Abstract

The skeletal bonding topology as well as the Re=Re distances and Wiberg bond indices in the experimentally known oblatocloso dirhenaboranes Cp*2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 (Cp*=η5Me5C5, n=8–12) suggest formal Re=Re double bonds through the center of a flattened Re2Bn−2 deltahedron. Removal of a boron vertex from these oblatocloso structures leads to oblatonido structures such as Cp2W2B5H9 and Cp2W2B6H10. Similar removal of two boron vertices from the Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 (n=8–12) structures generates oblatoarachno structures such as Cp2Re2B4H8 and Cp2Re2B7H11. Higher energy Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 (Cp=η5-C5H5, n=8–12) structures exhibit closo deltahedral structures similar to the deltahedral borane dianions BnHn2−. The rhenium atoms in these structures are located at adjacent vertices with ultrashort Re≣Re distances similar to the formal quadruple bond found in Re2Cl82− by X-ray crystallography. Such surface Re≣Re quadruple bonds are found in the lowest energy PnRe2Bn−2Hn−2 structures (Pn=η5,η5-pentalene) in which the pentalene ligand forces the rhenium atoms to occupy adjacent deltahedral vertices. The low-energy structures of the tritungstaboranes Cp3W3(H)Bn−3Hn−3 (n=5–12), related to the experimentally known Cp*3W3(H)B8H8, have central W3Bn−3 deltahedra with imbedded bonded W3 triangles. Similar structures are found for the isoelectronic trirhenaboranes Cp3Re3Bn−3Hn−3. The metal atoms are located at degree 6 and 7 vertices in regions of relatively low surface curvature whereas the boron atoms are located at degree 3–5 vertices in regions of relatively high surface curvature. The five lowest-energy structures for the 11-vertex tritungstaborane Cp3W3(H)B8H8 all have the same central W3B8 deltahedron and differ only by the location of the “extra” hydrogen atom. The isosceles W3 triangles in these structures have two long ~3.0 Å W–W edges through the inside of the deltahedron with the third shorter W–W edge of ~2.7 to ~2.8 Å corresponding to a surface deltahedral edge.

Introduction

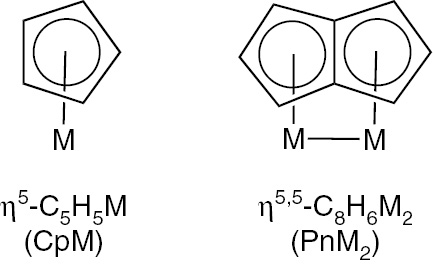

Imbedding transition metal vertices into a borane polyhedron leads to an interesting variety of metallaborane structures first studied by Hawthorne [1], Grimes [2], and their coworkers approximately a half-century ago. Using external cyclopentadienyl (Cp=η5-C5H5) or pentamethylcyclopentadienyl (Cp*=η5-Me5C5) groups bonded to the transition metal vertices provides robust Cp–M or Cp*–M bonds to complete the coordination sphere of the transition metal vertices. This leads to dimetallaboranes of the types Cp2M2Bn−2Hn−2 and Cp*2M2Bn−2Hn−2 exhibiting considerable thermodynamic and kinetic stability.

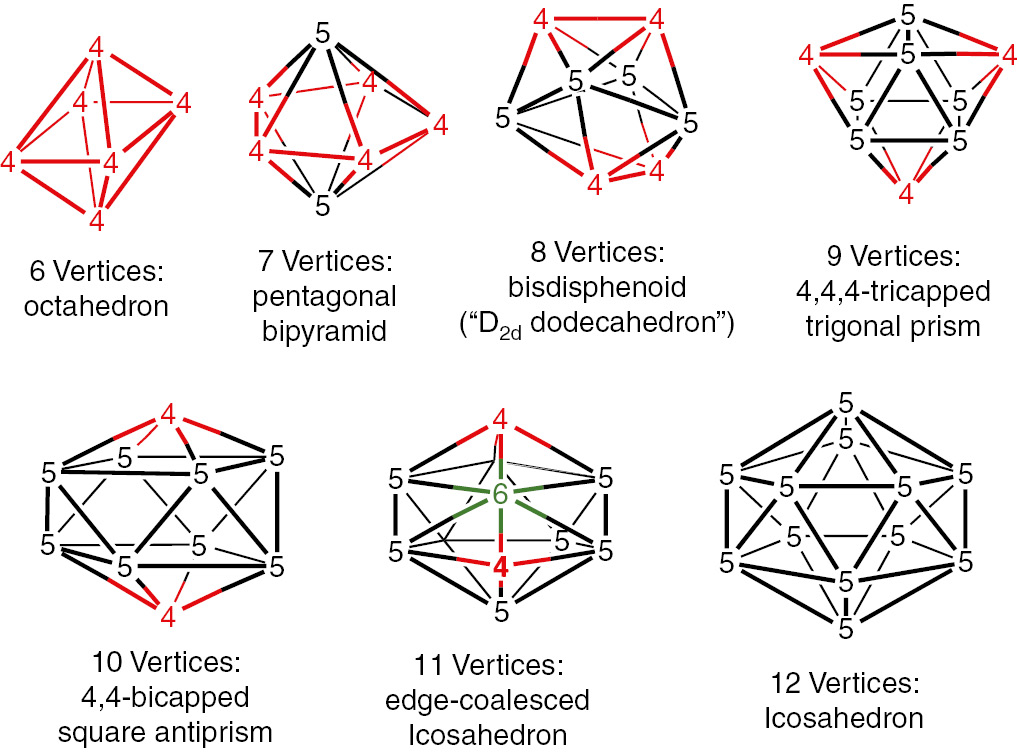

The basic building blocks of the borane anions BnHn2− and isoelectronic carboranes CBn−1Hn− and C2Bn−2Hn as well as their substitution products are the most spherical closo deltahedra in which all faces are triangles and the vertices are as nearly equal as possible (Fig. 1) [3], [4] For structures typically encountered experimentally having from 6 to 12 vertices such deltahedra have only degree 4 and 5 vertices except for the 11-vertex closo deltahedron, which is required by topology to have a single degree 6 vertex [5].

The most spherical closo deltahedra found in boranes and carboranes showing the vertex degrees with degree 4, 5, and 6 vertices in red, black, and green, respectively.

The electron bookkeeping in polyhedral borane derivatives follows the Wade–Mingos rules [6], [7], [8] which assume that each vertex atom contributes three orbitals to the skeletal bonding. Using this approach a B–H vertex contributes two electrons to the skeletal bonding and a C–H vertex contributes three electrons to the skeletal bonding. Skeletal electron counts obtained by this procedure are conveniently called Wadean skeletal electrons. The most spherical closo deltahedra (Fig. 1) are favored for n-vertex structures containing 2n+2 Wadean skeletal electrons.

