomes. Note. (+), p value <0.05; (−), p value >0.05, NT = not tested; SA, serious attacks.

A detailed presentation of key elements for each included manuscript for each outcome measures and significant values are presented in Table 1. Furthermore, comprehensive information from each manuscript was extracted from each article and was recorded in detail. This detailed information for each included article is available in the supplemental materials (Table A3).

3.3 Summary of quality of results and risk of bias

The overall quality of the evidence extracted for use in this review was “moderate,” indicating that there is a moderate chance that the true effect has been reported [34]. A total of seven studies had “low risk” and three studies had “some concern.” A score of “moderate-quality” evidence for three nVNS studies were assigned “some concern” due to limited reporting on randomization [27,31,32] while HRVB intervention study had a “low” risk of bias [33]. There were zero studies that were assigned high risk. Results were recorded and individually summarized for RoB 2, which are presented in Table 2.

3.4 Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Despite a number of pilot studies evaluating the effects of HRVB for the treatment of chronic pain conditions, only one RCT was identified and included in this review. This study included 50 veterans that completed the follow-up assessment, ages 43–65 [33]. The quality of this study was considered high due to low concerns in methodological quality and complete reporting of the data [34]. PI was extracted from this RCT as it is a subset of the brief pain inventory. Secondary outcomes in this study included pain medication use and the beck depression index. More research in HRVB for chronic pain conditions is warranted to identify clinical applicability, although the quality of evidence in this trial is high, no other RCTs were identified evaluating HRVB.

For nVNS, a majority of the RCTs included in this review investigated nVNS in the management of headache disorders [21,27–31]. Two RCTs explored the benefits of nVNS compared to exercise for fibromyalgia [32,36] and one for chronic low back pain [37].

The included trials on nVNS and migraines were three studies that comprised a total n = 327 subjects between the ages of 18 and 75 [21,29,31]. Two of these studies [29,31] had a moderate quality of evidence due to “some concerns” regarding methodological quality, and complete reporting of data [34]. Primary outcome data extracted for this review included PR, PI, and pain episode frequency. While improvements in PI were reported to be significant by Grazzi et al. [29] (p = 0.002), improvements in PI were not significant in the other two studies (p > 0.05). While frequency of pain episodes was reported to be not significant by Straube et al. [31] (p = 0.094), improvements in pain frequency (PF) were reported by Grazzi et al. [29] (p = 0.03). Chaudhry et al. [21] reported a significant improvement in the frequency of severe episodes only (p = 0.049). Of the three studies, the study of Grazzi et al. [29] was the only study to report on the secondary outcome of rescue medication use, finding a statistically significant reduction in medication use (p = 0.008).

Three RCTs evaluating the effect of nVNS on cluster headaches (CH) studied n = 276 subjects between the ages of 18 and 75 [27,28,30]. There were “some concerns” regarding methodological quality and complete reporting of data for one study [27], resulting in moderate-quality [34]. Primary outcome assessment information extracted for this review included PR, PI, and pain episode frequency. Extracted secondary outcome data included changes in medication consumption.

The study by Gaul et al. was the only research on CH to report on frequency of pain episodes, noting 3.9 fewer attacks per week (95% CI: 0.5, 7.2; p = 0.02). In the studies by Gaul et al. [27], Goadsby et al. [28], and Silberstein et al. [30], significant reductions were reported in PI (8.93 [95% CI: 0.47, 17.39 points], p = 0.039; 42%, p < 0.01; and p = 0.008, respectively), and PR (32%, p = 0.001; 15% greater than controls p = 0.05; and 2.1 [95% CI: 1.8, 2.3], respectively). Conflicting results were reported for the secondary outcome measure of medication consumption by Gaul et al. [27] (−15 [95% CI: −22.8, −7.2] p < 0.001) and Silberstein et al. [30] (p = 0.15).

The included trials on nVNS and fibromyalgia examined n = 138 subjects between the ages of 18 and 65 [32,36]. The methodological quality of one trial had “some concerns” and reporting was complete, resulting in moderate-quality data [32]. Primary outcome assessments included PI, PR, the Beck Depression Inventory, symptom severity, and pain index [32,36].

3.5 Migraines

For the treatment of migraines, Straube et al. [31] used nVNS at the auricular branch of the vagus nerve with a frequency of 25 Hz for the treatment group and 1 Hz for the active controls. The study included both males and females, 18–70 years of age. The RCT found that the control group at 1 Hz was significant for reducing >50% of headache frequency compared to the 25 Hz group. No statistically significant changes in PI were found in the control or intervention group. Both groups (1 Hz and 25 Hz) significantly reduced depression scales and use of medication, with no statistical significance between groups.

Chaudhry et al. [21] assessed the use of nVNS at the cervical branch of the vagus nerve for migraine intervention, compared to age matched controls. The study included both males and females, 27–66 years of age. The nVNS group only had significant results for reduced PF of severe migraine attacks. There were no significant findings for changes in PI and PR. Disability and medication usage were not assessed. A limitation of this study was that all but one participant were female, and literature shows males and females have different pain and HRV responses [17].

Grazzi et al. [29] performed a post-hoc analysis of nVNS at an unspecified frequency to the cervical branch of the vagus nerve in migraines compared to a sham group. The study included both males and females between 18 and 65 years of age. Significant findings were reduced PI, reduced PF, and reduced use of rescue medications in the nVNS group. It appears that the duration of nVNS (30, 60, 120 s), respectively, correlated with the increased significance of results.

Reported adverse events related to the intervention were ulcers at the auricular cite [31]. No device or intervention related adverse events were reported by Chaudhry et al. [21] or Grazzi et al. [29].

