Abstract

Objectives

Chronic pain causes loss of workability, and pharmacological treatment is often not sufficient, whereas psychosocial treatments may relieve continual pain. This study aimed to investigate the effect of peer group management intervention among patients with chronic pain.

Methods

The participants were 18–65-year-old employees of the Municipality of Helsinki (women 83%) who visited an occupational health care physician, nurse, psychologist, or physiotherapist for chronic pain lasting at least 3 months. An additional inclusion criterion was an elevated risk of work disability. Our study was a stepped wedge cluster, randomized controlled trial, and group interventions used mindfulness, relaxation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy. We randomized sixty participants to either a pain management group intervention or to a waiting list with the same intervention 5 months later. After dropouts, 48 employees participated in 6 weekly group meetings. We followed up participants from groups A, B, and C for 12 months and groups D, E, and F for 6 months. As outcome measures, we used the pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, the number of areas of pain, the visual analog scale of pain, and the pain self-efficacy. We adjusted the results before and after the intervention for panel data, clustering effect, and time interval.

Results

The peer group intervention decreased the number of areas of pain by 40%, from 5.96 (1–10) to 3.58 (p < 0.001), and increased the pain self-efficacy by 15%, from 30.4 to 37.5 (p < 0.001). Pain intensity decreased slightly, but not statistically significantly, from 7.1 to 6.8.

Conclusions

Peer group intervention for 6 weeks among municipal employees with chronic pain is partially effective. The number of areas of pain and pain self-efficacy were more sensitive indicators of change than the pain intensity. Any primary care unit with sufficient resources may implement the intervention.

1 Introduction

Pain is defined as chronic when pain lasts for at least 3 months, and the mechanisms, sometimes overlapping, have been attributed to nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic, i.e., centralized pain [1]. Pain perception is associated with interactions between various regions of the peripheral and central nervous systems that contribute to the overall experience of pain. In chronic pain, the nociplastic mechanism of the central nervous system often dominates [2].

The overall prevalence of chronic pain in 52 countries is estimated to be 27.5%, ranging from 9.9% in China to 50.3% in Morocco [3]. Chronic pain appears to increase by 10–20% over 10 years in women and older people between 2015 and 2025 in one study [4]. In primary health care, chronic widespread pain is a common reason for visits [5], and pain is associated with high use of health care services [5]. Consequently, chronic pain imposes an enormous personal and financial burden. The medical treatment of chronic pain is often insufficient, but biopsychosocial therapies, multidisciplinary treatment, including nonopioid pharmacotherapy, non-medical treatments, and other combined biopsychosocial interventions, are more effective [6].

Any disease or trauma seems to lead to chronic pain in the presence of several risk factors and repeated painful, stressful, and potentially harmful situations seem to change the function and the structure of pain-related brain areas [7]. The more often pain occurs, the more stress-related symptoms such as bowel dysfunction, sleep disorders, heartburn, rashes, dizziness, and fatigue [8]. Risk factors of chronic pain include, e.g., female gender, aging [9], surgery [10], MRI of low back pain (LBP) without red flags [11], fear avoidance [12], a physical trauma [13], manual labor [14], traumatic childhood [15], depression and anxiety [9], long-term opioid treatment [16], insomnia [17], and low level of resilience [18]. Prolonged or exaggerated stress response maintains cortisol dysfunction, widespread inflammation, and pain [19]. Despite the current guidelines for chronic pain, which primarily recommend non-medical treatment, in practice, the treatment is mainly biomedical [20].

Psychological treatments are effective for chronic pain because the risk of chronic pain and the pain experience is affected by cognitive and emotional factors, e.g., mental state, anxiety, fear, negative emotions, and anticipation of pain without co-occurring nociception [21]. The most common causes of chronic pain are prolonged perceived stress, lack of guidelines and instructions for chronic pain treatment, lack of social support, and the malfunctions of the stress management system [22]. Mindfulness may reduce stress, depression, anxiety, and pain and increase physical and emotional activities [39].

Peer support groups have evidence that they are effective in providing pain information, supporting pain management, workability, sense of control over symptoms, and disability despite chronic pain [24]. Also, web-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) interventions have published that they are more effective than usual care regarding disability, pain intensity, and self-efficacy in chronic LBP [25]. Also, patient-led goal setting and web-based CBT interventions have been shown to be more effective than usual in care regarding disability, pain intensity, and self-efficacy in chronic LBP [42,43]. Despite abundant published evidence of non-medical treatment of chronic pain, these interventions are underutilized.

We designed this study in the Occupational Health Helsinki (OH) for patients with chronic pain who had requested a peer group intervention. The study was targeted at employees with diverse pain and reduced work ability. The study protocol of the stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled intervention trial is published earlier [26]. In the setup of the pain peer group intervention, we included psychological and mindfulness-based methods for chronic pain recommended by guidelines and reviews [23]. This intervention aimed to reduce pain through a mindfulness-based stress reduction program, relaxation, and ACT- and CBT-based reduction of worrying about pain [26,27]. This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of pain-management group participation on pain intensity, pain self-efficacy, and the number of areas of pain.

