Abstract

Objectives

While immunotherapy has improved survival outcomes in melanoma patients, effective biomarkers for predicting treatment responses and prognosis are still lacking. DNA base excision repair (BER) is closely linked to anti-tumor immunity, but the relationship between BER activity in melanoma and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) remains unclear. This study aims to analyze the association between BER activity in melanoma and T cells abundance.

Methods

In this study, a melanoma dataset from immune checkpoint blockers (ICBs) therapy was used to validate the relationship between TILs and immunotherapy response. Then, a single-cell sequencing dataset was used to investigate the association between melanoma with distinct biological characteristics and immune cell infiltration. Finally, immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses were performed to assess the correlation between the expression of Apurinic/apyrimidinic Endonuclease (APE1), a key enzyme in the BER pathway, and CD4+ T cell infiltration.

Results

A higher infiltration of CD4+ T cells was associated with better response and prognosis of ICBs treatment in melanoma (mPFS: 7.23 vs. 2.77 months, p<0.001; mOS: 32.3 vs. 10.1 months, n=121, p=0.012). Melanoma cells can be classified into four subtypes, and the BER subtype showed a significant positive correlation with CD4+ T cell infiltration (Pearson’s r=0.584, p=0.046). In the IHC assay, APE1 expression was positively correlated with CD4+ T cell abundance (Pearson’s r=0.58, n=89, p<0.001).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that BER activity is positively associated with CD4+ T cell infiltration, and APE1 expression may serve as a potential biomarker for evaluating melanoma treatment response and prognosis.

Introduction

Melanoma represents the most aggressive subtype of skin cancer. In recent years, the incidence and mortality rates of melanoma have been steadily increasing [1]. Compared to other solid tumors, melanoma results in fatalities at a younger age. Melanoma has become a significant threat to human health with limited treatment options. While early-stage melanoma (Stage I-II) can be effectively treated through surgical resection, with a 5-year survival rate as high as 99.4 % [2], prognosis worsens significantly in advanced stages: stage III melanoma has a reduced 5-year survival rate of 68 %, and stage IV drops to only 29.8 % [3].

A body of evidence has demonstrated that the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a central role in cancer progression and treatment. Specifically, lymphocytes are essential effectors in anti-tumor immunity. The presence of Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is strongly associated with a favorable prognosis in melanoma [4], 5]. On the other hand, melanoma exhibits higher genomic instability and tumor mutational burden (TMB) compared to other cancer types. With the development of immune checkpoint blockers (ICBs) such as anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents, immunotherapy has demonstrated remarkable clinical efficacy in a subset of advanced melanoma patients [6]. However, despite favorable responses in some patients, the overall response rate to immunotherapy remains only 34 % in advanced melanoma [7], highlighting the urgent need to develop biomarkers to identify patients who can benefit from ICBs. As a highly immunogenic tumor, the immune microenvironment of melanoma profoundly influences patient prognosis. For instance, the abundance of neoantigen-specific CD4+ T cells has been shown to correlate with B-cell differentiation status and patient survival [8], underscoring the pivotal role of CD4+ T cells in melanoma treatment [9], 10]. Thus, identifying novel biomarkers for immunotherapy is crucial to optimizing clinical outcomes.

Genome instability is one of the hallmarks of tumors [11]. DNA damage, the initiation of genome instability, is closely linked to the activation of anti-tumor immunity. For example, unrepaired DNA damage may generate neoantigens [12], and DNA fragments can activate the cGAS-STING pathway to modulate anti-tumor immune responses [13]. Base excision repair (BER) is the primary pathway for repairing endogenous DNA base damage [14], and Apurinic/apyrimidinic Endonuclease 1 (APE1) is a key rate-limiting enzyme in BER. Previous studies have shown that APE1 overexpression correlates with poor progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and therapy resistance in multiple cancers [15]. Notably, extensive studies have demonstrated that APE1 is overexpressed in various tumor tissues, and its expression correlates with tumor malignancy, metastatic potential, and patient prognosis [16], positioning it as a promising therapeutic target [17]. Concurrently, APE1 plays multifaceted roles in immune responses, including ROS regulation and cytokine expression in innate immune cells, as well as modulation of B cell activation and class-switch recombination (CSR) in adaptive immunity [18]. Its effects on immune cells (e.g., T cells, B cells, and macrophages) have been extensively documented [19], 20]. Wang et al. reported that elevated APE1 expression in bladder cancer correlated with high VEGFA expression and increased infiltration of CD163+ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), suggesting that the crosstalk between APE1 and CD163+ TAMs may worsen prognosis and reduce survival [21]. Additionally, Qing et al. observed that PD-L1 and APE1 were positively expressed in 50.5 and 86.9 % of gastric cancer tissues, respectively, with co-expression in 49.5 % of cases associated with enhanced invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis [22].

We previously found that CD4+ naïve T-cell infiltration was associated with improved prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), while a negative correlation between APE1 expression and CD4+ naïve T-cell infiltration was observed [23]. However, the relationship between APE1 and CD4+ T-cell infiltration in melanoma remains unclear.

This study investigates the correlation between BER status, immune cell infiltration, and prognosis in melanoma. We further validate the association between APE1 expression and CD4+ T cell infiltration in clinical melanoma samples, aiming to provide insights for treatment and prognostic evaluation in melanoma.

Materials and Methods

scRNA-seq data analysis

Raw count matrix of GSE222446 was downloaded from GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds) [24]. The Seurat object was constructed by combining the read count matrix of each patient using the R package ‘Seurat’ (version 5.2.1) [25]. Only genes expressed in at least 1 % of cells were retained for subsequent analysis. Each patient was considered as a batch effect. Normalization was performed via natural-log transformation with a scale factor of 10,000. Genes with the highest variance (n=2,000) were used to calculate principal components (PCs). Harmony integration was applied to obtain the PC reduction space corrected for batch effects. The original Seurat clusters were generated at a resolution of 0.2 using the first 20 batch-corrected PCs. The melanoma signature [26] and ‘AUCell’ analysis (version 1.20.2) [27] were used to assist in identifying the melanoma population. ‘scType’ (Code copyright 2021) [28] was employed to identify cell types using canonical cell type markers from the CellSTAR database (https://cellstar.idrblab.net/) [29].

To further identify melanoma subclusters, a total of 53,112 melanoma cells were initially clustered into 6 subclusters. Hallmark gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) [30] were used to characterize each subcluster with AUCell analysis. Finally, four melanoma subtypes were identified based on the average AUCell scores in the original subclusters. A total of 16,551 T cells were further integrated into 11 original subclusters at a resolution of 0.6 using the first 20 PCs, and eight subpopulations were finally identified, employing an approach similar to that used for major cluster identification.