3.6 CH

Silberstein et al. [30] and Goadsby et al. [28] had similar studies with comparable outcomes. Silberstein included both male and females, 18–65 years of age. Goadsby included both males and females, ages 33–55 years of age. Both studies looked at nVNS for treatment of episodic cluster headaches (eCH) vs chronic cluster headaches (cCH). Both RCTs found significant effects for eCH, but not cCH, in reduced PI, with a frequency of 25 Hz to the cervical branch of the vagus nerve.

Gaul et al. [27] also looked at nVNS in CH in both male and female subjects, 18–70 years of age. Gaul found reduced PI, PF, improved PR, reduced depression, and reduced medication use with a treatment frequency at 5 Hz to the cervical branch of the vagus nerve. No adverse events related to the device or intervention were reported.

The differences in outcomes in the study by Gaul et al. [27] compared to that by Silberstein et al. [30] and Goadsby et al. [28] may be related to the selection of treatment frequency. The frequency of nVNS appears to have different effects at the cervical and auricular branches of the vagus nerve in headache disorders. One possible explanation may be due to the myelination of the cervical branch and no myelination of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. [31]. Further investigation should be done to understand these differences.

Reported adverse events related to nVNS were facial twitching, tingling or pulling, and skin irritation, redness, or soreness at the application site [30]. Goadsby et al. [28] reported no severe adverse events related to the device or intervention, however it is unclear as to what non-severe adverse events occurred.

3.7 Chronic pain

Winstead [33] investigated the effects of HRVB compared to a sham group in veterans with chronic pain. The study included males (66%) and females (33%) within 43–65 years of age. HRVB performed six times per week for 25 min over the course of 8 weeks followed by a 12-week booster session and 16-week follow up. Significant positive outcomes were reported for reduced PI and disability for the HRVB group compared to the sham group. No adverse events were reported.

3.8 Fibromyalgia

Kutlu et al. [32] investigated the use of nVNS in females with fibromyalgia. nVNS with a frequency of 10 Hz, to the auricular branch of the vagus nerve, combined with exercise, was compared to exercise alone (control group). There were significant benefits in both the intervention group and the control group for reducing PI and reducing disability scores; however, there were no significant differences between the groups. Limitations of this study were generalizability as only females were included, and literature shows males and females have different pain and HRV responses [17]. The exercises in both groups were generally stated; therefore, it is unclear as to which specific exercises may be beneficial. No adverse events were reported.

Pacccione et al. [36] studied both males and females with fibromyalgia separated into four treatment groups: receiving active nVNS (25 Hz), sham nVNS, meditation centered diaphragmatic breathing, and sham breathing technique. No significant differences were identified between groups. There are two primary limitations of this study. First, the participants were primarily female (94.8%) and based on the individual and sex differences in HRV responses, the results may have been affected. Second, the sample size for each group may not have been adequate to identify significant differences between groups. One adverse event occurred with active nVNS resulting in chest discomfort and pain with the intervention, resulting in the participant withdrawal from the study.

3.9 Chronic low back pain

Uzlifatin et al. [37] compared two groups: one group received nVNS (25 Hz) and exercise while the control group received only exercise. Both groups reported significant improvements in perceived disability; however, no differences were identified between groups. Limitations included a small sample size and retesting occurring only 1 day after the treatment which may not have allowed adequate time to measure for changes which might have occurred over time if long-term follow up assessment was completed. No adverse events were reported.

4 Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to compare nVNS and HRVB interventions on PI, PF, and PR, in chronic pain conditions. This systematic review of the literature was conducted and found moderate quality evidence to support both interventions in the treatment of chronic pain conditions.

PI was significantly reduced in all studies with the exception of the groups for cCH [21,31]. These findings were similar to Busch et al. [35] which found reduced musculoskeletal pain and reduced experimentally induced pain perception with use of nVNS on healthy volunteers.

Pain episode frequency was significantly reduced in three studies [21,27,29], not significantly reduced in one study [31], and was not reported in four studies [28,30,32,33]. These results may indicate that more research needs to be done to understand the effects of nVNS and HRVB on the frequency of pain in chronic pain conditions.

PR was significant for two studies [27,28], not significant in three studies [30,36,37], and not reported in five studies [21,29,31–33]. A review of the literature revealed no significant findings in the literature supporting the use of these interventions for PR. More research may need to be done to support the findings of Goadsby et al. [28] and Gaul et al. [27] on PR.

Rescue medication use was significantly reduced in two studies [27,29], not significant in two studies [30,33], and not reported in six studies [21,28,31,32,36,37]. More research needs to be done to validate these results.

4.1 Limitations of this review

Limitations for this systematic review include study type, where only full-text RCTs in English were included, including one doctoral dissertation [33]. Third-party participants, such as an academic librarian, for settling discrepancies in article selection were not involved in this review. The sample size was low among the included studies. While the largest sample size was N = 285 participants, [29] the mean sample size among the remaining 9 studies was N = 62.8, and the overall mean sample size was N = 173.9. A lack of heterogeneity among pain conditions is also noted across the studies, with all but four studies evaluating subjects with migraine and CH conditions. The remaining two studies [32,33,36,37] evaluated subjects with chronic pain and fibromyalgia, respectively. Other potential limitations include the varied use of placebo/sham and blinding, limited study duration, and follow-up duration. Due to variability in observed conditions, outcome measures, and limited reported statistical data, meta-analysis was not performed.

5 Conclusion

This is the first review that compares the effectiveness of nVNS to HRVB as a pain reduction technique, in people with chronic pain. The result of this review showed that HRVB and nVNS may be effective in reducing PI, depression scores, pain episodes/frequency, and medication use, in chronic pain conditions. There is not, however, enough literature to support one intervention approach over the other.