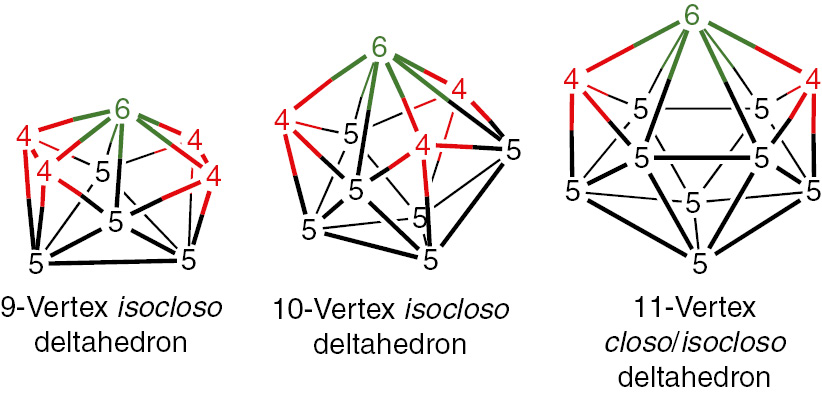

The early work on metallaboranes frequently resulted in structures containing CpCo vertices, which are donors of two Wadean skeletal electrons similar to B-H vertices. However, in other cases introduction of transition metal vertices into borane polyhedra, especially those of early transition metals with fewer valence electrons, can lead to deviations from the sphericity of the closo deltahedra. This arises from the preference of transition metals for vertices of larger degrees than carbon and boron vertices. For example isocloso deltahedra [9] providing a degree 6 vertex for the transition metal atom (Fig. 2) are found in metallaboranes having only 2n Wadean skeletal electrons [10], [11], [12], [13].

The isocloso deltahedra providing a degree 6 vertex for a transition metal atom. Since the 11-vertex closo deltahedron already has a degree 6 vertex, the closo and isocloso 11-vertex deltahedra are the same.

In order to explore the extent of metallaborane chemistry, particularly metallaboranes containing two or more transition metal vertices, we have undertaken an extensive theoretical study on possible such structures. Our protocol involves the initial screening of a large number of possible isomers using a relatively rapid density functional theory method with the B3LYP functional, a 6-31g(d) double zeta basis set for light atoms, and an SDD basis set for heavy atoms [14], [15], [16], [17]. In many cases we are able to examine hundreds of possible isomers for a given metallaborane stoichiometry to find a relatively small number of low-energy structures. We then refine the relative energies and geometries for this relatively small number of lowest energy isomers using the M06-L function with a larger 6-311G(d,p) triple zeta basis set for light atoms and the same SDD basis set for heavy atoms [18]. In some critical cases we also use the more computationally intensive single point coupled cluster DLPNO-CCSD(T) method [19].

Dimetallaboranes

The first dimetallaboranes prepared by Hawthorne and co-workers [1] included species such as Cp2Co2C2B6H8 with the correct 2n+2 skeletal electrons (=22 for n=10) for the 10-vertex closo deltahedron, namely the bicapped square antiprism (Fig. 1) [20]. In the early studies the Hawthorne group also synthesized the iron derivative Cp2Fe2C2B6H8 having only 2n skeletal electrons shown by X-ray crystallography to have a central Fe2C2B6 deltahedron later interpreted as the 10-vertex isocloso deltahedron (Fig. 2) with a degree 6 vertex for the iron atom [21].

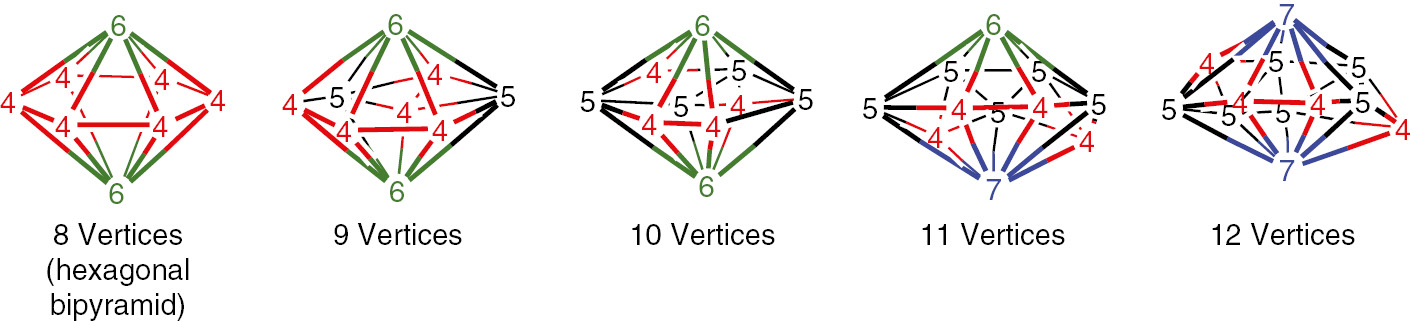

The experimentally known dirhenaboranes of the type Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 are even more hypoelectronic, having only 2n 4 apparent Wadean skeletal electrons [22], [23], [24], [25]. The central Re2Bn−2 deltahedra (Fig. 3) deviate strongly from sphericity with relatively low curvature at the two approximately polar degree 6 and/or 7 rhenium vertices and relatively high curvature at the remaining n 2 equatorial degree 4 and 5 boron vertices. They thus resemble oblate (flattened) ellipsoids rather than spheres and, for this reason, have been called oblatocloso deltahedra [26].

The oblatocloso deltahedra found in the dirhenaboranes Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2.