2 Methods

2.1 Study settings

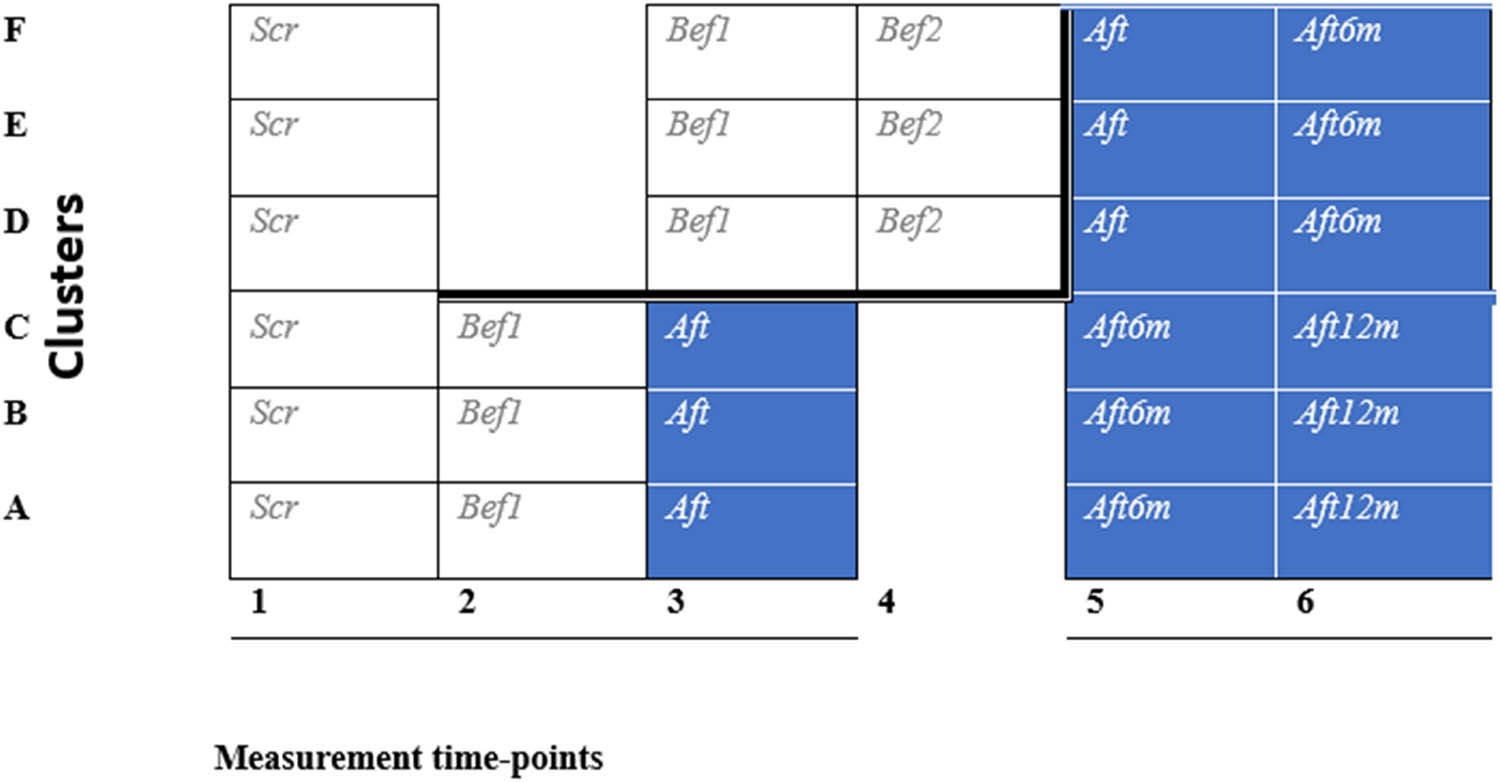

Our study was a stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial (Figures 1 and 2) conducted at OH, where the OH-using patients had requested a peer group intervention. Occupational health professionals (doctors, psychologists, physiotherapists, and nurses) recruited 60 patients with chronic pain to pain peer groups for 1 month in 2016, from mid-January to mid-February. Subjects who met the inclusion criteria and were interested in participating in the study were interviewed individually (H.G. or M.R.) and informed about the study, such as that participation is voluntary, and the study will not interfere with their use of occupational health care. After written informed consent, the interviewer randomized the blinded participants into three active and three waiting groups, 4–10 people per group (Figure 1). At the end of the interview, participants selected one, randomly selected, sealed envelope from all mixed, sealed, white envelopes, containing information from the randomization into one of six groups (A, B, C, D, E, and F).

Flow chart of the study. Scr = screening questionnaire, Bef1 = before intervention questionnaire for groups ABC and DEF (first before intervention questionnaire), DEF had a 5-month waiting period, Bef2 = before the intervention questionnaire for group DEF (second before the intervention questionnaire), Aft = immediately after the intervention questionnaire for groups ABC and DEF, Aft6m = 6 months after the intervention questionnaire for groups ABC and DEF, and Aft 12m = 12 months after the intervention questionnaire, only for half of the dusters, for groups ABC.

Study design of a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. Shaded cells represent after intervention periods, and blank cells represent before intervention/control periods. This trial has six data-collection points. Data-collection point questionnaires are in Figure 1.

Three groups, A, B, and C, started the intervention immediately and had six meetings from March 15, 2016, to April 21, 2016. Three groups, D, E, and F, started the intervention after 5 months of waiting, from August 16, 2016, to September 30, 2016. The 6th-month follow-up meeting for groups A, B, and C was in October, and the 12th-month follow-up meeting was in March. The 6th-month follow-up meeting for groups D, E, and F was also in March (Figure 1).

2.2 A stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial

In stepped wedge trials, the randomized clusters start intervention at different times; each participant is finally in the intervention. Randomization, as in this study, increases the validity of the study [31]. Many stepped wedge trials are analyzed using mixed model statistics including a random effect for cluster and fixed effects for period to account for secular trends, combining both vertical and horizontal effects of the intervention and control cluster comparisons. Randomization in stepped wedge trials is crucial due to the potential influences of time on the data, allowing for improved control over biases arising from secular trends [31].

2.3 Sample size calculation

In the presence of several outcomes, the sample size should be calculated for the outcome with the smallest difference in effect size before and after [28]. Salaffi et al. [29] stated that the minimal cut-off point measure of the Numeric Rating Scale of pain is −1.0 cm. When pain is 7.5 before intervention, and after intervention 6.5, the effect size is 13%. The difference in pain acceptance and fear-avoidance beliefs may even be larger than 15% pre- and post-intervention [29]. By using stepped wedge analysis on the study design matrix (six groups with four observations of each group) and with a 15% detectable minimum difference of the outcome (chronic pain, mean 7.14 on a scale from 0 to 10), we calculated the minimum group sample size to be 10 (when a-error is 0.05 and b-error 0.80) and total number of participants to be 60 [30].

2.4 Intervention

The intervention consisted of a pain management group that included peer support, pain education about the biopsychosocial nature of pain, and chronic pain. Before the intervention, there was a coffee break and a mindfulness exercise or relaxation. During the intervention, the homework included chapters from Helena Miranda’s book “Rethinking Pain” [34]. In the first meeting, the discussion subject was the pain management tools already in use; participants had used a wide range of different drug-free chronic pain treatment methods. In the second meeting, the discussion subject was pain mechanisms. The theme of the third meeting was (1) to do enjoyable things that would help improve pain management and (2) to discuss how pain affects social life. In the fourth meeting, the group leaders led discussions on the meaning of work, the future in life, work goals and professional development, and how to improve workability. At the fifth meeting, the topics were feelings; love, touch, sexuality, maintaining a positive attitude, and having a pet. In the last sixth meeting, participants discussed new tools to improve pain management, and they made a pain management plan. The themes in the 6th-month meeting were psychological flexibility, the importance of education and awareness skills, working on rehabilitation, and updating the pain management plan [26].

Interventions included CBT, mindfulness meditation, relaxation, ACT, homework, and the perspective of return to work [26].

CBT, which we used in this study, is based on talk therapy by psychotherapist Aaron Beck in 1964. It focuses on changing thoughts (cognitions) and actions (behavior), which is why it is called cognitive behavioral therapy [33].

In mindfulness practice, we are consciously present in the present moment, we welcome everything that comes to mind, and we immediately let it go [39].

ACT is more comprehensive than CBT including mindfulness practices, the pursuit of psychological flexibility by “unpacking” cognitions, using metaphor, and engaging in value-related activities [6].

