Abstract

Nanostructured boron compounds have emerged as one of the promising frontiers in boron chemistry. These species possess unique physical and chemical properties in comparison with classical small boron compounds. The nanostructured boron composites generally have large amounts of boron contents and thus have the potential to deliver significant amount of boron to the tumor cells, that is crucial for boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT). In theory, BNCT is based on a nuclear capture reaction with the 10B isotope absorbing a slow neutron to initiate a nuclear fission reaction with the release of energetic particles, such as lithium and helium (α particles), which travel the distance of around nine microns within the cell DNA or RNA to destroy it. The recent studies have demonstrated that the nanostructured boron composites can be combined with the advanced targeted drug delivery system and drug detection technology. The successful combination of these three areas should significantly improve the BNCT in cancer treatment. This mini review summarizes the latest developments in this unique area of cancer therapy.

Introduction

Nanomaterials are naturally occurring species, such as cage-structured carbon atoms of fullerenes and double helix nanostructures of biological DNA, which have been existed since the beginning of life on earth [1], [2]. They have been identified with the recent developments of techniques and instruments in analysis and metrology. In last decades, artificial nanomaterials with promising bioapplications, such as nanomaterial-based drug delivery agents and nanostabilizers of cosmetic ingredients, were significantly developed and, subsequently, various nanocomposites have been reported [3], [4], [5]. Following the advanced developments in pharmaceutical nanotechnology, nanomaterials have found vital applications of boron, especially in boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Theoretically, the BNCT is a binary cancer treatment based on a nuclear fusion reaction of a boron isotope (eq. 1) in which the 10B atoms are first selectively delivered to a tumor target, then the targeted areas containing 10B are irradiated with thermal neutrons of appropriate energy, where the 10B nucleus absorbs a neutron to form an excited 11B nucleus which immediately decays emitting an α-particle (4He2+) and a 7Li3+ ion with high energy. The linear energy transfer (LET) of these heavily charged particles has a range of about one cell diameter (5~9 μm) [11], [12]. This is recognized as an advantage because the cytotoxicity to the tissues caused by the radiation damage is confined to the boron containing cells only. Other advantages of BNCT include a large neutron capture cross section of 10B and its low radioactivity in comparison with other elementals such as hydrogen and nitrogen [11], [12]. In addition, it is highly recommended that the boron concentration of the surrounding healthy tissue should be less than 5 μg of 10B per gram of tissue to reduce the unnecessary damage caused by BNCT treatment [11], [12].

The ideal BNCT agents are expected to deliver sufficient 10B nucleus to a tumor target with high selectivity of tumor to normal tissues. In addition, antibodies are crucial to improve the drug selectivity [13]. While the 10B-enriched nanocomposites may deliver large amount of 10B and fluorescent species or magnetic components are useful in clinic diagnosis, an effective combination of the three components should lead to an ideal BNCT agent. Figure 1 shows one of the active boron delivery strategies in which iron oxide nanoparticles are active for MRI technology, boron oxide nanoparticles are 10B nucleus carrier and the targeting ligands are linked to the particle surface via a chemical bond. Boron nanoparticles can also be employed as boron carrier with the polymers to encapsulate them. Fluorescent species can also be attached for diagnosis. It is reasonable to anticipate an excellent performance of such novel agents. This review will cover most of the recent progresses in the special area of functional nanoparticles, nanotubes and polymer-based BNCT agents.

Multiple functional agents for BNCT treatment.