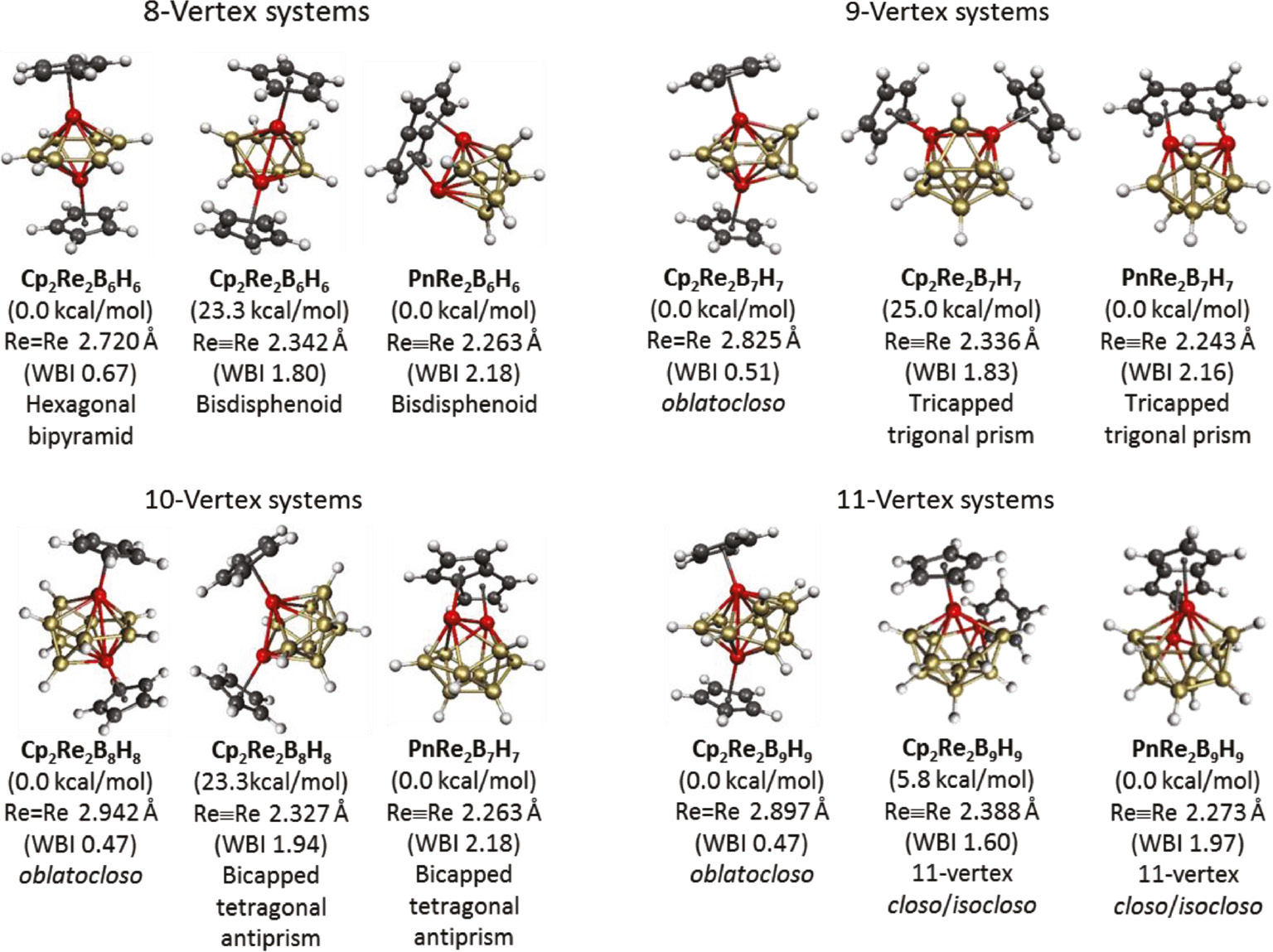

The dirhenaboranes Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 have been the subject of theoretical studies owing to their unusual structures [27], [28]. Such studies gratifyingly show the experimentally known oblatocloso dirhenaborane structures to be the lowest energy structures (Fig. 4). However, higher energy isomers were found having central Re2Bn2closo deltahedra with adjacent rhenium atoms and short Re–Re distances suggesting formal multiple bonds. Such structures become the lowest energy structures in related pentalenedirhenaboranes PnRe2Bn−2Hn−2 (Pn=η5,η5-pentalene) in which the pentalene ligand uses each of its five-membered rings to bond to a rhenium atom so that the two rhenium atoms are forced to stay in adjacent positions (Fig. 5) [29].

Structures of the dirhenaboranes Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 and PnRe2Bn−2Hn−2.

Comparison of the bonding of a cyclopentadienyl (Cp) ligand to one rhenium atom with that of a pentalene (Pn) ligand to two rhenium atoms.

The lowest energy PnRe2Bn−2Hn−2 structures are seen to have central Re2Bn−2closo deltahedra with short Re≣Re distances of 2.24–2.26 Å very similar to that of the formal Re≣Re quadruple bond length of 2.24 Å in K2Re2Cl8 [30]. Such metal–metal multiple bonds provide a way of drawing otherwise non-bonding metal electrons into the skeletal bonding. This can be clarified by considering the skeletal bonding topology in polyhedral boranes and metallaboranes (Table 1).

Skeletal bonding topology in closo, isocloso, and oblatocloso boranes and metallaboranes.

| Type | Surface bonding | Core bonding | Total electrons/orbitals | Wadean skeletal electrons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| closo | n×2c–2e | nc–2e | ||

| 2n electrons | 2 electrons | 2n+2 electrons | 2n+2 electrons | |

| 2n orbitals | n orbitals | 3n orbitals | ||

| isocloso | n×3c–2e | None | ||

| 2n electrons | – | 2n electrons | 2n electrons | |

| 3n orbitals | – | 3n orbitals | ||

| oblatocloso | n×3c–2e | M=M double bond | ||

| 2n electrons | 4 electrons | 2n+4 electrons | 2n −4 electrons | |

| 3n orbitals | 4 orbitals | 3n+4 orbitals* | deg 5 M vertices |

Consider first closo boranes having n vertices. Two of the three internal (skeletal) orbitals of each vertex atom are used for the surface bonding leading to n two-center two-electron (2e–2c) bonds distributed on the polyhedral surface as a canonical structure. The actual surface bonding, requiring 2n skeletal electrons for these 2c–2e bonds, can then be considered as a resonance hybrid of all such canonical structures. The remaining internal orbitals on each vertex atom overlap in the center of the deltahedron to form a n-center two-electron bond. This bonding scheme accounts for the 2n+2 Wadean skeletal electrons in closo deltahedral boranes [31], [32], [33].

A related bonding topology for isocloso metallaboranes uses all three internal orbitals from each vertex atom to form n three-center two-electron surface bonds in a canonical structure [34]. Again the actual surface bonding, requiring 2n skeletal electrons for these 3c–2e bonds, can be considered as a resonance hybrid of all such canonical structures. This bonding scheme leaves no orbitals for any type of core bonding so that the isocloso metallaboranes have only 2n Wadean skeletal electrons.

A reasonable bonding topology for the oblatocloso dirhenaboranes deviates from the Wade–Mingos scheme [6], [7], [8] by assuming that the CpRe vertices use five rather than three orbitals for the skeletal bonding (Table 1) [27]. This is reasonable owing to the relatively low surface curvature at the rhenium vertices. Providing five skeletal orbitals makes each CpRe vertex a source of four skeletal electrons rather than the zero skeletal electrons that it would provide if using only three orbitals for skeletal bonding in the Wade–Mingos scheme [6], [7], [8]. Although the n-vertex oblatocloso dirhenaboranes appear to be highly hypoelectronic with only 2n−4 Wadean skeletal electrons, they are best interpreted as 2n+4 actual skeletal electron systems. Forming n surface 3c–2e bonds in the oblatocloso dirhenaboranes similar to those in the isocloso metallaboranes discussed above leaves four “extra” skeletal electrons for an internal Re=Re double bond. The two “extra” orbitals on each rhenium atom beyond the three required for the surface bonding are exactly the orbitals needed for such a Re=Re double bond.

The CpM (and Cp*M) vertices found in many metallaboranes use three metal orbitals for bonding to the Cp ring and another three orbitals for a Wadean skeletal electron bonding scheme [5], [6], [7]. Assuming that the metal atom has the favored 18-electron configuration, this leaves three of the nine orbitals in the sp3d5 metal valence orbital manifold with non-bonding lone pairs. Some of these lone pair electrons can be drawn into the skeletal bonding if the valence metal atoms form multiple bonds. Thus increasing the formal bond order of a surface metal–metal single bond to a quadruple bond draws six additional electrons into the skeletal bonding. In this way, Cp2Re2Bn−2Bn−2 and PnRe2Bn−2Bn−2 systems with 2n−4 Wadean skeletal electrons and a surface Re≣Re quadruple bond can have the actual 2n+2 skeletal electrons required for a closo deltahedral structure.