The systematic review of RCTs of patients with chronic non-cancer pain included evidence from moderate to high-quality studies suggesting nVNS is beneficial in reducing headache frequency, which may be used as an alternative to abortive medication, and is well-tolerated. HRVB interventions are beneficial in reducing pain, reduced depression scores, reduced use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication, and increased HRV coherence ratio. HRVB and nVNS have shown clinical benefits in the treatment of chronic pain conditions; however, insufficient literature exists to support one approach. This systematic review establishes the need to evaluate the treatment effects of HRVB in chronic pain conditions and HRV as an objective pain measure via autonomic responses. Further research is needed to establish protocols for nVNS by location, as it appears that the cervical and auricular branches respond to different frequencies for PR.

5.1 Implications for practice

In summary, impaired vagal tone is related to pain in individuals who experience chronic pain conditions. Individuals with chronic pain conditions including fibromyalgia, migraine, and CH, who received nVNS or HRVB, reported an improvement in PI, PF, medication use frequency, and depression. More “high-quality” research is needed that looks at nVNS and HRVB in chronic pain conditions. Negative outcomes included adverse events reported at the site of application of nVNS resulting in skin irritation, redness, soreness, or muscle twitching, pulling or dropping, and ulceration. No severe adverse effects were related to the use of nVNS.

5.2 Implications for research

Currently, more research is needed to investigate the specific mechanisms behind impaired vagal activity in chronic pain patients [13]. Additionally, research that explores the underlying mechanisms of HRV biofeedback on pain and determining the optimal treatment parameters for nVNS are required.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Abebaw Mengistu Yohannes, PhD, MSc, FCCP, Professor of Physical Therapy, Azusa Pacific University, for his guidance and support for writing this manuscript.

-

Research ethics: Ethical approval was not needed as this study is a systematic review.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was not needed as this study did not involve direct human participation.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

-

Artificial intelligence/Machine learning tools: Not applicable.

Search strategy and search terms

| Database/resource | Strategy/search terms |

|---|---|

| Pubmed | PIO: |

| Search limits: | Chronic pain [MeSH Terms] OR (chronic pain) OR Fibromyalgia [MeSH Terms] OR (fibromyalgia) OR Migraine [MeSH Terms] OR (migraine) OR Headache [Mesh Terms] OR (headache) AND Vagus nerve stimulation [MeSH Terms] OR (vagus nerve stimulation) AND (transcutaneous) pain assessment [MeSH Terms] |

| Full text | |

| Randomized control trial (RCT) | |

| From 2010 to 2023 | |

| PCO: | |

| Chronic pain [MeSH Terms] OR (chronic pain) OR Fibromyalgia [MeSH Terms] OR (fibromyalgia) OR Migraine [MeSH Terms] OR (migraine) OR Headache [Mesh Terms] OR (headache) AND (biofeedback) AND (heart rate variability) AND pain assessment [MeSH Terms] | |

| PI: | |

| Chronic pain [MeSH Terms] OR (chronic pain) OR Fibromyalgia [MeSH Terms] OR (fibromyalgia) OR Migraine [MeSH Terms] OR (migraine) OR Headache [Mesh Terms] OR (headache) AND Vagus nerve stimulation [MeSH Terms] OR (vagus nerve stimulation) | |

| PC: | |

| Chronic pain [MeSH Terms] OR (chronic pain) OR Fibromyalgia [MeSH Terms] OR (fibromyalgia) OR Migraine [MeSH Terms] OR (migraine) OR Headache [Mesh Terms] OR (headache) AND (biofeedback) AND (heart rate variability) | |

| CO: | |

| (Biofeedback) AND (heart rate variability) AND (pain) | |

| IO: | |

| (vagus nerve stimulation [MeSH Terms]) OR (vagus nerve stimulation) AND (transcutaneous) AND (pain) | |

| Cochrane | MeSH descriptor: [Biofeedback, Psychology] explode all trees AND (“heart rate variability”) OR MeSH descriptor: [Vagus Nerve Stimulation] explode all trees AND MeSH descriptor: [Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation] explode all trees AND MeSH descriptor: [Chronic Pain] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Headache Disorders] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Migraine Disorders] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Migraine Disorders] explode all trees |

| Search Limits: | |

| Full text | |

| RCT | |

| From 2010 to 2023 | |

| MEDLINE | PICO: |

| Search limits: | TX (“chronic pain” OR “fibromyalgia” OR “headache disorder” OR “migraine disorder”) AND TX (“heart rate variability” AND “biofeedback”) OR TX (“vagus nerve stimulation” and transcutaneous) AND (pain assessment) |

| From 2010 to 2023 | |

| English | |

| Human | |

| RCT | PIC: |

| Scholarly (Peer reviewed) | |

| Journals | TX (“chronic pain” OR “fibromyalgia” OR “headache disorder” OR “migraine disorder”) AND TX (“heart rate variability” AND “biofeedback”) OR TX (“vagus nerve stimulation” and transcutaneous) |

| EBSCO (CINAHL and SPORTDiscus) | PIC: |

| Search limits: | TX (“chronic pain” OR “fibromyalgia” OR “headache disorder” OR “migraine disorder”) AND TX (“heart rate variability” AND “biofeedback”) OR TX (“vagus nerve stimulation” AND transcutaneous) |

| Full text | |

| RCT | |

| From 2010 to 2023 | |

| Peer reviewed | |

| English | |

| Research article | |

| Human | |

| Age groups | |

| Publication type | |

| EMBASE | PICO: |

| Search limits: | TX (“chronic pain” OR “fibromyalgia” OR “headache disorder” OR “migraine disorder”) AND TX (“heart rate variability” AND “biofeedback”) OR TX (“vagus nerve stimulation” AND transcutaneous) |

| From 2010 to 2023 | |

| English | |

| Human | |

| RCT | |

| Scholarly (Peer reviewed) | |

| Journals | |

| Google Scholar | “chronic pain” AND “heart rate variability biofeedback” OR “vagus nerve stimulation” AND trial* |

| Performed on May 30, 2020 | |

| Search limits: | |

| Years 2010–2023 | “fibromyalgia” AND “heart rate variability biofeedback” OR “vagus nerve stimulation” |

| “headache” AND “heart rate variability biofeedback” OR “vagus nerve stimulation” | |

| “migraine” AND “heart rate variability biofeedback” OR “vagus nerve stimulation” |