Measurement for the relative abundance of melanoma cell subtypes

To elucidate the association between specific melanoma cell subtypes and tumor immune microenvironment features in bulk RNA-seq samples with comprehensive clinical annotation, an algorithm was developed to measure the relative abundance of a given melanoma subtype among all melanoma cells, leveraging scRNA-seq data. The FindAllMarkers function in the ‘Seurat’ package was used to identify marker genes for each of the four melanoma subtypes against all other major cell types and the other melanoma subtypes. Any marker genes overlapping with the melanoma signature from the article were removed [26]. The top 20 marker genes with the highest significance were selected for each melanoma subtype. The relative abundance of each melanoma subtype was calculated as the ratio of the average expression value of the marker genes for that subtype to the average expression value of the melanoma signature from the article [26].

TCGA SKCM cohort and establishment of immune subtypes

Clinical and survival data, along with the bulk RNA-seq Transcripts Per Million (TPM) matrix from The Cancer Genome Atlas Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (TCGA SKCM), were downloaded from UCSC (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages). The log2 (TPM) format was used to infer immune cell abundance using MCPcounter (version 1.2.0), as well as the relative abundance of melanoma cell subtypes. Immune subtyping of the TCGA SKCM cohort was conducted based on the abundance of 10 types of immune cells inferred from MCPcounter, which was normalized through z-transformation across samples. Three immune subtypes were identified using the ExecuteCC function in the R package ‘CancerSubtypes’ (version 1.17.1), with parameters clusterAlg=“km” and distance=“euclidean”. In order to evaluate the reproducibility of the immune subtypes, two other independent melanoma cohorts were used. GSE65904 consisted of 214 melanoma tumor biopsies profiled with Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 expression beadchip. GSE190113 was the bulk RNA-seq dataset that included 105 melanoma samples. The expression matrix corrected for batch effect with ComBat of GSE190113, and the normalized expression matrix of GSE65904 obtained through the R package limma (version 3.54.1) were applied to the MCP counter to perform immune subtyping with the same method as TCGA SKCM. Twenty-three canonical pathways from the article were used as a gene set applied to gene set variation analysis (GSVA) [31]. The average value of the normalized transformation of enrichment score within each immune subtype was visualized with a heatmap.

Two gene sets, the GOBP BER pathway and the KEGG BER pathway from MSigDB c5 and c2 gene sets, respectively, were applied to GSVA (version 1.48.3). The abundance of 18 kinds of immune scores was obtained with function consensus TMEA analysis setting parameter cancer=“SKCM”, StatMethod=“ssgsea” by using the R package consensus TME (version 0.0.1.9000). Tumor purity, established by four independent methods for TCGA SKCM, was obtained from the article [32], and the median value of the four tumor purity values was used for correlation analysis.

Massachusetts General Hospital skin pathology (MGSP) cohort analysis

The clinical data and tumor tissue bulk RNA-seq TPM matrix of the melanoma cohort that underwent immunotherapy were obtained from the supplementary materials accompanying the published article [33]. The calculation for the relative abundance of melanoma subtypes and the abundance of 18 types of immune cells followed the same methodology as used for the TCGA SKCM cohort. The immune score and the abundance of CD4+ T cells referred from consensus TME were used to categorize patients into low and high groups based on the 25 % percentile value, respectively. The immune score deduced by consensus TME is the measurement for total immune infiltration in any given tumor tissue sample.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

The tissue microarray comprising 89 melanoma samples and their clinical data was retrieved from Shanghai Outdo Biotech Company in accordance with relevant regulations. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Antibodies used in the IHC assay: Anti-CD4: Clone EPR6855 (Epitomics/Abcam, Cambridge, UK), diluted at 1:100. Anti-CD8: Clone C8/144B (Dako/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), diluted at 1:100. Slides were scanned using a Leica SCN400 slide scanner (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) and visualized with Digital Image Hub software (v2.1). Quantitative image analyses of CD4 and CD8 were performed using the “Measure Stained Cells Algorithm” (Leica Biosystems), with parameters optimized for chromogen-specific staining intensity, nuclear counterstaining thresholds, and cellular morphology. CD4:>10 % (high), 5–10 % (moderate), <5 % (low); CD8:>20 % (high), 10–20 % (moderate), <10 % (low). The average value from up to four fields of view per patient was calculated to represent overall marker expression. The expression of APE1 was scored on a semi-quantitative scale (0, 1, 2, 3), with each sample evaluated by three experienced pathologists.

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Army Medical Center of PLA (2022 number 51).

Statistical analysis

The association between the relative abundance of melanoma subtypes and the abundance of immune cells was determined by univariate and multivariate linear regression in the TCGA SKCM cohort by using the relative abundance of each of four melanoma cell types as an independent variable and enrichment score from consensus TME as a dependent variable. The clinical factors that were adjusted for in the multivariate linear regression included T stage (T3 vs. T0-1; T4 vs. T0-2), N stage (N1-3 vs. N0), and tumor biopsy sites (lymph node vs. others), which may impact the composition of the TME. The regression coefficients of the melanoma subtypes or correlation coefficients were visualized with a heatmap without any transformation. Correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman correlation coefficient with the R package ‘corrplot’ (version 0.92). Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the percentage of CD4 and CD8 positive staining or the ordinary variables of categorized CD4 and CD8 staining density among APE1 groups with correction for multiple comparisons. Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test were used to evaluate the difference in survival rates between groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression were used to identify independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS. All analyses were performed with R version 4.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