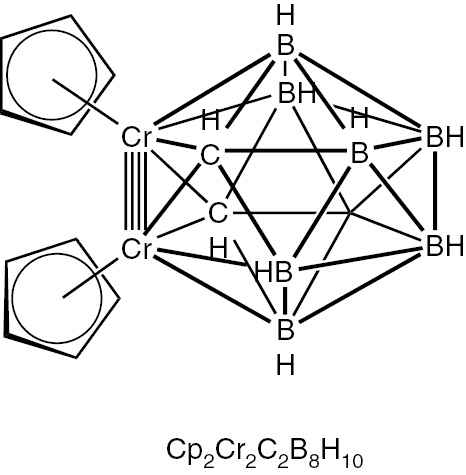

At the time that we published our work on dimetallaboranes with metal–metal multiple bonds we were not aware of any experimental examples of such species. However, we subsequently found that we (as well as the reviewers of our papers) had overlooked the paper by Stone and coworkers in 1983 on the synthesis of an icosahedral dichromadicarbaborane Cp2Cr2C2B8H10 by the reaction of chromocene with C2B9H12 (Fig. 6). [35]. X-ray crystallography of Cp2Cr2C2B8H10 shows an ultrashort Cr≣Cr distance of 2.272 Å very close to the Cr≣Cr distance of 2.288 Å for the chromium–chromium quadruple bond in anhydrous chromium(II) acetate dimer, Cr2(OAc)4 [36]. Note that Cp2Cr2C2B8H10 is valence isoelectronic with Cp2Re2B10H10 exhibiting an albeit high-energy structure with a formal Re≣Re quadruple bond.

The experimentally known dichromadicarbaborane suggested to have a formal Cr≣Cr quadruple bond.