BNCT agents of functionalized nanoparticles

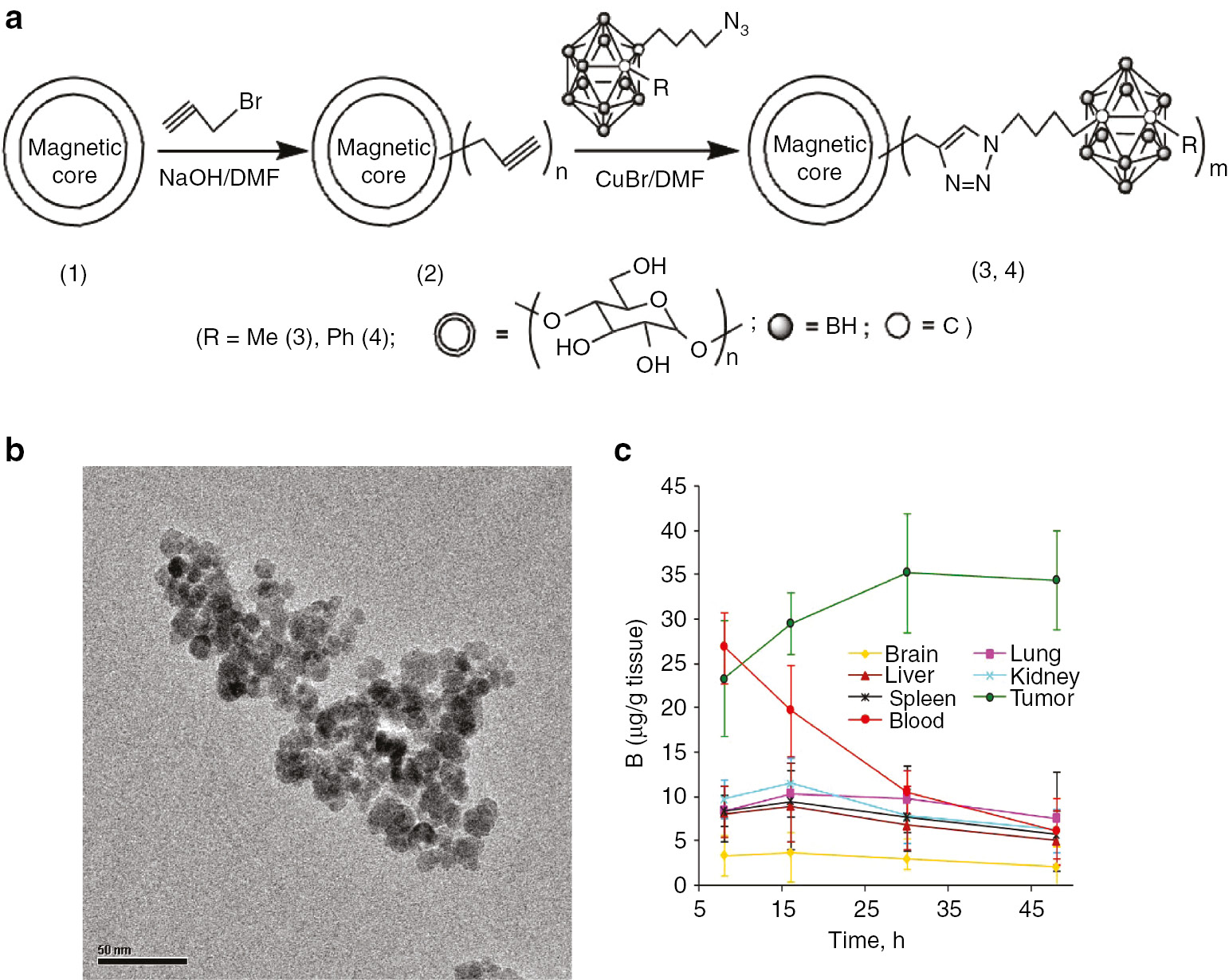

The functional nanoparticles, suitable for pharmaceutic applications, are generally organic surfaces that are smaller than 500 nm size. Concept of nanoparticle was first introduced by Peter Speiser in 1976 for pharmaceutical applications [14]. Following the development of biodegradable polymers, nanoparticles found broad clinical applications, primarily in oncology. Some nanoparticles-based drugs, such as Abraxane® for the treatment breast cancer, are already in clinical use [15]. In the area of BNCT, our report on the functionalized nanoparticles was the first one that was later followed by magnetic nanoparticles incorporating carborane containing matrix as shown in Fig. 2a [16]. A high boron concentration of 35.2 μg (B)/g breast tumor was achieved over a period of 30 h with a selectivity of five for tumor to blood ratio in the presence of an external magnet. It is well recognized that magnetic nanoparticles have important applications in pharmacy and oncology diagnosis, especially using as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. Magnetic nanoparticle-based drug carriers show the potential for improvement in delivering the drug amount with the help of an external magnetic field [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. Application of magnetic nanoparticles in BNCT treatment shows many advantages as there is no drug releasing issue when compared to other drug delivery systems. Therefore, the concept is particularly practical for BNCT application. It has been reported that boron enriched magnetic nanoparticles provided a high performing boron delivery [16]. Since the composite material contains the magnetic nanoparticles, it is potentially active for MRI technology, and thus MRI method can be used to monitor the delivery status. Thus, the magnetic nanocomposite is highly expected to show promising BNCT results with neutron irradiation in clinic treatments.

(a) Synthesis, (b) TEM image and (c) biodistribution of the encapsulated magnetic nanocomposites.

Inorganic nanoparticles of multiple components, Fe10BO3/Fe3O4/SiO2 and GdFeO3/Fe3O4/SiO2 have also been reported [25]. The nanoparticles were synthesized by a convenient pyrolysis method followed by a commonly used SiO2 coating procedure as shown in Fig. 3 [25]. The nanoparticles are spherical with a diameter of around 60 nm based on TEM results. The composites could be further functionalized by chemical modification of the silicon shell to improve their tumor selectivity. Unlike boron clusters and boron oxide nanoparticles, pure boron nanoparticles are potentially a promising boron carrying agent due to their significant boron content. Although boron nanoparticles can be made by different synthetic approaches, the commonly employed methods include chemical vapor deposition (CVD), pyrolysis, reduction in solution, thermal plasma, arc discharge and ball milling techniques [26], [27], [28], [29]. Recently, we have reported the synthesis of magnetic dopamine-functionalized boron nanoparticles using the ball milling method as shown in Fig. 4 [30]. The magnetic nanocomposites show a size range of 100–700 nm with an iron content of about 27 %, as weight percent, which are produced directly from the ball milling material, that is steel [30]. Accordingly, the boron powder was ball-milled in undecylenic acid and the resulting nanoparticles were coated with organic functionalities. Thus, the technology has the advantage of forming alloy and surface functionalization of commercially available boron powder, simultaneously [30]. Consequently, ball-milling can accomplish both the synthesis of boron nanoparticles and their functionalization, simultaneously in one step. However, the issues of controlling iron content and particle size distribution need to be addressed. Further investigation of this research led to construct magnetic nanocomposite comprising Fe3O4, polyethylene glycol (PEG, 1500 Da) and mono or bis(ascorbatoborate) as shown in Fig. 5 [31]. The nanocomposite showed a spherical morphology with an average size of 10–15 nm and exhibited a super paramagnetic behavior at 300 K [31]. Since the composites with combined ascorbic acid species are known to be useful as radical scavenging and anti-tumor agents, our newly prepared material has the potential application in magnetic biomedicine.

Synthesis of nanocomposites of Fe10BO3/Fe3O4/SiO2.

Synthesis of magnetic boron nanocomposites by ball-milling method.

Synthesis of magnetic boron nanocomposites, functionalized by ascorbatoborate.

Gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) are one type of the potential materials for various biomedical applications such as drug delivery [32]. Cioran et al. [33] prepared gold nanoparticles protected by a monolayer mercaptocarborane ligand (carboranyl thiol) with a mean particle diameter of 3.2 nm, [Au-NPs]@[1-S-1,2-closo-C2B10H11]−n. The nanocomposite showed a switchable solubility between water and nonpolar solvents by adjusting the electronic and ionic charge of the gold clusters. The composite could be uptaken by a human cancer line of HeLa cells and accumulated in vesicles within membranes [33]. However, the composite was relatively toxic and killed all cells after 24 h of incubation with them. The carboranylphosphinate ligand (Na[1-OPH(O)-1,7-closo-C2B10H11]) was used to stabilize CdSe quantum dots (CDs) and assembled a core-canopy nanostructure of {[CdSe-NPs]@[1-OPH(O)-1,7-closo-C2B10H11]−n}@Cl− /[(Caprylyl)3N]+ [34]. The structure was designed to trap Cl− ions and it exhibited a kinetic fluorescence switching optical property [34].

BNCT agents of functionalized nanotubes

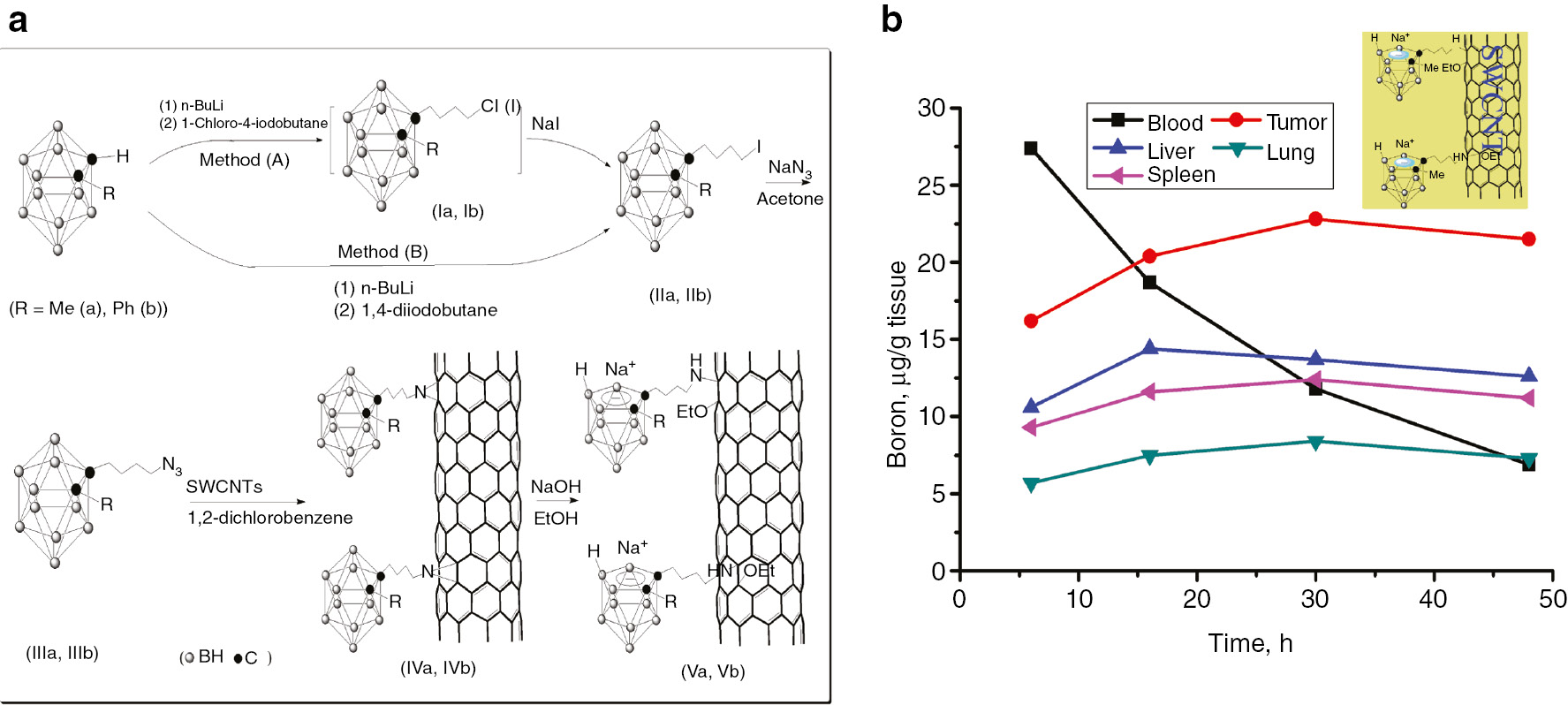

Single and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (CNTs), boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) and boron nanotubes (BNTs) are the new nanomaterials with a tubular morphology. The CNTs have found pharmaceutical applications in drug delivery [35], [36], [37], [38] as they possess high surface area and enhanced cellular uptake and can be functionalized with various bioactive components, such as nucleic acids and proteins. The functionalized CNTs are recognized and used as biocompatible and low toxicity drug carrier [35], [36], [37], [38]. Zhu et al. [39] first reported the application of CNTs for BNCT. Accordingly, the carborane clusters were linked to the surface of the single-walled CNTs through a short alkyl bridge as shown in Fig. 6a. According to the report, a high boron concentration of 21.5 μg/g tumor was reached within the 48-h period after administration (Fig. 6b) with a selectivity of >3:1 ratio of tumor-to-blood [39]. It was also reported that retention in tumor tissue was higher than in normal tissues. The resulting nanocomposite also demonstrated good water solubility, an important property for BNCT drug delivery [7], [8]. Cabana et al. [40] functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes with cobaltabisdicarbollide anions by forming a short link of (SWCNT-C(O)-[O(CH2)2]2-O-metallaborane). This material showed an outstanding water dispersibility. Same strategy was used to prepare graphene oxide-cobaltabisdicabollide and graphene oxide-closo-dodecaborate nanohybrides [41]. The nanohybrids were reported to be well-dispersed in water without decomposition.

Synthesis (a) and biodistribution (b) of carborane-linked CNTs.