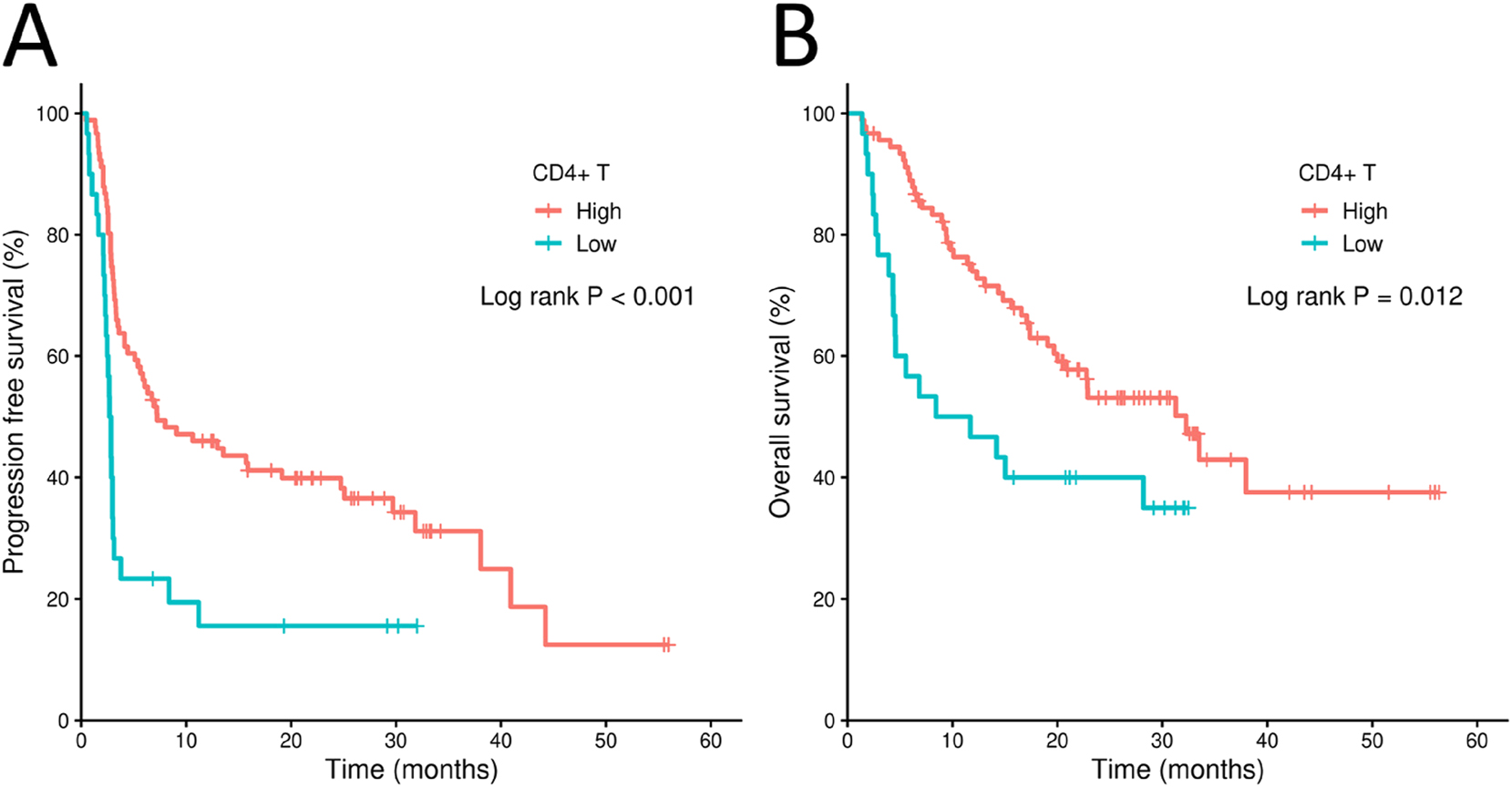

CD4+ T cell abundance correlates with optimal PFS and OS in melanoma patients receiving immunotherapy

To assess the impact of CD4+ T cells in melanoma, the MGSP dataset, comprising 121 melanoma samples from patients actually treated with PD-1 inhibitors, was analyzed [23]. The clinical characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 At the cutoff value of 25 % percentile value for CD4+ T cells, Kaplan-Meier plots showed that the PFS and OS of patients with high CD4+ T cell infiltration were significantly better than those with low CD4+ T cell infiltration (log-rank p<0.001, p=0.012, respectively) (Figure 1A and B). Univariate Cox regression showed that patients with high immune score or with high infiltration of CD4+ T cells have significantly decreased progression risk compared with patients with low immune score or low infiltration of CD4+ T cells (Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, the abundance of CD4+ T cells remained significant in multivariate Cox regression after being adjusted for gender, ECOG, stage, biopsy site, ICB drugs, ICB therapy line, BOR, and immune score (Supplementary Table S2). However, although high infiltration of CD4+ T cells was significantly associated with lower death risk in the univariate Cox regression, this association had borderline significance in the multivariate Cox regression (Supplementary Table S2). These results indicate that CD4+ T cell infiltration may independently influence the long-term benefit from ICB treatment in melanoma patients [23].

Kaplan-Meier plots for melanoma patient groups from the MGSP cohort. (A) Poor progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with high or low CD4+ T cell infiltration in the MGSP cohort. (B) Overall survival (OS) of patients with high or low CD4+ T cell infiltration in the MGSP cohort. The high and low CD4+ T cell infiltration groups were determined by the 25 % percentile value of the enrichment score of CD4+ T cells from consensus TME in the MSGP cohort.