2.5 Outcomes, variables, and covariates

2.5.1 Outcomes

We monitored the effect of the intervention by the number of areas of pain, pain intensity (visual analog scale [VAS]), and pain self-efficacy [26].

2.5.2 Other variables

The number of days you felt tense and restless.

2.5.3 Covariates

This study also examined covariates such as age, gender, job title, height, weight, physical exercise in the past week, exercise sessions and type of exercise, chronic diseases, medications, smoking, and years of smoking.

2.6 Questionnaires

We used a modified Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Short Questionnaire (OMPSQ) [35]. In OMPSQ, we changed the first question “How long have you had your current pain problem?” to “During the past week, where have you felt pain?” We asked for pain in ten areas: head, upper back, neck or shoulder area, lower back, shoulder or upper arm, hip or thigh, elbow or arm, knee or lower leg, wrist or hand, and ankle or foot. The intensity of pain during the past week was assessed by a VAS for pain [36] of OMPS [35]. The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire included ten items about coping with pain [37].

The number of observations (n) is greater than the number of participants due to the stepped-wedge design in which each participant receives the intervention. The questionnaires were filled out many times by the same participants (Table 2 and Figures 1 and 2).

2.7 Study population and recruitment

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Helsinki city employee,

Age 18–65 years, and

Any chronic pain, i.e., pain lasting for >3 months.

The study participant is willing to share their thoughts in a peer group intervention.

The risk of work disability was high in this population, i.e., ≥50 points (0–100) by the modified Örebro questionnaire [35].

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Malignant diseases such as cancer or severe mental illness,

Participation in another pain-management group,

A major current psychological or physical life crisis, and

Risk of work disability low, i.e., <50 points by the modified Örebro questionnaire.

2.8 Statistical analyses

We compared the post-intervention period with the pre-intervention (control) period and adjusted for clustering effect and calendar time. We used linear mixed-effects models to analyze data from repeated measures, and we adjusted the differences in the outcomes of interest between intervention and control periods for the clustering effect and calendar time. We used random effects to model the correlation between individuals in the same cluster and a fixed effect for the time interval.

3 Results

The demographics of the participants are in Table 1. Of the 60 participants who completed the before questionnaire (Bef 1), 80% attended all group intervention meetings. Seven participants canceled before the intervention: five in groups D, E, and F and two in groups A, B, and C. One participant did not cancel but did not participate in groups A, B, and C. Two participants in groups A, B, and C and two in groups D, E, and F participated in some intervention meetings but still needed to finish the intervention. The majority were female, and the mean age was 51 years; 37 participants were 50–62 years, and 23 were 29–49 years. The most common professional field was social and health care, or occupations including physically demanding jobs like a home nurse, home care nurse, early childhood educator, and office worker with mainly sedentary work (Table 1).

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Demographics and characteristics N = 48 | % | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 51 | |

| Women | 83 | |

| Occupational field | ||

| Social and health care or education | 63 | |

| Mean body mass index | 28 | |

| Smokers | 26 | |

| Felt depressed | 21 | |

| Not able to sleep for the pain | 38 | |

| I am feeling a sense of tension or restlessness | 48 | |

| Exercise at least 30 min; how many times a week? Mean number of times | 3 | |

| Exercise type | ||

| Walking | 55 | |

| Gym | 25 | |

| Cycling | 15 | |

| Swimming | 13 | |

| Aqua gym | 10 | |

| Medication | ||

| NSAID for pain | ||

| Every day | 47 | |

| A few times a week | 33 | |

| None | 17 | |

| Not answered | 3 | |

| Opioids | ||

| Every day | 13 | |

| A few times a week | 20 | |

| None | 63 | |

| Not answered | 3 | |

| #Neuromodulator for pain | ||

| Every day | 45 | |

| A few times a week | 5 | |

| None | 47 | |

| Not answered | 3 | |

| Other medication | 62 | |

| Medical condition altogether | 56 | |

| Diabetes or hypothyroidism | 20 | |

| Asthma | 18 | |

| Hypertension | 15 |

#Neuromodulator for pain; e.g., amitriptyline, duloxetine, and gabapentinoids.

At baseline, during the previous week, 21% of the participants had experienced a feeling of depression. Sleeping was disturbed due to pain in 38% of the participants, and 48% had been restless or tense the previous week. Almost half (45%) used daily chronic pain medication such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, duloxetine, pregabalin, and gabapentin. More than half of the group members had other chronic medical conditions, such as hypothyroidism, asthma, diabetes, or hypertension (Table 1). At the end of the intervention questionnaire (Aft) (Figures 1 and 2), had an open-ended question for comments, wishes, or feedback. Participants reported that they benefited primarily from peer support as well as the support of the group leaders.