Boron nitride nanotube (BNNT) is a structural analog of carbon nanotube. It represents a type of innovative and extremely attractive nanomaterials with comparable thermal conductivity and mechanical stiffness of CNTs. However, BNNT shows significantly different properties in comparison with CNTs. A pristine BNNT is an electrical insulator and is more thermally and chemically stable [42], [43], [44], [45]. The BNNTs may have promising aerospace applications, particularly of the 10B-enriched BNNTs, due to their IR strength and radiation-shielding of spallation neutrons from cosmic rays [46]. Applications of the BNNTs in nanomedicine have been investigated and well developed in the last decades [47] to confirm that the BNNTs are potentially useful materials in biomedical and nanomedicinal applications, including drug delivery, therapeutics and tissue regeneration [47].

The BNNT is also a potentially promising BNCT agent due to its relatively simple chemical composition (B and N) that can be functionalized for specific tumors [48], [49], [50], [51]. In addition, the synthesis of the 10B-enriched BNNTs is experimentally feasible. Menichetti and coworkers have synthesized Fe-containing BNNTs by a convenient milling process with the Fe content of about 1.5 wt% [51]. Subsequently, the BNNT nanocomposite was employed as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) by encapsulating with poly(L-lysine) and measured in homogeneous aqueous dispersions at 3T with different concentration. It was reported that the composite has a good potential for negative MRI contrast agent, particularly as T(2) contrast-enhancement agents [51]. However, the controlling of the iron content in the nanocomposite remained a big challenge. Nakamura’s group has demonstrated that BNNT showed antitumor effects towards B16 melanoma cells in the presence of thermal neutron irradiation [52]. The measurement was carried out in an aqueous suspension stabilized by polymer DSPE-PEG2000. It was reported that the composite of BNNT-DSPE-PEG2000 selectively accumulated in B16 cells approximately three times higher than current clinically used sodium borocaptate (BSH). The neutron-dose dependent surviving fractions are shown in Fig. 7 [52]. It was observed that BNNT-DSPE-PEG2000 nanocomposite effectively killed more B16 cells than those with BSH alone, probably due to the higher boron accumulation in B16 cells [52]. The results suggested that the BNNT-DSPE-PEG2000 composite is a potentially important BNCT delivery agent.

Clonogenic cell-survivals after irradiation in vitro using thermal neutron beams. BNNT-PEG2000 (100 ppm natural boron); BSH (sodium borocaptate, 100 ppm natural B).

A highly water dispersible nanostructured boron nitride (BN) in the transient phase from two dimensional hexagonal sheets to nanotubes was synthesized at a relatively low temperature. The nanostructured BN shows low cytotoxicity on various cell lines [Hela(cervical cancer), human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) and human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7)]. Therefore, the BN can be used for BNCT applications [53]. Ferreira and coworkers [54] have investigated the potential application of BNNT for BNCT in cancer treatment. It was found that BNNTs were selectively accumulated in the HeLa cell line (ATCC CCL-2) and demonstrated high cell killing effect in the presence of a thermal neutron flux of around 6.6×108 n·cm−2·s−1 as shown in Fig. 8 [54]. Thus, the results provided the evidence for the suitability of BNNTs for BNCT applications.

Cytotoxic effects of BNNTs on HeLa cells with quantification of dead cells (% of total cells).

Although the boron nanotubes have been synthesized [55], [56], their metallic conductivities, irrespective of its diameters and chirality, have been investigated and could also be a useful material for BNCT applications due to their extremely high boron contents, their high-yield synthetic approach still needs to be improved to make their use very practical either for biomedical applications or as a dopant in semiconductor devises.

BNCT agents of functionalized nanospherical polymers and dendrimers

Both naturally occurring and artificially functionalized polymers have been commonly used in medicinal chemistry as drug delivery agents [57], [58], [59], [60]. While dendrimers have been well explored as nanocarriers in drug delivery and diagnosis to reduce the drug-dose, toxicity and tumor resistance [60], various functionalized polymers, such as liposome and dendrimers, have been employed as boron carriers for BNCT applications [7], [8]. Accordingly, Chen and coworkers have reported a multifunctional nanocomposite, comprising polyethylene glycol (PEG 2000) and carborane clusters, labeled or tagged with fluorescence rhodamine dye [61]. It was reported that the nanocomposite could form spherical particles in aqueous solution and quickly absorbed by the cells and have a high stability in the bloodstream. The unique properties of the composite materials enable them to be used as a targeting vehicle. Subsequently, Teixidor’s group has employed other methodologies to prepare water-soluble nanoscale BNCT agent by integrating metallacarborane anion in the targeted molecules [61]. A globular dendritic macromolecule, [NMe4]6[1,2,8,9,10,12{(3,3′-Co-{8-(C4H8O2-1,2-C2B9H10-1′,2′-C2B9H11}-O(CH2)3}6-1,2-closo-C2B10H6], containing multiple anionic metallacarborane clusters at the o-carborane periphery has been synthesized. This water-soluble high boron rich molecule is expected to be a useful BNCT carrier in the near future [62].