PRISMA checklist

| Section and topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review | Pg. 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist | Pg. 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge | Pg. 3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses | Pg. 4 |

| Methods | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses | Pg. 5 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted | Pg. 4 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers, and websites, including any filters and limits used | Appendix A |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | Pg. 6 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | Pg. 6 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect | Pg. 6 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information | n/a | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study, and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | Pg. 8 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results | n/a |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)) | Pg.8 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions | n/a | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses | Pg. 9, Figure 2 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used | Pg. 10 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression) | n/a | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results | n/a | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases) | Pg. 9 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome | n/a |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram | Pg. 9 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded | Pg. 9 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics | Pg. 10 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study | Pg. 10 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots | n/a |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarize the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies | Pg. 10 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect | Pg. 9 Table 1, Appendix C | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results | Pg. 10 and 16 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results | n/a | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed | n/a |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed | Pg. 12 |

| Discussion | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence | Pg. 15 and 16 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review | Pg 16 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used | Pg 16 and 17 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research | Pg. 18 | |

| Other Information | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered | n/a |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared | n/a | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol | n/a | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review | Pg. 18 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors | Pg. 18 |

| Availability of data, code, and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review | n/a |

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Characteristics of studies

| Study (Authors) | Chaudhry S.R., Lendvai I.S., Muhammad S., Westhofen P., Kruppenbacher J., Scheef L., et al. |

| Design | RCT |

| Setting for population | Outpatient, University of Bonn, Germany |

| Inclusion criteria | Chronic refractory headache disorder according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria (3rd edition, beta version) age equal/greater than 18; informed consent (Study, nVNS); refractory to medical and/or behavioral therapy; eligible for vagus nerve stimulation; willingness to a defined follow-up interval; stable pain medication 4 weeks prior to nVNS |

| Exclusion criteria | No informed consent; other concomitant neuropsychiatric comorbidity not adequately classified and/or requiring specific diagnosis/treatment; pregnancy; Previously performed invasive, noninvasive, and ablative procedures; not willing to complete pain diary regarding severity and frequency; intracranial and cervical pathologies confirmed by magnetic resonance scan; medication overuse headache |

| Total Number Randomized | 30 |

| interventions | |

| Group A | |

| Total no. of participants | 15 |

| Setting of intervention | Outpatient |

| Description of intervention | I: Self-administered, 1 ms bursts of 5 kHz sine waves, repeated every 40 ms (25 Hz) with an adjustable stimulation intensity (from 0 to 24 V). C: nVNS sham stimulation was achieved by producing a 0.1 kHz biphasic signal |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | BID (AM and late afternoon), 120 s stimulations (1 stimulation R & L), daily prophylaxis = BID 120 s bilateral, for treatment of sx = 120 s, second dose after 15–30 min if first dose unsuccessful, instructed to treat up to 5 migraine attacks with nVNS or sham during the double blind period and up to 5 additional attacks with nVNS during the open-label period. Only one attack during a 48-h period |

| Exclusion | 1 (device malfunction) |

| Group B | |

| Total no. of participants | n = 15 |

| Description of intervention | Sham = I: Self-administered, Hz stimulation: nVNS sham stimulation was achieved by producing a 0.1 kHz biphasic signal |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | BID (AM and late afternoon), 120 s stimulations (1 stimulation R & L), daily prophylaxis = BID 120 s bilateral, for treatment of sx = 120 s, second dose after 15–30 min if first dose unsuccessful, instructed to treat up to five migraine attacks with nVNS or sham during the double blind period and up to five additional attacks with nVNS during the open-label period. Only one attack during a 48 h period |

| Exclusion | 3 (1 device malfunction, 1 cold, 1 worsening of head pain requiring change in medication) |

| Outcomes | |

| PI (visual analogue scale) | |

| PF | |

| Study (Authors) | Gaul C, Magis D, Liebler E, Straube A. (2017) |

| Design | RCT |

| Setting for population | 10 European sites: 5 Germany, 3 in UK, 1 Belgium, 1 Italy |

| Inclusion criteria | Chronic CH according to ICHD >1 year before enrollment |

| Exclusion Criteria | Change in prophylactic medication type or dosage <1 month before enrolment; history of intracranial/carotid aneurysm or hemorrhage; brain tumors/lesions; significant head trauma; previous surgery or abnormal anatomy at the nVNS treatment site; known or suspected cardiac/cardiovascular disease; implantation with electrical or neurostimulation devices; history of carotid endarterectomy or vascular neck surgery; implantation with metallic hardware; and recent history of syncope or seizures |

| Total number | N = 97 |

| of interventions | |

| Group A | |

| Total no. of participants | 48; 4 d/c’d (11 additional during extension phase) |

| Setting of intervention | 10 European sites: 5 Germany, 3 in UK, 1 Belgium, 1 Italy |