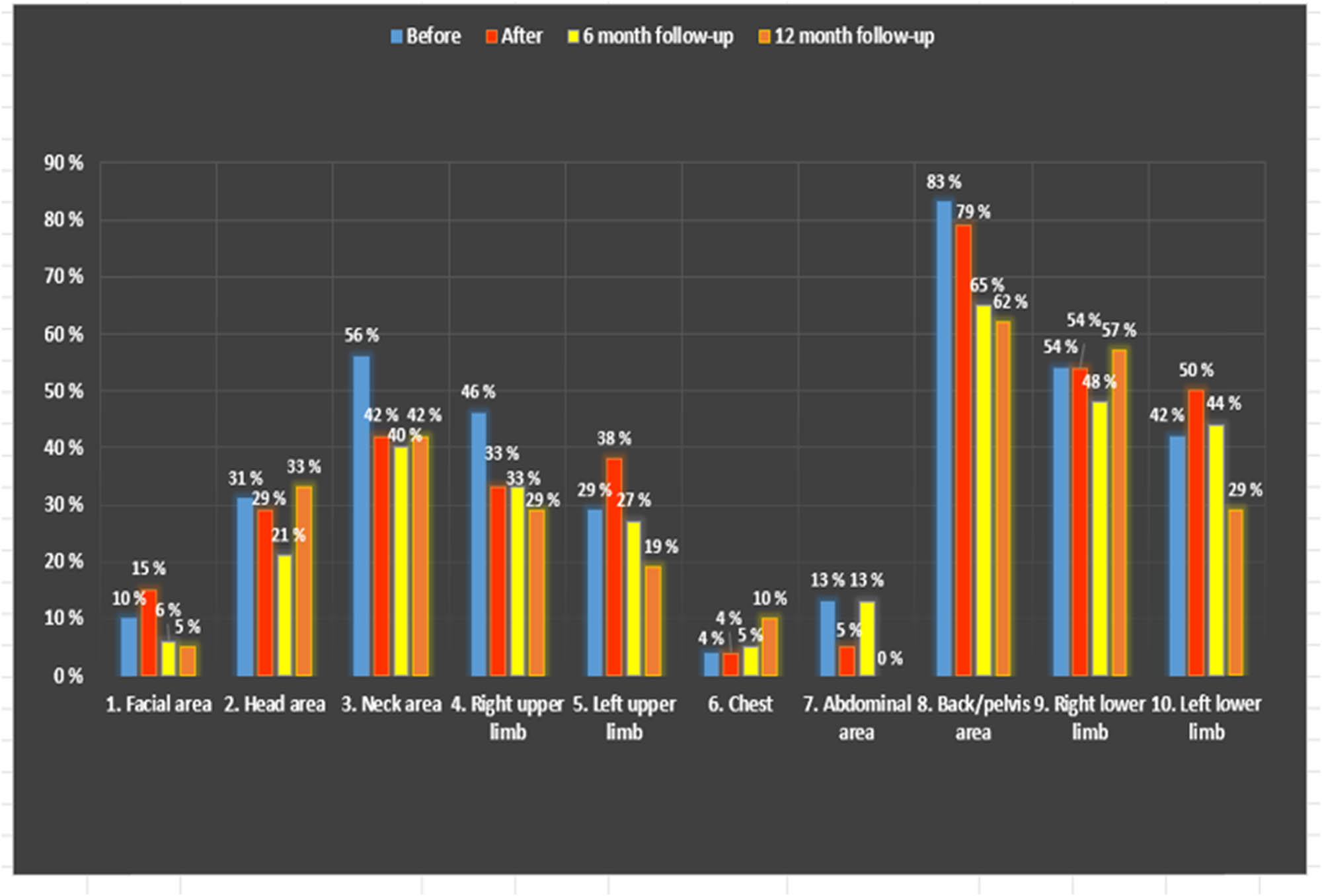

After the group intervention, the number of areas of pain decreased. Before the intervention, the mean number of pain areas was 5.96 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.44–6.49; p < 0.001), and after 6 weeks in the pain management group, it was 3.58. The decrease was 40%. The results remained the same during the follow-up period after intervention and after a 6–12-month follow-up (Figure 3) (95% CI: 3.05–4.11; p < 0.001).

Presentation of areas of pain before and after intervention, moreover after 6 and 12 months of the intervention. All six groups were on 6-month follow-up meetings, and we followed only the first three groups (A, B, and C groups) until 12 months.

Group interventions increased pain self-efficacy by 15% from 30.44 (0–60) to 37.49, an adjusted difference of 4,97; the results remained the same during the follow-up period after intervention and after 6–12 months follow-up (95% CI: 2.18–7.75; p < 0.001) (Table 2). The intervention effect on pain intensity was not significant. After adjustment for cross-sectional time-series data and clustering effect, the intervention showed a reduction of the mean pain intensity from 7.14 to 6.05 (VAS scale 0–10) (95% CI: −1.36 to −0.65; p < 0.001). However, after a further adjustment for a time interval, the decrease was no longer statistically significant (−0.34, 95% CI: −0.99 to 0.30; p = 0.30) (Table 2).

Outcomes differ between pre-intervention (control) and post-intervention periods

| outcome | Pre-intervention period | Post-intervention period | Crude difference | Adjusted difference* | Adjusted difference** | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (%) | SD | n | Mean (%) | SD | Mean (%) | p | Mean (%) | 95% CI | p | Mean (%) | 95% CI | p | |

| Pain intensity# | 142 | 7.14 | 1.38 | 109 | 6.05 | 2.15 | −1.09 | <0.001 | −1.01 | −1.36, −0.65 | <0.001 | −0.34 | 0.099, 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Self-efficacy | 82 | 30.4 | 9.20 | 109 | 37.49 | 9.50 | 7.05 | <0.001 | 7.09 | 6.08, 8.10 | <0.001 | 4.97 | 2.18, 7.75 | <0.001 |

| Self-efficacy (%) | 77 | 68.8 | 108 | 90.7 | 21.9% | <0.001 | 22.2% | 16.5, 27.9 | <0.001 | 14.9% | 6.2, 23.6 | <0.001 | ||

n = number of observations; SD = standard deviation; CI = confidence interval; #VAS = visual analog scale 0–10, self-efficacy mean = self-efficacy average 0–60%.

*Adjustment for panel data and clustering effect. **Adjustment for panel data, clustering effect, and time interval. N varies because we conducted different measurements in different phases, as in the stepped-wedge study setting description in Section 2 (Figure 1).

4 Discussion

4.1 Results

In this stepped wedge randomized study conducted in occupational health care, a long-term effect on multisite pain and its tolerability was achieved with the group intervention. The number of areas of pain decreased, and pain-related self-efficacy increased for 6–12 months.

Most (80%) of our study participants were satisfied with all nonpharmacological treatments, and only a few (20%) of open answers were critical. Some felt that the study intervention was too short, and some were a bit tired from the length and homework [38]. At the doctor’s office, strengthening the pain patient’s self-efficacy increases pain tolerance and reduces disability, workability, and functional ability [37].

4.2 Finnish OH

Finnish occupational health care is part of basic health care. Since its goal is to prevent and detect work-related health problems and support work ability, occupational health care personnel know the working conditions [32]. We conducted this study in an OH unit, where the staff had expertise in promoting group therapy, especially in supporting pain management measures.

4.3 Comparing the results with other intervention studies

In our stepped wedge study, we accepted all types of pain except cancer pain. However, an RCT by Turner et al. compared Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), CBT, and usual care in back pain patients, and CBT and MBSR increased self-efficacy [39]. Research results from Turner et al. are in line with our research results.

Also, the Lamb et al. study included 701 patients with subacute or chronic LBP. They had six CBT intervention meetings as we did, and pain self-efficacy improved significantly in the intervention group after a 12-month follow-up [40]. Research results from Lamb et al. are in line with our research results.

In addition, Carpenter et al. found that an online CBT intervention improved self-efficacy in chronic LBP patients post-intervention but not at the 6-week follow-up. The results parallel our research results; in our study, self-efficacy also improved after intervention and at the 6–12-month follow-up [41].

An Australian RCT by Nicholas et al. compared pain self-management (PSM), including CBT, exercises, and completing a home exercise chart with praise and encouragement. Furthermore, they compared exercise-attention control (EAC) including CBT, exercise, and clinical psychologists who offered discussions about living with pain. They included also a waiting list (WL) control like our study. EAC group participants were not encouraged to exercise or practice at home and completed no home exercise charts. WL controls started intervention (EAC/PSM group) 12 weeks later [42]. In the Nicholas et al. study, the PSM group increased pain self-efficacy after and at 1-month follow-up compared to the EAC group [42].

Also, in our study, the intervention included, e.g., CBT and homework, which participants discussed in every meeting, and they also discussed “exercise with joy” in the fifth meeting. In our study, the waiting list started intervention 5 months after the first three groups [26]. In addition, in our study, each participant completed their pain management plan with the encouragement and support of the group instructors, which probably strengthened their self-efficacy and praised and encouraged the group participants [26]. Research results from Nicholas et al. [42] parallel our research results, but in our study, self-efficacy increased up to the 6–12-month follow-up.