BER-active melanoma subtype positively correlates with CD4+ T cell infiltration

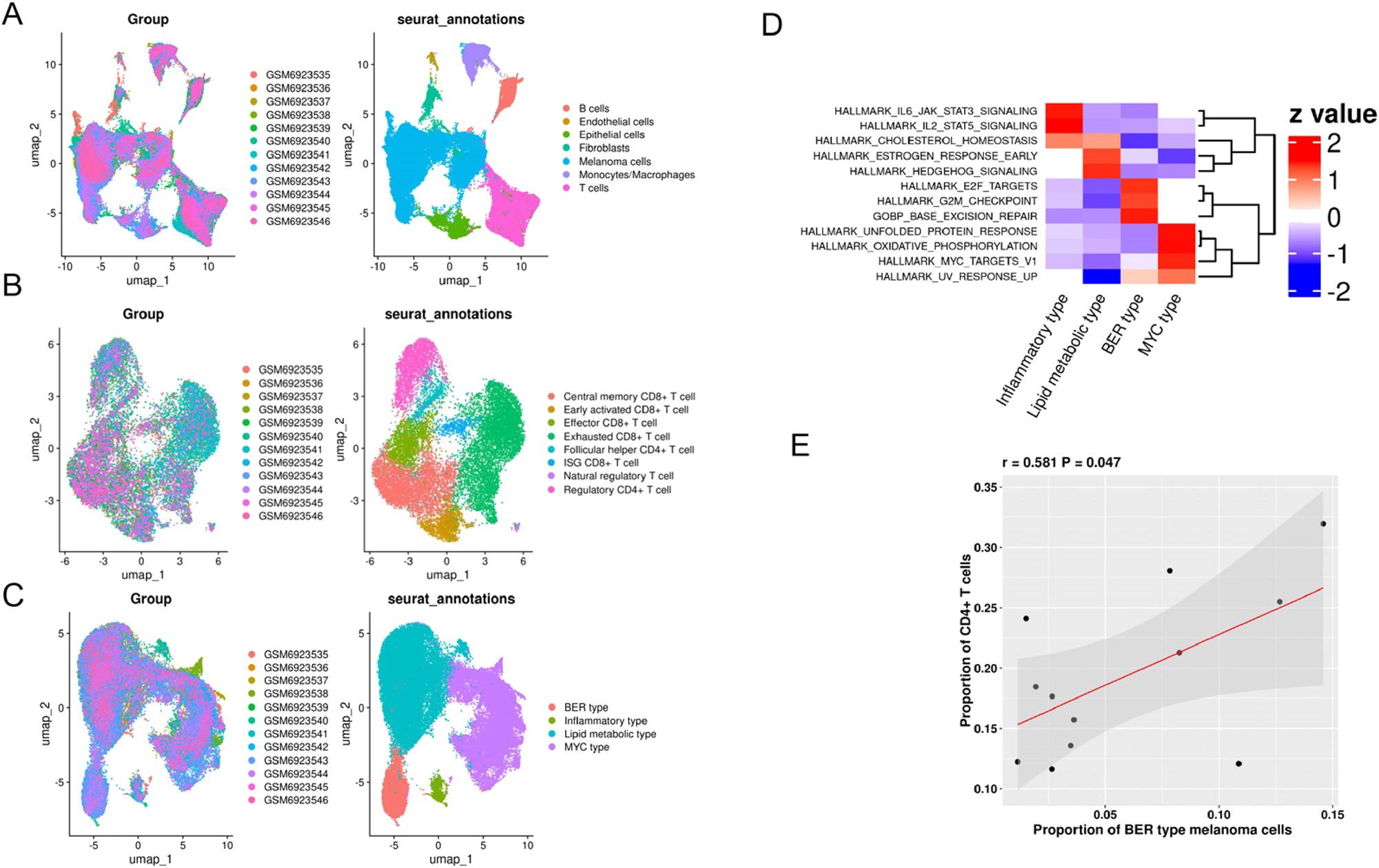

Melanoma exhibits marked heterogeneity across molecular subtypes, each displaying diverse clinical behaviors and responses to ICBs. To dissect subtype-specific immune interactions and evaluate the impact of DNA damage repair in immune response, we analyzed a single-cell RNA-seq dataset (GSE222446), which included 13 melanoma samples. Using ‘Seurat’ clustering corrected for batch effect, seven major cell populations were identified: melanoma cells, B cells, endothelial cells, epithelioid cells, fibroblasts, monocytes/macrophages, and T cells (Figure 2A). Focusing on T cells, only two CD4+ T cell subpopulations, including regulatory T cells and follicular helper CD4+ T cells, were identified. Then six CD8+ T cell subpopulations were characterized (Figure 2B). Melanoma cells were stratified into four molecular subtypes: BER type, inflammation type, lipid metabolism type, and myelocytomatosis oncogene (MYC) type (Figure 2C). As shown in Figure 2D, distinct biological features were identified in terms of the activity of canonical pathways specific to each subtype. For example, the BER type melanoma is active in DNA damage and repair pathways, including E2F targets, the G2M checkpoint, and the BER pathways. The cell number for each cell type was shown in Supplementary Table S3. The marker genes for these four subtypes of melanoma cells are shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Identification of major cell types and subpopulations of melanoma cells and T cells in the GSE222446 dataset. (A) UMAP view of seven major cell types. (B) UMAP of eight T cell subsets. (C) UMAP of four melanoma subtypes. (D) heatmap representative of different biological characteristics of four melanoma subtypes. (E) scatter plot showing positive correlation of the proportion of CD4+T cells and BER type melanoma.

Correlationship analysis demonstrated a positive association between proportion of CD4+ T cells within all T cells and the proportion of BER type melanoma (p=0.047, Figure 2E), but no significant association was observed between proportion of CD4+ T cells and the proportion of inflammation type, lipid metabolism type, or MYC type melanoma cells (Supplementary Figure S1A–C). These findings suggest that the BER pathway in highly activated melanoma cells may promote CD4+ T cell infiltration, potentially serving as biomarkers for prognosis and therapeutic response prediction.

Validating the relationship between BER-active melanoma and CD4+ T cell infiltration in TCGA SKCM

To further confirm the findings regarding the positive correlation between CD4+ T cell infiltration and the BER pathway, as well as patient prognosis, melanoma samples from the TCGA database were utilized. The clinical characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table S5. Firstly, we conduct a correlation analysis in order to verify the feasibility of the method to evaluate the relative abundance of each melanoma subtype in bulk RNA-seq data. The results showed that BER activity and APE1 expression were positively correlated with tumor purity but negatively correlated with immune score, indicating that BER pathway activity and APE1 expression may be affected by tumor purity in bulk RNA-seq data. In contrast, the four subtypes were not correlated with tumor purity, indicating that the measurement of the relative abundance of each melanoma subtype was less affected by tumor purity (Supplementary Figure S2).