| Description of intervention | Self-administered prophylaxis: (1) within 1 h of waking and (2) 7–10 h after first treatment |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | Acute treatment: 3, 2-min stimulations 5 min apart, R. vagal nerve 25 Hz |

| Group B | |

| Total no. of participants | 49; 1 d/c’d (additional 11 during extension phase) |

| Setting of intervention | 10 European sites: 5 Germany, 3 in UK, 1 Belgium, 1 Italy |

| Description of intervention | Standard of care |

| Outcomes | |

| PI (Likert Scale) | |

| PF | |

| Medication use | |

| Study (Authors) | Goadsby P.J., de Coo I.F., Silver N., Tyagi A., Ahmed F., Gaul C., et al. (2018) |

| Design | RCT |

| Setting for population | Four European countries at nine tertiary care sites |

| Inclusion criteria | >18 y/o, diagnosis of eCH/cCH |

| Exclusion criteria | New treatment for CH, pregnant, nursing, thinking of becoming pregnant, abnormal baseline ECG |

| Total no. randomized | N = 102 |

| interventions | |

| Group A | |

| Total no. of participants | 50 |

| Setting of intervention | Home |

| Description of intervention | nVNS |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | 5 kHz 9–15 min |

| Group B | |

| Total no. participants | 52 |

| Setting of intervention | Home |

| Description of intervention | Sham |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | Low tingling sensation that did not stimulate the vagus nerve 9–15 min |

| Outcomes | |

| All treated attacks that achieved pain free status within 15 min did not differ. Significant effect of treatment group and CH subtype. eCH had a higher proportion of treated attacks with nVNS than sham. No difference was found in cCH. | |

| Study (Authors) | Grazzi L., Tassorelli C., de Tommaso M., Pierangeli G., Martelletti P., Rainero I., et al. (2018) |

| Design | RCT: three 4-week periods: (1) run-in, (2) double-blind, and (3) open-label periods |

| Setting for population | 10 sites in France |

| Inclusion criteria | <50 years of age at migraine onset; frequency of 3–8 attacks per month |

| Exclusion criteria | History of secondary headache, another significant pain disorder, uncontrolled hypertension, BOTOX injections in the last 6 months, head or neck nerve blocks in the last 2 months |

| Total number Randomized | N = 285 |

| interventions | |

| Group A | |

| Total no. of participants | n = 122 |

| Setting of intervention | 10 Sites in France |

| Description of intervention | Within 20 min of migraine pain onset, patients self-administered two bilateral 120 s stimulations (1 stimulation each to the right and left cervical branch of the vagus nerve). If no pain decrease 15 min post nVNS, stimulation was repeated |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | |

| Group B | |

| Total no. of participants | n = 126 |

| Setting of intervention | 10 Sites in France |

| Description of intervention | 0.1 |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | |

| Outcomes | |

| Rescue Medication | |

| PI (Likert Scale) | |

| PR | |

| Study (Authors) | Kutlu, Ozden, Alptekin, and Alptekin |

| Design | RCT, randomized, no blinding |

| Setting for population | Beykoz Public Hospitals dept. of PT and rehab |

| Inclusion criteria | Fibromyalgia diagnosis by physiatrist according to 2010 ACR criteria |

| Exclusion criteria | Pregnant, menopausal, post-menopausal, or comorbid illness |

| Total number Randomized | 60 |

| interventions | |

| Group A | |

| Total no. of participants (initial/less lost to follow-up [LTF]) | 30/27 |

| Description of intervention | tx: exercise and vagus stimulation group aVNS at hospital 5 days/week for 4 weeks. 20 sessions × 30 min. TENS device was used for vagus nerve stimulation. Same home-based exercise program performed 2 sets/day 10/set for each exercise. 4 face to face sessions |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | |

| study (Authors) | |

| Group B | |

| Total no. of participants (initial/less LTF) | 30/25 |

| Setting of intervention | Exercise program consisting of strengthening, stretching, isometric, and posture exercises targeting the body and UE and LE’s. Home-based weekly face to face sessions with a total of four throughout the study |

| Description of intervention | |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | |

| Study (Authors) | |

| Outcomes |

| Study (Authors) | Silberstein SD, Calhoun AH, Lipton RB, Grosberg BM, Cady RK, Dorlas S, et al. (2016) |

| Design | RCT |

| Setting for population | 20 U.S. centers including university-based/academic medical centers and headache/pain/neurological clinics and institutes |

| Inclusion criteria | Episodic or CH. No further clarity |

| Exclusion criteria | History of aneurysm, intracranial hemorrhage, brain tumors, significant head trauma, prolonged QT interval, arrhythmia, ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, syncope, or seizure; structural intracranial/cervical vascular lesions; another significant pain disorder; cardiovascular disease; uncontrolled hypertension; abnormal baseline electro-cardiogram; botulinum toxin injections in the past 3 months; nerve blocks in the past 1 month; previous CH surgery, bilateral/right cervical vagotomy, carotid endarterectomy, or right vascular neck surgery; electrical device implantation; and current use of prophylactic medications for indications other than CH. |

| Total number Randomized | N = 150 |

| interventions | |

| Group A | |

| Total no. of participants | n = 73 |

| Setting of intervention | 20 U.S. centers including university-based/academic medical centers and headache/pain/neurological clinics and institutes |

| Description of Intervention | A 5 kHz sine wave burst lasting for 1 ms (five sine waves, each lasting 200 µs), with such bursts repeated once every 40 ms (25 Hz), generating a 24 V peak voltage and 60 mA peak output current. Right cervical branch |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | |

| Group B | |

| Total no. of participants | n = 77 |

| Setting of intervention | 20 U.S. centers including university-based/academic medical centers and headache/pain/neurological clinics and institutes |