A German meta-analysis and systematic review by Bernardy et al. found that CBT in fibromyalgia patients had no effect on pain but an effect on pain self-efficacy at the median intervention duration of 9 weeks [43]. Bernardy et al. systematic review results parallel our research results, but our results lasted longer, 6–12 months.

4.4 Multisite pain

Common comorbidities with recurrent and widespread pain are depression and anxiety [9]. When pain, depression, and anxiety are simultaneously treated, pain may decrease, and high self-efficacy prevents depression and multisite pain [47]. Prolonged or frequent sick leave and physical incapacity weaken the financial situation of a pain patient, and a poor economic situation increases the risk of multisite pain [48]. Furthermore, opioids increase depressive symptoms, risk of disability, disability increases poverty, and the use of health services for patients with chronic pain [49]. Our participants had a high number of pain sites at baseline, 5.96, i.e., almost six different areas of pain on average. Our intervention increased self-efficacy, which may have influenced the number of areas of pain.

Comparing the results of areas of pain with other intervention studies is challenging, as our study is the only study in which psychological treatments reduced the number of areas of pain. One of the common causes of chronic pain, single and multisite pain, is perceived stress and stress reaction systems [22]. However, psychological treatments are effective for stress [50]. Because our study included stress-reducing psychological treatments, using CBT, mindfulness, and learning relaxation skills, they may have helped to reduce pain areas [26]. Patient selection, working-aged people, and OH settings with good therapeutical resources may have also influenced the results. Also, versatile intervention methods may have affected the results.

Only a few previous prospective studies have evaluated the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in treating multisite pain, and this is the first study in occupational health that has attempted to reduce multisite pain. Rundell et al. found multisite pain in back pain patients to predict disability, which is why reducing multisite pain is necessary. However, pain research has focused on individual pains [44]. The more extensive the pain, the more sick leave days, and work restrictions, so decreasing multisite pain should increase working capacity [45]. Physical work is a risk for multisite pain, especially in female-dominated fields and middle- or low-income earners [46]. Also, the most common occupation of the pain patients who participated in our study was physical, such as the social and health sector or nursing home nurse, home nurse, early childhood educator, and as well lighter office work, because office work mainly involves working in a static sitting position, a factor influencing chronic pain.

In other studies, the number of areas of pain has been reduced mainly by exercise, but in our intervention, we did not have structured exercise. However, pain management tools already in use; like exercise were discussed in pain management groups. In the Cantarero-Villanueva et al. study, 8 weeks of water exercise therapy reduced neck, shoulder, or arm pain in breast cancer survivors. However, widespread pressure pain hyperalgesia did not change significantly [51]. Reducing multisite pain is necessary because, in older age (50–64 years old), multisite pain increases the risk of poor workability and earlier retirement [52]. In addition to being associated with disability, multisite pain increases healthcare costs [53].

4.5 Pain

Measuring pain intensity in VAS daily is challenging because changes in psychological or functional parameters may invalidate or compensate for changes in pain intensity [54]. Patients with chronic pain have often suffered from disabling chronic pain for years or even their entire life [55], which is accompanied by many pain-related symptoms, such as depression and insomnia [56]. For example, the OMPSQ is a broader questionnaire with a VAS and questions about depression and insomnia [35].

A Cochrane review by Williams et al. studied chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults and found that CBT has minor to moderate effects on pain immediately after treatment but disappeared at a 6-month follow-up [23]. The results of a Cochrane review by Williams et al. are parallel to our research results.

Macea et al. conducted a systemic review and meta-analysis and found that web-based CBT interventions lead to modest reductions in chronic pain [25]. According to a systematic review by Skelly et al., CBT slightly improved fibromyalgia pain [20]. In addition, CBT improved the functional ability of the fibromyalgia patient, and the effects persisted to 1–6-month follow-up [20]. The results of a systematic review by Skelly et al. and Macea et al. are parallel to our study results.

RCT by Basler et al. studied chronic low back patients, for over 7 weeks. The intervention lasted 12 weeks, longer than in our study [57]. Basler et al. compared a combination of usual care and CBT to usual care and had a 6-month follow-up [57]. Both the Basler et al. study and our study had a waiting list group. In Basler’s study, those who received CBT and usual care reported less pain than those who received only usual care. Pain may have decreased more in Basler’s study than in our study because the duration of the intervention was more prolonged, 12 weeks [57].

5 Limitations

The main limitations which affect the generalizability of the results are the fact that all participants were asked to participate, and the number of participants was quite small. Also, the low number of intervention group participants may weaken the power of the study. We conducted our study in occupational health care with Helsinki employees, which also produces limitations on the generalization of the results. We chose the stepped-wedge design for practical and ethical reasons because the study population was relatively small, and we wanted to serve all participants. Most of the subjects were women because most of the communal employees are female, and chronic pain is more common in women [9]. The follow-up was relatively short. The authorities usually require that the maintenance phases of chronic pain treatment studies last at least 12 weeks to verify the effectiveness’s durability, and enough time is left to evaluate safety and tolerability [58].

6 Strengths

We chose a randomized controlled design with a stepped wedge setting. Excluding some participants from an intervention would be unethical, as happens in a traditional RCT [59]. A stepped wedge cluster RCT allows for minimal loss of study participants because all participants know they will eventually receive the intervention, motivating them to remain in the groups. A stepped wedge design will likely result in longer research time than traditional parallel planning, measured immediately after implementation [59].

In our study, the group leaders were experienced group tutors familiar with the biopsychosocial and cognitive approach; 80% participated in all group intervention meetings. According to patients with chronic pain, studies are usually too clinician oriented [60]. In our research, OH patients could express their views on the study’s design. The participants also discussed their pain management plans in group meetings and developed them with additional support from the leading expert of the pain peer group [26].

We chose methods based on scientific evidence. Combining peer group support, ACT, CBT, relaxation, and mindfulness in a peer group intervention, we saw responses in pain-related self-efficacy and reduced areas of pain.

7 Conclusion

This study provides evidence to support the use of relatively low threshold nonpharmacological approaches, such as a pain management group, to reduce areas of pain and increase self-efficacy. Increased pain self-efficacy and reduced pain areas are probably related to improvements in functional capacity related to chronic pain. Pain management groups with sufficient skills and resources are possible in any occupational health or primary care unit.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Helena Gyldén, the original principal investigator and group leader, for the research. The authors thank the senior researcher, Leena Kaila-Kangas, for her help and contribution to the research group. The authors thank Dr. Shiri Rahman (FIOH), the senior researcher, for the statistical analysis. The authors thank all the study participants and all professionals in Occupational Health Helsinki: the authors thank all the group leaders, occupational physician Helena Gyldén, OH nurse Airi Harjula, occupational psychologist Marjukka Laurola, OH nurse Tuula Tanskanen, OH nurse Miira Korjonen, and pain nurse Kaarina Onkinen. The authors thank Occupational Health Helsinki and the City of Helsinki. The authors thank the development project funded by the Finnish Work Environment Fund. The authors also thank the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health (FIOH) for being a research partner.