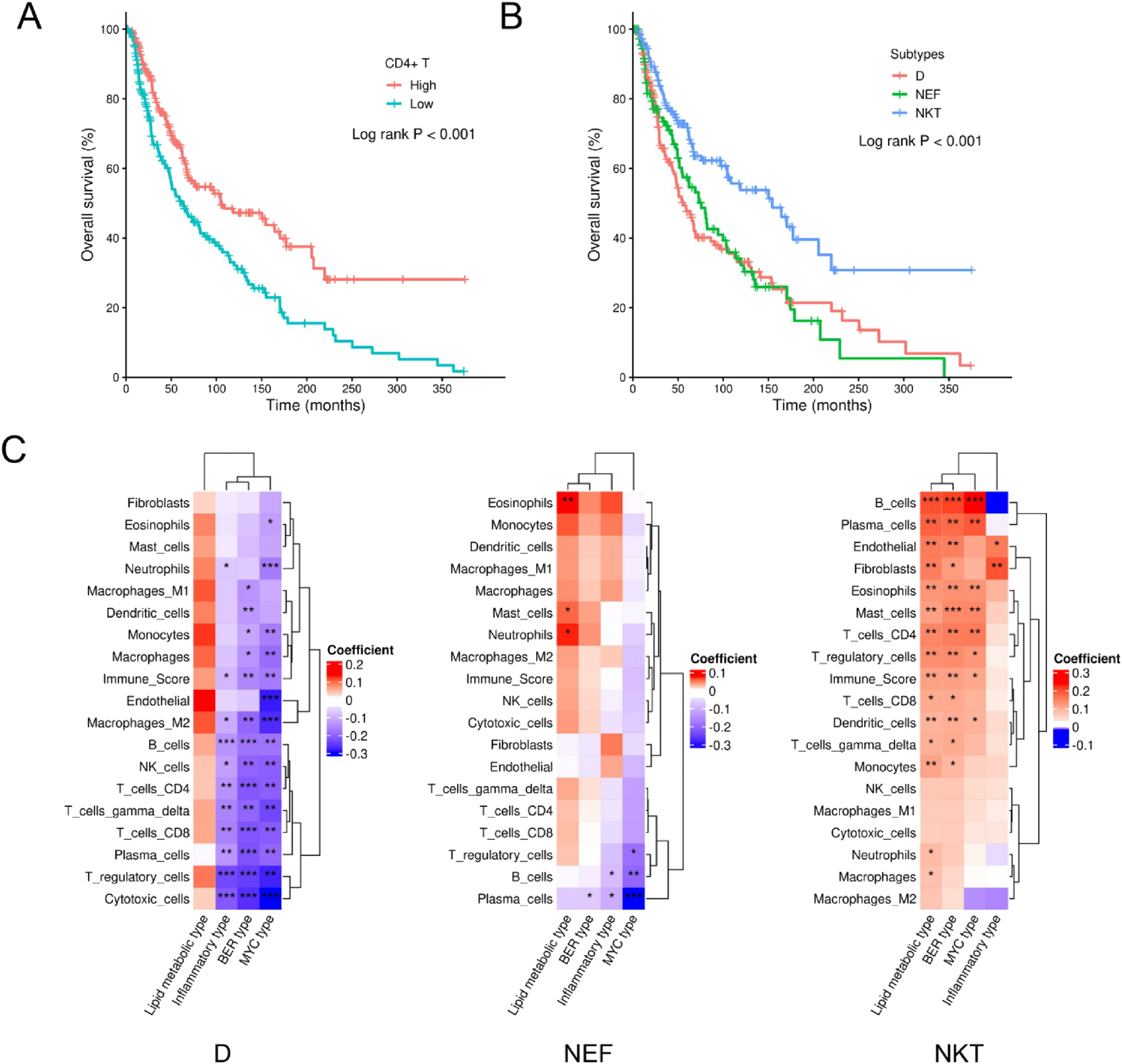

The heterogeneity of TME may have an impact on the association of CD4+T cells and the relative abundance of melanoma subtypes. To comprehensively elucidate this association, we classified patients into three subtypes based on their TME:D subtype featured with the lowest immune infiltration, NEF subtype with high infiltration of neutrophil cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts, and NKT subtype characterized with high infiltration of NK cells, T cells, and B cells. As expected, the results from GSVA demonstrated that NKT subtype exhibits high activity of type I and type II IFN response, immune checkpoint, NEF subtype displays elevated activity of angiogenesis, pan-fibroblast signature and D subtype is distinguished from these two subtypes by high tumor cell intrinsic features such as cell cycle and DNA damage repair (Supplementary Figure S3A). The reproducibility of three immune subtypes was maintained by two other independent melanoma cohorts profiled with microarray and bulk RNA-seq, respectively (Supplementary Figure S3B and C).

Consistent with the results from the MGSP cohort, Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that melanoma patients with high CD4+ T cell infiltration exhibited better overall survival (OS) compared to those with low infiltration (log-rank p<0.001) (Figure 3A). As to three immune subtypes, the NKT subtype was significantly associated with prolonged OS, as shown in Figure 3B (log-rank p<0.001, NKT vs. D adjusted p<0.001; NKT vs. NEF adjusted p=0.001). Subsequently, we investigated the associations between melanoma subtypes and 19 immune pathways. Univariate linear regression showed that the relative abundance of BER-subtype melanoma cells was significantly positively associated with CD4+ T cell infiltration only in the NKT subtype (Supplementary Figure S4). As shown in Figure 3C, the positive correlation of relative abundance of BER-subtype melanoma cells with CD4+ T cell infiltration remained significant within the NKT subtype in multivariate linear regression (p<0.001). However, in the NEF subtype, CD4+ T cell infiltration was not significantly related to BER-subtype melanoma, and a negative correlation was observed between CD4+ T cell infiltration and BER-subtype melanoma in the D subtype (Figure 3C).

CD4+ T cells and immune subtypes in melanoma patients from the TCGA SKCM cohort. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot showing different OS between patients with high or low CD4+ T cell infiltration. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot showing different OS among patients with D, NEF, or NKT subtype. (C) heatmap showing the regression coefficients and their significance from multivariate linear regression in each immune subtype. The asterisk ★, ★★, ★★★ labeled in the squares indicate significance level of 0.05–0.01, 0.001–0.01, and less than 0.001, respectively. The groups of high or low CD4+ T cell infiltration were determined by the median value of the enrichment score of CD4+ T cells from consensus TME.