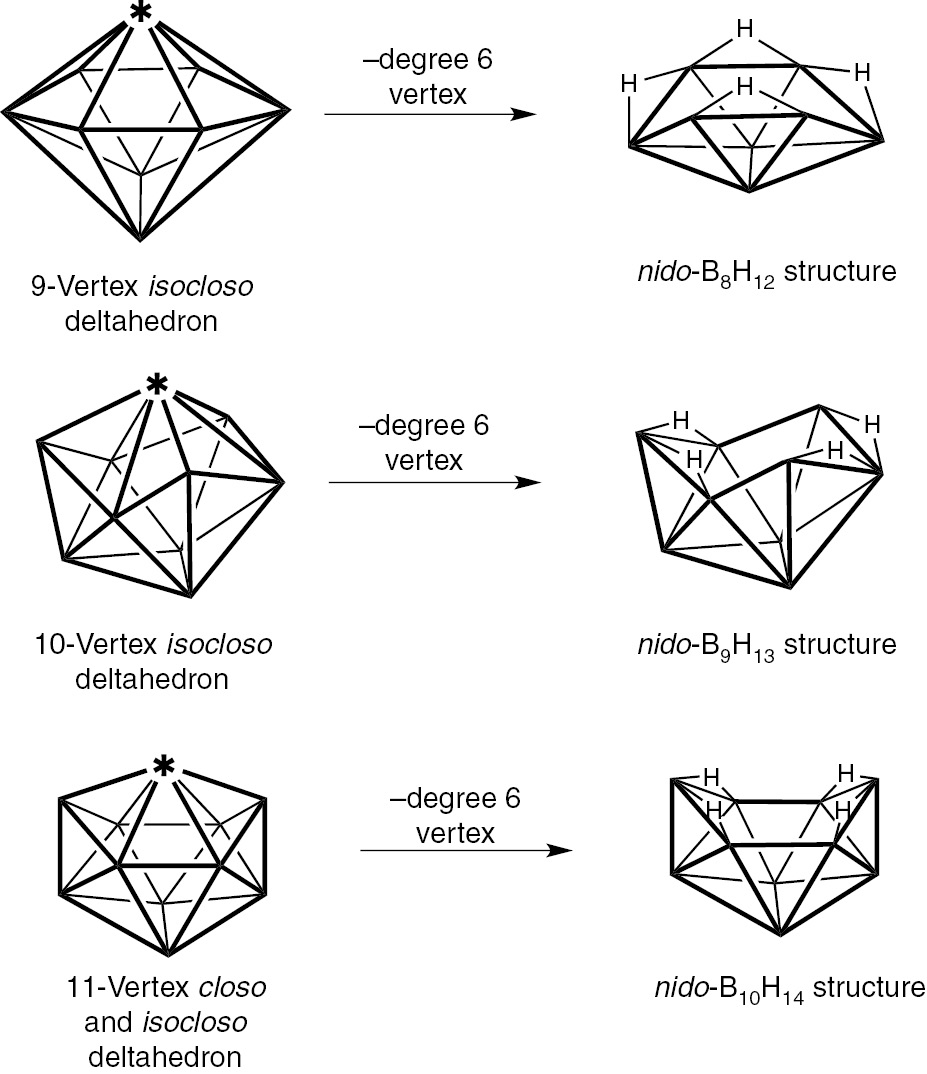

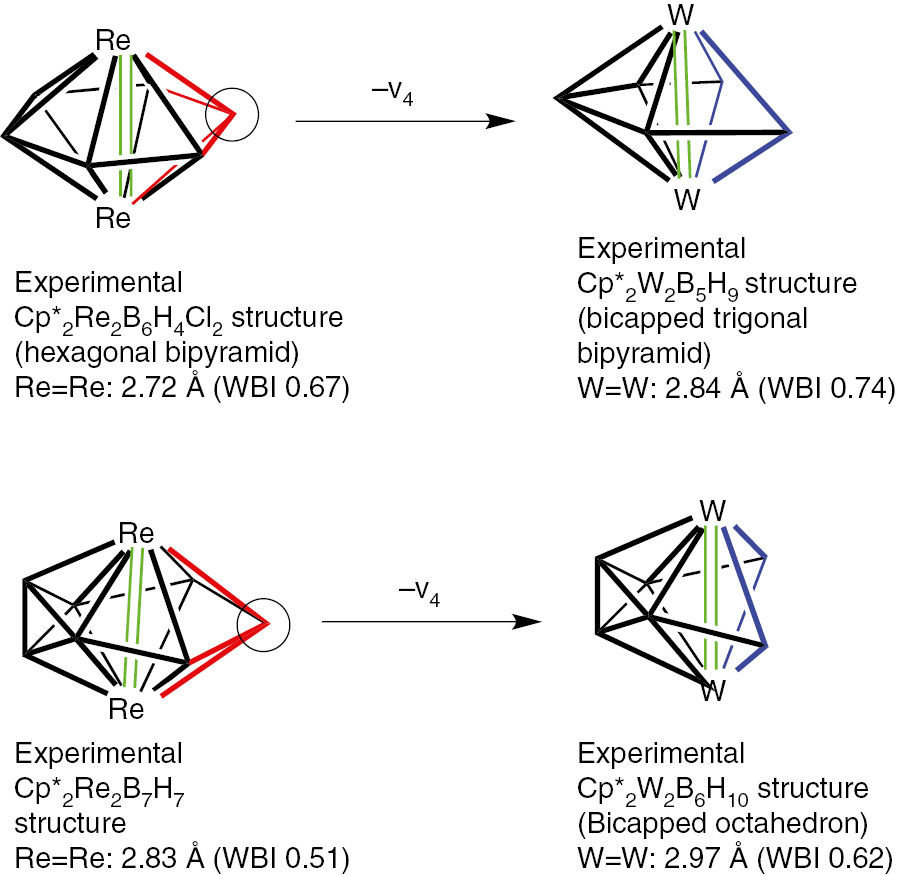

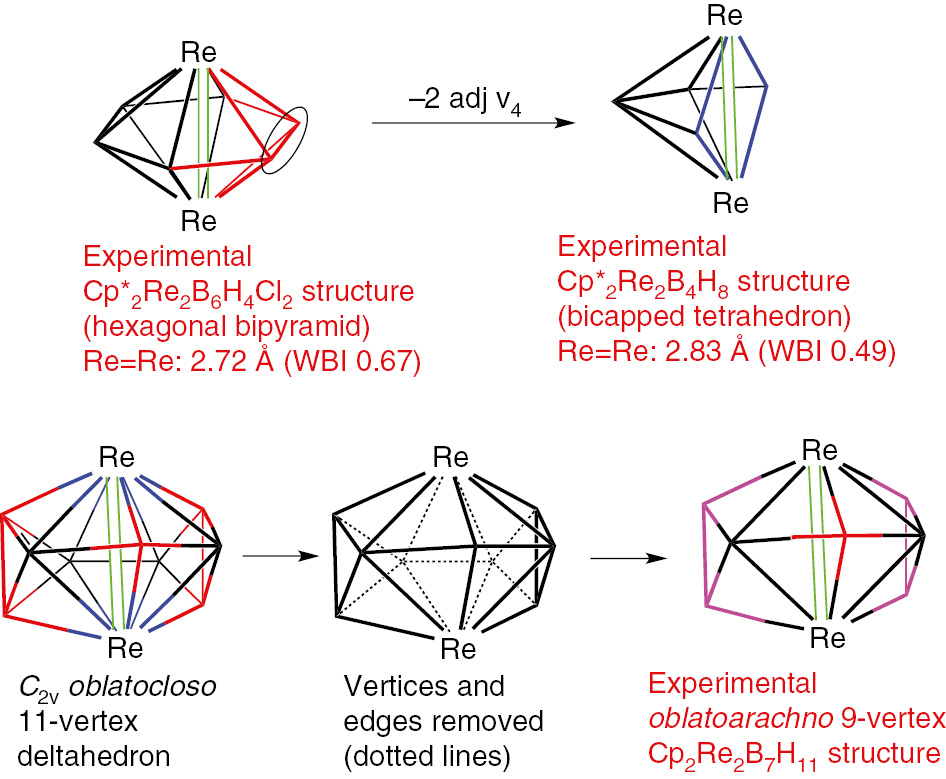

Removal of a high-degree vertex from a closo or isocloso deltahedron leads to a so-called nido structure with a pentagonal or hexagonal open face [3], [4]. The binary boranes of the type BnHn+4 (n=5, 6, 8, 9 10) exhibit such structures (Fig. 7). Removal of a boron vertex from an oblatocloso dirhenaborane deltahedron can lead analogously to an oblatonido dimetallaborane deltahedron. Such oblatonido deltahedra are found in ditungstaboranes of the general type Cp*2M2Bn−2Hn+2 (M=W; n=7, 8: Fig. 8) [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. The internal formal Re=Re double bond in the oblatocloso dirhenaborane structures Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 becomes an external W=W double bond in these ditungstaboranes. This W=W bond has been the subject of a topological study using diverse methods [43]. Removal of two adjacent boron vertices from the hexagonal bipyramidal oblatocloso Cp*2Re2B6H4Cl2 structure leads to the oblatoarachno structure Cp*2Re2B4H8 (Fig. 9) [44].

Generation of structures for the binary nido boranes BnHn+4 by vertex removal from closo and isocloso deltahedra.

Formation of the oblatonido ditungstaboranes Cp*2W2Bn−2Hn+2 (n=7, 8) structures by removal of a boron vertex from the oblatocloso dirhenaboranes Cp2Re2Bn2Hn−2.

Formation of the oblatoarachno dirhenaborane Cp*2Re2Bn−2Hn+2 (n=6, 9) structures by removal of two adjacent boron vertices from oblatocloso dirhenaboranes.

Trimetallaboranes

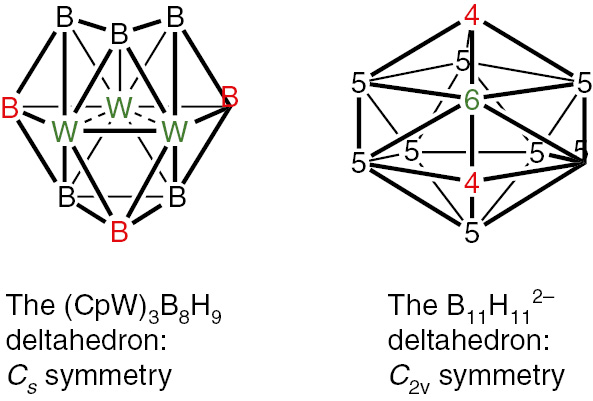

In 1998 Fehlner and co-workers [45] reported the synthesis of the unusual tritungstaborane Cp*3W3(μ-H)B8H8 by the pyrolysis of Cp*WB4H11. The central 11-vertex W3B8 deltahedron in Cp*3W3(μ-H)B8H8 deviates considerably from sphericity in having degree 6 and 7 vertices for the tungsten atoms and degree 4 and 5 vertices for the boron atoms (Fig. 10). This structure can be considered as a bonded W3 triangle imbedded into the 11-vertex W3B8 deltahedron. One of the W–W bonds in this W3 triangle lies on the deltahedral surface whereas the remaining two W–W bonds are located inside the deltahedron. This W3B8 deltahedron is very different from the most spherical 11-vertex closo deltahedron (Fig. 1). Much later the molybdenum analog Cp*3Mo3(H)B8H8 was synthesized by Ghosh and coworkers [46].

Comparison of the W3B8 deltahedron in Cp*3W3(μ-H)B8H8 with the most spherical 11-vertex closo deltahedron found in B11H112−.

A complication in the theoretical study of the Cp*3W3(μ-H)B8H8 and related Cp3W3Bn−3Hn−2 systems is the location of the “extra” hydrogen atom. Therefore we first studied the related trirhenaborane Cp3Re3B8H8 without the extra hydrogen atom [47]. The Cp3W3(μ-H)B8H8 and Cp3Re3B8H8 systems are isoelectronic (Table 2) since addition of the extra hydrogen atom as a deltahedral edge bridge brings an additional three electrons into the skeletal bonding. One of these three electrons is provided by the hydrogen atom. The remaining two electrons arise when an otherwise non-bonding metal lone pair is drawn into the skeletal bonding by the hydrogen bridge.

Comparison of the electron bookkeeping for the isoelectronic systems Cp3Re3B8H8 and Cp3W3(μH)B8H8

| Source of skeletal electrons for Cp3Re3B8H8: | |

| Three CpRe vertices with five internal orbitals: 3×4= | 12 electrons |

| Eight BH vertices: 8×2= | 16 electrons |

| Total skeletal electrons obtained: | 28 electrons |

| Use of skeletal electrons: | |

| Deltahedral surface bonding: 11×2= | 22 electrons |

| Bonded Re–Re triangle (three 2c–2e bonds): 3×2= | 6 electrons |

| Total skeletal electrons required: | 28 electrons |

| Source of skeletal electrons for Cp3W3B8H8(H): | |

| Three CpW vertices with five internal orbitals: 3×3= | 9 electrons |

| Bridging μ-H atom brings external W lone pair into the skeletal bonding scheme: | 3 electrons |