-

Research ethics: The study involving human subjects was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Helsinki University Hospital (approval number 395/13/03/00/15). Participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission.

-

Informed consent: Patients who met the inclusion criteria and were interested in participating in the study were interviewed individually (H.G. or M.R.) and informed about the study, such as that participation is voluntary, and the study will not interfere with their use of occupational health care. Afterward, participants wrote informed consent.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Research was funded by the Finnish Work Environment Fund, project number: 115395.

-

Data availability: Data available on request from the authors.

-

Artificial intelligence/Machine learning tools: Not applicable.

-

Study registration with Clinical Trials: We registered the study with Clinical Trials, US National Institutes of Health, number 115395, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=115395&Search=Search.

References

[1] Freynhagen R, Parada HA, Calderon-Ospina CA, Chen J, Rakhmawati Emril D, Fernández-Villacorta FJ. Current understanding of the mixed pain concept: a brief narrative review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:1011–8. 10.1080/03007995.2018.1552042.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Dydyk AM, Givler A. Central pain syndrome. [Updated 2023 February 19], StatPearls [Internet]; 2023 Jan, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553027/.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Zimmer Z, Fraser K, Grol-Prokopczyk H, Zajacova A. A global study of pain prevalence across 52 countries: examining the role of country-level contextual factors. J Pain. 2022;163:1740–50. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002557.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Guido D, Leonardi M, Mellor-Marsá B, Moneta M, Sanchez-Niubom A, Tyrovolas S. Pain rates in the general population for 1991–2015 and 10-year prediction: results from a multi-continent age-period-cohort analysis. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:1–11. 10.1186/s10194-020-01108-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Emilson C, Åsenlöf P, Demmelmaier I, Bergman S. Association between health care utilization and musculoskeletal Pain. A 21-year follow-up of a population cohort. Scand J Pain. 2020;20:533–43. 10.1515/sjpain-2019-0143.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Lumley M, Schubiner H. Psychological treatment of centralized Pain: an integrative assessment and treatment model. Psychosom Med. 2019;81:114–24. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000654.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Vartiainen N. Brain imaging of chronic pain. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. Dissertation. 2009. Available at: https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/23027.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Tschudi-Madsen H, Kjeldsberg M, Natvig B, Ihlebaek C, Dalen I, Kamaleri Y, et al. Strong association between non-musculoskeletal symptoms and musculoskeletal symptoms: results from a population survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:285. 10.1186/1471-2474-12-285.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, Alonso J, Karam E, Angermeyer MC, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain. 2008;9:883–91. 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Fletcher D, Stamer UM, Pogatzki-Zahn E, Zaslansky R, Tanase NV, Perruchoud C, et al. Chronic postsurgical pain in Europe: An observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:725–34. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000319.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Shraim BA, Shraim MA, Ibrahim AR, Elgamal ME, Al-Omari B, Shraim M. The association between early MRI and length of disability in acute lower back pain: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;24:983. 10.1186/s12891-021-04863-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Vlaeyen J, Linton S. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. J Pain. 2000;85:317–32. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Rivara F, Mackenzie E, Jurkovich G, Nathens A, Wang J, Scharfstein D. Incidence of pain in patients 1 year after major trauma. Arch Surg. 2008;143:282–8. 10.1001/archsurg.2007.61.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Saastamoinen P, Leino-Arjas M, Laaksonen P, Lahelma E. Socio-economic differences in the prevalence of acute, chronic and disabling chronic pain among ageing employees. J Pain. 2005;14:364–71. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.033.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Heim C, Newport D, Mletzko T, Miller A, Nemeroff C. The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:693–710. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Lueptow LM, Fakira AK, Bobeck EN. The contribution of the descending pain modulatory pathway in opioid tolerance. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:886. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00886. Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and Pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14:1539–52. 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Resilience: a new paradigm for adaptation to chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:105–12. 10.1007/s11916-010-0095-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1816–25. 10.2522/ptj.20130597.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, Turner JA, Friedly JL, Rundell SD, et al. Noninvasive nonpharmacological treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review. AHRQ WebM&M; 2018. PMID: 32338846. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556229/.10.23970/AHRQEPCCER209Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Bushnell MC, Ceko MČ, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:502–11. 10.1038/nrn3516.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Ahmad AH, Zakaria R. Pain in times of stress. Malays J Med Sci. 2015 December;22 (Spec Issue):52–61. PMID: 27006638; PMCID: PMC4795524.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Williams A, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic Pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:1–101. 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Linton S, Boersma K, Jansson M, Svärd L, Botvalde M. The effects of cognitive-behavioral and physical therapy preventive interventions on pain-related sick leave: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:109–19. 10.1097/00002508-200503000-00001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Macea D, Gajos K, Daglia Y, Fregni F. The efficacy of web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2010;11:917–29. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.06.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Reilimo M, Kaila-Kangas L, Shiri R, Laurola M, Miranda H. The effect of pain management group on chronic Pain and pain-related comorbidities and symptoms. A stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. A study protocol. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2020;18:100577. 10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100577.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KMG, Bohlmeijer. ET. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2011;152:533–42. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Hickey GL, Grant SW, Dunning J, Siepe. M. Statistical primer: sample size and power calculations—why, when and how? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54:4–9. 10.1093/ejcts/ezy169.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, Ciapetti. A. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:283–91. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Hemming K, Taljaard M. Sample size calculations for stepped wedge and cluster randomized trials: a unified approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:137–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Hargreaves JR, Prost A, Fielding KL, Copas AJ. How important is randomization in a stepped wedge trial? Trials. 2015;16:359. 10.1186/s13063-015-0872-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Kinnunen-Amoroso M, Liira J. Finnish occupational health nurses’ view of work-related stress: a cross-sectional study. Workplace Health Saf. 2014;62:105–12. 10.1177/216507991406200304.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Hofmann S, Asnaani A, Vonk I, Sawyer A, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:427–40. 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Helena M. Rethinking pain. 1st edn. Hammersmith Health Books; 2019. Rethinking Pain - Helena Miranda (9781781611326) | Adlibris bookshop. https://www.adlibris.com/fi/kirja/rethinking-pain-9781781611326.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Linton SJ, Nicholas M, MacDonal S. Development of a short form of the örebro musculoskeletal pain screening questionnaire. Spine. 2011;36:1891–5. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f8f775.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic Pain. I. aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. J Pain. 1983;16:87–101. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90088-X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Nicholas M. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: Taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:153–63. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Miranda H, Reilimo M, Kaila-Kangas L. Final rapport (in Finnish). Finnish Environment Fund, 2018. Pain management groups in Occupational health service 2018. 2018, https://www.tsr.fi/hankkeet-ja-tutkimustieto/kivunhallintaryhmat-tyoterveyshuollossa-satunnaistetun-kontrolloidun-interventiotutkimuksen-pilotti/.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Turner J, Anderson M, Balderson B, Cook A, Sherman K, Cherkin C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic lower limb pain: similar effects on mindfulness, catastrophe, self-efficacy, and acceptance in a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2016;157:2434–44. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000635.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Lamb S, Hansen Z, Lall R, Castelnuovo E, Withers E, Nichols V, et al. Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back Pain in primary care: a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:916–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62164-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Carpenter KM, Stoner SA, Mundt JM, Stoelb B. An online self-help CBT intervention for chronic lower back pain. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:14–22. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31822363db.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM, Wood BM, Murray R, McCabe R, et al. Self-management intervention for chronic pain in older adults: A randomised controlled trial. J Pain. 2013;154:824–35. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Bernardy K, Füber N, Köllner V, Häuser W. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome – a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1991–2005. 10.3899/jrheum.100104.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Rundell SD, Patel KV, Krook MA, Heagerty PJ, Suri P, Friedly JL, et al. Multisite pain is associated with long-term patient-reported outcomes in older adults with persistent back pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1898–906. 10.1093/pm/pny270.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Fernandes R, Burdorf A. Associations of multisite pain with healthcare utilization, sickness absence and restrictions at work. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;89:1039–46. 10.1007/s00420-016-1141-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Palumbo AJ, De Roos AJ, Cannuscio C, Robinson L, Mossey J, Weitlauf J, et al. Work characteristics associated with physical functioning in women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;15:424. 10.3390/ijerph14040424.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Sawatzky R, Ratner P, Richardson C, Washburn C, Sudmant W, Mirwaldt P. Stress and depression in students: the mediating role of stress management self-efficacy. Nurs Res. 2012;61:13–21. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31823b1440.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Bergman. S. Psychosocial aspects of chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:675–83. 10.1080/09638280400009030.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Valkanoff TA, Kline-Simon AH, Sterling S, Campbell C, Von Korff M. Functional disability among chronic pain patients receiving long-term opioid treatment. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2012;11:128–42. 10.1080/1536710X.2012.677653.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Weber M, Schumacher S, Hannig W, Barth J, Lotzin A, Schäfer I, et al. Long-term outcomes of psychological treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021;51:1420–30. 10.1017/S003329172100163X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-Lao C, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, López-Barajas IB, Del-Moral-Ávila R, de la-Llave-Rincón AI, et al. Effectiveness of water physical therapy on pain, pressure pain sensitivity, and myofascial trigger points in breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Pain Med. 2012;13:1509–19. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01481.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Miranda H, Kaila-Kangas L, Heliövaara M, Leino-Arjas P, Haukka E, Liira J, et al. Pain at multiple sites and its effects on work ability in a general working population. Occup Environ Med. 2009;67:449–55. 10.1136/oem.2009.048249.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Grimby-Ekman A, Gerdle B, Björk J, Larsson B. Comorbidities, intensity, frequency and duration of pain, daily functioning and health care seeking in local, regional, and widespread pain - a descriptive population-based survey (SwePain). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:165. 10.1186/s12891-015-0631-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Perrot S, Lantéri‐Minet M. Patient’s global impression of change in the management of peripheral neuropathic pain: Clinical relevance and correlations in daily practice. Eur J Pain. 2019;23:1117–28. 10.1002/ejp.1378.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. A survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Hush JM, Refshauge KM, Sullivan G, De Souza L, McAuley JH. Do numerical rating scales and the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire capture changes that are meaningful to patients with persistent back pain? Clin Rehabil. 2010;24:648–57. 10.1177/0269215510367975.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Basler H-D, Jäkle C, Kröner-Herwig B. Incorporation of cognitive-behavioral treatment into the medical care of chronic low back patients: a controlled randomized study in German pain treatment centers. Patient Educ Couns. 1997;31:113–24. 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00996-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Gewandter JS, Dworkin RH, Turk DC, McDermott MP, Baron R, Gastonguay MR, et al. Research designs for proof-of-concept chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2014;155:1683–95. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.05.025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:54. 10.1186/1471-2288-6-54.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Gardner T, Refshauge K, Mcauley J, Hübscher M, Goodall S, Smith L. Combined education and patient-led goal setting intervention reduced chronic low back pain disability and intensity at 12 months: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:1424. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100080.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- Abstracts presented at SASP 2025, Reykjavik, Iceland. From the Test Tube to the Clinic – Applying the Science