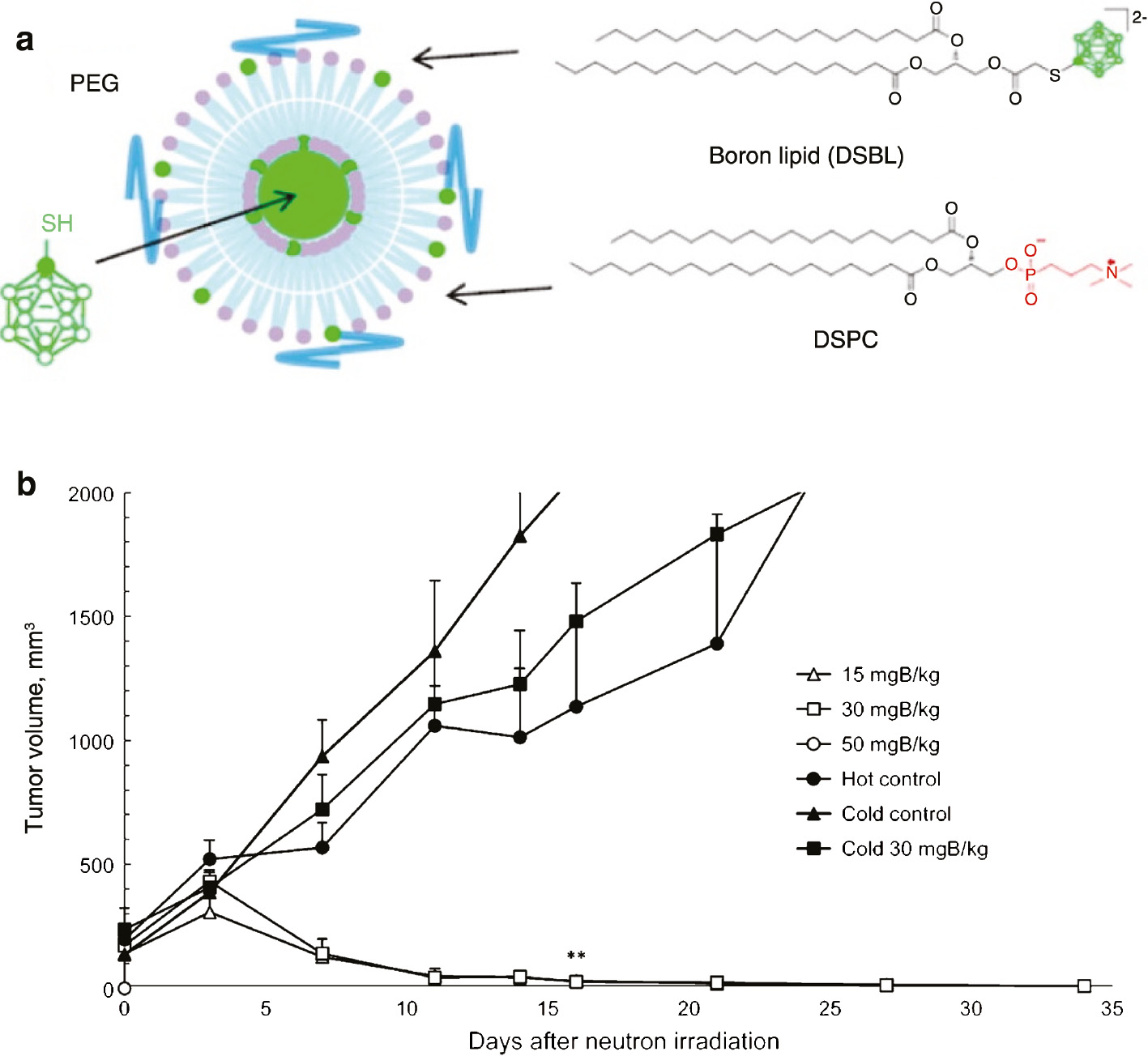

The liposomes (LP) are natural nanomaterials comprising of phospholipids and cholesterol with enormous diversity and flexibility. They are considered as “green vehicles” in drug delivery due to their extremely biocompatible, biodegradable and non-toxic characteristics. In addition, liposomes can be conveniently functionalized to engineer different chemical and physical characteristics. It has been consistently demonstrated that the uptake of drugs, encapsulated in liposomes, is higher in tumor cells when compared to that in the surrounding normal cells [7], [8]. Koganei et al. [63] have reported the synthesis of encapsulated mercaptoundecahydrododecaborate (BSH) with 10 % distearoyl boron lipid (DSBL) liposomes with a high boron content (boron/phosphorus ratio is 2.6) and, subsequently, used as BNCT carrier (Fig. 9a), thus demonstrating a high performance in boron delivery to tumor with the boron concentration of 174 ppm reaching at a dose of 50 mg B/kg. It was also reported that the functionalized liposomes exhibited excellent antitumor efficacy combining with a thermal neutron irradiation [(1.5~1.8)×1012 neutrons/cm2] [63]. As shown in Fig. 9b, the tumors in mice (Balb/c, female, 6 weeks old, 14–20 g) bearing colon 26 solid tumors have completely disappeared 3 weeks after thermal neutron irradiation at an injection dose of 15 mg B/kg. It has been claimed that the encapsulated BSH with 10 % DSBL liposomes is potentially a promising BNCT candidate based on these results.

Structures of distearoylphosphatidylcholine (DSPC) and boron ion cluster lipids (a), and tumor volumes in mice bearing colon 26 solid tumor (b).

Kang et al. [64] demonstrated the conjugation of liposomes (LP, 124 nm) with a αvβ3 ligand and a cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic acid-tyrosine-cysteine peptide (c(RGDyC)-LP) (1 % molar ratio) through thiol-maleimide coupling as shown in Fig. 10. When these functionalized liposomes are linked to a boron cage, they exhibited high potential for specific boron delivery to glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). Accordingly, A 70–80 % cell death was achieved with a thermal neutron flux of 4.5×107 n·cm−2·s−1 in 3 h [64]. A nanocomposite of the boron compound-attached poly(L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLLGA) was reported by Takeuchi et al. [65]. The nanoparticles have the diameters of 100–150 nm in which the 100-nm particles reached a boron concentration of 113.9±15.8 μg/g of tissue in the tumor-bearing mice after 8 h of composite drug administration [65]. The tumor/blood ratio of boron concentration was greater than 5 after 8–12 h of injection. In addition, the boron atoms were excreted mainly in the urine. These results indicated that such type of nanoparticles is extremely useful for BNCT applications [65].

TEM images (a) and drug release profiles (b) from liposomes (LP) and c(RGDyC)-LP formulations. Release studies were performed at 37 °C in isotonic PBS (pH 7.4).