| Eight BH vertices: 8×2= | 16 electrons |

| Total skeletal electrons required: | 28 electrons |

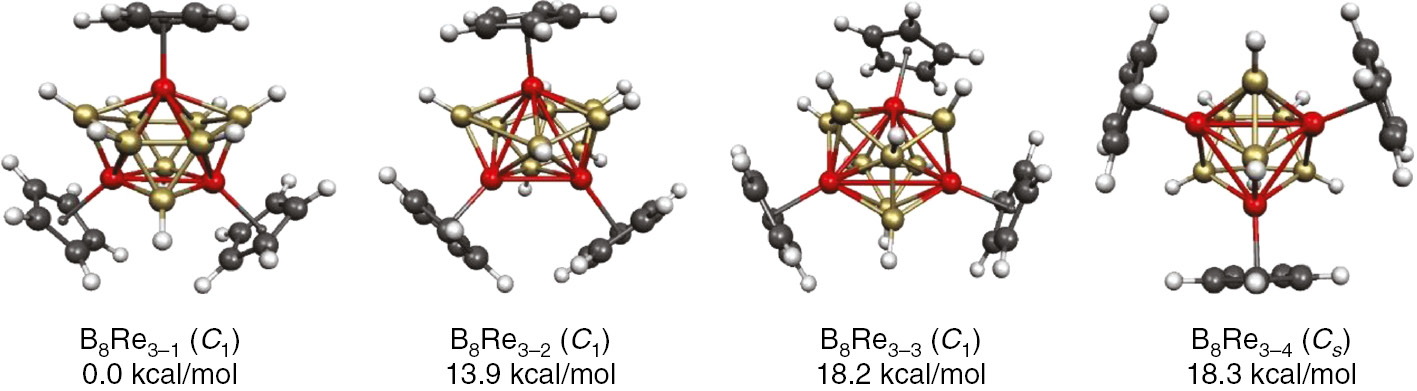

Figure 11 shows the four lowest-energy structures for the trirhenaborane Cp3Re3B8H8 [47]. The lowest energy structure is seen to have the same M3B8 deltahedron as the experimental Cp*3W3(μH)B8H8 deltahedron consistent with the isoelectronicity of the two structures. The lowest energy structures for the Cp3Re3Bn−3Hn−3 systems of other sizes (n=9, 10, 12) are shown in Fig. 12. These structures can all be considered to contain an Re3 triangle imbedded into an Re3Bn−3 deltahedron. The interior Re–Re bonds in these Re3 triangles range from 2.8 to 3.0 Å. The surface Re–Re bonds are significantly shorter at 2.6–2.7 Å because of their partial double bond character combining with the overall delocalized surface bonding of the deltahedron (Table 1).

The four lowest-energy Cp3Re3B8H8 structures.

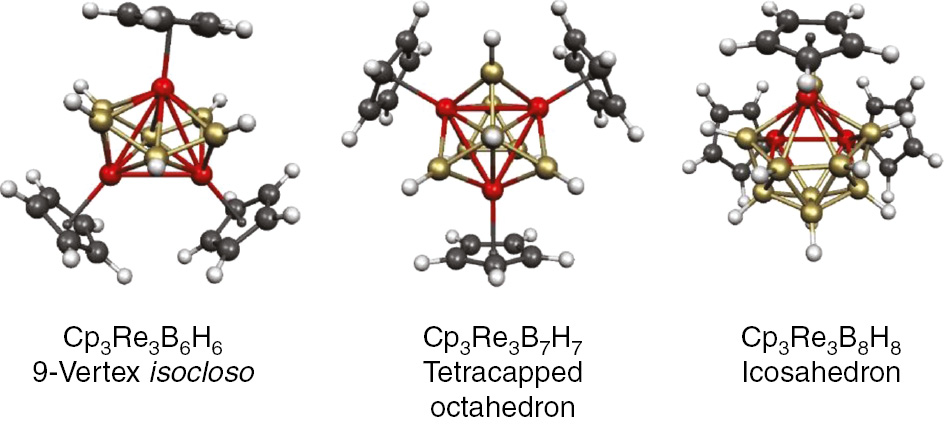

The lowest energy Cp3Re3Bn−3Hn−3 (n=9, 10, 12) structures.

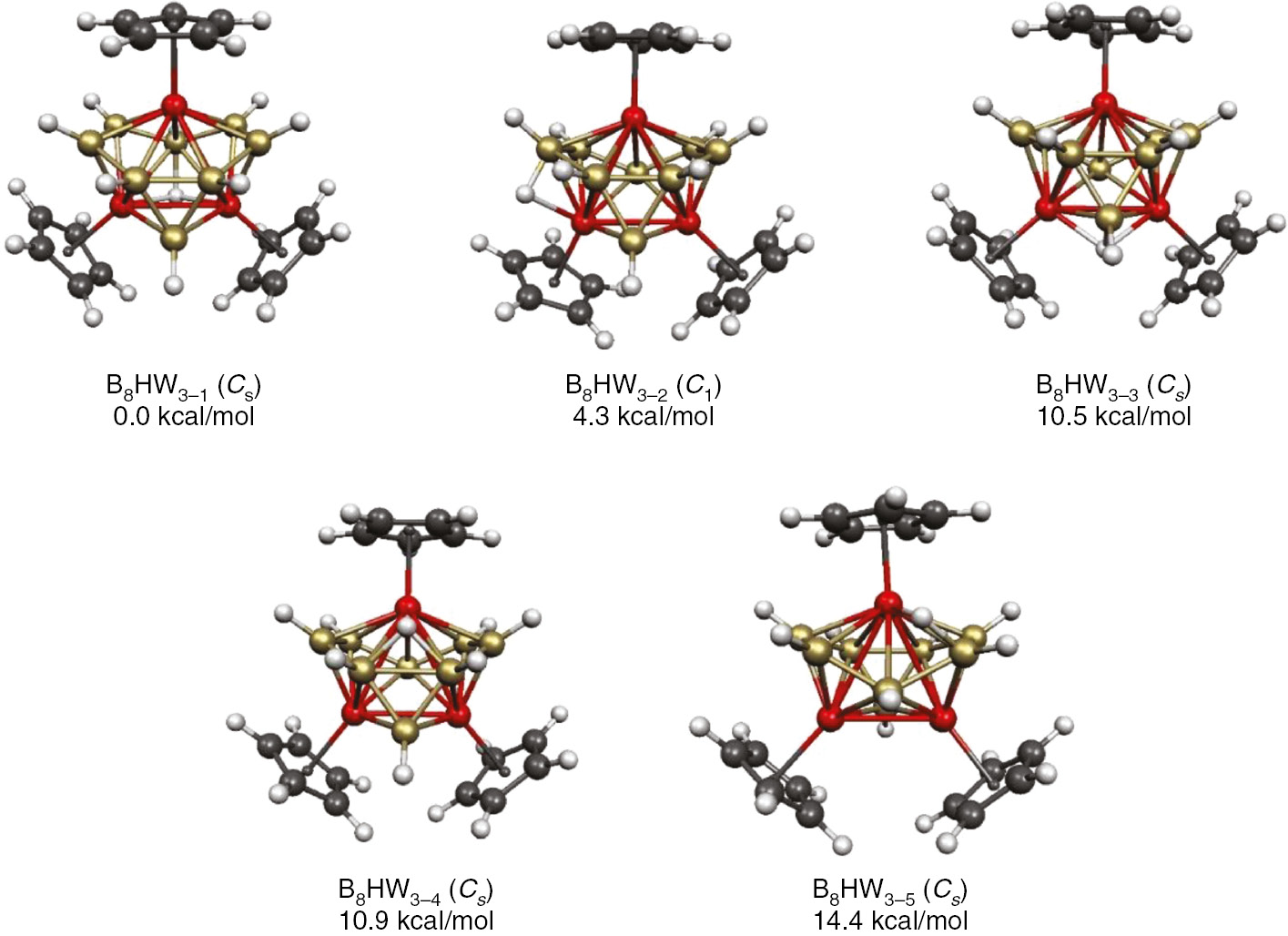

The lowest energy structures for the Cp3W3(μ-H)Bn−3Hn−3 (n=9–12) were determined using the same density functional theory methods [48]. All of the five lowest energy structures for the experimentally known 11-vertex Cp3W3(μH)B8H8 system were found to have the same 11-vertex central W3B8 deltahedron as the experimental Cp*3W3(μH)B8H8 structure (Fig. 13). They differ only in the location of the “extra” bridging hydrogen atom. The lengths of the interior W–W bonds were found to be ~3.0 Å, whereas those of the surface bonds were found to be significantly shorter at ~2.7 to ~2.8 Å. This is consistent with the observations on the Cp3Re3Bn−3Hn−3 systems as noted above.