| Description of intervention | Sham device produces a low-frequency (0.1 Hz) biphasic signal that does not stimulate the vagus nerve or generally cause muscle contraction. Right Cervical Branch |

| Study (Authors) | Straube A, Ellrich J, Eren O, Blum B, Ruscheweyh R. (2015) |

| Design | RCT |

| Setting for population | Outpatient facility in Munich, Germany |

| Inclusion criteria | Chronic migraine defined by ICHD-IIR, duration of > or = 6 months, no migraine prophylactic meds for > or = 1 month, stable acute med eligible. |

| Exclusion criteria | Primary or secondary headaches, severe neurologic or psychiatric disorders including opioid- or tranquilizer-dependency, cranio-mandibulary dysfunction, fibromyalgia, had a Beck’s Depression Inventory ([24]) score >25 at the screening visit, anatomic or pathologic changes at the left outer ear, currently participated in another clinical trial, or were unable to keep a headache diary. Pregnant or breast-feeding women were also excluded |

| Total number Randomized | N = 39 |

| interventions | |

| Group A | |

| Total no. of participants | n = 22 (1 Hz) |

| Setting of intervention | Outpatient facility in Munich, Germany |

| Description of intervention | nVNS at the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | Pt self-stimulated 4 h/day with a frequency of 1 Hz |

| Group B | |

| Total no. of participants | n = 17 (25 Hz) |

| Setting of intervention | Outpatient facility in Munich, Germany |

| Description of intervention | nVNS at the auricular branch of the vagus nerve |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | Pt self-stimulated 4 h/day with a frequency of 25 Hz |

| Outcomes | |

| Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) | |

| HIT | |

| MIDAS | |

| Medication use | |

| Headache # days and duration | |

| Study (Authors) | J.P. Winstead (2019) | |

| Design | RCT: Single-blind | |

| Inclusion criteria | >18, veteran, chronic pain, male or female, any race, any ethnicity | |

| Exclusion criteria | <18, Rx medications or medical conditions that may bias HRV and preclude protocol compliance, (a) arrhythmias requiring medication and/or hospitalization, including supraventricular tachycardia or atrial fibrillation; (b) veterans with a pacemaker or automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; (c) history of an acute coronary syndrome, revascularization, thrombolytic, or other therapy related to ischemic heart disease; (d) uncontrolled hypertension history of heart transplant or cardiovascular surgery within one year; (f) receiving beta-adrenergic antagonists (beta-blockers); (g) receiving non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; (h) congestive heart failure, (j) seizures, (k) dementia, (i) head injury or CVA, (m) substance abuse, (n) bipolar, psychotic, panic, or obsessive-compulsive disorder | |

| Total number Randomized | 85, N = 50 completed study | |

| interventions | ||

| Group A | ||

| Total no. of participants | 25 | |

| Setting of intervention | WJB Dorn Veterans Administration Medical Center (DVAMC) | |

| Description of intervention | HRVB training was conducted by a certified trainer following a previously established, standardized protocol adopted by the Biofeedback Certification Institute of America (BCIA). | |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | Participants in intervention group received 6 weekly training sessions (25-min resting period that included coaching and biofeedback training) | |

| Group B | ||

| Total no. of participants | 25 | |

| Setting of intervention | WJB Dorn Veterans Administration Medical Center (DVAMC) | |

| Description of intervention | HRVB | |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | Participants in Sham group received six weekly training sessions (25-min resting period that included coaching and biofeedback training.) | |

| Outcomes | ||

| Pain severity (Brief Pain inventory) | ||

| Pain catastrophizing scale | ||

| Pain medication use | ||

| Paced auditory serial addition test (PASAT) | ||

| Hopkins verbal learning test-revised (HVLT-R), Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) | ||

| Beck Disability Index BDI | ||

| Perceived stress scale | ||

| Multidimensional fatigue inventory | ||

| HRV coherence ratio | ||

| Pain interference score | ||

| Study (Authors) | Paccione CE, Stubhaug A, Diep LM, Rosseland LA, and Jacobsen HB |

| Design | RCT |

| Setting for population | Department of Pain Management and Research, Division of Emergencies and Critical Care, Oslo University Hospital |

| Inclusion criteria | Criteria derived from a prior study by Paccione et al., 2020

|

| Exclusion criteria | Criteria derived from a prior study by Paccione et al. 2020 |

| Participants must not have any past history and/or presence of comorbid severe neurological or psychiatric disorders and/or neurodegenerative disorders. Participants excluded on pregnancy/planned pregnancy, planned surgery; receiving treatment for any type of eating disorder, head trauma; migraine; active heart implants (e.g., pacemaker); and active ear implants (e.g., cochlear implant). Individuals who have practiced meditation consistently (for more than 20 min/day) within the last 6 months were also be excluded | |

| Total number Randomized | 116 enrolled, 86 completed |

| interventions: | |

| Total participants per group | Active tVNS n = 28, Sham tVNS n = 29, Active MDB n = 29, Sham MDB n = 30 |

| Setting of intervention | Outpatient |

| Description of groups | tVNS #1 (active); tVNS #2 (sham); MDB #1 (active); MDB #2 (sham) |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | Treatment protocols were derived from a prior study by Paccione et al. 2020 |

| tVNS #1 self-administered Bipolar stimulation within conchae of left ear or center of left earlobe. “Nemos ®” device. Intensity 0.1–10 mA with a pulse width of 250 μs and a consistent stimulation frequency of 25 Hz for optimal stimulation active 30 s, break 30 s total 15 min BID | |

| MDB#1 Guided meditation and diaphragmatic breathing 15 min BID w/BarTek device around abdomen and rib cage, use of MNRB™ program on the Krüger&Matz Flow 5 Android phone. respiration rate of 12 breaths/min to a resonance frequency rate of 6 breaths/min | |