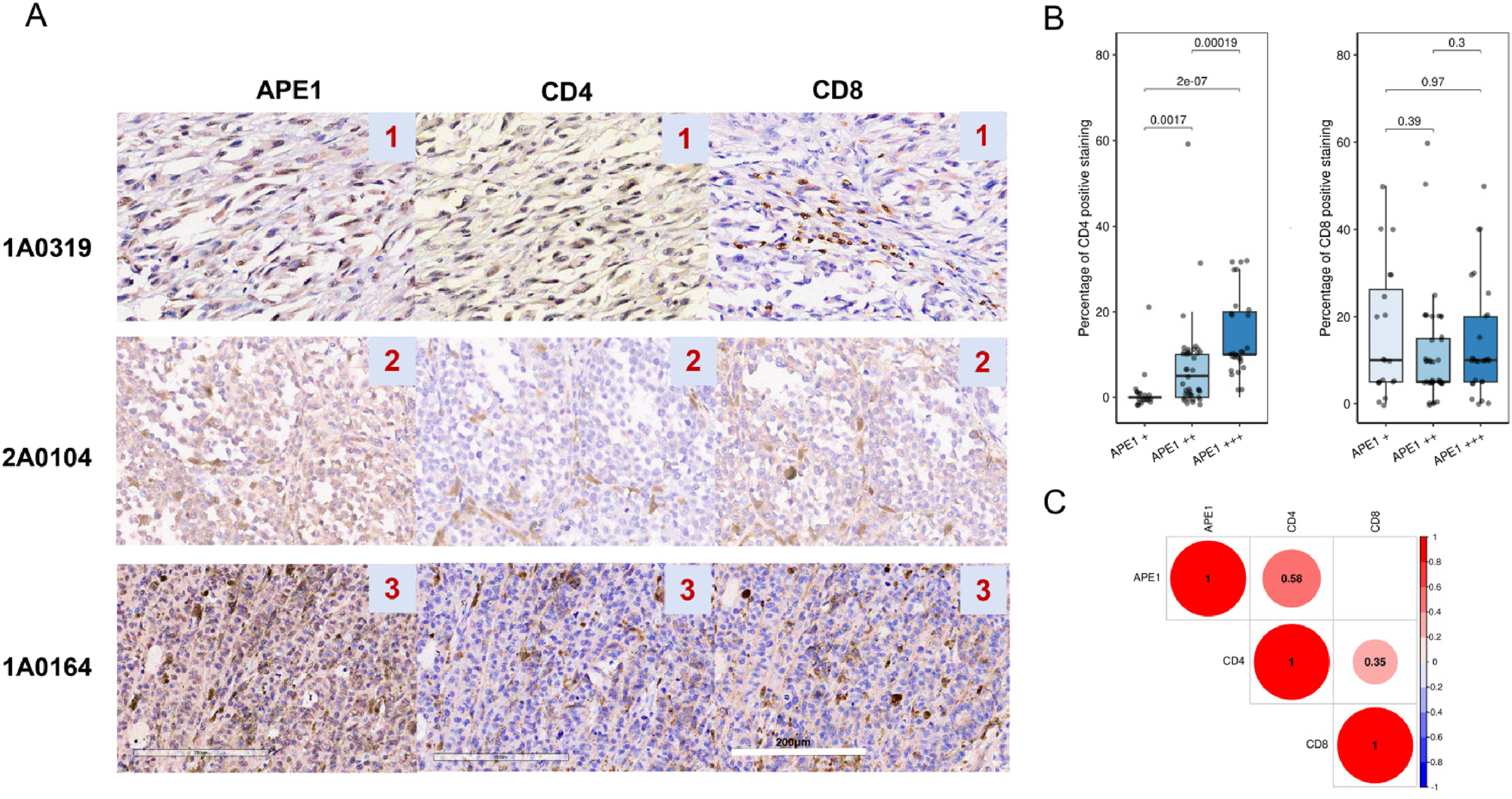

IHC assay identified the positive correlation between APE1 expression and CD4+ T cell infiltration

To further investigate the association between BER activity and tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cell abundance, a melanoma tissue microarray comprising 89 melanoma patients was used. The baseline clinicopathological characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Supplementary Table S6. IHC was employed to assess the expression levels of APE1, the rate-limiting enzyme in the BER pathway, and the density of CD4+/CD8+ TILs. Representative IHC images for APE1, CD4, and CD8 cells are shown in Figure 4A. The proportions of categorized CD4+ T as an ordinary variable were significantly different among the three APE1 categories revealed by the Kruskal-Wallis test (Supplementary Table S7). Considering the percentage of CD4 or CD8 positive staining as a continuous variable, the percentage of CD4 positive staining significantly increased with the elevation of APE1 staining density. The boxplots were shown in Figure 4B. As illustrated in Figure 4C, APE1 expression in melanoma cells demonstrated a significant positive correlation with categorized CD4+ T cell infiltration (Pearson’s r=0.58, p<0.001), consistent with the results of BER type melanoma observed in GSE222446 and TCGA SCKM NKT subtype. In contrast, no significant correlation was observed between APE1 expression and CD8+ T cell infiltration.

APE1 expression levels correlate with CD4+T cell infiltration. (A) representative IHC images of APE1 and TILs infiltration of CD4+, CD8+ cells. (B) boxplots showing the difference in the percentage of CD4+ T cells and CD8+T cells among three APE1 staining density groups. (C) correlation plots of CD4+ T or CD8+ T cells infiltration and APE1 expression. The number values in the colored circles represent the spearman correlation coefficients with significance less than 0.05.

Discussion

Melanoma is characterized by a high TMB and frequent mutations in DNA damage response (DDR) genes, leading to increased DNA damage and replication stress [34]. In this study, we found that the infiltration of CD4+ T cell is related to improved response to ICBs and clinical outcomes of melanoma patients. Then we found BER activity of melanoma cells is positively correlated to CD4+ T cell infiltration, and IHC assay validated the association between APE1 expression in melanoma cells and CD4+ T cell abundance.

Accumulating evidence suggests that DNA damage repair and immune responses jointly regulate the TME to maintain homeostasis [35]. Our findings revealed a positive association between BER-subtype melanoma and CD4+ T cell infiltration, while no significant association was observed between BER activity and CD8+ T cell infiltration. The role of BER in anti-tumor immunity activation is controversial. In line with our research, a previous study has identified the positive correlation between BER genes expression and CD4+ T cells in low-grade glioma [36]. However, Shpilman et al. Found that the elevated expression is associated with low tumor immunogenicity in head and neck cancer [37]. Specifically, they found that the expression of DNA N-glycosylase proteins (OGG1) and DNA polymerase β (POLB) is negatively related to CD8+ T cells abundance. Though DDR defects can lead to increased genome instability, it should be noted that the initiation of oxidative DNA damage is also related to the oxidative stress system. Our previous study found that the crosstalk between BER and oxidative stress is important to the survival and TME in lung adenocarcinoma, and patients with low BER activity and high oxidative stress activity are related to immune-active TME [38]. Hence, a comprehensive analysis of BER and other factors affecting the TME in different tumor types may be necessary.

In this study, we used APE1 as the validating protein in IHC assay. Notably, APE1 is a dual-function protein, and it not only participates in BER, it also functions as a redox regulator for multiple transcription factors and is closely linked to RNA metabolism [39]. Hence, the role of APE1 in tumor immunogenicity might be variable across different cancer types. Intriguingly, as we mentioned before, the results of this study contrast with our previous findings in NSCLC, where high APE1 expression is linked to low CD4+ T cell infiltration and poor outcomes. A lot of evidence has confirmed the biological heterogeneity across different tumor types [23], 40]. Especially, melanoma is a type of tumor with high immunogenicity, which may be the possible reason for this difference [41].

There are important limitations in our study. First, since prognostic data for the IHC cohort remain unavailable, the utility of BER pathway activity – particularly APE1 expression – as a predictive biomarker for targeted therapies requires further validation. Second, due to limitations in CD4+T cell resolution, we performed only a preliminary assessment of the relationship between BER activity and overall T cells (Tregs), which are a critical CD4+ subset in melanoma and may have immunosuppressive effects. Future work will delve deeper into the correlations between BER activity and specific CD4+T cell subpopulations.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that high CD4+ T cell infiltration is associated with improved immunotherapy response and prognosis in melanoma patients. The expression of APE1 in melanoma cells is positively correlated with CD4+ T cell infiltration. Combined evaluation of APE1 and CD4+ T cells may serve as a potential prognostic biomarker for immunotherapy.

Funding source: PhD Research Projects in Chongqing

Award Identifier / Grant number: CSTB2022BSXM-JCX0029

Acknowledgments

We thank the PhD Research Projects in Chongqing for funding support.

-

Research ethics: This study was conducted in accordance with the guideline of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Army Medical Center of PLA (2022 number 51).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was waived because this study was retrospective and did not involve patients’ personal information.