Conclusions and future perspectives

The BNCT is a promising treatment for cancers and other diseases. Following the advanced developments in nanotechnology and construction of new neutron sources in Asia, it is believed that BNCT application will have a new hope in the horizon. After exploring decades of research, the BNCT carriers shifted from small molecules to nanocomposites due to their extremely high boron contents, that is crucial for BNCT treatment. The nanocomposites can penetrate the tumor vasculature through its leaky endothelium and accumulate in the solid tumors. The nanoparticulate carriers can be passive or active in targeting [66], [67], but the nanocomposites containing targeting ligands, such as antibody to binding with specific receptors on the tumor cells and endothelium, may significantly improve the selectivity for the delivery of boron agents, while reducing the toxic side-effects and enhancing delivery of poorly soluble or sensitive boron carrier molecules. Such type of functional nanocomposites represents the future BNCT carriers.

However, there are very limited metabolic studies and excretion of nanostructured boron compounds. More efforts should be devoted to study the pharmacokinetics of the BNCT agents to understand their potentially hazardous effects on human health. As described above, combination of fluorescent species and/or magnetic nanoparticles should enable the functionalized nanocomposite to be monitored. Preliminary investigation of nanocomposites in BNCT application should enable us to develop the “Magic Bullets” to selectively deliver various boron reagents intracellularly. Nevertheless, it is necessary to conduct further in vivo studies and clinical trials using all of the developed nanoparticulate BNCT carriers. It is believed that nanocomposites could revive our hopes to find a cure for cancer through BNCT drug discovery pipeline.

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON-16), Hong Kong, 9–13 July 2017.

Acknowledgments

Y. Zhu thanks the School of Pharmacy, Macau University of Science and Technology in Macau for financial support. NSH thanks the National Science Foundation for their continuous support through many grants beginning 1984 until 2013. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

References

[1] W. Clavin. https://www.noao.edu/news/2011/pr1103.php, Aug 16, 2011.10.1080/13549839.2011.627320Suche in Google Scholar

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DNA_nanotechnology.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] https://euon.echa.europa.eu/products-and-articles-made-by-or-with-nanomaterials.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] R. Koen, B. Kevin, D. Jo, C. De. S. Stefan. Chem. Soc. Rev.43, 444 (2014).10.1039/C3CS60299KSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] https://www.perkinelmer.com/pdfs/downloads/Nanopharma_009561_01_WTP.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Y. Zhu, N. S. Hosmane. Coord. Chem. Rev.293–294, 357 (2015).10.1016/j.ccr.2014.10.002Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Y. Zhu, N. S. Hosmane. Future Med. Chem.5, 705 (2013) and references therein.10.4155/fmc.13.47Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] N. S. Hosmane, J. A. Maguire, Y. Zhu, M. Takagaki. Boron and Gadolinium Neutron Capture Therapy for Cancer Treatment. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., Singapore, 52 (2012).10.1142/8056Suche in Google Scholar

[9] R. F. Barth, M. G. Vicente, O. K. Harling, W. S. Kiger, K. J. Riley, P. J. Binns, F. M. Wagner, M. Suzuki, T. Aihara, I. Kato, S. Kawabata. Radiat Oncol.7, 146 (2012).10.1186/1748-717X-7-146Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] H. Nakamura. Future Med. Chem.5, 715 (2013).10.4155/fmc.13.48Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] A. H. Soloway, W. Tjarks, B. A. Bauman, F. G. Rong, R. F. Barth, I. M. Codogni, J. G. Wilson. Chem. Rev.98, 1515 (1998).10.1021/cr941195uSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] R. G. Fairchild, V. P. Bond. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.11, 831 (1985).Suche in Google Scholar

[13] C. Sellmann, A. Doerner, C. Knuehl, N. Rasche, V. Sood, S. Krah, L. Rhiel, A. Messemer, J. Wesolowski, M. Schuette, S. Becker, L. Toleikis, H. Kolmar, B. Hock. J. Biol. Chem.291, 25106 (2016).10.1074/jbc.M116.753491Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] G. Birrenbach, P. P. Speiser. J. Pharm. Sci.65, 1763 (1976).10.1002/jps.2600651217Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Y. Zhu, Y. Lin, Y. Z. Zhu, J. Lu, J. A. Maguire, N. S. Hosmane. J. Nanomater.2010, 409320 (2010).10.1155/2010/409320Suche in Google Scholar

[16] http://www.abraxane.com/mbc/.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] C. Alexiou, W. Arnold, R. J. Klein, F. G. Parak, P. Hulin, C. Bergemann, W. Erhard, S. Wagenpfeil, A. S. Lübbe. Cancer Res.60, 6641 (2000).Suche in Google Scholar

[18] H. Lee, M. K. Yu, S. Park, S. Moon, J. J. Min, Y. Y. Jeong, H.-W. Kang, S. Jon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12739 (2007).10.1021/ja072210iSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] E. Allard, C. Passirani, J.-P. Benoit. Biomaterials30, 2302 (2009).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] F. K. H. Landeghem, K. Maier-Hauff, A. Jordan, K.-T. Hoffmann, U. Gneveckow, R. Scholz, B. Thiesen, W. Brück, A. Deimling. Biomaterials30, 52 (2009).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.044Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] M. Sincai, D. Ganga, M. Ganga, D. Argherie, D. Bica. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.293, 438 (2005).10.1016/j.jmmm.2005.02.074Suche in Google Scholar

[22] B. Chertok, B. A. Moffat, A. E. David, F. Yu, C. Bergemann, B. D. Ross, V. C. Yang. Biomaterials29, 487 (2008).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.050Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] R. Tietze, J. Zaloga, H. Unterweger, S. Lyer, R. P. Friedrich, C. Janko, M. Pottler, S. Durr, C. Alexiou. Biochem. Biophy. Res. Commun.468, 463 (2015).10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] M. Arruebo, R. Fernández-Pacheco, M. R. Ibarra, J. Santamaría. Nanotoday2, 22 (2007).10.1016/S1748-0132(07)70084-1Suche in Google Scholar