- Quantitative sensory testing – Quo Vadis?

- Stellate ganglion block for mental disorders – too good to be true?

- When pain meets hope: Case report of a suspended assisted suicide trajectory in phantom limb pain and its broader biopsychosocial implications

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation – an important tool in person-centered multimodal analgesia

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Exploring the complexities of chronic pain: The ICEPAIN study on prevalence, lifestyle factors, and quality of life in a general population

- The effect of peer group management intervention on chronic pain intensity, number of areas of pain, and pain self-efficacy

- Effects of symbolic function on pain experience and vocational outcome in patients with chronic neck pain referred to the evaluation of surgical intervention: 6-year follow-up

- Experiences of cross-sectoral collaboration between social security service and healthcare service for patients with chronic pain – a qualitative study

- Completion of the PainData questionnaire – A qualitative study of patients’ experiences

- Pain trajectories and exercise-induced pain during 16 weeks of high-load or low-load shoulder exercise in patients with hypermobile shoulders: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- Pain intensity in anatomical regions in relation to psychological factors in hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Opioid use at admittance increases need for intrahospital specialized pain service: Evidence from a registry-based study in four Norwegian university hospitals

- Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces temperature-evoked pain in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study

- Pain and health-related quality of life among women of childbearing age in Iceland: ICEPAIN, a nationwide survey

- A feasibility study of a co-developed, multidisciplinary, tailored intervention for chronic pain management in municipal healthcare services

- Healthcare utilization and resource distribution before and after interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation in primary care

- Measurement properties of the Swedish Brief Pain Coping Inventory-2 in patients seeking primary care physiotherapy for musculoskeletal pain

- Understanding the experiences of Canadian military veterans participating in aquatic exercise for musculoskeletal pain

- “There is generally no focus on my pain from the healthcare staff”: A qualitative study exploring the perspective of patients with Parkinson’s disease

- Observational Studies

- Association between clinical laboratory indicators and WOMAC scores in Qatar Biobank participants: The impact of testosterone and fibrinogen on pain, stiffness, and functional limitation