| Outcomes | |

| PI (NRS) Current | |

| PI (NRS) Average | |

| WPI | |

| SSS | |

| Study (Authors) | Uzlifatin, Y; Arfianti, L; Wardhani, IL; Hidayati, HB; Melaniani, S |

| Design | RCT |

| Setting for population | Polyclinic, Surabaya, Indonesia |

| Inclusion criteria | Chronic, non-organic, mechanical low back pain of 3–12 months duration, NPRS 4–7, able to understand directions |

| Exclusion criteria | Presence of red flags, analgesics except paracetamol or NSAIDs, new analgesic in the prior 2 weeks; the use of other modalities in the last 1 week, history trauma or skin disorders, history of face pain, the use of metal implants including pacemakers, pregnancy, history of heart disease (e.g., dysrhythmia, arrhythmia, coronary heart disease), history of neurological disorders (including seizures or epilepsy), history of moderate-severe depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) ≥ 17), history of vasovagal syncope, history of metal allergy to skin, alcohol and drug dependence, and obesity grade II (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

| Total number Randomized | 22 |

| interventions | |

| Group A | |

| Total no. of participants | 11 |

| Setting of intervention | Polyclinic |

| Description of intervention | I: nVNS: 25 Hz, the pulse width was 250 μs, the intensity as the patient’s tolerance, at the cymba conchae and conchae of the left ear |

| Physiotherapist-led exercise: Physiotherapist-led exercise: Breathing exercise with diaphragmatic breathing, posture correction (kinesthetic awareness), abdominal drawing in (muscle performance), cat and camel (muscle performance), pelvic tilt (mobility/flexibility), single knee to chest (mobility/flexibility), double knee to chest (mobility/flexibility) | |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | nVNS: 20 min, 5×/week, for 2 weeks; exercise: 2×/day × 2 weeks |

| Exclusion | 0 |

| Group B | |

| Total no. of participants | n = 11 |

| Description of intervention | Physiotherapist-led exercise: Breathing exercise with diaphragmatic breathing, posture correction (kinesthetic awareness), abdominal drawing in (muscle performance), cat and camel (muscle performance), pelvic tilt (mobility/flexibility), single knee to chest (mobility/flexibility), double knee to chest (mobility/flexibility) |