The five lowest energy Cp3W3(H)B8H8 structures.

Conclusions

The lowest energy structures for the dirhenaboranes Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 correspond to the oblatocloso structures found experimentally by Fehlner, Ghosh, and their coworkers. Such structures have Re=Re distances ranging from 2.69 to 2.94 Å suggested by their skeletal bonding topology and Re=Re Wiberg bond indices to be formal double bonds. Higher energy structures for the dirhenaboranes Cp2Re2Bn−2Hn−2 have the same closo deltahedra as found in the corresponding BnHn2− anions. In these structures the rhenium atoms are located at adjacent vertices with ultrashort Re≣Re distances of 2.28–2.39 Å similar to the experimental Re≣Re distance of 2.24 Å for the formal quadruple bond in K2Re2Cl8. A formal Cr≣Cr quadruple bond of length 2.272 Å is found experimentally in the icosahedral Cp2Cr2C2B10H10 isoelectronic with Cp2Re2B10H10. Replacement of the Cp2Re2 unit with a PnRe2 (Pn=η5,η5-pentalene) unit forces the rhenium atoms to remain in adjacent positions so that the closo deltahedral structures with surface Re≣Re quadruple bonds become the lowest energy structures.

The lowest energy structures for the trimetallaboranes Cp3Re3Bn−3Hn−3 and Cp3W3(μ-H)Bn−3Hn−3 related to the experimentally known Cp3W3(μ-H)B8H8 have a central M3Bn−3 deltahedron typically containing a bonded M3 triangle. This central M3Bn3 deltahedron is not the most spherical closo deltahedron since the metal atoms prefer degree 6 and 7 vertices whereas the boron atoms prefer degree 4 and degree 5 vertices. The metal–metal bonds in the central M3 triangle are ~3.0 Å if they go through the center of the M3Bn−3 deltahedron but shorter at ~2.7 to ~2.8 Å if they lie on the surface of the M3Bn−3 deltahedron.

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON-16), Hong Kong, 9–13 July 2017.

Acknowledgments

Funding from the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research (Grant PN-II-RU-TE-2014-4-1197) is gratefully acknowledged. Computational resources were provided by the high-performance computational facility of the Babeș-Bolyai University (MADECIP, POSCCE, COD SMIS 48801/1862) co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union.

References

[1] K. P. Callahan, M. F. Hawthorne. Adv. Organometal. Chem. 14, 145 (1976).10.1016/S0065-3055(08)60651-6Suche in Google Scholar

[2] R. N. Grimes. Accts. Chem. Res. 16, 22 (1983).10.1021/ar00085a004Suche in Google Scholar

[3] R. E. Williams. Inorg. Chem. 10, 210 (1971).10.1021/ic50095a046Suche in Google Scholar

[4] R. E. Williams. Chem. Rev. 92, 177 (1992).10.1021/cr00010a001Suche in Google Scholar

[5] R. B. King, A. J. W. Duijvestijn. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 178, 55 (1990).10.1016/S0020-1693(00)88133-5Suche in Google Scholar

[6] K. Wade. Chem. Commun. 792 (1971).10.1039/c29710000792Suche in Google Scholar

[7] D. M. P. Mingos. Nat. Phys. Sci. 99, 236 (1972).10.1038/physci236099a0Suche in Google Scholar

[8] D. M. P. Mingos. Accts. Chem. Res. 17, 311 (1984).10.1021/ar00105a003Suche in Google Scholar

[9] J. D. Kennedy. Inorg. Chem. 25, 111 (1986).10.1021/ic00221a030Suche in Google Scholar

[10] J. Bould, J. D. Kennedy, M. Thornton-Pett. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton. 563 (1992).10.1039/DT9920000563Suche in Google Scholar

[11] J. D. Kennedy, B. Štíbr. “Polyhedral metallaborane and metallaheteroborane chemistry. Aspects of cluster flexibility and fluxionality”, in Current Topics in the Chemistry of Boron, G. W. Kabalka (Ed.), pp. 285–292, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge (1994).10.1002/chin.199504296Suche in Google Scholar

[12] J. D. Kennedy. Disobedient skeletons, in The Borane-Carborane-Carbocation Continuum, Casanova, J. (Ed.), ch. 3, pp. 85–116, Wiley, New York (1998).Suche in Google Scholar

[13] B. Štíbr, J. D. Kennedy, E. Drdáková, M. Thornton-Pett. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton. 229 (1994).10.1039/DT9940000229Suche in Google Scholar

[14] S. H. Vosko, L. Wilk, M. Nusair. Can. J. Phys. 58, 1200 (1980).10.1139/p80-159Suche in Google Scholar

[15] A. D. Becke. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648 (1993).10.1063/1.464913Suche in Google Scholar

[16] P. J. Stephens, F. J. Devlin, C. F. Chabalowski, M. J. Frisch. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11623 (1994).10.1021/j100096a001Suche in Google Scholar

[17] C. Lee, W. Yang, R. G. Parr. Phys. Rev. 37B, 785 (1998).10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785Suche in Google Scholar

[18] D. G. Truhlar, Y. Zhao. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215 (2008).Suche in Google Scholar

[19] C. Riplinger, B. Sandhoefer, A. Hansen, F. Neese. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 134101 (2013).10.1063/1.4821834Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] J. W. Evans, C. J. Jones, B. Štibr, R. A. Grey, M. F. Hawthorne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96, 7405 (1974).10.1021/ja00831a006Suche in Google Scholar

[21] K. P. Callahan, W. J. Evans, F. Y. Lo, C. E. Strouse, M. F. Hawthorne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97, 296 (1975).Suche in Google Scholar

[22] For a review of much of the relevant chemistry from Fehlner’s group see T. P. Fehlner. “Metallaboranes of the earlier transition metals: relevance to the cluster electron counting rules” in Group 13 Chemistry: From Fundamentals to Applications, P. J. Shapiro, D. A. Atwood (Eds.), pp. 49–67, American Chemical Society, Washington, DC (2002).10.1021/bk-2002-0822.ch004Suche in Google Scholar

[23] S. Ghosh, M. Shang, Y. Li, T. P. Fehlner. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 1125 (2001).10.1002/1521-3773(20010316)40:6<1125::AID-ANIE11250>3.0.CO;2-PSuche in Google Scholar