- Well-being in pain questionnaire: A novel, reliable, and valid tool for assessment of the personal well-being in individuals with chronic low back pain

- Properties of pain catastrophizing scale amongst patients with carpal tunnel syndrome – Item response theory analysis

- Adding information on multisite and widespread pain to the STarT back screening tool when identifying low back pain patients at risk of worse prognosis

- The neuromodulation registry survey: A web-based survey to identify and describe characteristics of European medical patient registries for neuromodulation therapies in chronic pain treatment

- A biopsychosocial content analysis of Dutch rehabilitation and anaesthesiology websites for patients with non-specific neck, back, and chronic pain

- Topical Reviews

- An action plan: The Swedish healthcare pathway for adults with chronic pain

- Team-based rehabilitation in primary care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: Experiences, effect, and process evaluation. A PhD synopsis

- Persistent severe pain following groin hernia repair: Somatosensory profiles, pain trajectories, and clinical outcomes – Synopsis of a PhD thesis

- Systematic Reviews

- Effectiveness of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation vs heart rate variability biofeedback interventions for chronic pain conditions: A systematic review

- A scoping review of the effectiveness of underwater treadmill exercise in clinical trials of chronic pain

- Neural networks involved in painful diabetic neuropathy: A systematic review

- Original Experimental

- Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in perioperative care: A Swedish web-based survey

- Impact of respiration on abdominal pain thresholds in healthy subjects – A pilot study

- Measuring pain intensity in categories through a novel electronic device during experimental cold-induced pain

- Robustness of the cold pressor test: Study across geographic locations on pain perception and tolerance

- Experimental partial-night sleep restriction increases pain sensitivity, but does not alter inflammatory plasma biomarkers

- Is it personality or genes? – A secondary analysis on a randomized controlled trial investigating responsiveness to placebo analgesia

- Investigation of endocannabinoids in plasma and their correlation with physical fitness and resting state functional connectivity of the periaqueductal grey in women with fibromyalgia: An exploratory secondary study

- Educational Case Reports

- Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series

- Regaining the intention to live after relief of intractable phantom limb pain: A case study

- Trigeminal neuralgia caused by dolichoectatic vertebral artery: Reports of two cases

- Short Communications

- Neuroinflammation in chronic pain: Myth or reality?

- The use of registry data to assess clinical hunches: An example from the Swedish quality registry for pain rehabilitation

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor For: “Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- Abstracts presented at SASP 2025, Reykjavik, Iceland. From the Test Tube to the Clinic – Applying the Science

- Quantitative sensory testing – Quo Vadis?

- Stellate ganglion block for mental disorders – too good to be true?

- When pain meets hope: Case report of a suspended assisted suicide trajectory in phantom limb pain and its broader biopsychosocial implications

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation – an important tool in person-centered multimodal analgesia

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Exploring the complexities of chronic pain: The ICEPAIN study on prevalence, lifestyle factors, and quality of life in a general population

- The effect of peer group management intervention on chronic pain intensity, number of areas of pain, and pain self-efficacy

- Effects of symbolic function on pain experience and vocational outcome in patients with chronic neck pain referred to the evaluation of surgical intervention: 6-year follow-up

- Experiences of cross-sectoral collaboration between social security service and healthcare service for patients with chronic pain – a qualitative study

- Completion of the PainData questionnaire – A qualitative study of patients’ experiences

- Pain trajectories and exercise-induced pain during 16 weeks of high-load or low-load shoulder exercise in patients with hypermobile shoulders: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- Pain intensity in anatomical regions in relation to psychological factors in hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Opioid use at admittance increases need for intrahospital specialized pain service: Evidence from a registry-based study in four Norwegian university hospitals

- Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces temperature-evoked pain in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study

- Pain and health-related quality of life among women of childbearing age in Iceland: ICEPAIN, a nationwide survey

- A feasibility study of a co-developed, multidisciplinary, tailored intervention for chronic pain management in municipal healthcare services

- Healthcare utilization and resource distribution before and after interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation in primary care

- Measurement properties of the Swedish Brief Pain Coping Inventory-2 in patients seeking primary care physiotherapy for musculoskeletal pain

- Understanding the experiences of Canadian military veterans participating in aquatic exercise for musculoskeletal pain

- “There is generally no focus on my pain from the healthcare staff”: A qualitative study exploring the perspective of patients with Parkinson’s disease

- Observational Studies

- Association between clinical laboratory indicators and WOMAC scores in Qatar Biobank participants: The impact of testosterone and fibrinogen on pain, stiffness, and functional limitation

- Well-being in pain questionnaire: A novel, reliable, and valid tool for assessment of the personal well-being in individuals with chronic low back pain

- Properties of pain catastrophizing scale amongst patients with carpal tunnel syndrome – Item response theory analysis

- Adding information on multisite and widespread pain to the STarT back screening tool when identifying low back pain patients at risk of worse prognosis

- The neuromodulation registry survey: A web-based survey to identify and describe characteristics of European medical patient registries for neuromodulation therapies in chronic pain treatment

- A biopsychosocial content analysis of Dutch rehabilitation and anaesthesiology websites for patients with non-specific neck, back, and chronic pain

- Topical Reviews

- An action plan: The Swedish healthcare pathway for adults with chronic pain

- Team-based rehabilitation in primary care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: Experiences, effect, and process evaluation. A PhD synopsis

- Persistent severe pain following groin hernia repair: Somatosensory profiles, pain trajectories, and clinical outcomes – Synopsis of a PhD thesis

- Systematic Reviews

- Effectiveness of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation vs heart rate variability biofeedback interventions for chronic pain conditions: A systematic review

- A scoping review of the effectiveness of underwater treadmill exercise in clinical trials of chronic pain

- Neural networks involved in painful diabetic neuropathy: A systematic review

- Original Experimental

- Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in perioperative care: A Swedish web-based survey

- Impact of respiration on abdominal pain thresholds in healthy subjects – A pilot study

- Measuring pain intensity in categories through a novel electronic device during experimental cold-induced pain

- Robustness of the cold pressor test: Study across geographic locations on pain perception and tolerance

- Experimental partial-night sleep restriction increases pain sensitivity, but does not alter inflammatory plasma biomarkers

- Is it personality or genes? – A secondary analysis on a randomized controlled trial investigating responsiveness to placebo analgesia

- Investigation of endocannabinoids in plasma and their correlation with physical fitness and resting state functional connectivity of the periaqueductal grey in women with fibromyalgia: An exploratory secondary study

- Educational Case Reports

- Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series

- Regaining the intention to live after relief of intractable phantom limb pain: A case study

- Trigeminal neuralgia caused by dolichoectatic vertebral artery: Reports of two cases

- Short Communications

- Neuroinflammation in chronic pain: Myth or reality?

- The use of registry data to assess clinical hunches: An example from the Swedish quality registry for pain rehabilitation

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor For: “Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population”