-

Author contributions: Lin’ang Wang and Lujie Yang conceived and designed the study; He Xiao made these bioinformatic analyses. Yuxin Yang and Xunjie Kuang conducted the experiments; Jinli Cheng provided data analysis. The manuscript was written by Jinli Cheng and revised by Lujie Yang. Lin’ ang Wang received funding support in this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: ChatGPT-4 is solely for the purpose of improving readability and language. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Research funding: This study is supported by PhD Research Projects in Chongqing (Granted Number: CSTB2022BSXM-JCX0029).

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Liu, Y, Zhang, H, Hu, D, Liu, S. New algorithms based on autophagy-related lncRNAs pairs to predict the prognosis of skin cutaneous melanoma patients. Arch Dermatol Res 2023;315:1511–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-022-02522-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Lazaroff, J, Bolotin, D. Targeted therapy and immunotherapy in melanoma. Dermatol Clin 2023;41:65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2022.07.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Di Raimondo, C, Lozzi, F, Di Domenico, PP, Campione, E, Bianchi, L. The diagnosis and management of cutaneous metastases from melanoma. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:14535. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241914535.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Fridman, WH, Galon, J, Pages, F, Tartour, E, Sautes-Fridman, C, Kroemer, G. Prognostic and predictive impact of intra- and peritumoral immune infiltrates. Cancer Res 2011;71:5601–5. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-11-1316.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Fridman, WH, Pages, F, Sautes-Fridman, C, Galon, J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:298–306. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3245.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Ziogas, DC, Theocharopoulos, C, Koutouratsas, T, Haanen, J, Gogas, H. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma: what we have to overcome? Cancer Treat Rev 2023;113:102499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102499.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Hamid, O, Robert, C, Daud, A, Hodi, FS, Hwu, WJ, Kefford, R, et al.. Five-year survival outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001. Ann Oncol 2019;30:582–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Veatch, JR, Lee, SM, Shasha, C, Singhi, N, Szeto, JL, Moshiri, AS, et al.. Neoantigen-specific CD4(+) T cells in human melanoma have diverse differentiation states and correlate with CD8(+) T cell, macrophage, and B cell function. Cancer Cell 2022;40:393–409 e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2022.03.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Draghi, A, Presti, M, Jensen, AWP, Chamberlain, CA, Albieri, B, Rasmussen, AK, et al.. Uncoupling CD4+ TIL-mediated tumor killing from JAK-signaling in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2023;29:3937–47. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-22-3853.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Liu, Q, Wang, L, Lin, H, Wang, Z, Wu, J, Guo, J, et al.. Tumor-specific CD4(+) T cells restrain established metastatic melanoma by developing into cytotoxic CD4(-) T cells. Front Immunol 2022;13:875718. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.875718.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022;12:31–46. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.cd-21-1059.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Jiang, M, Jia, K, Wang, L, Li, W, Chen, B, Liu, Y, et al.. Alterations of DNA damage response pathway: biomarker and therapeutic strategy for cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021;11:2983–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.01.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Li, T, Chen, ZJ. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. J Exp Med 2018;215:1287–99. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20180139.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Krokan, HE, Nilsen, H, Skorpen, F, Otterlei, M, Slupphaug, G. Base excision repair of DNA in mammalian cells. FEBS Lett 2000;476:73–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01674-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Hu, M, Zhang, Y, Zhang, P, Liu, K, Zhang, M, Li, L, et al.. Targeting APE1: advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of tumors. Protein Pept Lett 2025;32:18–33. https://doi.org/10.2174/0109298665338519241114103223.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. McIlwain, DW, Fishel, ML, Boos, A, Kelley, MR, Jerde, TJ. APE1/Ref-1 redox-specific inhibition decreases survivin protein levels and induces cell cycle arrest in prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget 2018;9:10962–77. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23493.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Caston, RA, Gampala, S, Armstrong, L, Messmann, RA, Fishel, ML, Kelley, MR. The multifunctional APE1 DNA repair-redox signaling protein as a drug target in human disease. Drug Discov Today 2021;26:218–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2020.10.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Oliveira, TT, Coutinho, LG, de Oliveira, LOA, Timoteo, ARS, Farias, GC, Agnez-Lima, LF. APE1/ref-1 role in inflammation and immune response. Front Immunol 2022;13:793096. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.793096.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Jedinak, A, Dudhgaonkar, S, Kelley, MR, Sliva, D. Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 regulates inflammatory response in macrophages. Anticancer Res 2011;31:379–85.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Akhter, N, Takeda, Y, Nara, H, Araki, A, Ishii, N, Asao, N, et al.. Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1/Redox Factor-1 (Ape1/Ref-1) modulates antigen presenting cell-mediated T helper cell type 1 responses. J Biol Chem 2016;291:23672–80. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m116.742353.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Wang, LA, Yang, B, Tang, T, Yang, Y, Zhang, D, Xiao, H, et al.. Correlation of APE1 with VEGFA and CD163(+) macrophage infiltration in bladder cancer and their prognostic significance. Oncol Lett 2020;20:2881–7. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2020.11814.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Qing, Y, Li, Q, Ren, T, Xia, W, Peng, Y, Liu, GL, et al.. Upregulation of PD-L1 and APE1 is associated with tumorigenesis and poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015;9:901–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.s75152.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Li, Y, Zhao, X, Xiao, H, Yang, B, Liu, J, Rao, W, et al.. APE1 may influence CD4+ naive T cells on recurrence free survival in early stage NSCLC. BMC Cancer 2021;21:233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07950-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Barras, D, Ghisoni, E, Chiffelle, J, Orcurto, A, Dagher, J, Fahr, N, et al.. Response to tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte adoptive therapy is associated with preexisting CD8(+) T-myeloid cell networks in melanoma. Sci Immunol. 2024;9:eadg7995. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.adg7995.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Hao, Y, Stuart, T, Kowalski, MH, Choudhary, S, Hoffman, P, Hartman, A, et al.. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat Biotechnol 2024;42:293–304. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-01767-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Tirosh, I, Izar, B, Prakadan, SM, Wadsworth, MH, 2nd, Treacy, D, Trombetta, JJ, et al.. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016;352:189–96. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad0501.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Aibar, S, Gonzalez-Blas, CB, Moerman, T, Huynh-Thu, VA, Imrichova, H, Hulselmans, G, et al.. SCENIC: single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering. Nat Methods 2017;14:1083–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4463.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Nader, K, Tasci, M, Ianevski, A, Erickson, A, Verschuren, EW, Aittokallio, T, et al.. ScType enables fast and accurate cell type identification from spatial transcriptomics data. Bioinformatics 2024;40:btae426. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btae426.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Zhang, Y, Sun, H, Zhang, W, Fu, T, Huang, S, Mou, M, et al.. CellSTAR: a comprehensive resource for single-cell transcriptomic annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2024;52:D859–D70. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad874.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Subramanian, A, Tamayo, P, Mootha, VK, Mukherjee, S, Ebert, BL, Gillette, MA, et al.. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:15545–50. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506580102.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Kong, Y, Rose, CM, Cass, AA, Williams, AG, Darwish, M, Lianoglou, S, et al.. Transposable element expression in tumors is associated with immune infiltration and increased antigenicity. Nat Commun 2019;10:5228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13035-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Revkov, E, Kulshrestha, T, Sung, KW, Skanderup, AJ. PUREE: accurate pan-cancer tumor purity estimation from gene expression data. Commun Biol 2023;6:394. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-04764-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Liu, D, Schilling, B, Liu, D, Sucker, A, Livingstone, E, Jerby-Arnon, L, et al.. Integrative molecular and clinical modeling of clinical outcomes to PD1 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med 2019;25:1916–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0654-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Maresca, L, Stecca, B, Carrassa, L. Novel therapeutic approaches with DNA damage response inhibitors for melanoma treatment. Cells 2022;11:1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11091466.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Pateras, IS, Havaki, S, Nikitopoulou, X, Vougas, K, Townsend, PA, Panayiotidis, MI, et al.. The DNA damage response and immune signaling alliance: is it good or bad? Nature decides when and where. Pharmacol Ther 2015;154:36–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.06.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. P, P, Kumari, S, Kumar, S, Muthuswamy, S. Comprehensive exploration on the role of base excision repair genes in modulating immune infiltration in low-grade glioma. Pathol Res Pract 2024;262:155559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2024.155559.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Shpilman, Z, Kidane, D. Dysregulation of base excision repair factors associated with low tumor immunogenicity in head and neck cancer: implication for immunotherapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2024;16:17588359241248330. https://doi.org/10.1177/17588359241248330.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Rao, W, Zhang, Q, Dai, X, Yang, Y, Lei, Z, Kuang, X, et al.. A three-subtype prognostic classification based on base excision repair and oxidative stress genes in lung adenocarcinoma and its relationship with tumor microenvironment. Sci Rep 2025;15:16647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98088-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Malfatti, MC, Bellina, A, Antoniali, G, Tell, G. Revisiting two decades of research focused on targeting APE1 for cancer therapy: the pros and cons. Cells 2023;12:1895. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12141895.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Bagaev, A, Kotlov, N, Nomie, K, Svekolkin, V, Gafurov, A, Isaeva, O, et al.. Conserved pan-cancer microenvironment subtypes predict response to immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2021;39:845–65 e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2021.04.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Kalaora, S, Nagler, A, Wargo, JA, Samuels, Y. Mechanisms of immune activation and regulation: lessons from melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer 2022;22:195–207. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-022-00442-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/oncologie-2025-0244).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Tech Science Press (TSP)