[25] S. Gao, X. Liu, T. Xu, X. Ma, Z. Shen, A. Wu, Y. Zhu, N. S. Hosmane. ChemistryOpen2, 88 (2013).Suche in Google Scholar

[26] P. Z. Si, M. Zhang, C. Y. You, D. Y. Geng, J. H. Du, X. G. Zhao, X. L. Ma, Z. D. Zhang. J. Mater. Sci.38, 689 (2003).10.1023/A:1021832209250Suche in Google Scholar

[27] B. J. Bellott, W. Noh, R. G. Nuzzo, G. S. Girolami. Chem. Commun. 3214 (2009).10.1039/b902371bSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] X. He, S. Joo, H. Liang. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol.2, 20 (2013).10.1149/2.021301jssSuche in Google Scholar

[29] P. L. Perez, B. W. McMahon, S. Schneider, J. A. Boatz, T. W. Hawkins, P. D. McCrary, P. A. Beasley, S. P. Kelley, R. D, Rogers, S. L. Anderson. J. Phys. Chem. C117, 5693 (2013).10.1021/jp3100409Suche in Google Scholar

[30] O. Icten, N. S. Hosmane, D. A. Kose, B. Zumreoglu-Karan. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.642, 828 (2016).10.1002/zaac.201600181Suche in Google Scholar

[31] O. Icten, N. S. Hosmane, D. A. Kose, B. Zumreoglu-Karan. New J. Chem.41, 3646 (2017).10.1039/C6NJ03894HSuche in Google Scholar

[32] R. C. V. Lehn, P. U. Atukorale, R. P. Carney, Y. Yang, F. Stellacci, D. J. Irvine, A. Alexander-Kata. Nano Lett.13, 4060 (2013).10.1021/nl401365nSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] A. M. Cioran, A. D. Musteti, F. Teixidor, Z. Krpetic, I. A. Prior, Q. He, C. J. Kiely, M. Brust, C. Viñas. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 212 (2012).10.1021/ja203367hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] A. Saha, E. Oleshkevich, C. Vinas, F. Teixidor. Adv. Mater.3, 1704238 (2017).10.1002/adma.201704238Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] A. Bianco, K. Kostarelos, M. Prato. Current Opin. Chem. Biol.9, 674 (2005).10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.10.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] B. S. Wong, S. L. Yoong, A. Jagusiak, T. Panczyk, H. K. Ho, W. H. Ang, G. Pastorin. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.65, 1964 (2013).10.1016/j.addr.2013.08.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] C. Fabbro, H. Ali-Boucetta, T. D. Ros, K. Kostarelos, A. Bianco, M. Prato. Chem. Commun.48, 3911 (2012).10.1039/c2cc17995dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] A. Valavanidis, T. Vlachogianni. J. Pharma. Rep.1, 105 (2016).Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Y. Zhu, T. P. Ang, K. Carpenter, J. Maguire, N. Hosmane, M. Takagaki. J. Am. Chem. Soc.127, 9875 (2005).10.1021/ja0517116Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] L. Cabana, A. Gonzalez-Campo, X. Ke, G. V. Tendeloo, R. Nunez, G. Tobias. Chem. Eur. J.21, 16792 (2015).10.1002/chem.201503096Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] J. Cabrera-Gonzalez, L. Cabana, B. Ballesteros, G. Tobias, R. Nunez. Chem. Eur. J.22, 5096 (2016).10.1002/chem.201505044Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] X. Blase, A. Rubio, S. G. Louie, M. L. Cohen. Europhy. Lett. (EPL).28, 335 (1994).10.1209/0295-5075/28/5/007Suche in Google Scholar

[43] G. Dmitri, C. M. F. J. Pedro, M. Masanori, B. Yoshio. J. Mater. Chem.19, 909 (2009).Suche in Google Scholar

[44] W.-Q. Han, W. Mickelson, J. Cumings, A. Zettlaet. Appl. Phys. Lett.81, 1110 (2002).10.1063/1.1498494Suche in Google Scholar

[45] D. Golberg, Y. Bando, C. C. Tang, C. Y. Zhi. Adv. Mater.19, 2413 (2007).10.1002/adma.200700179Suche in Google Scholar

[46] J. Yu, Y. Chen, R. G. Elliman, M. Petravic. Adv. Mater.18, 2157 (2006).10.1002/adma.200600231Suche in Google Scholar

[47] G. Ciofani, V. Mattoli. Boron Nitride Nanotubes in Nanomedicine, Elsevier Inc, Amsterdam, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] C. H. Lee, S. Bhandari, B. Tiwari, N. Yapici, D. Zhang, Y. K. Yap. Molecules21, 922 (2016).10.3390/molecules21070922Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] G. Ciofani, V. Raffa, A. Menciassi, A. Cuschieri. Nanoscale Res. Lett.4, 113 (2009).10.1007/s11671-008-9210-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] D. A. Buzatu, J. G. Wilkes, D. Miller, J. A. Darsey, T. Heinze, A. Birls, R. Beger. US Patent 20110027174 A1 (2011).Suche in Google Scholar

[51] L. Menichetti, D. De Marchi, L. Calucci, G. Ciofani, A. Menciassi, C. Forte. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes69, 1725 (2011).10.1016/j.apradiso.2011.02.032Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] H. Nakamura, H. Koganei, T. Miyoshi, Y. Sakurai, Y. Sakurai, k. Ono, M. Suzuki. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.25, 172 (2015).10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] B. Singh, G. Kaur, P. Singh, K. Singh, B. Kumar, A. Vij, M. Kumar, R. Bala, R. Meena, A. Singh, A. Thakur, A. Kumar. Sci. Rep.6, 35535 (2016).10.1038/srep35535Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] T. H. Ferreira, M. C. Miranda, Z. Rocha, A. S. Leal, D. A. Gomes, E. M. B. Sousa. Nanomaterials (Basel)7, pii: E82 (2017).10.3390/nano7040082Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] F. Liu, C. Shen, Z. Su, X. Ding, S. Deng, J. Chen, N. Xu, H. Gao. J. Mater. Chem.20, 2197 (2010).10.1039/b919260cSuche in Google Scholar