| Duration + frequency of intervention | 2×/day × 2 weeks |

| Exclusion | 0 |

| Outcomes | |

| PI (NPRS) | |

| Disability (RMDQ) | |

| Depression: HDRS | |

References

[1] Dorner TE, Alexanderson K, Svedberg P, Tinghog P, Ropponen A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E. Synergistic effect between back pain and common mental disorders and the risk of future disability pension: a nationwide study from Sweden. Psychol Med. Jan 2016;46(2):425–36. 10.1017/S003329171500197X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Groenewald CB, Palermo TM. The price of pain: the economics of chronic adolescent pain. Pain Manag. 2015;5(2):61–4. 10.2217/pmt.14.52.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JW, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Benoliel R, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain. Jan 2019;160(1):28–37. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001390.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Phillips CJ. Economic burden of chronic pain. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. Oct 2006;6(5):591–601. 10.1586/14737167.6.5.591.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Mayer S, Spickschen J, Stein KV, Crevenna R, Dorner TE, Simon J. The societal costs of chronic pain and its determinants: The case of Austria. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213889. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213889.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. Feb 2022;163(2):e328–32. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. Aug 2012;13(8):715–24. 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Stubhaug A, Hansen JL, Hallberg S, Gustavsson A, Eggen AE, Nielsen CS. The costs of chronic pain-long-term estimates. Eur J Pain. 2024;28(6):960–77. 10.1002/ejp.2234.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Thanh NX, Tanguay RL, Manhas KJP, Kania-Richmond A, Kashuba S, Geyer T, et al. Economic burden of chronic pain in Alberta, Canada. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0272638. 10.1371/journal.pone.0272638.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Tracy LM, Ioannou L, Baker KS, Gibson SJ, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Giummarra MJ. Meta-analytic evidence for decreased heart rate variability in chronic pain implicating parasympathetic nervous system dysregulation. Pain. Jan 2016;157(1):7–29. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000360.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Benjamin JG, Moran RW, Plews DJ, Kilding AE, Barnett LE, Verhoeff WJ, et al. The effect of osteopathic manual therapy with breathing retraining on cardiac autonomic measures and breathing symptoms scores: A randomised wait-list controlled trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther. Jul 2020;24(3):282–92. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.02.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Forte G, Troisi G, Pazzaglia M, Pascalis V, Casagrande M. Heart rate variability and pain: A systematic review. Brain Sci. Jan 2022;12(2):153. 10.3390/brainsci12020153.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Koenig J, Falvay D, Clamor A, Wagner J, Jarczok MN, Ellis RJ, et al. Pneumogastric (Vagus) nerve activity indexed by heart rate variability in chronic pain patients compared to healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician. Jan 2016;19(1):E55–78.10.36076/ppj/2016.19.E55Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Li T, Higgins J, Deeks J. Chapter 5: Collecting data. In: Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochran handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Ayorinde AA, Williams I, Mannion R, Song F, Skrybant M, Lilford RJ, et al. Assessment of publication bias and outcome reporting bias in systematic reviews of health services and delivery research: A meta-epidemiological study. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227580. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227580.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Apkarian AV, Baliki MN, Geha PY. Towards a theory of chronic pain. Prog Neurobiol. Feb 2009;87(2):81–97. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.018.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Umetani K, Singer DH, McCraty R, Atkinson M. Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: relations to age and gender over nine decades. J Am Coll Cardiol. Mar 1998;31(3):593–601. 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00554-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Lehrer PM, Gevirtz R. Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Front Psychol. 2014;5:756. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Gevirtz R. The promise of hear rate variability biofeedback: Evidence-based application. Biofeedback. 2013;41(3):110–20. 10.5298/1081-5937-41.3.01.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Badran BW, Dowdle LT, Mithoefer OJ, LaBate NT, Coatsworth J, Brown JC, et al. Neurophysiologic effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) via electrical stimulation of the tragus: A concurrent taVNS/fMRI study and review. Brain Stimul. May-Jun 2018;11(3):492–500. 10.1016/j.brs.2017.12.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Chaudhry SR, Lendvai IS, Muhammad S, Westhofen P, Kruppenbacher J, Scheef L, et al. Inter-ictal assay of peripheral circulating inflammatory mediators in migraine patients under adjunctive cervical non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS): A proof-of-concept study. Brain Stimul. May-Jun 2019;12(3):643–51. 10.1016/j.brs.2019.01.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Gaul C, Diener HC, Silver N, Magis D, Reuter U, Andersson A, et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for PREVention and Acute treatment of chronic cluster headache (PREVA): A randomised controlled study. Cephalalgia. May 2016;36(6):534–46. 10.1177/0333102415607070.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. Jan 2005;113(1–2):9–19. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Nov 2006;31(23):2724–7. 10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Sterne JA, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. Aug 2019;366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd edn. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2019.10.1002/9781119536604Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Gaul C, Magis D, Liebler E, Straube A. Effects of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation on attack frequency over time and expanded response rates in patients with chronic cluster headache: a post hoc analysis of the randomised, controlled PREVA study. J Headache Pain. Dec 2017;18(1):22. 10.1186/s10194-017-0731-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Goadsby PJ, de Coo IF, Silver N, Tyagi A, Ahmed F, Gaul C, et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for the acute treatment of episodic and chronic cluster headache: A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled ACT2 study. Cephalalgia. Apr 2018;38(5):959–69. 10.1177/0333102417744362.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Grazzi L, Tassorelli C, de Tommaso M, Pierangeli G, Martelletti P, Rainero I, et al. Practical and clinical utility of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for the acute treatment of migraine: a post hoc analysis of the randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind PRESTO trial. J Headache Pain. Oct 2018;19(1):98. 10.1186/s10194-018-0928-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Silberstein SD, Calhoun AH, Lipton RB, Grosberg BM, Cady RK, Dorlas S, et al. Chronic migraine headache prevention with noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation: The EVENT study. Neurology. Aug 2016;87(5):529–38. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002918.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Straube A, Ellrich J, Eren O, Blum B, Ruscheweyh R. Treatment of chronic migraine with transcutaneous stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagal nerve (auricular t-VNS): a randomized, monocentric clinical trial. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:543. 10.1186/s10194-015-0543-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Kutlu N, Ozden AV, Alptekin HK, Alptekin JO. The impact of auricular vagus nerve stimulation on pain and life quality in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:8656218. 10.1155/2020/8656218.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Winstead JP. Role of heart rate variability biofeedback in cognitive performance, chronic pain, and related symptoms. Doctoral dissertation; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Schünemann H, Brozek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A. GRADE handbook for grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Busch V, Zeman F, Heckel A, Menne F, Ellrich J, Eichhammer P. The effect of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on pain perception–an experimental study. Brain Stimul. Mar 2013;6(2):202–9. 10.1016/j.brs.2012.04.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Paccione CE, Stubhaug A, Diep LM, Rosseland LA, Jacobsen HB. Meditative-based diaphragmatic breathing vs vagus nerve stimulation in the treatment of fibromyalgia - A randomized controlled trial: Body vs machine. Front Neurol. 2022;13:1030927. 10.3389/fneur.2022.1030927.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Uzlifatin Y, Arfianti L, Wardhani IL, Hidayati HB, Melaniani S. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in addition to exercises on disabilitiy in chronic low back pain patients: A randomized controlled study. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2023;21(1):73–81. 10.35975/apic.v27i1.2084.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- Abstracts presented at SASP 2025, Reykjavik, Iceland. From the Test Tube to the Clinic – Applying the Science

- Quantitative sensory testing – Quo Vadis?

- Stellate ganglion block for mental disorders – too good to be true?

- When pain meets hope: Case report of a suspended assisted suicide trajectory in phantom limb pain and its broader biopsychosocial implications

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation – an important tool in person-centered multimodal analgesia

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Exploring the complexities of chronic pain: The ICEPAIN study on prevalence, lifestyle factors, and quality of life in a general population

- The effect of peer group management intervention on chronic pain intensity, number of areas of pain, and pain self-efficacy

- Effects of symbolic function on pain experience and vocational outcome in patients with chronic neck pain referred to the evaluation of surgical intervention: 6-year follow-up

- Experiences of cross-sectoral collaboration between social security service and healthcare service for patients with chronic pain – a qualitative study

- Completion of the PainData questionnaire – A qualitative study of patients’ experiences

- Pain trajectories and exercise-induced pain during 16 weeks of high-load or low-load shoulder exercise in patients with hypermobile shoulders: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- Pain intensity in anatomical regions in relation to psychological factors in hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Opioid use at admittance increases need for intrahospital specialized pain service: Evidence from a registry-based study in four Norwegian university hospitals

- Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces temperature-evoked pain in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study

- Pain and health-related quality of life among women of childbearing age in Iceland: ICEPAIN, a nationwide survey

- A feasibility study of a co-developed, multidisciplinary, tailored intervention for chronic pain management in municipal healthcare services