[24] H. Wadepohl. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 4220 (2002).10.1002/1521-3773(20021115)41:22<4220::AID-ANIE4220>3.0.CO;2-XSuche in Google Scholar

[25] B. Le Guennic, H. Jiao, S. Kahlal, J.-Y. Saillard, J.-F. Halet, S. Ghosh, M. Shang, A. M. Beatty, A. L. Rheingold, T. P. Fehlner. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 3203 (2004).10.1021/ja039770bSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] R. B. King. Inorg. Chem. 45, 6211 (2006).10.1021/ic060922oSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] A. Lupan, R. B. King. Inorg. Chem. 51, 7609 (2012).10.1021/ic300458wSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] B. S. Krishnamoorthy, S. Kahlal, B. Le Guennick. J.-Y. Saillard, S. Ghosh, J.-F. Halet. Solid State Sci.14, 1617 (2012).10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2012.03.026Suche in Google Scholar

[29] A. Lupan, R. B. King. Organometallics32, 4002 (2013).10.1021/om400481cSuche in Google Scholar

[30] F. A. Cotton, C. B. Harris. Inorg. Chem. 4, 330 (1965).10.1021/ic50025a014Suche in Google Scholar

[31] J.-I. Aihara. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 3339 (1978).10.1021/ja00479a015Suche in Google Scholar

[32] R. B. King. D. H. Rouvray. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 7834 (1977).10.1021/ja00466a014Suche in Google Scholar

[33] R. B. King, Chem. Rev. 101, 1119 (2001).10.1021/cr000442tSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] R. B. King. Inorg. Chem. 38, 5151 (1999).10.1021/ic990601vSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] G. K. Barker, N. R. Godfrey, M. Green, H. E. Parge, F. G. A. Stone, A. J. Welch. Chem. Commun. 277 (1983).Suche in Google Scholar

[36] F. A. Cotton, G. E. Rice, G. W. Rice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 4704 (1977).10.1021/ja00456a029Suche in Google Scholar

[37] J. Ho, K. J. Deck, Y. Nishihara, M. Shang, T. P. Fehlner. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 10292 (1995).Suche in Google Scholar

[38] T. P. Fehlner. J. Organomet. Chem. 550, 21 (1998).10.1016/S0022-328X(97)00174-5Suche in Google Scholar

[39] S. Aldridge, H. Hashimoto, K. Kawamura, M. Shang, T. P. Fehlner. Inorg. Chem. 37, 928 (1998).Suche in Google Scholar

[40] S. Aldridge, M. Shang, T. P. Fehlner. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 2586 (1998).10.1021/ja973720nSuche in Google Scholar

[41] A. S. Weller, M. Shang, T. P. Fehlner. Organometallics18, 53 (1999).Suche in Google Scholar

[42] S. K. Bose, S. Ghosh, B. C. Noll, J.-F. Halet, U.-Y. Saillard, A. Vega. Organometallics26, 5377 (2007).Suche in Google Scholar

[43] B. Boucher, J.-F. Halet, M. Kohout. Comput. Theor. Chem.1068, 134 (2015).10.1016/j.comptc.2015.06.029Suche in Google Scholar

[44] S. Ghosh, M. Shang, T. P. Fehlner. J. Organomet. Chem. 614, 92 (2000).Suche in Google Scholar

[45] A. S. Weller, M. Shang, T. P. Fehlner. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 8283 (1998).10.1021/ja980353mSuche in Google Scholar

[46] K. Kumar, V. Chakrahari, A. Thakur, B. Mondal, R. S. Dhayal, V. Ramakumar, S. Ghosh. J. Organomet. Chem. 710, 75 (2012).10.1016/j.jorganchem.2012.02.027Suche in Google Scholar

[47] A. A. A. Attia, A. Lupan, R. B. King. New J. Chem. 40, 7564 (2016).10.1039/C6NJ01922FSuche in Google Scholar

[48] A. A. A. Attia, A. Lupan, R. B. King. New J. Chem. 41, 10640 (2017).10.1039/C7NJ01801KSuche in Google Scholar

©2018 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON XVI)

- Conference papers

- Palladium-promoted sulfur atom migration on carboranes: facile B(4)−S bond formation from mononuclear Pd-B(4) complexes

- When diazo compounds meet with organoboron compounds

- Transition-metal complexes with oxidoborates. Synthesis and XRD characterization of [(H3NCH2CH2NH2)Zn{κ3O,O′,O′′-B12O18(OH)6-κ1O′′′}Zn(en)(NH2CH2CH2NH3)]·8H2O (en=1,2-diaminoethane): a neutral bimetallic zwiterionic polyborate system containing the ‘isolated’ dodecaborate(6−) anion

- Novel sulfur containing derivatives of carboranes and metallacarboranes

- Metal–metal bonding in deltahedral dimetallaboranes and trimetallaboranes: a density functional theory study

- Nanostructured boron compounds for cancer therapy

- Heterometallic boride clusters: synthesis and characterization of butterfly and square pyramidal boride clusters*

- Influence of fluorine substituents on the properties of phenylboronic compounds

- Copper-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative borylation: new pathway to optically active heterocyclic compounds

- Borenium and boronium ions of 5,6-dihydro-dibenzo[c,e][1,2]azaborinine and the reaction with non-nucleophilic base: trapping of a dimer and a trimer of BN-phenanthryne by 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine

- The electrophilic aromatic substitution approach to C–H silylation and C–H borylation

- Recent advances in B–H functionalization of icosahedral carboranes and boranes by transition metal catalysis

- closo-Dodecaborate-conjugated human serum albumins: preparation and in vivo selective boron delivery to tumor

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Risk assessment of effects of cadmium on human health (IUPAC Technical Report)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- 16th International Meeting on Boron Chemistry (IMEBORON XVI)

- Conference papers

- Palladium-promoted sulfur atom migration on carboranes: facile B(4)−S bond formation from mononuclear Pd-B(4) complexes

- When diazo compounds meet with organoboron compounds

- Transition-metal complexes with oxidoborates. Synthesis and XRD characterization of [(H3NCH2CH2NH2)Zn{κ3O,O′,O′′-B12O18(OH)6-κ1O′′′}Zn(en)(NH2CH2CH2NH3)]·8H2O (en=1,2-diaminoethane): a neutral bimetallic zwiterionic polyborate system containing the ‘isolated’ dodecaborate(6−) anion

- Novel sulfur containing derivatives of carboranes and metallacarboranes

- Metal–metal bonding in deltahedral dimetallaboranes and trimetallaboranes: a density functional theory study

- Nanostructured boron compounds for cancer therapy

- Heterometallic boride clusters: synthesis and characterization of butterfly and square pyramidal boride clusters*

- Influence of fluorine substituents on the properties of phenylboronic compounds

- Copper-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative borylation: new pathway to optically active heterocyclic compounds

- Borenium and boronium ions of 5,6-dihydro-dibenzo[c,e][1,2]azaborinine and the reaction with non-nucleophilic base: trapping of a dimer and a trimer of BN-phenanthryne by 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine

- The electrophilic aromatic substitution approach to C–H silylation and C–H borylation

- Recent advances in B–H functionalization of icosahedral carboranes and boranes by transition metal catalysis

- closo-Dodecaborate-conjugated human serum albumins: preparation and in vivo selective boron delivery to tumor

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Risk assessment of effects of cadmium on human health (IUPAC Technical Report)