[56] D. Ciuparu, R. F. Klie, Y. Zhu, L. Pfefferle. J. Phys. Chem. B108, 3967 (2004).10.1021/jp049301bSuche in Google Scholar

[57] M. Goldberg, R. Langer, X. Jia, J. Biomater. Sci. Polym.18, 241 (2007).10.1163/156856207779996931Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] K. Miyata, R. J. Christie, K. Kataoka. React. Funct. Poly.71, 227 (2011).10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2010.10.009Suche in Google Scholar

[59] A. Srivastava, T. Yadav, S. Sharma, A. Nayak, A. Kumari, N. Mishra. J. Biosci. Med.4, 62762 (2016).Suche in Google Scholar

[60] F. Liko, F. Hindré, E. Fernandez-Megia. Biomacromol.17, 3103 (2016).10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00929Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] G. Chen, J. Yang, G. Lu, P. C. Liu, Q. Chen, Z. Xie, C. Wu. Mol. Pharm.11, 3291 (2014).10.1021/mp400641uSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] F. Teixidor, A. Pepiol, C. Viñas. Chemistry21, 10650 (2015).10.1002/chem.201501181Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] H. Koganei, M. Ueno, S. Tachikawa, L. Tasaki, H. S. Ban, M. Suzuki, K. Shiraishi, K. Kawano, M. Yokoyama, Y. Maitani, K. Ono, H. Nakamura. Bioconjugate Chem.24, 124 (2013).10.1021/bc300527nSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] W. Kang, D. Svirskis, V. Sarojini, A. L. McGregor, J. Bevitt, Z. Wu. Oncotarget.8, 3661 (2017).10.18632/oncotarget.16625Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[65] I. Takeuchi, K. Nomura, K. Makino. Colloids Surf. B Biointer.159, 360 (2017).10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.08.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] V. P. Torchilin. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol.197, 3 (2010).Suche in Google Scholar

[67] S. Hirsjärvi, C. Passirani, J. P. Benoit. Curr. Drug. Discov. Technol.8, 188 (2011).10.2174/157016311796798991Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON XVI)

- Conference papers

- Palladium-promoted sulfur atom migration on carboranes: facile B(4)−S bond formation from mononuclear Pd-B(4) complexes

- When diazo compounds meet with organoboron compounds

- Transition-metal complexes with oxidoborates. Synthesis and XRD characterization of [(H3NCH2CH2NH2)Zn{κ3O,O′,O′′-B12O18(OH)6-κ1O′′′}Zn(en)(NH2CH2CH2NH3)]·8H2O (en=1,2-diaminoethane): a neutral bimetallic zwiterionic polyborate system containing the ‘isolated’ dodecaborate(6−) anion

- Novel sulfur containing derivatives of carboranes and metallacarboranes

- Metal–metal bonding in deltahedral dimetallaboranes and trimetallaboranes: a density functional theory study

- Nanostructured boron compounds for cancer therapy

- Heterometallic boride clusters: synthesis and characterization of butterfly and square pyramidal boride clusters*

- Influence of fluorine substituents on the properties of phenylboronic compounds

- Copper-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative borylation: new pathway to optically active heterocyclic compounds

- Borenium and boronium ions of 5,6-dihydro-dibenzo[c,e][1,2]azaborinine and the reaction with non-nucleophilic base: trapping of a dimer and a trimer of BN-phenanthryne by 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine

- The electrophilic aromatic substitution approach to C–H silylation and C–H borylation

- Recent advances in B–H functionalization of icosahedral carboranes and boranes by transition metal catalysis

- closo-Dodecaborate-conjugated human serum albumins: preparation and in vivo selective boron delivery to tumor

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Risk assessment of effects of cadmium on human health (IUPAC Technical Report)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON XVI)

- Conference papers

- Palladium-promoted sulfur atom migration on carboranes: facile B(4)−S bond formation from mononuclear Pd-B(4) complexes

- When diazo compounds meet with organoboron compounds

- Transition-metal complexes with oxidoborates. Synthesis and XRD characterization of [(H3NCH2CH2NH2)Zn{κ3O,O′,O′′-B12O18(OH)6-κ1O′′′}Zn(en)(NH2CH2CH2NH3)]·8H2O (en=1,2-diaminoethane): a neutral bimetallic zwiterionic polyborate system containing the ‘isolated’ dodecaborate(6−) anion

- Novel sulfur containing derivatives of carboranes and metallacarboranes

- Metal–metal bonding in deltahedral dimetallaboranes and trimetallaboranes: a density functional theory study

- Nanostructured boron compounds for cancer therapy

- Heterometallic boride clusters: synthesis and characterization of butterfly and square pyramidal boride clusters*

- Influence of fluorine substituents on the properties of phenylboronic compounds

- Copper-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative borylation: new pathway to optically active heterocyclic compounds

- Borenium and boronium ions of 5,6-dihydro-dibenzo[c,e][1,2]azaborinine and the reaction with non-nucleophilic base: trapping of a dimer and a trimer of BN-phenanthryne by 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine

- The electrophilic aromatic substitution approach to C–H silylation and C–H borylation

- Recent advances in B–H functionalization of icosahedral carboranes and boranes by transition metal catalysis

- closo-Dodecaborate-conjugated human serum albumins: preparation and in vivo selective boron delivery to tumor

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Risk assessment of effects of cadmium on human health (IUPAC Technical Report)