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Liquid biopsy – a promising and effective method for surveying non-small cell lung cancer minimal residual diseases and anti-cancer drug response after treatment

- Current application status of proton beam therapy for gastrointestinal tumors

- Research progress on the regulation of cuproptosis-related genes by non-coding RNAs in tumors

- Deep learning in hepatic oncology imaging: a narrative review of computed tomography applications

- Synergistic approaches: a narrative mini-review of radiotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of lung cancer

- Research Articles

- Intravesical prostatic protrusion as a predictor of acute urinary retention following stereotactic body radiation therapy for localised prostate cancer: a retrospective study

- The differential effect of glutamine supplementation on the orthotopic and subcutaneous growth of two syngeneic murine models of glioma

- Intermittent afatinib treatment suppresses the growth of resistant T790M-H1975 cells in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) co-culture

- Prognostic stratification of colorectal cancer by immune profiling reveals SPP1 as a key indicator for tumor immune status

- The activity of base excision repair is positively correlated with the infiltration of CD4+ T cells in melanoma

- Integrated analysis of immunity and ferroptosis related tumor microenvironment in a novel risk score model for lung adenocarcinoma prognosis

- Retrospective analysis of risk factors for early recurrence after hepatocellular carcinoma resection

- The ENST00000539930 transcript predicts sensitivity to PARP inhibitors and clinical prognosis in cancers

- VTA1 and breast cancer: a potential indicator for diagnostic and prognostic evaluation

- USP24 stabilizes VDAC2 via deubiquitination to promote apoptosis and ferroptosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC)

- Clinicopathological characteristics, prognosis, and therapeutic implications in breast cancer with pathologically confirmed bone marrow metastases: an observational retrospective study

- Short Commentaries

- Cancer cell mitochondria: the missing puzzle in predicting response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors

- From mitochondrial cristae pathobiology to metabolic reprogramming in cancer: the α and ω of Malignancies?

- Article Commentary

- Stopping SOAT1 sparks an immune attack on liver cancer: a metabolic-immune axis in hepatocellular carcinoma

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Liquid biopsy – a promising and effective method for surveying non-small cell lung cancer minimal residual diseases and anti-cancer drug response after treatment

- Current application status of proton beam therapy for gastrointestinal tumors

- Research progress on the regulation of cuproptosis-related genes by non-coding RNAs in tumors

- Deep learning in hepatic oncology imaging: a narrative review of computed tomography applications

- Synergistic approaches: a narrative mini-review of radiotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of lung cancer

- Research Articles

- Intravesical prostatic protrusion as a predictor of acute urinary retention following stereotactic body radiation therapy for localised prostate cancer: a retrospective study

- The differential effect of glutamine supplementation on the orthotopic and subcutaneous growth of two syngeneic murine models of glioma

- Intermittent afatinib treatment suppresses the growth of resistant T790M-H1975 cells in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) co-culture

- Prognostic stratification of colorectal cancer by immune profiling reveals SPP1 as a key indicator for tumor immune status

- The activity of base excision repair is positively correlated with the infiltration of CD4+ T cells in melanoma

- Integrated analysis of immunity and ferroptosis related tumor microenvironment in a novel risk score model for lung adenocarcinoma prognosis

- Retrospective analysis of risk factors for early recurrence after hepatocellular carcinoma resection

- The ENST00000539930 transcript predicts sensitivity to PARP inhibitors and clinical prognosis in cancers

- VTA1 and breast cancer: a potential indicator for diagnostic and prognostic evaluation

- USP24 stabilizes VDAC2 via deubiquitination to promote apoptosis and ferroptosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC)

- Clinicopathological characteristics, prognosis, and therapeutic implications in breast cancer with pathologically confirmed bone marrow metastases: an observational retrospective study

- Short Commentaries

- Cancer cell mitochondria: the missing puzzle in predicting response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors

- From mitochondrial cristae pathobiology to metabolic reprogramming in cancer: the α and ω of Malignancies?

- Article Commentary

- Stopping SOAT1 sparks an immune attack on liver cancer: a metabolic-immune axis in hepatocellular carcinoma